Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to use a cross-cultural model to guide the exploration of common issues and the dynamic interrelationships surrounding entrée to tribal communities as experienced by four nursing research teams.

Method

Members of four research teams discuss the primary lessons learned about successful strategies and challenges encountered during their projects' early stages.

Results

Understanding the cultural values of relationship and reciprocity is critical to the success of research projects conducted in Native American communities.

Discussion

Conducting cross-cultural research involves complex negotiations among members of three entities: academia, nursing science, and tribal communities. The lessons learned in these four research projects may be instructive to investigators who have the opportunity to conduct research with tribal communities.

Keywords: cross-cultural research, research method, Native American, American Indian, tribal communities

Conducting research in tribal communities requires an approach that is sensitive both to the long history of tribal mistrust of research and to current tribal vulnerabilities associated with the conduct of research in their communities (American Indian Law Center, 1999; Carson & Hand, 1999; Manson, Garroutte, Goins, & Henderson, 2004; Maynard, 1974; Norton & Manson, 1996; Quandt, McDonald, Bell, & Arcury, 1999). Establishing relationships of trust and reciprocity is critical (Rogers & Petereit, 2005). Most research reports focus on the results of studies; there are fewer reports about the process of conducting studies with Native American communities. The purpose of this article is to use a cross-cultural model to guide the exploration of common issues and the dynamic interrelationships surrounding entrée to tribal communities as experienced by four nursing research teams. Information in this article is expected to be of value to nurse scientists, other members of the academic community, and Native American participants who are engaged in cross-cultural research in Native American communities.

Review of the Related Literature

In the United States, there are more than 561 federally recognized Native American tribes. Although each has a unique culture, there are some commonalities across tribes (Red Horse, 1980a, 1980b; Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project, 2002; Weaver & White, 1997). These commonalities represent strengths that contribute to the significant resiliency of Native American people over the centuries. Included among these strengths are a strong sense of spirituality, the value placed on family, and the interdependence of members of the tribal community (Red Horse, 1980a, 1980b; Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project, 2002; Weaver & White, 1997). Those involved in research efforts must be aware of these strengths as well as the challenges that may arise when conducting research with Native American people.

Central to assessing these challenges is understanding of and respect for the traumatic history Native American people have experienced with the colonization of their homelands by Western European nations. All tribes share a history of hardships and restrictions, including the loss of land; broken promises and treaties; restrictions of shelter and food; the attempted destruction of language, religion, and culture; stereotyping; and the burden of government interference. Negative sequelae from this history persist in tribal communities today. From the literature reviewed, it is evident that Native Americans also have experienced negative results from research practices (American Indian Law Center, 1999; Carson & Hand, 1999; Manson et al., 2004; Maynard, 1974; Norton & Manson, 1996; Quandt et al., 1999). Because of this history of exploitation and abuse by research institutions and the government, mistrust of those who conduct research exists (Mitchell & Baker, 2005).

Increasingly, tribal communities are developing institutional review boards (IRBs) and requiring that researchers apply for project approval prior to conducting research in a community. Tribal members recognize their vulnerabilities associated with research and wish to maintain decision-making authority regarding which projects are allowed to be conducted in their communities. In addition, in some communities, publications and presentations are required to be approved prior to submission, and ownership of the data may be requested to stay at the local level. It is important that researchers and community members discuss the project in relation to community needs to ensure project relevance and obtain permission to conduct the research in any given community. This can be a time-consuming process (Manson et al., 2004), with significant financial expenditures that must be acknowledged when planning grant applications and timelines (Norton & Manson, 1996). Often no financial compensation for either community members or researchers is available for this “up-front” work. Yet taking the time to develop trusting partnerships, establish a commitment to the tribal members, and appreciate the sovereignty of tribal communities is foremost in ensuring the success of research projects (Tom-Orme, 2006).

Entering into tribal communities can be fraught with potential and actual breaches of community protocols (Mitchell & Baker, 2005). Factors that contribute to hesitancy in allowing researchers entry into their communities include distrust of research personnel, researchers' lack of understanding and/or respect toward cultural practices, and the potential for reporting results that emphasize problems that, in turn, can demoralize and stigmatize communities while reinforcing negative stereotypes (American Indian Law Center, 1999; Burhansstipanov, Christopher, & Schumacher, 2005; Manson et al., 2004; Mitchell & Baker, 2005). Early identification of nuances specific to each tribal community might avert potential breaches that can occur in relation to entry into their communities. It is critical for researchers to reflect on the ability to establish a working relationship prior to the initiation of a project.

