Abstract

The cattle tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus, is a major threat to the improvement of cattle production in tropical and subtropical countries worldwide. Bos indicus cattle are naturally more resistant to infestation with the cattle tick than are Bos taurus breeds, although considerable variation in resistance occurs within and between breeds. It is not known which genes contribute to the resistant phenotype, nor have immune parameters involved in resistance to R. microplus been fully described for the bovine host. This study was undertaken to determine whether selected cellular and antibody parameters of the peripheral circulation differed between tick-resistant Bos indicus and tick-susceptible Bos taurus cattle following a period of tick infestations. This study demonstrated significant differences between the two breeds with respect to the percentage of cellular subsets comprising the peripheral blood mononuclear cell population, cytokine expression by peripheral blood leukocytes, and levels of tick-specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibodies measured in the peripheral circulation. In addition to these parameters, the Affymetrix bovine genome microarray was used to analyze gene expression by peripheral blood leukocytes of these animals. The results demonstrate that the Bos indicus cattle developed a stabilized T-cell-mediated response to tick infestation evidenced by their cellular profile and leukocyte cytokine spectrum. The Bos taurus cattle demonstrated cellular and gene expression profiles consistent with a sustained innate, inflammatory response to infestation, although high tick-specific IgG1 titers suggest that these animals have also developed a T-cell response to infestation.

The cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus is a major threat to the improvement of cattle production in tropical and subtropical countries worldwide. Heavy tick infestation has adverse physiological effects on the host, resulting in decreased live weight gain (21), and anemia is a common symptom of heavy infestation (35). R. microplus is also the vector of Babesia bovis, Babesia bigemina, and Anaplasma marginale, which cause tick fever in Australia. Acaricide treatment is the primary method of controlling ticks; however, populations of ticks have subsequently developed resistance to organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates, amidines, and synthetic pyrethroids (27). Resistance to multiple classes of chemicals has also been observed (27). It is probable that with current usage new acaricides will encounter similar problems (10), and a more sustainable solution to tick control is needed.

Naturally acquired host immunity has been proposed as a viable cattle tick control method because of the potential reduction in expenditure on acaricides and husbandry practices associated with chemical control (10). Bos indicus cattle breeds are more resistant to R. microplus than are Bos taurus breeds, although considerable variation in resistance occurs between and within breeds (37, 45). Although innate immunity arising from genetic differences between B. indicus and B. taurus breeds forms the basis of whether an animal will be resistant to tick infestation, host resistance is considered to be predominantly an acquired trait because the higher level of resistance seen in B. indicus becomes apparent only following a period of initial susceptibility to primary infestation (15, 44). Host resistance to tick infestation is heritable, with a rate estimated to be between 39% and 49% for British breed animals (45) and as high as 82% in Africander and Brahman (B. indicus) crossbred animals (37). Since these initial studies, it has been shown that the resistance status of both B. taurus and B. indicus breeds can be improved by selection for increased tick resistance, as demonstrated by a breeding program that has resulted in a highly tick-resistant line of Hereford × Shorthorn (B. taurus) cattle, now known as the Belmont Adaptaur (9, 25). Identifying the mechanisms responsible for mediating naturally acquired tick resistance in cattle is an essential step in developing predictive phenotypic markers to enable rapid identification of highly resistant individuals and is potentially useful in the development of a tick vaccine. It is not known, however, which genes contribute to the resistant phenotype, nor have immune parameters involved in resistance to R. microplus been fully described for the bovine host.

Studies of immune parameters of the peripheral circulation of tick-infested cattle have yielded varied and sometimes conflicting results. Cattle tick infestation has been reported to reduce the number of circulating T lymphocytes and the antibody response to ovalbumin injection in susceptible B. taurus animals compared to tick-free control animals (17). In another study, infestation with several species of African ticks resulted in higher levels of serum gamma globulin and increased numbers of circulating white blood cells (WBCs) in B. taurus animals compared with those in Brahman cattle managed under the same conditions (33). Exposure of animals to high and low levels of tick infestation has been reported to result in differential patterns of immunoglobulins specific for tick salivary proteins in resistant and susceptible cattle (7, 24). Sustained heavy infestation has been shown to alter host hemostatic mechanisms by inhibiting platelet aggregation and coagulation functions (34) and also by altering the level of acute-phase proteins in the susceptible host (4).

In vitro studies of mononuclear cell populations have shown that salivary gland proteins from R. microplus can inhibit immune cell function. The proliferative response of bovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to stimulation with the T-lymphocyte mitogen phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was inhibited by the addition of salivary gland protein to the culture (17), and subsequent studies showed that sufficient prostaglandin E2 is present in tick saliva to be responsible for this inhibition (16). Turni et al. (42) found that low concentrations of R. microplus salivary gland extract (SGE) inhibited the oxidative burst capacity of monocytes and neutrophils, as well as the proliferation response of PBMC to concanavalin A (ConA) in vitro, in both B. taurus and B. indicus cattle. However, a higher concentration of SGE caused a significant difference in the degree of inhibition observed in the proliferation assay between the B. taurus and B. indicus cells: a 40.7% and an 88.5% reduction, respectively. The authors suggested that the disproportionate increase in inhibition at the higher concentration of SGE may be an indication that the mechanisms by which the two breeds resist infestation are different.

Here we report the results of a study undertaken to define selected immune parameters in tick-resistant Brahman and tick-susceptible Holstein-Friesian animals following challenge infestations with R. microplus. The aim of this study was to determine whether cellular and antibody components of the peripheral circulation differed between these two breeds of highly divergent resistance following a period of tick infestations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatment.

Six Holstein-Friesian (B. taurus) and six Brahman (B. indicus) heifers aged 6 months (±1 month) that had been previously vaccinated against the tick fever-causing organisms Babesia bovis, B. bigemina, and Anaplasma marginale were used in this trial. Both groups originated from tick-infested areas of Australia, and consequently all animals had previously been exposed to R. microplus in the field prior to the commencement of this study. Infestation and tick counting procedures performed on these animals have been previously described (31). Briefly, cattle were artificially infested weekly for 7 weeks with approximately 10,000 (0.5 g) R. microplus larvae applied to the neck and withers. Animals were simultaneously exposed to ticks under natural conditions in tick-infested pastures. The larvae used to artificially infest the cattle were of the Non-Resistant Field Strain (NRFS) (40), which is maintained free of tick fever-causing organisms at Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries in Brisbane, Australia. Larvae were maintained at 28°C and approximately 95% humidity and applied to animals 7 to 14 days after hatching. Standard tick counts were undertaken weekly, for 7 weeks, as described by Utech et al. (43). An analysis of variance of tick side counts was performed using Minitab (Student version 14) to show that the two breeds differed in their abilities to resist tick infestation. All animals in the trial were managed under the same conditions in the same paddock for several months prior to the commencement of the trial and for the duration of the trial. Weekly blood samples were obtained via jugular venipuncture for 3 weeks during the period of artificial infestations. EDTA, lithium heparin, and Z clot activator Vacuette blood tubes (Greiner Bio-One) were used for the collection of blood.

Hematology.

A hematology report was obtained for blood samples collected in EDTA Vacutainers using a VetABC animal blood cell counter (ABX Hematologie). The hematology report included counts of whole WBCs and red blood cells (RBCs), hemoglobin levels, platelets, packed cell volume, mean corpuscular volume, and mean cell hemoglobin concentration.

Flow cytometry.

