Abstract

Background and purpose:

Neuropeptide S (NPS) is a recently identified neurotransmitter/neuromodulator able to increase arousal and wakefulness while decreasing anxiety-like behaviour. As several classical transmitters play a role in arousal and anxiety, we here investigated the possible presynaptic regulation of transmitter release by NPS.

Experimental approach:

Synaptosomes purified from mouse frontal cortex were prelabelled with [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), noradrenaline, dopamine, choline, D-aspartate or GABA and depolarized in superfusion with 12–15 mmol·L−1 KCl to evoke [3H]neurotransmitter exocytosis. NPS was added at different concentrations (0.001 to 100 nmol·L−1).

Key results:

NPS behaved as an extremely potent inhibitor of the evoked overflow of [3H]5-HT and [3H]noradrenaline exhibiting EC50 values in the low picomolar range. The inhibitory action of NPS on [3H]5-HT release was mimicked by [Ala2]NPS that was, however, about 100-fold less potent than the natural peptide. NPS (up to 100 nmol·L−1) was unable to affect the depolarization-evoked overflow of [3H]D-aspartate and [3H]GABA. The neuropeptide only weakly reduced the overflow of [3H]dopamine and [3H]ACh when added at relatively high concentrations.

Conclusions and implications:

NPS, at low picomolar concentrations, can selectively inhibit the evoked release of 5-HT and noradrenaline in the frontal cortex by acting directly on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic and noradrenergic nerve terminals. These direct effects may explain only in part the unique behavioural activities of NPS, while an indirect involvement of other transmitters, especially of glutamate, must be considered.

Keywords: Neuropeptide S, frontal cortex, 5-HT release, noradrenaline release, arousal, anxiety

Introduction

Neuropeptide S (NPS) is a recently discovered neurotransmitter/neuromodulator that has been identified as the natural ligand of a previously orphaned G-protein coupled receptor, now named the NPS receptor (Xu et al., 2004). Activation of NPS receptors by low nanomolar concentrations of the neuropeptide increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration and cAMP levels, suggesting that NPS receptors may be coupled with Gq and Gs proteins (Xu et al., 2004; Reinscheid et al., 2005).

Neuropeptide S precursor mRNA was found to be strongly expressed only in discrete regions in the rat brain, including the locus coeruleus, the principal sensory trigeminal nucleus and lateral parabrachial nucleus (Xu et al., 2004). The vast majority of NPS-expressing neurones in the locus coeruleus and the sensory trigeminal nucleus are glutamatergic, while many of the NPS-positive neurones in the lateral parabrachial nucleus also coexpress corticotrophin-releasing factor (Xu et al., 2007). In contrast to NPS precursor mRNA, NPS receptor mRNA was found widely expressed in many brain regions in a morphological study of in situ hybridization with 35S-labelled riboprobes (Xu et al., 2007).

As indicated by several studies, the NPS-NPS receptor system is involved in the control of different centrally mediated behaviours, including wakefulness and anxiety (Xu et al., 2004; Leonard et al., 2008; Rizzi et al., 2008; Vitale et al., 2008), food intake (Beck et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2006; Cline et al., 2007) and drug abuse (Ciccocioppo et al., 2007; Badia-Elder et al., 2008).

Some of the behavioural effects of NPS are particularly interesting, as the neuropeptide is able to mediate arousal/wakefulness as well as anxiolytic activities in rodents (Okamura and Reinscheid, 2007). Such a behavioural profile appears quite peculiar in comparison with that of other psychoactive agents, like stimulant drugs, which generally elicit arousal enhancement associated with increased anxiety (Hascoet and Bourin, 1998; Paine et al., 2002).

Very little is known about the mechanisms through which NPS induces arousal and anxiolytic effects. Several neurotransmitters, including classical transmitters and neuropeptides, have been reported to be involved in the regulation of arousal and/or anxiety (see Reinscheid and Civelli, 2002; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Jones, 2003; Millan, 2003); accordingly, the effects of NPS are probably due to interactions with various neurotransmitter systems. Interactions between neurotransmitters often occur through modulation of release mediated by presynaptic receptors (see Raiteri, 2006). In the case of NPS, the neuropeptide might modulate the release of other neurotransmitters through the activation of presynaptic NPS receptors. As no data have been reported about these interactions and considering that neuropeptides often exhibit modulatory function on classical neurotransmission, the aim of the present investigation was to ascertain whether NPS could modulate neurotransmitter release. Among the several transmitter systems potentially involved, we focused on a number of classical neurotransmitters known to be involved in the control of arousal, anxiety and/or sleep in cortical areas.