The potential for exploitation and repetition of past abuses might make it difficult for members of tribal communities to perceive many benefits from participating in research relative to the potential risks (Norton & Manson, 1996). Many Native American tribes prefer that a community-based participatory approach be utilized when conducting studies that involve their communities (Burhansstipanov et al., 2005). This approach provides the opportunity for researchers, community members, and agency representatives to have equitable involvement in the research process from its inception to its conclusion. The use of a partnership approach increases the likelihood of conducting research that is relevant to the community and that will make contributions to the scientific literature. Developing a relationship with the community in which representatives from the community and the academic institution both have a role in each step of the research process is essential for success of the project (Burhansstipanov et al., 2005).

Researchers must work diligently with tribal community leaders to ensure that relevant members of the community are involved in all stages of the research process. Acknowledging, valuing, and adapting research based on community members' input is vital for the success of the project. In addition, it is important to provide adequate compensation to community members for their contributions to the research project. Using a community-based participatory approach requires a stance of long-term commitment to the community partnership and begins with taking the necessary time to establish relationships that form the basis for trust to develop and deepen (Norton & Manson, 1996).

Commitment to the community and cultural sensitivity provide the foundation for successful research within tribal communities. Illustrating the importance of research to the community and demonstrating the direct and immediate benefits to the people of the community must be part of the study purpose (Manson et al., 2004). In addition, the process and methodology by which the research is conducted are also noteworthy. Because of the inherent cultural differences of the research team and the community of interest, it is crucial to the success of the project to demonstrate congruency with cultural values and modes of interaction (Dodgson & Struthers, 2005; Red Horse, Johnson, & Weiner, 1989; Stoddard, 1997). Equitable working relationships with Native American communities may include working with tribal leaders in all discussions, having a local office, employing local community members, and providing adequate compensation. Benefit perception may increase as research is translated into meaningful action (Norton & Manson, 1996).

The Negotiating Three Worlds Model

The impetus for this article emerged from discussions among nurse researchers who were involved with four unrelated projects with several Native American communities. We (the researchers) had been affiliated, at some point in our work, with the Center for Research on Chronic Health Conditions at Montana State University College of Nursing. We convened at the invitation of the center's principal investigator, who had noticed some similar procedural challenges and successes in our work.

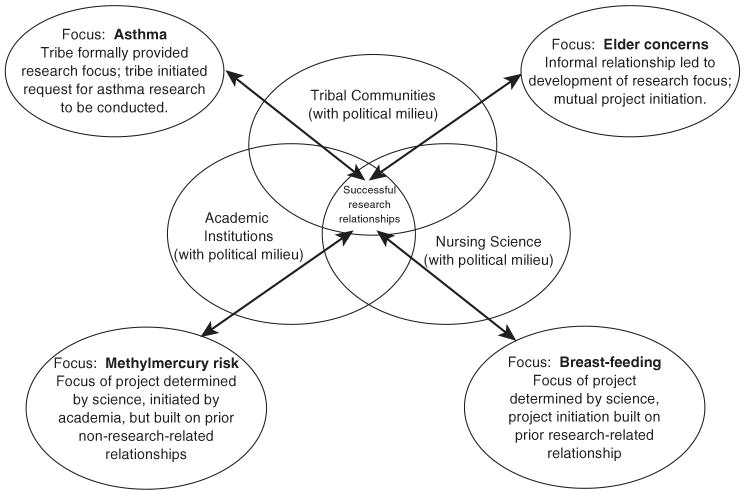

Through discussion of our common experiences with the four projects, we became aware of the ramifications of our involvement with the complex and interrelated activities of three dynamic entities: academic institutions, nursing science, and tribal communities. With this new understanding, we developed a model depicting the interactions of the four research projects with these entities (see Figure 1). The cumulative requirements of these three diverse entities, each with their own powerful political and bureaucratic milieus, influenced and directed the research process for all of the projects.

Figure 1. Negotiating Three Worlds: Research Focus and Project Initiation Model.

The Venn diagram at the center of the model in Figure 1 represents the dynamic interrelationships of the three entities. The academic institution often serves as a venue through which funds for research projects are secured and administered. As stewards of grant funding, members of academic institutions mandate and monitor requirements that must be followed by those conducting the research. Conflicts can arise when there is dissonance between the requirements of the institution and the cultural needs of the participants.

Nursing science is concerned with the building of a knowledge base to promote the health of individuals, families, and communities. Political pressures in this arena are directly linked to funding sources that have a responsibility to address the integrity of the scientific process. The positivist worldview continues to dominate perceptions of what constitutes good science. Funding sources have been slow to trust research approaches arising from other ontological perspectives. These other perspectives, however, may be more appropriate for conducting relevant research with ethnic minority groups.

Tribal leaders, as mentioned earlier, may have a well-founded and long-standing distrust of the benefits of research endeavors for their communities. Tribal communities, as sovereign nations, have their own agendas that may or may not include the acceptance of various academic research projects conducted within their communities. Finally, the balance among the desires and behaviors of tribal individuals, agencies, and communities constitutes a dynamic political process that outside scientists may find difficult to grasp.

