Abstract

Background

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are beneficial probiotic organisms that contribute to improved nutrition, microbial balance, and immuno-enhancement of the intestinal tract, as well as lower cholesterol. Although present in many foods, most trials have been in spreads or dairy products. Here we tested whether Bifidobacteria isolates could lower cholesterol, inhibit harmful enzyme activities, and control fecal water content.

Methods

In vitro culture experiments were performed to evaluate the ability of Bifidobacterium spp. isolated from healthy Koreans (20~30 years old) to reduce cholesterol-levels in MRS broth containing polyoxyethanylcholesterol sebacate. Animal experiments were performed to investigate the effects on lowering cholesterol, inhibiting harmful enzyme activities, and controlling fecal water content. For animal studies, 0.2 ml of the selected strain cultures (108~109 CFU/ml) were orally administered to SD rats (fed a high-cholesterol diet) every day for 2 weeks.

Results

B. longum SPM1207 reduced serum total cholesterol and LDL levels significantly (p < 0.05), and slightly increased serum HDL. B. longum SPM1207 also increased fecal LAB levels and fecal water content, and reduced body weight and harmful intestinal enzyme activities.

Conclusion

Daily consumption of B. longum SPM1207 can help in managing mild to moderate hypercholesterolemia, with potential to improve human health by helping to prevent colon cancer and constipation.

Background

Probiotic bacteria have multiple potential health effects, including blocking gastroenteric pathogens [1-4], neutralizing food mutagens produced in the colon [1,5-10], enhancing the immune response [6,9,11-14], lowering serum cholesterol, and stopping intestinal dysfunction [15-21]. In general, probiotic bacteria must colonize the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of the host, have acid- and bile salt-tolerance, and block putrefactive bacteria in the GIT. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), especially Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. are important GIT residents and are used as probiotic strains to improve health [22-24]. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been used in fermented foods for several centuries without adverse effects [25,26] and are classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) because of their long history of safe use, particularly in dairy foods [27,28].

Here, we evaluated the ability of Bifidobacteria spp. isolated from healthy Koreans (20~30 years old) to lower cholesterol, inhibit harmful enzyme activities, and control the fecal water content.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

The origins of the strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Isolation of Bifidobacteria was performed from fecal samples of healthy Koreans (20~30 years old) collected by BBL's anaerobic sample collection and transport system to maintain anaerobic conditions, and were used within 24 h. Fecal samples were serially diluted 10-fold from 10-1 to 10-8, and 100 μl was spread onto selective BL agar containing 5% sheep blood. After 48 h of incubation in anaerobic conditions (90% N2, 5% H2, 5% CO2) (Bactron Anaerobic Chamber, Sheldon Manufacturing Inc., USA) at 37°C, brown or reddish-brown colonies 2~3 mm in diameter were selected for further identification [29].

Table 1.

List of lactic acid bacteria used in this study

| Bacterial strains | Source | Origin |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM1005 | Isolatea | Human feces |

| Bifidobacterium longum SPM1207 | Isolate | Human feces |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM1601 | Isolate | Human feces |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis KCTC3352 | Commercialb | Intestine of adult |

| Bifidobacterium longum KCTC3128 | Commercial | Intestine of adult |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus (LH) CBT | Commercial | NAc |

| Lactobacillus plantarum KCTC1048 | Commercial | NA |

| Lactobacillus plantarum (LP) CBT | Commercial | NA |

| Enterococcus faecium SPM1206 | Isolate | Human feces |

aIsolated from healthy Korean

bPurchased from Korean Collection for Type Culture (KCTC)

cNot available

A fructose-6-phosphate phosphoketolase (F6PPK) test was performed [30] to ensure that the colonies selected were Bifidobacteria. To identify the isolated Bifidobacterium spp. at the species level, 16s rRNA sequencing was performed by Bioleaders (Daejeon, Korea).

In vitro cholesterol-lowering test

MRS broth (pH7.0) (Difco, USA) containing 0.05% L-cysteine·HCl·H2O (w/v) was prepared and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min. Soluble cholesterol (polyoxyethanyl-cholesterol sebacate, Sigma, USA) was added to the prepared MRS broth and filtered through a 0.45 μm Millipore filter. The inoculation volume was 15 μl of provisional probiotic bacterial culture (108~109 CFU/ml) solution per 1 ml cholesterol-MRS broth, and that was anaerobically incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Uninoculated MRS broth was also incubated at 37°C for 24 h for the control.

