Abstract

Carboxylic ester hydrolyzing enzymes constitute a large group of enzymes that are able to catalyze the hydrolysis, synthesis or transesterification of an ester bond. They can be found in all three domains of life, including the group of hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea. Esterases from the latter group often exhibit a high intrinsic stability, which makes them of interest them for various biotechnological applications. In this review, we aim to give an overview of all characterized carboxylic ester hydrolases from hyperthermophilic microorganisms and provide details on their substrate specificity, kinetics, optimal catalytic conditions, and stability. Approaches for the discovery of new carboxylic ester hydrolases are described. Special attention is given to the currently characterized hyperthermophilic enzymes with respect to their biochemical properties, 3D structure, and classification.

Keywords: Carboxylic ester hydrolase, Esterase, Lipase, Hyperthermophile, Biochemical properties, Structure, Classification, Review

Introduction

The synthesis of specific products by enzymes is a fundamental aspect of modern biotechnology. This biocatalytic approach has several advantages over traditional chemical engineering, such as higher product purity, fewer waste products, lower energy consumption, and more selective reactions due to the high regio- and stereo-selectivity of enzymes (Rozzell 1999). One of the industrially most exploited and important groups of biocatalysts are the carboxylic ester hydrolases (EC 3.1.1.x) (Jaeger and Eggert 2002; Hasan et al. 2006).

Carboxylic ester hydrolases are ubiquitous enzymes, which have been identified in all domains of life (Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes), and in some viruses. In the presence of water, they catalyze the hydrolysis of an ester bond resulting in the formation of an alcohol and a carboxylic acid. However, in an organic solvent, they can catalyze the reverse reaction or a trans-esterification reaction (Fig. 1) (Krishna and Karanth 2002). Most carboxylic ester hydrolases belong to the α/β-hydrolase family, and share structural and functional characteristics, including a catalytic triad, an α/β-hydrolase fold, and a co-factor independent activity. The catalytic triad is conserved and is usually composed of a nucleophilic serine in a GXSXG pentapeptide motif (where X is any residue), and an acidic residue (aspartate or glutamate) that is hydrogen bonded to a histidine residue (Heikinheimo et al. 1999; Jaeger et al. 1999; Nardini and Dijkstra 1999; Bornscheuer 2002).

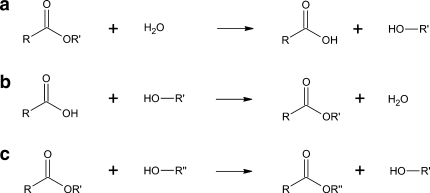

Fig. 1.

Reactions catalyzed by carboxylic ester hydrolases: a hydrolysis, b esterification, and c transesterification

There are two well-known groups within the family of carboxylic ester hydrolases: lipases and esterases. Esterases differ from lipases by showing a preference for short-chain acyl esters (shorter than 10 carbon atoms) and that they are not active on substrates that form micelles (Chahinian et al. 2002). Other groups include, for instance, arylesterases and phospholipases. The physiological role of carboxylic ester hydrolases is often not known, but nevertheless, many have found applications in industry; amongst other in medical biotechnology, detergent production, organic synthesis, biodiesel production, flavor and aroma synthesis, and other food related processes (Panda and Gowrishankar 2005; Salameh and Wiegel 2007a).

The use of enzymes in industrial processes also has its restrictions. Many processes are operated at elevated temperatures or in the presence of organic solvents. These conditions are detrimental to most enzymes and therefore there is a growing demand for enzymes with an improved stability. In this regard, especially, enzymes from hyperthermophiles are promising candidates because these enzymes generally display a high intrinsic thermal and chemical stability (Gomes and Steiner 2004). In recent years, many new hyperthermophiles have been isolated and the genomes of a rapidly increasing number have been completely sequenced. Hyperthermophiles have proven to be a good source of new enzymes (Atomi 2005; Egorova and Antranikian 2005; Unsworth et al. 2007), including many putative esterases and lipases.

At this moment, most esterases and lipases used in the industry are from mesophiles, basically, because they were the first to be identified and characterized. Esterases and lipases have only been isolated from a small number of hyperthermophiles (Table 1). An excellent review on thermostable carboxylesterases from hyperthermophiles appeared in 2004 (Atomi and Imanaka 2004). However, since then, many new hyperthermophilic carboxylic ester hydrolases have been described. Therefore, in this review, we aim to present an overview of the currently characterized carboxylic ester hydrolases from hyperthermophiles. We will focus on the identification of new carboxylic ester hydrolases, the biochemical properties, and 3D structures of characterized enzymes, and their classification. For details on the application of these enzymes, we refer to other reviews that cover this aspect extensively (Atomi 2005; Hasan 2006; Salameh and Wiegel 2007a).

Table 1.

List of completely sequenced hyperthermophiles (T-optimum > 80°C) and extreme thermophiles (no growth <50°C)

| Organism | Genome size (bp) | Number of ORFs | GC content (%) | Optimal growth (°C) | Esterases isolated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | |||||

| Aquifex aeolicus VF5 | 1551335 | 1529 | 43.5 | 90 | |

| Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus DSM 8903 | 2970275 | 2679 | 35.3 | 70a | |

| Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis MB4T/JCM 11007 | 2689445 | 2588 | 37.6 | 75a | + |

| Thermotoga lettingae TMO | 2135342 | 2040 | 38.7 | 65a | |

| Thermotoga maritima MSB8 | 1860725 | 1858 | 46.2 | 80 | + |

| Thermotoga petrophila RKU-1 | 1823511 | 1785 | 46.1 | 80 | |

| Thermotoga sp. RQ2 | 1877693 | 1819 | 46.2 | 76–82 | |

| Thermus thermophilus HB8 | 1849742 | 1973 | 69.4 | 75a | + |

| Thermus thermophilus HB27 | 1894877 | 1982 | 66.6 | 68a | + |

| Archaea | |||||

| Aeropyrum pernix K1 | 1669695 | 1700 | 56.3 | 90 | + |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus VC-16 | 2178400 | 2420 | 48.6 | 82 | + |

| Desulfurococcus kamchatkensis 1221n | 1365223 | 1475 | – | 85 | |

| Hyperthermus butylicus DSM 5456 | 1667163 | 1602 | 53.7 | 95–106 | |

| Methanocaldococcus jannaschii DSM 2661 | 1739933 | 1729 | 31.4 | 85 | |

| Methanopyrus kandleri AV19 | 1694969 | 1687 | 61.2 | 98 | |

| Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus Delta H | 1751377 | 1873 | 49.5 | 65–70a | |

| Nanoarchaeum equitans Kin4-M | 490885 | 536 | 31.6 | 90 | |

| Pyrobaculum aerophilum IM2 | 2222430 | 2605 | 51.4 | 100 | |

| Pyrobaculum arsenaticum PZ6 | 2121076 | 2298 | 58.3 | 95 | |

| Pyrobaculum calidifontis JCM 11548 | 2009313 | 2149 | 57.2 | 90–95 | + |

| Pyrobaculum islandicum DSM 4184 | 1826402 | 1978 | 49.6 | 100 | |

| Pyrococcus abyssi GE5 | 1765118 | 1896 | 44.7 | 103 | + |

| Pyrococcus furiosus DSM 3638 | 1908256 | 2125 | 40.8 | 100 | + |

| Pyrococcus horikoshii OT3 | 1738505 | 1955 | 41.9 | 98 | |

| Staphylothermus marinus F1 | 1570485 | 1570 | 35.7 | 92 | |

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius DSM 639 | 2225959 | 2292 | 36.7 | 70–75a | + |

| Sulfolobus tokodaii 7, JCM 10545 | 2694756 | 2825 | 32.8 | 80 | + |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | 2992245 | 2977 | 35.8 | 80 | + |

| Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 | 1847607 | 1976 | 51.3 | 80 | |

| Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 | 2088737 | 2306 | 52.0 | 85 | |

| Thermofilum pendens Hrk 5 | 1781889 | 1824 | 57.7 | 88 | |

| Thermoproteus neutrophilus V24Sta | 1769823 | 1966 | 59.9 | 85 | |

Information concerning completely sequenced genomes and on-going sequence projects can be obtained at the GOLD Genomes Online Database (http://www.genomesonline.org) (Liolios et al. 2008)

aExtreme thermophiles that are related to hyperthermophiles

Hyperthermophiles

Hyperthermophiles are generally defined as micro-organisms that grow optimally at temperatures above 80°C (Stetter 1996). They have been isolated from both terrestrial and marine environments, such as sulfur-rich solfataras (pH ranging from slightly alkaline to extremely acidic), hot springs, oil-field waters, and hydrothermal vents at the ocean floor. Consequently, they show a broad physiological diversity, ranging from aerobic respirers to methanogens and saccharolytic heterotrophs (Stetter 1996; Vieille and Zeikus 2001). Hyperthermophiles can be found in both prokaryotic domains, viz. the Bacteria and the Archaea. In phylogenetic trees based on 16S rRNA, they occupy the shortest and deepest lineages, suggesting that they might be closely related to the common ancestor of all extant life (Stetter 2006). For this reason and because they are a potential source of new biocatalysts, the genomes of several hyperthermophiles have been completely sequenced (Table 1).