Blood collected in EDTA (100 μl) was combined with 100 μl of either a monoclonal antibody (Table 1) or an isotype control (mouse immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min, after which RBCs were lysed with 2 ml of RBC lysing buffer (0.19 M NH4Cl2, 0.01 M Tris, pH 7.5, containing 1% NaN3). Tubes were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and all samples were washed with 2 ml of cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% NaN3 before being centrifuged again at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was again discarded. The secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG preadsorbed with bovine IgG conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was diluted 1/100 in PBS containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% NaN3. Fifty microliters of diluted secondary antibody was added to all tubes and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Samples were washed with PBS containing 1% NaN3 as before, and the supernatant was discarded. Each sample was resuspended in 200 μl of fixative (PBS containing 1% NaN3 and 8% formaldehyde). Samples were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data from 10,000 cells per sample were acquired using an argon laser with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Forward scatter light data were acquired using a linear amplifier, and side scatter light data were acquired with a logarithmic amplifier. Data analysis was performed using the commercially available software Cell-Quest (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems). Gates for analysis were set around the PBMC population on a dot plot of forward angle versus side angle light scatter. Labeled lymphocyte populations were analyzed using a histogram for fluorescein fluorescence, and a threshold marker was set at the upper 0.5% of the isotype-labeled control population for each biological sample. Results are presented as the percentage of PBMC that emitted fluorescence above that of the negative population.

TABLE 1.

Monoclonal antibodies used in flow cytometric analysis of cellular subsetsa

| Specificity | Identity | Source | Isotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotype control | IgG1 | Dako | IgG1 |

| CD4 | IL-A11 | Cell culture | IgG2a |

| CD8 | IL-A51 | Cell culture | IgG1 |

| CD14 | MM61A | VMRDb | IgG1 |

| CD25 (IL-2Rα) | IL-A111 | Cell culture | IgG1 |

| CD45RO | IL-A150 | Cell culture | IgG3 |

| MHCII | IL-A21 | Cell culture | IgG2a |

| WC3 | CC37 | Cell culture | IgG1 |

| WC1 | IL-A29 | Cell culture | IgG1 |

| Goat anti-mouse | IgG-FITC | Calbiochem | IgG1 |

Monoclonal antibodies obtained from cell culture were derived from hybridomas sourced from the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya.

VMRD, Veterinary Medical Research and Development, Inc.

Tick antigen extraction.

Approximately 500 semiengorged adult female ticks (NRFS) (40) were removed from penned B. taurus cattle at Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries for preparing tick antigen extracts. Tick dissection was carried out within 12 h of removal of the tick from the host. Ticks were dissected while submerged in PBS, and gut and salivary glands were removed into separate vials on dry ice before being stored at −70°C prior to antigen extraction. To extract whole adult female and larval antigens, semiengorged NRFS adult females and unfed NRFS tick larvae, respectively, were ground up using a mortar and pestle on dry ice and then stored at −70°C prior to antigen extraction. EDTA was added to dissected organs and ground-up tissue prior to freezing to remove divalent cations that contribute to proteolysis. Antigen extraction was performed using the method described previously by Jackson and Opdebeeck (20). Briefly, this method employs a series of centrifugation steps to separate proteins into membrane-bound and soluble fractions, and the resulting antigen extractions included salivary gland membrane (SM), larval membrane (LM), gut membrane (GM), adult membrane (AM), salivary gland soluble (SS), larval soluble (LS), gut soluble (GS), and adult soluble (AS) antigen extracts.

Cellular proliferation assay.

PBMC for the proliferation assays were isolated from 10 ml blood collected in lithium heparin Vacuette tubes. Blood was mixed with 8 ml of PBS, layered onto 8 ml of Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Sydney, Australia), and centrifuged at 500 × g for 40 min at 22°C. Cells at the interface of the Ficoll-Paque and PBS were removed, added to 8 ml of RBC lysing buffer (0.19 M NH4Cl2, 0.01 M Tris, pH 7.5), and incubated at room temperature for 10 min before being centrifuged at 250 × g for 10 min at 22°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended and washed twice in PBS. Cells were resuspended to 8 × 106 cells/ml in complete medium; RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco). The proliferation assay was set up in 96-well flat-bottomed cell culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany), and assays were performed in triplicate. Each experimental well contained 4 × 105 cells with either ConA, PHA, soluble fractions of semiengorged adult female ticks (AS) or larvae (LS), or membrane fractions of semiengorged adult female ticks (AM) or larvae (LM). ConA and PHA were diluted in complete medium to 5 μg/ml and 20 μg/ml, respectively, and dispensed at 100 μl per well. LM and AM tick antigens were diluted to 10 μg/ml in complete medium, while LS and AS antigens were diluted to 20 μg/ml in complete medium, and each was dispensed at 100 μl per well. Control wells contained either medium only or cells plus medium, and all wells were made up to a final volume of 200 μl with complete medium. The plates were incubated with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 5 days. Subsequently, 20 μl of bromodeoxyuridine was added to all wells, and the plates were incubated with 5% CO2 at 37°C overnight. The cellular proliferation was measured using a cell proliferation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) bromodeoxyuridine (colorimetric) kit (Roche Diagnostics, Sydney, Australia) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Optical densities (ODs) were measured using a microplate reader at 450 nm in conjunction with the SoftmaxPro computer software. The mean OD of each biological sample from triplicate wells was employed for statistical analyses.

Tick-specific IgG antibody levels measured by ELISA.

Serum samples collected from cattle over the 3-week period were used in an indirect ELISA to measure tick-specific IgG1 and IgG2 antibody levels. For the IgG1 ELISA, tick antigens SM, GM, and LM were diluted to 7.5 μg/ml, 3.5 μg/ml, and 5 μg/ml, respectively, in carbonate buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 and 0.1 M Na2CO3), while SS and LS antigens were diluted to 10 μg/ml. For the IgG2 ELISA, all antigens were diluted to 20 μg/ml. Microtiter plates (Greiner Bio-One) were coated with 100 μl/well of diluted antigen by overnight incubation at 4°C. Excess antigen was discarded, and plates were blocked with 200 μl of carbonate buffer containing 1% gelatin. Sera were diluted 1/400 for the IgG1 ELISA and 1/100 for the IgG2 ELISA in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and added to triplicate wells for each biological sample. Control wells contained either PBS-T, known positive serum, or known negative serum. The monoclonal antibody (mouse anti-bovine IgG1 or IgG2; AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) was diluted 1/100 in PBS-T and added to all wells. The conjugated antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG heavy and light chain specific, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase; Calbiochem) was diluted 1/2,000 in PBS-T, and 100 μl was added to each well. A tetramethylbenzidine-peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Maryland) was used to develop the signal, and the reaction was stopped with 50 μl 2 Μ orthophosphoric acid. The absorbance was read at 450 nm. The mean OD of each biological sample from triplicate wells was employed for statistical analyses.

Isolation of RNA from WBCs.

Five milliliters of blood collected into EDTA was added to 45 ml of RBC lysing buffer and allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were then spun at 250 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. The cell pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and samples were stored at −70°C prior to RNA extraction. Extraction of total RNA was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions for Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). The RNA pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of RNase-free water, treated with 0.75 μl of Turbo DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and further purified using RNeasy minicolumns (Qiagen, Melbourne, Australia). RNA was stored at −80°C until required.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of selected cytokines.

cDNA synthesis was performed using 2 μg of total RNA. The complementary strand was primed with OligoDT primers (Invitrogen), and cDNA synthesis was performed using a Superscript III kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out in a final volume of 12 μl containing 20 ng cDNA, 5.8 μl Sensimix Plus Sybr Master Mix (Quantace, Sydney, Australia), and gene-specific primers. Most primer sets used in the real-time PCRs for the analysis of cytokine and chemokine expression have been published elsewhere (6, 41), but for ease of reference they are listed in Table 2. Those primer sets that have not previously been published were designed using the Primer3 software available at http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/. The specificity of the primers was checked using melting curve analysis, and standard curves were generated for each primer pair to obtain the amplification efficiency. qPCR for each biological sample was performed in triplicate using standard cycling conditions on a Rotorgene 6000 (Corbett). For each biological sample, the mean of the cycle threshold values for each gene was calculated and normalized against two internal controls, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and acidic ribosomal protein large, P0, using the QGene software available at http://www.qgene.org/. This software expresses the result in the form of the mean normalized expression ± standard error (37a), and this value was employed for statistical analysis.

