Abstract

Evolutionary change in encephalization within and across mammalian clades is well-studied, yet relatively few comparative analyses attempt to quantify the impact of evolutionary change in relative brain size on cranial morphology. Because of the proximity of the braincase to the orbits, and the inter-relationships among ecology, sensory systems and neuroanatomy, a relationship has been hypothesized between orbit orientation and encephalization for mammals. Here, we tested this hypothesis in 68 fossil and living species of the mammalian order Carnivora, comparing orbit orientation angles (convergence and frontation) to skull length and encephalization. No significant correlations were observed between skull length and orbit orientation when all taxa were analysed. Significant correlations were observed between encephalization and orbit orientation; however, these were restricted to the families Felidae and Canidae. Encephalization is positively correlated with frontation in both families and negatively correlated with convergence in canids. These results indicate that no universal relationship exists between encephalization and orbit orientation for Carnivora. Braincase expansion impacts orbit orientation in specific carnivoran clades, the nature of which is idiosyncratic to the clade itself.

Keywords: Carnivora, convergence angle, encephalization, frontation angle, Mammalia

Introduction

The evolution of encephalization, or brain volume scaled to body mass, has long been of interest in mammalian evolutionary biology, due at least in part to the extreme increases in encephalization observed in mammals relative to several other amniote clades, particularly within the lineage leading to modern humans. There have been multiple, independent increases in encephalization through the evolutionary history of the mammalian order Carnivora (Finarelli & Flynn, 2007; Finarelli, 2008b). However, it is possible that evolutionary changes in the relative size of the braincase can impose corresponding structural changes on the morphology of other regions of the skull. Focusing on primates, Cartmill (1970) linked increased encephalization, particularly expansion of the frontal lobe, to increased verticality of the orbit, through forward displacement of the upper margin of the orbit.

Orbit orientation has been studied extensively within and among mammalian clades (Cox, 2008), and is of particular interest because of its hypothesized relationship to such ecological factors as locomotory style and hunting/foraging behaviour (e.g. Cartmill, 1972, 1974; Ross, 1995; Noble et al. 2000; Heesy, 2005). Orbit orientation is most commonly described using the convergence angle (CA) (the degree to which the orbits face laterally) and frontation angle (FA) (the degree of verticality of the orbits) (Cartmill, 1970, 1972 1974). Increased CA is related to greater stereoscopic vision and depth perception, and has been linked to arboreality and nocturnal visual predation in Primates (Cartmill, 1970, 1972). Noble et al. (2000) compared CA and FA for two carnivoran families, Felidae (cats) and Herpestidae (mongooses), as well as pteropodid bats, recovering significant positive correlations between FA and encephalization within the Felidae and between felids and herpestids (Noble et al. 2000). However, that analysis only examined two families within one of the two carnivoran suborders, Feliformia, and furthermore only considered extant species. Carnivorans exhibit a large morphological diversity outside those two families, especially within the suborder Caniformia (Wesley-Hunt, 2005). Moreover, including data from the fossil record has the potential to dramatically alter inferences of character evolution relative to analyses based solely on extant taxa (e.g. Finarelli & Flynn, 2006). Carnivora has both a well-resolved phylogeny (e.g. Flynn et al. 2005; Wesley-Hunt & Flynn, 2005) and an extensively sampled fossil record (e.g. Wesley-Hunt, 2005;Finarelli, 2008a), allowing us to study the interaction between change in orbit orientation and encephalization through carnivoran evolutionary history.

