Abstract

Purpose

The objective is to estimate the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of Painful Bladder Syndrome (PBS) defined as pain increasing as the bladder fills and/or pain relieved by urination for at least three months and its association with socio-demographics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status), lifestyle (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity) and psychosocial variables (sexual, physical, emotional abuse experienced as a child or as an adult, worry, trouble paying for basics, depression).

Materials and Methods

The data used come from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey, an epidemiologic study of 5506 randomly selected adults aged 30-79 of three race/ethnic groups (Black, Hispanic, White).

Results

The overall prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS is two percent (1.3% in men and 2.6% in women) with increased prevalence in middle aged adults and those of lower socioeconomic status. Symptoms suggestive of PBS are more common in those who have experienced abuse, in those who are worried about someone close to them, and in those who are having trouble paying for basics. This pattern holds even after adjusting for depression.

Conclusions

PBS is associated with a number of lifestyle and psychosocial correlates. This suggests that the management of patients with PBS (physical symptoms) may benefit from a multi-faceted approach of combining medical and psychological, and cognitive treatment.

Keywords: painful bladder syndrome, abuse, worry, socioeconomic status, urologic symptoms

Introduction

Painful bladder syndrome (PBS) can be a chronic and debilitating disease, characterized by urinary urgency, frequency and bladder pain 1, 2. Recent studies using symptom-based diagnostic criteria for PBS instead of anatomically-based diagnostic criteria for IC suggest that the prevalence of this symptom complex may be higher than previously thought 3. Using symptom-based criteria may help to identify individuals in earlier disease stages, and to avoid the complication of the variety of diagnostic criteria used by individual physicians to diagnose IC 4.

Research using symptom-based diagnostic criteria suggests that painful bladder syndrome is more common in women and middle aged people 5, 6. Gender disparities, once thought to be dramatic 7, have diminished in recent studies 5. Other data suggest that individuals with painful bladder syndrome are more prone to depression 8 and panic disorder 9.

The objective of this study is to describe the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS, its variation by demographic factors, and its association with a variety of psychosocial and lifestyle variables.

Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey is a community-based epidemiologic survey of urologic symptoms and risk factors conducted from 2002-2005. BACH is a cross-sectional random sample of community-dwelling adults, not a sample of conveniently available patients. Detailed methods are given elsewhere 10. In brief, BACH used a multi-stage stratified cluster sample to recruit 5506 adults aged 30-79 years in three racial/ethnic groups from the city of Boston (2301 men, 3205 women; 1770 Black, 1877 Hispanic, 1859 White). Information about urologic symptoms, co-morbidities, lifestyle, anthropometrics, and psychosocial attributes was collected via an interviewer administered questionnaire. Respondents used a self-administered questionnaire to answer questions about sexual function and abuse. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board of New England Research Institutes.

We have previously reported the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS by several definitions 6. We consider the following as our operational definition of PBS: pain increasing as bladder fills (fairly often, usually, or almost always) and/or pain relieved by urination (fairly often, usually, or almost always) lasting for at least three months. The primary reason for this definition is that pain is considered to be the cardinal symptom of PBS 11. This definition is somewhat broader than but consistent with the International Continence Society (ICS) definition of PBS as “suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and night-time frequency, in the absence of proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology” 1. It is also slightly broader but consistent with than the European Association for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) for the new nomenclature “bladder pain syndrome” (BPS): “BPS is a clinical diagnosis made on the basis of chronic pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort perceived to be related to the urinary bladder and accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom such as persistent urge to void or frequency” 2. The ICS definition is known to miss some people with its restriction to bladder filling and suprapubic location 12. Our operational definition was designed to capture as many respondents as possible while excluding those without the cardinal symptom of pain.

