Abstract

Background

Discrepancies between patient wishes and end-of-life treatment decisions have been documented, and the determinants of end-of-life treatment decisions are not well understood. Our objective was to understand hospital staff perceptions of the role of acute care hospital medical doctors in end-of-life treatment intensity.

Methods

In 11 Pennsylvania hospitals, we completed 108 audiotaped semistructured interviews with key informants involved in decision making or discharge planning. Using grounded theory, we qualitatively analyzed transcripts using constant comparison to identify factors affecting end-of-life treatment decisions.

Results

A predominant theme identified was that end-of-life treatment intensity depends on the doctor. Communication with patients and families and collaboration with other care team members also were reported to vary, contributing to treatment variation. Informants attributed physician variation to individual beliefs and attitudes regarding the end-of-life (religion and culture, determination of when a patient is dying, quality-of-life determination, and fear of failing) and to socialization by and interaction with the health care system (training, role perception, experience, and response to incentives).

Conclusions

When end-of-life treatment depends on the doctor, patient and family preferences may be neglected. Targeted interventions may reduce variability and align end-of-life treatment with patient wishes.

Keywords: terminal care, practice variation, decision making, qualitative research

BACKGROUND

Mismatches between the health care that seriously ill patients prefer and the care that they receive have been well documented (1–5), and the social experiment with the living will has not mitigated this problem.(6) Further, the intensity of inpatient treatment for U.S. Medicare beneficiaries in their last year of life, as measured by admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and the use of such life-sustaining procedures as mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, and feeding tubes, has increased steadily since the 1980s despite a secular increase in the use of hospice and decrease in deaths occurring in the acute care hospital.(7)

The influences upon decisions to use, withhold, or withdraw intensive treatments near the end of life are not well understood. At the population-level, previous studies have implicated health care system factors, including hospital bed and physician supply in end-of-life treatment patterns (1, 8). However, individual physicians are ultimately the drivers of these decisions, both through decisions to hospitalize (9), and actions (e.g., intubation and resuscitation) or orders (e.g., to terminally wean) once hospitalized. Highlighting physicians’ centrality, a multicenter study found that, rather than age or the severity of the illness and organ dysfunction, among the strongest determinants of the withdrawal of ventilation in critically ill patients in anticipation of death in the ICU were the physician’s perception that the patient preferred not to use life support and the physician’s predictions of a low likelihood of survival in the intensive care unit and a high likelihood of poor cognitive function for the patient.(10) More recently, a single center study reported large, physician-attributable differences in resources used to manage critically ill patients, without any associated differences in mortality or length of stay.(11)

As part of a larger project investigating the organizational determinants of variation in treatment intensity at the end of life, we qualitatively analyzed semi-structured interviews with clinical and administrative staff at 11 Pennsylvania (PA) hospitals to explore hospital staff members’ perceptions of physicians’ role in end-of-life treatment intensity and their attributions of practice variation among physicians.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

We conducted 2-day site visits to 11 PA hospitals between March and August of 2004. We limited the hospital site visits to one state to minimize differences in treatment patterns attributable to state-related legal, regulatory, and financing influences. Within PA, we purposively sampled a heterogenous group of hospitals among all non-federal acute-care institutions to maximize variance in geographic location, size, teaching affiliation, and ICU and intensive procedure use among terminal admissions. Details of the sampling procedure have been previously described (12).

We contacted the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 20 hospitals to obtain authorization to conduct a site visit and contact staff members for interview. Of 20 sampled hospitals 13 hospitals agreed to participate, and we completed 11 site visits. Thematic saturation had been achieved before the 11th site visit.

The site visits included observation on morning ICU rounds and 60-minute interviews with the following key informants: chief nursing officer, the director of case management, the physician director of the emergency department (ED), the physician director of the ICU, the ICU nurse manager, the chief of surgery, two high-volume physicians (i.e., physicians identified by the administration as admitting a high volume of patients 65 and older), a bedside ICU nurse, an ICU social worker, an oncology social worker, the director of pastoral care, the director of palliative care (if present), and the chair of the ethics committee. These informants were selected based upon the expectation that they would know the most about end-of-life decision making in the hospital, as suggested by focus group participants with a variety of administrative and clinical staff from 3 University of Pittsburgh hospitals. At each hospital, all scheduled interviews were conducted over 1–2 days, without respect to considerations of within-hospital thematic saturation.

Data Collection

One investigator (AEB), blinded to each hospital’s intensity, collected data in the form of hand-written field notes during observed ICU rounds at 7 of 11 hospitals (2 hospitals did not have rounds, 2 hospitals refused access) and audiotaped semi-structured interviews with 129 key informants at 11 hospitals (range, 7–15 per hospital). Each semi-structured interview began with an introduction to the study in which “intensive” treatment was defined as admission to the intensive care unit, and the use of life-sustaining procedures, including mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, hemodynamic support, blood transfusions, enteral and parenteral nutrition, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Interviews began with the “grand tour” question: “Please tell me about the most recent case of a patient over the age of 65 who died in this hospital and in whose care you were directly involved.” Probes and follow-up questions were employed to elicit information regarding institutional, individual, and community norms regarding end-of-life care (Protocol available upon request). At the end of the interview, each participant completed a brief survey that included questions regarding professional and personal demographics. After each site visit, AEB typed handwritten field notes and a professional transcriptionist transcribed interview audiotapes.

