Abstract

Multiple neurodegenerative diseases are causally linked to aggregation-prone proteins. Cellular mechanisms involving protein turnover may be key defense mechanisms against aggregating protein disorders. We have used a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model to identify cellular responses to proteotoxicity resulting from expression of the human beta amyloid peptide (Aβ). We show up-regulation of aip-1 in Aβ-expressing animals. Mammalian homologues of AIP-1 have been shown to associate with, and regulate the function of, the 26S proteasome, leading us to hypothesize that induction of AIP-1 may be a protective cellular response directed toward modulating proteasomal function in response to toxic protein aggregation. Using our transgenic model, we show that overexpression of AIP-1 protected against, while RNAi knockdown of AIP-1 exacerbated, Aβ toxicity. AIP-1 overexpression also reduced accumulation of Aβ in this model, which is consistent with AIP-1 enhancing protein degradation. Transgenic expression of one of the two human aip-1 homologues (AIRAPL), but not the other (AIRAP), suppressed Aβ toxicity in C. elegans, which advocates the biological relevance of the data to human biology. Interestingly, AIRAPL and AIP-1 contain a predicted farnesylation site, which is absent from AIRAP. This farnesylation site was shown by others to be essential for an AIP-1 prolongevity function. Consistent with this, we show that an AIP-1 mutant lacking the predicted farnesylation site failed to protect against Aβ toxicity. Our results implicate AIP-1 in the regulation of protein turnover and protection against Aβ toxicity and point at AIRAPL as the functional mammalian homologue of AIP-1.

INTRODUCTION

The pathogeneses of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and prion diseases are causally linked to aggregation-prone proteins (1). AD is the leading cause of dementia in the elderly and is expected to become even more prevalent to parallel the progressive increase in human life expectancy. In the USA alone, 4.5 million cases were reported in the year 2000 (2) and 12 million cases were reported globally (3). The number of people living with Alzheimer's in the USA is expected to rise to 13.2 million by 2050 (2).

Current evidence points to the central role of beta amyloid peptide (Aβ) in the pathogenesis of AD (4). Aβ is produced by the sequential proteolytic cleavage of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-site APP cleaving enzyme (BACE1; also known as β-secretase) and γ-secretase, respectively. Aβ accumulates in senile plaques and can also be detected intraneuronally (5). The cellular processes that normally degrade Aβ are not well understood. Anti-Aβ immunotherapy in transgenic mouse models decreased amyloid deposition and improved behavioral performance (6), suggesting a therapeutic potential for treatments that reduce Aβ accumulation. A better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involving Aβ accumulation and turnover is thus needed to identify novel drug targets and develop better therapies.

We have developed multiple Caenorhabditis elegans transgenic strains to model AD (7) and better understand cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in Aβ toxicity, accumulation and clearance. A transgenic worm strain that acutely expresses human Aβ42 in body wall muscle in response to temperature upshift (8) was used in the current study. In these animals, Aβ accumulation at 16°C is minimal and produces no gross pathology. At 25°C, however, high levels of Aβ are expressed and a severe, non-reversible paralysis phenotype starts to develop approximately 24 h after temperature upshift. This highly reproducible response to increased Aβ expression has allowed us to investigate early gene expression changes (i.e. expression changes that occur before detectable pathology) with the goal of identifying components of protective cellular responses. The arsenite-inducible protein (aip-1) is one such early-induced gene.

Here, we show that increased expression of aip-1 reduces Aβ accumulation and attenuates Aβ-induced paralysis. Importantly, AIRAPL, a human homologue of aip-1 (9), can similarly protect from Aβ toxicity in this C. elegans AD model, suggesting an analogous function for this gene that may have relevance to AD.

RESULTS

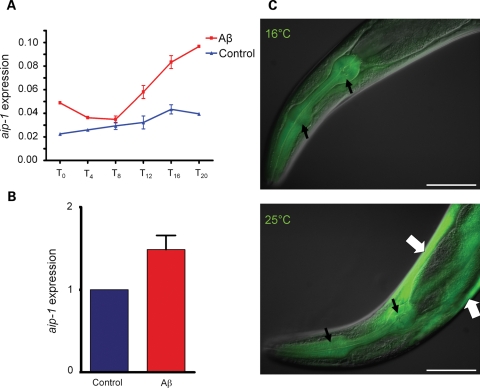

aip-1 is induced in response to body wall muscle-specific expression of the human Aβ42 peptide