Materials and methods

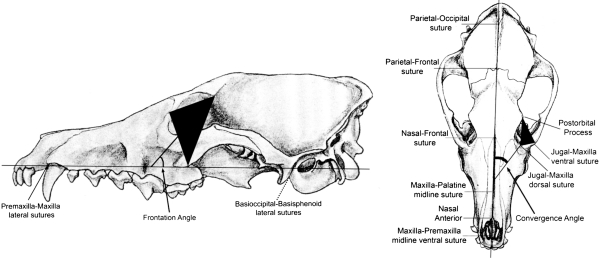

Landmark measurements and encephalization data

We measured the CA and FA of the orbital plane (Cartmill, 1970, 1972 1974) for 68 carnivoran taxa (37 extant and 31 fossil species), examining 442 specimens. To define the orbital plane we captured three-dimensional landmark data using a G2X three-dimensional digitizer (Immersion Microscribe, San Jose, CA, USA) (Goswami, 2006a,b). The orbital plane was defined using three landmarks: (1) the post-orbital process, (2) the dorsal suture of the jugal and maxilla, and (3) the ventral suture of the jugal and maxilla (Fig. 1). Although using the post-orbital process of the zygomatic would more closely correspond to the orbital plane, the zygomatic arch posterior to the jugal–maxilla suture is often incomplete or distorted in fossil specimens, which would severely restrict our ability to incorporate fossil taxa into our analysis. Because this plane does not directly correspond to the orbital plane, the angles measured in this study are not directly comparable to those in other data sets (e.g. Cartmill, 1970, 1972; Ross, 1995;Noble et al. 2000; Heesy, 2005). However, these data do distinguish more and less convergent or frontated orbits, and can be used to study the impact of changes in relative volume of the braincase on the orientation of the orbits. We also defined two reference planes in the skull: the mid-sagittal plane (defined using three to six landmarks, as some fossil specimens were missing some of the six mid-sagittal plane landmarks) and the basal plane (defined using four landmarks; Fig. 1) (Goswami, 2006a,b). Using routines written in Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Inc., Champaign, IL, USA), we calculated the measures of the dihedral angles between the orbital and reference planes; the angle between the orbital plane and the mid-sagittal plane of the skull measured the CA and the angle between the orbital plane and the basal plane of the skull measured the FA. A larger CA indicates more anteriorly-oriented orbits, when viewed from above, whereas a larger FA indicates more vertically-oriented orbits, when viewed from the side.

Fig. 1.

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) skull showing the landmarks used to define the orbital plane and the two reference planes (basal plane, left and mid-sagittal plane, right). The convergence and frontation angles were measured as the dihedral angles between the orbital reference planes.

We evaluated the relationship of orbit orientation angles to both skull length and encephalization. Skull length was used as a proxy for body size (Van Valkenburgh, 1990) and we estimated this using the chord length between the occipital condyle lateral margin and the premaxilla–maxilla anterior lateral suture (Goswami, 2006a,b), averaging over measurements of both the left and right sides. To calculate encephalization, we used an extensive database of adult body masses and endocranial volume estimates for living and fossil carnivorans (Finarelli, 2008a,b; Finarelli & Flynn, 2006, 2007), measuring the logarithm of the encephalization quotient (logEQ) (e.g. Marino et al. 2004; Finarelli & Flynn, 2007), calculating the encephalization quotient relative to the brain volume/body mass allometry for extant Carnivora. We used the base-2 logarithm, such that log2EQ = 1 indicates a brain double the expected volume for a given body mass, whereas log2EQ = –1 indicates a volume half as large as expected. Body masses, brain volumes, skull lengths and orbit orientation angles are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data for carnivoran taxa

| Suborder | Family | Subfamily | Genus | Species | log2EQ | CA | FA | Skull length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caniformia | Amphicyonidae | Daphoenodon | superbus | –0.755 | 36.737 | 59.025 | 200.892 | |

| Caniformia | Amphicyonidae | Daphoenus | hartshornianus | –0.051 | 27.039 | 66.21 | 138.620 | |

| Caniformia | Amphicyonidae | Daphoenus | vetus | –0.171 | 21.349 | 70.168 | 179.704 | |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Aelurodon | ferox | 0.117 | 28.874 | 74.554 | 176.419 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Aelurodon | mcgrewi | –0.757 | 26.946 | 74.692 | 179.021 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Aelurodon | taxoides | 0.089 | 32.753 | 72.216 | 220.284 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Borophagus | littoralis | 0.140 | 22.93 | 83.303 | 172.120 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Borophagus | secundus | –0.030 | 22.271 | 73.851 | 157.511 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Carpocyon | webbi | 0.049 | 18.324 | 83.604 | 190.146 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Epicyon | saevus | –0.341 | 21.257 | 74.063 | 187.444 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Microtomarctus | conferta | –0.244 | 20.863 | 71.756 | 106.906 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Tomarctus | brevirostris | –0.693 | 30.806 | 68.551 | 153.065 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Borophaginae | Tomarctus | hippophaga | 0.026 | 26.462 | 68.531 | 145.706 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Caninae | Canis | lupus | 0.187 | 18.122 | 75.619 | 198.859 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Caninae | Canis | dirus | –0.022 | 19.552 | 79.335 | 223.315 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Caninae | Cerdocyon | thous | 0.249 | 18.49 | 80.232 | 110.083 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Caninae | Otocyon | megalotis | –0.169 | 19.029 | 81.256 | 98.888 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Caninae | Vulpes | vulpes | 0.239 | 21.527 | 71.41 | 105.873 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Enhydrocyon | pahinsintewakpa | –0.583 | 36.505 | 59.309 | 146.455 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Enhydrocyon | stenocephalus | –0.327 | 32.614 | 65.535 | 148.812 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Hesperocyon | gregarius | –0.460 | 27.78 | 64.125 | 80.396 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Mesocyon | brachyops | –0.150 | 22.674 | No data | 119.707 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Mesocyon | coryphaeus | –0.196 | 24.916 | 70.134 | 135.245 |

