Abstract

A vast amount of circumstantial evidence implicates oxygen-derived free radicals (especially, superoxide and hydroxyl radical) and high-energy oxidants [such as peroxynitrite (OONO−)] as mediators of shock and ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Reactive oxygen species can initiate a wide range of toxic oxidative reactions. These include initiation of lipid peroxidation, direct inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes, inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3phosphate dehydrogenase, inhibition of membrane sodium/potassium adenosine 5′-triphosphate-ase activity, inactivation of membrane sodium channels and other oxidative modifications of proteins. All these toxicities are likely to play a role in the pathophysiology of shock and ischaemia and reperfusion. Moreover, various studies have clearly shown that treatment with either OONO− decomposition catalysts, which selectively inhibit OONO−, or with superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics, which selectively mimic the catalytic activity of the human SOD enzymes, have been shown to prevent in vivo the delayed vascular decompensation and the cellular energetic failure associated with shock and ischaemia/reperfusion injury.

British Journal of Pharmacology (2009) 157, 494–508; doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00255.x

This article is part of a themed section on Endothelium in Pharmacology. For a list of all articles in this section see the end of this paper, or visit: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/121548564/issueyear?year=2009

Keywords: shock, ischaemia/reperfusion injury, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite, superoxide dismutase

Introduction

Reduction of effective blood flow represents the primary disturbance accounting for circulatory shock.

The mechanisms involved are multifactorial. Diverse molecular mechanisms of inflammation and cellular damage have been implicated in the pathogenesis of shock (Bulkley, 1989; Lefer and Lefer, 1993; Merx and Weber, 2007; Carlet et al., 2008), including those related to overt generation of cytokines, eicosanoids and reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as nitric oxide (NO), superoxide anions and peroxynitrite (OONO−) (Taylor et al., 1995). To date, inhibitors of the synthesis/release or actions of cytokines, eicosanoids and NO have not been shown to have beneficial effects on shock or mortality in randomized controlled clinical trials (De Warra et al., 1997; Masini et al., 2000). These results are not surprising in light of the fact that these mediators possess both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties.

Free radicals are molecules or portions thereof that possess one or more unpaired electrons in their outer orbital, a state which greatly increases their reactivity (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1985; Kehrer, 1993). The best known reactive species generated from oxygen include superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical (·OH) and OONO−.

The term oxidative stress is often used to imply a condition in which cells are exposed to excessive levels of either molecular oxygen or chemical derivatives of oxygen called ROS. In the process of normal cellular metabolism, oxygen undergoes a series of univalent reductions, leading sequentially to the production of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and H2O. Other oxidants that have relevance to vascular biology are hypochlorous acid (HOC1), the ·OH, OONO−, reactive aldehydes, lipid peroxides, lipid radicals and nitrogen oxides (Beckman and Crow, 1993; Eiserich et al., 1996). Several of these, such as superoxide, the ·OH and NO are radicals with an unpaired electron in their outer orbital. Other oxidants, such as H2O2 and OONO−, are not radicals but are biologically active. In the vascular wall, increases in oxidant stress alter several important physiological functions. Regulation of blood flow, inhibition of platelet aggregation, inhibition of leukocyte adhesion and control of cellular growth are influenced by oxidant stress (McCord, 1985). These phenomenons ultimately modulate vessel diameter, remodelling and lesson formation (Ma et al., 1995; Wang and Zweier, 1996). ROS, which are thought to have relevance to vascular biology, include superoxide, H2O2, OONO−, lipid hydroperoxides and hydroperoxy-radicals and probably hydroxyl-like radicals. Both H2O2 and OONO− are generated as reaction products of the superoxide anion. While H2O2 mainly emerges from intra and extracellular dismutation of superoxide by the abundantly present superoxide dismutases (SOD), OONO− is formed by the rapid reaction of superoxide with NO (Beckman et al., 1990; Crow and Beckman, 1995; Squadrito and Pryor, 1995). Thus, the generation of superoxide anions most likely plays a central role as the source for many other ROS. The concentration of ROS in the vasculature is normally balanced by activities of SOD and catalase, thus converting potentially damaging free radicals into innocuous molecules. After insult such as ischaemia and reperfusion, this balance is disrupted, leading to an increase in ROS exposure in the vasculature. Increases in ROS, such as superoxide (O2) and ·OH, lead to changes in cell signalling, both independently and by interrupting normal nitric oxide (NO·)-mediated vessel relaxation.

One of the major injuries to arteries is an impairment of Ca2+-regulating mechanisms. Because ROS are increased during ischaemia and have been linked to multiple effects on Ca2+ signalling in both the endothelium and smooth muscle, it is likely that the signals affected by ROS are important mediators of arterial injury (Volk et al., 1999). The evidence supporting a role for ROS in arterial dysfunction is complicated by differences in the type of radical species examined and variations in experimental protocols.

Thus, although individual mediators of each of these structural classes have been causally implicated in shock, each plays important homeostatic functions in the complex host response. Accordingly, their utility as appropriate therapeutic targets for immunopharmacologic suppression has been questioned.

The most important feature of the shock state that ultimately determines survival is the reversibility of inadequate organ perfusion secondary to loss of vasomotor tone, which in turn leads to reduced venous return, cardiac output and severe arterial hypotension (Groeneveld et al., 1986). In order to overcome such haemodynamic derangements, standard treatment consists of prompt initiation of antibiotics even as haemodynamic abnormalities are addressed by i.v. fluid resuscitation and exogenously administered catecholamines (dopamine and especially norepinephrine) (Levy et al., 1997) to preserve or augment blood flow to vital organs (e.g. brain, heart, liver and kidney). Despite such aggressive therapy, successful outcomes are limited because of the development of vascular hyporeactivity (i.e. the loss of normal vasoconstrictor responses) to exogenously administered dopamine and norepinephrine (Martin et al., 2000). This hyporeactivity hampers the ability of the clinician to sustain blood pressure. Such inability to successfully restore and maintain an appropriate blood pressure leads to severe hypoperfusion of critical organs and, eventually, death. Published experimental evidence suggests that hyporeactivity to exogenous norepinephrine results from its deactivation by superoxide (Macarthur et al., 2000).

Novel pharmacologic approaches are being directed at three distinct levels of the inflammatory cascade: the inciting insult (i.e. endotoxin), the mediators [i.e., tumour necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 (IL-1), oxygen free radicals] and the effector cells (i.e., neutrophils) (Wu, 2006).

The intent of this review is to discuss the mediators in circulatory shock as well as the experimental and clinical evidence implicating their role in development and pathogenesis of the injury. Current status of novel adjunctive therapies for circulatory shock is reviewed.

Circulatory shock

Circulatory shock is a syndrome of haemodynamic and metabolic disturbances; in particular, circulatory shock is broadly defined as circulatory failure including low blood pressure and the body's inability to maintain organ perfusion and to meet oxygen demands. In the absence of mechanisms that function to maintain blood pressure within a normal range of values, blood pressure decreases dramatically. As a consequence, tissues can suffer from damage as a result of too little delivery of oxygen to cells. Depending on its severity, shock can be divided into three separate stages: (i) the non-progressive or compensated stage; (ii) the progressive stage; and (iii) the irreversible stage. All types of circulatory shock exhibit one or more of these stages, regardless of their causes.

Without medical intervention, progressive shock leads to irreversible shock. Irreversible shock leads to death, regardless of the amount or type of medical treatment applied. In this stage of shock, the damage to tissues, including cardiac muscle, is so extensive that the patient is destined to die even if adequate blood volume is re-established and blood pressure is elevated to its normal value. Irreversible shock is characterized by decreasing function of the heart and progressive dilation of peripheral blood vessels. Patients suffering from shock are normally placed in a horizontal plane, usually with the head slightly lower than the feet, and oxygen is often supplied. Replacement therapy consists of transfusions of whole blood, plasma, artificial solutions called plasma substitutes and physiological saline solutions administered to increase blood volume. In some circumstances, drugs that enhance vasoconstriction are also administered. Occasionally, such as in patients in anaphylactic shock, anti-iflammatory substances such as glucocorticoids and antihistamines are administered. The basic objective in treating shock is to reverse the condition so that progressive shock is arrested, to prevent it from progressing to the irreversible stage and to cause the condition to be reversed so that normal blood flow through tissues is re-established.

