Abstract

Although acute management of pelvic fractures and their long-term functional outcome have been widely documented, important information regarding malunion and nonunion of these fractures is sparse. Despite their relative rarity, malunions and nonunions cause disabling symptoms and have major socioeconomic implications. We analyzed the factors predisposing a pelvic injury to develop malunion/nonunion, the clinical presentation of these complications, and the efficacy of the reported operative protocols in 437 malunions/nonunions of 25 clinical studies. Treatment of these demanding complications appeared effective in the majority of the cases: overall union rates averaged 86.1%, pain relief as much as 93%, patient satisfaction 79%, and return to a preinjury level of activities 50%. Nevertheless, the patient should be informed about the incidence of perioperative complications, including neurologic injury (5.3%), symptomatic vein thrombosis (5.0%), pulmonary embolism (1.9%), and deep wound infection (1.6%). For a successful outcome, a thorough preoperative plan and methodical operative intervention are essential. In establishing effective evidence-based future clinical practice, the introduction of multicenter networks of pelvic trauma management appears a necessity.

Level of Evidence: Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Acute pelvic fractures are usually the result of high-energy trauma. They are lethal in 3% to 30% of cases and are associated with a high incidence of concomitant morbidity [3, 13, 15, 21, 27, 48, 52]. During the past decade, with enhanced understanding of the physiologic response to trauma and advances made in diagnostics, critical care medicine, and acute trauma management [5, 23, 26, 57], an increased number (81%–90%) of injured patients with severe pelvic injuries survive [26, 29, 58]. The potential associated chronic complications in this special group of injuries should not be neglected because they could lead to serious consequences, including chronic debilitating pain, gait impairment, impotence, and incontinence [34, 44, 49, 64, 65].

Stable pelvic injuries rarely result in major long-term problems [8, 21] because their initial treatment is mostly straightforward and their recovery uneventful and complete [49, 53]. In contrast, patients with unstable pelvic ring disruptions are considerably more challenging to treat, and limited ambulation and incomplete recovery reportedly range from 25% to 73% [35, 44, 49, 53, 64, 65, 70].

Functional outcome after these unstable pelvic fractures is affected by the presence of the other associated musculoskeletal, visceral, and nerve injuries that usually accompany severe pelvic trauma [28, 38, 55, 66]. Furthermore, the outcome also is affected by development of malunion or nonunion of the pelvic ring resulting from initial suboptimal reduction, insufficient fixation methods, and other local and systemic factors, resulting in chronic residual pain, deformity, and progressive functional disability [34, 36, 49].

Treatment and salvage alternatives for malunited or nonunited pelvic fractures usually are the domain of tertiary referral centers owing to the complexity of these cases and the surgical expertise needed for a successful result [14, 20]. Whereas initial treatment of pelvic fractures and their long-term outcomes have been well reported [14, 49, 56], the literature regarding treatment of pelvic malunions and nonunions is sparse. With the increased incidence of major vehicular injuries and resulting severe pelvic trauma [2, 45] and the unremitting contemporary demand for restoration of function [49], aspects of management and overall outcome of pelvic fracture malunions/nonunions are of considerable interest, not only for pelvic specialists, but also for the wider orthopaedic and rehabilitation scientific community.

We therefore performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the existing evidence regarding the (1) characteristics of the original pelvic injury and its initial management that predispose to the development of these complications, (2) clinical manifestation of pelvic malunions/nonunions, (3) treatment alternatives of pelvic malunions/nonunions, and (4) last outcome of these late complications of pelvic fractures.

Materials and Methods

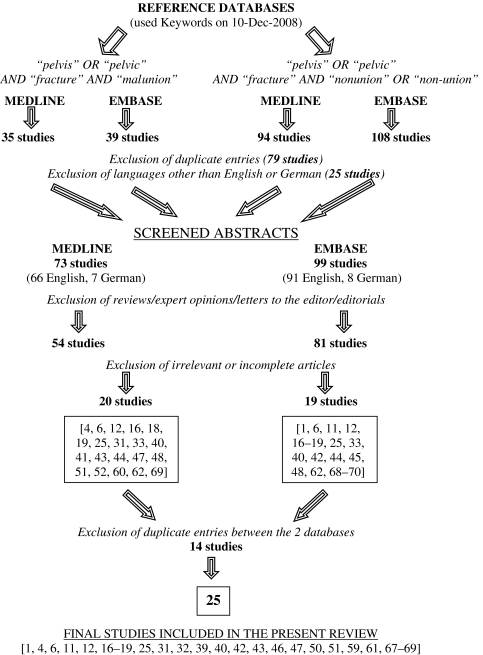

We performed a systematic review of the literature to identify all publications dealing with management of pelvic malunion and nonunion. An electronic search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases (from January 1965 to November 2008) was conducted, entering the following terms and Boolean operators: “pelvis” OR “pelvic”, AND “fracture”, AND “malunion”, OR “nonunion”, OR “non-union”. Only papers in English or German were included. Articles were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the target population consisted of patients with malunion and/or nonunion of pelvic fractures; (2) each study described the treatment method of these complications; and (3) the outcome of the treated malunion and/or nonunion was described adequately. Case reports were included so that all the related published series would be presented in this review. Review papers, expert opinion articles, editorials, letters to the editor, publications on congress proceedings, manuscripts with incomplete documentation of the deformity, details of the applied treatment, or final results and outcome, or unpublished series were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A flowchart illustrates our study selection process.

The quality of the reviewed manuscripts was evaluated by two assessors (NKK, VSN). They independently classified the reviewed studies for the level of evidence [7, 60] (Table 1). The interrater agreement regarding the quality and level of evidence of the reviewed studies between the two assessors was high (kappa, 0.829) [9].

Table 1.

