Abstract

Disturbance of the tight junction (TJ) complexes between brain endothelial cells leads to increased paracellular permeability, allowing leukocyte entry into inflamed brain tissue and also contributing to edema formation. The current study dissects the mechanisms by which a chemokine, CCL2, induces TJ disassembly. It investigates the potential role of selective internalization of TJ transmembrane proteins (occludin and claudin-5) in increased permeability of the brain endothelial barrier in vitro. To map the internalization and intracellular fate of occludin and claudin-5, green fluorescent protein fusion proteins of these TJ proteins were generated and imaged by fluorescent microscopy with simultaneous measurement of transendothelial electrical resistance. During CCL2-induced reductions in transendothelial electrical resistance, claudin-5 and occludin became internalized via caveolae and further processed to early (EEA1+) and recycling (Rab4+) endosomes but not to late endosomes. Western blot analysis of fractions collected from a sucrose gradient showed the presence of claudin-5 and occludin in the same fractions that contained caveolin-1. For the first time, these results suggest an underlying molecular mechanism by which the pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL2 mediates brain endothelial barrier disruption during CNS inflammation.

The blood-brain barrier is situated at the cerebral endothelial cells and their linking tight junctions. Increased brain endothelial barrier permeability is associated with remodeling of inter-endothelial tight junction (TJ)2 complex and gap formation between brain endothelial cells (paracellular pathway) and/or intensive pinocytotic vesicular transport between the apical and basal side of brain endothelial cells (transcellular pathway) (1, 2). The transcellular pathway can be either passive or active and is characterized by low conductance and high selectivity. In contrast, the paracellular pathway is exclusively passive, being driven by electrochemical and osmotic gradients, and has a higher conductance and lower selectivity (3).

Brain endothelial barrier paracellular permeability is maintained by an equilibrium between contractile forces generated at the endothelial cytoskeleton and adhesive forces produced at endothelial cell-cell junctions and cell-matrix contacts (1–3). A dynamic interaction among these structural elements controls opening and closing of the paracellular pathway and serves as a fundamental mechanism regulating blood-brain exchange. How this process occurs is under intense investigation. Two possible mechanisms may potentially increase paracellular permeability: phosphorylation of TJ proteins and/or endocytosis of transmembrane TJ proteins.

Changes in TJ protein phosphorylation seem to be required to initiate increased brain endothelial permeability and a redistribution of most TJ proteins away from the cell border (4–8). Endocytosis may also be involved in remodeling TJ complexes between endothelial cells. Several types of endocytosis may be involved in TJ protein uptake, including clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis (for reviews, see Refs. 8 and 9–12). After first forming cell membrane-derived endocytotic vesicles, these vesicles fuse with early endosomes whose contents are further sorted for transport to lysosomes for degradation or recycling back to the plasma membrane for reuse (11).

Although there is a lack of definitive knowledge regarding endocytotic internalization of brain endothelial cell TJ proteins, several studies on epithelial cells have indicated that occludin may be internalized via caveolae-mediated endocytosis whereas ZO-1, claudin-1, and junctional adhesion molecules-A may undergo macropinocytosis in response to stimuli such as TNF-α and INF-γ (13, 14). In contrast, there is evidence that Ca2+ may induce internalization of claudin-1 and occludin via clathrin-coated vesicles (8, 14–16). All of these studies pinpoint endocytosis as an underlying process in TJ complex remodeling and redistribution, and thus regulation of paracellular permeability in epithelial cells.

The present study examines whether internalization of transmembrane TJ proteins could be one process by which adhesion between brain endothelial cells is changed during increased paracellular permeability. Our results show that a pro-inflammatory mediator, the chemokine CCL2, induces disassembly of the TJ complex by triggering caveolae-dependent internalization of transmembrane TJ proteins (occludin and claudin-5). Once internalized, occludin and claudin-5 are further processed to recycling endosomes awaiting return to the plasma membrane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River (Portage, MI). bEnd.3 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). For cell culture growth the following reagents were used: DMEM, 10% inactivated fetal calf serum, HEPES, glutamine, antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen), heparin (Sigma-Aldrich), and endothelial growth factor supplement from BD Biosciences. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1 or CCL2) was from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). All chemicals, other than those listed below, were from Sigma-Aldrich.

For tracer studies the following reagents were obtained from Invitrogen: Texas Red-Dextran, Alexa596-cholera toxin and BODIPY-TR-ceramide, Texas Red-transferrin. For Western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry the following antibodies were used: TJ proteins were detected with mouse anti-occludin or anti-claudin-5 antibodies (Invitrogen); different type of vesicles were labeled with anti-Rab4, -caveolin-1, -α-adaptin antibodies (all from BD Biosciences), and anti-EEA1 and -lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) antibodies (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA); green fluorescent protein (GFP) was detected by anti-GFP antibody from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Mountain View, CA); antibody to cytochrome P450 reductase and vimentin were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA), while antibody to calpain was from Sigma-Aldrich. The secondary antibodies, anti-mouse-HRP and anti-rabbit-HRP, were from Bio-Rad, whereas anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated either with FITC or Texas Red were from Vector Laboratory, (Burlingame, CA).

siRNA oligonucleotides targeting three different regions of caveolin-1 and α-adaptin, GAPDH siRNA, and siPortNeoFX siRNA transfection reagent were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA).

Mouse occludin and claudin-5 cDNA were obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). The pAcGFP-C-plasmid vector and Fusion Dry-Down PCR cloning kit were from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Mountain View, CA). LipofectAMINE 2000 and antibiotic G418 were from Invitrogen. A Live/Dead assay kit was also from Invitrogen. A ProteoExtract Subcellular Proteome Extraction kit was from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ). Sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotin-amido)ethyldithioproprionate, protein assay kit, and chemiluminescent HRP substrate kit for Western blotting were from Pierce.

Brain Endothelial Cell Culture

Mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells (mBMECs) were prepared and cultured using a previously described protocol (7, 17).

GFP-tagged Occludin and Claudin-5

Whole length claudin-5 and occludin were cloned and tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) on the N-terminal side. For amplification, the following primers were used: occludin 5′-AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGTCTGTGAGGCCT-3′ and 5′-AGAATTCGCAAGCTTCTAGGTTTTCCGTCT-3′; claudin-5 5′-AAGGCCTCTGTCGACATGGGGTCTGCAGCGTTGGA-3 and 5′-AGAATTCGCAAGCTTTAGACATAGTTCTTCTTGTCGTAATC-3′, incorporating Sall and HindIII sites. The occludin and claudin-5 cDNA fragments were cloned in-frame with an N-terminally fused GFP sequence into a pAcGFP-C-plasmid vector using an In Fusion Dry-Down PCR cloning kit. Purified plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. bEnd.3 cells were transfected with these plasmids for 24 h using LipofectAMINE 2000. The control plasmid, pAcGFP1-C, was used as a positive control for transfection and expression in bEnd.3 cells. Negative controls were untransfected or mock transfected cells. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were exposed to media containing G418 (1 mg/ml) for 10–14 days to generate a stable cell line. Surviving cells were ring-cloned and grown to confluence.

Tracer Study

The macropinocytosis marker, lysine-fixable Texas Red-Dextran (1 mg/ml), the caveolae internalization marker, Alexa596-cholera toxin and BODIPY-TR ceramide (10 μg/ml and 5 μm), and the clathrin internalization marker, Texas Red-transferrin (5 μg/ml), were dissolved in ice-cold medium (DMEM) and added to the apical side of mBMECs or bEnd.3 monolayers with and without CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Monolayers were kept at 4 °C for 30 min to allow tracer accumulation on the cell surface and then incubated for 0–60 min at 37 °C. At this time point, TEER was simultaneously measured, and cells were subject to time-lapse microscopy analysis.