The causes of circulatory shock are many (Steingrub, 1998). The main causes of shock include: (i) inadequate circulating volume, as occurs in haemorrhage, burns or sepsis; (ii) loss of autonomic control of the vasculature, as occurs in the central nervous system (CNS) lesions; (iii) impaired cardiac function; and (iv) elevated peripheral demand, as occurs in sepsis. In the first case, a reduced blood volume lowers cardiac output by reducing ventricular filling pressure. In the second case, loss of vascular tone causes venous pooling and arteriolar dilation, which again reduce the ventricular filling pressure. In the third case, the heart itself is the impediment to the circulation of blood, and in these patients, the filling pressure is often elevated. In the fourth case, the cardiac output and filling pressure may be normal but cannot meet the elevated requirements of the periphery.

Blood pressure is an unreliable indicator of the shock state. Many people equate shock with hypotension. It must be stressed that an inadequate cardiac output rather than a low blood pressure is the primary lesion in this syndrome. Because the body has many mechanisms for defending the blood pressure (baroreflex, renin–angiotensin system, carotid bodies, antidiuretic hormone, etc.), the body will meet a sudden drop in cardiac output with an intense peripheral vasoconstriction that may temporarily maintain the blood pressure. The signs of reduced cardiac output can still be seen, however, and will include pale, cold skin as well as low urine production (oliguria) due to reduced renal blood flow. The circulating catecholamines will cause sweating even though the skin is cold. The patient will often complain of thirst as the CNS tries to increase fluid intake in an attempt to restore blood volume. Although most of the peripheral vasculature may reflexively be vasoconstricted, in the early phases of shock, the cerebral and coronary circulations are exceptions. These two vital organs retain their normal autoregulation. Confusion and impaired reasoning are often the first signs of inadequate perfusion of the brain. Myocardial ischaemia will occur if blood pressure falls below 50 mmHg and at even higher pressures if coronary artery disease is present (Siegel et al., 1967). If the hypotension is severe, myocardial ischaemia can depress the heart, which will further lower the blood pressure. Once this positive feedback situation begins, the circulation can collapse suddenly. Injury to other organs can be more insidious. Reduced blood flow to the renal cortex for more than a day can result in death of cortical tissue and renal failure.

Pressor amine therapy in circulatory shock has been generally unfavorable, presumably because these drugs produce unselective, intense vasoconstriction and curtail rather than improve true capillary inflow, distribution and outflow in the microcirculation. Vasoactive molecules [an analog of vasopressin, (2- phenylalanine, 8-ornithine)vasopressin] exert selective microvascular effects and are highly beneficial in therapy of low-flow states (Altura, 1976).

There is no specific indication for the routine use of alpha- or beta-adrenergic receptor agonists. These agents may increase blood pressure or cardiac output, but nutritive flow is not necessarily improved. Comparable limitations are observed with alpha-adrenergic receptor blocking agents. However, selective effects on the myocardium and on the resistance, exchange, and capacitance vessels may be advantageous as an interim and complementary measure (Weil et al., 1975).

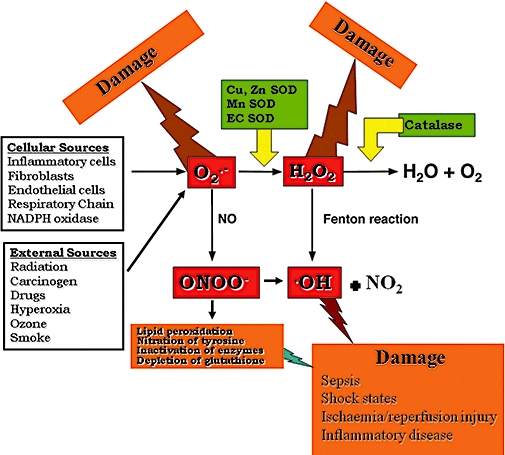

As a central element of the network of inflammatory shock mediators, superoxide and/or OONO− contribute significantly to organ dysfunction through multiple mechanisms (Figure 1). Even so, the most important feature of the shock state that ultimately determines survival is the reversibility of inadequate organ perfusion secondary to loss of vasomotor tone, which in turn leads to reduced venous return, cardiac output and severe arterial hypotension (American College of Chest Physicians – Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference, 1992). Macarthur et al. (1999) have published experimental evidence suggesting that OONO− is involved in the development of hyporeactivity to exogenous norepinephrine in endotoxemia.

Figure 1.

In the process of normal cellular metabolism, oxygen undergoes a series of univalent reductions, leading sequentially to the production of superoxide, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and H2O. Reactive oxygen species, which are thought to have relevance to vascular biology, include superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrite, lipid hydroperoxides and hydroperoxy-radicals and probably hydroxyl-like radicals. Both hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite are generated as reaction products of the superoxide anion. While hydrogen peroxide mainly emerges from intra and extracellular dismutation of superoxide by the abundantly present superoxide dismutases, peroxynitrite is formed by the rapid reaction of superoxide with nitric oxide.

NO is synthesized in both endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells by enzymatic oxidation of L-arginine by NO synthase (NOS) (Thiemermann, 1994). NO diffuses through membranes and activates guanylyl cyclase, which increases cellular cGMP. The resulting activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase leads to smooth muscle relaxation and decreased tone (Matheis et al., 1992). Interruption of this pathway by an imbalance of ROS leads to changes both in vascular tone and in signalling initiated by the newly formed free radicals. In addition, the production of O2 in vascular cells creates both an imbalance in NO· signalling and changes in several intracellular signalling pathways. An important source of extracellular O2 is the oxidation of xanthine by xanthine oxidase, which binds to glycosaminoglycan sites in the arterial wall (Li and Shah, 2004). Therefore, xanthine is the limiting factor for production of O2 through this pathway, and increased production of xanthine has been demonstrated through catabolism of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) in hypoxic conditions. Another source of O2 in the vasculature is specific NAD(P)H oxidases, which is the primary source for smooth muscle-derived ROS (Cai, 2005). Agonists such as angiotensin II and tumour necrosis factor-α increase membrane associated NADH-dependent O2 production in vascular smooth muscle cells, and this activity can be blocked by a flavoprotein inhibitor. (Wolf, 2000; Li and Shah, 2004)

Numerous cell types release superoxide anions during the inflammatory response and these include endothelial cells, epithelial cells, macrophages and neutrophils (Mannaioni et al., 1991; Okayama et al., 1999). Their activation at the site of injury may contribute to O2 production and subsequent damage. Neutrophils are probably the main source for the release of superoxide (Fantone and Ward, 1982) and presumably play a major role in the generation of OONO−.

Among molecular mechanisms implicated in the pathophysiology of shock, the adenosine and endocannabinoid receptors play a novel and original role. There is evidence suggesting that endocannabinoids are overproduced during various forms of I/R, such as myocardial infarction or whole body I/R associated with circulatory shock, and may contribute to the cardiovascular depressive state associated with these pathologies. CB2 receptor activation is protective against myocardial, cerebral and hepatic I/R injuries by decreasing the endothelial cell activation/inflammatory response (for example, expression of adhesion molecules, secretion of chemokines), and by attenuating the leukocyte chemotaxis, rolling, adhesion to endothelium, activation and transendothelial migration, and interrelated oxidative/nitrosative damage (Pacher et al., 2006; Pacher and Haskó, 2008). Moreover, several studies identify the A2BAR as a modulator of inflammatory cytokines, expression of adhesion molecules and of leukocyte adhesion, and rolling on blood vessels (Haskóet al., 2008).

Oxygen-derived free radicals: superoxide and ·OH

The vascular endothelium may be considered as the major target for the effects of oxidant stress and is responsible for the generation of free radicals (Lefer et al., 1991). Evidence that reactive nitrogen and oxygen species can exert pro-inflammatory properties includes recruitment of neutrophils at sites of inflammation, formation of chemotactic factors (Harlan, 1987), DNA damage, depolymerization of hyaluronic acid and collagen, lipid peroxidation and release of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β (Grisham et al., 1999).

