Abstract

Gluconate 5-dehydrogenase (Ga5DH) is an NADP(H)-dependent enzyme that catalyzes a reversible oxidoreduction reaction between d-gluconate and 5-keto-d-gluconate, thereby regulating the flux of this important carbon and energy source in bacteria. Despite the considerable amount of physiological and biochemical knowledge of Ga5DH, there is little physical or structural information available for this enzyme. To this end, we herein report the crystal structures of Ga5DH from pathogenic Streptococcus suis serotype 2 in both substrate-free and liganded (NADP+/d-gluconate/metal ion) quaternary complex forms at 2.0 Å resolution. Structural analysis reveals that Ga5DH adopts a protein fold similar to that found in members of the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family, while the enzyme itself represents a previously uncharacterized member of this family. In solution, Ga5DH exists as a tetramer that comprised four identical ∼29 kDa subunits. The catalytic site of Ga5DH shows considerable architectural similarity to that found in other enzymes of the SDR family, but the S. suis protein contains an additional residue (Arg104) that plays an important role in the binding and orientation of substrate. The quaternary complex structure provides the first clear crystallographic evidence for the role of a catalytically important serine residue and also reveals an amino acid tetrad RSYK that differs from the SYK triad found in the majority of SDR enzymes. Detailed analysis of the crystal structures reveals important contributions of Ca2+ ions to active site formation and of specific residues at the C-termini of subunits to tetramer assembly. Because Ga5DH is a potential target for therapy, our findings provide insight not only of catalytic mechanism, but also suggest a target of structure-based drug design.

Keywords: Streptococcus suis serotype 2, gluconate 5-dehydrogenase (Ga5DH), quaternary complex, SDR enzymes, catalytic mechanism

Introduction

Streptococcus suis (S. suis) serotype 2 (SS2) is an emerging pathogen with zoonotic importance causing diseases in pigs and humans, which have generated worldwide public concern.1,2 Potent bactericidal inhibitors will be required for effective treatment and prevention of S. suis infection in humans. One of the most common and effective avenues for therapeutic intervention in microbial infection is to inhibit metabolic pathways involved in energy generation within the microbial cell. d-gluconate is an important carbon and energy source for several species of bacteria (including S. suis), especially when these organisms enter the stationary phase of growth.3 d-gluconate also enables Escherichia coli to colonize the large intestine in murine models,4 thus demonstrating the role of this compound in both bacterial survival and pathogenicity. Enzymes for d-gluconate metabolism are found only in certain bacterial species, and consequently, these proteins are attractive targets for inhibition and drug therapy in the case of S. suis infections.

Gluconate 5-dehydrogenase (Ga5DH; EC 1.1.1.69), originally designated 5-keto-gluconate reductase,3 is a “switch enzyme” because of its capacity to catalyze a reversible oxidoreduction between d-gluconate and 5-keto-d-gluconate. When energy is exhausted, 5-keto-d-gluconate can be converted to d-gluconate by this enzyme and subsequently can enter the Entner-Doudoroff pathway to provide a source of carbon and NADP+.4 Under conditions of energy surplus, the enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of d-gluconate to 5-keto-d-gluconate as a transient means of energy storage.5 The reactions catalyzed by Ga5DH have been confirmed by HPLC and NMR analysis.6 The NADPH generated during the oxidation of d-gluconate may function as a hydrogen donor for biosynthetic processes, and it may also play a pivotal role in the defense of the organism against the oxidative attack by the infected host.7 To date, biochemical characteristics have been reported for Ga5DHs from several species including, Gluconobacter oxydans,5,8 Gluconobacter liquefaciens,9 and Acetobacter suboxydans.10 The enzyme belongs to the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family with a preference for NADP+ rather than NAD+ as cofactor.5 The crystal structure of Ga5DH in complex with NADP+ from Thermotoga maritima (PDB code 1VL8) has been solved, but the data have not yet been published. Consequently, no structural information for any Ga5DH is currently available to permit elucidation of the molecular architecture or clarification of the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme. Within the SDR family, the ternary complex structures with bound product or substrate analog and NAD(P)+ reveal a cofactor binding domain,11–13 Ser-Tyr-Lys catalytic triad, and a putative mechanism.14,15 Although the roles of tyrosine and lysine have been established, a functional assignment to the serine residue of this triad has proven elusive.

In this communication, we describe the first crystal structures of Ga5DH from S. suis in substrate-free and d-gluconate-NADP+-metal ion bound forms at 2.0 Å resolution. This molecular information has enabled us: (i) to define the catalytically active site of the enzyme, (ii) identify the determinants for cofactor and substrate recognition, and (iii) to propose a plausible structure-based mechanism for Ga5DH catalysis. Knowledge of the quaternary complex structure of Ga5DH offers an opportunity for structure-based design of specific enzyme inhibitors of S. suis in human infections.