Cell Treatment and Inhibitors

Inhibitors were introduced 30 min prior to treatment with CCL2. Control cells were exposed to assay media (DMEM) without inhibitors. The following inhibitors were used: 0.4 m sucrose (clathrin-dependent internalization), 5 μm Filipin III (caveolin-dependent internalization), 10 μm 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (macropinocytosis), 50 nm bafilomycin A1 (vesicle recycling), 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (protein synthesis), and 1 μm lactacystein (proteasome). Cell viability assays were performed to exclude possible toxic effects of inhibitors. The effect of cell treatment and inhibitors was evaluated by Western blot, immunocytochemistry, or biotinylation assays.

In a separate set of experiments the reversibility of inhibition of caveolae formation was tested. Cells were pretreated and treated with 10 mm MβCD for 30 min and then HEPES-buffered DMEM with or without of water soluble cholesterol (400 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) was added before treatment with CCL2.

Immunofluorescence

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then preincubated in blocking solution containing 5% normal goat serum and 0.05% Tween in phosphate-buffered saline. Samples were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Reactions were visualized by fluorescein-conjugated anti-mouse and/or anti-rabbit antibodies. All samples were viewed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Zeiss, Germany).

Evaluation of Colocalization

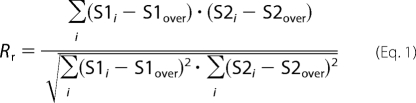

Images for quantitative florescence analysis were acquired using a Zeiss LSM META 510 laser scanning microscope with sequential mode to avoid interference between channels and saturation. Contrast brightness and the pinhole were held constant. Cells from five independent experiments and three areas per experiment were analyzed. For each area, z-stacks of five consecutive optical sections were acquired. To quantify the colocalization of occludin, GFP-occludin, claudin-5, and GFP-claudin-5 with various vesicle markers, each z-optical section was analyzed using the colocalization finder plug-in of ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). The background contribution to colocalization was corrected using the formula: corrected colocalization = measured colocalization − background colocalization/1 − background colocalization/100 (18). The colocalization of occludin and claudin-5 with vesicular markers was estimated by Pearson's correlation coefficient (Rr), determined as,

|

where S1 represents the signal intensity in pixels in channel 1, and S2 represents the signal intensity in pixels in channel 2; S1over and S2 over reflect the average intensity of these respective channels. The Pearson coefficient ranges between −1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlations between two images). A coefficient of 0 means no correlation between two images (19).

Time-lapse Imaging

Time-lapse microscopy was performed using a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany, objective 40×). The stage was maintained at 37 °C by a temperature hood. The time-lapse experiments were conducted for 0–2 h. Images were collected every 5 min using an Olympus DP-30 charge-coupled device camera.

TEER

TEERs were measured by an electrical cell impedance sensor system (ECIS, Model 1600R, Applied BioPhysics). Briefly, bEnd.3 cells (3 × 105 cells per ml), stably transfected with GFP-occludin or GFP-claudin-5, were seeded on gold microelectrodes (5 × 10−3 cm2) in polycarbonate wells. bEnd.3 cells were grown in 8-well ECIS array consists of 10 electrode (8W10E) until stable resistances of 140 Ω were reached. The resistance was measured at a frequency of 400 Hz and serves as an indicator of the expression of cell-cell junctions and barrier tightness (20). All experiments were performed in serum-free medium. Electrical impedance was recorded every 1 min for 2 h after CCL2 exposure. Impedance values were normalized by dividing each value by the level of impedance measured just prior to the addition of CCL2. Results from triplicate samples were averaged.

Brain Endothelial Cell Monolayer Permeability

The permeability of brain endothelial cell monolayers to inulin-FITC was measured as described in our previous studies (7, 17).

Cell Transfection

siRNA oligonucleotides targeting three different regions of caveolin-1 and α-adaptin were used. The best inhibition of caveolin-1 and α-adaptin was achieved after transfection with a mixture of three-selected siRNA oligonucleotides. mBMEC and bEnd.3 cells were transfected with annealed siRNAs by the use of siPortNeoFX siRNA transfection Agent and were subcultured 24 h later. Cells were used 48 h later for experiments. Control cells were transfected with control oligonucleotides or with GAPDH siRNA as positive controls as well as the manufacturer's negative control.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed with the following antibodies: mouse anti-occludin, -claudin-5, or -caveolin-1. Immunoblots were exposed to secondary anti-mouse or rabbit-HRP conjugated antibody, visualized with a chemiluminescent HRP substrate kit, and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Fractional Analysis of TJs

Fractional analysis of TJ proteins was performed utilizing a ProteoExtract Subcellular Proteome Extraction kit. Membrane, cytosolic, cytoskeletal, and nuclear fractions were separated. Specificity of fractions was confirmed using anti-cytochrome P450 reductase (membrane fraction), anti-calpain (cytosolic fraction), and anti-vimentin (actin cytoskeletal fraction) antibodies. For “total cell lysate” samples, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, scraped, and rinsed in 1 ml of the lysis buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, with 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, and 1% deoxycholate).

Sucrose Gradient Analysis

Sucrose gradient analysis was performed as previously described (21). Cells were lysed in 1 ml of ice-cold 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in MNE buffer (25 mm MES (pH 6.5), 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mm NaF) for 20 min. Lysates were then homogenized with 20 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer on ice and centrifuged for 10 min at 2000 rpm at 4 °C to remove nuclei. Clarified postnuclear supernatants were diluted 1:2 with 80% (w/v) sucrose in MNE buffer, placed at the bottom of 12.5-ml ultracentrifuge tubes (Beckman), and overlaid gently with 6 ml of 35% and 3 ml of 5% sucrose. The resulting 5–40% discontinuous sucrose gradient was centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 20 h in a swinging bucket rotor (model SW41, Beckman Instruments) at 4 °C to separate the low density caveolae. After centrifugation, fractions (0.92 ml) were collected from the top to the bottom of the gradient and used for SDS-PAGE, immunoprecipitation, and Western blot analysis.

Biotinylation Assay for Endocytosis and Recycling

Cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotin-amido)ethyldithioproprionate at 0 °C, followed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline containing 50 mm NH4Cl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.1 mm CaCl2 to quench any excess of sulfosuccinimidyl-2-(biotin-amido)ethyldithioproprionate. Cells were then lysed to quantify the surface biotinylated proteins. To determine the total amount of occludin and claudin-5 in the cells using the biotin reagent, cells were first lysed with lysis buffer (5 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, and protease inhibitor mixture) and then biotinylated. Subsequently, any unreacted biotin was quenched.

For internalization assay, after surface biotinylation, cells were incubated with CCL2 at 37 °C for different time periods (0–60 min) and then washed twice at 4 °C with glutathione stripping solution (50 mm glutathione, 75 mm NaCl, 75 mm NaOH, and 1% bovine serum albumin) to release the biotin label from proteins at the cells surface. Cells were then suspended in lysis buffer. Cell lysates were centrifuged, and the supernatants were incubated with streptavidin beads to collect internalized biotin-bearing proteins. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting.

For recycling/degradation assay, after biotinylation of the cell membrane surface proteins, cells were treated with CCL2 or vehicle for different time periods and then washed with ice-cold glutathione solution. Stripped cells were then reincubated at 37 °C in the presence or absence of CCL2. At given time points, cells were then subjected to a second glutathione stripping before being lysed in lysis buffer and processed for Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Transmembrane TJ Proteins, Occludin and Claudin-5, during Brain Endothelial Barrier “Opening” and Recovery

Previous studies demonstrated that occludin and claudin-5 both undergo delocalization from the plasma membrane and phosphorylation during CCL2-induced blood-brain barrier disruption (7, 17). To follow the dynamics of these transmembrane TJ proteins during brain endothelial barrier “opening,” we used two plasmids expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) together with claudin-5 or occludin. The GFP was fused with the N-terminal sequence of both TJ proteins, because the C terminus of these proteins is engaged with TJ scaffold proteins (ZO-1 and ZO-2), actin filaments, as well as a variety of signaling molecules, and it is required for TJ barrier function (22, 23).

