Abstract

Cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) are produced by many Pseudomonas species and have several biological functions, including a role in surface motility, biofilm formation, virulence, and antimicrobial activity. This study focused on the diversity and role of LuxR-type transcriptional regulators in CLP biosynthesis in Pseudomonas species and, specifically, viscosin production by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain SBW25. Phylogenetic analyses showed that CLP biosynthesis genes in Pseudomonas strains are flanked by LuxR-type regulators that contain a DNA-binding helix-turn-helix domain but lack N-acylhomoserine lactone-binding or response regulator domains. For SBW25, site-directed mutagenesis of the genes coding for either of the two identified LuxR-type regulators, designated ViscAR and ViscBCR, strongly reduced transcript levels of the viscABC biosynthesis genes and resulted in a loss of viscosin production. Expression analyses further showed that a mutation in either viscAR or viscBCR did not substantially (change of <2.5-fold) affect transcription of the other regulator. Transformation of the ΔviscAR mutant of SBW25 with a LuxR-type regulatory gene from P. fluorescens strain SS101 that produces massetolide, a CLP structurally related to viscosin, restored transcription of the viscABC genes and viscosin production. The results further showed that a functional viscAR gene was required for heterologous expression of the massetolide biosynthesis genes of strain SS101 in strain SBW25, leading to the production of both viscosin and massetolide. Collectively, these results indicate that the regulators flanking the CLP biosynthesis genes in Pseudomonas species represent a unique LuxR subfamily of proteins and that viscosin biosynthesis in P. fluorescens SBW25 is controlled by two LuxR-type transcriptional regulators.

Cyclic lipopeptides (CLPs) have diverse functions for soil- and plant-associated Pseudomonas species, including a role in motility, biofilm formation, virulence, and defense against competing (micro)organisms (34). CLPs are synthesized by large, nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), which form an assembly line of various enzymatic steps, resulting in the modification and stepwise incorporation of amino acids in the peptide moiety (20, 39). For Pseudomonas species, the biosynthesis genes for syringomycin, syringopeptin, syringafactins, amphisin, arthrofactin, viscosin, massetolides, and putisolvin are now sequenced (2, 11, 12, 15, 22, 34). In comparison to the understanding of CLP biosynthesis, however, knowledge about the genetic regulation is limited and fragmentary.

For the various Pseudomonas strains studied to date, the GacA/GacS two-component system is a key regulator of CLP biosynthesis, as a mutation in either of the two encoding genes results in a loss of CLP production (11, 12, 14, 27, 28). For plant pathogenic Pseudomonas fluorescens strain 5064 and saprophytic Pseudomonas putida strain PCL1445, N-acylhomoserine lactone (N-AHL)-mediated quorum sensing was shown to be required for viscosin and putisolvin biosynthesis, respectively (10, 16). In many other pathogenic and saprophytic Pseudomonas strains, however, CLP production is not regulated via N-AHL-mediated quorum sensing (1, 11, 18, 26). Downstream of the Gac system, the heat shock proteins DnaK and DnaJ were shown to regulate putisolvin biosynthesis in P. putida strain PCL1445 (14). Although their exact role is not yet resolved, it was suggested that DnaK and DnaJ may be required for proper folding or activity of other regulators or are involved in the assembly of the peptide synthetase complex. Downstream of the Gac system in plant pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, two genes, designated salA and syrF, were identified as LuxR-type transcriptional regulators of syringomycin and syringopeptin biosynthesis (27, 30, 31, 44). In the salA mutant, syringomycin/syringopeptin production was completely abolished, whereas production of these CLPs was reduced by 88% in the syrF mutant, based on the results of activity assays with Geotrichum candidum (30). LuxR-type transcriptional regulators were also shown to be involved in the biosynthesis of syringafactins and putisolvin: mutations in syrF or psoR resulted in the loss of syringafactin and putisolvin production in P. syringae pv. tomato and P. putida, respectively (2, 15).