Demographics of patients in the 25 reviewed series

| Study | Year | Level of evidence [7] | Number of patients | Gender (males/females) | Age (years)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schofer et al. [61] | 2008 | IV | 2 | 0/2 | 61 (57–65) |

| Oransky and Tortora [47] | 2007 | IV | 55 | 25/30 | 39 (14–70) |

| Oakley et al. [46] | 2007 | IV | 1 | 0/1 | 70 |

| Matta and Yerasimides [40] | 2007 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 55 |

| Giannoudis et al. [25] | 2007 | IV | 9 | 1/8 | 39 (27–62) |

| Delloye et al. [12] | 2007 | IV | 3 | N/A | 34 (8–76) |

| Rousseau et al. [59] | 2006 | IV | 8 | 4/4 | NA (18–43) |

| Beaule et al. [6] | 2006 | IV | 2 | 2/0 | 49 (NA) |

| Egol and Kellam [17] | 2003 | IV | 1 | 0/1 | 42 |

| Mears and Velyvis [42] | 2003 | IV | 204 | 114/90 | 52 (24–88) |

| Huegli et al. [32] | 2003 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 55 |

| Mears and Velyvis [43] | 2002 | IV | 44 | 11/33 | 66 (55–87) |

| Akagi et al. [1] | 2002 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 24 |

| van den Bosch et al. [67] | 2002 | IV | 11† | 5/6 | 40.7 (23–56) |

| Frigon and Dickson [19] | 2001 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 52 |

| Altman et al. [4] | 2000 | IV | 2 | 0/2 | 50.5 (48–53) |

| Westphal et al. [69] | 1999 | IV | 1 | 0/1 | 53 |

| Vanderschot et al. [68] | 1998 | IV | 2 | 2/0 | 34 (33–35) |

| Ebraheim et al. [16] | 1998 | IV | 4 | 1/3 | 43.5 (25–63) |

| Matta et al. [39] | 1996 | IV | 37 | 18/19 | 34 (6–71) |

| De Boeck et al. [11] | 1995 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 51 |

| Pavlov et al. [50] | 1982 | IV | 2 | 0/2 | 30 (25–35) |

| Hallel and Malkin [31] | 1982 | IV | 1 | 0/1 | 73 |

| Pennal and Massiah [51] | 1980 | IV | 42 | 39/3 | 35 (19–60) |

| Elton [18] | 1972 | IV | 1 | 1/0 | 36 |

| Totals/averages | IV | 437 | 228/206 | 47.2 (6–88) |

* Values expressed as means, with ranges in parentheses; †11 reported nonunion cases but two with full documentation; NA = not available.

Data extracted from these articles were further analyzed for: (1) the initial type of injury and method of original management to identify predisposing factors for development of these complications; (2) the clinical manifestation of these complications of pelvic trauma; (3) the therapeutic approach that was used; and (4) the final outcome (early and late postoperative complications and final functional results).

Of 172 papers initially selected based on the search strategy of this study, 25 met the inclusion criteria [1, 4, 6, 11, 12, 16–19, 25, 31, 32, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 51, 59, 61, 67–69]. The level of evidence of these studies was IV (retrospective/prospective uncontrolled case series [12, 16, 25, 39, 42, 43, 47, 51, 59, 67] or case reports [1, 4, 6, 11, 17–19, 31, 32, 40, 46, 50, 61, 68, 69]). Four hundred thirty-seven patients were included for the final analysis (Table 1). Solely malunions were recorded in 113 patients [19, 39, 40, 42, 46, 47, 59, 68] and solely nonunions in 198 patients [1, 4, 6, 11, 12, 16–19, 25, 31, 32, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 51, 61, 67–69]. Mears and Velyvis [42] introduced the rationale of classifying late complications of pelvic trauma separately. According to their concept, we classified complications of all reviewed patients as Type I, clear nonunions; Type II, united malalignments or clear malunions; Type III, ununited malalignments; and Type IV, partially united malalignments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Injury, treatment, and complication according to Mears and Velyvis [42] classification

| Study | Mechanism of initial pelvic injury (number of patients) | Type of initial pelvic injury (number of patients) | Treatment of initial pelvic injury (number of patients) | Type of late complication (number of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schofer et al. [61] | Fall (2) | NA | Nonoperative (2) | Type I (2) |

| Oransky and Tortora [47] | MVA (44) | LC (7) | Nonoperative (38) | Type I (11) |

| Fall (7) | APC (11) | Ex-Fix (15) | Type II (44) | |

| Work-related (5) | VS (32) | ORIF (2) | ||

| CMI (5) | ||||

| Oakley et al. [46] | Postgrafting (1) | APC (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type III (1) |

| Matta and Yerasimides [40] | MVA (1) | APC (1) | ORIF (1) | Type III (1) |

| Giannoudis et al. [25] | MVA (3) | LC (3) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (9) |

| Fall (1) | APC (1) | Ex-Fix (2) | ||

| Pathologic fracture (1) | Osteitis pubis (4) | ORIF (6) | ||

| Others (4) | Septic sacroileitis (1) | |||

| Delloye et al. [12] | Others (3) | N/A | ORIF (3) | Type I (3) |

| Rousseau et al. [59] | NA | Tile Type B (2) | Nonoperative (4) | Type II (8) |

| Tile Type C (6) | Ex-Fix (3) | |||

| ORIF (1) | ||||

| Beaule et al. [6] | NA | NA | ORIF (2) | Type I (2) |

| Egol and Kellam [17] | Insufficiency fracture (1) | NA | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| Mears and Velyvis [42] | MVA (117) | Tile Type A (4) | Nonoperative or Ex-Fix (166) | Type I (70) |

| Fall (53) | Tile Type B (7) | Type II (43) | ||

| Work-related (34) | Tile Type C (186) | ORIF (35) | Type III (64) | |

| Type IV (27) | ||||

| Huegli et al. [32] | Fall (1) | Tile Type C or LC (1) | ORIF (1) | Type IV (1) |

| Mears and Velyvis [43] | Pathologic fracture (27) | Pathologic/insufficiency fractures (44) | Nonoperative (44) | Type I (44) |

| Stress fracture (17) | ||||

| Akagi et al. [1] | MVA (1) | APC (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| van den Bosch et al. [67] | MVA (5) | Tile Type B (6) | Nonoperative (6) | Type I (11) |

| Fall (2) | Tile Type C (5) | Ex-Fix (1) | ||

| Others (4) | ORIF (4) | |||

| Frigon and Dickson [19] | MVA (1) | LC (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type III (1) |

| Altman et al. [4] | MVA (1) | Tile Type A (2) | Nonoperative (2) | Type I (1) |