In the second part of the model, we placed each of the projects in proximity to those entities that were involved in the development of the research focus and the initiation of the project. The manner in which the research focus was developed and the project was initiated played a large part in determining the course of the research process.

Introduction to the Projects

The four unrelated projects were conducted in eight separate sites, or communities, involving a total of 11 tribes. All projects received IRB approval from the universities with which they were affiliated. All projects also received approval from their affiliated tribal councils. Two projects received two additional levels of approval from (a) their affiliated tribal health boards and (b) their Indian Health Service IRBs (IHS IRBs). To acquaint the reader with the four projects, we describe each using the following common categories: impetus and opportunities, emergence of the project in the community, initial steps and negotiations, implementing the project, and evaluating the process.

Project 1: Screening Native American Children for Asthma

Impetus and Opportunities

This project emerged during a meeting between the director of an epidemiology center and a tribal health board, when a concern about the seemingly high rate of asthma in children surfaced. Following this meeting, an announcement was released regarding the opportunity to write a grant proposal as part of the Native American Research Centers for Health initiative, funded through the Indian Health Service and the National Institutes of Health. A researcher from the university was selected to write this portion of the grant. The impetus, then, for the asthma screening project was derived from a need identified among the tribal leaders and the availability of a nurse researcher to write a competitive grant proposal and conduct the research with two tribal communities. Please note the upper-left-hand corner of Figure l.

Emergence of the Project in the Community

The focus of initial discussions regarding the project was on maximizing participation by the two tribal communities. The research protocol allowed the research team to work with the communities to determine how best to conduct asthma screenings in children. A secondary purpose of the grant was to build research capacity in the two tribal communities. Hiring two research assistants, each of whom were members of their respective tribal communities, helped to achieve these goals.

Initial Steps and Negotiations

Successes

Involvement of an academic liaison by the university to facilitate negotiations among the researchers and members of the tribal communities was key to the success of gaining entry into each of the communities. This three-way relationship was characterized by mutual respect. In addition, we followed the steps necessary for conducting research in Indian country. We initially contacted the tribal health director to explain the purpose of the research, to ascertain that the research was something that would be of value for their community, and to ask for support in our efforts. Once support from the tribal health director was garnered, we approached the tribal health board, once again to ensure that we had support and a commitment to the project. Finally, the tribal council was approached for support and approval of the research project. Once these steps were completed, we applied for institutional review from the academic institution and from the Indian Health Service.

Challenges

Major challenges prior to the initial phase of the project involved obtaining resolutions from the tribal communities and institutional reviews from the academic institution and the IHS IRB. There were unexpected changes in personnel at both of the tribal sites, which delayed the acquisition of the resolutions needed to seek approval from the IRB. Gentle reminders from the liaison and health directors in both communities spurred the council to pass the resolution. The process from the initial contact with the communities to the point of obtaining the resolution was approximately 6 months.

Obtaining approval from the IRB of the university and the IHS IRB was delayed because of the complex nature of the research proposal. There were three phases to the research project, with each successive phase dependent on the findings of the preceding phase. The initial phase of the research consisted of conducting focus groups with members of the tribal communities to ascertain ways to develop an asthma screening process that would be most appropriate for their community. The second phase of the research, conducting the asthma screenings, was adapted based on the results of the focus group discussion. The IHS IRB approved the first phase of the study but indicated they would approve the second phase only after the focus groups had been conducted and appropriate protocol changes made. Though reasonable and understandable, this meant that the researcher needed to resubmit the proposal to the IHS IRB and await approval more than once.

Implementing the Project

Successes

During the focus group discussions, rich data were acquired to be used to shape the asthma screening protocol. A total of 27 community members participated in the focus groups. The research team believes that the high number in attendance was because of the research assistants' ties to and knowledge of each community. There had been some concern raised among participants about how the data would be used and where they would be housed. Participants were reassured that the data would remain with the tribe. Although tribal members did acknowledge that screening children for asthma was important, they also clearly identified that many screenings had been done on the Native American population and that they would also like help dealing with the problem of asthma. Members of the research team acknowledged their concern and explained that identifying the prevalence is the necessary first step toward writing a more comprehensive research proposal that could provide an intervention for the children with asthma.

Challenges

Geographic distance of the tribal communities from the university created the major challenge associated with implementation of the research project. Because of the remote location of one community in particular, it has been difficult to secure travel arrangements at reasonable costs. Traveling to that community to conduct screenings involves 3 days at a minimum. In addition, the researcher's teaching responsibilities often had to take precedence over research, making it difficult to arrange a schedule that was compatible for all parties involved.

