Abstract

The human ether-a-go-go related gene (HERG) constitutes the pore forming subunit of IKr, a K+ current involved in repolarization of the cardiac action potential. While mutations in HERG predispose patients to cardiac arrhythmias (Long QT syndrome; LQTS), altered function of HERG regulators are undoubtedly LQTS risk factors. We have combined RNA interference with behavioral screening in Caenorhabditis elegans to detect genes that influence function of the HERG homolog, UNC-103. One such gene encodes the worm ortholog of the rho-GTPase activating protein 6 (ARHGAP6). In addition to its GAP function, ARHGAP6 induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and activates phospholipase C (PLC). Here we show that IKr recorded in cells co-expressing HERG and ARHGAP6 was decreased by 43% compared to HERG alone. Biochemical measurements of cell-surface associated HERG revealed that ARHGAP6 reduced membrane expression of HERG by 35%, which correlates well with the reduction in current. In an atrial myocyte cell line, suppression of endogenous ARHGAP6 by virally transduced shRNA led to a 53 % enhancement of IKr. ARHGAP6 effects were maintained when we introduced a dominant negative rho-GTPase, or ARHGAP6 devoid of rhoGAP function, indicating ARHGAP6 regulation of HERG is independent of rho activation. However, ARHGAP6 lost effectiveness when PLC was inhibited. We further determined that ARHGAP6 effects are mediated by a consensus SH3 binding domain within the C-terminus of HERG, although stable ARHGAP6-HERG complexes were not observed. These data link a rhoGAP-activated PLC pathway to HERG membrane expression and implicate this family of proteins as candidate genes in disorders involving HERG.

Keywords: arrhythmia, Long QT Syndrome, rho GAP, HERG, potassium current, ion channel, protein trafficking

Introduction

The human ether-a-go-go related gene (HERG) is a potassium (K+) channel that is expressed in multiple tissues (1) and mediates diverse physiologic functions (2-4). In the heart, ERG comprises the pore forming subunit of IKr, a K+ current involved in repolarization of the cardiac action potential. Excessive reduction of IKr due to loss-of-function mutations in HERG, or a constellation of genetic and acquired conditions that down-regulate IKr, can result in prolonged cardiac repolarization and often fatal arrhythmias, a condition known as the long QT syndrome (LQTS) (5;6). The LQTS exists in two forms, congenital and acquired, the latter precipitated by cofactors such as exposure to HERG-blocking drugs, and electrolyte abnormalities (7;8). Multiple proteins have been shown to modulate ERG function in heterologous expression systems (9-16), and some of these proteins have been shown to carry polymorphisms in patients who exhibit acquired forms of the LQTS (9;13).

We have previously shown that the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is well-suited for genetic screening of candidate HERG regulators, by taking advantage of the double-stranded interfering RNA (RNAi), available for most of the C. elegans genes, which can be conveniently fed to worms (13). C. elegans possesses a single ortholog of HERG, UNC-103, which shares 70% amino acid identity with mammalian ERG in the transmembrane and pore domains; the overall homology is 39 % identity, and 44 % similarity at the amino acid level. The dominant unc-103(n500) mutant strain behaves as a gain-of-function mutation in the gene. unc-103(n500) worms exhibit a multitude of defects, including an egg-laying defect, which results in the retention of unlaid eggs (13;17-19). These defects are consistent with hypoexcitability, which may result from an inappropriately activated hyperpolarizing channel. unc-103(n500) contains an alanine to threonine mutation in the S6 pore-lining region of the channel. The analogous mutation in HERG results in profound changes in gating resulting in increased hyperpolarizing current at negative membrane potentials (13).

Screening an RNAi library of C. elegans chromosome 1 for cDNAs that modulate UNC-103-dependent egg laying behavior revealed C01F4.2, the worm homolog to the human GTPase-activating protein 6 (ARHGAP6). ARHGAP6 is a rho GTPase activating protein (rhoGAP), with a “rhoGAP-like” domain, and three proline-rich motifs with consensus SH3-binding sites (20). ARHGAP6 is expressed in multiple human tissues, including the heart (21). rhoGAPs are crucial in cell cytoskeletal organization, growth, differentiation, neuronal development and synaptic functions (22). While ARHGAP6 was initially characterized for its rhoGAP function, non-enzymatic functions for ARHGAP6 have been identified, including activity as a cytoskeletal protein to promote actin remodelling (20). More recently, ARHGAP6 has been shown to enhance PLC activity in a mammalian overexpression system and to co-immunoprecipitate with PLC-δ1 in extracts of transfected Cos-7 cells (23).

Since treatment of unc-103(n500) worms with C01F4.2 RNAi suggested a possible functional interaction between these two proteins, we wanted to determine whether ARHGAP6 is a HERG modulator, and studied its effects on HERG current in transfected cells, as well as in an atrial myocyte-derived cell line (HL-1) (24) and by biochemical quantification of HERG at the cell surface. We demonstrate that ARHGAP6 expression reduces HERG current in two heterologous systems, as well as in myocytes by decreasing the number of channels at the membrane in response to PLC activation. We show that this regulation is GAP-activity independent, and requires a presumptive consensus HERG SH3 binding domain but does not involve a stable ARHGAP-HERG complex.

Materials and Methods

C. elegans egg-laying assays and RNAi screen

For egg laying assays, worms were staged by picking L4 worms to a separate plate and using them for assays 24 hours later. 10 staged worms were picked to a food plate and the total number of eggs counted at 3 hours.

We obtained a commercially available library of RNAi feeding strains targeting C. elegans chromosome I (∼2,400 clones) (25) from MRCgenservice (Cambridge, UK). Individual RNAi clones were grown overnight at 37° C in 1 ml LBroth + 50 μg/ml ampicillin. 45 μls of each culture were plated onto individual wells of 24-well NGM media containing 25 μg/ml carbenicillin and 1 mM IPTG (to induce RNAi expression) and allowed to dry for 2 – 3 days at room temperature. 2-3 unc-103(n500) hermaphrodites (P0) containing unlaid eggs were picked to individual RNAi-seeded wells. The adult F1 progeny were assayed at 48 and 72 hours (hrs). Suppression of the egg-laying defect after RNAi treatment was scored by visually scanning individual wells for eggs under a microscope. Because the egg-laying defect of unc-103(n500) is absolute (Figure 1A), the presence of even a single egg in the presence of RNAi treatment was considered a positive response. Each RNAi construct that resulted in a positive response was repeated in two additional assays and if both times eggs were produced, the RNAi clone was deemed a candidate UNC-103-interacting gene.

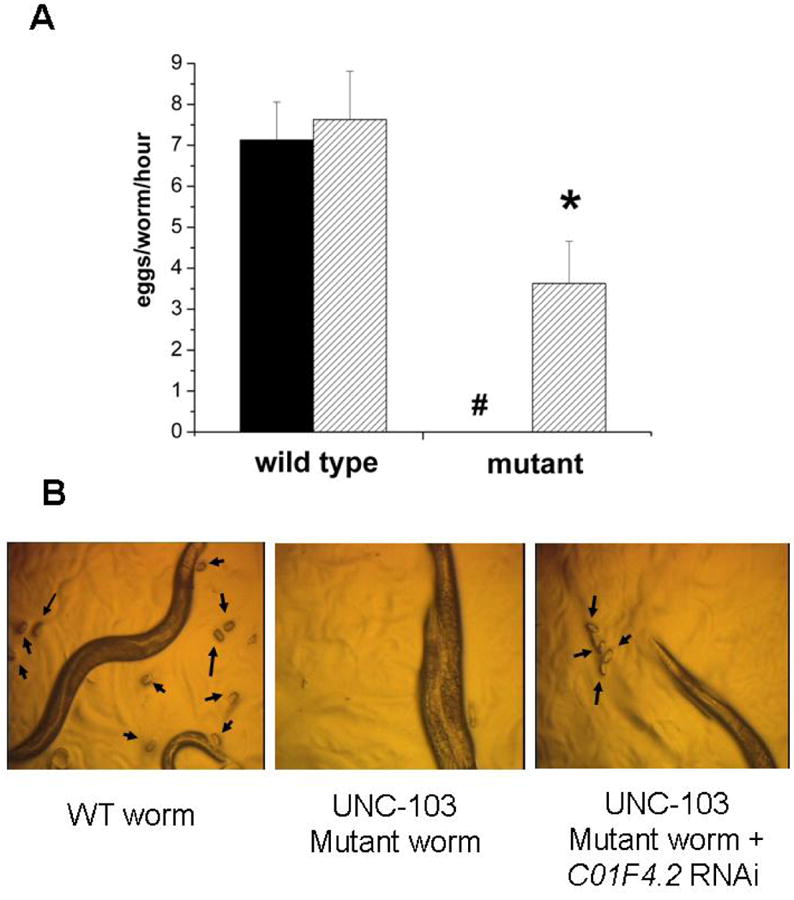

Figure 1. unc-103(n500) egg laying defect is rescued by unc-103 RNAi and partially rescued by the worm ortholog of ARHGAP6 RNAi.