Frequency was considered to be present if respondents reported urinating more frequently than every two hours or had frequent urination during the day (fairly often, usually, or almost always), or those who reported urinating eight or more times per day. Urgency was considered to be present if respondents reported having difficulty postponing urination or had a strong urge to urinate (fairly often, usually, or almost always) in the last month, or those who experienced a strong urge to urinate in the last seven days (four or more times). Nocturia was considered to be present if the respondent got up to urinate more than once at night (fairly often, usually, or almost always) or reported two or more urinations at night after falling asleep. Urologic symptoms were assessed over the previous month. The sources of the questions are given in 13.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was defined as a combination of education and income 14 and was categorized such that ¼ of the BACH population is lower, ½ middle, and ¼ upper. Health insurance status was categorized as (some) private, public only (Medicare and/or Medicaid), or none. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from interviewer measured height and weight (kg/m2) and was categorized as normal (<25), overweight (25-30), or obese (≥30). Smoking status was categorized as never, former, or current smoker. Alcohol consumption over the last 30 days was measured using questions from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) and categorized as 0, <1, 1-3, and 3+ drinks per day. Physical activity was measured by a validated scale 15, and categorized as low, moderate, and high. Having a job with some walking would put someone into the moderate category. In addition, if the respondent got at least 1 hour per day of moderate activities, did light and heavy housework, did outdoor yard work, and took care of someone, they would be in the high category. Three types of abuse (sexual, physical, and emotional) were assessed over two life stages (childhood [age 13 or younger], adolescence/adulthood [age 14 or older]) using a validated instrument 16. Within each life stage, we created a variable for 0 – 3 types of abuse. A variable called trouble paying for basics was created if the respondent reported trouble paying for food, housing, transportation, or health or medical care. A respondent was said to be depressed if they had at least five of eight symptoms on an abridged Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale 17.

Statistical analyses were done overall and by gender. Bivariate associations of symptoms suggestive of PBS and categorical covariates were assessed using a chi-square test of association. Logistic regression was used for multivariate models. Parsimonious models were determined using backward elimination while keeping covariates that were significant (p < 0.05) overall or in one gender. The questions on abuse in the self-administered questionnaire were most likely to have missing data (10% in Blacks, 15% in Hispanics, and 6% in Whites). Missing data were replaced by plausible values using multiple imputation. To be representative of the city of Boston, observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection. Weights were then post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 U.S. Census. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1.3 of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and 9.0.1 of SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the complex sampling design.

Results

Basic demographic and other characteristics are given for BACH participants by gender (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and selected characteristics of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) sample (percent)

| Overall | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 30-39 | 35.2 | 37.2 | 33.5 |

| 40-49 | 25.1 | 25.8 | 24.4 |

| 50-59 | 18.1 | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| 60-69 | 13.3 | 11.3 | 15.1 |

| 70-79 | 8.2 | 7.8 | 8.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 27.6 | 25.0 | 29.9 |

| Hispanic | 13.2 | 13.0 | 13.3 |

| White | 59.2 | 61.9 | 56.8 |

| Socioeconomic Status (SES) | |||

| Lower | 27.7 | 24.3 | 30.8 |

| Middle | 47.1 | 49.1 | 45.2 |

| Upper | 25.2 | 26.6 | 23.9 |

| Health Insurance Status | |||

| Private | 64.1 | 67.2 | 61.4 |

| Public only | 24.0 | 18.0 | 29.4 |

| None | 11.8 | 14.7 | 9.2 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||

| <25 | 30.1 | 26.6 | 33.3 |

| 25-30 | 34.4 | 40.7 | 28.6 |

| 30+ | 22.0 | 25.8 | 18.6 |

| Physical Activity | |||

| Low | 27.4 | 26.8 | 27.8 |

| Moderate | 50.6 | 47.4 | 53.6 |

| High | 22.0 | 25.8 | 18.6 |

| Depression | 17.2 | 14.0 | 20.1 |

| Number of Types of Childhood Abuse | |||

| 0 | 61.3 | 61.7 | 61.0 |

| 1 | 20.2 | 21.3 | 19.2 |

| 2 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 11.6 |

| 3 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 8.2 |

| Number of Types of Adolescent / Adult Abuse | |||

| 0 | 64.3 | 68.6 | 60.3 |

| 1 | 18.5 | 19.4 | 17.8 |

| 2 | 11.2 | 8.4 | 13.8 |

| 3 | 6.0 | 3.6 | 8.2 |

| In the last six months, has anyone close to you caused you special worry or been especially demanding? (yes) | 50.0 | 46.0 | 53.6 |

| Has a sibling caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? (yes) | 13.5 | 12.6 | 14.3 |

| Has someone at work caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? (yes) | 9.0 | 9.4 | 8.6 |

| Trouble paying for transportation, housing, health or medical care, medications, or food. | 25.4 | 23.5 | 27.1 |