Thus, oxidative stress compromises normal endothelial properties such as vasorelaxation and inhibition of thrombosis by inactivation of NO (Okayama et al., 1999). Evidence suggests that ROS-mediated endothelial dysfunction participates in many pathological settings, including arteriosclerosis, hypertension, thrombosis, diabetes, cardiopulmonary bypass, ischaemia reperfusion, the acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary edema, hyperoxia and hypoxia (Alom-Ruiz et al., 2008). ROS may lead to endothelial death resulting in severe vascular injury, haemorrhage and thrombosis. Oxidative stress to the endothelium can be initiated and/or propagated by oxidants generated in the cellular milieu (plasma, other vascular cells, extracellular matrix, adjacent alveolar compartment), released by activated leukocytes or generated by activated endothelial cells themselves under pathological conditions. Exposure of the endothelium to potentially injurious pro-oxidative compounds circulating in the bloodstream and formed in the tissues, such as oxidized lipoproteins and oxidants released from activated platelets, has been implicated in vascular injury in ischaemia and reperfusion (Szocs, 2004). Endothelium can generate ROS under pathological conditions for a more prolonged period of time than leukocytes, albeit at a lower rate and amplitude. Therefore, when ROS generation exceeds endothelial antioxidant defence mechanisms, endothelial cells may undergo apoptotic or necrotic dead leading to vascular injury.

Vascular injury induced by ischaemia-reperfusion is a stimulus for leukocyte–endothelial interaction (Harlan, 1985). Leukocyte–endothelial interaction involves a complex interplay among adhesion glycoproteins (i.e. integrins, immunoglobulin superfamily members and selectins). One member of the selectin family, P-selectin, is rapidly trasnlocated from the Weibel-Palade bodies to the endothelial cell surface upon endothelial cell activation with thrombin, histamine, hypoxia-reoxygenation or oxygen-derived free radicals (Lorant et al., 1991; Patel et al., 1991). P-selectin promotes rolling of leukocytes on the endothelium. Leukocytes' rolling is the first step in leukocytes–endothelial interaction and facilitates polymorphonucleate cells (PMNs) activation and adherence (Lorant et al., 1991; 1993). However, leukocyte accumulation is a complex phenomenon, which also involves endothelium-based adhesion molecules. Intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) is an adhesion molecule normally expressed at a low basal level, but its expression can be enhanced by various inflammatory mediators such as IL-1 and TNF-α (Shreeniwas et al., 1992; Wetheimer et al., 1992).

Superoxide is a pro-inflammatory mediator. Some of the pro-inflammatory properties of superoxide include recruitment of neutrophils at sites of inflammation, formation of chemotactic factors, DNA damage, initiation of lipid peroxidation, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β via activation of nuclear factor-kB (Guzik et al., 2003). The pro-inflammatory effects of superoxide are then perpetuated by the formation of OONO−, which also deactivates (upon nitration) SOD (Ischiropoulos et al., 1992).

While H2O2 does not possess an unpaired electron and, therefore, is not a free radical per se, it is usually classified as a reactive oxygen intermediate or species. H2O2 can diffuse through membranes and has a half-life much longer than that of superoxide. H2O2 has several fates intracellularly. It can be metabolized by one or two anti-oxidative enzymes, i.e. glutathione peroxidase or catalase, and, in the worst case, in the presence of the transition metals Fe2+ or Cu1+, it is decomposed to ·OH via the Fenton reaction (Meneghini and Martins, 1993).

In some cases, these newly formed radicals can be toxic and, in fact, may initiate other damaging free radical reactions. An example of chain reaction is lipid peroxidation, where the lipid peroxyl radical, once produced, abstracts a hydrogen atom from a neighouring polyunsaturated fatty acid to continue the process, converting itself into a lipid peroxide. The end result of extensive lipid peroxidation is cell death. A radical can also interact with another radical to form a stable molecule. This is what happens when superoxide reacts with NO to form OONO− (Goldstein and Merényi, 2008).

It has been known since the mid-1970s that superoxide interacts with catecholamines (these are in fact considered as antioxidants), converting them to adrenochromes (Matthews et al., 1985; Bindoli et al., 1990). Adrenochromes have been shown to be cardiotoxic and to cause myocardial necrosis (Singal et al., 1982). If true, such adrenochrome-mediated cardiotoxicity would have adverse consequences for subjects with pre-existing compromise of ventricular function and systemic oxygen delivery owing to coronary artery disease, hypertension and other conditions. Moreover, the possibility exists that adrenochromes may have similarly toxic effects on other organ systems, which may well contribute to the morbidity and mortality of shock.

High-energy oxidants: OONO−

OONO− is thought to posses a dual free radical nature capable of ·OH -like lipid peroxidation and NO2-driven nitration of tyrosine. Stability of OONO− is pH dependent, with protonation resulting in either decomposition into predominantly nitrate or the initiation of oxidative processes, including lipid peroxidation and the nitration of tyrosine (Beckman, 1996). OONO− is a powerful oxidant that is highly reactive toward biological molecules, including protein and non-protein sulfhydryls, DNA and membrane phospholipids (Cuzzocrea et al., 2000; Pacher et al., 2007; Szabóet al., 2007). OONO− is also stable enough to cross several cell diameters to reach target cells before becoming protonated and decomposing (Karoui et al., 1996). Nevertheless, OONO− does deactivate catecholamines (Graham, 1978), is present in endotoxin shock (Szabo, 1996) and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of shock (Szabóet al., 2007). OONO− rapidly oxidizes the fluorescent probe dihydrorhodamine 123 to rhodamine 123 in vitro. The production of OONO− can be evidenced as increased oxidation of dihydrorhodamine 123 to rhodamine 123 in plasma (Wrona et al., 2005). Caution should be exercised with this method: oxidation of dihydrorhodamine can be triggered by oxidants other than OONO− (·OH, e.g.). However, a NOS inhibitor inhibitable component of an increased oxidation of dihydrorhodamine can be taken as a relatively specific evidence of an effect of OONO−.

Since it has been demonstrated that the increase in the dihydrorhodamine oxidation in the plasma upon reperfusion can be inhibited by the NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (Szabo et al., 1995), it has been proposed that the oxidation of dihydrorhodamine under theses experimental conditions is due to OONO−, rather than ·OH.

Nitrotyrosine formation, along with its detection by immunostaining, was initially proposed as a relatively specific means for detection of the footprint of OONO− (Ischiropoulos et al., 1992).The presence of nitrotyrosine at the site of injury does not prove, however, that OONO− caused the damage but simply that it is formed. Increased nitrotyrosine staining is thus considered an indication of increased nitrosative stress rather than a specific marker of OONO−. The formation of nitrotyrosine has recently been demonstrated in various organs of rats subjected to experimental shock; the staining was abolished by treatment of the animals with an inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibitor and OONO− scavenger (Cuzzocrea et al., 1999).

OONO− possesses a number of independent pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic mechanisms including (i) the initiation of lipid peroxidation; (ii) the inactivation of a variety of enzymes; and (iii) depletion of glutathione. Moreover, OONO− can also cause DNA damage resulting in the activation of the nuclear enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase (PARS) (Szabóet al., 1997a,b; Szabo, 1998; Pacher and Szabo, 2008), depletion of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and ATP, which lead to irreversible cellular damage (Szabo, 1999). In in vitro studies, it has been established that antioxidants such as cysteine, glutathione, ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol are scavengers of OONO− and inhibitors of its oxidant capacity (Radi et al., 1991; Pryor and Squadrito, 1995; Karoui et al., 1996). Recent studies demonstrate that endogenous glutathione plays an important role in reducing vascular hyporeactivity and endothelial dysfunction in response to OONO−. In fact, some data support that depletion of endogenous glutathione enhances the cytotoxic effects of H2O2 and oxyradicals as well; we have also observed an enhancement of the H2O2 toxicity in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (Cuzzocrea et al., 1998). These findings are in agreement with previous suggestions that glutathione plays an important role in blocking the oxidant-induced injury and, specifically, against the OONO−-induced injury (Cuzzocrea et al., 1998). These results points out the importance of intact glutathione pools, as protective mechanisms against the vascular failure under conditions of oxidant stress. These strategies may represent alternative or additional approaches to other advances directed towards the prevention of the loss of vascular patency in shock.

OONO− also nitrates and inhibits myofibrillar creatine kinase (an enzyme critical in myocyte contractility) and, as such, might contribute to heart failure post-myocardial reperfusion injury (Mihm et al., 2001a,b).

Moreover, OONO− is an important trigger of apoptosis in various cell types (Levrand et al., 2006), may modulate different signalling pathways (Pacher et al., 2005; Pesse et al., 2005), leads to mitochondrial dysfunction (Radi et al., 2002; Moon et al., 2008) and also to matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation (Schulz, 2007).