Evidence has been provided that noradrenaline is an important mediator of wakefulness and anxiety (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) also is known to play primary roles in sleep processes and in the generation of anxiety states (Handley, 1995; Murphy et al., 1999; Millan, 2003). More recently, the glutamatergic system has been heavily implicated in stress and anxiety (Moghaddam, 2002; Jones, 2003). GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in cortical areas, the GABAergic system plays a key role in the modulation of anxiety (Millan, 2003) and the mechanism of action of many anxiolytic drugs, like benzodiazepines, relies on the potentiation of GABAergic transmission.

In the present work, we studied the effects of NPS on the release of noradrenaline, 5-HT, glutamate, GABA, dopamine and ACh using mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes labelled with the appropriate radioactive neurotransmitters and depolarized in superfusion with concentrations of KCl known to evoke exocytosis. We found that low picomolar concentrations of NPS selectively reduced the evoked release of noradrenaline and 5-HT. The NPS analogue [Ala2]NPS mimicked the inhibitory effect of the natural peptide on [3H]5-HT release being, however, about 100-fold less potent.

Part of the data reported in the present work have been presented as a poster communication in the European Opioid Conference–European Neuropeptide Club Joint Meeting (Raiteri et al., 2008).

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experiments were in accordance with the European Community Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to use only the number of animals necessary to produce reliable results. Adult Swiss mice (weighing 20–25 g; Charles River, Calco, Italy) were used. Animals were housed at constant temperature (22 ± 1°C) and relative humidity (50%) under a regular light–dark schedule (lights on at 07.00 h and off at 19.00 h). Food and water were freely available.

Preparation of synaptosomes

Animals were killed by cervical dislocation and the frontal cortex was quickly removed. In order to prepare purified synaptosomes (Dunkley et al., 1988; Nakamura et al., 1993), the tissue was homogenized in 10 volumes of 0.32 mol·L−1 sucrose, buffered at pH 7.4 with Tris-HCl, using a glass-Teflon tissue grinder (clearance 0.25 mm, 12 up-down strokes in about 1 min). The homogenate was centrifuged (5 min, 1000×g at 4°C) to remove nuclei and debris and the supernatant was gently stratified on a discontinuous Percoll® gradient (2%, 6%, 10% and 20% in Tris-buffered sucrose) and centrifuged at 33 500×g for 5 min. The layer between 10% and 20% Percoll® (synaptosomal fraction) was collected, washed by centrifugation and resuspended in a physiological medium (standard medium) having the following composition (mmol·L−1): NaCl, 140; KCl, 3; MgSO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.2; NaH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 5; glucose, 10; HEPES, 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. All the above procedures were performed at 0–4°C. Protein was determined according to Bradford (1976) using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Release experiments

Synaptosomes were incubated at 37°C for 15 min in the presence of the appropriate radioactive tracer: [3H]5-HT (0.07 µmol·L−1), [3H]noradrenaline (0.1 µmol·L−1), [3H]dopamine (0.1 µmol·L−1), [3H]choline (0.07 µmol·L−1), [3H]GABA (0.02 µmol·L−1) or [3H]D-aspartate (0.05 µmol·L−1) used as a marker of endogenous glutamate (see Raiteri et al., 2007). To achieve selective labelling of serotonergic nerve terminals, in the experiments of [3H]5-HT release, incubation with the radioactive neurotransmitter was performed in the presence of the noradrenaline uptake inhibitor desipramine (0.1 µmol·L−1) and of the dopamine uptake inhibitor GBR 12909 (0.1 µmol·L−1). Similarly, in the experiments of [3H]noradrenaline release, incubation with the radioactive tracer was performed in the presence of the 5-HT uptake inhibitor 6-nitroquipazine (0.1 µmol·L−1) and of GBR 12909 (0.1 µmol·L−1), and in the experiments of [3H]dopamine release incubation was performed in the presence of 0.1 µmol·L−1 desipramine and 0.1 µmol·L−1 6-nitroquipazine. In the experiments of [3H]GABA release, incubation with the radioactive transmitter was performed in the presence of 50 µmol·L−1 aminooxyacetic acid to prevent [3H]GABA metabolism.

At the end of incubation, identical aliquots of synaptosomal suspension (about 60 µg protein) were distributed on microporous filters placed at the bottom of a set of parallel superfusion chambers maintained at 37°C (Superfusion System, Ugo Basile, Comerio, Varese, Italy) and superfused with standard medium (containing 50 µmol·L−1 aminooxyacetic acid in the experiments of [3H]GABA release) supplemented with 0.1% polypep at a rate of 0.5 mL·min−1 (Raiteri and Raiteri, 2000).

Depolarization-evoked neurotransmitter release

After 36 min of superfusion, to equilibrate the system, fractions were collected as follows: two 3 min samples (t= 36–39 and 45–48 min; basal release) before and after one 6 min sample (t= 39–45 min; evoked release). A 90 s period of depolarization was applied at t= 39 min. As indicated, synaptosomes were depolarized with 12 or 15 mmol·L−1 KCl (substituting for an equimolar concentration of NaCl). NPS was added concomitantly with the depolarizing stimulus. Fractions collected and superfused filters were counted for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting.

