Abstract

Background and purpose:

Piceatannol is more potent than resveratrol in free radical scavenging in association with antiarrhythmic and cardioprotective activities in ischaemic-reperfused rat hearts. The present study aimed to investigate the antiarrhythmic efficacy and the underlying ionic mechanisms of piceatannol in rat hearts.

Experimental approach:

Action potentials and membrane currents were recorded by the whole-cell patch clamp techniques. Fluo-3 fluorimetry was used to measure cellular Ca2+ transients. Antiarrhythmic activity was examined from isolated Langendorff-perfused rat hearts.

Key results:

In rat ventricular cells, piceatannol (3–30 µmol·L−1) prolonged the action potential durations (APDs) and decreased the maximal rate of upstroke (Vmax) without altering Ca2+ transients. Piceatannol decreased peak INa and slowed INa inactivation, rather than induced a persistent non-inactivating current, which could be reverted by lidocaine. Resveratrol (100 µmol·L−1) decreased peak INa without slowing INa inactivation. The inhibition of peak INa or Vmax was associated with a negative shift of the voltage-dependent steady-state INa inactivation curve without altering the activation threshold. At the concentrations more than 30 µmol·L−1, piceatannol could inhibit ICa,L, Ito, IKr, Ca2+ transients and Na+-Ca2+ exchange except IK1. Piceatannol (1–10 µmol·L−1) exerted antiarrhythmic activity in isolated rat hearts subjected to ischaemia-reperfusion injury.

Conclusions and implications:

The additional hydroxyl group on resveratrol makes piceatannol possessing more potent in INa inhibition and uniquely slowing INa inactivation, which may contribute to its antiarrhythmic actions at low concentrations less than 10 µmol·L−1.

Keywords: piceatannol, resveratrol, sodium channel, APD prolongation, antiarrhythmia

Introduction

Piceatannol (3,3′,4′,5-tetrahydroxystilbene, astringinin) is a polyphenolic stilbene phytochemical which is rich in the seeds of Euphorbia lagascae (Inamori et al., 1984) and is also present in diets of plant-derived foods and beverage such as red wine (Waffo Teguo et al., 1998). Piceatannol was identified as a selective inhibitor of non-receptor Syk tyrosine kinase (Oliver et al., 1994) which plays a critical role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses of hematopoietic cells(Peters et al., 1996; Sada et al., 2001) and in maintaining vascular integrity (Abtahian et al., 2003) in addition to playing the general physiological functions in a wide variety of non-hematopoietic cells (Yanagi et al., 2001). It was found that piceatannol possesses multiple bioactivities such as anti-cancer (Ferrigni et al., 1984; Potter et al., 2002; Aggarwal et al., 2006), anti-Epstein-Barr virus (Cooper and Longnecker, 2002), and cardioprotection associated with antiarrhythmia against ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rat hearts (Hung et al., 2001).

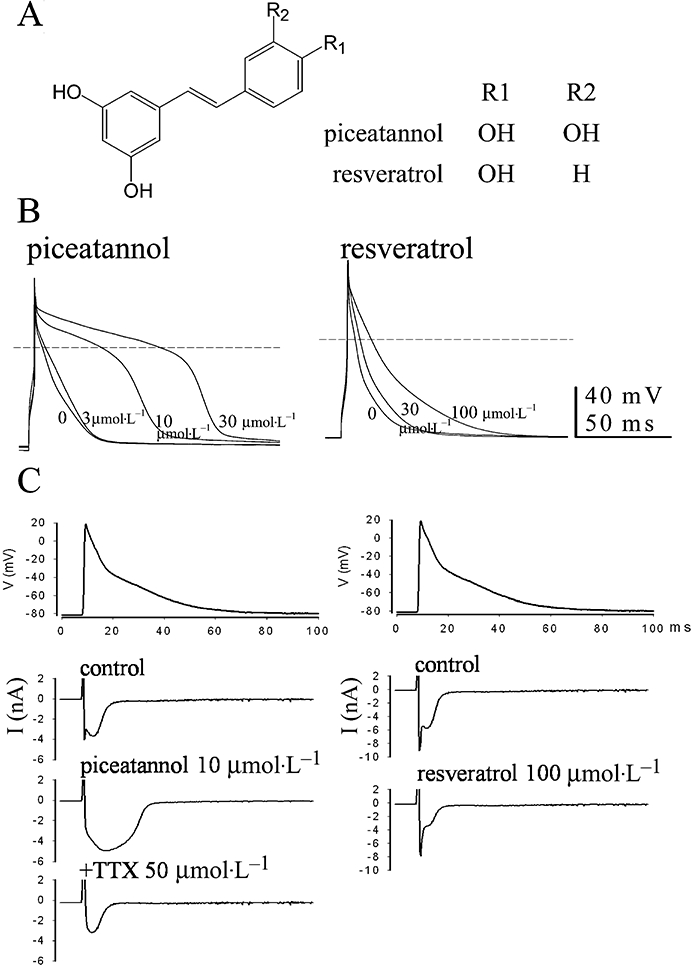

Reperfusion is associated with potentially lethal arrhythmias that are rapidly and predictably induced within seconds of the onset of reflow (Manning et al., 1984). Pretreatment of antioxidants or free radical scavengers can afford potential protection against ischaemia-induced or reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in experimental animals (Manning et al., 1984; Bernier et al., 1986). Piceatannol possesses an additional hydroxyl group on resveratrol (3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) as shown in Figure 1A and exerts higher radical scavenging activity (Fauconneau et al., 1997) which was considered to contribute to the cardioprotective and antiarrhythmic effects in ischaemic and ischaemic-reperfused rat heart (Hung et al., 2001). Our previous study found that resveratrol possesses weak cardiac ion channel blocking action which is in parallel with its less potent antiarrhythmic action in isolated rat hearts subjected to ischaemia-reperfusion injury (Chen et al., 2007). It is unclear whether piceatannol can directly modulate cardiac ion channels and the relevance to its antiarrhythmic efficacy. Besides that, the overall health benefit of polyphenolic compounds, such as piceatannol, containing in our daily diets or fortified supplement, remains to be ascertained by clinical study (Halliwell, 2007) and the cardiac safety of piceatannol yet remains to be established. Therefore, the main objective of the present work is to characterize the action of piceatannol on cardiac ion channels which could contribute to its antiarrhythmic activity or to raise the caution for the propensity to cause proarrhythmia. Although the expression of either erg mRNA or IKr channel is found in rat hearts (Wymore et al., 1997; Jones et al., 2004), the current amplitude is small in rat ventricular myocytes (Wymore et al., 1997). Hence, we examined the effect of piceatannol on IKr in HEK 293 cells transfected with hERG gene encoded IKr channel to evaluate the cardiac safety.

Figure 1.

