Abstract

We hypothesized that mitochondrial function regulates cell cycle checkpoint activation and radiosensitivity. Human pancreatic tumor cells (MiaPaCa-2, rho+) were depleted of mitochondrial DNA (rho°) by culturing cells in the presence of ethidium bromide. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA was verified by PCR amplification of total DNA using primer pairs specific for mitochondrial DNA. Loss of mitochondrial DNA decreased plating efficiency and the percentage of cells in S phase. Exponential cultures were irradiated with 2, 4 and 6 Gy (dose rate: 0.83 Gy/min) of ionizing radiation and harvested for determination of cell viability, growth and cell cycle phase distributions. Rho° cells were radioresistant compared to rho+ cells, with a dose-modifying factor (DMF) of 1.6. Although cell growth was significantly inhibited in irradiated rho+ cells compared to unirradiated control cells, the inhibition in Rho° cells was minimal. In addition, mitochondrial DNA depletion suppressed radiation-induced G2 checkpoint activation, which was accompanied by increases in both cyclin B1 and CDK1. These results suggest that mitochondrial function may regulate cell cycle checkpoint activation and radio-sensitivity in pancreatic cancer cells.

INTRODUCTION

Radiation damage to cells and tissues involves the generation of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) followed by alterations in lipids, DNA and proteins that can eventually lead to cell dysfunction or cell death (1, 2). The consequential role of ROS in the mechanism of cell cytotoxicity, especially the induction of apoptosis, has received increased attention in the field of cancer radiotherapy (1). The mitochondrial electron transport chain, as well as other biochemical processes, leads to the production of ROS (2, 3). Within the electron transport chain, electron transfer occurs between complexes in the mitochondrial membrane during respiration, with oxygen being the final electron acceptor of the chain. Although oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria is an important energy-producing process for eukaryotic cells (3), this process can also result in producing potentially cell-damaging side products. Due to an inefficient respiratory chain that leaks electrons from the electron transport complexes, approximately 1–5% of the total oxygen consumed in aerobic metabolism produces superoxide ( ) and subsequent formation of other ROS including hydroperoxyl radical ( ), hydroxyl (•OH), carbonate ( ), peroxyl ( ) and the alkoxyl (RO•) radical.

DNA damage by ROS may lead to formation of single-and double-strand breaks, resulting in cell cycle arrest and recruitment of DNA repair enzymes to ameliorate damage. Membranes of cytoplasmic organelles and the plasma membrane of cells are another major target of radiation and ROS. Membrane oxidative damage is generally mediated by the degradation of phospholipids, which are the major constituents of the plasma membrane. Membrane phospholipids are easily peroxidized by ROS produced by ionizing radiation, causing structural and functional impairment. Oxidative damage leads to alterations in both the lipid bilayer fluidity and permeability properties (1). Some cancer cells are relatively resistant to apoptosis. Thus potential strategies to improve the efficacy of radiation could include manipulating the mitochondrial electron transport, leading to oxidative stress and ROS-induced damage within tumor cells (1).

Cell cycle checkpoints are regulatory pathways that control the order and timing of cell cycle transitions and ensure that critical events such as DNA replication and chromosome segregation are completed with high fidelity (4). In addition, checkpoints are pathways that halt the progression of the cell cycle in response to cellular stress or damage (5), inducing the transcription of genes that facilitate repair (4). Checkpoint-dependent arrest is thought to prevent the replication of damaged templates and the segregation of broken chromosomes (4). Defects in these processes cause genomic instability and may predispose cells to carcinogenesis. Cell cycle checkpoint pathways are potential targets for anticancer strategies because abrogation of checkpoint function drives tumor cells toward apoptosis and enhances the efficacy of oncotherapy. Several cellular stresses, including radiation-induced DNA damage, may trigger checkpoint pathways, leading to cell cycle arrest at G2 phase (5). The DNA damage checkpoint mechanism detects damaged DNA and generates a signal that arrests cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, reduces S phase and DNA synthesis, arrests cells in the G2 phase, and induces the transcription of repair genes (4). One important issue is to identify signaling cascades during DNA damage and G2 checkpoint arrest. The cyclin B1/CDK1 complex activity is an important signaling pathway during DNA damage and G2 checkpoint arrest because it regulates cell cycle progression from G2 to M phase (5–8). Cyclin B1 binds to CDK1, which then becomes dephosphorylated and relocated to the nucleus, ensuring the transition toward mitosis (6). Cyclin B1, through its trafficking molecules between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, plays a role in coordinating the process that leads to mitosis. This complex has been detected in the cytoplasm and is implicated in formation of the mitotic spindle (6). In fact, cyclin B1 overexpression has been reported in various cancers, including pancreatic cancer (6).