Data Analysis

Using constant comparison, two members of the research team (AEB, KLR) reviewed the field notes to identify key themes.(13–16) Among these themes was the description of variation in practice within the hospital, with many informants reporting that a patient’s end-of-life treatment intensity “depends on the doctor.”

After identification of the major theme in the field notes that treatment intensity “depends on the doctor,” we imported all interview transcripts into ATLAS.ti (Atlas.ti v5.0, Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). ATLAS.ti was used to facilitate the coding of transcript segments related to the major theme and the development of memos to summarize the interpretation of each transcript segment for sub-theme development. Two members of the research team (AEB, MRL) independently reviewed groups of transcripts representing a spectrum of informant types (e.g., nurse, physician, chaplain) to develop criteria for “depends on the doctor” transcript segments. They continued to review groups of transcripts and to refine the criteria until there was 100% agreement in selected transcript segments. We selected all segments in which informants described variation in end-of-life treatment intensity between individual doctors or between groups of doctors (eg, by specialty), segments in which individual physicians described their individual practice (often in contrast to others’ practice), or segments in which informants ascribed attributions to these variations. End-of-life treatment intensity was defined both as explicit discussions of the use, withholding, or withdrawal of particular therapies (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation and hemodynamic support, mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, parenteral or enteral feeding, intravenous hydration, chemotherapy, surgery, terminal sedation) as well as implicit references to variation in “intensity,” “aggressiveness,” perceptions of “futility,” and willingness to “give up” versus “keep pushing.”

One member of the research team (MRL) then reread all 98 transcripts identified all “depends on the doctor” segments, and created an associated memo summarizing segment interpretation. The entire research team, which also included a palliative care physician (RMA) and a medical sociologist (KLR), met regularly during analysis to review the “depends on the doctor” segments and iteratively revise the framework and criteria for domains, dimensions, and attributions of the “depends on the doctor” theme. An analytic audit trail was maintained in a comprehensive book of sub-themes containing direct quotes, memos of interpretation, and dated journal entries describing the evolution of the paper’s framework.

To assess inter-rater reliability, we randomly selected 2 transcripts from each of the 11 hospitals. The primary coder (MRL) and interviewer (AEB) read and discussed each “depends on the doctor” segment and its associated memo of interpretation. Based upon review of 90 “depends on the doctor” segments from 22 transcripts, we found an inter-rater agreement rate of 88% (79 of 90 text units) for the segment meeting inclusion criteria, and of 97% (77 of 79 text units) for the segment being interpreted consistently with the coding scheme. In addition to assessing inter-rater reliability, we used several additional techniques to ensure that data analysis was systematic and verifiable, as commonly recommended by experts in qualitative research.(17) These included consistent use of the semi-structured interview guide, audiotaping and independent professional preparation of the transcripts, standardized coding and analysis of the data by a multidisciplinary team, and the creation of an audit trail to document analytic decisions.

Human Subjects and Role of the Sponsor

The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved the study, exempting it from the requirement for written informed consent. One participating hospital sought and obtained approval by its own IRB. The National Institute on Aging had no role in the study design, execution, data analysis, or drafting of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Hospitals

Detailed characteristics of the 11 study hospitals drawn from 2004 Pennsylvania hospital discharge data have been previously reported(18). Briefly, of the 11 hospitals, 4 (36.4%) were located in large cities, 3 in medium-sized cities, 2 in small towns, and 2 in rural areas. While 5 (45.5%) were major teaching hospitals, 4 were minor teaching hospitals and 2 had no residency programs. The mean number of hospital beds was 417 (range, 104–761 beds). Treatment intensity among terminal admissions in 2004 for patients aged 65 years or older varied among these hospitals, with a range of 38.2% to 84.4% of patients admitted to the ICU, 13.7% to 41.4% receiving mechanical ventilation, and 0% to 9.2% receiving hemodialysis. Based upon hospital interviews, we found hospital staffing models ranging from no use of hospitalists (physicians specialized in treating inpatients), to attendings from admitting physician groups acting as their practice’s hospitalist on a rotating basis, to hospital-employed hospitalists.