Results

Quality and overall structure of substrate-free Ga5DH

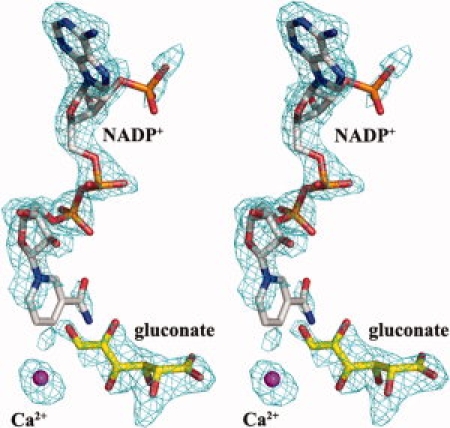

The substrate-free and y[NADP+-d-gluconate-metal ion] bound forms of Ga5DH crystallized in space group I222 and contained one subunit per asymmetric unit. Analyses of the final structures show the overall stereochemical statistics to be of high quality for these two forms. Both structures have over 90% of residues in the most favored orientation, and there are no residues in disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot. The final R factors for the substrate-free enzyme (Rwork = 0.19, Rfree = 0.21) and for the enzyme complex (Rwork = 0.19, Rfree = 0.22) are excellent values for structures at 2.0 Å resolution. In these two structures, the N-terminal 23 residues including the hexa-histidine tag and residues 208–213 were not visible in the electron density map and were excluded in the final models. In the complexed Ga5DH structure, residues for which density was not observed (200–207) were also excluded. The Fo − Fc electron density map for the ligands NADP+, Ca2+, and d-gluconate in the Ga5DH complex structure was shown in Figure 1. The Ga5DH structure containing one tightly bound NADP+, d-gluconate and Ca2+ atom was therefore designated a quaternary complex. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table I. Throughout this article, the numbering of amino acid residues corresponds to the S. suis Ga5DH

Figure 1.

Stereo view of the Fo − Fc electron density map calculated by FFT using the refined model excluding the substrate, NADP+ and Ca2+, contoured at 2.5 σ.

Table I.

Data Collection and Final Refined Model Statistics

| Substrate free-protein | Quaternary complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 | 1.5418 |

| Space group | I222 | I222 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 71.1, 75.6, 97.8 | 71.2, 75.3, 98.7 |

| α, β, γ (deg) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 30.56–1.90 (2.00–1.90) | 50.00–2.00 (2.07–2.00) |

| Observed reflections | 150,134 (14,810) | 161,839 (15,804) |

| Unique reflections | 19,757 (1937) | 18,339 (1783) |

| Multiplicitya | 7.6 (6.1) | 8.8 (9.0) |

| Overall completeness (%)a | 94.1 (74.7) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| Overall Rmerge (%)a | 0.047 (0.322) | 0.073 (0.293) |

| I/σ(I)a | 30.8 (4.2) | 54.8 (10.6) |

| Final model statistics | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 30.56–2.00 | 50.00–2.00 |

| No. of protein atoms | 1938 | 1884 |

| No. of water molecules | 130 | 210 |

| No. of other molecules | 1 NADP+ | |

| 1 d-gluconate | ||

| 1 Ca2+ | 1 Ca2+ | |

| Rworkb | 0.19 (0.22) | 0.19 (0.20) |

| Rfreec | 0.21 (0.27) | 0.22 (0.31) |

| RMS deviations | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.013 | 0.017 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 1.243 | 1.609 |

| Ramachandran plotd | ||

| Most favored regions (%) | 92.8 | 91.2 |

| Additional allowed regions (%) | 6.8 | 8.3 |

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Figures in parentheses refer to data in the highest resolution shell.

Rwork=Σ|Fo − Fc|/ΣFo for the 95% of the reflection data used in the refinement. Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree is the equivalent of Rwork, except that it was calculated for a randomly chosen 5% test set excluded from the refinement.

