Abstract

Usher syndrome 3A (USH3A) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by progressive loss of hearing and vision due to mutation in the clarin-1 (CLRN1) gene. Lack of an animal model has hindered our ability to understand the function of CLRN1 and the pathophysiology associated with USH3A. Here we report for the first time a mouse model for ear disease in USH3A. Detailed evaluation of inner ear phenotype in the Clrn1 knockout mouse (Clrn1−/−) coupled with expression pattern of Clrn1 in the inner ear are presented here. Clrn1 was expressed as early as embryonic day 16.5 in the auditory and vestibular hair cells and associated ganglionic neurons, with its expression being higher in outer hair cells (OHCs) than inner hair cells. Clrn1−/− mice showed early onset hearing loss that rapidly progressed to severe levels. Two to three weeks after birth (P14–P21), Clrn1−/− mice showed elevated auditory-evoked brainstem response (ABR) thresholds and prolonged peak and interpeak latencies. By P21, ∼70% of Clrn1−/− mice had no detectable ABR and by P30 these mice were deaf. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions were not recordable from Clrn1−/− mice. Vestibular function in Clrn1−/− mice mirrored the cochlear phenotype, although it deteriorated more gradually than cochlear function. Disorganization of OHC stereocilia was seen as early as P2 and by P21 OHC loss was observed. In sum, hair cell dysfunction and prolonged peak latencies in vestibular and cochlear evoked potentials in Clrn1−/− mice strongly indicate that Clrn1 is necessary for hair cell function and associated neural activation.

INTRODUCTION

Usher syndrome is the most common cause of sensory impairment wherein deafness and blindness occur together. It is clinically subdivided into three types based on the degree of deafness and the presence of vestibular dysfunction (1). USH1 is the most severe form and is characterized by profound congenital hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction combined with pre-pubertal onset of retinitis pigmentosa (RP). In USH2 hearing loss is milder, the onset of RP is after puberty and vestibular function is unaffected. USH3 patients show progressive hearing loss and variable degrees of vestibular dysfunction.

At least 13 loci have been linked to the three types of Usher syndrome, including one locus linked to USH3 (http://webh01.ua.ac.be/hhh/). Genes associated with many of these loci have been identified and they encode proteins that belong to diverse classes of proteins (2,3). CLRN1 (USH3A), the only member of USH3, codes for a four transmembrane-domain protein (4) belonging to a large family of transmembrane proteins which include both the tetraspanin and the claudin families. Members of this family participate in a variety of functions including regulating cell morphology, motility, invasion, fusion and signaling (5–7). Tetraspanins are known to form homo-multimers leading to the assembly of microdomains that interact and nucleate the congregation of other non-tetraspanin membrane proteins. CLRN1 shares some of the features common to tetraspanin proteins, including the predicted four transmembrane domain topology, and very short intracellular loops. This protein may play a vital role in creating and assembling membrane microdomains involved in adhesion strengthening and signaling (7). However, the precise function of CLRN1 in the inner ear is not known.

Several different mutations of human CLRN1 have been found that cause progressive hearing loss with variable penetrance linked to the N48K mutation, or profound hearing impairment linked to the Y176 stop mutation (4). Similarities between CLRN11 and the calcium channel gamma subunit protein 2 (CACNG2, stargazin) have been proposed (4). Stargazin has been shown to play a key role in the shaping and maintenance of cerebellar synapses (8). However, in vivo studies are needed to reveal the molecular mechanism that underlies CLRN1 function. USH3 is inherited in a recessive pattern, suggesting that the loss of function is the cause of the disease. Therefore, studies of the Clrn1-null mouse should provide insights into the involved pathogenic mechanisms. Here we report a detailed analysis of the Clrn1−/− mouse inner ear phenotype and describe the expression pattern of Clrn1 in the vestibular and cochlear neuroepithelia. Our results suggest that Clrn1 plays a novel role in hair cell development and function.

RESULTS

Clarin-1 is expressed in hair cells and ganglion cells of the inner ear

To determine the expression pattern of Clrn1 in the cochlear and vestibular hair cells, we carried out mRNA in situ hybridization at embryonic (E) stages 16.5, 18.5 and postnatal (P) day 0, 3 and 5. Clrn1 was found to be expressed as early as E16.5 in the inner ear, in hair cells of the auditory and vestibular sensory epithelia and in the spiral ganglion neurons. Expression was most apparent in the spiral ganglion cells (SGCs) and in the hair cells of the basal turn of the cochlea compared with apical turns at early stages, suggesting the time and location of the onset of Clrn1 expression (Fig. 1). Hair cell-specific genes typically are initially expressed in the more mature hair cells in the basal cochlea and spread to the apical hair cells with continued development, paralleling the gradient in hair cell maturation. By E18.5, all cochlear hair cells expressed Clrn1, with a higher level of expression in the outer hair cells (OHCs) as compared to inner hair cells (IHCs) (Fig. 1). Expression of Clrn1 was detected by in situ hybridization in the inner ear of all stages analyzed, i.e. from both E16.5 to P5, confirming previously reported in situ data (4), and from P30 and P60 by RT–PCR (Fig. 3D). Clrn1 was also expressed in the vestibular hair cells and Scarpa's ganglion cells. Closer examination of the Clrn1 labeling in the embryonic saccule revealed strong expression in the hair cells and a much weaker expression in Scarpa's ganglion cells (Fig. 2).

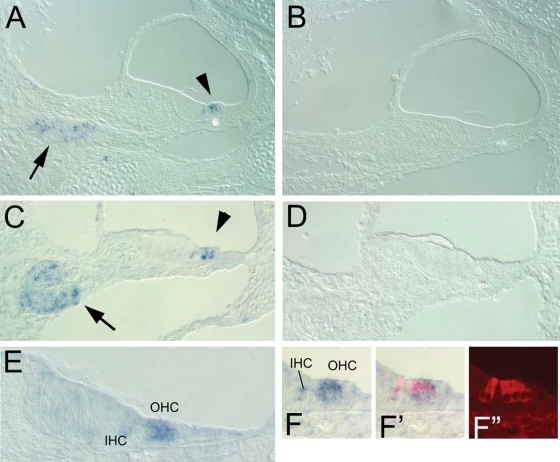

Figure 1.

Expression of Clrn1 in the mouse cochlea detected using in situ hybridization. (A and B) Antisense (A) and sense (B) probes used to localize Clrn1 at E18 in the middle turn. (C and D) Antisense (C) and sense (D) probes used to localize Clrn1 at P3 in the middle turn. Arrows point to the expression in the spiral ganglion, while arrowheads point to expression in the hair cells. (E and F–F′) Expression of Clrn1 in hair cells was confirmed at E18 by post-in situ antibody labeling with anti-myosin VI. (F′, F′′) Clarin1 is expressed more highly in the outer hair cells (OHC) than in the inner hair cells (IHC).