All biomolecules of hyperthermophiles must be stabilized against thermal denaturation. The simplest approach for DNA stabilization would be to increase the GC-content of the DNA. However, it has been established that the GC-content of hyperthermophiles does not correlate with the optimal growth temperatures (Table 1). Instead, other mechanisms are used to stabilize DNA, such as an increased intracellular electrolyte concentration, cationic DNA-binding proteins, and DNA supercoiling (Unsworth et al. 2007). Thus far, all completely sequenced hyperthermophiles have a reverse gyrase catalyzing a positive supercoiling of their DNA. A reverse gyrase is, however, not a prerequisite for hyperthermophilic life, but it can be seen as a marker for growth at high temperatures (Atomi et al. 2004).

Proteins from hyperthermophiles have also been optimized for functioning at elevated temperatures. There is no single mechanism responsible for the stability of these hyperthermophilic proteins, rather, it can be attributed to multiple features. Features that contribute to the stability of hyperthermophilic enzymes include (a) changes in amino acid composition, such as a decrease in the thermolabile residues asparagine and cysteine, (b) increased hydrophobic interactions, (c) an increased number of ion pairs and salt bridge networks, (d) reduction in the size of surface loops and of solvent-exposed surface, (e) as well as increased intersubunit interactions and oligomeric state (Vieille and Zeikus 2001; Robinson-Rechavi et al. 2006; Unsworth et al. 2007). Besides these structural adaptations, proteins can also be stabilized by intracellular solutes, metabolites, and sugars (Santos and da Costa 2002).

Biomining for new enzymes

Traditionally, new biocatalysts were discovered by a cumbersome screening of a wide variety of organisms for the desired activity. A modern variant is the metagenomics approach, which involves the extraction of genomic DNA from environmental samples, its cloning into suitable expression vectors, and subsequent screening of the constructed libraries (Lorenz and Eck 2005). This approach has been successfully applied to isolate new biocatalysts, including carboxylic ester hydrolases from hyperthermophiles (Rhee et al. 2005; Tirawongsaroj et al. 2008). This approach can potentially result in unique enzymes (no sequence similarity), but obviously depends on functional expression. At present, with many complete genome sequences available, bioinformatics has become an important tool in the discovery of new biocatalysts. This is a high-throughput approach for the identification, and in silico functional analysis, of more or less related sequences encoding potential biocatalysts. Sequence similarity, based on sequence alignments and motif searches, is most commonly used for assigning a function to new proteins (Kwoun Kim et al. 2004).

Many sequences in the available databases have already been annotated as putative esterase or lipase. However, even more carboxylic ester hydrolases can be identified when BLAST and Motif searches, in combination with pair-wise comparison with sequences of known carboxylic ester hydrolases, are used. The advantage of this approach compared to traditional activity screening is the direct identification of new and diverse carboxylic ester hydrolases, which would otherwise have not been detected due to a low level of expression.

Such a bioinformatics approach has been successfully applied to identify new carboxylic ester hydrolase sequences in the completely sequenced genomes of several selected hyperthermophiles. In order to have as many candidates as possible, sequences that were assigned a different function, but did have the characteristics of carboxylic ester hydrolases, were also included, such as acylpeptide hydrolases. The results are given in Table 2. A typical strategy includes: BLAST-P searches (Altschul et al. 1997) using sequences of known carboxylic ester hydrolases as template; in parallel, searching InterPro (Hunter et al. 2009) for potential candidates. The resulting sequences can then be further analyzed (for conserved motifs and domains) using the NCBI Conserved Domain Search (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2009).

Table 2.

Identified sequences of potential carboxylic ester hydrolases in selected genomes

| Microorganism | Locus tag | Genbank | Annotation (NCBI) | Residues | GXSXG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aeropyrum pernix | APE1244 | BAA80234 | Hypothetical protein | 583 | GVSMG |

| APE1832 | BAA80835 | Acylpeptide hydrolase/Esterase | 659 | GGSYG | |

| APE2361 | BAA81374 | Hydrolase, putative | 279 | GFSLG | |

| APE2441 | BAA81456 | Acylpeptide hydrolase/Esterase | 595 | GGSYG | |

| Hyperthermus butylicus | Hbut_1071 | ABM80914 | Hypothetical protein | 226 | GLSVG |

| Pyrobaculum aerophilum | PAE2936 | AAL64548 | Hypothetical protein | 194 | GPSAS |

| PAE3573 | AAL65014 | Hypothetical protein | 196 | GHSMG | |

| Pyrobaculum calidifontis | Pcal_1307 | ABO08731 | Alpha/beta hydrolase | 313 | GDSAG |

| Pcal_1997 | ABO09412 | Hypothetical protein | 198 | GHSMG | |

| Pyrococcus abyssi | PAB1050 | CAB50498 | Lysophospholipase, putative | 259 | GHSLG |

| PAB2176 | CAB49187 | Hypothetical esterase | 286 | GFSMG | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus | SSO0102 | AAK40458 | Esterase, tropinesterase | 231 | GHSIG |

| SSO2262 | AAK42427 | Hypothetical protein | 197 | GASMG | |

| SSO2518 | AAK42649 | Esterase, putative | 353 | GESFG | |

| SSO2521 | AAK42652 | Lipase | 311 | GDSAG | |

| SSO2979 | AAK43083 | Hypothetical protein | 320 | GHSSG | |

| SSO3052 | AAK43152 | Hypothetical protein | 210 | GISGN | |

| Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis | TTE0035 | AAM23348 | Hypothetical protein | 237 | GDSIS |

| TTE0419 | AAM23703 | Lysophospholipase | 314 | GHSFG | |

| TTE0552 | AAM23828 | Predicted hydrolase | 279 | GVSMG | |

| TTE0556 | AAM23832 | Predicted hydrolase | 298 | GWSMG | |

| TTE1809 | AAM25001 | Alpha/beta hydrolase | 258 | GLSMG | |

| TTE2321 | AAM25462 | Alpha/beta hydrolase | 414 | CHSMG | |

| TTE2547 | AAM25672 | Alpha/beta hydrolase | 285 | AHSFG | |

| Thermococcus kodakaraensis | TK0522 | BAD84711 | Carbohydrate esterase | 449 | GSSLG |

| Thermotoga maritima | TM1022 | AAD36099 | Esterase | 253 | GLSMG |

| TM1160 | AAD36236 | Esterase | 306 | GLSAG | |

| TM1350 | AAD36421 | Lipase, putative | 259 | GHSLG |

Properties of characterized esterases

The first carboxylic ester hydrolase isolated and characterized from a hyperthermophile was a carboxylesterase from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (Sobek and Gorisch 1988, 1989). Since then, many new esterases have been characterized. At this moment, most carboxylic ester hydrolases described from hyperthermophiles are esterases, and only recently the first lipase from a hyperthermophile was identified (Levisson et al., manuscript in preparation). Esterases have been characterized from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, Thermotoga maritima, Thermus thermophilus, Aeropyrum pernix, Archaeoglobus fulgidus, Picrophilus torridus, Pyrobaculum calidifontis, Pyrococcus abyssi, Pyrococcus furiosus, Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, Sulfolobus shibatae, Sulfolobus solfataricus, Sulfolobus tokodaii, and from metagenomic libraries (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biochemical properties of characterized carboxylic ester hydrolases

| Microorganism | Enzyme | Locus tag | Preferred substrate | KM (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (s−1 × μM) | Topt (°C) | Optimal pH | Stability | Molecular mass (kDa) | PDB | Referencesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||||||||||

| Thermotoga maritima | Esterase | TM0033 | pNP-C2 | 105 | 115 | 1.095 | 95+ | 8.5 | Half-life of 1.5 h at 100°C | 267 (α6) | 3DOH | Sun et al. (2007), Levisson et al. (2009) |

| pNP-C8 | 27 | 37 | 1.370 | 3DOI | ||||||||

| Thermotoga maritima | Esterase | TM0053 | pNP-C10 | 3.1 | 11 | 3.5 | 60 | 7 | Retained 50% activity after 30 min at 80°C | 40 | Kakugawa et al. (2007) | |