As calculated by PROCHECK.16

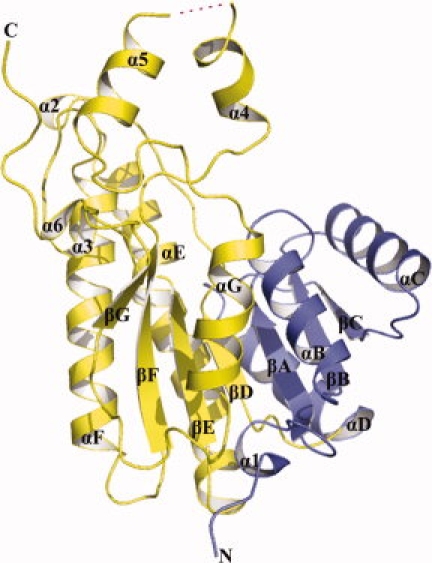

The structure of Ga5DH monomer is illustrated in 2. The overall fold is characteristic of an SDR enzyme and closely resembles that of T. maritima Ga5DH (PDB code 1VL8) with the root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d) for 251 α-carbons of 0.5 Å (Supp. Info. Fig. 1). The fold comprises two distinct domains: the N-terminal domain, responsible for NADP+ binding, and the C-terminal domain that harbors the catalytically important triad of residues Ser-Tyr-Lys. The active site cleft is formed at the junction of the two domains. The Ga5DH monomer comprises a seven-stranded parallel β-sheet (with C-B-A-D-E-F-G topological scheme) sandwiched by six α-helices, three on each side (αB, αC, and αD; and αE, αF, and αG), thereby creating the nucleotide-binding domain (Rossmann fold). Six short helices, α1, α2, α3, α4, α5, and α6, are separated from this main body of the subunit.

Figure 2.

Cartoon diagram of the Ga5DH subunit of S. suis. The N-terminus of the molecule is shown in blue, and the C-terminus in yellow. The nomenclature for secondary structural elements was adapted from Ghosh et al.17 The missing region is depicted by a dashed magenta line.

Oligomeric assembly and intersubunit contacts

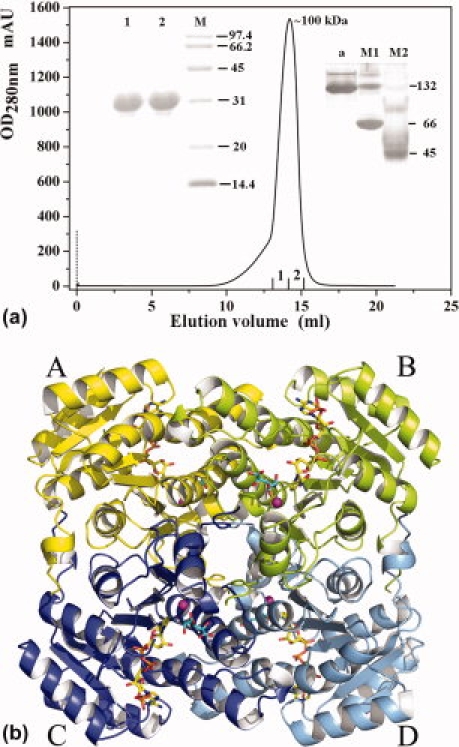

Structural analysis of the crystalline packing arrangement shows that Ga5DH exists as a homotetramer. The oligomeric state of Ga5DH was further investigated by analytical gel filtration, native-PAGE, and SDS-PAGE experiments [Fig.3(A)]. Analytical SDS-PAGE revealed a single protein band of Mr ∼ 29 kDa, whereas data from gel filtration and native-PAGE suggested an Mr for the protein of ∼100 and ∼132 kDa, respectively. These results provide evidence that the Ga5DH from S. suis functions as a homotetramer, in contrast with the dimeric homologous proteins from Thermotoga maritima and Gluconobacter oxydans.5 The tetrameric form of Ga5DH in the solution-state is consistent with that deduced from the solid-state crystal structure.

Figure 3.

(A) Stages in the purification of Ga5DH from S. suis. SDS-PAGE (left inset), nondenaturing PAGE (right inset), and gel filtration chromatograms. The numbering of SDS/PAGE sample is the same as that of the elution profile. In the nondenaturing PAGE diagram, Lane a, indicates the purified Ga5DH obtained by gel filtration; lane M1 and M2 indicate the molecular weight markers of nondenaturing PAGE (Sigma-Aldrich). (B) Tetramer of Ga5DH. The subunits A, B, C, and D are colored in yellow, lemon, blue, and light blue, respectively. Each subunit contains a ball-and-stick representation of NADP+ (yellow) and the substrate (cyan). Metal ions are shown as magenta spheres.