The exact contribution of OONO− in shock states awaits preclinical evaluation of agents, which remove OONO− such as the OONO− decomposition catalysts. Some of these are anti-inflammatory (Salvemini et al., 1998a) and cytoprotective (Misko et al., 1988) and do protect against endotoxin-induced intestinal damage (Salvemini et al., 1999a). Therefore, the evidence implicating the role of OONO− in a given pathophysiological condition can only be indirect. A simultaneous protective effect of superoxide neutralizing strategies and NO synthesis inhibition, coupled with the demonstration of OONO− in the particular pathophysiological condition, can be taken as a strong indication for the role of OONO−.

SOD mimetics (SODm)

Interventions, which reduce the generation or the effects of ROS, exert beneficial effects in a variety of models of ischaemia and reperfusion. Antioxidant drugs can be divided in non-enzymatic antioxidants (scavengers) and antioxidant enzymes. However, scavengers are consumed by ROS, and, therefore, relatively high concentrations are required. Antioxidant enzymes, SOD and catalase, are not consumed and have high affinities and rates of reaction with ROS. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that the enzymes afford more effective protection against acute massive oxidative insults. SOD and other dissimulating agents prevent the reaction of superoxide anion with NO and the formation of the strong oxidant, peroxynitrate, thereby protecting against oxidative stress and maintaining the normal regulatory functions of NO.

Superoxide is enzymatically reduced to H2O2 in the presence of a ubiquitously distributed enzyme, SOD (McCord and Fridovich, 1969). There are two forms of SOD: the Mn enzyme present in mitochondria (SOD2) and the Cu/Zn enzyme present in the cytosol (SOD1) and extracellular surfaces (SOD3). The importance of SOD2 is highlighted by the findings that in contrast to SOD1 and SOD3 (Fridovich, 1995), the SOD2 knockout is lethal to mice (Carlsson et al., 1995; Lebovitz et al., 1996; Reaume et al., 1996). However, in many disease states, there is an imbalance between the amount of superoxide formed and the ability of SOD enzyme to remove them: this leads to superoxide-driven damage. Under normal circumstances, the levels of superoxide (produced by the one electron reduction of molecular oxygen) are kept under tight control by endogenous SOD enzymes, the enzymatic activity of which was discovered in 1969 by McCord and Fridovich (1969).

Superoxide is formed via a large number of pathways, including normal cellular respiration, inflammatory cells, endothelial cells and in the metabolism of arachidonic acid.

Most of the knowledge obtained about the roles of superoxide anion in disease has been gathered using the native SOD enzyme and, more recently, by data generated in transgenic animals that overexpress the human enzyme (Chen et al., 1998; 2000). Protective and beneficial roles of SOD have been demonstrated in a broad range of diseases, both preclinically and clinically (Ma et al., 1992; Hangaishi et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001). Excessive release of superoxide anion contributes to tissue damage seen post-reperfusion in several ischemic organs including kidney (Yin et al., 2001), stomach (Yoshikawa et al., 1990), intestine (Zimmermann et al., 1993), skin (Goossens et al., 1990) and heart (Ambrosio and Flaherty, 1992; Grill et al., 1992). In the heart, a number of studies have shown that removal of superoxide with the native SOD enzyme (Burton, 1985; Ma et al., 1992) or with overexpression of the human manganese SOD enzyme (Chen et al., 1998) protects against myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion injury. In addition, preclinical studies have revealed that SOD enzymes have a protective effect in animal models of transplant-induced reperfusion injury (Zweier, 1997), inflammation (Oyanagui, 1976; Shingu et al., 1994), Parkinson's disease (Klivenyi et al., 1998), cancer (Bravard et al., 1992; Church et al., 1993; Safford et al., 1994), AIDS (Edas et al., 1997; Mollace et al., 2001) and various pulmonary disorders (Barnes, 2000; Salminen et al., 2001). Under these circumstances, use of transgenic animals that overexpress the SOD enzyme has led to some important observations.

Although the native enzyme has shown promising efficacy, there were major drawbacks associated with its use as a viable therapeutic agent. However, there are problematic issues associated with the use of the native enzymes as therapeutic agents (e.g. solution instability, immunogenicity of non-human enzymes, bell-shaped dose response curves, high susceptibility to proteolytic digestion) and as pharmacological tools (e.g. they do not penetrate cells or cross the blood brain barrier, limiting the dismutation of superoxide only to the extracellular space or compartments). To overcome the limitations associated with native enzyme therapy, a series of SODm that catalytically remove O2− were developed.

However, inhibitors of the inducible form of NOS such as aminoguanidine and N-iminoethyl-L-lysine attenuate hypotension, but they do not improve mortality (Thiemermann et al., 1995; Wray et al., 1998). Treatments targeting the inflammatory cascade, especially the inhibition of the NO pathway, remain unreliable as in myocardial infarction as in sepsis. However, human trials to undertaking the setting of cardiogenic shock evaluated compounds with little selectivity for iNOS and their failure may have been due, in part, to the inhibition of the other NOS isoforms (Bailey et al., 2007). In addition, results from iNOS knockout mice have been controversial, with some reporting reduced hypotension in shock models while others reporting no effects or detrimental ones (Nicholson et al., 1999).

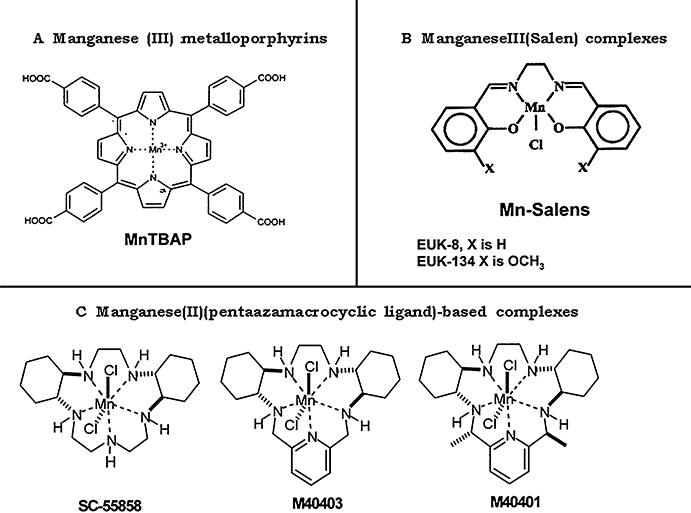

These SODm are manganese(II)-containing, non-peptidic molecules that possess the function and catalytic rate of native SOD enzymes, but with the advantage of being a much smaller molecule (MW 483 vs. MW 30 000 for the mimetic and native enzyme respectively) (Salvemini et al., 1999b; Aston et al., 2001). One important property is that they catalytically remove superoxide at a high rate without interacting with other reactive species including NO, OONO−, H2O2, oxygen or ·OH (Riley et al., 1997; 1999). In fact, using such agents, the deactivation of exogenous and endogenous catecholamines accounts for the hyporeactivity and hypotension (respectively) seen in septic shock (Graham, 1978). The selectivity of the SODm for superoxide is not shared by other classes of SODm or scavengers including several metalloporphyrins such as tetrakis-(N-ethyl-2-pyridyl) porphyrin and tetrakis-(benzoic acid)porphyrin that interact with other reactive species such as NO and peroxinitrite (Patel and Day, 1999) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Synthetic superoxide dismutase mimetics superoxide is shown. MnTBAP, Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin; EUK-8, manganese N,N′-bis(salicyldene)ethylenediamine chloride; EUK-134, manganese 3-methoxy-N,N′-bis(salicyldene)ethylenediamine chloride; M40403 and M40401, Mn(II)(penta-azamacrocyclic ligand)-based complexes SC-55858, M40403 and M40401.

SODm may thus offer an important and future line of therapy (McCord, 1985).

The manganese moiety of the porphyrin-based SODm functions in the dismutation reaction with superoxide by successive reduction followed by oxidation changes in its valence between Mn(III) and Mn(II), much like native SODs, whereas the catalase activity of metalloporphyrins could be attributed to their ability to also undergo oxidation to higher oxidation states as Mn(IV) or Mn(V) or Mn(IV)(porphyrin radical cation) oxidation levels. In general, metalloporphyrins with higher SOD activity possessed greater catalase activity. At micromolar levels, they protect cultured cells against the toxicity of superoxide generators and OONO− injury produced by endotoxin (Szabóet al., 1996) or OONO− itself (Crow, 2000). Metalloporphyrins such as Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) are also potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation (Day et al., 1999) exerting protective effect against some of the detrimental effects associated with endotoxic and haemorrhagic shock (Zingarelli et al., 1997) as well as in acute liver failure (Ferret et al., 2001; Malassagne et al., 2001). Since these SODm scavenge other ROS including OONO−, the efficacy of MnTBAP in these models probably relates to its OONO−-scavenging activity in addition to its superoxide-scavenging activity (Zingarelli et al., 1997). Therefore, one general limitation of these porphyrin-based SODms, is that they react not only with superoxide but also with a wide variety of ROS.