| Pathologic fracture (1) | ||||

| Westphal et al. [69] | MVA (1) | CMI (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| Vanderschot et al. [68] | MVA (2) | Tile Type C (1) | Ex-Fix (2) | Type III (2) |

| Ebraheim et al. [16] | MVA (3) | Tile Type A (2) | Nonoperative (3) | Type I (4) |

| Postgrafting (1) | Tile Type B (2) | ORIF (1) | ||

| Matta et al. [39] | MVA (28) | NA | Nonoperative (23) | Type II (18) |

| Fall (2) | Ex-Fix (3) | Type III (19) | ||

| Postgrafting (1) | ORIF (7) | |||

| Others (6) | Ex-Fix + ORIF (2) | |||

| De Boeck et al. [11] | MVA (1) | LC (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| Pavlov et al. [50] | Stress fracture (2) | NA | Nonoperative (2) | Type I (2) |

| Hallel and Malkin [31] | Pathologic fracture (1) | Distraction of pubic symphysis (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| Pennal and Massiah [51] | MVA (11) | LC (15) | Nonoperative (42) | Type I (32) |

| Fall (9) | APC (7) | |||

| Work-related (22) | VS (17) | |||

| Miscellaneous (3) | ||||

| Elton [18] | MVA (1) | APC (1) | Nonoperative (1) | Type I (1) |

| Delayed unions (10) |

MVA = motor vehicle accident; NA = not available; LC = lateral compression; APC = anteroposterior compression; VS = vertical shear; CMI = combined mechanism of injury; Ex-Fix = external fixation; ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation; Type I = nonunion; Type II = united malalignment; Type III = ununited malalignment; Type IV = partially united malalignment.

Results

Predisposing Factors for Development of Malunion/Nonunion

The most common mechanism of injury was motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) with an incidence of 51.3% (219 of 427 patients) (Table 2). From the eight studies [1, 4, 11, 16, 42, 59, 67, 68] (245 patients) that used the Tile and Pennal classification system [63], 88.1% (200) of the patients had initially Type C pelvic fractures. In the 13 studies [1, 11, 17–19, 25, 31, 32, 40, 46, 47, 51, 69] (111 patients) in which the Young and Burgess system [10] was used, vertical shear was the most common mechanism of injury (44.1%, 49 patients).

Nonoperative treatment (bed rest, traction, or pelvic sling) was by far the most common initial treatment modality that led to malalignment, delayed union, or established nonunion [1, 4, 11, 16–19, 25, 31, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 51, 59, 67, 69]. In the large series of Mears and Velyvis [42], nonoperative treatment and external fixation were described together in 166 patients. External fixation was used and led to malunion/nonunions in another 24 patients described in four other studies [39, 47, 59, 67, 68]. Overall, 341 of 437 (78.9%) malunion/nonunions of the pelvic girdle were treated initially either nonoperatively or just by external fixation systems.

Clinical Manifestations of Pelvic Malunion/Nonunions

Pain was by far the major recorded symptom in all the reviewed studies with an incidence of 97%. It was recorded as anterior, posterior, or simultaneously at both areas, nonradicular, activity-related, or disabling at various levels (from restricting pain at the extremes of the range of motion of the hips [4], sitting discomfort [39, 42, 47, 51, 69], dyspareunia, and sexual problems of mechanical origin [1, 19, 25, 42, 59] to bed confinement for patients with continuous debilitating pain [18, 25, 42, 43, 47, 51]). Nonunions of the anterior elements could be pain-free [4, 31, 50] in contrast to those of the posterior elements in which they were mostly symptomatic [39, 42, 51]. Pain was attributed to the nonunion site, the produced pelvic instability, the deformity, and the altered mechanics in patients with malunion, or to a combination of all of these. Pain related to neurologic trauma at the initial accident was differentiated as a symptom and was not expected to recover after revision surgery for pelvic nonunion/malunion [39, 42, 47].

Gait disturbance (antalgic gait, Trendelenburg) and use of walking aids affected 67.4% of the patients [1, 4, 11, 16–18, 25, 40, 42, 43, 47, 51, 59, 61, 67–69]. Clinically important leg length discrepancy was identified in 24.8% of patients [17, 40, 42, 47, 59, 68]. However, clinically important leg length discrepancy was defined differently in the different studies (eg, length difference > 1 cm [47] and > 2 cm [59]), which compromises the compatibility of the reported percentages.

Clinically or radiographically evident pelvic instability (by stress views) was described in 60.3% of patients with nonunions [25, 42, 43, 47, 51]. Pelvic deformity was identified in 31.7% [39, 42, 47, 51]. Deformity was described as an aesthetic problem or as causing imbalance of the ischial tuberosities, especially during sitting. Vertical displacement (in 16%) or sagittal malrotation (in 18%) of the affected hemipelves was differentiated in the series of Mears and Velyvis [42] as different forms of pelvic asymmetry, both major causes of pain and discomfort with sitting.

Treatment Alternatives of Established Pelvic Malunion/Nonunions

The time that elapsed between the initial injury and surgical treatment of the deformity/instability was, on average, 26 months (range, 10 weeks to 15 years) for the 396 patients of the 21 studies with full data [1, 4, 6, 11, 16–19, 25, 31, 32, 39, 40, 42, 47, 50, 51, 59, 61, 67, 69] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Final corrective treatment

| Study | Final treatment | Number of patients | Three-staged operations | Two-staged operations | One-staged operations | Duration (hours)* | Blood loss (mL)* | Postoperative followup* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schofer et al. [61] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 12 weeks | ||

| Oransky and Tortora [47] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 55 | 30 | 10 | 15 | 6 (2–10) | 700 (200–5000) | 5.85 years (16 months–14 years) |

| Oakley et al. [46] | ORIF + grafting (allograft) | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 2 years | ||

| Matta and Yerasimides [40] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 10 weeks | ||

| Giannoudis et al. [25] | ORIF + grafting (ABG + BMP7) | 4 | 1 | 8 | NA | NA | 16 months (12–27 months) | |

| ORIF + grafting (BMP7) | 6 | |||||||

| Delloye et al. [12] | ORIF + grafting (allograft) | 3 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Rousseau et al. [59] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 8 | 8 | 4.6 (NA) | 1050 (NA) | 10 months (4–26 months) | ||

