Abstract

Patients with COPD most frequently complain of breathlessness and cough and these are both increased during exacerbations. Studies have generally focused on quality of life during end-stage disease, where breathlessness becomes dominant and cough less important. There are very little data on the frequency and severity of cough in COPD or its impact on quality of life at different stages of disease. Little is known about the factors that influence objective cough counts in COPD. Cough may be a marker for progressive disease in milder COPD patients who continue to smoke, and it may be useful in case-finding for milder disease in the community. The cough reflex sensitivity is heightened in COPD compared with healthy volunteers and similar to that in subjects with asthma. The degree of airflow obstruction does not predict cough reflex sensitivity or objective cough counts, implying an independent process. Effective treatments for cough in COPD have not yet been identified. Improved outcome measures of cough, a better understanding of cough in the natural history of COPD, and its importance to patients are needed.

Keywords: cough, COPD, cough challenge

Introduction

Cough is an unfashionable topic, except for a few groups who are focused mainly on patients with chronic idiopathic cough. It is hard to understand why other causes of cough have not been studied in any detail. From the patients’ viewpoint, cough is the commonest reason for presentation to a primary care physician (Burt and Schappert 2004), and can be associated with significant morbidity, including rib fractures and stress incontinence. The relationship in many diseases, between cough frequency and severity, and quality of life is unexplored.

Cough has been largely ignored by the pharmaceutical industry, with no new effective anti-tussive in 100 years. This may be because symptom control does not fit into a disease-orientated model, but also because the biological mechanisms underlying cough are not well understood and may involve complex lung–brain interactions. Much basic work has involved the guinea pig (Canning et al 2004), but to what extent this reflects human cough is unclear. Many potential anti-tussives have been screened using cough reflex sensitivity in humans (Morice 1996; Morice et al 2001). However, the relationship between cough reflex sensitivity and objective cough counts is uncertain and it is possible that effective anti-tussives have been discarded for lack of appropriate clinical outcome measures in randomized studies.

COPD is characterized by airway inflammation and progressive airflow obstruction, most commonly caused by cigarette smoking. Cough, breathlessness, and sputum production are the major symptoms of which patients complain (Rennard et al 2002), although the relative importance depends on the stage of disease. The diagnostic criteria in the first classifications of smoking-related lung disease (MRC 1965) were based on the clinical patterns of symptoms and cough featured strongly. The definition of chronic bronchitis as “cough and sputum production for at least 3 months of the year on two consecutive years”, was probably describing early or mild disease. A cross-sectional study has shown that patients with mild to moderate airflow obstruction report cough and sputum production more frequently than those with severe disease (von Hertzen et al 2000). However, as evidence accumulated that the degree of airflow obstruction was a predictor of mortality (Fletcher and Peto 1977), the emphasis in patients with later stage disease then switched to breathlessness, and cough diminished in importance.

The recent Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (Pauwels et al 2001) classifies patients with symptoms such as cough, but without airflow obstruction as Stage 0 disease, suggesting that these patients are at risk of developing COPD. Evidence that cough is an important predictor of future progression in Stage 0 patients is lacking (Vestbo and Lange 2002), but a productive cough in the presence of already established airflow obstruction, does predict FEV1 decline (Vestbo et al 1996) (Table 1). Consequently, cough may be a useful factor in case finding of patients at risk of progressive airflow obstruction in the community. In a primary care study, age and cough were the best predictors of airflow obstruction on spirometry (Van Schayck et al 2002) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Cough and smoking habit as predictors of lung function decline in patients with established airflow obstruction. Increasing smoking predicts a more rapid FEV1, especially in women. Mucus hyper-secretion in men also predicts decline. Reprinted from Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. 1996. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 153:1530–5. Copyright © 1996 with permission from American Thoracic Society.

| Men

|

Women

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 decline | p | FEV1 decline | p | |

| Heavy Smokers | 14.1 | 0.01 | 25.0 | 0.00001 |

| Medium Smokers | 12.4 | 0.003 | 7.8 | 0.009 |

| Light Smokers | 3.3 | 0.47 | 7.2 | 0.006 |

| Chronic Mucus Hypersecretion | 23.0 | 0.002 | 11.3 | 0.06 |

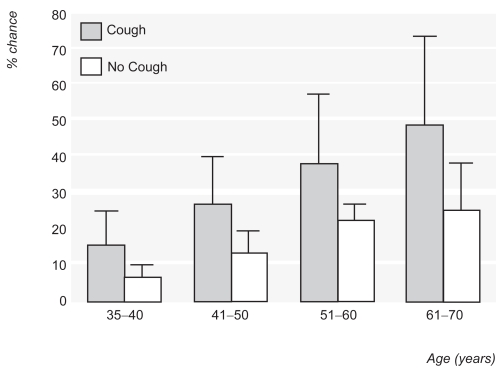

Figure 1.