Evaluating the Process

Because the asthma screening project originated from the administrative level of the epidemiology center and the tribal health board, the bureaucratic barriers have been minimal. The project was initiated from tribal health concerns, so acceptance of the research has not been a major concern. The primary challenges in this project have been related to time. The time that it took to go through both the academic as well as the IHS IRBs was problematic. In addition, traveling to each reservation required a major commitment from the university research team. Despite these issues, the timelines delineated in the project proposal have been met. Flexibility, adaptability, and respect have been the elements of success for this project.

Project 2: Caring for Native American Elders

Impetus and Opportunities

The Caring for Native American Elders Project was initiated by way of an informal relationship developed through a series of synchronous events between a Native American social worker and a non-Native nurse (see the upper-right-hand corner of Figure 1). The social worker had, in the course of her work, observed with concern the manner in which elders were treated in some of the families she visited. In addition to her own concerns, she knew that members of some of those families also were worried about their elders. The social worker and the nurse joined two additional non-Native nurse scientists to form a formal research partnership.

With concerns about Native American elder abuse as a focus, the research team set about developing a community-based participatory research project. The focus of this project was to collect interview data about the perceived magnitude, causes, and forms of elder abuse. In the spirit of reciprocity, the team also wanted to address families' concerns about elders by offering a culturally congruent family conference intervention (Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois, & Weinert, 2004).

Emergence of the Project in the Community

The team designed a project that combined the collection of data with the delivery of a service. Unfortunately, this design is counter to the usual progression of a program of research, which requires documentation of a problem prior to the receipt of funding for piloting an intervention. After some searching, the team received two seed grants from research centers at two colleges of nursing in different states. The simultaneous funding allowed a seamless flow between data collection and piloting the intervention. Subsequently, the team expanded the project to engage two additional communities. The project is at different stages with each of these communities.

Initial Steps and Negotiations

Initially, negotiations began among the research team members in an effort to develop trust and ensure that the equality and unique power of each of the team members would be honored. During this phase, the team discovered the need to build “credibility bridges” (Salois, Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, & Weinert, 2006) between academia and the Native American community and among the members of the research team. It was at this point that the team developed a memorandum of understanding with emphasis on issues such as decision making by consensus, storage and ownership of the data, and cultural review of all project reports (Holkup et al., 2004).

Successes

The Native American research team member has provided insight into respectful cultural norms with regard to community entry. She also made the first contacts with people in the communities. Her negotiations with each of the communities began with a soft entry, through engaging a network of people she has known from various venues: her professional work, former family encounters, and friendships that were forged at boarding schools. After making the initial contacts, the team would request a meeting with community members. Meetings have followed two patterns, with team members as guests or as hosts. As guests, team members often shared in a meal and had a place on the agenda. As hosts, the team members would send a letter of invitation with a brochure describing the project to each prospective participant. Because gracious hospitality requires the sharing of food, the team also made these arrangements. On the day of the meeting, the Native American team member would make a call to each of the invited individuals to check in and see if they were still able to attend. This served as a reminder to the participants in addition to helping the team members understand what currently was happening within the community that might affect the upcoming meeting.

During the initial meeting, the focus of the discussion was on community members' perceptions of need for and their thoughts about the feasibility of the Family Care Conference Project in their community. With each of these initial meetings, there has been overwhelming support for the project. Once the team was able to determine there was support for the project, with community guidance, the team requested letters of support from appropriate community members or agency representatives. These letters were necessary for inclusion with applications for funding and most often have come from service providers who are community members with long-term working relationships in the various community agencies.

Challenges

There has always been the need for flexibility in this project. On one occasion, it was necessary to reschedule a meeting at the last minute because an unforeseen community need took precedence. Although the team had traveled many miles to attend this meeting, responsibilities for community needs were pressing.

In another situation, the representative from a funding source asked for a letter of support from the tribal chairperson. This request threatened the demise of a portion of the project because the request came in the summer months, just prior to the deadline for funding decisions and at a time when the tribal chairperson was away from the community. Although the team was able to obtain a letter of support, it is important to note that, during the long process for scientific review, the makeup of the tribal council changed considerably from the time of first contact with the community, though those people working in the service-providing sectors of the community who had supplied the original letters of support had remained in their positions.

Sensitivity to the current political milieu has been important, as priorities may shift with administrative changes. Progress in one community has halted because the membership of the tribal governing board changed and was no longer supportive of the project. However, because members of the community expressed an interest in the project, the research team hopes there will come a time when the political climate will once again be receptive to the project.

Implementing the Project

Successes

This ongoing program of research at one time involved three communities. In the first community, we hired and trained three community members to serve as facilitators for the Family Care Conference Intervention. The project was so well received in this community that, at the end of funding, one of the tribal human service agencies assumed responsibility for the intervention's continuation. The team provided training for the agency's employees in addition to initial monetary and professional support. The agency director, in turn, agreed to continue to collect data for the project. In the second community, data collection has ended and arrangements are being made to conduct three Family Care Conferences to determine the feasibility of implementing the intervention there. In the third community, as mentioned earlier, progress has stopped.

