Abstract

Classic and contemporary approaches to the assessment of female sexuality are discussed. General approaches, assessment strategies, and models of female sexuality are organized within the conceptual domains of sexual behaviors, sexual responses (desire, excitement, orgasm, and resolution), and individual differences, including general and sex-specific personality models. Where applicable, important trends and relationships are highlighted in the literature with both existing reports and previously unpublished data. The present conceptual overview highlights areas in sexual assessment and model building that are in need of further research and theoretical clarification.

Research in female sexuality is fractionated. Significant contributions in specific areas, such as assessment, treatment, or understanding sexual phenomena have not necessarily led to offshoot contributions in related areas. Mirroring the field of human sexuality, the study of women’s sexuality has lacked an overarching conceptual basis with which to compare, evaluate, and guide ongoing research; hence, to significantly advance sexual science, it has been suggested that we must develop comprehensive theories and constructs that describe, explain, and predict sexual phenomena (Abramson, 1990). The present contribution discusses issues in the assessment of female sexuality from the organizational framework of concepts rather than measures. Here, we provide information on classic and contemporary approaches, and the discussion is framed within the conceptual domains of sexual behaviors, sexual responses (i.e., the sexual response cycle), and individual differences.

An unprecedented number of sexual behavior studies have been conducted in response to the HIV–AIDS crisis (see Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990, for a review). However, research on the assessment of female sexual behavior, exclusive of behaviors that lead to increased HIV risk, remains limited (but see sex survey of Laumann et al. from the University of Chicago; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). The coverage is most complete for heterosexual behaviors. This is not an intentional bias, and we acknowledge the dearth of data on sexuality topics for lesbians.

We regard a sexual response cycle conceptualization, specifically desire, excitement, orgasm, and resolution, as an important second component in a working model of female sexuality. Although there are significant and important interrelationships among the phases, there are sufficient data to suggest that each has unique aspects, too. The separate elaboration of the phases may also clarify the female sexual dysfunctions, as the majority of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnoses are now conceptualized according to phasic disruption. As we consider assessment of each phase, we consider four “channels” for assessment: physiological, cognitive, affective, and behavioral.

The resurgence in personality research in the past decade (see Goldberg, 1993, for an interesting historical discussion) and our own line of cognitive research compels us to examine the role of individual differences in women’s sexuality. Here we discuss the contemporary organization of personality structure, the Big Five model, as well as sexually relevant personality factors, such as sexual self-schema.

Sexual Behavior

In the United States, the first large-scale study of sexual behavior was that by Kinsey and his colleagues (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953). Their efforts, however, were predated by Terman’s (Terman, Buttenwieser, Ferguson, Johnson, & Wilson, 1938) more focused analysis of sexual behaviors, practices, and preferences in the context of marriage. Terman was specifically interested in the role of a couple’s sexual relationship in their marital adjustment and headed one of the first research groups to study in detail such aspects as the frequency of intercourse, relative “passionateness” of the spouses, refusal of intercourse, orgasm, duration of intercourse, the wife’s response to first intercourse, contraceptive practices, the wife’s desire, and each individual’s sexual complaints about the other. In the Kinsey interviews, conducted with thousands of women and men, the focus was similar, yet with a life-span orientation. They included the following: preadolescent heterosexual and homosexual play; masturbation; nocturnal sex emissions and dreams; heterosexual petting; premarital, marital, and extramarital coitus; intercourse with prostitutes (for men only); homosexual contacts; animal contacts; and, finally, the total sexual outlet, defined as the sum of the various activities which culminated in orgasm. Other topics that are now recognized as important to sexual development (and perhaps the subsequent occurrence of sexual dysfunctions), such as incest and other traumatic sexual experiences, received less coverage.

In addition to the significant public attention that the Kinsey volumes received, it is clear that their behavior chronicle interview is one of the few examples of a method affecting the nature of sex research for decades. It was mirrored, for example, in the late 1950s to the early 1970s with investigators including Podell and Perkins (1957), Brady and Levitt (1965), and Zuckerman (1973) publishing listings of heterosexual behaviors for men and women. The scales consisted of 12 to 20 items and included experiences that ranged from kissing to intercourse or mutual oral stimulation. Undergraduates were typically the research participants—an unusually relevant group because one aspect of these studies was to provide an ordinal (Guttman) scaling of the items. These data suggest, in part, a hierarchical or chronological ordering of sexual experiences. This is nicely illustrated by Peter Bentler’s (1968) 21-item experience scale. Years later, this method continues to appear in assessment and therapy arenas. For example, omnibus sexual functioning inventories, such as the Sexual Interaction Inventory by LoPiccolo and Steger (1974), include the same hierarchical listing of sexual behaviors for each of its 11 scales. Such orderings also provide an empirical basis for generic hierarchy construction in systematic desensitization therapy studies (see Andersen, 1983, for a review).

To illustrate scales of this sort, we provide data in Table 1 for the 24 items from the Sexual Experience Scale of the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1979). Rather than use the Derogatis yes–no format for scoring, we asked 172 undergraduate women (mean age, 19.3 years) to complete two versions of the scale. On the first assessment (previous scoring), they indicated whether they had ever experienced the activity. We have used such a scoring as an indicator of a woman’s sexual history, as scores would range from 0 to 24 and quantify the range of heterosexual behaviors that had been experienced in one’s lifetime (e.g., Andersen & Jochimsen, 1985). As indicated in the far left column of Table 1, a hierarchical ordering of the items can be determined. In large part, comparison of the ordering with the much earlier Bentler data (1968) is similar, with the addition of the items masturbation, anal intercourse, and anal stimulation on the low-frequency end of the listing. Also of note is male-initiated or male-dominated versions of many of the items preceding the female counterpart items (e.g., intercourse with male “on top,” 71%, vs. intercourse with female “on top,” 68%; oral stimulation of one’s genitals by partner, 72%, vs. oral stimulation of partner’s genitals, 70%). These trends are consistent with gender differences found in the frequency of oral sex, as reported in the most recent comprehensive sex survey (e.g., 77% of men vs. 68% of women reported engaging in active oral sex at least once in their lifetime; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). On the second assessment, women indicated their frequency of behaviors in the past 30 days on a scale ranging from 0 (activity did not occur) to 9 (activity occurred two or more times per day) for each item. As might be expected, data for the present scoring reflect the previous scoring hierarchical ordering. We have also found that use of frequency rating scales rather than dichotomous presence–absence scoring provides greater sensitivity when the purpose is to assess behavior change or group differences (see Andersen & Broffitt, 1988, for a discussion).

Table 1.

Sexual Experience Scale for Previous and Current Scoring for College-Age Women (N= 172)

| Previous scoring | Current scoring | SES item |

|---|---|---|

| 12.3 | 0.05 | Anal intercourse |

| 33.1 | 0.8 | Caressing your partner’s anal area |

| 34.9 | 0.7 | Masturbating alone |

| 44.2 | 0.9 | Intercourse: side by side |

| 45.3 | 1.0 | Having your anal area caressed |

| 52.3 | 1.1 | Intercourse: vaginal entry from rear |

| 55.8 | 1.2 | Intercourse: sitting position |

| 63.9 | 1.8 | Mutual petting of genitials or orgasm |

| 67.4 | 1.7 | Mutual oral (mouth) stimulation of genitals |

| 67.8 | 2.1 | Intercourse: female “on top” position |

| 70.3 | 2.0 | Oral stimulation of your partner’s genitals |

| 71.3 | 2.7 | Intercourse: male “on top” position |

| 72.1 | 1.9 | Having your genitals orally stimulated |

| 79.7 | 2.8 | Mutual undressing of each other |

| 81.3 | 3.2 | Breast petting while you are nude |

| 86.0 | 3.3 | Stroking and petting your sexual partner’s genitals |

| 87.8 | 3.4 | Having your genitals caressed by your partner |

| 88.9 | 3.4 | Your partner kissing your nude breasts |

| 88.9 | 3.7 | Erotic embrace while dressed |

| 90.7 | 4.1 | Kissing of sensitive (nongenital) areas of the body |

| 91.1 | 4.0 | Your partner lying on you while you are clothed |

| 93.0 | 3.6 | Breast petting while you are clothed |

| 95.9 | 4.8 | Deep kissing |

| 98.8 | 5.6 | Kissing on the lips |

Note. For the previous scoring, items were scored 0 (never experienced in my lifetime) and 1 (experienced at least once in my lifetime). Values are percentages of women in the sample who endorsed each item as having been experienced at least once. For the current scoring, the following scale was used for the frequency of each behavior in the past 30 days: 0 = this activity did not occur, 1 = activity occured once, 2 = activity occurred twice, 3 = activity occurred three times, 4 = activity occurred four times, 5 = activity occurred five times, 6 = once a week, 1 = two to six times a week, 8 = once a day, and 9 = two or more times a day. SES = Sexual Experience Scale.