Prevalence of Symptoms Suggestive of PBS

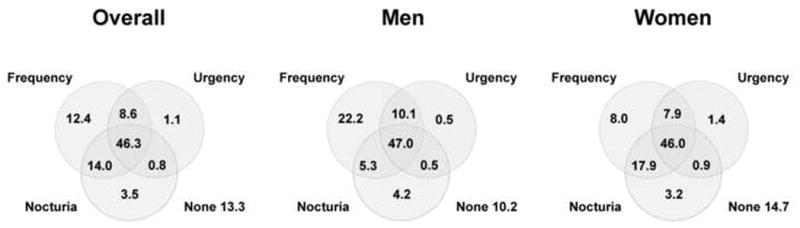

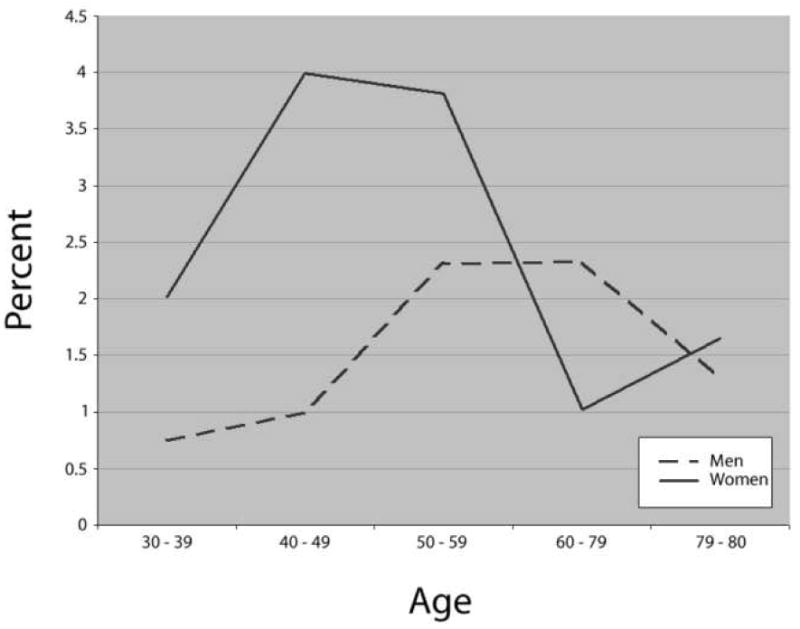

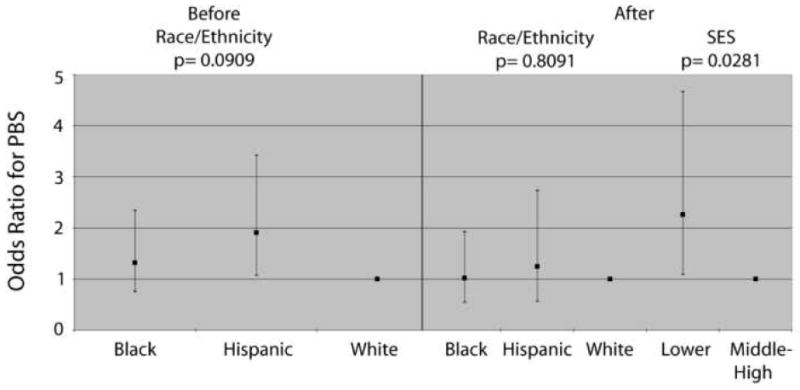

The overall prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS is two percent (155 BACH participants) with twice the prevalence in women (2.6%) as men (1.3%). Figure 1 shows that the vast majority of respondents with symptoms suggestive of PBS also have frequency, urgency, and/or nocturia by our composite definitions. PBS is most common among middle-aged respondents with an earlier peak in women (Figure 2). PBS is most common among minorities and those of lower SES (Table 2). Any effect due to race/ethnicity disappears if SES is added to the model (Figure 3). That increased prevalence of PBS is associated with lower SES is further supported in the increased prevalence of PBS in those with only public health insurance, and in those who are having trouble paying for basics (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of frequency, urgency and nocturia (percent) overall, and for men and women for BACH participants with symptoms suggestive of Painful Bladder Syndrome.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (percent) of symptoms suggestive of Painful Bladder Syndrome by gender and age. The p value from a chi-square test of independent is .0925 overall, .3494 in men, and .0249 in women.

Table 2.