Chance of having airflow obstruction with increasing age in smokers with or without cough (bars are 95% confidence intervals). Reprinted from Van Schayck CP, Loozen JM, Wagena E, et al. 2002. Detecting patients at a high risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice: cross sectional case finding study. BMJ, 324:1370–5. Copyright © 2002 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group.

Why do patients with COPD cough?

There are a number of reasons why patients with COPD cough. First there is substantial airway inflammation. Using techniques including bronchoalveolar lavage (Rutgers et al 2000), analysis of spontaneous and induced sputum (Lapperre et al 2004; Brightling et al 2005), and exhaled breath condensates (Biernacki et al 2003; Montuschi et al 2003) it has been possible to identify numerous inflammatory mediators and cellular components of airway inflammation in COPD (Bhowmik et al 2000; Rutgers et al 2000; Gompertz et al 2001; Biernacki et al 2003; Montuschi et al 2003). Some inflammatory mediators are known to be tussive agents such as prostaglandins (Choudry et al 1989), or indirectly implicated in cough reflex activation and mucus secretion, eg, tachykinins (Joos et al 2003). Whether these substances may be involved in stimulating cough or heightening cough reflex sensitivity in COPD, and could be amenable to treatment, is unknown.

Doherty et al (2000) investigated the cough reflex sensitivity to capsaicin in COPD and asthma compared with healthy volunteers. In this group of COPD hospital out-patients, with a mean FEV1 of 42% predicted, 81% of patients complained of cough on most days, despite there being no selection for the symptom of cough. The median cough threshold was significantly reduced (ie, reflex sensitivity increased) compared with healthy controls and similar to subjects with asthma (Figure 2). Other smaller studies have failed to replicate this finding (Fujimura et al 1998; Dicpinigaitis 2001); this may be due to study size, differences in challenge methodology, or to differences in the severity of the disease in the patients included. The capsaicin sensitivity was moderately related to cough diary scores over a 2-week period (r= −0.44, p=<0.05) but completely unrelated to airflow obstruction (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative frequency at which subjects reached cough threshold (C5) for subjects with COPD and asthma compared with normal subjects. Reprinted from Doherty MJ, Mister R, Pearson MG. et al. 2000. Capsaicin responsiveness and cough in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax, 55:643–9. Copyright © 2000 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of relationship between cough threshold (C5) and FEV1 for subjects with COPD and asthma Reprinted from Doherty MJ, Mister R, Pearson MG. et al. 2000. Capsaicin responsiveness and cough in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax, 55:643–9. Copyright © 2000 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group.

Mechanical sputum clearance by cough is also important. The accumulation of inflammatory mucus exudates in the small airways has been recently shown to be strongly associated with disease progression (Hogg et al 2004). This occurs due to a combination of mucus hyper-secretion and impaired ciliary clearance and is likely to mechanically stimulate coughing.