Recent evidence suggests that cross-talk between mitochondrial-derived ROS levels and cell cycle regulatory proteins could significantly influence the transition between quiescence and proliferative growth (7, 8). We hypothesized that mitochondrial function may regulate cell cycle checkpoint activation and radiosensitivity. Our studies demonstrate that pancreatic cancer cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA were radioresistant compared to cells with functional mitochondrial electron transport chains. In addition, mitochondrial depletion also suppressed radiation-induced G2 checkpoint activation that was accompanied by increases in both cyclin B1 and CDK1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

MIA PaCa-2 (undifferentiated) human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). MIA PaCa-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 2.5% horse serum. MIA PaCa-2 Rho° cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2.5% horse serum, 50 μg/ml uridine and 100 μg/ml sodium pyruvate. All media were obtained from Gibco (Grand Island, NY), and all cells were maintained at 37°C. All cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma and were used only when found to be negative.

Generation of Rho° Cells

To determine the role of mitochondria in radiation-induced G2 check-point activation, Rho° cells depleted of mitochondria DNA (mtDNA) were generated by incubating wild-type MIA PaCa-2 (rho+) cells for 6–8 weeks with 100 ng/ml ethidium bromide (3). After selection, Rho° cells were cultured in the medium specified above at 37°C in an incubator with 95% air and 5% CO2 without ethidium bromide as described previously (9). To verify mtDNA depletion in Rho° cells, total cellular DNA from rho+ and Rho° cells was extracted and subjected to PCR amplification using two pairs of human mtDNA specific primers as described (9): (1) Mts1 (forward) (5′-cctagggataacagcgcaat-3′) and Mtas 1 (reverse) (5′-tagaagagcgatggtgagag-3′), which gave a 630-bp product, and 2) Mts2 (forward) (5′-aacatacccatggccaacct-3′) and Mtas2 (reverse) (5′-ggcagga gtaatcagaggtg-3′), which gave a 532-bp product. As a control, we measured the expression of GAPDH, which is coded by nuclear DNA.

Cell Growth Experiment

Sixty-millimeter plates were seeded with 5 × 104 rho+ or Rho° cells in the medium specified above at 37°C and irradiated the next day with 2, 4 or 6 Gy (dose rate 0.83 Gy/min) of ionizing radiation using a Pantak high-frequency 22 kV and 10 mA X-ray generator. At various times after plating, cells were trypsinized, and the number of cells was determined with a Coulter counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA). Cell population doubling time in hours (DT) was determined in triplicate for each control and radiation treatment group using the following equation:

where t0 is the time at which exponential growth began, t is the time in hours, Nt = cell number at time t, and N0 is the initial cell number (10).

Clonogenic Survival

After irradiation, cells were plated in triplicate into 60-mm tissue culture dishes at limiting dilutions and were incubated for 2 weeks to allow colony formation as described previously (10). The colonies were then fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue (Amresco, Solon, OH). A population of 50 cells per colony was scored. Plating efficiencies (PEs) for untreated control cultures were calculated using the following formula: PE = (number of colonies counted/number of cells seeded) × 100. Surviving fractions (SFs) were calculated using the following formula: SF = (number of colonies counted)/(number of cells seeded × PE).