| Thermotoga maritima | Esterase | TM0053 | pNP-C8 | NR | NR | NR | 90 | 9 | NR | 38.5 | Levisson et al. (unpublished results) | |

| Thermotoga maritima | Acetyl esterase | TM0077 | pNP-C2 | 185 | 57.5 | 0.311 | 100+ | 7.5 | Half-life of 2 h at 90°C | 222 (α6) | 1VLQ | Levisson et al. (manuscript in preparation) |

| Thermotoga maritima | Esterase | TM0336 | pNP-C5 | 66 | 10.2 | 0.155 | 95+ | 7 | Half-life of 1 h at 100°C | 44.5 (α1) | Levisson et al. (2007) | |

| Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis | Esterase | TTE0555 | pNP-C3/C4 | NR | NR | NR | 70 | 9 | Half-life of 1.5 h at 70°C | 43 | Zhang et al. (2003) | |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica | Lipase (LipA) | NR | pNP-C12 | NR | NR | NR | 96 | 9.4 | Retained 50% activity after 6 h at 100°C | 50 | Salameh and Wiegel (2007b) | |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica | Lipase (LipB) | NR | pNP-C12 | NR | NR | NR | 96 | 9.6 | Retained 50% activity after 2 h at 100°C | 57 | Salameh and Wiegel (2007b) | |

| Thermus thermophilus HB8 | Putative esterase | TT1662 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 26 | 1UFO | Murayama et al. (2005) |

| Thermus thermophilus species | Esterases | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 80 | NR | NR | 34/62 | Dominguez et al. (2004, 2005, 2007), Fucinos et al. (2005a, b, 2008) | |

| Archaea | ||||||||||||

| Aeropyrum pernix | Esterase/ Acylpeptide hydrolase | APE1547 | pNP-C8 | 43.3 | 6.6 | 0.152 | 90 | 8 | Half-life of 160 h + at 90°C | 63 (α1) | 1VE6, 1VE7 | Gao et al. (2003, 2006); Bartlam et al. (2004); Wang et al. (2006); Zhang et al. (2006, 2007, 2008; Yang et al. (2009) |

| Aeropyrum pernix | Phospholipase/ Esterase | APE2325 | pNP-C3 | 103 | 39 | NR | 90 | NR | Half-life of 1 h at 100°C | 18 | Wang et al. (2004) | |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Esterase | AF1041 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Ro et al. (2004) | ||

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Esterase | AF1716 | pNP-C6 | 11 | 1014 | 92 | 80 | 7.1 | Half-life of 1 h at 85°C | 35.5 | 1JJI | D’Auria et al. (2000); Manco et al. (2000a, b, 2002); De Simone et al. (2001); Del Vecchio et al. (2002, 2003, 2009); Ro et al. (2004) |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Esterase | AF1763 | pNP-C18 | 876 | 47.5 | 0.054 | 70 | 10–11 | Retained 40% activity after 30 min at 40°C | 53 | Rusnak et al. (2005) | |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Lipase | AF1763 | pNP-C10 | NR | NR | NR | 95 | 11 | Half-life of 10 h at 80°C | 51 | Levisson et al. (manuscript in preparation) | |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Esterase | NR | pNP-C4 | NR | NR | NR | 70 | 7–8 | Retained 10% activity after 3 h at 90°C | 27.5 | Kim et al. (2008) | |

| Picrophilus torridus | Esterase (EstA) | PTO0988 | pNP-C2 | NR | NR | NR | 70 | 6.5 | Half-life of 21 h at 90°C | 66 (α3) | Hess et al. (2008) | |

| Picrophilus torridus | Esterase (EstB) | PTO1141 | pNP-C2 | NR | NR | NR | 55 | 7 | Half-life of 10 h at 90°C | 81(α3) | Hess et al. (2008) | |

| Pyrobaculum calidifontis | Esterase | NR | pNP-C6 | 44.4 | 2620 | 59 | 90 | 7 | Half-life of 56 min at 110°C | 98 (α3) | Hotta et al. (2002) | |

| Pyrococcus abyssi | Esterase | NR | pNP-C5 | NR | NR | NR | 65–74 | NR | Half-life of 22 h at 99°C half-life of 13 min at 120°C | NR | Cornec (1998) | |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Esterase | NR | 4MU-C2 | NR | NR | NR | 100 | 7.5 | Half-life of 34 h at 100°C Half-life of 2 h at 120°C | NR | Ikeda and Clark (1998) | |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Lysophospholipase/ Esterase | PF0480 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 70 | 7 | NR | 64 (α2) | Chandrayan et al. (2008) | |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Esterase | PF2001 | 4MU-C7 | NR | NR | NR | 60 | 7 | Retained 100% activity after 2 h at 75°C | 48 | Almeida et al. (2006, 2008) | |

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius | Esterase | NR | pNP-C5 | 151.7 | NR | NR | NR | 7.5–8.5 | Retained 50% activity after 1 h at 100°C | 128 (α4) | Sobek and Gorisch (1988); (1989) | |

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius | Esterase | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Half-life of 45 min at 80°C | NR | Arpigny et al. (1998) | |

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius | Phosphotriesterase | SACI2140 | Methyl-paraoxon | 1400 | 7.75 | 5.57 × 10−3 | 75 | 9 | Retained 65% activity after 2 h at 85°C | 69 (α2) | Porzio et al. (2007) | |

| Sulfolobus shibatae | Esterase | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 90 | 6 | Half-life of 20 min at 120°C | NR | Huddleston et al. (1995) | |

| Sulfolobus shibatae | Esterase | NR | pNP-C4 | 10 | NR | NR | NR | 7–8 | Retained 70% activity after 30 min at 90°C | 90 (α3) 64 (α2) | Ejima et al. (2004) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus MT4 | Esterase | NR | pNP-C5 | NR | NR | NR | 90+ | 6.5–7 | Half-life of 7 h at 90°C | 114 (α4) | Morana et al. (2002) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus MT4 | Phosphotriesterase | NR | Methyl-paraoxon | 205 | 1.3 | 6.34 × 10−3 | 95+ | 7–9 | Half-life of 1.5 h at 100°C | 35 | 2VC5 VC7 | Merone et al. (2005); Elias et al. (2007); Porzio et al. (2007); Elias et al. (2008) |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P1 | Esterase | NR | 4MU-C2* pNP-C6 | 45* | 1000* | 2.2* | 95+ | 7.7 | NR | 33 (α1) | Sehgal et al. (2001, 2002); Sehgal and Kelly (2002, 2003) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P1 | Esterase | NR | pNP-C8 | 71 | 14700 | 207.1 | 85 | 8 | Retained 41% activity after 120 h at 80°C | 34 (α1) | Park et al. (2006) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P1 | Aryl esterase | NR | Paraoxon | 5 | 597 | 119.4 | 94 | 7 | Retained 52% activity after 50 h at 90°C | 35 (α1) | Park et al. (2008) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | Esterase | SSO2493 | pNP-C5 | 2100 | 46.3 | 21.1 × 10−3 | 80 | 7.4 | Half-life of 40 min at 80°C | 96 (α3) | Kim and Lee (2004) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | Esterase | SSO2517 (SsoN∆) | pNP-C6 | 50 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 70 | 7.1 | NR | NR | Mandrich et al. (2005, 2007) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | Esterase | SSO2517 (SsoN∆long) | pNP-C6 | 30 | 34.5 | 1.15 | 85 | 6.5 | NR | 34 | Mandrich et al. (2007) | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 | Esterase | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 75 | 8 | Half-life of 15 min at 100°C | 100 | Chung et al. (2000) | |

| Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7 | Esterase | ST0071 | pNP-C4 | 0.53 | 127 | 0.239 | 70 | 8 | Half-life of 40 min at 85°C | 34 | Suzuki et al. (2004) | |

| Metagenomic | ||||||||||||

| Metagenomic library | Esterase | NR | pNP-C6 | 700 | 1600 | 2.29 | 95+ | 6 | Half-life of 20 min at 90°C | 34 | 2C7B | Rhee et al. (2005, 2006); Byun et al. (2006, 2007) |

| Metagenomic library | Phospholipase | NR | pNP-C4 | 140 | 574 | 4.101 | 70 | 9 | Retained 50% activity after 2 h at 80°C | 32 | Tirawongsaroj et al. (2008) | |

| Metagenomic library | Esterase | NR | pNP-C5 | 120 | 110 | 0.921 | 70 | 9 | Retained 50% activity after 30 min at 80°C | 29 | Tirawongsaroj et al. (2008) | |

