Abstract

Background and purpose:

Migraine is a disabling neurological disorder involving activation, or the perception of activation, of trigeminovascular afferents containing calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Released CGRP from peripheral trigeminal afferents causes dilatation of dural blood vessel, and this is used to measure trigeminal nerve activation. Kainate receptors with the GluR5 subunit (iGluR5, ionotropic glutamate receptor) are present in the trigeminal ganglion and may be involved in nociception. We investigated the possible involvement of prejunctional iGluR5 kainate receptors on CGRP release from trigeminal afferents.

Experimental approach:

We used neurogenic dural vasodilatation, which involves reproducible vasodilatation in response to CGRP release after electrical stimulation of the dura mater surrounding the middle meningeal artery. The effects of the specific iGluR5 receptor antagonist UBP 302 and agonist (S)-(-)-5-iodowillardiine were investigated on neurogenic and CGRP-induced dural vasodilatation in rats, by using intravital microscopy.

Key results:

Administration of 10 and 20 mg·kg−1 of iodowillardiine inhibited electrically induced dural vessel dilatation, an effect blocked by pretreatment with 50 mg·kg−1 UBP 302. Administration of the iGluR5 receptor antagonist UBP 302 alone had no significant effect. CGRP (1 mg·kg−1)-induced dural vasodilatation was not inhibited by the iGluR5 receptor agonist iodowillardiine.

Conclusions and implications:

This study demonstrates that activation of the iGluR5 kainate receptors with the selective agonist iodowillardiine is able to inhibit neurogenic dural vasodilatation probably by inhibition of prejunctional release of CGRP from trigeminal afferents. Taken together with recent clinical studies the data reinforce CGRP mechanisms in primary headaches and demonstrate a novel role for kainate receptor modulation of trigeminovascular activation.

Keywords: neurogenic dural vasodilatation, calcitonin gene-related peptide, kainate receptors

Introduction

Migraine is a common, disabling neurological disorder that affects about 15% of the population (Steiner et al., 2003; Lipton et al., 2007). Migraine is a brain disorder (Goadsby et al., 2002) that involves a combination of head pain with other disturbances of sensation, such as sensitivity to light and sound (Headache Classification Committee of The International Headache Society, 2004). A key manifestation of the disorder is activation, or the perception of activation, of trigeminal afferents mainly in the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, which innervate the pain-producing intracranial structures, such as the dura mater (Goadsby, 2005). Stimulation of the dura mater in humans is known to produce headache-like pain referred to areas innervated by the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (Wolff, 1948). The development of intravital microscopy permitted the direct study of the peripheral branch of the trigeminovascular system by means of neurogenic dural vasodilatation (NDV), and this is now established as a model with proven ability to predict anti-migraine therapeutic potential (Shepheard et al., 1997; Williamson et al., 1997b; 2001; Akerman et al., 2002b; Akerman & Goadsby, 2005b; Bergerot et al., 2006). NDV is substantially due to the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from prejunctional trigeminal nerve fibres innervating the dural blood vessels (Kurosawa et al., 1995; Williamson et al., 1997a; Akerman et al., 2002a,b), while substance P is not implicated in the development of the reproducible neurogenic vasodilatation (Williamson et al., 1997a), nor is it implicated in migraine (May and Goadsby, 2001). Thus the measurement of dural vessel dilatation due to electrical stimulation-evoked release of CGRP is an established method of characterizing trigeminovascular activation (Bergerot et al., 2006). Moreover, because CGRP receptor antagonists are clearly effective in acute migraine (Olesen et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2008), the pharmacology of the control mechanisms for dural CGRP release are of direct relevance to the development of newer migraine therapies and to advancing understanding of the potential pharmacology of migraine.

A potential target for anti-migraine drugs is the family of glutamate receptors (GluRs), which consist of the ionotropic (iGluRs): N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate (AMPA), kainate and the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) 1–8. To date there is evidence that some GluRs are involved in trigeminovascular nociceptive processing. NMDA receptor channel blockers have been shown to reduce nociceptive trigeminovascular transmission in vivo (Mitsikostas et al., 1998; Storer and Goadsby, 1999; Classey et al., 2001; Knyihar-Csillik et al., 2007; Peeters et al., 2007). The AMPA/kainate antagonists 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) and 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzoquinoxaline-7-sulphonamide reduced c-fos expression after activation of structures involved in nociceptive pathways (Mitsikostas et al., 1999), and direct application of CNQX in the trigeminocervical complex attenuated neurons with nociceptive trigeminovascular inputs (Andreou et al., 2006). Regarding the group III mGluR receptor the agonist L-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid decreased c-fos expression in an animal model of trigeminovascular nociceptive processing (Mitsikostas et al., 1999). It is also notable that the group I mGluR5 modulator ADX10059 (Porter et al., 2005) has been reported to be effective in the acute treatment of migraine (Goadsby and Keywood, 2009).

A variety of studies have indicated the involvement of kainate receptors in nociception (Simmons et al., 1998; Ruscheweyh and Sandkuhler, 2002; Turner et al., 2003; Palecek et al., 2004; Ko et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2006), and new data are emerging suggesting a role of kainate receptors in trigeminovascular nociception. Kainate receptors are constituted by the ‘low affinity’ iGluR5, iGluR6, iGluR7 and the ‘high affinity’ KA1 and KA2 subunits, which form different homomeric or heteromeric assemblies, giving rise to functional receptors. The presence of iGluR5 subunits in the trigeminal ganglion neurons (Sahara et al., 1997) and at the presynaptic sites of primary afferents (Hwang et al., 2001; Lucifora et al., 2006) indicates a possible role of kainate receptors in trigeminovascular physiology. Evidence from immunocytochemical studies also exists for peripheral transport of kainate receptors on sensory, both myelinated and unmyelinated axons (Carlton et al., 1995; Coggeshall and Carlton, 1998), suggesting its possible presence on the prejunctional site of the trigeminal peripheral branch. It has been shown that activation of these receptors on peripheral axons leads to increased activity along the sensory root and thus to peripheral nociceptive transduction (Agrawal and Evans, 1986; Ault and Hildebrand, 1993).

