Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether school-meal observations influenced children’s 24-hour dietary recalls.

Study Design and Setting

Over three school years, 555 randomly selected fourth-grade children were interviewed to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall; before being interviewed, 374 children were observed eating two school meals (breakfast, lunch) and 181 children were not observed. Within observation-status groups (observed; unobserved), children were randomized within sex to one of six combinations from two target periods (prior-24-hours; previous-day) crossed with three interview times (morning; afternoon; evening).

Results

For each of five variables (interview length, meals/snacks, meal components, items, kilocalories), naïve and adjusted equivalence tests rejected that observation-status groups were different, indicating that school-meal observations did not influence children’s 24-hour dietary recalls. There was a target-period effect on length (P<0.0001) (longer for prior-24-hour recalls), a school year effect on length (P=0.0002) (longer for third year), and a target-period-by-interview-time interaction on items (P=0.0110) and kilocalories (P=0.0047) (both smaller for previous-day recalls in the afternoon than prior-24-hour recalls in the afternoon and previous-day recalls in the evening), indicating that variables were sufficiently sensitive and psychometrically reliable.

Conclusion

Conclusions about 24-hour dietary recalls by fourth-grade children observed eating school meals in validation studies are generalizable to 24-hour dietary recalls by comparable but unobserved children in non-validation studies.

Keywords: 24-hour dietary recalls, children, validation, observation, school breakfast, school lunch

What is new?

Key findings

For each of five response variables, naïve and adjusted equivalence tests rejected differences between observation-status groups, indicating that our implementation of school breakfast and school lunch observations did not influence fourth-grade children’s 24-hour dietary recalls. Furthermore, results concerning a target-period effect and a target-period-x-interview-time interaction indicated that the response variables were sufficiently sensitive and psychometrically reliable to detect differences.

What this adds to what is known

Two previously conducted studies that investigated this found conflicting results.

What is the implication and what should change now

Observation of school meals is an appropriate method to use in validation studies to investigate the accuracy of reports of these meals in children’s 24-hour dietary recalls.

Conclusions about 24-hour dietary recalls by fourth-grade children observed eating school meals in validation studies can be generalized to 24-hour dietary recalls by comparable but unobserved children in non-validation studies (such as national surveys, epidemiologic studies, and nutrition interventions).

Assessing the impact of measurement in validation studies is essential to generalizing the results of validation studies to research subjects for whom reference information has not been collected.

Introduction

Dietary-reporting validation studies compare reported information to reference information that, ideally, is from a method independent of the subject’s memory. Observation is the best method for validating dietary reports, and observations should occur in cafeteria-type settings familiar to subjects [1]. Because children eat meals in locations where parents are not present (e.g., at school), it is necessary to obtain dietary information from children. School-meal observations provide an excellent method to validate reports of these meals in children’s 24-hour dietary recalls [2]. Observations of children eating meals in private homes may cause substantial reactivity [3]. Reactivity is less problematic when observations occur at school [2] where children are accustomed to being watched while eating in groups [2, 4]. In most validation studies for which children provided dietary recalls without parental assistance, reference information was obtained by observing one or two school meals [5].

A goal of validation studies is to generalize conclusions to subjects in non-validation studies for whom reference information is not collected [3]. Ideally, validation methods have no effect on subjects’ reports [3, 6]. However, collecting reference information in validation studies may influence subjects’ responses or behaviors. For example, observing children eating school (or other) meals may influence what or how much children eat, children’s memories about what they ate, and/or children’s subsequent dietary recalls [5, 7]. Such influence may restrict generalizability of validation-study conclusions.

To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated the effects of school-meal observations on children’s 24-hour dietary recalls [5, 7]. In a study by Baranowski et al. [7], fourth-grade children were or were not observed eating school lunch, and provided two recalls collected back-to-back (one with child-operated software; one with a dietitian-administered interview). Baranowski et al., who defined “intrusions” as items reported in child-operated software interviews but not in dietitian-administered interviews, found that observed children averaged significantly lower on intrusions than unobserved children and concluded that school-lunch observations decrease reports of uneaten foods. However, children’s observation status was partially confounded with a bogus pipeline manipulation intended to enhance recall accuracy. (Children provided hair samples and were told “We can tell some of what you eat from a chemical analysis of your hair.”) Our assessment of the unconfounded observation-status effect showed a non-significant difference in intrusions between observed and unobserved children [5]. Furthermore, completing back-to-back recalls is similar to completing multiple interview passes in two prominent 24-hour dietary recall protocols. (One is the Nutrition Data System for Research [http://www.ncc.umn.edu/about/missionandhistory.html]; the other is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s automated multiple-pass method [http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=7710].) Multiple passes provide respondents with numerous opportunities to report additional foods, so obtaining back-to-back recalls from children may have had implications for items Baranowski et al. defined as “intrusions”.