TABLE 2.

Genes analyzed via quantitative real-time RT-PCRa

| Gene name | NCBI accession no. | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPLP0 | BT021080 | 5′ CAACCCTGAAGTGCTTGACAT 3′ | 5′ AGGCAGATGGATCAGCCA 3′ |

| GAPDH | NM_001034034 | 5′ CCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGT 3′ | 5′ GCCAAATTCATTGTCGTACCA 3′ |

| IL-1β | NM_174093 | 5′ AAATGAACCGAGAAGTGGTGTT 3′ | 5′ TTCCATATTCCTCTTGGGGTAGA 3′ |

| IL-2 | NM_180997 | 5′ GTGGAAGTCATTGCTGCTGGA 3′ | 5′ GGTTCAGGTTTTTGCTTGGA 3′ |

| IL-2Rα | NM_174358 | 5′ TGCTAAGAGCATCCCGACTT 3′ | 5′ TAGCTTGGAGGACTGGGCTA 3′ |

| IL-4 | NM_173921 | 5′ CATTGTTAGCGTCTCCTGGTA 3′ | 5′ GCTCGTCTTGGCTTCATTC 3′ |

| IL-6 | NM_173923 | 5′ CTGGGTTCAATCAGGCGAT 3′ | 5′ CAGCAGGTCAGTGTTTGTGG 3′ |

| IL-8 | NM_173925 | 5′ CTGTGTGAAGCTGCAGTTCT 3′ | 5′ ATGGAAACGAGGTCTGCCTA 3′ |

| IL-10 | NM_174088 | 5′ CTTGTCGGAAATGATCCAGT 3′ | 5′ TCTCTTGGAGCTCACTGAAG 3′ |

| IL-12 | EU276075 | 5′ AACACGCCCCATTGTAGAAG 3′ | 5′ AAGCCAGGCAACTCTCATTC 3′ |

| IL-18 | NM_174091 | 5′ AGCACAGGCATAAAGATGGC 3′ | 5′ TGGGGTGCATTATCTGAACA 3′ |

| TNF-α | EU276079 | 5′ CTGGTTCAGACACTCAGGTCCT 3′ | 5′ GAGGTAAAGCCCGTCAGCA 3′ |

| IFN-γ | FJ263670 | 5′ GTGGGCCTCTCTTCTCAGAA 3′ | 5′ GATCATCCACCGGAATTTGA 3′ |

| CXCL-10 | NM_001046551 | 5′ AGTGGAAGCCCCTGCAGTAAA 3′ | 5′ AGTCCCAGCCTTGCTACTGACA 3′ |

| CCR-1 | NM_001077839 | 5′ CTGCTGGTGATGATTGTCTG 3′ | 5′ TGCTCTGCTCACACTTACGG 3′ |

| CCR-3 | AY574996 | 5′ GATGGGATTGAAACTGTGGG 3′ | 5′ GGCAGCGTGAATAGGAAGAG 3′ |

Gene names and NCBI accession numbers are listed with forward and reverse primer sequences (5′ to 3′). RPLP0, acidic ribosomal protein large, P0; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IFN-γ, gamma interferon.

Statistical analysis of cellular and antibody parameters.

A one-way analysis of variance was performed using Minitab (Student version 14) for the fixed effect of breed for each of the cellular and antibody parameters measured above. The dependent variable used for the analysis was the mean of the three weekly observations for each animal in each group, as it was confirmed that week did not have a significant impact on any of the variables using the general linear model (Minitab, Student version 14).

Microarray data.

Transcription profiling of the RNA extracted from WBCs of the three Brahman and three Holstein-Friesian animals was conducted using the Affymetrix GeneChip bovine genome array platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). This expression array contains 24,128 probe sets representing 11,255 gene identities from Bos taurus build 4.0 and 10,775 annotated UniGene identities plus 133 control probes. The experiment was designed to be compliant with standards for minimum information about a microarray experiment. Each RNA sample was processed and hybridized to individual slides; target preparation and microarray processing procedures were carried out by the Australian Genome Research Facility, Melbourne, Australia, as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip expression analysis manual (Affymetrix), and scanning was performed with an Agilent microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Microarray data preprocessing.

All quality control measures, preprocessing, and analyses were performed using the statistical computing language R (32) and Bioconductor (13). The quality of the arrays was assessed through standard quality control measures for Affymetrix arrays: pseudoimages of the arrays (to detect spatial effects), MA scatter plots of the arrays versus a pseudomedian reference chip, and other summary statistics including histograms and box plots of raw log intensities, box plots of relative log expressions, box plots of normalized unscaled standard errors, and RNA degradation plots (3). All arrays were within normal boundaries (see the supplementary analysis file available through the microarray data accession number for the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO] site).

Transcription intensities in log2 scale were estimated from the probe-level data by using three summarization methods: MAS5.0 (1) with the R affy package (11), RMA (18, 19), and GCRMA (46). Briefly, for MAS summarization, the background was corrected and each probe was adjusted using a weighted average. All arrays were scaled to the same mean value for normalization (200) and were summarized by an adjusted log2 scale average using one-step Tukey biweight. For RMA, the background was corrected by convolution. The data were then quantile normalized and summarized by median polish. GCRMA background correction used an affinity measure model based on probe sequences and mismatch intensities.

MAS generates a detection call, which flags each transcript as present, marginal, or absent (28, 30). Detection calls for the probes were calculated (τ = 0.015, α1 = 0.04, α2 = 0.06) and used as a filtering criterion in the analyses.

Statistical analysis of microarray data.

Statistical analyses were performed following the method used by Rowe et al. (36). Prior to testing for differential expression, the data were filtered to remove Affymetrix control probes (n = 133) and all noninformative probes detected as marginal or absent in all arrays (n = 8,920), thus leaving 15,096 probes to be tested. Differential transcription was tested for each summarization method using LIMMA (38, 39). Only differentially expressed (DE) probes detected in two out of the three summarization methods (P < 0.01) and flagged as present in at least 50% of the samples were considered to be significant. No false discovery rate correction method is warranted due to the stringency of the filtering criteria.

Functional profiling.

Annotation of DE probes was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (8) and an R annotation package derived from the Bos taurus build 4.0. In subsequent text the term “probe” is replaced by “gene.” The DE genes were analyzed in the context of their gene ontology (GO) biological process (12) and KEGG biological pathway (22, 23).

Functional profiles for the DE genes were derived for each of the GO (2) categories: cellular component, molecular function, and biological process. DE genes were mapped from their Entrez identifier to their most specific GO term, and these were used to span the tree structure and test for gene-enriched terms. Unannotated probes were dropped from the analyses. To avoid overinflated P values, the background consisted exclusively of the array probes used in the analyses after removal of control probes, unexpressed probes, and unannotated probes. Profiles for each category were also constructed for the DE genes for different tree depths.

Validation of DE genes.