Despite the usefulness of such scales, questions have been raised about the reliability and validity of any method that uses self-reports of sexual behavior. Rather than discuss them here, we refer the reader to reviews of these issues (e.g., Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990; Morokoff, 1986). Methodologic problems notwithstanding, further research efforts are needed to clarify which variables constitute the domain of women’s sexual behavior. The behavior listings noted earlier may provide a useful starting point. For example, in an earlier report we provided a factor-analytic study of the Sexual Experience Scale from the DSFI (Andersen & Broffitt, 1988). Responses were obtained from nonstudent, “older” women (mean age, 41 years; range, 21 to 65 years). Women rated each item in a yes–no format, indicating whether the activity had occurred in the previous 3 months. A five-factor principle components solution that accounted for 82% of the variance was selected as the best fit for the data. Inspection of the factor loadings indicated that the items fell into the following subgroups: (a) masturbation (7% of the variance); (b) arousing activities, the majority of which occurring while clothed, including kissing with tongue contact, erotic embraces, breast fondling, and undressing (22% of the variance); (c) intimate activities, the majority of which occurring while unclothed, including kissing of breasts and other parts of the body and manual and oral genital stimulation (23% of the variance); (d) intercourse position items (13% of the variance); and (e) anal stimulation and anal intercourse (16% of the variance). We have since replicated this factor solution with the sample of 172 undergraduate women who provided the data in Table 1. Data from the previous scoring was submitted to a principal-axis factor analysis with an oblique Harris-Kaiser rotation. The solutions are identical with one exception: items from groupings (b) and (c) combine to form a single factor, with the oral-genital stimulation items forming a second, separate factor.

As any factor solution is dependent on the items represented, these are unique to the items included by Derogatis and the participants in the samples described. However, if comparison is made between these Derogatis items and those in the scales noted earlier, one finds significant overlap, 100% with the Zuckerman (1973) and 86% with the Bentler (1968) measures, for example, and often the exact wordings for the items are used. The notable additions by Derogatis to the earlier behavioral scales were items assessing masturbation and anal stimulation. In summary, these analyses suggest that behavioral listing measures may provide a reasonable sampling of the sexual behavior domain for adult heterosexual women. Furthermore, careful selection of rating scales for such listings may provide useful indicators for women’s heterosexual behavior repertoires and estimates of current sexual activity.

Sexual Response Cycle

As noted by Rosen and Beck, there is “a fundamental assumption underlying most conceptualizations of sexual response [and that is that] sexual arousal processes are likely to follow a predictable sequence of events, and that a cyclical pattern of physiological responding can potentially be identified” (1988, p. 25). However, there has been disagreement about the number and importance of each phase. Although popularized by Masters and Johnson (1966), the concept of stages of sexual engagement has early origins. As summarized in Table 2, the number of stages has ranged from two to four. The phases of desire, plateau, and resolution are inconsistently represented, whereas a two-dimensional model of arousal–excitement process and an orgasm or orgasm–immediate postorgasm phase has been consistent. Historically, researchers have focused on understanding excitement (or sexual arousal), but more recently there has been similar emphases on defining the psychological and behavioral boundaries of sexual desire.

Table 2.

Historical Models of the Sexual Response Cycle

| Study | Description |

|---|---|

| Ellis (1906) | Two-stage process: Tumescence and detumescence |

| Masters & Johnson (1966) | Four-stage model: Excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution |

| Zuckerman(1971) | Two-stage model: Arousal as a parasympathetic process and orgasm as a sympathetic process |

| Kaplan (1977, 1979) | Triphasic model: Desire, excitement, and orgasm |

We combed the literature to find assessment strategies for these four dimensions, yet there are few that follow this comprehensive conceptualization. In fact, Masters and Johnson’s (1966) widely publicized findings appear to have had minimal impact when it comes to assessing sexual responding in clinical samples. Even their own assessment strategy—a lengthy oral interview described in the 1970 book—has little continuity with the 1966 model. In articles and chapters by researchers, a functional analysis of the antecedents, problem behaviors, and consequences of the particular sexual difficulty is most common. Although the latter is very useful, one may not necessarily obtain information about all phases of the sexual response cycle. Whereas our efforts have concentrated on such a measure (e.g., Andersen, Anderson, & deProsse, 1989), others have either developed phase-specific measures or multidimensional inventories (e.g., body image, sexual satisfaction, sexual roles, etc.; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1979; LoPiccolo & Steger, 1974).

Sexual Desire

A decade after Masters and Johnson’s (1966) formulation proposing sexual excitement as the first phase of the response cycle, Kaplan (1979) and Lief (1977) asserted an expanded model that began with sexual desire, and the term inhibited sexual desire was coined for individuals who chronically failed to initiate or respond to sexual cues (Lief, 1977). What is sexual desire? Current theories range from purely dynamic models to ones that emphasize biologic factors. Kaplan (1979), in her influential volume, Disorders of Sexual Desire, reiterated the psychoanalytic position of libido as an innate emotional force that would be expressed in either sexual or nonsexual outlets. It would follow, then, that any inhibition of desire would be due to the unconscious repression or conscious suppression of urges for sexual contact. In either case, such defenses would arise from intrapsychic conflicts surrounding sexuality.

There are interactional models of desire and ones that emphasize other, nondynamic, psychological processes (see also a discussion by Beck, 1995). Levine (1992), for example, highlights the role of sexual drive, seen as a biologically based source, and the individual’s behavioral and cognitive efforts to seek sexual stimulation. In contrast, Singer and Toates (1987) offer a central-nervous-system-mediated motivational model. They propose that sexual motivation, like hunger or thirst, emerges from an interaction of external incentives (i.e., a sexual stimulus) and internal states (e.g., sexual deprivation). Leiblum and Rosen (1988) note both intrapsychic and interpersonal aspects, but they define sexual desire functionally (i.e., desire is both a setting event and a consequence of sexual activity. Finally, Hatfield relies on her rich conceptualization of passionate love for the context of sexual desire; she sees sexual desire as a psychological longing for sexual union that is tied to sexual satisfaction and interpersonal relationship satisfaction (i.e., love) for the partner (Hatfield & Rapson, 1987; Traupman, Eckels, & Hatfield, 1982).

Biologic models of sexual desire are controversial and currently emphasize hormonal mechanisms. Data are most consistent for the necessary (but not sufficient) role of androgens, probably testosterone. For this model, the majority of supporting data comes from men (e.g., O’Carroll, Shapiro, & Bancroft, 1985). Bancroft (1988) proposes that the occurrence of spontaneous erections during sleep are the behavioral manifestations of the androgen-based neurophysiological substrate of sexual desire; in contrast, erections with fantasy or erotic visual cues are seen as evidence for androgen-independent responses.