Comparison of (A) the structures between piceatannol and resveratrol and the different response to both polyphenols in (B) the APs and (C) the action-potential-clamp-elicited inward currents in rat ventricular cells. (B) The superimposed APs were elicited at 1 Hz in current clamp mode, and the steady-state recordings in the absence or presence of the cumulatively increasing doses of either piceatannol or resveratrol were shown. The dash lines indicate the membrane potential at zero. (C) The AP contour of rat papillary muscle stimulated at 1 Hz was employed as the voltage protocol to record the inward currents affected by either piceatannol or resveratrol. Cs+ plus TEA-containing pipette internal solution was used to block potassium currents in addition to the presence of 10 mmol·L−1 Cs+ in the bath solution.

Methods

Ischaemia-reperfusion induced arrhythmia in isolated rat heart

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g body weight, purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center, NTUMC) were intraperitoneally anaesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1) plus heparin (300 U kg−1). The research was granted by National Taiwan University IACUC (approval No.:20070004), and was conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by US NIH. The rat hearts were excised and mounted immediately on the Langendorff apparatus, and retrogradely perfused via the aorta at a constant pressure (80 mm Hg) with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 gased Tyrode solution containing (mmol·L−1) NaCl 137.0, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.22, CaCl2 1.8, NaHCO3 11.9, NaH2PO4 0.33, glucose 11.0, pH 7.4, at 37°C. After a stabilization period, the hearts were subjected to ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery for 20 min followed by reperfusion. The cardiac rhythm was recorded on a chart recorder (RS 3200, Gould Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA) during the ischaemia/reperfusion period. The polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia (PVT) was defined as a run of three or more consecutive ventricular premature contractions. Reperfusion-induced PVT occurred after 20 min LAD occlusion. Once I-R-induced arrhythmia appeared, piceatannol (at the concentrations of 1, 3 and 10 µmol·L−1) or resveratrol (at the concentrations of 3, 10, 30 and 100 µmol·L−1) was administered respectively. No new tachyarrhythmia observed after drug administration was defined as a successful antiarrhythmic case.

Isolation of single ventricular myocytes

Single ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated from heart of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g. Briefly, hearts were quickly removed from pentobarbital-anaesthetized rats, and mounted via the aorta on a Langendorff retrograde perfusion apparatus. Hearts were initially perfused with oxygenated Ca2+-free HEPES solution [containing (mmol·L−1) NaCl 137.0, KCl 5.4, KH2PO4 1.2, MgCl2 1.22, glucose 10, and HEPES 10, pH 7.4], and followed by the same solution containing 0.3 mg mL−1 collagenase (type II, Sigma) and 0.1 mg mL−1 protease (type XIV, Sigma). After 5–10 min digestion, enzymes were washed out with HEPES solution containing 0.05 mmol·L−1 Ca2+ for 5 min. The ventricles were separated and cut into small pieces, which were resuspended under gentle mechanical agitation and stored in HEPES solution containing 0.2 mmol·L−1 Ca2+ at room temperature.

Electrophysiological recordings

A droplet of the cell suspension was placed to a chamber (1 mL) mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon, Diaphot, Japan). Cells were in 1.8 mmol·L−1 Ca2+-containing HEPES-buffer. Membrane potentials and currents were recorded at room temperature by using a patch-clamp amplifier (WPC-100, E.S.F. Electronic, Göttingen, Germany) via a digital-to-analog converter (Digidata 1322, Axon Instruments) controlled by pClamp software. Patch electrodes were made from borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, Fla., USA). For recording of action potential (AP), Ito, IKr and IK1, the pipette was filled with the internal solution containing (mmol·L−1): KCl 130, NaCl 10, Mg-ATP 5, MgCl2 2, EGTA 11, CaCl2 1, HEPES 10; pH was adjusted to 7.2 using KOH. For the measurement of INa and ICa, CsCl (130 mmol·L−1) was used to replace KCl and TEA.Cl (15 mmol·L−1) was added to block potassium currents in addition to adjusting pH 7.2 by CsOH. CsCl (10 mmol·L−1) was always present in bath solution to block IK1. CoCl2 (1 mmol·L−1) or CdCl2 (50 µmol·L−1) was used to block ICa,L. The general access resistance (Ra) was about 2–3 MΩ in most of our experimental condition. The series resistance was electronically compensated by 60–80% to reduce the voltage-clamp error. The voltage-drop error was reduced to be 0.8 ± 0.2 mV in ICa,L measurement. In order to increase the clamp efficiency during measurement of INa, the external concentration of Na+ was lowered to 40 mmol·L−1 using n-methyl-d-glucamine to replace Na+ to decrease the maximum current amplitude of INa within 10 nA and the low resistance electrodes (Ra ≈ 1 MΩ) were used. Therefore, the voltage-drop error was reduced to be 3.7 ± 0.3 mV after electronical compensation. For recording the currents elicited by the AP clamp, the AP contour of rat papillary muscle, which was acquired by intracellular recording in the isolated papillary muscle horizontally fixed one end at bottom and hooked the other end to force transducer in a chamber (1.5 mL) perfused with normal Tyrode solution (37°C, gased with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) at the rate of 10 mL min−1 under isometric condition with a preload of 1 g to concomitantly measure the electrically paced contractile force at 1 Hz by Gould recorder and the APs by puncturing the microelectrode (filled with 3 M KCl, electrode resistance: 30 MΩ) into muscle to record APs by pClamp software via Axon clamp 2B amplifier in bridge mode, was employed as the voltage protocol to record the AP-clamp-elicited currents.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ transients

Isolated rat ventricular cells were loaded with fluo-3 by incubating with 0.5 mmol·L−1 Ca2+-containing HEPES-buffer containing 5 µmol·L−1 fluo-3/AM and Pluronic F-127 (2%) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing out the excess fluo-3/AM, cells were then transferred to 1.8 mmol·L−1 Ca2+-containing HEPES-buffer for another 30 min before beginning the experiments. Cells were electrically stimulated by 2 ms and twice-threshold pulses at 1 Hz. Fluorescent changes were detected and acquired by a Zeiss LSM-510 laser scanning confocal system (Carl Zeiss, MicroImaging GmbH, Germany) in line-scan mode. Fluo-3 was excited with a 488 nm argon laser, and fluorescence emission was measured using a 505–550 nm band-pass filter acquired by image acquisition system. The intracellular Ca2+ transients are reported as F/F0, where F is the fluorescence signal and F0 is the resting fluorescence recorded at the start of the experiment.

Transfection of hERG in HEK293T cells

The cloned hERG-pEGFP-N2 vector was a gift from Dr L.P. Lai's laboratory. Lipofatamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used as the reagent for transient transfection. HEK293T cells (4 × 105) were seeded into a 35 mm dish and grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics at 37°C and 5% CO2 the day before transfection. Onto the cell monolayer were added 2.5 µg plasmid and 5 µL Lipofatamine 2000 in 1 mL Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). The cells were trypsinized for patch clamp 48 h after transfection.

