Abstract

1,4-Dihydropyridines (DHPs) constitute a major class of ligands for L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCC). The DHPs have a boat-like, six-membered ring with an NH group at the stern, an aromatic moiety at the bow, and substituents at the port and starboard sides. Various DHPs exhibit antagonistic or agonistic activities, which were previously explained as stabilization or destabilization, respectively, of the closed activation gate by the portside substituents. Here we report a novel structural model in which agonist and antagonist activities are determined by different parts of the DHP molecule and have different mechanisms. In our model, which is based on Monte Carlo minimizations of DHP-LTCC complexes, the DHP moieties at the stern, bow, and starboard form H-bonds with side chains of the key DHP-sensing residues Tyr_IIIS6, Tyr_IVS6, and Gln_IIIS5, respectively. We propose that these H-bonds, which are common for agonists and antagonists, stabilize the LTCC conformation with the open activation gate. This explains why both agonists and antagonists increase probability of the long lasting channel openings and why even partial disruption of the contacts eliminates the agonistic action. In our model, the portside approaches the selectivity filter. Hydrophobic portside of antagonists may induce long lasting channel closings by destabilizing Ca2+ binding to the selectivity filter glutamates. Agonists have either hydrophilic substituents or a hydrogen atom at their portside, and thus lack this destabilizing effect. The predicted orientation of the DHP core allows accommodation of long substituents in the domain interface or in the inner pore. Our model may be useful for developing novel clinically relevant LTCC blockers.

1,4-Dihydropyridines (DHPs)2 form a major class of L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) ligands. DHPs can operate as agonists or antagonists depending on their chemical structure. Importantly, activity of some DHP derivatives may shift from agonism to antagonism (and vice versa) upon site-specific mutation of the channel or modified experimental conditions (for reviews, see Refs. 1 and 2). It has been the dual nature of DHP activity (agonism and antagonism), which has made it challenging for interpretation in structural terms. The other major classes of LTCC ligands, the phenylalkylamines and benzothiazepines, are strictly antagonists.

Despite a number of studies, the molecular mechanism for the activity of DHPs on LTCC remains unclear. In the present work we have addressed this problem by combining a molecular modeling approach with analyses of relevant published data. We employed a method of multiple Monte Carlo energy minimizations for docking various DHPs in our earlier reported homology model of LTCC (3), which is based on the crystal structure of the KvAP K+ channel (4). We constrained our analyses to potential ligand-binding modes that would be consistent with the features of the ligand-channel activity relationship described in published experiments. These include the structure-activity relationship of the many derivatives of DHPs and the results of mutational analyses of the DHP binding site. These experiments were mostly patch clamp electrophysiology and in vitro binding studies with LTCC heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes or human cell lines.

The biophysical features of Ca2+ channels are important for understanding the action of DHPs. Ca2+ channels operate in three gating modes: (i) an inactivated mode from which channels do not open upon depolarization, (ii) a depolarization-elicited mode with multiple short openings, and (iii) a naturally occurring, but usually infrequent, long openings mode. Hess and coauthors (5) reported that DHP agonists stabilized long openings, whereas DHP antagonists promoted inactivated modes. In many respects, the separation of DHP agonists and antagonists is not so clear. DHP antagonists can exhibit agonist-like features, by increasing the percentage of available channels in the long opening mode (5). DHPs can also act as either agonists or antagonists under different experimental conditions (6–8). The effect of DHPs is Ca2+-dependent. It has been proposed that DHP antagonists bind to and stabilize a non-conducting channel state in which the selectivity filter is occupied by a single Ca2+ ion. Binding of a second Ca2+ ion is considered to destabilize DHP binding (9–11).

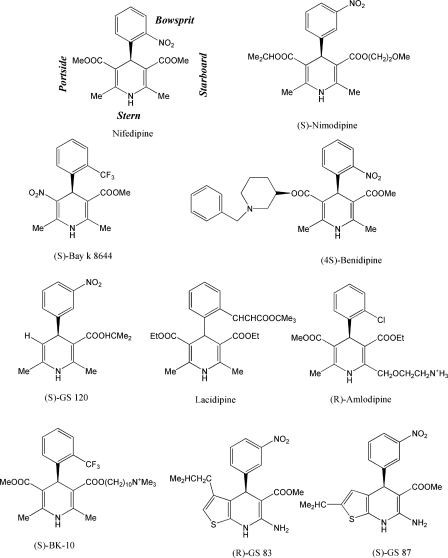

The structure of DHPs can be described as a flattened-boat six-membered ring with the NH group at the stern, an aromatic moiety at the bow, and various substituents at the port and starboard sides (Fig. 1). Experimental data reveals that the agonistic or antagonistic action is primarily determined by the nature of the portside group in the ortho position of the DHP ring relative to the bowsprit. Hydrophobic groups such as COOMe promote an antagonistic effect, whereas hydrophilic groups like NO2 promote an agonistic effect (12). Intriguingly, enantiomers of some DHPs, e.g. (R)- and (S)-Bay k 8644 demonstrate opposite, antagonistic and agonistic effects on LTCC (13, 14).

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structures of DHPs. Some compounds are named with the prefix GS that stands for Goldmann and Stoltefuss, the authors of a fundamental review on structure-activity of DHPs (12), and the compound number as it appears in the review. Abbreviation BK-10 includes initials of the first and last authors of Ref. 18, and the length of an oligomethylene linker between the DHP core and trimethylammonium group.

The access of DHPs to LTCCs has been studied by several groups (15–17) and the consensus is that DHPs reach their binding site within the pore-forming α1-subunit from the extracellular side. A series of DHP derivatives with a permanently charged ammonium group was used to estimate the distance of the DHP binding site from the extracellular surface of the membrane (18). The optimal potency was found with an ammonium group linked to the dihydropyridine ring via a decamethylene chain.

The DHP binding site has been outlined to the interface between repeats III and IV of the pore-forming α1-subunit of LTCC using antibody mapping of proteolytically labeled channel fragments and a series of subsequent studies with chimeras and site-specific mutations (19–29). Key DHP-sensing residues were defined in transmembrane segments IIIS5, IIIS6, and IVS6 and in the pore helix IIIP. Using the x-ray structure of K+ channels as a guide, the corresponding DHP residues appear tightly spaced at the interface of the III/IV domain in the expected three-dimensional structure of LTCC.

The available experimental data are insufficient to elaborate structural models of DHP-LTCC complexes. An experimental structure of such a complex would be of great importance, but x-ray structures of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are unavailable. Crystallographic studies of DHP-LTCC complexes are even more challenging. Indeed, many small-molecule ligands of K+ channels are known, but only a few ligands have so far been co-crystallized with KcsA. In these circumstances, molecular modeling remains the only feasible approach to provide insights into atomic details of ligand-channel interactions such as positions and orientations of DHP ligands and determinants for their agonistic and antagonistic actions. Predictions from a modeling study remain hypothetical until they are experimentally confirmed, but hypotheses that explain numerous experimental observations stimulate further experimental studies.

To date three models of DHP-bound LTCC have been published (30–32). Despite differences in the proposed location of ligands and patterns of the ligand-receptor interactions, all three models suggest a similar molecular mechanism for DHP action. The portside group in these models is oriented toward the ring of hydrophobic residues in the C-terminal halves of S6 helices, close to the proposed activation gate in LTCC. Hydrophobic groups at the portside of the DHP antagonists are proposed to stabilize the closed state of the activation gate, whereas hydrophilic groups of agonists are considered to destabilize the closed state (or stabilize the open state). A primary weakness of these models is that agonistic and antagonistic activities of DHPs are considered to be caused by opposite (stabilizing and destabilizing) effects on the same molecular target (near the activation gate). This “single target” model does not adequately account for the wide variety of observed behaviors of DHP derivatives in published experiments.

