Abstract

Objectives. We used 37 years of follow-up data from a randomized controlled trial to explore the linkage between an early educational intervention and adult health.

Methods. We analyzed data from the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program (PPP), an early school-based intervention in which 123 children were randomized to a prekindergarten education group or a control group. In addition to exploring the effects of the program on health behavioral risk factors and health outcomes, we examined the extent to which educational attainment, income, family environment, and health insurance access mediated the relationship between randomization to PPP and behavioral and health outcomes.

Results. The PPP led to improvements in educational attainment, health insurance, income, and family environment Improvements in these domains, in turn, lead to improvements in an array of behavioral risk factors and health (P = .01). However, despite these reductions in behavioral risk factors, participants did not exhibit any overall improvement in physical health outcomes by the age of 40 years.

Conclusions. Early education reduces health behavioral risk factors by enhancing educational attainment, health insurance coverage, income, and family environments. Further follow-up will be needed to determine the long-term health effects of PPP.

Prekindergarten programs provide a secure environment in which children are cognitively enriched, typically via a curriculum that enhances math and linguistic skills. The prekindergarten years (approximately 3 to 4 years of age) are thought to be a critical window for children's intellectual and socioemotional development.1–4 Prekindergarten programs may be especially important for children with parents with a limited amount of education, who may not be able to provide as rich a learning environment as that available to children whose parents are better educated.3

Prekindergarten programs targeting children from low-income households have been shown to produce lifelong improvements in schooling, income, family stability, and job quality.5–16 These intertwined improvements in social circumstances may in turn improve health through reductions in behavioral risk factors, enhanced job safety, better health insurance coverage, safer neighborhoods of residence, better access to healthy foods, and lower levels of psychological stress.7,9,16–20

Nonetheless, the long-term causal linkage between education and health and the pathways through which education affects health have not previously been established in a randomized controlled trial. We investigated whether the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program (PPP) randomized controlled trial improved adult health outcomes and health behavioral risk factors and explored how these outcomes were mediated.

METHODS

In PPP, which was initiated in 1962, 123 preschool-aged (3 or 4 years) African American children were randomized to receive no intervention or to receive a 2-year program of 2.5 hours of interactive academic instruction daily coupled with 1.5-hour weekly home visits.21 All teachers had a master's degree and had completed training in child development. Children were recruited from low-income, predominantly African American neighborhoods in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Randomization

Children eligible for PPP were identified via census data, referrals from neighborhood groups, and door-to-door canvassing. To be included, children were required to be of low socioeconomic status (based on an index score, described by Schweinhart et al.,21 derived from parental income, education, and occupation) and to have an IQ test score (Stanford-Binet) between 70 and 85; children with any diagnosed physical handicap were excluded.

As a result of the small sample size, students were matched according to IQ, socioeconomic status, and gender before group randomization. One student in each pair was then randomized to the PPP condition or the control condition via a coin toss. Siblings were automatically entered into the same group to ensure that the intervention effect was isolated within families.

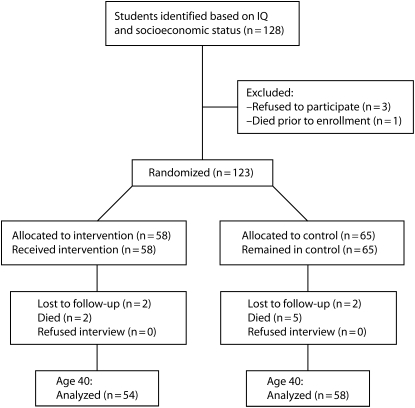

It was not possible to blind researchers or participants during the process of allocating participants to the experimental or control group. However, researchers were blinded to the collection of all follow-up data. Fifty-eight students were randomized to the intervention group, and 65 were randomized to the control group (Figure 1).21 After the study began, 8 children with working mothers were removed from the experimental group and replaced with 8 children with nonworking mothers from the control group. This was done because children with working mothers were unable to participate in the PPP home visit component.

FIGURE 1.