We have previously used microarray analysis to identify Aβ-induced gene expression changes in a C. elegans AD model (8). In the current study, we extended this analysis by examining earlier time points and by using a control strain that employed an identical transgenic construct to inducibly express GFP in body wall muscle (strain CL2179). Affymetrix GeneChip whole-genome arrays (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were employed to identify differentially expressed genes in Aβ-expressing animals (strain CL4176) compared with CL2179 control strain. Synchronous worm populations were grown at 16°C for 36 h to the third larval stage and were then transferred to 25°C. Worms were collected at the time of temperature upshift and later at 4-h intervals up to 20 h post-upshift. Total RNA was extracted and used to assay gene expression patterns using GeneChip arrays. aip-1, encoding arsenite-inducible protein, was among the identified upregulated genes. It has been shown that aip-1 is induced in response to and is protective against arsenite toxicity and hence its name (10). Microarray data showed up-regulation of aip-1 at the transcriptional level starting 8 h after induction (PI) of Aβ42. aip-1 induction peaked at 1.9-fold increase by 16 h PI (two-tail t-test P = 0.0011) (Fig. 1A). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on four replicates from the 8-h to the 16-h time points showing that the increase in aip-1 levels was strongly significant (P = 0.0022). Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (real-time RT–PCR) data confirmed this result at the 16-h time point, where 1.49-fold increase in aip-1 transcript levels in Aβ42 animals was observed (two-tail t-test P = 0.0414) (Fig. 1B). To confirm that the localization of aip-1 induction is in body wall muscles, we made use of a transcriptional aip-1/GFP reporter transgene expressed in strain SJ4001 (10). This transgene was crossed into Aβ42 strain CL4176, and GFP expression was assayed both with and without temperature induction of Aβ42 expression. GFP expression was observed in body wall muscle cells specifically upon induction of the Aβ42 transgene (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Expression of the human amyloid-β42 leads to an increase in aip-1 transcript accumulation. (A) Induction of aip-1 shown using GeneChip microarrays (Affymetrix, Inc.). aip-1 levels in an Aβ-expressing strain, CL4176, were compared to a control strain expressing GFP. In these strains, Aβ42 or GFP were expressed at low levels at 16°C, while moving the animals to 25°C induced high levels of transgene expression (see Materials and Methods for details of temperature inducibility). Worms were harvested at the time of temperature change (T0) and every 4 h afterwards until 20 h later (T4–T20). Error bars represent the SEM. (B) Microarray data were confirmed using real-time RT–PCR to measure aip-1 levels at the T16 time point. Data were plotted as a fold change compared with the GFP control strain. Error bars represent the SEM. (C) Aβ and aip-1 expression were correlated in an aip-1/GFP transcriptional reporter strain. GFP fluorescence was detected in the pharynx at 16 and at 25°C (narrow black arrows), which is consistent with constitutive pharyngeal expression. In body wall muscle, however, GFP fluorescence was only detectable at 25°C (wide white arrows), which is consistent with Aβ42-stimulated induction of aip-1 promoter. Size bar = 100 µm.

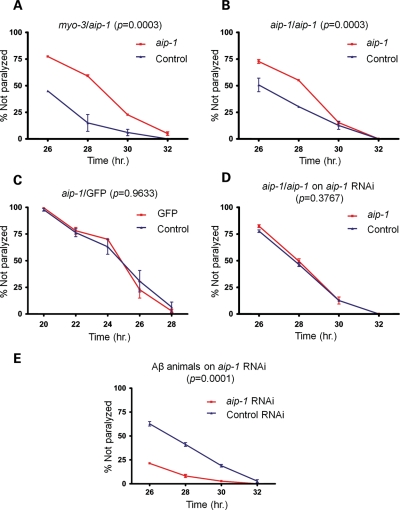

AIP-1 is protective against Aβ42 toxicity

The up-regulation of AIP-1 could have been a protective response used by the worms to alleviate Aβ42 toxicity. Alternatively, it could have been part of the toxic mechanism itself. To test these two possibilities, we employed Aβ42 transgenic worms that had AIP-1 either overexpressed or knocked down. To generate AIP-1 overexpression strains, CL4176 animals were transformed with extra-chromosomal arrays containing a variety of constructs of aip-1 along with a construct containing a myo-3 promoter fused upstream of DsRed coding sequence (myo-3/DsRed) chimera as a marker to track animals that were successfully transformed (Note: In this manuscript, genetic constructs containing a promoter sequence of one gene fused upstream of a coding sequence of another gene are indicated by a slash separating the two gene names, while constructs containing two coding sequences of two different genes fused in tandem are indicated by two colons separating gene names. For example, myo-3/DsRed and myo-3::DsRed would be used to indicate a promoter-coding sequence and a coding sequence–coding sequence fusions, respectively). We found that the paralysis phenotype of Aβ42-expressing worms was less severe in animals that had inherited an aip-1 construct under the control of either an aip-1 or a myo-3 promoter, compared with animals that had lost the transgene (the latter were identified by the loss of DsRed fluorescence). The decreased severity, manifested in the delayed paralysis of transgenic worms (Fig. 2A and B), is consistent with a protective role of AIP-1. This protective effect was shown to be AIP-1-dependent because it was observed in the animals described above, but not in animals carrying an aip-1/GFP transcriptional reporter (Fig. 2C). Similar protection was also observed in animals carrying an extra-chromosomal array containing full-length aip-1/GFP::aip-1 and myo-3/DsRed chimeras (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). To further confirm the dependence of this protective effect on AIP-1 levels, we tested whether knocking down aip-1 by RNA interference (RNAi) could reverse this protective effect and enhance paralysis. We show that the protective effect was completely reversed by aip-1-specific RNAi in aip-1 and GFP::aip-1 overexpression animals (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B). Furthermore, knocking down aip-1 by RNAi in CL4176 animals exacerbated their paralysis phenotype (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