| Caniformia | Canidae | Hesperocyoninae | Osbornodon | fricki | –0.357 | 18.515 | 84.84 | 208.343 |

| Caniformia | Ailuridae | Ailurus | fulgens | 0.280 | 28.497 | 68.448 | 91.303 | |

| Caniformia | Mephitidae | Mephitis | mephitis | –0.903 | 22.895 | 71.825 | 65.095 | |

| Caniformia | Mephitidae | Spilogale | putorius | –0.229 | 23.617 | 72.205 | 46.684 | |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Basal group | Leptarctus | primus | –0.803 | 26.624 | 80.809 | 78.975 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Basal group | Meles | meles | –0.341 | 28.131 | 65.415 | 102.450 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Basal group | Taxidea | taxus | 0.188 | 33.727 | 61.457 | 111.521 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Basal group | Melogale | personata | –0.283 | 22.056 | 73.446 | 66.340 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Lutrinae | Enhydra | lutris | 0.412 | 33.824 | 60.593 | 117.395 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Martes group | Gulo | gulo | 0.040 | 31.291 | 66.054 | 127.112 |

| Caniformia | Mustelidae | Martes group | Martes | pennanti | 0.111 | 26.94 | 67.183 | 97.503 |

| Caniformia | Procyonidae | Potosinae | Potos | flavus | 0.066 | 32.079 | 80.52 | 69.395 |

| Caniformia | Procyonidae | Procyoninae | Procyon | lotor | 0.137 | 25.075 | 69.938 | 95.517 |

| Caniformia | Procyonidae | Procyoninae | Procyon | cancrivorus | 0.490 | 26.11 | 68.892 | 109.064 |

| Caniformia | Procyonidae | Procyoninae | Nasua | narica | 0.055 | 22.243 | 73.128 | 101.707 |

| Caniformia | Ursidae | Ailuropodinae | Ailuropoda | melanoleuca | –0.125 | 33.529 | 58.287 | 220.604 |

| Caniformia | Ursidae | Ursinae | Arctodus | simus | 0.595 | 18.885 | 83.276 | 349.314 |

| Caniformia | Ursidae | Ursinae | Tremarctos | ornatus | –0.407 | 23.351 | 75.728 | 185.386 |

| Caniformia | Ursidae | Ursinae | Melursus | ursinus | 0.393 | 18.165 | 73.616 | 234.368 |

| Caniformia | Ursidae | Ursinae | Ursus | americanus | 0.096 | 25.583 | 78.855 | 236.004 |

| Feliformia | Eupleridae | Euplerinae | Cryptoprocta | ferox | –0.693 | 25.402 | 70.656 | 109.353 |

| Feliformia | Eupleridae | Euplerinae | Eupleres | goudotii | –0.525 | 22.485 | 70.062 | 74.604 |

| Feliformia | Eupleridae | Euplerinae | Fossa | fossana | 0.347 | 25.353 | 67.376 | 74.732 |

| Feliformia | Eupleridae | Galidiinae | Galidia | elegans | 0.062 | 21.687 | 71.633 | 58.678 |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Acinonyx | jubatus | –0.475 | 32.761 | 67.122 | 137.928 | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Felis | silvestris | 0.036 | 33.161 | 79.028 | No data | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Homotherium | hadarensis | –0.261 | 22.177 | 74.019 | 279.630 | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Lynx | rufus | 0.220 | 31.883 | 71.700 | 103.509 | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Panthera | atrox | 0.415 | 12.408 | 78.698 | 302.918 | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Prionailurus | bengalensis | 0.178 | 30.403 | 76.709 | 80.014 | |

| Feliformia | Felidae | Smilodon | fatalis | –0.262 | 21.423 | 76.558 | 248.126 | |

| Feliformia | Herpestidae | Cynictis | penicillata | –0.009 | 27.696 | 85.708 | 50.700 | |

| Feliformia | Herpestidae | Ichneumia | albicauda | –0.152 | 24.747 | 72.716 | 92.962 | |

| Feliformia | Hyaenidae | Crocuta | crocuta | –0.319 | 28.975 | 74.439 | 209.125 | |