Spontaneous neurotransmitter release

In one set of experiments, after 36 min of superfusion, to equilibrate the system, four 3 min fractions were collected. NPS was added to the superfusion medium at the end of the first fraction collected (t= 39 min). Fractions collected and superfused filters were counted for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting.

Calculations

Neurotransmitter release in each fraction collected was expressed as a percentage of the radioactivity content of synaptosomes at the start of the respective collection period (fractional rate ×100). Depolarization-evoked neurotransmitter overflow was calculated by subtracting the transmitter content of the basal release from the transmitter content in the 6 min fraction collected during and after the depolarization pulse. The effect of NPS was evaluated as the ratio of the depolarization-evoked neurotransmitter overflow calculated in the presence of the drug versus that obtained under control conditions.

In the experiments of spontaneous neurotransmitter release, the effect of NPS was evaluated by calculating the ratio between the transmitter efflux in the fourth fraction collected and that of the first fraction. This ratio was compared with the corresponding ratio obtained in the absence of NPS. Appropriate controls were always run in parallel.

Calcium mobilization experiments

HEK293 cells stably expressing the mouse NPS receptor were generated as previously described (Reinscheid et al., 2005) and maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 2 mmol·L−1 L-Glutamine, Hygromycin (100 mg·L−1) and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air. The cells were prepared for calcium mobilization experiments as previously described (Camarda et al., 2008). Concentrated solutions (1 mmol·L−1) of NPS and [Ala2]NPS were made in double-distilled water and kept at −20°C. Serial dilutions were carried out in HBSS/HEPES (20 mmol·L−1) buffer (containing 0.02% BSA fraction V). After placing both plates (cell culture and master plate) into the fluorometric imaging plate reader FlexStation II (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), fluorescence changes were measured at room temperature (22°C).

Materials

[3H]5-HT (specific activity: 87.0 Ci·mmoL−1), [3H]noradrenaline (specific activity: 38.0 Ci·mmoL−1), [3H]GABA (specific activity: 94.0 Ci·mmoL−1), [3H]D-aspartate (specific activity: 35.0 Ci·mmoL−1), [3H]choline (specific activity: 83.0 Ci·mmoL−1), [3H]dopamine (specific activity: 49.0 Ci·mmoL−1) were purchased from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, UK). NPS and [Ala2]NPS were synthesized according to published methods (Camarda et al., 2008) using Fmoc/tBu chemistry with a SYRO XP multiple peptide synthesizer (MultiSyntech, Witten, Germany). Crude peptides were purified by preparative reversed-phase HPLC and the purity checked by analytical HPLC and mass spectrometry using a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (Bruker BioScience, Billerica, MA, USA) and a ESI Micromass ZMD-2000 mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MS, USA). Percoll®, Polypep® and aminooxyacetic acid were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA), and 6-nitroquipazine was from Duphar BV (Amsterdam, the Netherlands).

Results

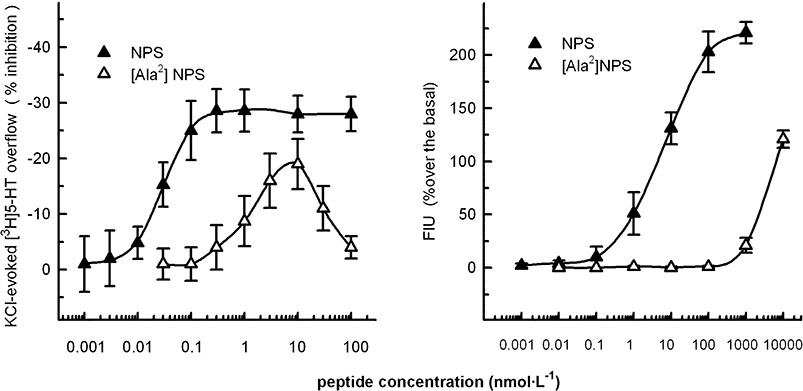

Figure 1 right panel shows that NPS concentration-dependently stimulated calcium mobilization in HEK293 cells stably expressing the mouse NPS receptors. The peptide maximal effects corresponded to 228 ± 22% over the basal values; the EC50 was 6.31 nmol·L−1. The NPS analogue [Ala2]NPS was inactive in the nmol·L−1 range of concentrations while it stimulated calcium mobilization only at the higher concentrations tested, that is, 1 and 10 µmol·L−1.

Figure 1.

Effects of neuropeptide S (NPS) and [Ala2]NPS on calcium mobilization in HEK293 cells expressing mouse NPS receptors (right panel) and on the KCl-evoked [3H]5-HT release from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes (left panel). Synaptosomes were depolarized in superfusion with 12 mmol·L−1 KCl; the peptides were added concomitantly with the depolarizing stimulus. See Methods for other technical details. The data presented are means ± SEM of three experiments made in duplicate (right panel) or three to five experiments in triplicate (left panel).