AIP-1 protects against Aβ toxicity in a C. elegans model. Graphs shown here depict the progression of paralysis of Aβ-expressing animals after temperature induction. Animals were grown for 36 h at 16°C to keep Aβ expression at low levels, not enough to induce paralysis. Animals were then moved to 25°C to induce high levels of Aβ expression and paralysis. The horizontal axis represents the number of hours the animals spent at 25°C. (A) The paralysis phenotype was delayed in animals overexpressing aip-1 from a transgenic extra-chromosomal array under the control of either myo-3 or (B) aip-1 promoter (red curves). Blue curves represent the progression of paralysis in animals that lost the extra-chromosomal array and are thus carrying only the chromosomal copies of aip-1. (C) A negative control expressing GFP under the control of an aip-1 promoter shows no effect on paralysis, which argues against a non-specific transgene effect. (D) The effect of aip-1 overexpression on the paralysis phenotype is reversed by aip-1-specific RNAi, which is consistent with an AIP-1-dependent effect. (E) aip-1 knockdown by RNAi exacerbates the paralysis phenotype. The control RNAi curve represents animals fed E. coli (strain: HT115) carrying pL4440 vector, which only contains the multiple-cloning site between the two convergent T7 polymerase promoters (11) and was used as a negative control. Error bars represent the SEM. The P-values shown were obtained using a two-way ANOVA.

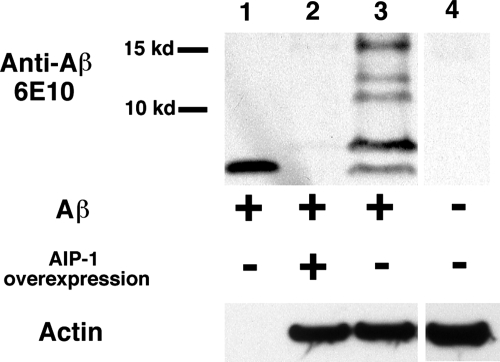

Accumulation of the Aβ42 peptide is decreased in animals overexpressing AIP-1

Next we were interested in investigating the mechanism underlying AIP-1 protection against Aβ42 toxicity. Since AIP-1 has been shown to modulate proteasome function (9,12), we speculated that the protection provided by AIP-1 could simply be a result of increased turnover and clearance of the toxic peptide. To test this hypothesis, we used immunoblotting to show Aβ42 levels in worms that overexpressed AIP-1 in comparison to worms that did not. A mixed population of the transgenic animals was grown at 16°C to the L1–L3 stage. The worms were sorted into two groups based on the fluorescence of a DsRed marker: AIP-1 overexpressing animals (which retained red fluorescence) and worms expressing wild-type levels of AIP-1 (which lost red fluorescence). Worm sorting was done using a COPAS Biosorter (Union Biometrica, Inc., Holliston, MA). Western blot analysis using 6E10 anti-Aβ antibodies showed decreased accumulation of Aβ42 in the AIP-1-overexpression animals compared with their isogenic siblings expressing wild-type levels of AIP-1 (Fig. 3). The reduced accumulation of Aβ42 that resulted from AIP-1 overexpression is consistent with increased clearance as a protective mechanism. Whether the increased clearance is Aβ42-specific was not clear at this point. To answer this question, we examined the effect of AIP-1 overexpression on the accumulation of GFP::degron, an aggregating form of GFP that is also toxic when inducibly expressed in C. elegans body wall muscle (13).

Figure 3.

aip-1 overexpression results in decreased accumulation of Aβ42 peptide. Aβ levels were compared between animals overexpressing aip-1 and animals expressing wild-type levels of aip-1 by western blotting using the anti-Aβ antibody 6E10. Migration of monomeric Aβ was demonstrated by a purified monomeric peptide (lane 1). Aβ-specific bands were determined by comparison to a control strain (N2) lacking Aβ transgene (lane 4). A dramatic decrease in Aβ levels is shown in animals overexpressing aip-1 compared with a control strain (lanes 2 and 3, respectively).