Eight genes were arbitrarily chosen to validate the microarray estimates using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Validation was performed using RNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes of six Holstein-Friesian and five Brahman animals. Primers used for the validation of genes detected as DE by the microarray analysis were designed using the Primer3 software available at http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR and normalization were carried out using the methods described above. Primers used for the validation of DE genes are listed in Table S2a in the supplemental material.

Microarray data accession number.

The NCBI GEO accession number for the microarray data reported in this paper is GSE13725. Available for download from this GEO accession is a zipped supplementary analysis file containing all preprocessing analyses, annotated lists of DE genes with links to NCBI and Affymetrix, and other relevant images, diagrams, and analyses.

RESULTS

Tick counts.

The Brahman cattle carried significantly fewer ticks (P < 0.001) than did the Holstein-Friesian cattle at all time points when tick counts were undertaken, as previously reported (31). The mean number of ticks observed on the Brahman animals was 15 (±14) per side, while the mean number of ticks observed on the Holstein-Friesian animals was 151 (±36) per side.

Hematology.

A significantly higher (P = 0.002) WBC count was recorded for the Holstein-Friesian animals at each of the three sampling time points; average Holstein-Friesian WBC counts were (13.27 ± 2.26) × 106/ml while average Brahman WBC counts were (10.84 ± 2.16) × 106/ml (Table 3). Significantly higher (P < 0.001) levels of RBCs were recorded for the Brahman animals in each of the three sampling periods; mean Holstein-Friesian RBC counts were (5.47 ± 0.51) × 106/mm3 while mean Brahman RBC counts were (9.25 ± 0.62) × 106/mm3 (Table 3). The Holstein-Friesian animals correspondingly had significantly lower (P < 0.001) hemoglobin levels than did the Brahman animals. These values and other hematological parameters are listed with the respective significance levels in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Hematological parameters measured for Holstein-Friesian and Brahman cattlea

| Parameter (unit) | Value by breed:

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holstein-Friesian | Brahman | ||

| WBC count (103/mm3) | 13.27 ± 1.66 | 10.84 ± 1.88 | 0.002 |

| RBC count (106/mm3) | 5.47 ± 0.51 | 9.25 ± 0.62 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.31 ± 0.80 | 12.99 ± 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit/packed cell vol (%) | 24.98 ± 2.30 | 34.77 ± 2.29 | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (103/mm3) | 445.00 ± 116.53 | 581.39 ± 154.58 | 0.007 |

| Mean corpuscular vol (/μm3) | 45.78 ± 2.28 | 37.67 ± 2.85 | <0.001 |

| Mean cell hemoglobin concn (g/dl) | 37.32 ± 0.47 | 37.48 ± 1.92 | 0.723 |

Results are presented as the breed means of three time points. Means are presented ± standard deviations from the group means together with the P values for test of significant difference between breeds using the one-way analysis of variance.

Flow cytometry.

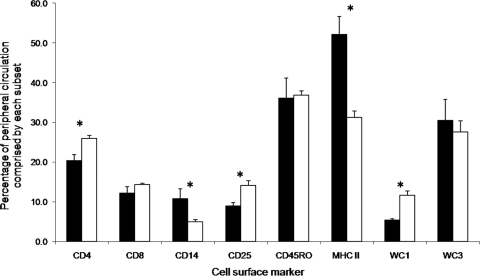

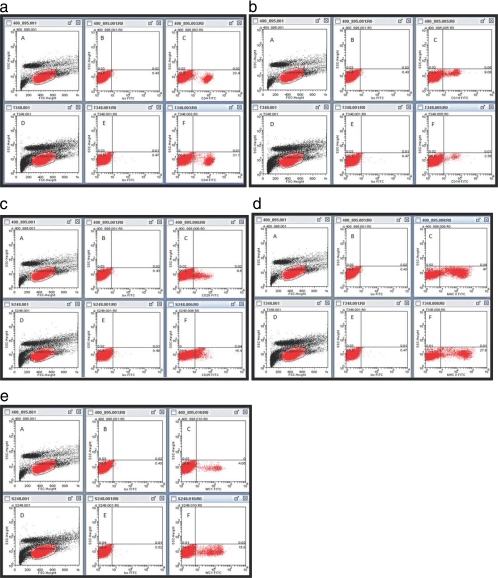

The Brahman animals had significantly higher levels of CD4+ T cells (P < 0.001), activated T cells (CD25+) (P < 0.001), and γδ T cells (WC1+) (P = 0.006) in their peripheral circulation than did the Holstein-Friesian animals (Fig. 1). However, the Holstein-Friesian group presented significantly higher levels of monocytes (CD14+) (P < 0.001) and other cells expressing the major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Figure 2a to e depicts flow cytometry displays of CD4+, CD14+, CD25+, MHCII+, and WC1+ cell populations, respectively, from a representative Holstein-Friesian animal and a representative Brahman animal. No difference was observed between the breeds for the percentages of CD8+ T cells, memory T cells (CD45RO+), or B cells (WC3+) in circulation.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of each cellular subset comprising the PBMC population of Holstein-Friesian (black) and Brahman (white) cattle. Results are presented as the breed means of three time points with standard deviations from the group means. Asterisks denote a significant difference (P < 0.01) between the Holstein-Friesian and Brahman cattle.

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric displays of peripheral blood lymphocytes from a representative Holstein-Friesian animal (subpanels A to C) and a representative Brahman animal (subpanels D to F). (a) CD4+ cells; (b) CD14+ cells; (c) CD25+ cells; (d) MHCII+ cells; (e) WC1+ cells. Dot plots in subpanels A and D depict forward scatter versus side scatter light data. The mononuclear lymphocyte population is gated in red. Subpanels B and E depict the isotype-labeled lymphocyte population on a dot plot of FITC fluorescence versus side scatter light data. Subpanels C and F depict the gated lymphocyte population labeled with the respective antibody specific for the cell surface antigen.

Cellular proliferation assay.

There was no significant difference between the breeds in the abilities of their PBMC to respond to stimulation with ConA or PHA at any sampling time point (data not shown). Proliferation of PBMC in the presence of tick antigen was not significantly different from the proliferation of cells in medium alone (data not shown).

Tick-specific IgG antibody levels.

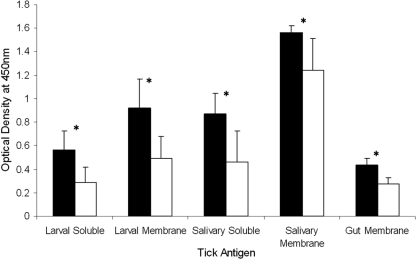

Significantly higher levels (P < 0.001) of IgG1 antibodies specific for the tick antigen extracts LM, SM, GM, LS, and SS were observed in sera collected from the Holstein-Friesian animals than in sera from the Brahman animals (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference between the breeds for the level of IgG2 antibodies specific for any of the tick antigen extracts (data not shown). All animals demonstrated relatively low levels of tick-specific IgG2 compared to IgG1, apart from three Holstein-Friesian animals that developed moderately high levels of IgG2 specific for all antigen extracts (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

IgG1 antibody levels specific for tick antigen extracts of Holstein-Friesian (black) and Brahman (white) cattle. Results are presented as breed means of three time points with standard deviations from the group means. Holstein-Friesian animals had significantly (P < 0.001) higher levels of IgG1 antibodies specific for all tick antigen extracts than did Brahman animals, as indicated by the asterisks.

Expression of selected cytokines and chemokines by peripheral blood leukocytes.

