Abstract

BACKGROUND:

A possible breach of the transducer protector in specific dialysis machines was reported in June 2004 in British Columbia (BC), which led to testing of hemodialysis patients for hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HIV. This testing provided an opportunity to examine HCV incidence, prevalence and coinfection with HBV and HIV, and to compare anti-HCV and HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

METHODS:

The results of hemodialysis patients who were dialyzed on the implicated machines (65% of BC dialysis patients), and tested for HCV, HBV and HIV, between June 1, 2004, and December 31, 2004, were reviewed and compared with available previous results.

RESULTS:

Of 1286 hemodialysis patients with anti-HCV and/or HCV-PCR testing, 69 (5.4%) tested positive. Two HCV genotype 4 seroconversions were identified. HCV incidence rate on dialysis was 78.8 cases per 100,000 person-years. Younger age, history of renal transplant and past HBV infection were associated with HCV infection. No occult infection was identified using HCV-PCR.

INTERPRETATION:

Hemodialysis patients had three times the HCV prevalence rate of the general BC population, and more than 20 times the incident rate of the general Canadian population. One of the two seroconversions occurred before the testing campaign; the patient was likely infected during hemodialysis in South Asia. The other was plausibly a late seroconversion following renal transplant in South Asia. Nosocomial transmission cannot be ruled out because both patients were dialyzed in the same centre. Baseline and annual anti-HCV testing is recommended. HCV-PCR should be considered at baseline for persons with HCV risk factors, and for returning travellers who received dialysis in HCV-endemic countries to identify HCV infection occurring outside the hemodialysis unit.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Hepatitis C, HCV, Incidence, Prevalence

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

On a signalé un bris possible du protecteur du transducteur de certains appareils à dialyse en juin 2004, en Colombie-Britannique (C.-B.), ce qui a forcé la réalisation de tests de dépistage du virus de l’hépatite C (VHC), du virus de l’hépatite B (VHB) et du VIH chez les patients hémodialysés. Ces tests ont permis de mesurer l’incidence et la prévalence du VHC, du VHB, du VIH et des co-infections, et de comparer les résultats du dépistage des anticorps anti-VHC et de la recherche du VHC par RCP (réaction en chaîne de la polymérase).

MÉTHODES :

Selon le cas, les auteurs ont passé en revue et comparé avec des résultats antérieurs les résultats des patients hémodialysés au moyen des appareils en cause (65 % des patients dialysés en C.-B.) qui ont subi des tests de dépistage du VHC, du VHB et du VIH entre le 1er juin et le 31 décembre 2004.

RÉSULTATS :

Parmi les 1 286 patients hémodialysés ayant subi des tests de dépistage des anticorps anti-VHC et/ou du VHC par RCP, 69 (5,4 %) ont obtenu des résultats positifs. Deux séroconversions au génotype 4 du VHC ont été recensées. Le taux d’incidence du VHC sous dialyse a été de 78,8 cas par 100 000 années-personnes. Un lien a été établi entre un âge moins avancé, des antécédents de transplantation rénale et d’infection au VHB et l’infection au VHC. Aucune infection occulte n’a été relevée par la recherche du VHC au moyen de la RCP.

INTERPRÉTATION :

Les patients sous hémodialyse ont présenté un taux de prévalence du VHC trois fois plus élevé que dans la population générale de la Colombie-Britannique et 20 fois plus élevé que dans celle du Canada. L’une des deux séroconversions est survenue avant la campagne de dépistage. Ce patient a probablement contracté son infection lors d’une hémodialyse subie pendant un séjour en Asie du Sud. L’autre s’explique probablement par une séroconversion tardive suivant une greffe rénale également subie en Asie du Sud. La transmission nosocomiale ne peut être écartée parce que les deux patients étaient dialysés au même centre hospitalier. On recommande un dosage des anticorps anti-VHC au départ et annuellement. Il faut envisager le dépistage du VHC par RCP au départ chez les personnes exposées à des facteurs de risque à l’égard de ce virus et chez les sujets qui reviennent de l’étranger après avoir reçu des traitements de dialyse dans des pays où sévit le VHC, afin de diagnostiquer l’infection au VHC contractée à l’extérieur de l’unité de dialyse.