A. WT and mutant (unc103(n500)) worm strains were exposed to unc-103 RNAi and egg-laying was assessed after 3 hrs. WT worms laid 7.13 +/- 0.93 (s.e.m) and 7.63 +/- 1.18 eggs on plates seeded with RNAi directed against GFP (solid fill) and unc-103 (hatched fill). unc-103(n500) worms (mutant) laid no eggs on RNAi directed against GFP, but 3.63 + 1.03 eggs on UNC-103 RNAi containing plates (n = 3). #, P <0.05 mutant compared to WT; * P<0.05 comparing solid and hatched bars in unc103(n500) worms. B. Worms observed in a dissecting microscope for the presence of eggs: left, WT worms, arrows point to eggs. Center, unc-103(n500) worms; eggs are not observed. Right, unc-103(n500) worms in presence of C01F4.2 RNAi; the presence of eggs demonstrate the partial rescue of the egg-laying defect.

cDNA constructs and transfections

The HERG cDNA was subcloned into pSI (Promega, Madison, WI) as described previously (26). HERG1093-1096A was constructed within the same vector background as WT HERG using recombinant PCR approaches, replacing residues 1093-1096 with alanines (A). Whenever HERG cDNA alone was to be tested, we cotransfected the GFP-IRES plasmid (27) as a fluorescent marker of transfected cells and to keep the total amount of transfected DNA constant. ARHGAP6 and ARHGAP6R433G are fused with EGFP on the pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) backbone (20). Amino acid changes were validated by sequencing. Human rhoA(N19) was a kind gift from Dr. Neil Bhowmick (Vanderbilt University) and was originally described by Coso et al (28). Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO-K1) cells were transfected with FuGENE (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

small hairpin (sh) RNA treatment of atrial tumor myocytes (HL-1)

HL-1 cells were obtained from Dr. William Claycomb (24). shRNAs with a 19 base pair stem and a 9 base pair loop structure were designed against a unique region of mouse ARHGAP6 and subcloned into the pSIF-H1-copGFP vector (SBI, Mountain View, CA). The sequence of the shRNA insert is: 5′ GATCCCCGAATGCCCTTATCCCAAGTTTCAA GAGAACTTGGGATAAGGGCATTC TTTTTGG -3′ where the stem region is indicated in bold letters and the nucleotides that are part of the terminal restriction enzyme binding sites (Bam HI and Eco RI) are shown in italics. The sequence of the scrambled, negative control shRNA is 5′ GATCCCCTGCGAACCTATTCCAAGCTTTCAAGAGA AGCTTGGAATA GGTTCGCATTTTTGG-3′. The final constructs were cotransfected into HEK293FT cells with the required viral packaging plasmids that encode viral structural proteins, as well as the required polymerase (pFIV-34N and pVSV-G) using Fugene6. After 72 hrs of incubation, the virus-containing media were removed and centrifuged through Centricon plus-20 columns (Millipore, MWCO 30,000) to remove cellular debris and to concentrate the virus. Pseudoviral particles were infected into HL-1 cells that we assessed for current levels on days 8 and 9 post infection. In order to establish effectiveness of the shRNA, ARHGAP6 was subcloned into vector p3×FLAG-CMV 7.1 (Sigma) creating an N-terminal fusion with a triple FLAG-tag and co-transfected with the shRNA or the scrambled shRNA vector into CHO cells. Whole cell extracts were prepared two days post transfection and analyzed on Western blots on SDS-PAGE (4-12% gradient).

Electrophysiology

Green fluorescent cells were chosen for analysis, and HERG currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch clamp technique as described previously (29) using glass pipettes of 2-5 MΩ resistance. The standard intracellular (pipette) solution contained (in mmol/L): 110 KCl, 10 HEPES, 5 K4BAPTA, 5 K2ATP, 1 MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH to yield a final intracellular K+ concentration of 145. The extracellular (bath) solution contained (in mmol/L): 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 2 CaCl2, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Patch-clamp measurements were performed at room temperature (RT) and are presented as the means ± SE. Statistical significance of the observed effects was assessed by means of the paired t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. To achieve PLC inhibition, we added U-73122 or the inactive compound, U-73343, to a final concentration of 1 μM to the bath solution. Every 90 minutes (min), the bath solution was exchanged.

Chemiluminescent measurements of surface HERG

To quantify the effects of ARHGAP6 on plasma membrane expression of HERG, we developed an antibody-linked chemiluminescent assay. CHO cells growing in P60 dishes were co-transfected with HERG plus GFP, HERG plus ARHGAP6, or HERG1093-1096A plus ARHGAP6 (1.5 μgs of each cDNA). Each transfection included 2 μgs of a plasmid encoding luciferase (pGL3-Promoter vector, Promega) to normalize for variability in transfection efficiency and cell viability. 24 hrs post transfection, the cultures were split into 3 wells of a 96-well flat bottom plate (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) at a density of 20, 000 cells per well. 2 hrs later, the wells were pre-incubated in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) with 10% non-fat, dry milk (NFDM) for one hr at room temperature. The first set of wells was incubated with anti-HERG antibody directed against an extracellular epitope (the AFLLKETEEGPPATEC peptide, corresponding to residues 430-445 of HERG within the S1-S2 linker; 1:25 dilution, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) in PBS plus 10% NFDM for one hr at room temperature. The second set of wells was processed in the same way but received no primary antibody as a control for background signal, which was later subtracted. After incubation with primary antibody (or mock-incubation), cells were washed with PBS three times and then incubated with an anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked secondary antibody (1:5,000; Amersham Biosciences) (or mock-incubated) for one hour at room temperature, followed by three washes with PBS. HRP activity was revealed in sets 1 and 2 by adding the Western Lightning Chemo-luminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Set 3 received neither primary nor secondary antibody, but was processed in parallel to measure luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HRP chemoluminescence and luciferase activity were measured in a Packard Luminocount (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, model BL 1000). To normalize for luciferase activity, a ratio of HRP luminescence divided by the luciferase activity is presented in figure 8. All assays were performed in triplicate.

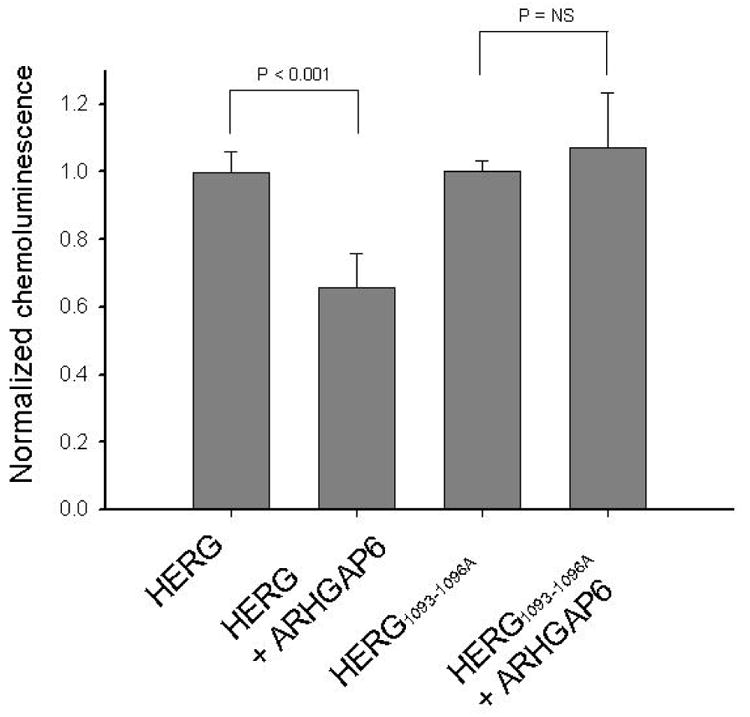

Figure 8. Reduction in surface expression of an extracellular HERG epitope following ARHGAP6 treatment measured by chemiluminescence.

