Abstract

Introduction

Inorganic mercury poisoning is uncommon, but when it occurs it can result in severe, life-threatening features and acute renal failure. Previous reports on the use of extracorporeal procedures such as haemodialysis and haemoperfusion have shown no significant removal of mercury. We report here the successful use of the chelating agent 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate (DMPS), together with continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF), in a patient with severe inorganic mercury poisoning.

Case report

A 40-year-old man presented with haematemesis after ingestion of 1 g mercuric sulphate and rapidly deteriorated in the emergency department, requiring intubation and ventilation. His initial blood mercury was 15 580 μg/l. At 4.5 hours after ingestion he was started on DMPS. He rapidly developed acute renal failure and so he was started on CVVHDF for renal support and in an attempt to improve mercury clearance; CVVHDF was continued for 14 days.

Methods

Regular ultradialysate and pre- and post-filtrate blood samples were taken and in addition all ultradialysate generated was collected to determine its mercury content.

Results

The total amount of mercury in the ultrafiltrate was 127 mg (12.7% of the ingested dose). The sieving coefficient ranged from 0.13 at 30-hours to 0.02 at 210-hours after ingestion. He developed no neurological features and was discharged from hospital on day 50. Five months after discharge from hospital he remained asymptomatic, with normal creatinine clearance.

Discussion

We describe a patient with severe inorganic mercury poisoning in whom full recovery occurred with the early use of the chelating agent DMPS and CVVHDF. There was removal of a significant amount of mercury by CVVHDF.

Conclusion

We feel that CVVHDF should be considered in patients with inorganic mercury poisoning, particularly those who develop acute renal failure, together with meticulous supportive care and adequate doses of chelation therapy with DMPS.

Keywords: 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate; DMPS; haemodiafiltration; inorganic mercury; mercuric sulphate; poisoning; toxicokinetics

Introduction

Ingestion of inorganic mercury compounds can result in severe toxicity, and blood mercury concentrations in excess of 220 μg/l are associated with severe clinical effects [1]. Fatalities have been reported after ingestion of 0.5 g by an adult, with a mean lethal adult dose of 1–4 g [1]. Inorganic mercury causes toxicity by two mechanisms. First, mercuric ions precipitate proteins that cause direct necrosis on contact with tissues; this occurs in the mouth, stomach, large bowel and kidney [2]. Mercuric ions accumulate in the kidneys (accounting for 85–90% of the body burden) [1], causing acute renal failure due to necrosis of the proximal tubular epithelium, usually within 24 hours [2]. Second, inorganic mercury complexes with a number of ligands, particularly sulphydryl groups, causing inhibition of enzymes and protein transport mechanisms [2]. This causes a metabolic acidosis and, in the early phases of toxicity, it can cause death due to metabolic acidosis, vasodilatation and shock.

Previously, dimercaprol (British anti-Lewsite [BAL]) was the chelating agent of choice for inorganic mercury poisoning. It is lipophilic and is given by intramuscular injection formulated in peanut oil. It mobilizes tissue mercury by forming soluble complexes, which are excreted in the urine [3]. In the anuric patient these complexes accumulate, resulting in increased toxicity of both BAL and mercury. The chelating agent of choice for inorganic mercury poisoning is now 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate (DMPS), which is much better tolerated and results in greater mercury excretion [4].

We describe here a case of severe poisoning due to mercuric sulphate, which was treated successfully with a combination of DMPS and high-flux continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) with no neurological or renal sequelae. Data are also presented describing the toxicokinetics of the mercuric salt and its clearance by CVVHDF.

Case report

A 40-year-old man ingested approximately 1000 mg mercuric sulphate powder (obtained from his place of work) in a deliberate suicide attempt. He presented to the emergency department of his local hospital 2 hours after ingestion complaining of a 'burning sensation' in his throat. He had a 10-year history of depression and alcohol abuse, and had taken an overdose of temazepam in the past. There was no other medical history and he was on no regular medication.

His heart rate was 120 beats/min, his blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg and his respiratory rate was 30 breaths/min. Initial blood tests, 3 hours after ingestion, revealed the following (arterial blood gases taken on air): arterial oxygen tension 10.8 kPa, arterial carbon dioxide tension 5.0 kPa, pH 7.27, base excess -9.0 mmol/l. His blood chemistry and indices were as follows: plasma sodium 145 mmol/l, potassium 6.2 mmol/l, urea 6.1 mmol/l, creatinine 166 μmol/l, haemoglobin 14.3 g/dl, white cell count 10.0 × 109/l and platelet count 327 × 109/l. His initial blood mercury concentration was 15 580 μg/l.