Cell Cycle Analysis

Rho+ and Rho° cells in exponential growth were irradiated with 2, 4 or 6 Gy and collected within 1 h. Cell cycle phase distributions were measured by flow cytometry using propidium iodide (PI). Briefly, cells were collected and fixed in suspension in 70% ethanol on ice and then stored at −20°C. Cells were centrifuged at 500g, washed with 5 ml HBSS, centrifuged again, and resuspended in 1 ml HBSS. After addition of 0.2 ml phosphate citrate buffer (pH 7.8), cells were incubated at room temperature for 5 min before being washed again and resuspended in HBSS containing 20 μg/ml PI and 10 μg/ml RNase A. After 30 min incubation in the dark at room temperature, PI-stained cells were analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry, and the percentages of cells in G1, S and G2 + M were calculated using MODFIT software.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were collected by scrape harvesting and pelleted by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad DC Brad-ford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Then 30 μg of protein was electrophoresed in a Bio-Rad 4–20% Ready gel for 200 min at 100 V. The proteins were electrotransferred onto a PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membrane (Millipore, Billerica, CA) and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS for 30 min. The membranes were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-hamster cyclin B1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, CA) and rabbit polyclonal anti-CDK1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed five times with 0.1% Tween-PBS (TPBS) and incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:50 000, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). β-Actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a loading control. After washing with TPBS, membranes were stained with Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and exposed to Classic Blue Autoradiography Film (Molecular Technologies, St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SYSTAT. A single-factor AN-OVA, followed by post-hoc Tukey test, was used to determine significant differences between means. All means were calculated from three experiments, and error bars represent standard errors of the mean (SEM). All Western blots, activity assays and activity gel assays were repeated at least twice.

RESULTS

Generation of Rho° Cells

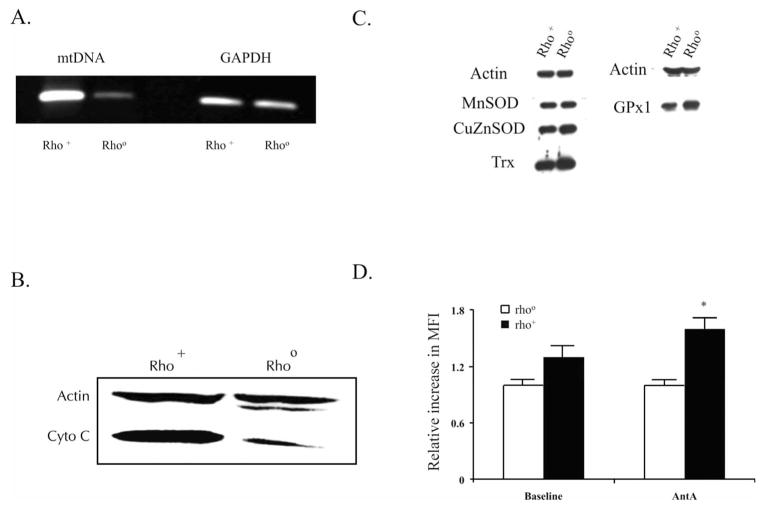

To verify the mtDNA depletion, total cellular DNA was extracted and subjected to PCR using two pairs of human mtDNA specific primers, as described previously (9). Rho+ and Rho° cells contained equivalent amounts of GAPDH, indicating that nuclear DNA was similar between the cell lines (Fig. 1A). However, rho+ cells contained mtDNA, while Rho° cells contained almost no mtDNA (Fig. 1A). To further characterize the Rho° cells, levels of the mitochondrial protein cytochrome C were determined by Western blotting. There was a marked decrease in cytochrome C immunoreactive protein in Rho° cells compared to rho+ cells (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of MIA PaCa-2 Rho° cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Panel A: To verify mtDNA depletion, total cellular DNA was extracted and subjected to PCR using two pairs of human mtDNA specific primers: 1) Mts1 (forward) and Mtas 1 (reverse), which gave a 630-bp product, and 2) Mts2 (forward) and Mtas2 (reverse), which gave a 532-bp product. As a control, we measured the expression of GAPDH, which is coded by nuclear DNA. Panel B: Immunoblot of cytochrome c demonstrating that this protein that is coded by mtDNA is present in rho+ but not in Rho° cells. Panel C: Immunoblots for manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), copper/zinc SOD (CuZnSOD), thioredoxin (Trx), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx1) demonstrating equivalent amounts of these antioxidant proteins in the two cell lines. Panel D: Cells were incubated with DMSO and DMSO containing 10 μM Antymycin A (AntA) for 15 min. Cells were stained for dihydroethidine (DHE) and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. The relative increase in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was calculated relative to Rho° cells. Means, N = 3, *P < 0.05 compared to baseline.