Prevalence (percent) of symptoms suggestive of PBS overall and by gender and various covariates. A p value from a chi-square test of independence is given in parentheses.

| Overall | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2.01 | 1.31 | 2.65 |

| Age | (.0925) | (.3494) | (.0249) |

| 30-39 | 1.38 | 0.75 | 2.02 |

| 40-49 | 2.53 | 1.00 | 3.99 |

| 50-59 | 3.11 | 2.31 | 3.81 |

| 60-69 | 1.55 | 2.33 | 1.02 |

| 70-79 | 1.49 | 1.29 | 1.65 |

| Race/Ethnicity | (.0460) | (.2230) | (.2323) |

| Black | 2.32 | 1.33 | 3.08 |

| Hispanic | 3.09 | 2.34 | 3.76 |

| White | 1.63 | 1.09 | 2.16 |

| Marital status | (.1416) | (.1588) | (.6563) |

| married / living with a partner | 1.45 | 0.77 | 2.20 |

| separated / divorced / widowed | 2.44 | 1.82 | 2.74 |

| single / other | 2.67 | 2.06 | 3.29 |

| Socioeconomic status | (.0421) | (.2948) | (.1024) |

| lower | 3.46 | 2.36 | 4.24 |

| middle | 1.56 | 0.97 | 2.14 |

| upper | 1.27 | 0.99 | 1.55 |

| Health insurance status | (.0002) | (.2444) | (.0141) |

| private | 1.45 | 1.16 | 1.73 |

| public only | 4.07 | 2.30 | 5.06 |

| none | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.04 |

| Body Mass Index (wt/kg2) | (.0082) | (.0277) | (.0922) |

| <25 | 1.95 | 1.98 | 1.92 |

| 25-30 | 1.08 | 0.55 | 1.76 |

| 30+ | 2.97 | 1.72 | 3.94 |

| Smoking status | (.7562) | (.9116) | (.6191) |

| never | 2.13 | 1.16 | 2.81 |

| former | 1.71 | 1.39 | 2.02 |

| current | 2.14 | 1.44 | 3.03 |

| Alcoholic drinks (per day) | (.0388) | (.8977) | (.0724) |

| 0 | 2.96 | 1.47 | 3.86 |

| <1 | 1.29 | 1.10 | 1.45 |

| 1-3 | 2.52 | 1.51 | 1.54 |

| 3+ | 2.97 | 1.23 | 9.80 |

| Physical activity | (<.0001) | (.3397) | (<.0001) |

| low | 2.45 | 1.74 | 3.07 |

| moderate | 2.40 | 1.33 | 3.26 |

| high | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.26 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | (.0413) | (.1043) | (.1874) |

| yes | 3.45 | 2.57 | 3.95 |

| no | 1.61 | 1.06 | 2.17 |

| Childhood physical abuse | (.0238) | (.1198) | (.0585) |

| yes | 3.24 | 2.07 | 4.51 |

| no | 1.65 | 1.06 | 2.15 |

| Childhood emotional abuse | (.0163) | (.1404) | (.0571) |

| yes | 3.56 | 2.31 | 4.66 |

| no | 1.65 | 1.09 | 2.17 |

| Adolescent / adult sexual abuse | (.0080) | (.2542) | (.0274) |

| yes | 4.10 | 2.42 | 4.88 |

| no | 1.50 | 1.15 | 1.87 |

| Adolescent / adult physical abuse | (.0035) | (.0175) | (.0668) |

| yes | 4.13 | 3.43 | 4.69 |

| no | 1.49 | 0.84 | 2.10 |

| Adolescent / adult emotional abuse | (.0053) | (.1286) | (.0255) |

| yes | 4.21 | 2.55 | 5.22 |

| no | 1.49 | 1.09 | 1.88 |

| Number of types of childhood abuse | (.0347) | (.1215) | (.1892) |

| 0 | 1.55 | 1.10 | 1.97 |

| 1 | 1.67 | 0.64 | 2.71 |

| 2 | 2.87 | 2.23 | 3.48 |

| 3 | 5.81 | 4.73 | 6.41 |

| Number of types of adolescent / adult abuse | (.0065) | (.2022) | (.0671) |

| 0 | 1.23 | 0.90 | 1.58 |

| 1 | 2.28 | 1.51 | 3.04 |

| 2 | 3.32 | 1.93 | 4.08 |

| 3 | 7.11 | 6.72 | 7.27 |

| In the last six months, has anyone close to you caused you special worry or been especially demanding? | (.0121) | (.4698) | (.0232) |

| yes | 2.68 | 1.51 | 3.59 |

| no | 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.55 |

| Has a spouse or partner caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.2134) | (.4012) | (.2950) |

| yes | 2.92 | 1.82 | 4.16 |

| no | 1.79 | 1.17 | 2.32 |

| Has a parent caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.7858) | (.7876) | (.6012) |

| yes | 2.19 | 1.16 | 3.28 |

| no | 1.98 | 1.34 | 2.54 |

| Has a child caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.0237) | (.5854) | (.0425) |

| yes | 3.39 | 1.63 | 4.33 |

| no | 1.60 | 1.25 | 1.98 |

| Has a sibling caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.0262) | (.3900) | (.0428) |