Informants

From among 129 total interviews, 108 were available for textual coding and analysis from 98 transcripts (10 interviews conducted with 2 participants simultaneously). Reasons for non-transcription include non-permission to audiotape and audiotape malfunction. Of these 108 participants, 45% were male, and the majority were white (97%). Participants had been working in their profession for a mean of 19.6 years (range, 1–45 years); 41% were physicians, 42% were nurses, and 9% were social workers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Informants (N=108).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Male, % | 44 |

| Race | |

| White, % | 97 |

| African American, % | 2 |

| Other, % | 1 |

| Frequency of Religious Service Attendance | |

| More than weekly, % | 10 |

| About once weekly, % | 35 |

| About once monthly, % | 27 |

| About once yearly, % | 15 |

| Less than once yearly, % | 5 |

| Never, % | 8 |

| Professional degree | |

| MD or DO, % | 41 |

| RN or NP, % | 42 |

| LCSW, % | 9 |

| Other, % | 9 |

| Years in practice, mean (range) | 19.6 (1–45) |

| Years at current hospital, mean (range) | 14.8 (1–46) |

| Primary Job Function | |

| Clinical care, % | 50 |

| General social work, % | 8 |

| Case management, % | 8 |

| Management/supervision, % | 23 |

| Pastoral care, % | 4 |

| Other administrative, % | 6 |

| Other non-administrative, % | 2 |

| Primary Place of work | |

| Emergency department, % | 10 |

| Intensive care unit (ICU), % | 31 |

| Oncology unit, % | 2 |

| Throughout the hospital, % | 32 |

| Palliative care or hospice, % | 2 |

| Surgery or operating room, % | 4 |

| Administrative offices, % | 11 |

| Other, % | 7 |

| Number of patients cared for in the last month who died, mean (range) | 5.8 (0–40) |

| Has experienced the death of a loved one in a hospital, % | 74 |

| Has experienced the death of a loved one in an ICU, % | 44 |

MD – Medical Degree

DO – Doctor of Osteopathy

RN – Registered Nurse

NP – Nurse Practitioner

LCSW – Licensed Clinical Social Worker

Text Segments

A total of 288 “depends on the doctor” segments were identified in the 98 transcripts reviewed, with a mean of 2.9 (range, 0–10) “depends on the doctor” segments per transcript. The mean number of “depends on the doctor” segments per transcript by hospital ranged from 2.0 for Hospital F to 5.1 for Hospital I (Table 2). The mean number of “depends on the doctor” segments per transcript by interviewee type ranged from 2.5 for non-clinical staff to 2.9 for nurses, with the mean for physicians of 3.2 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of informants and “depends on the doctor” segments by hospital.

| DOD Segments |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | Transcribed interviews (N=98) | Informants (N=108) | Total (N=288) | Mean | Min | Max |

| A | 8 | 8 | 19 | 2.4 | 1 | 4 |

| B | 9 | 12 | 30 | 3.3 | 1 | 6 |

| C | 5 | 5 | 19 | 3.8 | 2 | 6 |

| D | 13 | 14 | 32 | 2.5 | 0 | 5 |

| E | 10 | 11 | 28 | 2.8 | 1 | 5 |

| F | 8 | 8 | 16 | 2.0 | 0 | 6 |

| G | 9 | 10 | 28 | 3.1 | 0 | 8 |

| H | 12 | 12 | 28 | 2.3 | 1 | 5 |

| I | 8 | 11 | 41 | 5.1 | 0 | 10 |

| J | 6 | 6 | 17 | 2.8 | 2 | 4 |

| K | 10 | 10 | 30 | 3.0 | 0 | 6 |

Table 3.

Distribution of informants and “depends on the doctor” segments by interviewee type.

| DOD Segments |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee type* | Interviews (N=98) | Informants (N=108) | Total | Mean | Min | Max |

| Doctor | 42 | 43 | 135 | 3.2 | 0 | |

| Nurse | 33 | 39 | 95 | 2.9 | 0 | |

| Non-clinical staff‡ | 23 | 26 | 58 | 2.5 | 0 | |

Classified by role function rather than professional degree; 44 informants had an RN degree, 5 of whom worked as hospital administrators only; 43 informants had an MD or DO, 1 of whom worked as a hospital administrator only.

Includes social workers, chaplains, and hospital administrators

Behaviors that “Depend on the Doctor”