| Beaule et al. [6] | ORIF | 2 | 2 | 2, 8 | 300, 2500 | 39 months | ||

| Mears and Velyvis [42] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 161 | 186 | 18 | NA | NA | 8.7 years (2–20 years) | |

| ORIF | 43 | |||||||

| Huegli et al. [32] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 3 months | ||

| Mears and Velyvis [43] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 8 | 44 | NA | NA | 4 years (2–11 years) | ||

| ORIF + grafting (allograft) | 10 | |||||||

| ORIF | 26 | |||||||

| Frigon and Dickson [19] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 14 months | ||

| Altman et al. [4] | ORIF | 2 | 2 | 1.1, 1.4 | 12, 25 | 20, 40 months | ||

| Vanderschot et al. [68] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 2 | 2 | 7, 8 | 1600, 2000 | 14 months | ||

| Ebraheim et al. [16] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 1 | 1 | 3 | NA | NA | 13 months | |

| ORIF | 3 | |||||||

| Matta et al. [39] | ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 19 | 26 | 9 | 2 | 7 (1.5–10.5) | 1977 (200–7200) | 3 years 11 months (9 months–11 years) |

| ORIF | 18 | |||||||

| Pavlov et al. [50] | Nonoperative | 2 | NA | NA | 5, 35 months | |||

| Hallel and Malkin [31] | Nonoperative | 1 | NA | NA | 24 months | |||

| Pennal and Massiah [51] | Nonoperative | 24 | 18 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Grafting (ABG) | 2 | |||||||

| ORIF + grafting (ABG) | 2 | |||||||

| Ex-Fix + grafting (ABG) | 14 | |||||||

| Elton [18] | Débridement | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

* Values expressed as means, with ranges in parentheses; ORIF = open reduction and internal fixation; ABG = autologous bone grafting; Ex-Fix = external fixation; NA = not available.

All but 27 (6.3%) of the reviewed patients underwent surgery for an established deformity/instability [31, 50, 51]. Nonoperative treatment of pelvic nonunions included spica casts, bed rest, and restricted mobilization, but these were reported only in literature from more than 25 years ago [31, 50, 51].

The combination of open reduction-internal fixation and bone grafting was the preferred method for treatment of pelvic malunion/nonunion for the majority of the cases (288 patients, 67.3%). In two patients with nonunion (0.5%), solely bone grafting was used [51], whereas in 96 patients with malunion (22.4%), bone grafting did not supplement the fixation [4, 6, 17, 39, 43]. External fixation together with bone grafting was the preferred treatment in 14 patients (33.3%) in the early series of Pennal and Massiah [51].

In the majority of patients, the graft was autologous cancellous bone harvested from the pelvis (283 patients, 87.6%). In 19 (5.2%), allografts [12, 25, 43, 46] or different bone substitutes (either demineralized bone matrix [46] or bone morphogenetic protein-7 [25]) were used.

A multistage procedure consisting of two or three stages (same anesthesia) was used in the majority of the patients (275 patients in nine studies [16, 25, 39, 40, 42, 46, 47, 59, 68]). This approach was described initially in 1996 [39] as an initial anterior approach with the patient supine, then turned prone for a posterior approach, and finally supine for a repeat anterior approach and final stabilization of the pelvic girdle, or alternatively first prone, then supine, and finally prone. After each stage, the wound was closed and the first wound was reopened for the third stage. The first stage was to mobilize either anterior or posterior injuries by osteotomy of malunions or mobilizing nonunions. The patient then was repositioned for completion of the pelvic ring osteotomy and mobilization of the elements to achieve the most possible anatomic reduction; and at the third stage, the reduction and fixation were completed. The three-stage reconstruction allows the maximum degree of deformity reduction, nonunion débridement, and stable fixation.

Standard surgical approaches of the pelvis (anterior-posterior approaches to sacroiliac joint, ilioinguinal, Pfannestiel) were used in all cases, depending on the individual site of the established nonunion or malunion that needed surgical intervention.

Perioperative monitoring with somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) was used after 1986 in the large series of Mears and Velyvis [42] and in the case reports of Vanderschot et al. [68] and Frigon and Dickson [19].

Operative time was recorded in six studies [4, 6, 39, 47, 59, 68] referring to 106 patients and was, on average, 6.14 hours (range, 1.1–10.4 hours). The total amount of intraoperative blood loss ranged between 12 and 7200 mL (average, 1193 mL). The average followup in all series was 80.9 months (range, 3 months–20 years; median, 104 months).

Fifteen of the 25 reviewed studies described the postoperative mobilization scheme [1, 4, 6, 12, 18, 25, 32, 39, 40, 43, 59, 61, 68, 69]. All authors, except Huegli et al. [32], recommended an initial period of restricted weightbearing. This ranged from complete immobilization in a cast in the early series [18] to nonweightbearing for 6 weeks [59, 69], 2 months [12, 25], or 3 months [1, 6, 68] or bed-to-chair mobilization and toe-touch weightbearing for either 6 weeks [4, 40, 43] or 3 to 5 months [61].

Outcome

Complications related to operative treatment in the reviewed series were recorded in 57 patients of a total of 378 pelvic malunions/nonunions [1, 4, 6, 11, 12, 17, 19, 25, 32, 39, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 59, 61, 67–69] (Table 4). The most often cited complication was a neurologic deficit (20 cases, 35.1% of all complications, with an incidence of 5.3%). The neurologic deficits varied between permanent or temporary palsy of the sciatic nerve, injury to the lumbosacral plexus, and injury to the superior gluteal nerve, and some were missed intraoperatively despite SSEP being performed in at least one case [39]. Deep vein thrombosis was documented in 5%, pulmonary embolism in 1.9%, deep infection in 1.6%, intraoperative bladder injuries in 0.8%, and vascular injuries in 0.5%.

Table 4.

