Abstract

Computational simulations of the electrodynamics of cardiac fibrillation yield a great deal of useful data and provide a framework for theoretical explanations of heart behavior. Extending the application of these mathematical models to defibrillation studies requires that a simulation should sustain fibrillation without defibrillation intervention. In accordance with the critical mass hypothesis, the simulated tissue should be of a large enough size. The choice of biperiodic boundary conditions sustains fibrillation for a longer duration than no-flux boundary conditions for a given area, and so is commonly invoked. Here, we show how this leads to a boundary condition artifact that may complicate the analysis of defibrillation efficacy; we implement an alternative coordinate scheme that utilizes spherical shell topology and mitigates singularities in the Laplacian found with the usual spherical curvilinear coordinate system.

Computational simulations of cardiac fibrillation are useful for defibrillation studies, particularly electrical defibrillation strategies. To sustain fibrillation long enough for a defibrillation study without using an unrealistically large tissue, in previous papers we invoked biperiodic boundary conditions (Hosfeld et al., 2007; Puwal and Roth, 2009). With such conditions our data fell into one of three categories: successful defibrillation, unsuccessful defibrillation with sustained fibrillation, and persistent electrical activity without fibrillation (which we call ventricular tachycardia (VT) for short). We find that VT is an artifact of the boundary conditions. Tissue of a specific size with biperiodic boundary conditions permits two phase singularities at opposite ends of the spiral arm to meet and annihilate leaving the spiral arm to continue propagation as a planar wave. This is not successful defibrillation, nor is it sustained fibrillation. Such a result cannot happen on the surface of a sphere; we, therefore, formally develop a coordinate system here [previously seen (Ronchi et al., 1996)] that solves the monodomain cable equation

for the three-variable model of spiral wave breakup into fibrillation proposed by Fenton and Karma (Fenton and Karma, 1998; Fenton et al., 2002). We compare a set of results from a feedback defibrillation strategy in which the tissue has biperiodic boundary conditions [previously published, see Hosfeld et al. (2007) and Puwal and Roth (2009)] to the results of attempted defibrillation on the surface of the sphere.

METHODS

A commonly invoked strategy for solving the cable equation (and parabolic differential equations in general) is the forward Euler numerical method. With a finite tissue size, at the edges of the tissue the Euler strategy requires boundary conditions to solve for the transmembrane potential (Eriksson et al., 1996; Press et al., 1992). Herein is the origin of the topology of the system of which we choose to make use.

A sheet of simulated tissue with no-flux boundary conditions forms a two-manifold (Lang, 1999). If no-flux boundary conditions are imposed on the edge of the tissue, then propagating action potential wave fronts can propagate into the edge and collide with a mirror image wave front, resulting in annihilation. This is a relatively realistic representation of a sheet of tissue that has been sliced out of the myocardium. However, such frequent annihilations tend to cause fibrillation to not be sustained.

An alternative set of boundary conditions is the biperiodic boundary. Biperiodic boundary conditions can be explained with the following example: given a square of tissue of size L×L placed on a Cartesian xy-plane from x=0 tox=L and from y=0 to y=L, biperiodic conditions set the potential along the edge of x=0 equal to the potential along the edge of x=L and the potential along the edge of y=0 equal to the potential along the edge of y=L. In this way an action potential propagates toward the x=L edge and then reenters at the x=0 edge (Eriksson et al., 1996; Press et al., 1992). This topology (still a two-manifold) (Lang, 1999) has the advantage, for a given tissue size, of sustaining fibrillation in simulations for a considerably longer duration than the no-flux boundary conditions (Strain and Greenside, 1998) because the rotary waves, which sustain fibrillation, do not propagate into a no-flux boundary and self terminate. This topology has the disadvantage of being a less realistic representation of cardiac tissue since it forms an infinite tessellation of a single square of tissue.