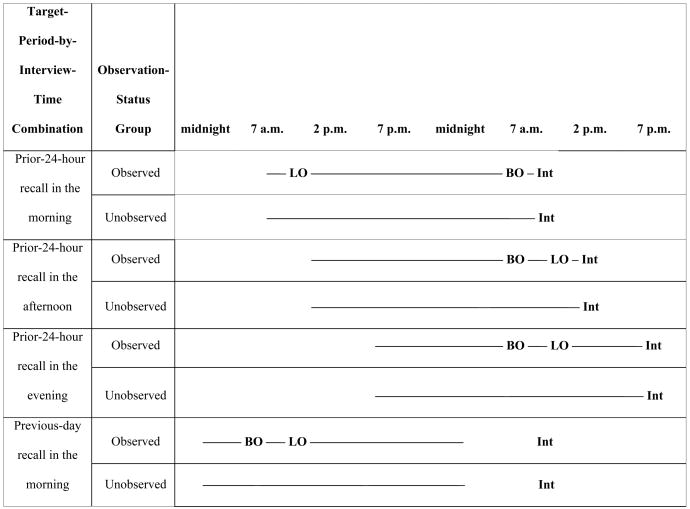

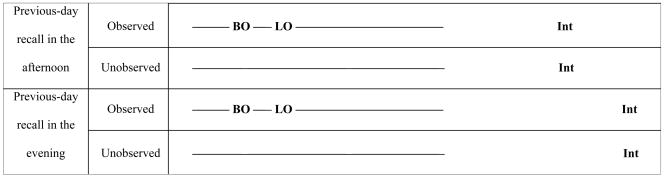

In a study with fourth-grade children who were or were not observed eating two school meals (breakfast, lunch), Smith et al. [5] used a different approach to investigate whether school-meal observations influenced children’s 24-hour dietary recalls. Each of 120 children was randomized to one of 12 conditions created by crossing two observation-status groups (observed; unobserved), two target periods (prior-24-hours; previous-day), and three interview times (morning; afternoon; evening). The Figure illustrates intake covered in recalls in these 12 conditions. For each child, five response variables were measured — interview length, meals/snacks for the target period, and, for two school meals, meal components, weighted items, and kilocalories. None of these response variables depended on observation status. However, target period affected reported intake, with more meals/snacks and longer interviews for prior-24-hour recalls than previous-day recalls, which indicated that response variables were sufficiently reliable to detect manipulations. Together, results suggested that school-meal observations did not affect fourth-grade children’s 24-hour dietary recalls, which in turn suggested, but did not guarantee, that conclusions about 24-hour dietary recalls by fourth-grade children observed eating school meals may be generalized to 24-hour dietary recalls by comparable children not observed [5].

Figure. Intake Covered in 24-Hour Dietary Recalls in 12 Conditions Created by Crossing Six Target-Period-by-Interview-Time Combinations with Two Observation-Status Groups.

The two target periods are prior 24 hours (the 24 hours immediately preceding the interview) and previous day (midnight to midnight of the day before the interview). The three interview times are morning, afternoon, and evening. The two observation-status groups are observed and unobserved. In the Figure, “BO” indicates when a school breakfast is observed; “LO” indicates when a school lunch is observed; “Int” indicates when an interview to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall is conducted; and the solid line inside cells indicates intake to be covered in that 24-hour dietary recall. Definitions for the six target-period-by-interview-time combinations are:

Prior-24-hour recall in the morning = recall about the prior-24-hour target period conducted during a morning interview time;

Prior-24-hour recall in the afternoon = recall about the prior-24-hour target period conducted during an afternoon interview time;

Prior-24-hour recall in the evening = recall about the prior-24-hour target period conducted during an evening interview time;

Previous-day recall in the morning = recall about the previous-day target period conducted during a morning interview time;

Previous-day recall in the afternoon = recall about the previous-day target period conducted during an afternoon interview time; and

Previous-day recall in the evening = recall about the previous-day target period conducted during an evening interview time.