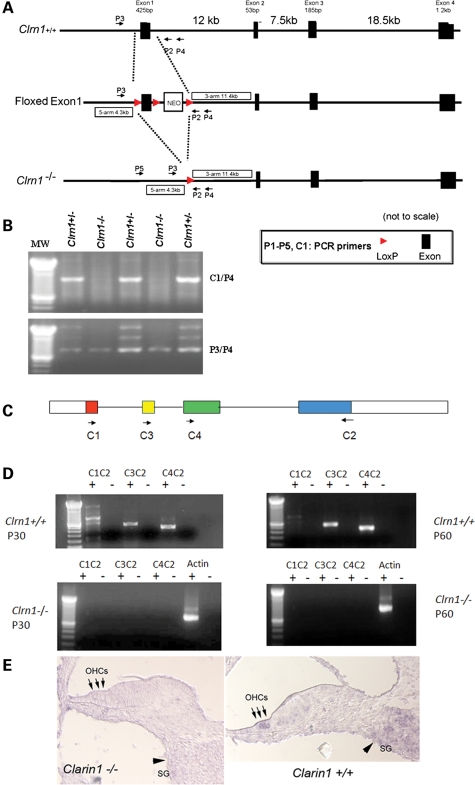

Figure 3.

Generation Clrn1 transgenic knockout. (A) Map of the targeted exon, targeting construct and excision of exon 1 after exposure to cre recombinase. (B) PCR-based genotyping to identify mice heterozygous (+/−) or homozygous (−/−) for the KO allele. PCR products amplified using C1/P4 or P3/P4 primers resolved on agarose gel. (C) Exon-intron map of Clrn-1 and location of RT–PCR primers. (D) RT–PCR analysis of Clrn-1 expression in wild-type and KO cochlea at P30 and 60. (E) shows in situ hybridization of Clrn1 mRNA in wild-type or Clrn1−/− mouse cochlea. Antisense probe used to localize Clrn1 in the middle turn of the cochlea at P1. Arrows point to the expression in the outer hair cells (OHCs), while arrowheads point to expression in the spiral ganglion (SG) cells. Clrn1 expression is absent in the KO mouse.

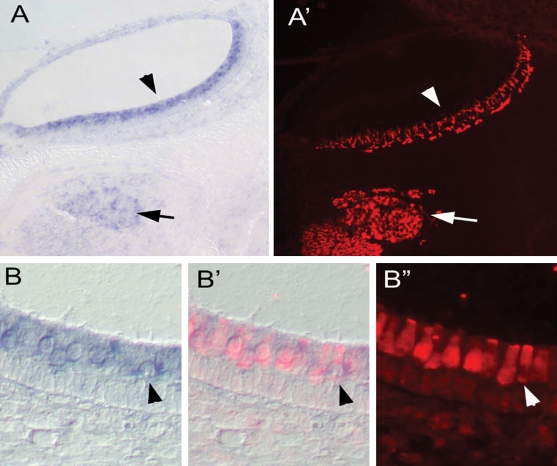

Figure 2.

Expression of Clrn1 in the mouse saccule detected using in situ hybridization. (A and A′) Clrn1 is expressed in vestibular hair cells (arrowhead) and ganglion neurons, as shown in (A′) using post-in situ immunolabeling with anti-TuJ1 antibody (arrow). (B and B′) Higher magnification view of Clrn1 expression in vestibular hair cells co-labeled with myosin VI. (B′ and B′′) Arrowhead points to an example of a double-labeled cell.

Generation of Clrn1−/− mice

To study the function of Clrn1, a transgenic mouse lacking the first coding exon (exon 1) of this gene was produced by homologous recombination (Fig. 3A and B). Normal Mendelian segregation of the Clrn1 exon 1 deleted allele (wild-type Clrn1+/+, heterozygous Clrn1+/− and homozygous Clrn1−/−) was observed. Lack of Clrn1 expression in the inner ears of Clrn1−/− mice was confirmed by RT–PCR at various time points from birth well into adulthood (P0–P60) (data from time points P30 and P60 are shown in Fig. 3C and D). In situ hybridization of cochlear duct sections from Clrn1−/− mice confirmed absence of Clrn1 expression in hair cells and SGCs (Fig. 3E). These results demonstrate that Clrn1 mRNA is not expressed in the inner ear of the Clrn1−/− mouse.

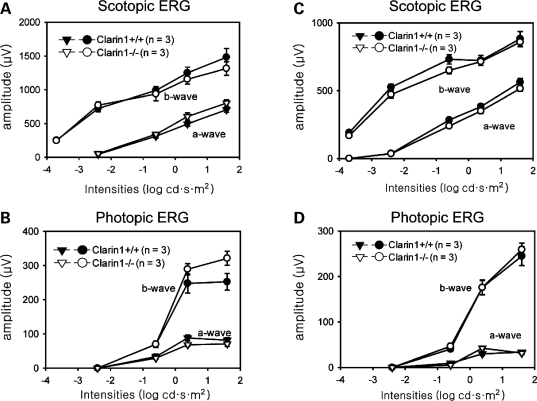

We also confirmed the lack of full-length Clrn1 expression in the retina of the Clrn1−/− mouse (data not shown). In Clrn1−/− mice, though, we failed to discover the deficiencies in structural abnormality of photoreceptors and other neurons at the age of 4 months (data not shown). Furthermore, electroretinograms (ERG) analyses did not reveal the sign of photoreceptor degeneration up to the age of 16 months, as exemplified by the lack of significant differences in the a-wave amplitudes at various light conditions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

ERG responses of Clrn1−/− mouse. (A and B) ERG responses of 8-month-old mice. (C and D) ERG responses of 16-month-old mice. Under both scotopic and photopic conditions, there were no significant differences in ERG responses between Clrn1−/− and Clrn1+/+ mice.