We have elaborated an alternative model in our present work that suggests different molecular targets and different mechanisms for agonistic and antagonistic activities of DHPs. As published experiments have revealed, the agonistic or antagonistic activity of a DHP ligand not only depends on its chemical structure, but also is sensitive to the experimental conditions and the structure of the drug target. Small changes to the structure of LTCC (as revealed by the behaviors of DHPs in chimeric and mutagenized LTCC) can shift a DHP agonist into an antagonist. The model that explains these behaviors is one where atomic determinants for both agonist and antagonist capacities are present within a single DHP molecule. Manifestation of these capacities depends on structural peculiarities of the DHP ligand and the DHP receptor, as well as on the ligand-receptor orientation that can be sensitive to experimental conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study we used our recent model of the LTCC channel (3) that contains transmembrane segments S5 and S6 and P-loops from the four repeats. Extracellular linkers, voltage-sensing domains, and other segments, which are far from the DHP binding site, were not included in the model. Among available x-ray structures that could serve as templates for modeling the open state CaV1.2, we have chosen KvAP (4) because both channels are voltage-gated and S6 segments in both channels lack a PVP motif that affects the pore geometry. The closed state of CaV1.2 was modeled using the KcsA structure (33) as a template. The selectivity filter region was built using the NaV1.4 P-loop domain model (34) as a template.

We designate residues using labels, which are universal for P-loop channels (Table 1). A residue label includes the domain (repeat) number (1 to 4), segment type (p, P-loop; i, the inner helix; o, the outer helix), and relative number of the residue in the segment.

TABLE 1.

Sequence alignment and DHP-sensing residues

Experimentally found DHP-sensing residues (1, 2) are in bold type. Major contributors to the ligand-receptor energy in our models are underlined.

| Channel | Segment | Residue label prefix | Sequence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 11 | 21 | |||

| KcsA | M1 | o | HWRAAGAA | TVLLVIVLLA | GSYLAVLAE |

| KvAP | S5 | o | DKIRFYHL | FGAVMLTVLY | GAFAIYIVE |

| Kv1.2 | S5 | o | SMRELGLL | IFFLFIGVIL | FSSAVYFAE |

| Cav1.2 | IS5 | 1o | AMVPLLHI | ALLVLFVIII | YAIIGLELF |

| IIS5 | 2o | SLRSIASL | LLLLFLFIII | FSLLGMQLF | |

| IIIS5 | 3o | AIRTIGNI | VIVTTLLQFM | FACIGVQLF | |

| IVS5 | 4o | SFQALPYV | ALLIVMLFFI | YAVIGMQVF | |

| 33 | 41 | 51 | |||

| KcsA | P | p | LITYPRAL | WWSVETATTV | GYGDL |

| KvAP | P | p | IKSVFDAL | WWAVVTATTV | GYGDV |

| Kv1.2 | P | p | FPSIPDAF | WWAVVSMTTV | GYGDM |

| Cav1.2 | IP | 1p | FDNILFAM | LTVFQCITME | GWTDV |

| IIP | 2p | FDNFPQSL | LTVFQILTGE | DWNSV | |

| IIIP | 3p | FDNVLAAM | MALFTVSTFE | GWPEL | |

| IVP | 4p | FQTFPQAV | LLLFRCATGE | AWQDI | |

| 2 | 11 | 21 | |||

| KcsA | M2 | i | WGRLVAVVV | MVAGITSFGL | VTAALATWFV |

| KvAP | S6 | i | IGKVIGIAV | MLTGISALTL | LIGTVSNMFQ |

| Kv1.2 | S6 | i | GGKIVGSLC | AIAGVLTIAL | PVPVIVSNFN |

| Cav1.2 | IS6 | 1i | LPWVYFVSL | VIFGSFFVLN | LVLGVLSGEF |

| IIS6 | 2i | LVCIYFIIL | FISPNYILLN | LFLAIAVDNL | |

| IIIS6 | 3i | EISIFFIIY | IIIIAFFMMN | IFVGFVIVTF | |

| IVS6 | 4i | FAVFYFISF | YMLCAFLIIN | LFVAVIMDNF | |

The energy expression included van der Waals, electrostatic, H-bonding, hydration, and torsion components, as well as the energy of deformation of bond angles in DHPs. The bond angles of the protein were kept rigid. The hydration energy was calculated by the implicit solvent method (35). Nonbonded interactions were calculated using the AMBER force field version (36, 37), which is consistent with the implicit solvent approach. All ionizable residues were modeled in their neutral forms except for the selectivity filter glutamates in position p50 of P-loops. Nonbonded interactions were truncated at distances >8 Å. This cutoff speeds up calculations without noticeably decreasing the precision of energy calculations (38). The cutoff was not applied to electrostatic interactions involving Ca2+ ions and ionized groups; these interactions were computed at all distances. The energy was minimized in the space of generalized coordinates, which include all torsion angles, bond angles of the ligand, positions of ions, and positions and orientations of root atoms of ligands. The channel models and their complexes with ligands were optimized by the Monte Carlo minimization (MCM) method (39). An MCM trajectory was terminated when 1,000 consecutive energy minimizations did not decrease the energy of the apparent global minimum.

To ensure similar backbone geometry with the x-ray template, Cα atoms of the model were pinned. A pin is a flat-bottom energy function that allows penalty-free deviations of an atom from the position of the homologous atom in the template within a specified distance (1 Å in this study). Larger deviations are penalized by a parabolic energy function with the force constant of 10 kcal mol−1 Å−2. The proposed specific interactions between ligands and DHP-sensing residues were imposed by distance constraints. Thus, DHP-LTCC H-bonds were imposed with distance constraints that allow penalty-free separation of the H-bonding atoms up to 2.2 Å. The complexes MC minimized with the distance constraints were refined in unconstrained MCM trajectories to ensure that the proposed models are energetically stable. All calculations were performed with the ZMM program.

RESULTS

Dual Nature of DHP Agonism and Antagonism

DHP agonists lack the relevance to cardiovascular medicine, but have been useful along with the other DHP derivatives as tools to explore the pore and gating behavior of LTCCs. Agonists such as (S)-Bay k 8644 bear an NO2 group at the portside (Fig. 1). Other agonists also have a small hydrophilic substituent at the portside such as nitrile, lactone, and thiolacton moieties. In published models (30–32), agonist DHPs are hypothesized to destabilize the closed state by means of their hydrophilic substituent, whereas the presence of a hydrophobic instead of hydrophilic portside group is expected to cause the opposite effect on the same gating machinery and thus to stabilize the closed state. Examples of hydrophobic portside groups include (R)-Bay k 8644 and other antagonists such as nifedipine. The proposition that the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of the portside group provides an agonist or antagonist character for DHPs does not hold when agonists such as (S)-GS 120 (Fig. 1) are considered, which lack a portside substituent (12).

Surprisingly, both antagonists and agonists stabilize the long lasting channel openings regardless of the chemical nature of the portside group (5). This similarity between agonist and antagonist effects on channel gating supports the concept that agonists and antagonists share a core structural constituent that does not involve portside groups. The commonality of gating effects opens the possible interpretation that DHP agonists and antagonist might not be operating as opposing agents on the same target within LTCC. Furthermore, the vulnerability of DHPs switching from agonists to antagonists to small changes of the channel structure and changing environmental conditions may indicate that the difference between a DHP acting as an agonist and antagonist is likely a matter of degree to which different agonist and antagonist determinants in the same DHP molecule prevail.