For this article, we investigated whether school-meal observations influenced 24-hour dietary recalls in a large sample of fourth-grade children. This was the secondary aim of a study for which the primary aim was to investigate target-period and interview-time effects on children’s dietary recall accuracy. For the primary aim, children were observed eating two school meals and interviewed to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall; recall accuracy is described elsewhere [8]. For the secondary aim, additional children were interviewed to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall without having been observed eating either school meal for the target period. For this article, we investigated the statistical equivalence [9–11] of characteristics of 24-hour dietary recalls by observed and unobserved children.

Material and methods

The study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board. Written child assent and parental consent were obtained. Table 1 provides details concerning data collection and quality control methods.

TABLE 1.

Details Concerning Key Aspects of Data Collection Methods and Quality Control

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Recruitment of children | Schools were selected from 28 elementary schools in one district to obtain a sample of children with high participation in school meals. For the 2004–05, 2005–06, and 2006–07 school years, at the schools where data were collected, 84% (range: 52 to 96%), 83% (49 to 95%), and 89% (76 to 95%) of children were eligible for free or reduced-price school meals. At the beginning of each school year, researchers visited fourth-grade classes, distributed assent and consent forms, read the assent form aloud, and asked and responded to questions. Two or three days later, researchers visited again and gave prizes to children who had returned signed forms regardless of participation decisions. |

| Agreed participation rates | For the three respective school years, of the 933, 959, and 499 children invited to participate, 687 (74%), 733 (76%), and 360 (72%) agreed. For each school year of data collection, the race/sex composition of children who agreed to participate was similar to that of children who were invited to participate. |

| Age distribution requirements | For each school year, among children who had agreed to participate, those in the upper 2.5% and lower 2.5% of the age distribution as of September first were not observed and/or interviewed for data collection. |

| Usual school- meal eaters | This criterion was satisfied if a child obtained school breakfast and school lunch during (a) at least four of five practice observations at the beginning of the school year and (b) at least four of five previous observations as data collection progressed throughout the school year. |

| Limited advance knowledge | School staff and children did not know to which observation-status group (observed; unobserved) children were assigned, nor did they know in advance on which days observations and/or interviews would occur. Because we recruited more children than needed for interviews, it was difficult for children to determine who specifically was being observed and/or would be interviewed. Although any individual child was interviewed once at most, when recruited, children were told that they might be interviewed zero, one, or two times, so that being interviewed did not indicate to a child or classmates that the child was exempt from further interviews. |

| Observations | During the three respective school years, observations were conducted on Mondays through Fridays by three, six, and three researchers. Observers were trained by review of a written protocol, modeling, practice, and interobserver reliability assessment for pre-data-collection. Only children who obtained meals at school were observed. For most children, breakfast and lunch were observed on the same day; however, children randomized to prior-24-hour recalls in the morning were observed eating lunch one day and breakfast on the next day (see Figure). For an observation, a researcher observed one to three children simultaneously and used a paper form to note items and amounts eaten in servings of standard school-meal portions. Observations were conducted during regular meal periods with children seated according to their school’s typical arrangement. Entire meal periods were observed to note food trades. At least five practice observations per school, conducted at the beginning of each school year, helped familiarize children with the presence of observers. For school meals in the target period about which a child in the unobserved group was to be interviewed, no observations (or interobserver reliability assessments) were conducted in the school of that child. |

| Nametags | We made nametags for children in our study to wear during school-meal observations so that researchers could identify them. We kept the nametags in our office; when researchers went to a school to observe, they took nametags for all subjects at the school. Children became accustomed to obtaining and returning nametags immediately before and after each school-meal observation during practice observations. Children were willing to wear nametags because it was required if they wanted a chance to be interviewed (for which they were paid). During each observation, researchers marked nametag records to indicate which children obtained school meals. |

| Interobserver reliability | Throughout data collection, interobserver reliability was assessed for each pair of observers with each observer involved in at least one assessment per week. During the three respective school years, for breakfast, interobserver reliability was assessed on 33, 79, and 18 children, and mean agreement between observers to within one-fourth serving on amounts eaten was 98%, 98%, and 100%; for lunch, interobserver reliability was assessed on 48, 83, and 18 children, and mean agreement between observers to within one-fourth serving on amounts eaten was 94%, 96%, and 97%. These levels of agreement are satisfactory [2]. A child observed for a meal for interobserver reliability assessment was never interviewed about that meal. |