Postoperative complications, reoperation rates, and outcomes

| Study | Early complications (incidence*) | Late complications (incidence*) | Number of reoperations | Final outcome (incidence*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schofer et al. [61] | Nerve injuries (6/55, 10.9%) | Persistent nonunions (1/55, 1.8%) | 2/55, 0% | Union (49/55, 89.1%) |

| Bladder injuries (2/55, 3.6%) | Implant failure (6/55, 10.9%) | Satisfied patients (54/55, 98.2%) | ||

| Oransky and Tortora [47] | 0% | 0% | 0/2, 0% | Union (2/2, 100%) |

| Satisfied patients (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Oakley et al. [46] | Deep infections (1/1, 100%) | Persistent nonunions (1/1, 100%) | 1/1, 100% | Union (0/1, 0%) |

| Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Matta and Yerasimides [40] | 0% | 0% | 0/1, 0% | Union (1/1, 100%) |

| Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Giannoudis et al. [25] | 0% | Persistent nonunions (1/9, 11.1%) | 0/9, 0% | Union (8/9, 88.9%) |

| Persistent pain (3/9, 33.3%) | Preinjury level (5/9, 55.5%) | |||

| Satisfied patients (8/9, 88.9%) | ||||

| Delloye et al. [12] | 0% | Persistent nonunions (2/3, 66.7%) | 2/3, 66.7% | Satisfied patients (1/3, 33.3%) |

| Rousseau et al. [59] | Nerve injuries (3/8, 37.5%) | Persistent nonunions (1/8, 12.5%) | 0/8, 0% | Preinjury level (5/8, 62.5%) |

| Deep infections (1/8, 12.5%) | Persistent pain (2/8, 25%) | Satisfied patients (5/8, 62.5%) | ||

| Bladder injury (1/8, 12.5%) | Implant failure (1/8, 12.5%) | |||

| Beaule et al. [6] | 0% | 0% | NA | Union (2/2, 100%) |

| Satisfied patients (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Mears and Velyvis [42] | Nerve injuries (8/204, 3.9%) | Persistent nonunions (9/204, 4.4%) | 9/204, 4.4% | Union (195/204, 100%) |

| Deep infections (3/204, 1.5%) | Persistent pain (2/204, 1%) | Preinjury level (1/1, 100%) | ||

| PE (7/204, 3.4%) | Satisfied patients (165/204, 100%) | |||

| DVT (14/204, 6.9%) | ||||

| Huegli et al. [32] | 0% | 0% | 0/1, 0% | Union (1/1, 100%) |

| Preinjury level (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Mears and Velyvis [43] | Vascular injury (1/44, 2.3%) | Persistent nonunions (8/44, 18.2%) | 7/44, 15.9% | Union (36/44, 81.8%) |

| DVT (5/44, 11.4%) | Persistent pain (13/44, 29.5%) | Preinjury level (24/44, 54.5%) | ||

| Implant failure (1/44, 2.3%) | Satisfied patients (34/44, 77.3%) | |||

| Frigon and Dickson [19] | 0% | 0% | 0/1, 0% | Union (1/1, 100%) |

| Preinjury level (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Altman et al. [4] | 0% | 0% | 0/2, 0% | Union (2/2, 100%) |

| Preinjury level (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Vanderschot et al. [68] | NA | 0% | 0/2, 0% | Union (2/2, 100%) |

| Preinjury level (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Ebraheim et al. [16] | 0% | Persistent nonunions (1/4, 25%) | 1/4, 25% | Union (3/4, 75%) |

| Preinjury level (4/4, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (4/4, 100%) | ||||

| Matta et al. [39] | Nerve injuries (3/37, 8.1%) | Persistent nonunions (2/37, 5.4%) | 3/37, 8.1% | Union (31/37, 83.8%) |

| Vascular injuries (1/37, 2.7%) | Persistent pain (5/37, 13.5%) | Satisfied patients (32/37, 86.5%) | ||

| Implant failure (4/37, 10.8%) | ||||

| Pavlov et al. [50] | NA | NA | 0/2, 0% | Preinjury level (2/2, 100%) |

| Satisfied patients (2/2, 100%) | ||||

| Hallel and Malkin [31] | NA | NA | 0/1, 0% | Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) |

| Pennal and Massiah [51] | NA | Persistent nonunions (15/42, 35.7%) | NA | Union (25/42, 59.5%) |

| Preinjury level (16/42, 38.1%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (22/42, 52.4%) | ||||

| Elton [18] | NA | 0% | 0/1, 0% | Union (1/1, 100%) |

| Preinjury level (1/1, 100%) | ||||

| Satisfied patients (1/1, 100%) |

* Incidence = rate of each parameter at the specific sample of each study; PE = pulmonary embolus; DVT = deep vein thrombosis; NA = not available.

Recovery of the 437 reviewed patients varied from excellent to very poor. The description and the studied parameters also varied among the different studies. “Good” or “very good” results were recorded in 79.4% of the patients, whereas 15.4% had a “poor” outcome. The success of the attempted reduction was recorded in just three studies [39, 42, 59]. Overall satisfactory reduction (< 1 cm displacement and/or < 15° residual rotational deformity) was reported in 85% of these patients (192 of 249). The worst results were recorded for the partially united pelvic deformities (just 65% with satisfactory reduction) in comparison to the other types of malunion/nonunions [42]. The most noteworthy difficulty was reduction of cranial displacement of the hemipelvis, whereas posterior pelvic prominence mostly was corrected anatomically [42, 59]. Overall, the activity level and walking ability of the patients improved postsurgery. The functional outcome in these series of patients reached the preinjury level in 55.9% overall. Chronic pain attributed to the pelvis, after the therapeutic attempts on the malunion/nonunion sites, was present at the last followup in 7.4% overall. Implant loosening and breakage occurred in 13 cases (3.1%), whereas 25 patients (6.0) required one to three reoperation(s) before achieving a satisfactory final result.

Discussion

The increasing survival rates of patients with severe pelvic trauma dictate a clear understanding of acute management and potential late complications of the trauma. Although symptomatic posttraumatic pelvic nonunion and malalignment are uncommon, their presence typically contributes to a poor functional outcome [49]. The predisposing factors related to the original pelvic injury, clinical presentation, results of operative treatment, and final outcome of these late complications of pelvic fractures represent basic questions of contemporary orthopaedic pelvic trauma; we therefore performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the existing evidence regarding these questions.