Direct evidence linking kainate receptors with migraine, has been demonstrated from studies with the competitive iGluR5-selective receptor antagonists (3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-(2S)-2-carboxy-4,4-difluoro-1-pyrrolidinyl]-methyl]decahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxylic acid) (LY466195) and ethyl(3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-(4-ethoxycarbonylimidazol-1-ylmethyl) decahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic ester, which showed anti-nociceptive effects in animal models of trigeminal activation (Filla et al., 2002; Weiss et al., 2006). In a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study in acute migraine, LY466195 was effective at the 2 h pain-free endpoint (Johnson et al., 2008). In a separate small study of acute migraine, intravenous application of the decahydroisoquinoline AMPA/iGluR5 antagonist LY293558 improved headache pain in two-thirds of migraineurs and relieved the associated symptoms of the attack (Sang et al., 2004). However, due to an AMPA-mediated component of action with LY293558, it is unclear if the observed effects are due to a kainate receptor action or due to a combined AMPA/kainate effect.

In the present study we investigated the possible involvement of prejunctional iGluR5 kainate receptors in a model employing NDV using the selective iGluR5 receptor agonist iodowillardiine (Swanson et al., 1998) and the selective antagonist UBP 302 [(S)-1-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione] (More et al., 2004). NDV provides a good measure of trigeminovascular activation by monitoring dural vascular responses to electrical stimulation (Williamson et al., 1997a). As iGluR5 subunits are located on trigeminal nerve endings (Sahara et al., 1997), the demonstration of an effect would provide further evidence of a potential opportunity to develop new therapies aimed at this target. The results provide new insights into the physiological and pharmacological significance of kainate receptors on CGRP mechanisms in primary headaches. The data were first presented at the thirteenth International Headache Congress (Stockholm, June 2007, Andreou et al., 2007a)

Methods

Surgical preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (280–370 g; n= 37) were anaesthetized throughout the experiments with pentobarbital sodium salt, 60 mg·kg−1 i.p., and then 25 mg·kg−1·h−1 by intravenous infusion. The left femoral artery was cannulated for blood pressure recording and femoral veins for both anaesthetic and test compound administration. A tracheotomy was performed for ventilation. Temperature was maintained throughout by using a homoeothermic blanket system. Animals were positioned on a rat stereotaxic frame and ventilated with oxygen-enriched air, 2–2.5 mL, 80–100 strokes · min−1 by using a small rodent ventilator. After the skull had been exposed, drilling of the right or left parietal bone was performed with a saline-cooled drill, until the blood vessels of the dura mater were clearly visible through the intact thinned skull. Throughout the experiments, the end-tidal CO2 was monitored and kept within normal physiological limits, and blood pressure was scrutinized continually, and the absence of gross fluctuations was used as a measure of suitable anaesthesia. Both measurements were displayed on an online data analysis system (CED spike2v5 software). All experiments were conducted under the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) or under protocols approved by the University of California, San Francisco, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intravital microscopy

The cranial window was covered with mineral oil pre-warmed at 37°C, and a branch of the middle meningeal artery was viewed by using an intravital microscope, with the image displayed on a television screen. The vessel diameter was constantly measured by using a video dimension analyser and displayed on an online data analysis system (CED spike2v5 software).

Experimental protocols

Defining electrical stimulation parameters

Stimulating parameters in the animals were as previously described (Akerman et al., 2002b; Holland et al., 2005). In brief, a bipolar stimulating electrode was positioned on the surface of the cranial window at approximately 200 µm from the vessel of interest. The cranial window was stimulated at 5 Hz, 1 ms for 10 s by using a Grass stimulator S88, with a voltage varying between 35–40 V (50–150 µA) until maximal dilatation was observed. Subsequent electrically induced dilatations in the same animal were then evoked by using that voltage (Akerman et al., 2002b; Holland et al., 2005). The reproducibility of this vasodilator response to electrical stimulation has been demonstrated previously by using consecutive saline-controlled stimuli (Akerman et al., 2002b).

Effect of iGluR5 receptor agonist iodowillardiine on evoked dural vessel dilatation

Two control responses to dural electrical stimulation were performed, and at least 10 min later, iodowillardiine, at doses of 5 (n= 6), 10 (n= 6) and 20 (n= 6) mg·kg−1, was administered intravenously. Electrical stimulation was then repeated at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after drug administration. For those doses at which no full recovery was observed after 90 min of iodowillardiine treatment, CGRP (1 µg·kg−1) was administered intravenously at least 10 min after the 90 min response to dural electrical stimulation. In the experiments where the antagonist UBP 302 was co-administrated with iodowillardiine (n= 6), two control responses to dural electrical stimulation were performed and at least 10 min later 50 mg·kg−1 was administered intravenously, following by iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1, i.v.), 5 min later. Electrical stimulation was then repeated at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after iodowillardiine administration.

Effect of UBP 302 on evoked dural vessel dilatation

Two control responses to dural electrical stimulation were performed, and at least 10 min later, UBP 302, at a dose of 50 mg·kg−1 (n= 5) was administered intravenously. Electrical stimulation was then repeated at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after drug administration.

Effect of iodowillardiine on CGRP-evoked dural vessel dilatation

Two control responses to CGRP (1 µg·kg−1)-induced dilatation were performed, 15 min apart, and at least 10 min later 10 mg·kg−1 iodowillardiine (n= 6) was administered intravenously and then the CGRP-induced dilatation was repeated at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min after the agonist treatment.

Data analysis

The effects of electrical stimulation and CGRP administration on dural vessel diameter were calculated as a percentage increase from the pre-stimulation baseline diameters. The nature of the experimental set-up, where the magnification of the dural vessel visualized was different in each animal by virtue of selecting an appropriate target vessel, made it impossible to standardize the dural vessel measurement; therefore, the change in dural vessel diameter is reported as a percentage change from pre-stimulation diameter (baseline maximal stimulation response = 100%). All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.mean. Statistical analysis was performed by using an analysis of variance for repeated measures with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple comparisons followed by Student's paired t-test. To compare the effect of iodowillardiine only, UBP 302 only and iodowillardiine with UBP 302 an independent samples t-test was used (spss version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significance was assessed at the P < 0.05 level.

Drugs and materials

Pentobarbital sodium salt was obtained from Sigma Chemical (Poole, Dorset, UK). The delivery of anaesthetic and experimental drugs was via different femoral catheters. In the experiments where more than one drug was given intravenously, the line was always flushed with saline prior to administration. Both iodowillardiine and UBP 302 (Tocris Cookson Inc., Bristol, UK) were dissolved in saline (pH 8). In control experiments equal volumes of vehicle only were administered. CGRP (rat; Tocris Cookson Inc.) was initially dissolved in distilled water, aliquoted and frozen. Subsequent dilutions were made in 0.9% saline before injection at a dose of 1 µg·kg−1. All drugs were made fresh on the morning of an experiment and administered in volumes ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mL.