| yes | 4.66 | 2.25 | 6.58 |

| no | 1.60 | 1.18 | 1.99 |

| Has another relative or friend caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.1646) | (.5719) | (.2091) |

| yes | 2.93 | 1.58 | 4.12 |

| no | 1.83 | 1.26 | 2.35 |

| Has someone at work caused you special worry or been especially demanding in the last six months? | (.1058) | (.3119) | (.1751) |

| yes | 4.72 | 2.52 | 6.88 |

| no | 1.75 | 1.19 | 2.25 |

| Are you having trouble paying for transportation? | (.0039) | (.3037) | (.0086) |

| yes | 4.60 | 2.08 | 6.30 |

| no | 1.63 | 1.22 | 2.02 |

| Are you having trouble paying for housing? | (.0056) | (.1365) | (.0159) |

| yes | 5.14 | 2.43 | 7.25 |

| no | 1.47 | 1.14 | 1.77 |

| Are you having trouble paying for health or medical care? | (.0039) | (.2557) | (.0075) |

| yes | 4.87 | 1.90 | 7.34 |

| no | 1.40 | 1.20 | 1.58 |

| Are you having trouble paying for food? | (.0008) | (.3446) | (.0008) |

| yes | 5.30 | 2.25 | 7.50 |

| no | 1.52 | 1.19 | 1.83 |

| During the last month, how often have urinary experiences, pain, or discomfort in your pubic area interfered with overall fluid intake (including increasing or decreasing)? | (.0001) | (.0291) | (.0065) |

| none of the time | 1.19 | 0.72 | 1.64 |

| a little of the time | 5.54 | 5.32 | 5.66 |

| some of the time | 10.25 | 12.80 | 8.69 |

| most of the time | 7.57 | 6.22 | 8.47 |

| all of the time | 18.60 | 9.62 | 24.64 |

Figure 3.

Odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals for the association of symptoms suggestive of Painful Bladder Syndrome and race/ethnicity before and after adjusting for socioeconomic status (SES). Note that gender and age are included in each model.

Association of Symptoms Suggestive of PBS and Demographics, Lifestyle, and Psycho-social Correlates

Women who are obese have higher prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS, while men who are overweight have a lower prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS (Table 2). Smoking is not associated with symptoms suggestive of PBS. Women with light to moderate alcohol intake (less than 3 drinks per day) or high levels of physical activity are less likely to have symptoms suggestive of PBS. Both men and women who have been abused are more likely to have symptoms suggestive of PBS, with increasing prevalences of symptoms for those who have experienced multiple types of abuse. Those who are worried about someone close to them, or who report that urinary experiences or pain increases or decreases their overall fluid intake are also more likely to report symptoms suggestive of PBS.

In multivariate logistic models (Table 3) (including gender, race/ethnicity, age, and SES regardless of their level of significance) we find that PBS remains associated with BMI in men (symptoms are less common if a man is overweight compared to BMI less than 25), women with high levels of physical activity are less likely to have symptoms compared with low levels of physical activity, worry about a sibling or trouble paying for basics increases the odds of symptoms suggestive of PBS in women, and abuse increase the odds of symptoms suggestive of PBS among both men and women. As we have shown that depression is significantly associated with all urologic symptoms including PBS 18 and many of these psychosocial variables are also associated with depression (data not shown), we added depression to this model (Table 4). The odds ratios for abuse, worry, and trouble paying for basics are slightly smaller, but similar conclusions can be reached.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic model predicting symptoms suggestive of PBS overall and by gender including odds ratio (OR), 95 percent confidence intervals (CI), and associated p values.

| Overall | Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Gender | .1550 | ||||||||

| Men | 0.65 | 0.36, 1.18 | |||||||

| Women | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Age Group | .0629 | .3793 | .0195 | ||||||

| 30-39 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 40-49 | 1.90 | 0.95, 3.80 | 1.31 | 0.33, 5.20 | 2.34 | 1.01, 5.43 | |||

| 50-59 | 2.58 | 1.27, 5.24 | 2.98 | 0.81, 10.97 | 2.25 | 0.95, 5.34 | |||

| 60-69 | 1.21 | 0.54, 2.75 | 2.89 | 0.69, 12.11 | 0.61 | 0.21, 1.81 | |||

| 70-79 | 1.59 | 0.53, 4.79 | 2.17 | 0.46, 10.33 | 1.37 | 0.30, 6.31 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | .1228 | .2588 | .4457 | ||||||