The cytotoxicity of ionizing radiation may be determined by the antioxidant capacity of the cell (11, 12). To determine whether there were changes in antioxidant proteins in Rho° cells after they were selected in ethidium bromide. The levels of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), copper/zinc SOD (CuZnSOD), thioredoxin (Trx) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx1), all proteins encoded by nuclear DNA (Fig. 1C), were determined by Western blotting. Equivalent amounts of protein for these antioxidant enzymes were found in both the Rho° and rho+ cells.

To further confirm the lack of functioning mitochondria in the Rho° cells, we used antimycin A, which is known to inhibit the transfer of electrons from cytochrome b to co-enzyme Q on the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane, leading to increased superoxide production from UBI semiquinone in Complex III, the flavin mono-nucleotide in Complex I, and the FAD site in Complex II. Cells were incubated with DMSO or DMSO containing 10 μM antimycin A (AntA) for 15 min and stained for hydroethidine, and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. Baseline mean fluorescence intensity was higher in rho+ cells compared to Rho° cells, while treatment with antimycin A increased mean fluorescence intensity in rho+ cells but not in the Rho° cells (Fig. 1D).

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Results in Radioresistance in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells

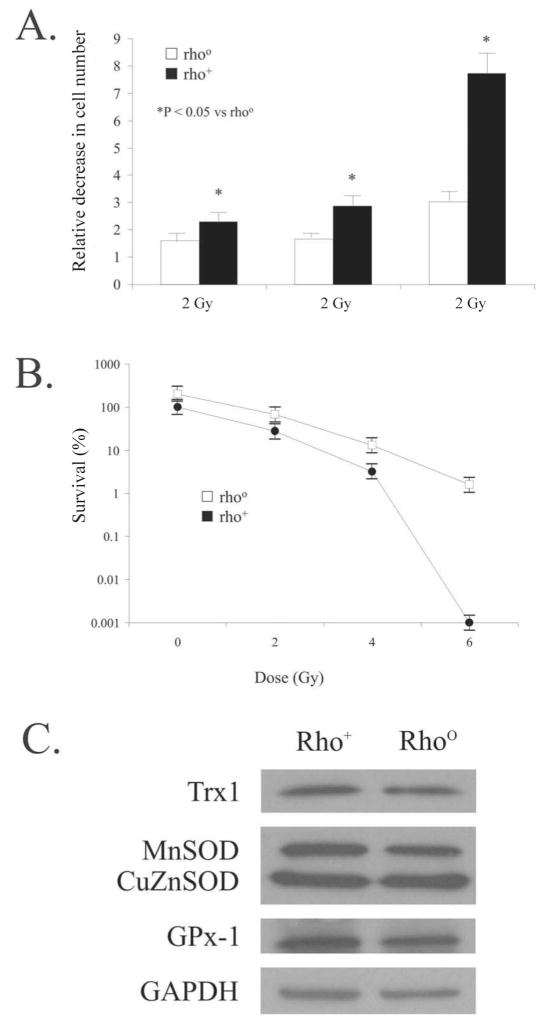

Mitochondria are the major cellular site for the production of ROS (13). Radiation damage to cells and tissues involves the generation of excessive ROS that consequently can lead to cell dysfunction or death (1, 2). Cells were plated in triplicate, and control and treated groups were exposed to 2, 4 or 6 Gy of ionizing radiation. Ionizing radiation significantly decreased cell numbers 5 days after irradiation in pancreatic cancer cells with functional mitochondria compared to cells without functional mitochondria (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Panel A: Depletion of mitochondria induces radioresistance in human pancreatic cancer cells. Exponential cultures of MIA PaCa-2 (rho+) and Rho° cells were irradiated with 2, 4 and 6 Gy, and cell growth was determined. There was a significant decrease in cell numbers after irradiation on day 5 in the rho+ cells compared to the Rho° cells. Panel B: Depletion of mitochondria induces radioresistance in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cells were irradiated with 2, 4 and 6 Gy, and then plated for colony formation. At 6 Gy, a dose modification factor of 1.6 was seen. Means ± SEM, N = 3. Panel C: Immunoblots for MnSOD, Cu-ZnSOD, Trx and GPx1 after 4 Gy demonstrating equivalent amounts of these antioxidant proteins in the two cell lines.

Cells without functional mitochondria were also radio-resistant compared to the parental cell line as determined by clonogenic survival assay. Ionizing radiation decreased clonogenic survival in rho+ human pancreatic cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner but had less effect on cells lacking functional mitochondria (Fig. 2B), resulting in a dose modification factor of 1.6 at 6 Gy.