| Interviews | During the three respective school years, interviews were conducted on Tuesdays through Fridays by three, three, and two researchers (for a total of four different researchers) who had not conducted observations for data collection for that school year. Interviewers were trained by review of written protocols, modeling, practice interviews with fourth- grade children, and assessment of quality control for interviews conducted for practice. Morning and afternoon in- person interviews were conducted after breakfast and lunch, respectively, in private locations at children’s schools; evening telephone interviews were conducted between 6:30 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. (In a previous validation study [4], there was no significant effect of interview modality [i.e., in-person versus telephone] on fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy.) The interview protocols used forward-order (i.e., morning-to-evening) prompts and were modeled on the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) protocol (Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN); however, instead of using NDSR software during interviews, interviewers wrote information reported by children onto paper forms. Because the NDSR protocol concerns the previous-day target period, it was adapted for interviews about the prior-24-hour target period by asking those children to report intake for the interview day first, and then the previous day. Interviewers documented beginning and ending times of interviews. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed. A $20 check was mailed to each interviewed child. |

| Blinding of interviewers | Observations and interviews were conducted by different researchers. During data collection, interviewers were blinded to children’s observation status, and did not know at which schools specific meals were observed on particular days. Prior to data collection each school year, interviewers helped conduct the practice observations for initial identification of usual school-meal eaters. |

| Quality control for interviews | The quality of each interview (irrespective of observation-status group) was assessed. Both the audio recording and typed transcript were reviewed by an interviewer other than the one who conducted the interview. The reviewer completed a checklist about various aspects of the interview. A researcher (and co-author who had experience interviewing children, but did not interview for this study) and the Principal Investigator provided oversight and decided whether each interview passed or failed quality control. Of 649 interviews, 67 (46 observed group — 30 prior-24-hour recalls [12 morning, 6 afternoon, 12 evening], 16 previous-day recalls [4 morning, 6 afternoon, 6 evening]; 21 unobserved group — 10 prior-24-hour recalls [4 morning, 2 afternoon, 4 evening], 11 previous-day recalls [4 morning, 2 afternoon, 5 evening]) were excluded from analyses because they failed quality control due to interviewer errors during interviews. An additional 27 interviews (22 observed group — 13 prior-24-hour recalls [3 morning, 3 afternoon, 7 evening], 9 previous-day recalls [2 morning, 1 afternoon, 6 evening]; 5 unobserved group — 4 prior-24-hour recalls [1 morning, 3 evening], 1 previous-day recall [evening]) were excluded for other reasons (e.g., telephone problems, interviewer was assigned or used the wrong target-period-by-interview-time combination, observation errors, interview was severely interrupted due to uncontrollable circumstances). |

Data collection occurred during the 2004–05, 2005–06, and 2006–07 school years in 17, 17, and 8 schools, respectively. From participating children within the center 95% of the age distribution, children were randomly selected with the constraints that half were girls and all were usual school-meal eaters.

In the final sample of 555 children (half girls; 96% Black; mean ± standard deviation 10.1±0.79 years of age), 374 children were observed eating two school meals (breakfast, lunch) and interviewed to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall, and 181 children were interviewed to obtain a 24-hour dietary recall without having been observed eating either school meal in the target period. Assignment to observation-status group was random; within observation-status groups, children were randomized to one of six target-period-by-interview-time combinations (see Figure) with the constraint that each combination had 62 or 64 children (half girls) in the observed group, and 30 or 31 children (half girls) in the unobserved group. Also, insofar as possible, within school year and school, randomization to target-period-by-interview-time combinations within observation-status groups by sex was stratified across classes.

Observers followed a written protocol based on previously used procedures [5, 12]. Interobserver reliability was assessed using established procedures [13].

Interviewers followed written multiple-pass protocols based on previously used procedures [5, 12]. Quality control for interviews was assessed for each interview using established procedures [14].

Observation-status groups were compared on the five response variables used by Smith et al. [5] — interview length, meals/snacks for the target period, and, for two school meals, meal components, weighted items, and kilocalories. Interview length was determined by subtracting each interview’s beginning time from its ending time. Specific criteria were used to treat meals reported in 24-hour dietary recalls as school meals (Table 2, footnote §). Items reported eaten in non-zero amounts at school meals were classified by meal component (Table 2, footnote ¶) and weighted (Table 2, footnote ||). Amounts eaten were reported in servings of standard school-meal portions, quantified, and converted to kilocalories (Table 2, footnote **).

TABLE 2.