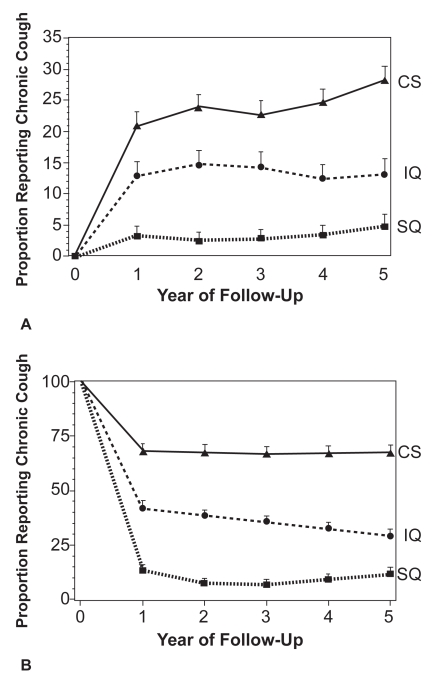

Smoking is the main risk factor for the development of COPD. Chronic bronchitis, ie, cough and sputum without airflow obstruction, develops in 50% of smokers (Siafakas et al 1995) and, with smoking cessation, stops in the majority after 1.5 years (Friedman and Siegelaub 1980). COPD develops in about 10%–20% of smokers. The lung health survey data suggest COPD patients with chronic cough are more likely to have greater number of pack-years of smoking, worse lung function, and are more likely to be current smokers (Kanner et al 1999). Smoking cessation in subjects with COPD reduced the prevalence of chronic cough by >80% after 5 years (Figure 4). It is likely that the effects of current smoking on cough are due to airway inflammation, mucus hyper-secretion, and ciliary dysfunction. The acute effect of smoking on cough reflex sensitivity in COPD is unknown. In healthy smokers the sensitivity to capsaicin is less than in healthy volunteers (Dicpinigaitis 2003).

Figure 4.

Proportion of COPD subjects reporting chronic cough by final smoking status in A: subjects not reporting cough at start of study, B: subjects reporting cough at the start of the study. CS current smoker, IQ intermittent quitters and SQ sustained quitters. Reprinted from Kanner RE, Connett JE, Williams DE. et al. 1999. Effects of randomized assignment to a smoking cessation intervention and changes in smoking habits on respiratory symptoms in smokers with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Lung Health Study. Am J Med, 106:410–16. Copyright © 1999 with permission from Excerpta Medica, Inc.

Finally, there may be important co-morbidities which contribute to cough. In one study of COPD, occult bronchiectasis was found in 50% of patients, increasing the volume of sputum to be cleared (Patel et al 2004). Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, which is reported to be a common cause of cause of cough in chronic cough clinics, also seems to be common in patients with severe airflow obstruction (Casanova et al 2004). Laryngopharyngeal reflux (in the absence of typical heartburn) may be an important cause of chronic cough (Westcott et al 2004) but its prevalence in COPD is unknown.

How much do patients with COPD cough?

Surveys of respiratory symptoms in the general population, show a prevalence of 11.9% for chronic cough and sputum in young adults (European Respiratory Community Health Survey) (Cerveri et al 2003). Current smoking was by far the most significant risk factor for chronic cough. A large international survey has documented the patient reporting of frequency of symptoms in COPD (The Confronting COPD Survey [Rennard et al 2002]). Patients were asked if there had been any period of 3 months or more in the previous year when they had experienced symptoms for a few days a week, or every day. Cough was reported as frequently as breathlessness by participants (cough 70% [46% daily], breathlessness 67% [45% daily], and phlegm 60% [40% daily]). Seventy-eight percent of the patients reported at least one of these symptoms either every day or most days during a 3-month period in the past year.

In a large longitudinal sample of Danish men (n=876 random population sample), the predictive value of respiratory symptoms (including cough and sputum production) for hospitalization was examined over a 12-year period (Vestbo and Rasmussen 1989). Cough had the greatest predictive value for subsequent hospital admission due to respiratory disease (odds ratio 3.29 adjusted for age and smoking) and due to COPD (Table 2). Cough also had the highest predictive value for treatment for airflow obstruction (relative risk ratio 4.70).

Table 2.

Predictive values of respiratory symptoms on hospitalization due to COPD, expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Cough had the greatest predictive value for hospitalization even when odds ratios are adjusted for age, smoking habits and FEV1. Reprinted from Vestbo J, Rasmussen FV. 1989. Respiratory symptoms and FEV1 as predictors of hospitalization and medication in the following 12 years due to respiratory disease. Eur Respir J, 2:710–5. Copyright © 1989 with permission from European Respiratory Society Journals Ltd.

| Hospitalization due to COPD | ||

|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | Age and Smoking habits | Age, smoking habits and FEV1 |

| Cough | 5.4 (2.5–11.8) | 3.3 (1.4–7.6) |

| Mucus Hypersecretion | 5.5 (2.7–11.4) | 2.9 (1.3–6.6) |

| Chronic Bronchitis | 5.8 (2.6–12.6) | 3.2 (1.3–7.7) |

| Breathlessness | 4.2 (2.0–8.9) | 1.7 (0.7–4.1) |

Clinical studies of cough in COPD

There are two main techniques for clinically assessing cough, subjective reporting, and cough counting. There have been only a limited number of clinical studies specifically focused on these measures in COPD, mainly because of the difficulties in objectively measuring cough severity.

