Abstract

Background and Aims

In sexual hybrids between cultivated Brassica species and another crucifer, Orychophragmus violaceus (2n = 24), parental genome separation during mitosis and meiosis is under genetic control but this phenomenon varies depending upon the Brassica species. To further investigate the mechanisms involved in parental genome separation, complex hybrids between synthetic Brassica allohexaploids (2n = 54, AABBCC) from three sources and O. violaceus were obtained and characterized.

Methods

Genomic in situ hybridization, amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) were used to explore chromosomal/genomic components and rRNA gene expression of the complex hybrids and their progenies.

Key Results

Complex hybrids with variable fertility exhibited phenotypes that were different from the female allohexaploids and expressed some traits from O. violaceus. These hybrids were mixoploids (2n = 34–46) and retained partial complements of allohexaploids, including whole chromosomes of the A and B genomes and some of the C genome but no intact O. violaceus chromosomes; AFLP bands specific for O. violaceus, novel for two parents and absent in hexaploids were detected. The complex hybrids produced progenies with chromosomes/genomic complements biased to B. juncea (2n = 36, AABB) and novel B. juncea lines with two genomes of different origins. The expression of rRNA genes from B. nigra was revealed in all allohexaploids and complex hybrids, showing that the hierarchy of nucleolar dominance (B. nigra, BB > B. rapa, AA > B. oleracea, CC) in Brassica allotetraploids was still valid in these plants.

Conclusions

The chromosomes of three genomes in these synthetic Brassica allohexaploids showed different genome-specific stabilities (B > A > C) under induction of alien chromosome elimination in crosses with O. violaceus, which was possibly affected by nucleolar dominance.

Key words: Synthetic Brassica allohexaploids, Orychophragmus violaceus, intergeneric hybrids, genomic in situ hybridization, amplified fragment length polymorphism, single-strand conformation polymorphism, chromosome elimination, chromosome stability, nucleolar dominance

INTRODUCTION

Polyploidy has played a major role in the evolution of higher plants, and about 70 % of all angiosperms have experienced one or more events of polyploidization during the course of their evolution (Levin, 2002). Allopolyploids, which maintain the genomes from two or more parental species, are frequent in nature, fertile, well adapted and genetically stable. However, synthetic or neo-allopolyploids commonly display phenotypic and genetic instability, low fertility and low embryonic viability (Comai, 2000; Comai et al., 2000; Chen, 2007). These instabilities are presumably eliminated by evolutionary adaptations giving rise to stable species (Comai, 2000). Studies on polyploids immediately following their synthesis have revealed genetic and epigenetic interactions between redundant genes. These interactions can be related to the phenotypic and evolutionary fates of polyploids (Comai, 2005). Gene sequence changes result from rapid genomic rearrangements, rapid sequence elimination or movement of genetic elements, while gene expression changes across genomes are attributable to the sequence changes, DNA methylation, histone modifications and antisense RNA, illustrating the complex dynamics of polyploid genomes after their emergence (for reviews see Comai, 2000; Liu and Wendel, 2002; Chen and Ni, 2006; Chen, 2007; Paun et al., 2007; Hegarty and Hiscock, 2008; Doyle et al., 2008; Leitch and Leitch, 2008).

Brassica napus (2n = 38, AACC), a young allopolyploid species resulting from multiple independent hybridization events between ancestors of the modern diploid B. oleracea (2n = 18, CC) and B. rapa (2n = 20, AA), may provide an ideal model to observe chromosomal changes from homoeologous recombination, because it is now largely accepted that the diploid progenitors are widely replicated and closely related (Truco et al., 1996; Parkin et al., 2003, 2005; Lukens et al., 2004; Lysak et al., 2005). Molecular marker analysis of natural and resynthesized B. napus suggests that chromosomal rearrangements caused by homeologous recombination are widespread in this species and have effects on allelic and phenotypic diversity (Osborn et al., 2003b; Pires et al., 2004; Udall et al., 2005; Nicolas et al., 2007; Gaeta et al., 2007).

When genomes of different species are combined together within the cellular and nuclear environment of one of their parents, either as interspecific or intergeneric hybrids, they express various states of intergenomic conflict at chromosomal level, such as chromosome elimination in hybrids, spatial separation in stable F1 hybrids and instabilities in allopolyploids (see Comai, 2000; Jones and Pašakinskienè, 2005; Chen and Ni, 2006; Chen, 2007 for review; and also Comai et al., 2000; Osborn et al., 2003a). Uniparental chromosome elimination in hybrid cells has been demonstrated in hybrid cells of various organisms, including plants (Kasha and Kao, 1970; Bennett et al., 1976; Finch, 1983; Faure et al., 2002; Gernand et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2007; Du et al., 2008), insects (Breeuwer and Werren, 1990; Reed and Warren, 1995), hybrid fish (Fujiwara et al., 1997; Sakai et al., 2007) and mammalian cultured cells (Weiss and Green, 1967; Matsui et al., 2003). Cellular, chromosomal and molecular evidence have been obtained to explain different aspects of uniparental chromosome elimination, involving differences in the timing of essential mitotic processes as a result of asynchronous cell cycles (Gupta, 1969), formation of multipolar spindles (Subrahmanyam and Kasha, 1973), spatial separation of genomes during interphase (Finch and Bennett, 1983; Linde-Laursen and von Bothmer, 1999) and metaphase (Schwarzacher-Robinson et al., 1987), parent-specific inactivation of centromeres (Finch, 1983; Kim et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2004; Mochida et al., 2004), and lagging chromosomes at the metaphase/anaphase transition (Sakai et al., 2007), among others.

Ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) are the main structural components (about 60 %) of ribosomes and the expression of rRNA genes is tightly regulated to accommodate the cellular demand for ribosomes and protein synthesis (Pikaard, 2000). Thereby, rRNA genes perform perhaps the most basic of all housekeeping functions, and might also control important aspects of cell behaviour (Moss and Stefanovsky, 2002). Alteration in the structure, organization and activity of rDNA is probably one of the most defined genetic events associated with allopolyploid speciation (Skalická et al., 2003). In many interspecific hybrids and derived allopolyploids, rRNA genes inherited from one parent are transcribed and those from the other progenitor are silent. As a result, nucleoli, the sites of ribosome assembly, form at the chromosome loci where active rRNA genes are clustered (Pikaard, 2000). This epigenetic phenomenon, which was first described in plants more than 70 years ago (Navashin, 1934), is now best known as nucleolar dominance. A hierarchy of nucleolar dominance (B. nigra, BB > B. rapa, AA > B. oleracea, CC) has been demonstrated in three allotetraploid Brassica species (Chen and Pikaard, 1997; Pikaard, 2000). This phenomenon occurs in plants, insects, amphibians and mammals, although its biological function is not well understood.