The existing evidence of the English and German literature for management of these late complications of pelvic trauma was inadequate, especially its quality [7]. The nature of the collected information (nonexistent controlled studies or randomized trials) and existing discrepancies did not allow for a comparative statistical analysis of the data. Thus, our review can offer only descriptive information regarding the causative factors, management strategies, and outcome of pelvic malunions/nonunions. It was not possible to answer questions regarding the incidence of nonunions/malunions between the different methods of contemporary pelvic fracture fixation, the influence of associated parameters such as additional trauma and mobilization regimes, and the comparative outcome of different methods of pelvic nonunion/malunion management. Nonunions are reported more frequently and disproportionally in comparison to malunions. This discrepancy can be attributed to the difficulties of managing malunited pelvic fractures and the scarcity of specialized centers and surgeons, whereas treatment alternatives of nonunions of the pelvis are more familiar to the average orthopaedic trauma surgeon.

One of the identified causative factors of pelvic nonunion/malunion was the severity of the initial trauma. The high representation of vertical shear pelvic injuries (44.1%) reflects the increased incidence of these complications after grossly unstable pelvic fractures (88.1% were Type C). Motor vehicle accidents were recorded in 51.3% of these cases, falls in 18%, work-related (construction, machinery-related) in 14.3%, and pathologic fractures in 7%, whereas in the population with general pelvic trauma, the incidences of the above mechanisms reportedly are 60%, 30%, 7%, and 2%, respectively [21]. Malunion/nonunions mostly were associated with malreduction of the pelvic ring, instability of displaced fractures associated with rupture of the stabilizing ligaments, lack of adequate initial stabilization of the pelvic ring, major displacement attributable to muscle pull, or soft tissue interposition between the fracture fragments [16, 51]. The nonoperative approach, use of external fixation as definite treatment, and in general, inadequate initial fracture reduction and stabilization were among the most common predisposing factors for development of these complications [39, 42, 47, 51]. These observations may suggest inadequate availability of pelvic trauma expert services, overestimation of the efficacy of external fixation as a definite fixation system [33, 37], and variability of acute management nationally and internationally for patients with pelvic trauma [24, 52, 54].

Uncorrected pelvic deformities after vertically unstable pelvic injuries could lead to leg length discrepancy, gait abnormalities, sitting problems, and low back pain [20, 49]. It is important, however, to ascertain whether the symptoms are related to the pelvic nonunion/deformity rather than to other clinical conditions. Pain from mechanical low back pain, from an old neurologic injury, or dysesthetic pain of neurogenic origin must be excluded [42, 68].

Patients who survive these life-threatening injuries usually do not want additional corrective surgery unless the symptoms are disabling [42]. Many pelvic deformities are well tolerated by the compensatory mobility of the lumbosacral spine and hips [41, 47]. However, when the symptoms of pelvic instability and deformity are established and overwhelming, the only treatment is surgical reconstruction. Indications for early surgical correction include rotational defects greater than 10°, leg length discrepancy greater than 5 mm, and lack of reduction or imperfect facing of sacroiliac articular surfaces [47]. Multistage reconstruction is the most common surgical treatment for pelvic malunions. The sequence, either anterior-posterior-anterior or posterior-anterior-posterior, is individualized in each case. When the deformity is limited to internal/external rotation or medial/lateral displacement without elements of vertical migration, usually a single-stage anterior approach seems sufficient [19, 39, 42]. Provided the posterior release at the first stage is extensive and includes complete section of the sacrospinal and sacrotuberous ligaments together with simultaneous reduction and fixation performed at the same stage with the patient in the supine position, a two-staged procedure is possible even for the most demanding of malunions [59]. Bilateral deformity correction however can be at times impossible [39, 42]. When osteotomies are necessary, the risk for intraoperative complications is considerably increased [39, 42, 59]. The recently proposed pelvic reduction frame of Matta and Yerasimides [40] suggests advancement of available options of surgical tools for treatment of deformed pelvises. Bone grafting in general is used as a void filler and a biologic stimulus for acceleration of bone healing [62]. In these series, it was used in almost all patients with nonunions and also for fusion of the pubic symphysis or the sacroiliac joints whenever this was necessary to achieve stability and restoration of the pelvic anatomy. The gold standard of autograft was the most common choice (87.6%) [1, 11, 16, 19, 25, 32, 39, 40, 42, 43, 47, 51, 59, 61, 68], whereas alternative bone substitutes require additional investigation [25].

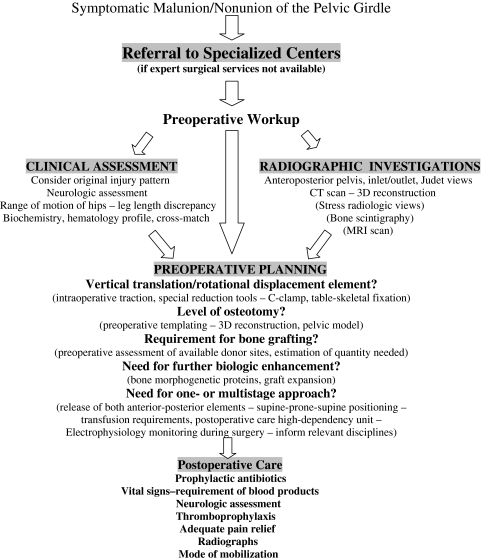

Surgical treatment of pelvic malunion and nonunion is technically demanding and has potential serious complications. The average duration of surgery was more than 6 hours and considerable blood loss was recorded. Despite intraoperative SSEP monitoring [19, 42, 68] and standard thromboprophylaxis, neurologic injuries and venous thromboembolism were the most often recorded postoperative complications. The additional risks of vascular and visceral injuries, infections, implant failures, persistent nonunion, incomplete reduction, and residual malalignment dictate the need for careful preoperative planning and treatment of patients with pelvic trauma in specialized centers by expert surgeons. A clear description of the realistic goals and risks of major complications and compliance of the patient with the postoperative rehabilitation scheme are needed. We describe an algorithm of management of pelvic malunions/nonunions based on the existing evidence and the current clinical practice of our department (Fig. 2). Based on our findings, despite its indisputable difficulties and risks, corrective surgery achieved nonunion healing rates of 86.1%, pain relief in 92.6%, patient satisfaction in 79.4%, and return to preinjury levels of activity in 55.9%. In the case of nonunions, the resolution or major decrease in existing symptoms after surgical correction can be expected in the majority of cases. Symptoms relating to malalignment, including limb shortening, sitting problems, and some nonneurologic urosexual problems directly related to the pelvic deformity, also can be expected to benefit from surgery [25, 39, 42, 47, 59].