Challenges

During the portion of the project when three community members served as Family Care Conference facilitators, funding was such that each could be employed quarter-time for a year. With high rates of poverty and unemployment, community members were happy to receive even part-time work; however, during the course of the project, two trained facilitators left when opportunities for full-time work understandably took precedence over the part-time positions. This loss of personnel slowed the momentum of the project, requiring hiring and training new Family Care Conference facilitators.

Evaluating the Process

Throughout this program of research, the research team has kept careful notes of the processes inherent in working across two cultures. Through analysis of these notes, it became apparent that an essential component of building and maintaining relationships with these Native American communities involved the team's approaching their work from a stance of frequent and thoughtful self-reflection and self-critique in an attempt to guard against cross-cultural misunderstandings and/or misinterpretations. Working from this perspective has helped to dismantle power imbalances and maintain equitable power dynamics, which have promoted the development of mutually beneficial relationships among members of the scientific and tribal communities (Holkup et al., 2004; Hunt, 2001; Salois et al., 2006; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Project 3: Motivational Interviewing to Promote Sustained Breast-Feeding: Native American Women

Impetus and Opportunities

The opportunity for this research project was built on a prior relationship (see lower-right-hand corner of Figure 1) that was established through the efforts of the primary investigator of the asthma screening project. The coinvestigator of this project visited the Tribal Epidemiology Center, and this provided the occasion to meet with the Healthy Start (HS) program director. The director discussed the HS goals for increasing breast-feeding rates and discussed obstacles to breast-feeding for this population of mothers. She requested further information about strategies to increase breast-feeding initiation.

After this initial encounter, the investigator was asked to provide breast-feeding workshops. Two workshops were conducted in collaboration with HS community coordinators and case managers from all of the Midwestern tribal communities. The HS staff members were expected to learn the benefits of breast-feeding babies at the first workshop and how to assist mothers with problems at the second workshop. The HS mothers encountered barriers to successful breast-feeding that included lack of expert breast-feeding support in several of the reservations, often a lack of peer support for breast-feeding, some concerns about privacy, and stopping of breast-feeding because of a perceived insufficient milk supply.

Emergence of the Project in the Community

The university sponsored a competitive minority health opportunity grant, and this study was one of the projects selected. Negotiations then began with the HS director about the potential support for this project within the tribal communities. A quasi-experimental design was selected for this study to prevent within-group contamination, with one small rural Native American community selected as the primary intervention site. Another site was chosen as the “infant safety attention intervention” site. The HS director expressed concern about members of each community receiving the same opportunities for training, so it was offered at both sites on completion of study recruitment. The two sites were considered for the study because they would most likely meet the required number of nursing mothers and all had a high incidence of automobile accidents. Care was taken to identify a site that had high rates of accidents so that the members of the community chosen would benefit greatly from the “attention infant safety intervention.” The HS program also wanted to be certain both intervention plans empowered mothers to make their own choices. The motivational interviewing intervention was chosen partially because it is a client-centered strategy.

Initial Steps and Negotiations

Once the grant was funded, a project assistant was hired by the research partner; this person was shared with another research project and worked in the partner's central office. However, she happened to be from one of the study communities. This woman, who had breast-fed her children, said she was excited about helping other mothers breast-feed and was helpful in providing feedback about the development of culturally appropriate study materials.

Meeting with tribal health boards was a very positive cultural experience for the university research team members. Food was provided, and one of the health board members was invited to say a prayer before the meeting began, as is the custom in this Native American tribal community. Because the university team traveled a long distance to meet at one of the study sites, the chairman gathered a quorum to vote on the resolution to approve the breast-feeding project so the university team members would not have to return a second time for this particular issue. The university research team appreciated this consideration as the breast-feeding project had not been a priority on the tribal council's agenda. Tribal health board members at both sites expressed concern about the protection of the data relative to the study and wanted assurances related to accessing the findings. They also were quite concerned about maintaining confidentiality in publications. The university research team members made a commitment to return to these groups (the tribal health boards and the HS program sites) with a report following the completion of the study. However, time passed and turnover in staffing occurred, so the local team members will be different on completion of the study.

Implementing the Project

The two tribal communities were selected as either the intervention group or the attention intervention group to prevent within-group contamination as members of tribal communities generally know each other and interact regularly. Because the local research team members, the HS case managers, had not been previously involved in research, they needed to complete the human participant training. The university team members provided support during this training session. Struggles with the technology and the complexity of the material made this session a challenge for the university and local team members. At a later date, the university research team provided training for data collection and interventions for the local research team members as a whole, and then this training was reinforced at each site. These sessions offered rich opportunities for team building and allowed all members of the research team to get to know each other. The use of humor and university team member vulnerability about past challenges with data collection was essential to relieve tensions as all people strove to do their best.