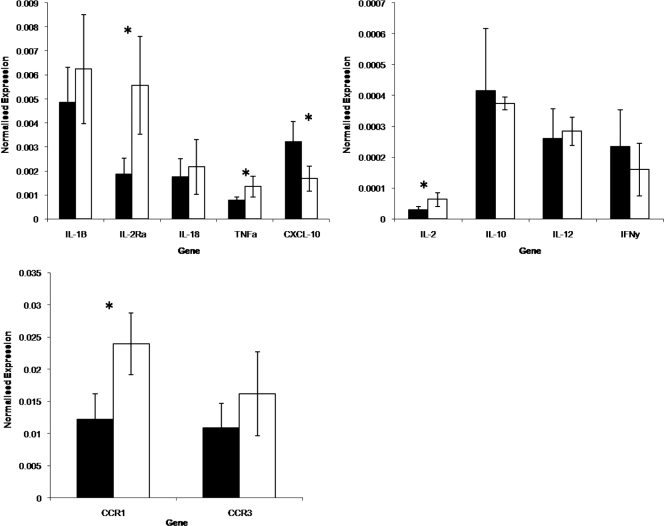

Blood was collected at only one time point during the height of infestation for cytokine profiling of peripheral blood leukocytes. One Brahman animal was excluded from the analysis due to poor RNA quality, and thus qPCR profiling of cytokine expression is based on six Holstein-Friesian and five Brahman animals. Transcripts of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Rα), IL-10, IL-12, IL-18, gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), CXC motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL-10), chemokine receptor 1 (CCR-1), and chemokine receptor 3 (CCR-3) were detected for every animal. Significantly higher expression of IL-2 (P = 0.026), IL-2Rα (P = 0.008), TNF-α (P = 0.035), and CCR-1 (P = 0.009) was detected in peripheral blood leukocytes from Brahman cattle than in those from Holstein-Friesian animals, while significantly higher expression of CXCL-10 (P = 0.034) was detected in the Holstein-Friesian cattle than in Brahman animals (Fig. 4). The ability to detect IL-4, IL-6, and IL-8 was variable in animals of both breeds (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytokine/chemokine receptor expression by WBCs of Holstein-Friesian (black) and Brahman (white) cattle. Results are presented as breed mean normalized expression values with standard deviations from the group means. Asterisks denote significant differences between the breeds.

Microarray analysis.

Quality control checks established that the slides were of good quality and there were no outliers in the samples (see the supplementary analysis file at GEO). A study comparing 45 different combinations for background correction, normalization, and summarization of Affymetrix microarray data found that the major source of variability in the analysis is the method of summarization used to transform the multiple probe intensities into one measure of expression (14). To obtain maximum specificity in our studies, three different summarization methods were used (MAS, RMA, and GCRMA) and only genes with a P value of <0.01 in at least two out of the three methods and flagged as present in at least half of the samples were considered to be significant. This approach increases the stringency of the study, and thus no false discovery rate correction method for multiple testing is necessary.

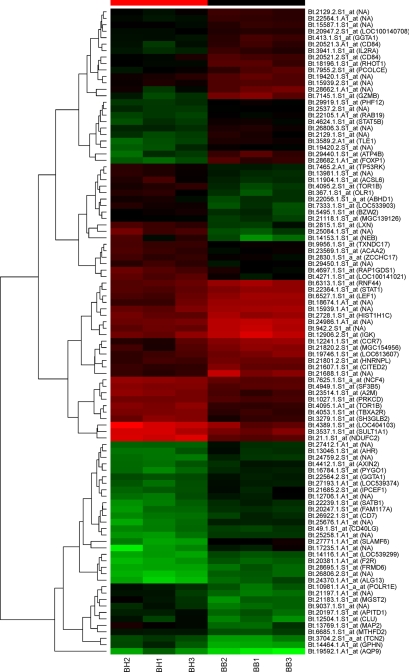

A total of 497 transcripts were detected as significantly DE (P < 0.01) by WBCs in the peripheral circulation of Holstein-Friesian and Brahman cattle. Two hundred fifty-three of these were more highly expressed by cells from Brahman cattle, while the remaining 244 were more highly expressed by the Holstein-Friesian group (Fig. 5; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material for a full list of DE genes). qPCR undertaken on eight arbitrarily chosen DE genes reflected closely the results obtained by the microarray, and these results are presented in Table S2b in the supplemental material.

FIG. 5.

MAS5 heat map plot of the top 100 (most significant) DE genes clustered using hierarchical clustering. Affymetrix identifications are listed with their corresponding gene symbol or “NA” if no gene assignment is available. For further information on gene names, expression changes, and significance values, see Table S1 in the supplemental material or the supplementary analysis file available through the accession number GSE13725 at the GEO website.

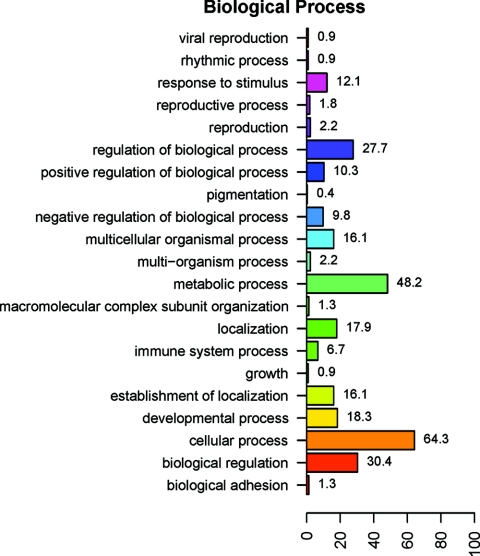

GO and pathway analysis.

DE genes were analyzed in the context of their GO biological process. Due to the incomplete annotation of the bovine genome, 273 of the 497 differentially expressed probe sets were not annotated and were excluded from the analysis (including duplicate probe sets that target the same gene). GO analyses showed that the major differences in gene expression between the two breeds were associated with cellular (64.3% of DE genes) and metabolic (48.2% of DE genes) processes in the level 2 biological process ontology categories (Fig. 6). Genes associated with immune system processes accounted for 6.7% of DE genes. The top-ranking biological process GO terms overrepresented by the DE genes are listed in Table 4, together with the gene descriptions for the term and P value for the test of significance. From molecular pathway analysis using DAVID, four major KEGG pathways were represented by genes DE by Brahman and Holstein-Friesian WBCs. Ten genes more highly expressed by Brahman WBCs were associated with the hemopoietic cell lineage (P = 0.0079) and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathways (P = 0.04), while 15 genes more highly expressed by Holstein-Friesian WBCs were associated with the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (P = 1.1E−09) and a further three represented the citrate cycle (P = 0.037) (Table 5).

FIG. 6.

Ontology analysis of 224 annotated DE genes in WBCs of Brahman and Holstein-Friesian cattle. The y axis lists the major biological processes represented by the 224 DE genes, and the x axis indicates the percentages of DE genes involved in the respective GO biological process. (Note that a gene may be involved in more than one GO category and thus the total percentage is more than 100.)

TABLE 4.