An alternative topology is a sphere (again, still a two-manifold) (Lang, 1999; Ronchi et al., 1996). Adopting spherical coordinates presents problems because of singularities in the Laplacian at the poles (θ=0 or π) and unequally spaced points with a higher density near the poles. The Laplacian in spherical coordinates is (Spiegel, 1959)

| (1) |

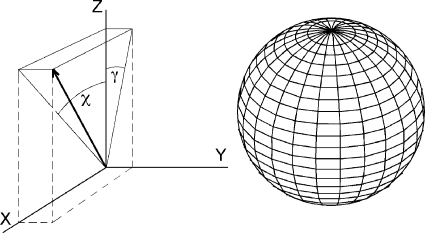

Rather than adopt the usual spherical coordinate angles θ and ϕ, we make use of the angles χ and γ, which specify the angle of the position vector (1) off the z-axis in the direction of the x-axis and (2) off the z-axis in the direction of the y-axis, respectively. This coordinate system is shown in Fig. 1. For a point on the unit sphere, these angles relate to the Cartesian coordinates as

| (2) |

This coordinate system is Riemannian but not Euclidean. There will, therefore, be off-diagonal terms in the metric tensor (Ronchi et al., 1996). Additionally, a singularity in the Laplacian arises, and we avoid it by dividing the surface of the sphere into six faces (Ronchi et al., 1996; Calhoun et al., 2008).

Figure 1. Alternative coordinate system (χ.

,γ) used to solve the Laplacian on the surface of a sphere. The point P lies on the sphere of radius R and is indicated by the position vector. The position vector of P projected into the xz-plane lies at an angle χ off the z-axis, and the position vector of P projected into the yz-plane lies at an angle γ off the z-axis.

In a Riemannian space with coordinates (x1,x2,…,xN), the differential arc length ds is given in Einstein notation as (Spiegel, 1959)

| (3) |

We may write this in vector-matrix form as

| (4) |

where G is the metric tensor and T denotes the transpose of the vector. The metric tensor has a nonzero determinant and so possesses an inverse (Lang, 1999; Spiegel, 1959). We specify the elements of the metric tensor as gij and the elements of the inverse of the metric tensor as gij. The Laplacian in a Riemann space is expressed as

| (5) |

where g denotes the absolute value of the determinant of G (Spiegel, 1959). In short, it is a general result of calculus on differential manifolds that for a differential arc length given in terms of the coordinates by Eq. 3 the Laplacian is given in terms of the coordinates by Eq. 5. In terms of χ and γ we find the Laplacian of the coordinate system of Eq. 2 on the unit sphere may be expressed as

| (6) |

We may then scale the Laplacian to a sphere of any radius R to be of the form (Ronchi et al., 1996)

| (7) |

Curvature is known to have an effect on the dynamics of the heart tissue, particularly when it is nonuniform (Rogers, 2002). In our model, the radius of curvature R is uniform over the entire surface.

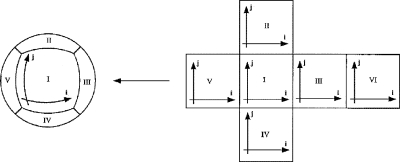

We may still numerically integrate Eqs. 6, 7 to solve the cable equation using the forward Euler numerical method. To do so, we divide the surface of the sphere into six faces (Fig. 2) and form a discrete mesh grid for each face where the nodes of the mesh are spaced uniformly in the angles χ and γ. If the mesh contains M×M nodes then the discrete steps of the Euler integration method are

| (8) |

Then χ=(Δχ/2)(2i−M) and γ=(Δγ/2)(2j−M), where i and j are integers corresponding to the coordinates in the discrete mesh where i and j vary from 1 to M. We allow χ and γ each to vary from −π/4 to +π/4 on each face of the sphere. On the edge between faces of the sphere we must impose a quasi-boundary condition that overlaps the faces. One can think of the faces as the faces of a cube that overlap around the edges; the cube is then inflated to produce the sphere.

Figure 2. Mapping of the six faces onto the surface of the sphere.

The “cross” figure on the right is folded into a cube, and the cube is inflated to produce the sphere on the left. This figure is a modified version of Fig. 3 in J. Comput. Phy.124, 93–114 by Ronchi et al. (1996).