The LuxR superfamily consists of transcriptional regulators that contain a DNA-binding helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif in the C-terminal region. Based on their activation mechanism, LuxR-type regulators can be divided into two major groups, as follows: (i) regulators that belong to a two-component sensory transduction system and are activated upon phosphorylation, e.g., FixJ of Sinorhizobium meliloti (3), and (ii) regulators that are activated via binding to an autoinducer like N-AHL, e.g., LuxR of Vibrio fischeri (21). In addition, there are various LuxR-type regulators that contain the C-terminal HTH motif but do not belong to these two subfamilies. Examples of these are regulators that are activated upon ligand binding, e.g., MalT of Escherichia coli, induced by maltotriose (36), and so-called autonomous effector domain LuxR-type regulators, e.g., GerE, which is involved in regulating spore formation in Bacillus subtilis (17). With respect to CLP biosynthesis, two LuxR-type regulators have been identified to date. These include PpuR, a LuxR-type regulator involved in putisolvin production by P. putida PCL1445 and which harbors a putative N-AHL-binding domain (16), and the LuxR-type regulators SalA, SyrF, and SyrG in P. syringae pv. syringae; these latter LuxR-type regulators do not contain N-AHL-binding domains or response regulator domains and, therefore, do not belong to either of the two major LuxR-type subfamilies (27, 30, 31, 44).

This study focused on the function of specific LuxR-type regulators in P. fluorescens SBW25, a strain isolated from the phyllosphere of the sugar beet (43) and extensively used as a model for bacterial evolution and adaptation (35). Strain SBW25 produces the CLP viscosin, which plays an important role in swarming motility, biofilm formation, and activity against oomycete plant pathogens (12). Viscosin biosynthesis is governed by the NRPS genes viscA, viscB, and viscC. In contrast to the organization of most other CLP gene clusters described to date, the visc genes are not genetically linked, with viscA located approximately 1.62 Mb from viscBC on a linear map of the SBW25 genome (12). The biosynthesis of viscosin is regulated by the Gac system but not by N-AHL-mediated quorum sensing (11, 12, 44). Sequence analysis of the genes flanking the viscosin biosynthesis genes in strain SBW25 revealed the presence of two genes encoding LuxR-type transcriptional regulators designated ViscAR and ViscBCR. Both regulators were analyzed for specific motifs and domains, including HTH motifs and N-AHL domains, and for their relatedness to other LuxR-type transcriptional regulators. The role of ViscAR and ViscBCR in viscosin production for strain SBW25 was investigated by site-directed mutagenesis, followed by gene expression and biochemical analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

P. fluorescens strains SBW25 and SS101 were grown on Pseudomonas agar F (Difco) plates or in liquid King's medium B (KB) at 25°C. The ΔviscA, ΔviscB, and ΔviscC biosynthesis mutants were obtained as described previously (12). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used as a host for the plasmids used in site-directed mutagenesis and genetic complementation. E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates or in LB broth amended with the appropriate antibiotics.

Bioinformatic analyses.