Equal numbers of CHO cells were transfected with HERG plus GFP, HERG plus ARGHAP6, HERG1093-1096A plus GFP, or HERG1093-1096A plus ARHGAP6 (1.5 μg of each cDNA per well). Each transfection included luciferase cDNA as an internal control for transfection efficiency. 24 hrs post transfection, plates were split into 3 separate wells and processed in parallel to receive either primary (anti-HERG) plus secondary (HRP-linked) antibody, secondary antibody only, or to be tested for luciferase activity. Normalized chemoluminescence (chemiluminescence divided by luciferase activity) was 0.99 ± 0.03 in the absence, and 0.65 ± 0.1 in the presence of ARHGAP6 (n = 7; P < 0.001). In contrast, normalized chemoluminescence for HERG1093-1096A was 1 ± 0.03 in the absence and 1.07 ± 0.16 in the presence of ARHGAP6 (n = 7; P = NS).

Microscopy

HERG-expressing HEK cells were transfected with ARHGAP6-GFP or a plasmid expressing the GFP alone as before, grown in culture overnight and then fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Phalloidin-Alexa647 for 30 min according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Images were acquired using a Zeiss Inverted LSM510 Confocal Microscope cells in laser scanning fluorescence and DIC (Nomarski) modes; laser excitation was at 488nm for green fluorescence and 633nm for far-red phalloidin staining. Objective was 40×/1.30 Plan-NEOFLUAR OIL.

Results

Identification of a rhoGAP protein as an ERG regulator in C. elegans

To identify novel protein partners that modulate HERG, we utilized the C. elegans HERG homolog UNC-103 (for an amino acid alignment, see supplementary Figure 1A) in an unbiased, in vivo genetic screen. A mutant strain, unc-103(n500), with a mutation (A334T) in a residue conserved in HERG and UNC-103, exhibits profound neuromuscular defects in locomotion, pharyngeal pumping, defecation, male spicule contraction and egg-laying (13;17-19). The egg-laying behavior of WT worms was not altered compared to control when treated with unc-103 RNAi (compare black and hatched bars for WT worms in Figure 1A). Under the same conditions, untreated unc-103(n500) worms or unc-103(n500) treated with control (GFP) RNAi never produced eggs. In contrast, RNAi directed against UNC-103 rescued the egg-laying defect (Figure 1A). Since treatment with unc-103 RNAi ameliorated the unc-103(n500) phenotype, we hypothesized that down-regulation of proteins that functionally enhance UNC-103 activity using RNAi treatment would also improve the unc-103(n500) phenotype (13). This allowed us to use egg-laying as a screen for interacting proteins in a high-throughput format.

We acquired a commercially available inhibitory double-stranded RNA (RNAi) library directed against genes on chromosome 1 to identify targets that rescue the egg-laying defect of unc-103(n500) worms in vivo. Bacterial cultures harboring individual RNAi clones were plated on multi-well plates and seeded with unc-103(n500) worms. Wells were visually scored for the presence of eggs at 48 and 72 hours. Any RNAi condition that repeatedly (3 times) resulted in eggs was scored as a positive. This approach identified C01F4.2, the worm homolog of the human ARHGAP6 (for an alignment, see supplementary Figure 1B) as a candidate modulator of UNC-103 activity.

Human ARHGAP6 down-regulates HERG K+ current

To determine whether the interaction between C01F4.2 and UNC-103 in worms correlates with a functional interaction between the homologous human proteins, HERG current was measured in the presence or absence of ARHGAP6 co-expression. Whole-cell HERG current magnitude decreased in the presence of ARHGAP6, as shown in Figure 2. On average, the peak tail current amplitude measured at -50 mV after a depolarization step to +40 mV was decreased by 43 % when ARHGAP6 was co-transfected. The voltage dependence of activation (Figure 2D) and steady-state inactivation (Figure 2E) were not affected. Deactivation kinetics of tail currents and inactivation kinetics were also not modified by the expression of ARHGAP6 (data not shown). To test whether the ARHGAP6 effects are selective for HERG, we similarly expressed the KCNQ1 K+ channel in the presence or absence of ARHGAP6. The results show that IKCNQ1 is not sensitive to ARHGAP6 expression in CHO cells (supplementary Figure 2), indicating that ARHGAP6 is selective for HERG over KCNQ1.

Figure 2. ARHGAP6 overexpression decreases HERG current in CHO cells.

A. Representative current traces from cells transfected with HERG plus EGFP (left) and HERG plus ARHGAP6 (right) (1.5 μg cDNA each). Cells were held at -80 mV, and then stepped to test potentials between -70 and +60 mV in 10 mV increments for 2 sec before repolarizing to -50 mV. B. Activating current-voltage (I-V) relationship recorded in cells expressing HERG alone or with ARHGAP6. C. I-V relation of the tail currents recorded at -50 mV in the absence and presence of ARHGAP6. On average, the peak tail current amplitude measured following depolarization to +40 mV was 27.7 ± 2.6 pA/pF in the absence, and 15.8 ± 1.4 pA/pF in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P < 0.001). D. The activation curve was fitted to a Boltzmann function (solid lines) of the form: I=1/[1+exp-((Vt-V1/2)/δ)], where V1/2 is the half-activation potential and δ is the slope factor. The V1/2 for activation was 3.9 ± 2.9 mV in the absence, and 7.0 ± 2.7 mV in the presence of ARHGAP6 [P = not significant (NS)]. The slope factor (δ) was 7.8 ± 0.3 in the absence and 7.9 ± 0.5 in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS). B-D: (○; n = 13) (▲; n = 13). E. The inactivation curve was fitted to a Boltzmann function (solid lines) of the form: I=Imax/[1+exp-((Vt-V1/2)/δ)]. δ = -28.8 ± 1.2 in the absence and δ = -28.7 ± 1 in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS). Imax was 1.2 ± 0.02 in both conditions (P = NS). The V1/2 for inactivation was -77.9 ± 3.3 mV in the absence, and -81.1 ± 2.5 mV in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS); (○; n = 13) (▲; n = 12).