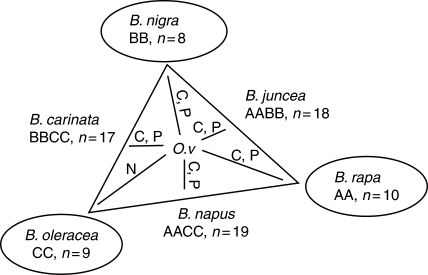

The crucifer Orychophragmus violaceus (L.) O.E.Schulz (2n = 24) is cultivated as an ornamental plant in China and has a high seed yield potential and desirable oil quality, thus making it a good source for genetic improvement of Brassica crops (Luo et al., 1994). There remain controversies regarding its phylogenetic position as its placement in the tribe Brassiceae has been questioned (Al-Shehbaz, 1985), but is supported by some molecular data (Warwick and Sauder, 2005). However, its phylogenetic position outside the tribe Brassiceae has recently been suggested again, based on the results from comparative chromosome painting which suggest that the species is a tetraploid taxon sharing the common ancestor of Brassiceae but lacking the tribe-specific genome triplication event (Lysak et al., 2007). Only hybrids with O. violaceus as pollen parent and six cultivated Brassica species in the ‘U triangle’ (U, 1935) have been obtained; reciprocal crosses proved unsuccessful. Except for B. oleracea × O. violaceus, all hybrids are mixoploids. The hybrids show separation of parental genomes during mitotic and meiotic divisions and chromosomes of O. violaceus are preferentially eliminated (Li et al., 1995, 1998; Li and Heneen, 1999; Hua et al., 2006). During mitosis, any of three situations may occur, and subsequently the chromosomes are doubled following chromosome duplications in daughter cells: (1) complete separation of parental genomes produces cells with haploid and diploid complements of the two parents; (2) partial separation leads to inclusion of some chromosomes of one parent with the haploid complement of the other, producing hypo- and hyperdiploid cells; and (3) during partial separation, chromosomes of either parent are included in the genomes, resulting in substitution lines. Additionally, chromosome behaviour varies in the hybrids depending upon the Brassica species and is considered to be under genetic control. The different chromosome behaviour of hybrids with three Brassica diploids might contribute to the different cytology of hybrids with three tetraploids. It is proposed that the B genome from B. nigra (L.) Koch (2n = 16, BB) accounts for complete and partial genome separation in hybrids with B. carinata A. Braun (2n = 34, BBCC); both the A genome from B. rapa and B genomes contribute to this separation in hybrids with B. juncea (L.) Czern & Coss (2n = 36, AABB); and the A genome is more influential than the C genome for the separation during mitosis and meiosis in hybrids with B. napus. Employing these hybridizations, it is feasible to produce Brassica aneuploids and haploids and subsequently homozygous lines (for a review see Li and Ge 2007; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Genomic relationships among the cultivated Brassica diploids and derived allotetraploids (U, 1935) and the chromosome behaviours in their hybrids with O. violaceus. C, P and N represent complete, partial and no genome separation, respectively, in the hybrids of O. violaceus with Brassica species. ‘O. v’ = O. violaceus. The hierarchy of rRNA gene transcriptional dominance in allotetraploids is B. nigra > B. rapa > B. oleracea (Chen and Pikaard, 1997) and is still valid in the hexaploids used in this study produced from three crosses: B. carinata × B. rapa, natural and synthetic B. napus × B. nigra.

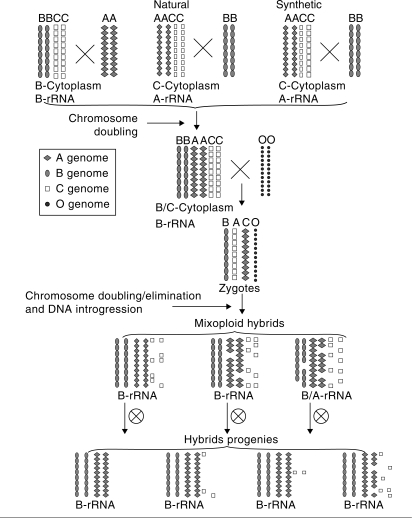

Because of the unique and interesting cytology documented in Brassica × Orychophragmus hybrids, it should be worthwhile to study chromosome behaviour in complex hybrids of O. violaceus with artificially synthesized Brassica allohexaploids (2n = 54, AABBCC) from different crossing approaches (Figs 1 and 2) and also to elucidate the mechanisms involved in parental genome separation. The present analyses at morphological and chromosomal/genomic levels show that these complex hybrids only contain partial complements of the allohexaploids but no intact chromosomes from O. violaceus, and furthermore that the chromosomes from the A and B genomes are preferentially maintained whereas those from the C genome are lost. The results suggest that the chromosomes in the allohexaploids have genome-specific stabilities under the induction of alien chromosome elimination. The B. nigra rRNA genes are still dominant in these allohexaploids and complex hybrids. The formation of these complex hybrids and possible correlations between nucleolar dominance and genome-specific chromosome stability are discussed.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustrations showing the formation of complex hybrids between synthesized Brassica allohexaploids from three combinations and O. violaceus, and the correlation between nucleolar dominance and chromosome stability. Symbols represent the chromosomes of the A (n = 10), B (n = 8), C (n = 9), O (n = 12) genomes, as indicated, and the arrangement orders of genomes (B–A–C) in Brassica tetra-/hexaploids indicate the hierarchy of nucleolar dominance. Chromosomal fragments detected by AFLP analysis in hybrids are not shown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials and crosses

Three types of Brassica allohexaploids (2n = 54, AABBCC) were developed from different crosses (Table 1), following embryo rescue and chromosome doubling (Fig. 2). All parental materials were from Huazhong Agricultural University. For chromosome doubling, young plantlets were treated on MS agar medium (Murashinge and Skoog, 1962) with 1·5 mg L−1 6-benzyl aminopurine (6-BA), 0·25 mg L−1 α-naphthalenacetic acid (NAA) and 100 mg L−1 colchicine for 10 d and then transferred onto the same MS agar medium without colchicine until plantlets were regenerated from callus. It is easy to obtain B. carinata × B. rapa hybrids, but quite difficult when B. napus was pollinated by B. nigra, particularly in those cases when synthetic B. napus was used. More regular meiotic pairing and segregation and higher pollen fertility were observed in hexaploid I (Table 2) and produced more progeny plants having the same chromosome number (2n = 54) as the hexaploid. The same trend of crossability was observed in these hexaploids × Orychophragmus violaceus (2n = 24) crosses, in which majority of complex hybrids (27/37) were produced from the cross with hexaploid I, although many fewer pollinations were made (Table 2). During flowering, the hexaploidy status was confirmed cytologically before the hexaploids were used as female parent in crosses with O. violaceus by means of hand emasculation and pollination. About 2–3 weeks after pollination, the immature embryos were cultured on MS medium. Five to ten F2 plants were obtained and studied from each complex hybrid from the cross with hexaploid I and 5–10 F3 plants from each F2 plant for cytological investigation. The F3 plants were selfed for two generations to obtain new B. juncea lines. For hexaploids II, III and their hybrids with O. violaceus that were self-incompatible, progenies were obtained by bud pollination.

Table 1.

Three types of hexaploids and their parents

| Hexaploid | Maternal parent | Paternal parent |

|---|---|---|

| I | B. carinata A. Braun (2n = 34, BBCC) (accession no. Go-7) | B. rapa L. (2n = 20, AA) ‘Shanghaiqing’ |

| II | Natural B. napus L. (2n = 38, AACC) ‘Zhongyou 821’ | B. nigra (L.) Koch (2n = 16, BB) ‘Giebra’ |

| III | Synthetic B. napus No. 7406-5 (B. oleracea var. alboglabra Bailey No. 4003 × B. rap var. yellow sarson K-151) (Chen et al. 1988), selfed for more than 10 generations | B. nigra (L.) Koch (2n = 16, BB) ‘Giebra’ |

Table 2.

Cytology of three Brassica allohexaploids and their crossability with Orychophragmus violaceus

| No. of PMCs with AI segregations (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexaploids | No. of PMCs with 27 bivalents (%) | 27 : 27 | 26 : 28 | 25 : 29 | 24 : 30 | Pollen stainability (%) | Progenies with 2n = 54 (%)* | No. of hybrids/flowers pollinated by O. violaceus |

| I | 78·8 | 79·4 | 14·7 | 5·9 | 0 | 84·7 | 33·3 | 30/407 |

| II | 65·7 | 57·3 | 21·3 | 14·7 | 6·7 | 72·4 | 0 | 4/1485 |

| III | 62·5 | 52·1 | 26·8 | 16·9 | 4·2 | 60·6 | 0 | 3/2044 |

* For Hexaploids II and III that are self-incompatible, progenies from open pollination were observed.

The leaves of young plants were collected for amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analyses. Somatic hybrids between B. napus ‘Huashuang no. 3’ and O. violaceus with the whole chromosome complements of two parents obtained in our laboratory and the BC1 plants with B. napus (Zhao et al., 2008) were used for rDNA expression and genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) analysis, respectively.

Pollen stainability and cytological methods

Pollen stainability was determined as the percentage of pollen grains stained with 1 % acetocarmine. Cytological studies were carried out as described by Li et al. (1995).

DNA extraction, probe labelling and GISH analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted and purified from young leaves according to Dellaporta et al. (1983). The DNA from B. nigra ‘Giebra’ and O. violaceus was labelled with Bio-11-dUTP (Sabc, Luoyang, China) or digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), by using the nick translation method, and was used as probe. The DNA of B. napus ‘Zhongyou 821’ was sheared by boiling for 15 min and used as a block. Slides of chromosomes for GISH were prepared mainly following the procedures of Zhong et al. (1996) with some modifications; an enzyme mixture containing 0·6 % cellulose Onozuka RS (Yakult, Tokyo, Japan), 0·2 % pectinase (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0·5 % Snailase (Beijing Baitai Biochem Co. Ltd, Beijing, China) was used. In situ hybridization was carried out according to the protocols of Leitch et al. (1994). Hybridization signals of B. nigra and O. violaceus probes were detected using Cy3-labelled streptavidin (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and anti-digoxigenin conjugate–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Roch, Basel, Switzerland), respectively. Signals from O. violaceus were amplified by anti-sheep conjugate FITC (Roch). Preparations were then counterstained with 4′-6-diamidino-2- phenylindole (DAPI) solution (1 µg mL−1; Roche), mounted in antifade solution (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and examined under a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a Leica 300F CCD. Images were processed by Adobe Photoshop 8·0 software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) to adjust contrast and brightness.