Clrn1−/− mice show progressive hearing loss

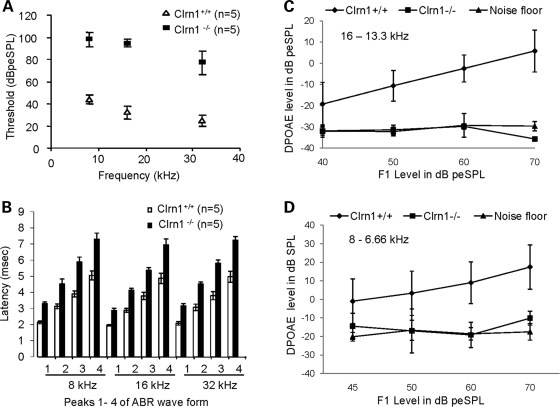

To assess hearing function in Clrn1−/− mice, we performed auditory brainstem response (ABR) tests on mice of different ages starting at P21, the age at which the auditory system in mice becomes fully mature. ABR tests reflect the electrical responses of both the cochlear ganglion neurons and the nuclei of the central auditory pathway to sound stimulation. About ∼30% of Clrn1−/− mice showed elevated ABR thresholds (Fig. 5A), but the majority (∼70%) failed to produce detectable ABR responses at P21. As expected, Clrn1+/+ littermates produced characteristic ABR waveforms (peaks 1–4) at thresholds from 25 to 45 dB peSPL (decibel peak equivalent Sound Pressure Level) for pure tones 8– 32 kHz (Fig. 5A); Clrn1+/− mice showed similar results (data not shown). Interestingly, in the recordings from mutant mice, response peak latencies were significantly prolonged compared with controls for all four peaks. For example, at 8 kHz the initial response peak (peak 1) occurred at ∼2.0 ms in Clrn1+/+ mice, but it was close to 3 ms in the Clrn1−/− mice (Fig. 5B). The interpeak latencies P1–P2 and P1–P3 were also prolonged in the mutants compared with control siblings (Table 1). By P30, hearing function was not detectable in any Clrn1−/− mice tested (data not shown). These results suggest that Clrn1−/− mice have some auditory function at young ages but lose it rapidly after P21. This prompted us to test mutants at time points earlier than P21. All of six Clrn1−/− mice tested at P14 and P20 showed some hearing function; however, thresholds were significantly elevated and peak latencies prolonged (Table 2). The increased intensity of sound needed to elicit a response from mutant ears at P14–21 suggests diminished hair cell function early in the life of Clrn1−/− mice and the prolonged P1 latency implies a delay in neural activation.

Figure 5.

Assessment of hearing impairment in Clrn1−/− mice at P21. ABR: (A) shows that the mean ABR thresholds Clrn1−/− mice are significantly elevated compared with Clrn1+/+ mice at 8, 16 and 32 kHz. (B) shows significant delay in latency of peaks 1–4 in Clrn1−/− mice compared with Clrn1+/+ mice at 8, 16 and 32 kHz. DPOAE: Assessment of OHC functions in Clrn1−/− mice. (C and D) Represent input/output (I/O) function test: the input at F1 (x-axis) plotted against the output, represented as mean (and mean ± SD) DPOAE levels (y-axis), at two pairs of frequency: 16–13.3 and 8–6.6 kHz. For I/O test, data were averaged from five Clrn1+/+ and five Clrn1−/− mice; results were compared with noise floor average from five trials (n = 5).

Table 1.

Peak latencies and interpeak latencies of ABR response for Clrn1+/+ and Clrn1−/− shown earlier (Fig. 5A and B). Absolute and interpeak latencies (measured in ms) were calculated for threshold levels (i.e. 0 dB sensation level). n = 5 for each genotype. Data in this table were generated in the laboratory of KA at CWRU

| ABR latencies at P21 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peaks | 8 kHz |

16 kHz |

32 kHz |

|||

| Clrn1+/+ | Clrn1−/− | Clrn1+/+ | Clrn1−/− | Clrn1+/+ | Clrn1−/− | |

| 1 | 2.14 ± 0.09 | 3.3 ± 0.10 | 1.96 ± 0.05 | 2.87 ± 0.14 | 2.08 ± 0.11 | 3.16 ± 0.15 |

| 2 | 3.13 ± 0.15 | 4.52 ± 0.31 | 2.89 ± 0.12 | 4.13 ± 0.12 | 3.07 ± 0.20 | 4.52 ± 0.13 |

| 3 | 3.9 ± 0.19 | 5.88 ± 0.31 | 3.78 ± 0.23 | 5.37 ± 0.16 | 3.79 ± 0.25 | 5.8 ± 0.21 |

| 4 | 5.05 ± 0.28 | 7.3 ± 0.38 | 4.87 ± 0.32 | 6.95 ± 0.36 | 4.97 ± 0.34 | 7.24 ± 0.22 |

| P1–P2a | 0.99 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.36. |

| P1–P3a | 1.77 | 2.58 | 1.82 | 2.50 | 1.71 | 2.64 |

aLatencies and interpeak latencies in ms.

Table 2.

ABR and VsEP response parameters for Clrn1+/+ and Clrn1−/− mice tested at various ages. Thresholds were measured in dB peSPL for ABR and dB re: 1.0 g/ms for VsEP. Latency was measured in ms and amplitude in µV at equal sensation levels (12 dBSL for ABR and 9 dBSL for VsEPs). The number in parentheses indicates the number of animals tested for each measure. Data in this table were generated in the laboratory of SMJ at ECU

| Parameter | Age | ABR (8 kHz) |

VsEP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clrn1+/+ | Clrn1−/− | Clrn1+/+ | Clrn1−/− | ||

| Threshold | 14 days | 42.2 ± 8.4 (4) | 76.5 ± 6.1 (6) | a | −4.50 (1) |

| 20 days | 41.0 ± 8.5 (2) | 77.0 ± 5.0 (6) | −10.50 ± 0.00 (2) | −5.36 ± 4.49 (7) | |

| 25 days | a | NA (10)b | −10.50 ± 0.00 (3) | −3.50 ± 4.58 (3)c | |

| 30 days | 33.6 ± 1.2 (4) | NA (10)b | −11.50 ± 1.73 (3) | −6.50 ± 1.73 (3)c | |

| P1 latency | 14 days | 2.04 ± 0.08 (4) | 3.26 ± 0.11 (6) | a | 1.73 (1) |

| 20 days | 2.21 ± 0.10 (2) | 3.26 ± 0.18 (6) | 1.48 ± 0.12 (2) | 1.64 ± 0.15 (7) | |

| 25 days | b | NRa | 1.40 ± 0.06 (3) | 1.64 ± 0.04 (3)c | |

| 30 days | NR | 1.36 ± 0.05 (3) | 1.63 ± 0.07 (3)c | ||

| P1-N1 | 14 days | 3.16 ± 1.23 (4) | 1.27 ± 0.24 (6) | a | 0.66 (1) |

| Amplitude | 20 days | 0.96 ± 0.07 (2) | 0.70 ± 0.11 (4) | 0.76 ± 0.43 (2) | 0.54 ± 0.07 (7) |

| 25 days | a | NR | 0.44 ± 0.14 (3) | 0.46 ± 0.12 (3) | |

| 30 days | NR | 0.87 ± 0.30 (3) | 0.43 ± 0.08 (3)c | ||

| IPL P1–P2 | 20 days | 0.96 ± 0.01 (2) | 1.07 ± 0.06 (2) | 0.74 ± 0.11 (2) | 1.11 ± 0.28 (5) |

| IPL P1–P3 | 20 days | 2.02 ± 0.01 (2) | 2.23 ± 0.11 (2) | 1.76 ± 0.14 (2) | Insufficient data |

IPL,interpeak latencies. anot recorded; bNo ABR at 100 dB peSPL; csignificantly different (P < 0.05).