Soon after presentation to the emergency department, he had a large haematemesis and developed stridor and respiratory distress, requiring intubation and ventilation. His pharynx and epiglottis were oedematous and haemorrhagic on laryngoscopy.

After telephone contact by physicians at the initial hospital with the National Poisons Information Service, he started treatment with DMPS. The first dose (250 mg) was given approximately 4.5 hours after ingestion. He was transferred to Guy's Hospital intensive care unit (ICU) for management under the joint care of the clinical toxicologists and ICU physicians. He received DMPS at a dose of 250 mg intravenously every 4 hours for the first 4 days. On day 4 he developed an erythematous maculopapular rash with blistering over his lower legs. Because this was felt to be due to DMPS [4], the dose was cut to 250 mg every 8 hours and he developed no further blistering. He remained on this dose until day 10, when the DMPS regimen was changed to the oral form at a dose of 200 mg/day for a further 9 days.

He was anuric by 12 hours after ingestion. In view of the acute renal failure and the possibility of removal of mercury and/or mercury–DMPS complex, he was commenced on high-flux bicarbonate-buffered CVVHDF at 7 hours after ingestion. CVVHDF was performed at a blood flow rate of 150 ml/min using a polyacrylonitrile hollow-fiber 0.9 cm2 filter (Hospal AN69-Multiflow100; Hospal Cobe, Rugby, UK). Fluid replacement was administered postfilter using Haemosol-XG0/LG4 (Hospal Cobe) together with a variable dose, continuous infusion of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate. To achieve high-flux haemodiafiltration, these fluids were used as the dialysis fluid infused counter-current at 2 l/hour in addition to continuing haemofiltration at 2.5 l/hour. He remained anuric until day 11 and oliguric (urine output <1 ml/kg per hour) from days 12 to 43. He remained on CVVHDF until day 14 and subsequently required eight sessions of haemodialysis for renal support on days 16, 19, 22, 25, 29, 31, 34 and 37.

He had a further episode of haematemesis on day 9; upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (oesophagogastroduodenoscopy) showed confluent gastritis and two gastric ulcers with adherent clot, which were injected with adrenaline (epinephrine). He was transfused 15 U blood over the first 11 days (clotting studies remained normal). He was commenced on intravenous pantoprazole (40 mg twice daily) and nasogastric sucralfate (1 g three times daily) and had no further gastrointestinal bleeding.

He developed no focal neurological symptoms or signs at any stage during his admission, in particular no tremor or fasciculation. He remained cardiovascularly stable without the need for circulatory support with inotropes or vasoconstrictors. He was extubated on day 8 and discharged from the ICU to a general medical ward on day 14. He was reviewed by the liaison psychiatry team on the ward.

When he was discharged from hospital on day 50, he was asymptomatic, with a blood mercury of 32 μg/l and serum creatinine of 185 μmol/l.

When reviewed in the medical outpatients department 5 months after discharge from hospital, he was asymptomatic and psychologically stable. His blood mercury was 5 μg/L, urine mercury 7 μg/L, serum creatinine 74 μmol/l and creatinine clearance 114 ml/min. He had a normal follow-up oesophagogastroduodenoscopy performed 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Methods of toxicokinetic modelling and calculation of mercuric sulphate clearance

Every 6 hours, samples were taken of ultradialysate and from the prefiltrate and postfiltrate arms of the extracorporeal circuit (frequent sampling did not begin until 24 hours after ingestion). In addition, all ultradialysate generated was collected to determine its mercury content; these samples and the blood samples were analyzed using cold vapour atomic absorption (Cetac M-6000; Cetac Technologies, Omaha, NE, USA).

Blood concentrations of mercuric sulphate were analyzed using the nonlinear regression package WinNonlin (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). Data were fitted using a constant variance weighting scheme, and one-, two-and three-compartment models were fitted to the data and compared. These models had the general form:

![]()

Where Ct is the concentration at time t, Ci and λi represent the parameters to be estimated, and i = 1, 2 and 3 for one-, two- and three-compartment models, respectively. The models were compared using the general linear test (significance set at P < 0.05) and by examination of the standard errors of the parameter estimates.

Filter clearance was determined using the excretion rate as follows:

Filter clearance = UDHg/(CHg × Δt)

Where UDHg is the amount of mercury in the ultradialysate and CHg is the mean mercury concentration during the time period (Δt) over which the ultradialysate bag was collected.