Fig. 2.

The flowchart illustrates a proposed algorithm of assessment and management of pelvic malunion/nonunions. CT = computed tomography; 3D = three-dimensional.

The concept of analyzing cumulatively nonunions, malunions, and a combination of the two from mixed series [39, 47], in our opinion, confuses and compromises the reliability of the results. Although nonunions and malunions often require similar treatment (fragment mobilization, débridement/osteotomy, reduction and internal fixation), the intraoperative difficulties and outcomes vary widely. The rationale of Mears and Velyvis [42, 43] of classifying them separately offers a sounder basis for unifying the methodology of future studies to have higher consistency and comparability. Future studies, in addition to adopting this strategy, should incorporate into their analysis health economic parameters, which are currently completely absent from existing studies [22, 30]. The scarcity of these complications, perhaps attributable in part to the gradual improvement of management of acute pelvic trauma, suggests only multicenter prospective/retrospective studies could attain adequate numbers of each type for proper analysis and conclusions and emphasizes the need for establishing national or multinational networks [24, 54] focused on pelvic trauma management and its consequences.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Akagi M, Ikeda N, Fukiage K, Nakamura T. A modification of the retrograde medullary screw for the treatment of bilateral pubic ramus nonunions: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:431–433. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Al-Kharusi W. Update on road traffic crashes: progress in the Middle East. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2457–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Alost T, Waldrop RD. Profile of geriatric pelvic fractures presenting to the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:576–578. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Altman GT, Altman DT, Routt ML Jr. Symptomatic hypertrophic pubic ramus nonunion treated with a retrograde medullary screw. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:582–585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. ATLS, Advanced Trauma Life Support, Students’ Manual. 6th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 1997.

- 6.Beaule PE, Antoniades J, Matta JM. Trans-sacral fixation for failed posterior fixation of the pelvic ring. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bhandari M, Giannoudis PV. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it is not. Injury. 2006;37:302–306. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Starr AJ, Malekzadeh AS. Fractures of the pelvic ring. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown C, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1583–1664.

- 9.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [DOI]

- 10.Dalal SA, Burgess AR, Siegel JH, Young JW, Brumback RJ, Poka A, Dunham CM, Gens D, Bathon H. Pelvic fracture in multiple trauma: classification by mechanism is key to pattern of organ injury, resuscitative requirements, and outcome. J Trauma. 1989;29:981–1000; discussion 1000–1002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.De Boeck H, Yde P, Opdecam P. Non-union of a sacral fracture treated by bone graft and internal fixation. Injury. 1995;26:65–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Delloye C, Banse X, Brichard B, Docquier PL, Cornu O. Pelvic reconstruction with a structural pelvic allograft after resection of a malignant bone tumor. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:579–587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos GC, Alo K, Murray J, Chan L. Pelvic fractures in pediatric and adult trauma patients: are they different injuries? J Trauma. 2003;54:1146–1151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Durkin A, Sagi HC, Durham R, Flint L. Contemporary management of pelvic fractures. Am J Surg. 2006;192:211–223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Eastridge BJ, Burgess AR. Pedestrian pelvic fractures: 5-year experience of a major urban trauma center. J Trauma. 1997;42:695–700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ebraheim NA, Biyani A, Wong F. Nonunion of pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 1998;44:202–204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Egol KA, Kellam JF. Late posterior pelvic instability following chronic insufficiency fracture of the pubic rami. Injury. 2003;34:545–549. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Elton RC. Fracture-dislocation of the pelvis followed by non-union of the posterior inferior iliac spine: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:648–649. [PubMed]

- 19.Frigon VA, Dickson KF. Open reduction internal fixation of a pelvic malunion through an anterior approach. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:519–524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Gautier E, Rommens PM, Matta JM. Late reconstruction after pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27(suppl 2):B39–B46. [PubMed]

- 21.Giannoudis PV, Grotz MR, Tzioupis C, Dinopoulos H, Wells GE, Bouamra O, Lecky F. Prevalence of pelvic fractures, associated injuries, and mortality: the United Kingdom perspective. J Trauma. 2007;63:875–883. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Giannoudis PV, Kanakaris NK. The unresolved issue of health economics and polytrauma: the UK perspective. Injury. 2008;39:705–709. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Giannoudis PV, Pape HC. Trauma and immune reactivity: too much, or too little immune response? Injury. 2007;38:1333–1335. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Giannoudis PV, Pohlemann T, Bircher M. Pelvic and acetabular surgery within Europe: the need for the co-ordination of treatment concepts. Injury. 2007;38:410–415. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Giannoudis PV, Psarakis S, Kanakaris NK, Pape HC. Biological enhancement of bone healing with bone morphogenetic protein-7 at the clinical setting of pelvic girdle non-unions. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl 4):S43–S48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Giannoudis PV, van Griensven M, Tsiridis E, Pape HC. The genetic predisposition to adverse outcome after trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1273–1279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Gilliland MD, Ward RE, Barton RM, Miller PW, Duke JH. Factors affecting mortality in pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 1982;22:691–693. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gurevitz S, Bender B, Tytiun Y, Velkes S, Salai M, Stein M. The role of pelvic fractures in the course of treatment and outcome of trauma patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:623–626. [PubMed]

- 29.Gustavo Parreira J, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, Oliveira A, Fregoneze M, Mercadante M. The role of associated injuries on outcome of blunt trauma patients sustaining pelvic fractures. Injury. 2000;31:677–682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Haentjens P, Annemans L. Health economics and the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hallel T, Malkin C. Fatigue fracture of the pubic ramus following total hip arthroplasty with unusual delayed healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;166:162–164. [PubMed]