The homeothermic blanket (TC-1000 Temperature Controller) was from CWE Inc. (Ardmore, PA, USA); small rodent ventilator (model 683), Harvard Apparatus Ltd. (Edenbridge, Kent, UK); the CO2 monitor (Capstar-100), CWE Inc. (Ardmore, PA, USA); CED spike2v5 software, CED (Cambridge, UK); intravital microscope (Microvision MV2100), Finlay Microvision (Warwickshire, UK); video dimension analyser, Living Systems Instrumentation (Burlington,VT, USA); bipolar stimulating electrode (NE 200X), Clarke Electromedical Instruments (Pangbourne, UK); Grass stimulator S88, Grass Instruments (Quincy, MA, USA).

Results

Baseline blood pressure and respiratory values were within normal limits for all animals included in the analysis.

Visualized branches of the middle meningeal artery through the closed cranial window with diameter ranging from 90 to 140 µm were studied. Electrical stimulation (50–150 µA) of the cranial window produced control responses in the range of 50–180% increase in dural blood vessel diameter (n= 31), compared with baseline diameter at rest. Neurogenic dilatation lasted between 2 and 3 min, following which vessels returned to their baseline diameter. For each animal, mean control responses were set as maximum dilatation of 100% ± s.e.mean. Electrical stimulation had no effects on blood pressure.

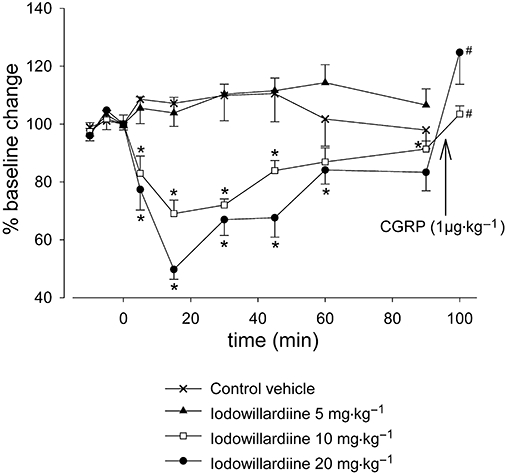

Effects of iodowillardiine on NDV

The iGluR5 receptor agonist iodowillardiine given intravenously at 5 mg·kg−1 had no effect on the responses to electrical stimulation of the cranial window, but a significant attenuation was observed at 10 (F3,12= 8.2; P < 0.005; Figure 1; Table 1) and 20 mg·kg−1 (F3,15= 14.3; P < 0.001; Figure 1; Table 1). At both doses iodowillardiine produced its maximal effect after 15 min, and responses were not fully recovered 90 min after drug administration. Iodowillardiine at 20 mg·kg−1 inhibited NDV by 50% (t5= 5.2; P < 0.005; n= 6), and 90 min after treatment with iodowillardiine NDV had not fully recovered to baseline. CGRP (1 µg·kg−1, i.v.), at least 10 min after the 90 min neurogenic-induced dilatation, caused maximum dilatation comparable to the vessel dilatation recorded during baseline NDV, prior to iodowillardiine administration. The CGRP-induced dilatation was significantly different (t5=−4.2; P < 0.05) from the neurogenic dilatation recorded at 90 min after iodowillardiine treatment, indicating that the vessel was still responding. None of the three doses had any effect on the vessel diameter at rest, and after each neurogenic dilatation following iodowillardiine administration vessel diameter returned to levels recorded at rest. Control vehicle injections demonstrated no significant effect (Figure 1). Neither control vehicle nor iodowillardiine at all three doses had any effects on blood pressure.

Figure 1.

Effect of intravenous administration of iodowillardiine (5, 10 and 20 mg·kg−1) on neurogenic vasodilatation. Following control responses to electrical stimulation, rats were injected with iodowillardiine at 5 (n= 6), 10 (n= 6) or 20 (n= 6) mg·kg−1, and electrical stimulation was repeated after 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min. Both 10 and 20 mg·kg−1 doses of iodowillardiine inhibited neurogenic dural vasodilatation. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) (1 µg·kg−1) was given intravenously after the 90 min neurogenic-induced dilatation, and the CGRP-induced dilatation was significantly different from the neurogenic dilatation recorded 90 min after iodowillardiine treatment. *P < 0.05 significance compared with the control response. #P < 0.05 significance compared with the 90 min response to electrical stimulation.

Table 1.

Effects of intravenous injection of iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1), iodowillardiine (20 mg·kg−1), UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1), co-administration of 10 mg·kg−1 iodowillardiine and 50 mg·kg−1 UBP 302 and control vehicle on neurogenic dural vasodilatation

| Time |

Increase in dural vessel diameter (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) | Iodowillardiine (20 mg·kg−1) | UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1) | Iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) & UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1) | Control vehicle | |

| Control response | 179 ± 7 | 197 ± 25 | 168 ± 7 | 180 ± 14 | 165 ± 12 |

| 5 min | 165 ± 8 | 178 ± 24 | 166 ± 7 | 184 ± 20 | 170 ± 12 |

| *(t5= 2.7, n= 6) | |||||

| 15 min | 150 ± 5 | 152 ± 17 | 158 ± 3 | 181 ± 18 | 168 ± 11 |

| *(t5= 7.2, n= 6) | *(t5= 5.2, n= 6) | ||||

| 30 min | 149 ± 6 | 164 ± 17 | 154 ± 5 | 186 ± 16 | 171 ± 13 |

| *(t5= 9.9, n= 6) | *(t5= 3.1, n= 6) | ||||

| 45 min | 151 ± 6 | 167 ± 22 | 157 ± 8 | 181 ± 16 | 170 ± 10 |

| *(t5= 5.3, n= 6) | *(t5= 3.2, n= 6) | ||||

| 60 min | 160 ± 4 | 183 ± 22 | 158 ± 14 | 186 ± 16 | 164 ± 7 |

| *(t5= 3.4, n= 6) | |||||

| 90 min | 165 ± 4 | 181 ± 21 | 157 ± 13 | 189 ± 19 | 164 ± 11 |

| *(t5=−1.0, n= 6) | |||||

UBP 302, (S)-1-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione.

P < 0.05 compared with control responses.