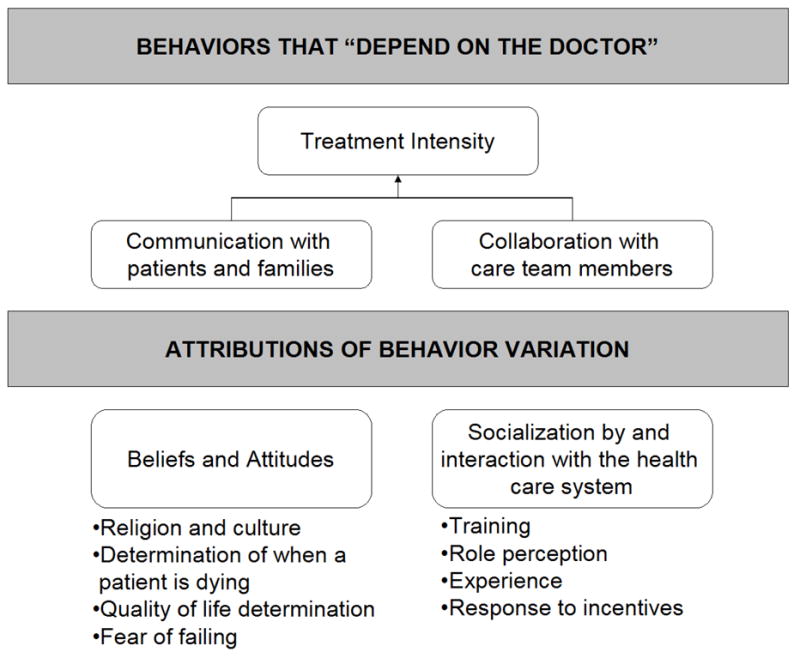

Three end-of-life behaviors were identified as depending on the doctor: 1) end-of-life treatment intensity; 2) communication with patients/families; and 3) collaboration with care team members (Figure). We provide examples of statements made by informants supporting these results in the Box.

Figure. Conceptual “depends on the doctor” model.

The central behavior identified by informants as varying by physicians was treatment intensity at end-of-life. Two other behaviors, communication with patients/families and collaboration with care team members, were also found to vary by physician, and are directly associated with treatment intensity. Informants attributed physician variability to beliefs and attitudes and socialization by and interaction with the health care system.

End-of-Life Treatment Intensity

When discussing end-of-life treatment intensity, we found that informants regularly identified behavioral differences between doctors as a key factor in explaining a patient’s treatment. Informants described a broad spectrum of physician treatment intensity, often using the term “aggressiveness” to do so. In providing examples, informants commonly identified specific individuals, or types of physicians, who treated patients more intensively than was the norm.

Parallel to treatment intensity is willingness to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Informants reported variation in the willingness to withhold or withdraw several specific treatments, including: cardiopulmonary resuscitation and hemodynamic support, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, enteral and parenteral feeding, intravenous hydration, chemotherapy, and surgical procedures. Furthermore, informants reported variation in physician comfort level with prescribing high dose pain medications. Informants also reported variation among physicians in site of care decisions that are implicitly tied to intensity of treatment at the end of life, such as admission to the ICU or referral to hospice.

Communication with patients/families

When trying to explain variation in physicians’ treatment intensity, informants commonly mentioned variation in the quality of physicians’ communication with patients/families. Variation also was noted in how directive physicians are in these conversations. The three specific end-of-life communication topics identified often and discussed in more detail below were: delivering prognosis, goals of care discussions, and code status discussions.

Delivering Prognosis

Informants reported marked variability in the degree to which physicians are forthcoming to patients and families about prognoses. Some physicians are up-front and frank with patients and families, while others are less direct in their discussions of expected treatment benefit and life expectancy.

Goals of Care Discussions

Informants indicated that physicians vary in their use of goals of care as an approach to end-of-life discussions. This included both whether goals of care are used to frame conversations at all, and, if so, the timing of these discussions during the course of an admission.

Code Status Discussions

Informants reported that code status discussions vary by physician. This variation existed even in the context of mandatory documentation on standardized forms, with some doctors going through the form item by item asking the patient whether or not they want each specific treatment listed, while another set of doctors approach the conversation from a broader perspective, and then check off items that are consistent with the patient’s more broadly stated goals and preferences.

Collaboration with care team members

Another behavior that was reported to be intricately intertwined with physicians’ treatment intensity was their variation in receptivity to input from other care team members. Most frequently this was discussed with respect to nursing input, with some physicians described as seeking out information and suggestions from nursing staff, others being willing to hear input (though note seeking it out), and others eschewing nursing input, seeing instead a nurse’s role as someone to carry out “doctors’ orders”. Willingness to collaborate with other physicians was also noted to vary. Most frequently discussed was variation in willingness to consult a palliative care service. Emergency department staff reported variation in primary care and nursing home physicians’ to call explaining patient wishes prior to ED transfer.

Attributions of Physician Behavior Variation

Key physician attributes identified by informants as central to such variation included: 1) their beliefs and attitudes; and 2) socialization by and interaction with the health care system (Figure). We provide examples of statements made by informants supporting these results in the Box.

Beliefs and attitudes

Informants commonly reported that some physicians interject their own values and beliefs into a patient’s situation as opposed to eliciting or respecting the patient’s values and beliefs. We have categorized these beliefs and attitudes in four areas discussed below: religion and culture, determination of when a patient is dying, consideration and determination of quality of life, and fear of failing.

Religion and culture

Informants felt that physicians’ religious and cultural background impact their decision making in end-of-life care. Different physicians, like patients, interpreted the tenets of the same religion differently. On the one hand, there was a Catholic physician who said that it was “against his religion” to withdraw care from a patient at the family’s urging. On the other hand, being Catholic was felt to facilitate withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment for dying patients because Catholics “believe in eternal life.”