Prolonged vascular exposure puts hemodialysis patients at increased risk of infection by blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV, from contaminated devices, equipment and supplies, environmental surfaces or attending personnel (1). Several studies (2–4) have reported nosocomial transmission of HCV in hemodialysis units by breaches in infection control practice and/or contamination of dialysis machines.

HCV infection has approximately 75% probability of becoming a chronic infection (5). Chronic HCV infection causes progressive liver disease leading to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease or liver cancer in 15% to 25% of patients (6,7). A reactive antibody to HCV (anti-HCV) test indicates a present or past infection, whereas a reactive HCV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test determines an active infection by detecting the presence of HCV-RNA in the blood. Chronic HBV infection is less common than HCV in hemodialysis units (8–11) due to routine screening, vaccination programs, infection control measures for HBV (12,13) and higher rates of viral clearance.

In June 2004, hemodialysis sites in British Columbia (BC) reported a possible breach of the transducer protector in the disposable blood tubing set of a particular brand of hemodialysis machines that may have led to cross-contamination among hemodialysis patients. This will be referred to as ‘the event’. Consequently, all patients in BC who received hemodialysis with the implicated brand of machine between December 2003 and June 2004 were encouraged to receive HCV, HBV and HIV testing.

Anti-HCV tests may not accurately reflect true HCV status due to delayed or blunted seroconversion in the immunode-pressed (14,15); a delay of up to 18 months has been reported in dialysis patients (16–18). HCV RNA is detectable in serum by PCR within two weeks of infection; it disappears if the infection resolves spontaneously and persists in chronic infections (15). Thus, HCV-PCR testing can distinguish resolved infections from active infections, as well as detect HCV RNA preseroconversion (16). Therefore, HCV-PCR testing was recommended in addition to HCV antibody testing in this population.

Subsequent testing and comparison with previous results allowed the authors the opportunity to describe HCV incidence and prevalence in the present cohort of hemodialysis patients. The objectives of the retrospective analysis were as follows:

To estimate the incidence rate of HCV infection in a hemodialysis population;

To estimate the prevalence of HCV infection and HCV coinfection with HBV and HIV in a hemodialysis population;

To describe demographic characteristics of individuals infected with HCV; and

To determine whether HCV-PCR testing identifies HCV infections not detected by anti-HCV testing.

METHODS

Study population

Data were obtained from the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) and the BC Provincial Renal Agency central database for patients who used the implicated hemodialysis machines between December 2003 and June 2004. The sample represented 65% of all hemodialysis patients in BC. The combined database included all corresponding HCV (anti-HCV and HCV-PCR), HBV (hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], anti-HBs and antibody to hepatitis B core total [anti-HBcT]) and HIV test results. Patient characteristics such as sex, date of birth, location of dialysis treatment, date of dialysis initiation and date of kidney transplant(s), if applicable, were included. An additional variable – time on dialysis up to January 1, 2005 – was created to categorize patients to one of three groups (less than two years, two to four years and five years or more) to compare with the only other Canadian study (19) that researched on the prevalence of HCV within a dialysis setting. Age on January 1, 2005, was used to classify cases for analysis.

Laboratory methodology

Samples were screened for anti-HCV by AxSYM HCV 3.0 (Abbott Diagnostics, Canada) and confirmed using the Ortho Vitros EcI (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Canada). Only samples reactive on both enzyme immunoassay tests were considered reactive. If only one assay was reactive, results were considered equivocal. HBsAg, anti-HBcT and anti-HBs were performed by AxSYM, and reactive HBsAg specimens were confirmed by neutralization. HIV status was determined by screening for anti-HIV using the AxSYM HIV-1/2 gO assay (Abbott Laboratories, Canada) and reactives confirmed by Western blot. Active HCV infection was assessed by HCV RNA detection by the qualitative Roche COBAS AMPLICOR HCV Test, version 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Canada) using a dedicated EDTA specimen obtained from a peripheral vein before hemodialysis, and the results reported as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Individuals who displayed initial equivocal serological results underwent additional follow-up and confirmatory testing to define their true clinical status. Individuals whose sole marker for HBV infection was a reactive anti-HBcT test result, and had a subsequent nonreactive anti-HBcT result were considered to be anti-HBcT nonreactive.