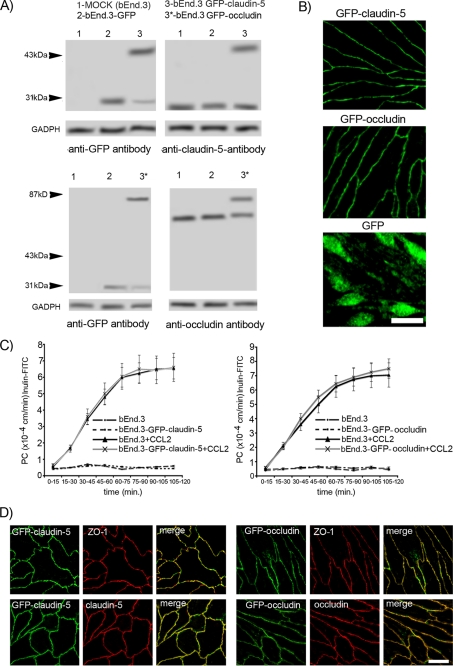

We generated stable GFP-claudin-5- and GFP-occludin-expressing bEnd.3 cells (Fig. 1, A and B). The ratio between GFP-claudin-5 and endogenous claudin-5 in GFP-claudin-5-expressing bEnd.3 cells as well as GFP-occludin and endogenous occludin in GFP-occludin-expressing bEnd.3 cells (distinguishable by molecular weight) was ∼1.2. Monolayers of GFP-claudin-5- and GFP-occludin-expressing bEnd.3 cells did not differ in the permeability coefficient for inulin-FITC compared with nontransfected cells, implying that GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin expression did not interrupt barrier integrity. Also, there were no differences between the different monolayers in the permeability response to recombinant CCL2 (Fig. 1C). GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin were colocalized to the cell border and associated with ZO-1 as with endogenous claudin-5 and occludin (Fig. 1D). In contrast to bEnd.3 cells transfected with GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin, there was no cell border localization after transfection with AcGFP (Fig. 1B). In Western blots of cells transfected with GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin, there was a faint band detected by anti-GFP at the level free GFP (Fig. 1A), which may represent a degradation product. The results from Fig. 1B, though, indicate that this cannot account for the cell border localization for in GFP-claudin-5- and GFP-occludin-transfected cells.

FIGURE 1.

A, whole cell lysates of mock transfected bEnd.3 cells (1), bEnd.3 cells transfected with AcGFP plasmid (2), and bEnd.3 cells transfected with GFP-claudin-5 (3) or GFP-occludin (3*) plasmid were immunoblotted with anti-claudin-5 or anti-occludin antibodies and anti-GFP antibody. In each lane the same amount of total protein was applied. B, bEnd.3 cells stably transfected with GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin expressed the tagged protein at cell borders. In bEnd.3 cells transfected with AcGFP only (GFP), staining was not localized to the cell border. Scale bar, 20 μm. C, permeability coefficient for inulin-FITC in two stably transfected bEnd.3 cell lines expressing GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin, treated without or with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 2 h. D, staining with anti-claudin-5 and anti-ZO-1 or anti-occludin and anti-ZO-1 antibodies, confirmed the correct localization of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin proteins in bEnd.3 cells, with colocalization in merged images. Scale bar, 20 μm.

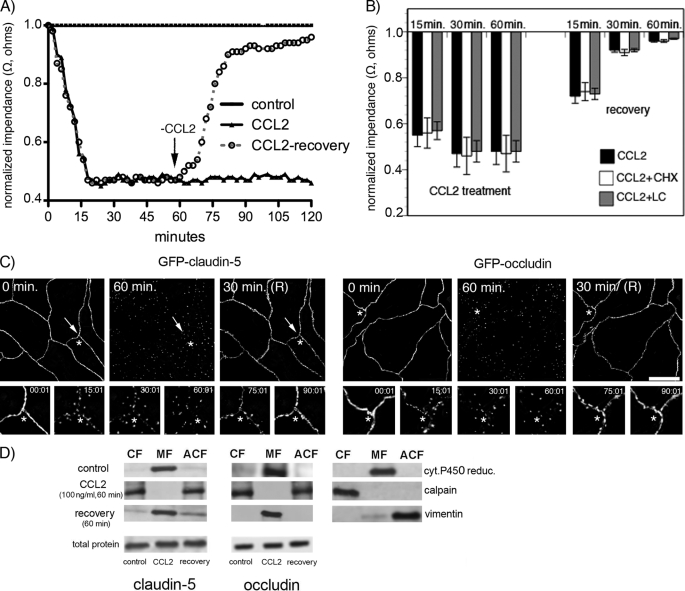

Analyzing the fate of occludin and claudin-5 in brain endothelial cells (mBMECs) exposed to CCL2, we found that disappearance of these proteins from the plasma membrane was not coupled with changes in total occludin and claudin-5 protein suggesting that degradation does not occur (Fig. 2). Exposure to CCL2 (60 min) followed by removal of the CCL2 stimulus (CCL2-recovery) was associated with complete functional recovery of the brain endothelial barrier over about 60 min as estimated by TEER (Fig. 2A). Treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide, to deplete any potential intracellular “de novo” pool of occludin and claudin-5, or a proteasome inhibitor, lactacystein, to inhibit degradation of occludin and claudin-5, did not affect the course of brain endothelial barrier recovery (degree or temporal pattern) (Fig. 2B). These results strongly support that redistribution of existing TJ proteins plays a critical role in altering (increasing and decreasing) barrier permeability rather than degradation or de novo synthesis.

FIGURE 2.

A, mBMEC monolayers were treated with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) in serum-free medium for the indicated periods (0–120 min). TEER was evaluated during this time period by ECIS assay. In a separate set of experiments after 60 min of CCL2 treatment (100 ng/ml), the CCL2 was removed by replacing media with fresh DMEM, and the cells were observed for an additional 60 min (+recovery). Each TEER tracing represents an average of three replicate wells and from three independent experiments. Impedance values were normalized by dividing by the impedance measured just prior to the addition of CCL2. B, the value of TEER of brain endothelial barrier in the presence or absence of CCL2 and 5 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) or 1 μm lactacystein (LC) as well as during the recovery time. Both inhibitors, CHX and LC, did not disturb the brain endothelial barrier opening or recovery. Data represent an average ± S.D. for n = 5 independent experiments. C, time-lapse confocal microscopy. bEnd.3 monolayers, expressing either GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin, were exposed to CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Images were obtained every 5 min over a time period of 0–120 min. After 60 min of treatment, CCL2 was removed from cells by replacing media with fresh DMEM, and the cells were observed for an additional 60 min. The representative images show some critical time points during CCL2-induced alterations in brain endothelial barrier permeability and during recovery. There is a fragmented pattern of occludin and claudin-5 staining at the cell-cell border of endothelial cells during CCL2 exposure, but this returns to a “control” pattern of staining along the cell borders after CCL2 removal. *, the location shown in magnification in the lower images; arrows indicate alterations in the localization GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin in the presence of CCL2. Scale bar, 20 μm. D, biochemical changes in occludin and claudin-5 after CCL2 treatment. There was a redistribution of these proteins first from the membrane fraction (MF, Triton X-100-insoluble) to cytosolic (CF, Triton X-100-soluble) and actin cytoskeletal (ACF, Triton X-100-insoluble) fractions during CCL2 exposure and back to membrane fraction after removing CCL2 stimulus. To demonstrate the purity of the different fractions, cytochrome P-450 reductase, calpain, and vimentin were used as specific markers for membrane, cytosolic, and actin cytoskeletal fractions, respectively. While affecting fractional distribution of claudin-5 and occludin, CCL2 and its removal did not affect the total protein content of either protein. Blots represent one of three successful experiments.