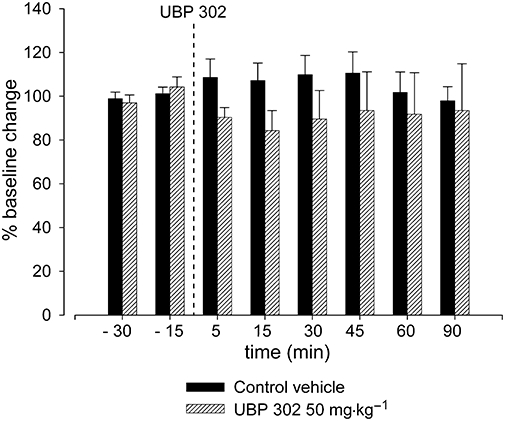

Effect of UBP 302 on NDV

The iGluR5 receptor antagonist UBP 302 given intravenously at 50 mg·kg−1, elicited a non-significant decrease in NDV (F1,5= 0.6; P= 0.5; n= 5; Figure 2). UBP 302 administration did not attenuate the diameter of the vessels under observation at rest prior to electrical stimulation and at the dose of 50 mg·kg−1 did not elicit any significant blood pressure changes. Control vehicle injections demonstrated no significant effect.

Figure 2.

Effect of UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1) on neurogenic vasodilatation. Following control responses to electrical stimulation, rats were intravenously injected with UBP 302 at 50 mg·kg−1 (n= 5), and electrical stimulation was repeated after 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min. No significant effect was observed. UBP 302, (S)-1-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione.

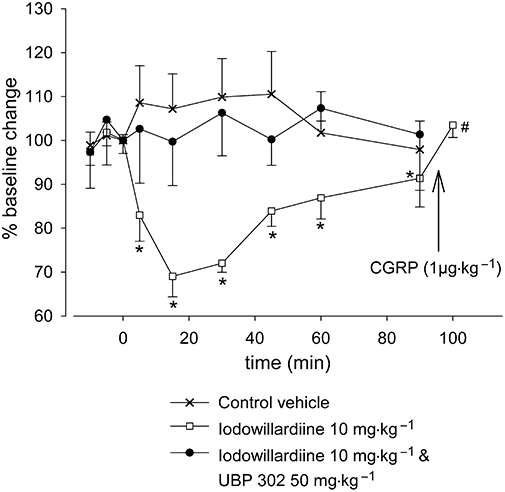

Effects of iodowillardiine and UBP 302 on NDV

Iodowillardiine given alone at 10 mg·kg−1 significantly inhibited NDV by 31% (t5= 7.2; P < 0.001; n= 6; Figures 1 and 3; Table 1). Ninety minutes after iodowillardiine treatment, full recovery was not observed after electrical stimulation, and CGRP (1 µg·kg−1) was given intravenously to test vessel response. The iGluR5 receptor antagonist UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1) given alone did not cause any significant changes in vessels response to electrical stimulation of the cranial window (F1,5= 0.6; P= 0.5; n= 5; Figure 2). However, pretreatment with UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1) 5 min prior to the administration of iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) reversed the inhibition of NDV (F2,11= 0.6; P= 0.6; n= 6; Figure 3) caused by iodowillardiine when administered alone. Grouped comparisons of UBP 302 when administered alone (Figure 2) and UBP 302 given intravenously pre-iodowillardiine treatment showed no significant difference between the two experimental set-ups.

Figure 3.

Effect of intravenous administration of iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) on neurogenic dural vasodilatation and the effect of pretreatment with UBP 302 (50 mg·kg−1). After control responses to electrical stimulation, either iodowillardiine at 10 mg·kg−1 was injected (n= 6) or animals were pretreated with UBP 302 at 50 mg·kg−1 5 min before iodowillardiine (n= 6) and electrical stimulation was repeated at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min. Inhibition of neurogenic dural vasodilatation was seen in response to iodowillardiine, and the response had not fully recovered after 90 min; CGRP (1 µg·kg−1) injected after the 90 min electrical stimulation produced maximum dilatation. The inhibitory response to iodowillardiine was reversed by the iGluR5 antagonist UBP 302. CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; iGluR, ionotropic glutamate receptor; UBP 302, (S)-1-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione. *P < 0.05 compared with control response. #P < 0.05 compared with the 90 minute response to electrical stimulation.

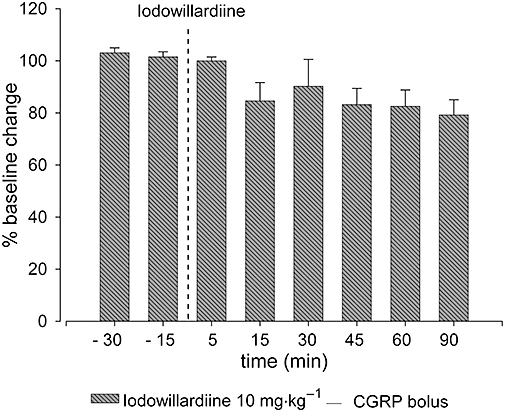

Effects of iodowillardiine on CGRP-induced dural vasodilatation

Calcitonin gene-related peptide bolus injections were used to induce dural vasodilatation in response to activation of CGRP receptors on the vessel walls. Systemic administration of CGRP at 1 µg·kg−1 was able to produce reproducible dural blood vessel dilatation in the range of 75–155% (n= 6) and resulted in a transient decrease in blood pressure of 29 ± 4%, lasting 1–2 min, compared with baseline levels at rest. For each animal, mean control responses were set as maximum dilatation of 100% ± s.e.mean. Intravenous administration of iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) had no significant effect on CGRP-induced vasodilatation, compared with baseline levels (F2,11= 2.8; P= 0.1; n= 6; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of intravenous iodowillardiine (10 mg·kg−1) on calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) bolus-induced vasodilatation. Following control responses to CGRP administration, rats were injected with iodowillardiine at 10 mg·kg−1, and CGRP injection was repeated after 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 and 90 min. Overall, no significant effect of iodowillardiine on CGRP-induced vasodilatation was observed.

Discussion

The kainate iGluR5 selective receptor agonist iodowillardiine was able to attenuate significantly NDV at a dose of 20 mg·kg−1 by a maximum of 50%, and this inhibition was blocked by pretreatment with the selective iGluR5 receptor antagonist UBP 302. When the antagonist UBP 302 was administrated alone it caused no inhibition or further dilatation of the blood vessels under investigation. These data indicate that activation of the iGluR5-carrying kainate receptors inhibits neurogenic vasodilatation at the peripheral terminal of trigeminal nerve and its vasculature. Blockade of these receptors with the antagonist UBP 302 does not elicit any significant effects. Iodowillardiine failed to inhibit vasodilatation induced by systemic administration of CGRP. As CGRP is probably acting directly on CGRP receptors on the smooth muscle of dural arteries to induce dural vasodilatation (Williamson et al., 1997a,b), the failure of iodowillardiine to block this effect at concentrations that were able to significantly inhibit NDV suggests that iodowillardiine is acting at the prejunctional site. An action on the trigeminal ganglion neurons is also possible, although the local nature of the stimulation applied and the local vasodilatation recorded favour the prejunctional site of action. The level of the current applied on the cranial window and the short duration of the application, along with previous studies demonstrating that CGRP antagonists completely inhibit NDV (Williamson et al., 1997a), all favour an important role for activation of Aδ fibres. The data are compatible with the existence of a presynaptic iGluR5 kainate receptor on trigeminovascular nerve terminals in the dura mater.