Purified mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes were depolarized by adding to the superfusion medium 12 mmol·L−1 KCl (experiments of [3H]5-HT, [3H]noradrenaline, [3H]D-aspartate and [3H]GABA release) or 15 mmol·L−1 KCl (experiments of [3H]dopamine and [3H]ACh release). These depolarizing stimuli were chosen because it had been previously found that neurotransmitter release evoked by depolarization of synaptosomes with 12–15 mmol·L−1 KCl occurs almost completely by Ca2+-dependent exocytosis. Depolarization with 12 or 15 mmol·L−1 KCl was chosen in order to test the effects of NPS on quantitatively comparable neurotransmitter overflows, possibly reflecting similar exocytotic efficiencies.

Figure 1 left panel shows that the 12 mmol·L−1 K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow (5.45 ± 0.41%; n= 8) was inhibited by NPS in a concentration-dependent manner (EC50= 0.03 nmol·L−1; Emax∼30%). The neuropeptide attained maximal inhibitory effect at 0.1 nmol·L−1. The maximal inhibitory effect of NPS (about 30%) remained stable up to 100 nmol·L−1. [Ala2]NPS mimicked the inhibitory effect of NPS being, however, almost 100-fold less potent. In addition, the concentration response curve to this peptide was clearly bell-shaped. NPS did not significantly affect the spontaneous release of [3H]5-HT when added up to 100 nmol·L−1 (see Table 1). The NPS effects were quantitatively similar when synaptosomes were depolarized with 15 mmol·L−1 KCl (not shown).

Table 1.

Effects of neuropeptide S (NPS) on the spontaneous neurotransmitter release from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes

| Neurotransmitter | Control basal release | % variation with 100 nmol·L−1NPS |

|---|---|---|

| [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine | 4.04 ± 0.19 (5) | −2.15 ± 4.31 (5) |

| [3H]noradrenaline | 2.53 ± 0.22 (5) | −2.01 ± 6.25 (5) |

| [3H]dopamine | 1.99 ± 0.11 (5) | 1.87 ± 4.99 (5) |

| [3H]Ach | 2.20 ± 0.15 (4) | 2.09 ± 2.19 (4) |

| [3H]D-aspartate | 0.68 ± 0.05 (3) | 0.71 ± 1.09 (3) |

| [3H]GABA | 3.36 ± 0.14 (4) | 2.55 ± 4.49 (4) |

Synaptosomes were superfused as described in Methods (Release experiments section). NPS was added at t= 39 min of superfusion. Spontaneous neurotransmitter release in the first fraction collected (t= 36–39 min; control basal release) is expressed as per cent fractional rate. The effect of NPS is expressed as per cent variation of the spontaneous neurotransmitter efflux. The data presented are means ± SEM of the number of experiments given in parentheses. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (three superfusion chambers for each experimental condition).

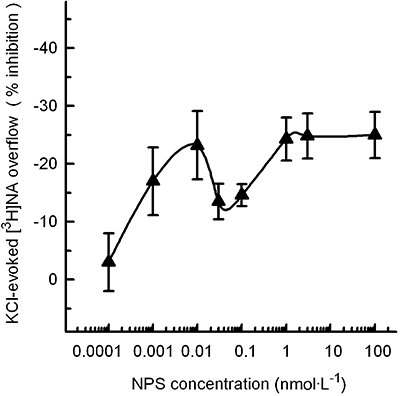

The NPS concentration-dependently reduced the 12 mmol·L−1 K+-evoked [3H]noradrenaline overflow from synaptosomes prelabelled with the radioactive neurotransmitter (Figure 2). The inhibition of [3H]noradrenaline release by NPS was a biphasic effect, exhibiting a first phase with a maximum (about 25% inhibition) observed at 0.01 nmol·L−1 NPS followed by a second phase (quantitatively similar inhibition) that reached a plateau at 1 nmol·L−1 (see Figure 2). Higher concentrations of NPS (100 nmol·L−1) did not reduce further the 12 mmol·L−1 K+-evoked [3H]noradrenaline overflow. As in the case of the basal [3H]5-HT release, the spontaneous release of [3H]noradrenaline was not significantly affected by NPS, up to 100 nmol·L−1 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Inhibition by neuropeptide S (NPS) of the KCl-evoked [3H]noradrenaline (NA) release from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were depolarized in superfusion with 12 mmol·L−1 KCl; NPS was added concomitantly with the depolarizing stimulus. See Methods for other technical details. The data presented are means ± SEM of three to six experiments in triplicate.