Using time-lapse microscopy with simultaneous TEER measurement, we analyzed the kinetics of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 over 0–120 min of exposure to CCL2. CCL2 caused a marked increase in barrier permeability (Fig. 2, A and C). At the time of maximum opening (30–60 min) there was fragmented staining of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5, and these proteins were mostly localized away from the cell border (Fig. 2C). Removing CCL2 from the media led to a recovery in brain endothelial barrier integrity and a progressive return of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 to the interendothelial border over 15–30 min (Fig. 2C). The permeability coefficient for inulin-FITC (5 kDa) during CCL2 exposure and recovery showed a similar pattern. CCL2 induced significant opening of brain endothelial barrier for inulin (p < 0.001 versus control) and a similar closing of the paracellular route during recovery (supplemental Fig. S1).

Analysis of cytosolic (Triton X-100-soluble fraction), membrane, nuclear, and actin cytoskeletal fractions (Triton X-100-insoluble fraction) of brain endothelial cells during 60-min exposure to CCL2 showed a redistribution of occludin and claudin-5 from the membrane to cytosolic and actin cytoskeletal fractions during maximum opening of the brain endothelial barrier (Fig. 2D). Recovery of barrier function after removal of CCL2 was associated with a return of occludin or claudin-5 to the membrane fraction without any changes in total content of these two TJ proteins (Fig. 2D). Adding cycloheximide or lactacystein did not affect the total amount of TJ proteins during CCL2 exposure and recovery (data not shown) indicating the absence of degradation or replacement of proteins from an intracellular pool. Thus, it appears that during opening and “closing” of the TJ complex there is ongoing trafficking of occludin and claudin-5 to and from the membrane rather than degradation or de novo synthesis.

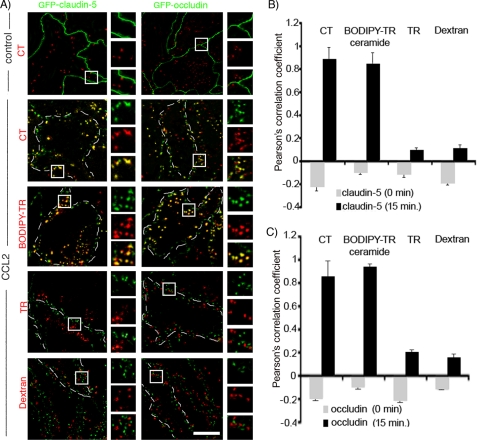

Internalization as a Pathway for Loss of Transmembrane TJ Proteins from Brain Endothelial Cell Borders

We followed the fate of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin during exposure of endothelial cells to CCL2 for 15–30 min, time points when both TEER and the permeability coefficients indicated maximal opening of the brain endothelial barrier (Figs 2A and 3 and supplemental Fig. S1). Endocytosis pathways were marked with tracers: Texas Red-transferrin (clathrin-dependent pathway), Alexa596-cholera-toxin, BODIPY-TR-ceramide (caveolae-dependent, lipid raft-dependent pathway), and Texas Red-dextran (macropinocytosis pathway). In CCL2-treated brain endothelial cell monolayers the normal pattern of occludin and claudin-5 localization with continuous staining on the cell-cell borders was replaced by punctate staining “inside” the endothelial cell, after 15 min. Wheat germ agglutinin-lectin co-staining indicated that occludin and claudin-5 was not present on the brain endothelial cell surface but was rather cytosolic (data not shown). Occludin and claudin-5 appeared colocalized with internalization vesicles, which were Alexa596-cholera-toxin- and BODIPY-Tr-ceramide-positive but not with clathrin or macropinicytotic vesicles (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Time-lapse microscopical analysis of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin internalization. A, monolayers of bEnd.3 cells were directly seeded on a eight-well gold electrode array (ECIS system) and exposed to tracer for 30 min at 4 °C. CCL2 (100 ng/ml) was then added, and samples were placed in a temperature hood at 37 °C for 0–120 min. To trace internalization pathways we used Alexa596-cholera toxin conjugate (CT, 5 μg/ml) and BODIPY-TR-ceramide (5 μm), which are specifically taken up via caveolae, Texas Red-transferrin conjugate (TR, 10 μg/ml), which is specifically taken up via clathrin-coated vesicles, and Dextran 10-kDa-Texas Red conjugate (0.5 mg/ml), which is specifically taken up via pinocytotic vacuoles or vacuole-associated actin. Example images are of the bEnd.3 cells exposed to CCL2 for 15 min. Higher magnification images of the boxed regions show localization/colocalization of certain tracers and GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin. Cell outlines are delineated by dashed white lines. Scale bar, 10 μm. B and C, quantification of colocalization of transmembrane TJ proteins claudin-5 (B) and occludin (C) with internalization vesicles based on the Pearson's correlation coefficient of GFP-claudin-5/ALEXA596-cholera toxin, GFP-claudin-5/BODIPY-TR ceramide, GFP-claudin-/Transferrin-Texas Red, GFP-claudin-5/Dextran-Texas Red, GFP-occludin/Alexa596-cholera toxin, GFP-occludin/BODIPY-TR ceramide, GFP-occludin/Transferrin-Texas Red, and GFP-occludin/Dextran Texas Red. There was a high degree of correlation between total claudin-5 and cholera toxin or BODIPY-TR ceramide (B) as well as occludin and cholera toxin or BODIPY-TR ceramide (C). Other tracers did not show any colocalization pattern. Error bars indicate ± S.D.

Quantitative analysis of colocalization of punctate occludin and claudin-5 staining with tracers for internalization vesicles showed a high degree of correlation between claudin-5 and occludin and tracers for caveole/lipid raft dependent internalization vesicles (cholera toxin or BODIPY-TR ceramide) (Pearson correlation coefficient (Rr) in the colocalized volume, 0.89, 0.85, or 0.85 and 0.94, respectively). Other tracers (transferrin and dextran) did not show any colocalization pattern (Fig. 3, B and C).

Accumulation of occludin and claudin-5 in caveolae-type vesicles was time-dependent. Over the first 5–10 min of CCL2 treatment, there was little movement into caveolae. Over 15–30 min there was significant uptake of occludin and claudin-5 into cholera-toxin-FITC- and BODIPY-Tr-ceramide-positive vesicles, closely correlating with endothelial barrier opening.

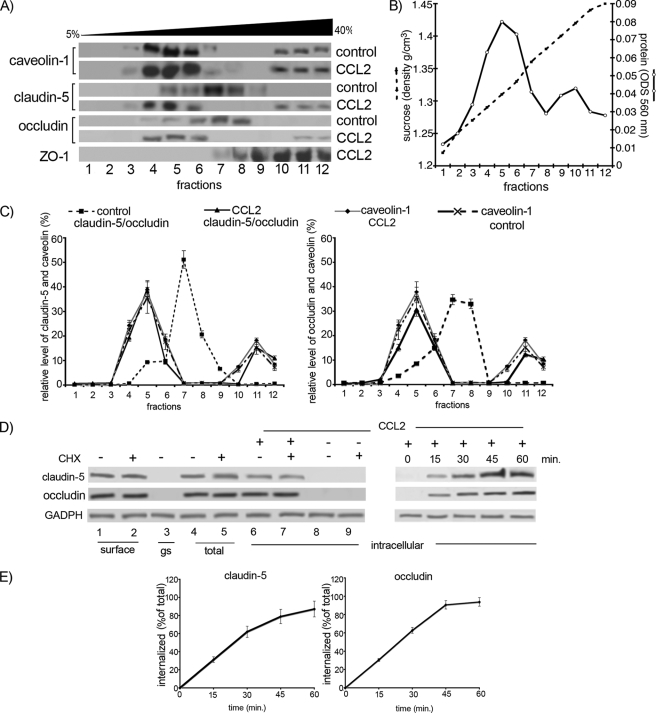

To confirm these findings, sucrose gradient (5–40%) analysis of Triton X-100-insoluble residues followed by Western blotting was performed. During CCL2 exposure, there was increased localization of claudin-5 and occludin in caveolin-enriched fractions 4–6 (∼30–40% of total protein content compared with <10% in cells not exposed to CCL2). A small caveolin-1-positive portion could be seen in the fractions 10–12, which also contained 10–20% of the total protein content of occludin and claudin-5 (Fig. 4, A–C). The amount of internalized claudin-5 and occludin upon CCL2 exposure was examined with biotinylation. During the first 15 min of CCL2 exposure, approximately a third of occludin (31 ± 3%) and claudin-5 (31 ± 4%) became internalized, whereas after 60-min exposure almost all occludin (94 ± 7%) and claudin-5 (87 ± 11%) was present intracellularly (Fig. 4, D and E). These results are consistent with the tracer and immunofluorescence-based assays (Fig. 3), as well as permeability and TEER assays (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 4.