The difference in the radioresistance of the cell lines was not due to changes in antioxidant content after irradiation. Immunoblotting was performed to determine the levels of MnSOD, CuZnSOD, Trx and GPx1, all proteins encoded by nuclear DNA (Fig. 2C). Western blotting demonstrated equivalent amounts of protein for these antioxidant enzymes in both the Rho° and rho+ cells after irradiation with 4 Gy.

Mitochondrial DNA Depletion Suppresses Radiation-Induced G2 Checkpoint Activation in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells

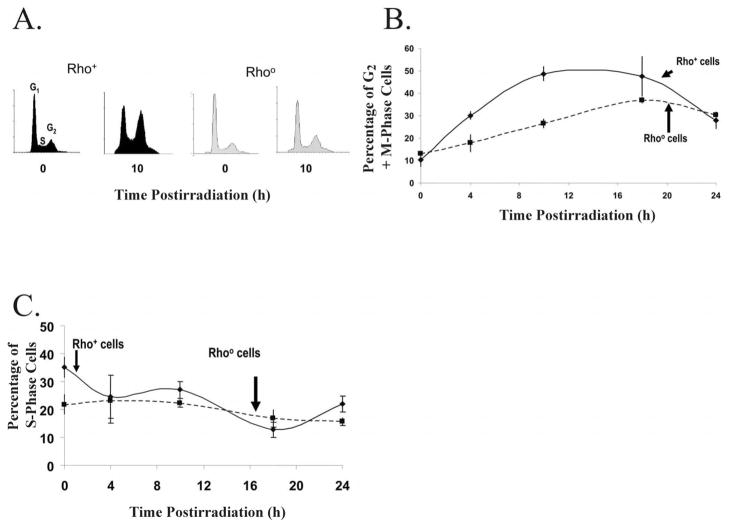

Cell cycle checkpoints are regulatory pathways that halt the progression of cell cycle in response to cell stress or damage (5), thus preventing the replication of damaged templates and the segregation of broken chromosomes (4). Exponentially growing asynchronous cultures of MIA-PaCa-2 rho+ and Rho° cells were irradiated with 4 Gy, and cells were harvested at various times after irradiation, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). There was a significant increase in the percentage of rho+ cells in G2 10 h after irradiation (Fig. 3A, B) but no statistically significant increase in the percentage of Rho° cells in G2 (Fig. 3A, B). The increase in the percentage of rho+ cells in G2 was significantly greater than that of Rho° cells 10 h postirradiation. In addition, the kinetics of the response of the cell lines was different. Accumulation of rho+ cells in G2 peaked at 10 h postirradiation, while the percentage of Rho° cells in G2 appeared to peak at approximately 18 h (Fig. 3B). Neither cell line demonstrated any significant changes in the distribution of cells in S phase (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Panel A. Mitochondrial DNA depletion suppressed radiation-induced G2 checkpoint activation in human pancreatic cancer cells as measured by propidium iodide fluorescence. Panel A: Exponentially growing asynchronous cultures of MIA-PaCa-2 rho+ and Rho° cells were irradiated with 4 Gy and harvested at various times after irradiation, and PI-stained cells were analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry. Panel B: Cells containing mitochondrial DNA showed a significant increase in the percentage of cells in G2 phase 10 h after irradiation. Panel C: Rho+ and Rho° cells did not demonstrate any significant differences in the numbers of cells in S phase after irradiation.

Radiation-Induced Suppression of Cyclin B1 and CDK1 is Reversed in Cells Depleted of Mitochondrial DNA