Drugs

Piceatannol and resveratrol were purchased from Sigma Chemicals, and were dissolved in DMSO.

Data analysis and statistics

Dose-response curves were fit by the Hill equation:

| (1) |

where D is the drug concentration, KD is the concentration of drug for half-maximum effect and n is Hill's coefficient.

The voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation curves and activation curves of INa and ICa,L were fitted by the Boltzmann equation:

| (2) |

where Vm is the conditioning potential, V0.5 is the potential of half inactivation, and s is the slope factor.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed paired Student's t-test was taken to indicate statistical significance in data before and after drug treatment at the same preparation. Comparisons among groups were performed by one-way anova with Duncan's new multiple range test. The effective antiarrhythmic concentrations of either resveratrol or piceatannol were determined by Yates' corrected chi-square test (two-sided).

Results

Effect of piceatannol on the APs and inward currents

Figure 1B compares the different potency in APD prolongation between piceatannol and resveratrol at the concentrations of 3–100 µmol·L−1 in rat ventricular cells stimulated at 1 Hz. Piceatannol markedly prolonged APDs in association with the decrease of Vmax of AP in concentration-dependent manner (Table 1). Resveratrol significantly prolonged APDs at the concentration of 100 µmol·L−1 (APD90: 19.9 ± 2.8 ms in control, n= 6; 50.2 ± 6.2 ms in resveratrol 100 µmol·L−1, n= 6; P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Action potential parameters of rat ventricular cells before and after exposure to cumulative increase of three concentrations of piceatannol at 1 Hz stimulation.

| Piceatannol (µmol·L−1) | RMP (mV) | Vmax (v/s) | APD50 (ms) | APD90 (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −80.3 ± 1.0 | 337.5 ± 21.8 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 16.6 ± 1.8 |

| 3 | −80.2 ± 1.4 | 318.5 ± 22.0 | 15.4 ± 4.9 | 27.8 ± 6.5 |

| 10 | −82.3 ± 1.7 | 242.5 ± 31.2* | 53.0 ± 16.5* | 63.7 ± 17.1* |

| 30 | −81.7 ± 1.4 | 161.3 ± 18.8* | 82.6 ± 15.3* | 95.8 ± 14.9* |

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from different 6 cells. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05) as compared between control and drug-treated groups by paired t-test. RMP: resting membrane potential; Vmax: the maximum upstroke velocity of action potential; APD50 and APD90: action potential duration measured at 50 and 90% repolarization.

Figure 1C shows the effect of piceatannol on AP-clamp-elicited inward currents and compares with that of resveratrol under the condition of blocking potassium channels. Piceatannol (10 µmol·L−1) slightly inhibited the initial sodium current in concomitant with the pronounced increase of the late component of inward currents which was blocked by 50 µmol·L−1 tetrodotoxin, but not by calcium channel blocker nifedipine (3 µmol·L−1, data not shown). However, resveratrol only inhibited both components of inward currents at the concentration of 100 µmol·L−1.

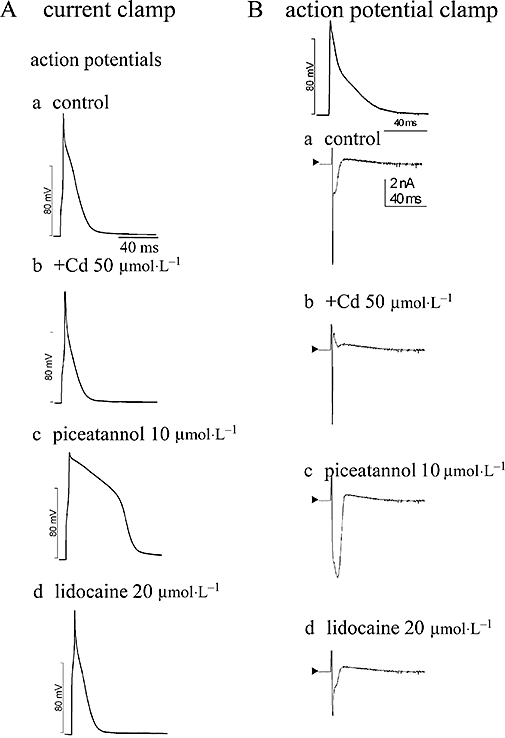

Effects of calcium channel and sodium channel blockers on piceatannol modified APs and inward currents

Ventricular AP (Figure 2A) and the AP-clamp-elicited currents (Figure 2B) were examined at the same cell by alternatively switching between current-clamp and voltage-clamp modes to acquire the respective signals. In the presence of Cd2+ (50 µmol·L−1) to block ICa,L, APDs were shortened (Figure 2A-b) and the outward currents appeared in association with the suppression of inward currents (Figure 2B-b). In the presence of Cd2+, piceatannol also prolonged the APs (Figure 2A-c) and induced an inward current (Figure 2B-c), which was markedly reversed by lidocaine 20 µmol·L−1 (Figure 2A-d,B-d).

Figure 2.

Effects of calcium channel and sodium channel inhibitors in piceatannol-produced modulation in (A) APs recorded in current mode and (B) the AP-clamp-elicited inward currents at the same cell under the conditions of using the normal K+-containing pipette internal and bath solutions. The AP contour of rat papillary muscle stimulated at 1 Hz was employed as the voltage protocol in AP-clamp study. Cd2+ (50 µmol·L−1) was used to block L-type calcium channel, and lidocaine (20 µmol·L−1) to modulate the inactivation state of sodium channel. In the presence of Cd2+, piceatannol can prolong APDs (A-b) associated with increasing inward current (B-b), which can be reversed by lidocaine (A-d and B-d).