Top-ranking biological process GO terms for genes DE between Brahman and Holstein-Friesian cattle

| GO term/Affymetrix probe identifier | Entrez gene accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene description | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes more highly expressed by Brahman WBC | ||||

| Positive regulation of T-cell proliferation GO:0042102 | 5.40E−05 | |||

| Bt.3941.1.S1_at | 281861 | IL-2Rα | ||

| Bt.4624.1.S1_at | 282376 | STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | |

| Bt.48.1.S1_a_at | 281050 | CD28 | CD28 molecule | |

| Bt.5368.1.S1_at | 281054 | CD3E | CD3e molecule, epsilon (CD3-T-cell receptor complex) | |

| Negative thymic T-cell selection GO:0045060 | 0.00383 | |||

| Bt.48.1.S1_a_at | 281050 | CD28 | CD28 molecule | |

| Bt.5368.1.S1_at | 281054 | CD3E | CD3e molecule, epsilon (CD3-T-cell receptor complex) | |

| Positive regulation of IL-2 biosynthetic process GO:0045086 | 0.00748 | |||

| Bt.4624.1.S1_at | 282376 | STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | |

| Bt.48.1.S1_a_at | 281050 | CD28 | CD28 molecule | |

| Mononuclear cell proliferation | 0.03039 | |||

| Bt.3941.1.S1_at | 281861 | IL-2Rα | ||

| Bt.4624.1.S1_at | 282376 | STAT5B | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B | |

| Bt.48.1.S1_a_at | 281050 | CD28 | CD28 molecule | |

| Bt.49.1.S1_at | 282387 | CD40LG | CD40 ligand | |

| Bt.5368.1.S1_at | 281054 | CD3E | CD3e molecule, epsilon (CD3-T-cell receptor complex) | |

| Bt.8957.1.S1_at | 281736 | CXCR-4 | ||

| Genes more highly expressed by Holstein-Friesian WBC | ||||

| Organelle ATP synthesis-coupled electron transport GO:0042775 | 0.00092 | |||

| Bt.21.1.S1_at | 338046 | NDUFC2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 | |

| Bt.23361.1.S1_at | 616871 | UQCRB | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase binding protein | |

| Bt.4072.1.S1_at | 287014 | NDUFV1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 1 | |

| Bt.5040.1.S1_at | 281570 | UQCR | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (6.4-kDa) subunit | |

| Cobalt ion transport/cobalamin transport GO:0006824/GO:0015889 | 0.00131 | |||

| Bt.3704.1.S1_at | 281518 | TCN2 | Transcobalamin II; macrocytic anemia | |

| Bt.3704.2.S1_a_at | 281518 | TCN2 | Transcobalamin II; macrocytic anemia | |

| Malate metabolic process GO:0006108 | 0.00748 | |||

| Bt.5345.1.S1_at | 535182 | MDH1 | Malate dehydrogenase 1, NAD (soluble) | |

| Bt.7915.1.S1_at | 281306 | MDH2 | Malate dehydrogenase 2, NAD (mitochondrial) | |

| Pyridoxine biosynthetic process GO:0008615 | 0.00748 | |||

| Bt.20893.1.A1_at | 512573 | PNPO | Pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase | |

| Bt.20893.2.S1_at | 512573 | PNPO | Pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase | |

| Chaperone cofactor-dependent protein folding GO:0051085 | 0.01217 | |||

| Bt.4095.1.A1_at | 533928 | TOR1B | Torsin family 1, member B (torsin B) | |

| Bt.4095.2.S1_at | 533928 | TOR1B | Torsin family 1, member B (torsin B) | |

| Glycolysis | 0.01526 | |||

| Bt.22783.1.S1_at | 281141 | ENO1 | Enolase 1 (alpha) | |

| Bt.3809.1.S1_at | 281274 | LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A | |

| Bt.5345.1.S1_at | 535182 | MDH1 | Malate dehydrogenase 1, NAD (soluble) | |

| Bt.7915.1.S1_at | 281306 | MDH2 | Malate dehydrogenase 2, NAD (mitochondrial) |

TABLE 5.

KEGG pathways represented by DE genes

| KEGG pathway/Affymetrix probe identifier | Entrez gene identification no. | Gene description | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes with higher expression in Brahman WBC | |||

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | 0.0079 | ||

| Bt.15905.1.S1_at | 404154 | IL-4Rα chain | |

| Bt.27981.1.S1_at | 407126 | Complement receptor type 2 | |

| Bt.3941.1.S1_at | 281861 | IL-2Rα | |

| Bt.26922.1.S1_at | 510073 | Similar to T-cell antigen CD7 precursor | |

| Bt.5368.1.S1_at | 281054 | Antigen CD3e, epsilon polypeptide | |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 0.04 | ||

| Bt.12241.1.S1_at | 510668 | Chemokine receptor 7 | |

| Bt.15905.1.S1_at | 404154 | IL-4Rα chain | |

| Bt.49.1.S1_at | 282387 | TNF (ligand) superfamily, member 5 | |

| Bt.8957.1.S1_at | 281736 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 | |

| Bt.3941.1.S1_at | 281861 | IL-2Rα | |

| Genes with higher expression in Holstein-Friesian WBC | |||

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 1.10E−09 | ||

| Bt.13128.1.S1_at | 286840 | Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit b, iron sulfur | |

| Bt.21.1.S1_at | 338046 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1, subcomplex unknown, 2, 14.5 kDa | |

| Bt.4072.1.S1_at | 287014 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 1, 51 kDa | |

| Bt.442.1.S1_at | 281640 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial f1 complex | |

| Bt.4431.1.S1_a_at | 327675 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial f1 complex, beta polypeptide | |

| Bt.4540.1.S1_at | 327668 | ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial f1 complex, gamma polypeptide 1 | |

| Bt.4704.1.S1_at | 327714 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 5, 13 kDa | |

| Bt.5040.1.S1_at | 281570 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (6.4-kDa) subunit | |

| Bt.61.1.S1_at | 338073 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 3, 12 kDa | |

| Bt.66.1.S1_at | 338064 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 3, 9 kDa | |

| Bt.67.1.S1_at | 282289 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1, subcomplex unknown, 1 (6 kDa) | |

| Bt.7193.1.S1_at | 282199 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit via polypeptide 1 | |

| Bt.848.1.S1_at | 282290 | NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein 2 (24 kDa) | |

| Bt.893.1.S1_at | 327665 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 6, 17 kDa | |

| Bt.8950.1.S1_at | 338084 | Cell death regulatory protein grim19 | |

| Citrate cycle | 0.037 | ||

| Bt.7915.1.S1_at | 281306 | Malate dehydrogenase 2, mitochondrial | |

| Bt.1311.1.S1_at | 511090 | Similar to succinyl coenzyme A ligase (ADP-forming) beta chain | |

| Bt.13128.1.S1_at | 286840 | Succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit b, iron sulfur |

DISCUSSION

Results presented here demonstrate clear differences between the breeds in the levels of host resistance to tick infestation and in cellular and antibody parameters measured in the peripheral blood. The significantly lower RBC count in the Holstein-Friesian animals, and correspondingly low hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, are typical hematological parameters often observed in heavily infested animals. Although all erythron parameters for animals of both breeds were within ranges considered normal for cattle (26), Holstein-Friesian values for RBCs, hemoglobin, and hematocrit were verging on those considered to define anemia (5). A significantly higher WBC count was also recorded for the Holstein-Friesian animals that is slightly above the range considered normal for cattle; the normal range for cattle is reported to be 4 × 103 to 12 × 103/mm3 (26). It has been noted that WBC counts can be higher in calves of 6 months to 3 years of age; however, the high WBC count in these heavily infested animals is more likely a reflection of the prolonged period of inflammation and stress caused by the heavy tick burden. The significantly higher WBC count in the Holstein-Friesian animals is consistent with the work of Rechav et al. (33), who reported higher WBC counts in Simmentaler (B. taurus) cattle infested with African tick species than in Brahman cattle managed under the same conditions.