Loss of OHC function in Clrn1−/− mice

To determine whether the hearing impairment in Clrn1−/− mice specifically involved an OHC defect, we recorded distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) which are indicative of OHC amplification activity. At P21, Clrn1−/− mice produced no detectable DPOAEs above the noise floor (NF) (Fig. 5C and D). Although, more than 10 Clrn1−/− mice with high threshold ABR, similar to those tested in Figure 5A and B, were tested at P21, we were unable to record any DPOAEs from these mutants. In contrast, wild-type controls showed normal DPOAE responses (Fig. 5C and D). Absence of DPOAEs at a very young age clearly indicates lack of OHC function in Clrn1−/− mice.

In summary, our hearing assessments are consistent with a cochlear lesion site and a sensorineural hearing loss. Further, auditory results show that Clrn1−/− mutation affects hair cell function, and either hair cell to afferent nerve communication or primary afferent neural activation.

Clrn1−/− mice show progressive loss of balance function

In Clrn1−/− mice, balance function was not overtly/severely affected by P30. In contrast, circling and head bobbing activity in the Usher 1F model is evident as early as P12 and becomes more obvious with age (9,10). The head bobbing phenotype in Clrn1−/− mice is mild and variable at young ages (P21–40) with some mutants indistinguishable from their wild-type siblings. However, vestibular dysfunction became more apparent with age such that some Clrn1−/− mice evidenced clearer signs of head bobbing than others by 6 months of age. Young adult (P21–P90) mutants were subjected to swim tests along with controls. Generally, Clrn1−/− mice appeared less stable in the water compared with controls (Clrn1+/+ or Clrn1+/−), tending to roll from one side to the other, even though they used their tails effectively to remain prone in the water. But abnormal swimming behavior was not discernable in all tested Clrn1−/− mice which prompted us to quantify vestibular function in these knockout (KO) animals.

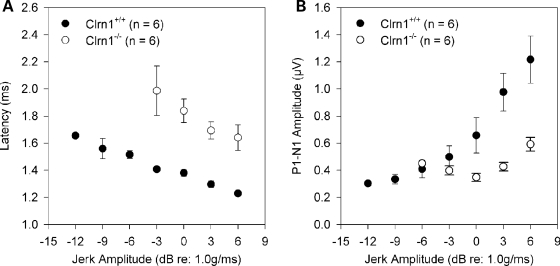

To quantitatively examine vestibular function in Clrn1−/− mice, we recorded vestibular evoked potentials (VsEP) of Clrn1−/− and Clrn1+/+ mice at P21–P30. It should be noted that VsEP recordings with linear stimulation specifically assess the otoconial organs (utricle and saccule). On average, VsEP thresholds of Clrn1−/− mice (−5.5 ± 3.6 dB re: 1.0 g/ms) were significantly higher than those of Clrn1+/+ controls (−11.0 ± 1.2 dB re: 1.0 g/ms), although the Clrn1−/− mice showed greater variability in their response thresholds (t = −3.5, P = 0.012). Some Clrn1−/− mice had normal VsEP thresholds, but all evidenced abnormalities in response peak latencies (Fig. 6A). P1 peak latencies were significantly prolonged (t = 2.26, P = 0.00003) (Fig. 6B and Table 2).

Figure 6.

VsEP recordings in Clrn1+/+ and Clrn1−/− mice. Mean P1 latencies (A) and peak-to-peak amplitudes for P1-N1 (B) as a function of increasing levels of jerk. P1-N1 is generated by the peripheral vestibular nerve. Clrn1−/− animals showed significantly prolonged latencies and significantly reduced amplitudes compared with Clrn+/+ animals. Error bars represent SEM.

In short, albeit more gradually apparent, the overall characteristics of the vestibular phenotype are similar to those observed in the auditory system of the Clrn1−/− mice, thus confirming that the organ of Corti and the saccular and utricular sensory receptors of the inner ear are affected. This strengthens our conclusion that disabling mutations in Clrn1 affect hair cell function and either hair cell to afferent nerve communication or primary afferent neural activation. However, no significant change in the vestibular hair cell morphology was observed within P21–30 (data not shown). Changes in the vestibular system tend to progress much more slowly than in the cochlea as noted above. Therefore, it will be necessary to examine older (>P30) Clrn1−/− mice carefully before we come to any conclusion about the effect of Clrn1 mutation on vestibular hair cells morphology.

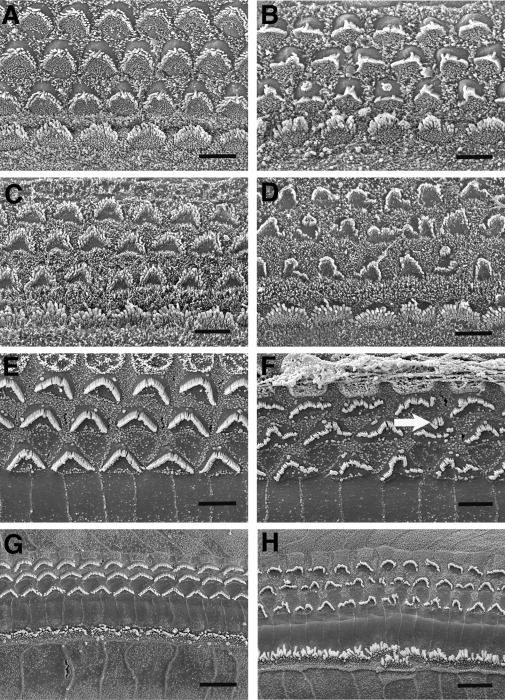

The stereocilia of OHCs are defective in Clrn1−/− mice

To better understand the structure–function relationship in Clrn1−/− mice, we examined organs of Corti from young animals by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Stereocilia display a ‘V’ shaped configuration on the OHCs and a crescent shaped configuration on the IHCs in normal mice by P10. There were obvious abnormalities in the arrangement of stereocilia in Clrn1−/− mice as compared to controls as early as P2 (Fig. 7A and B). Abnormalities similar to those observed at P2 were also noted in OHC stereocilia at P6 (Fig. 7C and D). By P10, the derangement of the stereocilia was more apparent compared with the well organized, mature stereocilia bundles typically observed in the control specimen at P10 (Fig. 7E and F). In addition to general disorganization of the bundles, circular clusters of abnormal stereocilia were also seen on some OHC (Fig. 7F). Stereocilia defects of the same type and approximate severity also were present at P15 and the basal and upper cochlear turns appeared to be similarly affected (Fig. 7G and H). There was little progression in the severity of stereocilia defects during the period from P2 to P15, suggesting that progression of this pathology is relatively slow during that interval. In all cases, the stereocilia of IHCs appeared normal or only mildly affected. The severity of stereocilia defects in OHCs varied among Clrn1−/− mice, consistent with the variable severity of hearing loss in different animals.

Figure 7.

Scanning electron micrographs showing surface views of the organ of Corti in Clrn1+/+ and Clrn1−/− mice aged P2 through P15. Relative to Clrn+/+ (shown in left column) the OHCs from the Clrn1−/− animals (right column) show abnormally arranged stereocilia. (A and B) P2; (C and D) P6; (E and F) P10; (G and H) P15. All micrographs taken from basal cochlear turn, expect (G and H) which show mid-basal and lower apical turns, respectively. The arrow in (F) indicates a circular cluster of stereocilia (a feature occasionally seen on OHC in the mutants). Scale bars in (A–F) indicate 5 µm; scales bars in (G) and (H) indicate 10 µm.