Sieving coefficients were calculated from the following:

Sieving coefficient = 2 × Chfd/(Cpre + Cpost)

Where Chfd is the mercury concentration in the ultrafiltrate (plus dialysate), and Cpre and Cpost are the mercury concentrations in the prefiltrate and postfiltrate arms of the extracorporeal circuit, respectively. Although sieving coefficients are strictly only applicable under haemofiltration, they are included here to illustrate mercury distribution across the membrane.

Results of the toxicokinetic modelling and clearance data

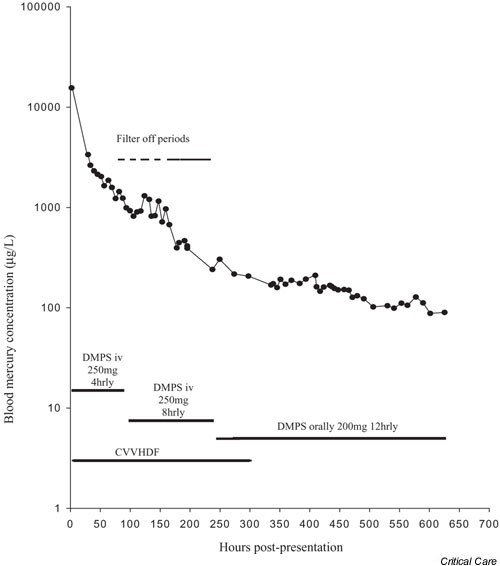

Whole blood mercury fell rapidly during the first 30 hours after ingestion, from 15 580 μg/l on admission (2.5 hours after ingestion) to 3370 μg/l 27.5 hours later. Fig. 1 shows the full concentration–time profile, including periods of CVVHDF and doses of DMPS, and the fit obtained using a three-compartment model. This model fitted the data best when all of the data points were included (although the error on the terminal rate constant was high, at 51%). When the first data point was excluded, the two-compartment model was satisfactory. Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates from these models are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Blood concentrations of mercury (μg/l) versus time. Also shown are doses of 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate (DMPS) and timing of continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF), including filter-off periods. iv, intravenous.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates and precentage coefficients of variation obtained from the blood concentration–time data

| Estimated parameters | Derived parameters (assuming an ingested dose of 1000 mg mercuric sulphate) ingested dose of 1000 mg mercuric sulphate) | |||||||||||

| Data set | C1a (μg/l) | λ 1a (/h) | C2a (μg/l) | λ 2a (/h) | C3a (μg/l) | λ 3a (/h) | Clearance (l/h) | Vssb x(l) | λ1 t1/2c (h) | λ2 t1/2c (h) | λ3 t1/2d (h) | |

| All data | Parameter estimate | 15.2 | 0.105 | 3.18 | 0.0121 | 0.273 | 0.0016 | 1.74 | 381 | 6.60 | 57.2 | 425 |

| % cvee | 25 | 28 | 14 | 15 | 47 | 51.3 | 9.14 | 37.5 | 28.5 | 15.3 | 51.2 | |

| Data minus first point | Parameter estimate | 3.66 | 0.0139 | 0.318 | 0.0019 | 2.33 | 572 | 50.0 | 362 | |||

| % cve | 10.2 | 10.7 | 32.3 | 32.4 | 4.98 | 23.1 | 10.6 | 32.3 | ||||

a Concentration at t hours after dose (see Eqn 1 in text); C1, C2 and C3 are the coefficients associated with the ith exponent and λ1, λ2 and λ3 represent the distribution and elimination rate constants. bVss is the volume of distribution at steady state. cDistribution half-lives. dElimination half-life. ePercentage coefficient of variation of the parameter estimate.

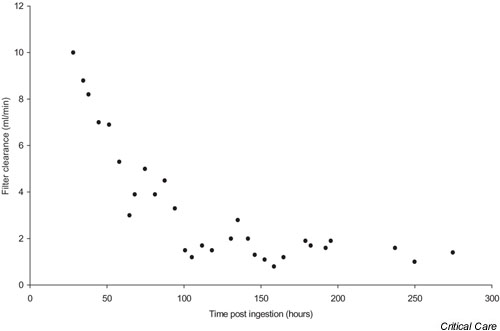

The total amount of mercury in the ultrafiltrate was 127 mg, which represented 12.7% of the ingested dose of approximately 1000 mg. A total of 90% (114.2 mg) was removed during the first three days of CVVHDF. The sieving coefficient ranged from 0.13 at 30 hours to 0.02 at 210 hours after ingestion. Filter clearance estimates fell from 10 ml/min at early time points to 1.6 ml/min 100 hours after ingestion (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mercury filter clearance estimates plotted against time.