In other respiratory diseases, subjective scores of cough severity have a poor correlation with objective cough frequency, especially at night (Archer and Simpson 1985; Hsu et al 1994). In chronic cough patients, Hsu et al (1994) showed a significant modest correlation between daytime cough scores and cough counts, but not asthma. In COPD, our preliminary data again suggest a poor correlation between cough scores and cough frequency (Smith et al 2003). The discrepancy between subjective and objective measures of cough occurs for several reasons. Subjects probably rate the severity of their cough on more than frequency alone; length of paroxysms, the force of the cough, and the degree of disruption to daily activities and sleep may all be important. The severity of breathlessness induced by coughing in patients with more severe airflow obstruction could also be a factor.

Objective cough counting

Trained observers manually counting the number of cough sounds from sound or video recordings can achieve good levels of agreement (Woolf and Rosenberg 1964; Subburaj et al 1996). A range of healthcare professionals listening to cough sounds from patients with different diseases can accurately recognize the presence–absence of airway sputum, but are poor at specifying the patient’s disease (Smith et al 2006a). The development of an automated system for ambulatory cough counting, over at least 24 hours, would revolutionize the study of cough and its importance in respiratory disease in general, and COPD in particular. It would allow the same sort of critical assessment of cough that the measurement of FEV1 brings to breathlessness. However, the technical challenges have been formidable.

First, there is no universally accepted definition of what exactly constitutes a cough for counting purposes – should a peel of coughs (ie, series of cough noises in one breath) constitute a single “cough”? The intuitive way to manually count coughs is to count the number of explosive cough phases. The explosive portion of the sound is the component the human ear recognizes as the cough (Figure 5A). This technique becomes difficult in long peels of coughing with multiple explosive phases of progressively diminishing amplitude (Figure 5B). One way to resolve this difficulty is to quantify cough in terms of the amount of time spent coughing, ie, the number of seconds that contain at least one explosive cough sound (Smith et al 2002), but this measure does give any information about cough amplitude.

Figure 5.

Cough waveform patterns for (a) typical cough sound with a single explosive phase and (b) peel of cough sounds with multiple explosive phases.

Since the human ear can tell when someone in the vicinity is coughing as opposed to talking, or washing the dishes, it would be imagined that establishing a computer algorithm based on sound analysis to do the same would be a relatively simple matter. However, this is not the case. Excluding background noise and other respiratory noises such as guttural speech, throat clearing, and sneezing all have proved difficult. Furthermore, the cough acoustic signals from subjects of different gender, age, with/without sputum, and with different diseases are enormously variable. If the acoustic features of spontaneously occurring cough sounds are studied, it becomes clear that the variability of the waveforms within an individual subject can be greater than that between individuals with the same condition, and for many features the variability is greater than between different diseases (Smith et al 2004). The large variation in the acoustic properties of cough sounds is probably the explanation for the lack of an automated cough counting system to date.

The first reports of making sound recordings to quantify cough frequency were published in the 1960s (Woolf and Rosenberg 1964). Initially laboratory-based studies were performed in heterogenous groups of patients (Woolf and Rosenberg 1964; Loudon and Brown 1967; Loudon 1976). In the past decade improvements in recording technology have allowed ambulatory recordings to be made, although equipment has been cumbersome and battery-life insufficient for continuous recordings (Hsu et al 1994; Chang et al 1997). These studies have always been limited in size and scope by the laborious task of manually counting the cough sounds. With further improvements in digital recording techniques, data compression, and storage the process is finally becoming automated, with computer algorithms identifying cough sounds from their specific acoustic features with improving sensitivity and specificity (Dalmasso et al 1999; Hiew et al 2002; Subburaj et al 2003; Morice et al 2004). Nevertheless, the studies on automated ambulatory devices remain extremely laborious, due to the need to constantly re-validate refinements in technology and algorithms against gold standard manual counting. Two other techniques for counting cough have been suggested using impedance plethysmography (Coyle et al 2005) or electromyography (Hsu et al 1994; Munyard et al 1994) as second signals, but these are expensive, cumbersome and not validated for ambulatory use.