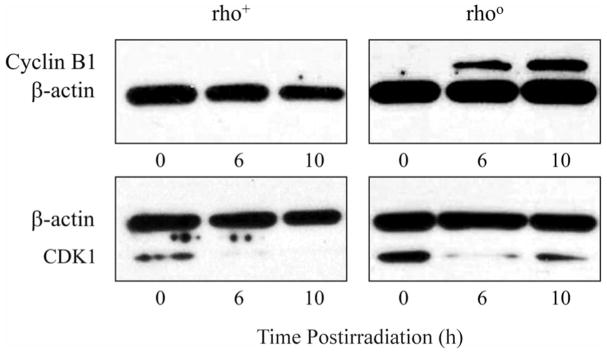

Cyclin B1 and CDK1 are essential components of the maturation and mitosis-promoting factors that regulate the G2/M transition (6–8). Cyclin B1 binds to CDK1, which then becomes dephosphorylated and relocated to the nucleus, ensuring the transition toward mitosis (7). We hypothesized that arrest of cells in G2 would result in depletion of these cell cycle proteins. Western blot analysis of rho+ and Rho° cells was performed to determine the presence of cyclin B1. At 6 and 10 h postirradiation, Rho° cells had increased levels of cyclin B1 immunoreactive protein, while rho+ cells had no cyclin B1 (Fig. 4A). In addition, the baseline levels of CDK1 immunoreactive protein were equivalent in the two cell lines (Fig. 4B). However, at 10 h after irradiation, Rho° cells had increased CDK1 protein compared to the rho+ cells.

FIG. 4.

Panel A: Western blot analysis of rho+ and Rho° cells before and after exposure to 4 Gy of radiation. After irradiation, Rho° cells had increased cyclin B1 protein at 6 and 10 h, while rho+ cells had no cyclin B1. Panel B: Western blot analysis of rho+ and Rho° cells before and after exposure to 4 Gy radiation. Prior to irradiation, CDK1 protein was similar in the two cell lines. After irradiation, Rho° cells had increased CDK1 protein at 10 h compared to rho+ cells.

DISCUSSION

Adjuvant therapy has been administered to patients with resectable pancreatic cancer in an attempt to improve local control and overall survival (14–17). External-beam radiation in conjunction with surgery for locally confined, lymph node negative pancreatic adenocarcinoma is associated with a significantly improved rate of survival compared to that of patients who receive only cancer-directed surgery (18). Additionally, the overall survival improved in patients who received radiation therapy in conjunction with cancer-directed surgery, with a median survival of 17 months and a 5-year survival rate of 13% in patients receiving radiation and surgery compared with 12 months and 9.7%, respectively, for patients received surgery without adjuvant radiation therapy (19). Because of the overall dismal prognosis associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, more effective therapies are needed to control progression and metastatic disease while limiting toxic side effects.

To investigate the role of the mitochondria in radiation-induced death of pancreatic cancer cells, we developed pancreatic cancer cells lacking functional mitochondria. It has been shown previously that radiation damage to cells involves the generation of excessive ROS, which can lead to cell dysfunction or death (1, 2). Since mitochondria are the major cellular site for the production of ROS (13), our study supports the hypothesis that cells lacking functional mitochondria may experience less radiation-induced damage or death than cancer cells with fully functional mitochondria. Pancreatic cancer cells without functional mitochondria exhibited significantly less radiation-induced cytotoxicity compared to cells with fully functional mitochondria. Our results contrast with those of previous studies demonstrating that HeLa EB8-C rho+ cells infected with human papilloma virus were more resistant to ionizing radiation compared to the HeLaEB8-C Rho° cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA (20). In that study, Rho° cells demonstrated both a radiation-induced delayed G2 checkpoint arrest and an impaired ability to recover from the G2 check-point arrest compared to the parental cell line. The difference in our study may be explained by the different cell lines used (pancreatic and cervical) or the fact that our cells were not infected virally.

The generation of the Rho° cells may result in other non-mitochondrial changes that can affect cell function (21). Various proteins responsible in cell signaling pathways have recently been described as translocating to mitochondria (21). Some of these proteins retain their initial function, while others appear to have acquired new a function by interacting with mitochondrial proteins (22). Although the energy requirement for cell cycle progression has not been thoroughly elucidated, mitochondrial generation of ATP should also be considered as a potentially significant control that governs cell cycle progression. Disrupting mitochondrial function alters the availability of cellular energy, sensitizing cells to division (23–27). Blocking ATP synthase reduces the level of total cellular ATP and induces a substantial accumulation of cells in the G1/S phase (28). Even when cell cycle proteins are unchanged, blocking ATP synthase can lead to increased amounts of hypo-phosphorylated proteins (28). Thus a complex range of issues arise because of non-functional mitochondria that may play a significant role in the reduction of radiation-induced cell death in the pancreatic cancer Rho° cells.