The Mn(III)salen complexes, have been reported to be superoxide scavengers/SOD mimics and possess catalase activity (Faulkner et al., 1994; Doctrow et al., 1997). Biological studies have been published for two of these complexes, EUK-8 and EUK-134, in several disease models related to oxidative stress including stroke, ischaemia-reperfusion injury, Parkinson's disease and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (Gianello et al., 1996; Pucheu et al., 1996; Tanguy et al., 1996; Malfroy et al., 1997). In addition, it has been demonstrated that EUK-134, a non-selective SODm, attenuates the multiple organ injury and dysfunction caused by endotoxin in the rat (Bianca et al., 2002), as well as that EUK-8 significantly attenuated many of the features of lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced acute lung injury in swine (Gonzalez et al., 1995), including arterial hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, decreased dynamic pulmonary compliance and pulmonary edema but did not have an effect on circulating plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-α, thromboxane B2 or 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α (Gonzalez et al., 1995; 1996). Similarly, treatment of rats with EUK-134 attenuated the renal dysfunction as well as the liver and skeletal muscle injury (but not the pancreatic injury) caused by endotoxin but did not prevent the LPS-induced hypotension (Bianca et al., 2002).

Manganese(II)(pentaazamacrocyclic ligand)-based SODm such as M40403 are selective for superoxide (in contrast to the other two complexes) and are derived from the 15-membered macrocyclic ligand, 1,4,7,10,13-pentaazacyclopentadecane, containing the added bis(cyclohexylpyridine) functionalities (Salvemini and Riley, 2000). One prototype, M40403, is a stable low molecular weight, manganese-containing, non-peptidic molecule possessing the function, and catalytic rate of native SOD enzymes but with the advantage of being a much smaller molecule (MW 483 vs. MW 30 000 for the mimetic and native enzyme respectively) (Salvemini et al., 1999b; Salvemini and Riley, 2000). An important property of this class of SODm is that they catalytically remove superoxide anion at a high rate selectively without reacting with other biologically relevant oxidizing species, such as NO, OONO−, H2O2, hypochlorite or oxygen (Riley et al., 1997; 1999).

The unique selectivity of mimetics such as M40403 resides in the nature of the manganese(II) center in the complex. The resting oxidation state of the complex is the reduced Mn(II) ion; as a consequence, the complex has no reactivity with reducing agents until it is oxidized to Mn(III) by protonated superoxide, whereupon, the complex is rapidly reduced back to the Mn(II) state by the superoxide anion at diffusion-controlled rates. Since the complex is so difficult to oxidize, many one-electron oxidants cannot oxidize this and its related complexes (including NO and oxygen). Furthermore, since the SODm operate via a facile one-electron oxidation pathway, other two-electron non-radical but nevertheless potent oxidants are not kinetically competent to oxidize the Mn(II) complex, e.g. OONO−, H2O2 or hypochlorite. Thus, M40403 and other complexes of this class of SODm can serve as selective probes for deciphering the role of superoxide anion in biological systems where other such relevant biological oxidants may be present and be expected to play a role.

Superoxide anions increase neutrophil adhesion and infiltration (Dreyer et al., 1991) presumably by generating chemotactic mediators such as leukotriene B4 (Al-Shabanah et al., 1999) or by activating transcription factor such as NFkB (Adcock et al., 1994) which in turn up-regulates adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 (Farhood et al., 1995). Inhibition of superoxide prevents the infiltration of neutrophils at inflamed sites (Hardy et al., 1994) as shown by the use of the native SOD enzyme, by experiments performed in transgenic mice that overexpress the human CuZnSOD enzyme (Przedborski et al., 1992) and by SODm such as SC-55858 (Lowe et al., 1996), M40403 and M40401 (Macarthur et al., 2000; Salvemini and Riley, 2000; Cuzzocrea et al., 2001a,b; Salvemini et al., 2001a,b; Masini et al., 2002).

The tandem activity of SOD and catalase would be ideal for antioxidant therapies (Baker et al., 1998). Catalase is a heme-containing tetrameric protein (M = 240 kDa) that safely degrades H2O2 to water and oxygen. It has been proposed more than two decades ago that SOD and catalase might be used to protect against oxidative stress. Indeed, protective and beneficial roles of SOD have been demonstrated in a broad range of disease, both preclinically and clinically (Babior, 1982; Flohe, 1988; Bravard et al., 1992; Shingu et al., 1994).

These synthetic SODm, exemplified by the M40403 and M40401, are stable, low molecular weight, manganese-containing, non-peptidic molecules possessing the function and catalytic rate of native SOD enzymes (Salvemini et al., 1999b; Inagi, 2006). Thus, SODm can serve as selective probes for deciphering the role of superoxide in biological systems where other such relevant biological oxidants may be present.

An important mechanism by which SODm attenuate ischaemia and reperfusion injury is by reducing OONO− formation by simply removing superoxide anion before it can react with NO.

SODm inhibit a number of inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 as shown in models of ischaemia and reperfusion injury, and septic shock (Salvemini and Cuzzocrea, 2002; 2003; Macarthur et al., 2003). Although the mechanism through which superoxide increases cytokine releases are not well defined, it is known that superoxide or OONO− can directly release TNF-α from macrophages/human monocytes (De Warra et al., 1997; Volk et al., 1999) by activating the transcription factors NFkB system and AP1 (Matata and Galinanes, 2001). SODm or the SOD enzyme block inflammation without affecting iNOS expression or release of NO (Krieglstein et al., 2001). In addition, superoxide anion by interacting with NO destroys the biological activity of this mediator (Gryglewski et al., 1986), attenuating important tissue protective properties of NO namely: maintenance of blood vessel tone, platelet reactivity and cytoprotective effects in numerous organs (including heart intestine and kidney), and release of anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective prostacyclin (via activation of the constitutive cyclooxygenase enzyme (Salvemini et al., 1993). Therefore, removal of superoxide protects NO and reduces the formation of the cytotoxic OONO−. Superoxide anion and OONO− induce DNA single-strand damage that is the obligatory trigger for PAR polymerase activation (Inoue and Kawanishi, 1995; Salgo et al., 1995), resulting in the depletion of its substrate NAD+in vitro and a reduction in the rate of glycolysis. As NAD+ functions as a cofactor in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, NAD+ depletion leads to a rapid fall in intracellular ATP and, ultimately, cell injury (Szabó and Dawson, 1999). In light of the role of PAR polymerase in inflammation, it is possible that PAR polymerase inhibition by SODm accounts for their protective effect in ischaemia and reperfusion.

A possible mechanism by which SODm attenuates neutrophil infiltration is by down-regulating adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 and P-selectin. Thus, inhibition of neutrophil infiltration at sites of reperfusion injury correlated well with the inhibition of both ICAM-1 and P-selectin (Wang and Doerschuk, 2002), supporting the involvement of superoxide in the regulation of adhesion molecules.

OONO− decomposition catalysts

OONO− is formed during ischaemia and reperfusion of many organs (Ferdinandy et al., 2000; Levrand et al., 2006; Moon et al., 2008), and is an important pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic molecule (Beckman et al., 1990; Ischiropoulos et al., 1992; Crow and Beckman, 1995; Salvemini et al., 1998b). Removal of OONO− is cytoprotective (Stern et al., 1996) and anti-inflammatory (Salvemini et al., 1996). Nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity has been found in cardiac tissues obtained from patients with myocarditis (Kooy et al., 1997), suggesting a role for OONO− in inflammation-associated myocardial dysfunction in humans.