Although information about the presence of kainate receptors on trigeminal peripheral processes is not available from anatomical studies, data from this study favour the existence of iGluR5 kainate receptors at this site. iGluR5 receptors have been found in the trigeminal ganglia and on primary afferents in the spinal cord and caudal brainstem (Sahara et al., 1997; Lucifora et al., 2006). The trigeminal ganglion is bipolar, with its peripheral afferent fibres innervating the dural structures and centrally projecting to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis. The pharmacology of the peripheral and central projections of the trigeminal ganglion in general mirror each other; thus, work demonstrating the presence of kainate receptors on central primary afferents may also apply on the neuronal mechanisms involving the peripheral trigeminal afferents. In agreement with this, there is evidence of functional kainate receptors on peripheral sensory axons (Carlton et al., 1995; Coggeshall and Carlton, 1998; Kinkelin et al., 2000).

The blockage of NDV by iodowillardiine may involve either presynaptic or postsynaptic receptors, or both. To examine this further, iodowillardiine at concentrations that were able to inhibit NDV significantly was unable to block dilatation induced by exogenous CGRP. Due to a direct action of exogenous CGRP on postsynaptic CGRP receptors on the smooth muscle of dural arteries, it is likely that iodowillardiine has no effect on dural vessels. There is no current anatomical evidence for the presence of kainate receptors on dural vessels, although the complete absence or expression of non-functional kainate receptors on cerebral vessels has been suggested (Faraci et al., 1994; Morley et al., 1998; St’astny et al., 2002). In addition, detection of kainate receptors on the heart and cardiac nerve terminals has been also demonstrated, but a functional role has not been shown (Gill et al., 1998; 2007). Results from the present study, as shown with both the iGluR5 kainate agonist and antagonist, support the absence of at least functional iGluR5-carrying kainate receptors on dural vessels.

Neurogenic dural vasodilatation has been shown to be almost completely blocked by the CGRP antagonist CGRP8–37, and as such the observed dilatation is due to the release of CGRP from the trigeminal peripheral prejunctional site, acting on CGRP receptors on the vessels (Williamson et al., 1997a). The data presented in this study indicate a prejunctional effect for iodowillardiine on the trigeminovascular system, probably from a reduction of CGRP release from peptidergic trigeminal afferents. As iodowillardiine was able to reduce the degree of meningeal vasodilatation by 50%, the new data suggest that iGluR5 activation does not completely block the presynaptic release of CGRP. The mechanism of iodowillardiine activation of iGluR5 kainate receptors resulting in reduction of CGRP release is not known. It has been proposed that presynaptic spinal kainate receptors function as autoreceptors at primary afferent synapses in the dorsal horn (Agrawal and Evans, 1986), and Kerchner et al. (2001) demonstrated that activation of presynaptic kainate receptors carrying the iGluR5 subunit, by specific agonists acting at a presynaptic locus, reduces glutamate release from primary afferent sensory synapses. In our study it is possible that the selective iGluR5 receptor agonist iodowillardiine inhibits transmitter release from the prejunctional site in a similar manner as with central primary afferents, and thus partially reduces CGRP release from the peripheral end of the trigeminal nerve. The absolute mechanism of regulation of neurotransmitter release by kainate receptors remains to be established (Kerchner et al., 2001; Lerma, 2003). Previous studies on presynaptic kainate receptors in central brain synapses indicate that strong activation of kainate receptors leads to inhibition of glutamate release (Huettner, 2003; Lerma, 2003), possibly by inactivating calcium or sodium channels, or both (Kamiya and Ozawa, 2000). As release of both glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal neurons is controlled by calcium channels (Xiao et al., 2008), it is likely that strong activation of kainate receptors, which could be achieved by systemic administration of selective agonists, inactivates calcium channels and reduces neurotransmitter release. Metabotropic mechanisms have also been suggested to play a role in central presynaptic kainate receptor-mediated reductions in neurotransmitter (Negrete-Diaz et al., 2006). In the hippocampus, biphasic effects of kainate receptors have been reported, showing that weak activation enhances neurotransmitter release through both ionotropic and metabotropic mechanisms (Kamiya, 2002; Lerma, 2003; Rodriguez-Moreno and Sihra, 2004). Such bidirectional effects, however, have not been found for presynaptic kainate receptors on sensory fibres. Inhibition of glutamate and neuropeptides release following activation of kainate receptors is in agreement with the proposed role of other iGluRs on sensory fibres (Lee et al., 2002; Bardoni et al., 2004). The fact that blockade of the iGluR5 receptors with UBP 302 did not cause any change in baseline dilatation or neurogenic-induced dilatation could suggest that kainate receptors at the prejunctional site are not tonically activated, but when selectively activated can regulate dural vessel diameter. UBP 302 is not degraded in the blood, so when co-applied with iodowillardiine it blocked the iodowillardiine-induced inhibition of NDV. The possibility of iGluR5 activation by endogenous glutamate release and subsequent regulation of glutamate and CGRP release at the peripheral trigeminal end cannot be excluded (DeGroot et al., 2000; Huettner et al., 2002).

Because ganglionic sympathetic efferents in normal rats largely do not express kainate receptors (Carlton et al., 1998; Coggeshall and Carlton, 1999), it is unlikely that the kainate receptor agonist caused the release of noradrenaline or vasoconstrictor peptides in our experiments. The fact that NDV is not affected by either α1/α2-adrenoreceptor agonists and antagonists, as well as β-adrenoceptor antagonists further illustrates that the adrenergic system does not play a significant role in the pharmacology of neurogenic trigeminovascular responses in the dura mater (Akerman et al., 2001). Our data are consistent with the common feature of compounds that successfully inhibit NDV with a possible effect on Aδ trigeminal afferents to inhibit the release of CGRP.