Following incubation, bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation (3,000 rpm, 10 min), and the spent broth and uninoculated control broth were then assayed for their cholesterol content. The remaining volume of cholesterol in the cholesterol-MRS broth was determined by the method reported by Rudel and Morris with a small modification [31]. To measure the amount of cholesterol, the dye layer is observed at 560 nm.

Experimental animals and diets

A total of 24 Sprague-Dawley (SD) male rats (5-week-old) were purchased from Central Lab Animal Inc. (Korea), and were housed in a temperature-controlled animal room (22 ± 2°C) with a 12 h light/dark cycle and humidity 55 ± 5%. Food and water were freely supplied. The animals were randomly selected and assigned to three groups (8 rats per group) according to the type of diet. Group 1 was fed a normal diet. Group 2 was fed a high-cholesterol diet and saline (as control). Group 3 was fed a high-cholesterol diet and B. longum SPM1207 (the best strain at lowering cholesterol in vitro). The composition of high-cholesterol feed is shown in Table 2. All the rats were acclimatized to the respective diets for a week before the experiment started. Rats in groups 2 or 3 received daily administrations of 0.2 ml of saline or B. longum SPM1207 (108~109 CFU/ml), respectively, for 2 weeks. Body weight was monitored weekly and food consumption was monitored daily.

Table 2.

Compositions of high-cholesterol diets for SD rats

| Ingredients | Compositions | |

| g | kcal | |

| Casein (from milk) | 200 | 800 |

| Corn Starch | 155.036 | 620 |

| Sucrose | 50 | 200 |

| Dextrose | 132 | 528 |

| Cellulose | 50 | 0 |

| Soybean Oil | 25 | 225 |

| Lard | 175 | 1575 |

| Mineral Mixture | 35 | 0 |

| Vitamin Mixture | 10 | 40 |

| TBHQ | 0.014 | 0 |

| DL-Methionine | 0 | 0 |

| L-Cystine | 3 | 12 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.5 | 0 |

| Total | 838 | 4,000 |

| Cholesterol | 20 g/kg | (2%) |

| Cholic acid | 5 g/kg | (0.5%) |

Analysis of blood serum

At the end of the experimental period of 3 weeks, blood samples from each animal were collected into tubes by cardiac puncture to determine the serum cholesterol level. Serum was separated from the blood by centrifugation at 3,500 rpm for 10 min. The total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol were analyzed by Samkwang Lab (Korea).

Fecal sampling and bacteriological analysis

Fecal samples were collected weekly to determine the number of LAB, harmful enzyme activity, and water content. Fecal samples were taken directly from the rectum by rectal stimulation and immediately transferred into sterile tubes and kept at 4°C. Total LAB counts was performed on MRS-agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h under anaerobic conditions (90% N2, 5% H2, 5% CO2). The numbers of colony forming units (CFU) are expressed as log10 CFU per gram.

Harmful enzyme activity of rat intestinal microflora

Enzyme activities related to colon cancer were tested in fecal samples of rats as previously described [32-34].

Tryptophanase activity assay

Tryptophanase activity was assayed using 2.5 ml of a reaction mixture consisting of 0.2 ml of complete reagent solution (2.75 mg pyridoxal phosphate, 19.6 mg disodium EDTA dihydrate, and 10 mg bovine serum albumin in 100 ml of 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5), 0.2 ml of 20 mM tryptophan, and 0.1 ml of the enzyme solution (suspended fecal sample), incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and then stopped by adding 2 ml of color reagent solution (14.7 g p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in 52 ml H2SO4 and 948 ml 95% ethanol). The stopped reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min and enzyme activity was measured by monitoring absorbance at 550 nm.

Urease activity assay

Urease activity was assayed using 0.5 ml of a reaction mixture consisting of 0.3 ml of urea substrate solution (4 mM urea in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) and 0.1 ml of the enzyme solution (suspended fecal sample) incubated for 30 min at 37°C and then stopped by adding 0.1 ml of 1 N (NH4)2SO4. Phenolnitroprusside reagent (1 ml) and alkaline hypochlorite reagent (NaClO, 1 ml) were added to the stopped reaction mixture and incubated for 20 min at 65°C. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring absorbance at 630 nm.

β-glucosidase activity assay

β-glucosidase activity was assayed using 2 ml of a reaction mixture consisting of 0.8 ml of 2 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside and 0.2 ml of the enzyme solution (suspended fecal sample), incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and then stopped by adding 1 ml of 0.5 N NaOH. The stopped reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring absorbance at 405 nm.

β-glucuronidase activity assay

β-glucuronidase activity was assayed using 2 ml of a reaction mixture consisting of 0.8 ml of 2 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucuronide and 0.2 ml of the enzyme solution (suspended fecal sample), incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and then stopped by adding 1 ml of 0.5 N NaOH. The stopped reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring absorbance at 405 nm.