Statistical analysis

To calculate the incidence rate per person-years, the number of seroconverters was divided by the summed total time between the start of dialysis and the last negative test; or for those who seroconverted, the time from initiation of dialysis to the midpoint of their negative-to-positive HCV test was used. OR and corresponding 95% CIs of the different patient characteristics were calculated using univariate χ2 tests. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS Inc, USA) was used for all analyses.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia’s (Vancouver, British Columbia) Clinical Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

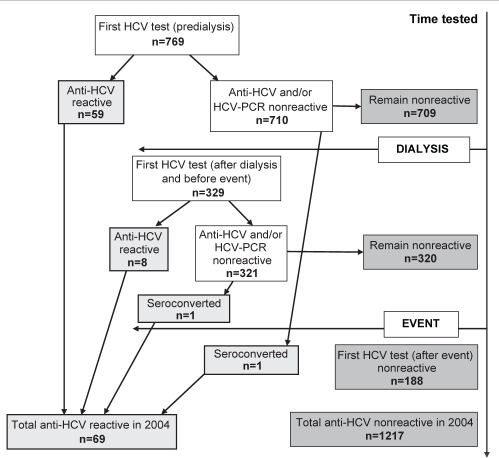

In total, 1286 patients who received hemodialysis on the implicated machines between December 2003 and June 2004 were tested for HCV (either anti-HCV or HCV-PCR) at BCCDC; 1206 patients (93.8%) were tested during the recommended testing period of June 1, 2004, to December 31, 2004 (Figure 1). Of the total, 769 (59.8%) had their first available HCV test result before commencing dialysis; 329 (25.6%) had their first HCV test result after starting dialysis but before the event and 188 (14.6%) had their first HCV test result after the event. The average time between the dialysis start date and the first HCV test for those who underwent a HCV test after starting dialysis was 1.83 years.

Figure 1).

Flow chart of hepatitis C virus (HCV) test results for 1286 patients receiving hemodialysis on the implicated brand of machines between December 2003 and June 2004. PCR Polymerase chain reaction

The mean age was 63 years and 59.4% were men (Table 1); the average length of time on dialysis was 2.76 years. One hundred forty-four patients (11.2%) had received at least one kidney transplant, and 36 (25%) of these had their first transplant before 1992 (ie, before routine HCV testing of blood and blood products). The results of the univariate analysis by HCV infection are shown in Table 1. Younger age was significantly associated with HCV status, and history of transplant was strongly but not significantly associated. Time on dialysis and geography – defined as the location of the health authority in which hemodialysis is being received – were not associated with HCV status.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies and ORs of hepatitis C virus (HCV) test results (by patient characteristics) of the cohort receiving hemodialysis on the implicated brand of machines between December 2003 and June 2004

| Total (n=1286) |

Anti-HCV and/or HCV-PCR |

OR | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n=69) | Negative (n=1217) | |||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 764 (59.4) | 48 (6.3) | 716 (93.7) | 1.00 | – | |

| Women | 522 (40.6) | 21 (4.0) | 501 (96.0) | 0.63 | 0.37–1.06 | 0.08 |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 63.1±15.8 | 52.8±11.9 | 63.7±15.8 | 0.96 | 0.95–0.98 | <0.01 |

| Health authority, n (%) | ||||||

| Interior | 123 (9.6) | 6 (4.9) | 117 (95.1) | 0.97 | 0.39–2.42 | 0.96 |

| Fraser | 520 (40.7) | 26 (5.0) | 494 (95.0) | 1.00 | ||

| Vancouver Coastal | 213 (16.7) | 10 (4.7) | 203 (95.3) | 0.94 | 0.44–1.98 | 0.86 |