The selectivity of the compounds used over kainate receptors has been demonstrated on native and recombinant kainate receptors. Iodowillardiine showed high selectivity on native iGluR5 dorsal root ganglia kainate receptors (EC50 140 nmol·L−1) over hippocampal AMPA receptors (EC50 19 µmol·L−1) (Wong et al., 1994) and is one of the most potent kainate agonists defined to date. Iodowillardiine potently activates homomeric iGluR5 and heteromeric iGluR5/KA2 kainate receptors but shows no activity on homomeric iGluR6 or iGluR7, displaying a greater than 400 000-fold selectivity for iGluR5 over iGluR6 kainate receptors, and only weak activity on heteromers of iGluR6 and 7 with KA2 (Jane et al., 1997; Swanson et al., 1998). The higher selectivity of UBP 302 for kainate receptors activated by iodowillardiine over AMPA receptors has been previously demonstrated in vivo in the trigeminocervical complex (Andreou et al., 2007b). UBP 302 demonstrates similar affinity for homomeric and heteromeric iGluR5 kainate receptors (Kd 402 nmol·L−1), but very little affinity on iGluR6 kainate receptors (Kd 36180 nmol·L−1) (More et al., 2004). Both compounds display no activity at NMDA receptors. The demonstration that kainate receptors in trigeminal ganglia neurons are heteromeric iGluR5/KA2 assemblies (Sahara et al., 1997) further supports the assertion that the compounds used were selectively acting on iGluR5-carrying kainate receptors.

Results from this study support a role of iGluR5 receptor agonists as a potential approach to the development of anti-migraine therapies consistent with previous work (Filla et al., 2002; Sang et al., 2004; Weiss et al., 2006), although suggesting other possible mechanisms of action, as the anti-nociceptive effects in these models in which kainate receptors were blocked are more likely to be due to the central actions of the compounds used. In a recent clinical study the highly selective kainate receptor antagonist LY466195 was effective in aborting migraine attacks (reported by Johnson, KW, International Headache Research Symposium, Copenhagen 2007) and has also been shown to inhibit trigeminovascular activation in an animal model (Weiss et al., 2006). Consistent with our data, LY466195 failed to inhibit NDV as well as CGRP- and capsaicin-induced dilatation (Chan et al., 2009), further suggesting that kainate receptor antagonists do not exhibit their anti-nociceptive effects via peripheral mechanisms. In this context anti-nociceptive effects of iGluR5 activation have been demonstrated previously; the iGluR5-specific agonist (RS)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-tert-butylisoxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid was shown to increase the hindpaw withdrawal latency to thermal and mechanical stimulation in rats (Wu et al., 2003).

In vivo studies, in which intravital microscopy techniques were used, showed that topical application of kainate or the iGluR5-specific agonist (RS)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-tert-butylisoxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid on the cranial window could cause a small but significant dilatation of the underlying dural vessels, an effect blocked by a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor (Faraci et al., 1994) or by haeme oxygenase (Robinson et al., 2002). Results from these studies suggest that kainate has no direct effect on dural blood vessels and that kainate-induced dilatation on both dural and cerebral arterioles is due to the formation of nitric oxide or carbon monoxide from an extravascular source (Faraci et al., 1994; Robinson et al., 2002). In our studies both the iGluR5 receptor agonist and antagonist, used at high doses and administered intravenously, had no effects on vessel tone at rest but had an effect on neurogenic-induced dilatation, which involves low intensity brief electrical stimulation of the cranial window. These differences could be due to the different drugs used, as both UBP 302 and iodowillardiine are highly selective for iGluR5 and are derivatives from the same precursor, willardiine (Swanson et al., 1998; More et al., 2004), as well as due to the different techniques that were applied. Furthermore, the absence of an effect on vessel tone by both willardiine derivatives used is unlikely to be due to the anaesthetic, as it is a well-established regimen that has not been observed to alter blood vessel diameter or blood flow in previous studies (Akerman et al., 2001; Akerman and Goadsby, 2005a; Holland et al., 2005). In previous studies, where the same anaesthetic and methods were used, other compounds have been shown to affect vascular tone (Akerman et al., 2001; Akerman and Goadsby, 2005a), and this is usually as a consequence of blood pressure changes. These observations suggest that pentobarbital itself has no effect on vascular tone.

Neurogenic dural vasodilatation is an established model of trigeminal activation and has proved to be highly predictive of anti-migraine efficacy (Williamson et al., 1997b,c; Akerman and Goadsby, 2005c). However, as the method does not investigate the central component of the trigeminovascular system, the efficacy of many anti-migraine compounds that act centrally may not be seen by using this model. To our knowledge both the iGluR5 agonist and antagonist used in our study have not been previously described in in vivo models and no data exist for blood–brain barrier penetration, although the existence of carboxylic groups on both compounds suggest decreased lipophilicity. The restricted blood–brain barrier penetration of the agonist used, as suggested from its structure, makes it unlikely that the compound had any effects on central medullary nuclei that control cardiovascular reflexes. As NDV is based on local stimulation of peripheral trigeminal afferents, compounds that can inhibit the vasodilator response are likely to have at least a peripheral effect on the trigeminal nerve, including the ganglion. Moreover, as peripheral inflammatory pain may be augmented by kainate receptor activation (Du et al., 2006), it seems likely that the full implications of the involvement of these receptors in trigeminovascular nociceptive mechanisms will only be understood by exploring the central pharmacology of these targets. Because CGRP receptor antagonists are effective in acute migraine (Olesen et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2008), the pharmacology of the control mechanisms for dural CGRP release by kainate receptors are of direct relevance to the development of newer migraine therapies.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that activation of the peripheral iGluR5 kainate receptors with the selective agonist iodowillardiine is able to inhibit NDV as monitored by intravital microscopy. This effect is likely to result from inhibition of prejunctional release of CGRP from trigeminal neurons. From these data kainate iGluR5 receptor agonists acting peripherally may be novel approaches to anti-migraine therapy, although their central effects on this receptor class require further study with appropriate methods and compounds.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- iGluR

ionotropic glutamate receptor

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NDV

neurogenic dural vasodilatation

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- UBP 302

(S)-1-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-3-(2-carboxybenzyl)pyrimidine-2,4-dione

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Agrawal SG, Evans RH. The primary afferent depolarizing action of kainate in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1986;87:345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. The role of dopamine in a model of trigeminovascular nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005a;314:162–169. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate inhibits cortical spreading depression in rat and cat: impact in migraine aura. Neuroreport. 2005b;16:1383–1387. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000175250.33159.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Topiramate inhibits trigeminovascular activation: an intravital microscopy study. Br J Pharmacol. 2005c;146:7–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Williamson D, Hill RG, Goadsby PJ. The effect of adrenergic compounds on neurogenic dural vasodilatation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;424:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. Vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1) evoked CGRP release plays a minor role in causing dural vessel dilation via the trigeminovascular system. Cephalalgia. 2002a;22:572. [Google Scholar]