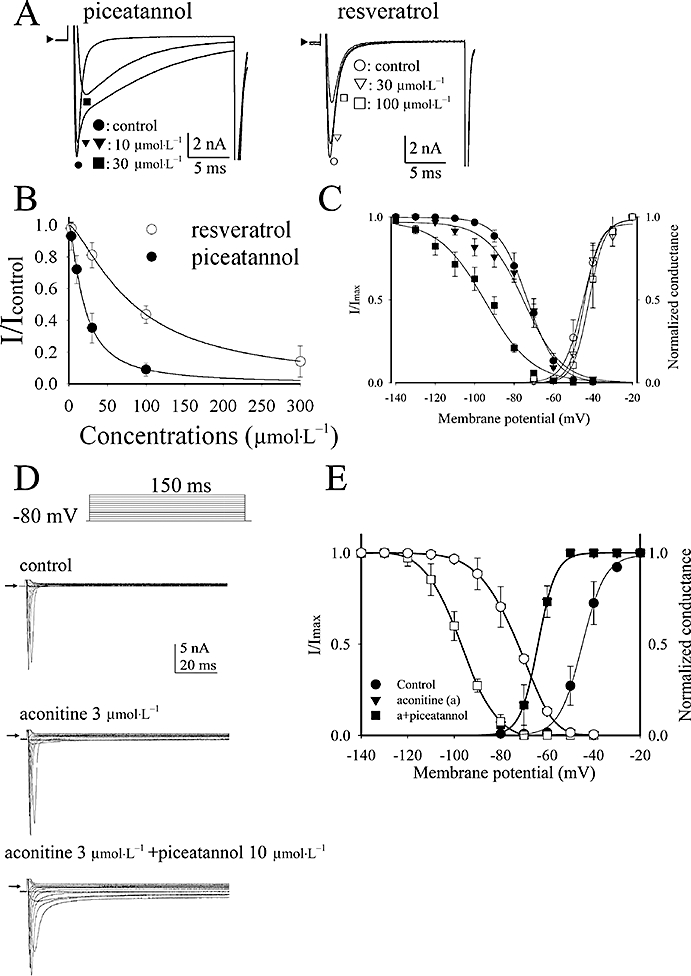

Comparison of the different effect of piceatannol and resveratrol on cardiac sodium channel

Piceatannol dose-dependently inhibited the peak amplitude of INa in association with slowing INa inactivation, rather than produced a persistent component of INa, as shown in the left panel of Figure 3A. The inactivation rate of INa before and after exposure to piceatannol 10 µmol·L−1 was analysed in currents elicited by a long pulse from holding potential −80 mV to 0 mV for 100 ms, and INa,at 0 mV inactivation was fitted with a two exponential equation. The decay constants of fast and slow components of INa,at 0 mV were τfast= 0.8 ± 0.1 ms and τslow= 15.3 ± 0.1 ms in control (n= 4), and were τfast= 0.9 ± 0.1 ms and τslow= 40.1 ± 2.0 ms (P < 0.05 vs. control, n= 4) in the presence of piceatannol 10 µmol·L−1 respectively. The effect of resveratrol on INa was different from that of piceatannol as shown in the right panel of Figure 3A. Resveratrol inhibited INa without altering INa inactivation. The dose-response curves of piceatannol and resveratrol in INa inhibition are plotted in Figure 3B. IC50 and Hill's coefficient of INa inhibition at −30 mV of piceatannol were 19.5 ± 0.4 and 1.4 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6), and those of resveratrol were 83.3 ± 1.3 µmol·L−1 (n= 6, P < 0.05 vs. piceatannol) and 1.4 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) respectively. Figure 3C shows that piceatannol significantly shifted the voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation curve of INa to more negative potential at the concentration of 30 µmol·L−1 without altering the INa activation threshold. The V0.5 and the slope factor (s) of voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation of INa were −73.2 ± 0.4 and −7.5 ± 0.3 mV (n= 6) in control, −74.7 ± 1.6 and −9.6 ± 1.4 mV (n= 6) in piceatannol 10 µmol·L−1, and −94.5 ± 1.7 mV (n= 6, P < 0.05 vs. control) and −11.9 ± 1.4 mV (n= 6) in piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1. The V0.5 and the slope factor (s) of INa activation curves were not significantly altered in the absence and presence of piceatannol [−45.0 ± 0.5 and 4.9 ± 0.4 mV in control (n= 6), −44.4 ± 0.8 and 3.8 ± 0.6 mV in piceatannol 10 µmol·L−1 (n= 6), and −42.0 ± 0.5 and 4.0 ± 0.4 mV in piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1 (n= 6)].

Figure 3.

(A) Comparison of the different effect of piceatannol and resveratrol in rat cardiac sodium current elicited by a 20 ms step pulse form holding potential −80 mV to −10 mV. (B) The dose-response curves of INa inhibition by piceatannol and resveratrol. The curves are fitted with Hill equation (1). (C) The voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation and activation curves of sodium channel before and after exposure to piceatannol are plotted and the respective curves are fitted with Boltzman equations (2). Data are shown in mean ± SEM (n= 6). (D) Effect of piceatannol in aconitine-modulated sodium current. For measurement of the activation curves of INa, the membrane potential was held on −80 mV, and sodium currents were elicited by a family of depolarizing pulses for 150 ms from −70 mV stepped to +40 mV by 10 mV every step once per 5 s. The typical sodium current traces in response to aconitine (3 µmol·L−1) in the absence and presence of piceatannol (10 µmol·L−1). The arrowheads indicate the current level at zero. (E) For measurement of the steady-state inactivation curves of INa, INa was elicited by stepping to 0 mV for 20 ms from different holding potentials ranging from −140 mV to −40 mV increased by 10 mV every 10 s. The steady-state inactivation and activation curves of sodium channel in the conditions of control, aconitine (A) 3 µmol·L−1, and aconitine plus piceatannol 10 µmol·L−1. The curves are fitted with Boltzman equations (2).

Effect of piceatannol on aconitine-modulated sodium current

Aconitine could activate a persistent INa which resulted in an inward shift of holding membrane current (Figure 3D). The activation of a persistent INa was associated with a negative shift of the voltage-dependent activation curve from V0.5=−45.0 ± 0.5 mV (n= 6) in control to V0.5=−63.9 ± 0.4 mV (n= 6) in the presence of 3 µmol·L−1 aconitine (Figure 3E). The slope factor of INa activation curve was s= 4.9 ± 0.4 (n= 6) in control and s= 3.8 ± 0.3 in the presence of 3 µmol·L−1 aconitine. V0.5 and the slope factor of voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation curve of INa was unaffected by 3 µmol·L−1 aconitine (control: V0.5=−73.2 ± 0.4 mV, s= 7.5 ± 0.3, n= 6; aconitine 3 µmol·L−1: V0.5=−73.1 ± 0.4 mV, s= 7.4 ± 0.3, n= 6). Addition of piceatannol (10 µmol·L−1) to aconitine-treated cells inhibited the amplitude of INa but increased the slowing inactivation component of INa as shown in the right panel of Figure 3D. INa activation curve of aconitine-treated cells was not altered by further addition of piceatannol (V0.5=−63.9 ± 0.4 mV, s= 3.8 ± 0.3, n= 6), but V0.5 of voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation of INa was shifted to −97.2 ± 0.2 mV (P < 0.05 vs. aconitine 3 µmol·L−1, n= 6). S value remained at 7.1 ± 0.2 (n= 6).