Quantifying cough in COPD

Despite the lack of an available automated technique, it has been possible, although extremely laborious, to perform studies manually counting cough in COPD patients. However, due to limited battery life of the recording devices, early studies may have missed periods early in the morning, when cough is particularly important for COPD patients. We have studied ambulatory cough in moderately severe stable COPD patients complaining of cough (Smith et al 2003).

Patients with COPD cough much more by day (median of 12.3 seconds coughing per hour, cs/hour) than by night (1.63 cs/hour). Cough frequency is unrelated to FEV1 (r=0.03, p=0.88) and relates moderately to cough challenge threshold to citric acid (r=0.48, p=0.01). In these patients selected for the symptom of cough, the relationships between cough frequency and subjective scores of cough are weak to moderate (daytime r=0.37, p=0.03; overnight r=0.48, p=<0.01); the better agreement between night-time cough counts and subjective scores may indicate some sleep disturbance. There is real hope that automated cough counters will be developed in the next few years which will allow the exploration of these relationships in diverse and much larger patient groups.

Consequences of cough in COPD

Quality of life

The presence of cough is commonly reported by patients with COPD but this gives no information about the impact of the symptom on health status. The St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Medical Research Council respiratory symptoms questionnaires have been extensively used and have both cross-sectional and longitudinal validity. During the development of the SGRQ a multivariate model was used to assess the effect of a number of measures of disease activity on the total score (Jones et al 1992). The reported presence of cough accounts for only a small portion of the variance in SGRQ scores (approximately 2%) compared with breathlessness or wheeze. However, only 50% of the variance is explained by the traditional clinical measures of disease severity. Furthermore the mean FEV1 in the patients studied was 47%; hence breathlessness is likely to be their overwhelming symptom.

More recently, cough-specific quality of life measures have been developed in the US (French et al 2002) and in the UK (Birring et al 2003). These questionnaires have been developed for use in patients attending chronic cough clinics. Whether these measures have validity in other conditions such as COPD is unexplored. Preliminary data have been presented on the scores for the LCQ and the CQLQ, and shown comparable impairment of cough specific quality of life between COPD and chronic cough subjects (Yaman et al 2003).

Effects of treatments on cough in COPD

It could be suggested that cough is a protective mechanism for sputum clearance in COPD, and that suppressing cough with anti-tussives might even be harmful. However, a clinical trial of cough during antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of cystic fibrosis provides some insight into this problem (Smith et al 2006b). In this study, cough rates were very high during the acute phase and correlated with both systemic and airway measures of inflammation. However, after antibiotic treatment, cough rates were substantially lower, and correlated with sputum volume, but not with inflammatory markers. This advances the concept that treatment attacking the inflammatory component of cough in COPD might be symptomatically helpful without impeding sputum clearance.

The extent to which inhaled bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and anti-cholinergics affect cough in COPD is not clear. The relationships between prescribed treatment and cough reflex sensitivity in COPD were examined in the study by Doherty et al (2000). There was no difference in the cough reflex sensitivity between patients on and off inhaled steroids, but patients using inhaled anti-cholinergic treatment had a more sensitive cough reflex than those without. In COPD patients complaining of cough and assessed by objective cough frequency a similar pattern is seen (Smith et al 2004). There was no association between cough frequency and dose of inhaled steroid. Subjects on inhaled long-acting β2-agonists had lower cough rates than those just on short-acting treatments but the opposite effect was seen for inhaled anti-cholinergic treatments, with treated patients having higher cough rates. A study of cough clearance of radio-labeled particles in COPD found clearance following ipratropium bromide was slower than following placebo (Bennett et al 1993). This suggestion of differential effects of treatments on cough in COPD needs re-appraizing in large, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

There are very few studies of the effect of cough suppressants in COPD. A small laboratory-based study (8 patients) used a rather unreliable method of quantifying cough; patients recorded their own coughs using a manual click device, but found a 30% reduction in cough rate after codeine syrup compared with placebo. The study may have been only single blind, however (codeine syrup is bitter to taste) (Sevelius and Colmore 1966).