pNPp-nitrophenyl ester, 4MU 4-methylumbelliferyl ester

aReferences contain all current literature concerning the enzymes in this table

Substrate preference

Enzymes are classified and named according to the type of reaction they catalyze (Enzyme Commission). The carboxylic ester hydrolases catalyze the hydrolysis of carboxylic acid esters, but they can be further clustered into different groups based on their substrate of preference. Two well-known members of this family are the esterases and true lipases. The majority of the characterized hyperthermophilic carboxylic ester hydrolases are esterases. Lipases have been described for many mesophiles, mainly microbial and fungal, and are exploited for biotechnological applications (Gupta et al. 2004; Hasan et al. 2006). However, until recently no true lipase, hydrolyzing long-chain fatty acid esters, had been identified in hyperthermophiles. The first lipase was characterized from the archaeon A. fulgidus (Levisson et al., manuscript in preparation) (Table 3). This lipase shows maximal activity at a temperature of 95°C and has a half-life of 10 h at 80°C. It displays highest activity with p-nitrophenyl-decanoate (pNP-C10) and is capable of hydrolyzing triacylglycerol esters of butyrate (C4), octanoate (C8), palmitate (C16), and oleate (C18). Two lipases from the thermophile T. lipolytica, LipA and LipB, have been characterized and are very stable at high temperatures (Salameh and Wiegel 2007b). Both enzymes show maximal activity at 96°C and have the highest activity with the triacylglycerol ester trioleate and pNP-C12. LipA and LipB retained 50% of their activity after 6 and 2 h incubation at 100°C, respectively, indicating that these two lipases are the most thermostable ones so far reported. Unfortunately, attempts to clone the two lipases were unsuccessful. A few mesophilic lipases may operate at temperatures above 80°C, but they usually have short half-lives. An exception is a mesophilic lipase that was isolated from a Pseudomonas sp., which showed a half-life of over 13 h at 90°C (Rathi et al. 2000). In comparison, the well-known lipase B from Candida antartica (CALB, Novozym 435) has a half-life of only 2 h at 45°C (Suen et al. 2004).

Esterases have a preference for short to medium acyl-chain esters (Table 3). Several enzymes from hyperthermophiles have been tested for activity toward esters with various alcoholic moieties other than the standard pNP-esters or 4-methylumbelliferyl (4MU) esters (Fig. 2). The esterase from P. calidifontis displays activity toward different acetate esters and showed highest activity on iso-butyl acetate (Hotta et al. 2002). Furthermore, it was able to hydrolyze sec- and tert-butyl acetate. At present, only few enzymes can catalyze the hydrolysis or the synthesis of tertiary esters. This is because known esterases and lipases cannot hydrolyze esters containing a bulky substituent near the ester carbonyl group.

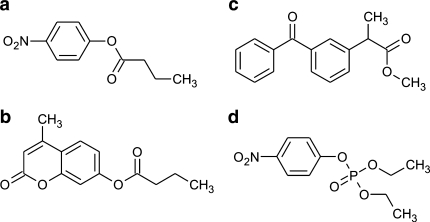

Fig. 2.

Substrates commonly used to test for esterase activity: ap-nitrophenyl butyrate, b 4-methylumbelliferyl butyrate, c (R/S)-ketoprofen methyl ester, and dp-nitrophenyl diethyl phosphate

Other esterases have been characterized for their ability to resolve mixtures of chiral esters. The kinetic resolution of the esterase Est3 from S. solfataricus P2 was investigated using (R,S)-ketoprofen methyl ester (Fig. 2) (Kim and Lee 2004). The enzyme hydrolyzed the (R)-ester of racemic ketoprofen methylester and showed an enantiomeric excess of 80% with a conversion rate of 20% in 32 h. In another study, the esterase Sso-Est1 from S. solfataricus P1 (Sehgal et al. 2001) was identified as homolog to the mesophilic Bacillus subtilis ThaiI-8 esterase (CNP) (Quax and Broekhuizen 1994) and Candida rugosa lipase (CRL) (Lee et al. 2001), which are used for the chiral separation of racemic mixtures of 2-arylpropionic methyl esters. The enzyme was characterized biochemically for its ability to resolve mixtures of (R,S)-naproxen methyl ester under a variety of reaction environments (Sehgal and Kelly 2002, 2003). Sso-Est1 showed a specific reaction toward the (S)-naproxen ester in co-solvent reaction conditions with an enantiomeric excess of ≥90%.

In addition to esterases and lipases, other ester hydrolase types have been identified in hyperthermophiles, including two phosphotriesterases and an arylesterase that were found in S. acidocaldarius, S. solfataricus MT4 and P1, respectively (Merone et al. 2005; Porzio et al. 2007; Park et al. 2008). The phosphotriesterases showed maximal activity on the organophosphate methyl-paraoxon (dimethyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate) and the arylesterase showed maximal activity on paraoxon (diethyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate) (Fig. 2; Table 3). Besides this phospho-esterase activity, esterase activity (on pNP-esters) was also observed for both enzymes. Stable organophosphate-degrading enzymes are of great interest for the detoxification of chemical warfare agents and agricultural pesticides.

Stability against chemicals

Stability and activity in the presence of organic solvents and detergents are important properties of an enzyme if it is to be used as a biocatalyst in the industry. Several hyperthermophilic carboxylic ester hydrolases have been tested. The esterase from P. calidifontis (Hotta et al. 2002) displays high stability in water-miscible organic solvents, and exhibited activity in 50% solutions of DMSO, methanol, acetonitrile, ethanol, and 2-propanol. In addition, the enzyme retained almost full activity after 1 h incubation in the presence of the above-mentioned organic solvents at a concentration of 80%. In comparison, the lipases from the mesophiles Pseudomonas sp. B11-1 (Choo et al. 1998) and Fusarium heterosporum (Shimada et al. 1993) were completely inactivated after incubation with acetonitrile. In addition to stability against solvents, the Pyrobaculum enzyme also has high thermal stability, with a half-life of approximately 1 h at 110°C (Table 3). The esterase from S. solfataricus P1 (Park et al. 2006) also displayed good stability against organic solvents, comparable to the enzyme from P. calidifontis. In addition, addition of 5% non-ionic detergents, such as Tween 20, stabilized the Sulfolobus enzyme. Moreover, the enzyme retained 45 and 98% activity in the presence of 5% SDS and 8 M urea, respectively. The lipase from the mesophile Penicillium expansum shows a much lower stability against detergents or organic solvents (Stocklein et al. 1993). The esterase EstD from T. maritima (Levisson et al. 2007) does not display resistance to detergents and retained only 0 and 43% activity in the presence of 1% (w/v) SDS and 1% (v/v) Tween 20, respectively. However, EstD does show good resistance against organic solvents since it remained active in the presence of 10% (v/v) solvents, which is comparable to the esterase from P. calidifontis. The esterase Est3 from S. solfataricus P2 displayed good resistance against mild detergents (Kim and Lee 2004), it retained 51 and 99%, respectively, activity in the presence of 10% (w/v) Tween 60 and 10% (w/v) Tween 80, but displayed lower stability against organic solvents than the other three esterases described above.

Thermal stability

The most thermostable carboxylic ester hydrolase described to date is an esterase from P. furiosus (Ikeda and Clark 1998) (Table 3). It is extremely stable with half-lives of 34 and 2 h at 100 and 120°C, respectively. The enzyme has optimal activity at a temperature of 100°C, which is in good agreement with the optimal growth temperature of Pyrococcus (100°C). Highest activity was obtained with the substrate MU-C2, however, also little activity toward pNP-C18 was detected indicating it has a very broad substrate tolerance. Another very stable esterase was detected in crude extracts of P. abyssi (Cornec 1998). This enzyme has a half-life of 22 h and 13 min at 99 and 120°C, respectively. Maximal esterase activity was observed at least 65–74°C, however, temperatures above 74°C were not investigated due to instability of the substrate. The enzyme is active on a broad range of substrates, capable of hydrolyzing triacylglycerol esters and aromatic esters, but is restricted to short acyl chain esters of C2–C8 with an optimum for C5 fatty acid esters. Unfortunately, no sequence information has been reported for both Pyrococcus esterases. Most of the characterized carboxylic ester hydrolases from hyperthermophiles are optimally active at temperatures between 70 and 100°C (Table 3), which is often close to or above the host organism’s optimal growth temperature. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that some carboxylic ester hydrolases, such as the esterase from S. shibatae (Huddleston et al. 1995) and the acetyl esterase from T. maritima (Levisson et al., manuscript in preparation), after heterologous expression in E. coli, show a transient activation during stability incubations, indicating that they probably need a high temperature in order to fold properly. Compared to their mesophilic counterparts they perform similar functions, however, due to intrinsic differences hyperthermophilic enzymes are stable and can operate at higher temperatures. It is difficult to indicate exactly which factors contribute to this higher thermal stability since (as discussed before) many different factors are involved.