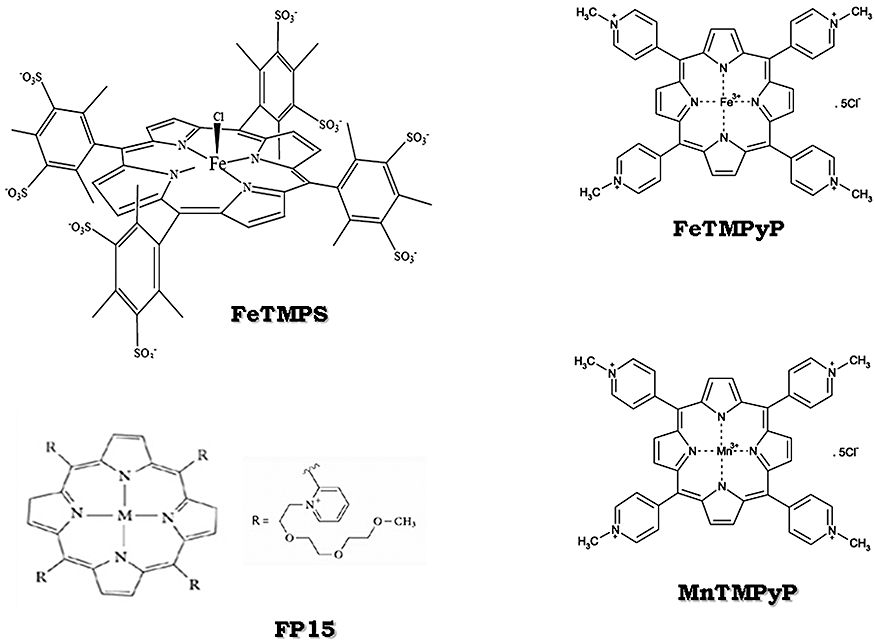

Some of OONO− decomposition catalysts (Stern et al., 1996; Szabóet al., 2007) are anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective and do protect against endotoxin-induced intestinal damage (Salvemini et al., 1998a) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Peroxynitrite decomposition catalysts are shown. FeTMPS, iron(III) meso-tetra(2,4,6-trimethyl-3,5-disulfonato)porphirin chloride; FeTMPyP, iron (III) tetrakis(N-methyl-4′-pyridyl)porphyrin; MnTMPyP, manganese (III) tetrakis (1-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin; FP15, FeCl tetrakis-2-(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether) pyridyl porphyrin.

We can hypothesize that the mechanism of this OONO− decomposition catalyst may be related to a prevention of OONO−-induced endothelial injury as well as to the inhibition of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates pro-inflammatory properties (Cuzzocrea et al., 2000). OONO− decomposition catalyst would intercept the positive feedback cycle in shock at the level of endothelial injury and cytokine release. This model would explain the reduction of cytokine formation and the reduction of P-selectin and ICAM-1 and PMNs infiltration during reperfusion in the OONO− decomposition catalyst-treated rats.

Water-soluble porphyrins, such as iron(III) meso-tetra(2,4,6-trimethyl-3,5-disulfonato)porphirin chloride (FeTMPS) and iron(III) meso-tetra(N-methyl4-pyridyl)porphin chloride (FeTMPyP), have been shown to react catalytically with OONO−. Mn(III)tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)porphyrin (MnTBAP), a stable and cell-permeable SODm, and related compounds may also inhibit the oxidation of dihydrorhodamine 123 elicited by authentic OONO−. However, MnTBAP is not a scavenger of NO.

OONO− is known to undergo acid-catalysed decomposition by two distinct pathways. Isomerization to nitrate is the major decay route, but a significant portion of the decomposition produces a species with reactivity akin to that of a ·OH. The water-soluble iron (III) porphyrins are highly active ONOO− decomposition catalysts and they function by catalysing the isomerization of ONOO− almost exclusively to nitrate. Catalysis is proposed to proceed via an oxo-Fe(IV) intermediate generated from the metal-promoted cleavage of the O–O bond. Subsequent recombination with NO2 regenerates the Fe(III) state and produces nitrate. These catalysts thus dramatically increase the rate of ONOO− isomerization, pre-empting the formation of oxidizing radical species and generating the harmless nitrate anion. This mode of catalysis manifests itself by dramatic shifts in the resulting nitrite-to-nitrate ratio when compared with the proton-catalysed decomposition.

FeTMPS and FeTMPyP, which have been shown to be active OONO− decomposition catalysts (Shimanovich and Groves, 2001), were protected against microvascular injury, lipid peroxidation and epithelial cell injury. In addition, we have recently evidenced the efficacy of OONO− decomposition catalysts in vitro and in vivo (Cuzzocrea et al., 2000; 2006; Genovese et al., 2007). At the cellular level, the catalyst FeTMPS was cytoprotective against exogenously added OONO− with an EC50 of ≈3.5 µmol·L−1, a concentration almost 1/60th of the OONO− added. This protection correlated well with a reduction in the nitrotyrosine content of cellular proteins released after OONO− insult, an observation consistent with the proposed mechanism of action for these compounds. Neither TMPS, an inactive structurally related compound, nor free Fe was cytoprotective.

The OONO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS [5,10,15, 20-tetrakis-(4-sulfonatophenyl)-porphyrinato-iron(III)] inhibited cytokine-induced cardiac depression and decreased perfusate nitrotyrosine levels (Ferdinandy et al., 2000).

FeCl tetrakis-2-(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether) pyridyl porphyrin or FP15 have been shown to have protection in models of myocardial infarction (Bianchi et al., 2002), cytokine-induced (Szabóet al., 2002) or doxorubicin-induced (Pacher et al., 2003) or endotoxin-induced (Lancel et al., 2004) cardiac dysfunction. Moreover, treatment with the OONO− decomposition catalyst WW85 decreased lipid peroxidation, increased anti-apoptotic gene expression, decreased poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activation, decreased nitrotyrosine and improved allograft survival and function. These findings collectively suggest that OONO− plays a role in the pathology of acute cardiac transplant rejection (Pieper et al., 2005).

MnTBAP is cell-permeable SODm and OONO− scavenger. It protects endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner (EC50∼40 µmol·L−1) against paraquat (2 mmol·L−1). It inhibits the oxidation of dihydrorhodamine 123 by OONO−, but does not scavenge NO. Administration of MnTBAP to LPS-treated rats ameliorated the development of vascular hyporeactivity and development of endothelial dysfunction in the thoracic aorta ex vivo. MnTBAP also prevented endotoxin-induced decrease in mitochondrial respiration, the development of DNA single-strand breaks and the depletion of intracellular NAD+ in peritoneal macrophages ex vivo (Cuzzocrea et al., 1999). The efficacy of MnTBAP in these models probably relates to its OONO−-scavenging activity in addition to its superoxide-scavenging activity (Zingarelli et al., 1997).

Conclusions

In light of the critical roles of superoxide anion in disease and cellular signalling, these new selective, potent and stable synthetic enzymes of SOD, as represented by M40403, have broad potential both as pharmacological tools to dissect the role of superoxide in disease models and as therapeutic agents in the treatment of disease in which superoxide has been shown to be a mediator.

It is widely established that enhanced OONO− formation contributes to oxidative and nitrosative stress in a variety of cardiovascular and other pathologies. Targeting OONO− directly by OONO− decomposition catalysts and OONO− scavengers or indirectly by inhibitors of downstream targets of OONO− are stimulating new strategies for cytoprotection.

Themed Section: Endothelium in Pharmacology

Endothelium in pharmacology: 30 years on: J. C. McGrath

Role of nitroso radicals as drug targets in circulatory shock: E. Esposito & S. Cuzzocrea

Endothelial Ca2+-activated K+ channels in normal and impaired EDHF–dilator responses – relevance to cardiovascular pathologies and drug discovery: I. Grgic, B. P. Kaistha, J. Hoyer & R. Köhler

Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension: D. Versari, E. Daghini, A. Virdis, L. Ghiadoni & S. Taddei

Nitroxyl anion – the universal signalling partner of endogenously produced nitric oxide?: W. Martin

A role for nitroxyl (HNO) as an endothelium-derived relaxing and hyperpolarizing factor in resistance arteries: K. L. Andrews, J. C. Irvine, M. Tare, J. Apostolopoulos, J. L. Favaloro, C. R. Triggle & B. K. Kemp-Harper

Vascular KATP channels: dephosphorylation and deactivation: P. Tammaro

Ca2+/calcineurin regulation of cloned vascular KATP channels: crosstalk with the protein kinase A pathway: N. N. Orie, A. M. Thomas, B. A. Perrino, A. Tinker & L. H. Clapp

Understanding organic nitrates – a vein hope?: M. R. Miller & R. M. Wadsworth

Increased endothelin-1 reactivity and endothelial dysfunction in carotid arteries from rats with hyperhomocysteinemia: C. R. de Andrade, P. F. Leite, A. C. Montezano, D. A. Casolari, A. Yogi, R. C. Tostes, R. Haddad, M. N. Eberlin, F. R. M. Laurindo, H. P. de Souza, F. M. A. Corrêa & A. M. de Oliveira