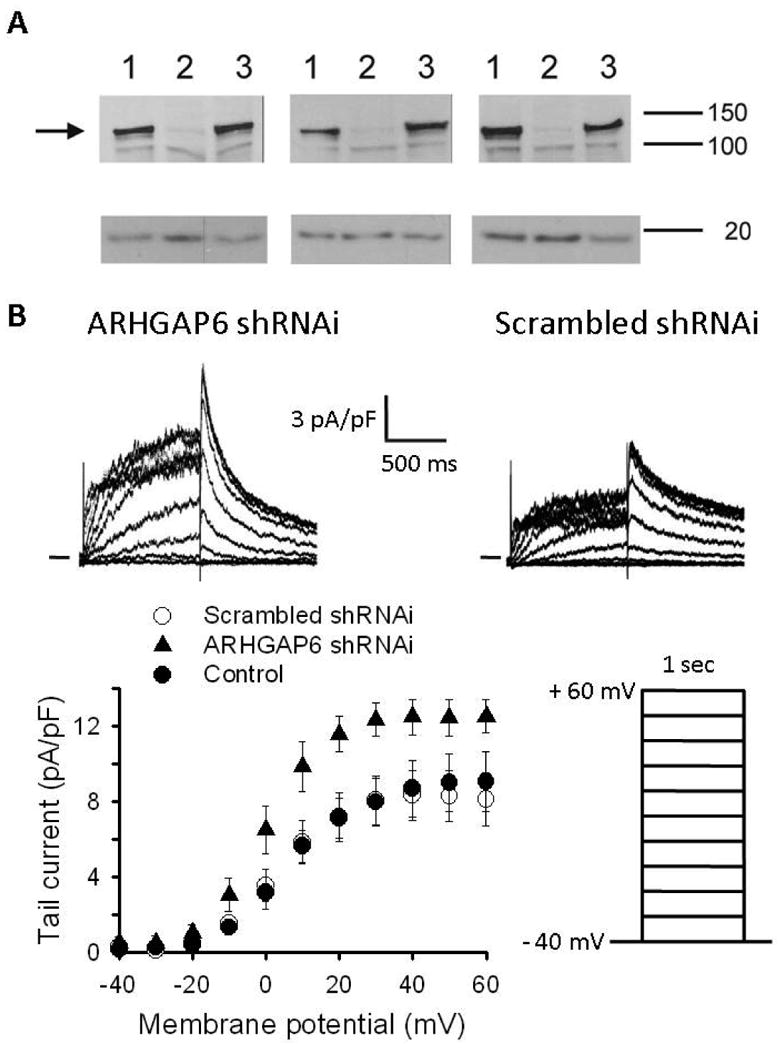

ARHGAP6 RNA has been detected in all tissues tested, including the heart (21). To determine whether ARHGAP6 influences endogenous IKr in cardiac myocytes, we took advantage of the mouse atrial tumor cell line, HL-1 (24) where we detected ARHGAP6 expression at the protein and RNA levels (data not shown). HL-1 cells maintain a differentiated cardiac phenotype in culture that includes contractility. They are atrial in origin, and contain many of the endogenous currents found in cardiac myocytes including IKr (30). Previous studies have shown that the time-dependent outward currents and tail currents recorded at -40 or -50 mV are sensitive to low-nanomolar concentrations of dofetilide, a characteristic of IKr (24;29). To manipulate expression levels of ARHGAP6 in this cell line, we chose to use RNA knockdown by inhibitory shRNAs using a lentiviral delivery system. To this end, we designed an shRNA targeting ARHGAP6, as well as a negative control, “scrambled” shRNA of the same size and nucleotide composition but in random order. The pSIH-H1-copGFP vector also transduces the copepod GFP gene, allowing us to monitor infection efficiencies by fluorescent microscopy. The virally transduced vector integrates into genomic DNA where it stably expresses the shRNA sequence. Since the transduction efficiency of HL-1 cells was not very high (less than 10% of the cell population), we were unable to validate the efficiency of the knockdown of endogenous ARHGAP6 protein directly. We therefore assessed the effectiveness of the shRNA by cotransfecting the shRNA vector with an ARHGAP6 cDNA into CHO cells. Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts (Figure 3A) shows ARHGAP6 migrating at its expected molecular mass (105 kDa, arrow) in sham treated and scrambled shRNA-treated cells (lanes 1 and 3) but not in shRNA treated cells (lanes 2) indicating that the specific shRNA caused a significant reduction of ARHGAP6 expression. The same results were observed when the blot was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody (data not shown). The lentiviral shRNA particles were infected into HL-1 cells and IKr was recorded on days 8 and 9 when expression of the green-fluorescent marker associated with shRNA expression was strongest. The results showed that cardiac myocytes treated with inhibitory shRNA targeting endogenous ARHGAP6 caused a significant increase in IKr levels, whereas no changes were observed in cells treated with the scrambled shRNA or in untreated HL-1 cells. shRNA treatment had no effects on the V1/2 of activation of IKr. In combination, these data show that HERG current levels are inversely correlated with ARHGAP6 expression in heterologous CHO cells, as well as in cardiac myocytes.

Figure 3. ARHGAP6 shRNA treatment increases HERG current in an atrial myocyte cell line (HL-1).

A. Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts from transfected CHO cells: 2 μgs of ARHGAP were transfected with 4 μgs of a carrier cDNA (GFP-Ire vector, lane 1), 4 μgs of shRNA directed against ARHGAP6 (lane 2), or 4 μgs of the scrambled shRNA control (i.e., the same nucleotide composition but in random order; lane 3). Two days post transfection, whole cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western Blot. After transfer, the membrane was cut into two halves and the top part, containing proteins of high molecular mass was probed with anti-ARHGAP6 10 antibody (AbNova Corp.; 1: 200 dilution) and a HRP-linked sheep anti mouse 20 antibody (1:10,000 dilution, GE HealthCare), while the bottom part of the membrane was probed with anti-calmodulin 10 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology; 1:500 dilution) and a HRP-linked sheep anti-mouse 20 antibody (1: 4,000 dilution). The results from three independent experiments are shown. Molecular mass in kDa is indicated on the right. The arrow indicates the position of ARHGAP6 on the gel. B. Top: Representative current traces from HL-1 cells infected with ARHGAP6 shRNAi (left) and scrambled shRNAi (right). Cells were held at -40 mV, and then stepped to +60 mV in 10 mV increments for 1 sec before repolarizing to -40 mV. Bottom: I-V relation of the tail currents recorded at -40 mV in non-infected cells (●) and cells infected with scrambled shRNAi (○) and ARHGAP6 shRNAi (▲). On average, the peak tail current amplitude measured following depolarization to +60 mV was 9.0 ± 1.5 (n = 8) in non-infected cells, 8.1 ± 1.4 pA/pF (n = 7) in cells infected by scrambled shRNAi, and 12.5 ± 0.9 pA/pF (n = 6) in cells infected by ARHGAP6 shRNAi (P < 0.001).

HERG regulation by ARHGAP6 is independent of GTPase activity

RhoGAPs function to accelerate the hydrolysis of bound GTP for GDP at the rho GTPase catalytic site, while rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (rho GEFs) restore rho to its GTP-bound form (22). Since it has previously been shown that rho can mediate ERG inhibition through the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) in a rat pituitary cell line (31), we tested whether inhibition of rhoGAP activity blocks the effects of ARHGAP6 on HERG. To this end, we used a dominant-negative form of rhoA [rhoA(N19)] that forms unproductive complexes with the rho GEFs (32) to prevent activation of endogenous rhoA. We co-expressed rhoA(N19) and HERG and observed that HERG current amplitude was indistinguishable from HERG alone (Figure 4). The kinetic properties of the HERG current were not altered by rhoA(N19) expression.

Figure 4. Dominant negative rhoA(N19) supports ARHGAP6 effects on HERG.

A. Representative current traces from cells transfected with HERG plus EGFP (left), HERG plus rhoA(N19) plus EGFP (middle) and HERG plus rhoA(N19) plus ARHGAP6 (right) (a total of 4.5 μg cDNA, each sample). The pulse protocol was as described in Figure 2. For easy viewing, the current traces recorded at -60 mV (bottom trace), 0 mV, and +60 mV (top trace) are shown in red. B. I-V relationship of activating currents recorded in cells expressing HERG alone (○; n = 11), HERG plus rhoA(N19) (□; n = 8) and HERG plus rhoA(N19) plus ARHGAP6 (▲; n = 12). C. I-V relationship of the tail currents. The average peak tail current amplitude measured following depolarization to +40 mV was 30.2 ± 4.6 pA/pF in the absence, 26.2 ± 6.7 pA/pF in the presence of rhoA(N19) (P = NS), and 6.4 ± 0.9 pA/pF in the presence of both rhoA(N19) and ARHGAP6 (P < 0.001).

Next, we determined if the presence of rhoA(N19) interfered with the ability of ARHGAP6 to modulate HERG. In cells co-expressing rhoA(N19) and ARHGAP6, the amplitude of HERG current was decreased (Figure 4) to a similar extent as with ARHGAP6 alone. Thus, ARHGAP6 was able to down-regulate HERG current in the presence of a dominant-negative form of rhoA, suggesting that active rhoA is not required in this paradigm.