Structures

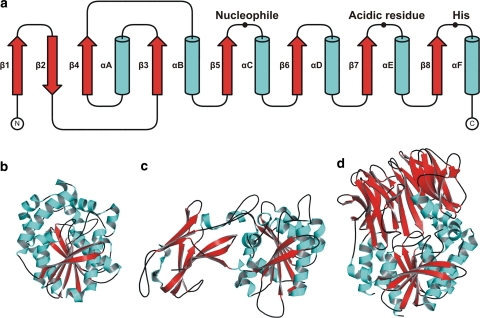

Most carboxylic ester hydrolases conform to a common structural organization: the α/β-hydrolase fold, which is also present in many other hydrolytic enzymes like proteases, dehalogenases, peroxidases, and epoxide hydrolases (Ollis et al. 1992). The canonical α/β-hydrolase fold consists of an eight-stranded mostly parallel β-sheet, with the second strand anti-parallel (Fig. 3). The parallel strands, β3 to β8 are connected by helices, which pack on either side of the central β-sheet. The sheet is highly twisted and bent so that it forms a half-barrel. The active site contains the catalytic triad usually consisting of the residues serine, aspartate, and histidine (Heikinheimo et al. 1999; Jaeger et al. 1999; Nardini and Dijkstra 1999). The substrate-binding site is located inside a pocket on top of the central β-sheet that is typical of this fold. The size and shape of the substrate-binding cleft have been related to substrate specificity (Pleiss et al. 1998).

Fig. 3.

Canonical fold of α/β-hydrolases. a Topology diagram, with the strands indicated by red arrows and the helices by cyan cylinders. The positions of the catalytic residues are indicated. b–d The structures of three hyperthermophilic esterases: b the carboxylesterase AFEST from A. fulgidus (pdb 1JJI), c the esterase EstA from T. maritima (pdb 3DOH), and d the acylpeptide hydrolase apAPH from A. pernix (pdb 1VE6)

The 3D structures of several hyperthermophilic esterases have been solved (Table 3) (Fig. 3). The first reported structure of an hyperthermostable esterase was for the esterase AFEST of A. fulgidus (PDB: 1JJI) (De Simone et al. 2001). AFEST is an esterase that belongs to the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) group of esterases and lipases. The structure was refined to 2.2 Å resolution and showed that AFEST has the typical α/β-hydrolase fold. The active site is shielded by a cap region composed of five α-helices. Access to the active site of many lipases and some esterases is shielded by a mobile lid, whose position (closed or open) determines whether the enzyme is in an inactive or active conformation. AFEST is an esterase that prefers pNP-C6 as a substrate and shows maximal activity at 80°C. It is stable at high temperatures with a half-life of 1 h at 85°C (Manco et al. 2000b). A comparison of the AFEST structure with its mesophilic and thermophilic homologs, Brefeldin A from Bacillus substilus (BFAE) (PDB: 1JKM) (Wei et al. 1999) and EST2 from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius (PDB: 1EVQ) (De Simone et al. 2000), showed which structural features contribute to its thermal stability. The comparison revealed an increase in the number of intramolecular ion pairs, and a reduction in loop extensions and ratio of hydrophobic to charged surface residues (De Simone et al. 2001; Mandrich et al. 2004).

The structure of the esterase EstE1 was solved to 2.1 Å resolution (PDB: 2C7B) (Byun et al. 2007). This enzyme, which was isolated from a metagenomic library, also belongs to the HSL group and is closely related with AFEST. EstE1 has the canonical architecture of the α/β-hydrolase fold and also contains a cap domain like other members of the HSL group (De Simone et al. 2001). It exhibits highest esterase activity on short acyl chain esters of length C6 and has a half-life of 20 min at 90°C (Rhee et al. 2005). The thermal stability of EstE1 seems to be achieved mainly by its dimerization through hydrophobic interactions and ion-pair networks that both contribute to the stabilization of EstE1 (Rhee et al. 2006). This strategy for thermostabilization is different from AFEST and shows that there are a variety of structural possibilities to acquire stability.

The crystal structure of an acylpeptide hydrolase (apAPH) from the archaeon A. pernix was solved to 2.1 Å resolution (PDB: 1EV6) (Bartlam et al. 2004). Acylpeptide hydrolases are enzymes that catalyze the removal of an N-acetylated amino acid from blocked peptides. The enzyme shows an optimal temperature at 90°C for enzyme activity and is very stable at this temperature with a half-life of over 160 h. It is active on a wide range of substrates, including p-nitroanilide (pNA) amino acids, peptides, and also pNP-esters with varying acyl-chain lengths with an optimum for pNP-C6 (Gao et al. 2003). The structure of the acylpeptide hydrolase/esterase apAPH belongs to the prolyl oligopeptidase family (Bartlam et al. 2004). The structure is comprised of two domains, the N-terminal domain is a regular seven-bladed β-propeller and the C-terminal domain has the canonical α/β-hydrolase fold that contains the catalytic triad consisting of a serine, aspartate, and histidine. It was shown that a single mutation (R526E), completely abolished the peptidase activity on Ac-Leu-p-nitroanilide of this enzyme while esterase activity on pNP-C8 was only halved (Wang et al. 2006). Any mutation at the 526 site resulted in decreased peptidase activity due to loss of the ability of R526 to bind the peptidase substrate, while most of the mutants had increased esterase activity due to a more hydrophobic environment of the active site. This result shows that the enzymes can evolve such that they discriminate between substrates only by a single mutation.

The most recently elucidated structure belongs to an esterase, EstA, from T. maritima (PDB: 3DOH) (Levisson et al. 2009). The enzyme displayed optimal activity with short acyl chain esters at temperatures equal or higher than 95°C. Its structure was solved to 2.6 Å resolution and revealed a classical α/β-hydrolase domain, which contained the typical catalytic triad. Surprisingly, the structure also revealed the presence of an N-terminal immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domain. The combination of these two domains is unprecedented among both mesophilic and hyperthermophilic esterases. The function of this Ig-like domain was investigated and it was shown that it plays an important role in multimer formation, and in the stability and activity of EstA.

A high-resolution structure of an enzyme leads to a better understanding of its reaction mechanism, how it interacts with other proteins, what contributes to its stability, and may provide a basis for enzyme optimization and drug design. Because it is nowadays relatively easy to setup crystallization trials using commercially available screens and also because the current high-throughput crystallization projects are responsible for a large increase in the number of solved structures (Fox et al. 2008), it is expected that more structures of hyperthermophilic esterases will become available in future.

Classification

Enzymes can be classified on basis of their substrate preference, sequence homology, and structural similarity. Classification of enzymes based on sequence alignments provides an indication of the evolutionary relationship between enzymes. Still, structural similarity is preserved much longer than sequence similarity during evolution. On the other hand, sequence homology and structural similarity are not always correlated with the substrate preference of an enzyme. Altogether, classification of enzymes is not straightforward.

Several classifications of esterases and lipases into distinct families have been completed. In one such study, 53 bacterial esterases and lipases were classified into eight families based on their sequence similarity and some of their fundamental biological properties (Arpigny and Jaeger 1999). Many new esterases and lipases have since then been identified, including several, such as EstD from T. maritima (Levisson et al. 2007), which could not be grouped into one of these eight families. Therefore, new families for these enzymes have been proposed. However, this early classification has provided a good basis for more refined classification of the esterases and lipases. Most of the recent studies are based on sequence and structural similarity, and are accessible at online databases. Some relevant databases will be briefly discussed: The Lipase Engineering Database (LED), the Microbial Esterase and Lipase Database (MELDB), the Carbohydrate Active Enzyme (CAZy) database, and the ESTHER database.