Direct Interaction of DHPs with Ca2+ Ions

The selectivity filter of LTCC includes four conserved glutamates, E1p50, E2p50, E3p50, and E4p50, which are provided by domains I, II, III, and IV, respectively (EEEE locus, Table 1). It was clearly demonstrated that the antagonistic action of DHPs is directly associated with the Ca2+ occupancy of the selectivity filter. In elegant work presented by Peterson and Catterall (11) DHP antagonists were found to stabilize the impermeable Ca2+-deficient state of the selectivity filter with only one Ca2+ ion bound to it. Peterson and Catterall (11) suggest that DHP binding is allosterically coupled to binding of the Ca2+ ion to the selectivity filter (11). Although allosteric coupling is not a possibility that can be ruled out, we aim to explore another possible interpretation in this study. Preliminary considerations for potential binding orientations of DHPs in our recently described model of drug binding to LTCC (3) allows us to suggest, as an initial hypothesis, that the hydrophobic portside group of antagonists can impose a blocking effect by approaching the EEEE locus and preventing a second Ca2+ ion from occupying the pore. Absence of a portside substituent or nucleophilic one in the ortho position to the bowsprit would not prevent two Ca2+ ions occupying in the selectivity filter and thereby depriving these DHP ligands the property of antagonism. In the rest of this study we elaborate and test molecular models based on this hypothesis. We focus on energetically favorable DHP binding modes, in which the portside group approaches the selectivity filter and can directly interact with Ca2+ ions bound to the selectivity filter glutamates.

Key Ligand-sensing Residues

Potent DHP ligands have H-bond acceptors at the portside, starboard, and bowsprit, and an H-bond donor at the stern. Removal of the portside ester group in the fused rings (Fig. 1) does not abolish the channel-blocking potency of DHP ligands (for review, see Ref. 12). Therefore, portside ester groups are unlikely to strongly interact with the DHP receptor. The remaining three H-bonding groups should bind to the DHP receptor, whereas we assume that the portside group should be exposed toward the selectivity filter, according to our hypothesis. Importantly, the three H-bonding groups and the portside substituent lie approximately in a plane that passes through the DHP ring.

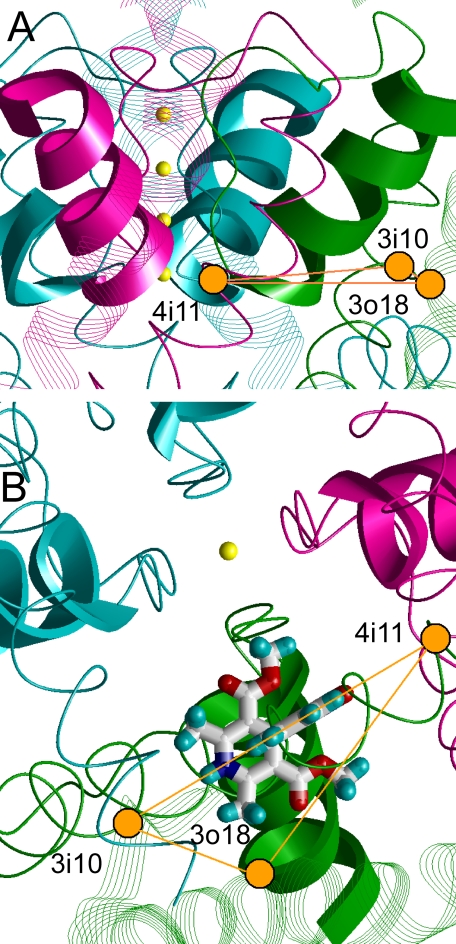

To elaborate the binding mode of DHPs, we highlighted α-carbons in the three-dimensional structure of KvAP (4), which correspond to matching positions with polar DHP-sensing residues in a homology model of LTCC. We focused on key DHP-sensing residues known from experimental data (Table 1), namely, Q3o18, Y3i10, and Y4i11 whose long side chains can donate and accept H-bonds. Corresponding residues in KvAP are Vo18 and Vi10 in one subunit and Mi11 in the neighboring subunit (Table 1). These three α-carbons (Vo18, Vi10, and Mi11) form a plane, which also accommodates a K+ ion in position 4 of the selectivity filter (Fig. 2A) in KvAP as well as the resolved x-ray structures of other K+ channels. In the corresponding triangle of LTCC, a DHP antagonist (e.g. nifedipine) can be oriented in several ways to direct its H-bonding moieties toward the H-bonding residues of the channel. Following the initial hypothesis we further selected an orientation in which portside of nifedipine would approach the selectivity filter. The ligand fits within the triangle in the KvAP template and faces position 3i10 by the stern, position 4i11 by the bowsprit, and position 3i18 by the starboard (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

The KvAP structure with highlighted positions of three residues whose matches in the homology model of LTCC can make H-bonds with DHPs. The outer helices and pore helices are shown as solid and six-stranded ribbons, respectively. The inner helices, ascending limbs around the selectivity filter, and extracellular linkers between the ascending limbs and the pore helices are shown as single-stranded backbones. The K+ channel subunits that correspond to the Ca2+ channel repeats III and IV are colored green and purple, respectively. K+ ions in the selectivity filter are shown as small yellows spheres. α-Carbons of Vo18 and Vi10 in a green-colored subunit and Mi11 in the purple-colored subunit are shown as orange circles. The LTCC has DHP H-bonding residues Y3i10, Y4i11, and Q3o18 in the matching positions (Table 1). A, side view with the front subunit removed for clarity. Note that the K+ ion in position 4 of the selectivity filter lies approximately in the plane specified by α-carbons of Vo18, Vi10, and Mi11. B, intracellular view with the proposed orientation of a DHP ligand, nifedipine relative to the three α-carbons. The hydrophobic portside of nifedipine faces the K+ ion in position 4. With the same orientation in the homology model of LTCC, nifedipine faces Y3i10 by the stern, Y4i11 by the bowsprit, and Q3o18 by the starboard.

Docking of Nimodipine in LTCC

To test whether the proposed binding scheme is energetically possible, we docked (S)-nimodipine, a DHP derivative, which appears to be significantly more potent than its enantiomer (R)-nimodipine (40, 41), in our KvAP-based model of the LTCC (3). In this model a Ca2+ ion is chelated by the selectivity filter glutamates from repeats I and II (E1p50 and E2p50) and the second Ca2+ ion, which is more proximal to the inner pore than the first ion, is chelated by the selectivity filter glutamates E3p50 and E4p50 from repeats III and IV, respectively. (We designate models with two Ca2+ ions as Ca2+-saturated to discriminate them from Ca2+-deficient models in which the selectivity filter region is loaded with a single Ca2+ ion.) When the portside of (S)-nimodipine is directed toward the pore lumen, two orientations are possible in which the ligand can form three H-bonds with the triad Y3i10, Y4i11, and Q3o18. In one orientation the stern and bowsprit would interact with Y3i10 and Y4i11, respectively (named the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation), as illustrated in Fig. 2B. In the opposite orientation, the stern would interact with Y4i11 and the bowsprit with Y3i10 (named the stern-to-Y4i11 orientation). In both orientations, the starboard can interact with Q3o18 because both trans- and cis-orientations of the ester group are energetically possible. We computationally tested both orientations. The proposed DHP-LTCC interactions were imposed by distance constraints between corresponding atoms. The multi-MCM method was used to find energetically optimal ligand-channel complexes from hundreds of randomized starting orientations of (S)-nimodipine. Resulting ensembles of low-energy structures were analyzed and the main contributors to the ligand-channel interactions are highlighted in Table 1. It is evident from Table 1 that the modeling prediction of DHP-sensing residues (14 bold type underlined residues) agrees well with the experimentally derived data (18 bold type residues).