Discussion

We present a case of potentially severe mercuric sulphate poisoning in which the expected renal and neurological sequelae were avoided. The initial blood mercury concentration is the highest recorded level in the literature that has been associated with a favourable outcome. (There is one report of a patient with a blood mercury of 22 000 μg/l who died soon after presentation to hospital [5].)

When all of the blood concentration data were included in the pharmacokinetic analysis, a three-compartment model provided the best fit of the data, with estimates of half-lives of 6.6 and 57 hours for the initial and distribution phases, and 17.7 days for the terminal elimination phase. A potential problem with the interpretation of these data is that DMPS and CVVHDF were started between the first and second blood mercury samples. The initial rapid decline may have been due to an early distribution phase; however, an additional influence of DMPS cannot be excluded.

When the first data point was excluded from the analysis, the best fit was obtained using a two-compartment model, with the first phase having a half-life of 50 hours and the second phase 15 days. Elimination of mercury appeared to decrease after day 10, and there are a number of different explanations for this. First, DMPS dosing was changed from 250 mg intravenously every 8 hours to 200 mg orally every 12 hours. Because the oral bioavailability of DMPS is 50% [6], this dose change represented a two-thirds reduction in the DMPS load. Second, CVVHDF was discontinued around this time and renal support was continued with haemodialysis, which would be expected to achieve a lower clearance of mercury [7-12]. Another possibility is that this slow phase may reflect a low rate of transfer of mercury between compartments, or a change in the binding of mercury to protein fractions such as metallothionein [13].

The usual elimination half-life of inorganic mercury ranges from 30 to 100 days [2]. A case report of inorganic mercury poisoning (with an initial blood mercury of 14 300 μg/l), treated with DMPS and haemodialysis, reported bi-exponential elimination with half-lives of 2.5 and 8.1-days [14], which are similar to those reported here. In two further cases of inorganic mercury poisoning in patients with normal renal function, treatment with DMPS decreased elimination half-life from 30 to 11 days [15]. This is consistent with our value for the second phase, suggesting that CVVHDF had minimal effects in enhancing elimination at this stage. However, because sampling only continued until 26 days after ingestion, it is possible that we did not fully characterize the terminal elimination phase.

During the early phase of CVVHDF filter clearance was estimated to be 10 ml/min, which is higher than has previously been reported. Overall, CVVHDF removed 12.7% of the ingested dose. There have been previous reports of the use of BAL with haemodialysis [7-12], dimercaptosuccinic acid with haemodialysis [8], BAL with peritoneal dialysis [16,17], DMPS with haemodialysis [14], BAL with haemoperfusion [12,18], and BAL/DMPS with plasma exchange, haemodialysis and haemofiltration [19]. Most of those reports showed no significant removal of mercury by the extracorporeal device [7-9,11,12,14,16]. The highest previously documented clearances were 4.7 ml/min with the combination of BAL and haemodialysis [10], 2.4 ml/min with the combination of BAL and peritoneal dialysis [17], and 4.24 ml/min with the combination of BAL and plasma exchange [19]. However, in both of the latter two reports, less than 1% of the ingested dose was removed by peritoneal dialysis/plasma exchange, which would not be expected to have a significant clinical impact.

The diafilter used in this patient allows passage of molecules with molecular weights of up to 30 kDa, which greatly exceeds the size of the mercury–DMPS complex (mercuric sulphate 297 Da and DMPS 188 Da). However, protein binding and distribution volume are more important determinants of flux across the filter. Inorganic mercury is highly (>99%) protein bound [18]. In addition, although the pharmacokinetics of DMPS in the presence of inorganic mercury have not been well described, it appears likely that the DMPS–mercury complex would behave like the metabolized form of DMPS, which has variable but high protein binding and distribution [6]. Unfortunately, we were unable to assay DMPS in the dialysate and so are unable to tell whether the cleared mercury was free mercury or DMPS–mercuric complex. The above kinetic data explain, in part, why mercury elimination by CVVHDF (whether free mercury or DMPS–mercuric complex) was limited to 12.7% and not higher.

Conclusion

We present a case of severe mercuric sulphate poisoning with an initial blood concentration of 15 580 μg/l. The patient was treated with DMPS and high-flux CVVHDF. Mercuric sulphate was eliminated by CVVHDF, contributing to the removal of 12.7% of the ingested dose, mainly over the first 72 hours. We feel that this is clinically beneficial in patients with severe inorganic mercury intoxication and that CVVHDF should be considered in patients with inorganic mercury poisoning, particularly those who develop acute renal failure, together with meticulous supportive care and adequate doses of chelation therapy with DMPS.