- 32.Huegli RW, Messmer P, Jacob AL, Regazzoni P, Styger S, Gross T. Delayed union of a sacral fracture: percutaneous navigated autologous cancellous bone grafting and screw fixation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:502–505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hupel TM, McKee MD, Waddell JP, Schemitsch EH. Primary external fixation of rotationally unstable pelvic fractures in obese patients. J Trauma. 1998;45:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Katsoulis E, Giannoudis PV. Impact of timing of pelvic fixation on functional outcome. Injury. 2006;37:1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Korovessis P, Baikousis A, Stamatakis M, Katonis P. Medium- and long-term results of open reduction and internal fixation for unstable pelvic ring fractures. Orthopedics. 2000;23:1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E. Outcome of operatively treated type-C injuries of the pelvic ring. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:667–678. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E, Bostman O, Santavirta S. Failure of reduction with an external fixator in the management of injuries of the pelvic ring: long-term evaluation of 110 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Madhu TS, Raman R, Giannoudis PV. Long-term outcome in patients with combined spinal and pelvic fractures. Injury. 2007;38:598–606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Matta JM, Dickson KF, Markovich GD. Surgical treatment of pelvic nonunions and malunions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Matta JM, Yerasimides JG. Table-skeletal fixation as an adjunct to pelvic ring reduction. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:647–656. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Mears DC. [Management of pelvic pseudarthroses and pelvic malunion] [in German]. Orthopade. 1996;25:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mears DC, Velyvis J. Surgical reconstruction of late pelvic post-traumatic nonunion and malalignment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Mears DC, Velyvis JH. In situ fixation of pelvic nonunions following pathologic and insufficiency fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:721–728. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Miranda MA, Riemer BL, Butterfield SL, Burke CJ 3rd. Pelvic ring injuries: a long term functional outcome study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:152–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Mock C, Cherian MN. The global burden of musculoskeletal injuries: challenges and solutions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2306–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Oakley MJ, Smith WR, Morgan SJ, Ziran NM, Ziran BH. Repetitive posterior iliac crest autograft harvest resulting in an unstable pelvic fracture and infected non-union: case report and review of the literature. Patient Saf Surg. 2007;1:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Oransky M, Tortora M. Nonunions and malunions after pelvic fractures: why they occur and what can be done? Injury. 2007;38:489–496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Papadopoulos IN, Kanakaris N, Bonovas S, Triantafillidis A, Garnavos C, Voros D, Leukidis C. Auditing 655 fatalities with pelvic fractures by autopsy as a basis to evaluate trauma care. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:30–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Papakostidis C, Kanakaris NK, Kontakis G, Giannoudis PV. Pelvic ring disruptions: treatment modalities and analysis of outcomes. Int Orthop. 2008 May 7. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Pavlov H, Nelson TL, Warren RF, Torg JS, Burstein AH. Stress fractures of the pubic ramus: a report of twelve cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:1020–1025. [PubMed]

- 51.Pennal GF, Massiah KA. Nonunion and delayed union of fractures of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;151:124–129. [PubMed]

- 52.Pohlemann T, Bosch U, Gansslen A, Tscherne H. The Hannover experience in management of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;305:69–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Pohlemann T, Gansslen A, Schellwald O, Culemann U, Tscherne H. Outcome after pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27(suppl 2):B31–B38. [PubMed]

- 54.Pohlemann T, Tosounidis G, Bircher M, Giannoudis P, Culemann U. The German Multicentre Pelvis Registry: a template for an European Expert Network? Injury. 2007;38:416–423. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Poole GV, Ward EF, Muakkassa FF, Hsu HS, Griswold JA, Rhodes RS. Pelvic fracture from major blunt trauma: outcome is determined by associated injuries. Ann Surg. 1991;213:532–538; discussion 538–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Prevezas N. Evolution of pelvic and acetabular surgery from ancient to modern times. Injury. 2007;38:397–409. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Roberts CS, Pape HC, Jones AL, Malkani AL, Rodriguez JL, Giannoudis PV. Damage control orthopaedics: evolving concepts in the treatment of patients who have sustained orthopaedic trauma. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:447–462. [PubMed]

- 58.Rommens PM, Hessmann MH. Staged reconstruction of pelvic ring disruption: differences in morbidity, mortality, radiologic results, and functional outcomes between B1, B2/B3, and C-type lesions. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Rousseau MA, Laude F, Lazennec JY, Saillant G, Catonne Y. Two-stage surgical procedure for treating pelvic malunions. Int Orthop. 2006;30:338–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Ryan R, Hill S, Broclain D, Horey D, Oliver S, Prictor M. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. Study Quality Guide. Available at: www.latrobe.edu.au/cochrane/resources.html. Accessed October 10, 2008.

- 61.Schofer M, Illian C, Fuchs-Winkelmann S, Kortmann HR. [Pseudoarthrosis of anterior pelvic ring fracture] [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2008;111:264, 266–267. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Sen MK, Miclau T. Autologous iliac crest bone graft: should it still be the gold standard for treating nonunions? Injury. 2007;38[Suppl 1]:S75–S80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Tile M, Pennal GF. Pelvic disruption: principles of management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;151:56–64. [PubMed]

- 64.Tornetta P 3rd, Dickson K, Matta JM. Outcome of rotationally unstable pelvic ring injuries treated operatively. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:147–151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Tornetta P 3rd, Matta JM. Outcome of operatively treated unstable posterior pelvic ring disruptions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;329:186–193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Totterman A, Glott T, Madsen JE, Roise O. Unstable sacral fractures: associated injuries and morbidity at 1 year. Spine. 2006;31:E628–E635. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.van den Bosch EW, van der Kleyn R, van Zwienen MC, van Vugt AB. Nonunion of unstable fractures of the pelvis. Eur J Trauma. 2002;28:100–103. [DOI]

- 68.Vanderschot P, Daenens K, Broos P. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic pelvic deformities. Injury. 1998;29:19–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Westphal T, Piatek S, Winckler S. [Pseudarthrosis of an occult fracture in zone III of the sacrum] [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 1999;102:493–496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Whitbeck MG Jr, Zwally HJ 2nd, Burgess AR. Innominosacral dissociation: mechanism of injury as a predictor of resuscitation requirements, morbidity, and mortality. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:S57–S63. [PubMed]