| Vancouver Island | 314 (24.6) | 21 (6.7) | 293 (93.3) | 1.36 | 0.75–2.46 | 0.31 |

| Northern | 108 (8.5) | 5 (4.6) | 103 (95.4) | 0.92 | 0.35–2.46 | 0.87 |

| Time on dialysis, n (%) | ||||||

| <2 years | 578 (44.9) | 30 (5.2) | 548 (94.8) | 1.00 | – | – |

| 2–4 years | 576 (44.8) | 32 (5.6) | 544 (94.4) | 1.08 | 0.64–1.79 | 0.78 |

| ≥ 5 years | 132 (10.3) | 7 (5.3) | 125 (94.7) | 1.02 | 0.44–2.38 | 0.96 |

| Transplant, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 144 (11.2) | 13 (9.0) | 131 (91.0) | 1.92 | 1.03–3.61 | 0.04 |

| No | 1142 (88.8) | 56 (4.9) | 1086 (95.1) | 1.00 | – | – |

PCR Polymerase chain reaction

The overall prevalence of HCV infection on initial HCV testing in the present cohort was 67 of 1286 (5.2%). Based on serial retesting of this cohort, two individuals seroconverted while on dialysis (HCV incidence rate on dialysis was 78.8 cases per 100,000 person-years), and six lost antibodies to HCV. One individual had received a transfusion and dialysis in South Asia and had a documented seroconversion before the event. The other had a renal transplant in South Asia but was seronegative before the event; no previous HCV-PCR result was available to exclude late seroconversion. Both seroconverters were HCV genotype 4, which is rare in BC (less than 1%), and both received hemodialysis at the same centre. Further typing found the same banding pattern on the VERSANT HCV Genotype 2.0 Assay (LiPA) (Bayer Healthcare, Canada). All six individuals who demonstrated antibody loss, were previously anti-HCV-reactive, with subsequent negative or weakly reactive antibody tests and negative HCV-PCR tests. One had a previous positive HCV-PCR test, and one had multiple reactive anti-HCV tests before becoming seronegative.

The results of the HCV tests performed during 2004 are displayed in Table 2. HCV-PCR did not identify any new patients who tested anti-HCV negative. Of the 35 patients who tested anti-HCV positive and had an HCV-PCR test, 31 (88.6%) tested HCV-PCR positive. In total, 54 (4.4%) had a positive anti-HCV and/or HCV-PCR test during the period. Of the 58 who were not tested during this period, eight (13.8%) had previously tested anti-HCV positive.

TABLE 2.

Hepatitis C virus test performed between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2004, of the cohort receiving hemodialysis on the implicated brand of machine from December 2003 to June 2004

| Antibody |

Polymerase chain reaction |

Total | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | No test peformed | |||

| Positive | 31 | 4 | 5 | 40 | 3.3 |

| Negative | 0 | 896 | 105 | 1001 | 81.5 |

| Equivocal/weakly reactive | 0 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1.4 |

| No test performed | 14 | 156 | NA | 170 | 13.8 |

| Total, n (%) | 45 (3.7) | 1073 (87.4) | 110 (9.0) | 1228 | – |

NA Not applicable

Not all 1286 patients in our HCV-tested cohort underwent complete HBV and HIV serological testing. Of the 1199 (93.2%) who also had an HBsAg test, 24 were HBsAg reactive (Table 3). Three (4.6%) of the 65 HCV-positive patients tested were HBsAg positive; all three were HCV-PCR positive. Twenty-six of the HCV-reactive patients were found to have serology indicating previous HBV infection (anti-HBcT reactive, but HBsAg negative). Those with previous HBV infections were more than five times more likely to be infected with HCV compared with those without a history of HBV infection. Only two of the 1164 individuals were HIV reactive; neither was coinfected with HCV.

TABLE 3.