RESULTS

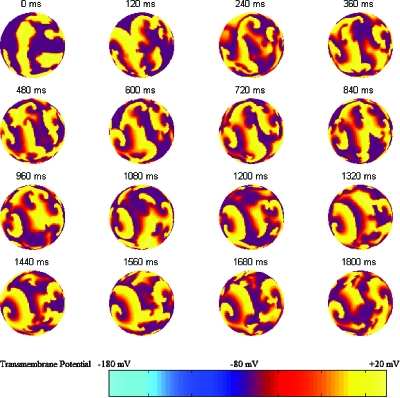

Solving the cable equation of the Fenton–Karma model of spiral wave dynamics using the forward Euler numerical technique and the spherical topology described here we are able to produce the dynamics of fibrillation on the surface of a sphere as shown in Fig. 3. The topology of this arrangement has shown itself to be excellent at accurately modeling the Fenton–Karma model of spiral wave breakup into fibrillation. We initialize fibrillation on each face of the sphere separately with the same procedure employed by Hosfeld et al. (2007).

Figure 3. Fibrillation on the spherical coordinate system.

Shown is one side of the sphere with a 120 ms frame rate. A randomly initialized distribution of rotary waves (shown at 0 ms) evolves into the distribution eventually shown in the 1800 ms frame. The rear view of the sphere looks qualitatively similar to this front view and is not shown. The color bar shows the relation between color and transmembrane potential.

An issue that arises in simulating fibrillation dynamics with a spherical topology is the tendency of the simulation to evolve to opposite poles. Rohlf et al. (2006) observed this behavior in their study of spiral wave dynamics on a spherical shell. Their conclusion that the rotary waves lengthened until poles of opposite chirality developed (exactly what is observed in Fig. 4) was a result of the tissue medium being weakly excitable.

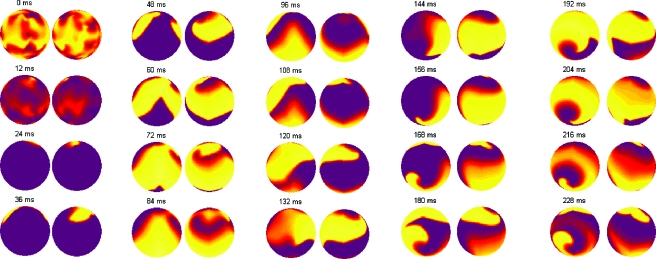

Figure 4. The development of poles of opposite chirality.

Both hemispheres of the sphere are shown for each time. The simulation is initialized in the 0 ms frame and quickly progresses to a relatively simple state of VF (few phase singularities) shown in the 48 ms frame. In frame 216 ms it is evident that poles of opposite chirality develop. While the singularities are not “pinned” to a particular location on the tissue, the poles where the phase singularities meander are a small area—analogous to precession but with no period of precession noted. We see this development of poles of opposite chirality in many of our simulations that are properly initialized to sustain fibrillation. The color map is the same as Fig. 3.

One motivation for the development of this topology is that, while the no-flux boundary conditions accurately reflect a “slice of tissue,” they do not sustain fibrillation for a long enough duration for defibrillation studies, and biperiodic boundary conditions sustain fibrillation for a longer duration but do not realistically reflect true heart topology. An additional motivation is the presence of an artifact of the biperiodic boundary conditions—persistent electrical activity (what is called, in short, throughout this paper VT because of its rapid rate). With biperiodic boundary conditions, spiral tips come in pairs connected by a spiral arm; for a specific size tissue with biperiodic boundary conditions, it is possible for the spiral tips to meet and mutually annihilate leaving only the spiral arm behind to continue propagating as a planar wave. This planar wave front chases its own back and cannot self terminate, leading to a persistent electrical activity. In previous papers we have referred to this as VT; with biperiodic conditions VT is achieved both with and without external stimulation (Hosfeld et al., 2007) (VT also should be possible for a monoperiodic boundary condition, corresponding to a cylinder). With spherical topology, these spiral tip pairs are unable to meet each other and leave their spiral arm behind for persistent electrical activity, and we no longer have the artifact of VT in our data.