Evaluating the Process

One of the successes of this study was identifying a project that was important to women who are leaders in promoting the health of infants. Because the HS director and staff had decided that promotion of breast-feeding was important to the success of HS program goals, they were receptive to learning the research protocol. However, the challenge of maintaining continuity in the research project posed difficult problems. There was a change of HS staff (research assistant and one of the HS study site community coordinators) during the implementation of the study, so those two new HS personnel had to be oriented to the study. Therefore, continuity of resources became an issue in terms of limited time and money to orient new personnel. The local research team members diligently recruited mothers to be in the study; however, the study criterion to exclude teen mothers limited their ability to recruit participants in a timely fashion. Because of this, they had to go outside HS mothers to find study participants.

Their apparent dedication to helping mothers that they cared for in the HS program was very evident and humbling. Both the HS program staff and the university research team learned that even a small study in a tribal community takes a great deal of time for the preliminary approval requirements and that circumstances beyond the control of anyone, such as the loss of trained staff, can also affect the progress of the study. Mutual trust and respect are essential to unchallenged implementation and outcome reports, so the time and effort spent in building that trust and respect are as important as adherence to protocols.

Project 4: Methylmercury

Impetus and Opportunities

The development of this academia-initiated study (see lower-left-hand corner of Figure 1) resulted from questions raised by researchers regarding the unknowns of methylmercury risk awareness and potential exposure of Native American childbearing women through fish consumption. Efforts to inform the public of methylmercury risks have existed since the early 1990s. However, considerable evidence indicates that fish advisory messages distributed through angler licenses may not have reached vulnerable populations (Anderson et al., 2004). Native Americans fish on home reservations and are exempt from licensing requirements and therefore may not receive standard fish advisory messages distributed through license brochures.

Initial Steps and Negotiations

Participants for this study were recruited through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for the Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC) on one reservation. The administrator of the WIC Program, a respected tribal member, served as the primary consultant on issues critical to the success of the project. As emissary to the tribal council, the consultant placed the request to conduct the research on the council agenda, monitored the status of the item, and then attended the tribal council meeting to present and advocate for the proposed research study once the agenda item was scheduled. The research team experienced a 2-month delay between repeated agenda-item requests and approval of the research project when more pressing issues were considered by the council. Pacing of this project was shaped in part by a series of tribal events that took precedence over the research approval request.

The course of the study from formulation of the aims through project completion involved partners representing a variety of perspectives and directives. The interdisciplinary research team received funding from the Center for Research of Chronic Health Conditions in Rural Dwellers. The team consulted with and was advised by state agency representatives from Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks; the Department of Environmental Quality; and the Department of Public Health and Human Services (Environmental Health, Health and Consumer Safety, and the WIC Program). This particular tribal community was chosen based on an existing relationship between research team members and tribal acquaintances. However, established trust can be easily squandered when pressures mount to achieve a research goal. Understanding the urgency embedded in academic culture, often the antithesis of tribal community perspective, requires balancing a respect for pacing differences and finding common ground for initiating, maintaining, and completing a project.

Emergence of the Project in the Community

Investigating health disparities (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000) on an environmental issue in a tribal community requires knowledge of the people and a specific plan for developing participatory approaches with local community members (Jardine, 2003). In Native American communities, for instance, using a scientific expert and/or hierarchical scheme that fails to incorporate local knowledge and cultural beliefs is rarely an effective method for assessing risk or implementing change (Arquette et al., 2002; Poupart, Martinez, Red Horse, & Scharnberg, 2000). Indigenous and dominant cultures approach decision making and communication of important messages in strikingly different ways. Risk assessment in tribal communities requires flexibility, collaboration, and respect for points of view that might come from the admonition of an elder rather than the data of a scientific expert (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2000; Bird, 2002; Cajete, 1994; Colomeda-Lambert, 1999).

Implementing the Project

Project implementation included a review of a fish consumption and advisory awareness tool (Anderson et al., 2004). Reconstruction of this tool was based on recommendations from tribal elders and included deletion of questions, language changes, and inclusion of pictures and images to enhance survey appropriateness and interest. Once finalized and evaluated for time burden, the computerized survey was placed on a secure Web site using Snap survey software. To overcome reading level and computer skill differences among participants, a tribal research assistant was trained to administer the survey to participant volunteers recruited by WIC personnel during their regularly scheduled visit. After the survey, all participants were thanked for their time, educated regarding safe fish consumption, and given a gift certificate by the research assistant.