Frequencies and ORs of hepatitis C virus (HCV) test results (by hepatitis B virus and HIV test results) of the cohort receiving hemodialysis on the implicated brand of machine from December 2003 to June 2004

| Total |

Anti-HCV and/or HCV-PCR |

OR | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |||||

| HBsAg (n=1199) | n=65 | n=1134 | ||||

| positive, n (%) | 24 (2.0) | 3 (4.6) | 21 (1.9) | 2.57 | 0.75–8.83 | 0.14 |

| HBcT (n=1174) | n=67 | n=1107 | ||||

| positive, n (%) | 170 (14.7) | 29 (44.6) | 141 (12.9) | 5.45 | 3.24–9.17 | <0.01 |

| HBcT-positive and HBsAg-negative, n (%) | 149 (12.8) | 26 (40.0) | 123 (11.2) | 5.27 | 3.10–8.96 | <0.01 |

| HIV (n=1164) | n=64 | n=1100 | ||||

| positive, n (%) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | NA | NA | – |

HBcT Hepatitis B core total; HBsAg Hepatitis B surface antigen; NA Not applicable; PCR Polymerase chain reaction

DISCUSSION

Despite modern infection control policies (20,21), hepatitis transmission is still reported in hemodialysis centres (22,23). All hemodialysis units in BC follow formal infection control policies (24), which recommend anti-HCV testing before dialysis initiation and every six months thereafter. Despite these policies and the known higher HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis population, 40% were not tested for anti-HCV until after dialysis had been commenced, and 36.4% were tested only after the event occurred.

Two patients showed HCV seroconversion during the testing period – one patient seroconverted before the event and the other received a renal transplant in South Asia in the past year, but was seronegative before the testing campaign. Late seroconversion remains a plausible but unconfirmed explanation. Because both patients dialyzed in the same hemodialysis centre, nosocomial transmission cannot be ruled out. However, no other transmission of HBV, HCV or HIV was identified in any site.

The prevalence of HCV in this hemodialysis population is 5.2%, which is consistent with reports from Alberta (6.5%) (19) and other developed countries (25). This is higher than the general Canadian population prevalence of 0.8% (5,26), and the BC population prevalence of 1.5% (Dr Krajden, personal communication). HCV incidence on dialysis (78.8 per 100,000 person-years or 0.08 per 100 person-years) was more than 20 times higher than the general Canadian population incidence rate of 3.2 cases per 100,000 person-years (5), but lower than European and Japanese rates reported in hemodialysis populations (0.4 per 100 person-years to 2.59 per 100 person-years) (27–29).

We found that younger age, history of transplant and history of past HBV infection were associated with HCV infection (19,30,31). Contrary to reported literature, the time on dialysis in our study was not significantly associated with HCV infection (19,30,32–35). No data were available on transfusion history or lifestyle behaviours, including substance abuse, which are known to be risk factors for HCV infection (19,25,30,32,34,35). HIV was not prevalent in this hemodialysis population (0.2% infected), and there were no HCV patients coinfected with HIV. The proportion of patients with active HBV infection and cleared HBV infection was 2.5 and 3.7 times, respectively, higher in patients with HCV antibodies. This higher rate of HBV infection is not surprising because both viruses share similar routes of transmission, and coinfection is more common among people who have a high risk for parenteral infections (36–40).

The present study did not identify any patient with HCV-PCR who had tested anti-HCV negative, which is contrary to the findings of some studies (16,18,30,32,41). Possible reasons could include lower prevalence of immunosuppression (hence delayed antibody development), lower HCV incidence (lower probability of patient tested during serological ‘window period’) or other differences in population characteristics. The results from the present study suggest that routine testing for HCV-PCR in anti-HCV-negative hemodialysis patients in BC is unnecessary.

We found that only 8.1% of patients who were identified to be anti-HCV positive were HCV-PCR negative. This is much lower than the rate of spontaneous clearance of HCV in immunocompetent populations of 15% to 25% (5). This could in part be due to their immunocompromised status; however, it is also likely to be an underestimate because hemodialysis patients may lose their HCV antibodies, as demonstrated in the present study (8.9% had signs of antibody loss) and others (42).