Randomization flow diagram of participants in the High/Scope Perry Preschool Program.

Note. Eight students were swapped between the experimental and control groups.

Children were initially followed between the ages of 3 and 4 years and then continuously followed through the age of 40 years. Of the 123 original respondents, 4 could not be located for the age 40 survey (2 in the intervention group and 2 in the control group) and 7 had died (2 in the PPP intervention group and 5 in the control group). Face-to-face interviews conducted when the participants were aged 27 and 40 years were used to collect data on a range of health outcomes and behavioral risk factors. However, because new questions were added at the age 40 interview, data on some outcomes were not available for both interviews (unless otherwise indicated, the outcomes described here represent those assessed when participants were aged 40 years).

Statistical Analyses

Because 8 students with working mothers were exchanged between groups, children in the PPP and control groups differed according to maternal employment status. Thus, to reduce the bias caused by between-group differences in our variables of interest, we controlled for all predetermined covariates: participant gender and IQ; indicators for father's presence in the home and type of employment (skilled or semiskilled); mother's educational level, age, and employment status; and participant age at the midlife interview (given that age is an important determinant of health). We calculated P values for mean differences in outcome variables both before and after control for these covariates. Participants with missing data on any of the covariates were dropped from all analyses.

To overcome concerns associated with the small sample size, we examined the impact of PPP on broadly defined health categories (behavioral risk factors and health outcomes) by combining estimated effects from single response models. Behavioral risk factors were included as a primary outcome of interest because they are well-established determinants of long-term health. We examined health outcomes because we wanted to determine the extent to which we could make conclusions regarding the long-term effects of PPP on health (i.e., through the age of 40 years). We selected dependent variables according to whether they fit into the behavioral risk factor category or the health outcomes category.

We explored the impact of PPP on subcategories within these broader categories of behavioral risk factors and health outcomes as well. For the health outcomes category, these subcategories included measures of overall health status, medical conditions, and hospitalizations (tertiary care use). Overall health status was assessed as a combination of 3 binary variables: excellent or very good self-rated health, stopping work as a result of poor health, and death. Medical conditions included binary indicators of self-reported conditions (participants were asked whether they had been medically diagnosed with arthritis, asthma, diabetes, or high blood pressure and whether they had subjective joint pain) and indicator variables for obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) and overweight (body mass index = 25–29 kg/m2), both based on self-reported height and weight. The tertiary care use subcategory comprised binary indicators for hospitalization in the preceding 12 months at age 40 years, and use of urgent care services in the preceding 12 months at age 40 years. Self-reported joint pain was the only condition for which a medical diagnosis was not required. Thus, we conducted analyses that both included and did not include this variable.

In terms of behavioral risk factor subcategories, we examined use of preventive medical care, traffic safety practices, and drug use. Use of preventive medical care services was assessed by binary indicators for a routine physician visit in the preceding 12 months at age 27 years, a routine physician visit in the preceding 12 months at age 40 years, a routine dental visit in the preceding 12 months, and a routine eye doctor visit in the preceding 12 months. Traffic safety practices were measured as binary indicators for seat belt use at age 27 years (typical or higher levels of use, compared with sometimes or no use), seat belt use at age 40 years, traffic tickets in the preceding 15 years (excluding parking tickets) at age 27 years, and traffic tickets in the preceding 15 years at age 40 years. Finally, binary indicators for current tobacco use (vs no history of use), daily alcohol use (≤ 2 drinks vs > 2 drinks per day), and illicit use of prescription sedatives, marijuana, cocaine, and heroin in the past 15 years at age 40 were employed to assess drug use.