Identification of the genes flanking the CLP biosynthesis genes was performed by either Blastx or Blastp analysis. For phylogenetic analyses, alignments were made with ClustalX (version 1.81), and trees were inferred by neighbor joining, using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Autoinducer and response regulator domains were identified by Pfam analysis (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search?tab=searchSequenceBlock).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the viscAR and viscBCR genes was performed based on the method described by Choi and Schweizer (9), generating ΔviscAR::Gmr (referred to as ΔviscAR) and ΔviscBCR::Gmr (referred to as ΔviscBCR). The primers used for amplification are described in Table 1. The 5′- and 3′-end fragments were chosen in such a way that when homologous recombination in Pseudomonas takes place, the FRT-Gm-FRT cassette is inserted approximately 383 bp after the start of the viscAR and 192 bp after the start of viscBCR open reading frames. The FRT-Gm-FRT cassette was amplified with pPS854-GM, a derivative of pPS854 (24), and FRT-F and FRT-R were used as primers (Table 1). The first-round PCR was performed with KOD polymerase (Novagen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The program used for the PCR consisted of 2 min of denaturation at 95°C, followed by five cycles subsequently of 95°C, 55°C, and 68°C, each for 20 s. The PCR amplification was preceded with 25 cycles, with annealing at 60°C. All fragments were run on a 1% agarose gel and purified with a NucleoSpin kit (Macherey-Nagel). The second-round PCR was performed by addition of equimolar amounts of the 5′-end fragment, FRT-Gm-FRT, and 3′-end fragments, and the PCR program contained three cycles subsequently of 95°C, 55°C, and 68°C for 20, 30, and 60 s, respectively. In the third extension cycle, 1.5 μl of the Up forward and Dn reverse primers (10 μM) was added. The PCR amplification was preceded with 25 cycles subsequently of 95°C, 58°C, and 68°C for 20, 20, and 120 s, respectively, and PCR fragments were purified as described above. The fragments were digested with BamHI or KpnI and cloned into BamHI- or KpnI-digested NucleoSpin-purified plasmid pEX18Tc. E. coli DH5α was transformed with the obtained pEX18Tc-viscAR and pEX18Tc-viscBCR plasmids by heat shock transformation, according to the work of Inoue et al. (25), and transformed colonies were selected on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma). Integration of the inserts was verified by PCR analysis with pEX18Tc primers (Table 1) and by restriction analysis of isolated plasmids. The inserts were verified with sequencing by BaseClear (Leiden, The Netherlands). The correct pEX18Tc-viscAR and pEX18Tc-viscBCR constructs were subsequently electroporated into strain SBW25. Electrocompetent cells were obtained according to the work of Choi et al. (8) by washing the cells three times with 300 mM sucrose from a 6-ml overnight culture and finally dissolving the cells in 100 μl of 300 mM sucrose. Electroporation occurred at 2.4 kV and 200 μF, and after incubation in SOC medium (2% Bacto tryptone [Difco], 0.5% Bacto yeast extract [Difco], 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MgSO4, 20 mM glucose [pH 7]) for 2 h at 25°C, cells were plated on KB supplemented with gentamicin (25 μg/ml). Obtained colonies were grown in LB medium for 1 h at 25°C and plated on LB medium supplemented with gentamicin (25 μg/ml) and 5% sucrose to select for recombinants that do not carry an integrated sacB gene as a result of a double crossover. Colonies were restreaked onto LB medium supplemented with gentamicin and 5% sucrose and onto LB medium supplemented with tetracycline (25 μg/ml). Colonies that did grow on LB medium with gentamicin but not on LB medium with tetracycline were selected and subjected to colony PCR to confirm the presence of the gentamicin resistance cassette and the absence of the tetracycline resistance cassette. Positive colonies were confirmed by sequencing the PCR fragments obtained with the Up forward and Dn reverse primers. The obtained ΔviscAR and ΔviscBCR mutants were tested for viscosin production by a drop collapse assay and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), as described in the work of de Bruijn et al. (11).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Fragment used for indicated testing | Orientation | Primer sequencesa |

|---|---|---|

| Site-directed mutagenesis | ||

| FRT | Forward | 5′-CGAATTAGCTTCAAAAGCGCTCTGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CGAATTGGGGATCTTGAAGTTCCT-3′ | |

| viscAR-Up | Forward | 5′-TCAAGCAAGCGGATCCGAAAAGATCCGCACGCTGGA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-tcagagcgcttttgaagctaattcgGCGCTGTGTGATTTCGTTCT-3′ | |

| viscAR-Dn | Forward | 5′-aggaacttcaagatccccaattcgCAGCAGCTTGATATCGAGCAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCAAGCAAGCGGATCCCGGGAGGAATGCTTCATA AG-3′ | |

| viscBCR-Up | Forward | 5′-TCAAGCAAGCGGTACCCGACACGGCAGATGAAACTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-tcagagcgcttttgaagctaattcgGAATCGGTGTAGATCGGGCT-3′ | |

| viscBCR-Dn | Forward | 5′-aggaacttcaagatccccaattcgATTGCCGATGGTGGAAAAGC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCAAGCAAGCGGTACCGCGGTATCGGGGTGATGAAT-3′ | |

| pEX18Tc | Forward | 5′-CCTCTTCGCTATTACGCCAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTTGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCG-3′ | |

| Heterologous expression | ||

| massAR | Forward | 5′-TG CTC CAG GGC GCT GTA GAG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CAT GCC GAG GGT GCA CAG-3′ | |