Measurement of fecal water content

The water content of fecal samples was measured using a drying oven (105°C, 24 h). Fecal water content (%) is calculated by:

where Wwet and Wdry are the weight of the fecal sample before and after drying in the oven.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For statistical evaluation of data, one-way ANOVA was applied using SPSS 13.0 for Windows followed by post hoc comparisons using the Tukey's test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Isolation and characterization of B. longum SPM1207

B. longum SPM1207 isolated from healthy Korean faeces was Gram-positive rods, with a translucent glossy colony on general anaerobic medium (GAM, Nissui Pharm. Co. Ltd., Japan) under anaerobic conditions (90% N2, 5% H2, 5% CO2). Sequence analysis (Figure 1) and BLAST searches indicated that the 16s rRNA sequences in this strain showed 99% homology with Bifidobacterium longum DJO10A.

Figure 1.

Sequence analyses of the B. longum SPM1207-16s rRNA gene shows 99% identity with B. longum DJO10A (879 bp).

In vitro cholesterol-lowering test

Among the tested strains, B. longum SPM1207 had the highest cholesterol-reducing activities in MRS broth containing cholesterol (Table 3). On average, Bifidobacterium showed higher cholesterol-reducing activities than Lactobacillus. And the strains presented different cholesterol lowering effects despite being the same species. The effect of B. longum SPM1207 was 2 times higher than B. longum KCTC3128.

Table 3.

Amount of residual cholesterol after in vitro incubation of selected lactic acid bacteria

| Species | Residual cholesterol (mg/dl) |

Cholesterol lowering ratio (%) | p value |

| Controla | 345.0 ± 5.7b | - | - |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM1005 | 318.7 ± 3.0 | 7.6 | p < 0.05c |

| Bifidobacterium longum SPM1207 | 262.8 ± 1.3 | 23.8 | p < 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM1601 | 283.3 ± 2.6 | 17.9 | p < 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis KCTC3352 | 329.0 ± 5.6 | 4.6 | p < 0.05 |

| Bifidobacterium longum KCTC3128 | 303.8 ± 6.0 | 11.9 | p < 0.05 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus (LH) CBT | 321.7 ± 1.9 | 6.7 | p < 0.05 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum KCTC1048 | 314.0 ± 4.4 | 9.0 | p < 0.05 |

| Lactobacillus plantarum (LP) CBT | 296.3 ± 5.0 | 14.1 | p < 0.05 |

| Enterococcus faecium SPM1206 | 300.9 ± 1.7 | 12.8 | p < 0.05 |

aMRS broth containing cholesterol without lactic acid bacteria

bEach value provided is the mean ± SD

cp < 0.05 significantly different compared with control

Lowering of serum cholesterol in rats

We then tested the hypocholesterolemic effects of this LAB in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. A high cholesterol diet increased serum cholesterol levels (Table 4). B. longum SPM1207 treatment reduced total cholesterol from 111.3 to 84.4 mg/dl and LDL-cholesterol levels from 33.3 to 23.5 mg/dl. In addition, B. longum SPM1207 slightly increased HDL-cholesterol levels, but did not significantly (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of the B. longum SPM1207 on serum total-, HDL-, and LDL-cholesterol of SD rats fed on a high-cholesterol diet

| Index | Basal diet | High-cholesterol diet | p value | |

| Control | SPM1207b | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) |

55.0 ± 5.5a | 111.3 ± 25.2 | 84.8 ± 4.3 | p < 0.05c |

| HDLe-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

23.9 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 2.6 | 30.6 ± 1.5 | NSd |

| LDLf-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 11.6 ± 1.1 | 33.3 ± 8.5 | 23.5 ± 2.3 | p < 0.05 |

aEach value provided is the mean ± SD for 8 rats.

bBifidobacterium longum SPM1207 isolated from healthy Korean.

cp < 0.05 significantly different compared with control.

dNS: not significant.