As noted earlier, the substrate-free Ga5DH subunits assemble to form a homotetramer in solution and, with three different intersubunit interfaces, the enzyme can be envisioned as a dimer of dimers [Fig. 3(B)]. During tetramer formation, the intersubunit interface buries ∼2500 Å2 of surface area between subunit A and B, ∼2800 Å2 between subunit A and C, and ∼1100 Å2 between subunit B and C, respectively. The stacking of phenylalanine residues, salt bridges, and hydrophobic interactions are found at the interfaces between subunit A and B [Supp. Info. Fig. 2(A)], whereas there are only two pairs of phenylalanine stacking between subunit A and C [Supp. Info. Fig. 2(B)]. Hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction are observed between subunit B and C [Supp. Info. Fig. 2(C)]. Direct interaction between these two subunits is rarely presented in the tetrameric SDR enzyme structure.14 Interestingly, residues in the C-termini participate in the interaction between subunits B and C and are thus of functional significance in tetramer assembly.

The quaternary complex structure and ligand binding sites

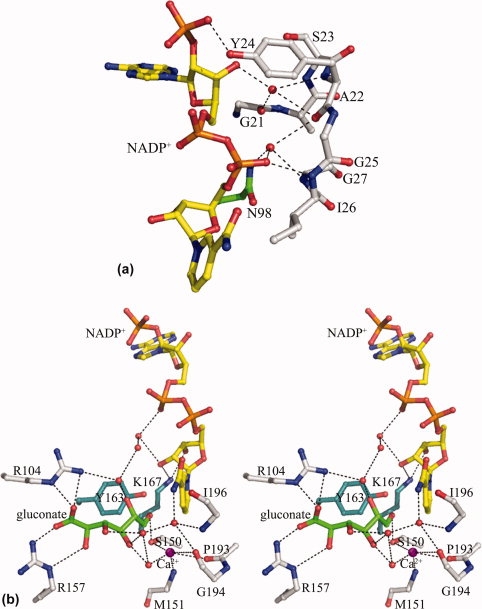

The overall structure of the Ga5DH complex is basically similar to that of its substrate-free form with a very low rmsd of 0.1 Å for 262 α-carbons. Like other NADP+-dependent enzymes of the SDR family,13,18 NADP+ molecules in the Ga5DH quaternary complex, bind in an extended conformation to residues forming the base of the active cleft between the two domains. As implicated in the structural description, hydrogen bonds are observed between NADP+ and the residues of the conserved nucleotide-binding motif GXXXGXG in SDR enzymes [Fig.4(A)]. It should be noted that the 2′-phosphate group of the adenine ribose forms hydrogen bond with the phenolic group of Tyr24. This represents an exception to the observation that basic amino acids close to the 2′-phosphate group determinate the preference of SDR enzymes for the nucleotide cofactor.19 No basic residue is found close to the expected position in our present structure, whereas in other NADP+-dependent SDR enzymes, there are two basic residues (Lys and Arg) close to the 2′-phosphate group in mouse lung carbonyl reductase (MLCR)13 and glucose dehydrogenase (GlcDH)19 and one in 1,3,8-trihydroxynaphthalene reductase (THNR).18

Figure 4.

Protein-ligand interaction. The NADP+ molecule is shown as yellow stick, and the substrate is displayed as green stick. Water molecules are shown as red spheres and metal ions as magenta spheres. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted black lines. (A) The interaction between NADP+ and nucleotide-binding motif GXXXGXG. Of note is that Tyr24, not a basic residue, forms hydrogen bond contact with 2′-phosphate group of the adenine ribose. (B) Stereo view of a detailed network of hydrogen bonds formed by Ga5DH and its ligands. The substrate and cofactor are fixed in a plausible position favorable for the subsequent dehydrogenation reaction. The catalytically important residues Tyr163 and Lys167 are shown as cyan stick.

The high Fo − Fc density peak (>6.6 σ) close to the substrate was assigned for metal ion (see Fig. 1). This metal was proved to be calcium by ICP-MS experiments, which indicated that the protein sample contained 0.003 mg/mL calcium, at least 10 to 20 times greater than other tested metals potentially involved in coordination (excepting Ni2+, about half of calcium concentration from Ni-NTA affinity purification). No extra Ca2+ was included in any of the solutions during protein purification or crystallization of Ga5DH, indicating that Ca2+ was co-purified with the enzyme, tightly binding to Ga5DH all the way. In the complex structure, Ca2+ coordinates with its surrounding atoms. Five possible coordinate atoms are located: (i) the main chain carbonyl oxygens of Gly194 (3.3 Å) and Pro193 (2.8 Å), (ii) the peptide bond nitrogen of Met151 (2.8 Å), (iii) the side chain oxygen of Ser150 (2.9 Å), and (iv) with one adjacent water molecule (2.9 Å). By coordination interaction, Ca2+ plays an important role in stabilizing the active site. In the meanwhile, the H-bond interaction between the coordinated water molecule of calcium ion and substrate suggests that Ca2+ in the S. suis Ga5DH complex structure functions in recognizing the substrate. These presumptions are compatible with the fact that the similar divalent cation Mn2+ can increase the specific activity of the G. oxydans Ga5DH.5