Means ± Standard Deviations for Five Response Variables from Fourth-Grade Children’s 24-Hour Dietary Recalls *

| Target period and target- period-by- interview- time combination † | Interview length (in minutes) | Number of meals/snacks reported for target period ‡ | Number of meal components reported for two school meals §, ¶ | Weighted number of items reported eaten for two school meals §,¶,|| | kilocalories reported eaten for two school meals §,** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Un-observed | Observed | Un-observed | Observed | Un-observed | Observed | Un-observed | Observed | Un-observed | |

| Prior-24- hour recalls | 19.3 ± 5.5 | 20.0 ± 5.6 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 578 ± 328 | 631 ± 336 |

| 19.5 ± 5.5 | 4.8 ±1.6 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 2.8 | 595 ± 331 | ||||||

| Prior-24- hour recalls in the morning | 19.5 ± 5.7 | 20.2 ± 6.0 | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 2.8 | 5.8 ± 2.8 | 516 ± 326 | 575 ± 307 |

| 19.7 ± 5.8 | 4.8 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 2.8 | 535 ± 319 | ||||||

| Prior-24- hour recalls in the afternoon | 18.6 ± 5.0 | 19.3 ± 5.4 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 6.1 ± 2.8 | 7.0 ± 2.6 | 611 ± 349 | 707 ± 367 |

| 18.9 ± 5.1 | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 642 ± 356 | ||||||

| Prior-24- hour recalls in the evening | 19.9 ± 5.7 | 20.5 ± 5.6 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 6.2 ± 2.7 | 607 ± 304 | 611 ± 329 |

| 20.1 ± 5.7 | 5.0 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 2.8 | 608 ± 311 | ||||||

| Previous- day recalls | 16.7 ± 4.9 | 16.2 ± 5.0 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 4.4 ± 1.6 | 3.6 ± 2.0 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 5.9 ± 3.2 | 5.3 ± 3.3 | 570 ± 354 | 536 ± 377 |

| 16.5 ± 5.0 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 3.6 ± 2.0 | 5.7 ± 3.2 | 559 ± 362 | ||||||

| Previous- day recalls in the morning | 17.5 ± 4.9 | 15.9 ± 3.8 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 5.7 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 2.8 | 541 ± 400 | 554 ± 283 |

| 17.0 ± 4.6 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 2.2 | 5.7 ± 3.4 | 545 ± 364 | ||||||

| Previous- day recalls in the afternoon | 16.1 ± 5.2 | 16.9 ± 6.3 | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 3.4 ± 1.9 | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 5.5 ± 2.9 | 4.2 ± 3.5 | 529 ± 328 | 396 ± 361 |

| 16.4 ± 5.6 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 5.0 ± 3.1 | 486 ± 343 | ||||||

| Previous- day recalls in the evening | 16.5 ± 4.7 | 15.8 ± 4.8 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | 6.5 ± 2.8 | 6.2 ± 3.3 | 636 ± 327 | 658 ± 438 |

| 16.3 ± 4.7 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 6.4 ± 3.0 | 643 ± 364 | ||||||

| Mean †† | 18.0 ± 5.4 | 18.1 ± 5.6 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 5.9 ± 3.0 | 5.8 ± 3.0 | 574 ± 341 | 583 ± 360 |

| MEAN ‡‡ | 18.0 ± 5.5 | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 5.9 ± 3.0 | 577 ± 347 | |||||

Of 555 fourth-grade children who each provided a 24-hour dietary recall, 374 children had been observed and 181 children had not been observed eating two school meals (breakfast and lunch) during the target period covered in their recall. Assignment to observation-status group (observed, unobserved) was random; within observation-status group, children were randomly assigned to one of six target-period-by-interview-time combinations (illustrated in the Figure) so that each combination in the observed group had 62 or 64 children (half girls) and each combination in the unobserved group had 30 or 31 children (half girls). No observations (or interobserver reliability assessments) were conducted in the school of a child in the unobserved group for meals that occurred during the target period about which that child was to be interviewed. Interviewers were blinded to children’s observation status.

See the Figure caption for definitions of the two target periods and six target-period-by-interview-time combinations. Morning and afternoon in-person interviews were conducted in private locations at children’s schools after school breakfast and school lunch, respectively; evening telephone interviews were conducted between 6:30 p.m. and 9:00 p.m.

Number of meals/snacks reported eaten by the child at school, home, and elsewhere during the target period about which the child was to report. Reported meals and/or snacks that consisted only of water were excluded from analyses.

School meals were breakfast and lunch prepared by school food service and eaten at school during the target period about which the child was to report. Meals in children’s 24-hour dietary recalls were treated as referring to school meals if children identified school as the location, referred to breakfast as school breakfast or breakfast, referred to lunch as school lunch or lunch, and reported mealtimes to within one hour of scheduled mealtimes. Of 374 children in the observed group, each of 39 children (10%; 18 girls) failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals — 14 prior-24-hour recalls (4 morning, 4 afternoon, 6 evening) and 25 previous-day recalls (14 morning, 8 afternoon, 3 evening). Of 181 children in the unobserved group, each of 22 children (12%; 11 girls) failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals — 5 prior-24-hour recalls (2 morning, 1 afternoon, 2 evening) and 17 previous-day recalls (4 morning, 10 afternoon, 3 evening).