Determination of when a patient is dying and implications for treatment

Informants described differences in physicians’ beliefs as to when a patient’s condition is terminal and warrants employment of an advance directive or a discussion, absent an advance directive, of withdrawing or withholding treatment. This variation included the scope of the determination (e.g., do you assess the terminal nature, or “reversibility” of the acute event, like pneumonia, or the chronic underlying condition, like end-stage dementia), the interpretation of the “meaning” of particular treatments (e.g., whether antibiotics for the pneumonia are a “life-prolonging” or “palliative”), the quantitative prognosis, even given a consistent scope (e.g., probability of survival to discharge), the threshold for futility (e.g., what probability of survival is low enough to consider withholding or withdrawal of treatment), and the treatment trials required before conceding death. Some of these differences lead to conflict between treating physicians. For example, one nurse described an anecdote of an attending who reversed a family’s decision of moving to comfort measures that had been made with a different attending.

Quality-of-life determination

Informants reported variation in physician tendency to invoke quality of life at all in decision making; instead focusing on survival to discharge. Among physicians who were willing to invoke quality of life, informants noted significant variation in the criteria for quality of life between physicians, leading to different recommendations for withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments. Additionally, informants reported incidents where the physicians’ perspectives on quality of life conflicted with those of the patient or family, resulting in treatment that was in conflict with patient/family preferences.

Fear of failing

Many informants felt that some physicians were reluctant to withhold/withdraw care and move to comfort measures because they perceived death as a failure. Fear of failure was a particularly common attribution of surgeons as patients sometimes suffer life-threatening complications as a result of surgery.

Socialization by and interaction with the health care system

Informants also frequently attributed variations in physician behavior to factors that were acquired through education, training, and practice, rather than being personally intrinsic to the physician. We have categorized these into training, role perceptions, experience, and incentives.

Training

Training was a common explanation for why some physicians are more or less likely to address end-of-life situations and treat with more intensity. When considering physicians who treat less intensively, informants commonly reported that these physicians had completed training more recently during an era in which hospice, and end-of-life communication skills were emphasized in medical school and residency. Informants reported specialty stereotypes to explain physician variation in end-of-life treatment; however, stereotypes were not uniform. The most frequent stereotypes involved surgeons, oncologists, intensivists, and hospitalists. Many informants reported that surgeons were most reluctant to address end-of-life situations, although several surgeons argued that medical subspecialists were a larger source of the problem. Perceptions of oncologists’ were mixed. While many indicated oncologists were believed likely to address end-of-life issues, others attributed to oncologists an unwillingness to move from cure to comfort. However, informants consistently reported that intensivists and hospitalists were more likely to consider withdrawing or withholding care than other specialists; however, some did caution that they might make that decision too soon.

Role perceptions

Physician perception of their role was a common explanation of behavior that “depends on the doctor. Specifically, doctors were believed to have certain “jobs,” like advancing technology or saving lives; providing palliation is rarely owned as part of their “job.” Physicians who consult palliative care providers were frequently reported to “hand off” care completely, rather than stay involved as they might when consulting a cardiologist or endocrinologist, because they feel they no longer have a role because curative therapy has been abandoned. Many emergency department physicians felt that obtaining goals of care and code status were the domain of the family practitioner or intensivist. Some felt that end-of-life discussions with patients and families required time and emotional capital that are not available in emergency department interactions. Though clearly the minority opinion, emergency department physicians from three separate hospitals indicated that they did feel that addressing patient wishes was part of their role.

Experience

Informants felt that more experience with death and dying, and with the limitations of therapy, resulted in greater willingness to withhold/withdraw life-sustaining treatments and in better communication skills. Experience was conveyed as that which accumulates with time (e.g., age) and with volume of exposure to dying patients (e.g., hospitalists and intensivists). A handful of informants offered conflicting perspectives, indicating that younger doctors or those who see primarily sick inpatients may “give up too soon” because they have less experience seeing patients recover.

Response to Incentives

Informants indicated incentives and disincentives impact treatment intensity at the end of life. Many informants indicated that variation in physicians’ fear of malpractice contributed to differences in their use of life-sustaining treatments and intravenous narcotics for palliation. Informants in fee-for-service settings additionally attributed some physicians’ tendency to continue “futile” treatment to their desire for financial gain.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative analysis of transcripts of semi-structured interviews with 108 staff members from 11 PA hospitals we discerned a dominant belief that the intensity of inpatient treatment for chronically ill elders who may be near the end of life depends on the treating physician. Specifically, the tendency to use life-sustaining treatments, to withhold those treatments, and to refer to hospice/palliative care were reported as differing among individual physicians and between specialties. Participants also identified other behaviors that vary by physician and which have direct implications for intensity of treatment, including communication skills and collaboration with other care providers. The causes of these variations were attributed to intrinsic characteristics – such as religious beliefs, beliefs about when a patient is “dying,” beliefs about quality of life, and tendency to personalize patients’ deaths – and extrinsic forces – such as training, role norms, experience, and incentives.