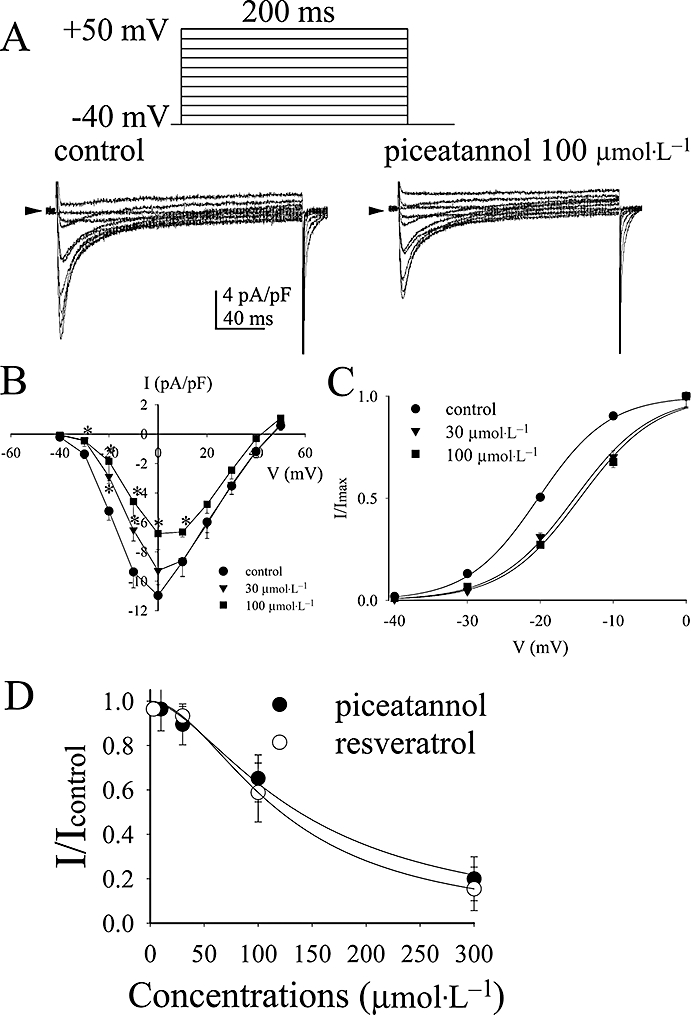

Effect of piceatannol and resveratrol on L-type calcium current

Piceatannol inhibited ICa,L at the concentrations of 30 µmol·L−1 (Figure 4A,B) in association with the right shift of ICa,L activation curve (Figure 4C). The parameters of ICa,L activation curves were V0.5=−20.3 ± 0.2 mV and s= 4.8 ± 0.2 (n= 6) in control, V0.5=−15.3 ± 0.7 mV (P < 0.05 vs. control, n= 6) and s= 5.3 ± 0.6 (n= 6) in piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1, and V0.5=−14.6 ± 0.7 mV (P < 0.05 vs. control, n= 6) and s= 5.3 ± 0.6 (n= 6) in piceatannol 100 µmol·L−1. Figure 4D compares the dose-dependent inhibition of ICa,L at 0 mV by piceatannol and resveratrol. The IC50 and Hill's coefficient of piceatannol were 137.9 ± 9.4 and 1.7 ± 0.2 µmol·L−1 (n= 6), and those of resveratrol were 121.1 ± 5.6 and 1.9 ± 0.2 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) respectively. There was no significant difference in the IC50 values between piceatannol and resveratrol.

Figure 4.

(A) Effect of piceatannol on L-type calcium current of rat ventricular cells. The typical current traces of a family of depolarizing pulses from the holding potential −40 mV to +50 mV by 10 mV every step for 200 ms in the absence and presence of piceatannol 100 µmol·L−1. (B) The I-V curves and (C) the activation curves of L-type calcium channel in response to piceatannol at the concentrations of 30 µmol·L−1 and 100 µmol·L−1. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n= 6). *P < 0.05 (n= 6) versus control group by paired t-test. (D) Comparison of the dose-dependent inhibition of ICa,L at 0 mV by piceatannol and resveratrol. The curves are fitted with Hill equation (1).

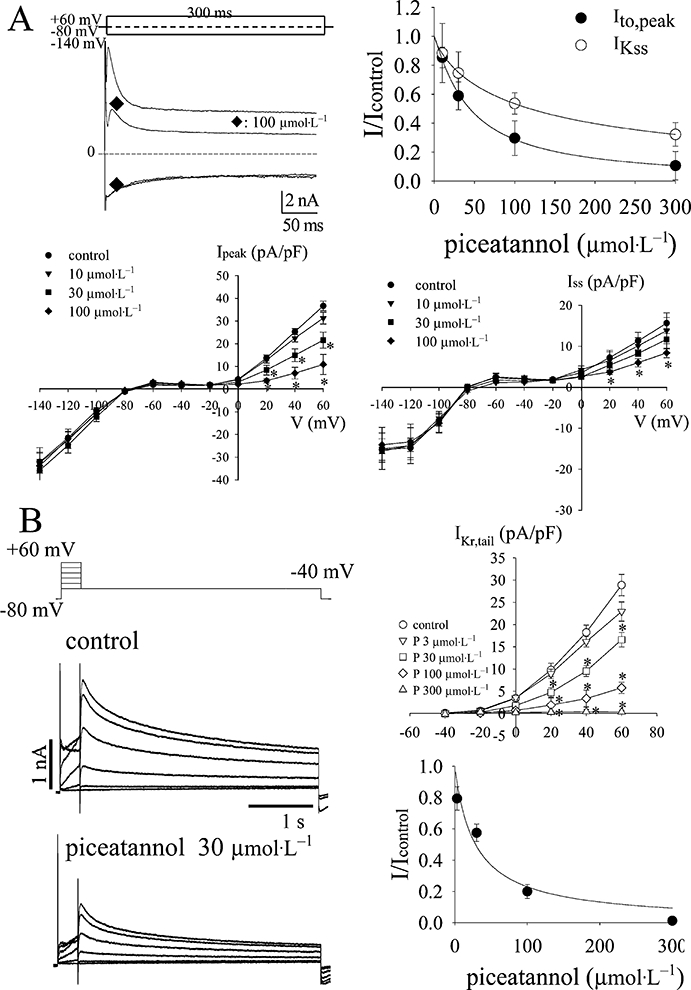

Effect of piceatannol on potassium channels

Figure 5A shows that piceatannol inhibited transient outward current (Ito) and the slow inactivation component of the outward currents (IKss) in rat ventricular cells at the concentrations of 30 µmol·L−1. IK1 was not significantly altered by piceatannol even at the concentration of 100 µmol·L−1. The I-V curves of either peak Ito (Ipeak) or IKss at 300 ms (Iss) in response to the cumulative concentrations of piceatannol were plotted in the lower panel of Figure 5A, and the concentration-dependent inhibition curves in the upper right panel of Figure 5A. IC50 and Hill's coefficient of piceatannol were 44.1 ± 2.0 and 1.1 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) in peak Ito inhibition and 118.7 ± 3.2 and 0.8 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) in IKss inhibition, and those of resveratrol were 79.1 ± 0.1 and 1.2 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) in peak Ito inhibition and 167.9 ± 0.1 and 0.9 ± 0.1 µmol·L−1 (n= 6) in IKss inhibition.