| Feliformia | Hyaenidae | Proteles | cristata | –0.612 | 35.35 | 70.705 | 122.051 | |

| Feliformia | Nandiniidae | Nandinia | biontata | –0.113 | 25.728 | 70.634 | 88.973 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Barbourofelis | morrisi | –0.667 | 30.601 | 86.551 | 174.303 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Dinictis | cyclops | 0.004 | 31.453 | 72.78 | 125.563 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Dinictis | feline | –0.312 | 32.687 | 66.869 | 141.283 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Hoplophoneus | primaevus | 0.133 | 25.202 | 71.12 | 135.388 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Nimravus | brachyops | –0.387 | 32.386 | 68.402 | 160.492 | |

| Feliformia | Nimravidae | Pogonodon | platycopis | –0.390 | 22.914 | 75.049 | 186.115 | |

| Feliformia | Viverridae | Civettictis | civetta | –0.712 | 29.011 | 64.663 | 126.256 | |

| Feliformia | Viverridae | Genetta | genetta | –0.417 | 33.652 | 63.854 | 75.967 | |

| Feliformia | Viverridae | Paradoxurus | hemaphroditus | –0.447 | 41.574 | 59.446 | 84.479 |

Species are arranged by taxonomic groups. Log2EQ, convergence angle (CA), frontation angle (FA) and skull length are given for each species, angles in degrees and skull length in mm. Log2EQ is the base-2 logarithm of the encephalization quotient (Jerison, 1970, 1973; Radinsky, 1977). Missing values are shown as ‘no data.’ See text for further discussion.

Phylogeny of the carnivora and independent contrasts

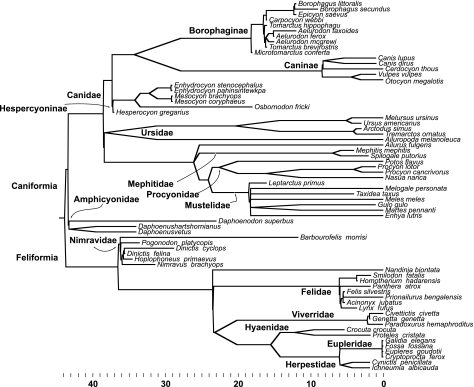

Valid statistical analysis of comparative data in biological systems requires information on the phylogenetic relationships of the organisms being analysed to account for the statistical non-independence of character values observed for closely related taxa (Felsenstein, 1985; Garland et al. 1992, 1999; Garland & Ives, 2000). To account for this, we constructed a composite cladogram of the Carnivora, assembling evolutionary relationships among taxa from numerous molecular morphological and total evidence phylogenetic analyses that have recently been performed for this clade (see review in Flynn et al. in press). The cladogram depicting the relationships among the major Carnivoran clades is given in Fig. 2. Taxa included in this analysis span all of the extant families of terrestrial carnivorans, in addition to the extinct families Amphicyonidae and Nimravidae. The clade of marine carnivorans, Pinnipedia, was not included, however, as brain volume/body mass scaling for this group is still poorly understood and no model for estimation of brain volumes for fossil taxa exists.

Fig. 2.

Phylogeny of the Carnivora used in the analysis of independent contrasts of orbit orientation angles and encephalization. Branch lengths are calibrated using first appearance data from the fossil record and the units along the horizontal axis represent millions of years before present. The phylogenetic analyses supporting the nodes in the cladogram are summarized in a review by Flynn et al. (in press).

Using this composite cladogram, we calculated correlations for phylogenetically independent contrasts (Felsenstein, 1985) of CA and FA with both skull length and encephalization, with the PDAP (Midford et al. 2003) module for Mesquite (Maddison & Maddison, 2007). Independent contrasts are scaled relative to the distance (branch length) between the observation and the node estimate (Felsenstein, 1985; Garland et al. 1999; Garland & Ives, 2000). Incorporating branch length information can have a significant impact on reconstruction (Oakley & Cunningham, 2000; Webster & Purvis, 2002; Finarelli & Flynn, 2006) and we therefore calibrated branch lengths using first appearances in the fossil record (Finarelli & Flynn, 2007; Finarelli, 2008b).

Results

Fossil taxa have a large impact on the strength of correlations between orientation angles and both skull length and encephalization. CA is significantly and positively correlated with skull length in extant Carnivora although, when comparing Feliformia and Caniformia separately, this significant correlation appears confined to feliforms. However, when all available taxa are included in the analysis, no significant correlations are recovered for CA (Table 2). It should be noted that Felidae shows a strong negative correlation between CA and skull length, whereas its sister clade Viverridae + ‘Herpestidae’ + Hyaenidae shows an equally strong positive correlation. Although neither of these correlations differs significantly from zero, they are significantly different from one another (P < 0.001). Thus, Felidae shows a significantly different response in CA with respect to increasing encephalization than do other feliforms. No significant correlations are observed between FA and skull length, irrespective of whether or not fossils are included (Table 2). From this we conclude that no single relationship between skull size and orbit orientation characterizes Carnivora.