A, mBMEC monolayers were treated with CCL2 for 30 min at 37 °C, and Triton X-100-soluble and Triton X-100-insoluble fractions were prepared. The Triton X-100-insoluble fraction was layered on a 5–40% sucrose gradient, and 12 fractions were separated (1–12). All fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-caveolin-1, -claudin-5, and -occludin antibodies. The caveolin-containing fractions (4–6 and 10–12) also contained claudin-5 and occludin in CCL2-treated mBMEC. B, each collected fraction (1 ml of total volume) was first analyzed for protein concentration (○) and sucrose density (●) using a refractometer before Western blot analysis was performed. This graph represents at least five independent experiments. C, relative levels of occludin and claudin-5 in individual fractions from control cells or cells treated with CCL2 for 30 min. The collected fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis, obtained data were scanned, and bands were analyzed by densitometry using ImageJ software. The graphs represent at least five independent experiments. Under control conditions a large portion of claudin-5 and occludin is in fractions 7 and 8, fractions without caveolin 1. However, after CCL2 treatment, claudin-5 and occludin are found in fractions 4, 5, 6, 11, and 12. These fractions are those containing caveolin-1. CCL2 had no apparent effect on the distribution of caveolin-1 between different fractions. D, internalization of surface biotinylated claudin-5 and occludin proteins. Confluent mBMECs, treated with and without cycloheximide (CHX), were surface-biotinylated at 0 °C and then exposed to CCL2 for 30 min at 37 °C to allow internalization. Any membrane-bound biotin was removed by glutathione solution (glutathione stripping, gs). Lanes 1 and 2, biotinylated claudin-5 and occludin at the cell surface; lane 3, glutathione stripping of surface biotin; lanes 4 and 5, total cell lysate; lanes 6–9, portion of biotinylated internalized proteins. Adjusted blot showing the time course (0–60 min) of internalized biotinylated claudin-5 and occludin during mBMEC exposure to CCL2. E, quantification of internalized occludin and claudin-5 during the exposure to CCL2 and opening of brain endothelial barrier. The percentage of internalized protein was estimated as the percentage of total biotinylated occludin and claudin-5. GADPH represents an internal loading control. Data represent average ± S.D. of five independent experiments.

To test the involvement of caveolin-1 in CCL2-induced occludin and claudin-5 internalization, we reduced caveolin-1 level by >90% using RNA interference against caveolin-1 (supplemental Fig. S2A). This siRNA treatment greatly decreased GFP-occludin and claudin-5 internalization (Fig. 5A). In contrast, inhibition of clathrin-dependent internalization by either 0.4 m sucrose (data not shown) or siRNA-α-adaptin only slightly affected the redistribution of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 from the endothelial cell border during CCL2 exposure (Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. S2B).

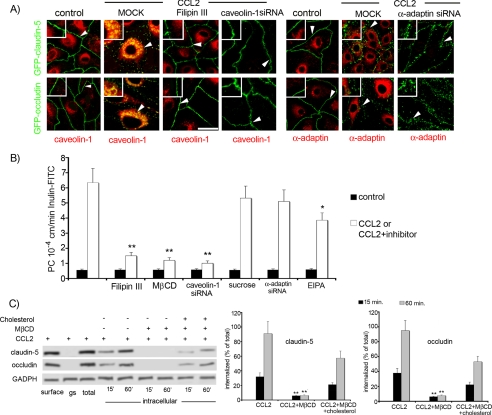

FIGURE 5.

A, to confirm that CCL2-induced claudin-5 and occludin internalization was via a caveolae-dependent pathway, we performed inhibition studies using Filipin III (10 ng/ml) or caveolin-1 siRNA. As expected, GFP-claudin-5- and GFP-occludin-expressing bEnd.3 cells exposed to mock transfection showed internalization of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin in the presence of CCL2 (100 ng/ml). In contrast, inhibition of caveolae formation with either Filipin III or transient transfection with caveolin-1 siRNA prevented CCL2-induced internalization (i.e. GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin remained at cell borders). Reduction in clathrin vesicle formation with α-adaptin siRNA had no effect on internalization. Control indicated bEnd.3 GFP-claudin-5 or GFP-occludin cells immunostained with caveolin-1 or α-adaptin in the resting condition (non-treated with CCL2). Samples were viewed on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscopy (scale bar, 20 μm). Arrowhead, localization of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin in the presence or absence of CCL2 (higher magnification insets). B, effect of inhibition of select endocytotic pathways on CCL2-induced hyper-permeability of mBMEC monolayers to inulin-FITC. CCL2 induced a marked increase in permeability versus control cells. This was significantly diminished in the presence of the following inhibitors Filipin III (10 ng/ml), MβCD (10 μm), 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride (EIPA, 10 μm) or after transient transfection with caveolin-1 siRNA but not sucrose (0.4 m) or after transient transfection with α-adaptin siRNA. Control, cells not treated with CCL2 but treated with one of the inhibitors or siRNA. CCL2 or CCL2+inhibitor, denote cells pretreated/treated with inhibitor or siRNA oligonucleotide and exposed then to CCL2 (100 ng/ml). Data represent the value of PC after 60 min of CCL2 exposure and are the average ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001 versus CCL2 alone. C, internalization of occludin and claudin-5 during CCL2-induced brain endothelial barrier opening was also cholesterol-sensitive. Biotin-labeled occludin and claudin-5 were not internalized in the presence of the cholesterol-depleting agent MβCD (10 μm). However, replacing the cholesterol (400 μg/ml) in MβCD-treated cells reversed this effect, with resumption of CCL2-induced internalization of biotin-labeled claudin-5 and occludin. The blot represents one of five independent experiments. Graphs represent densitometric analysis of internalized biotin labeled occludin and claudin-5 during the treatment with CCL2 at the indicated times (15 and 60 min). Data represent the average ± S.D. of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.001 versus CCL2 alone.

Some caveolar ligands have been shown to be internalized in a cholesterol-dependent but caveolin-1-independent manner. We, therefore, also tested whether a cholesterol-binding agent, Filipin III, and a cholesterol-solubilizing agent, methyl-β-cyclodextrin, would affect occludin and claudin-5 internalization in the presence of CCL2 (Fig. 5, A–C). The results clearly demonstrated that treatment of endothelial cells with these agents prevented CCL2-induced internalization of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 (Fig. 5C). Using an in vitro permeability assay, we found that these agents as well application of caveolin-1siRNA prevented CCL2-induced changes in barrier permeability (Fig. 5B). Moreover, replenishing cholesterol after treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin completely restored the effect of CCL2 (increased brain endothelial barrier permeability and internalization of occludin and claudin-5 (Fig. 5C)), strongly arguing that these effects are because of specific perturbation of cholesterol and not a secondary effect of MβCD. Thus, internalization of GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 is cholesterol-sensitive and caveolin-1-dependent in brain endothelial cells. Inhibitors of clathrin-dependent endocytosis (sucrose and α-adaptin siRNA) or macropinocytosis (5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride) had no or minor effect on CCL2-induced barrier permeability (Fig. 5B).