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of piceatannol on potassium channels of rat ventricular cells. Co2+ (1 mmol·L−1) was always present in the bath to block ICa,L. The left top shows the typical current traces of transient outward currents (Ito) followed by a sustained outward currents and the inwardly rectifying potassium current (IK1) in the absence and presence of piceatannol at 100 µmol·L−1. The membrane potential was held at −80 mV, and was either depolarized to +60 mV to activate the transient outward currents or hyperpolarized to −140 mV to elicit IK1 for 300 ms. The lower panael of (A) shows the I-V curves of the current density at peak (Ipeak) and at the end of 300 ms (Iss) in the absence and presence of piceatannol at the concentrations of 10, 30 and 100 µmol·L−1. The outward currents were elicited by a family of depolarization steps from −60 mV to +60 mV increased by 10 mV every step, and a 20 ms depolarization pre-pulse was preceded to eliminate the contamination of sodium current. Data are shown in mean ± SEM (n= 6), and the asterisks indicate the statistical significance between the currents of control and drug-treated groups elicited at the same voltage level by one-way anova with Duncan's new multiple range test. The right top shows the dose-dependent inhibition of Ipeak and Iss by piceatannol. The curves are fitted by the Hill equation (1). (B) Effect of piceatannol on IKr in HEK293T cells transfected with hERG encoding the alpha-subunit of IKr. IKr was elicited by a family of depolarization steps increased every 20 mV for 300 ms from holding potential at −80 mV, and followed by the repolarization at −40 mV to record the tail currents. The right top of (B) plots the I-V curves constructed by the peak amplitude of the tail currents elicited at the respective depolarization steps. Data are shown in mean ± SEM (n= 6), and the asterisks indicate the statistical significance between the currents of control and drug-treated groups elicited at the same voltage level by one-way anova with Duncan's new multiple range test. The right bottom of (B) shows the dose-dependent inhibition of IKr,tail elicited at +60 mV by piceatannol. The curve is fitted with the Hill equation (1).

The effect of piceatannol on IKr was examined in HEK293T cells transfected with human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) encoding the alpha-subunit of IKr. The typical current traces and the concentration-response curve of IKr inhibition by piceatannol was plotted in Figure 5B. IC50 and Hill's coefficient were 28.6 ± 1.1 and 1.0 ± 0.3 µmol·L−1 (n= 6).

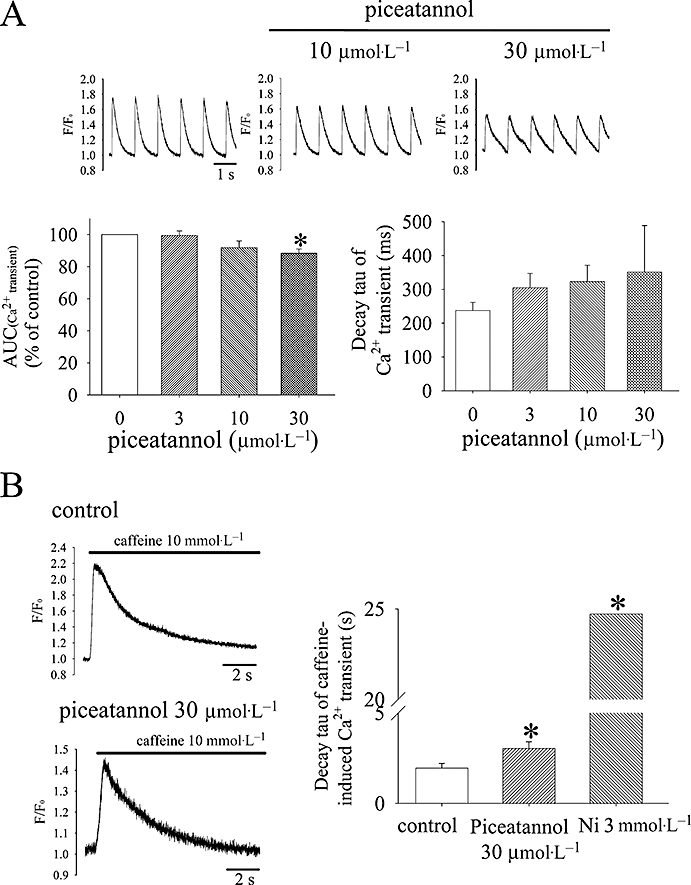

Effect of piceatannol on electrical paced and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients

The upper panel of Figure 6A shows the typical intracellular Ca2+ transients of ventricular cell paced at 1 Hz by field stimulation before and after applying piceatannol at the concentrations of 10 and 30 µmol·L−1. From analysis of the averaged area under Ca2+ transients from consecutive five beatings in the steady-state condition of control or 5 min after exposure to piceatannol, the total cytosolic Ca2+ presented during every beating was significantly decreased by piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1 (the lower left panel of Figure 6A). The decay rate of intracellular Ca2+ transients was slowed by 22.5 ± 3.2% and 58.0 ± 11.4% in the presence of piceatannol 10 and 30 µmol·L−1 respectively (the right lower panel of Figure 6A). The effect of piceatannol on Na+-Ca2+ exchanger was examined in resting cells applying caffeine (10 mmol·L−1) to release intracellular Ca2+ from SR as shown in Figure 6B. Ni2+ (3 mmol·L−1), a Na+-Ca2+ exchanger inhibitor, markedly retarded the decline rate of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient, which indicates Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is a major contributor to diminish the elevated cytosolic Ca2+. Piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1 also slowed the decline rate of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient.

Figure 6.

(A) Effect of piceatannol in the intracellular Ca2+ transients of electrical paced rat ventricular cells and the decay rate of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients. The area under Ca2+ transient (AUC) was integrated and averaged from consecutive five beatings in the steady-state condition of control or after applying piceatannol for 5 min from 10 different cells. The decay rate of Ca2+ transient was analysed by simple one-exponential equation (n= 10) as shown in the right bottom of (A). (B) Caffeine 10 mmol·L−1 was applied to elicit intracellular Ca2+ release in quiet cells which previously had electric pacing to a steady state in the absence and presence of piceatannol as shown in the left panel of (B). The decay rate of caffeine-released intracellular Ca2+ was also analysed by simple one-exponential equation. NiCl2 (3 mmol·L−1) was used to block Na+-Ca2+ exchange which markedly prolonged the decay time of caffeine-elicited Ca2+ transient as shown the measured decay tau in the right panel of (B). Piceatannol 30 µmol·L−1 significantly slowed the decay rate. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n= 6). *P < 0.05 versus control group by one-way anova with Duncan's new multiple range test.