Hormone–sexual behavior relationships for women are less clear, although estrogen, progesterone, and androgen (testosterone) have been studied. Regarding estrogen effects, it is clear that some amount of estrogen is necessary for normal vaginal lubrication, and receipt of estrogen replacement therapy after menopause may reduce the problematic symptoms (e.g., lack of lubrication, atrophic vaginitis) and allow sexual activity or functioning to proceed unimpaired (Walling, Andersen, & Johnson, 1990). In contrast, progesterone may actually have an inhibitory effect (Bancroft, 1988). Finally, testosterone may have direct effects on sexual functioning; both Bancroft and Wu (1983) and Schreiner-Engel, Schiavi, Smith, and White (1982) have found positive relationships between testosterone levels and frequency of masturbation and vaginal responses to erotic stimuli. In studies of women for whom estrogen therapy was not effective for postmenopausal symptoms, testosterone administration improved sexual desire and related outcomes (Burger et al., 1984; Studd et al., 1977). Perhaps the most direct data on this topic are by Alexander and Sherwin (1993). In studying 19 oral contraceptive users, they reported that plasma levels of free testosterone was correlated with self-report measures of sexual desire, sexual thoughts, and anticipation of sexual activity. However, an interesting and more direct test of the hypothesis that testosterone is related to sexual cognitions was disconfirmed; using a selective attention (dichotic listening) task, Alexander and Sherwin found no relationship between levels of free testosterone and an attentional bias for sexual stimuli. Finally, a clinical study by Schreiner-Engel, Schiavi, White, and Ghizzani (1989) is relevant. They compared 17 women who met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., revised; DSM–HI–R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) criteria for loss of desire with 13 healthy, sexually active women. Blood samples were drawn every 3–4 days for one menstrual cycle and were analyzed for testosterone, estradiol, progesterone, prolactin, and luteinizing hormone. No differences between the groups were found, and subgroup analyses (e.g., comparison of women with lifelong absence of desire vs. those with acquired loss of desire) were also disconfirming. At present, it is unclear whether physiologic measures, and hormonal assays in particular, are useful physiologic indicators of sexual desire.

Considering the other channels for assessment, cognitions have been emphasized. For example, in DSM definitions (both DSM–III–R and the fourth edition [DSM–IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994]), there is little suggestion of the theoretical models discussed earlier or of any specific physiologic or affective markers (other than generic psychologic distress). Instead, a circular statement (i.e., that hypoactive desire is deficient desire) is linked to a cognitive symptom—the absence of sexual fantasy. Correlational data suggest that, in general, individuals distressed about their sexual functioning report fewer spontaneous sexual fantasies, a higher likelihood that sexual fantasy will generate concomitant feelings of sexual guilt, and that they may prematurely terminate their fantasizing (Zimmer, Borchardt, & Fischle, 1983). A comparison of women diagnosed with inhibited sexual desire and nondysfunctional women has revealed that women with desire problems fantasized less during a variety of sexual activities, including foreplay, coitus, and masturbation (Nutter & Condron, 1983). Epidemiologic data indicate that women use sexual fantasies to increase sexual desire and facilitate orgasm (Lunde, Larsen, Fog, & Garde, 1991). Not surprisingly, fantasy does play an important role in sex therapies (e.g, directed masturbation, systematic desensitization). Although these lines of data suggest some importance to the role of fantasy, there are not data at present suggesting that the absence of fantasy is pathognomic for low sexual desire.

Data comparing the frequency of internally generated thoughts (fantasies) and externally prompted thoughts (sexual urges) among young heterosexual men and women indicate that men report a greater frequency of urges than do women (4.5/day vs. 2.0/day), although the frequency of fantasies were similar (2.5/day; Jones & Barlow, 1990). Related data from Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, and Michaels (1994) indicate a normal distribution in the frequency of autoerotic activities (e.g., fantasy, masturbation, use of erotica) among women, with an elevated flat distribution for men. This indicates that, on average, men have higher rates of autoerotic activities and that there is less variance among men; for women, this indicates that, on average, women have generally lower rates but there are more individual differences among women in the frequency of autoerotic activity. Regarding the specific content of women’s fantasies, the data of Ellis and Symons (1990) suggest that touching, partner responses, and emotional responses may be important, in contrast to the characterization of men’s fantasies, which emphasizes visual imagery of the sexual partner or the sexual act.

There are self-report measures of sexual fantasy. Wilson’s (1988) 40-item measure includes four topical areas: exploratory (e.g., group sex, swapping items), intimate (e.g., heterosexual behaviors), impersonal (e.g., sex with strangers), and sadomasochistic fantasy topics (e.g., forced sex, whipping). Correlation analyses reveal that higher self-reported levels of sex drive are correlated with more frequent sexual fantasies, particularly intimate fantasies for women (e.g., r = .49 for women vs. .05 for men). There is also a 20-item fantasy scale on the DSFI; however, there are few psychometric data on this scale. Snell and Papini (1989; see also Snell, Fisher, & Schuh, 1992) have developed a measure of sexual preoccupation, or the tendency to think about sex to an “excessive degree.” This is a 10-item subscale from the Sexuality Scale on which an individual endorses frequent thoughts, fantasies, and daydreams about sex (e.g., “I think about sex a great deal of the time,” “I hardly ever fantasize about having sex”). Internal consistency of the measure is high (.88–.91) and 4-week test–retest is adequate (.70–.76). There are few convergent and discriminant data, but they are supportive. The measure is positively correlated but not overlapping with Byrne’s (1983) measure of erotophilia (.32) and negatively correlated with measures of sexual anxiety (−.36) and sexual guilt (−.22). Measures such as these may be useful to assess sexual cognitions. Other techniques exist (see Cacioppo & Petty, 1981, for thought listing procedures) yet have not been used in sexuality research, despite their usefulness in the areas of social cognition and cognitive therapy research. When such measures are not used, researchers often use proxy variables. One strategy has been to have participants rate their sexual desire and then correlate these data with other indicators, such as sexual arousal or behavior (e.g., Beck, Bozman, & Qualtrough, 1991).

Provided below are symptom descriptions of individuals complaining of low desire. These may provide useful phenomenologic information for future assessment research. Specifically, we note the following.

Individuals with low desire report that they are generally uninterested in sexual activity. Such an attitude can be manifest behaviorally by never initiating sexual contact, avoiding sexual contexts, or refusing a partner’s initiations. These behaviors are presumably not due to strong negative responses to interpersonal or genital contact, an important point to consider when ruling out alternatives, specifically a sexual aversion disorder (see Discussion; for an early example of the absence of distinction, see McCarthy, 1984). Instead, individuals with low desire disorder are thought to be indifferent or neutral toward sexual activity. Sexual urges seem not to occur.

Individuals with low desire may report no sexual cognitions—fantasies or other pleasant, arousing sexual thoughts and mental images.

In terms of self-descriptions, individuals with low desire may have an asexual self-view.

Disruption in the frequency, focus, intensity, or duration of sexual activity may occur, and secondary disruption of sub sequent response cycle phases may occur.

Sexual Excitement

Either physical or psychologic sexual stimulation can initiate sexual excitement. The bodily changes with sexual excitement are considerable. The general physiologic responses are widespread vasocongestion, either superficial or deep, and myotonia, with either voluntary or involuntary muscle contractions. Other changes include increases in heart rate and blood pressure and deeper, more rapid respiration. For women, sexual excitement is also characterized by the appearance of vaginal lubrication, produced by vasocongestion in the vaginal walls, leading to transudation of fluid. Other changes include a slight enlargement of the clitoris and uterus with engorgement. The uterus also rises in position with the vagina expanding and ballooning out. Maximal vasocongestion of the vagina produces a congested orgasmic platform in the lower one third of the vaginal barrel. As discussed later, individuals may not be aware of the physiologic sensations of arousal; even if they are, their affects may or may not be convergent. Thus, in the following discussion, we consider both positive affects, such as arousal, and negative affects, such as anxiety, which may relate to sexual excitement. Consideration of negative affects is relevant as some (e.g., anxiety) are key in theoretical models of sexual excitement difficulties or dysfunctions.

Arousal and other positive emotions

Studies have addressed the physiological and affective aspects of arousal. Although the aforementioned description notes vasocongestion and lubrication as the predominant bodily responses, psychophysiological research has consisted largely of measures of vaginal vasocongestion (i.e., vaginal pulse amplitude [VPA], vaginal blood volume [VBV]) using the vaginal plethesmograph. Other genital measurements (such as those for lubrication) have not emerged, are unreliable, or are not sensitive to changes in arousal (see Geer & Head, 1990, for a review). As a physiological indicator of sexual arousal, it is still unclear what these vaginal signals represent and whether they are analogues of distinct vascular processes (Levine, 1992). However, there is evidence for their convergent validity. For example, VPA and VBV are capable of detecting group differences (e.g., differences in as absolute levels of arousal between women with and those without sexual dysfunctions), and responsiveness to experimental conditions (e.g., novel exposure and habituation to erotic stimuli, contrasts between erotic vs. nonerotic stimuli; Meuwissen & Over, 1990; Heiman, Rowland, Hatch, & Gladue, 1991; Laan, Everaerd, van Bellen, & Hanewals, 1994). Of the two measures, a variety of data suggest that VPA is the more sensitive and reliable genital measure, particularly because of its insensitivity to anxiety-evoking stimuli (Lann, Everaerd, & Evers, in press).