Fate of the Internalized TJ Proteins, Occludin and Claudin- 5

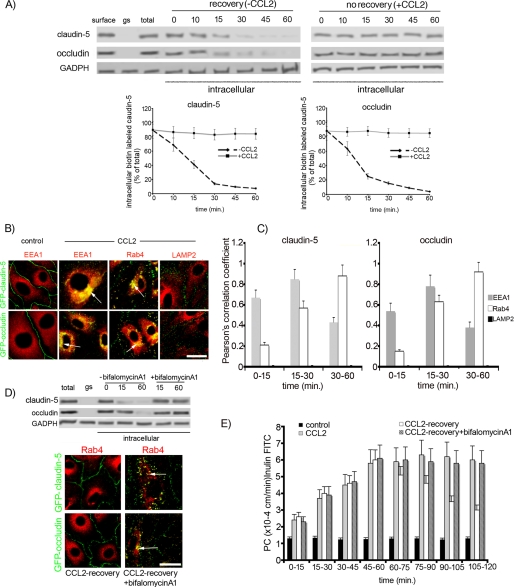

Removal of CCL2 resulted in a rapid return of occludin and claudin-5 to the cell surface. Thus, after 15 min only 25 ± 4% of occludin and 41 ± 5% of claudin-5 was found intracellularly, and by 30 min almost all of these TJ proteins were on the cell surface (Fig. 6A). This parallels a decrease in endothelial barrier permeability (Fig. 2, A and B) and suggests that recycling of occludin and claudin-5 is involved barrier recovery. To examine which part of the vesicle-vacuolar system might be involved in internalizing occludin and claudin-5, the subcellular localization of internalized GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 was analyzed in early endosomes (EEA1+), recycling endosomes (Rab4+) and lysosomes (LAMP2). At early time points (0–15 min of CCL2 treatment), GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5 were found in caveolae and, to some extent, in early endosomes (Pearson correlation coefficient, Rr, for EEA1 with GFP-claudin-5, 0.67 ± 0.07; and GFP-occludin, 0.54 ± 0.09 (Fig. 6, B and C)). After 30–60 min of exposure, GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin were mostly localized in Rab4+ endosomes (Rr = 0.88 ± 0.12 and 0.92 ± 0.11, respectively) with some in early endosomes (EEA1+) (Rr 0.43 ± 0.05 and 0.38 ± 0.042). There was no localization of these proteins in LAMP2+ vesicles (lysosomes (Fig. 6, B and C).

FIGURE 6.

A, loss of internalized-biotinylated claudin-5 and occludin after removal of CCL2 (recovery). Monolayers of mBMEC were biotinylated (biotin) and exposed to CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Remaining surface biotin was then glutathione stripped (gs), and the cells returned to fresh media without CCL2 at 37 °C. Over 0–60 min of recovery there was a reduction in the amount of intracellular biotinylated occludin and claudin-5. Recycling was absent when CCL2 was still present in the bathing media (no recovery). GADPH is an internal loading control. The graphs show quantification of internalized and recycling occludin and claudin-5 during recovery after CCL2 treatment. Data represent average ± S.D. of five independent experiments. B, monolayers of bEnd.3 cells expressing either GFP-occludin or GFP-claudin-5 were treated with CCL2 (100 ng/ml) for 15–60 min. Cells were fixed and immunocytochemistry performed. Recycling endosomes were labeled with mouse anti-Rab4 antibody; early endosomes with anti-EEA1 antibody, lysosomes with anti-LAMP2 antibody. The colocalizations of GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin with EEA1+ and Rab4+ endosomes are indicated with arrows. Scale bar, 20 μm. C, quantification of colocalization of claudin-5 and occludin with endosomal markers EEA1, Rab4, and LAMP2 during CCL2 exposure (0–60 min). The high degree of correlation between total claudin-5 and EEA1 or Rab4 as well as occludin and EEA1 or Rab4 was time-dependent. The colocalization was evaluated by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient (Rr). Error bars indicate ± S.D. D, removal of CCL2 (recovery) for 60 min after 60-min exposure to CCL2 led to a loss of Rab4 colocalization with GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin (compare with B). In addition, the vesiculo-vacuolar system was analyzed during recovery (CCL2 removal). Arrowhead indicates continuous staining for GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5, whereas Rab4+ endosomes were empty of these proteins. Adding the inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (50 nm) prevented the emptying of Rab4+ endosomes and re-establishment of interendothelial localization for GFP-occludin and GFP-claudin-5. Bafilomycin A1 also prevented recycling of biotin-labeled occludin and claudin-5 during recovery. In the absence, but not presence, of bafilomycin A1 there was a loss of intracellular biotinylated occludin and claudin-5 during recovery after exposure to CCL2. One representative blot of five independent experiments. E, blocking recycling of occludin and claudin-5 with bafilomycin A1 prevented the reestablishment of mBMEC monolayer integrity after CCL2 removal. Cells were treated with/without CCL2 for 60 min, and then medium was replaced with medium without CCL2 (recovery). The inhibitor bafilomycin A1 was added to the cells at the beginning of recovery time. The collected media from the bottom channels were analyzed, and the permeability coefficient for inulin-FITC was calculated. Data represent average ± S.D. from five independent experiments.

To confirm that recycling of occludin and claudin-5 to the cell surface plays a critical role in recovery of brain endothelial integrity, a protein recycling inhibitor, bafilomycin A1, was applied at the beginning of the recovery time (CCL2 removal). Bafilomycin A1 completely blocked emptying of Rab4+ vesicles, so that occludin and claudin-5 remained localized in the Rab4+ vesicles (Fig. 6D). Blocking recycling also prevented recovery of brain endothelial barrier integrity (Fig. 6E). Thus, our results indicate that internalization of claudin-5 and occludin follows a recycling rather than a degradation pathway and that recycled proteins are a substrate for re-assembly of the TJ complex during barrier recovery.

DISCUSSION

Blood-brain barrier opening during inflammatory leukocyte recruitment is still a poorly understood event. Most studies have focused on the role of the endothelial apical region in mediating leukocyte-endothelial interactions (23–25). There is very limited data regarding leukocyte movement between adjacent endothelial cells and the role of interendothelial junctional complexes in this process. The objective of the present study was, therefore, to investigate the effects of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) on TJ assembly and function in brain endothelial cells. We found that: (a) alterations in brain endothelial barrier permeability are associated with the internalization of two transmembrane TJ proteins, occludin and claudin-5; (b) they were internalized via a lipid raft/caveolin-1 and cholesterol-sensitive pathway; (c) internalized occludin and claudin-5 are “stored” in early as well as recycling endosomes and are available for recycling back to the cell surface; (d) recycling of “internalized” occludin and claudin-5 plays a pivotal role in re-establishing the brain endothelial barrier integrity during recovery. These findings are discussed below.

Technical Concerns

Before discussing the findings, a potential technical concern needs to be addressed: the use of GFP-tagged occludin or claudin-5 to examine TJ protein kinetics during brain endothelial barrier opening. Two potential concerns are: (a) whether overexpression of these proteins affects barrier structure and (b) whether tagged proteins behave as native occludin and claudin-5. Several studies have shown that TJ protein overexpression does not have any specific influence on the structural and functional integrity in different barrier tissues (23, 26, 27). We also found no effect of occludin and claudin-5 overexpression on brain endothelial cell permeability properties. Using stable cell lines expressing GFP-claudin-5 and GFP-occludin, instead of transient transfection, decreases any potential transfection effect on the vesiculo-vacuolar system and endocytosis. Occludin and claudin-5 were tagged with GFP at the N-terminal to avoid disruption of physiological interactions of occludin and claudin-5 with other TJ proteins, signal molecules, and actin (22, 28–30), and these proteins were found at cell borders as with endogenous claudin-5 and occludin.

Experiments were performed in parallel on both primary brain endothelial cells and a brain endothelial cell line. We did not find any significant differences in cell response (TJ unsealing) during CCL2 exposure. In most of our presented results, we have shown both cell types except for the time-lapse experiments where the tagged proteins were a major advantage. The rationale for utilizing the brain endothelial cell line (bEnd.3) over primary brain endothelial cells was that bEnd.3 cells have a higher proliferative capacity and better transfection rate than primary cell cultures facilitating establishment of cells stably expressing tagged occludin and claudin-5.