Table 2.

Correlations for independent contrasts of orientation angles and skull length

| Convergence angle |

Frontation angle |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clade | n | r | P | r | P |

| Extant taxa only | |||||

| Carnivora | 38 | 0.506 | 0.001 | –0.189 | 0.263 |

| Caniformia | 22 | 0.138 | 0.541 | –0.236 | 0.290 |

| Arctoidea | 17 | 0.261 | 0.311 | –0.403 | 0.110 |

| Feliformia | 16 | 0.546 | 0.035 | –0.188 | 0.501 |

| All taxa | |||||

| Carnivora | 68 | 0.057 | 0.649 | 0.108 | 0.389 |

| Caniformia | 43 | –0.122 | 0.437 | 0.296 | 0.057 |

| Crown-clade Caniformia * | 40 | –0.126 | 0.439 | 0.306 | 0.058 |

| Canidae | 21 | 0.132 | 0.569 | 0.380 | 0.099 |

| Arctoidea | 19 | –0.116 | 0.636 | –0.039 | 0.900 |

| Feliformia | 25 | 0.151 | 0.480 | 0.013 | 0.951 |

| Felidae | 7 | –0.783 | 0.065 | 0.031 | 0.544 |

| Viverridae, Hyaenidae, ‘Herpestidae’† | 11 | 0.541 | 0.085 | –0.131 | 0.701 |

| ‘Herpestidae’† | 6 | 0.728 | 0.101 | –0.152 | 0.773 |

Crown-clade Caniformia excludes the Amphicyonidae and is identical to ‘Caniformia’ in the extant-only analysis.

‘Herpestidae’ includes true mongooses and Malagasy carnivorans, as previous analyses include some or all of these taxa in Herpestidae.

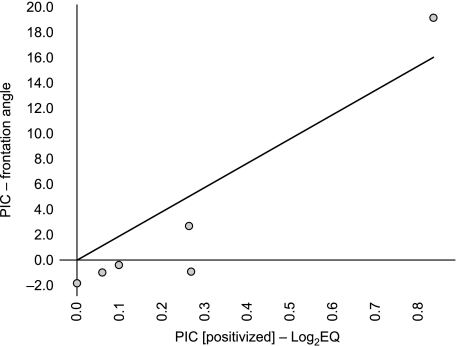

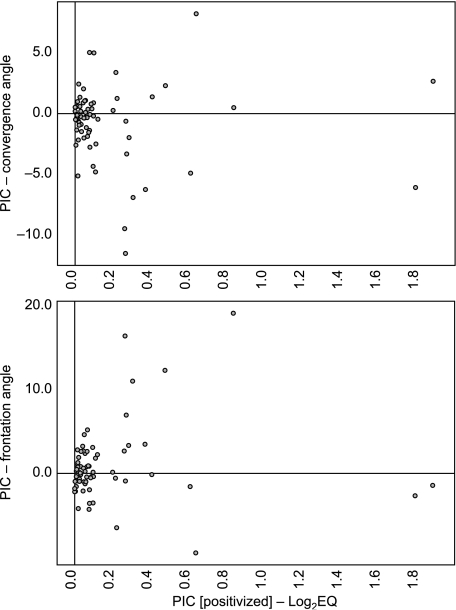

In contrast to skull length, no significant correlations exist between encephalization and orbit orientation among extant taxa. When fossil and extant taxa are included in the analysis, no relationships exist between encephalization and either orientation angle, arguing against Carnivora-wide structural relationships between orbit orientation and encephalization (Fig. 3). However, we do observe several significant correlations for analyses among carnivoran subclades when fossil and living taxa are analysed. FA is positively correlated with encephalization for Felidae (Noble et al. 2000) (Table 3), although in our data set this is due to the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), which stands out as an outlier (Fig. 4). Excluding the cheetah removes the significance (r = 0.320, P = 0.588); therefore this correlation must be viewed with caution until a larger sample is examined.

n, number of taxa; r, Pearson correlation coefficient; P, two-tailed significance. Significant correlations are highlighted in bold. Extant-only analyses are made for a smaller number of taxonomic groups, as sample size precluded finer partitioning.

Fig. 4.