Comparison of the antiarrhythmic efficacy of piceatannol and resveratrol in ischaemia-reperfused rat hearts

Table 2 shows that reperfusion-induced PVT occurred in all animals of vehicle (DMSO 0.1%) group after 20 min LAD occlusion, and either piceatannol or resveratrol could convert reperfusion-induced PVT to normal sinus rhythm in concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, PVT was completely abolished by 10 µmol·L−1 of piceatannol. The antiarrhythmic IC50 and Hill's coefficient of piceatannol were 3.1 ± 0.1 and 2.1 ± 1.1 µmol·L−1, and those of resveratrol were 33.7 ± 8.6 and 0.8 ± 0.2 µmol·L−1. The antiarrhythmic efficacy of piceatannol was more potent than that of resveratrol.

Table 2.

Comparison of antiarrhythmic efficacy between piceatannol and resveratrol in isolated Langendorff-perfused rat hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion

| PVT | Converted to normal rhythm | |

|---|---|---|

| Piceatannol (µmol·L−1) | ||

| 0 | 13 | 0 |

| 1 | 13 | 0 |

| 3 | 9 | 4 |

| 10†‡ | 0 | 13 |

| Resveratrol (µmol·L−1) | ||

| 0 | 14 | 0 |

| 3 | 13 | 1 |

| 10* | 9 | 5 |

| 30* | 8 | 6 |

| 100*‡ | 4 | 10 |

PVT: polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Piceatannol or resveratrol was administered 5 min after reperfusion-induced arrhythmia. Data are the animal number of the arrhythmia without treatment or the successful case number which was converted to regular rhythm 1h after exposure to piceatannol or resveratrol at the different concentrations. The total animal number at every concentration of the respective treatment was 13 in piceatannol-treated group and was 14 in resveratrol-treated group. The symbols on the right side of the treated groups indicate the significant differences among the treatments in the number of both PVT and converted to normal rhythm.

P < 0.01 drug-treated group vs vehicle (DMSO 0.1%)

P < 0.05 drug-treated group vs vehicle (DMSO 0.1%), and

P < 0.05 3 µmol·L−1 vs other concentrations by Yates’ corrected Chi-square test.

Discussion and conclusions

Polyphenolic antioxidants of red wine, including resveratrol and piceatannol, are thought to be responsible for the cardiovascular benefits associated with moderate wine consumption (Das et al., 1999). Piceatannol possesses an additional hydroxyl group in the 3′ position of resveratrol, which makes piceatannol exerting the unique action to moderately slow INa inactivation, rather than to induce a persistent non-inactivation INa, in association with the decrease of peak INa at the concentration of 3 µmol·L−1. The potency of cardiac ion channel modulation by piceatannol is in the order of INa > IKr > Ito > IKss > ICa,L. At the antiarrhythmic concentrations within 10 µmol·L−1, piceatannol could moderately prolong APD via slowing INa inactivation to increase the effective refractory period in association with the decrease of Vmax of AP via decreasing INa to stabilize the membrane excitability, which may contribute to the ionic mechanisms of antiarrhythmic actions in ischaemic-reperfused rat hearts. Furthermore, piceatannol is more potent than resveratrol in cardiac ion channel inhibition, including INa, Ito and IKss, in parallel with the antiarrhythmic activity. Our present study provides the electrophysiological evidence to support the findings of better antiarrhythmic activity of piceatannol than resveratrol in ischaemia-reperfused rat hearts.

Piceatannol moderately slowed INa inactivation, which could be reverted by lidocaine. The result indicates that piceatannol may fix Na+ channel in a state of inactivation which shunts rapidly between inactivation state and open state. Lidocaine may modify piceatannol-modulated sodium channel into another inactivation state that could not shunt rapidly between inactivation and open state. Besides that, the modulation of piceatannol on INa was different from that of aconitine. Aconitine shifted the sodium channel activation threshold to negative potentials and thus produced a persistent INa at resting membrane potential of cardiomyocytes to induce arrhythmia. Aconitine can bind inside the pore of Na+ channel to cause easier and longer opening of Na+ channel (Tikhonov and Zhorov, 2005). Piceatannol did not reverse aconitine-activated Na+ channel, and produced an additive effect in increasing the slow inactivation component of INa; nevertheless, piceatannol could decrease the window of INa by left shifting the voltage-dependent inactivation curves of aconitine-modified INa. It indicates that the action model of piceatannol in Na+ channel is far from that of aconitine. Furthermore, piceatannol did not increase intracellular Ca2+ transients and could inhibit the forward mode of Na+-Ca2+ exchanger to decrease triggered activity, which was different from other Na+ channel modulators, such as DPI201-106 and BDF 9198 (Gwathmey et al., 1988; Yuill et al., 2000), which could enhance proarrhythmia.

Resveratrol and piceatannol have been detected in red wine and have long been associated with the cardioprotection of the ‘French paradox’ (Renaud and de Lorgeril, 1992; Hung et al., 2000; 2001). The pharmacokinetics of piceatannol appears to be qualitatively similar to resveratrol in the rat, which is absorbed quickly, distributed widely in heart, liver and kidney tissues, and is eliminated quickly with a plasma elimination half-life of 30 min (Marier et al., 2002; Roupe et al., 2004; 2006a,b; Abd El-Mohsen et al., 2006). Though the plasma concentrations of oral piceatannol in humans remain to be established, the blood levels of resveratrol could achieve 2.4 µmol·L−1 in a phase I study of oral resveratrol 5 g in healthy volunteers (Boocock et al., 2007). Besides that, piceatannol can be a metabolite of resveratrol via the cytochrome P450 1A2 and 1B1 enzymes (Potter et al., 2002; Piver et al., 2004), which have led investigators to postulate that resveratrol may act as a pro-drug for the production of piceatannol. The present study offers important information that piceatannol at the concentration of 3 µmol·L−1 can modulate INa and produces antiarrhythmic effect in ischaemia-reperfused rat hearts. Furthermore, piceatannol is more potent than resveratrol in the inhibition of ion channels, including INa, Ito and IKss, which is in parallel with the more potent antiarrhythmic efficacy of piceatannol than that of resveratrol. Because the decay time constant of piceatannol-modified INa at 0 mV was about 40 ms which is less than normal human ventricular APDs, piceatannol may not influence the normal AP and do not have the risk to induce long QT at the concentrations less than 10 µmol·L−1. Therefore, piceatannol is safe for healthy human as present in daily food or drink. However, piceatannol at the higher concentrations (more than 30 µmol·L−1) can markedly inhibit IKr and INa. Blocking IKr can cause long QT syndrome and induce Torsades de pointes. The excessive inhibition of INa can interfere with cardiac conduction and cause Brugada-like syndrome. Hence, it is not recommended taking high doses of piceatannol as daily supplement.