Items reported eaten in non-zero amounts at school meals were classified as one of ten meal components (beverage, bread/grain, breakfast meat, combination entrée, condiment, dessert, entrée, fruit, miscellaneous, vegetable). For example, a child who reported eating non-zero amounts of a biscuit, jelly, and chocolate milk at school breakfast, and spaghetti, green beans, strawberry milk, and vanilla ice cream at school lunch reported a total of six unique meal components (bread/cereal, condiment, beverage, combination entrée, vegetable, and dessert).

Items reported eaten in non-zero amounts at school meals were weighted by meal component with combination entrée (e.g., spaghetti) = 2, condiments (e.g., jelly) = 0.33, and all remaining meal components = 1.0. For example, a child who reported eating non-zero amounts of a biscuit, jelly, and chocolate milk at school breakfast, and spaghetti, green beans, strawberry milk, and vanilla ice cream at school lunch reported a total of 7.33 weighted items.

Amounts eaten were reported in servings of standard school-meal portions and quantified as none = 0.00, taste = 0.10, little bit = 0.25, half = 0.50, most = 0.75, all = 1.00, and the actual number of servings for more than one serving. Standard serving sizes for school meal items were used to obtain per-serving information about kilocalories from the Nutrition System for Research (NDSR) database; for items not in NDSR, kilocalorie information from the school district’s nutrition program was used. The quantified serving of each item reported eaten in a non-zero amount at a school meal was multiplied by the per-serving kilocalorie value, and then these values were summed across the two school meals for each child.

Means and standard deviations for each response variable by observation-status group (averaged across target period and interview time).

Means and standard deviations for each response variable (averaged across all interviews).

To investigate statistical equivalence [9–11] between 24-hour dietary recalls by observed and unobserved children, for each response variable, we conducted a naïve (unadjusted) equivalence test to investigate the effect of observation-status group. Each equivalence test was a pair of one-sided two-sample t-tests based on a tolerance δ>0 denoting the smallest nonnegligible difference:

Rejecting both null hypotheses leads one to accept the alternative hypotheses

which implies equivalence (on average) of observation-status groups. We used Cohen’s definition of a small effect δ=(0.20)sobserved [15]. By convention, results of equivalence tests are summarized using the larger P value from the pair of two-sample t-tests.

Subsequently, each response variable was modeled using analysis of variance (for interview length, weighted items, and kilocalories) or Poisson regression (for meals/snacks and meal components) with observation-status group, target period, interview time, target-period-by-interview-time interaction, observation-status-group-by-target-period interaction, observation-status-group-by-interview-time interaction, observation-status-group-by-target-period-by-interview-time interaction, sex, interviewer, and school year in the model. For each response variable, after fitting a full model, non-significant (P>0.05) terms were removed, and an equivalence test on adjusted means was conducted to assess differences for observation-status groups.

Analyses used Stata 10.0 (Stata, Inc., College Station, TX) and SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A significance criterion of 0.05 was used; post hoc pairwise comparisons were interpreted using Bonferroni adjustments.

Results

Thirty-nine of 374 observed children (10%) and 22 of 181 unobserved children (12%) failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals (Table 2, footnote §). Because in practice one would not know whether interviewed children had eaten particular meals, children who failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals were included in analyses by using zeroes for their three response variables concerning two school meals — meal components, weighted items, and kilocalories [5]. Analyses with and without these 61 children essentially agreed; we indicate the four discrepant results, none of which involved observation-status group.

Table 2 shows means and standard deviations for response variables for each target period (by observation-status group and averaged across observation-status group), each target-period-by-interview-time combination (by observation-status group and averaged across observation-status group), each observation-status group, and averaged across all interviews.

For each response variable, naïve equivalence tests rejected hypotheses that observation-status groups differed (P values <0.0083). Thus, we concluded that means of observation-status groups were equivalent, indicating that school-meal observations did not influence children’s 24-hour dietary recalls.

For interview length, there was a target-period effect (P<0.0001), with interviews 3 minutes longer on average for prior-24-hour recalls than previous-day recalls (Table 2). There was an interviewer effect (P=0.0159); mean interview length for the four interviewers ranged from 17.5 to 18.8 minutes, but no post hoc pairwise comparison was significant. There was a school-year effect (P=0.0002); means for the first, second, and third school years were 17.7, 17.6, and 20.1 minutes, respectively, and post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that interviews were longer for the third than first (P<0.0001) and second school years (P<0.0001).