Clinician readers may recognize the veracity of these findings based upon their own experiences. If the use of life-sustaining treatments depends on the doctor, then they do not – as they ought – depend on patient and family preferences. The hypothesis that patients select doctors whose substituted judgment they endorse is tenuous given that hospital-based physicians are often complete strangers. As such, our findings raise concern that the mismatch between patients’ preferences and the treatment that they receive is more than a simple matter of a failure of information exchange.(2)

The finding that willingness to use and to withdraw life-sustaining treatment varies systematically by physician characteristics is not a new finding. The most commonly documented source of variation in previous studies is the physician specialty. Vignette- or survey-based studies have found surgeons (19) and cardiologists (20, 21) less willing and oncologists (20) more willing to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments. Physician religion or religiosity is reported to be another factor influencing decision making. In one study, Catholic and Jewish physicians were less willing to withdraw life support.(22) In another study exclusively among Jewish physicians, those describing themselves as very religious were less willing to withdraw life-sustaining treatments.(23) Swanson found that physicians who reported attending religious services most frequently were more likely to require that the probability of treatment success must be zero before it is “futile.”(19)

The relationship between experience and willingness to withdraw life-sustaining treatment has similarly been reported, characterized in terms of time spent in practice, contact with critically ill patients in the ICU, and prior experience actually withholding or withdrawing treatment.(21, 22) Among the factors that may mediate the relationship between experience and willingness to withhold treatment is prognostic accuracy.(24)

There has been much less written about the ways that end-of-life communication skills and willingness to collaborate with other members of the care team vary by physician or specialty. Communication deficiencies are anecdotally endemic, and have been confirmed in studies of inpatient code status discussions (25) and outpatient oncology encounters (26).

Regarding the determinants of physician behavior, there has been little exploration beyond the intrinsic characteristic of religion and the extrinsic influence of specialty training and experience. Among the findings in our study deserving of further exploration are the ways in which variations in physicians’ perceptions of when a patient is “dying” and their own beliefs about quality of life influence end-of-life communication and decision making.

The conceptual framework we have presented for organization of the attributes of physician behavior is based on our interpretation. The categories of “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” may be oversimplifications. For example, there may be certain “intrinsic” characteristics that lead a medical student to choose a particular specialty in which to train, such as surgery or to be more or less responsive to financial incentives. A physician’s perception of when a person is “dying” may be strongly influenced by his or her specialty training and experience. That is, many of these attributes are not mutually exclusive, but may be interdependent in complex ways. Another complexity in this framework is the use of “experience” and “training” rather than “age”. The data suggest that experience leads to improved end-of-life communication skills, implying that older physicians would have more experience and would be better at communicating. The data also suggest that recent improvements in training in medical school and residency have led to improved communication, implying that younger physicians may be better in that regard. While seemingly at odds, each physician’s training and experience are varied, and we submit that collectively it is these attributes that independently predict communication skills rather than age.

Future work should be aimed at identifying the interrelatedness and specific impact of these attributes on physician variability in end-of-life treatment behaviors. This information would enable design of targeted interventions to reduce such variability. The two broader categories of physician attributions - beliefs and attitudes versus training, experience, and interaction with the healthcare system – would require different types of interventions. Interventions targeting attributes in training, experience, and interaction with the healthcare system may be directed at molding those attributes directly. An example might include an accreditation requirement for skills-based communication training for residents in all sub-specialties. On the other hand, physicians bring their beliefs and attitudes to the practice of medicine. Rather than molding or changing these attributes, interventions in this category would be targeted toward identifying and recognizing differences between physicians and their patients and encouraging physician behaviors consistent with patient preferences that do not compromise physicians’ beliefs or attitudes. An example might include Balint groups, which are regular case discussion in small groups under the guidance of a qualified group leader.

Our study has several limitations. Most importantly, it is based on hospital staff perceptions, not “objective” reality. Further, informants’ attributions of the causes of variations in physician behavior was informed by impressions with a range of validity, from assumption (eg, based upon observation and projection) to corroboration (eg, direct statements from physicians). For example, a respondent may assume that a physician behaves a certain way because of his or her religion, or a respondent may report hearing a doctor rationalize their behavior based upon their religion. Additionally, based upon our methodology, we have no way to analyze the relative impact of each domain on the main outcome, end-of-life treatment intensity. Another potential limitation is the exclusion from our analysis of a detailed accounting of evidence against the perception that treatment “depends on the doctor.” Although some informants made non-specific comments that might be interpreted as evidence against between-physician variation (eg, “Our doctors are good at having end-of-life discussions.”), none specifically said that treatment does not depend on the doctor. Inter-rater reliability on the non-specific text segments that were evidence against the “depends on the doctor” theme was too low to support formal coding and analysis. Another limitation is that we did not include patients or families in our study which may have constrained the perspective of our study. Finally, while our findings may generalize to the studied hospitals, they cannot be interpreted as broadly generalizable in the statistical sense. Nonetheless, we believe that by including a heterogeneous sample of hospitals and a broad range of informants at each hospital, triangulating data interpretation among a team of multidisciplinary researchers, and co-coding with high inter-rater reliability a sub-sample of transcripts, we have increased the reliability and validity of our findings.