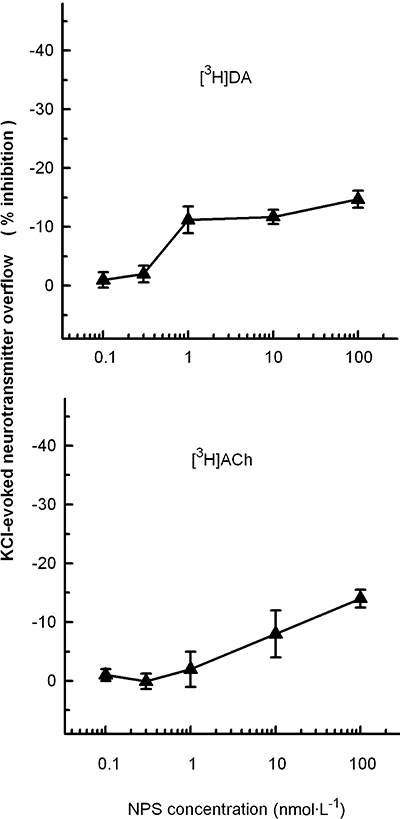

Interestingly, the effects of NPS on [3H]5-HT and [3H]noradrenaline release display a considerable degree of selectivity, as the neuropeptide had only slight, or no effects, on the release of the other neurotransmitters considered in the present study. When added at relatively high concentrations (1, 10 or 100 nmol·L−1), NPS slightly reduced the 15 mmol·L−1 K+-evoked overflow of [3H]dopamine and [3H]ACh from synaptosomes prelabelled with [3H]dopamine or with [3H]choline respectively (Figure 3). As shown in Table 1, NPS had no significant effect on the spontaneous release of [3H]dopamine and [3H]ACh.

Figure 3.

Effects of neuropeptide S (NPS) on the release of [3H]dopamine (DA) and [3H]ACh evoked by KCl depolarization from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were depolarized in superfusion with 15 mmol·L−1 KCl; NPS was added concomitantly with the depolarizing stimulus. See Methods for other technical details. The data presented are means ± SEM of three experiments run in triplicate.

Experiments were then performed with synaptosomes labelled with [3H]D-aspartate, an analogue of glutamate that is not metabolized and is frequently used as a marker of endogenous glutamate in release studies. Release of [3H]D-aspartate evoked by mild K+-depolarization from mouse cortical synaptosomes reliably reflects the release of endogenous glutamate (Raiteri et al., 2007). As reported in Table 2, NPS (1 or 100 nmol·L−1) did not affect the 12 mmol·L−1 KCl-evoked [3H]D-aspartate overflow from cortical synaptosomes, nor did it affect the spontaneous release of the excitatory transmitter (Table 1).

Table 2.

Effects of neuropeptide S (NPS) on the release of [3H]D-aspartate and [3H]GABA evoked by KCl depolarization from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes

|

Depolarization-evoked neurotransmitter release (% overflow) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | NPS (1 nmol·L−1) | NPS (100 nmol·L−1) | |

| [3H]D-aspartate | 3.04 ± 0.31 | 3.14 ± 0.29 | 2.88 ± 0.37 |

| [3H]GABA | 5.63 ± 0.61 | 5.28 ± 0.49 | 5.19 ± 0.44 |

Synaptosomes were depolarized by superfusion with 12 mmol·L−1 KCl; NPS was added concomitantly with the depolarizing stimulus. See Methods for other technical details. The data presented are means ± SEM of three experiments run in triplicate (three superfusion chambers for each experimental condition).

Finally, results from experiments performed with frontal cortex synaptosomes prelabelled with [3H]GABA and depolarized in superfusion with 12 mmol·L−1 KCl show that NPS, added at 1 or 100 nmol·L−1 (Table 2), was unable to significantly affect the evoked amino acid release. NPS had no significant effect on the spontaneous release of [3H]GABA either (Table 1).

Discussion and conclusions

Methodological considerations

Superfused synaptosomes were used to study the effects of NPS on neurotransmitter release. The superfusion technique is particularly useful to study release of neurotransmitters and its modulation through presynaptic mechanisms (Raiteri and Raiteri, 2000). In fact, release-regulating receptors are often localized on the releasing nerve terminals, and superfused synaptosomes have been successfully used in the identification of presynaptic receptors and in the pharmacological characterization of presynaptic receptor subtypes in different areas of rat, mouse and human CNS (see Raiteri, 2006). Briefly, synaptosomes are layered on microporous filters in such a low amount (<100 µg protein per filter) that, based on previous estimates, the particles constitute less than a monolayer. It has been clearly shown that, when such a monolayer is up-down superfused, any compound released is rapidly removed by the superfusion medium before it can feedback on the targets present in the preparation (transporters, presynaptic receptors and so on). Therefore, all these targets remain virtually ligand-free, and can be selectively activated by appropriate ligands added to the superfusion medium. In these conditions, the changes of neurotransmitter release produced by compounds added to the superfusion medium (e.g. NPS) are due to their direct action on targets (for instance, NPS receptors) located on the releasing particles and indirect effects are minimized.