For weighted items for two school meals, only the target-period-by-interview-time interaction was significant (P=0.0110). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that 1.3 fewer weighted items on average were reported for two school meals for previous-day recalls in the afternoon than prior-24-hour recalls in the afternoon (P=0.0031) and previous-day recalls in the evening (P=0.0022) [Table 2]. When children who failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals were excluded from analyses, two results were discrepant from those in this paragraph. First, there was a school-year effect (P=0.0402), with weighted items for two school meals ranging on average from 6.3 to 6.9 for the three school years, but no pairwise comparison was significant. Second, although there was a significant target-period-by-interview-time interaction (P=0.0155), post hoc pairwise comparisons were discrepant, indicating that average numbers of weighted items for two school meals differed between prior-24-hour recalls in the morning (5.8) and both prior-24-hour recalls in the evening (6.9; P=0.0019) and previous-day recalls in the morning (7.0; P=0.0015).

For kilocalories for two school meals, only the target-period-by-interview-time interaction was significant (P=0.0047). Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that 156 fewer kilocalories on average were reported for two school meals for previous-day recalls in the afternoon than both prior-24-hour recalls in the afternoon (P=0.0020) and previous-day recalls in the evening (P=0.0019) [Table 2]. When children who failed to meet criteria for reporting both school meals were excluded from analyses, two results were discrepant from those in this paragraph. First, there was a sex effect (P=0.0096); on average, more kilocalories were reported by boys (681) than girls (615). Second, although there was a significant target-period-by-interview-time interaction (P=0.0332), with average kilocalories reported for the two school meals ranging from 573 to 687 across the six target-period-by-interview-time combinations, no post hoc pairwise comparison was significant.

For meals and snacks for the target period, and for meal components for two school meals, no significant effects or interactions were found.

For no response variable was there a significant effect of observation-status group, or a significant interaction of observation-status group with any other effect.

For adjusted equivalence tests, all P values were <0.0016. Thus, results of adjusted and naïve equivalence tests were consistent; for each response variable, we rejected the pair of null hypotheses and concluded that observation-status group means were equivalent.

Discussion

Results are compelling that our implementation of school-meal observations did not influence fourth-grade children’s 24-hour dietary recalls. Specifically, for each of five response variables, in naïve and adjusted equivalence tests, we rejected hypotheses that observation-status groups differed, which allowed us to conclude that means for the observation-status groups were statistically equivalent. Furthermore, results concerning a target-period effect on interview length and a target-period-by-interview-time interaction on weighted items and kilocalories indicated that response variables were sufficiently sensitive and psychometrically reliable to detect differences, providing added support for the conclusion that school-meal observations did not affect fourth-grade children’s 24-hour dietary recalls [3, 6]. These results are similar to those from the Smith et al. study [5] for which the design was comparable but the sample was too small to permit equivalence testing.

Our conclusion differs from that of Baranowski et al. [7], but our approach differed. Smith [3] noted that when investigating the effect on subjects’ reports of collecting reference information, such information is not available for one group; thus, groups cannot be compared on accuracy measures, and other measures must be used. This methodology is appropriate for assessing the impact of school-meal observations on children’s 24-hour dietary recalls.

Investigation of the effect of collecting reference information, and establishing statistical equivalence to “no-reference-method” groups (if possible), would be appropriate in other endpoint validation studies [3, 5, 6]. For example, studies to validate self-report questionnaires about taking medication may use electronic monitors that record every opening of medication containers [e.g., 16], and studies to validate self-report questionnaires about physical activity may use accelerometers that record motion [e.g., 17]. To determine whether validation methods of electronic monitors and accelerometers affect subjects’ questionnaire responses, such studies could include a no-reference-method group of subjects who do not use electronic monitors or accelerometers but do complete questionnaires.

Limitations included homogeneity in children’s race/ethnicity, grade level, and geographical location. We did not investigate the effect of being observed eating meals at home due to reactivity.

Strengths included the large sample, which allowed us to conduct conservative equivalence tests (using Cohen’s definition of a small effect [15]) to compare observation-status groups. The effect of being observed eating two school meals was investigated. Interviewers were blinded to children’s observation status. Children were usual school-meal eaters. Quality control methods were rigorous.