Caveolae-dependent Internalization of Occludin and Claudin-5 as a Mechanism Unsealing the TJ Complex

Despite their complex organization, TJs can be rapidly disassembled and reorganized in response to various extracellular stimuli. TJ protein internalization is one putative mechanism for removing these proteins from cell membranes during cell migration (endothelial and epithelial cells) or during the disassembly of an epithelial barrier (14, 15, 31–33). In epithelia, inflammatory mediators such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1, induce internalization of TJ transmembrane proteins, changing adhesion between adjacent epithelial cells and causing barrier disruption (13, 15, 34). The role of TJ protein internalization in blood-brain barrier opening has, however, been uncertain. Similarities in TJ structure and function between brain endothelial cells and epithelial cells led us to test whether occludin and claudin-5 internalization is a mechanism underlying brain endothelial barrier opening. Recent findings from our and other laboratories clearly indicate that increased brain endothelial barrier paracellular permeability is associated with redistribution of TJ proteins (7, 16, 35–37). Besides redistribution, most TJ proteins undergo phosphorylation or dephosphorylation, and many studies pinpoint this as a critical process in changing adhesive interactions in the TJ complex (6–8, 37). Although we do not exclude TJ protein phosphorylation as a critical component in altering adhesive interactions between the endothelial cells, some morphological (loss of continuous staining for TJ proteins at cell borders) and biochemical (redistribution from membrane to cytosolic and actin cytoskeletal fractions) evidence indicates that transmembrane TJ proteins are removed from the plasma membrane. Results in this study indicate that transmembrane TJ protein internalization is an underlying mechanism for these morphological and biochemical changes during TJ complex unsealing as well as determining the mechanisms involved in internalization of occludin and claudin-5.

There is strong evidence that occludin and claudin-5 are localized in lipid rafts/caveolae. It has been suggested that such localization is probably critical for TJ complex stability (38–41). Thus, it is not surprising that our membrane traffic analysis pointed out that caveolae/lipid raft-dependent internalization is an important mechanism for removing occludin and claudin-5 from brain endothelial borders during opening of the paracellular route.

Lipid rafts/caveolae are cholesterol-sphingolipid-rich membrane microdomains (42). Many studies have revealed that the depletion of cholesterol from the plasma membrane with agents such as filipin III, nistatin, or MβCD causes disruption of these structures and inhibits their functions without altering clathrin-mediated endocytosis (43, 44). Thus, caveolae/lipid raft- and clathrin-dependent endocytosis can be distinguished by means of cholesterol sensitivity. Taking the above issues into consideration, our finding, that depletion of membrane cholesterol using either filipin III or MβCD inhibited CCL2-induced increases in brain endothelial barrier permeability and internalization of occludin and claudin-5, strongly suggests an important role for caveolae/lipid rafts in these processes. The observed inhibitory effects of MβCD could be reversed by cholesterol reconstitution.

This study also found that internalization of occludin and claudin-5 requires caveolin-1 (results using siRNA knockdown of caveolin-1). Caveolin-1 is another major constituent of caveolae. Caveolin-1 is thought responsible for the invaginated flask-shaped morphology of caveolae through association with select raft domains (45). However, caveolin-1 is also one of the key regulators of caveolae/raft endocytosis. Together with the cholesterol results, these findings strongly support the concept that CCL2-induced internalization of occludin and claudin-5 is almost entirely mediated by caveolae/lipid rafts and dependent on caveolin-1.

Our findings are in concordance with the previously reported findings for epithelial cells treated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, lymphotoxin-like inducible protein-LIGHT, INF-γ, and TNF-α (46, 47). On the other hand, there is recent evidence that junctional molecules, Ve-cadheins and β-catenin, could be internalized by the clathrin-dependent pathway during the opening of the paracellular route induced by vascular epidermal growth factor (8, 48, 49). Apparently, the type of internalization of junctional molecules during the forming of paracellular route greatly depends on cell type, type of stimuli, as well as the localization of junctional molecules on the specific membrane microdomains.

Another possibility is that, under certain conditions, there may be cross-talk between different internalization pathways and involvement of one or more endocytotic pathway (i.e. caveolin and clathrin internalization). Because sorting of internalized proteins was via EEA1 vesicles, it is necessary to note that “classic” caveolae-dependent internalization does not perfectly fit the process described in this study (42). Further investigation is needed to define this pathway as well as the degree of cell and stimulus specificity.

Finally, it is important to address the controversy over the role of caveolin-1 in regulating vascular permeability. There are studies showing that inhibiting caveolae formation by knocking down caveolin-1 with siRNA or gene deletion can increase vascular permeability rather than, as in our study, acting as a stabilization factor (50–52). A possible explanation for these discrepancies could be that the absence of caveolin-1, a major component of caveolae, may shift internalization to another pathway (e.g. clathrin-dependent) (53). There is also the possibility that other caveolin proteins (caveolin-2 or -3) can be expressed as a “compensatory mechanism,” even in cells that do not normally have significant levels of these proteins (54, 55). Persistent vascular hyperpermeability, even in basal conditions, in caveolin KO mice could be the aftermath of a lack of caveolin-1 signaling during the biogenesis of TJ complexes. Such signaling has been shown to play a pivotal role by several studies (56, 57). Thus, caveolin-1 and caveolae-dependent endocytosis plays a pivotal role in biogenesis and dynamic changes in the TJ complex. Stimulus type, exposure duration, cell type, and the specific microenvironment are potential factors determining the role of caveolin-1 in TJ regulation, and this needs further investigation.

Fate of Internalized Endothelial TJ Proteins, Occludin and Claudin-5

The current study examined whether internalized occludin and claudin-5 are degraded or recycled back to the cell surface. Recycling of internalized TJ proteins has been shown in dynamic situations where contacts between epithelial or endothelial cells must be rapidly broken and remade (12, 34, 58). In contrast, some recent studies have shown that down-regulation of cell-cell adhesion and/or permanent disturbance of junctional complexes is associated with TJ protein degradation (6, 36, 59). Our findings on the localization and timing of TJ protein internalization in CCL2-treated brain endothelial cells and recovery experiments clearly indicate that occludin and claudin-5 undergo recycling. We have found no evidence that internalized TJ proteins undergo degradation or that any mechanism other than recycling contributes to TJ complex recovery. Considering the role of CCL2 during inflammation, the effects of this chemokine on TJ protein endocytosis could play a pivotal role in supporting leukocyte entry into brain by allowing paracellular route formation. Recycling of TJ proteins back to the plasma membrane would allow resealing after leukocyte entry.

Finally, we would like to address the issue of whether brain endothelial and epithelial cells show similar mechanisms of paracellular route opening. Although both cell types express claudins, the type of expression, e.g. claudin-5 versus claudin 1, 2, and 4 (1–3) and their response to stimuli can differ. Brain endothelial cells and epithelial cells show differences in response to inflammatory mediators. For example, there are temporal and spatial differences in the Ca2+ response to TNF-α, INF-γ, and interleukin-8 (60–64). Endothelial and epithelial cells can also utilize different endocytotic pathways to internalize the same receptors under the same stimuli (i.e. integrin internalization (65, 66)). Thus, it is dangerous to assume by analogy that endothelial and epithelial cells undergo similar processes.