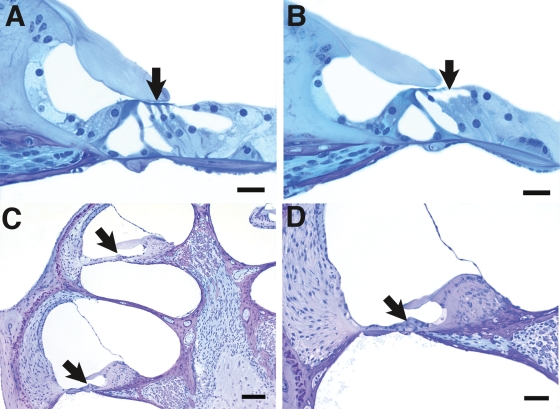

Disabling mutation in Clrn1 leads to cochlear hair cell death

The rapidly progressive hearing loss observed in Clrn1−/− mice suggests that degeneration of cochlear hair cells may occur at a relatively early age. Accordingly, the cochleas of Clrn1−/− and control mice were examined in histological cross sections at P21 and P30. In cochlear cross sections, loss of OHCs was apparent by P21 in Clrn1−/− mice as compared to wild-type specimens (Fig. 8A and B). By P30, almost all OHCs and IHCs were missing throughout most of the cochlea in Clrn1−/− mice (Fig. 8C and D), whereas these hair cells were well maintained in wild-type mice. The supporting cells were also degenerated in the basal turn, leading to collapse of the organ of Corti.

Figure 8.

Light micrographs showing cochlear cross sections from animals at P21 (A and B) and P30 (C and D). The P21 wild-type specimen (A) shows three rows of OHCs (arrow); however, in the mutant (B), the second and third row OHCs are missing (area indicated by arrow). At P30 all cochlear structures appear normal with the exception of the organ of Corti (arrows in C), which is undergoing degeneration in both the apical and basal turns. (D) Higher power view from the basal turn area at lower left in (A) demonstrating degeneration and collapse of the organ of Corti (arrow). Scales bars in (A and B) indicate 20 µm bars in (C and D) indicate 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

The use of gene knockout technology in the mouse is a powerful approach for study of diseases such as USH3A. One of the most common mutations in USH3A patients is the Y176X mutation in CLRN1. The premature stop codon present in Y176X would result in a small truncated protein that is most likely functionally inactive or null. Therefore, we hypothesized that the inner ear phenotype in Clrn1-null mouse would be similar to the clinical presentation of patients harboring the Y176X mutation. Our results show that Clrn1−/− mice display early onset hearing loss that rapidly progresses to a profound loss by ∼P30. In contrast, vestibular dysfunction was relatively mild in young animals, progressing slowly (relative to hearing loss) to a severe deficit with age. The overall inner ear phenotype in the Clrn1−/− mouse is similar to the inner ear dysfunction observed in USH3A patients with a presumptive null mutation in CLRN1. As with other Usher mouse models, we failed to detect any obvious retinal dysfunctions in Clrn1−/− mouse. Therefore, the KO mouse reported here should be a good model for the ear disease occurring in human USH3A patients.

Clrn1−/− mice showed early onset (P14–21) hearing loss with elevated ABR thresholds of 85–95 dB peSPL. In addition, the absolute latencies of all ABR waves and the interpeak latencies between the waves were significantly delayed, suggesting a neural deficit in addition to a hair cell function deficiency. In the vestibular apparatus, gravity receptor function declined more gradually, but the overall profile was in agreement with the cochlear phenotype. Similar to the delayed latency in ABR peaks, prolonged VsEP peak latencies were observed in all Clrn1−/− mice tested, suggesting a defect in gravity receptor hair cell function and associated neural activation. Prolonged peak latencies seen in Clrn1−/− mice are reminiscent of mutants with demyelinating disorders (11,12). These findings suggest that the auditory and vestibular deficits in Clrn1−/− mice are caused by peripheral defects that affect sensory transduction, the communication of hair cells with afferent neurons and/or signal propagation along the eighth nerve. It has been predicted that CLRN1 might play a role in ribbon synapses based on sequence similarities between the CLRN1-specific motif and stargazin, a cerebellum synapse protein (4). The expression of Clrn1 in hair cells and the functional deficits observed in Clrn1−/− mice support a possible role for CLRN1 in ribbon synapses. The progressive deterioration in cochlear and vestibular function observed in Clrn1−/− mice is reminiscent of the clinical ear disorder in USH3A (13,14).

In situ mRNA hybridization results confirm the specific expression of Clrn1 in hair cells and ganglion cells of the cochlea and saccule as early as E16.5 and indicate that this expression continues during the postnatal period. While stereocilia bundle morphogenesis is still underway at E16.5 (15), this timing also coincides with the onset of mechanotransduction in embryonic hair cells of mice (16). In the cochlea, mRNA in situ hybridization shows stronger expression of Clrn1 in OHCs as compared to IHCs, suggesting a more dominant role for clarin-1 in the OHC, consistent with the fact that DPOAEs are absent in hearing Clrn1−/− mice. SEM studies also provide strong support for early onset OHC defects in Clrn1−/− mice. Our results indicate that the auditory phenotype is caused at least in part by hair cell defects and that Clrn1 is required during hair cell development.

Distinct features of the inner ear phenotype in Clrn1−/− mice as compared to the phenotype reported in Usher type I and II mouse models suggests a novel inner ear function for CLRN1. Mouse mutants harboring presumptive null mutations in Usher type I genes exhibit severe disorganization of stereocilia during the early stages of IHC and OHC development (17–19), and the progression of stereocilia pathology from P0 to P15 is quite rapid, as exemplified in Usher type 1F models (20,21). In contrast, mice carrying a null mutation in Clrn1 display relatively less severe stereocilial defects on OHCs in all turns of the cochlea at early postnatal stages, but the progression of severity seems slow from P2 to P15; the stereocilial defects in IHCs are barely detectable at these ages. This is consistent with the hearing loss phenotype of Clrn1−/− mice: ∼30% of these mutants still have detectable hearing (85–90 dB peSPL) at young ages (P14–21), while Usher type 1 mutants display profound hearing loss at birth. In addition, Usher type 1 mutants show early (P10–P15) onset head bobbing and circling behavior, while young (P21–P30) Clrn1−/− mice exhibit only mild defects, in most cases requiring VsEP recordings to confirm vestibular dysfunction. Mice carrying mutations in the Usher 2a (usherin) gene show hearing loss only at high frequencies and slightly elevated DPOAEs at high frequencies. Concomitantly, usherin mutant mice show hair cell loss only in the basal turn of the cochlea (22). In contrast, mice carrying mutations in the Usher 2d (whirlin) gene are deaf and the stereocilia are stunted (23). Usher 2C (Vlgr1-mutated) mice carrying targeted deletion of Vlgr1 are deaf by P21 and stereocilia bundles become disorganized soon after birth (24). Evidence from the recent literature suggests that most, if not all, Usher proteins interact with each other at some level to ultimately mediate their effects on function in hair cell and photoreceptor cell development and function (3,17,25). Evidence in the literature also suggests possible linkage between CLRN1 and Myosin VIIa (Usher 1B gene product). USH3A patients with a single mutant allele of Usher1B exhibits USH1 phenotype (26). Myosin VIIa has been previously reported to interact with other proteins, including Usher type I proteins (reviewed in 17). Harmonin (Usher 1C) is predicted to interact with Usher type I and type II gene products via the PDZ domain and to serve as PDZ domain-based scaffolds to anchor Usher proteins to F-actin (27,28). A link between Usher gene products and actin-based organelles also has been established in vivo (reviewed in 17). In this report we show that the F-actin-enriched stereocilia of cochlear hair cells are abnormal in the Clrn1−/− mice. Regulation and homeostasis of actin filaments is a fundamental process affecting various developmental and functional processes in a multicellular organism. Therefore, one possible molecular mechanism for the observed phenotype in Clrn1−/− mice might be linked to defective organization/function of actin filaments in the hair cells and neuronal cells. We plan to test this hypothesis in future experiments.