These results have important implications. Children will likely continue to provide thousands of 24-hour dietary recalls each year for national surveys [e.g., 18] and interventions [e.g., 19], and to assess the relative validity of food frequency questionnaires [e.g., 20]. There is a crucial need for validation studies to improve children’s dietary recall accuracy to enhance dietary-data quality in non-validation studies that utilize children’s dietary recalls. Our findings justify using our implementation of school-meal observations in validation studies to investigate children’s accuracy for these meals in 24-hour dietary recalls. Conclusions about 24-hour dietary recalls by fourth-grade children observed eating school meals in validation studies can be generalized to 24-hour dietary recalls by comparable but unobserved children in non-validation studies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 HL074358 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health; Suzanne D. Baxter was Principal Investigator. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

The authors appreciate the cooperation of children, faculty, and staff of elementary schools, and staff of Student Nutrition Services, of the Richland One School District (Columbia, SC).

The authors thank Elizabeth J. Herron for her comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

A brief podium presentation with some results in this article was given at the American Dietetic Association’s Food and Nutrition Conference and Expo held in Chicago, Illinois in October, 2008.

The authors appreciate the contribution to this work of Amy F. Joye, MS, RD, who was Project Director for this grant until she suffered severe brain damage due to a medical tragedy. The Amy Joye Research Fund is being established through the American Dietetic Association Foundation to award nutrition research grants on an annual basis in Amy’s honor.

References

- 1.Mertz W. Food intake measurements: Is there a “gold standard”? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1992;92:1463–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simons-Morton BG, Baranowski T. Observation in assessment of children’s dietary practices. Journal of School Health. 1991;61(5):204–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1991.tb06012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AF. Concerning the suitability of recordkeeping for validating and generalizing about reports of health-related information. Review of General Psychology. 1999;3(2):133–50. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Litaker MS, Guinn CH, Frye FHA, Baglio ML, et al. Accuracy of fourth-graders’ dietary recalls of school breakfast and school lunch validated with observations: In-person versus telephone interviews. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2003;35(3):124–34. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AF, Baxter SD, Hardin JW, Guinn CH, Royer JA, Litaker MS. Validation-study conclusions from dietary reports by fourth-grade children observed eating school meals are generalisable to dietary reports by comparable children not observed. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10:1057–66. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007683888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb EJ, Campbell DT, Schwartz RD, Sechrest L. Unobtrusive Measures: Nonreactive Research in the Social Sciences. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranowski T, Islam N, Baranowski J, Cullen KW, Myres D, Marsh T, et al. The Food Intake Recording Software System is valid among fourth-grade children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102:380–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter SD, Hardin JW, Guinn CH, Royer JA, Mackelprang AJ, Smith AF. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. Fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy is influenced by retention interval (target period and interview time) (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers JL, Howard KI, Vessey JT. Using significance tests to evaluate equivalence between two experimental groups. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):553–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seaman MA, Serlin RC. Equivalence confidence intervals for two-group comparisons of means. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):403–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyron WW. Evaluating statistical difference, equivalence, and indeterminacy using inferential confidence intervals: An integrated alternative method of conducting null hypothesis statistical tests. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(4):371–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baxter SD, Smith AF, Litaker MS, Guinn CH, Shaffer NM, Baglio ML, et al. Recency affects reporting accuracy of children’s dietary recalls. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;14:385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baglio ML, Baxter SD, Guinn CH, Thompson WO, Shaffer NM, Frye FHA. Assessment of interobserver reliability in nutrition studies that use direct observation of school meals. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:1385–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaffer NM, Baxter SD, Thompson WO, Baglio ML, Guinn CH, Frye FHA. Quality control for interviews to obtain dietary recalls from children for research studies. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:1577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–9. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeller A, Schroeder K, Peters TJ. An adherence self-report questionnaire facilitated the differentiation between nonadherence and nonresponse to antihypertensive treatment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61:282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Saris WHM, Kromhout D. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56:1163–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon A, Fox MK. School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study-III, Summary of Findings. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research, Nutrition, and Analysis; 2007. [accessed October 11, 2008]. Available from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/oane/MENU/Published/CNP/FILES/SNDAIII-SummaryofFindings.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luepker RV, Perry CL, McKinlay SM, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, et al. Outcomes of a field trial to improve children’s dietary patterns and physical activity: The Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) JAMA. 1996;275(10):768–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530340032026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field AE, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL, Cheung L, Rockett H, Fox MK, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire among fourth to seventh grade inner-city school children: Implications of age and day-to-day variation in dietary intake. Public Health Nutrition. 1999;2(3):293–300. doi: 10.1017/s1368980099000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]