eHDL: high density lipoprotein,

fLDL: low density lipoprotein

Fecal water content, body weight, and bacteriological analysis

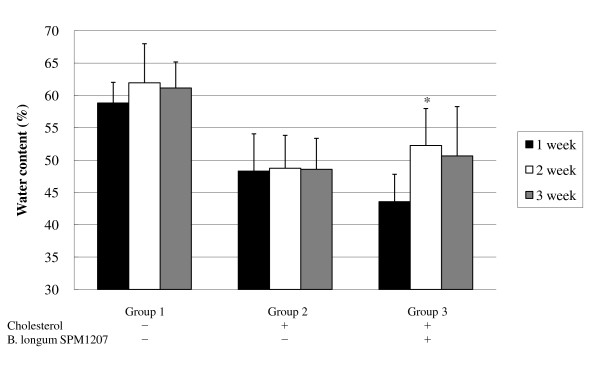

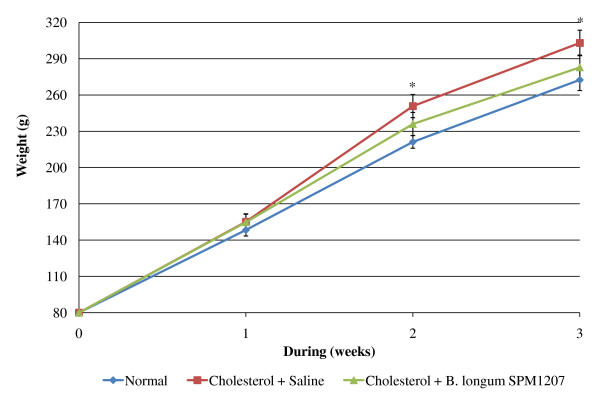

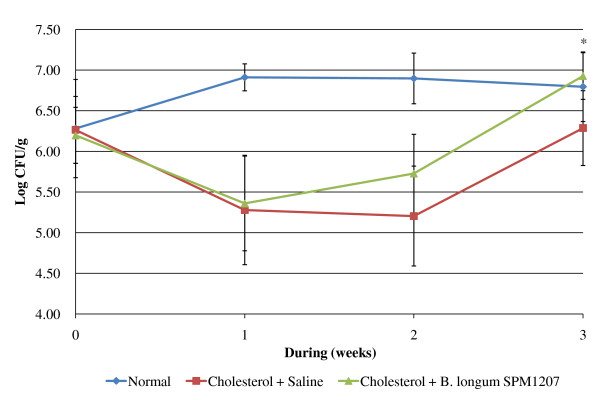

The high cholesterol diet caused dry feces, but B. longum SPM1207 treatment increased fecal water content (Figure 2). The high cholesterol diet also increased body weight after 2 weeks, but B. longum SPM1207 blocked this increase (Figure 3). Fecal LAB counts were similar in all groups before the experimental diets, but a high-cholesterol diet lowered LAB counts. LAB administration increased fecal LAB counts from 5.3 log10 CFU/g to 6.9 log10 CFU/g, which was significantly higher than controls (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Effect of B. longum SPM1207 on fecal water content. All rats were acclimatized to the respective diets for a week. Then the rats in group 2 or 3 received daily 0.2 ml saline or B. longum SPM1207 (108~109 CFU/ml), respectively, for 2 weeks. Data are presented as means and standard deviation. *p < 0.05 significantly different compared with 1 week.

Figure 3.

Changes in body weight fed experimental diets for 3 weeks. All rats were acclimatized to the respective diets for a week. Then the rats in group 2 or 3 received daily 0.2 ml saline or B. longum SPM1207 (108~109 CFU/ml), respectively, for 2 weeks. Data are presented as means and standard deviation. *p < 0.05 significantly different compared with control (Cholesterol + Saline).

Figure 4.

Changes in total LAB counts in rats fed experimental diets for 3 weeks. All rats were acclimatized to the respective diets for a week. Then the rats in group 2 or 3 received daily 0.2 ml saline or B. longum SPM1207 (108~109 CFU/ml), respectively, for 2 weeks. Data are presented as means and standard deviation. *p < 0.05 significantly different compared with control (Cholesterol + Saline).

Inhibitory effect on harmful enzyme of rat intestinal microflora

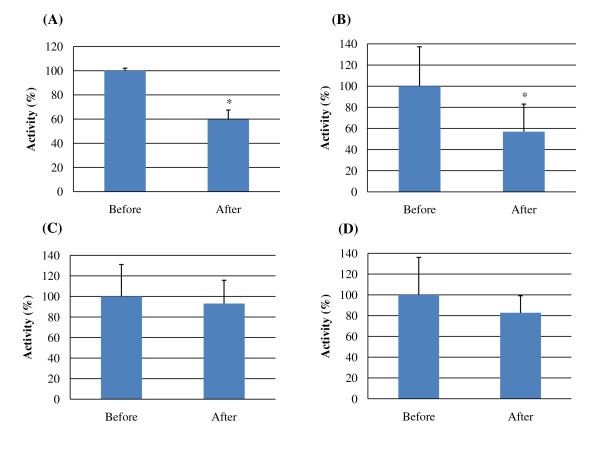

B. longum SPM1207 significantly inhibited tryptophanase and urease activities and slightly decreased β-glucosidase and β-glucuronidase activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In vivo inhibitory effects of B. longum SPM1207 on fecal harmful enzymes in rats fed on high-cholesterol diet. (A) Tryptophanase activity, (B) Urease activity, (C) β-glucosidase activity, (D) β-glucuronidase activity; Before: before the experiment started, After: at the end of experiment.

