Abstract

Objectives

Suppressive HSV therapy can decrease plasma, cervical, and rectal HIV-1 levels in HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected persons. We evaluated the effect of HSV-2 suppression on seminal HIV-1 levels.

Design

Twenty antiretroviral therapy (ART)–naive HIV-1/HSV-2–MSM in Lima, Peru, with CD4 cell counts >200 cells/µL randomly received valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 8 weeks, then the alternative regimen for 8 weeks after a 2 week washout. Peripheral blood and semen specimens were collected weekly. Anogenital swab specimens for HSV DNA were self-collected daily and during clinic visits.

Methods

HIV-1 RNA was quantified in seminal and blood plasma by TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) or Roche Amplicor Monitor assays. HSV and seminal cytomegalovirus (CMV) were quantified by rt-PCR. Linear mixed models examined differences within subjects by treatment arm.

Results

Median CD4 count of participants was 424 cells/µL. HIV-1 was detected in 71% of 231 semen specimens. HSV was detected from 29% and 4.4% of swabs on placebo and valacyclovir, respectively (P<0.001). Valacyclovir significantly reduced the proportion of days with detectable seminal HIV-1 (63% during valacyclovir vs. 78% during placebo, p=0.04). The quantity of HIV-1 in semen was 0.25 log10 copies/mL lower (95%CI −0.40 to −0.10, p=0.001) during the valacyclovir arm compared with placebo, a 44% reduction. CD4 count (p=0.32) and seminal cellular CMV quantity (p=0.68) did not predict seminal plasma HIV-1 level.

Conclusions

Suppressive valacyclovir reduced seminal HIV-1 levels in HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infected MSM not receiving ART. The significance of this finding will be evaluated in a trial with HIV-1 transmission as the outcome.

Keywords: seminal plasma, HIV-1, viral load, HSV-2, valacyclovir, herpes, blood plasma

INTRODUCTION

The earliest reports of interactions between HSV-2 and HIV-1 infections were from the 1980s, including among men who have sex with men (MSM)1. Recently, several studies have shown that daily suppressive antiviral therapy for HSV reduces plasma, cervical and rectal HIV-1 levels in HIV-1 and HSV-2 infected adults2–5; a clinical trial to assess the efficacy of this approach for reduction of sexual transmission of HIV-1 is ongoing6. Plasma HIV-1 level has been demonstrated to be a significant biologic marker of HIV-1 transmission risk from an HIV-infected partner7, 8. Semen is the main biologic fluid for exposure from HIV-infected men to their female and male partners during insertive sex9. However, a direct relationship between seminal HIV-1 level and transmission has not been shown in part due to difficulties in conducting sufficiently large, prospective studies of HIV-1 discordant couples with collection of blood and genital samples7.

HIV-1 transmission is related to many factors10, and reductions in plasma and seminal HIV-1 levels may lead to reduced HIV-1 infectiousness. Although prior studies have demonstrated that HSV suppression reduces plasma, cervical and rectal HIV-1 levels, no studies have assessed the effect of HSV suppression on seminal HIV-1 levels. We evaluated seminal HIV-1 levels in a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial among HIV-1/HSV-2 coinfected MSM that demonstrated a mean 0.33 log10 reduction in plasma HIV-1 during twice daily suppressive valacyclovir3.

METHODS

Study Characteristics

Study design

As previously described3, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of valacyclovir for HSV and HIV-1 suppression was conducted in Lima, Peru. Briefly, participants were MSM who were >18 years old, were seropositive for HIV-1 and HSV-2, had no history of antiretroviral use, and had a CD4 cell count >200 cells/µL per Peruvian guidelines for ART initiation at the time of study implementation3. Exclusion criteria included current or planned therapy with antiretrovirals or antivirals for HSV (acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir), a history of adverse reactions to these antivirals, a history of seizures, a serum creatinine level >2.0 mg/dL, or hematocrit <30%.

The human experimentation guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services and the individual institutions were followed in the conduct of the clinical research. The institutional review boards of the University of Washington and the Asociación Civil Impacta Salud y Educación approved the protocol.

Study medication

Valacyclovir (500 mg orally twice daily) and matching placebo were supplied by GlaxoSmithKline. As previously described3, subjects were randomly assigned 1:1 (valacyclovir to placebo) in blocks of 10. After 8 weeks of the initial treatment, each participant crossed over to the alternative treatment for 8 weeks, separated by a 2-week washout period with daily placebo. Open-label valacyclovir (1 g orally twice daily for 3 days) was dispensed for symptomatic herpes recurrences. Four men were treated with open-label valacyclovir for genital herpes recurrences during the study, of which 3 occurred during placebo administration.

