Abstract

Allylic esters of nitrobenzene acetic acids undergo facile palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling. Both mono- and dinitroarene substrates give high yields of the coupled products. Moreover, the rates of the reactions suggest that decarboxylation is rate-limiting and substrates that sterically disfavor attainment of the reactive conformation for decarboxylation are not viable. Finally, reduction of the product nitroarenes to the corresponding anilines provides access to a variety of heterocycles including quinolines and dihydroquinolones.

Nitroarenes are important intermediates in the synthesis of polymers, azo dyes, and pharmaceuticals such as Viagra®, Zyvox®, and Angerase®.1 Thus, it is expected that the development of new methods for the cross-couplings of nitroarenes will facilitate synthesis of heterocycles that are prevalent in pharmaceuticals.

Recently, interest in the area of decarboxylative coupling has grown, due in part to the fact that these reactions occur under neutral conditions and avoid the use of reagents that are typically necessary for transmetalation.2 For example, Gooβen and coworkers have reported a Pd(II)-catalyzed coupling of nitrobenzoic acids with haloaromatics to generate biaryl products.3 Furthermore, Myers has shown a Pd(II)-catalyzed decarboxylative variant of the Heck reaction.4 While these advancements represent significant accomplishments in the field of palladium-catalyzed coupling of sp2-hybridized carbons, catalysis of the decarboxylative coupling of sp3-hybridized carbons remains a significant challenge. Current methods for sp3-sp3 coupling are limited by the requirement for stoichiometric organometallic that is necessary to effect transmetalation.5

|

(1) |

We recently demonstrated the Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative benzylic coupling of nitrogen-containing heteroaromatics with allyl electrophiles (eq 1).6 This reaction proceeded by a unique allylation/aza-Cope rearrangement that did not translate to more general benzylic couplings. Herein, we report a new method for the decarboxylative coupling of nitrobenzene acetic esters.

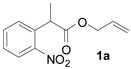

To begin, both o- and p-nitrophenylacetic esters were synthesized to screen different catalyst/ligand combinations for activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Catalyst and Ligand Screening

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Catalyst/Ln | Temp. (°C) | 2:3 |

| 1 | o-NO2 | Pd(PPh3)4 | 25 | NR |

| 2 | o-NO2 | Pd(PPh3)4 | 110 | 1.8:1 |

| 3 | o-NO2 | Pd2dba3/rac-BINAP | 110 | 100:0 |

| 4 | p-NO2 | Pd2dba3/rac-BINAP | 110 | 4.9:1 |

| 5 | p-NO2 | Pd2dba3/dppe | 110 | 2:1 |

| 6 | p-NO2 | Pd2dba3/dppf | 110 | 1.6:1 |

ratios determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude reaction mixtures

Although the reaction failed to produce any product at ambient temperature, increasing the temperature to 110 °C readily promoted decarboxylation in the presence of the palladium catalysts, however products of aromatic allylation were prevalent. Ultimately, rac-BINAP proved to be the most selective ligand for benzylic allylation of both o- and p-nitro benzyl derivatives (entries 3 and 4).

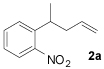

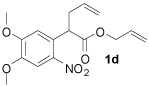

Once standard conditions were determined, a variety of o-nitroand p-nitro-substituted aryl substrates were tested (Table 2). All terminally unsubstituted allyl esters gave clean conversion to the desired products in high yield. It is noteworthy that functional groups, such as esters and ketones (1b, 1c), were tolerated and no products arising from allylation of enolates were observed.7 Furthermore, addition of electron-donating methoxy substituents did not affect reaction time or yield (Table 2, entry 4).

Table 2.

Decarboxylative Coupling of Substituted Nitrophenylacetic Estersa

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

86 |

| 2 |  |

|

85 |

| 3 |  |

|

77 |

| 4 |  |

|

94 |

| 5b |  |

<5 | |

| 6 |  |

|

77 |

| 7 |  |

|

96 |

| 8 |  |

|

94 |

0.3 mmol substrate, 0.0075 mmol Pd2dba3, 0.015 mol rac-BINAP, 3 mL toluene, 110 °C, 1–3 hrs.

Pd(PPh3)4 as catalyst

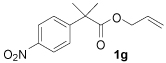

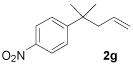

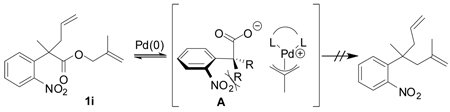

The fact that α-mono- and α,α-disubstituted p-nitrophenyl acetic esters (1f–1h) underwent facile decarboxylative coupling indicates that decarboxylation must precede C—C bond formation.8 Interestingly, decarboxylative coupling of o-nitrophenyl acetic esters is limited to substrates that are α-monosubstituted; treatment of 1i to the standard conditions of catalysis produced no product nor degradation of starting material (eq 2).9 It can be reasoned that for decarboxylation to occur, the carboxylate must align perpendicular to the electron-accepting arene. This results in a high energy conformation where there is significant A-strain (A), thus precluding decarboxylation. Since this steric hindrance is not present when the p-nitro group is employed, decarboxylation of those substrates can be achieved.

|

(2) |

While the previous examples have focused on terminally unsubstituted allyl electrophiles, the coupling of alkyl-substituted allyl groups is also desirable. Unfortunately, when ester 1e was synthesized and subjected to the standard reaction conditions, the reaction did not proceed (Table 1). The reaction did proceed when Pd(PPh3)4 was employed as the catalyst, however elimination to form 1,3-pentadiene was prevalent.