| Q-PCR | ||

| viscA | Forward | 5′-GGACATCTGGCTCGA CCAA-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGCCGCCGATGTTGTACAG-3′ | |

| viscB | Forward | 5′-GCCGTCGCCCTGTACGT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCTTTTTCCGCGAGATGCT-3′ | |

| viscC | Forward | 5′-GGTTCTCCAAGGCGGTTTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GACCTTGGCGATGACTTTGC-3′ | |

| rpoD | Forward | 5′-GCAGCTCTGTGTCCGTGATG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCTACTTCGTTGCCAGGGAATT-3′ | |

| viscAR | Forward | 5′-AACGAAATCACACAGCGCC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCTCGCACCAGTGCAACC-3′ | |

| viscBCR | Forward | 5′-CGCAGGAGCGCAGCAT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCATCGGCAATAGCAACGT-3′ |

The 5′ ends of the Up reverse and Dn forward primers for site-directed mutagenesis contain a 25-bp sequence (lowercase letters) complementary to the FRT-F and FRT-R primers for overlap extension in the second-round PCR. The 5′ ends of the Up forward and Dn reverse primers contain a restriction site (underlined) for BamHI, which is required for cloning into pEX18Tc.

Construction of pME6031-based vectors for heterologous expression.

Generation of the pME6031-massA and pME6031-massBC constructs is described in the work of de Bruijn et al. (11). The pME6031-massAR construct (previously referred to as pME6031-luxR-mA) was generated as described previously (13). The correct pME6031-massA, pME6031-massBC, and pME6031-massAR constructs were subsequently electroporated into strain SBW25 and the ΔviscA, ΔviscB, ΔviscC, ΔviscAR, and ΔviscBCR mutants. Electrocompetent cells were obtained by washing the cells three times with 1 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) and 15% glycerol from a 5-ml overnight culture and finally dissolving the cells in 100 μl of the washing buffer. Electroporation occurred as described above, and selection of transformants was performed on KB medium supplemented with tetracycline (25 μg/ml). Verification of transformation was performed by PCR analysis using one primer specific for the insert and one primer specific for the pME6031 vector. Viscosin and massetolide A production in the transformed SBW25 strain and mutants was tested with a drop collapse assay, followed by RP-HPLC and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analyses, as described previously (11).

Surface tension measurements and transcriptional analysis.

Cells were grown in a 24-well plate, with 1.25 ml KB broth per well, and shaken at 220 rpm at 25°C. At specific time points, growth was determined by measuring 100 μl in a 96-well plate in a Bio-Rad 680 microplate reader at 600 nm. From each culture, 1 ml was collected and spun down. The cells were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. For the RNA isolations and cDNA synthesis, four biological replicates were used for each time point. Biosurfactant production was measured qualitatively by the drop collapse assay and quantitatively by tensiometric analysis of the cell-free supernatant (K6 tensiometer; Kruss GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) at room temperature. To get the sufficient volume for the tensiometric analysis, the supernatants of four biological replicates were collected and pooled for each time point. The surface tension of each sample was measured in triplicate. RNA isolation and quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) analysis were performed, as described previously (11). The threshold cycle (CT) value for viscA was corrected for that of the housekeeping gene, as follows: ΔCT = CT (viscA) − CT (rpoD). The same formula was used for the other genes. The relative quantification (RQ) values were calculated with the formula RQ = 2−[ΔCT (mutant) − ΔCT (wild type)]. The primers used for the Q-PCR are described in Table 1. Q-PCR analysis was performed in duplicate (technical replicates) on four independent RNA isolations (biological replicates). Statistically significant differences were determined for log-transformed RQ values by analysis of variance (P < 0.05), followed by the Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparisons.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genetic analysis of LuxR-type regulators flanking CLP biosynthesis genes.