In control GISH of B. nigra chromosomes with a O. violaceus probe and vice versa, seeds of B. nigra ‘Griebra’ and O. violaceus were germinated on wet filter paper in a Petri dish and the root tips from 1–2-cm roots were pretreated with 2 mm 8-hydroxyquinoline for 2 h and fixed in 1 : 3 (v/v) acetic acid/ethanol for the chromosome preparations as above. The genomic DNA from B. nigra ‘Giebra’ and O. violaceus were labelled with Bio-11-dUTP (Sabc) and used as probe.

Amplified fragment length polymorphism

AFLP analysis was performed on F1 plants, their parents and progeny plants following the protocol of Vos et al. (1995) and DNA bands were visualized by silver staining (Bassam et al., 1991). EcoRI–MseI primers were randomly selected for fingerprint analyses; all intense and unambiguous bands from 80 to 800 bp were scored. The absence of haploid AFLP fragments in the AFLP profiles of complex hybrids was also scored. Data were analysed by hand to obtain averages of different types of AFLP fragments per primer. To determine the level of correlation between the novel bands and O. violaceus-specific bands in hybrids from crosses with hexaploid I, a t-test was performed.

RNA extraction, reverse transcriptase PCR and cDNA-SSCP analyses

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Each RNA sample was quantified by measuring 260/280-nm ratio using a UV-spectrometer and by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. RNAs were treated with Dnase I before reverse transcription using a DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Approximately 3 µg total RNA was used for first-strand synthesis by using reverse transcriptase (RT) superscript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. PCR involved denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min; and a final incubation at 72 °C for 10 min. As controls for DNA contamination, reactions were also performed without RT (RT−), side-by-side with the experimental reactions. All reactions were followed by treatment with Rnase A for 20 min at 37 °C. SSCP reactions were performed according to Richard and Adams (2003). The same PCR and SSCP conditions were used to explore whether rDNA loci had been eliminated physically. To control PCR amplification biases, mixed parent templates were used in the same reaction. The primer pair 5′–CTGGTTTCATCCGTCTT–3′ 5′–AGTTGGTCTGTAGTTGGGT–3′ (Delseny et al., 1990; Chen & Pikaard, 1997) was designed on the basis of intergenic spacer sequences of rRNA genes in B. oleracea, B. rapa and B. nigra to amplify sequences of hexaploids and seven complex hybrids with hexaploids II, hexaploids III and three of 30 complex hybrids with hexaploids I, as other complex hybrids were not available.

RESULTS

Phenotype and chromosome complements of complex hybrids

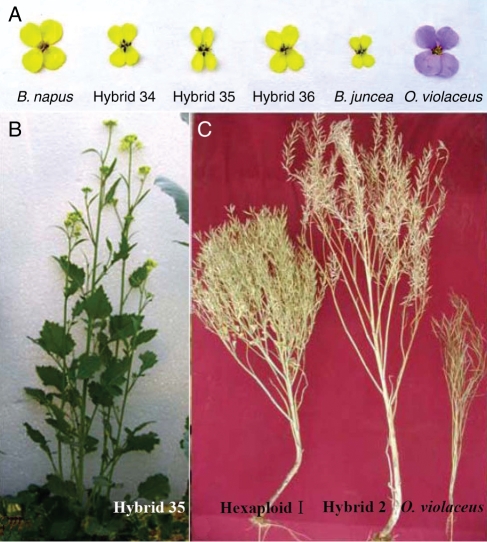

Among 37 complex hybrids produced with variable pollen fertility and seed-sets, 30, 4 and 3 were from crosses with hexaploids I, II and III, respectively (Table 3). They exhibited different phenotypes from the hexaploids or the progenitors of the hexaploids, and expressed some traits from O. violaceus, such as hairy leaves and basic clustering stems; they also showed variations in morphology. Mature plants of all complex hybrids were taller than those of parents (Fig. 3). Seven complex hybrids from crosses with hexaploids II and III were self-incompatible, as the female hexaploids. Four complex hybrids (nos 33–36) had a morphology similar to B. juncea with papilionaceous flowers (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Cytology and AFLP analyses of hybrids between three Brassica allohexaploids and O. violaceus

| Average numbers and ranges of AFLP bands per plant* |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crosses with: | No. of hybrids (designations) | Most frequent chromosome numbers (per plant) and ranges | Pairing of B. nigra chromosomes | Average pollen stainability (ranges) | S | N | D |

| Hexaploid I | 1–27 | 44 (37–45) | 8 II | 75·1 ± 9·9 (54·6–90·4) | 48 ± 6·6 (37–61) | 72 ± 11 (53–87) | 15 ± 8·4 (5–32) |

| 28–30 | 42 (36–43) | 6 II + 2I | 35·6 ± 4·9 (30·0–39·7) | 48 ± 1·5 (47–50) | 62 ± 9·9 (55–73) | 62 ± 14 (46–70) | |

| Hexaploid II | 31–33 | 44 (36–46) | 8 II | 69·9 ± 19·4 (55·6–91·9) | 2·7 ± 0·6 (2–3) | 33·7 ± 13·6 (18–41) | 8 ± 0 (8–8) |

| 34 | 42 (40–44) | 8 II | 68·3 | 3 | 42 | 10 | |

| Hexaploid III | 36, 37 | 44 (40–46) | 8 II | 31·6 ± 30·5 (10·0–53·2) | 1·5 ± 0·7 (1–2) | 86 ± 0 (86–86) | 17·5 ± 2·1 (16–19) |

| 35 | 36 (34–38) | 6 II + 2I | 27·1 | 2 | 83 | 34 | |

* S, O. violaceus-specific bands; D, absent bands in hexaploids; N, novel bands not present in two parents.

Fig. 3.

Morphology of complex hybrids between Brassica hexaploids and O. violaceus. (A) The shape and disposition of petals of three hybrids, especially hybrid no. 35, are similar to B. juncea. (B) Flowering hybrid no. 35, similar to B. juncea. (C) Mature plants of Hexaploid I, hybrid no. 2 and O. violaceus. The hybrid (no. 2) was taller than parents and had pods with several seeds.

All complex hybrids were mixoploids, consisting of cells with variable chromosomes (2n = 34–46) (Table 3); 2n = 44 was most frequent in 32 (nos 1–27, 31–33, 36–37), 2n = 42 in four (nos 28–30, 34) and 2n = 36 in one plant (no. 35) (Table 3). In pollen mother cells (PMCs) of these complex hybrids, as expected, various segregation patterns were observed at anaphase I (AI). PMCs with 2n = 44 exhibited main segregations of 22 : 22, 21 : 23 and 20 : 24, and those with 2n = 42 showed 21 : 21, 20 : 22 and 19 : 23 segregations. In AI/telophase I PMCs, 5–10 laggards per cell appeared frequently in all complex hybrids.