In conclusion, the Clrn1−/− mouse reported here provides a useful model for inner ear dysfunction in USH3A and to understand the function of CLRN1 in the hair cells and associated neurons. Disabling mutations in Clrn1 causes clear structural defects in OHCs and affects IHC and OHC function. Prolonged peak latencies in vestibular and cochlear evoked potentials strongly suggest that Clrn1 is necessary for normal sensory transduction, hair cell to afferent communication and/or primary afferent neural activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic targeting of the Clrn1 gene

A Clrn1 KO mouse was generated by IngenKO, Pty. Ltd. (Clayton, Victoria, Australia). Briefly, the targeting construct was produced by using the ET cloning system (29) with C57BL/6J genomic DNA. The construct was designed such that loxP sites flanked part of the Clrn1 upstream promoter, the 5′-UTR, the coding part of the first exon (exon 1), 269 bp of the first intron and a neomycin resistance gene (NeoR). Standard protocol was used to generate cre-mediated targeted deletion of exon 1. The targeting construct was subsequently electroporated into C57BL/6J embryonic stem (ES) cells and recombinant clones were selected using G418. Selected clones were transfected with Cre recombinase and screened by PCR for removal of the Clrn1 gene fragment noted above. Recombined ES cells were microinjected into BALB/c blastocysts and implanted into pseudo-pregnant mothers. Chimeric progeny were obtained, and highly chimeric animals were subsequently mated with C57BL/6J mice to identify germ-line transmission of the Clrn1 deletion. Founder animals were identified, and heterozygous progeny were delivered to the University of California, Berkeley (UCB). Clrn1−/− mice derived from mating Clrn1+/− mice were sent to Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) for further evaluation. The new allele described in this report was maintained by crossing it to the C57BL/6J (B6) strain, which was used in all parts of this study. The Animal Care and Use Committee at CWRU approved the care and use of the mice included in this investigation.

Genotyping

A PCR-based protocol was used to identify Clrn1+/+, Clrn1+/− and Clrn1−/− mice. Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse tails by using the Qiagen DNaeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. The primers used for genotyping were C1: 5′-TTTACCGAAGCCTTTTCTCG-3′; P3: 5′-GGAGTAAGAAGTAGTCAACGG-3′; and P4: 5′-GCATTTCTCAGCAGATCAC. PCR was carried out at an annealing temperature of 55°C for 35 cycles. PCR products were resolved in 1.5% agarose gels. The genotypes of Clrn1+/+, Clrn1+/− and Clrn1−/− mice were distinguished by PCR (Fig. 3B). In PCR reactions with P3/P4 primers, only a 782 bp band was detected in KO mice, while a 2 kb band was the only band present in Clrn1+/+ mice; the genotype was further confirmed by PCR with C1/P4 primers. Since the C1 primer sequence is located in the first exon, a 1 kb band present in samples from Clrn1+/+ and Clrn1+/− was not detected in Clrn1−/− mice.

Anatomical analyses

For morphological studies of the sequence of postnatal degenerative changes occurring in the inner ears of Clrn1−/− mutants, mice were examined at each of five time points (2, 5, 10, 20 and 30 days of age). Five Clrn1−/− mice plus at least two Clrn1+/− controls per time point were processed for histological analysis. In all cases, inner ear tissues were processed using standard procedure (10).

Methods used for SEM have been described elsewhere (20,21). Clrn1−/− mice with age-matched control specimens (heterozygous littermates) were studied by SEM at each of four time points (P2, P5, P10 and P15).

Electroretinograms

ERGs were recorded as described previously (30).

Auditory-evoked brain stem responses

ABR recording was conducted as previously described (31). To test hearing function, Clrn1−/− mice were presented with broadband clicks or pure tone stimuli at 8, 16 or 32 kHz. Clrn1+/+ [number (n) of animals with this genotype tested = 20], Clrn1+/− (n = 10) and Clrn1−/− (n = 60) mice were analyzed. Click stimuli of 100 µs duration were presented for at least 500 sweeps to both the left and right ears (one at a time) through high frequency transducers (a closed system). ABR thresholds were reported as dB peSPL (identifies how the transient tone burst stimuli were calibrated) were obtained from both ears for each animal by reducing the stimulus intensity from 100 dB peSPL in 10 dB steps; this sequence was repeated in 5 dB steps until the lowest intensity that evoked a reproducible ABR pattern was detected.

DPOAE measurements

The basic protocol used for DPOAE recording has been described elsewhere (32,33). The main functional measure used in this study was the 2f1–f2 DPOAE. Briefly, the f1 and f2 primary tones were generated by a synthesizer [Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT, FL)] and attenuated under computer control by using TDT software. The f1 and f2 primaries (f1/f2 = 1.2) were then presented over two separate transducers with a 10 dB difference in intensity, f1 being 10 dB higher than f2, and delivered to the outer ear canal through an acoustic probe (Etymotic Research, ER-10B+, Elk Grove Village, IL), where they were allowed to acoustically mix. Ear-canal sound pressure levels were measured by the ER-10B+ emissions microphone assembly embedded in the probe. Corresponding NFs were computed by averaging the levels of the ear-canal sound pressure for five frequency bins above and below the 2f1–f2 DPOAE frequency bin (i.e. ±54 Hz). DPOAEs, considered present when they were at least 3 dB above the NF, are represented as input/output (I/O) functions: the input at the f1 level (x-axis) is plotted against the output, represented as the mean (±SD) DPOAE levels (y-axis), at these two frequency pairs, i.e. 16–13.3 and 8–6.6 kHz. For I/O testing, data were averaged from 5+/+ and 5−/− mice; results then were compared with the averaged NF from five trials (n = 5).