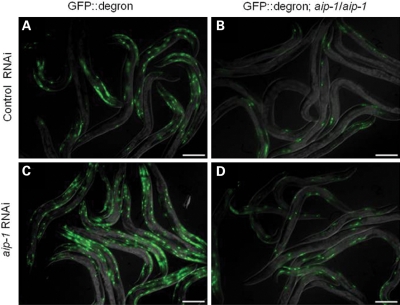

Protein turnover enhanced by AIP-1 is not Aβ-specific

GFP::degron is a non-disease associated model aggregating protein that causes a paralysis phenotype similar to that produced by Aβ42 when expressed in body wall muscles of C. elegans. Expression of GFP::degron in C. elegans body wall muscle leads to the formation of perinuclear aggregates readily visible by epifluorescent microscopy (13). GFP::degron worms transformed with aip-1 overexpression arrays, however, accumulated markedly fewer GFP aggregates. As expected, RNAi directed against aip-1 transcripts caused increased accumulation of GFP::degron aggregates and partially restored the reduced aggregate accumulation caused by AIP-1 overexpression (Fig. 4). Our results are consistent with a model in which AIP-1 functions by increasing general protein turnover as opposed to specifically targeting Aβ42.

Figure 4.

AIP-1 reduces the accumulation of GFP::degron, an aggregation-prone variant of GFP, in body wall and vulval muscles. (A) Animals carrying the integrated array dvIs38 (worm strain CL2337), which contains GFP::degron under the control of a myo-3 promoter and a long 3′-UTR required for temperature inducibility, accumulate GFP aggregates in their body wall muscles and suffer a paralysis phenotype similar to that induced by Aβ. (B) Transgenic overexpression of aip-1 reduces GFP::degron accumulation. (C) Reduction of aip-1 expression by RNAi causes increased accumulation of GFP::degron compared with animals treated with control RNAi. (D) aip-1 RNAi partially reverses the decreased GFP::degron accumulation caused by transgenic overexpression of aip-1. Size bar = 150 µm.

An AIP-1 human homologue, AIRAPL, has a similar protective effect against Aβ toxicity

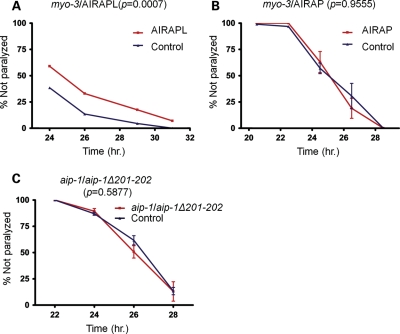

To explore the possible applicability of our data to human disease, we examined whether human homologues of AIP-1 could mimic the protective effect of AIP-1 in our worm model. There are two human and mammalian homologues to AIP-1, AIRAP (ZFAND2A) and AIRAPL (ZFAND2B) (10,12). The amino acid identities of AIRAP and AIRAPL to AIP-1 are 43 and 38%, respectively. We engineered Aβ42-expressing worms to overexpress each of the human homologues from an extra-chromosomal array. Both of the human homologues were expressed under the control of a myo-3 promoter. We found that AIRAPL, but not AIRAP, had a protective effect that delayed the paralysis phenotype of Aβ42-expressing animals in a manner similar to AIP-1 protection (Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 5.

An AIP-1 human homologue, AIRAPL, has a protective effect against Aβ42 toxicity and AIP-1 putative farnesylation site is essential for its protective effect against Aβ42 toxicity. (A) The paralysis phenotype of Aβ42-expressing animals is delayed by human AIRAPL overexpression. (B) Human AIRAP overexpression had no effect on the paralysis phenotype of Aβ42-expressing animals. (C) Deleting the C-terminal two residues in AIP-1 disrupts its putative isoprenylation site and abolishes its protective effect. Error bars represent the SEM. The P-values shown were obtained using a two-way ANOVA.

Interestingly, we and others (12) have identified putative farnesylation sites at the C termini of both AIP-1 and AIRAPL (CTVS and CSLC, respectively), but failed to identify such site in AIRAP. Since the availability of AIP-1 C terminus for the assumed farnesylation was shown to be important for its prolongevity effect and since the C terminus of AIRAPL was shown to play a role in regulating its incorporation into the proteasome (12), we postulated that AIP-1/AIRAPL putative farnesylation sites might be required for the proteins’ protective effect in our model. Therefore, we tested whether the farnesylation site is essential for AIP-1 protective effect using an AIP-1 mutant deleted for the last two residues (aip-1Δ201-202), which disrupts the consensus sequence of its putative farnesylation site (14,15). Overexpressing the deletion mutant in Aβ42 animals did not show any protection, suggesting that AIP-1 may in fact be farnesylated and its farnesylation plays an important role in AIP-1 protective mechanism (Fig. 5C). To test the stability of the truncated AIP-1 mutant, we generated a GFP-tagged aip-1Δ201-202 mutant, which was not protective (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), but GFP fluorescence was detectable (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). These observations indicate that the truncation mutation did not destabilize the protein. We have also shown that the lack of protection is unlikely caused by the GFP tag, since a GFP-tagged, wild-type AIP-1 was protective and its protection was eliminated by aip-1-specific RNAi (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that expression of the Aβ42 peptide in a transgenic C. elegans AD model leads to the cell-autonomous induction of aip-1. This induction appears to be a protective response, as transgenic overexpression of aip-1 protects from Aβ42 toxicity and RNAi knockdown of aip-1 increases Aβ42 toxicity. AIRAPL, a human homologue of AIP-1, can substitute for AIP-1 to protect from Aβ toxicity, whereas AIRAP, another human homologue of AIP-1, cannot. Unlike AIRAPL and AIP-1, AIRAP lacks a C-terminal CAAX isoprenylation site. Mutation of the AIP-1 CAAX site also eliminates AIP-1 protection against Aβ toxicity, suggesting that isoprenylation is critical for AIP-1 protective function.