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease is the most important cause of death in westernized countries, including Korea. In the United States, 10 million people suffer from ischemic coronary arterial diseases, and spend 115 billion dollars per year to treat it [19]. According to NHANES (the third national health and nation examination survey) data and NCEP (national cholesterol education program) guide, a half million people have died of ischemic cardiac disease. [19,35].

Hypercholesterolemia is strongly associated with coronary heart disease and arteriosclerosis [35-38], and decreasing serum cholesterol is an important treatment option. HDL-cholesterol can prevent arteriosclerosis by removing cholesterol from the blood stream, whereas LDL-cholesterol causes accumulation of cholesterol in blood vessels [35,39]. According to Frick et al. [40], every 1% reduction in body cholesterol content lowers the risk for cardiovascular diseases by 2%. Therapeutic lifestyle changes including dietary interventions, in particular a reduction of saturated fat and cholesterol, are established as a first line therapy to reduce LDL-cholesterol. A change in dietary habits, such as eating fermented products containing lactic acid bacteria, can reduce cholesterol. Since the early studies of Mann and Spoerry [41], the cholesterol-lowering potential of lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium is commonly studied in vitro or in vivo (experimental animals and human subjects) [21,23,36,42-46].

Here, B. longum SPM1207 isolated from healthy Korean feces had hypocholesterolemic effects in vitro and in experimental animals (from 345.0 mg/dl to 262.8 mg/dl, and 111.3 mg/dl to 84.8 mg/dl, respectively). B. longum SPM1207 also slightly increased HDL-cholesterol levels, in agreement with other findings that decreased total cholesterol was accompanied by simultaneous increases of HDL-cholesterol [47,48].

Cholesterol reduction by lactic acid bacteria can be explained by five mechanisms [49-54]: (a) fermentation products of lactic acid bacteria inhibit cholesterol synthesis enzymes and thus reduce cholesterol production; (b) the bacteria facilitate the elimination of cholesterol in feces; (c) the bacteria inhibit the absorption of cholesterol back into the body by binding with cholesterol; (d) the bacteria interfere with the recycling of bile salt (a metabolic product of cholesterol) and facilitate its elimination, which raises the demand for bile salt made from cholesterol and thus results in body cholesterol consumption; and, (e) due to the assimilation of lactic acid.

Lactic acid bacteria have anti-tumor effects [6,8,9,55,56] and block harmful intestinal enzyme activities, a recognized risk factor for colon cancer [8,57,58]. Consumption of L. rhamnosus GG decreased the activity of β-glucuronidase [59,60], nitroreductase [60], and cholylglycine hydrolase [60,61]. Consumption of milk enriched with L. casei for 4 weeks temporarily decreased β-glucuronidase activity in 10 healthy men but not in 10 healthy control subjects [62]. Consumption of milk fermented with a Bifidobacterium species decreased β-glucuronidase activity compared with baseline but did not affect fecal pH or the activity of nitrate reductase, nitroreductase, and azoreductase [63]. Consumption of fermented milk with L. acidophilus, B. bifidum, Streptococcus lactis, and Streptococcus cremoris for 3 weeks decreased nitroreductase activity but not β-glucuronidase and azoreductase [64].

Here, B. longum SPM1207 decreased tryptophanase, urease, β-glucosidase, and β-glucuronidase in rats. Fecal LAB counts in the B. longum SPM1207 feeding group was about 10 times greater than that in the control group, indicating bacterial survival through the gastrointestinal tract.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the incorporation of B. longum SPM1207 in the diet suppressed serum cholesterol levels on a cholesterol-enriched diet. This LAB also improved the balance of the intestinal flora, improved tryptophanase, urease, β-glucosidase, and β-glucuronidase, and increased fecal LAB levels and fecal water content. Therefore, B. longum SPM1207 may be a functional probiotic to treat hypercholesterolemia, help prevent colon cancer, and constipation. Studies in humans, however, could be resulted in contradictory outcomes. So, further clinical trials to confirm these effects must be conducted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

This study was conceived by NJH and designed by NJH, KOL, KSL, and HSS. NJH, KOL, MJC, and JEK were responsible for obtaining funding and sample collection. The in vitro cholesterol-lowering test and animal experiments were done by DKL, SJ, EHB, and MJK. DKL performed data analysis and wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Sahmyook University Research Fund (2008). The authors are grateful to the Seoul Fellowship.