In an attempt to determine other factors affected by mtDNA depletion that could also be contributing to radioresistance, we investigated the G2 cell cycle checkpoint of the human pancreatic cancer cells exposed to radiation. Cell cycle checkpoints are regulatory pathways that inhibit the progression of the cell cycle in reaction to cell damage (5). This is thought to prevent the replication of damaged templates and the segregation of broken chromosomes. Through cellular signaling processes, transcription or repair genes are induced (4) or there is apoptosis of the cell (6). We hypothesized that a delay or suppression of G2 checkpoint in Rho° cells may be associated with its radioresistance.

Our present study demonstrates that radiation-induced G2 arrest results in depletion of cyclin B1 and CDK1. Previous studies (20, 29s showed that the ionizing radiation-induced decrease in cyclin B1 expression (mRNA and protein levels) was associated with cells accumulating in G2. Our results are consistent with these previous studies. Under normal conditions of cell growth, an increase in cyclin B1 in late G2 and its rapid turnover during cell division are necessary for the exit of cells from G2 and M phases. This regulation is perturbed in irradiated cells. In addition, a dose-dependent increase in mitotic delay accompanied by down-regulation of cyclin B1 was found after irradiation in NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells (30). Moreover, studies by Lin and colleagues support the correlation between G2 cell cycle arrest, a decline in cyclin B1 and CDK1, and cell death (31). In these studies, treatment with Prazosin led to a concentration-dependent and time-dependent G2/M arrest of the cell cycle that correlated with inhibition of CDK1, a short-term elevation followed by a decline in cyclin B1, and subsequent apoptosis (31). Others have also found that some anticancer agents decrease the percentage of viable cells through induction of G2/M-phase cell cycle arrest associated with decreased levels of cyclin B1 complex in HL-60 cells (32). Studies by Xian et al. also support the correlation between decreases in cyclin B1 and CDK1, G2 cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis (33). Zerumbone, a natural cyclic sesquiterpene, significantly suppressed the proliferation of promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells by inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest associated with a decline of cyclin B1 protein and subsequent apoptosis (33).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that pancreatic cancer cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA were radioresistant compared to cells with functional mitochondrial electron transport chains. Depletion of mitochondrial DNA also suppressed radiation-induced G2 checkpoint activation that was accompanied by increases in both cyclin B1 and CDK1. Manipulations of pancreatic cancer cell mitochondrial function may have a role in radiation-induced cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants CA115785 and CA111365, the Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Susan L. Bader Foundation of Hope.