In conclusion, piceatannol was more potent than resveratrol in cardiac ion channel inhibition which was also in parallel with its potent antiarrhythmic efficacy in ischaemia-reperfused rat hearts. Piceatannol-mediated modulation on cardiac sodium channel may contribute to its antiarrhythmic action at concentrations less than 10 µmol·L−1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC 95-2323-B-002-013) and Ministry of Economic Affairs (93-EC-17-A-20-S1), Taiwan.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AP

action potential

- APDs

action potential durations

- ICa,L

L-type Ca2+ current

- IK1

inward rectifier K+ current

- IKss

steady-state outward K+ current

- INa

Na+ current

- Ito

transient outward K+ current

- Vmax

maximal upstroke velocity of action potential

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abd El-Mohsen M, Bayele H, Kuhnle G, Gibson G, Debnam E, Kaila Srai S, et al. Distribution of [3H]trans-resveratrol in rat tissues following oral administration. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(1):62–70. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abtahian F, Guerriero A, Sebzda E, Lu MM, Zhou R, Mocsai A, et al. Regulation of blood and lymphatic vascular separation by signaling proteins SLP-76 and Syk. Science. 2003;299(5604):247–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1079477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Sethi G, Ahn KS, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Kunnumakkara AB, et al. Targeting signal-transducer-and-activator-of- transcription-3 for prevention and therapy of cancer: modern target but ancient solution. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1091:151–169. doi: 10.1196/annals.1378.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier M, Hearse DJ, Manning AS. Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias and oxygen-derived free radicals. Studies with ‘anti-free radical’ interventions and a free radical-generating system in the isolated perfused rat heart. Circ Res. 1986;58(3):331–340. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boocock DJ, Faust GE, Patel KR, Schinas AM, Brown VA, Ducharme MP, et al. Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(6):1246–1252. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WP, Su MJ, Hung LM. In vitro electrophysiological mechanisms for antiarrhythmic efficacy of resveratrol, a red wine antioxidant. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;554(2–3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L, Longnecker R. Inhibition of host kinase activity altered by the LMP2A signalosome-a therapeutic target for Epstein-Barr virus latency and associated disease. Antiviral Res. 2002;56(3):219–231. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das DK, Sato M, Ray PS, Maulik G, Engelman RM, Bertelli AA, et al. Cardioprotection of red wine: role of polyphenolic antioxidants. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1999;25(2–3):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauconneau B, Waffo-Teguo P, Huguet F, Barrier L, Decendit A, Merillon JM. Comparative study of radical scavenger and antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds from Vitis vinifera cell cultures using in vitro tests. Life Sci. 1997;61(21):2103–2110. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrigni NR, McLaughlin JL, Powell RG, Smith CR., Jr Use of potato disc and brine shrimp bioassays to detect activity and isolate piceatannol as the antileukemic principle from the seeds of Euphorbia lagascae. J Nat Prod. 1984;47(2):347–352. doi: 10.1021/np50032a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwathmey JK, Slawsky MT, Briggs GM, Morgan JP. Role of intracellular sodium in the regulation of intracellular calcium and contractility. Effects of DPI 201-106 on excitation-contraction coupling in human ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1988;82(5):1592–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI113771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Dietary polyphenols: good, bad, or indifferent for your health? Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73(2):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung LM, Chen JK, Huang SS, Lee RS, Su MJ. Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47(3):549–555. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung LM, Chen JK, Lee RS, Liang HC, Su MJ. Beneficial effects of astringinin, a resveratrol analogue, on the ischemia and reperfusion damage in rat heart. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(8):877–883. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamori Y, Kato Y, Kubo M, Yasuda M, Baba K, Kozawa M. Physiological activities of 3,3′,4,5′-tetrahydroxystilbene isolated from the heartwood of Cassia garrettiana CRAIB. Chem Pharm Bull. 1984;32(1):213–218. doi: 10.1248/cpb.32.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EM, Roti Roti EC, Wang J, Delfosse SA, Robertson GA. Cardiac IKr channels minimally comprise hERG 1a and 1b subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):44690–44694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AS, Coltart DJ, Hearse DJ. Ischemia and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in the rat. Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibition with allopurinol. Circ Res. 1984;55(4):545–548. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marier JF, Vachon P, Gritsas A, Zhang J, Moreau JP, Ducharme MP. Metabolism and disposition of resveratrol in rats: extent of absorption, glucuronidation, and enterohepatic recirculation evidenced by a linked-rat model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(1):369–373. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JM, Burg DL, Wilson BS, McLaughlin JL, Geahlen RL. Inhibition of mast cell Fc epsilon R1-mediated signaling and effector function by the Syk-selective inhibitor, piceatannol. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(47):29697–29703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JD, Furlong MT, Asai DJ, Harrison ML, Geahlen RL. Syk, activated by cross-linking the B-cell antigen receptor, localizes to the cytosol where it interacts with and phosphorylates alpha-tubulin on tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(9):4755–4762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piver B, Fer M, Vitrac X, Merillon JM, Dreano Y, Berthou F, et al. Involvement of cytochrome P450 1A2 in the biotransformation of trans-resveratrol in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(4):773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GA, Patterson LH, Wanogho E, Perry PJ, Butler PC, Ijaz T, et al. The cancer preventative agent resveratrol is converted to the anticancer agent piceatannol by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1B1. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(5):774–778. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud S, de Lorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1992;339(8808):1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roupe K, Teng XW, Fu X, Meadows GG, Davies NM. Determination of piceatannol in rat serum and liver microsomes: pharmacokinetics and phase I and II biotransformation. Biomed Chromatogr. 2004;18(8):486–491. doi: 10.1002/bmc.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roupe KA, Remsberg CM, Yanez JA, Davies NM. Pharmacometrics of stilbenes: seguing towards the clinic. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2006a;1(1):81–101. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roupe KA, Yanez JA, Teng XW, Davies NM. Pharmacokinetics of selected stilbenes: rhapontigenin, piceatannol and pinosylvin in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006b;58(11):1443–1450. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.11.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sada K, Takano T, Yanagi S, Yamamura H. Structure and function of Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J Biochem. 2001;130(2):177–186. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov DB, Zhorov BS. Sodium channel activators: model of binding inside the pore and a possible mechanism of action. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(20):4207–4212. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waffo Teguo P, Fauconneau B, Deffieux G, Huguet F, Vercauteren J, Merillon JM. Isolation, identification, and antioxidant activity of three stilbene glucosides newly extracted from vitis vinifera cell cultures. J Nat Prod. 1998;61(5):655–657. doi: 10.1021/np9704819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wymore RS, Gintant GA, Wymore RT, Dixon JE, McKinnon D, Cohen IS. Tissue and species distribution of mRNA for the IKr-like K+ channel, erg. Circ Res. 1997;80(2):261–268. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi S, Inatome R, Takano T, Yamamura H. Syk expression and novel function in a wide variety of tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288(3):495–498. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuill KH, Convery MK, Dooley PC, Doggrell SA, Hancox JC. Effects of BDF 9198 on action potentials and ionic currents from guinea-pig isolated ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130(8):1753–1766. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]