Biplot of independent contrasts [log2EQ, x-axis; (FA), y-axis] for Felidae. Note that an outlier (Acinonyx jubatus, the cheetah) is responsible for drawing the correlation into significance. Although it is possible that a significant relationship between FA and encephalization among cats does indeed exist, this result must be considered speculative as yet. PIC, phylogenetically independent contrast.

Fig. 3.

Biplots of phylogenetically independent contrasts (PICs) for all taxa in the Carnivora. The PIC values for log2EQ have been ‘positivized’ along the x-axis (see Garland et al. 1992, 1997; Garland & Ives, 2000). PICs for orientation angles (convergence angle, top; frontation angle, bottom) are given on the y-axes. There is no systematic pattern across the Carnivora between either of the two orientation angles and relative brain volume. Rather, all significant correlations that we observe are restricted to the families Canidae and Felidae.

Within Caniformia encephalization is correlated positively with FA and negatively with CA (Table 3); larger relative brain size is associated with more vertically-and laterally-oriented orbits. The significance in these correlations is driven solely by Canidae; both angles are significantly correlated for Canidae but its sister clade Arctoidea displays no significant correlations (Table 3). However, modern canids (subfamily Caninae) have a significantly higher degree of encephalization than the two extinct subfamilies Borophaginae and Hesperocyoninae (Finarelli, 2008a). It is possible that the increase in encephalization characterizing Caninae coincides with changes in CA and FA, rather than there being a true correlation linking encephalization with orbit orientation (Fig. 5). Calculating the values of log2EQ against two regressions fit specifically to the modern subfamily and the extinct canid subfamilies eliminates the offset in encephalization between living and extinct canids. When this is done, both correlations remain significant (FA: r = 0.595, P = 0.006; CA: r = –0.482, P = 0.027) and thus the significant correlations are not artefacts of the encephalization increase in modern Caninae.

Table 3.

Correlations for independent contrasts of orientation angles and encephalization

| Convergence angle |

Frontation angle |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clade | n | r | P | r | P |

| Extant taxa only | |||||

| Carnivora | 38 | 0.004 | 0.982 | 0.030 | 0.857 |

| Caniformia | 22 | 0.088 | 0.698 | –0.318 | 0.151 |

| Arctoidea | 17 | 0.720 | 0.783 | –0.221 | 0.395 |

| Feliformia | 16 | 0.001 | 0.998 | 0.041 | 0.880 |

| All taxa | |||||

| Carnivora | 68 | –0.163 | 0.183 | 0.166 | 0.179 |

| Caniformia | 43 | –0.442 | 0.002 | 0.466 | 0.002 |

| Crown-clade Caniformia | 40 | –0.438 | 0.005 | 0.464 | 0.003 |

| Canidae | 21 | –0.484 | 0.026 | 0.542 | 0.010 |

| Arctoidea | 19 | –0.124 | 0.613 | –0.191 | 0.434 |

| Feliformia | 25 | –0.076 | 0.719 | 0.062 | 0.769 |

| Felidae | 7 | –0.184 | 0.694 | 0.911 | 0.004 |

| Viverridae, Hyaenidae, ‘Herpestidae’ | 11 | –0.005 | 0.989 | –0.403 | 0.219 |

| ‘Herpestidae’ | 6 | –0.020 | 0.970 | –0.428 | 0.397 |

Abbreviations as in Table 2

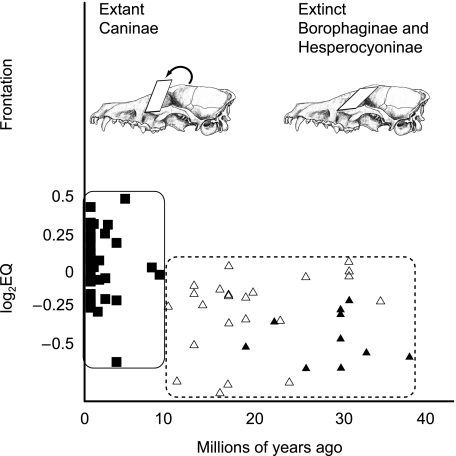

Fig. 5.

A shift in canid encephalization could be responsible for a perceived relationship between relative brain volume and orientation angles. At the bottom, encephalization data for the Canidae from Finarelli (2008b) are plotted against first appearances in the fossil record. The extinct Borophaginae (open triangles) and Hesperocyoninae (closed triangles) exhibit a lower degree of encephalization than modern Caninae (squares). It is possible that the correlations are an artefact of this shift coinciding with a shift in orientation angle (e.g. frontation). This is not the case, as the correlations remain significant even after this offset in encephalization is removed with clade-specific regressions.