The two breeds showed significant differences in the relative percentages of cellular subsets comprising the PBMC population. The Brahman group had higher percentages of γδ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD25+ T cells than did the Holstein-Friesians, while the Holstein-Friesians had relatively higher percentages of macrophage-type cells (monocytes and MHCII-expressing cells) in their circulation. The higher percentage of MHCII-expressing cells recorded for the Holstein-Friesian animals can be mainly attributed to a higher percentage of CD14+ cells in these animals, as there was no significant difference between the breeds in the percentages of B cells seen in circulation. The relatively lower percentage of T-cell subsets observed in the Holstein-Friesian animals may have resulted from these cells moving out of the blood and into the skin at the site of tick attachment, thus reducing the relative numbers observed in the peripheral circulation. Similarly, the lower percentage of macrophage-type cells in the Brahman animals may reflect a similar effect. However, with regard to the MHCII-expressing cells, the more likely scenario is that these cellular subsets have proliferated in the Holstein-Friesians in response to the heavy tick burden, as these are the cell types responsible for presenting exogenously derived antigen to the immune system. We acknowledge, however, that it is not possible to determine whether these differences are a response to tick infestation or whether they are innate differences between the breeds, as preinfestation measurements were not obtained (because the animals in this study had been previously exposed to ticks in the field prior to the commencement of the trial). The differences in the relative percentages of cellular subsets comprising the periphery in these breeds were reflected in the qPCR analysis of cytokine expression of the WBCs. The significantly higher expression of IL-2Rα (CD25), IL-2, TNF-α, and CCR-1 by WBCs of the Brahman animals suggests a more vigorous T-cell response in this group, whereas the higher expression of CXCL-10 by WBCs of the Holstein-Friesian animals is consistent with the higher levels of inflammatory/macrophage-type cells observed in the peripheral circulation of these animals (29).

Since many differences were noted between the Brahman and Holstein-Friesian cattle with regard to their cellular profiles and gene expression of WBCs, analysis of WBC global gene expression of three Brahman and three Holstein-Friesian animals was undertaken to examine more closely the processes taking place in the blood during tick infestation. To our knowledge, this is the first study to undertake global gene expression analysis of WBCs in tick-infested cattle. Many genes that were detected as DE between the two breeds fell into two general categories: those involved with adaptive immune responses and those involved in metabolic processes. GO analysis demonstrated that several genes more highly expressed by WBCs of Brahman cattle overrepresented processes involved in adaptive immunity such as T-cell proliferation and selection and mononuclear cell proliferation. This was also reflected in the KEGG pathway analysis, which generated two major pathways for genes more highly expressed by Brahman WBCs: the hemopoietic cell lineage and cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions. Conversely, genes that were more highly expressed by WBCs of Holstein-Friesian cattle belonged to metabolic ontologies such as electron transport and glycolysis, which represented two KEGG pathways: oxidative phosphorylation and the citrate cycle. The results of the microarray analysis, in combination with other cellular parameters measured in these animals, suggest that the Brahman cattle have developed a predominantly T-cell-mediated response to tick infestation. It should not, however, be discounted that any T-cell response elicited by the Holstein-Friesian animals may be predominantly active in the skin at the site of tick attachment or in the lymph organs draining the skin.

The higher level of tick-specific IgG1 detected in the Holstein-Friesian animals than in the Brahman group in the present study is in contrast to the results obtained by Kashino et al. (24), who reported that tick saliva-specific IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies decreased in susceptible animals compared with resistant animals following periods of heavy infestation. The discrepancy in results between our study and that of Kashino et al. (24) may be due to the length of time over which the studies were conducted. The study by Kashino et al. collected serum intermittently over a period of 12 to 14 months, during which animals were exposed to natural infestations, whereas in the present study, serum was collected over a 3-week period during the height of artificial infestations. Cruz et al. (7) have reported differences in the levels of IgG against different tick antigens between heavy and light infestations, as well as individual variation in humoral responses to tick antigens. Similarly, our results demonstrated individual variation in IgG2 responses to tick antigen extracts, as three Holstein-Friesian animals developed moderate to high titers of IgG2 to several antigen extracts, while titers of other animals were not significantly higher than those of the uninfested animal control sera. Preliminary Western blot analysis (data not shown) has demonstrated that the Holstein-Friesian animals and Brahman animals produce antibodies to different tick antigens. More extensive immunoblotting will be undertaken in the future to determine whether differential recognition of tick antigens plays a role in resistance or susceptibility to ticks.

No proliferation was detected above background levels from PBMC stimulated with tick antigen extracts in vitro in either breed. This result could be due to an inhibitory action of the tick antigen extracts, as previously reported by Turni et al. (42), who showed that addition of tick SGEs could inhibit the proliferative response of cells from B. taurus and B. indicus animals to ConA stimulation. The extracts of whole adult female ticks used in the present study may have contained sufficient quantities of SGEs (and other proteins) capable of causing inhibition. However, a more probable reason for the lack of response to these antigens may simply be that the immunogenic proteins were not present in sufficient quantities to stimulate the cells in vitro. It could be assumed that any antigen passed from the tick to the host during the larval stage would be in such small quantities compared to those of other proteins present in the whole larval extract that any immunogenic protein might not be present in concentrations sufficient to produce a detectable proliferation response. As an acquired T-cell response is critical to the development of tick-specific IgG and most probably to host resistance to infestation, further investigation is required concerning the tick salivary antigens presented to the host immune system during feeding and their role in initiating adaptive immunity.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, we have shown that cellular, humoral, and gene expression profiles in the peripheral circulation differ significantly between tick-resistant B. indicus and tick-susceptible B. taurus cattle infested with R. microplus. Brahman cattle demonstrated PBMC profiles and WBC gene expression profiles consistent with a T-cell-mediated response to tick infestation, while Holstein-Friesian cattle demonstrated cellular profiles consistent with an innate, inflammatory-type response to infestation. Future experiments will be designed to include preinfestation measurements to track the development of the immune response throughout the development and stabilization of tick resistance/susceptibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Cooperative Research Centre for Beef Genetic Technologies (BeefCRC).

We thank Tom Connolly (University of Queensland) for his care of the animals in this project and assistance with sample collection and Ralph Stutchbury (QDPI&F) for preparation of tick larvae. Thanks are also extended to the University of Queensland's Animal Genetics Laboratory in the School of Veterinary Science for their technical assistance and also to Helle Bielefeldt-Ohmann for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 May 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://cvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Affymetrix. 2002. Statistical algorithms description document. Technical report. Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA.

- 2.Ashburner, M., C. Ball, J. Blake, D. Botstein, H. Butler, J. Cherry, A. Davis, K. Dolinski, S. Dwight, J. Eppig, M. Harris, D. Hill, L. Issel-Tarver, A. Kasarkis, S. Lewis, J. Matese, J. Richardson, M. Ringwald, G. Rubin, G. Sherlock, et al. 2000. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2525-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolstad, B., F. Collin, J. Brettschneider, K. Simpson, L. Cope, R. Irizarry, and T. Speed. 2005. Quality assessment of Affymetrix GeneChip Data, p. 33-47. In R. Gentleman, V. Carey, W. Huber, R. Irizarry, and S. Dutoit (ed.), Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer, New York, NY.