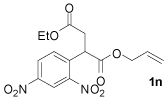

The hypothesis that elimination was favored because the intermediate benzylic anion was too basic led us to believe that dinitroarene substrates would be suitable for coupling with substituted allyl electrophiles (Table 3). While the previously optimized reaction conditions failed to produce clean reaction mixtures with the dinitroarene substrates, Pd(PPh3)4 was found to be a very efficient catalyst. Under these conditions, alkyl- and aryl-substituted allyl electrophiles (1j, 1l) undergo smooth decarboxylative coupling with the dinitroarene reactants. For example, when employing 1j, no elimination products were observed and a 95% yield was obtained; no decarboxylative coupling product was observed with the related mononitrobenzyl ester (1e). Unfortunately, the coupling of a prenyl-substituted allyl ester still lead to low yields due to competing elimination (entry 2). However, functional group compatibility similar to that observed for the mononitroarene complexes was maintained (entry 5). Moreover, the reactions were facile at ambient temperature; all starting material was consumed within 3 hours. The fact that the rate of the reaction increases with increased stability of the benzylic anion suggests that the rate-limiting step of catalysis is decarboxylation.

|

(3) |

Table 3.

Decarboxylative Coupling of Di-Nitrophenyl Acetic Estersa

| Entry | Substrate | Product | % Yield 2 (dr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

|

95 (1.2:1) |

| 2 |  |

|

26b |

| 3 |  |

|

84 (1.4:1) |

| 4 |  |

|

91 |

| 5 |  |

|

88 |

0.3 mmol substrate, 0.015 mol Pd(PPh3)4, toluene, rt, 1–3 h.

linear : branched ratio = 1.5:1

The utility of nitroarenes in pharmaceutical synthesis lies in their facile reduction to anilines. For example, decarboxylative coupling can be followed by reductive cyclization to afford dihydroquinolones or quinolines (eq. 3). Thus, the coupling of decarboxylative allylation with nitro reduction allows the synthesis of alkylated heterocycles that are common in biologically active molecules.

In conclusion, a new method for catalytic sp3-sp3 coupling has been developed that is based on the facile decarboxylative coupling of nitrobenzene acetates. The process occurs under neutral conditions and does not require reagents that are typically needed for transmetalation.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

We thank the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM079644) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-0548081) for funding.

References

- 1.(a) Ono N. The Nitro Group in Organic Synthesis. New York: Wiley-VCH; 2001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hoogenraad M, van der Linden JB, Smith AA. Org. Proc. Res. Dev. 2004;8:469. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rayabarapu DK, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13510. doi: 10.1021/ja0542688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Gooβen LJ, Rodriguez N, Melzer B, Linder C, Deng G, Levy LM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4824. doi: 10.1021/ja068993+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gooβen LJ, Deng G, Levy LM. Science. 2006;313:662. doi: 10.1126/science.1128684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Myers AG, Tanaka D, Mannion MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11250. doi: 10.1021/ja027523m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka D, Romeril SP, Myers AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10323. doi: 10.1021/ja052099l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Fu G, Saito B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9062. doi: 10.1021/ja074008l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dongol KG, Koh H, Sau M, Chai CLL. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1015. [Google Scholar]; (c) Frisch AC, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:674. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hadei N, Kantchev EAB, O’Brien CJ, Organ MG. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3805. doi: 10.1021/ol0514909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4138. doi: 10.1021/ja070116w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Burger EC, Tunge JA. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4113. doi: 10.1021/ol048149t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mohr JT, Behenna DC, Harned AM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6924. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Xu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17180. doi: 10.1021/ja055968f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) You S-L, Dai L-X. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2006;45:5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Waetzig SR, Rayabarapu DK, Weaver JD, Tunge JA. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2006;45:4977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Protodecarboxylation of nitrobenzene acetic acids: Bull DJ, Fray MJ, Mackenny MC, Malloy KA. Synlett. 1996:647. Ioussaini O, Capedevielle P, Maumy M. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:3229. J. Chem. Soc. 1938:1186.

- 9.A similar effect on the decarboxylation of nitroarenes was recently observed, but not explained. Imao D, Itoi A, Yamazaki A, Shirakura M, Ohtoshi R, Ogata K, Ohmori Y, Ohta T, Ito Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1652. doi: 10.1021/jo0621569.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.