The construct of arousability is central to understanding cognitive and affective aspects of sexual excitement in women. According to Bancroft (1989), arousability is a cognitive sensitivity to external sexual cues. He suggests that high arousability implies enhanced perception, awareness, and processing of not only sexual cues but the bodily responses of sexual excitement. This model seeks to connect cognitive–affective responses with control of genital and peripheral indications of sexual excitement through a neurophysiological substrate for sexual arousal. Fortunately, one of the psychometrically strongest self-report measure for female sexuality is one that also taps sexual arousability, the Sexual Arousability Index (SAI) by Hoon, Hoon, and Wincze (1976). On this 28-item measure, women rate their sexual arousal for a variety of erotic and explicit sexual behaviors. Both the clinical usefulness and the power of the instrument are likely due to the important steps that were taken in the scale construction and validation process, including selecting items that evidenced convergent validity with criterion variables such as women’s awareness of physiological changes during sexual arousal (e.g., vaginal lubrication, nipple erection, sex flush, breast swelling, muscular tension), ratings of satisfaction with responsiveness, and sexual behavior measures. The measure samples a range of individual and partnered erotic and sexual behaviors; our psychometric studies indicate that the SAI samples the following domains: arousal associated with erotica (e.g., literature or photography) and masturbation, seductive activities (e.g., passionate kissing, being undressed), body caressing by a male partner, oral-genital and genital stimulation, and intercourse (Andersen, Broffit, Karlsson, & Turnquist, 1989).1

Although there is the expectation that physiologic measures, behavioral reports, and subjective reports converge, examples of dyscrony are common (see Turpin, 1991, for a discussion of assessment of anxiety disorders), so too in this area, reports are mixed. Significant correlations have been found between genital measures and women’s ratings of their general arousal (e.g., Morokoff, 1985; Palace & Gorzalka, 1992; Laan, Everaerd, & Evers, in press), yet low-to-zero correlations have been found between genital measures and women’s ratings of genital arousal (e.g., warmth in the genitals, lubrication; Laan, Everaerd, & Evers, in press; Palace & Gorzalka, 1992). In the Laumann et al. survey, 19% of the female sample reported difficulties with lubrication, but only 12% of women reported anxiety about performance (Lauman, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Other relevant data indicate that the magnitude of the correlations may be moderated by individual differences among women, such as indications of their sexual responsiveness. For example, Adams, Haynes, and Brayer (1985) found that “infrequently” orgasmic women showed a differential tendency to respond to distracting stimuli; that is, they were less accurate in gauging their physiologic sexual response during a task that was distracting of sexual arousal than were “frequently” orgasmic women. Related examples of this phenomena have been reported by other investigators (Heiman, 1978; Morokoff & Heiman, 1980). At this time, there is insufficient data to draw a conclusion about the significance (or lack thereof) of this dysyncrony.

It may be useful to consider other positive affects or emotions that may influence sexual excitement–arousal. This examination provides a way to establish convergent and discriminant validity for the excitement construct. Researchers have found that positive mood, not surprisingly, accompanies sexual arousal in women (Heiman, 1980; Laan, Everaerd, van Bellen, & Hanewald, 1994).2 If an assessment question focuses on sexual excitement in the context of an interpersonal relationship, one of the more relevant emotions may be love. Walster and Berscheid (1974) proposed that people may be apt to experience love whenever they are intensely aroused physiologically (see Hatfield & Rapson, 1993, for a thorough discussion). People then label this arousal as love. A classic experiment provided evidence for this notion. Dutton and Aron (1974) had men (who were between 19 and 35 years old) walk across one of two bridges. One bridge was suspended over a deep gorge and swayed vigorously from side to side. The other bridge was much more stable and was much closer to the ground. Presumably, participants would be substantially more psychophysiologically aroused by crossing the swaying bridge than by crossing the stable one. As the men walked across the bridge, they were met by a research assistant, who was either male or female and who asked the participant to answer a few questions and to tell a story based on a picture. After the tasks were completed, the research assistant mentioned that if a participant wanted more information, he could call the assistant at home. Two important findings emerged. The first was that the stories of the participants (in response to a Thematic Apperception Test card) were highest in sexual imagery in the group that crossed the swaying bridge and met the female assistant. The second was that members of this condition were also the most likely to call the assistant at home, in some cases, even attempting to arrange another, more personal, meeting. These data have been interpreted as indicating that arousal, accompanied by a plausible labeling of the arousal as love (or at least attraction), seems to be one basis for passionate love (see Sternberg, 1987, for a related discussion). Although this experiment has not been replicated with women, it illustrates the general phenomena of positive affective labeling with sexual attraction, and possibly sexual arousal.

The 30-item Passionate Love Scale by Hatfield and Sprecher (1986) is reliable and evidences broad construct validity. Passionate love, defined as an intense longing for union with another, consists of three components: cognitive (e.g., intrusive thinking or preoccupation with the partner), emotional (attraction, and especially sexual attraction, for the partner), and behavioral aspects (e.g., efforts to maintain physical closeness to the partner, efforts to help the partner). The measure is correlated but not overlapping with relevant measures of sexual desire and excitement (e.g., interest in engaging in sex with the partner, .34; feelings of sexual excitement, .29 ([Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986]; ratings of sexual satisfaction, .42 [Traupmann & Hatfield, 1981]). Furthermore, women who have a positive view of themselves as sexual persons and their ability to become sexually aroused also report higher levels of passionate love and more romantic involvements (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994).

Negative affects that may impair excitement

Historically, anxiety has been the hypothesized mechanism in many theories of arousal deficits. Psychodynamic hypotheses emphasize fears of phallic-aggressive impulses, castration, rivalry, or incestuous object choices (Janssen, 1985). More central to contemporary views, Wolpe (1958) was the first to emphasize anxiety-based impairment of physiologic responses. In his view, the sympathetic activity characteristic of anxiety inhibits the local (i.e., genital) parasympathetic activity responsible for the initial phases of sexual excitement (i.e., erection for men and, presumably, lubrication and vasocongestion for women). Initially offered to explain male arousal deficits, the model has been applied less satisfactorily for women. There is little experimental support for the contention that the early phases of sexual arousal in women are primarily parasympathetic (Geer & Head, 1990) or even that anxiety will inhibit the physiologic responses of sexual arousal (although anxiety preexposure will effect verbal reports of subjective arousal; Palace & Gorzalka, 1990).

Dysfunctional attentional processes and negative affects have been the core of psychological theories of excitement deficits.3 Masters and Johnson (1970) proposed two components: “spectatoring” (i.e., attentional distraction as the individual “watches” for his or her sexual responding) and negative expectations that the bodily response (e.g., erection) will be inadequate. Anxiety about performance failure (i.e., the absence of the physiologic responses of excitement) then occurs. Again, male sexual responding is usually the exemplar for this model.

An overlapping, although more detailed, model is Barlow’s (1986; see also Beck, 1986). When a positive, functional sexual response (e.g., an erection) would be expected, men with sexual difficulties evidence physiologic, cognitive, and emotional characteristics that lead to erectile failure. For example, data indicate that men with erection difficulties underreport their levels of sexual arousal (relative to the magnitude of actual erectile response) if queried (Sakheim, Barlow, Abramson, & Beck, 1987), focus their attention on nonerotic rather than erotic cues (Abramson, Barlow, Beck, Sakheim, & Kelly, 1985), and report negative (depressed) feelings (Abramson, Barlow, Beck, Sakheim, & Kelly, 1985) and a lack of control over their sexual responses (Beck, Barlow, & Sakheim, 1982). This dysfunctional process is reiterated and “improved” (i.e., the dysfunctional individual becomes even more proficient at focusing on the wrong aspects of the sexual context— the consequences of not performing, the continuation of erectile insufficiency), and thus, the individual comes to avoid sexual contexts in the future.