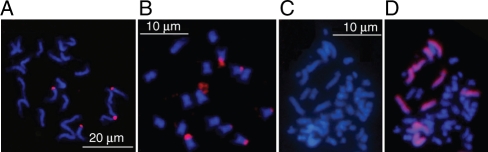

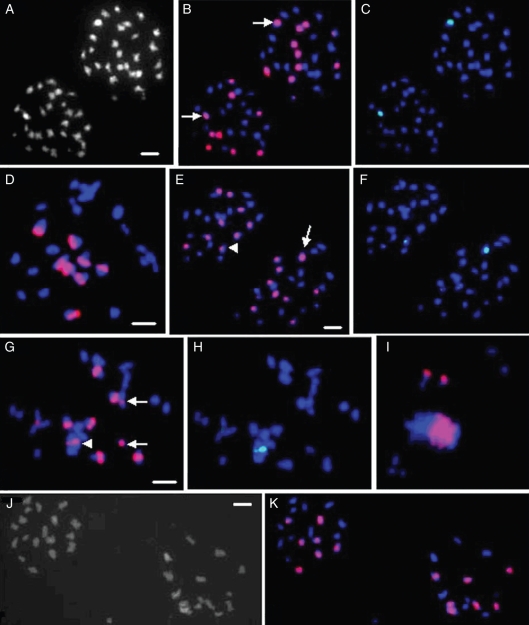

Before dual-colour GISH analyses on hybrids between hexaploids and O. violaceus, control GISH analyses of probe O. violaceus chromosomes with a B. nigra probe and vice versa were made without blocking DNA. Signals of different sizes appeared only at chromosomal terminals or satellites of several chromosomes in B. nigra or O. violaceus, probably corresponding to 45S rDNA sites (Fig. 4A, B). This not only helps to explain signals from cross-hybridizations in hexaploids and their hybrids with O. violaceus (Fig. 5A–K) but also reveals the low homology between the genomic DNA of these two species. When O. violaceus genomic probe was applied to O. violaceus preparations, signals were distributed along the whole length of chromosomes (Hua et al., 2006) while GISH in Brassica is normally characterized by strong signals at centromeric heterochromatin and only very weak hybridization on chromosome arms (Snowdon et al., 1997). This made it easy to distinguish the parental chromosomes in their hybrids. With the labelled O. violaceus DNA as probe, its chromosomes in the BC1 plants of somatic hybrids with B. napus were easily distinguished from those of B. napus by the even distribution of bright signals, particularly their larger size and deeper staining (Fig. 4C, D; Zhao et al., 2008).

Fig. 4.

GISH analyses of O. violaceus, B. nigra and BC1 plants of somatic hybrids between B. napus and O. violaceus. (A) One root-tip cell of O. violaceus (2n = 24) and four chromosome terminals were labelled by B. nigra probe. (B) One root-tip cell of B. nigra (2n = 16) and six chromosome terminals were labelled by O. violaceus probe. (C, D) One prometaphase of the ovary cell in a BC1 plant (C) with 12 chromosomes from O. violaceus (D). Red signals are evenly distributed along the whole length of chromosomes from O. violaceus. Note that the labelled chromosomes are much longer than those unlabelled from B. napus. The images in (C) and (D) were kindly supplied by Dr Z. G. Zhao. Scale bar in (C) also applies to (D).

Fig. 5.

GISH analyses of complex hybrids between Brassica hexaploids and O. violaceus. Red and green signals are from B. nigra and O. violaceus probes, respectively. (A–C) One AI PMC of hexaploid I with equal 27 : 27 segregation (A), in which nine chromosomes in each polar group are strongly labelled by B. nigra probe (B), but one chromosome with terminal signal (arrows) was also labelled by O. violaceus probe (C). The large terminal signals from both probes probably mark the rDNA locus from B. rapa. Thus, the hexaploid contained the expected 16 B. nigra chromosomes with normal segregation. (D) One PMC at diakinesis from hybrid no. 31 with eight bivalents labelled by B. nigra probe. (E, F) One AI PMC of hybrid no. 2 showing 24 : 24 segregation, in which a total of 19 chromosomes are labelled by B. nigra probe (E), but one large terminal signal (arrow) in one polar group and one small centromeric signal (arrowhead) in another group were overlapped by O. violaceus probe (F). The large terminal signal probably marks the rDNA locus from B. rapa. Then 16 B. nigra chromosomes with normal segregation are included, but no chromosomes from O. violaceus. (G, H) One diakinesis PMC of hybrid no. 28. Centromeric parts of six bivalents, two univalents (arrows) and two terminals of one V-shaped bivalent (arrowhead) are strongly labelled by B. nigra probe (G). However, the terminal signals of the V-shaped bivalent are also overlapped by the O. violaceus signals (H), which shows rDNA loci. Note that one signal is much lager than another of the V-shaped bivalent, and that only one chromosome is found to carry the large terminal overlapped signal in the cell above (E and F). So 14 chromosomes are from B. nigra but none from O. violaceus. (I) One MI PMC of hybrid no. 35 with two labelled B. nigra chromosomes lagged around the metaphase plate and bivalents arranged on the plate. (J, K) One AI PMC of hybrid no. 35 with 18 : 16 segregation (J) and seven chromosomes labelled by B. nigra probe in each polar group (K). Scale bar = 5 µm. Different images of the same PMC have the same scale bar, which is presented on the first image; and the scale bar in (G) also applies to (I).

When O. violaceus (green signal) and B. nigra probes (red signal) were applied simultaneously to chromosome preparations of PMCs of three hexaploids, 16 B. nigra chromosomes were easily distinguished based on their strong centromeric signals, which showed a normal 8 : 8 segregation (Fig. 5A–C). Two terminals of one bivalent or one terminal of one chromosome in each AI group were strongly labelled by the two probes (Fig. 5A–C), which might mark the satellited chromosomes from B. rapa, as observed previously (Hasterok et al., 2005; Liu & Li, 2007; Zhao et al., 2007), and also made it possible to identify such chromosomes in complex hybrids. The other overlapping minor signals at centromeric or terminal parts were possibly from other repeated sequences.

GISH analysis of these complex hybrids revealed that no intact chromosomes from O. violaceus were present; however, 14 or 16 B. nigra chromosomes were detected in their somatic cells and PMCs (Fig. 5D–K). Thirty-three complex hybrids (nos 1–27, 31–34, 36, 37) contained 16 B. nigra chromosomes forming eight bivalents at diakinesis and segregated as 8 : 8 at AI; four plants (nos 28–30, 35) had 14 B. nigra chromosomes which appeared as six bivalents and two univalents at diakinesis and 6 : 8 or 7 : 7 segregation at AI (Table 3; Fig. 5). Complex hybrids with 16 B. nigra chromosomes showed much higher fertility as compared with those having 14 B. nigra chromosomes (Table 3). In the complex hybrids with hexaploid I, one chromosome with large and overlapped signals at the terminal of the short arm from the probes of B. nigra and O. violaceus was probably from B. rapa (Hasterok et al., 2005), as the hexaploids had two such chromosomes (Fig. 5A–C).

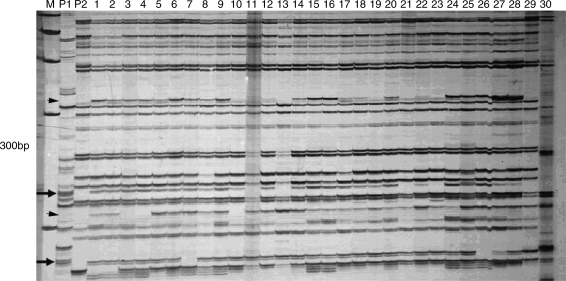

Molecular characterization of the complex hybrids

From 30 pairs of AFLP primers, 1014 and 1194 bands were amplified in hexaploid I and O. violaceus, respectively. By using 25 pairs of primers, 748, 720 and 845 bands were scored in hexaploids II, III and O. violaceus, respectively. AFLP analyses revealed that most of the bands in hexaploids could be amplified in all complex hybrids, together with three types of novel bands: O. violaceus-specific bands, absent bands in hexaploids and novel bands not present in the two parents (Fig. 6). Although each complex hybrid had O. violaceus-specific bands, plants 1–30 from hexaploid I showed many more such bands (1·6 bands per primer per plant) than plants 31–37 from hexaploids II (0·11) and III (0·07). But complex hybrid plants from hexaploid III had more novel bands (3·38 bands per primer per plant) than plants from hexaploid I (2·37) and II (1·43). More deleted bands in maternal hexaploids appeared in the complex hybrids with 14 B-genome chromosomes than those with 16 B-genome chromosomes (Table 3). The occurrence of novel and O. violaceus-specific bands was significantly correlated (r = 0·76; t = 5·31 > t0·01 = 2·763) in plants 1–30 (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

AFLP profiles of complex hybrids between hexaploid I and O. violaceus, generated from the primer pair 5′–GACTGCGTACCAATTCATA–3′ and 5′–GATGAGTCCTGAGTAACAC–3′. M, marker; P1, O. violaceus; P2, hexaploid I; 1–30, hybrids 1–30. Arrows show bands specific for O. violaceus; arrowheads show novel bands not present in any of the parents.