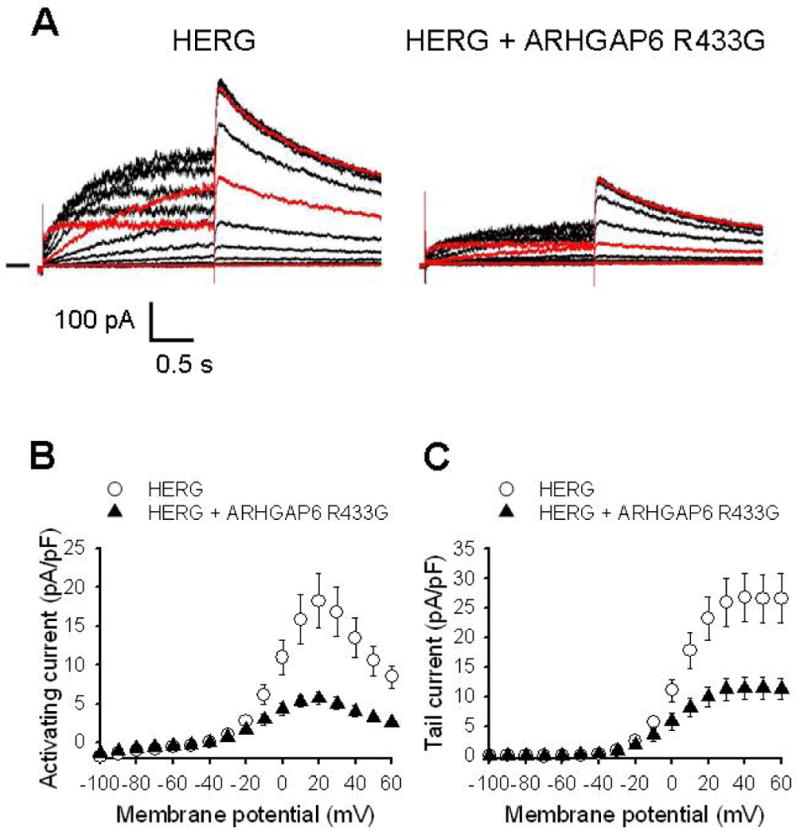

The results in Figure 4 suggest that either ARHGAP6 regulation of HERG current occurs through a rho protein other than rhoA, or that the rhoGAP function of ARHGAP6 is not required for HERG regulation. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we measured HERG current in the presence of an ARHGAP6 deficient in rhoGAP activity. Nine amino acids within the rhoGAP domain of ARHGAP6 are conserved in all rhoGAP family members, including an invariant arginine that participates directly in the hydrolysis reaction and stabilization of the GTP/GDP transition state (22). Mutation of the conserved arginine at position 433 to a glycine (R433G) abolishes the rhoGAP activity of ARHGAP6 (20). We compared currents recorded in cells expressing HERG in the presence or absence of ARHGAP6R433G. Figure 5 shows that, expression of ARHGAP6R433G, like WT ARHGAP6, significantly reduced HERG current amplitude, whereas activation, inactivation, and deactivation gating kinetics remained unchanged (data not shown). These results suggest that rhoGAP activity is not responsible for ARHGAP6 modulation of HERG.

Figure 5. GAP-deficient ARHGAP6R433G decreases HERG currents.

A. Representative current traces from cells transfected with HERG plus EGFP (left) and HERG plus ARHGAP6R433G (right) (1.5 μg each cDNA). The pulse protocol was as described in Figure 2. To improve ease of viewing, the current traces recorded at -60 mV (bottom trace), 0 mV and 60 mV (top trace) are shown in red. B, I-V relationship of activating HERG currents recorded in the absence (○; n = 16) and presence (▲; n = 14) of ARHGAP6R433G. C, I-V relationship of HERG tail currents. The average peak tail current amplitude measured following depolarization to +40 mV was 26.8 ± 4.1 pA/pF in the absence and 11.4 ± 1.9 pA/pF in the presence of ARHGAP6R433G (P < 0.001).

ARHGAP6 expression affects cytoskeletal arrangements of HERG-expressing cells

Prior studies indicated that expression of ARHGAP6 results in marked changes of cytoskeletal arrangements and cell morphology (20). To determine whether the same changes occur in cells expressing HERG, we stained stably HERG-expressing HEK cells with phalloidin to outline the actin cytoskeleton. The results showed that ARHGAP6 expression induced a more diffuse patterning of the actin cytoskeleton and loss of overall cytoskeletal organization (supplementary data, Figure 3). Thus, we propose that cytoskeletal elements required for efficient HERG trafficking are diminished when ARHGAP6 activity is enhanced.

PLC mediates the effects of ARHGAP6 on HERG currents

Recently, it has been reported that ARHGAP6 enhances the enzymatic activity of PLC-δ1 and that the two proteins co-immunoprecipitate from transfected cell extracts (23). A link between PLC activation and HERG current levels was previously established by McDonald's group who showed that HERG current amplitude and kinetics are sensitive to PLC-dependent PIP2 levels (33). We therefore decided to investigate whether PLC is a necessary intermediary for the effects of ARHGAP6 on the HERG current. To accomplish this, we used the specific PLC inhibitor U-73122 and its inactive congener U-73343 (34;35). To avoid having to transfect multiple cDNAs, we turned to a stably HERG-expressing HEK cell line (kindly provided by Dr. Craig January, University of Wisconsin). Treatment of cells with the inactive compound U-73343 did not alter the current levels we observed in untreated cells. As in HERG-expressing CHO cells (Figure 2), overexpression of ARHGAP6 in the stable HEK cell system resulted in a 39 % decrease in HERG current amplitude (Figure 6B, compare solid circles and triangles). However, when PLC was inhibited by 30 minutes of U-73122 application prior to patch clamp analysis, ARHGAP6 no longer diminished current levels (Figure 6B, compare open circles and triangles). Thus, enhanced PLC activity caused by increased levels of ARHGAP6 is a required intermediary that leads to decreased PIP2 levels, which then negatively influence HERG current amplitude (33).

Figure 6. ARHGAP6 function is dependent on active PLC.

A. Representative current traces from cells HEK293 cells stably expressing HERG transfected with ARHGAP6 (1.5 μg) in the presence of 1 μM U-73122 (left) or U-73343 (right). The pulse protocol was as described in Figure 2. Current traces recorded at -60, 0 and 60 mV are shown in red. B. I-V relationship of HERG tail currents. The average peak tail currents measured following depolarization to +40 mV in cells expressing ARHGAP6 in the presence of U-73122 or U-73343 were 18.6 ± 2.2 pA/pF (○; n = 9) and 12.1 ± 1.9 pA/pF (●; n = 12) respectively (P < 0.05). The average peak tail currents in cells expressing GFP in the presence of U-73122 or U-73343 were 21.3 ± 3.3 pA/pF (∆; n = 8) and 20.0 ± 2.8 pA/pF (▲; n = 7) respectively (P = NS).

ARHGAP6 regulation requires a consensus SH3 binding domain in the HERG distal C-terminus

Given the consistent effect of ARHGAP6 on current amplitude and the lack of effect on the voltage-dependent gating functions, we hypothesized that the effects of ARHGAP6 may relate to increased levels of HERG at the membrane. Prior studies have implicated the C-terminus of HERG in its trafficking to the cell membrane (36-38). RhoGAP family members are known to contain functional motifs, including protein-protein and protein-lipid adaptor cassettes such as SH2 and SH3 (22) binding domains that are also known to play important roles in regulatory interactions involving ion channels (39;40). Two major classes of SH3 binding domains were initially identified from a library of peptide ligands (41). The SH3 ligand consensus of the abl protein (a class I SH3 ligand consensus motif) is depicted in Figure 7A. It shows close homology with a domain in the distal C-terminus of HERG. To evaluate the possibility that HERG responds to ARHGAP6 via this proline-rich, putative consensus SH3 binding domain (amino acids 1093-1096), we mutated it to four alanines (HERG1093-1096A). Given the number of mutations, even single residue substitutions in the HERG C-terminus that disrupt gating (42) or trafficking function (36;37), it was possible that HERG1093-1096A would evoke a major disruption of C-terminal tertiary structure. However, as illustrated in Figure 7, currents recorded from cells expressing HERG1093-1096A were not different from currents recorded in cells expressing WT HERG. Significantly, currents recorded from CHO cells transfected with HERG1093-1096A in the presence of ARHGAP6, were indistinguishable from those recorded in its absence. Figure 7, shows that unlike ARHGAP6 co-expression with WT HERG (Figure 2), the tail current amplitude at +40 mV of HERG1093-1096A alone was not different from the value obtained in cells co-expressing HERG1093-1096A plus ARHGAP6 (24.2 ± 3.6 pA/pF; n = 14 vs. 23.8 ± 3.9 pA/pF; n =13; P = NS; respectively). The gating of HERG1093-1096A was also not altered by ARHGAP6 expression. Hence, mutation of the putative HERG SH3 binding domain prevents the ARHGAP6 mediated down-regulation of HERG current.

Figure 7. The HERG C-terminus contains a consensus SH3 domain that determines ARHGAP6 response.

A. Alignment of HERG residues 1082 to 1102 with a prototypical SH3 binding protein (41). Residues 1093-1096, which were mutated in construct HERG1093-1096A are boxed. Boldface indicates the most highly (>90%) conserved residues within the SH3 binding domain. θ and ψ indicate aromatic and aliphatic residues, respectively. Underlined residues are conserved between the presumptive HERG and the abl SH3 binding domains. B. ARHGAP6 does not increase the amplitude of current associated with HERG1093-1096A. Left, representative current traces from cells transfected with HERG1093-1096A plus EGFP (left) and HERG1093-1096A plus ARHGAP6 (right) (1.5 μg each cDNA). The pulse protocol was as described in Figure 2. C. Left, I-V relationship of activating currents recorded in cells expressing HERG1093-1096A in the absence (○; n = 14) and presence of ARHGAP6 (▲; n = 13). Right, I-V relationship. Average peak tail current amplitude measured following depolarization to +40 mV was 24.2 ± 3.6 pA/pF in the absence and 23.8 ± 3.9 pA/pF in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS).