Mechanisms of U46619-induced contraction of rat pulmonary arteries in the presence and absence of the endothelium: C. McKenzie, A. MacDonald & A. M. Shaw

This issue is available online at http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/121548564/issueyear?year=2009

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- O2

superoxide

- OONO−

peroxynitrite

- ·OH

hydroxyl radical

- PARS

poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adcock IM, Brown CR, Kwon O, Barnes PJ. Oxidative stress induces NFκB DNA binding and inducible NOS mRNA in the human epithelial cell line A549. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1518–1524. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shabanah OA, Mansour MA, Elmazar MM. Enhanced generation of leukotriene B4 and superoxide radical from calcium ionophore (A23187) stimulated human neutrophils after priming with interferon-alpha. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1999;106:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alom-Ruiz SP, Anilkumar N, Shah AM. Reactive oxygen species and endothelial activation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1089–1100. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altura BM. Microcirculatory approach to the treatment of circulatory shock with a new analog of vasopressin, (2-phenylalanine, 8-ornithine)vasopressin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;198:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosio G, Flaherty JT. Effects of the superoxide radical scavenger superoxide dismutase, and of the hydroxyl radical scavenger mannitol, on reperfusion injury in isolated rabbit hearts. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1992;6:623–632. doi: 10.1007/BF00052564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Chest Physicians – Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston K, Rath N, Naik A, Slomczynska U, Schall OF, Riley DP. Computer-aided design (CAD) of Mn(II) complexes: superoxide dismutase mimetics with catalytic activity exceeding the native enzyme. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:1779–1789. doi: 10.1021/ic000958v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM. Superoxide: a two-edged sword. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1982;30:141–155. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1997000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Pope TW, Moore SA, Campbell CL. The tragedy of TRIUMPH for nitric oxide synthesis inhibition in cardiogenic shock: where do we go from here? Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2007;7:337–345. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200707050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K, Marcus CB, Huffman K, Kruk H, Malfroy B, Doctrow SR. Synthetic combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics are protective as a delayed treatment in a rat stroke model: a key role for reactive oxygen species in ischemic brain injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JP. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Prog. 2000;343:269–280. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS. Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Crow JP. Pathological implications of nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrite formation. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:330–334. doi: 10.1042/bst0210330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implication for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianca R, Wayman N, McDonald M, Pinto A, Shape M, Chatterjee P, et al. Superoxide dismutase mimetic with catalase activity, EUK-134, attenuates the multiple organ injury and dysfunction caused by endotoxin in the rat. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:BR1–BR7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi C, Wakiyama H, Faro R, Khan T, McCully JD, Levitsky S, et al. A novel peroxynitrite decomposer catalyst (FP-15) reduces myocardial infarct size in an in vivo peroxynitrite decomposer and acute ischaemia-reperfusion in pigs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1201–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03953-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindoli A, Deeble DJ, Rigobello MP, Galzigna L. Direct and respiratory chain-mediated redox cycling of adrenochrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1016:349–356. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravard A, Sabatier L, Hoffschir F, Ricoul M, Luccioni C, Dutrillaux B. SOD2: a new type of tumor-suppressor gene? Int J Cancer. 1992;51:476–480. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley GB. Mediators of splanchnic organ injury: overview and perspective. In: Marston A, Bulkley G, Fiddiangreen RG, Haglund UH, editors. Splanchnic Ischemia and Multiple Organ Failure. London: Edward Arnold Publ.; 1989. pp. 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Burton KP. Superoxide dismutase enhances recovery following myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H637–H643. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.5.H637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent self-propagation of hydrogen peroxide and vascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:818–822. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163631.07205.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlet J, Cohen J, Calandra T, Opal SM, Masur H. Sepsis: time to reconsider the concept. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:964–966. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318165B886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson LM, Jonsson J, Edlund T, Marklund SL. Mice lacking extracellular superoxide dismutase are more sensitive to hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Siu B, Ho YS, Vincent R, Chua CC, Hamdy RC, et al. Overexpression of MnSOD protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in transgenic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:2281–2289. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Oberley TD, Ho Y, Chua CC, Siu B, Hamdy RC, et al. Overexpression of CuZnSOD in coronary vascular cells attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:589–596. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church SL, Grant JW, Ridenour LA, Oberley LW, Swanson PE, Meltzer PS. Increased manganese superoxide dismutase expression suppresses the malignant human melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3113–3117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow JP. Peroxynitrite scavenging by metalloporphyrins and thiolates. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1487–1494. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow JP, Beckman JS. Reactions between nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: footprints of peroxynitrite in vivo. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;34:17–43. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Zingarelli B, O'Connor M, Salzman AL, Szabò C. Effect of L-buthionine-(S,R)-sulphoximine, an inhibitor of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase on peroxynitrite- and endotoxic shock-induced vascular failure. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:525–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Costantino G, Mazzon E, De Sarro A, Caputi AP. Beneficial effects of Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP), a superoxide dismutase mimetic, in zymosan-induced shock. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1241–1251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Misko TP, Costantino G, Mazzon E, Micali A, Caputi AP, et al. Beneficial effects of peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst in rat model of splanchnic artery occlusion and reperfusion. FASEB J. 2000;14:1061–1072. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.9.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Caputi AP, Aston K, Riley DP, et al. Protective effects of a new stable, highly active SOD mimetic, M40401 in splanchnic artery occlusion and reperfusion. Br J Pharmacol. 2001a;132:19–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Caputi AP, Riley DP, Salvemini D. Protective effects of M40403, a superoxide dismutase mimetic, in a rodent model of colitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001b;432:79–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Di Paola R, Esposito E, Macarthur H, Matuschak GM, et al. A role for nitric oxide-mediated peroxynitrite formation in a model of endotoxin-induced shock. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:73–81. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.108100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BJ, Batinic-Haberle J, Crapo JD. Metalloporphyrins are potent inhibitors of lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:730–736. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Warra I, Jaccard C, Corradin SB, Chiolero R, Yersin B, Gallati H, et al. Cytokines, nitrite/nitrate, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors and procalcitonin concentrations: comparisons in patients with septic shock, cardiogenic shock and bacterial pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:607–613. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doctrow SR, Huffman K, Marcus CB, Musleh W, Bruce A, Baudry M, et al. Salen-manganese complexes: combined superoxide dismutase/catalase mimics with broad pharmacological efficacy. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;38:247–269. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60987-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer WJ, Michael LH, West MS, Smith CW, Rothlein R, Rossen RD, et al. Neutrophil accumulation in ischemic canine myocardium. Insights into time course, distribution, and mechanism of localization during early reperfusion. Circulation. 1991;84:400–411. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.1.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edas MA, Emerit I, Khalhoun Y, Lazizi Y, Cernjavski L, Levy A. Clastogenic factors in plasma of HIV-1 infected patients activate HIV-1 replication in vitro: inhibition by superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:571–578. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiserich JP, Cross CE, Jones AD, Halliwell B, Van der Vliet A. Formation of nitrating and chlorinating species by reaction of nitrite with hypochlorous acid. A novel mechanism for nitric oxide-mediated protein modification. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19199–19208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantone JC, Ward PA. Role of oxygen-derived free radicals and metabolites in leukocyte-dependent inflammatory reactions. Am J Pathol. 1982;107:395–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhood A, Mcguire GM, Manning AM, Miyasaka M, Smith CW, Jaeschke H. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) expression and its role in neutrophil-induced ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat liver. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner KM, Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Stable Mn(III) porphyrins mimic superoxide dismutase in vitro and substitute for it in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23471–23476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinandy P, Danial H, Ambrus I, Rothery RA, Schulz R. Peroxynitrite is a major contributor to cytokine-induced myocardial contractile failure. Circ Res. 2000;87:241–247. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferret PJ, Hammoud R, Tulliez M, Tran A, Trebeden H, Jaffray P, et al. Detoxification of reactive oxygen species by a nonpeptidyl mimic of superoxide dismutase cures acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in the mouse. Hepatology. 2001;33:1173–1180. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohe L. Superoxide dismutase for therapeutic use: clinical experience, dead ends and hopes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1988;84:123–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00421046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese T, Mazzon E, Esposito E, Muià C, Di Paola R, Bramanti P, et al. Beneficial effects of FeTSPP, a peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst, in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:763–780. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianello P, Saliez A, Bufkens X, Pettinger R, Misseleyn D, Hori S, et al. EUK-134, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, protects rat kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion-induced damage. Transplantation. 1996;62:1664–1666. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199612150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein S, Merényi G. The chemistry of peroxynitrite: implications for biological activity. Methods Enzymol. 2008;436:49–61. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)36004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez PK, Zhuang J, Doctrow SR, Malfroy B, Benson PF, Menconi MJ, et al. EUK-8, a synthetic superoxide dismutase and catalase mimetic, ameliorates acute lung injury in endotoxemic swine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:798–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez PK, Zhuang J, Doctrow SR, Malfroy B, Benson PF, Menconi MJ, et al. Role of oxidant stress in the adult respiratory distress syndrome: evaluation of a novel antioxidant strategy in a porcine model of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Shock. 1996;6:S23–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens DP, Rao VK, Harms BA, Starling JR. Superoxide dismutase and catalase in skin flaps during venous occlusion and reperfusion. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DG. Oxidative pathways for catecholamines in the genesis of neuromelanin and cytotoxic quinones. Mol Pharmacol. 1978;14:633–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HP, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, Weisfeldt ML, Flaherty JT. Direct measurement of myocardial free radical generation in an in vivo model: effects of postischemic reperfusion and treatment with human recombinant. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1604–1611. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90457-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham MB, Jourd'Heuil D, Wink DA. Nitric oxide. I. Physiological chemistry of nitric oxide and its metabolites: implications in inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G315–G321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeneveld ABJ, Bronsveld W, Thijs LG. Hemodynamic determinants of mortality in human septic shock. Surgery. 1986;99:140–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik TJ, Korbut R, Adamek-Guzik T. Nitric oxide and superoxide in inflammation and immune regulation. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54:469–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. In: Free radicals in biology and medicine. Baum H, Gergely J, Fanburg BL, editors. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1985. pp. 89–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hangaishi M, Nakajima H, Taguchi J, Igarashi R, Hoshino J, Kurokawa K, et al. Lecithinized Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase limits the infarct size following ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hearts in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:1220–1225. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MM, Flickinger AG, Riley DP, Weiss RH, Ryan US. Superoxide dismutase mimetics inhibit neutrophil-mediated human aortic endothelial cell injury in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18535–18540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Blood. 1985;65:513–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JM. Neutrophil-mediated vascular injury. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1987;715:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1987.tb09912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagi R. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease: a new avenue toward future therapeutic approaches. Recent Pat Cardiovas Drug Discov. 2006;1:151–159. doi: 10.2174/157489006777442450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Kawanishi S. Oxidative DNA damage induced by simultaneous generation of nitric oxide and superoxide. FEBS Lett. 1995;371:86–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai M, Martin JC, Smith CD, et al. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90431-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoui H, Hogg N, Frejaville C, Tordo P, Kalyanaraman B. Characterization of sulfur-centered radical intermediates formed during the oxidation of thiols and sulfite by peroxynitrite. ESR-spin trapping and oxygen uptake studies. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6000–6009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer JP. Free radicals as mediators of tissue injury and disease. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1993;23:21–43. doi: 10.3109/10408449309104073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klivenyi P, St Clair D, Wermer M, Yen HC, Oberley T, Yang L, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase overexpression attenuates MPTP toxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:253–258. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooy NW, Lewis SJ, Royall JA, Kelly DR, Beckman JS. Extensive tyrosine nitration in human myocardial inflammation: evidence for the presence of peroxynitrite. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:812–819. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199705000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieglstein CF, Cerwinka WH, Laroux FS, Salter JW, Russell JM, Schuermann G, et al. Regulation of murine intestinal inflammation by reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen: divergent roles of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1207–1218. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancel S, Tissier S, Mordon S, Marechal X, Deponticu F, Scherpereel A, Chopiu C, Neviere R. Peroxynitrite decomposition catalysts prevent myocardial and inflammation in endotoxemic rats. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2348–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovitz RM, Zhang H, Vogel H, Cartwright J, Jr, Dionne L, Lu N, et al. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer AM, Lefer DJ. Pharmacology of the endothelium in ischemia-reperfusion and circulatory shock. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:71–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefer AM, Tsao PS, Lefer DJ, Ma XL. Role of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of reperfusion injury after myocardial ischemia. FASEB J. 1991;5:2029–2034. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.7.2010056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrand S, Vannay-Bouchiche C, Pesse B, Pacher P, Feihl F, Waeber B, et al. Peroxynitrite is a major trigger of cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B, Bollaert PE, Charpentier C, Nace L, Audibert G, Bauer P, et al. Comparison of norepinephrine and dobutamine to epinephrine for hemodynamics, lactate metabolism, and gastric tonometric variables in septic shock: a prospective, randomized study. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:282–287. doi: 10.1007/s001340050329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1014–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Bolli R, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Guo Y, French BA. Gene therapy with extracellular superoxide dismutase protects conscious rabbits against myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:1893–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant DE, Patel KD, McIntyre TM, McEver RP, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Coexpression of GMP-140 and PAF by endothelium stimulated by histamine or thrombin: a juxtacrine system for adhesion and activation of neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:223–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant DE, Topham MK, Whatley RE, McEver RP, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, et al. Inflammatory roles of P-selectin. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:559–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI116623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D, Pagel PS, Mcgough MF, Hettrick DA, Warltier DC. Comparison of the cardiovascular effects of two novel superoxide dismutase mimetics, SC-55858 and SC-54417, in conscious dogs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;304:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TT, Ischiropoulos H, Brass CA. Endotoxin-stimulated nitric oxide production increases injury and reduces rat liver chemiluminescence during reperfusion. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:463–469. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XL, Johnson G, 3rd, Lefer AM. Low doses of superoxide dismutase and a stable prostacyclin analogue protect in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:197–204. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90073-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur H, Salvemini D, Westfall TC. Peroxynitrite is involved in the development of hyporeactivity to norepinephrine in endotoxemia. FASEB J. 1999;13:A748–A757. [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur H, Westfall TC, Riley DP, Misko TP, Salvemini D. Inactivation of catecholamines by superoxide gives new insights on the pathogenesis of septic shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9753–9758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur H, Couri DM, Wilken GH, Westfall TC, Lechner AJ, Matuschak GM, et al. Modulation of serum cytokine levels by a novel superoxide dismutase mimetic, M40401, in an E. coli model of septic shock; correlation with preserved circulating catecholamines. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:237–245. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malassagne B, Ferret PJ, Hammoud R, Tulliez M, Bedda S, Trebeden H, et al. The superoxide dismutase mimetic MnTBAP prevents Fas-induced acute liver failure in the mouse. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1451–1459. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Orr PL, Tocco G, Fedoseyeva EV, Benichou G. Prevention and suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis by EUK-8, a synthetic catalytic scavenger of oxygen-reactive metabolites. Cell Immunol. 1997;177:62–68. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannaioni PF, Masini E, Pistelli A, Salvemini D, Vane JR. Mast cells as a source of superoxide anions and nitric oxide-like factor: relevance to histamine release. Int J Tiss Reac. 1991;13:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Viviand X, Leone M, Thirion X. Effect of norepinephrine on the outcome of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2758–2765. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini E, Bani D, Sardi I, Baronti R, Bani-Sacchi T, Bigazzi M, et al. Dual role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:S78–S79. doi: 10.1007/PL00000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini E, Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Marzocco C, Mannaioni PF, Salvemini D. Protective effects of M40403, a selective superoxide dismutase mimetic, in myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion injury in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:905–917. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matata BM, Galinanes M. Peroxynitrite is an essential component of cytokine production mechanism in human monocytes through modulation of NF-{kappa}B DNA-binding activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;277:2330–2335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheis G, Sherman MP, Buckberg GD, Haybron DM, Young HH, Ignarro LJ. Role of L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway in myocardial reoxygenation injury. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H616–H620. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SB, Hallett MB, Henderson AH, Campbell AK. The adrenochrome pathway. A potential catabolic route for adrenaline metabolism in inflammatory disease. Adv Myocardiol. 1985;6:367–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini R, Martins EL. Hydrogen peroxide and DNA damage. In: Halliwell B, Aruoma OI, editors. DNA and Free Radicals. Chichester: Ellis Harwood; 1993. pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Merx MW, Weber C. Sepsis and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116:793–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]