Contributor Information

Do Kyung Lee, Email: 015790@hanmail.net.

Seok Jang, Email: csclub2@hanmail.net.

Eun Hye Baek, Email: eun-hye4444@nate.com.

Mi Jin Kim, Email: sanddalki85@hanmail.net.

Kyung Soon Lee, Email: leeks@syu.ac.kr.

Hea Soon Shin, Email: hsshin@duksung.ac.kr.

Myung Jun Chung, Email: ceo@cellbiotech.com.

Jin Eung Kim, Email: jekim@cellbiotech.com.

Kang Oh Lee, Email: k5lee@syu.ac.kr.

Nam Joo Ha, Email: hanj@syu.ac.kr.

References

- Gilliland SE. Acidophilus milk products: a review of potential benefits to consumers. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:2483–2494. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(89)79389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havenaar R, Huis in't Veld JHJ. Probiotics a general view. In: Wood BJB, editor. The Lactic Acid Bacteria in Health And Disease. Vol. 1. The Lactic Acid Bacteria, Elsevier Applied Science, London; 1992. pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hudault S, Lieven B, Bernet-Camard M-F, Servin AL. Antagonostic activity exerted in vitro and in vivo by Lactiobacillus casei (strain GG) against Salmonella typhimurium C5 infection. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:513–518. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.513-518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen S, Deighton M, Gorbach S. Lactic acid bacteria in health and disease. In: Salminen S, von Wright A, editor. Lactic Acid Bacteria. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York; 1993. pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes CF, Shahani KM, Amer MA. Therapeutic role of dietary lactobacilli and lactobacillus fermented dairy products. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;46:343–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02471.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes CF, Shahani KM. Anticarcinogenic and immunological properties of dietary lactobacilli. J Food Prot. 1990;53:704–710. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.8.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. Probiotics in man and animals. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66:365–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YA, Lee DK, Kim DH, Cho JY, Yang JW, Chung MJ, Kim KJ, Ha NJ. Inhibition of proliferation in colon cancer cell lines and harmful enzyme activity of colon bacteria by Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:468–473. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1180-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DK, Jang S, Kim MJ, Kim JH, Chung MJ, Kim KJ, Ha NJ. Anti-proliferative effects of Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212 extract on human colon cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool-Zobel BL, Bertram B, Knoll M, Lambertz R, Neudecker C, Schillinger U, Schmezer P, Holzapfel WH. Antigenotoxic properties of lactic acid bacteria in vivo in the gastrointestinal tract of rats. Nutr Cancer. 1993;20:271–281. doi: 10.1080/01635589309514295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin M, Suomalainen H, Saxelin M, Isolauri E. Promotion of IgA immune response in patients with Crohn's disease by oral bacteriotherapy with Lactobacillus GG. Ann Nutr Metab . 1996;40:137–145. doi: 10.1159/000177907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikes A, Ferencík M, Jahnová E, Ebringer L, Ciznár I. Hypocholesterolemic and immunostimulatory effects of orally applied Enterococcus faecium M-74 in man. Folia Microbiol (Praha) . 1995;40:639–646. doi: 10.1007/BF02818522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdigon G, Alvarez S, Nader de Macias ME, Roux ME, Pesce de Ruiz Holgado A. The oral administration of lactic acid bacteria increase the mucosal intestinal immunity in response to enteropathogens. J Food Prot. 1990;53:404–410. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.5.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortuero F, Fernandez E, Ruperez P, Moreno M. Raffinose and lactic acid bacteria influence caecal fermentation and serum cholesterol in rats. Nutr Res. 1997;17:41–49. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(96)00231-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CH, Lu TY, Tseng YY, Pan TM. The effects of Lactobacillus-fermented milk on lipid metabolism in hamsters fed on high-cholesterol diet. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71:238–245. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo HL, Loh TC, Law FL, Lim YZ, Kufli CN, Rusul G. Effects of feeding Lactobacillus plantarum I-UL4 isolated from Malaysian tempeh on growth performance, faecal flora and lactic acid bacteria and plasma cholesterol concentrations in postweaning rats. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2003;12:403–408. http://fsnb.or.kr/publication/popup_paper_view.php?no=336 [Google Scholar]