Progenies with B. juncea-type phenotype and genetic constitutions

Progenies of those complex hybrids with hexaploid I in two generations (F2, F3) were characterized phenotypically and cytologically. The majority of F3 plants had a B. juncea-type phenotype with high fertility and their chromosome numbers centred at 36, whereas others with low fertility had different chromosome numbers. F3 plants from hexaploid I showed higher seed-sets after crossing with B. juncea than with B. carinata, and their hybrids with B. juncea had much higher pollen fertility (approx. 87·9 %) than those with B. carinata (28·7 %). The F1 plants from hexaploids II and III also showed higher seed-sets after crossing with B. juncea than with B. napus, and their hybrids with B. juncea had much higher pollen fertility (average 86·7 %) than those with B. napus (28·6 %). Further selfing and selection produced novel B. juncea lines with good seed-set. Those from complex hybrids with hexaploids I should have the A genome from natural B. rapa and the B genome from B. carinata, those from complex hybrids with hexaploids II should have the A genome from B. napus and the B genome from natural B. nigra, and those from complex hybrids with hexaploids III should have the A genome from natural B. rapa and the B genome from natural B. nigra. These results also suggested that the chromosome complements of these complex hybrids were inclined to B. juncea. These complex hybrids and their progenies maintained all the chromosomes from B. nigra and the majority from B. rapa, while the majority of chromosomes from B. oleracea were lost.

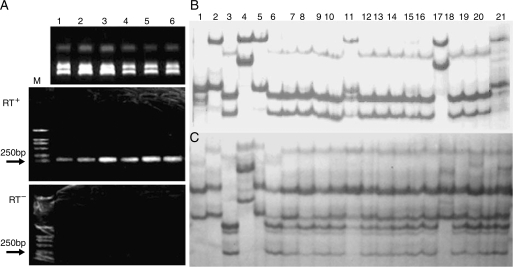

Expression of rRNA genes in hexaploids and complex hybrids

The contribution to the transcriptome of transcripts derived from rRNA genes was examined to determine whether there was a bias in transcript levels from different genomes. RT-PCR was performed on cDNA templates from the natural allotetraploid B. napus, B. juncea and progenitor diploids together with O. violaceus, synthetic hexaploids and their complex hybrids. All cDNA templates were checked for genomic DNA contamination by using RT− controls containing all RT reagents except reverse transcriptase. No DNA contamination was detected (Fig. 7). RT-PCR products derived from each genome were assayed by SSCP gels. As expected, in natural B. napus and B. juncea, only rRNA genes from the A and B genome were transcribed, respectively. In all complex hybrids, transcripts from B. nigra were detected while those from B. oleracea were not. The rRNA genes from B. rapa were transcribed in only one complex hybrid (no. 35) with 14 B. nigra chromosomes in which only one chromosome with rRNA genes was probably included (Fig. 7). Expression of rRNA genes from O. violaceus was not detected in these complex hybrids without its intact chromosomes, but was readily detected in the somatic hybrid between B. napus and O. violaceus, revealing the dominance of its rRNA genes over those from the A genome in B. napus. The detection of rRNA transcripts in hexaploids from only B. nigra also showed that the hierarchy of nucleolar dominance (B > A > C) in three cultivated Brassica allotetraploids (Chen and Pikaard, 1997) was still valid. Genomic DNA PCR-SSCP analyses showed that all parental bands could be produced in sexual complex hybrids except those from O. violaceus, which could be found in somatic hybrids, and thus that rRNA gene silencing did not resulted from sequence elimination (Fig. 7). In particular, one complex hybrid (no. 35) with 14 B. nigra gave weak bands specific for the B genome, which further indicated that the lost chromosome might contain rDNA loci.

Fig. 7.

DNA and RT-PCR SSCP analysis of rRNA genes. (A) Control for DNA contamination, RT+ and RT− show reactions with or without reverse transcription (RT) of samples 1–6; (B) RT-PCR SSCP of pre-rRNA transcripts; (C) genomic DNA PCR-SSCP profile. From left to right, 1–6: B. oleracea, B. rapa, B. nigra, O. violaceus, B. napus, and B. juncea; 7–9: hexaploids I, II and III; 10–12: hybrids 36, 35 and 37; 13–16: hybrids 31–34; 17, the somatic hybrid between B. napus and O. violaceus; 18–20: hybrids 5, 23 and 27; 21: mixture of B. nigra, B. rapa, B. oleracea and O. violaceus.

DISCUSSION

Chromosomal/genomic complements of complex hybrids and progenies showing genome-specific chromosome stability in allohexaploids

Cytological and GISH analyses revealed that all complex hybrids between hexaploids and O. violaceus were mixoploids, composed of cells (2n = 34–46) with partial hexaploid complements and without any intact O. violaceus chromosomes but some chromosomal segments. The genomic components of these complex hybrids and their progenies, and the morphology and genetic behaviour of the progenies further showed that the complex hybrids had all the chromosomes of the A and B genomes and variable numbers from the C genome. These complex hybrids produced progenies with phenotypes and genetic compositions biased to B. juncea (Figs 2 and 3) and after five generations gave rise to new B. juncea types with A and B genomes of different origins. Genetic analysis of these complex hybrids and their progenies showed that the chromosomes from the A and B genomes in allohexaploids were preferentially maintained while those from the C genome were lost.

Because GISH only clearly distinguished the B genome chromosomes from those of the A genome in B. juncea and of the C genome in B. carinata, but not the A genome chromosomes from those of the C genome in B. napus (Snowdon et al., 1997; the present study), genome-specific repeats for Brassica (e.g. pBNBH35 for the B genome, Schelfhout et al., 2004; BoB014O06 from the C genome, Howell et al., 2002; intergenic spacer of the 45 S rDNA from the C genome, Howell et al., 2008) should be used as probes for further study to determine more accurately the chromosome complements of these complex hybrids and their progenies.

It should be pointed out that unstable chromosome pairings and segregations of female allohexaploids (Table 2) may produce the gametes with variable chromosomes and then affect the chromosome complements of the complex hybrids from the crosses with O. violaceus, although the euploidy gametes (n = 27, ABC) are probably viable and give rise to the complex hybrids observed here. In future, it will be necessary first to obtain stable hexaploid lines through several generations and then cross them with O. violaceus.

Parental genome separation and chromosome elimination producing complex hybrids with partial complements of allohexaploids

All hybrids between the cultivated Brassica species and O. violaceus, except that with B. oleracea, have variable chromosomes in their somatic and meiotic cells, owing to the occurrence of complete and partial separation of parental genomes during mitotic divisions of hybrid cells (Li et al., 1995, 1998; Li & Heneen, 1999; Hua et al., 2006; Li and Ge, 2007; Fig. 1). A preponderance of cells in hybrids have entire complements of female Brassica parents, which contributes to the female phenotypes and high fertility of these hybrids. Those cells mainly having the O. violaceus complements are probably eliminated because of poor viability during embryonic and plant developmental. Parental genome separation may explain the mixoploid nature and chromosome complements of the complex hybrids with these hexaploids. One distinct difference is that the cells of complex hybrids in the present study only have partial complements of female hexaploids, and no cells with the same number (2n = 54) as or higher than that of the hexaploid parents are observed, suggesting that partial genome separation prevails with some Brassica chromosomes being lost (Figs 2 and 5). The genomes of these complex hybrids have experienced chromosome doubling, most likely during embryo development, because the majority of them contained all chromosomes of the A and B genomes plus variable numbers from the C genome. The fact that all complex hybrids have the partial complements of female hexaploids also showed that the polyploids are more resistant to chromosome loss than Brassica diploids and tetraploids, as Brassica aneuploids with some chromosomes lost are infrequently recovered in crosses with O. violaceus (Li et al., 1998; Li and Heneen, 1999; Hua and Li, 2006). However, the similar complements of the complex hybrids from crosses with hexaploids of different origins indicate that their chromosome behaviours are controlled by the same mechanism.

Alien DNA introgression and genomic changes in the complex hybrids

Partial hybrids with female parent-type phenotype and chromosome number but some DNA sequences of male parent origin or novel for two parents have been reported in coffee (Lashermes et al., 2000), sunflower (Faure et al., 2002), rapeseed (Cheng et al., 2002; Hua et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; Liu and Li, 2007; Du et al., 2008; Tu et al., 2009) and rice (Wang et al., 2005). Possible processes involve early elimination of alien fragments or chromosomes of the male parent, genome rearrangements following genomic shock (McClintock, 1984; Madlung and Comai, 2004) and diploidization (Faure et al., 2002). Moreover, <0·1 % alien introgressed DNA induces extensive and genome-wide de novo variations in up to 30 % of the loci in rice recombinant inbred lines, with the loss of parental bands being more frequent than the gain of novel bands (Wang et al., 2005). One reason for the novel bands in the present crosses might be recombination from the introgressions of O. violaceus fragments into Brassica chromosomes, which were not detected as most of the introgressed fragments were not within the resolution range of the GISH analyses. Consistent with this, the occurrence of novel and O. violaceus-specific bands were significantly correlated in a lot of complex hybrids (nos 1–30) with hexaploids I.