Our results are complementary to those of Yun et al. (12), who have recently demonstrated that aip-1 is required for normal lifespan in C. elegans, and overexpression of aip-1 protects against multiple forms of proteotoxicity. They also demonstrated the importance of the C-terminal portion of AIRAPL for regulating its association with the proteasome. Interestingly, these researchers found that aip-1 requires its normal C-terminal sequences to promote normal lifespan; consistent with the view that isoprenylation is critical for AIP-1 function. Our direct demonstration that aip-1 overexpression reduces Aβ accumulation also supports the proposal that aip-1 is a positive regulator of proteasomal function (9).

Recent evidence showed that the role of AIP-1 and its mammalian homologues as modulators of proteasome function capable of changing the molecular composition of the proteasome is not a unique one. It has been demonstrated that the inducible proteins, LMP-2 (low-molecular mass polypeptide -2), LMP-7 and MCEL-1 (multicatalytic endopeptidase complex-like-1), which are induced by interferon gamma, are capable of replacing three constitutive subunits of the 20S proteasome to modify its catalytic function and produce what is referred to as ‘immuno-proteasome’. The immuno-proteasome is involved in antigen processing and its modification from a conventional proteasome (i.e. proteasome with constitutively expressed subunits) leads to digesting antigens into peptides that are more suitable for binding major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and enhancing the immune response (16). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the existence of functionally and structurally distinct subpopulations of proteasomes in biological systems is more widespread than what was previously thought (17). The existence of proteasomal subpopulations in murine cardiac and hepatic cells has been reported. Functional distinctiveness of these subpopulations is associated with variations in subunit composition and post-translational modifications (17). Moreover, it has been shown that phosphorylation of cardiac 20S proteasomes enhances the peptidase activity of individual proteasomal subunits in a substrate-specific manner (18).

However, it is unclear how the requirement for the C-terminal isoprenylation site fits a model in which AIP-1 acts solely or primarily through proteasomal activation. Both AIRAP and AIRAPL can apparently activate proteasomal proteolysis in vitro (12), although only AIRAPL is protective in the C. elegans model. We have not been successful in demonstrating that treatments that inhibit proteasomal function (e.g. MG132 treatment or RNAi against proteasomal subunits), reverse AIP-1 protective effects, although this negative result may be due to technical limitations (data not shown). Given our current results, it remains possible that AIP-1 activates additional protein degradation pathways (e.g. autophagosome/lysosomal protein degradation).

Our studies looking at the effect of aip-1 expression on transgenic strains expressing GFP::degron, a model toxic aggregating protein (13), demonstrates that aip-1 effects are not restricted to Aβ. Similar results were also obtained by Yun et al. (12) using a YFP::polyglutamate model toxic protein. Interestingly, we did not observe significant induction of aip-1 by expression of GFP::degron, even though aip-1 expression reduces the accumulation of toxic GFP::degron aggregates. This result suggests that, at least in C. elegans, there are latent protective processes that are not necessarily engaged when cells are confronted with proteotoxicity. Given that AIRAPL also protects against Aβ toxicity in our model, we suggest that treatments designed to induce or activate AIRAPL may have therapeutic potential in human neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, we speculate that mutations that reduce AIRAPL (or AIRAP) may be identified as risk alleles for neurodegenerative diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and temperature induction system

Worm strain SJ4001 was a gift from David Ron. Construction of CL4176 [smg-1 (cc546ts); dvIs27], CL2179 [smg-1 (cc546ts); dvIs179] and CL2337 [smg-1 (cc546ts); dvIs38] has been previously described (8,13). These strains contain transgenes containing abnormally long 3′-end untranslated sequences that target their transcripts for destruction by the mRNA surveillance system. Inclusion of a temperature-sensitive mutation in smg-1 (19), a gene essential for mRNA surveillance, results in temperature-dependent induction of Aβ42 (CL4176), GFP (CL2179) or GFP::degron (CL2337) in body wall muscle.

Construction of transgenic C. elegans strains

Transgenic animals were produced by DNA microinjection. Plasmids were co-injected with pCL148 containing a myo-3/DsRed construct that produced red fluorescence in body wall and vulval muscles as a morphological marker. Integrated lines were obtained by γ-irradiation as described previously (20).