MC minimizations of starting structures with stern-to-Y3i10 and stern-to-Y4i11 orientations yielded complexes with similar ligand-receptor energies and similar patterns of ligand-sensing residues. Use of energetic criteria alone does not provide a means to separate the optimal orientations of nimodipine in the pore (stern-to-Y3i10 or stern-to-Y4i11). We provide three arguments in favor of the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation.

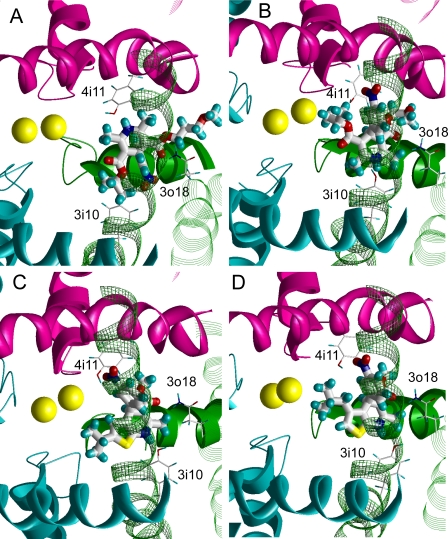

1) In the stern-to-Y4i11 orientation (Fig. 3A), the portside methyl group in the ortho position to the NH group faces the Ca2+ ion chelated by E3p50 and E4p50, whereas the portside carboxyisopropyl group is up against the channel wall. The stern-to-Y3i10 orientation (Fig. 3B) provides a more likely structure that would destabilize Ca2+ binding to the selectivity filter glutamates as expected for an antagonist. In this configuration, the hydrophobic portside group protrudes in the pore lumen and approaches the Ca2+ ion chelated by E3p50 and E4p50.

FIGURE 3.

Choosing orientation of DHP ligands in the homology model of LTCC. S6, P, and S5 helices are shown, respectively, as by smooth ribbons, sharp ribbons, and strands. Repeat III is green, repeat IV is purple, and repeats I and II are cyan. Ca2+ ions are shown as yellow spheres. DHP-sensing residues are shown by thin sticks and ligands by thick sticks. A and B, cytoplasmic views with (S)-nimodipine in alternative orientations. A, the stern of nimodipine interacts with Y4i11. The portside group does not approach the Ca2+ ion chelated by the selectivity filter glutamates in repeats III and IV. B, in the opposite orientation, the stern interacts with Y3i10, whereas the hydrophobic substituent at the portside approaches the Ca2+ ion. C and D, stern-to-Y3i10 orientation of DHPs that lack a portside ester group. The portside of an inactive compound GS 87 projects toward the interface between repeats II and III (C), whereas the portside of an active compound GS 83 approaches the Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter (D).

2) The stern-to-Y3i10 orientation can more adequately describe the structure-activity relationships of DHPs, GS 83, and GS 87 (12), in which the five-membered ring is fused with the DHP ring (Fig. 1). (R)-GS 83, in which the five-membered ring is at the portside, is a more active antagonist than (S)-GS 83. In our model, the hydrophobic isopropyl group at the portside of (R)-GS 83 is projected exactly toward the Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter (Fig. 3D). In comparison, the racemate of GS 87 and thus both enantiomers are inactive. In our model, the isopropyl group of (S)-GS 87 is oriented in the opposite direction and could not interact with the ion (Fig. 3C).

3) Mutations of Y3i10–F and Y4i11–F have been reported to increase the KD values for DHP binding by 12.4- and 3.5-fold, respectively (23). These data imply that DHP H-bonding with Y3i10 is more critical for the DHP potency than H-bonding with Y4i11. The NH group at the stern is considered an indispensable structural determinant of all DHPs. In the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation, the stern NH group of the DHP ligand H-bonds with the more critical Y3i10, whereas the bowsprit H-bonds with Y4i11. In different DHPs, the ortho and meta positions in the bowsprit have various polar groups, some of which, e.g. chlorine atoms, are weak H-bond acceptors. Assuming that the weaker H-bonding residue is likely associated with Y4i11, a stern-to-Y3i10 orientation seems more plausible.

Ca2+ Dependence of Agonist and Antagonist Binding to LTCC

To validate our proposal about the DHP orientation, we docked agonist (S)-Bay k 8644 in the stern-to-Y3i10 and stern-to-Y4i11 orientations. Modeling reveal that general orientation of the agonist in the channel is predictably the same as the complex with the antagonist, (S)-nimodipine described above (Fig. 4). A similarity is not surprising given a similar disposition of H-bonding groups in the DHP core of both the agonist and antagonist. After MC minimization of the less likely, stern-to-Y4i11 orientation, the portside methyl group in the ortho position to the stern NH group approaches the Ca2+ ion, whereas the NO2 group of (S)-Bay k 8644 is ∼5 Å away from the Ca2+ ion (not shown). The model predicts that agonist and antagonist interactions with the Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter could not be discriminated from each other in the stern-to-Y4i11 orientation. In the more likely, stern-to-Y3i10 orientation, the portside NO2 group of agonist (S)-Bay k 8644 is strongly attracted to the Ca2+ ion chelated by E3p50 and E4p50. The distance between the Ca2+ ion and oxygens of the NO2 group of (S)-Bay k 8644 is much smaller (∼3.5 Å) in the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Antagonist (S)-nimodipine and agonist (S)-Bay k 8644 in LTCC the Ca2+-saturated model. In the side views, S6 of the front domain is transparent. The hydrophobic portside group of the antagonist (A) approaches the Ca2+ ion chelated by the selectivity filter glutamates E3p50 and E4p50. This would cause the energetically expensive displacement of water molecules from the hydration shell of the Ca2+ ion and thus destabilization the Ca2+-saturated model, but not the Ca2+-deficient model with a single Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter. B, interaction of the NO2 group of the agonist with the Ca2+ ion does not lead to energy loss, because unfavorable partial dehydration of the ion is compensated by favorable electrostatic attraction with the nucleophilic group of the ligand.

Our modeling in the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation also predicts dramatically different patterns of LTCC interactions with antagonist (S)-nimodipine compared with the agonist (S)-Bay k 8644. If we superimpose (S)-nimodipine and (S)-Bay k 8644 in the Ca2+-saturated model and align their DHP rings, the hydrophobic portside group of (S)-nimodipine is very close (3.3 Å) to the Ca2+ ion chelated by E3p50 and E4p50. This binding mode of (S)-nimodipine would be unstable in the pore because of the prohibitive energetic cost for its portside hydrophobic group to dehydrate the Ca2+ ion. MC minimization of the channel complex with (S)-nimodipine decreases the dehydration cost of the Ca2+ ion and shifts it from the starting position, which corresponds to a MC-minimized structure of the DHP-free LTCC. However, a combined repulsion between the two Ca2+ ions and a strong attraction of the Ca2+ ions to the selectivity filter glutamates limits displacement of the Ca2+ ion (cf. Fig. 4, A and B). Intensive MC minimization of the complex resulted in negative ligand-channel energy, but a positive (unfavorable) energy contribution was found due to dehydration of the Ca2+ ion by the isopropyl group of (S)-nimodipine. Thus our calculations demonstrate that in the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation DHP agonists and antagonists should have opposite effects on the occupancy of the second Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter. All the presented modeling data with the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation of DHPs is consistent with the structure-activity relationship of DHPs observed in experiments and also consistent with our hypothesis of a direct (non-allosteric) influence of DHPs on the selectivity filter occupancy by a second Ca2+ ion.