Another reason for the production of novel and deleted bands (Table 3; Fig. 6) might be chromosomal rearrangements through intergenomic translocations/transpositions (Udall et al., 2005) and homoeologous pairing (Leflon et al., 2006; Nicolas et al., 2007), because three Brassica genomes are considered to be derived from a common ancestral genome and thus partially homologous (Lagercrantz & Lydiate, 1996; Lysak et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2006). The widespread chromosomal rearrangements caused by homoeologous recombination are detected in B. napus (Leflon et al., 2006; Nicolas et al., 2007) and have consequences for allelic and phenotypic diversity (Osborn et al., 2003b; Pires et al., 2004; Udall et al., 2005; Gaeta et al., 2007). In resynthesized B. napus lines independently derived by hybridizing double haploids of B. oleracea and B. rapa, few genetic changes are revealed in the initial allotetraploids, but segregations for a number of non-reciprocal translocations between parental homoeologues are displayed in subsequent selfed progenies (Gaeta et al., 2007). In complex hybrid plants from hexaploids II and III, fewer specific bands of O. violaceus but more novel bands were found, especially in three complex hybrids from hexaploid III. These results were consistent with the higher pairing frequency between the B genome and the A/C genomes in trigenomic hybrids (2n = 27, ABC) from which hexaploids III were derived (Ge and Li, 2007).

The production of the novel and deleted bands might also be related to rapid sequence elimination, as has been reported in synthetic hybrids and allopolyploids of Brassica, triticale and Aegilops–Triticum (Song et al., 1995; Ozkan et al., 2001). Notably, the origin of hexaploids seems to affect the numbers of the O. violaceus- specific bands in complex hybrids, as complex hybrids with hexaploids I have many more such AFLP bands than those with hexaploids II and III. Whether methylation changes and reactivation of transposons (Liu and Wendel, 2003) also contributed to genomic variations in F1 plants needs further study.

It should be mentioned that AFLP markers are not dosage sensitive and cannot detect the genomic changes resulting from chromosome loss or chromosome rearrangements where one homoeologue is lost while another is gained. This may explain why most bands in the hexaploids can still be amplified in all complex hybrids containing only their partial complements (2n = 34–46). So the genomic changes in these complex hybrids are probably underestimated by AFLP analysis, particularly for the novel and absent bands. Howeber, this underestimation is possibly reduced in these hybrids, because they experience chromosome doubling and so possess homologous chromosomes/loci.

Genome-specific chromosome stability and nucleolar dominance

The detection of only pre-rRNA transcripts from B. nigra in hexaploids showed that the hierarchy of nucleolar dominance in three Brassica tetraploids (B > A > C) (Chen and Pikaard, 1997) is established upon synthesis of these hexaploids (Fig. 7). B. nigra is the cytoplasmic donor of B. carinata, while in B. napus there is a slightly altered B. oleracea cytoplasm. The presence of different types of cytoplasm in various accessions of B. napus strongly supports its multiple origins (Song and Osborn, 1992). The synthetic B. napus used in the present study should have the cytoplasm of female parent B. oleracea (Chen et al., 1988). Thus, hexaploids I, II and III have cytoplasm from B. nigra, possibly B. oleracea and B. oleracea, respectively, but rRNAs of ribosomes in cytoplasm of hexaploids II and III are replaced by those transcribed from the genes of B. nigra. As different Brassica diploids and tetraploids are used in the synthesis of hexaploids, they have differences in genetic structure (Ge and Li, 2007), as manifested by their different phenotypes, chromosome segregations and seed-sets after selfing or crosses with O. violaceus (Fig. 2; Table 2). However, the complex hybrids between these hexaploids and O. violaceus have similar chromosome/genomic complements biased to B. juncea-type (Figs 4 and 5). Thus, the retention of chromosomes from hexaploids is genome-specific and shows the same hierarchy as that of nucleolar dominance, which suggests that nucleolar dominance is probably correlated with chromosome stabilization; this was speculated in hybrids with B. carinata in which more chromosomes from B. nigra than from B. oleracea were maintained in cells with partial B. carinata complements (2n < 34) (Hua et al., 2006). This is the opposite of that expected based on cytology in hybrids of O. violaceus with B. oleracea and B. nigra (Li and Heneen, 1999).

In retrospect, the different chromosome behaviours in hybrids between three Brassica allotetraploids and O. violaceus also underlined the different stabilities of their genomes and were possibly connected with the hierarchy of nucleolar dominance. The hybrids with B. carinata showed least variation in chromosome complements or genomic compositions and also least phenotypic deviation from the B. carinata parent (Li et al., 1998; Hua et al., 2006). Hybrids involving B. napus (Li et al., 1995; Hua and Li, 2006) or B. juncea (Li et al., 1998) showed a much wider range of chromosome numbers, and those with B. napus can tolerate the loss of more chromosomes from the complements of B. napus. The chromosomes of B. carinata, in which one progenitor B. nigra is at the top of the nucleolar-dominance hierarchy and another B. oleracea at the bottom (Fig. 1), are most stable in crosses with O. violaceus.

In reciprocal synthesis of Brassica allotetraploids, the frequencies of genetic changes are higher when the donor of the genome with nucleolar dominance is used as the male parent (Song et al., 1995). Hexaploid I with the cytoplasm and rRNAs from B. nigra show more regular meiotic behaviour, higher fertility and crossability than hexaploids II and III with B. oleracea cytoplasm and B. nigra rRNAs (Table 2). These phenomena suggest that the replacement of rRNA through nucleolar dominance may have some genetic consequences in allopolyploids.

Interestingly, in the newly synthesized somatic hybrids with B. napus containing the 24 O. violaceus chromosomes (Zhao et al., 2008), the transcripts of the rRNA genes from O. violaceus (Fig. 7), but not from the A genome of B. rapa, were detected, which may add further evidence for the role of nucleolar dominance in stabilizing chromosomes. Furthermore, O. violaceus also seems to be phenotypically dominant over B. napus (Zhao et al., 2008) as in arabidopsis allotetraploids (Wang et al., 2006; Chen, 2007). Jones and Pašakinskienè (2005) showed that suppression of activity of nucleolus organizing regions (the chromosomal loci of rRNA genes) in Hordeum bulbosum chromosomes in interspecific hybrids could be related to the elimination of H. bulbosum chromosomes, and it is possible that a similar mechanism could be acting in our hybrids.

Given the evidence presented connecting chromosomal stabilities in these intergeneric hybrids with nucleolar dominance, what are the molecular, ultrastructural and cytogenetic factors that may connect the two phenomena? The nucleolus, the site of rRNA gene transcription and ribosome assembly, has other, far more diversified roles (Moss and Stefanovsky, 2002). Regulation of the cell cycle, of senescence and aspects of transport are among the other functions controlled by factors localized to the nucleus (Olson et al., 2000). As some of the most ancient cellular components, rRNAs have developed over evolutionary time for efficient catalysis and regulation of all aspects of protein synthesis (Doudna & Rath, 2002). During the evolution of polyploid yeasts, reciprocal gene loss is biased towards genes involved in ribosome biogenesis (Scannell et al., 2006). In the case of nucleolar dominance, activity of the translational machinery determined by the rRNA genes from the donor parent may be responsible for the dominance of its transcriptome, proteome and phenotype in some allopolyploids. Conversely, the masking of the transcriptome and phenotype from another parent with recessive rRNA genes is largely due to inactivity of its translational machinery (Hegarty and Hiscock, 2008). Similarly, production of chromosome/centromere-specific proteins of the rRNA-donor parent and the stability of its chromosomes are speculated to benefit from the activity of its translational machinery. The replacement of rRNAs by those from B. nigra in hexaploids II and III possibly contributes to their more irregular meiotic pairing and segregation than in hexaploid I with ribosome rRNAs unchanged.