The LED (http://www.led.uni-stuttgart.de) combines information on sequence, structure and function of esterases, lipases and related proteins sharing the same α/β-hydrolase fold (Pleiss et al. 2000; Fischer and Pleiss 2003). The database contains more than 800 prokaryotic and eukaryotic sequences, which have been grouped into families based on multi-sequence alignments. The functionally relevant residues of each family have been annotated. The database was developed as a tool for protein engineering. The LED will be updated in the forthcoming year (personal communication with Prof. Dr. Juergen Pleiss). The classification will not change, but the number of proteins and families will increase substantially. MELDB (http://www.gem.re.kr/meldb) is a database that contains more than 800 microbial esterases and lipases (Kang et al. 2006). The sequences in MELDB have been clustered into groups according to their sequence similarities, and are divided into true esterase and lipase clusters. The database was developed in order to identify, conserved but yet unknown, functional domains/motifs and relate these patterns to the biochemical properties of the enzymes. According to the authors, new enzymes of other completely sequenced microbial strains will be added on a regular basis. CAZy (http://www.cazy.org) is a database that contains enzymes involved in the degradation, modification, or creation of glycosidic bonds (Cantarel et al. 2009). One class of activities in this database is the carbohydrate esterases (CE). These enzymes remove ester-based modifications from carbohydrates. Carbohydrate esterases have been clustered into 15 families. These families have been created based on experimentally characterized proteins and sequence similarity. The database is continuously updated based on the available literature and structural information. The ESTHER database (http://bioweb.ensam.inra.fr/esther) contains more than 3500 sequences of enzymes belonging to the α/β-hydrolase fold (Hotelier et al. 2004). These enzymes have been clustered into families based on sequence alignments. This database is updated regularly, and furthermore contains information about the biochemical, pharmacological, and structural properties of the enzymes.

Novel developments and future perspectives

In recent years, many new hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea have been isolated. The genomes of several of these hyperthermophiles have been sequenced and in future this number will increase rapidly due to forthcoming sequencing projects [GOLD genomes online; (Liolios et al. 2008)]. This increase in sequence information will accelerate the identification of new carboxylic ester hydrolases with new properties. Hitherto, traditional screening has been used to identify new enzymes, however, bioinformatics and metagenome screening will contribute more and more to this identification process. A major drawback of metagenome screening is that in order to function well, the genes of interest need to be functionally expressed in the heterologous screening host. Therefore, recently a new two-host fosmid system for functional screening of (meta)genomic libraries from extreme thermophiles was developed (Angelov et al. 2009). This system allows the construction of large-insert fosmid libraries in E. coli and transfer of the recombinant libraries to extreme thermophile T. thermophilus. This system was proven to have a higher level of functionally expressed genes and may be of value in the identification of new carboxylic ester hydrolases from hyperthermophiles. However, in addition to the identification of new carboxylic ester hydrolases, also their characterization is indispensable.

The classification of esterases into families is an ongoing process and many of the current databases are incomplete. A promising approach is the superfamily-based approach, which combines theoretical and experimental data, and can reveal more information about a protein family (Folkertsma et al. 2004). A new completely automatic program capable of constructing these superfamily systems is 3DM (Joosten et al. 2008). This program is able to create a new superfamily of the carboxylic ester hydrolases based on structural and sequence similarity. In addition, superfamily systems generated by 3DM have also been proven to be powerful tools for the understanding and predicting rational modification of proteins (Leferink et al. 2009).

Many new protein structures are becoming available. These structures will provide a basis for modern methods of enzyme engineering, such as directed evolution and rational design, to broaden the applicability of these enzymes. In the past, these methods have been proven to enhance enzymes to meet specific demands, including increased stability, activity, and enantioselectivity (Dalby 2007). In future, the identification of new esterases and the possible methods to engineer them provide tools to find thermostable esterases that are able to perform a vast array of reactions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Almeida RV, Alquéres SMC, Larentis AL, Rössle SC, Cardoso AM, Almeida WI, Bisch PM, Alves TLM, Martins OB (2006) Cloning, expression, partial characterization and structural modeling of a novel esterase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Enzyme Microbial Technol 39:1128–1136

- Almeida RV, Branco RV, Peixoto B, CdS Lima, Alqueres SMC, Martins OB, Antunes OAC, Freire DMG (2008) Immobilization of a recombinant thermostable esterase (Pf2001) from Pyrococcus furiosus on microporous polypropylene: isotherms, hyperactivation and purification. Biochem Eng J 39:531–537

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Angelov A, Mientus M, Liebl S, Liebl W (2009) A two-host fosmid system for functional screening of (meta)genomic libraries from extreme thermophiles. Syst Appl Microbiol [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arpigny JL, Jaeger KE (1999) Bacterial lipolytic enzymes: classification and properties. Biochem J 343(Pt 1):177–183 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Arpigny JL, Jendrossek D, Jaeger KE (1998) A novel heat-stable lipolytic enzyme from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius DSM 639 displaying similarity to polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerases. FEMS Microbiol Lett 167:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Atomi H (2005) Recent progress towards the application of hyperthermophiles and their enzymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol 9:166–173 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Atomi H, Imanaka T (2004) Thermostable carboxylesterases from hyperthermophiles. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 15:2729–2735

- Atomi H, Matsumi R, Imanaka T (2004) Reverse gyrase is not a prerequisite for hyperthermophilic life. J Bacteriol 186:4829–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bartlam M, Wang G, Yang H, Gao R, Zhao X, Xie G, Cao S, Feng Y, Rao Z (2004) Crystal structure of an acylpeptide hydrolase/esterase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. Structure 12:1481–1488 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bornscheuer UT (2002) Microbial carboxyl esterases: classification, properties and application in biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Byun JS, Rhee JK, Kim DU, Oh JW, Cho HS (2006) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of EstE1, a new and thermostable esterase cloned from a metagenomic library. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 62:145–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Byun JS, Rhee JK, Kim ND, Yoon J, Kim DU, Koh E, Oh JW, Cho HS (2007) Crystal structure of hyperthermophilic esterase EstE1 and the relationship between its dimerization and thermostability properties. BMC Struct Biol 7:47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chahinian H, Nini L, Boitard E, Dubes JP, Comeau LC, Sarda L (2002) Distinction between esterases and lipases: a kinetic study with vinyl esters and TAG. Lipids 37:653–662 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chandrayan SK, Dhaunta N, Guptasarma P (2008) Expression, purification, refolding and characterization of a putative lysophospholipase from Pyrococcus furiosus: retention of structure and lipase/esterase activity in the presence of water-miscible organic solvents at high temperatures. Protein Expr Purif 59:327–333 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choo DW, Kurihara T, Suzuki T, Soda K, Esaki N (1998) A cold-adapted lipase of an Alaskan psychrotroph, Pseudomonas sp. strain B11–1: gene cloning and enzyme purification and characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:486–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chung Y, Park C, Lee S (2000) Partial purification and characterization of thermostable esterase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng 5:53–56

- Cornec L (1998) Thermostable esterases screened on hyperthermophilic archaeal and bacterial strains isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vents: characterization of esterase activity of a hyperthermophilic archaeum, Pyrococcus abyssi. J Marine Biotechnol 6:104–110

- D’Auria S, Herman P, Lakowicz JR, Bertoli E, Tanfani F, Rossi M, Manco G (2000) The thermophilic esterase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus: structure and conformational dynamics at high temperature. Proteins 38:351–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dalby PA (2007) Engineering enzymes for biocatalysis. Recent Pat Biotechnol 1:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Simone G, Galdiero S, Manco G, Lang D, Rossi M, Pedone C (2000) A snapshot of a transition state analogue of a novel thermophilic esterase belonging to the subfamily of mammalian hormone-sensitive lipase. J Mol Biol 303:761–771 [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Simone G, Menchise V, Manco G, Mandrich L, Sorrentino N, Lang D, Rossi M, Pedone C (2001) The crystal structure of a hyper-thermophilic carboxylesterase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J Mol Biol 314:507–518 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio P, Graziano G, Granata V, Barone G, Mandrich L, Rossi M, Manco G (2002) Denaturing action of urea and guanidine hydrochloride towards two thermophilic esterases. Biochem J 367:857–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio P, Graziano G, Granata V, Barone G, Mandrich L, Rossi M, Manco G (2003) Effect of trifluoroethanol on the conformational stability of a hyperthermophilic esterase: a CD study. Biophys Chem 104:407–415 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio P, Elias M, Merone L, Graziano G, Dupuy J, Mandrich L, Carullo P, Fournier B, Rochu D, Rossi M et al (2009) Structural determinants of the high thermal stability of SsoPox from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles 13(3):461–470 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dominguez A, Sanroman A, Fucinos P, Rua ML, Pastrana L, Longo MA (2004) Quantification of intra- and extra-cellular thermophilic lipase/esterase production by Thermus sp. Biotechnol Lett 26:705–708 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dominguez A, Pastrana L, Longo MA, Rúa ML, Sanroman MA (2005) Lipolytic enzyme production by Thermus thermophilus HB27 in a stirred tank bioreactor. Biochem Eng J 26:95–99

- Domínguez A, Fucinos P, Rúa ML, Pastrana L, Longo MA, Sanromán MA (2007) Stimulation of novel thermostable extracellular lipolytic enzyme in cultures of Thermus sp. Enzyme Microbial Technol 40:187–194