Model Predictions for Key DHP-sensing Residues

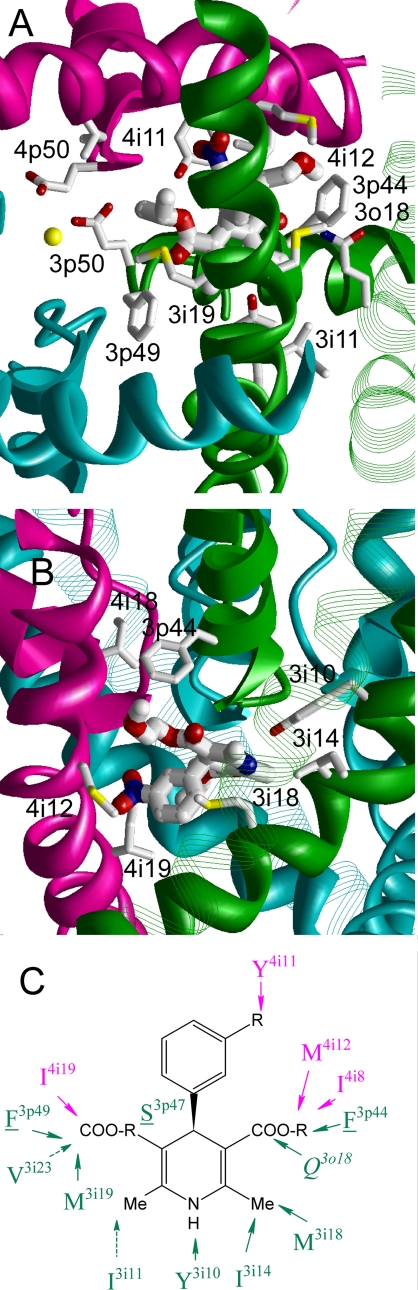

Using the favorable stern-to-Y3i10 orientation of (S)-nimodipine in the LTCC pore, we set out to verify whether the key DHP-sensing residues identified in previous mutational studies establish favorable contacts with the DHP ligand in our proposed model (Fig. 5). We docked the ligand in a Ca2+-deficient state in which the selectivity filter region was loaded with a single Ca2+ ion. This configuration was selected because the Ca2+-deficient state was proposed to favor binding of DHP antagonists (11). Summary of the modeling predictions of favorable DHP contacts with the channel are illustrated in Fig. 5C. The NH group at the stern forms an H-bond with Y3i10. The starboard methyl group fits into a hydrophobic pocket formed by I3i14 and M3i18. The portside group is bound in a hydrophobic pocket formed by M3i19, F3p49, and I4i19. The polar NO2 group at the bowsprit accepts an H-bond from the side chain of Y4i11. The carbonyl oxygen at the starboard accepts an H-bond from Q3o18. The side chain of T3o14 does not interact with the DHP molecule directly, but it is exposed toward the starboard group in such a way that its enlargement would sterically prevent DHP binding as was experimentally demonstrated (20). The hydrophobic part of the starboard substituent fits into a hydrophobic pocket formed by I4i8, M4i12, and F3p44. The DHP ring also formed contacts with side chains of S3p47 and T3p48 in the pore helix of domain III. All above described interactions provide negative (attractive) contributions to the ligand-channel interaction energy. No residue in the DHP binding site contributed significant positive energy, indicating that in the proposed binding mode the ligand did not form unfavorable contacts with the channel. The proposed structural model thus verifies that the key DHP-sensing residues, which were identified in previous mutational studies of LTCC, establish favorable contacts with the DHP ligand in the proposed stern-to-Y3i10 binding mode.

FIGURE 5.

Antagonist (S)-nimodipine the Ca2+-deficient model of LTCC. A and B, cytoplasmic and side views at the MC-minimized complex. The ligand is shown by thick sticks with hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. DHP-sensing residues are shown by thin sticks. A Ca2+ ion in the selectivity filter is shown as a small yellow sphere. C, a scheme of contacts between the ligand and known DHP-sensing residues.

Although the modeling predictions of DHP binding generally agree with previously published results of mutational analyses of the DHP receptor, some minor discrepancies were found. N4i20 was identified as a DHP-sensing residue in experiments (24), but our model did not predict that the asparagine was directly involved in DHP-channel interactions. We suggest that mutation of N4i20 likely has an indirect, allosteric effect of DHP potency because the residue side chain is exposed to the III–IV domain interface and interacts with IIIS6. Mutations of N3i20 were demonstrated to affect slow inactivation of the Na+ channel (42), but we are not aware of experiments addressing the effect of N4i20 on the gating properties of LTCC. Side chains of I3i11 and V3i23, which were identified as DHP-sensing residues in published experiments (20, 24), face the inner pore in our model but do not interact directly with DHPs. I3i11 and V3i23 reside at opposite edges of the DHP-binding region of IIIS6 at a minimal distance of 15 Å between each other according to our model and thus cannot simultaneously bind to a DHP ligand.

Residue F3i22 was not identified as a DHP-sensing residue in alanine-scanning mutagenesis experiments (24) but does provide a significant contribution to DHP ligand binding in our model. Disagreements such as F3i22 may be due to the dissimilarity of particular architectural details between LTCC and the K+ channel template. The above mentioned F3i22 and V3i23 residues of LTCC are located in the C-terminal half of IIIS6, which corresponds to the C-terminal half of S6 in KvAP that is variable, even within the K+ channel family. Evidence from superimposed x-ray structures of K+ channels, KvAP, MthK, and Kv1.2 confirm that there are noticeably different orientations in the C-terminal half of S6 (43). Given the likely greater variability between K+ and Ca2+ channels than within different K+ channels, we can assume that the orientations of the C-terminal halves of S6s of LTCC and KvAP may be even more different. For instance, a larger kink between the N- and C-terminal halves of IIIS6 in LTCC would near V3i23 and the bound (S)-nimodipine.

It should be noted that the proposed DHP binding mode was obtained with the help of the distance constraints imposed at the first stage of energy optimizations. The constraints caused deviations of the LTCC α-carbons from the KvAP template. These deviations remained after non-constrained MC minimizations at the second, refinement stage. However, not a single α-carbon of LTCC deviated from the KvAP template by more than 2 Å after the refinement stage. Also encouraging was that the DHP ligands generally retained the same position and orientation after removal of the DHP-LTCC distance constraints at the refining stage of energy optimizations. However, one or two H-bonds between LTCC and a DHP were lost at the refining stage. These facts likely reflect certain dissimilarity between the LTCC model and the KvAP template induced by docking of the inflexible DHP ligand. It leads us to use cautious interpretations of modeling predictions such as the position of the side chain of Y3i10 that approaches the P-helix of domain III and can form an H-bond with the side chain of DHP-sensing residue S3p47. This may be a valid prediction of a contact between two DHP-sensing residues or could be the result of a deviation imposed by distance constraints imposed on the structure.