References

- 1.Girdhani S, Bhosle SM, Thulsida SA, Kumar A, Mishra KP. Potential of radiosensitizing agents in cancer chemo-radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2005;3:129–131. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.19585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittgen HG, Van Kempen L. Reactive oxygen species in melanoma and its therapeutic implications. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:400–409. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f1d312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamura S, Takai D, Watanabe K, Hayashi J, Hayakawa K, Akashi M. Role of mitochondrial DNA in cells exposed to irradiation: generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is required for G2 checkpoint upon irradiation. J Health Sci. 2005;51:385–393. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elledge SJ. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science. 1996;274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan KA, El-Naggar AK, Soria J, Liu D, Hong WK, Mao L. Clinical significance of cyclin B1 protein expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2458–2462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Y, Zhao C, Dong L, Fu M, Xue L, Huang Z, Tong T, Zhou Z, Chen A, Zhan O. Overexpression of cyclin B1 in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) cells induces tumor cell invasive growth and metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:307–315. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarsour EH, Venkataraman S, Kalen AL, Oberley LW, Goswami PC. Manganese superoxide dismutase activity regulates transitions between quiescent and proliferative growth. Aging Cell. 2008;7:405–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon SG, Sarsour EH, Kalen AL, Venkataraman S, Hitchler MJ, Domann FE, Oberley LW, Goswami PC. Superoxide signaling mediates N-acetyl-l-cysteine-induced G1 arrest: regulatory role of cyclin D1 and manganese superoxide dismutase. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6392–6399. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaquero EC, Edderkaoul M, Pandol SJ, Gukovksy I, Gukovskaya AS. Reactive oxygen species produced by NAD(P)H oxidase inhibit apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34643–34654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullen JJ, Hinkhouse MM, Grady M, Gaut AW, Liu J, Zhang YP, Darby-Weydert CJ, Domann FE, Oberley LW. Dicumarol inhibition of NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase induces growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer via a superoxide-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5513–5520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo G, Yan-Sanders Y, Lyn-Cook BD, Wang T, Tamae D, Ogi J, Khaletskiy A, Li Z, Weydert C, Li JJ. Manganese superoxide dismutase-mediated gene expression in radiation-induced adaptive responses. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2362–2378. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2362-2378.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epperly MW, Gretton JE, Sikora CA, Jefferson M, Bernarding M, Nie S, Greenberger JS. Mitochondrial localization of superoxide dismutase is required for decreasing radiation-induced cellular damage. Radiat Res. 2003;160:568–578. doi: 10.1667/rr3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delsite RL, Rasmussen LJ, Rasmussen AK, Kalen A, Goswami PC, Singh KK. Mitochondrial impairment is accompanied by impaired oxidative DNA repair in the nucleus. Mutagenesis. 2003;18:497–503. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geg027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu AX, Clark JW, Willett CG. Adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer: an evolving paradigm. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2004;13:605–620. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan MF, Kattan MW, Klimstra D, Conlon K. Prognostic nomogram for patients undergoing resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2004;240:293–298. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133125.85489.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Pancreatic cancer. Curr Prob Surg. 1999;36:59–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artinyan A, Hellan M, Mojica-Manosa P, Chen YJ, Pezner R, Ellenhorn JD, Kim J. Improved survival with adjuvant external-beam radiation therapy in lymph node-negative pancreatic cancer: a United States population-based assessment. Cancer. 2008;112:34–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazard L, Tward JD, Szabo A, Shrieve DC. Radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results of a study from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data. Cancer. 2007;110:2191–2201. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muschel RJ, Zhang HB, Iliakis G, McKenna WG. Cyclin B expression in HeLa cells during the G2 block induced by ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5113–5117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakkar P, Singh BK. Mitochondria: a hub of redox activities and cellular distress control. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;305:235–253. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Kolluri SK, Gu J, Dawson MI, Cao X, Hobbs PD, Lin B, Chen G, Lu JS, Zhang X. Cytochrome C release and apoptosis induced by mitochondrial targeting of nuclear orphan receptor TR3. Science. 2000;289:1159–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Den BC, van Kernebeek G, de Leig L, Kroon AM. Inhibition of mitochondrial protein synthesis leads to proliferation arrest in the G1-phase of the cell cycle. Cancer Lett. 1986;32:41–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(86)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong JS, Hornung B, Lecane P, Jones DP, Knox SJ. Rotenone-induced G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in a human B lymphoma cell line PW. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:973–978. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King MA, Radicchi-Mastroianni MA. Antimycin A-induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells. Cytometry. 2002;49:106–112. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Den BC, Spelbrink JN, Dekker HL. Relationship between culture conditions and the dependency on mitochondrial function of mammalian cell proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 1992;152:632–638. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041520323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hapala L. Growth defects in intramitochondrial energy depleted cells: role of mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:612–617. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gemin A, Sweet S, Preston TJ, Singh G. Regulation of the cell cycle in response to inhibition of mitochondrial generated energy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:1122–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernhard EJ, Maity A, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG. Effects of ionizing radiation on cell cycle progression. A review. Radiat Environ Biophys. 1995;34:79–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01275210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cariveau M, Kovacs C, Allison R, Johnke RM, Kalmus GW, Evans M. The expression of p21/WAF-1 and cyclin B1 mediate mitotic delay in x-irradiated fibroblasts. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1123–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin S, Chueh S, Hsiao C, Li T, Chen T, Liao C, Lyu P, Guh J. Prazosin displays anticancer activity against human prostate cancers: targeting DNA and cell cycle. Neoplasia. 2007;9:830–839. doi: 10.1593/neo.07475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo H, Chang L, Lin Y, Lu HF, Yang JS, Lee JH, Chung JG. Morin inhibits the growth of human leukemia HL-60 cells via cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis through mitochondria dependent pathway. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xian M, Ito K, Nakazato T, Shimizu T, Chen C, Yamato K, Murakmi A, Ohigashi H, Ikeda Y, Kazaki M. Zerumbone, a bio-active sesquiterpene, induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in leukemia cells via a Fas- and mitochondria-mediated pathway. Cancer Science. 2007;98:118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]