ARHGAP6 co-expression down-regulates membrane levels of HERG

To better quantify ARHGAP6 effects on the localization of HERG to the plasma membrane, we developed an antibody-based chemiluminescent assay specific for membrane-associated HERG protein. To this end, CHO cells co-transfected with WT HERG or HERG1093-1096A plus or minus ARHGAP6 were grown in culture for 24 hrs and then trypsinized, counted and transferred to 96 well plates. 26 hrs post transfection, intact cells were incubated with an antibody directed against an extracellular epitope of HERG. Specific cell surface staining was quantified as a function of chemoluminescence measured upon exposure to an HRP-linked secondary antibody in the presence of peroxidase substrate. In cells transfected with HERG plus ARHGAP6 the HRP-dependent signal was reduced by 35 % compared to cells transfected with HERG alone (Figure 8). Importantly, in cells transfected with HERG1093-1096A plus ARHGAP6 the signal measured was not different from that obtained in cells transfected with HERG1093-1096A alone. Again, this is consistent with our electrophysiology findings described in figure 7 and indicates that ARHGAP6 reduces HERG K+ current magnitude by decreasing the number of HERG channels at the plasma membrane.

We then tested the hypothesis that ARHGAP6 binds directly to the HERG C-terminus through the putative consensus SH3 binding domain. To this end, we transfected CHO cells with HERG and an ARHGAP6-GFP fusion construct, and co-immunoprecipitated with either an anti-GFP or an anti-HERG antibody. The results did not show the formation of stable immune complexes suggesting that HERG and ARHGAP do not interact directly. We propose that the ARHGAP6 effect on HERG is mediated by one or more regulatory factors, and that the HERG C-terminal consensus SH3 binding domain is involved in this regulation.

Discussion

Our prior studies have shown that C. elegans strain unc-103(n500), mutant for the worm homolog of HERG, can be used as the background for an in vivo screen to identify HERG-regulating proteins (13). By sequentially knocking-down the expression of every gene contained on chromosome I of unc-103(n500), we identified C01F4.2 as a potential regulator of UNC-103 using an egg-laying assay (Figure 1B). We identified the human ortholog of C01F4.2 as ARHGAP6, a member of the rhoGAP family. While rhoGAP family proteins are well established as the major regulators of rho GTPases, by stimulation of GTP hydrolysis (20), rhoGAP family members contain other functional motifs, including protein-protein and protein-lipid adaptor cassettes such as SH2, SH3, and pleckstrin homology domains (22;43). The functions of many of these domains in rhoGAP family proteins remain unclear.

ARHGAP6 is deleted in patients with microphthalmia with linear skin defects (MLS syndrome), an X-linked dominant, male-lethal disorder characterized by eye, skin and central nervous system malformations (44), and the phenotype may be complicated by additional abnormalities which include cardiac conduction disturbances (45). It has been shown that the loss of the rhoGAP function of ARHGAP6 does not contribute to the MLS phenotype, suggesting that another function of ARHGAP6 may contribute to this disease (20). Most recently, it was shown that enhanced ARHGAP6 activity causes an increase in the VMax of PLC (23), an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of PIP2 into the potent intracellular messengers 1,4,5 inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacyl glycerol (DAG). A large number of ion channels and transporters, including the HERG channel are modulated in response to fluctuating PIP2 levels (46-49). Indeed, the HERG channel was the first voltage-gated K+ channel shown to be sensitive to PIP2 depletion from the membrane of cultured mammalian cells following PLC activation by α1A-adrenergic receptor stimulation (50). In addition to being the precursor of signaling molecules, PIP2 also serves as a key regulator of the actin cytoskeleton, and of exocytosis and endocytosis (51-54).

To determine if the human orthologs of C01F4.2 and UNC-103, ARHGAP6 and HERG, display a functional interaction, we employed complementary methods: measurement of HERG current via whole-cell patch-clamp and biochemical measurements of HERG cell surface expression. Both approaches revealed ARHGAP6-dependent down-regulation of HERG from the plasma membrane. In patch-clamp studies we observed a decrease in HERG current amplitude in the presence of ARHGAP6 without modification of the gating properties of the channel in multiple cell systems (Figures 2 and 6). Knockdown of endogenous ARHGAP6 by virally transduced inhibitory shRNA in the atrial myocyte cell line HL-1 resulted in an increase in IKr recorded from these cells (Figure 4). Our experiments with the PLC inhibitor U-73122 suggest a possible mechanism that accounts for the effects of ARHGAP6: Enhanced activity of ARHGAP6 results in consumption of PIP2 due to PLC activation, with a concomitant decrease in HERG current (Figure 6). Similar to the results of our study, McDonald et al. reported a positive effect of increasing PIP2 on HERG current amplitude, although, in contrast to our findings, they observed effects on gating (33). Our own findings are consistent with an effect on expression of HERG at the plasma membrane (Figure 8). Thus, the ARHGAP6-PLC pathway we observed in the current study affects the cytoskeletal architecture with possible negative effects on HERG trafficking. This conclusion is supported by our observation that the cytoskeleton is disordered in ARHGAP6 expressing cells (supplemental data, Figure 3). The precise role of PIP2 in this particular paradigm, and the signals that impact ARHGAP6 activity and/or expression levels, will have to be investigated in more detail in the future.

Prior studies have shown that various domains within the C-terminus of HERG play constitutive roles in HERG trafficking and channel maturation (36;37). We found that a consensus SH3 binding domain in the distal HERG carboxyl terminus (residues 1093-1096) mediates the ARHGAP6 effects (Figure 7). Cell surface expression of HERG was quantified using an antibody-based chemiluminescent assay, which showed that the number of HERG channels at the membrane was reduced by 35%, while HERG1093-1096A remained unaltered in presence of ARHGAP6 (Figure 8). Thus, a decrease in HERG localization to the plasma membrane is the most likely explanation for the reduction of whole-cell current in the absence of gating changes we observe when HERG is coexpressed with ARHGAP6 (Figure 2). In combination, our data indicate that ARHGAP6 is a negative regulator of HERG surface expression.

In addition, we determined that the effects of ARHGAP6 on HERG trafficking are rho GTPase independent (Figures 4 and 5). Prior studies also showed that ARHGAP6 has rho-independent functions, including effects on the actin cytoskeleton. Thus, cultured cells expressing exogenous ARHGAP6 undergo morphological changes that include cell retraction, loss of adhesion to the coverslip and the extension of branched processes (20). The operative mechanism we have observed in this study may thus be analogous to the rat amiloride-sensitive Na+ (rENaC) channel which interacts with the cytoskeletal protein α spectrin, via an SH3 binding region in rENaC, providing a means to retain proteins in the membranes of polarized epithelial cells (55). Since co-immunoprecipitation assays suggested that ARHGAP6 and HERG do not form stable complexes, it is possible that HERG may interact with one or more cytoskeletal proteins via its consensus SH3-binding domain, and that ARHGAP6 dependent PLC activation and changing PIP2 levels modulate this interaction, thus impacting the localization of HERG at the cell membrane.

Based on the observation that ERG contributes to the membrane potential of multiple tissues in mammals (56-59) we hypothesize that in C. elegans, UNC-103 is involved in setting the resting membrane potential of the egg-laying muscles (and perhaps other tissues in which it is expressed). It is thus possible that the unc-103(n500) channel inappropriately hyperpolarizes the egg-laying muscles rendering them refractory to contraction in response to synaptic stimuli. Moreover, although CO1F4.2 was identified as a suppressor of the unc-103(n500) egg-laying defect implying that it is a positive regulator of UNC-103 activity, we nevertheless demonstrated that its mammalian homolog, ARHGAP6, is a negative regulator of HERG activity. We therefore conclude that the functional consequences of interaction of the worm orthologs are opposite to that of the human proteins measured in our systems.

Multiple proteins are known to modulate ERG function in heterologous expression systems (9;12;14;60). Like our study, most of these studies assess IKr function at room temperature, although the possibility that currents have slightly different characteristics at physiologic temperature cannot be excluded. Intracellular second messenger pathways also impact HERG function (11;16;33;61-65). Rac and Rho, GTPases involved in small G-protein mediated signalling, contribute to hormonal regulation of rat ERG (31). These studies indicate that ERG is regulated by multiple signal transduction cascades. Here, we identify an ARHGAP6-PLC pathway as a negative regulator of HERG membrane expression. As such, loss-of-function of ARHGAP6, due to genetic or regulatory influences would be predicted to increase trafficking of HERG to the plasma membrane, resulting in increased IKr, and faster repolarization of the cardiac action potential. Conversely, enhanced ARHGAP6-HERG signalling would tend to decrease IKr levels and delay repolarization. Depending upon the environment, either one of these effects on the action potential can be proarrhythmic (7;66). Moreover, given that ARHGAP6 has multiple functionalities and that HERG is involved in processes ranging from neuronal development to cardiac repolarization (2;67;68), the modification of HERG function by ARHGAP6 and its upstream regulators could well impact phenotypes associated with genetic disorders affecting multiple organs in addition to cardiac arrhythmia syndromes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Figure 1A. Amino acid alignment of HERG and unc-103. The full sequence of unc-103 is shown. The first 308 amino acids of HERG are omitted. Identities are indicated in yellow. Conserved residues are shown in green.