The majority of data for Barlow’s (1986) model of anxiety and cognitive distraction comes from male participants. When the model has been examined, women (usually female undergraduates or, perhaps, women recruited from the community) representing “functional” and “dysfunctional” groups are tested in psychophysiology laboratories. Women are presented with stimuli, usually videotapes, representing anxiety-provoking, neutral, or erotic sequences. Vaginal measures, as well as self-reports of general or genital arousal, are recorded. In tests of the physiologic effects of anxiety, the data have, in general, indicated that genital arousal is not inhibited by anxiety. Using individualized, anxiety-provoking audiotaped scenarios, Beggs, Calhoun, and Wolchik (1987), for example, found that genital arousal (VBV) increased during the anxiety-provoking condition, although the levels were not as high as those achieved during an erotic verbal stimulus. Palace and Gorzalka (1990) found that preexposure with an anxiety-provoking videotape (e.g., a threatened amputation) in contrast to a neutral videotape facilitated VBV responses during subsequent viewing of erotic scenes for both women with and without sexual dysfunctions. This effect, preexposure to an anxiety-provoking stimulus increasing subsequent VBV during erotica, has also been replicated (Palace, in press). Other data disconfirming of both the Masters and Johnson and the Barlow conceptualizations is that by Laan, Everaerd, van Aanhold, and Rebel (1993). They found that VPA was higher (rather than lower) under experimental “demand” conditions (i.e., “Try to become as sexually aroused as possible within 2 min and try to maintain it for as long as you can. Your level of sexual arousal will be recorded”) in contrast no demand conditions. Taken together, these data suggest that these previous conceptualizations may be less relevant (if relevant at all) for women, as they substantiate neither the arousal processes (they may be predominately sympathetic rather than parasympathetic) nor hypothesized mechanisms (e.g., performance demand).

For these reasons, we consider anxiety as well as a broad band of other affects that may be relevant to discriminate from excitement processes for assessment. As an aside, we note that the DSM–IV gives no clues as to the direction of assessment and largely omits affective criteria for arousal disorder in women. Disruption of a predominant physiologic response (lubrication and swelling of the genitals) until the “completion of sexual activity” is regarded as pathognomic, and this disturbance needs to result in either “marked distress” or “interpersonal difficulty.”

Sexual anxiety, or related terms, has been used to name scales that differ considerably in content and intent. We also note that, rather than use previously published measures, many investigators commonly develop their own sexual anxiety scales by appending a rating scale (e.g., a scale ranging from 0 [no anxiety at all] to 6 [extremely anxious, nervous, or tense]) to a behavioral hierarchy such as the Bentler (1968) listing. A procedure not unlike the latter was E. Hoon’s (1978) modification of the SAI to the SAI— expanded version (SAI-E). She defined anxiety as a negative feeling of tension or nervousness and used the SAI items but changed the anchors for the rating scale (7-point Likert scale ranging from — 1 [relaxing] to 5 [extremely anxiety provoking]). Somewhat surprising is that in a validity study (Chambless & Lifshitz, 1984), the ratings for the SAI and the anxiety ratings on the SAI-E were uncorrelated but that the anxiety ratings were inversely correlated with reports of orgasm frequency (–.25). Factor analysis of the SAI-E (Chambless & Lifshitz, 1984) reveals a similar structure to that found with the SAI (Andersen, Broffitt, Karlsson, & Turnquist, 1989; see earlier discussion).

In contrast, the Sex Anxiety Inventory (Janda & O’Grady, 1980) defines anxiety as a generalized expectancy for nonspecific external punishment for the violation of, or the anticipation of violating, perceived normative standards of acceptable sexual behavior. This definition and the actual items for the measure are similar to Mosher’s (1965) Sex Guilt Scale, which assesses the expectancy for self-mediated punishment (rather than external). In fact, there is significant overlap between the measures (correlations of .67, or about 45% shared variance between the scales). Factor analysis indicates that the items of the two scales are intermingled across factors.

Some extreme, negative reactions have been termed sexual aversions. In the DSM–IV, sexual aversion is defined as persistent or recurrent extreme aversion to, and avoidance of, all or almost all, genital contact with a sexual partner. The behavioral reference of complete (or almost complete) absence of genital contact presumably signifies that all sexual activity is halted, and so the latter stages of the sexual response cycle would thus be circumvented. Aside from specific genital avoidance, there may be wide variation in the clinical pattern of avoidance. Some people proceed up to the point of genital exposure during sex, but others become so avoidant that there is generalization to many stimuli, however sexually vague or intrusive, that become labeled “sexual” and are thus avoided. From an assessment standpoint, aversion may be difficult to distinguish from anxiety with avoidance. At present, there are no experimental or clinical studies that have made the comparison.

Katz and his colleagues (Katz, Gipson, Kearl, & Kriskovich, 1989; Katz, Gipson, & Turner, 1992) developed a measure called the Sexual Aversion Scale (SAS), yet the content of the subscales differs from the aforementioned DSM description of sexual aversion. Thirty items are rated on a 4–point Likert scale and assess sexual fears associated with sexually transmitted diseases (primarily HIV), sexual guilt, negative social evaluation, pregnancy, and sexual trauma. Factor analyses suggest that the measure includes two domains that are potentially relevant to negative emotions disruptive of sexual excitement: sexual avoidance (e.g., “I have avoided sexual relations because of my sexual fears,” “I am not afraid of kissing or petting, but intercourse really scares me) and sexual self-consciousness and self-criticism (“I worry a lot about sex,” “I would like to feel less anxious about my sexual behavior,” “I feel sexually inadequate”). The other two factors assess fear of sexually transmitted disease (“The thought of AIDS really scares me”) and childhood sexual trauma (“I was sexually molested when I was a child”). Reliability data include estimates of .85 for internal consistency and .86–.89 for 4-week test-retest reliability. Few validity data are provided, but they are supportive in that the measure correlates .36 with the state and .44 with the trait forms of the Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Comparison of this measure with the SAI-E indicates that the SAI-E appears to tap anxiety, tension.and nervousness for sexual behaviors. In contrast, the SAS assesses self-reported avoidance of sexual activities and negative emotionality about sex, including worry, self-consciousness, and self-criticism. Although the former factor (sexual avoidance) may be related to sexual aversion as defined by DSM–III–R, it is not clear whether the latter factor (which appears to assess sexual neuroticism) is.

Orgasm

Masters and Johnson (1966) proposed that orgasm is a reflex-like response that occurs once a plateau of excitement has been reached or exceeded, although the specific neurophysiologic mechanisms are not known. The physiologic and behavioral indices of orgasm involve the whole body—facial grimaces, generalized myotonia of the muscles, carpopedal spasms, and contractions of the gluteal and abdominal muscles. For women, orgasm is also marked by rhythmic contractions of the uterus, the vaginal barrel, and the rectal sphincter, beginning at 0.8-s intervals and then diminishing in intensity, duration, and regularity. Attention is focused on internal bodily sensations (concentrated in the clitoris, vagina, and uterus), and one’s awareness of competing environmental stimuli may be lessened. The subjective experience of orgasm includes feelings of intense pleasure with a peaking and rapid, exhilarating release. These sensations are reported to be singular, regardless of the manner in which orgasm is achieved (Newcomb & Bentler, 1983). Women are unique in their capability to be multiorgasmic; that is, women are capable of a series of distinguishable orgasmic responses without a lowering of excitement between them.