RNA purification for gene expression analysis

Strains CL2179, CL2337 and CL4176 were grown and harvested using the same regimen. Synchronous populations of first-larval stage animals were grown at 16°C (permissive temperature) for 36 h after which animals were moved to 25°C (non-permissive temperature). A portion of the animals was harvested and frozen at the time of temperature upshift and every 4 h until 20 h post-upshift. Total RNA was purified using Qiagen's RNeasy mini kit (catalogue number 74104).

Microarrays and data analysis

Microarays were done using Affymetrix high density chips at the core facility of University of Colorado at Boulder. Scanning and image processing was done using GeneChip® Scanner 3000 Targeted Genotyping System and GeneChip Operating Software version 1.4 (Affymetrix, Inc.). Data analysis was done using a few techniques including manual analysis and linear normalization in Excel spreadsheets and GeneSpring (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Reverse transcription and real-time polymerase chain reaction

cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcribing mRNA using Oligo(dT)12–18 primers and Invitrogen's SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System (catalogue number 11904-018). Real-time PCR was done using an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time amplification of aip-1 was performed using forward and reverse primers, aip-1Fa (TCCGACTGGCTCAAGAATTT) and aip-1Ra (TTGATCAACATTGACATCTTTCG), respectively. Expression level of aip-1 was calculated using ΔΔCT method combined with a normalization strategy inspired by the work of Vandesompele et al. (21). Briefly, ΔCT was calculated as the geometric mean of the differences between the CT value of aip-1 and the CT values of each of four housekeeping genes (ama-1, gpd-3, rps-7 and eft-2). The CT value of each gene was obtained by averaging four replicas in each of three different experiments that were run independently from each other. ΔΔCT was calculated by subtracting ΔCT of the control strain (i.e. CL2179) from ΔCT of the experimental strain (i.e. CL4176). Relative expression values were calculated for each of the three experiments as 2−ΔΔCT. Data were plotted using GraphPad Prism software.

Molecular cloning and mutagenesis

Plasmid pCL148 containing a myo-3/DsRed construct was made by cleaving pPD118.20 (myo-3/GFP expression vector; Fire lab 1997 expression vector kit, http://ftp.ciwemb.edu/PNF:byName:/FireLabWeb/FireLabInfo/FireLabVectors/) with AgeI and EcoRI to remove the GFP sequences, then inserting an AgeI/EcoRI fragment containing DsRed monomer sequences (derived from Clontech pDsRed monomer vector). Plasmid pCL159 containing aip-1/GFP construct was constructed by cloning aip-1 upstream genomic sequences immediately upstream of GFP. Upstream sequences of aip-1 were amplified by PCR, using primers aip-1F-pro (GTTGGAAGCAAAACAAGA) and aip-1R-pro (GCGGTACCAGCTGAATAAAGCAAACG). The PCR product was cloned as a SalI-KpnI fragment upstream of GFP open reading frame (ORF) in a pPD95.69-based vector (Fire lab 1995 expression vector kit, http://ftp.ciwemb.edu/PNF:byName:/FireLabWeb/FireLabInfo/FireLabVectors/). The fragment was generated utilizing the natural SalI site of aip-1 upstream sequences and the KpnI site introduced by the reverse primer. Plasmid pCL178 containing aip-1/GFP::aip-1 construct was constructed by first fusing aip-1 ORF and transcriptional termination sequences (TER) to GFP ORF using two consecutive PCR reactions. The first PCR was done using primers aip-1F-GFP (GGCATGGATGAACTATACAAAATGGCGGAGTTCCC) and aip-1R-ApaI (CCGGGCCCAAGAGGGCGTGCC) to amplify aip-1 ORF/TER and introduce 21 nucleotides overlapping the 3′-end of GFP ORF upstream of aip-1. The second PCR used GFP-KpnI (ACGGTACCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCA) as a forward primer and the first PCR product as a reverse primer to amplify GFP ORF while adding aip-1 ORF/TER downstream. The final PCR product was cloned as a KpnI-ApaI fragment into pCL159. Plasmid pCL194 containing aip-1 promoter, ORF and transcription termination sequences was constructed by cloning a PCR product containing aip-1 ORF and termination sequences downstream of aip-1 promoter in a pCL159-based plasmid. The PCR product was amplified from genomic DNA, using primers aip-1F-KpnI (CCGGTACCATGGCGGAGTTCCCAAA) and aip-1R-ApaI, which introduced a KpnI site upstream and an ApaI site downstream of aip-1 sequences. The same PCR product was cloned into plasmid pCL137 [containing a myo-3/hsp-16.2 construct (13)] to replace hsp-16.2 sequences and generate plasmid pCL195 containing a myo-3/aip-1 construct. An aip-1Δ201-202 mutant was generated by two consecutive PCR reactions. The first PCR was used to amplify aip-1 ORF, excluding the two codons immediately upstream of the stop codon and added 24 nucleotides overlapping the stop codon and downstream sequences. Primers aip-1F-KpnI and aip-1R-del V201+S202 (AAATATACACTAAATTGGATGCTAGGTGCAGTTGGAATTGG) were used in the first PCR. The second PCR was done using primer aip-1R-ApaI and first PCR product. The resulting kpnI-ApaI fragment was cloned into pCL194 to replace wild-type aip-1 sequences.