- Egorova K, Antranikian G (2005) Industrial relevance of thermophilic Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:649–655 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ejima K, Liu J, Oshima Y, Hirooka K, Shimanuki S, Yokota Y, Hemmi H, Nakayama T, Nishino T (2004) Molecular cloning and characterization of a thermostable carboxylesterase from an archaeon, Sulfolobus shibatae DSM5389: non-linear kinetic behavior of a hormone-sensitive lipase family enzyme. J Biosci Bioeng 98:445–451 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Elias M, Dupuy J, Merone L, Lecomte C, Rossi M, Masson P, Manco G, Chabriere E (2007) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the hyperthermophilic Sulfolobus solfataricus phosphotriesterase. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 63:553–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elias M, Dupuy J, Merone L, Mandrich L, Porzio E, Moniot S, Rochu D, Lecomte C, Rossi M, Masson P et al (2008) Structural basis for natural lactonase and promiscuous phosphotriesterase activities. J Mol Biol 379:1017–1028 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fischer M, Pleiss J (2003) The Lipase Engineering Database: a navigation and analysis tool for protein families. Nucleic Acids Res 31:319–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Folkertsma S, van Noort P, Van Durme J, Joosten HJ, Bettler E, Fleuren W, Oliveira L, Horn F, de Vlieg J, Vriend G (2004) A family-based approach reveals the function of residues in the nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain. J Mol Biol 341:321–335 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fox BG, Goulding C, Malkowski MG, Stewart L, Deacon A (2008) Structural genomics: from genes to structures with valuable materials and many questions in between. Nat Methods 5:129–132 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fucinos P, Abadín CM, Sanromán A, Longo MA, Pastrana L, Rúa ML (2005a) Identification of extracellular lipases/esterases produced by Thermus thermophilus HB27: partial purification and preliminary biochemical characterisation. J Biotechnol 117:233–241 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fucinos P, Dominguez A, Sanroman MA, Longo MA, Rua ML, Pastrana L (2005b) Production of thermostable lipolytic activity by Thermus species. Biotechnol Prog 21:1198–1205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fucinos P, Rúa ML, Longo MA, Sanromán M, Pastrana L (2008) Thermal spring water enhances lipolytic activity in Thermus thermophilus HB27. Process Biochem 43:1383–1390

- Gao R, Feng Y, Ishikawa K, Ishida H, Ando S, Kosugi Y, Cao S (2003) Cloning, purification and properties of a hyperthermophilic esterase from archaeon Aeropyrum pernix K1. J Mol Catal B Enzym 24:1–8

- Gao R-j, Xie G-q, Zhou J, Feng Y, Cao S-g (2006) Denaturing effects of urea and guanidine hydrochloride on hyperthermophilic esterase from Aeropyrum pernix K1. Chem Res Chin Univ 22:168–172

- Gomes J, Steiner W (2004) The biocatalytic potential of extremophiles and extremozymes. Food Technol Biotechnol 42:223–235

- Gupta R, Gupta N, Rathi P (2004) Bacterial lipases: an overview of production, purification and biochemical properties. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64:763–781 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hasan F, Shah AA, Hameed A (2006) Industrial applications of microbial lipases. Enzyme Microbial Technol 39:235–251

- Heikinheimo P, Goldman A, Jeffries C, Ollis DL (1999) Of barn owls and bankers: a lush variety of alpha/beta hydrolases. Structure 7:R141–R146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hess M, Katzer M, Antranikian G (2008) Extremely thermostable esterases from the thermoacidophilic euryarchaeon Picrophilus torridus. Extremophiles 12:351–364 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hotelier T, Renault L, Cousin X, Negre V, Marchot P, Chatonnet A (2004) ESTHER, the database of the alpha/beta-hydrolase fold superfamily of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D145–D147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hotta Y, Ezaki S, Atomi H, Imanaka T (2002) Extremely stable and versatile carboxylesterase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:3925–3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huddleston S, Yallop CA, Charalambous BM (1995) The identification and partial characterisation of a novel inducible extracellular thermostable esterase from the archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 216:495–500 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hunter S, Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Binns D, Bork P, Das U, Daugherty L, Duquenne L et al (2009) InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D211–D215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ikeda M, Clark DS (1998) Molecular cloning of extremely thermostable esterase gene from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 57:624–629 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jaeger KE, Eggert T (2002) Lipases for biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13:390–397 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jaeger KE, Dijkstra BW, Reetz MT (1999) Bacterial biocatalysts: molecular biology, three-dimensional structures, and biotechnological applications of lipases. Annu Rev Microbiol 53:315–351 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Joosten HJ, Han Y, Niu W, Vervoort J, Dunaway-Mariano D, Schaap PJ (2008) Identification of fungal oxaloacetate hydrolyase within the isocitrate lyase/PEP mutase enzyme superfamily using a sequence marker-based method. Proteins 70:157–166 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kakugawa S, Fushinobu S, Wakagi T, Shoun H (2007) Characterization of a thermostable carboxylesterase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 74:585–591 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kang HY, Kim JF, Kim MH, Park SH, Oh TK, Hur CG (2006) MELDB: a database for microbial esterases and lipases. FEBS Lett 580:2736–2740 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim S, Lee SB (2004) Thermostable esterase from a thermoacidophilic archaeon: purification and characterization for enzymatic resolution of a chiral compound. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:2289–2298 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim SB, Lee W, Ryu YW (2008) Cloning and characterization of thermostable esterase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J Microbiol 46:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krishna SH, Karanth NG (2002) Lipases and lipase-catalyzed esterification reactions in nonaqueous media. Catal Rev 44:499–591

- Kwoun Kim H, Jung YJ, Choi WC, Ryu HS, Oh TK, Lee JK (2004) Sequence-based approach to finding functional lipases from microbial genome databases. FEMS Microbiol Lett 235:349–355 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee EG, Won HS, Chung BH (2001) Enantioselective hydrolysis of racemic naproxen methyl ester by two-step acetone-treated Candida rugosa lipase. Process Biochem 37:293–298

- Leferink NG, Fraaije MW, Joosten HJ, Schaap PJ, Mattevi A, van Berkel WJ (2009) Identification of a gatekeeper residue that prevents dehydrogenases from acting as oxidases. J Biol Chem 284:4392–4397 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Levisson M, van der Oost J, Kengen SW (2007) Characterization and structural modeling of a new type of thermostable esterase from Thermotoga maritima. FEBS J 274:2832–2842 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Levisson M, Sun L, Hendriks S, Swinkels P, Akveld T, Bultema JB, Barendregt A, van den Heuvel RH, Dijkstra BW, van der Oost J et al (2009) Crystal structure and biochemical properties of a novel thermostable esterase containing an immunoglobulin-like domain. J Mol Biol 385:949–962 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liolios K, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC (2008) The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2007: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D475–D479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lorenz P, Eck J (2005) Metagenomics and industrial applications. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:510–516 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manco G, Camardella L, Febbraio F, Adamo G, Carratore V, Rossi M (2000a) Homology modeling and identification of serine 160 as nucleophile of the active site in a thermostable carboxylesterase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Protein Eng 13:197–200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manco G, Giosue E, D’Auria S, Herman P, Carrea G, Rossi M (2000b) Cloning, overexpression, and properties of a new thermophilic and thermostable esterase with sequence similarity to hormone-sensitive lipase subfamily from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Arch Biochem Biophys 373:182–192 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manco G, Carrea G, Giosuè E, Ottolina G, Adamo G, Rossi M (2002) Modification of the enantioselectivity of two homologous thermophilic carboxylesterases from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius and Archaeoglobus fulgidus by random mutagenesis and screening. Extremophiles 6:325–331 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mandrich L, Pezzullo M, Del Vecchio P, Barone G, Rossi M, Manco G (2004) Analysis of thermal adaptation in the HSL enzyme family. J Mol Biol 335:357–369 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mandrich L, Merone L, Pezzullo M, Cipolla L, Nicotra F, Rossi M, Manco G (2005) Role of the N terminus in enzyme activity, stability and specificity in thermophilic esterases belonging to the HSL family. J Mol Biol 345:501–512 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mandrich L, Pezzullo M, Rossi M, Manco G (2007) SSoNDelta and SSoNDeltalong: two thermostable esterases from the same ORF in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus? Archaea 2:109–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M et al (2009) CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D205–D210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Merone L, Mandrich L, Rossi M, Manco G (2005) A thermostable phosphotriesterase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: cloning, overexpression and properties. Extremophiles 9:297–305 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morana A, Di Prizito N, Aurilia V, Rossi M, Cannio R (2002) A carboxylesterase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus: cloning of the gene, characterization of the protein. Gene 283:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murayama K, Shirouzu M, Terada T, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S (2005) Crystal structure of TT1662 from Thermus thermophilus HB8: a member of the alpha/beta hydrolase fold enzymes. Proteins 58:982–984 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nardini M, Dijkstra BW (1999) Alpha/beta hydrolase fold enzymes: the family keeps growing. Curr Opin Struct Biol 9:732–737 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ollis DL, Cheah E, Cygler M, Dijkstra B, Frolow F, Franken SM, Harel M, Remington SJ, Silman I, Schrag J et al (1992) The alpha/beta hydrolase fold. Protein Eng 5:197–211 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Panda T, Gowrishankar BS (2005) Production and applications of esterases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 67:160–169 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park YJ, Choi SY, Lee HB (2006) A carboxylesterase from the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P1; purification, characterization, and expression. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Prots Proteomics 1760:820–828 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park YJ, Yoon SJ, Lee HB (2008) A novel thermostable arylesterase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P1: purification, characterization, and expression. J Bacteriol 190:8086–8095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pleiss J, Fischer M, Schmid RD (1998) Anatomy of lipase binding sites: the scissile fatty acid binding site. Chem Phys Lipids 93:67–80 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pleiss J, Fischer M, Peiker M, Thiele C, Schmid RD (2000) Lipase engineering database: understanding and exploiting sequence-structure-function relationships. J Mol Catal B Enzym 10:491–508