Figure 1B: Amino acid alignment of the GAP domains of CO1F4.2 and ARHGAP6. Identities are indicated in yellow. Conserved residues are shown in green.

Figure 2. ARHGAP6 over expression does not modify KCNQ1 currents in CHO cells. Activating current-voltage (I-V) relationship recorded in cells expressing KCNQ1 alone or with ARHGAP6. Inset, representative current traces from cells transfected with KCNQ1 plus EGFP (left) and KCNQ1 plus ARHGAP6 (right) (1.5 μg cDNA each). Cells were held at -80 mV, and then stepped to test potentials between-100 and +60 mV in 10 mV increments for 2 sec before repolarizing to -40 mV. On average, the activating current amplitude measured at the end of a +60 mV pulse was 28.9 ± 6.1 pA/pF (n = 6) in the absence, and 28.0 ± 5.8 pA/pF (n=7) in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS).

Figure 3 ARHGAP6 over-expression causes cytoskeletal rearrangements in HERG expressing HEK cells. Cells were transfected with either ARHGAP6 (panels A, B, C) or GFP plasmids (panel D). The top row shows phalloidin staining only. The bottom row shows an overlay of green-fluorescence associated with ARHGAP6 (panels A-C) or GFP expression (panel D), phalloidin-associated fluorescence (red), and Nomarski optics. Cells that were expressing ARHGAP6 or GFP are indicated by white dots. Panels A-C indicate a more diffuse staining of the cytoskeleton in ARHGAP6 transfected cells than in untransfected cells, where actin is highly organized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Igna VanDen Veyver (Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston) for kindly providing the human ARHGAP6 WT and mutant cDNAs (splice isoform 1). We thank Dr. Craig January (University of Wisconsin) for providing the stably HERG-expressing HEK cells, and Dr. Neil Bhowmick (Vanderbilt University) for the RhoA(N19) cDNA. We thank Toni Grim for expert technical assistance. Supported by NIH/NHLBI HL69914 (SK) and NIH/NHLBI P01 PPG HL46681 (JRB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Wymore RS, Gintant GA, Wymore RT, Dixon JE, McKinnon D, Cohen IS. Tissue and species distribution of mRNA for the IKr-like K+ channel, erg. Circ Res. 1997;80(2):261–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avossa D, Rosato-Siri MD, Mazzarol F, Ballerini L. Spinal circuits formation: a study of developmentally regulated markers in organotypic cultures of embryonic mouse spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2003;122(2):391–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Y, Golden CM, Ye J, Wang XY, Akbarali HI, Huizinga JD. ERG K+ currents regulate pacemaker activity in ICC. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285(6):G1249–G1258. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00149.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parr E, Pozo MJ, Horowitz B, Nelson MT, Mawe GM. ERG K+ channels modulate the electrical and contractile activities of gallbladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284(3):G392–G398. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00325.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME, Keating MT. A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell. 1995;81(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Green ED, Keating MT. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80(5):795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang CE. Congenital and acquired long QT syndrome. Current concepts and management. Cardiol Rev. 2004;12(4):222–34. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000123842.42287.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roden DM, Viswanathan PC. Genetics of acquired long QT syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2025–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI25539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott GW, Sesti F, Splawski I, Buck ME, Lehmann MH, Timothy KW, et al. MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell. 1999;97(2):175–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrlich JR, Pourrier M, Weerapura M, Ethier N, Marmabachi AM, Hebert TE, et al. KvLQT1 modulates the distribution and biophysical properties of HERG. A novel alpha-subunit interaction between delayed rectifier currents. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(2):1233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagan A, Melman YF, Krumerman A, McDonald TV. 14-3-3 amplifies and prolongs adrenergic stimulation of HERG K+ channel activity. EMBO J. 2002;21(8):1889–98. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald TV, Yu Z, Ming Z, Palma E, Meyers MB, Wang KW, et al. A minK-HERG complex regulates the cardiac potassium current I(Kr) Nature. 1997;388(6639):289–92. doi: 10.1038/40882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen CI, McFarland TR, Stepanovic SZ, Yang P, Reiner DJ, Hayashi K, et al. In vivo identification of genes that modify ether-a-go-go-related gene activity in Caenorhabditis elegans may also affect human cardiac arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(32):11773–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306005101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roti EC, Myers CD, Ayers RA, Boatman DE, Delfosse SA, Chan EK, et al. Interaction with GM130 during HERG ion channel trafficking. Disruption by type 2 congenital long QT syndrome mutations. Human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(49):47779–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang T, Kupershmidt S, Roden DM. Anti-minK antisense decreases the amplitude of the rapidly activating cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Circ Res. 1995;77(6):1246–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Wang H, Wang J, Han H, Nattel S, Wang Z. Normal function of HERG K+ channels expressed in HEK293 cells requires basal protein kinase B activity. FEBS Lett. 2003;534(13):125–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park EC, Horvitz HR. Mutations with dominant effects on the behavior and morphology of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1986;113(4):821–52. doi: 10.1093/genetics/113.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiner DJ, Weinshenker D, Thomas JH. Analysis of dominant mutations affecting muscle excitation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141(3):961–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia LR, Sternberg PW. Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-103 ERG-Like Potassium Channel Regulates Contractile Behaviors of Sex Muscles in Males before and during Mating. J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2696–705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02696.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prakash SK, Paylor R, Jenna S, Lamarche-Vane N, Armstrong DL, Xu B, et al. Functional analysis of ARHGAP6, a novel GTPase-activating protein for RhoA. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(4):477–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer L, Prakash S, Zoghbi HY. Cloning and characterization of a novel rho-type GTPase-activating protein gene (ARHGAP6) from the critical region for microphthalmia with linear skin defects. Genomics. 1997;46(2):268–77. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon SY, Zheng Y. Rho GTPase-activating proteins in cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochocka AM, Grden M, Sakowicz-Burkiewicz M, Szutowicz A, Pawelczyk T. Regulation of phospholipase C-[delta]1 by ARGHAP6, a GTPase-activating protein for RhoA: Possible role for enhanced activity of phospholipase C in hypertension. Intl Jrl Biochem & Cell Biol. 2008;40(10):2264–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claycomb WC, Lanson NAJ, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, et al. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(6):2979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Zipperlen P, Martinez-Campos M, Sohrmann M, Ahringer J. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408(6810):325–30. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kupershmidt S, Snyders DJ, Raes A, Roden DM. A K+ channel splice variant common in human heart lacks a C-terminal domain required for expression of rapidly activating delayed rectifier current. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(42):27231–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kambouris NG, Nuss HB, Johns DC, Tomaselli GF, Marban E, Balser JR. Phenotypic characterization of a novel long-QT syndrome mutation (R1623Q) in the cardiac sodium channel. Circulation. 1998;97(7):640–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coso OA, Chiariello M, Yu JC, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, et al. The small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81(7):1137–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kupershmidt S, Yang IC, Hayashi K, Wei J, Chanthaphaychith S, Petersen CI, et al. The IKr drug response is modulated by KCR1 in transfected cardiac and noncardiac cell lines. FASEB J. 2003;17(15):2263–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1057fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White SM, Constantin PE, Claycomb WC. Cardiac physiology at the cellular level: use of cultured HL-1 cardiomyocytes for studies of cardiac muscle cell structure and function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(3):H823–H829. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00986.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storey NM, O'Bryan JP, Armstrong DL. Rac and Rho mediate opposing hormonal regulation of the ether-a-go-go-related potassium channel. Curr Biol. 2002;12(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feig LA. Tools of the trade: use of dominant-inhibitory mutants of Ras-family GTPases. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(2):E25–E27. doi: 10.1038/10018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bian J, Cui J, McDonald TV. HERG K(+) channel activity is regulated by changes in phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Circ Res. 2001;89(12):1168–76. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bleasdale JE, McGuire JC, Bala GA. Measurement of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C activity. Methods Enzymol. 1990;187:226–37. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)87027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith RJ, Sam LM, Justen JM, Bundy GL, Bala GA, Bleasdale JE. Receptor-coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C-dependent processes on cell responsiveness. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253(2):688–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akhavan A, Atanasiu R, Shrier A. Identification of a COOH-terminal segment involved in maturation and stability of human ether-a-go-go-related gene potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):40105–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kupershmidt S, Yang T, Chanthaphaychith S, Wang Z, Towbin JA, Roden DM. Defective human Ether-a-go-go-related gene trafficking linked to an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal in the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):27442–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng S, Ma L, Dong Y, Lin C, Ye J, Bahring R, et al. Clinical and electrophysiological characterization of a novel mutation R863X in HERG C-terminus associated with long QT syndrome. J Mol Med. 2004;82(3):189–96. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YH, Li MH, Zhang Y, He LL, Yamada Y, Fitzmaurice A, et al. Structural basis of the alpha1-beta subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature. 2004;429(6992):675–80. doi: 10.1038/nature02641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nitabach MN, Llamas DA, Thompson IJ, Collins KA, Holmes TC. Phosphorylation-dependent and phosphorylation-independent modes of modulation of shaker family voltage-gated potassium channels by SRC family protein tyrosine kinases. J Neurosci. 2002;22(18):7913–22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07913.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sparks AB, Rider JE, Hoffman NG, Fowlkes DM, Quilliam LA, Kay BK. Distinct ligand preferences of Src homology 3ádomains from Src, Yes, Abl, Cortactin, p53bp2, PLCgamma, Crk, and Grb2. PNAS. 1996;93(4):1540–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakajima T, Kurabayashi M, Ohyama Y, Kaneko Y, Furukawa T, Itoh T, et al. Characterization of S818L mutation in HERG C-terminus in LQT2: Modification of activation-deactivation gating properties. FEBS Letters. 2000;481(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01988-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hakoshima T, Shimizu T, Maesaki R. Structural basis of the Rho GTPase signaling. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2003;134(3):327–31. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindsay EA, Grillo A, Ferrero GB, Roth EJ, Magenis E, Grompe M, et al. Microphthalmia with linear skin defects (MLS) syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular characterization. Am J Med Genet. 1994;49(2):229–34. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320490214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kono T, Migita T, Koyama S, Seki I. Another observation of microphthalmia in an XX male: microphthalmia with linear skin defects syndrome without linear skin lesions. J Hum Genet. 1999;44(1):63–8. doi: 10.1007/s100380050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loussouarn G, Park KH, Bellocq C, Baro I, Charpentier F, Escande D. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP(2), controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K(+) channels. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5412–21. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bian Js, McDonald T. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate interactions with the HERG K+ channel. Pflügers Archiv European Journal of Physiology. 2007;455(1):105–13. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang CL. Complex roles of PIP2 in the regulation of ion channels and transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(6):F1761–F1765. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00400.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, et al. PIP(2) Activates KCNQ Channels, and Its Hydrolysis Underlies Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of M Currents. Neuron. 2003;37(6):963–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bian JS, Cui J, McDonald TV. HERG K+ channel activity is regulated by changes in phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Circulation Research. 2001;89(12):1168–76. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yaradanakul A, Feng S, Shen C, Lariccia V, Lin MJ, Yang J, et al. Dual control of cardiac Na+ Ca2+ exchange by PIP2: electrophysiological analysis of direct and indirect mechanisms. J Physiol (Lond) 2007;582(3):991–1010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:761–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Czech MP. Dynamics of phosphoinositides in membrane retrieval and insertion. Ann Rev Physiol. 2003;65(1):791–815. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milosevic I, Sorensen JB, Lang T, Krauss M, Nagy G, Haucke V, et al. Plasmalemmal Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate Level Regulates the Releasable Vesicle Pool Size in Chromaffin Cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(10):2557–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3761-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rotin D, Bar-Sagi D, O'Brodovich H, Merilainen J, Lehto VP, Canessa CM, et al. An SH3 binding region in the epithelial Na+ channel (alpha rENaC) mediates its localization at the apical membrane. EMBO J. 1994;13(19):4440–50. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohya S, Horowitz B, Greenwood IA. Functional and molecular identification of ERG channels in murine portal vein myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(3):C866–C877. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00099.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohya S, Asakura K, Muraki K, Watanabe M, Imaizumi Y. Molecular and functional characterization of ERG, KCNQ, and KCNE subtypes in rat stomach smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282(2):G277–G287. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00200.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Overholt JL, Ficker E, Yang T, Shams H, Bright GR, Prabhakar NR. HERG-Like potassium current regulates the resting membrane potential in glomus cells of the rabbit carotid body. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83(3):1150–7. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shoeb F, Malykhina AP, Akbarali HI. Cloning and functional characterization of the smooth muscle ether-a-go-go-related gene K+ channel. Potential role of a conserved amino acid substitution in the S4 region. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(4):2503–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Romey G, Attali B, Chouabe C, Abitbol I, Guillemare E, Barhanin J, et al. Molecular mechanism and functional significance of the MinK control of the KvLQT1 channel activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(27):16713–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cayabyab FS, Schlichter LC. Regulation of an ERG K+ current by Src tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(16):13673–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barros F, Gomez-Varela D, Viloria CG, Palomero T, Giraldez T, de la Pena P. Modulation of human erg K+ channel gating by activation of a G protein-coupled receptor and protein kinase C. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;511(2):333–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.333bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karle CA, Zitron E, Zhang W, Kathofer S, Schoels W, Kiehn J. Rapid component I(Kr) of the guinea-pig cardiac delayed rectifier K(+) current is inhibited by beta(1)-adrenoreceptor activation, via cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(2):355–62. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas D, Zhang W, Wu K, Wimmer AB, Gut B, Wendt-Nordahl G, et al. Regulation of HERG potassium channel activation by protein kinase C independent of direct phosphorylation of the channel protein. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59(1):14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gomez-Varela D, Barros F, Viloria CG, Giraldez T, Manso DG, Dupuy SG, et al. Relevance of the proximal domain in the amino-terminus of HERG channels for regulation by a phospholipase C-coupled hormone receptor. FEBS Letters. 2003;535(13):125–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 2002;415(6868):219–26. doi: 10.1038/415219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pancrazio JJ, Ma W, Grant GM, Shaffer KM, Kao WY, Liu QY, et al. A role for inwardly rectifying K+ channels in differentiation of NG108-15 neuroblastoma × glioma cells. J Neurobiol. 1999;38(4):466–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tseng GN. I(Kr): the hERG channel. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(5):835–49. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data