Microscopy

Microscopy was done using a Zeiss upright Axioskop epifluorescence microscope equipped with 40× air (NA 0.75), 100× oil (NA1.3) Plan Neofluor objectives and Intelligent Imaging Innovations digital deconvolution retrofit system. Live animals were mounted in 10 µl of 1 mm levamisole placed on the surface of a 2% agarose pad and a glass cover-slip was laid on top. Levamisole was used to reduce the movement of the worms. Fixed animals were mounted in Vectashield Hard Set mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Inc.).

RNA interference

Gene-specific knock downs were done by feeding the worms Escherichia coli strain HT115 making gene-specific dsRNAs (11). The RNAi plates were made by pouring Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) containing 1 mm isopropyl thiogalactoside and ampicillin (50 µg/ml) in 50 mm plates. Plates were kept in the dark overnight at room temperature and were then spotted with 100 µl of E. coli strain HT115 transformed with the proper plasmid. This was followed by another overnight, room temperature incubation to allow for bacterial growth, after which plates were either used immediately or stored at 4°C. We had used plates that had been stored at 4°C for a maximum of 10 days. Plates that had been stored for longer periods of time were not used for experiments and were discarded.

We have seen an effect by knocking down some genes starting with a synchronous egg lay on RNAi plates and incubating as little as 48 h. Other genes, however, required maternal exposure to the RNAi (data not shown). For these genes, third larval stage animals were grown on the RNAi plates till young adulthood. A synchronous egg lay using these young adults was then done on fresh RNAi plates and the resulting animals were used to show the gene-specific knock down effect. Animals feeding on HT115 bacteria harboring the empty vector, pl4440, were used as negative control.

Paralysis assay

Young adult hermaphrodites (10–15 per plate) were allowed to lay eggs on 5 cm NGM plates spotted with E. coli strain OP50. Egg lay lasted 2–4 h at 16°C. Adults were then removed and plates were incubated at 16°C. After 36 h, plates were shifted to 25°C and incubated until scored for paralysis. A worm was scored paralyzed if it did not move at a touch stimulus with a platinum picker. We noticed that the paralysis timing of the same strain differed between experiments done at different times, but the difference between experimental conditions done in parallel remained reproducible.

For strains carrying multiple extra-chromosomal copies of aip-1 in addition to myo-3/DsRed, worms that lost the transgenic array (lacked DsRed fluorescence) were used as negative controls. To eliminate bias, worms were scored for paralysis under a bright-light dissecting microscope (to allow the person scoring paralysis to do so without being able to distinguish transgenic from non-transgenic worms) and were subsequently sorted into transgenic (worms that showed red fluorescence) versus non-transgenic under a fluorescence dissecting scope.

Whenever RNAi treatment preceded the paralysis assay, worms were grown for one or two generations on RNAi plates spotted with HT115 bacteria harboring gene-specific RNAi plasmid. In one-generation experiments, synchronous egg lays were done at 16°C followed by 36-h incubation at 16°C and then 18–24-h incubation at 25°C. In two-generation experiments, third larval stage hermaphrodites were grown at 16°C on RNAi plates until young adulthood. Afterwards, a synchronous egg lay on fresh plates was done, followed by 36-h incubation at 16°C and then 18–24-h incubation at 25°C. Animals were scored for paralysis immediately after the last incubation. A negative control was done by growing worms on HT115 cells transformed with an empty vector in parallel with each experimental condition. All paralysis data plots and statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism software.

Immunoblotting

A synchronous worm population of strain CL859 (Aβ-expressing animals that overexpress myo-3/aip-1 from an extrachromosomal array containing myo-3/DsRed as a phenotypic marker) was obtained by means of synchronous egg lays. Worms were grown on NGM agar plates containing 2% peptone and spread with a loan of E. coli strain RW2. Worms were washed off the plates and rinsed with S basal buffer (100 mm sodium chloride, 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.0) (22). Worms overexpressing aip-1 were separated from those expressing wild-type levels of the gene based on the presence or absence of DsRed fluorescence using a COPAS Biosorter (Union Biometrica, Inc.). Sorted worms were rinsed once in S basal buffer and once in distilled water, and were then pelleted by centrifugation. An equal volume of 1 mm protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma #P2714) in distilled water was added to the worm pellet, which was immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Protein concentration was determined using Coomassie Plus kit (Thermo Scientific, catalogue number 23236) following manufacturer recommendations.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (23). Briefly, 20 µg protein were loaded per lane and SDS–PAGE was performed using NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen, catalogue number NP0321). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Osmonics, catalogue number WP4HY00010) and membranes were blocked in TBS-Tween (100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm sodium chloride, 0.1% Tween-20) containing 5% skim milk.