Recently we have published a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial on the effect of two doses of codeine (60 mg) on cough frequency in patients with COPD (Smith et al 2005). Patients performed day and overnight cough recordings at baseline to confirm a minimum cough rate, then 20 subjects were studied at day 7 and 14 after 60-mg doses of codeine or identical placebo. Both codeine and placebo were associated with lower cough frequency compared with baseline, but there was no significant difference between codeine and placebo in cough scores or citric acid cough sensitivity. This underscores the critical importance of placebo-controlled studies in cough in COPD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it is likely that multiple mechanisms contribute to stimulation of cough in COPD and their relative contributions remain to be elucidated. Established cough suppressants may not be effective in improving cough in COPD but an approach aimed at suppressing the inflammatory component of cough may be effective.

Cough is a significant predictor of decline in patients with established airflow obstruction and may be an indicator of mild disease in case-finding in the community. Cough is independently associated with disability in COPD, but evidence from patient health status scores suggest that breathlessness rather than cough is increasingly important as severity increases. The interactions between cough and breathlessness with regard to health status have not been investigated.

Stable COPD patients cough much more by day than night and patients seem to be sensitive to the time spent coughing, as in large surveys the presence of the symptom is very commonly reported. Objective cough counts provide new insights, and ultimately automated cough counting will provide a new objective outcome measures in COPD. This will allow exploration of areas about which we know very little, such as correlations with inflammatory markers and precise changes to cough during acute exacerbations of COPD.

References

- Archer LN, Simpson H. Night cough counts and diary card scores in asthma. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:473–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.5.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett WD, Chapman WF, Mascarella JM. The acute effect of ipratropium bromide bronchodilator therapy on cough clearance in COPD. Chest. 1993;103:488–95. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.2.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik A, Seemungal TA, Sapsford RJ, et al. Relation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2000;55:114–200. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BiernackI WA, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ. Increased leukotriene B4 and 8-isoprostane in exhaled breath condensate of patients with exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:294–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) Thorax. 2003;58:339–43. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brightling CE, Mckenna S, Hargadon, et al. Sputum eosinophilia and the short term response to inhaled mometasone in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60:193–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.032516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt CW, Schappert SM. Ambulatory care visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments: United States, 1999–2000. Vital Health Stat. 2004;13:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning BJ, Mazzone SB, Meeker SN, et al. Identification of the tracheal and laryngeal afferent neurones mediating cough in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. J Physiol. 2004;557:543–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova C, Baudet JS, Del Valle Velasco M, et al. Increased gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:841–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00107004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveri I, Accordini S, Corsico A, et al. Chronic cough and phlegm in young adults. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:413–17. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00121103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AB, Newman RG, Phelan PD, et al. A new use for an old Holter monitor: an ambulatory cough meter. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1637–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudry NB, Fuller RW, Pride NB. Sensitivity of the human cough reflex: effect of inflammatory mediators prostaglandin E2, bradykinin, and histamine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:137–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle M, Keenan B, Henderson L, et al. Evaluation of an ambulatory system for the quantification of cough frequency in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cough. 2005;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmasso F, Righini P, Didonna V, et al. A non-invasive cough monitoring system based on a portable phonometer [abstract] Eur Resp J. 1999:208s. [Google Scholar]

- Dicpinigaitis PV. Capsaicin responsiveness in asthma and COPD. Thorax. 2001;56:162. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.2.161b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicpinigaitis PV. Cough reflex sensitivity in cigarette smokers. Chest. 2003;123:685–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty MJ, Mister R, Pearson MG, et al. Capsaicin responsiveness and cough in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2000;55:643–9. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.8.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J. 1977;1:1645–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6077.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French CT, Irwin RS, Fletcher KE, et al. Evaluation of a cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Chest. 2002;121:1123–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB. Changes after quitting cigarette smoking. Circulation. 1980;61:716–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.4.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Kamio Y, Hashimoto T, et al. Airway cough sensitivity to inhaled capsaicin and bronchial responsiveness to methacholine in asthmatic and bronchitic subjects. Respirology. 1998;3:267–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.1998.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompertz S, Bayley DL, Hill SL, et al. Relationship between airway inflammation and the frequency of exacerbations in patients with smoking related COPD. Thorax. 2001;56:36–41. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiew Y, Smith JA, Cheetham BMG, et al. DSP algorithm for cough identification and counting. IEEE Proceedings of International Conference on Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), IV; 2002. p. 3891. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, Stone RA, Logan-Sinclair RB, et al. Coughing frequency in patients with persistent cough: assessment using a 24 hour ambulatory recorder. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1246–53. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07071246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, et al. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:1321–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos GF, De Swert KO, Schelfhout V, et al. The role of neural inflammation in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;992:218–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner RE, Connett JE, Williams DE, et al. Effects of randomized assignment to a smoking cessation intervention and changes in smoking habits on respiratory symptoms in smokers with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Lung Health Study. Am J Med. 1999;106:410–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapperre TS, Snoeck-Stroband JB, Gosman MM, et al. Dissociation of lung function and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:499–504. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-112OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon RG. Smoking and cough frequency. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:1033–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.5.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudon RG, Brown LC. Cough frequency in patients with respiratory disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;96:1137–43. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.96.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [MRC] Medical Research Council. Definition and classification of chronic bronchitis for clinical and epidemiological purposes. A report to the Medical Research Council by their Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis. Lancet. 1965;1:775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montuschi P, Kharitonov SA, Ciabattoni G, et al. Exhaled leukotrienes and prostaglandins in COPD. Thorax. 2003;58:585–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice A, Dane A, Walmsley A. Automated cough recognition and counting [abstract] Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A200. [Google Scholar]