Although our findings are alarming, they are not surprising. The literature on practice variations hypothesizes that greater uncertainty about the “right” treatment allows physician beliefs and prevailing social norms to dictate care. With the exception of brain death, there are no guidelines for the use of life-sustaining treatments for patients who may be near the end of life. Further, unlike other disease entities for which there are treatment guidelines (e.g., myocardial infarction, pneumonia, brain death), there is no evidence-base or consensus regarding when the condition – the “end of life” – commences.(27) Increasingly, experts in end-of-life care have called for the implementation of guidelines not for particular treatment of critically ill patients, but for processes of care that highlight patient-proxy-physician communication, pain and symptom management, and social and spiritual support.(28) Variation in physician communication skills is being addressed on a small scale with skills-based communication training interventions.(29) Future research should explore whether these initiatives reduce provider sources of variation in end-of-life treatment intensity.

Box. Quotations Illustrating Hospital Staff Perceptions of Behaviors that “Depend on the Doctor,” and their Attributions of Causes of Variation

BEHAVIORS

“It depends on the doctor.” (Nurses, Social Workers, Doctors)

End-of-life treatment intensity

“Some [doctors] are much more aggressive, [some] are less aggressive.”(Doctor)

“[With] a patient who is terminal from their chronic illness, [some physicians will] move them toward the direction of discontinuing treatments. Other physicians will not do that at all. They will encourage families to keep going, keep going.”(Nurse)

Communication with Patients/families

“Some [physicians] … are very, very, good [at discussing end-of-life issues] … but there are others – it is just completely against their nature.”(Social Worker)

“[Some of my colleagues] employ more aggressive tactics in terms of really pushing patients one way or another [with end-of-life treatment decisions.]”(Doctor)

Delivering prognosis:

“I think that [oncologists at this institution] present patients their options and I think they are very truthful with them. You know, that the treatments are not going to work … some oncologists [at other institutions] feel that … they can cure everybody”. (Nurse)

Goals of care discussions:

“So where I’m having the conversation with that patient that might be around, at the end of your days, do you want me to avoid, you know, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, you know, and heroics. They’re having the same conversation that says you want me to put this device in you. There’s a disconnect, you know. It’s a person who I’m trying to make sure they understand that there’s worse things than dying and we do that to people every day. And these guys would be telling them, you know, you’re going to die unless I put this in. And it’s a different conversation.”(Physician)

Code status discussions:

"I think there are those physicians who are good at defining the goals of treatment and then applying it to the code status form. [With other physicians,] it’s very much literally taking the form almost and saying do you want this checked, do you want this checked, do you want this checked.”(Nurse)

Collaboration with care team members

“There are some doctors who clearly don’t want to hear from the nurse and there are some physicians who will seek out the nurse at the bedside or whoever’s taking care of the patient.”(Doctor)

ATTRIBUTIONS

“Every physician has a different background. They went to school and were educated differently. They have different moral attitudes and ideas about life and death.”(Doctor)

Beliefs and attitudes

“We have at least one physician on our staff [whose] values kind of overtake the situation.”(Case Manager)

Religion and culture:

“Each [doctor’s] religious preference kind of plays a role [in their use of life-sustaining treatments]”. (Nurse)

“[Unlike other doctors, here, there are three from one ethnic background that] don’t want to give up. They don’t want to consent to palliative care. They think that they can keep going because maybe that’s the way their culture [or religion] was … that you just don’t give up, you just keep trying.”(Nurse)

Determination of when a patient is dying and implications for treatment:

“I don’t view giving someone antibiotics or giving someone Lasix as prolonging [death] … [I view it as] relieving suffering.”(Doctor)

“What you might interpret a level 2 [“all resources applied to preserve life, except those specifically checked, such as CPR”] or whatever, a lot different than I would. So, if we are both taking care of her, you might decide that she needs antibiotics where I might not. But I might think a PEG tube would be a good idea and you would say, ’Don’t do it.’”(Doctor)

Quality-of-life determination:

“I work with a couple of doctors who could care less about quality of life.”(Social Worker)

“[Some physicians] take on the elderly in some of these huge operations … And, there’s really no satisfaction to me as a physician to operate on someone and get them through a critical illness and find that they are bedridden for the rest of their life or totally unhappy because they’re unable to do the things that they do.”(Doctor)