Discussion

The impact of taxonomic breadth and inclusion of fossils in the sample on perceived correlations is remarkable. With all taxa included, significant correlations are observed but are confined to two families, i.e. Felidae and Canidae. Felids show a positive correlation between FA and encephalization (Table 3), although we note that this may be a sampling artefact. Both angles are significantly correlated in the Canidae, positive for FA and negative for CA (Table 3). It should be noted that, in both cases where we observe a significant correlation between FA and encephalization, the correlation is positive and the corresponding correlation for both families’ sister clades is negative. Thus, it is not simply the strength of the relationship in these two clades that differs from closely related carnivorans but also the direction of the relationship.

Noble et al. (2000) also recovered a significant, positive correlation between FA and encephalization in Felidae. Following Cartmill (1970, 1972), they hypothesized a structural constraint on FA in response to an expanding braincase such that, for taxa with more convergent orbits, increased encephalization necessitates a forward rotation of the upper orbit margin. They argued that failure to recover a significant correlation among their sample of Herpestidae could have resulted from uniformly lower CA, lower encephalization or both. However, even if we accept that the significant correlation between FA and encephalization observed in our data set for Felidae is not an artefact, Felidae is not significantly more convergent than either all other feliform taxa (Mann-Whitney test, two-tailed, P = 0.653) or their sister clade (P = 0.653).

Moreover, among canids, encephalization is positively correlated with FA but negatively correlated with CA, i.e. we observe more vertically-and more laterally-oriented orbits in canids as encephalization increases. The model of Noble et al. (2000) for the positive relationship with FA in Felidae would predict the opposite of what we observe in Canidae, i.e. increasingly less convergent orbits as encephalization increases should not be simultaneously more frontated. As discussed above, Noble et al. (2000) explained the lack of this pattern in Herpestidae as potentially reflecting lower CA, and one could make a similar argument that canids have not surpassed some threshold convergence value that is needed to impart structural constraints. However, canids are not significantly less convergent than felids (Mann-Whitney test, two-tailed, P = 0.337) and, even if canids were, one would still need a separate model to explain the correlation with frontation in this clade. These results cast doubt on a single structural relationship between encephalization and orbit orientation across Carnivora and, by extension, across Mammalia. Rather, the correlations that we observe appear idiosyncratic to individual carnivoran clades and structural relationships are probably equally distinct.

The carnivoran skull is composed of multiple phenotypic modules, characterized by relatively high within-module and low among-module correlations (Goswami, 2006a,b). This modularity is hypothesized to allow independent evolution among different cranial regions, while preserving necessary functional relationships within modules. Goswami (2006a) demonstrated that the braincase and orbit represent two independent modules that are conserved across therian mammals. The lack of a systematic relationship between encephalization and orbit orientation in carnivorans, observed here, is consistent with this model of module independence. It is noteworthy that the only clades that displayed significant correlations between phylogeny and degree of integration were Felidae and Canidae (Goswami, 2006b), the same two families that deviate from other carnivorans (and more importantly their immediate sister taxa) in this study. Most studies of carnivoran skull morphology, ontogeny and allometry have focused on Felidae and Canidae, and patterns within these two families are often generalized to their respective suborders, Feliformia and Caniformia (Sears et al. 2007). However, this study joins a growing body of work demonstrating that skull development, morphology and integration for Canidae and Felidae are probably atypical, rather than representing carnivoran exemplars.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Flynn and V. Weisbecker for ideas, suggestions and comments on drafts. This project was funded, in part, by AMNH Collections Study Grants (to J.A.F. and A.G.), National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grants (DEB-0608208 to J.A.F., DEB-0308765 to A.G.), NSF International Research Fellowship (OISE-0502186 to A.G.) and the University of California Samuel P. and Doris Welles Fund (to A.G.). We thank W. Simpson and W. Stanley (FMNH), D. Diveley, J. Spence and C. Norris (AMNH), C. Shaw (Page Museum), P. Holroyd (UCMP), X. Wang and S. McLeod (LACM), C. Joyce and D. Brinkman (YPM), A. Tabrum and C. Beard (CMNH), L. Gordon and R. Purdy (SI-NMNH), J. Hooker, A. Currant and P. Jenkins (NHM), P. Tassy and C. Sagne (MHNM), and K. Krohmann (Senckenberg) for access to specimens.