Membranes were probed with anti-Aβ antibody, clone 6E10 (Chemicon, catalogue number MAB1560) diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer before use as primary antibody. Anti-actin antibody, clone JLA20 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) was diluted 1:100 and used to label actin to ensure equal loading. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated, goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma) was used as secondary antibody and HRP was visualized using Amersham ECL reagent (GE Healthcare, catalogue number RPN2109).

Statistical analysis

Significance was determined using a two-tail student t-test in the PCR experiment. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine significance in the paralysis assays. Error bars in PCR and paralysis graphs represent the SEM.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant # AG12423).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank David Ron for providing C. elegans strain SJ4001 and Jey Yerg for constructing plasmid pCL148 and helping with growing worm populations and microarray experiments. We would also like to thank Kate Worster for help sorting transgenic nematodes and Justin Springett for assistance with media preparation. The JLA20 monoclonal antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD. We thank the microarray core facility of the University of Colorado at Boulder for assisting with the microarray study.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross C.A., Poirier M.A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004;10(Suppl.):S10–S17. doi: 10.1038/nm1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebert L.E., Scherr P.A., Bienias J.L., Bennett D.A., Evans D.A. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Citron M. Strategies for disease modification in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:677–685. doi: 10.1038/nrn1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy J., Selkoe D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gouras G.K., Almeida C.G., Takahashi R.H. Intraneuronal accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2005;26:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacskai B.J., Kajdasz S.T., Christie R.H., Carter C., Games D., Seubert P., Schenk D., Hyman B.T. Imaging of amyloid-β deposits in brains of living mice permits direct observation of clearance of plaques with immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2001;7:369–372. doi: 10.1038/85525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Link C.D. Caenorhabditis elegans models of age-associated neurodegenerative diseases: lessons from transgenic worm models of Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2006;41:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Link C.D., Taft A., Kapulkin V., Duke K., Kim S., Fei Q., Wood D.E., Sahagan B.G. Gene expression analysis in a transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Alzheimer's disease model. Neurobiol. Aging. 2003;24:397–413. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanhill A., Haynes C.M., Zhang Y., Min G., Steele M.C., Kalinina J., Martinez E., Pickart C.M., Kong X.P., Ron D. An arsenite-inducible 19S regulatory particle-associated protein adapts proteasomes to proteotoxicity. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:875–885. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sok J., Calfon M., Lu J., Lichtlen P., Clark S.G., Ron D. Arsenite-inducible RNA-associated protein (AIRAP) protects cells from arsenite toxicity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:6–15. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0006:airapa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmons L., Court D.L., Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yun C., Stanhill A., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Haynes C.M., Xu C.F., Neubert T.A., Mor A., Philips M.R., Ron D. Proteasomal adaptation to environmental stress links resistance to proteotoxicity with longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7094–7099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707025105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link C.D., Fonte V., Hiester B., Yerg J., Ferguson J., Csontos S., Silverman M.A., Stein G.H. Conversion of green fluorescent protein into a toxic, aggregation-prone protein by C-terminal addition of a short peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1808–1816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter M., Chavrier P., Nigg E.A., Zerial M. Isoprenylation of rab proteins on structurally distinct cysteine motifs. J. Cell Sci. 1992;102:857–865. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lane K.T., Beese L.S. Structural biology of protein farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase type I. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:681–699. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz K., van Den Broek M., Kostka S., Kraft R., Soza A., Schmidtke G., Kloetzel P.M., Groettrup M. Overexpression of the proteasome subunits LMP2, LMP7 and MECL-1, but not PA28 alpha/beta, enhances the presentation of an immunodominant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus T cell epitope. J. Immunol. 2000;165:768–778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drews O., Wildgruber R., Zong C., Sukop U., Nissum M., Weber G., Gomes A.V., Ping P. Mammalian proteasome subpopulations with distinct molecular compositions and proteolytic activities. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:2021–2031. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700187-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zong C., Gomes A.V., Drews O., Li X., Young G.W., Berhane B., Qiao X., French S.W., Bardag-Gorce F., Ping P. Regulation of murine cardiac 20S proteasomes: role of associating partners. Circ. Res. 2006;99:372–380. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237389.40000.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Getz S., Xu S.Q., Fire A. Temperature sensitive smg mutations as a tool to engineer conditional expression: a progress report. Worm Breeder's Gazette. 1997;14:26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link C.D. Expression of human beta-amyloid peptide in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9368–9372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:1–12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link C.D., Fonte V., Roberts C.M., Hiester B., Silverman M.A., Stein G.H. The β amyloid peptide can act as a modular aggregation domain. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008;32:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.