In summary, as a possible scenario for opening and closing of the paracellular route of brain endothelial cells, we suggest that the adhesion property of the TJ complex is normally maintained by homotypical cell-cell interactions of occludin and claudin-5. This is probably disturbed by phosphorylation of these proteins and their ultimate internalization via a caveolae-dependent pathway. The internalized proteins become sorted into recycling endosomes until a new signal causes their return to the cell membrane to re-establish junctional interactions.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant (AVA) NS 044907. This work was also supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research Faculty Grants and Awards Program, University of Michigan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- TJ

- tight junction

- EEA1

- early endosomal antigen-1

- LAMP2

- lysosomal-associated membrane protein

- CCL2

- CC ligand 2

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- CT

- cholera toxin

- TR

- transferring

- LC

- lactacystein

- INF-γ

- interferon-γ

- TNF-α

- tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-8

- interleukin-8

- ZO-1

- zonula occludens-1

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MES

- 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- ECIS

- electrical cell impedance sensor

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- siRNA

- small interference RNA

- FITC

- fluorescein isothiocyanate

- TEER

- transendothelial electrical resistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garcia J. G., Schaphorst K. L. (1995) J. Invest. Med. 43, 117–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harhaj N. S., Antonetti D. A. (2004) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 1206–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazzoni G. (2006) Thromb. Haemost. 95, 36–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farshori P., Kachar B. (1999) J. Membr. Biol. 170, 147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaio L., Rouhanizadeh M., Reddy S., Sevanian A., Hwang J., Hsiai T. K. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290, H674–H683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haorah J., Ramirez S. H., Schall K., Smith D., Pandya R., Persidsky Y. (2007) J. Neurochem. 101, 566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stamatovic S. M., Dimitrijevic O. B., Keep R. F., Andjelkovic A. V. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8379–8388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hommelgaard A. M., Roepstorff K., Vilhardt F., Torgersen M. L., Sandvig K. (2005) van Deurs, B. Traffic. 6, 720–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukamato T., Nigam S. K. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 276, F737–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanov A. I., McCall I. C., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A. (2004a) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2639–2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkham M., Parton R. G. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1745, 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee S., Ghosh R. N., Maxfield F. R. (1997) Physiol. Rev. 77, 759–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruewer M., Utech M., Ivanov A. I., Hopkins A. M., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A. (2005) FASEB J. 19, 923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Utech M., Ivanov A. I., Samarin S. N., Bruewer M., Turner J. R., Mrsny R. J., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5040–5052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda M., Kubo A., Furuse M., Tsukita S. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 1247–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivanov A. I., Nusrat A., Parkos C. A. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 176–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatovic S. M., Keep R. F., Kunkel S. L., Andjelkovic A. V. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 4615–4628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martineau M., Galli T., Baux G., Mothet J. P. (2008) Glia 56, 1271–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zinchuk V., Zinchuk O., Okada T. (2007) Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 40, 101–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartmann C., Zozulya A., Wegener J., Galla H. J. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 1318–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abedinpour P., Jergil B. (2003) Anal. Biochem. 313, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bamforth S. D., Kniesel U., Wolburg H., Engelhardt B., Risau W. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 1879–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medina R., Rahner C., Mitic L. L., Anderson J. M., Van Itallie C. M. (2000) J. Membr. Biol. 178, 235–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diacovo T. G., Roth S. J., Buccola J. M., Bainton D. F., Springer T. A. (1996) Blood. 88, 146–157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I., Nourshargh S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amasheh S., Meiri N., Gitter A. H., Schöneberg T., Mankertz J., Schulzke J. D., Fromm M. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 4969–4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Itallie C., Rahner C., Anderson J. M. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 107, 1319–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blasig I. E., Winkler L., Lassowski B., Mueller S. L., Zuleger N., Krause E., Krause G., Gast K., Kolbe M., Piontek J. (2006) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63, 505–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanning A. S., Little B. P., Rahner C., Utepbergenov D., Walther Z., Anderson J. M. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 721–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rüffer C., Gerke V. (2004) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palacios F., Schweitzer J. K., Boshans R. L., D'Souza-Schorey C. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 929–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paterson A. D., Parton R. G., Ferguson C., Stow J. L., Yap A. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21050–21057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen L., Turner J. R. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3919–3936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hopkins A. M., Walsh S. V., Verkade P., Boquet P., Nusrat A. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 725–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H. S., Namkoong K., Kim D. H., Kim K. J., Cheong Y. H., Kim S. S., Lee W. B., Kim K. Y. (2004) Microvasc. Res. 68, 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schreibelt G., Kooij G., Reijerkerk A., van Doorn R., Gringhuis S. I., van der Pol S., Weksler B. B., Romero I. A., Couraud P. O., Piontek J., Blasig I. E., Dijkstra C. D., Ronken E., de Vries H. E. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 3666–3676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persidsky Y., Heilman D., Haorah J., Zelivyanskaya M., Persidsky R., Weber G. A., Shimokawa H., Kaibuchi K., Ikezu T. (2006) Blood, 107, 4770–4780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto M., Ramirez S. H., Sato S., Kiyota T., Cerny R. L., Kaibuchi K., Persidsky Y., Ikezu T. (2008) Am. J. Pathol. 172, 521–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank P. G., Woodman S. E., Park D. S., Lisanti M. P. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 1161–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nag S., Venugopalan R., Stewart D. J. (2007) Acta Neuropathol. 114, 459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nusrat A., Parkos C. A., Verkade P., Foley C. S., Liang T. W., Innis-Whitehouse W., Eastburn K. K., Madara J. L. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 1771–1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nabi I. R., Le P. U. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 673–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambert D., O'Neill C. A., Padfield P. J. (2007) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 20, 495–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J., Chen L., Wang G., Tang H. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 2005–2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nichols B. (2003) J. Cell Sci. 116, 4707–4714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poritz L. S., Garver K. I., Tilberg A. F., Koltun W. A. (2004) J. Surg. Res. 116, 14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwarz B. T., Wang F., Shen L., Clayburgh D. R., Su L., Wang Y., Fu Y. X., Turner J. R. (2007) Gastroenterology 132, 2383–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavard J., Gutkind J. S. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1223–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao K., Garner J., Buckley K. M., Vincent P. A., Chiasson C. M., Dejana E., Faundez V., Kowalczyk A. P. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5141–5151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jasmin J. F., Malhotra S., Singh Dhallu M., Mercier I., Rosenbaum D. M., Lisanti M. P. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 721–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin M. I., Yu J., Murata T., Sessa W. C. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 2849–2856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song L., Ge S., Pachter J. S. (2007) Blood 109, 1515–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Alessio A., Al-Lamki R. S., Bradley J. R., Pober J. S. (2005) Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1273–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shakirova Y., Bonnevier J., Albinsson S., Adner M., Rippe B., Broman J., Arner A., Swärd K. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C1326–C1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park D. S., Woodman S. E., Schubert W., Cohen A. W., Frank P. G., Chandra M., Shirani J., Razani B., Tang B., Jelicks L. A., Factor S. M., Weiss L. M., Tanowitz H. B., Lisanti M. P. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160, 2207–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu J., Bergaya S., Murata T., Alp I. F., Bauer M. P., Lin M. I., Drab M., Kurzchalia T. V., Stan R. V., Sessa W. C. (2006) J. Clin. Invest. 116, 1284–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murata T., Lin M. I., Huang Y., Yu J., Bauer P. M., Giordano F. J., Sessa W. C. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 2373–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Terai T., Nishimura N., Kanda I., Yasui N., Sasaki T. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2465–2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L. B., Xue Y. X., Liu Y. H., Wang Y. B. (2008) J. Neurosci. Res. 86, 1153–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deli M. A., Abrahám C. S., Kataoka Y., Niwa M. (2005) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 25, 59–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miakotina O. L., Snyder J. M. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 283, L418–L427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mul F. P., Zuurbier A. E., Janssen H., Calafat J., van Wetering S., Hiemstra P. S., Roos D., Hordijk P. L. (2000) J. Leukoc. Biol. 68, 529–537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakajima S., Look D. C., Roswit W. T., Bragdon M. J., Holtzman M. J. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 267, L422–L432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilhelm I., Farkas A. E., Nagyoszi P., Váró G., Bálint Z., Végh G. A., Couraud P. O., Romero I. A., Weksler B., Krizbai I. A. (2007) Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 6261–6274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Echarri A., Muriel O., Del Pozo M. A. (2007) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 627–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panicker A. K., Buhusi M., Erickson A., Maness P. F. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312, 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.