Because of the reversibility of the reaction catalyzed by Ga5DH, we could not preclude the fact that the bound “substrate” in the complex structure, presumably exists as a mixture of gluconate and partially converted product at the active site. Considering good density of the bound substrate in the Fo − Fc map (see Fig. 1) and structural similarity of substrate and product, we can still deduce a plausible mechanism based on the location of bound substrate in the complex structure. The substrate is in vicinity of the catalytically important residues Ser150 and Tyr163. Ser150 interacts with the axial C6 —OH moiety of d-gluconate, whereas the guanidino groups of Arg104 and Arg157 make hydrogen bond contact with the —OH group and form electrostatic interactions with the —C=O group of d-gluconate, respectively. The C5 hydroxyl group of d-gluconate interacts with the pyrophosphate moiety of NADP+ and the side chain of Arg104 through water-mediated hydrogen bonds. Indeed, Ile196, Gly194, and the Ca2+ ion form a sophisticated network of hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which may contribute to the retention and orientation of both the nicotinamide ring and d-gluconate substrate at the active site [Fig. 4(B)(B)].

Conformational changes induced by substrate binding

Stereo superimposition of the substrate-free form of Ga5DH with its quaternary complex, with a very low rmsd value, provide evidence for a high level of structural similarity in the two forms and suggest that the enzyme does not undergo major main-chain conformational changes upon binding and processing of substrate. In contrast to the structure of substrate-free Ga5DH, the helix α4 is not visible in the quaternary complex structure. Interestingly, the first residue Pro199 in the helix α4 is clearly defined and remains in the final complex structure. Pro199 may prevent the flexibility propagation of the missing region from the C-terminus to N-terminus because of its considerable steric hindrance, thereby enabling the enzyme to maintain a structurally stable active site.

Discussion

Comparison with other Ga5DHs

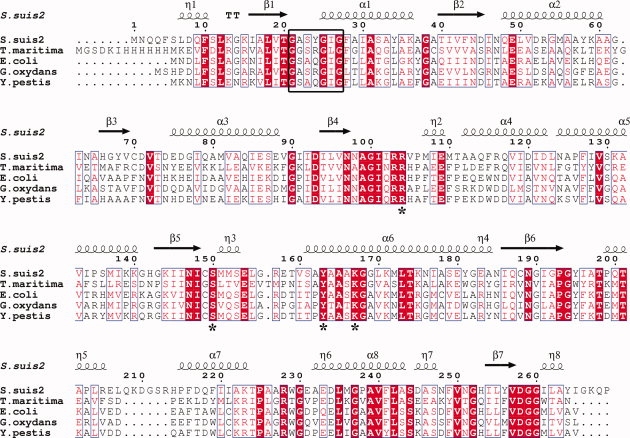

Ga5DH has been found in about 20 species of bacteria, and an amino acid sequence alignment of Ga5DH from S. suis with four representative species is shown in Figure 5. Sequence comparison of Ga5DH from S. suis with those from T. maritima, E. coli, G. oxydans, and Y. pestis reveals amino acid sequence identities of 33.1%, 41.2%, 40.5%, and 40.2%, respectively. Six more residues (208–213) are found around the α4-α5 loop region, corresponding to the density missing region described earlier. These Ga5DH proteins contain the two conserved motifs GXXXGXG and YXXXK that are characteristic of the SDR family of the enzymes. The catalytic residues Ser150, Tyr163, and Lys167 of the S. suis Ga5DH are highly conserved. Arginine residue 104 is present in all Ga5DHs, and Arg157 is also well conserved, except in the case of Ga5DH from T. maritima. The mutant protein obtained by site-directed mutagenesis (R104A) has <20% of the activity of the native Ga5DH (data not shown), suggesting that the positively charged Arg104 may facilitate access and orientation of the negatively charged substrate within the active site. Accordingly, we suggest that the S. suis Ga5DH adopts a catalytic tetrad Arg104-Ser150-Tyr163-Lys167, in contrast with the Ser-Tyr-Lys triad normally functional in SDR enzymes.

Figure 5.

Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of Ga5DH homologs. Illustrated are the sequences from Streptococcus suis type 2 (UYP_001198591U), Thermotoga maritima MSB8 (UTM0441U), Escherichia coli (UP39345U), Gluconobacter oxydans (UP50199U), and Yersinia pestis (UQ8ZDM3U). The most conserved residues in all Ga5DHs are shown in red, and NADP+ binding motifs (GXXXGXG) are boxed. The secondary structural elements of Ga5DH are shown above the sequences. The residues forming the proposed catalytic tetrad are marked by asterisks. Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW20 and the figure was produced with ESPript.21

Role(s) of the catalytic residues, NADP+ and Ca2+

The functions of the tyrosine and lysine residues in the catalytic triad Ser-Tyr-Lys of SDR enzymes have been established by chemical modification, sequence alignment, structure analyses, and site-directed mutagenesis experiments.22,23 However, due to a lack of direct structural knowledge, the role of serine in catalysis has been unclear. Inspection of our crystal structure shows the distance between the C5 —OH group of d-gluconate and Tyr163 to be ∼3.6 Å, and the hydroxyl group Tyr163 may well function as a general acid/base catalyst as reported previously.14,15,24 Additionally, the distance between the —OH group of Tyr163 and the side-chain amine of Lys167 is 4.4 Å, which makes a plausible argument for Lys167 induced reduction of the pKa of Tyr163 by electrostatic interaction.14,15 The side-chain amine of Lys167 also forms hydrogen bonds with the two —OH groups of ribose attached to the nicotinamide moiety of NADP+. Thus, the Lys167 residue has dual functions in stabilizing the position and orientation of the nicotinamide ring, and concomitantly lowering the pKa value of the —OH group of tyrosine to facilitate proton transfer.25 The residue Arg104 forms hydrogen bond contacts with the carboxyl oxygen of the substrate, whereas Ser150 forms a hydrogen bond contact (2.6 Å) with the hydroxyl group at C6 (rather than the C5 —OH) of the substrate. This latter finding contrasts with previous suggestions that the Ser and Tyr residues targeted the same axial carbon.13 The residues Arg104 and Ser150 are therefore important determinants in the recognition and binding of substrate. The orientation of the C5 of the substrate is toward the C4 of the nicotinamide ring, and the distance of 4.1 Å is favorable to the subsequent hydride transfer between them. The highly coordinated Ca2+ ion is in close proximity to the catalytically important residue Ser150, recognizing the substrate and stabilizing the active site. The metal ion may also participate in the abstraction of the proton from the C5 —OH of substrate and facilitate stabilization of the proposed ketone intermediate. Although speculative for Ga5DH, there is evidence to suggest a role of divalent metals in induced deprotonation in other enzyme catalyzed reactions. In a recent report of the novel mechanism of glycoside hydrolysis by an NAD+/Mn2+-dependent phospho-α-glucosidase, Rajan et al. suggested that Mn2+ (in hydroxide form) may effect the deprotonation and stabilize the keto formed by oxidation of the C3 —OH of the G6P moiety of the disaccharide phosphate substrate.26

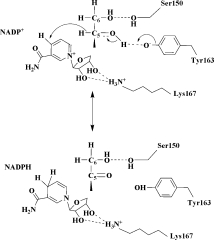

Proposed catalytic mechanism

The high-resolution crystal structure of the quaternary complex of Ga5DH from S. suis allows us to propose a catalytic mechanism for this enzyme, which differs from that suggested for other members of the SDR family. The conserved Arg104 and Ser150 make hydrogen bond interactions with two different —OH groups of d-gluconate and play an important role in substrate recognition. The residue Arg157 makes an electrostatic interaction with the —COOH group of the substrate, and by assistance from the metal ion and environmental water molecules, the substrate and cofactor are thus favorably positioned for the catalytic reaction to occur. Lys167 then lowers the pKa of the phenolic —OH of Tyr163 (via an electrostatic interaction), and the resultant deprotonated Tyr163 residue then forms a hydrogen bond with the C5 —OH of d-gluconate. The deprotonated Tyr163 functions as a catalytic base to extract a proton from the C5 —OH of d-gluconate. Concomitantly, NADP+ accepts a hydride ion transferred from position C5 of d-gluconate to C4 of the nicotinamide ring. The reaction is completed by the release of 5-keto-d-gluconate from the active site (see Fig. 6). Although our proposed mechanism bears similarity to that previously proposed,14 in this communication, we provide clear structural evidence for the role of serine and conclusive contribution of Arg104 in the catalytic process.

Figure 6.

Proposed reaction mechanism for Ga5DH from S. suis. Note that Ser150 forms a hydrogen bond with the —OH group at C6 (not C5) of the substrate. The mechanism is described in detail in Discussion.