Figure 1A. Amino acid alignment of HERG and unc-103. The full sequence of unc-103 is shown. The first 308 amino acids of HERG are omitted. Identities are indicated in yellow. Conserved residues are shown in green.

Figure 1B: Amino acid alignment of the GAP domains of CO1F4.2 and ARHGAP6. Identities are indicated in yellow. Conserved residues are shown in green.

Figure 2. ARHGAP6 over expression does not modify KCNQ1 currents in CHO cells. Activating current-voltage (I-V) relationship recorded in cells expressing KCNQ1 alone or with ARHGAP6. Inset, representative current traces from cells transfected with KCNQ1 plus EGFP (left) and KCNQ1 plus ARHGAP6 (right) (1.5 μg cDNA each). Cells were held at -80 mV, and then stepped to test potentials between-100 and +60 mV in 10 mV increments for 2 sec before repolarizing to -40 mV. On average, the activating current amplitude measured at the end of a +60 mV pulse was 28.9 ± 6.1 pA/pF (n = 6) in the absence, and 28.0 ± 5.8 pA/pF (n=7) in the presence of ARHGAP6 (P = NS).

Figure 3 ARHGAP6 over-expression causes cytoskeletal rearrangements in HERG expressing HEK cells. Cells were transfected with either ARHGAP6 (panels A, B, C) or GFP plasmids (panel D). The top row shows phalloidin staining only. The bottom row shows an overlay of green-fluorescence associated with ARHGAP6 (panels A-C) or GFP expression (panel D), phalloidin-associated fluorescence (red), and Nomarski optics. Cells that were expressing ARHGAP6 or GFP are indicated by white dots. Panels A-C indicate a more diffuse staining of the cytoskeleton in ARHGAP6 transfected cells than in untransfected cells, where actin is highly organized.