Study procedures

At enrollment, participants underwent a physical exam, and had blood, semen and HSV swabs collected. Participants came to clinic 3 times a week. In addition to anoscopy samples for HIV-1 and HSV, and blood draws reported previously, weekly semen samples were collected into sterile containers by study participants either just prior to the clinic visit or in a private room at the clinic. Seminal plasma was used for HIV-1 analysis and the cell component was used for CMV analysis. Participants also collected daily swabs of genital and perianal skin at home for HSV DNA PCR, as described3.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory Procedures

Blood specimens

Peripheral blood was collected into tubes containing EDTA (Becton Dickinson) and separated within 6 h into plasma and mononuclear cells by ficoll-hypaque gradient centrifugation. Lymphocyte subsets were determined by flow cytometry methods in Lima. Plasma aliquots were frozen at −70° C and transported to the University of Washington Retrovirology Laboratory. Blood plasma preparation methods have been described previously3

Semen specimens

Within 6 hours of collection, vials containing whole semen specimens were frozen at −80° C. Semen samples were transported to the University of Washington on dry ice and stored at −80 °C until tested. Vials were thawed and microcentrifuged at 16,000g for 15 minutes to separate seminal plasma and cell components. Seminal plasma aliquots (250 µL) were diluted 1:5 with RPMI media11 and centrifuged for 1 h at 23,000g. The pellets were resuspended in bioMerieux lysis buffer and extracted using the MiniMAG® Extraction system, which uses magnetic silica beads based on the Boom® Technology (bioMerieux, Durham, NC).

HIV-1 RNA quantitation assays

HIV-1 RNA was quantified using an independently validated TaqMan real-time RNA PCR (rt-PCR) amplification assay or the Amplicor HIV Monitor assay (Roche Molecular Systems)3, 12. For the TaqMan assay, the lower limit of detection (LLOD) for HIV-1 quantitation in blood plasma was 120 (2.1 log10) HIV-1 RNA copies/mL; for the Amplicor HIV Monitor assay, the LLOD in plasma was 400 (2.6 log10) HIV-1 RNA copies/mL. In semen, LLOD were 300 and 800 copies/mL for the Taqman real-time PCR or Roche Amplicor® Monitor, respectively.

HSV and CMV DNA Assays

DNA was extracted from each specimen. A fluorescent probe– based rt-PCR (TaqMan; Applied Biosystems) assay was used to quantitate HSV3, 13 and CMV levels14. LLOD for HSV detection was 2.69 log10 copies/mL and for CMV detection was 10 copies/mL.

Statistical Methods

HSV shedding rate was computed by dividing the days with detectable HSV in swabs collected at home or in the clinic by the total days of swab collection. All analyses were done on an intent-to-treat basis, excluding the first day of study drug administration from each arm. Laboratory testing was performed without knowledge of treatment assignment. For undetectable HIV-1 values, the midpoint between zero and the LLOD was used15; quantitative HIV-1 and CMV values were log-transformed. HSV shedding was examined as a binary variable (detected vs. not detected), as HSV DNA was detected in only a small proportion of samples. Since CMV detection was more common, quantity detected was retained and a sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the influence of the values assigned to amounts below the limit of detection. There was no difference in the outcomes between analyses done with undetectable CMV set to zero vs. when undetectable quantities were set to a random value between 0 and the lower limit of detection.

Linear mixed models were used to examine quantitative differences within subjects by treatment arm, using multivariate models to evaluate the effects of co-factors. Because HIV-1 quantity was modeled on the log10 scale, coefficients from models are exponentiated and compared with 1 to compute percent change in HIV-1 quantity. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS for Windows (version 9.1).

RESULTS

The study population has been described previously3, with one subject excluded due to persistent semen assay inhibition, so the analysis included 19 men. The median age was 39 years [range 22–45] and median CD4 count was 424 cells/µL [range 232–869]. Using adherence data from pill counts conducted every two weeks, participants took a median of 97% [range: 65.8–100%] of pills.