[In discussing an octogenarian with multi-system organ failure]“Even though [continuing] may [have been] against her wishes… in my mind it seemed like it was worth it to try to resume [her] lifestyle [because] she was a jet setter and ran around the world much more so than her surrogates.”(Doctor)

Fear of failing:

"I think probably surgeons are more inclined to push extraordinary care than perhaps non-surgeons…I only say that surgeons perhaps have been more reluctant to ease up on end-of-life care primarily just from the personality of the surgeon that when a patient dies they consider it personal failure where as internists and the like accept it, you know, as part of life. Death is a part of life."(Doctor)

Socialization by and interaction with the health care system

Training:

“Surgeons are there to treat aggressively. That’s what they’re trained to do … [they] see hope where the rest of us begin to see futility.”(Chaplain)

“Surgeons very much are cultured and conditioned to think in terms of doing and being aggressive and going in the direction of cure. And when they can’t do anything specific that will make the patient better, they’re uncomfortable and probably in some ways don’t have the skill set to move in the direction of comfort. I think that it’s a feature of the training that surgeons get and the role models that they see.”(Doctor)

Role:

“[Tertiary care attendings treat intensively because] “their job is to advance science and technology.”(Nurse)

“[I take] the aggressive posture”, because “that’s what I do for a living – I operate on people”. (Doctor)

“From the perspective of a medical doctor in the emergency department, we have a job to do and it is to save peoples’ lives … we pretty much leave [discussion of non-aggressive treatment options] to family physicians or you know, the PCP.”(Doctor)

“The [surgeon] mentality really is … I’m trying to get them better, we’re not going to talk about end-of-life stuff”. (Nurse)

Experience:

“[Doctors] are much more comfortable with it when they have been doing it for some time … it definitely has to do with experience.”(Nurse)

“Older physicians have been there … so they are more likely to let go.”(Social Worker)

“Being a hospitalist and doing intensive inpatient care all the time …I personally feel that we probably do a better job at helping families get there than let’s say a general medicine faculty member … we have a lot of expertise and experience in taking care of these types of complicated inpatients … we have a better sense of when we’re starting to hit … the wall of futility.”(Doctor)

Response to Incentives:

“[With] private practitioners, I think there’s an incentive to keeping people in the hospital and doing more things to them is driven by finances of that. Here we are less driven by that. It’s a closed [salaried] staff.”(Doctor)

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this research was from National Institute on Aging grants K08 AG021921 and P01 AG19783. Amber Barnato would like to thank research mentors Derek Angus and Judith Lave for their intellectual and personal contributions.

Source of support: National Institute on Aging grants K08 AG021921 and P01 AG19783

References

- 1.Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Risks and Outcomes of Treatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46(10):1242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SUPPORT_Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpert HR, Emanuel L. Comparing utilization of life-sustaining treatments with patient and public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):175–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardin SB, Yusufaly YA. Difficult end-of-life treatment decisions: do other factors trump advance directives? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(14):1531–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnato AE, McClellan MB, Kagay CR, Garber AM. Trends in inpatient treatment intensity among Medicare beneficiaries at the end of life. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(2):363–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner J, Wennberg JE. National Bureau of Economic Research. How much is enough? Efficiency and Medicare spending in the last six months of life. 1998 Report No.: Working Paper 6513. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siu AL, Sonnenberg FA, Manning WG, et al. Inappropriate use of hospitals in a randomized trial of health insurance plans. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;315(20):1259–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611133152005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, et al. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garland A, Shaman Z, Baron J, Connors AF., Jr Physician-attributable differences in intensive care unit costs: a single-center study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(11):1206–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1810OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnato AE, Bost JE, Farrell MH, et al. Relationship between Staff Perceptions of Hospital Norms and Hospital-level End-of-life Treatment Intensity. Journal of Palliative Medicine. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0258. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser BG, Straus AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straus AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. Bmj. 2000;320(7227):114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;10(1):99–110. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson JW, McCrary SV. Doing all they can: physicians who deny medical futility. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 1994;22(4):318–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1994.tb01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett JM, Mutran E. Who decides? Physicians’ willingness to use life-sustaining treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(7):785–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.7.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly WF, Eliasson AH, Stocker DJ, Hnatiuk OW. Do specialists differ on do-not-resuscitate decisions? Chest. 2002;121(3):957–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christakis NA, Asch DA. Physician characteristics associated with decisions to withdraw life support. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(3):367–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenger NS, Carmel S. Physicians’ religiosity and end-of-life care attitudes and behaviors. Mt Sinai J Med. 2004;71(5):335–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):469–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [see comments] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM. Opening the black box: how do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(6):441–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 (Suppl 1):S95–102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamont EB. A demographic and prognostic approach to defining the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 (Suppl 1):S12–21. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, Pronovost PJ. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: a practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(4):264–71. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA. Teaching communication skills to medical oncology fellows. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2433–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]