Effects of NPS on neurotransmitter release

The NPS-induced modulation of 5-HT and noradrenaline release observed in this study, together with the characteristics of our superfusion technique, make it legitimate to consider that NPS binds directly and with extremely high affinity to targets located on frontal cortex 5-hydroxytryptaminergic and noradrenergic nerve terminals/varicosities and that this binding leads to inhibition of the depolarization-evoked monoamine exocytosis. At present, we can only suggest that the effects of NPS on amine release are mediated by presynaptic NPS receptors, because selective receptor antagonists have not yet been available in our laboratory. On the other hand, NPS displayed binding in the subnanomolar range in experiments with a radioiodinated NPS analogue and activity in the low nanomolar range in a calcium mobilization test in HEK293 cells expressing NPS receptors (Xu et al., 2004; Roth et al., 2006; Camarda et al., 2008). More importantly, we used the NPS analogue [Ala2]NPS to compare its actions with those of the natural peptide at recombinant mouse NPS receptors expressed in HEK293 cells and at putative native receptors inhibiting 5-HT release from mouse frontal cortex synaptosomes. The same order of potency of agonists, that is, NPS >> [Ala2]NPS, has been obtained in the two series of experiments. On this basis, we propose that the mechanism by which NPS inhibits 5-HT release is the selective activation of presynaptic NPS receptors. This proposal, however, must be validated in the future by receptor antagonist studies. To conclude, inhibition of the depolarization-evoked 5-HT release in frontal cortex synaptosomes may represent a new functional test useful to develop ligands at native NPS receptors. Furthermore, the release test is likely to better reflect one function of NPS acting at receptors inserted in their physiological environment.

The biphasic effect of NPS on the depolarization-evoked release of noradrenaline cannot be easily explained at present. One possibility is the existence of subtypes of the NPS receptors with different affinities, which might either be coexpressed on the same noradrenergic terminals or be present on different subpopulations of noradrenergic nerve endings.

The finding that NPS caused inhibition of neurotransmitter release was unexpected, as activation of NPS receptors stably expressed in HEK293 cells has been reported to induce increases in intracellular calcium and cyclic AMP levels, suggesting that, in those cells, NPS receptors are coupled to Gq and Gs proteins respectively (Xu et al., 2004; Reinscheid et al., 2005).

However, the existence of ‘excitatory’ G protein-coupled receptors mediating inhibitory effects, including inhibition of transmitter release, has been reported. Inhibition of glutamate release from rat cerebellar synaptosomes (Marcoli et al., 2001) and cerebrocortical synaptosomes (Wang et al., 2006) mediated by 5-HT2A receptors coupled to the phosphatidylinositol pathway, as well as inhibition of the excitatory amino acid release from cerebrocortical synaptosomes through metabotropic glutamate receptors coupled to protein kinase C (Herrero et al., 1998) were in fact described. The theories put forward to explain the Gq-mediated calcium channel inhibition have recently been reviewed (Delmas et al., 2005).

The selectivity of NPS towards the exocytosis of 5-HT and noradrenaline is particularly impressive and deserves some comments. Such a selectivity implies that functional receptors for NPS able to mediate release modulation are almost exclusively expressed on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic and noradrenergic terminals or varicosities in frontal cortex. The release of glutamate and GABA, the transmitters released from the large majority of nerve terminals, was insensitive to NPS, suggesting that functional NPS receptors are poorly expressed on these nerve endings. Our finding appears to be in keeping with the morphological results of Xu et al. (2007) showing that NPS receptor signals were practically absent from frontal cortex. The receptors present on aminergic terminals would be too few to be detected morphologically, but enough to mediate effects on transmitter release. Of note, NPS receptor mRNA, although apparently absent from the locus coeruleus, is significantly expressed in raphe nuclei (Xu et al., 2007). The possibility that NPS receptors modulating glutamate/GABA release exist in other areas of the cerebral cortex or in other brain regions implicated in the behavioural effects of NPS and in which NPS receptors are expressed at higher density (i.e. the amygdala; Jungling et al., 2008; Meis et al., 2008) than in frontal cortex should be considered in future studies.

Functional implications

The mechanisms underlying the behavioural effects of NPS, particularly the arousal-promoting and the anxiolytic-like effects, remain poorly understood. Considering that classical neurotransmitters, such as noradrenaline, 5-HT, glutamate and GABA, play important roles in arousal systems and in the regulation of emotional states, including anxiety (Millan, 2003; Amiel and Mathew, 2007), the effects of NPS are likely to involve complex neurocircuitries and transmitter interactions.