HSV and HIV-1 detection and levels

Overall, HIV-1 was detected at least once in semen samples from all 19 participants and in 71% of 231 semen specimens (Table 1). HSV was detected in 29% and 4.4% of rectal and anogenital swab specimens from participants on placebo and valacyclovir, respectively (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Rates of HSV and HIV-1 detection and mean HIV-1 quantities for plasma and semen samples, by treatment arm

| Both arms | Placebo | Valacyclovir | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV detection rate (anogenital or rectal sample) | 338/2043 (17%) |

293/1015 (29%) |

45/1028 (4.4%) |

≤0.001 |

| Seminal HIV-1 detection rate | 163/231 (71%) |

89/114 (78%) |

74/117 (63%) |

0.04 |

| Seminal HIV-1 quantity (mean, log10 HIV RNA copies/ml) | 3.33 | 3.48 | 3.19 | 0.02 |

| Plasma HIV-1 detection rate | 269/273 (99%) |

135/137 (99%) |

134/136 (99%) |

|

| Plasma HIV-1 quantity (mean, log10 HIV RNA copies/ml) | 4.34 | 4.52 | 4.17 | ≤0.001 |

p-value represents comparison between valacyclovir and placebo

Undetectable HIV-1 levels were set halfway between zero and the lower limit of detection (LLOD).

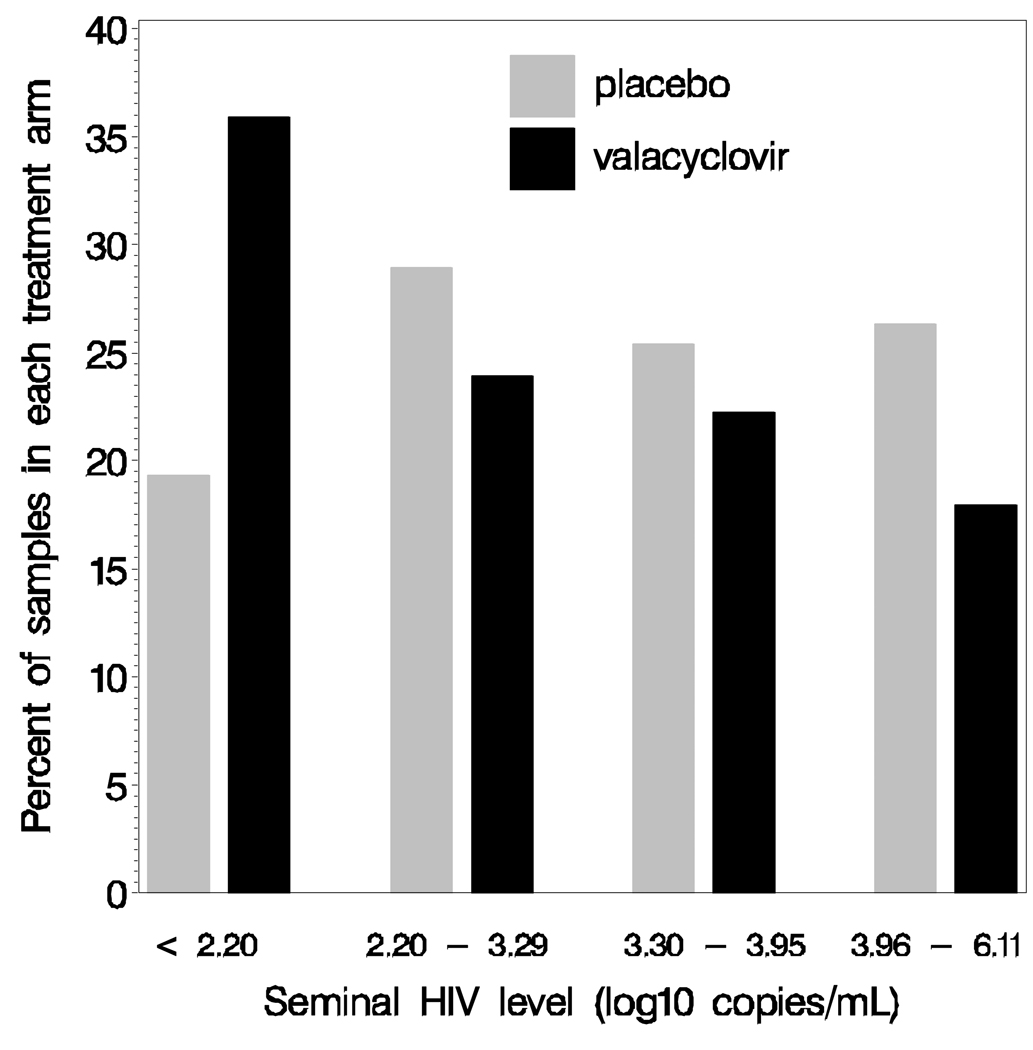

Daily valacyclovir suppression reduced the proportion of seminal samples with detectable HIV-1 (63% of samples during valacyclovir vs. 78% during placebo, p=0.04, Table 1) and the quantity of HIV-1 in seminal plasma (Figure 1). Mean seminal HIV-1 level (log10 copies/mL) was 3.19 during valacyclovir and 3.48 during placebo treatment.