- 4.Carvalho, W. A., G. H. Bechara, D. D. Moré, B. R. Ferreira, J. S. da Silva, and I. K. F. de Miranda Santos. 2008. Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus: distinct acute phase proteins vary during infestations according to the genetic composition of the bovine hosts, Bos taurus and Bos indicus. Exp. Parasitol. 118587-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole, D., A. Roussel, and M. Whitney. 1997. Interpreting a bovine CBC: collecting and sample and evaluating the erythron. Vet. Med. 92460-468. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coussens, P. M., N. Verman, M. A. Coussens, M. D. Elftman, and A. M. McNulty. 2004. Cytokine gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tissues of cattle infected with Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis: evidence for an inherent proinflammatory gene expression pattern. Infect. Immun. 721409-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz, A. P. R., S. S. Silva, R. T. Mattos, I. Da Silva Vaz, Jr., A. Masuda, and C. A. S. Ferreira. 2008. Comparative IgG recognition of tick extracts by sera of experimentally infested bovines. Vet. Parasitol. 158152-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis, G., B. Sherman, D. Hosack, J. Yang, W. Gao, H. Lane, and R. Lempicki. 2003. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4R60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch, J. 1994. Identification of a major gene for resistance to cattle ticks, p. 293-295. In C. Smith, J. S. Gavora, B. Benkel, J. Chesnais, W. Fairfull, J. P. Gibson, B. W. Kennedy, and E. B. Burnside (ed.), Proceedings of the 5th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisch, J. E. 1999. Towards a permanent solution for controlling cattle ticks. Int. J. Parasitol. 2957-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautier, L., L. Cope, B. Bolstad, and R. Irizarry. 2004. Affy—analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics 20307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gene Ontology Consortium. 2006. The Gene Ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D322-D326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentleman, R., V. Carey, D. Bates, B. Bolstad, M. Dettling, S. Dudoit, B. Ellis, L. Gautier, Y. Ge, J. Gentry, K. Hornik, T. Hothorn, W. Huber, S. Iacus, R. Irizarry, F. Leisch, C. Li, M. Maechler, A. Rossini, G. Sawitzki, C. Smith, G. Smyth, L. Tierney, J. Yang, and J. Zhang. 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison, A., C. Johnston, and C. Orengo. 2007. Establishing a major cause of discrepancy in the calibration of Affymetrix GeneChips. BMC Bioinformatics 8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewetson, R. W. 1971. Resistance by cattle to the cattle tick Boophilus microplus. III. The development of resistance to experimental infestations by purebred Sahiwal and Australian Illawarra shorthorn cattle. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 22331-342. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inokuma, H., D. H. Kemp, and P. Willadsen. 1994. Comparison of prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) in salivary-gland of Boophilus microplus, Haemaphysalis longicornis and Ixodes holocyclus, and quantification of PGE2 in saliva, hemolymph, ovary and gut of B. microplus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 561217-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inokuma, H., R. L. Kerlin, D. H. Kemp, and P. Willadsen. 1993. Effects of cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) infestation on the bovine immune system. Vet. Parasitol. 47107-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irizarry, R., B. Bolstad, F. Collin, L. Cope, B. Hobbs, and T. Speed. 2003. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 31e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irizarry, R., B. Hobbs, F. Collin, Y. Beazer-Barclay, K. Antonellis, U. Scherf, and T. Speed. 2003. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4249-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson, L., and J. Opdebeeck. 1989. The effect of antigen concentration and vaccine regimen on the immunity induced by membrane antigens from the midgut of Boophilus microplus. Immunology 68272-276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonsson, N. N. 2006. The productivity effects of cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) infestation on cattle, with particular reference to Bos indicus cattle and their crosses. Vet. Parasitol. 1371-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanehisa, M., and S. Goto. 2000. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2827-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanehisa, M., S. Goto, M. Hattori, K. F. Aoki-Kinoshita, M. Itoh, S. Kawashima, T. Katayama, M. Araki, and M. Hirakawa. 2006. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 34D354-D357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashino, S. S., J. Resende, A. M. S. Sacco, C. Rocha, L. Proenca, W. A. Carvalho, A. A. Firmino, R. Queiroz, M. Benavides, L. J. Gershwin, and I. K. F. De Miranda Santos. 2005. Boophilus microplus: the pattern of bovine immunoglobulin isotype responses to high and low tick infestations. Exp. Parasitol. 11012-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr, R., J. Frisch, and B. Kinghorn. 1994. Evidence for a major gene for tick resistance in cattle, p. 265-268. In C. Smith, J. S. Gavora, B. Benkel, J. Chesnais, W. Fairfull, J. P. Gibson, B. W. Kennedy, and E. B. Burnside (ed.), Proceedings of the 5th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer, J. 2000. Normal hematology of cattle, sheep and goats. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 27.Kunz, S. E., and D. H. Kemp. 1994. Insecticides and acaricides—resistance and environmental impact. Rev. Sci. Tech. 131249-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, W., R. Mei, X. Di, T. Ryder, E. Hubbell, S. Dee, T. Webster, C. Harrington, M. Ho, J. Baid, and S. Smeekens. 2002. Analysis of high density expression microarrays with signed-rank call algorithms. Bioinformatics 181593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neville, L., G. Mathiak, and O. Bagasra. 1997. The immunobiology of interferon-gamma inducible protein 10kD (IP-10): a novel, pleiotropic member of the C-X-C chemokine superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 8207-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pepper, S., E. Saunders, L. Edwards, C. Wilson, and C. Miller. 2007. The utility of MAS5 expression summary and detection call algorithms. BMC Bioinformatics 8273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piper, E. K., L. A. Jackson, N. H. Bagnall, K. K. Kongsuwan, A. E. Lew, and N. N. Jonsson. 2008. Gene expression in the skin of Bos taurus and Bos indicus cattle infested with the cattle tick, Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 126110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Development Core Team. 2008. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- 33.Rechav, Y., J. Dauth, and D. A. Els. 1990. Resistance of Brahman and Simmentaler cattle to southern African ticks. Onderstepoort 577-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reck, J., Jr., M. Berger, R. M. S. Terra, F. S. Marks, I. da Silva Vaz, Jr., J. A. Guimarães, and C. Termignoni. 2009. Systemic alterations of bovine hemostasis due to Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus infestation. Res. Vet. Sci. 8656-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riek, R. F. 1957. Studies on the reactions of animals to infestation with ticks. I. Tick anaemia. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 8209-214. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe, T., C. Gondro, D. Emery, and N. Sangster. 2008. Genomic analyses of Haemonchus contortus infection in sheep: abomasal fistulation and two Haemonchus strains do not substantially confound host gene expression in microarrays. Vet. Parasitol. 15471-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seifert, G. W. 1971. Variations between and within breeds of cattle in resistance to field infestations of the cattle tick (Boophilus microplus). Aust. J. Agric. Res. 22159-168. [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Simon, P. 2003. Q-Gene: processing quantitative real-time RT-PCR data. Bioinformatics 191439-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyth, G. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smyth, G., and T. Speed. 2003. Normalisation of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart, N., L. Callow, and F. Duncalfe. 1982. Biological comparisons between a laboratory-maintained and recently isolated field strain of Boophilus microplus. J. Parasitol. 68691-694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strandberg, Y., C. Gray, T. Vuocolo, L. Donaldson, M. Broadway, and R. Tellam. 2005. Lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid induce different innate immune responses in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Cytokine 3172-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turni, C., R. P. Lee, and L. A. Jackson. 2002. Effect of salivary gland extracts from the tick, Boophilus microplus, on leukocytes from Brahman and Hereford cattle. Parasite Immunol. 24355-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Utech, K. B., R. H. Wharton, and J. D. Kerr. 1978. Resistance to Boophilus microplus in different breeds of cattle. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 29885-895. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagland, B. M. 1978. Host resistance to cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) in Brahman (Bos indicus) cattle. II. The dynamics of resistance in previously unexposed and exposed cattle. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 29395-400. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wharton, R. H., K. B. W. Utech, and H. G. Turner. 1970. Resistance to cattle tick, Boophilus microplus in a herd of Australian Illawarra shorthorn cattle—its assessment and heritability. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 21163-180. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, Z., I. RA, R. Gentleman, F. M. Murillo, and F. Spencer. 2003. A model based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 99909-917. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.