There are a few limitations of the present study. First, our sample consisted of only those patients who were dialyzed on the implicated machines. However, 65% of all patients in BC are dialyzed on these machines, machine use is facility- rather than patient-specific and the machines are used in every health authority. Therefore, we consider the results to be generalizable to BC’s hemodialysis population. Second, testing for HCV, HBV and HIV, although recommended to all, was voluntary. Patients known to be previously reactive may not have been retested for that particular virus. However, if they were tested for any one of HCV, HBV or HIV, previous results for all three viruses were obtained. Third, although all HCV-PCR tests and 95% of anti-HCV tests in BC are performed at BCCDC, and any reactive anti-HCV is reportable, negative antibody tests performed at other sites may not have been forwarded. This, however, represented a small number of anti-HCV tests.

SUMMARY

The current study presents a retrospective analysis of the testing results collected as part of the management of patients following a possible breach in a specific brand of dialysis machines. Of the two patients who acquired HCV on dialysis, one seroconverted during the breach event. We found a threefold increased prevalence and more than 20-fold higher incidence of HCV in this population than the general population, consistent with other published reports. Given the HCV prevalence and the potential for new transmissions and outbreaks to occur in dialysis units, the current BC recommendations of baseline and six-month anti-HCV testing are reasonable. However, we found low adherence to these policies. There was no evidence of HCV seroconversion in dialysis units outside of the breach event; although the prevalence of HCV in the dialysis population is higher than the general population, it is less than 6%. Therefore, we do not recommend isolation of HCV patients; this follows the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (24). Routine use of HCV-PCR testing in this low-risk population is not recommended; however, we recommend that HCV-PCR testing should be performed on all anti-HCV-reactive patients to establish whether the infection is chronic and, thus, if the patient is infectious. HCV-PCR should also be considered at baseline for persons with HCV risk factors and for returning travellers receiving dialysis or renal transplant in HCV-endemic countries to identify occult and newly acquired infections. This can distinguish HCV infection occurring outside the hemodialysis unit and address concerns when annual testing identifies seroconversion or when enhanced testing occurs due to a potential outbreak.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Alvarez and Linda Hoang for their assistance with data linkage and data cleaning, and for their helpful advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savey A, Simon F, Izopet J, Lepoutre A, Fabry J, Desenclos JC. A large nosocomial outbreak of hepatitis C virus infections at a hemodialysis center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:752–60. doi: 10.1086/502613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furusyo N, Kubo N, Nakashima H, Kashiwagi K, Etoh Y, Hayashi J. Confirmation of nosocomial hepatitis C virus infection in a hemodialysis unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:584–90. doi: 10.1086/502443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delarocque-Astagneau E, Baffoy N, Thiers V, et al. Outbreak of hepatitis C virus infection in a hemodialysis unit: Potential transmission by the hemodialysis machine? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:328–34. doi: 10.1086/502060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou S, Tepper M, Giulivi A. Current status of hepatitis C in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2000;91(Suppl 1):S10–5. S10–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03405100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: A perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:17–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeff LB. Natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S35–46. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oesterreicher C, Hammer J, Koch U, et al. HBV and HCV genome in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1967–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra M, Khaja MN, Hussain MM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral infections in Indian patients with chronic renal failure. Intervirology. 2004;47:374–6. doi: 10.1159/000080883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qadi AA, Tamim H, Ameen G, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus prevalence among dialysis patients in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia: A survey by serologic and molecular methods. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:493–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez L, Lopez P, Arago A, et al. Risk factors for hepatitis B and C in multi-transfused patients in Uruguay. J Clin Virol. 2005;34(Suppl 2):S69–74. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(05)80037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong PN, Fung TT, Mak SK, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in dialysis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1641–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang S, Lai KN. Chronic viral hepatitis in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2005;9:169–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1492-7535.2005.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krajden M. Hepatitis C virus diagnosis and testing. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:S34–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawlotsky JM. Use and interpretation of virological tests for hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S65–73. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreira R, Pinho JR, Fares J, et al. Prospective study of hepatitis C virus infection in hemodialysis patients by monthly analysis of HCV RNA and antibodies. Can J Microbiol. 2003;49:503–7. doi: 10.1139/w03-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeter M, Zoellner B, Polywka S, Laufs R, Feucht HH. Prolonged time until seroconversion among hemodialysis patients: The need for HCV PCR. Intervirology. 2005;48:213–5. doi: 10.1159/000084597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sypsa V, Psichogiou M, Katsoulidou A, et al. Incidence and patterns of hepatitis C virus seroconversion in a cohort of hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:334–43. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandhu J, Preiksaitis JK, Campbell PM, Carriere KC, Hessel PA. Hepatitis C prevalence and risk factors in the northern Alberta dialysis population. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:58–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilli P, Soffritti S, De Paoli Vitali E, Bedani PL. Prevention of hepatitis C virus in dialysis units. Nephron. 1995;70:301–6. doi: 10.1159/000188608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jadoul M, Cornu C, van Ypersele de Strihou C. Universal precautions prevent hepatitis C virus transmission: A 54 month follow-up of the Belgian multicenter study. The Universitaires Cliniques St-Luc (UCL) collaborative group. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1022–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeze C. Hepatitis prompts warning at Scarborough Hospital. Globe and Mail. May 20, 2006.