- Porzio E, Merone L, Mandrich L, Rossi M, Manco G (2007) A new phosphotriesterase from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius and its comparison with the homologue from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biochimie 89:625–636 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Quax WJ, Broekhuizen CP (1994) Development of a new Bacillus carboxyl esterase for use in the resolution of chiral drugs. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 41:425–431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rathi P, Bradoo S, Saxena RK, Gupta R (2000) A hyper-thermostable, alkaline lipase from Pseudomonas sp with the property of thermal activation. Biotechnol Lett 22:495–498

- Rhee JK, Ahn DG, Kim YG, Oh JW (2005) New thermophilic and thermostable esterase with sequence similarity to the hormone-sensitive lipase family, cloned from a metagenomic library. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:817–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rhee JK, Kim DY, Ahn DG, Yun JH, Jang SH, Shin HC, Cho HS, Pan JG, Oh JW (2006) Analysis of the thermostability determinants of hyperthermophilic esterase EstE1 based on its predicted three-dimensional structure. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3021–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ro HS, Hong HP, Kho BH, Kim S, Chung BH (2004) Genome-wide cloning and characterization of microbial esterases. FEMS Microbiol Lett 233:97–105 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Rechavi M, Alibes A, Godzik A (2006) Contribution of electrostatic interactions, compactness and quaternary structure to protein thermostability: lessons from structural genomics of Thermotoga maritima. J Mol Biol 356:547–557 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rozzell JD (1999) Commercial scale biocatalysis: myths and realities. Bioorg Med Chem 7:2253–2261 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rusnak M, Nieveler J, Schmid RD, Petri R (2005) The putative lipase, AF1763, from Archaeoglobus fulgidusis is a carboxylesterase with a very high pH optimum. Biotechnol Lett 27:743–748 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Salameh M, Wiegel J (2007a) Lipases from extremophiles and potential for industrial applications. Adv Appl Microbiol 61:253–283 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Salameh MA, Wiegel J (2007b) Purification and characterization of two highly thermophilic alkaline lipases from Thermosyntropha lipolytica. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:7725–7731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Santos H, da Costa MS (2002) Compatible solutes of organisms that live in hot saline environments. Environ Microbiol 4:501–509 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sehgal AC, Kelly RM (2002) Enantiomeric resolution of 2-aryl propionic esters with hyperthermophilic and mesophilic esterases: contrasting thermodynamic mechanisms. J Am Chem Soc 124:8190–8191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sehgal AC, Kelly RM (2003) Strategic selection of hyperthermophilic esterases for resolution of 2-arylpropionic esters. Biotechnol Prog 19:1410–1416 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sehgal AC, Callen W, Mathur EJ, Short JM, Kelly RM (2001) Carboxylesterase from Sulfolobus solfataricus P1. Methods Enzymol 330:461–471 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sehgal AC, Tompson R, Cavanagh J, Kelly RM (2002) Structural and catalytic response to temperature and cosolvents of carboxylesterase EST1 from the extremely thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P1. Biotechnol Bioeng 80:784–793 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shimada Y, Koga C, Sugihara A, Nagao T, Takada N, Tsunasawa S, Tominaga Y (1993) Purification and characterization of a novel solvent-tolerant lipase from Fusarium heterosporum. J Fermentation Bioeng 75:349–352

- Sobek H, Gorisch H (1988) Purification and characterization of a heat-stable esterase from the thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Biochem J 250:453–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sobek H, Gorisch H (1989) Further kinetic and molecular characterization of an extremely heat-stable carboxylesterase from the thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Biochem J 261:993–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stetter KO (1996) Hyperthermophilic procaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 18:149–158

- Stetter KO (2006) Hyperthermophiles in the history of life. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361:1837–1842 discussion 1842-1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stocklein W, Sztajer H, Menge U, Schmid RD (1993) Purification and properties of a lipase from Penicillium expansum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1168:181–189 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Suen WC, Zhang N, Xiao L, Madison V, Zaks A (2004) Improved activity and thermostability of Candida antarctica lipase B by DNA family shuffling. Protein Eng Des Sel 17:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun L, Levisson M, Hendriks S, Akveld T, Kengen SW, Dijkstra BW, van der Oost J (2007) Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of an esterase with a novel domain from the hyperthermophile Thermotoga maritima. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 63:777–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Suzuki Y, Miyamoto K, Ohta H (2004) A novel thermostable esterase from the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. FEMS Microbiol Lett 236:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tirawongsaroj P, Sriprang R, Harnpicharnchai P, Thongaram T, Champreda V, Tanapongpipat S, Pootanakit K, Eurwilaichitr L (2008) Novel thermophilic and thermostable lipolytic enzymes from a Thailand hot spring metagenomic library. J Biotechnol 133:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Unsworth LD, van der Oost J, Koutsopoulos S (2007) Hyperthermophilic enzymes—stability, activity and implementation strategies for high temperature applications. FEBS J 274:4044–4056 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vieille C, Zeikus GJ (2001) Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 65:1–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Lu D, Gao R, Yang Z, Cao S, Feng Y (2004) A novel phospholipase A2/esterase from hyperthermophilic archaeon Aeropyrum pernix K1. Protein Expr Purif 35:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Yang G, Liu Y, Feng Y (2006) Discrimination of esterase and peptidase activities of acylaminoacyl peptidase from hyperthermophilic Aeropyrum pernix K1 by a single mutation. J Biol Chem 281:18618–18625 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wei Y, Contreras JA, Sheffield P, Osterlund T, Derewenda U, Kneusel RE, Matern U, Holm C, Derewenda ZS (1999) Crystal structure of brefeldin A esterase, a bacterial homolog of the mammalian hormone-sensitive lipase. Nat Struct Biol 6:340–345 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang G, Bai A, Gao L, Zhang Z, Zheng B, Feng Y (2009) Glu88 in the non-catalytic domain of acylpeptide hydrolase plays dual roles: charge neutralization for enzymatic activity and formation of salt bridge for thermodynamic stability. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:94–102 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Liu J, Zhou J, Ren Y, Dai X, Xiang H (2003) Thermostable esterase from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis: high-level expression, purification and characterization. Biotechnol Lett 25:1463–1467 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang G, Gao R, Zheng L, Zhang A, Wang Y, Wang Q, Feng Y, Cao S (2006) Study on the relationship between structure and enantioselectivity of a hyperthermophilic esterase from archaeon Aeropyrum pernix K1. J Mol Catal B Enzym 38:148–153

- Zhang G-r, Gao R-j, Zhang A-j, Rao L, Cao S-g (2007) High-throughput screening of the enantioselectivity of hyperthermophilic mutant esterases from archaeon Aeropyrum pernix K1 for Resolution of (R,S)-2-octanol acetate. Chem Res Chin Univ 23:319–324

- Zhang Z, Zheng B, Wang Y, Chen Y, Manco G, Feng Y (2008) The conserved N-terminal helix of acylpeptide hydrolase from archaeon Aeropyrum pernix K1 is important for its hyperthermophilic activity. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Prots Proteomics 1784:1176–1183 [DOI] [PubMed]