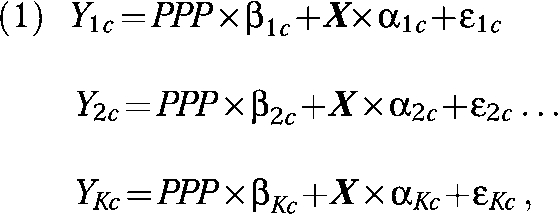

To compute effects for the categories (e.g., behavioral risk factors) and subcategories (e.g., drug use) just described, we averaged estimates obtained from single equation linear regression models. Estimates were obtained via the following equation:

|

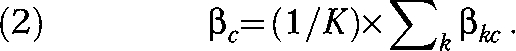

where Y is a single response in category c, with a total of K responses in that category; PPP is a treatment indicator; and X is a vector of covariates. The treatment effect for outcome category c is

|

We computed estimates for each of the health categories and subcategories just defined. To allow us to summarize across single responses within a given category, we coded all single responses in the same direction so that a positive βc value reflected a beneficial impact of PPP.

This testing approach enabled us to detect whether effects were generally beneficial (or detrimental) over a single health category with multiple endpoints.22,23 This approach is superior to an F test of the joint significance of multiple endpoints, which is nondirectional and has less power. To compute the variance of βc, we estimated equation 1 simultaneously (via seemingly unrelated regression) to obtain the covariance matrix of the single estimates and thus compute the standard error of the average impact.23 This strategy provided information on whether differences between groupings were statistically significant but did not lend itself to meaningful summary measures. In addition, we examined whether there were meaningful differences between results derived from linear and logistic models and found none.

Finally, as mentioned, 8 children with working mothers were transferred between groups. Thus, we estimated models with and without conditioning on maternal employment, allowing us to determine with certainty whether this breach of the randomization protocol affected our overall findings with respect to behavioral and health outcomes.

Mediating Variables

PPP has been shown to enhance lifetime educational attainment, income, the probability of having health insurance coverage, and the family environments of adults who underwent the intervention as children.21 Given their potential role as mediators, we explored the extent to which these 4 factors influenced the health-producing effects of PPP. We did so by separately including these factors in equation 1 and recomputing βc for each category (after dropping missing values for mediators). The resulting percentage change in βc provided an estimate of the extent to which each factor mediated the relationship between early education and adult health.

The educational attainment factor included dummy variables for participants who had earned a general equivalency diploma, high school graduates, and those who had completed some college by the age of 40 years. The family environment factor included dummy variables for marital status and number of children. The income factor included dummy variables for monthly and annual earning quartiles. Finally, the health insurance factor included dummy variables for private or public insurance coverage and whether the participant lacked health insurance coverage at any point during the preceding 15 years during the age 40 follow-up. We did not include death as an outcome variable because mediator variables were not available for this category.

RESULTS

Data on the basic demographic characteristics of the intervention and control groups are shown in Table 1. Participants in the control group were significantly more likely than participants in the intervention group to come from families with working mothers (as opposed to mothers who were unemployed or on welfare). There was a trend among intervention group participants toward having fathers who were working in a semiskilled or skilled occupation on program entry (P = .08). Otherwise, no statistically significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of participants randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups were noted. The differences that arose were the result of 8 children with working mothers being replaced in the intervention group after randomization by 8 children with nonworking mothers.

TABLE 1.

Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics, Overall and by Study Group: High/Scope Perry Preschool Program, Ypsilanti, MI, 1962–2000

| Overall, Mean | Treatment Group, Mean | Control Group, Mean | P | |

| Age at midlife interview, y | 40.8 | 40.8 | 40.8 | .80 |

| Program entry characteristics | ||||

| Mother's age, y | 29.1 | 29.6 | 28.7 | .45 |

| Proportion male | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | .73 |

| IQ score | 79.0 | 79.6 | 78.5 | .38 |

| Proportion with father at home | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | .63 |

| Mother's education, y | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.4 | .84 |

| Proportion with working mother | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | .002 |

| Proportion with father in skilled occupationa | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | .08 |

Note. Data were derived from Schweinhart et al.21

The proportion of participants whose father held a skilled or semiskilled job at the time of assignment to the Perry Preschool Program or to the control group.