Conclusions

Hybridizations between Brassica allotetraploids/allohexaploids and O. violaceus are effective in producing progenies with partial chromosomal complements of Brassica parents and with or without some genetic elements of O. violaceus. Thus, chromosome stabilization of ancestral genomes in Brassica allopolyploids after alien chromosome elimination has been revealed and a possible correlation with nucleolar dominance is proposed, which provides a valuable addition to our knowledge of chromosome elimination in plant-wide crosses or stabilization during evolution of allopolyploids. In future, it will be of value to observe the stability of chromosomes in allopolyploids over several generations (Table 2), which may reveal whether chromosome elimination occurs to the same extent as in these complex hybrids, and whether chromosome elimination of Brassica chromosomes is independent of O. violaceus. Investigations of centromere proteins or the expression of centromere protein genes might reveal the molecular links between nucleolar dominance and chromosome stability in Brassica allopolyploids.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Shyam Prakash, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, for critical reading of the manuscript, anonymous reviewers for constructive comments and Dr Z. G. Zhao for supplying unpublished pictures. This work was supported by the Education Ministry of PR China (to Z.L.), by PCSIRT (IRT0442) and by the International Foundation for Science (C/4403-1 to G.X.H.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Al-Shehbaz IA. The genera of Brassiceae (Cruciferae, Brassicaceae) in the southeastern United States. Journal of Arnold Arboretum. 1985;66:279–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bassam B, Caetano-Anolles G, Gresshoff PM. Fast and sensitive silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Analytical Biochemistry. 1991;196:80–83. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90120-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD, Finch RA, Barclay IR. The time rate and mechanism of chromosome elimination in Hordeum hybrids. Chromosoma. 1976;54:175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Breeuwer JAJ, Werren JH. Microorganisms associated with chromosome destruction and reproductive isolation between two insect species. Nature. 1990;346:558–560. doi: 10.1038/346558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BY, Heneen WK, Jønsson R. Resynthesis of Brassica napus L. through interspecific hybridization between B. alboglabra Bailey and B. campestris L. with special emphasis on seed colour. Plant Breeding. 1988;101:52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen HF, Wang H, Li ZY. Production and genetic analysis of partial hybrids in intertribal crosses between Brassica species (B. rapa, B. napus) and Capsella bursa-pastoris. Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26:1791–1800. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0392-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2007;58:377–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Ni ZF. Mechanisms of genomic rearrangements and gene expression changes in plant polyploids. BioEssays. 2006;28:240–252. doi: 10.1002/bies.20374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Pikaard CS. Transcriptional analysis of nucleolar dominance in polyploid plants: biased expression/silencing of progenitor rRNA genes is developmentally regulated in Brassica. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:3442–3447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng BF, Séguin-Swartz G, Somers DJ. Cytogenetic and molecular characterization of intergeneric hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus. Genome. 2002;45:110–115. doi: 10.1139/g01-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L. Genetic and epigenetic interactions in allopolyploid plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;43:387–399. doi: 10.1023/a:1006480722854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L. The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploidy. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2005;6:836–846. doi: 10.1038/nrg1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comai L, Tyagi AP, Winter K, et al. Phenotypic instability and rapid gene silencing in newly formed Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1551–1567. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaporta SL, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA mini preparation: version II. Plant Molecular Biology Report. 1983;1:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Delseny M, Mcgrath JM, This P, Chevre AM, Quiros CF. Ribosomal RNA genes in diploid and amphidiploid species of Brassica and related species: organization, polymorphism and evolution. Genome. 1990;33:733–744. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Flagel LE, Paterson AH, et al. Evolutionary genetics of genome merger and doubling in plants. Annual Review of Genetics. 2008;42:443–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA, Rath VL. Structure and function of the eukaryotic ribosome: the next frontier. Cell. 2002;109:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00725-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XZ, Ge XH, Zhao ZG, Li ZY. Chromosome elimination and fragment introgression and recombination producing intertribal partial hybrids from Brassica napus × Lesquerella fendleri crosses. Plant Cell Reports. 2008;27:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure N, Serieys H, Berville A, Cazaux E, Keen F. Occurrence of partial hybrids in wide crosses between sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and perennial species H. mollis and H. orgyalis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104:652–66. doi: 10.1007/s001220100746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch RA. Tissue-specific elimination of alternative whole parental genomes in one barley hybrid. Chromosoma. 1983;88:386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Finch RA, Bennett MD. The mechanism of somatic chromosome elimination in Hordeum. In: Brandham PE, editor. Kew Chromosome Conference II: Proceedings of the Second Chromosome Conference. London: Allen & Unwin; 1983. pp. 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara A, Abe S, Yamaha E, Yamazaki F, Yoshida MC. Uniparental chromosome elimination in the early embryogenesis of the inviable salmonid hybrids between masu salmon female and rainbow trout male. Chromosoma. 1997;106:44–52. doi: 10.1007/s004120050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta RT, Pires JC, Iniguez-Luy F, Leon E, Osborn TC. Genomic changes in resynthesized Brassica napus and their effect on gene expression and phenotype. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3403–3417. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge XH, Li ZY. Intra- and intergenomic homology of B-genome chromosomes in trigenomic combinations of the cultivated Brassica species revealed by GISH analysis. Chromosome Research. 2007;15:849–861. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernand D, Rutten T, Varshney A, et al. Uniparental chromosome elimination at mitosis and interphase in wheat and pearl millet crosses involves micronucleus formation, progressive heterochromatinization, and DNA fragmentation. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2431–2438. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SB. Duration of mitotic cycle and regulation of DNA replication in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia and a hybrid derivative of N. tabacum showing chromosome instability. Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology. 1969;11:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hasterok R, Wolny E, Kulak S, Zdziechiewicz A, Maluszynska J, Heneen WK. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of Brassica rapa-Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra monosomic addition lines. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;111:196–205. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-1942-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty MJ, Hiscock SJ. Genomic clues to the evolutionary success of polyploid plants. Current Biology. 2008;18:R435–R444. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EC, Barker GC, Jones GH, et al. Integration of the cytogenetic and genetic linkage maps of Brassica oleracea. Genetics. 2002;161:1225–1234. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell EC, Kearsey MJ, Jones GH, King GJ, Armstrong SJ. A and C genome distinction and chromosome identification in Brassica napus by sequential fluorescence in situ hybridization and genomic in situ hybridization. Genetics. 2008;180:1849–1857. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.095893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua YW, Li ZY. Genomic in situ hybridization analysis of intergeneric hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus and production of B. napus aneuploids. Plant Breeding. 2006;125:144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hua YW, Liu M, Li ZY. Parental genome separation and elimination of cells and chromosomes revealed by AFLP and GISH analyses in a Brassica carinata × Orychophragmus violaceus cross. Annals of Botany. 2006;97:993–998. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin WW, Melo JR, Nagaki K, et al. Maize centromeres: organization and functional adaptation in the genetic background of oat. Plant Cell. 2004;16:571–581. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Pašakinskienè I. Genome conflict in the gramineae. New Phytologist. 2005;165:391–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha KJ, Kao KN. High frequency haploid production in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Nature. 1970;225:874–876. doi: 10.1038/225874a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NS, Armstrong KC, Fedak G, Ho K, Park NI. A microsatellite sequence from the rice blast fungus (Magnaporthe grisea) distinguishes between the centromeres of Hordeum vulgare and H. bulbosum in hybrid plants. Genome. 2002;45:165–174. doi: 10.1139/g01-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz U, Lydiate D. Comparative genome mapping in Brassica. Genetics. 1996;144:1903–1910. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashermes P, Andrzejewski S, Bertrand B, et al. Molecular analysis of introgressive breeding in coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2000;100:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Leflon M, Eber F, Letanneur JC, et al. Pairing and recombination at meiosis of Brassica rapa (AA) × Brassica napus (AACC) hybrids. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2006;113:1467–1480. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch AR, Leitch IJ. Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science. 2008;320:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1153585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch AR, Schwarzacher T, Jackson D, Leitch IJ. Microscopy Handbook No. 27. In situ hybridization: a practical guide. Oxford: Bios Scientific; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. The role of chromosomal change in plant evolution. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li ZY, Ge XH. Unique chromosome behavior and genetic control in Brassica × Orychophragmus wide hybrids: a review. Plant Cell Reports. 2007;26:701–710. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Heneen WK. Production and cytogenetics of intergeneric hybrids between the three cultivated Brassica diploids and Orychophragmus violaceus. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1999;99:694–704. doi: 10.1007/s001220051286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Liu HL, Luo P. Production and cytogenetics of intergeneric hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1995;91:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00220869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wu JG, Liu Y, Liu HL, Heneen WK. Production and cytogenetics of intergeneric hybrids Brassica juncea × Orychophragmus violaceus and B. carinata × O. violaceus. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1998;96:251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Linde-Laursen I, von Bothmer R. Orderly arrangement of the chromosomes within barley genomes of chromosome-eliminating Hordeum lechleri × barley hybrids. Genome. 1999;42:225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Wendel JF. Non-Mendelian phenomenon in allopolyploid genome evolution. Current Genomics. 2002;3:489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Wendel JF. Epigenetic phenomena and the evolution of plant allopolyploids. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003;29:365–379. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Li Z. Genome doubling and chromosome elimination with fragment recombination leading to the formation of Brassica rapa-type plants with genomic alterations in crosses with Orychophragmus violaceus. Genome. 2007;50:985–993. doi: 10.1139/g07-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens LN, Quijada PA, Udall J, Pires JC, Schranz ME, Osborn TC. Genome redundancy and plasticity within ancient and recent Brassica crop species. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004;82:665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Luo P, Lan ZQ, Li ZY. Orychophragmus violaceus, a potential edible-oil crop. Plant Breeding. 1994;113:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lysak MA, Koch MA, Pecinka A, Schubert I. Chromosome triplication found across the tribe Brassiceae. Genome Research. 2005;15:516–525. doi: 10.1101/gr.3531105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysak MA, Kwok C, Kitschke M, Bures P. Ancestral chromosomal blocks are triplicated in Brassiceae species with varying chromosome number and genome size. Plant Physiology. 2007;145:402–410. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madlung A, Comai L. The effect of stress on genome regulation and structure. Annals of Botany. 2004;94:481–495. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui S, Faitar SL, Rossi MR, Cowell JK. Application of spectral karyotyping to the analysis of the human chromosome complement of interspecies somatic cell hybrids. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2003;142:30–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00730-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science. 1984;226:792–801. doi: 10.1126/science.15739260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida K, Tsujimoto H, Sasakuma T. Confocal analysis of chromosome behavior in wheat × maize zygotes. Genome. 2004;47:199–205. doi: 10.1139/g03-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss T, Stefanosky VY. At the center of eukaryotic life. Cell. 2002;109:545–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashinge T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Navashin M. Chromosomal alterations caused by hybridization and their bearing upon certain general genetic problems. Cytologia. 1934;5:169–203. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas SD, Le Mignon G, Eber F, et al. Homeologous recombination plays a major role in chromosome rearrangements that occur during meiosis of Brassica napus haploids. Genetics. 2007;175:487–503. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.062968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MOJ, Dundr M, Szebeni A. The nucleolus: an old factory with unexpected capabilities. Trends in Cell Biology. 2000;10:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01738-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn TC, Pires JC, Birchler JA, et al. Understanding mechanisms of novel gene expression in polyploids. Trends in Genetics. 2003a;19:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(03)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn TC, Butrulle DV, Sharpe AG, et al. Detection and effects of a homeologous reciprocal transposition in Brassica napus. Genetics. 2003b;165:1569–1577. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M. Allopolyploidy-induced rapid genome evolution in the wheat (Aegiolops-Triticum) group. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1735–1743. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paun O, Fay MF, Soltis DE, Chase MW. Genetic and epigenetic alterations after hybridization and genome doubling. Taxon. 2007;56:649–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin IAP, Sharpe AG, Lydiate DJ. Patterns of genome duplication within the Brassica napus genome. Genome. 2003;46:291–303. doi: 10.1139/g03-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin IAP, Gulden SM, Sharpe AG, et al. Segmental structure of the Brassica napus genome based on comparative analysis with Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2005;171:765–781. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.042093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikaard CS. Nucleolar dominance: uniparental gene silencing on a multi-megabase scale in genetic hybrids. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;43:163–177. doi: 10.1023/a:1006471009225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires JC, Zhao J, Schranz ME, Quijada PA, Lukens LN, Osborn TC. Flowering time divergence and genomic rearrangements in resynthesized Brassica polyploids (Brassicaceae) Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004;82:675–688. [Google Scholar]