When research questions emanate from academia, project importance at the community level may hold less significance and urgency. With the tribal community overwhelmed by a variety of pressing health concerns, a slow-motion environmental threat with few outward or immediately apparent sequelae may fail the priority test. Timing of this particular study coincided with a high number of youth alcohol-related deaths on the reservation. Researchers were challenged by the ticking clock that counted down the research window available for conducting the study. Although flexibility, collaboration, and respect are elements critical to a project's success in a tribal community, a collision of academic and tribal cultures related to timing can become a reality and an impediment to success.

Evaluating the Process

Project completion and the successful negotiation of the tribal landscape with the invaluable help of a tribal consultant and local health professionals including the WIC staff provided an opportunity for reflection. First, suggestions for simplifying the survey language received from tribal elders and tribal members contributed significantly to reducing the complexity of the methylmercury survey. Second, the gift cards not only helped team members demonstrate appreciation to survey participants but also attracted additional WIC clients who heard about and came to their WIC appointment ready to participate in the survey. Finally, the goal of achieving a mutually balanced and beneficial relationship is reached only when values and beliefs of both the research team and the tribal community are observed. Lessons learned from this academia-initiated project on one reservation may not necessarily apply to another reservation, but the experience of patiently traversing the tribal landscape with respect and humility is irreducible.

Lessons Learned

Through our collective experience with four distinct tribal communities, we have learned valuable lessons to share with others who might have the opportunity to conduct research with Native American people. The lessons we learned are related to the importance of relationship, reciprocity, project relevance, and negotiations of cultural and political differences among the three entities.

Importance of Relationships

As identified in the model and described in the project stories, each of the projects had different beginnings depending on which of the three entities (academia, nursing science, and tribal communities) was the source of the project focus and project initiation. Relationships, of varying degrees of formality and informality, played an important role in the inceptions of these projects, as delineated in the project descriptions. Although the beginnings of each project differed considerably, the importance of relationships in these research endeavors was underscored from the beginning (Rogers & Petereit, 2005). Keeping relationships as the highest priority maintained the mutual integrity of the research partnership and helped guard against the potential for the research projects to be experienced as fragmented and depersonalizing.

The Value of Reciprocity

A key aspect necessary to the establishment of the projects in the communities involved adhering to the value of reciprocity. This is a ubiquitous norm in interdependent Native American communities. Coming from the context that research has sometimes been oppressive to tribal people, it was important for members of the communities, who were giving of their time and experiences to the various projects, to see how these research projects would directly benefit their communities. Identifying the benefits was also important to the integrity of the nurse scientists who wanted to respect and participate in this norm of reciprocity.

Project Relevance

Related to the value of reciprocity, another critical aspect necessary to the acceptance of each of the projects in the communities was the relevance of the research. With the focus of the research projects coming from different sources, the members of the communities who were to be involved in the projects could perceive the relevance of the projects differently from those who originally conceived the project. Use of a community-based participatory approach allowed for the dialogue necessary to understand what was desired within the communities, how the current projects would be perceived, and what needed to be changed (Burhansstipanov et al., 2005).

It was important to balance articulation of the benefits of the project with sensitivity to the current environment in any community. Events such as a ceremony, the death of a tribal leader, or a community-wide conference could take immediate precedence over any aspect of a project. We recognized and respected this ordering of priorities, such as putting family and community needs first, as a tribal strength.

Negotiations of Political and Cultural Differences

Activities during the beginning stages of each project also focused on negotiation of cultural differences between tribal and academic policies. In addition, working through the bureaucratic structures of the academic IRB, the tribal council, and the IHS IRB was a time-consuming process. Challenges related to institutional policies were most apparent in the manner in which they affected issues of time and the window of funding.

Political differences between the academic institution and tribal communities were addressed in a careful negotiation of control over the research project. Questions of ownership of the data were addressed, as were concerns related to the prevention of cross-cultural misinterpretation of the results of the projects. Members of the academic community felt responsible because of the potential for legal ramifications. Tribal leaders felt responsible in allowing the projects to be conducted in their communities because of tribal vulnerabilities. Given the dynamic heritages of academic, scientific, and tribal communities, it was also important for us to recognize that project entrée issues sometimes simply were predicated on personality and current political agendas within the three entities.

Summary

Conducting research with Native American communities involves complexities that are not present when conducting research in the dominant culture. Negotiations must be navigated among three dynamic entities, all with their own powerful political milieus: academia, nursing science, and tribal communities. Challenges may differ, depending on how the focus of the project is derived and who initiates the project. Critical to community entrée is taking the time and making the effort to build rapport and establish trusting relationships between nurse scientists and the community. Honoring the value of reciprocity encourages a mutually beneficial experience for tribal communities and researchers. It is hoped that the lessons learned in these four research projects may be instructive to nurse scientists who wish to conduct research with tribal communities.