| Black | 0.99 | 0.52, 1.88 | 1.13 | 0.51, 2.53 | 0.89 | 0.35, 2.26 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.68 | 0.89, 3.20 | 2.46 | 0.82. 7/42 | 1.32 | 0.59, 2.95 | |||

| White | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| SES | .4321 | .6232 | .8477 | ||||||

| Lower | 1.51 | 0.80, 2.82 | 1.77 | 0.50, 6.23 | 1.18 | 0.66, 2.11 | |||

| Middle | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| Upper | 1.23 | 0.45, 3.36 | 1.21 | 0.27, 5.39 | 1.04 | 0.26, 4.18 | |||

| BMI | .0625 | .0313 | .2954 | ||||||

| <25 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 25-30 | 0.51 | 0.26, 1.01 | 0.27 | 0.10, 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.28, 2.01 | |||

| 30+ | 1.02 | 0.57, 1.84 | 0.83 | 0.34, 2.01 | 1.25 | 0.55, 2.87 | |||

| Physical Activity | .0278 | .7817 | .0023 | ||||||

| low | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| moderate | 1.13 | 0.67, 1.91 | 0.96 | 0.39, 2.37 | 1.25 | 0.62, 2.50 | |||

| high | 0.33 | 0.13, 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.19, 2.37 | 0.10 | 0.03, 0.43 | |||

| Number of types of adult abuse | .0178 | .1109 | .2949 | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 1 | 1.70 | 0.80, 3.60 | 1.68 | 0.45, 6.24 | 1.70 | 0.66, 4.37 | |||

| 2 | 1.57 | 0.80, 3.09 | 1.74 | 0.57, 5.36 | 1.47 | 0.64, 3.39 | |||

| 3 | 2.81 | 1.47, 5.36 | 5.86 | 1.32, 26.01 | 2.04 | 0.96, 4.33 | |||

| Worry about a sibling | 2.01 | 1.15, 3.52 | .0150 | 1.34 | 0.28, 6.38 | .7109 | 2.64 | 1.49. 4.67 | .0009 |

| Worry about someone at work | 2.34 | 1.18, 4.61 | .0145 | 2.04 | 0.57, 7.31 | .2710 | 2.19 | 0.98, 4.90 | .0550 |

| Trouble paying for basics | 3.20 | 1.83, 5.59 | <.0001 | 1.58 | 0.61, 4.08 | .3458 | 4.81 | 2.46, 9.38 | <.0001 |

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic model from Table 3 with depression added, predicting symptoms suggestive of PBS overall and by gender including odds ratio (OR), 95 percent confidence intervals (CI), and associated p values.

| Overall | Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Gender | .1972 | ||||||||

| Men | 0.67 | 0.37, 1.23 | |||||||

| Women | 1.00 | reference | |||||||

| Age Group | .0520 | .2023 | .0154 | ||||||

| 30-39 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 40-49 | 2.00 | 1.00, 3.99 | 1.34 | 0.35, 5.13 | 2.41 | 1.04, 5.57 | |||

| 50-59 | 2.78 | 1.39, 5.57 | 3.04 | 0.83, 11.14 | 2.44 | 1.04, 5.73 | |||

| 60-69 | 1.39 | 0.61, 3.14 | 3.67 | 1.01, 13.28 | 0.66 | 0.22, 1.96 | |||

| 70-79 | 1.86 | 0.62, 5.55 | 2.77 | 0.67, 11.44 | 1.51 | 0.32, 7.05 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | .1739 | .2871 | .5611 | ||||||

| Black | 0.97 | 0.50, 1.88 | 1.06 | 0.46, 2.46 | 0.90 | 0.34, 2.34 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.58 | 0.83, 2.99 | 2.34 | 0.77, 7.17 | 1.25 | 0.56, 2.80 | |||

| White | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| SES | .6568 | .7992 | .9790 | ||||||

| Lower | 1.30 | 0.70, 2.42 | 1.54 | 0.43, 5.45 | 1.05 | 0.60, 1.82 | |||

| Middle | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| Upper | 1.29 | 0.47, 3.54 | 1.27 | 0.31, 5.20 | 1.11 | 0.27, 4.55 | |||

| BMI | .0562 | .0220 | .3512 | ||||||

| <25 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 25-30 | 0.49 | 0.25, 0.98 | 0.28 | 0.11, 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.27, 1.89 | |||

| 30+ | 0.99 | 0.54, 1.80 | 0.92 | 0.36, 2.36 | 1.16 | 0.51, 2.61 | |||

| Physical Activity | .0378 | .8352 | .0028 | ||||||

| low | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| moderate | 1.30 | 0.74, 2.28 | 1.27 | 0.49, 3.29 | 1.33 | 0.64, 2.80 | |||