- Morice AH. Inhalation cough challenge in the investigation of the cough reflex and antitussives. Pulm Pharmacol. 1996;9:281–4. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice AH, Kastelik JA, Thompson R. Cough challenge in the assessment of cough reflex. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:365–75. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munyard P, Busst C, Logan-Sinclair R, et al. A new device for ambulatory cough recording. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1994;18:178–86. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950180310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel IS, Vlahos I, Wilkinson TM, et al. Bronchiectasis, exacerbation indices, and inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:400–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-648OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–76. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley PM, et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International Survey. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:799–805. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.03242002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers SR, Timens W, Kaufmann HF, et al. Comparison of induced sputum with bronchial wash, bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial biopsies in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:109–15. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15110900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius H, Colmore JP. Objective assessment of antitussive agents in patients with chronic cough. J New Drugs. 1966;6:216–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siafakas NM, Vermeire P, Pride NB, et al. Optimal assessment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The European Respiratory Society Task Force. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1398–420. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08081398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA. The objective measurement of cough. University of Manchester; 2004. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Ashurst LA, Jack S, et al. The description of cough sounds by healthcare professionals. Cough. 2006a;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Earis A, Woodcock AA, et al. Acoustic properties of spontaneous coughs in common respiratory diseases [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A200. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Hambleton E, Earis J, et al. Measurements of cough in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [abstract] Thorax. 2003;58(Supp III):iii48. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Hambleton E, Earis, et al. The effect of codeine on objective measurement of cough in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Hiew Y, Cheetham B, et al. Cough seconds: a new measure of cough [abstract] Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2002;165:A832. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Owen EC, Jones AM, et al. Objective measurement of cough during pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2006b doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subburaj SAVH, Quanten S, Berkmans D. An algorithm to automatically identify cough sounds from clinical recordings [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2003;22:172S. [Google Scholar]

- Subburaj S, Parvez L, Rajagopalan TG. Methods of recording and analysing cough sounds. Pulm Pharmacol. 1996;9:269–79. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1996.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schayck CP, Loozen JM, Wagena E, et al. Detecting patients at a high risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practice: cross sectional case finding study. BMJ. 2002;324:1370–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Lange P. Can GOLD Stage 0 provide information of prognostic value in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:329–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1530–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestbo J, Rasmussen FV. Respiratory symptoms and FEV1 as predictors of hospitalization and medication in the following 12 years due to respiratory disease. Eur Respir J. 1989;2:710–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hertzen L, Reunanen A, Impivaara O, et al. Airway obstruction in relation to symptoms in chronic respiratory disease—a nationally representative population study. Respir Med. 2000;94:356–63. doi: 10.1053/rmed.1999.0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westcott CJ, Hopkins MB, Bach K, et al. Fundoplication for laryngopharyngeal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CR, Rosenberg A. Objective assessment of cough suppressants under clinical conditions using a tape recorder system. Thorax. 1964;19:125–30. doi: 10.1136/thx.19.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaman MN, Patterson N, Heaney LG, et al. A cross-sectional comparison of two cough specific health related quality of life questionnaires [abstract] Thorax. 2003;58:iii47. [Google Scholar]