Analyses Adjusted for Covariates

Table 2 presents mean values for the various health outcome and health behavior measures. After control for random differences in group allocation, participants randomized to PPP scored significantly higher than did control group participants on the composite measure of health status (P < .05). This difference was driven by the intervention group's lower mortality rates and by the tendency for that group's members to be less likely to stop working as a result of poor health. Seven deaths were recorded in the sample as a whole. In the PPP group 1 participant died of HIV/AIDS and 1 died of cancer, and in the control group 1 participant died of cancer and 4 were the victims of suspected murders (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Coefficients for Health Outcomes and Preventive Health Behaviors by Category and Subcategory: High/Scope Perry Preschool Program, Ypsilanti, MI, 1962–2000

| Treatment Group, Meana | Control Group, Meana | Difference | P | Adjusted Differenceb | Adjusted P | No. of Observationsc | |

| Health outcomes | |||||||

| Overall health status | |||||||

| Self-reported healthd | 0.39 | 0.41 | −0.03 | .79 | −0.09 | .39 | 112 |

| Stopped working | 0.43 | 0.55 | −0.13 | .19 | −0.19 | .07 | 112 |

| Deceased | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.04 | .31 | −0.08 | .06 | 123 |

| Category difference | … | … | −0.06 | .19 | −0.12 | .01 | … |

| Health conditions | |||||||

| Arthritis | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.06 | .39 | 0.03 | .72 | 110 |

| Joint pain | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.25 | .01 | 0.20 | .05 | 110 |

| Asthma | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | .69 | 0.05 | .50 | 111 |

| Diabetes | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.04 | .37 | 0.04 | .41 | 109 |

| Hypertension | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.10 | .25 | 0.15 | .12 | 110 |

| Obesity | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.00 | .98 | −0.01 | .94 | 103 |

| Overweight | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.04 | .67 | 0.11 | .30 | 103 |

| Category difference | … | … | 0.07 | .05 | 0.08 | .04 | … |

| Tertiary care use | |||||||

| Hospitalizationse | 0.26 | 0.44 | −0.18 | .42 | −0.23 | .36 | 111 |

| Urgent care use | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.01 | .88 | 0.04 | .65 | 111 |

| Category difference | … | … | −0.08 | .49 | −0.10 | .47 | … |

| Health outcome mean | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.01 | .71 | 0.00 | .96 | … |

| Health behaviors | |||||||

| Preventive medical care | |||||||

| No physician visit at age 27 y | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.04 | .64 | 0.02 | .87 | 115 |

| No physician visit at age 40 y | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.06 | .35 | 0.07 | .32 | 111 |

| No dental visit | 0.24 | 0.37 | −0.13 | .15 | −0.12 | .22 | 111 |

| No eye doctor visit | 0.51 | 0.63 | −0.12 | .20 | −0.17 | .10 | 110 |

| Category difference | … | … | −0.04 | .48 | −0.05 | .36 | … |

| Traffic safety | |||||||

| No seat belt use at age 27 y | 0.43 | 0.66 | −0.23 | .01 | −0.25 | .02 | 115 |

| No seat belt use at age 40 y | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.03 | .62 | −0.03 | .68 | 110 |

| Traffic tickets at age 27 y | 0.33 | 0.37 | −0.04 | .66 | −0.13 | .19 | 115 |

| Traffic tickets at age 40 y | 0.52 | 0.68 | −0.16 | .09 | −0.15 | .14 | 110 |

| Category difference | … | … | −0.12 | .00 | −0.14 | .00 | … |

| Drug use | |||||||

| Tobacco use | 0.42 | 0.55 | −0.14 | .15 | −0.14 | .18 | 111 |

| Alcohol use | 0.75 | 0.88 | −0.12 | .10 | −0.13 | .10 | 110 |

| Sedative use | 0.23 | 0.32 | −0.09 | .30 | −0.10 | .30 | 110 |

| Marijuana use | 0.45 | 0.54 | −0.09 | .35 | −0.10 | .32 | 110 |

| Cocaine use | 0.23 | 0.29 | −0.06 | .48 | −0.06 | .51 | 109 |

| LSD use | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.03 | .46 | −0.04 | .41 | 110 |

| Heroin use | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.09 | .03 | −0.07 | .08 | 110 |

| Category difference | … | … | −0.05 | .18 | −0.05 | .19 | … |

| Health behavior mean | 0.31 | 0.39 | −0.07 | .02 | −0.08 | .01 | … |

Note. Discrepancies in values are due to rounding. Ellipses indicate that no data were available. Seemingly unrelated regression was used to calculate the category difference of all preceding variables within a category.