Material and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of Ga5DH

The IdnO gene encoding Ga5DH was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA extracted from S. suis 05ZYH33 and cloned into NdeI/XhoI restriction sites of the expression vector pET28b(+) (Novagen). A Ga5DH fusion protein containing the N-terminal His6 tag was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells grown at 37°C in LB medium, and induced by addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-thio-β-d-galactoside. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, disrupted by sonication, and clarified by centrifugation. Ga5DH was purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Ni-NTA Agarose, Qiagen), followed by gel filtration (Superdex 200, Amersham Biosciences). The purified enzyme was concentrated to 15 mg/mL by Centricon filtration (Millipore). The mutant R104A was introduced into the IdnO gene by overlapping-PCR. The mutant protein was expressed and purified as described earlier for native Ga5DH. Protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE, and the molecular weight of Ga5DH was estimated by native-PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA assay (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol using bovine serum albumin as the standard. The enzyme kinetic assay of native and mutant Ga5DH was performed by a previously described procedure.27

Metal ion analysis

Qualitative and quantitative metal ion analyses were performed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the Analysis Center of Tsinghua University (Beijing, China).

Crystallization procedures

All crystallization experiments were carried out using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 291 K. The substrate-free Ga5DH crystals were obtained with a solution containing 0.1M Na citrate (pH 5.6), 30% (w/v) PEG 4000, and 0.5M NaCl. To obtain the crystal complex, 20 mM NADP+ and 20 mM d-gluconate sodium (Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich) were included in a reservoir solution containing 0.1M Na citrate (pH 5.6), 24% (wsol;v) PEG 4000, and 0.5M NaCl. Prior to data collection, crystals were transferred to a solution of the same composition supplemented with 15% (v/v) glycerol as cryoprotectant and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Data collection, processing, and structure determination

X-ray diffraction data were collected on R-axis image plate mounted on a Rigaku rotating anode. Data were processed and scaled with MOSFLM28 and SCALA.29 For the substrate-free enzyme data set, molecular replacement as implemented in MOLREP,30 was performed using the structure coordinates of the Ga5DH from Thermotoga maritima with the waters removed (PDB code 1VL8). Refinement was initiated with the program REFMAC5.31 This was followed by interactive rounds of manual fitting in COOT32 using weighted 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc electron density maps and further refinement in REFMAC5. Identification of potent sites of solvent molecules was performed by automatic water-picking algorithm of COOT. The final model from the substrate-free enzyme data set (described as earlier) with all water molecules removed was used as the initial model for the complexed enzyme. REFMAC5 was again used in conjunction with COOT to refine and build the crystal structure and to fit the complexed cofactor and substrate into the electron density. The figures were prepared by PyMOL33, unless otherwise noted.

Data deposition

The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession codes 3CXR (substrate-free Ga5DH) and 3CXT (Ga5DH quaternary complex).

Conclusions

Ga5DH from S. suis is a homotetrameric protein and may be included as a new member of the SDR family of enzymes. The quaternary complex structure reported here is the first to be described for an enzyme assigned to this family. Our high-resolution structures provide structural evidence for the catalytically important role of a serine residue in SDR enzymes and also substantiate the key role of Arg104 residues in substrate stabilization. Knowledge of the structure-based mechanism of the S. suis Ga5DH may facilitate the design of inhibitors against S. suis infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Analysis Center of Tsinghua University for their assistance with ICP-MS analyses, and they acknowledge Prof. Fan Jiang and Dr. Jianxun Qi of the Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for their assistance with data collection. They also thank Dr. David Cole for his review of our manuscript.