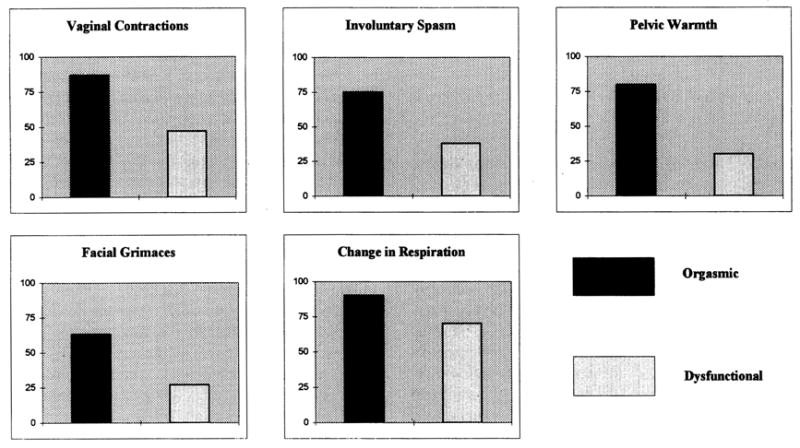

There are few assessment measures of orgasm. In fact, in the majority of research (e.g., Kelly, Strassberg, & Kircher, 1990; Raboch & Raboch, 1992), investigators simply ask women how consistently orgasm is achieved (e.g., 10% of the time or “rarely,” 70% of the time or “on most occasions”). There are unpublished measures (e.g., Warner, 1981), and one measure of attributions for orgasm consistency. The latter scale by Loos, Bridges, and Critelli (1987) assesses internal versus external and stable versus unstable attributions for regularity of orgasm during coitus. There are few supporting psychometric data, although the initial report for the measure suggests that it can discriminate between women of high and low orgasm consistency. In our research, we have assessed awareness of the physiological signs and symptoms of orgasm (e.g., Andersen, Anderson, & deProsse, 1989). We have found, for example, that women with and without orgasmic dysfunction differ on their awareness of orgasm signs (see Figure 1). These data replicate earlier research by Hoon and Hoon (1978) with a nondysfunctional sample. Their data indicated that women reporting the lowest orgasm consistencies were significantly less aware of physiological changes accompanying sexual arousal than women reporting higher consistencies of orgasm.

Figure 1.

Percentage of orgasmic and orgasmic dysfunction individuals reporting the occurrence of orgasm signs.

The lack of reliable and valid assessment methods for female orgasm may have contributed to the lack of clarity, heterogeneity, and controversy surrounding the criteria for female orgasmic dysfuntion (Morokoff, 1989; Wakefield, 1987). In the current DSM definition of female orgasmic disorder (in DSM–III–R, the label was inhibited female orgasm), it is defined as delayed or absent orgasm following an unimpaired sexual excitement phase. No subtypes are noted, although requiring that the excitement phase be unimpaired imposes a de facto subgroup. Historically, other distinctions have been made. For example, primary orgasmic dysfunction has been the designation for women who have never experienced orgasm under any circumstances (the possible exception might be an occasional orgasm during sleep with erotic dreams). Previous estimates suggested that 5%–10% of sexually active women have not experienced orgasm. In the Laumann et al. (1994) survey, only 29% of women reported that they always had an orgasm with their regular partner during sex and 24% reported an inability to have orgasm (Lauman, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). A second clinical pattern, called secondary orgasmic dysfunction, has been used for women who have orgasms but express concern with their frequency or circumstances of occurrence (e.g., orgasm may occur on a random basis or not with desired activities, such as coitus). For many women, this represents normal variation in sexual response patterns and is usually not appropriate as a diagnostic entity. In fact, the absence of coital orgasm is common for many adult women early in their sexual relationships, as the rate of coital orgasm slightly increases with experience (Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin & Gebhard, 1953). In the Laumann et al. survey (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994), 10% of women reported that they climaxed too quickly). Other clinical scenarios (e.g., a woman becoming nonorgasmic after being so) are rare. When this does occur, a history may reveal pharmacologic agents as instrumental; for example, anorgasmia in previously responsive women may be associated with the use of tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and neuroleptics.

As noted, the presumption of a normal sexual excitement phase describes a specific subgroup of women with orgasm difficulties, as previous research suggests that women presenting for treatment vary widely not only in their capacity for sexual arousal but in the presence of accompanying negative affects such as anxiety or aversion to sexual activity (Derogatis, Pagan, Schmidt, Wise, & Glidden, 1986; see Andersen, 1983, for a review). Thus, too, etiological hypotheses for inorgasmia have emphasized the role of anxiety or other distressing affects (Derogatis, et al., 1986; Wolpe, 1958), performance anxiety (Masters & Johnson, 1970), and skills deficits (Barbach, 1975). Hypotheses for coitally inorgasmic women often focus on the role of the interpersonal couple relationship (e.g., McGovern, Stewart, & LoPiccolo, 1975) or marital satisfaction.

Thus, contrary to the current DSM criteria, theoretical and intervention research suggests that subtypes of orgasmic dysfuntion may exist. If the response cycle conceptualization is considered, previous phases—desire and excitement—would both be expected to have linkages to the occurance of orgasm. For illustration, consider clinical cases of orgasmic dysfunction in which desire may or may not be regularly present, and excitement may or may not be regularly present (see Table 3). The consideration of the desire and excitement phases in the context of a presenting complaint of orgasmic dysfunction leads to the delineation of phasic-based subtypes, in this case, subtypes for orgasmic dysfunction. Hence, subtyping for assessment purposes is tied directly to the response cycle conceptualization.

Table 3.

Orgasmic Dysfunction Subtypes

| Desire phase dysfunction | Excitement phase dysfunction |

|

|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | |

| Absent | No orgasm | Neither excitement nor orgasm |

| Present | Neither desire nor orgasm | No desire, excitement, or orgasm |

To examine this conceptualization empirically, we inspected the range of sexual arousability and sexual anxiety scores (unfortunately, we did not collect data on desire) of women who presented for a treatment outcome study for primary orgasmic dysfunction (Andersen, 1981). When selecting women for study, we screened in for orgasmic dysfunction and screened out for dyspareunia, vaginismus, or medical problems. In terms of SAI scores for the women as they entered treatment, 70% of the women scored below the 50th percentile based on the Hoon, Hoon, and Wincze (1976) normative data, and, furthermore, 47% of the sample scored below the 25th percentile. Only 30% of the sample presenting for orgasmic dysfunction scored above the 50th percentile on the SAI, with only 7% of the sample above the 75th percentile. These data suggest that the numbers of nonorgasmic women who would report unimpaired sexual arousal (i.e., meeting DSM– IV criteria) would be very low. Furthermore, consideration of the relationship between orgasm and previous response cycle phases may provide useful assessment information for diagnostic and treatment purposes. In summary, it is probable that there are diagnostically distinct subgroups of women who have difficulty with orgasm.

Resolution

The concluding phase of the sexual response is resolution. After orgasm, the anatomic and physiologic changes of excitement reverse. In women, the orgasmic platform disappears as vasocongestion diminishes, the uterus moves back into the true pelvis, and the vagina shortens and narrows. A filmy sheet of perspiration covers the body and the elevated heart rate and respiration gradually return to normal. If orgasm has occurred, there are concomitant psychological sensations of bodily relaxation and feelings of release and sexual contentment–and satisfaction. If orgasm has not occurred, the same physiologic processes occur at a much slower rate, and the psychologic responses are usually either neutral or negative (e.g., continued sexual tension, disappointment at having not experienced orgasm). As described here, there have been few attempts to assess the state of resolution (but see Andersen, Anderson, & deProsse, 1989 as one example).

In contrast, there are measures that assess global evaluations of one’s sexual life or general satisfaction with sexuality, and as such, reflect a trait like view of resolution (P. M. Bentler, personal communication, October 4, 1994). For example, on the DSFI, there is a 10-item sexual satisfaction scale. Each item appears to assess a different aspect of satisfaction with the sexual life, including satisfaction with the frequency and range of sexual activities, communication with partner, the occurrence of orgasm, and resolution feelings. There are few psychometric data, but the available information is supportive. The internal consistency is .71, and the scale can distinguish from sexually dysfunctional and functional samples.

Conversely, Snell and Papini (1989) have developed a measure of sexual depression or the tendency to feel saddened and generally discouraged about one’s sexual life (e.g., “I feel down about my sex life”). Psychometric data for the scale are available (Snell, Fisher, & Schuh, 1992; Snell & Papini, 1989). Internal consistency is .88– .93 and 4-week test–retest reliability is .67 to .76. Validity data indicate that the measure appears to assess relevant aspects of depression, as it is correlated .25 with sexual guilt as assessed with the Janda and O’Grady (1980) measure and it is correlated .32 with the Beck Depression Inventory. In contrast, it is not correlated (—.05) with other negative sexual affects, such as erotophobia (Fisher, Byrne, White, & Kelley, 1988; see Discussion later).