| high | 0.41 | 0.15, 1.13 | 1.01 | 0.27, 3.83 | 0.11 | 0.03, 0.49 | |||

| Number of types of adult abuse | .0595 | .2849 | .4987 | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | |||

| 1 | 1.63 | 0.77, 3.47 | 1.59 | 0.46, 5.54 | 1.62 | 0.61, 4.28 | |||

| 2 | 1.34 | 0.68, 2.61 | 1.28 | 0.37, 4.42 | 1.28 | 0.55, 2.96 | |||

| 3 | 2.30 | 1.25, 4.22 | 4.14 | 0.91, 18.93 | 1.73 | 0.83, 3.62 | |||

| Worry about a sibling | 1.76 | 1.02, 3.02 | .0423 | 1.04 | 0.26, 4.15 | .9554 | 2.41 | 1.37, 4.24 | .0025 |

| Worry about someone at work | 2.17 | 1.09, 4.32 | .0270 | 1.83 | 0.55, 6.09 | .3257 | 2.14 | 0.95, 4.82 | .0651 |

| Trouble paying for basics | 2.70 | 1.50, 4.84 | .0009 | 1.38 | 0.51, 3.75 | .5214 | 3.99 | 1.97, 8.09 | .0001 |

| Depression | 2.62 | 1.55, 4.43 | .0003 | 3.86 | 1.22, 12.19 | .0215 | 2.24 | 1.33, 3.75 | .0023 |

Discussion

While the BACH study was designed without the prescience of the current controversies in nomenclature and definition 19, in retrospect, the questions asked are remarkable in their ability to adapt to current concepts of definition, despite their slight differences from the ESSIC or ICS criteria.

The prevalence of PBS is thought to be much more common in women than men (the NIDDK web site states 90% female 7). It is likely that men with similar symptoms are diagnosed with chronic prostatitis / chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) instead of IC/PBS. We have shown a considerable overlap of symptoms suggestive of PBS and symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS (with no common questions) 20. If a man has symptoms suggestive of CP/CPPS, he has 9.6 times the odds of also having symptoms suggestive of PBS 20. Clemens and colleagues 5 find the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of interstitial cystitis to be 2.5 times higher in women compared to men.

The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS decreases as men and women get older. There are no data showing an increased prevalence over time. Temml and colleagues found the highest prevalence of interstitial cystitis among women aged 19-89 participating in a health screening, in the middle years of age 40-59 21. Clemens and colleagues found the highest prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms among adults aged 25-80 in a managed care population, between age 41-45 in women and 46-50 in men 5.

Our data suggest that these symptoms may disappear as people get older. We will better understand this evolution of symptoms as BACH transitions from a cross-sectional to a longitudinal study. If the symptoms do tend to resolve or abate over time in a significant number of people, it would suggest that treatment algorithms should be modified to reflect this, allowing the patient and physicians to consider time as an ally in the treatment process.

Women with high levels of physical activity are less likely to have symptoms. The cross-sectional nature of our study precludes the establishment of causal associations, but this finding suggests that research evaluating exercise as a method of both prevention and treatment may be indicated.

The association of abuse and IC/PBS has been noted previously 22. We confirm their findings and also note that their effect size is similar to what we report here. We have also found that abuse is associated with urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia 13, common additional symptoms in those with symptoms suggestive of PBS, figure 1. Selective recall of childhood abuse may be the reason that symptoms are more strongly associated with adult abuse. It may be worthwhile for physicians treating these chronic pain syndromes to ask in a sensitive and caring fashion the questions that will illicit this type of history. The physician should be prepared to provide support for the patient as well as pertinent referrals to mental health professionals, counselors, and community support centers.

The increased prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS in those of lower SES is new. This has been noted as increased prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS in those with only public health insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) as well as increased prevalence in those who are having trouble paying for basics. While the initial prevalence of symptoms suggestive of PBS in higher among minorities, this effect disappears once SES is added to the model. This finding may be due to the community-based sample of BACH rather than a sample of patients in the health care system. In analyzing the direct costs of IC/PBS in the US healthcare system, Payne and colleagues found that the vast majority of office visits for these diagnoses are by Whites 23. When contrasted with our findings of higher prevalence of symptoms in those of lower SES, this may suggest that patients with these symptoms of lower SES may not be seeking out or receiving medical care for these symptoms at the same rate as those with higher SES. In addition, if a large subset of those with symptoms suggestive of PBS remain undiagnosed, it is likely that the true costs of PBS for society and the healthcare system are much greater than previously appreciated. This very interesting and unexpected finding also suggests the need to follow SES in conjunction with IC/PBS symptoms in a longitudinal fashion and also to target prevention and treatment trials in this subpopulation.