Competing interests

None declared.

Key messages

• Inorganic mercury poisoning is uncommon but when it does occur it can result in severe life-threatening features and acute renal failure

• We present a case of ingestion of 1 g of mercuric sulphate, with an initial blood mercury of 15580 μg/l, the highest recorded level that has been associated with survival

• Treatment with DMPS and CVVHDF resulted in removal of 12.7% of the ingested dose by CVVHDF

• The patient developed acute renal failure but no neurological features – at follow up 6 months later he had no long-term sequelae

• DMPS is the chelating agent of choice and CVVHDF should be considered in all patients with inorganic mercury poisoning, particularly those who develop acute renal failure

Abbreviations

BAL = British anti-Lewsite (dimercaprol); CVVHDF = continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration; DMPS = 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate; ICU = intensive care unit.

References

- Gosselin RE, Smith RE, Hodge HC. Mercury. In: Gosselin RE, Smith RE, Hodge HC, editor. In Clinical Toxicology of Commercial Products. 5. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1984. pp. 262–275. [Google Scholar]

- Winship KA. Toxicity of mercury and its inorganic salts. Adv Drug React Ac Pois Rev. 1985;3:129–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabard B. The excretion and distribution of inorganic mercury in the rat as influenced by several chelating agents. Arch Toxicol. 1976;35:15–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00333982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby K, Donner A. 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulphonate in heavy metal poisoning. Med Toxicol. 1987;2:317–323. doi: 10.1007/BF03259951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wineck CL. Fatal mercuric chloride poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1981;18:261–266. doi: 10.3109/15563658108990034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut KM, Maiorino RM, Mayersohn M, Dart RC, Bruce DC, Aposhian HV. Determination and metabolism of dithiol chelating agents. XVI: pharmacokinetics of 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulphonate after intravenous administration to human volunteers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:662–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worth DP, Davison AM, Lewins AM, Ledgerwood MJ, Taylor A. Haemodialysis and charcoal haemoperfusion in acute inorganic mercury poisoning. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:636–638. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.60.707.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyniak PJ, Greizerstein HB, Goldstein J, Lachaal M, Reddy P, Clarkson TW, Walshe J, Cunningham E. Extracorporeal regional complexing hemodialysis treatment of acute inorganic mercury intoxication. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1990;9:137–141. doi: 10.1177/096032719000900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels ER, Heick HMC, McLaine P, Farant JP. A case of inorganic mercury poisoning. J Anal Toxicol. 1982;6:120–122. doi: 10.1093/jat/6.3.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leumann EP, Brandernberger H. Hemodialysis in a patient with acute mercuric cyanide intoxication. Concentrations of mercury in blood, dialysate, urine, vomitus and faeces. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1977;11:301–308. doi: 10.3109/15563657708989844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton JA, House IM, Volans GN, Goodwin FJ. Plasma mercury during prolonged acute renal failure after mercuric chloride ingestion. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1983;3:535–537. doi: 10.1177/096032718300200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelline TJ, Karjalainen K, Haapanen EJ. Haemoperfusion in mercury poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1983;20:187–189. doi: 10.3109/15563658308990064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg M, Nordberg GM. Toxicological aspects of metallothionein. Cell Mol Biol. 2000;46:451–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toet AE, van Dijk A, Savelkoul TJF, Meulenbelt J. Mercury kinetics in a case of severe mercuric chloride poisoning treated with dimercapto-1-propanesulphonate (DMPS). Hum Exp Toxicol. 1994;13:11–16. doi: 10.1177/096032719401300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JR, Clarkson TW, Omar MD. The therapeutic use of 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulphonate in two cases of inorganic mercury poisoning. JAMA. 1986;256:3127–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn A, Denis R, Blum D. Accidental ingestion of mercuric sulphate in a 4 year old child. Clin Pediatr. 1977;16:956–958. doi: 10.1177/000992287701601015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal DT, Chardo F, Reidenberg MM. Removal of mercury by peritoneal dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller F, Koeppel C, von Keyserling HJ, Schultze G. Haemoperfusion for organic mercury detoxication? Klin Wochenschr. 1981;59:865–866. doi: 10.1007/BF01721058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlan GA. Acute mercury poisoning. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:110–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]