Figure 1.

Graph showing the percent of semen samples in each treatment arm stratified by seminal HIV RNA level in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial in 19 men. Valacyclovir treatment is associated with lower detection rate and lower seminal HIV-1 levels. Each bar represents the percent of samples in each treatment arm stratified by seminal HIV-1 level (placebo, N=113 samples.; and valacyclovir, N=117samples).

Undetectable HIV-1 levels were set halfway between zero and the lower limit of detection (LLOD), hence some values are below the LLOD for our assays.

In a linear mixed model, the quantity of HIV-1 in semen was 0.25 log10 lower (95%CI −0.40 to −0.10, p=0.001) during the valacyclovir arm compared with placebo, a 44% reduction. The mean seminal HIV-1 level was reduced in 15 participants and increased in 4 participants during valacyclovir therapy.

Effect of covariates on seminal HIV-1 levels

There was a trend towards an association between plasma HIV-1 RNA and seminal HIV-1 levels (p=0.07), but the addition of plasma HIV-1 RNA levels to the model minimally changed the effect of valacyclovir on seminal HIV-1 levels (0.29 log10 decrease in seminal HIV-1 with valacyclovir; 95%CI −0.48 to −0.11, p=0.002). CD4 cell count did not predict seminal HIV-1 levels (p=0.32). CMV was detected in 111 of 208 tested semen samples and in at least one sample from 11of 18 men, and was not quantitatively associated with seminal HIV-1 levels (p=0.68) or administration of valacyclovir (p=0.68; mean CMV level=2.3 log10 on placebo and 2.1 log10 on valacyclovir).

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to demonstrate that suppressive valacyclovir reduced seminal HIV-1 levels in HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infected MSM with intermediate CD4 counts not receiving ART. A 0.25 log10 reduction in HIV-1 levels in semen was observed during multiple time points in each study arm. HSV-2 suppression studies have shown 0.3–0.5 log10 reductions in plasma HIV-1 levels, and approximately 0.3 log10 reductions in HIV-1 levels in cervical and rectal secretions2–5. Seminal HIV-1 levels may be an important surrogate for HIV-1 infectiousness and co-factors, such as HSV-2 reactivation, likely influence HIV-1 infectiousness10.

Inclusion of plasma HIV-1 in the linear effects model did not meaningfully alter valacyclovir’s effect on HIV-1 shedding. This finding suggests that the association may not be strongly linked to plasma HIV-1 level and that the male genital tract could be a distinct virologic compartment from the blood16. An indirect mechanism of HSV-2 suppression on reduction of seminal HIV-1 levels appears most likely as HSV is rarely detected in semen17. This mechanism requires further clarification. The dose of valacyclovir used in this study for HSV-2 suppression is significantly lower than the IC50 for CMV, so we did not anticipate that valacyclovir would suppress CMV. However, given a previous report which indicated that seminal HIV-1 levels were associated with concomitant CMV shedding18, we assessed CMV reactivation as a covariate for seminal HIV-1 and did not find an association.

Our study was limited by the fact that we sampled only cell-free seminal plasma for HIV-1 and cell associated HIV-1 may also be important in HIV-1 transmission. Additionally, we examined only cell-associated CMV as a covariate due to small volumes of seminal samples.

Recently, Butler et al. evaluated factors associated with HIV-1 transmission events in MSM, including seminal HIV-1 level7. In that study of 47 men, plasma HIV-1 level and HSV-2 seropositivity of the source partner were the strongest predictors of HIV-1 transmission with seminal HIV-1 level being less significant. We have shown here that HSV suppression with the anti-herpes medication, valacyclovir, reduces seminal and plasma HIV-1 levels, which may reduce HIV-1 infectiousness. Our findings support the ongoing clinical trial, Partners in Prevention, which is evaluating the effect of HSV-2 suppression on HIV-1 transmission in HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infected men and women.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their grateful appreciation to the study participants. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Shyla Sánchez and Julio Chamochumbi for study coordination and scheduling in Lima, Carmen Sánchez, Sofia Sánchez and Dr. Jorge Vergara for clinical support and procedures for study participants, Dr. Rosario Zuñiga and the laboratory team at laboratory Impacta, Drs. Jeffrey Ferris and Esmellin Pérez for pharmacy support, Jerry Galea for technical support, Dr. Tuofu Zhu, Joan Dragavon and the UWRL staff, Stacy Selke, Dr. Meei-Li Huang, Dr. Rhoda Ashley-Morrow and the UW Virology Research Laboratories for support.