Proportion of participants self-reporting the outcome of interest.

Adjusted for age at midlife interview; gender; IQ at program entry; mother's education, age, and employment status at program entry; father's presence in home at program entry; and an indicator for father's occupation (skilled or semiskilled) at program entry.

Range = 103–123, depending on whether dependent variable data are missing.

Participants reporting good, fair, or poor health.

In the past year at age 40 years.

Participants in the intervention group were significantly more likely than were control group participants to have a medical condition (P < .05). However, when subjective joint pain (not medically diagnosed) was removed from the analyses, there was no statistically significant difference for the medical conditions category as a whole (P = .12). There were few between-group differences in tertiary care use.

Participants in the PPP group were significantly less likely than those in the control group to engage in risky health behaviors (P < .01; Table 2). For example, they scored higher on traffic safety practices (P < .001), primarily because of their greater use of seat belts at the age of 27 years (P < .05). Although PPP group participants reported fewer physician visits but more dental and eye care visits, rates of preventive medical care use were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Rates of smoking and use of sedatives, marijuana, LSD, cocaine, and heroin were lower among participants in the PPP condition, but alcohol use rates were higher. When these differences were analyzed separately, none were statistically significant.

Mediators

Overall, participants randomized to the PPP condition completed more education and had better family environments, higher incomes, and better quality health insurance coverage than participants in the control group. Table 3 shows the extent to which each of these factors mediated changes in health outcomes and health risk behaviors among participants in the PPP group. Because overall results for the health outcomes category were not significant, we discuss mediators only with respect to behavioral risk factors.

TABLE 3.

Mediation Coefficients for Education, Family Environment, Income, Health Insurance, and All Factors Combined: High/Scope Perry Preschool Program, Ypsilanti, MI, 1962–2000

| Baseline | Education | Family Environment | Income | Insurance | All | |

| Health outcomes | ||||||

| Overall | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Health status | −0.14 | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.13 |

| Medical conditions | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Tertiary care use | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.04 |

| Health behaviors | ||||||

| Overall | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.04 |

| Traffic safety | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.12 |

| Preventative care | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| Drug use | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

Note. Coefficients were adjusted for age at midlife interview; gender; IQ at program entry; mother's education, age, and employment status at program entry; father's presence in home at program entry; and an indicator for father's occupation (skilled or semiskilled) at program entry.

None of the potential mediators we studied clearly emerged as a consistent explanatory variable in regard to traffic safety or drug use. However, educational attainment (B = 0.02, or 63% of the total) and health insurance coverage (B = 0.03, or 46% of the total) explained nearly all of the variation in use of preventive care services (percentages do not sum to 100% because of imprecision in the analysis). The mediators in combination explained roughly half of the observed variation in overall preventive health behaviors.

Robustness Tests

When analyses were limited to participants for whom data on all measures were available, the results were not substantively different from the results of the earlier analyses (and this was true of the data presented in both Table 2 and Table 3). In analyses conditioned on maternal employment, differences in overall health outcomes between the PPP and control groups remained nonsignificant (P = .84). Differences in health status measures remained significant (P = .01), but there were no differences in medical conditions between groups (P = .08), even when subjective joint pain was included. Overall differences in health behaviors between the groups remained significant (P = .01), led by improved traffic safety practices (P = .005) and reduced drug use (P = .09) in the PPP group.