State-dependent Binding of DHPs

DHP agonists and antagonists and other classes of LTCC blockers (phenylalkylamines and benzothiazepines) bind preferentially to the open/inactivated LTCC states, which are present at depolarized membrane potentials (for review, see Ref. 1). Noteworthy, various ligands of Na+ and K+ channels also demonstrate a state-dependent action. This agrees with the “modulated receptor” hypothesis (44). To reveal possible influence of the functional LTCC states on the DHP binding, we docked (S)-nimodipine to the closed-channel model using as a template the KcsA structure (33) with the closed activation gate. As was expected from simple geometrical reasons, (S)-nimodipine interacted weaker with the closed-LTCC model because some contacts with residues in the C-terminal halves of inner helices IIIS6 and IVS6 were lost (data not shown). Similar results were obtained for docking of benzothiazepines in the closed-channel model (3).

We do not think, however, that the different ligand-channel contacts alone can explain the state-dependent action of DHPs. Preferential binding to the open/inactivated states is a characteristic feature of various ligands of P-loop channels, which have largely different chemical structures, access pathways to the binding sites within the pore-forming domain, and binding determinants within the sites. A fundamental cause of the state dependence should be sought in more common features of ligand-channel interactions. For example, ligand binding may require displacement of metal ions and/or water molecules from the pore and this displacement could be more attainable in the open/inactivated state than in the closed state. We recently proposed a mechanism of coupled movement of ligands and permeant ions in the Na+ channel to explain state-dependent action of local anesthetics (45). Regrettably, lack of structural details of the inactivated state(s) of P-loop channels precludes simulations of the state-dependent ligand binding.

Large DHP Derivatives

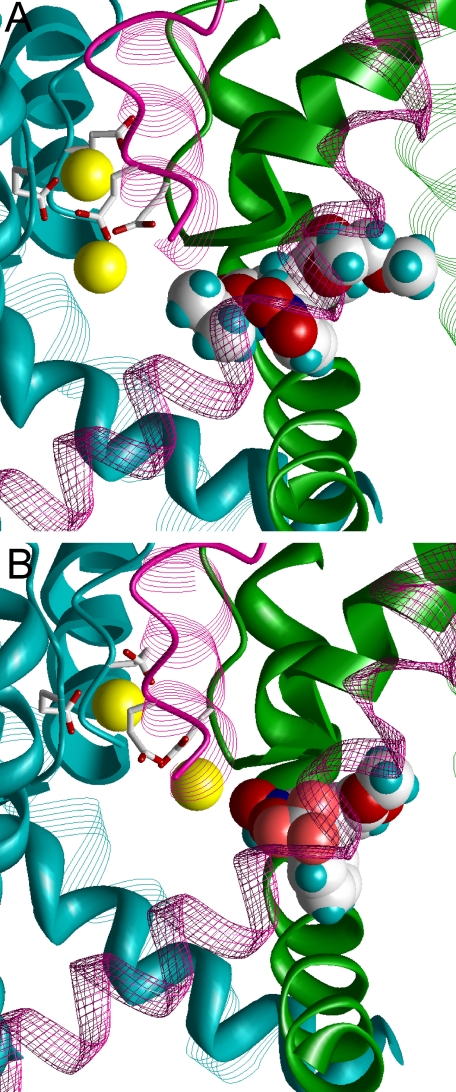

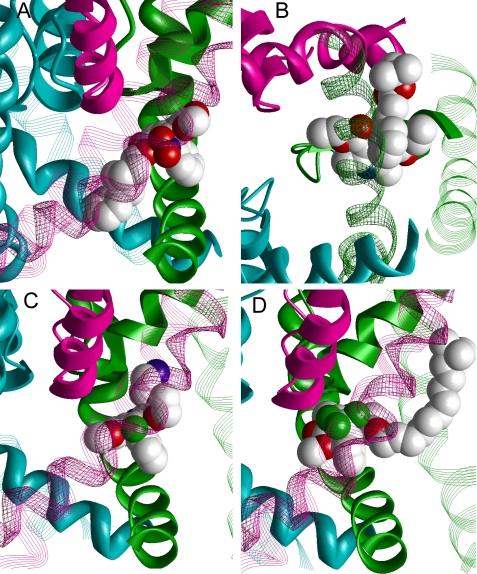

With the proposed model in hand, we sought to analyze a number of DHP derivatives to test the robustness of the LTCC homology model for prediction. Although the model is not precise enough to quantitatively evaluate the structure-activity relationships of DHPs, we chose several DHP derivatives with large substituents and confirmed that our model could accommodate these ligands. The achiral DHP antagonist lacidipine (46) and several chiral DHP antagonists were selected for analysis: (R)-amlodipine (47), (4S)-benidipine (48), and (S)-BK-10 (18), see Fig. 1. These ligands have large substituents at different positions of the DHP and aromatic rings. It was not clear a priori whether the proposed DHP binding pocket could accommodate these substituents. Results are shown in Fig. 6, illustrating the successful docking of these bulky DHP derivatives. First, the bulky substituent at the portside of (4S)-benidipine fits into the pore (Fig. 6A) in a manner that is similar to the proposed docking model of the benzothiazepine, benziazem in LTCC (3). Second, the flexible chain at the bowsprit of lacidipine readily accommodates in the cleft between helices IIIS5 and IIIS6 without disrupting major DHP-channel contacts (Fig. 6B). Third, the starboard extension of (R)-amlodipine projected toward the interface between domains III and IV (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Binding of large DHPs. Ligands are space-filled and their hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and chlorine atoms are light gray, red, blue, and green, respectively. Helices obstructing the view of the ligands are transparent. A, side view at the complex with (4S)-benidipine whose bulky portside substituent lies in the inner pore. B, cytoplasmic view at the complex with lacidipine. The long thin flexible substituent in the ortho position of the bowsprit ring is readily accommodated in the cleft between helixes IIIS5 and IIIS6. C, side view at the complex with (R)-amlodipine. The long substituent in the DHP ring is accommodated in the interface between domains III and IV. D, complex with (S)-BK-10 (18) whose decamethylene chain extends along the pore helix of domain III. The latter lines a proposed hydrophobic access pathway for certain ligands of P-channels (45). The quaternary ammonium group is near the outer surface of the membrane.

We next docked (S)-BK-10 with a decamethylene linker (Fig. 1). Racemic BK-10 was found as the most potent LTCC blocker in a series of DHP derivatives synthesized with a variable length linker between the DHP ring and the permanently charged trimethylammonium group. These variable length linkers were used to investigate the access pathway and depth of the DHP binding site relatively to the extracellular surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (18, 49). (We are not aware of relative potency of the BK-10 enantiomers, but low nanomolar potency was reported for both enantiomers of a related DHP with an octamethylene linker (50).) Docking of (S)-BK-10 in the stern-to-Y3i10 orientation predicted an energetically optimal binding mode with the linker extending in the interface between domains III and IV along the pore helix of domain III, whereas the trimethylammonium group reached the membrane-exposed entrance to the III/IV domain interface. This binding mode highlights a probable access pathway of DHPs from the extracellular medium to the binding site inside the pore. Noteworthy, the same access pathway named “sidewalk” was recently proposed to explain the block of the closed Na+ channels by local anesthetics (45). These data show that docking of large DHP derivatives did not reveal sterical hindrances, which would impede H-bonding with DHP-sensing residues Y3i10, Y4i11, and Q3o18. Our model predicts that the DHP receptor is tolerant to large substituents at the portside, starboard, and bow. Although the DHP ring binds to the III/IV domain interface, bulky substituents find room to extend either in the inner-pore lumen or to the III/IV domain interface.