This study suggesting that one needs to take into account psychosocial variables such as abuse, worry, and lower socioeconomic status is in line with current thinking on urologic pain disorders 24.

A major strength of this study is that it uses a randomly selected community-based sample of adults with considerable race/ethnic diversity over a wide age range of 30-79 not a patient population. Another strength of the study is the large number of covariates that we were able to consider. An unavoidable limitation is the small number of respondents with symptoms suggestive of PBS (155) due to the low prevalence of PBS which obviously limits our statistical power. Another potential limitation is the operational definition of PBS, but people suffer from symptoms not necessarily a diagnosed condition. It also does not include ethnic minorities that are not well represented in Boston. However, we have found that the prevalence of most health related covariates in BACH are comparable to national numbers reported by NHANES, National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) surveys, which suggests that the BACH results (with suitable modifications due to different demographics) may be generalizable to the United States.

Conclusion

We have shown that PBS is associated with a number of lifestyle and psychosocial correlates. This suggests that the management of patients with PBS (physical symptoms) may benefit from a multi-faceted approach of combining medical and psychological, and cognitive treatment.

Acknowledgments

BACH funded by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders, U01 DK56842.

Key To Abbreviations

- BACH

Boston Area Community Health

- BMI

Body mass index

- CP/CPPS

Chronic prostatitis / Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- IC

Interstitial cystitis

- OR

Odds ratio

- PBS

Painful bladder syndrome

- SES

Socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van de Merwe J, Nordling J, Bouchelouche K, P B. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome / interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leppilahti M, Tammela TL, Huhtala H, Auvinen A. Prevalence of symptoms related to interstitial cystitis in women: a population based study in Finland. J Urol. 2002;168:139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parsons JK, Kurth K, Sant GR. Epidemiologic issues in interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69:5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O'Keeffe Rosetti MC, Brown SO, Gao SY, Calhoun EA. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174:576. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165170.43617.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens JQ, Link CL, Eggers PW, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Jr, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of painful bladder symptoms and effect on quality of life in black, Hispanic and white men and women. J Urol. 2007;177:1390. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Interstitial Cystitis / Painful Bladder Syndrome http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/interstitialcystitis/:

- 8.Novi JM, Jeronis S, Srinivas S, Srinivasan R, Morgan MA, Arya LA. Risk of irritable bowel syndrome and depression in women with interstitial cystitis: a case-control study. J Urol. 2005;174:937. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169258.31345.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissman MM, Gross R, Fyer A, Heiman GA, Gameroff MJ, Hodge SE, et al. Interstitial cystitis and panic disorder: a potential genetic syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:273. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:389. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanno PM, Landis JR, Matthews-Cook Y, Kusek J, Nyberg L., Jr The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. J Urol. 1999;161:553. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)61948-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren JW, Meyer WA, Greenberg P, Horne L, Diggs C, Tracy JK. Using the International Continence Society's definition of painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2006;67:1138. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Link CL, Lutfey KE, Steers WD, McKinlay JB. Is abuse causally related to urologic symptoms? Results from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol. 2007;52:397. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green LW. Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behavior. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med. 1995;21:141. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald MP, Link CL, Litman HJ, Travison TG, McKinlay JB. Beyond the lower urinary tract: the association of urologic and sexual symptoms with common illnesses. Eur Urol. 2007;52:407. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanno PM. Re-imagining interstitial cystitis. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:91. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry MJ, Link CL, McNaughton-Collins MF, McKinlay JB. Overlap of different urological symptom complexes in a racially and ethnically diverse, community-based population of men and women. BJU Int. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temml C, Wehrberger C, Riedl C, Ponholzer A, Marszalek M, Madersbacher S. Prevalence and correlates for interstitial cystitis symptoms in women participating in a health screening project. Eur Urol. 2007;51:803. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters KM, Kalinowski SE, Carrico DJ, Ibrahim IA, Diokno AC. Fact or fiction--is abuse prevalent in patients with interstitial cystitis? Results from a community survey and clinic population. J Urol. 2007;178:891. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne CK, Joyce GF, Wise M, Clemens JQ. Interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:2042. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemens JQ. Male and Female Pelvic Pain Disorders-Is it All in Their Heads? J Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]