Finally, we note the Sexual Interaction Inventory (LoPiccolo & Steger, 1974), which was designed as an omnibus measure for assessing sexual satisfaction and adjustment in heterosexual couples. In the past 20 years, reliability and validity data have accumulated for this measure; however, we note that the measure would be limited in the assessment of female sexuality per se. Briefly, the measure includes 17 heterosexual behaviors (modeled after the behavioral hierarchies discussed earlier) and a series of questions assessing such areas as satisfaction with the frequency, actual and preferred pleasure from the activity, and estimations of partner’s response.

Individual Differences

With two major exceptions (Freud and Eysenk), few researchers have explored the relationship between personality and sexuality. However, in the past decade there has been a resurgance of research in personality. Here we discuss the relationship between sexual behavior and the response domains and the contemporary general model of personality structure—the Big Five model—and sexually relevant personality factors, such as sexual self-schema.

General Factors

Historically, sexuality occupied a central role in psychology. Freud hypothesized that sexual instincts were the driving force in personality development, and sexual impulses gone awry were the etiological bases for psychopathology. Even later, neoanalysts and object relations theorists focused on the interrelationship between the capacity for sensuality and the development of stable, intimate relationships (Fairburn, 1952; Klein, 1976).

In the 1970s Eysenck (1971 Eysenck (1972), using his three-factor P-E-N model of personality, consisting of psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism, showed that personality and sexual variables were correlated. For example, women scoring high on neuroticism had lower reported levels of sexual experience, whereas those high on extraversion (particularly men) had much higher levels of sexual experience. These findings suggested that the negative emotionality characteristic of neuroticism (i.e., anxiety, guilt, and self-consciousness) would be a deterrant to sexual expression, whereas the positive emotionality characteristic of extraversion (i.e., dominance, sociability, exhibitionism, confidence, and excitement seeking) would be facilitative. Also, women scoring high on psychoticism reported greater involvement with coital and oral activities. Other studies of the Eysenck Psychoticism scale indicate that it is a blend of orthogonal Big-Five factors of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness (low A and low C; Goldberg & Rosolack, in press).

Costa and his colleagues (Costa, Fagan, Piedmont, Ponticas, & Wise, 1992) have used their measure of the Big Five, the NEO (Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness) Personality Inventory. They reported data from 163 women seeking outpatient treatment for sexual problems. Scores on the DSFI (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1979) and the NEO Personality Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1985) were reported. Women seeking treatment for sexual dysfunction and scoring high on neuroticism (particularly subscales endorsing higher anxiety or depression and self-consciousness) reported lower levels of sexual information (—.19) and poorer body image (.28). Conversely, women scoring higher on openness (individuals who seek out and appreciate varied experiences) reported higher levels of sexual information (.38), higher levels of sexual activity (.26), and a more positive body image (–.20.). No significant correlations were found with the other personality scales (i.e., Extraversion, Agreeableness, or Conscientiousness scales) and the remaining sexuality scales (sexual experience, sexual satisfaction). Other studies with a smaller sample have also failed to find a significant correlation between extraversion and sexuality for women (see Jupp & McCabe, 1989, for sexual arousability, or Harris, Yullis, & LaCoste, 1980, for relationship with coital frequency). In comparison, extroversion is a strong, broad band predictor of sexual behaviors and affects for men (Costa, Fagan, Piedmont, Ponticas,& Wise, 1992).

Sexually Relevant Individual Differences

Measures of sexual attitudes, affects, behaviors, and more recently, cognitions, are available. Several individual difference measures assess evaluative (attitudinal) or affective reactions to sexual cues. One example is erotophobia–erotophilia, a tendency to respond to sexual cues along a negative to positive dimension of affect and evaluation (Byrne, 1983; Fisher, Byrne, White, & Kelley, 1988). According to this view, erotophobic individuals have negative affective and evaluative responses to sex and should therefore show avoidance, whereas erotophilic individuals, who have a positive affective and evaluative response to sex, should evidence approach responses. Factor analysis of the 21 items indicate that three dimensions are assessed: (a) openness to sexual experiences (primarily pornography); (b) arousal for sexual activities; and, (c) opinions (primarily negative) about homosexuality. Validity research indicates that, as expected, there is a positive correlation between erotophilia scores and measures of sexual behavior (intercourse) and sexual fantasy. Another example is the 43-item Sexual Attitudes Scale (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1987). This scale assesses four attitude topics: sexual permissiveness (similar to the sociosexuality measure), diverse sexual practices (e.g., masturbation) or topics (e.g., sex education), sex as a communication form with another person, and sex as an instrumental activity (e.g., “sex is for pleasure”).

Simpson and Gangestad (1991a, 1991b) have offered a conceptual framework for their focus on sociosexual orientation or the willingness to engage in uncommitted sexual relations. Individuals who possess an unrestricted sociosexual orientation require less closeness and commitment before having sex, whereas a restricted sociosexual orientation requires greater emotional involvement. Validity information indicates, for example, that unrestricted individuals tend to engage in sex at an earlier point in their sexual relationships; are more apt to have concurrent sexual affairs; and have relationships characterized by less commitment, love, and psychological dependency.

Surprisingly, there has been little attention to cognitive representations of sexuality (i.e., self-views of one’s sexuality). From this perspective, cognitions about the self (e.g., Markus & Wurf, 1987) would be important. We have proposed that sexual self-schema (self-concept) is a cognitive view about sexual aspects of oneself. One’s sexual self-view is derived from past experience, manifest in current experience, and it guides the processing of domain-relevant social information (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994). Well-articulated schemas may function as a quick referent of one’s sexual history, and also as a reference point for information—judgments, decisions, inferences, predictions, and behaviors—about the current and future sexual self. In addition to regulating intrapersonal processes, sexual self-schema mediates interpersonal processes, the most obvious being sexual relationships. Individuals with a clearly specified, positive sexual schema, for example, enter sexual relationships more willingly, have a more extensive behavioral repertoire, and evidence more positive emotions when in sexual relationships.

The 26-item Sexual Self-Schema Scale (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994) includes two positive aspects (an inclination to experience romantic–passionate emotions and a behavioral openness to sexual experiences or relationships) and a negative aspect (embarrassment or conservatism), that appears to be a deterrent to sexual expression. Women with a positive sexual schema, relative to those with a negative schema, view themselves as emotionally romantic or passionate, and as behaviorally open to romantic and sexual relationships and experiences. These women tend to be liberal in their sexual attitudes, and are generally free of such social inhibitions as self-consciousness or embarrassment. Women with positive schemas for example, tend to evaluate various sexual behaviors more positively, report higher levels of arousability across sexual experiences, and are more willing to engage in uncommitted sexual relations. This schematic representation is not merely a summary statement of sexual history, but it marks current and future possibilities, as women with positive schemas anticipate more sexual partners in the future than their counterparts with negative schemas. Despite this seemingly unrestricted view of sexuality, it is perhaps important to note that affects and behaviors indicative of romantic, loving, and intimate attachments are also central to women with positive sexual schemas, as they report extensive histories of romantic ties. This latter aspect distinguishes the sexual schema construct from Simpson and Gangestad’s (1991a, 1991b) concept of sociosexuality. In their view, individuals who are characterized as “unrestricted” in their sexual orientation report higher rates of sexual behavior as do the women with positive schemas; however unrestricted individuals also have less commitment and weaker affectional bonds. Thus, the positive schematic representation of a sexual woman includes both arousal–drive and romantic–attachment elements.

Conversely, women holding clear negative self-views of their sexuality tend to describe themselves as emotionally cold or unromantic and as behaviorally inhibited in their sexual and romantic relationships. These women tend to espouse conservative (and, at times, negative) attitudes and values about sexual matters and may describe themselves as self-conscious, embarrassed, or not confident in a variety of social and sexual contexts. Finally, there may be some potential vulnerability for women with negative self-views because their self-view can be significantly moderated or defined by others (e.g., the presence of a current sexual relationship), whereas this does not appear to be the case for the women with positive schemas.