DISCUSSION

Participants initially randomized to the PPP intervention were more likely than those randomized to the control group to complete more schooling, to have a stable family environment, to be insured, and to have higher earnings.21 We hypothesized that these social benefits would translate into improvements in health-promoting behaviors, which should in turn translate into lower rates of such health conditions as diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and arthritis. This reduced frequency of health conditions should then translate into improved overall health status and reduced mortality. As the participants age, we would expect such differences to become more pronounced.

We found that the effects of PPP on educational attainment, stable family environments, health insurance coverage, and earnings had indeed led to improvements in participants’ health behaviors by the time they reached 40 years of age. For instance, our results showed that use of preventive health care services was almost entirely driven by the effects of PPP on health insurance coverage and educational attainment. The effects of the other mediators explained about half of the variation in behavioral risk factors. No other clear predictive patterns emerged.

Although 40 years of age is early for health outcomes to materialize, we nonetheless found statistically significant improvements in the health status of experimental group participants. However, the observed differences in rates of self-reported medical conditions were in the opposite direction of that expected; participants in the PPP group, despite their better risk profile and health status, reported more medical conditions than did participants in the control group. Although these differences were not significant in all of our analyses, they negated any benefits of PPP on overall health outcomes.

The higher prevalence of medical conditions among participants in the PPP group was not explained by between-group differences in health insurance coverage. Although participants randomized to the PPP condition were more likely than those in the control condition to have employer-sponsored coverage (65% vs 45%) and were less likely to depend on prison-based health care (6% vs 14%) or Medicaid or Medicare (9% vs 17%) coverage, adjusting for coverage did not substantively alter our findings.

Limitations

Four important limitations of our design should be noted. First, our approach of calculating averages within broader categories of outcomes resulted in all outcomes within a group being of equal weight, and some outcomes may be more important than others (e.g., mortality is more important than days of work missed as a result of illness as a measure of overall health status). Likewise, categories take on differing levels of importance; self-reported conditions, for instance, are less important than overall measures of health status. We are unaware of an objective measure for appropriately weighting these outcomes.

Second, because PPP's effects on future educational attainment were powerful, participants assigned to the intervention group may have interpreted the meaning of complex survey questions differently than those assigned to the control group. However, questions were formulated by survey professionals and administered by a highly trained interviewer. Thus, rather than eliminating questions that may have been difficult to interpret (e.g., prevalence of medical conditions), we decided to include all questions so that we could increase the statistical power of our study. Inclusion of medical examination data as well as biomarkers of health (e.g., serum cholesterol and C-reactive protein samples) in future surveys of the PPP participants would allow better determination of the health of that group.24

Third, our results may not generalize well to higher income, nonminority populations, given evidence suggesting that educational interventions have more of an impact on disadvantaged populations than on more advantaged groups.25 Finally, statistically significant between-group variance in maternal employment occurred despite randomization. For this reason, we controlled for random variation in familial sociodemographic characteristics. When the analyses were conditioned on maternal employment, the results were similar or slightly enhanced, suggesting that our findings were not confounded.

Conclusions

With the exception of the higher prevalence of self-reported conditions among the members of the PPP group, our findings are consistent with those of nonrandomized studies in which high levels of educational attainment have been shown to directly improve health status.7,9,16,26 Other studies have demonstrated that increases in educational attainment lead to higher incomes, increases in rates of health insurance coverage, and reductions in divorce rates.11–14,27–29

Some have questioned whether education leads to reductions in behavioral risk factors, arguing that most people are aware that risky behaviors are bad for their health30 and that higher educational attainment as well as better health can be attributed to studies’ omission of confounding factors (e.g., higher genetic potential or more forward-looking behaviors).31,32 Our findings suggest that such theories are incorrect.

PPP was a high-quality early childhood intervention targeted toward disadvantaged children with an IQ ranging from 70 to 85. The structural problems faced by these children were stark, probably explaining their low IQ scores.33 Despite these structural problems, PPP produced dramatic reductions in crime and poverty rates.5,21 Crime is a public health problem for which we did not account in our study. Criminal activity involves risk-taking behaviors that can be life threatening, imprisonment has been linked to shortened life expectancy,34 and crime leads to psychological trauma, injury, or death among the perpetrator's victims. All of these factors suggest that PPP's health benefits extend beyond the outcomes measured here.