- Akerman S, Williamson DJ, Kaube H, Goadsby PJ. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors can antagonise neurogenic and calcitonin gene-related peptide induced dilation of dural meningeal vessels. Br J Pharmacol. 2002b;137:62–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreou AP, Storer RJ, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. CNQX inihibits trigeminovascular neurons in the rat: a microiontophoresis study. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1383. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou AP, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. GluR5 kainate receptor activation inhibits trigeminal neurogenic dural vasodilation. Cephalalgia. 2007a;27:608. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou AP, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Pre- and post-synaptic involvement of GluR5 kainate receptors in trigeminovascular nociceptive processing. Cephalalgia. 2007b;27:605. [Google Scholar]

- Ault B, Hildebrand LM. Activation of nociceptive reflexes by peripheral kainate receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:927–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni R, Torsney C, Tong CK, Prandini M, Macdermott AB. Presynaptic NMDA receptors modulate glutamate release from primary sensory neurons in rat spinal cord dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2774–2781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4637-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergerot A, Holland PR, Akerman S, Bartsch T, Ahn AH, Maassenvandenbrink A, et al. Animal models of migraine. Looking at the component parts of a complex disorder. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1517–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton SM, Hargett GL, Coggeshall RE. Localization and activation of glutamate receptors in unmyelinated axons of rat glabrous skin. Neurosci Lett. 1995;197:25–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton SM, Chung K, Ding Z, Coggeshall RE. Glutamate receptors on postganglionic sympathetic axons. Neuroscience. 1998;83:601–605. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KY, Gupta S, Van Veghel R, De Vries R, Danser AHJ, Maassen Van Den Brink A. Distinct effects of several glutamate receptor antagonists on rat dural artery diameter in a rat intravital microscopy model. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:101. [Google Scholar]

- Classey JD, Knight YE, Goadsby PJ. The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 reduces Fos-like immunoreactivity within the trigeminocervical complex following superior sagittal sinus stimulation in the cat. Brain Res. 2001;907:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Carlton SM. Ultrastructural analysis of NMDA, AMPA, and kainate receptors on unmyelinated and myelinated axons in the periphery. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:78–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980202)391:1<78::aid-cne7>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggeshall RE, Carlton SM. Evidence for an inflammation-induced change in the local glutamatergic regulation of postganglionic sympathetic efferents. Pain. 1999;83:163–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degroot J, Zhou S, Carlton SM. Peripheral glutamate release in the hindpaw following low and high intensity sciatic stimulation. Neuroreport. 2000;11:497–502. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002280-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Zhou S, Carlton SM. Kainate-induced excitation and sensitization of nociceptors in normal and inflamed rat glabrous skin. Neuroscience. 2006;137:999–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraci FM, Breese KR, Heistad DD. Responses of cerebral arterioles to kainate. Stroke. 1994;25:2080–2083. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.10.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filla SA, Winter MA, Johnson KW, Bleakman D, Bell MG, Bleisch TJ, et al. Ethyl (3S,4aR,6S,8aR)-6-(4-ethoxycar-bonylimidazol-1-ylmethyl)decahydroiso-quinoline-3-carboxylic ester: a prodrug of a GluR5 kainate receptor antagonist active in two animal models of acute migraine. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4383–4386. doi: 10.1021/jm025548q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S, Veinot J, Kavanagh M, Pulido O. Human heart glutamate receptors – implications for toxicology, food safety, and drug discovery. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:411–417. doi: 10.1080/01926230701230361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Pulido OM, Mueller RW, Mcguire PF. Molecular and immunochemical characterization of the ionotropic glutamate receptors in the rat heart. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46:429–434. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goadsby PJ. Migraine pathophysiology. Headache. 2005;45:S14–S24. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.4501003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsby PJ, Keywood C. Investigation of the role of mGluR5 inhibition in migraine: A proof of concept study of ADX10059 in acute treatment of migraine. Neurology. 2009;72(Suppl. 1) in press. [Google Scholar]

- Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine – current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:257–270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. (2nd edn.) 2004;24:1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ho T, Mannix L, Fan X, Assaid C, Furtek C, Jones C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an oral CGRP antagonist, MK-0974, in acute treatment of migraine. Neurology. 2008;70:1004–1012. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000286940.29755.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PR, Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Orexin 1 receptor activation attenuates neurogenic dural vasodilation in an animal model of trigeminovascular nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1380–1385. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner JE. Kainate receptors and synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:387–407. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner JE, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M. Glutamate and the presynaptic control of spinal sensory transmission. Neuroscientist. 2002;8:89–92. doi: 10.1177/107385840200800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Pagliardini S, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Presynaptic kainate receptors in primary afferents to the superficial laminae of the rat spinal cord. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:275–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane DE, Hoo K, Kamboj R, Deverill M, Bleakman D, Mandelzys A. Synthesis of willardiine and 6-azawillardiine analogs: pharmacological characterization on cloned homomeric human AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3645–3650. doi: 10.1021/jm9702387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KW, Nisenbaum ES, Johnson MP, Dieckman DK, Clemens-Smith A, Siuda ER, et al. Innovative drug development for headache disorders: glutamate. In: Olesen J, Ramadan N, editors. Frontiers in Headache Research. New York: Oxford; 2008. pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CK, Alt A, Ogden AM, Bleakman D, Simmons RM, Iyengar S, et al. Antiallodynic and antihyperalgesic effects of selective competitive GLUK5 (GluR5) ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists in the capsaicin and carrageenan models in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:396–404. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H. Kainate receptor-dependent presynaptic modulation and plasticity. Neurosci Res. 2002;41:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H, Ozawa S. Kainate receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol. 2000;523:653–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Wilding TJ, Li P, Zhuo M, Huettner JE. Presynaptic kainate receptors regulate spinal sensory transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:59–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkelin I, Brocker EB, Koltzenburg M, Carlton SM. Localization of ionotropic glutamate receptors in peripheral axons of human skin. Neurosci Lett. 2000;283:149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knyihar-Csillik E, Toldi J, Krisztin-Peva B, Chadaide Z, Nemeth H, Fenyo R, et al. Prevention of electrical stimulation-induced increase of c-fos immunoreaction in the caudal trigeminal nucleus by kynurenine combined with probenecid. Neurosci Lett. 2007;418:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko S, Zhao MG, Toyoda H, Qiu CS, Zhuo M. Altered behavioral responses to noxious stimuli and fear in glutamate receptor 5 (GluR5)- or GluR6-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:977–984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4059-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa M, Messlinger K, Pawlak M, Schmidt RF. Increase of meningeal blood flow after electrical stimulation of rat dura mater encephali: mediation by calcitonin gene-related peptide. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:1397–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ, Bardoni R, Tong CK, Engelman HS, Joseph DJ, Magherini PC, et al. Functional expression of AMPA receptors on central terminals of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons and presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release. Neuron. 2002;35:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerma J. Roles and rules of kainate receptors in synaptic transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:481–495. doi: 10.1038/nrn1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora S, Willcockson HH, Lu CR, Darstein M, Phend KD, Valtschanoff JG, et al. Presynaptic low- and high-affinity kainate receptors in nociceptive spinal afferents. Pain. 2006;120:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May A, Goadsby PJ. Substance P receptor antagonists in the therapy of migraine. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:1–6. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsikostas DD, Sanchez Del Rio M, Waeber C, Moskowitz MA, Cutrer FM. The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 reduces capsaicin-induced c-fos expression within rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Pain. 1998;76:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsikostas DD, Sanchez Del Rio M, Waeber C, Huang Z, Cutrer FM, Moskowitz MA. Non-NMDA glutamate receptors modulate capsaicin induced c-fos expression within trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:623–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More JC, Nistico R, Dolman NP, Clarke VR, Alt AJ, Ogden AM, et al. Characterisation of UBP296: a novel, potent and selective kainate receptor antagonist. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:46–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley P, Small DL, Murray CL, Mealing GA, Poulter MO, Durkin JP, et al. Evidence that functional glutamate receptors are not expressed on rat or human cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:396–406. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrete-Diaz JV, Sihra TS, Delgado-Garcia JM, Rodriguez-Moreno A. Kainate receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release involves protein kinase A in the mouse hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1829–1837. doi: 10.1152/jn.00280.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J, Diener H-C, Husstedt I-W, Goadsby PJ, Hall D, Meier U, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist BIBN4096BS is effective in the treatment of migraine attacks. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1104–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek J, Neugebauer V, Carlton SM, Iyengar S, Willis WD. The effect of a kainate GluR5 receptor antagonist on responses of spinothalamic tract neurons in a model of peripheral neuropathy in primates. Pain. 2004;111:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M, Gunthorpe MJ, Strijbos PJ, Goldsmith P, Upton N, James MF. Effects of pan- and subtype-selective N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists on cortical spreading depression in the rat: therapeutic potential for migraine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:564–572. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RH, Jaeschke G, Spooren W, Ballard TM, Buttelmann B, Kolczewski S, et al. Fenobam: a clinically validated nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytic is a potent, selective, and noncompetitive mGlu5 receptor antagonist with inverse agonist activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:711–721. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Fedinec AL, Leffler CW. Role of carbon monoxide in glutamate receptor-induced dilation of newborn pig pial arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2371–H2376. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00911.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Moreno A, Sihra TS. Presynaptic kainate receptor facilitation of glutamate release involves protein kinase A in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2004;557:733–745. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.065029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Role of kainate receptors in nociception. Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahara Y, Noro N, Iida Y, Soma K, Nakamura Y. Glutamate receptor subunits GluR5 and KA-2 are coexpressed in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6611–6620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06611.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang CN, Ramadan NM, Wallihan RG, Chappell AS, Freitag FG, Smith TR, et al. LY293558, a novel AMPA/GluR5 antagonist, is efficacious and well-tolerated in acute migraine. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepheard SL, Williamson DJ, Beer MS, Hill RG, Hargreaves RJ. Differential effects of 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists on neurogenic dural plasma extravasation and vasodilation in anaesthetized rats. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:525–533. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RM, Li DL, Hoo KH, Deverill M, Ornstein PL, Iyengar S. Kainate GluR5 receptor subtype mediates the nociceptive response to formalin in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St'astny F, Schwendt M, Lisy V, Jezova D. Main subunits of ionotropic glutamate receptors are expressed in isolated rat brain microvessels. Neurol Res. 2002;24:93–96. doi: 10.1179/016164102101199468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner TJ, Scher AI, Stewart WF, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Lipton RB. The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, gender and ethnicity. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:519–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer RJ, Goadsby PJ. Trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission involves N-methyl-D-aspartate and non-N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptors. Neuroscience. 1999;90:1371–1376. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00536-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GT, Green T, Heinemann SF. Kainate receptors exhibit differential sensitivities to (S)-5-iodowillardiine. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:942–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MS, Hamamoto DT, Hodges JS, Maccecchini ML, Simone DA. SYM 2081, an agonist that desensitizes kainate receptors, attenuates capsaicin and inflammatory hyperalgesia. Brain Res. 2003;973:252–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Alt A, Ogden AM, Gates M, Dieckman DK, Clemens-Smith A, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the competitive GLUK5 receptor antagonist decahydroisoquinoline LY466195 in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:772–781. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Hargreaves RJ, Hill RG, Shepheard SL. Intravital microscope studies on the effects of neurokinin agonists and calcitonin gene-related peptide on dural blood vessel diameter in the anaesthetized rat. Cephalalgia. 1997a;17:518–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1704518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Hargreaves RJ, Hill RG, Shepheard SL. Sumatriptan inhibits neurogenic vasodilation of dural blood vessels in the anaesthetized rat-intravital microscope studies. Cephalalgia. 1997b;17:525–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1704525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Shepheard SL, Hill RG, Hargreaves RJ. The novel anti-migraine agent rizatriptan inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilation and extravasation. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997c;328:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DJ, Hill RG, Shepheard SL, Hargreaves RJ. The anti-migraine 5-HT1B/1D agonist rizatriptan inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilation in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff HG. Headache and Other Head Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wong LA, Mayer ML, Jane DE, Watkins JC. Willardiines differentiate agonist binding sites for kainate- versus AMPA-preferring glutamate receptors in DRG and hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3881–3897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03881.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DC, Zhou N, Yu LC. Anti-nociceptive effect induced by intrathecal injection of ATPA, an effect enhanced and prolonged by concanavalin A. Brain Res. 2003;959:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Richter JA, Hurley JH. Release of glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal ganglion neurons: role of calcium channels and 5-HT1 receptor signaling. Mol Pain. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]