References

- Cartmill M. The Orbits of Arboreal Mammals: a Reassessment of the Arboreal Theory of Primate Evolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle R. Cartmill M. The Functional and Evolutionary Biology of Primates. Chicago: Aldine; 1972. Arboreal adaptations and the origin of the Order Primates; pp. 97–122. (ed), pp. [Google Scholar]

- Cartmill M. Rethinking primate origins. Science. 1974;184:436–443. doi: 10.1126/science.184.4135.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox PG. A quantitative analysis of the Eutherian orbit: correlations with masticatory apparatus. Biol Rev. 2008;83:35–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am Nat. 1985;125:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Finarelli JA. Hierarchy and the reconstruction of evolutionary trends: evidence for constraints on the evolution of body size in terrestrial caniform carnivorans (Mammalia) Paleobiology. 2008a;34:553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Finarelli JA. Testing hypotheses of the evolution of brain-body size scaling in the Canidae (Carnivora, Mammalia) Paleobiology. 2008b;34:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Finarelli JA, Flynn JJ. Ancestral state reconstruction of body size in the Caniformia (Carnivora, Mammalia): the effects of incorporating data from the fossil record. Syst Biol. 2006;55:301–313. doi: 10.1080/10635150500541698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finarelli JA, Flynn JJ. The evolution of encephalization in caniform carnivorans. Evolution. 2007;61:1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JJ, Finarelli JA, Spaulding M. Phylogeny of the Carnivora and Carnivoramorpha, and the use of the fossil record to enhance understanding of evolutionary transformations. In: Goswami A, Friscia AR, editors. Carnivora: Phylogeny, Form and Function. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; (eds)in press. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JJ, Finarelli JA, Zehr S, Hsu J, Nedbal MA. Molecular phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships. Syst Biol. 2005;54:317–337. doi: 10.1080/10635150590923326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Harvey PH, Ives AR. Procedures for the analysis of comparative data using phyogenetically independent contrasts. Syst Biol. 1992;41:18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Ives AR. Using the past to predict the present: confidence intervals for regression equations in phylogenetic comparative methods. Am Nat. 2000;155:346–364. doi: 10.1086/303327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Martin KLM, Diaz-Uriarte R. Reconstructing ancestral trait values using squared-change parsimony: plasma osmolarity at the origin of amniotes. In: Sumida SS, Martin KLM, editors. Amniote Origins: Completing the Transition to Land. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 425–501. (eds), pp. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Midford PE, Ives AR. An introduction to phylogenetically based statistical methods, with a new method for confidence intervals on ancestral values. Am Zool. 1999;39:374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami A. Cranial modularity shifts during mammalian evolution. Am Nat. 2006a;168:270–280. doi: 10.1086/505758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami A. Morphological integration in the carnivoran skull. Evolution. 2006b;60:169–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesy CP. Function of the mammalian postorbital bar. J Morphol. 2005;264:363–380. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerison H. Brain evolution: new light on old principles. Science. 1970;170:1224–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3963.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerison H. Evolution of the Brain and Intelligence. New York: Academic Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis [Google Scholar]

- Marino L, McShea DW, Uhen MD. Origin and evolution of large brains in toothed whales. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;281A:1247–1255. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midford P, Garland T, Maddison WP. PDAP package (of Mesquite) [Google Scholar]

- Noble VE, Kowalski EM, Ravosa MJ. Orbit orientation and the function of the mammalian postorbital bar. J Zool. 2000;250:405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley TH, Cunningham CW. Independent contrasts succeed where ancestor reconstruction fails in a known bacteriophage phylogeny. Evolution. 2000;54:397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radinsky L. Brains of early carnivores. Paleobiology. 1977;3:333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CF. Allometric and functional influences on primate orbit orientation and the origins of the Anthropoidea. J Hum Evol. 1995;29:201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sears KE, Goswami A, Flynn JJ, Niswander L. The correlated evolution of Runx2 tandem repeats and facial length in Carnivora. Evol Devel. 2007;9:555–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damuth J, MacFadden BJ, editors. Body Size in Mammalian Paleobiology: Estimation and Biological Implications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. Skeletal and dental predictors of body mass in carnivores; pp. 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Webster AJ, Purvis A. Testing the accuracy of methods for reconstructing ancestral states of continuous characters. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;269:143–149. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley-Hunt GD. The morphological diversification of carnivores in North America. Paleobiology. 2005;31:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wesley-Hunt GD, Flynn JJ. Phylogeny of the Carnivora: basal relationships among the carnivoramorphans, and assessment of the position of ‘Miacoidea’ relative to crown-clade Carnivora. J Syst Palaeontol. 2005;3:1–28. [Google Scholar]