- 23.Eight dialysis patients at Kyoto hospital have hepatitis B. The Japan Times. Sep 21, 2006.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. MMWR. 2001;50:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fissell RB, Bragg-Gresham JL, Woods JD, et al. Patterns of hepatitis C prevalence and seroconversion in hemodialysis units from three continents: The DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2004;65:2335–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remis R.A study to characterize the epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in Canada 2002. final report Ottawa: Health Canada; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izopet J, Sandres-Saune K, Kamar N, et al. Incidence of HCV infection in French hemodialysis units: A prospective study. J Med Virol. 2005;77:70–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Napoli A, Pezzotti P, Di Lallo D, Petrosillo N, Trivelloni C, Di Giulio S, Lazio Dialysis Registry Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus among long-term dialysis patients: A 9-year study in an Italian region. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:629–37. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furusyo N, Hayashi J, Kakuda K, et al. Acute hepatitis C among Japanese hemodialysis patients: A prospective 9-year study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alavian SM, Einollahi B, Hajarizadeh B, Bakhtiari S, Nafar M, Ahrabi S. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and related risk factors among Iranian haemodialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003;8:256–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1797.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivapalasingam S, Malak SF, Sullivan JF, Lorch J, Sepkowitz KA. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection among patients receiving hemodialysis at an urban dialysis center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:319–24. doi: 10.1086/502058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinrichsen H, Leimenstoll G, Stegen G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in haemodialysis patients: A multicentre study in 2796 patients. Gut. 2002;51:429–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Othman B, Monem F. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus among hemodialysis patients in Damascus, Syria. Infection. 2001;29:262–5. doi: 10.1007/s15010-001-9156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busek SU, Baba EH, Tavares Filho HA, et al. Hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infection in different hemodialysis units in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:775–8. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albuquerque AC, Coelho MR, Lopes EP, Lemos MF, Moreira RC. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in hemodialysis patients from one center in Recife, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:467–70. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fattovich G, Tagger A, Brollo L, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:400–2. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato S, Fujiyama S, Tanaka M, et al. Coinfection of hepatitis C virus in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 1994;21:159–66. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crespo J, Lozano JL, de la Cruz F, et al. Prevalence and significance of hepatitis C viremia in chronic active hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1147–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liaw YF. Role of hepatitis C virus in dual and triple hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology. 1995;22:1101–8. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zarski JP, Bohn B, Bastie A, et al. Characteristics of patients with dual infection by hepatitis B and C viruses. J Hepatol. 1998;28:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez JL, del Pino N, Lef L, et al. Serum hepatitis C virus RNA in anti-HCV negative hemodialysis patients. Dial Transplant. 1996;25:14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genesca J, Vila J, Cordoba J, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in renal transplant recipients: Epidemiology, clinical impact, serological confirmation and viral replication. J Hepatol. 1995;22:272–7. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]