Therefore, although the characteristics of our technical approach permit us to establish that release-inhibiting native NPS receptors exist on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic and noradrenergic terminals, the behavioural effects of NPS can only in part be related to the amine release inhibition here found to occur in the frontal cortex, while complex neuronal loops will certainly better explain the in vivo activities of NPS.

It is well known that 5-HT can mediate anxiety states (Handley, 1995; Murphy et al., 1999; Millan, 2003). As to the noradrenergic transmission, there is convincing evidence that the locus coeruleus-noradrenaline system is activated, with augmentation of noradrenaline release, by various stressors (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). In particular, release of noradrenaline induced by different stimuli from the coeruleo-cortical pathway, a circuit implicated in anxiety, was shown to facilitate anxiety-like behaviours (Bondi et al., 2007; Page et al., 2007). Accordingly, although it may be an oversimplified explanation, the inhibition of the evoked release of 5-HT and noradrenaline by NPS in frontal cortex could reflect the anxiolytic activity of the neuropeptide.

As to the arousal-promoting effect of NPS, straightforward and simple explanations based on the inhibition of noradrenaline release appear difficult, because noradrenaline is known to stimulate attention and behavioural arousal (see Jones, 2005). Looking for indirect mechanisms, an involvement of glutamate could be taken into account. Glutamate-containing neurones, including those of the diffuse thalamo-cortical relay, project to the frontal cortex and represent the backbone of the cortical-activating and behavioural-arousal systems in the brain (Jones, 2005). It is known that the activity of these glutamatergic neurones is regulated by various transmitters/modulators, including 5-HT and noradrenaline. Glutamate exocytosis from nerve terminals was reported to be inhibited by noradrenaline, acting at α2 adrenoceptors (Kamisaki et al., 1992; Delaney et al., 2007), and by 5-HT, acting at 5-HT1D receptors (Maura et al., 1998). In this scenario, inhibition of 5-HT/noradrenaline release by NPS would disinhibit glutamate release, thus promoting arousal.

To conclude, presynaptic regulation of neurotransmitter release might be useful to explain, at least in part, some of the behavioural effects of NPS; in fact, all the available information about the cellular mechanisms induced by NPS receptor activation has been obtained using cells expressing recombinant receptors; therefore, the present investigation is the first in vitro functional study of the neurochemical effects of NPS in brain tissue preparations bearing native receptors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian MIUR (PRIN 2006 Grant to LR, SS and to GC). The authors wish to thank Mrs Maura Agate for her expert editorial assistance.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- NPS

neuropeptide S

- [Ala2]NPS

[Alanine2]NPS

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Amiel JM, Mathew SJ. Glutamate and anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:278–283. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Elder NE, Henderson AN, Bertholomey ML, Dodge NC, Stewart RB. The effects of neuropeptide S on ethanol drinking and other related behaviors in alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1380–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B, Fernette B, Stricker-Krongrad A. Peptide S is a novel potent inhibitor of voluntary and fast-induced food intake in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi CO, Barrera G, Lapiz MD, Bedard T, Mahan A, Morilak DA. Noradrenergic facilitation of shock-probe defensive burying in lateral septum of rats, and modulation by chronic treatment with desipramine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:482–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarda V, Trapella C, Calò G, Guerrini R, Rizzi A, Ruzza C, et al. Synthesis and biological activity of human neuropeptide S analogues modified in position 2. J Med Chem. 2008;51:655–658. doi: 10.1021/jm701204n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Kallupi M, Cannella N, Braconi S, Stopponi S, Economidou D. Neuropeptide S system activation facilitates conditioned reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in the rat. 37th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, p. 271.18/Z1. [Google Scholar]