DISCUSSION

A Novel Mechanism for DHP Antagonism in LTCC

In the present work we proposed that different molecular mechanisms and different targets within LTCC are responsible for the agonistic and antagonistic effects of DHPs. Our model is a departure from previously proposed models (30–32), which considered actions of agonists and antagonists on the same target within LTCC. Instead of different molecular mechanisms, these earlier models suggested that the DHP portside group is the determinant for the agonist or antagonist behaviors of DHPs. Hydrophobic or hydrophilic substituents were expected to impart corresponding stabilizing or destabilizing influences on the closed activation gate (the target) located at the hydrophobic crossover of the inner channel helices.

Previous models could not explain the following experimental observations: (i) antagonists exhibit agonist-like activities; (ii) the same DHP ligand may display agonistic or antagonistic activities depending on the experimental conditions; and (iii) single channel mutations cause switching of the DHP phenotype from agonist into antagonist.

We suggest that the antagonistic effect of DHPs is due to the hydrophobic portside group. We predict that exposure of this hydrophobic group to the selectivity filter region prevents binding of a second Ca2+ ion. This model suggests that DHP antagonists stabilize an impermeable state with a single Ca2+ ion. Our model agrees with the supposition that DHP binding transforms the channel into a specific inactivated state (51).

Basing on our initial assumptions, we generated molecular models and uncovered key DHP-sensing residues forming the high affinity DHP binding pocket. Our work revealed a good agreement between the key DHP-binding residues identified in structural modeling and those discovered in published experiments. Modeling provided a likely orientation of DHPs in the binding pocket, and a possible extracellular access pathway for DHPs entry to the binding site. The proposed model accommodates binding of various DHP derivatives even with large substituents, and provides a mechanism for different interactions of agonists and antagonists with Ca2+ ions in the pore.

Permeant Ions and Ligand Activity in Ion Channels

A key feature in our model is the direct interaction of DHPs with Ca2+ ions in the pore. It explains non-monotonic (bell-shaped) Ca2+ dependence of DHP action and different effects of agonists and antagonists on the Ca2+ occupancy of the selectivity filter. Such interplay between ion channel ligands and permeant ions is not a novel concept (31, 52). Important experimental details were recently uncovered for block of the KcsA channel by tetrabutylammonium (53). The binding mode of tetrabutylammonium was shown to depend on the ion configuration in the selectivity filter and the electrostatic repulsion between the K+ ion and the ligand. A similar mechanism (54) was used to describe the dependence of local anesthetic activity in Na+ channels on the ion content (55, 56). In addition, some favorable interactions with the permeant cations can enhance potency of the pore-bound ligands (3, 38).

A Novel Mechanism for DHP Agonism in LTCC

Ca2+ channels have at least two open states, namely short lasting and long lasting open states. DHPs (both agonists and antagonists) increase the probability of the long lasting open state (5). Thus, all DHPs (even antagonists) have an inherent capacity for agonistic activity. Obviously, this capacity for agonist activity is provided by shared DHP core structures in agonists and antagonists rather than by particular features in portside groups, which are highly variable among DHPs.

How does the DHP molecule stabilize a particular channel conformation? The inflexible, bound DHP ligand resides in the pore tethered by H-bonding to a triad of key DHP sensing residues Y3i10, Y4i11, and Q3o18 in transmembrane helices IIIS5, IIIS6, and IVS6 and also interacts with the pore helix of domain III. Specific interactions of a DHP molecule with different channel segments require a specific spatial disposition of the segments, i.e. a specific conformation of the channel. This clamping of an open channel conformation by multipoint interactions of a ligand with different channel segments is suggested here as a fundamental mechanism of agonistic action of DHPs.

The Dual Character of Channel Agonism/Antagonism

A dual (agonist and antagonist) character of DHPs is supported by experimental data. Particular channel mutations that destroy DHP agonist activity reveal a hidden, weakened antagonism (21, 22). It can be understood that mutations that weaken agonist activity equally perturb both antagonist and agonist binding strength to DHP sensing residues. Residual antagonism remains apparent in this scenario, but the agonist phenotype is suppressed from a loss of the clamp that holds the channel in the long lasting, open state conformation. Many studies suggest that the structural requirements for agonism are more complex than those required for antagonism (22, 25, 27, 29, 57).

Combined agonistic and antagonistic properties are not a unique feature of DHPs. Na+ channel activators (e.g. batrachotoxin, veratridine, and aconitine) and blockers (e.g. pancuronium, veratramine, and lappaconitive) bind in the same region of the inner pore and differ mainly in their capacity to interact with the permeant ions (58). The activators do not obstruct ion flow since their hydrophilic groups are exposed to the permeation pathway. Channel blockers occlude the pore with exposure of their hydrophobic or positively charged groups in the pore lumen. The proposal of the mechanisms (58) aided in predicting novel ligand-sensing residues of the P-loop of the Na+ channel (59) and segment IS6 (60). It led to the design of a point mutation in segment IIS6 that converted batrachotoxin from a channel activator into a blocker (61). A major difference between agonists of Na+ and Ca2+ channels is the mechanism of the agonism. The Na+ channel agonists stabilize the open state by a “foot in the door” mechanism, in which a large ligand occupies the open inner pore and prevents the activation gate closure. In contrast, DHP agonists bind in the domain interface of LTCC according to our present model, and favor the open gate conformation by specific interactions with various channel segments, including two inner helices and an outer helix.

Words of Caution

It should be clearly spelled out that our present model was not obtained from unbiased computations. Following the initial hypothesis, we first imposed specific binding modes of DHPs by distance constraints with the LTCC and then relaxed the binding modes in non-constrained energy optimizations. This strategy was employed because of the likely imprecision of the LTCC model based on the KvAP (bacterial K+ channel) template.

It should be noted that structural details of the long lasting open state of LTCC, which predicts a set of H-bonded DHP-sensing residues interacting with DHP ligands, may not match any of the available x-ray templates. Indeed, the distance between α-carbons in positions corresponding to the H-bonding triad Y3i10, Y4i11, and Q3o18 significantly vary even among available structures of K+ channels (Table 2). It limits the precision of the KvAP-based homology model of LTCC and limits the details of the disposition of the transmembrane helices, which is favored by binding of DHP ligands.

TABLE 2.

Distances (Å) between α -carbons in the K+ channels positions that correspond to the H-bonding triad of LTCC

| Template | LTCC residues defining corresponding positions in K+ channels |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Y3i10–Y4i11 | Y3i10–Q3o18 | Q3o18–Y4i11 | |

| Kv1.2 (43) | 15.5 | 8.6 | 13.7 |

| KvAP (4) | 18.6 | 7.6 | 15.2 |

| MthK (65) | 15.4 | 8.5 | 13.8 |

| KcsA (33) | 16.0 | 6.4 | 15.3 |

Validation of using a homology modeling to infer features of the three-dimensional structure of related proteins without available crystallographic data is particularly important for voltage-gated Ca2+ and Na+ channels. Results from a report by Zhen et al. (62) appeared at first glance to dismiss our homology based approach using K+ channels. Meticulous analyses of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels were performed using the substituted cysteine accessibility method, which lead to a proposition that transmembrane helices in the pore-forming domains of Ca2+ and K+ channels have different orientations (62). However, recent modeling of the MTSET-modified cysteine mutants of Zhen et al. (62) supports generally similar disposition and orientation of the inner and outer helices between the voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels (63).

To explain actions of DHPs, we did not built a new model of LTCC, but used a previously described KvAP-based model (3). Thus, our model of DHP binding agrees with previous assumptions for multiple sequence alignments of S5s (64), P-helices (31), and S6s (31) between K+ and Ca2+ channels. It also agrees with the P-loop domain model of the Na+ channel (34), which we used as a template to provide a specific location of the selectivity filter residues in the outer pore of LTCC (3). In the present study we observed modest deviation from the KvAP template, which occurred to satisfy strong requirements of forming specific H-bonds between inflexible DHP molecule and different transmembrane segments of the channel. Thus, both DHPs and benzothiazepines (3) fit the same model of LTCC with only minor discrepancies.