- Grill JP, Cayuela C, Antoine JM, Schneider F. Effects of Lactobacillus amylovorus and Bifidobacterium breve on cholesterol. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2000;31:154–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Whang JY, Whang KY, Oh S, Kim SH. Characterization of the cholesterol-reducing activity in a cell-free supernatant of Lactobacillus acidophius ATCC 43121. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem . 2008;72:1483–1490. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70802. 70802-1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HJ, Kim SY, Lee WK. Isolation of cholesterol-lowering lactic acid bacteria from human intestine for probiotic use. J Vet Sci. 2004;5:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Kim JG, Shin YW, Kim HS, Kim YJ, Chun T, Kim SH, Whang KY. Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus 43121 and a mixture of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium longum on the serum cholesterol level and fecal sterol excretion in hypercholesterolemia-induced pigs. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:595–600. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao JZ, Kondo S, Takahashi N, Miyaji K, Oshida K, Hiramatsu A, Iwatsuki K, Kokubo S, and Hosono A. Effects of milk products fermented by Bifidobacterium longum on blood lipids in rats and healthy adult male volunteers. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:2452–2461. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Toit M, Franz CM, Dicks LM, Schillinger U, Haberer P, Warlies B, Ahrens F, Holzapfel WH. Characterization and selection of probiotic lactobacilli for a preliminary minipig feeding trial and their effect on serum cholesterol levels, faeces pH and faeces moisture content. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;40:93–104. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(98)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland SE, Nelson CR, Maxwell C. Assimilation of cholesterol by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:377–381. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.2.377-381.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuoka T. The human gastrointestinal tract. In: Wood BFB, editor. The Lactic Acid Bacteria In Health and Disease. The Lactic Acid Bacteria, vol. 1, Elsevier Applied Science, London; 1992. pp. 69–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. History and development of probiotics. In: Fuller R, editor. Probiotics-The Scientific Basis. Champman and Hall, London; 1992. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KY, Woodams EE, Hang YD. Probiotication of tomato juice by lactic acid bacteria. J Microbiol. 2004;42:315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue DC, Salminen S. Safety of probiotic bacteria. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 1996;5:25–28. http://apjcn.nhri.org.tw/server/APJCN/Volume5/vol5.1/donohue.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue DC. Safety of probiotics. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15:563–569. http://apjcn.nhri.org.tw/server/APJCN/Volume15/vol15.4/Finished/Donohue.pdf Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardovi V. Genus Bifidobacterium. In: Krieg NR, Holt JG, editor. Bergey's Manual of Systemic Bacteriology. Vol. 2. Williams & Willikins, MD; 1986. pp. 1418–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JB. Isolation and characterization of Bifidobacterium producing exopolysaccharide. Food Eng Prog. 2005;9:291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rudel LL, Morris MD. Determination of cholesterol using o-phthalaldehyde. J Lipid Res. 1973;14:364–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann I, Bergmeyer HU. Urea. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. Vol. 4. Academic Press, New York; 1974. pp. 1791–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kang HJ, Kim SW, Kobayashi K. pH-inducible β-glucuronidase and β-glucosidase of intestinal bacteria. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1992;40:1667–1669. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Lee JH, Bae EA, Han MJ. Induction and inhibition of indole of intestinal bacteria. Arch Pharm Res. 1995;18:351–533. doi: 10.1007/BF02976331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Roh WS, Kim JG. Benefits of fermented milk in rats fed by hypercholesterolemic diet (II) Kor J Food Hyg. 1992;7:123–135. http://ocean.kisti.re.kr/IS_mvpopo213L.do?ResultTotalCNT=12&pageNo=1&pageSize=10&method=view&poid=ksfhs&kojic=SPOHBV&sVnc=v7n2&id=2&setId=36430&iTableId=4&iDocId=186290&sFree. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JW, Gilliland SE. Effect of fermented milk (yogurt) containing Lactobacillus acidophilus L1 on serum cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic humans. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18:43–50. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law MR, Wald NJ, Wu T, Hackshaw A, Bailey A. Systematic underestimation of association between serum cholesterol concentration and ischaemic heart disease in observational studies: data from the BUPA study. BMJ . 1994;308:363–366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW. Effect of fermented milk on the blood cholesterol level of Korean. J Fd Hyg Safety. 1997;12:83–95. http://ocean.kisti.re.kr/IS_mvpopo213L.do?ResultTotalCNT=12&pageNo=1&pageSize=10&method=view&poid=ksfhs&kojic=SPOHBV&sVnc=v12n1&id=0&setId=77327&iTableId=4&iDocId=216346&sFree. [Google Scholar]