- Reed KM, Warren JH. Induction of parental genome loss by the parental-sex-ratio chromosome and cytoplasmic incompatibility bacteria (Wolbachia): a comparative study of early embryonic events. Molecular Reproduction and Development. 1995;40:408–418. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard CC, Adams KL. Quantitative analysis of transcript accumulation from genes duplicated by polyploidy using cDNA-SSCP. BioTechniques. 2003;34:726–734. doi: 10.2144/03344st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai C, Konno F, Nakano O, et al. Chromosome elimination in the interspecific hybrid medaka between Oryzias latipes and O. hubbsi. Chromosome Research. 2007;15:697–709. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell DR, Byrne KP, Gordon JL, Wong S, Wolfe KH. Multiple rounds of speciation associated with reciprocal gene loss in polyploidy yeasts. Nature. 2006;440:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature04562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelfhout CJ, Snowdon R, Cowling WA, Wroth JM. A PCR based B-genome-specific marker in Brassica species. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2004;109:917–921. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzacher-Robinson T, Finch RA, Smith JB, Bennett MD. Genotypic control of centromere positions of parental genomes in Hordeum × Secale hybrid metaphases. Journal of Cell Science. 1987;87:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Skalická K, Lim KY, Matyasek R, Koukalova B, Leitch AR, Kovarik A. Rapid evolution of parental rDNA in a synthetic tobacco allotetraploids line. American Journal of Botany. 2003;90:988–996. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.7.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon RJ, Köhler W, Friedt W, Köhler A. Genomic in situ hybridization in Brassica amphidiploids and interspecific hybrids. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95:1320–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Song KM, Osborn TC. Polyphyletic origins of Brassica napus: new evidence based on organells and nuclear RFLP analyses. Genome. 1992;35:992–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Song K, Lu P, Tang K., Osborn TC. Rapid genome change in synthetic polyploids of Brassica and its implications for polyploid evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:7719–7723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam NC, Kasha KJ. Selective chromosomal elimination during haploid formation in barley following interspecific hybridization. Chromosoma. 1973;42:111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Truco MJ, Hu J, Sadowski J, Quiros CF. Inter- and intra-genomic homology of the Brassica genomes: implications for their origin and evolution. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1996;93:1225–1233. doi: 10.1007/BF00223454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YQ, Sun J, Liu Y, Ge XH, Yao XC, Li ZY. Production and characterization of intertribal somatic hybrids of Raphanus sativus and Brassica rapa with dye and medicinal plant Isatis indigotica. Plant Cell Reports. 2008;27:873–883. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YQ, Sun J, Ge XH, Li ZY. Chromosome elimination, addition and introgression in intertribal partial hybrids between Brassica rapa and Isatis indigotica. Annals of Botany. 2009;103:1039–1048. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U N. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Japanese Journal of Botany. 1935;7:389–452. [Google Scholar]

- Udall JA, Quijada PA, Osborn TC. Detection of chromosomal rearrangements derived from homeologous recombination in four mapping populations of Brassica napus L. Genetics. 2005;169:967–979. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, et al. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Research. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tian L, Lee HS, et al. Genomewide nonadditive gene regulation in Arabidopsis allotetraploids. Genetics. 2006;172:507–517. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.047894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Dong ZY, Zhang ZJ, et al. Extensive de novo genomic variation in rice induced by introgression from wild rice (Zizania latifolia Griseb.) Genetics. 2005;170:1945–1956. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.040964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick SI, Sauder C. Phylogeny of the tribe Brassiceae (Brassicaceae) based on chloroplast restriction site polymorphisms and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and chloroplast trnL intron sequences. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2005;83:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MC, Green H. Human–mouse hybrid cell lines containing partial complements of human chromosomes and functioning human genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1967;58:1104–1111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.3.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TJ, Kim JS, Kwon SJ, et al. Sequence-level analysis of the diploidization process in the triplicated FLOWERING LOCUS C region of Brassica rapa. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1339–1347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZG, Ma N, Li ZY. Alteration of chromosome behavior and synchronization of parental chromosomes after successive generations in Brassica napus × Orychophragmus violaceus hybrids. Genome. 2007;50:226–233. doi: 10.1139/g06-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZG, Hu TT, Ge XH, Du XZ, Ding L, Li ZY. Production and characterization of intergeneric somatic hybrids between Brassica napus and Orychophragmus violaceus and their backcrossing progenies. Plant Cell Reports. 2008;27:1611–1621. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0582-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XB, de Hans JJ, Zabel P. Preparation of tomato meiotic pachytene and mitotic metaphase chromosomes suitable for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) Chromosome Research. 1996;4:24–28. doi: 10.1007/BF02254940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]