Conclusion

Three decades of experimental studies have passed without a DHP binding model that adequately describes the spectrum of features reported in experimental studies (1, 2). Here we introduce a novel structural model, which describes the likely mode of interaction of DHPs with LTCC and outlines key DHP-sensing residues. We also address the roles of permeant ions in ligand activity, and structure-activity relationships between agonists, antagonists, and DHPs with large substituents. The model provides an important starting point for exploring novel pharmacophores for Ca2+ channels.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to David Spafford (Department of Biology, University of Waterloo) for critical reading of the manuscript and many valuable suggestions. Computations were performed using the facilities of the Shared Hierarchical Academic Research Computing Network (SHARCNET).

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to B. S. Z.).

- DHP

- dihydropyridine

- LTCC

- L-type Ca2+ channel

- MC

- Monte Carlo

- MCM

- Monte Carlo minimization

- MTSET

- (2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl)methanethiosulfonate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hockerman G. H., Peterson B. Z., Johnson B. D., Catterall W. A. (1997) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 37, 361–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacinová L. (2005) Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 24, Suppl. 1, 1–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17594–17604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Ruta V., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2003) Nature 423, 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess P., Lansman J. B., Tsien R. W. (1984) Nature 311, 538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams J. S., Grupp I. L., Grupp G., Vaghy P. L., Dumont L., Schwartz A., Yatani A., Hamilton S., Brown A. M. (1985) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 131, 13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokubun S., Reuter H. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 4824–4827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kass R. S. (1987) Circ. Res. 61, I1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitterdorfer J., Sinnegger M. J., Grabner M., Striessnig J., Glossmann H. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 9350–9355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson B. Z., Catterall W. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18201–18204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson B. Z., Catterall W. A. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldmann S., Stoltefuss J. (1991) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 30, 1559–1578 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franckowiak G., Bechem M., Schramm M., Thomas G. (1985) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 114, 223–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hof R. P., Rüegg U. T., Hof A., Vogel A. (1985) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 7, 689–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kass R. S., Arena J. P., Chin S. (1991) J. Gen. Physiol. 98, 63–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kass R. S., Arena J. P. (1989) J. Gen. Physiol. 93, 1109–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan Y. W., Bangalore R., Lakitsh M., Glossmann H., Kass R. S. (1995) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 27, 253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangalore R., Baindur N., Rutledge A., Triggle D. J., Kass R. S. (1994) Mol. Pharmacol. 46, 660–666 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi S., Zhorov B. S., Yoshioka K., Nagao T., Ichijo H., Adachi-Akahane S. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 235–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wappl E., Mitterdorfer J., Glossmann H., Striessnig J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12730–12735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi S., Okamura Y., Nagao T., Adachi-Akahane S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41504–41511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster A., Lacinová L., Klugbauer N., Ito H., Birnbaumer L., Hofmann F. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 2365–2370 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson B. Z., Tanada T. N., Catterall W. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5293–5296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson B. Z., Johnson B. D., Hockerman G. H., Acheson M., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18752–18758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He M., Bodi I., Mikala G., Schwartz A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2629–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito H., Klugbauer N., Hofmann F. (1997) Mol. Pharmacol. 52, 735–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodi I., Yamaguchi H., Hara M., He M., Schwartz A., Varadi G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24952–24960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hockerman G. H., Peterson B. Z., Sharp E., Tanada T. N., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 14906–14911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabner M., Wang Z., Hering S., Striessnig J., Glossmann H. (1996) Neuron 16, 207–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosconati S., Marinelli L., Lavecchia A., Novellino E. (2007) J. Med. Chem. 50, 1504–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhorov B. S., Folkman E. V., Ananthanarayanan V. S. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 393, 22–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipkind G. M., Fozzard H. A. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63, 499–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle D. A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R. A., Kuo A., Gulbis J. M., Cohen S. L., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (1998) Science 280, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2005) Biophys. J. 88, 184–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazaridis T., Karplus M. (1999) Proteins 35, 133–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiner S. J., Kollman P. A., Case D. A., Singh U. C., Ghio C., Alagona G., Profeta S., Weiner P. (1984) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 765–784 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiner S. J., Kollman P. A., Nguen D. T., Case D. A. (1986) J. Comput. Chem. 7, 230–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruhova I., Zhorov B. S. (2007) BMC Struct. Biol. 7, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Z., Scheraga H. A. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6611–6615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towart R., Wehinger E., Meyer H., Kazda S. (1982) Arzneimittelforschung 32, 338–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wanner-Olsen H., Gaarskaer F. B., Mikkelsen E. O., Jakobsen P., Voldby B. (2000) Chirality 12, 660–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y., Yu F. H., Surmeier D. J., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2006) Neuron 49, 409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long S. B., Campbell E. B., Mackinnon R. (2005) Science 309, 897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hille B. (1977) J. Gen. Physiol. 69, 497–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruhova I., Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1033–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cerbai E., DeBonfioli Cavalcabó P., Masini I., Visentin S., Giotti A., Mugelli A. (1990) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 15, 604–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arrowsmith J. E., Campbell S. F., Cross P. E., Stubbs J. K., Burges R. A., Gardiner D. G., Blackburn K. J. (1986) J. Med. Chem. 29, 1696–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muto K., Kuroda T., Kawato H., Karasawa A., Kubo K., Nakamizo N. (1988) Arzneimittelforschung 38, 1662–1665 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baindur N., Rutledge A., Triggle D. J. (1993) J. Med. Chem. 36, 3743–3745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peri R., Padmanabhan S., Rutledge A., Singh S., Triggle D. J. (2000) J. Med. Chem. 43, 2906–2914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berjukow S., Marksteiner R., Gapp F., Sinnegger M. J., Hering S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22114–22120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhorov B. S., Ananthanarayanan V. S. (1996) Biophys. J. 70, 22–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faraldo-Gómez J. D., Kutluay E., Jogini V., Zhao Y., Heginbotham L., Roux B. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 365, 649–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2007) Biophys. J. 93, 1557–1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cahalan M. D., Almers W. (1979) Biophys. J. 27, 39–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Z., Ong B. H., Kambouris N. G., Marbán E., Tomaselli G. F., Balser J. R. (2000) J. Physiol. 524, 37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitterdorfer J., Wang Z., Sinnegger M. J., Hering S., Striessnig J., Grabner M., Glossmann H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 30330–30335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 4207–4212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang S. Y., Mitchell J., Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S., Wang G. K. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 788–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang S. Y., Tikhonov D. B., Zhorov B. S., Mitchell J., Wang G. K. (2007) Pflugers Arch. 454, 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S. Y., Tikhonov D. B., Mitchell J., Zhorov B. S., Wang G. K. (2007) Channels 1, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhen X. G., Xie C., Fitzmaurice A., Schoonover C. E., Orenstein E. T., Yang J. (2005) J. Gen. Physiol. 126, 193–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bruhova I., Zhorov B. S. (2009) Biophys. J. 96, 183a (abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huber I., Wappl E., Herzog A., Mitterdorfer J., Glossmann H., Langer T., Striessnig J. (2000) Biochem. J. 347, 829–836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang Y., Lee A., Chen J., Cadene M., Chait B. T., MacKinnon R. (2002) Nature 417, 515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]