- Frick M, Elo O, Haapa K. Helsinki heart study: primary prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-age men with dyslipemia. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann GV, Spoerry A. Studies of a surfactant and cholesterolemia in the Massai. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27:464–469. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/27.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison VC, Peat G. Serum cholesterol and bowel flora in the newborn. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:1351–1355. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner G, Fried R, Jeor S, Fusetti St L, Morin R. Hypocholesterolemic effect of yogurt and milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:19–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver FAM, Meer R Van der. The assumed assimilation of cholesterol by Lactobacilli and Bifidobacterium bifidum is due to their bile salt-deconjugating activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1120–1124. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1120-1124.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann GV. A factor in yogurt which lowers cholesteremia in man. Atherosclerosis. 1977;26:335–340. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(77)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahri K, Grill JP, Schneider F. Bifidobacteria strain behavior toward cholesterol: coprecipitation with bile salts and assimilation. Curr Microbiol. 1996;33:187–193. doi: 10.1007/s002849900098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Yamazaki K, He F, Kawase M, Hosoda M, Hosono A. Hypocholesterolemic effects of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei TMC 0409 strain observed in the rats fed cholesterol contained diets. Anim Sci J. 1999;72:90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Taranto MP, Medici M, Perdigon G, Ruiz Holgado AP, Valdez GF. Evidence for hypocholesterolemic effect of Lactobacillus reuteri in hypercholesterolemic mice. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:2336–2340. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)70123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beena A, Prasad V. Effect of yogurt and bifidus yogurt fortified with skim milk powder, condensed whey and lactosehydrolysed condensed whey on serum cholesterol and triacylglycerol levels in rats. J Dairy Res. 1997;64:453–457. doi: 10.1017/S0022029997002252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima M, Nakao M. The effect of a probiotic on faecal and liver lipid classes in rats. Br J Nutr. 1995;73:701–710. doi: 10.1079/BJN19950074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald KK. Serum cholesterol levels in rats fed skim milk fermented by Lactobacillus acidophilus. J Food Sci. 1982;47:2078–2079. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb12955.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Yamazaki K, Arai Y, Kawase M, He F, Hosoda M, Hosono A. Effect of lactic acid bacteria on serum cholesterol level in rats fed cholesterol diet. Anim Sci Technol. 1998;69:702–707. [Google Scholar]

- Rao DR, Chawan CB, Pulusani SR. Influence of milk and Thermophilus milk on plasma cholesterol levels and hepatic cholesterogenesis in rats. J Food Sci. 1981;46:1339–1341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1981.tb04168.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kaizu H, Yamauchi Y. Effect of cultured milk on serum cholesterol concentrations in rats which fed highcholesterol diets. Animal Sci Technol. 1991;62:565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin BR, Gorbach SL. Effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus dietary supplements in 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine dihydrochloride-induced intestinal cancer in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:263–265. doi: 10.1093/jnci/64.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin BR, Gualtieri LJ, Moore RP. The effect of Lactobacillus GG on the initiation and promotion of DMH-induced intestinal tumors in the rat. Nutr Cancer. 1996;25:197–204. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BS, Wynder E. Metabolic epidemiology of colorectal cancer: fecal bile acids and neutral steroids in colon cancer patients with adenomatous polyps. Cancer. 1997;39:2533–2539. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197706)39:6<2533::AID-CNCR2820390634>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RT. Toxicological implications of biotransformation by intestinal microflora. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1972;23:769–781. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(72)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin BR, Gorbach SL, Saxelin M, Barakat S, Gualtiere L, Salminen S. Survival of Lactobacillus species (strain GG) in human gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01308354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling WH, Korpela R, Mykkanen H, Salminen S, Hanninen O. Lactobacillus strain GG supplementation decreases colonic hydrolytic and reductive enzyme activities in healthy female adults. J Nutr. 1994;124:18–23. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling WH, Hänningen O, Mykkänen H, Heikura M, Salminen S, von Wright A. Colonization and fecal enzyme activities after oral Lactobacillus GG administration in elderly nursing home residents. Ann Nutr Met. 1992;36:162–166. doi: 10.1159/000177712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanhaak S, Havenaar R, Schaafsma G. The effect of consumption of milk fermented by Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the intestinal microflora and immune parameters in humans. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhnik Y, Flourié B, Andrieux C, Bisetti N, Briet F, Rambaud J-C. Effects of Bifidobacterium sp fermented milk ingested with or without inulin on colonic bifidobacteria and enzymatic activities in healthy humans. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau P, Pochart P, Flourié B, Pellier P, Santos L, Desjeux JF, Rambaud JC. Effect of chronic ingestion of a fermented dairy product containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum on metabolic activities of the colonic microflora. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:685–688. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]