Financial support: This study was supported by a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline and NIH CFAR Clinical Research and Laboratory Core Grants AI-27757 & AI-38858, R37 AI-42528 and NIAID Grant AI-30731.

Footnotes

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Human experimentation guidelines of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the individual institutions were followed in the conduct of the clinical research.

Presentation of this work: This work was presented in part at the 17th Annual Meeting of 17th ISSTDR Meeting - 10th IUSTI World Congress July 30, 2007, Seattle, WA.

Potential Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Dr. Celum has received research grant support from GlaxoSmithKline and has served on an advisory board for GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Jorge Sanchez has received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Wald has received grant support from National Institutes of Health, GlaxoSmithKline, Antigenics, and Astellas. She has been a consultant for Novartis, Powdermed, and Medigene and a speaker for Merck Vaccines. The University of Washington Virology Division Laboratories have received grant funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis to perform HSV serologic assays and PCR assays for studies funded by these companies. Dr. Corey directs these laboratories. He receives no salary support from these grants.

Trial Registration: This trial has been registered at clinical trials.gov: NCT00378976.

References

- 1.Stamm WE, Handsfield HH, Rompalo AM, Ashley RL, Roberts PL, Corey L. The association between genital ulcer disease and acquisition of HIV infection in homosexual men. JAMA. 1988;260(10):1429–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagot N, Ouedraogo A, Foulongne V, et al. Reduction of HIV-1 RNA levels with therapy to suppress herpes simplex virus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):790–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuckerman RA, Lucchetti A, Whittington WL, et al. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) suppression with valacyclovir reduces rectal and blood plasma HIV-1 levels in HIV-1/HSV-2-seropositive men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1500–1508. doi: 10.1086/522523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delany S, Maynaud P, Calyton T, et al. Impact of HSV-s suppressive therapy on genital and plasma HIV-1 RNA in HIV-1 and HSV-2 seropositive women not taking ART: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Johannesburg, South Africa. 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2007 February 25–28; Los Angeles, CA, USA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baeten JM, Strick LB, Lucchetti A, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)-Suppressive Therapy Decreases Plasma and Genital HIV-1 Levels in HSV-2/HIV-1 Coinfected Women: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. J Infect Dis. 2008 Oct 17; doi: 10.1086/593214. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lingappa JR, Lambdin B, Bukusi EA, et al. Regional differences in prevalence of HIV-1 discordance in Africa and enrollment of HIV-1 discordant couples into an HIV-1 prevention trial. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(1):e1411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler DM, Smith DM, Cachay ER, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 serostatus and viral loads of HIV-1 in blood and semen as risk factors for HIV transmission among men who have sex with men. Aids. 2008;22(13):1667–1671. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830bfed8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakraborty H, Sen PK, Helms RW, et al. Viral burden in genital secretions determines male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV-1: a probabilistic empiric model. AIDS. 2001;15(5):621–627. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(9):553–563. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70156-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coombs RW, Collier AC, Allain JP, et al. Plasma viremia in human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(24):1626–1631. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198912143212402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CC, Seidel KD, Coombs RW, Frenkel LM. Detection and quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p24 antigen in dried whole blood and plasma on filter paper stored under various conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):3901–3905. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3901-3905.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wald A, Huang ML, Carrell D, Selke S, Corey L. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of herpes simplex virus (HSV) DNA on mucosal surfaces: comparison with HSV isolation in cell culture. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(9):1345–1351. doi: 10.1086/379043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boeckh M, Huang M, Ferrenberg J, et al. Optimization of quantitative detection of cytomegalovirus DNA in plasma by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(3):1142–1148. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1142-1148.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JP. Mixed effects models with censored data with application to HIV RNA levels. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):625–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coombs RW, Lockhart D, Ross SO, et al. Lower genitourinary tract sources of seminal HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(4):430–438. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209895.82255.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wald A, Matson P, Ryncarz A, Corey L. Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA in semen of men with genital HSV-2 infection. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26(1):1–3. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth PM, Danesh A, Sheung A. Disproportionately high semen shedding of HIV is associated with compartmentalized cytomegalovirus reactivation. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(1):45–48. doi: 10.1086/498576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]