In addition to examining the dynamics of fibrillation, we perform simulations of low-energy defibrillation. Consider the multielectrode, on-demand defibrillator presented in Hosfeld et al. (2007) and Puwal and Roth (2009), where activation is detected at an electrode site and a pacing impulse is delivered T ms later unless another activation is detected before T elapses. As in Hosfeld et al. (2007), all stimuli are applied by a stimulus current added to the membrane current. The simulated tissue of our previous study used biperiodic boundary conditions and had an area of 27.56 cm2. A spherical shell of the same surface area has a radius of R=1.481 cm (A=4πR2). Our simulations with biperiodic boundary conditions found (with the electrodes in a square arrangement) that the pacing electrodes should be maximally spaced to achieve optimal defibrillation. For a uniform electrode spacing on the surface of a sphere (where the pacing electrodes are maximally spaced) we place the electrodes at the vertices of a tetrahedral platonic sphere (also known as the tetrahedral sphere) that function as shown in Fig. 5. A tetrahedral sphere projects the faces of an inscribed tetrahedron onto the surface of a sphere where the four faces of the tetrahedron project as spherical triangles (Cromwell, 1997). The four vertices (points where the corners of the spherical triangles meet) will serve as the location for the pacing electrodes in our simulations, and the lengths of the edges of the spherical triangles will be the electrode spacing. This is precisely the spatial arrangement of the atoms in a methane molecule (CH4) (Kotz and Treichel, 1999) with the pacing electrodes located at the “hydrogen” atoms and the sphere centered on the “carbon atom,” and a bond angle of 73/120π rad, so we space the electrodes on the sphere 73/120π apart. We have divided up the surface of the sphere into six faces where on each face χ and γ vary from −π/4 to +π/4, which somewhat complicates the expression for the coordinates of the pacing electrodes. We place electrode 1 on sphere face 1 at coordinate (χ,γ)=(0,0) and find as a result that electrode 2 is placed on sphere face 2 at coordinate (χ,γ)=(−73/120π,73/120π), electrode 3 is placed on sphere face 3 at coordinate (χ,γ)=(73/120π,0), and electrode 4 is placed on sphere face 4 at coordinate (χ,γ)=(−73/120π,−73/120π). We find with the help of Eq. 8 that the electrodes are located at

or in pseudocode

| (9) |

where i and j denote the coordinate of the discrete mesh of a face and k denotes the face of the sphere (recalling that we divided the sphere into six faces, forming an “inflated sphere”).

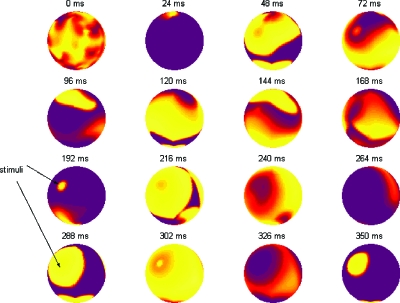

Figure 5. Simulation showing how external electrical stimulation is accurately reproduced in this coordinate system.

One face of the sphere is observed for 350 ms. Observe the stimuli pointed out at 192 and 288 ms. Regional capture is achieved, leading to global entrainment (see 350 ms). The protocol calls for pacing for 3 s, therefore a diastolic state is eventually achieved when the pacing ceases. The color map is the same as Fig. 3.

We define our on-demand defibrillation pacing strategy as follows: with multiple, independently functioning detection/pacing electrodes we seek to detect electrical activation of the tissue at the site of the electrode. If no activation is detected in an interval of duration T ms, we deliver a pacing stimulus. If an activation is detected, we reset our clock and wait another T ms; thus, we may actively shorten the interactivation interval but not actively lengthen it. We compare the results of defibrillation pacing with an on-demand pacing period of 81 ms using four equally spaced electrodes on the surface of this sphere and find that, for the sphere, 84.5% achieve defibrillation, and we find no VT (7% spontaneous termination). This compares favorably to 88% defibrillation and a 1% VT rate for the sheet of tissue with biperiodic boundary conditions (4% spontaneous termination) that we noted in previous publications (Hosfeld et al., 2007; Puwal and Roth, 2009). In this instance VT was negligible. However, in other cases VT was as high as 10–15% (Hosfeld et al., 2007), and the spherical topology provides a significant improvement of the simulation. Figure 5 shows an example of defibrillation pacing leading to capture and then entrainment of the entire tissue. With this topology, we easily noted a 2:1 response to the stimulus [we also saw a 2:1 response in previous publications (Hosfeld et al., 2007; Puwal and Roth, 2009)]. We note with the biperiodic boundary conditions that if the pacing period is doubled defibrillation is not as effective, so the 2:1 response to stimuli must play a role in the capture of the tissue and ultimate termination of the fibrillation. This coordinate system produces an excellent replication of successful defibrillation on a new topology.