References

- 1.Tang J, Wang C, Feng Y, Yang W, Song H, Chen Z, Yu H, Pan X, Zhou X, Wang H, Wu B, Wang H, Zhao H, Lin Y, Yue J, Wu Z, He X, Gao F, Khan AH, Wang J, Zhao GP, Wang Y, Wang X, Chen Z, Gao GF. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLos Med. 2006;3:e151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lun ZR, Wang QP, Chen XG, Li AX, Zhu XQ. Streptococcus suis: an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:201–209. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi O, Shinagawa E, Matsushita K, Ameyama M. Crystallization and properties of 5-keto-d-gluconate reductase from Gluconobacter suboxydans. Agric Biol Chem. 1979;43:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweeney NJ, Laux DC, Cohen PS. Escherichia coli F-18 and E. coli K-12 eda mutants do not colonize the streptomycin-treated mouse large intestine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3504–3511. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3504-3511.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klasen R, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Biochemical characterization and sequence analysis of the gluconate: NADP 5-oxidoreductase gene from Gluconobacter oxydans. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2637–2643. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2637-2643.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bausch C, Peekhaus N, Utz C, Blais T, Murray E, Lowary T, Conway T. Sequence analysis of the GntII (subsidiary) system for gluconate metabolism reveals a novel pathway for l-idonic acid catabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3704–3710. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3704-3710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delarue M, Duclert-Savatier N, Miclet E, Haouz A, Giganti D, Ouazzani J, Lopez P, Nilges M, Stoven V. Three dimensional structure and implications for the catalytic mechanism of 6-phosphogluconolactonase from Trypanosoma brucei. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:868–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merfort M, Herrmann U, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. High-yield 5-keto-d-gluconic acid formation is mediated by soluble and membrane-bound gluconate-5-dehydrogenases of Gluconobacter oxydans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;73:443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameyama M, Chiyonobu T, Adachi O. Purification and properties of 5-ketogluconate reductase from Gluconobacter liquefaciens. Agric Biol Chem. 1974;38:1377–1382. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galante E, Lanzani GA, Sequi P. Variations of 2-ketogluconate and 5-ketogluconate oxidoreductases during growth in Acetobacter suboxydans. Enzymologia. 1966;30:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka N, Nonaka T, Nakanishi M, Deyashiki Y, Hara A. Crystallization of mouse lung carbonyl reductase complexed with NADPH and analysis of symmetry of its tetrameric molecule. J Biochem. 1995;118:871–873. doi: 10.1093/jb/118.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett MJ, Schlegel BP, Jez JM, Penning TM, Lewis M. Structure of 3α-hydroxysteroid/dihydrodiol dehydrogenase complexed with NADP+ Biochemistry. 1996;35:10702–10711. doi: 10.1021/bi9604688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka N, Nonaka T, Nakanishi M, Deyashiki Y, Hara A, Mitsui Y. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of mouse lung carbonyl reductase at 1.8 Å resolution: the structural origin of coenzyme specificity in the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. Structure. 1996;4:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka N, Nonaka T, Tanabe T, Yoshimoto T, Tsuru D, Mitsui Y. Crystal structures of the binary and ternary complexes of 7 α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7715–7730. doi: 10.1021/bi951904d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamashita A, Kato H, Wakatsuki S, Tomizaki T, Nakatsu T, Nakajima K, Hashimoto T, Yamada Y, Oda J. Structure of tropinone reductase-II complexed with NADP+ and pseudotropine at 1.9 Å resolution: implication for stereospecific substrate binding and catalysis. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7630–7637. doi: 10.1021/bi9825044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thorton JM. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh D, Weeks CM, Grochulski P, Duax WL, Erman M, Rimsay RL, Orr JC. Three-dimensional structure of holo 3α, 20β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: a member of a short-chain dehydrogenase family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10064–10068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson A, Jordan D, Schneider G, Lindqvist Y. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of 1,3,8-trihydroxynaphthalene reductase from Magnaporthe grisea with NADPH and an active-site inhibitor. Structure. 1996;4:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasutake Y, Nishiya Y, Tamura N, Tamura T. Structural insights into unique substrate selectivity of Thermoplasma acidophilumd-aldohexose dehydrogenase. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1034–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jörnvall H, Persson B, Krook M, Atrian S, Gonzalez-Duarte R, Jeffery J, Ghosh D. Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) Biochemistry. 1995;34:6003–6013. doi: 10.1021/bi00018a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oppermann UC, Filling C, Berndt KD, Persson B, Benach J, Ladenstein R, Jörnvall H. Active site directed mutagenesis of 3β/17 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase establishes differential effects on short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase reactions. Biochemistry. 1997;36:34–40. doi: 10.1021/bi961803v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Jiang JC, Lin ZG, Lee WR, Baker ME, Chang SH. Site-specific mutagenesis of Drosophila alcohol dehydrogenase: evidence for involvement of tyrosine-152 and lysine-156 in catalysis. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3342–3346. doi: 10.1021/bi00064a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang CC, Chang YH, Hsu CN, Hsu HH, Li CW, Pon HI. Mechanistic roles of Ser-114, Tyr-155, and Lys-159 in 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/carbonyl reductase from Comamonas testosteroni. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3522–3528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajan SS, Yang X, Collart F, Yip VL, Withers SG, Varrot A, Thompson J, Davies GJ, Anderson WF. Novel catalytic mechanism of glycoside hydrolysis based on the structure of an NAD+/Mn2+-dependent phospho-α-glucosidase from Bacillus subtilis. Structure. 2004;12:1619–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsushita K, Shinagawa E, Ameyama M. d-Gluconate dehydrogenase from bacteria, 2-keto-d-gluconate-yielding, membrane-bound. Methods Enzymol. 1982;89(Part D):187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)89033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter. Protein Crystallogr. 1992;26:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans PR. Scala, CCP4/ESF-EACBM Newsletter. Protein Crystallogr. 1997;33:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeLano WL. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Palo Alto, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]