Vestibular evoked potentials

The use of animals for VsEPs was approved at East Carolina University. Mice were anesthetized with a ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) solution and core body temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.1°C with a homoeothermic heating blanket system (FHC, Inc.). Recording electrodes were placed subcutaneously at the nuchal crest (non-inverting), the pinna (inverting) and the hip (ground). VsEPs were obtained at P14 (WT, n = 4; KO, n = 1), P21 (WT, n = 2; KO, n = 7), P25 (KO, n = 3; WT, n = 3), P30 (KO, n = 3; WT, n = 3) and at 3–6 months of age (KO, n = 3). VsEP recording procedures followed methods described previously (34–36). Here we used a non-invasive spring clip to couple the head to a voltage-controlled mechanical shaker that delivered stimuli to the head. Linear acceleration pulses (2 ms duration, 17 pulses/s) were presented to the cranium in the naso-occipital axis by using two stimulus polarities, normal (upward) and inverted (initial downward movement). Stimulus amplitude ranged from +6 to −18 dB re: 1.0 g/ms (where 1.0 g = 9.8 m/s2) adjusted in 3 dB steps. Ongoing electroencephalographic activity was amplified (200 000×), filtered (300–3000 Hz, −6 dB amplitude points) and digitized (1024 points, 10 µs/point). Primary responses (256) were averaged and replicated for each VsEP waveform. VsEP recordings began at the maximum stimulus intensity (i.e. +6 dB re: 1.0 g/ms) with and without acoustic masking (broadband forward masker 50–50 000 Hz at 97 dB SPL), then the intensity was dropped to −18 dB and subsequently raised in 3 dB steps to complete an intensity profile. The masker was used to verify the absence of auditory components in the VsEP waveform. The first three positive and negative response peaks were scored. Peak latencies (measured in ms), peak-to-peak amplitudes (measured in µV) and thresholds (measured in dB re: 1.0 g/ms) were quantified. Descriptive statistics were generated and the independent samples t-test (assuming unequal variances) was used to compare VsEP response parameters between Clrn1−/− and Clrn1+/+ mice.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

RT–PCR was used to screen for Clrn1 mRNA in the inner ears of the Clrn1−/− and Clrn1+/+ mice. RT–PCR protocol was carried out as described previously (9). RT–PCR was used to amplify various exon combinations of Clrn1 (Fig. 3D). Primers used for this work were C1: 5′-TTTACCGAAGCCTTTTCTCG-3′; C2: 5′-TATGGACTTCCTTTGGCCAC-3′; C3: 5′- AGGTACTCTCTGTATGAGGACAA -3′; C4: 5′- TCTTCTCCATGATTCTTGTCGTCT-3′. The following PCR conditions were used: 94°C for 2 min followed by 34 cycles of 30 s each, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min. All PCR products were resolved on 3% low range ultra agarose gels (BIO-RAD) and stained with 5% ethidium bromide. Three bands of the following sizes were expected: 834, 780 and 650 bp. Sequences of RT–PCR products were determined with BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing reagents and protocols (Applied Biosystems, CA). The ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) was used to analyze and display the resulting sequence data.

In situ hybridization

Animals were housed in the Department of Comparative Medicine at the University of Washington and were euthanized according to approved protocols. Timed pregnant female mice were sacrificed and embryos removed at E16.5 and E18.5. Embryos were fixed in a modified Carnoy's solution (60% ethanol:4% formaldehyde:10% acetic acid) overnight at 4°C. Specimens were washed and dehydrated in 100% ethanol overnight at 4°C and then embedded in paraffin; 6 mm sections were subsequently cut and collected. For the postnatal mice, we assigned the day of birth as postnatal day 0 (P0) and sacrificed pups at P0, P3 and P5, according to approved protocols. We then dissected the cochleas from these animals, fixed them and processed them for paraffin sectioning as described above. At least three animals were examined for each time point. Mouse Clrn1 cDNA (clone ID: 40130533) was obtained from Open Biosystems Inc. A full-length clone containing exons 1 and 4 with 3′ and 5′-UTRs was used as the template to generate Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes, which were prepared according to the manufacturer's manual for DIG-11-UTP (Roche, Indianapolis, IN); hybridizations were then carried out according to Hayashi et al. (37). In situ products were visualized by using anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody (Roche) and the NBT/ BCIP liquid substrate system (Sigma, St Louis, MO). After in situ hybridization, slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h and washed in PBS. Slides then were incubated with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2% non-fat dry milk in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 30 min. After overnight incubation with the primary antibody [rabbit anti-Myosin6 (Myo6, Proteus Biosystems)] at 1:2000 dilution, or rabbit anti β-tubulin III (TuJ1, Covance, Austin, TX) at 1:1000 dilution, slides were washed and incubated in fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody, rinsed with PBST and cover-slipped in Fluoromount G (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Images were captured by a Zeiss Axioplan microscope with a SPOT CCD camera and processed by using Adobe Photoshop.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