- Cline MA, Godlove DC, Nandar W, Bowden CN, Prall BC. Anorexigenic effects of central neuropeptide S involve the hypothalamus in chicks (Gallus gallus) Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;148:657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney AJ, Crane JW, Sah P. Noradrenaline modulates transmission at a central synapse by a presynaptic mechanism. Neuron. 2007;56:880–892. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Coste B, Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Phosphoinositide lipid second messengers: new paradigms for calcium channel modulation. Neuron. 2005;47:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley PR, Heath JW, Harrison SM, Jarvie PE, Glenfield PJ, Rostas JA. A rapid Percoll gradient procedure for isolation of synaptosomes directly from an S1 fraction: homogeneity and morphology of subcellular fractions. Brain Res. 1988;441:59–71. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley SL. 5-Hydroxytryptamine pathways in anxiety and its treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;66:103–148. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hascoet M, Bourin M. A new approach to the light/dark test procedure in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:645–653. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero I, Miras Portugal MT, Sánchez-Prieto J. Functional switch from facilitation to inhibition in the control of glutamate release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Biol Chem. 1998;273:1951–1958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. Arousal systems. Front Biosci. 2003;8:S438–S451. doi: 10.2741/1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE. From waking to sleeping: neuronal and chemical substrates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungling K, Seidenbecher T, Sosulina L, Lesting J, Sangha S, Clark SD, et al. Neuropeptide S-mediated control of fear expression and extinction: role of intercalated GABAergic neurons in the amygdala. Neuron. 2008;59:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisaki Y, Hamahashi T, Hamada T, Maeda K, Itoh T. Presynaptic inhibition by clonidine of neurotransmitter amino acid release in various brain regions. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;217:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90511-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard SK, Dwyer JM, Sukoff Rizzo SJ, Platt B, Logue SF, Neal SJ, et al. Pharmacology of neuropeptide S in mice: therapeutic relevance to anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:601–611. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoli M, Rosu C, Bonfanti A, Raiteri M, Maura G. Inhibitory presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptors regulate evoked glutamate release from rat cerebellar mossy fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:1106–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maura G, Marcoli M, Tortarolo M, Andrioli GC, Raiteri M. Glutamate release in human cerebral cortex and its modulation by 5-hydroxytryptamine acting at h5-HT1D receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:45–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis S, Bergado-Acosta JR, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Stork O, Munsch T. Identification of a neuropeptide S responsive circuitry shaping amygdala activity via the endopiriform nucleus. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. The neurobiology and control of anxious states. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:83–244. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B. Stress activation of glutamate neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex: implications for dopamine-associated psychiatric disorders. Biol Psych. 2002;51:775–787. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DL, Wichems C, Li Q, Heils A. Molecular manipulations as tools for enhancing our understanding of 5-HT neurotransmission. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Iga K, Shibata T, Shudo M, Kataoka K. Glial plasmalemmal vesicles: a subcellular fraction from rat hippocampal homogenate distinct from synaptosomes. Glia. 1993;9:48–56. doi: 10.1002/glia.440090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Reinscheid RK. Neuropeptide S: a novel modulator or stress and arousal. Stress. 2007;10:221–226. doi: 10.1080/10253890701248673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Oropeza VC, Sparks SE, Qian Y, Menko AS, Van Bockstaele EJ. Repeated cannabinoid administration increases indices of noradrenergic activity in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine TA, Jackman SL, Olmstead MC. Cocaine-induced anxiety: alleviation by diazepam, but not buspirone, dimenhydrinate or diphenhydramine. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:511–523. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri L, Luccini E, Romei C, Salvadori S. Neuropeptide S modulates neurotransmitter release from mouse frontal cortex nerve terminals. European Opioid Conference – European Neuropeptide Club joint meeting – Ferrara 2008: Ferrara, Italy, 2008; pp 50.

- Raiteri M. Functional pharmacology in human brain. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:162–193. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri L, Raiteri M. Synaptosomes still viable after 25 years of superfusion. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:1265–1274. doi: 10.1023/a:1007648229795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri L, Zappettini S, Milanese M, Fedele E, Raiteri M, Bonanno G. Mechanisms of glutamate release elicited in rat cerebrocortical nerve endings by ‘pathologically’ elevated extraterminal K+ concentrations. J Neurochem. 2007;103:952–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinscheid RK, Civelli O. The orphanin FQ/nociceptin knockout mouse: a behavioral model for stress responses. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:72–76. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinscheid RK, Xu YL, Okamura N, Zeng J, Chung S, Pai R, et al. Pharmacological characterization of human and murine neuropeptide S receptor variants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1338–1345. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi A, Vergura R, Marzola G, Ruzza C, Guerrini R, Salvatori S, et al. Neuropeptide S is a stimulatory anxiolytic agent: a behavioural study in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:471–479. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth AL, Marzola E, Rizzi A, Arduin M, Trapella C, Corti C, et al. Structure-activity studies on neuropeptide S. Identification of the amino acid residues crucial for receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20809–20816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KL, Patterson M, Dhillo WS, Patel SR, Semjonous NM, Gardiner JV, et al. Neuropeptide S stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and inhibits food intake. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3510–3518. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E. Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale G, Filaferro M, Ruggieri V, Pennella S, Frigeri C, Rizzi A, et al. Anxiolytic-like effect of neuropeptide S in the rat defensive burying. Peptides. 2008;29:2286–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S-J, Wang K-Y, Wang W-C, Sihra T. Unexpected inhibitory regulation of glutamate release from rat cerebrocortical nerve terminals by presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A receptors. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1528–1542. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YL, Reinscheid RK, Huitron-Resendiz S, Clark SD, Wang Z, Lin SH, et al. Neuropeptide S: a neuropeptide promoting arousal and anxiolytic-like effects. Neuron. 2004;43:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YL, Gall CM, Jackson VR, Civelli O, Reinscheid RK. Distribution of neuropeptide S receptor mRNA and neurochemical characteristics of neuropeptide S-expressing neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:84–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]