In addition to representing positive and negative sexual schemas, the Sexual Self-Schema Scale can be scored to represent aschematic and coschematic profiles. Women who are aschematic appear to lack a coherent framework for guiding sexually relevant perceptions, cognitions, and behaviors. On the schema measure, they provide weak endorsements of both positive and negative schema adjectives. Hypotheses that such women have lower rates of sexual behavior and less positive sexual affects (e.g., sexual arousability and love for the sexual partner) have been confirmed. Alternatively, coschematic individuals have a schematic representation of their sexuality that is, in some sense, “conflicted.” Their pattern of responding on the schema measure is to provide strong endorsements of both positive and negative aspects. Our hypothesis that coschematic women might evidence discrepancies in their sexual affects has been confirmed; these women report higher levels of sexual anxiety, yet high levels of romantic attachment (love) for a partner. A final methodologic note about the scale is that the measure consists of 26 trait adjectives, and respondents completing the measure have no notion that an aspect of sexuality is being assessed. This aspect of the measure contrasts markedly with every assessment scale reviewed here, and it thus offers significant methodologic and clinical advantages. In summary, sexual schema is a previously untapped yet seemingly important aspect of women’s sexuality and self-concept.

Integration: An Empirical Examination of Sexual Behaviors, Sexual Responses, and Individual Differences

To illustrate the relationship between the domains identified here, we present data from female undergraduates (N = 172) who completed several measures of sexual behavior, response cycle, and personality as part of another study (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994). We used Goldberg’s (1992) measure of the Big Five and several of the assessment measures discussed earlier. Measures of current sexual behavior (e.g., frequency of intercourse) were actually completed on two occasions, separated by 2 months. For the present analyses, we averaged the current sexual behavior variables to obtain a more stable estimate.

The data are provided in Table 4. Considering the five personality dimensions, the most consistent pattern of relationships was found for the Extraversion scale. This pattern is inconsistent with the pattern that Costa et al. (1992) obtained using the NEO-PI with older women seeking treatment. One interpretation of these differences is that they indicate important generational and developmental differences in the study samples. In primarily young, unmarried women, extraversion may be related to the likelihood of engaging in sex, the variability in one’s behavior, and the affects associated with sex. Among older, predominately married women whose patterns of sexual behavior and responding may be more established, the dimension of neuroticism appears to be a more important personality variable.

Table 4.

Correlations Between Sexual Behavior and Responses and Measures of Individual Difference for College-Age Women (N = 172)

| Big-Five measure |

Sex-specific measure |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain and measure | Neuroticism | Extraversion | Intellectualism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Sociosexuality | Erotophobia | Schema |

| Sexual behavior: History | ||||||||

| Sexual Experience (DSFI) | .01 | .33 | .08 | −.03 | −.06 | .43 | −.41 | .37 |

| No. of Partners in Lifetime | .03 | .33 | .14 | −.03 | −.06 | .69 | −.44 | .41 |

| Sexual behavior: Current | ||||||||

| Sexual Experience (DSFI) | −.01 | .21 | −.05 | .16 | .06 | .18 | −.28 | .26 |

| Frequency of Intercourse | −.02 | .20 | −.10 | .12 | .11 | .20 | −.29 | .21 |

| Sexual responses | ||||||||

| Desire: Sexual thoughts | −.17 | .15 | −.06 | −.13 | −.09 | .42 | −.55 | .32 |

| Arousal: SAI | −.09 | .26 | .00 | .04 | .04 | .33 | −.56 | .37 |

| Arousal: Love | .00 | −.05 | .13 | .00 | −.07 | .03 | −.22 | .07 |

Note. All correlations >. 15 are significant, p= .05. DSFI = Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory; SAI = Sexual Arousability Index; Love = Hatfield Passionate Love Scale.

Comparison of the Big Five data with the sexual-specific measures reveals the usefulness of using such measures to predict sexual variables. As might be anticipated, the sociosexuality measure correlated strongly with measures of sexual behavior, and these data suggest potential overlap with measures assessing sexual history, particularly the number of previous partners. For the erotophobia measure, these data suggest that the construct functions as a generalized deterrent for sexual behavior as well as positive sexual responses. Finally, the sexual schema measure, as would be predicted, is correlated to virtually all aspects of sexuality.

Conclusion

We propose that the assessment of female sexuality be considered within the conceptual domains of sexual behaviors, sexual responses, and individual differences rather than by categories (e.g., functional vs. dysfunctional) or measures. Self-reports of sexual behavior have proven a necessary mainstay in both historical and contemporary assessments of female sexuality. However, many methodological problems of such assessments remain (see Catania et al., 1990), and today the area continues with a heterosexual emphasis. Still, sufficient research has emerged to suggest that the behavioral domain for women includes the behaviors of masturbation and other individual erotic activities, and arousing activities with a heterosexual partner ranging from kissing, erotic caressing, oral-genital contact, and anal stimulation, to intercourse.

A response cycle conceptualization, a four-stage model consisting of sexual desire, excitement, orgasm, and resolution, offers conceptual and diagnostic advantages. Within this framework, we considered physiological, cognitive, and affective assessment approaches. One area in need of scientific advancement is the concept of sexual desire (but see Beck, 1995). There are no measures of desire, per se, with the current alternatives including measures of sexual cognitions or proxy variables.

In contrast, theories have been proposed and several measures have been developed for the assessment of sexual excitement and related affects. With few exceptions, however, these efforts have consisted of the application of theories and methods for understanding men’s sexuality to the discovery of women’s arousal processes. Although useful data has resulted, the majority of it indicates that the empirical fit is poor. For example, data appear to support the influence of hormonal mechanisms on male sexual desire and behaviors, but data assessing hormone–behavior relationships for women are considerably less clear. Whereas there has been some confirmation of sexual arousal models of male response, empirical tests have disconfirmed these same conceptualizations when applied to women, such as parasympathetic predominance for initial arousal, anxiety inhibiting physiological arousal, and disruptive effects of performance demand.

In short, theoretical advances are needed in the understanding of sexual excitement processes for women. Toward this end, our discussion includes both positive and negative affects, as there is evidence for dysyncrony, but it also provides a manner for clarifying the boundaries for the construct. Within the domain of positive affects, emotions such as romantic attachment or love might be considered, as a variety of converging data indicate that for women these feelings are closely tied to sexual affects. For example, there are gender differences in content of sexual fantasies with women focusing on the personal–emotional feelings in contrast to men, who focus on the sexual content per se (Ellis & Symons, 1990); research on women’s self-esteem suggests that it comes, in part, from a sensitivity and interdependence with others (Joseph, Markus, & Tafarodi, 1992) rather than the more independent orientation common for men; and, finally, women’s own judgments about a “sexual woman” describe her as one who is passionate as well as romantic and loving (Andersen & Cyranowski, 1994).

With regard to negative affects that may inhibit or lower sexual arousal, we proposed several which fall within the domain of negative emotionality. This includes anxiety (i.e., tension and nervousness as assessed, e.g., with the SAI-E), sexual guilt or self-blame (e.g., the Janda & O’Grady measure), sexual self-criticism and self-consciousness (subscale of the SAS), and global sexual depression (i.e., sadness and hopelessness about one’s sexual life, as found in the Snell and Papini measure). It is also likely that aspects that tap behavioral avoidance are relevant to sexual excitement, including avoidance of sexual activities or stimuli per se (e.g., such as the sexual avoidance factor on the Katz Aversion Scale).

It is somewhat puzzling that, despite the considerable research tradition on the treatment of orgasmic dysfunction, there has been very little energy directed toward assessment. The modal strategy in research is to obtain frequency estimates for orgasm and then provide supplementary information on sexual affects (e.g., sexual arousal). In conceptualizing and assessing orgasm, we urge a view that considers the previous sexual responses of desire and excitement, as a variety of data suggest that subtypes of women with orgasm difficulties exist. Finally, there are no measures of sexual resolution per se. Instead, measures of sexual “satisfaction” exist. These latter measures do not appear to tap resolution, and it is unlikely that such measures would add incremental value to an assessment that included other, more central topics, such as sexual behavior or sexual excitement.