We find that simulating spiral wave dynamics on this tissue behaves as expected: fibrillation and defibrillation are reproduced as in our previous studies (as exemplified in Figs. 35), and the artifact of persistent electrical activity (shorthand VT) is avoided. By choosing this coordinate system we avoid singularities in the Laplacian found with the usual spherical coordinate system. While it is possible to perform similar simulations using a grid based on spherical coordinates (Chavez et al., 2001), our numerical scheme allows grid points to be more evenly distributed on the sphere surface. Finite element methods could also be used in these simulations (Rogers, 2002), but for simple spherical geometries the algorithm may be easier to implement using finite differences, as we use, rather than finite elements. Furthermore, this method could simulate a ventricle by removing one face of the sphere and imposing no-flux boundary conditions on the face edge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation (Grant No. PHY-0456655) and by funds from Oakland University.

References

- Calhoun, D A, Helzel, C, and LeVeque, R J (2008). “Logically rectangular grids and finite volume methods for PDEs in circular and spherical domains.” SIAM Rev. 10.1137/060664094 50, 723–752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, F, Kapral, R, Rousseau, G, and Glass, L (2001). “Scroll waves in spherical shell geometries.” Chaos 10.1063/1.1406537 11, 757–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell, P R (1997). Polyhedra: “One of the Most Charming Chapters of Geometry,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K, Estep, D, Hansbro, P, and Johnson, C (1996). Computational Differential Equations, Studentlitteratur, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, F H, Cherry, E M, Hastings, H M, and Evans, S J (2002). “Multiple mechanisms of spiral wave breakup in a model of cardiac electrical activity.” Chaos 10.1063/1.1504242 12, 852–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, F, and Karma, A (1998). “Vortex dynamics in three-dimensional continuous myocardium with fiber rotation: filament instability and fibrillation.” Chaos 10.1063/1.166311 8, 20–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosfeld, V D, Puwal, S, Jankowski, K, and Roth, B J (2007). “A model for multi-site pacing of ventricular fibrillation using nonlinear dynamics feedback.” J. Biol. Phys. 10.1007/s10867-007-9049-9 33, 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz, J C, and Treichel, P, Jr. (1999). Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity, 4th Ed., Wiley, Fort Worth. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S (1999). Fundamentals of Differential Geometry, Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Press, W H, Teukolsky, S A, Vetterling, W T, and Flannery, B P (1992). Numerical Recipes in Fortran 77: the Art of Scientific Computing, 2nd Ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Puwal, S, and Roth, B J (2009). “Optimization of feedback pacing for defibrillation.” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J M (2002). “Wave front fragmentation due to ventricular geometry in a model of the rabbit heart.” Chaos 10.1063/1.1483956 12, 779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf, K, Glass, L, and Kapral, R (2006). “Spiral wave dynamics in excitable media with spherical geometries.” Chaos 10.1063/1.2346237 16, 037115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronchi, C, Iacono, R, and Paolucci, P S (1996). “The ‘cubed sphere’: a new method for the solution of partial differential equations in spherical geometry.” J. Comput. Phys. 10.1006/jcph.1996.0047 124, 93–114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, M R (1959). Schaum’s Outline of Theory and Problems of Vector Analysis and an Introduction to Tensor Analysis, McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Strain, M C, and Greenside, H S (1998). “Size-dependent transition to high-dimensional chaotic dynamics in a two-dimensional excitable medium.” Phys. Rev. Lett. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.2306 80, 2306–2309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]