Given that behavioral risk factors are strong determinants of health in later life, it is likely that the large reductions in such risk factors observed here will ultimately translate into improved health outcomes in this cohort. Our findings therefore suggest that prekindergarten programs hold promise as public health interventions. However, the members of the PPP cohort have not yet reached the age at which heart disease, cancer, and stroke begin to shape morbidity and mortality, so more time will be needed for definitive results on physical health outcomes arising from this novel educational intervention.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study.

References

- 1.Knudsen EI, Heckman JJ, Cameron JL, Shonkoff JP. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America's future workforce. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:10155–10162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble KG, McCandliss BD, Farah MJ. Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Dev Sci 2007;10:464–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gormley W, Gayer T, Phillips D, Dawson B. The effects of universal pre-K on cognitive development. Dev Psychol 2005;41:872–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belfield CR, Nores M, Barnett WS, Schweinhart L. The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program: Cost-benefit analysis using data from the age-40 followup. J Hum Resour 2006;41:162–190 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutler D, Lleras-Muney A. Education and health: evaluating theories and evidence. Available at: http://www.npc.umich.edu/news/events/healtheffects_agenda/cutler.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2009

- 7.Lleras-Muney A. The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States. Rev Econ Stud 2005;72:189–221 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glied S, Lleras-Muney A. Health Education, Inequality, and Medical Innovation. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muennig P. How education produces health: a hypothetical framework. Teach Coll Rec Available at: http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentID=14606. Published online September 12, 2007. Accessed March 5, 2009

- 10.Grossman M. Education and Nonmarket Outcomes. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carniero P. Heckman J. Human capital policy. In: Heckman J, Krueger A, eds Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2003:77–240 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levin H, Belfield C, Muennig P, Rouse C. The Price We Pay: Economic and Social Consequences of Inadequate Education. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner J, Oswald A. How is mortality affected by money, marriage, and stress? J Health Econ 2004;23:1181–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull 2001;127:472–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haan M, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health: prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol 1987;125:989–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross CE, Wu CL. The links between education and health. Am Sociol Rev 1995;60:719–745 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muennig P, Fahs M. The cost-effectiveness of public postsecondary education subsidies. Prev Med 2001;32:156–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie J, Thomas D. Does Head Start make a difference? Am Econ Rev 1995;85:341–364 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig J, Miller DL. Does Head Start improve children's life chances? Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Q J Econ 2007;122:159–208 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muennig P, Woolf SH. Health and economic benefits of reducing the number of students per classroom in US primary schools. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2020–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweinhart LJ, Montie J, Xiang Z, Barnett WS, Belfield C, Nores M. The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien PC. Procedures for comparing samples with multiple endpoints. Biometrics 1984;40:1079–1087 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica 2007;75:83–119 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muennig P, Sohler N, Mahato B. Socioeconomic status as an independent predictor of physiological biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: evidence from NHANES. Prev Med 2007;45:35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finn JD, Gerber SB, Boyd-Zaharias J. Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school. J Educ Psychol 2005;97:214–223 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossman M. Effects of education on health. In: Behrman JR, Stacey N, eds The Social Benefits of Education. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1997:69–124 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: pathways to health. Physiol Behav 2003;79:409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muennig P, Franks P, Jia H, Lubetkin E, Gold MR. The income-associated burden of disease in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:2018–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Refining the association between education and health: the effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography 1999;36:445–460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mechanic D. Disadvantage, inequality, and social policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottfredson LS. Intelligence: is it the epidemiologists’ elusive “fundamental cause” of social class inequalities in health? J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;86:174–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs V. Reflections on the socio-economic correlates of health. J Health Econ 2004;23:653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychol Sci 2003;14:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golembeski C, Fullilove R. Criminal (in)justice in the city and its associated health consequences. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1701–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]