Acknowledgments

Author's Note: The authors would like to acknowledge the following support for components of the research presented here. Project 1: Screening Native American Children for Asthma, IHS: U26IHS300002-01/NIH:1S06GM074082-01 (Research Team: Rodehorst, Wilhelm, & Stepans); Project 2: Caring for Native American Elders, NINR P30 NR003979, NINR P20 NR07790, NINR R21 NR008528, NINR R03 NR09282-A1, John A. Hartford Foundation's Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Program (Holkup, Salois, Toni Tripp-Reimer, & Weinert); Project 3: Motivational Interviewing to Promote Sustained Breastfeeding: Native American Women, Minority Health Research Seed Projects [MIHERO] (Wilhelm, Rodehorst, & Stepans); Project 4: Methylmercury Risk Awareness Project, NINR P20 NR07790 (Kuntz, Wade G. Hill, Susan King, Jeff W. Linkenbach, & Gary M. Lande).

Contributor Information

Patricia A. Holkup, Montana State University.

T. Kim Rodehorst, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Susan L. Wilhelm, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Sandra W. Kuntz, Montana State University.

Clarann Weinert, Montana State University.

Mary Beth Flanders Stepans, Wyoming State Board of Nursing.

Emily Matt Salois, Montana State University.

Jacqueline Left Hand Bull, Aberdeen Area Tribal Chairmen's Health Board.

Wade G. Hill, Montana State University.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Working effectively with tribal governments. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Indian Law Center. Model tribal research code. 3rd. Albuquerque, NM: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H, Hanrahan L, Smith A, Draheim L, Kanarek M, Olsen J. The role of sport-fish consumption advisories in mercury risk communication: A 1998-1999 12-state survey of women age 18-45. Environmental Research. 2004;95:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arquette M, Cole M, Cook K, LaFrance B, Peters M, Ransom J. Holistic risk-based environmental decision making: A Native perspective. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110(Suppl 2):259–264. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird M. Health of indigenous people: Recommendations for the next generation. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(9):1391–1392. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L, Christopher S, Schumacher A. Lessons learned from community-based participatory research in Indian country. Cancer Control. 2005 November;:70–76. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajete G. Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education. Durango, CO: Kivaki Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carson DK, Hand C. Dilemmas surrounding elder abuse and neglect in Native American communities. In: Tatara T, editor. Understanding elder abuse in minority populations. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Colomeda-Lambert L. Keepers of the central fire: Issues in ecology for indigenous peoples. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson JE, Struthers R. Indigenous women's voices: Marginalization and health. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2005;16:339–346. doi: 10.1177/1043659605278942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with a Native American community. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(3):162–175. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM. Beyond cultural competence: Applying humility to clinical settings. Park Ridge Center Bulletin. 2001;24:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine C. Development of a public participation and communication protocol for establishing fish consumption advisories. Risk Analysis. 2003;23(3):461–471. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Garroutte E, Goins RT, Henderson PN. Access, relevance, and control in the research process. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(5):58S–77S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard E. The growing negative image of the anthropologist among American Indians. Human Organization. 1974;33:402–403. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell TL, Baker E. Community-building versus career-building research: The challenges, risks, and responsibilities of conducting research with Aboriginal and Native American communities. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(1):41–46. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):856–860. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poupart J, Martinez C, Red Horse J, Scharnberg D. To build a bridge: An introduction to working with American Indian communities. St. Paul, MN: American Indian Policy Center; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, McDonald J, Bell RA, Arcury TA. Aging research in multi-ethnic rural communities: Gaining entree through community involvement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:113–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1006625029655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse J, Johnson T, Weiner D. Commentary: Cultural perspectives on research among American Indians. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 1989;13(34):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse JG. American Indian elders: Unifiers of Indian families. Social Casework: Journal of Contemporary Social Work. 1980a;61(8):490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse JG. Family structure and value orientation in American Indians. Social Casework: Journal of Contemporary Social Work. 1980b;61(8):462–467. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D, Petereit DG. Cancer disparities research partnership in Lakota country: Clinical trials, patient services, and community education for Oglala, Rosebud, and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(12):2129–2132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salois EM, Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Weinert C. Research as spiritual covenant. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;28(5):505–524. doi: 10.1177/0193945906286809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard B. Breastfeeding management and promotion among Native Americans in Wisconsin; Paper presented at the Indian Health Service Conference; Minneapolis, MN. 1997. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project. A gathering of wisdoms: Tribal mental health: A cultural perspective. 2nd. LaConner, WA: Swinomish Tribal Community; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom-Orme L. Research and American Indian/Alaska Native health: A nursing perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006;17(3):261–256. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver HN, White BW. The Native American family circle: Roots of resiliency. Journal of Family Social Work. 1997;2(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]