R.G., T.H., C.R., T.A.R., O.B.-McD., S.M.J., C.G.W. and K.N.A. contributed in experimental design, experiments and data analysis; S.M. performed DPOAE data analysis; Y.I. and K.P. research design; S.F.G. and J.G.F. designed and generated the clarin-1 knockout mouse; R.G. and K.N.A. wrote the paper.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Hope for Vision Foundation to K.N.A., Y.I., J.G.F., O.B.-McD. and T.R. and by National Institutes of Health R01 DC006443 to S.M.J.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the technical support provided by Daniel Chen in K.N.A's laboratory. We thank Dr Kermany of the Center for Hearing & Deafness, U. Buffalo for technical support with DPOAE recordings and analysis. We thank Brian McDermott for critically reviewing the manuscript. We would like thank Guilian Tian (YI's lab) and Tadao Maeda in the Ophthalmology department, CWRU, for technical support with ERG analysis.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Petit C. Usher syndrome: from genetics to pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2001;2:271–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremer H., van Wijk E., Marker T., Wolfrum U., Roepman R. Usher syndrome: molecular links of pathogenesis, proteins and pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15(Spec no. 2):R262–R270. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiners J., Nagel-Wolfrum K., Jurgens K., Marker T., Wolfrum U. Molecular basis of human Usher syndrome: deciphering the meshes of the Usher protein network provides insights into the pathomechanisms of the Usher disease. Exp. Eye. Res. 2006;83:97–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adato A., Vreugde S., Joensuu T., Avidan N., Hamalainen R., Belenkiy O., Olender T., Bonne-Tamir B., Ben-Asher E., Espinos C., et al. USH3A transcripts encode clarin-1, a four-transmembrane-domain protein with a possible role in sensory synapses. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;10:339–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemler M.E. Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion, and fusion events and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2003;19:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.153609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemler M.E. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:801–811. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubner K., Windoffer R., Hutter H., Leube R.E. Tetraspan vesicle membrane proteins: synthesis, subcellular localization, and functional properties. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2002;214:103–159. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)14004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L., Chetkovich D.M., Petralia R.S., Sweeney N.T., Kawasaki Y., Wenthold R.J., Bredt D.S., Nicoll R.A. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alagramam K.N., Murcia C.L., Kwon H.Y., Pawlowski K.S., Wright C.G., Woychik R.P. The mouse Ames waltzer hearing-loss mutant is caused by mutation of Pcdh15, a novel protocadherin gene. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:99–102. doi: 10.1038/83837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alagramam K.N., Zahorsky-Reeves J., Wright C.G., Pawlowski K.S., Erway L.C., Stubbs L., Woychik R.P. Neuroepithelial defects of the inner ear in a new allele of the mouse mutation Ames waltzer. Hear. Res. 2000;148:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou R., Assouline J.G., Abbas P.J., Messing A., Gantz B.J. Anatomical and physiological measures of auditory system in mice with peripheral myelin deficiency. Hear. Res. 1995;88:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00104-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones S.M., Johnson K.R., Yu H., Erway L.C., Alagramam K.N., Pollak N., Jones T.A. A quantitative survey of gravity receptor function in mutant mouse strains. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2005;6:297–310. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennings R.J., Fields R.R., Huygen P.L., Deutman A.F., Kimberling W.J., Cremers C.W. Usher syndrome type III can mimic other types of Usher syndrome. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2003;112:525–530. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness S.L., Ben-Yosef T., Bar-Lev A., Madeo A.C., Brewer C.C., Avraham K.B., Kornreich R., Desnick R.J., Willner J.P., Friedman T.B., et al. Genetic homogeneity and phenotypic variability among Ashkenazi Jews with Usher syndrome type III. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:767–772. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.10.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayak G.D., Ratnayaka H.S., Goodyear R.J., Richardson G.P. Development of the hair bundle and mechanotransduction. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2007;51:597–608. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072392gn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geleoc G.S., Risner J.R., Holt J.R. Developmental acquisition of voltage-dependent conductances and sensory signaling in hair cells of the embryonic mouse inner ear. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:11148–11159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2662-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown S.D., Hardisty-Hughes R.E., Mburu P. Quiet as a mouse: dissecting the molecular and genetic basis of hearing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:277–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Amraoui A., Petit C. Usher I syndrome: unravelling the mechanisms that underlie the cohesion of the growing hair bundle in inner ear sensory cells. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4593–4603. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefevre G., Michel V., Weil D., Lepelletier L., Bizard E., Wolfrum U., Hardelin J.P., Petit C. A core cochlear phenotype in USH1 mouse mutants implicates fibrous links of the hair bundle in its cohesion, orientation and differential growth. Development. 2008;135:1427–1437. doi: 10.1242/dev.012922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikkawa Y.S., Pawlowski K.S., Wright C.G., Alagramam K.N. Development of outer hair cells in Ames waltzer mice: mutation in protocadherin 15 affects development of cuticular plate and associated structures. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 2008;291:224–232. doi: 10.1002/ar.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pawlowski K.S., Kikkawa Y.S., Wright C.G., Alagramam K.N. Progression of inner ear pathology in Ames waltzer mice and the role of protocadherin 15 in hair cell development. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2006;7:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10162-005-0024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X., Bulgakov O.V., Darrow K.N., Pawlyk B., Adamian M., Liberman M.C., Li T. Usherin is required for maintenance of retinal photoreceptors and normal development of cochlear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4413–4418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610950104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mburu P., Mustapha M., Varela A., Weil D., El-Amraoui A., Holme R.H., Rump A., Hardisty R.E., Blanchard S., Coimbra R.S., et al. Defects in whirlin, a PDZ domain molecule involved in stereocilia elongation, cause deafness in the whirler mouse and families with DFNB31. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:421–428. doi: 10.1038/ng1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGee J., Goodyear R.J., McMillan D.R., Stauffer E.A., Holt J.R., Locke K.G., Birch D.G., Legan P.K., White P.C., Walsh E.J., et al. The very large G-protein-coupled receptor VLGR1: a component of the ankle link complex required for the normal development of auditory hair bundles. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6543–6553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0693-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maerker T., van Wijk E., Overlack N., Kersten F.F., McGee J., Goldmann T., Sehn E., Roepman R., Walsh E.J., Kremer H., et al. A novel Usher protein network at the periciliary reloading point between molecular transport machineries in vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:71–86. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adato A., Kalinski H., Weil D., Chaib H., Korostishevsky M., Bonne-Tamir B. Possible interaction between USH1B and USH3 gene products as implied by apparent digenic deafness inheritance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:261–265. doi: 10.1086/302438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boeda B., El-Amraoui A., Bahloul A., Goodyear R., Daviet L., Blanchard S., Perfettini I., Fath K.R., Shorte S., Reiners J., et al. Myosin VIIa, harmonin and cadherin 23, three Usher I gene products that cooperate to shape the sensory hair cell bundle. Embo J. 2002;21:6689–6699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adato A., Michel V., Kikkawa Y., Reiners J., Alagramam K.N., Weil D., Yonekawa H., Wolfrum U., El-Amraoui A., Petit C. Interactions in the network of Usher syndrome type 1 proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:347–356. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angrand P.O., Daigle N., van der Hoeven F., Scholer H.R., Stewart A.F. Simplified generation of targeting constructs using ET recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda A., Maeda T., Imanishi Y., Kuksa V., Alekseev A., Bronson J.D., Zhang H., Zhu L., Sun W., Saperstein D.A., et al. Role of photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase in the retinoid cycle in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18822–18832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501757200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Megerian C.A., Semaan M.T., Aftab S., Kisley L.B., Zheng Q.Y., Pawlowski K.S., Wright C.G., Alagramam K.N. A mouse model with postnatal endolymphatic hydrops and hearing loss. Hear. Res. 2008;237:90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez A.M., Stagner B.B., Martin G.K., Lonsbury-Martin B.L. Age-related loss of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in four mouse strains. Hear. Res. 1999;138:91–105. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin G.K., Vazquez A.E., Jimenez A.M., Stagner B.B., Howard M.A., Lonsbury-Martin B.L. Comparison of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in 28 inbred strains of mice. Hear. Res. 2007;234:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones S.M., Erway L.C., Johnson K.R., Yu H., Jones T.A. Gravity receptor function in mice with graded otoconial deficiencies. Hear. Res. 2004;191:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones T.A., Jones S.M. Short latency compound action potentials from mammalian gravity receptor organs. Hear. Res. 1999;136:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones S.M., Subramanian G., Avniel W., Guo Y., Burkard R.F., Jones T.A. Stimulus and recording variables and their effects on mammalian vestibular evoked potentials. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2002;118:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayashi T., Cunningham D., Bermingham-McDonogh O. Loss of Fgfr3 leads to excess hair cell development in the mouse organ of Corti. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:525–533. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]