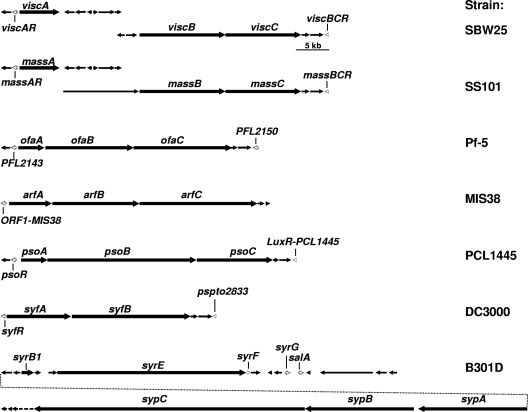

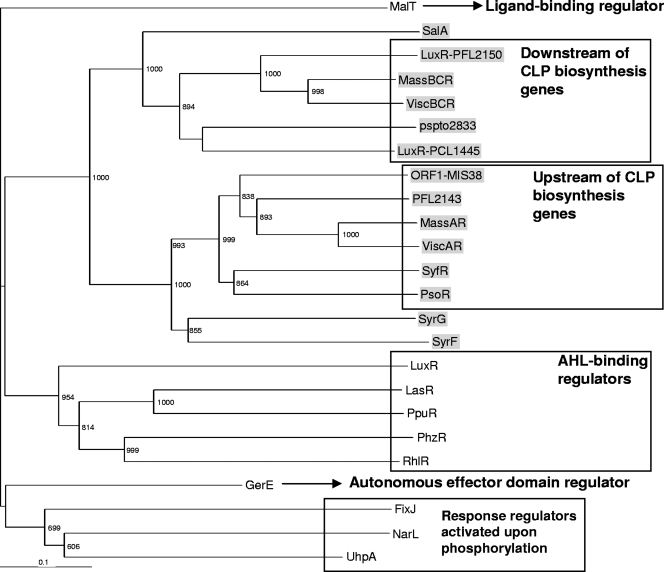

Analysis of gene clusters and genome sequences of various Pseudomonas species and strains known to produce CLPs revealed that LuxR-type transcriptional regulators are positioned up- and downstream of the CLP biosynthesis genes (Fig. 1). Subsequent alignment and Pfam analysis showed that the C-terminal regions of these LuxR-type regulators are relatively conserved and contain the typical DNA-binding HTH motif found in the entire family of LuxR-type transcriptional regulators (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). However, they do not harbor the N-AHL-binding domain found in LuxR of Vibrio fischeri (23, 38, 40) or the response regulator domain in FixJ, which activates the protein upon phosphorylation (3) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Phylogenetic analysis of these LuxR-type proteins resulted in several distinct clusters, as follows: LuxR-type regulators located upstream of the CLP biosynthesis genes clustered separately from the LuxR-type regulators located downstream of the CLP biosynthesis genes, except for the LuxR-type regulators SalA, SyrG, and SyrF from P. syringae pv. syringae, which were dispersed among the two clusters (Fig. 2). All LuxR-type regulators flanking the CLP biosynthesis genes clustered distantly from other well-known LuxR-type regulators, including GerE from B. subtilis, FixJ from S. meliloti, RhlR and LasR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and LuxR from V. fischeri (Fig. 2), suggesting that they can be classified as a separate subfamily of LuxR-type regulators.

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of various CLP biosynthesis clusters in Pseudomonas species and strains. The CLP biosynthesis genes and their flanking genes, including the LuxR-type transcriptional regulators (open arrows), are indicated. SBW25, viscosin-producing P. fluorescens strain; SS101, massetolide-producing P. fluorescens strain; Pf-5, orfamide-producing P. fluorescens strain; MIS38, arthrofactin-producing Pseudomonas sp.; PCL1445, putisolvin-producing P. putida strain; DC3000, syringafactin-producing P. syringae pv. tomato strain; B301D, syringomycin- and syringopeptin-producing P. syringae pv. syringae strain. The presence of a LuxR-type transcriptional regulator downstream of the arthrofactin biosynthesis cluster is not known due to a lack of sequence information.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of the LuxR-type regulators flanking the Pseudomonas CLP biosynthesis genes (shaded in gray). Also included in the analysis are other LuxR-type regulators, including LuxR of Vibrio fischeri (GenBank accession no. AAQ90196), LasR and RhlR of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GenBank accession no. BAA06489 and NP_252167), PpuR of Pseudomonas putida (GenBank accession no. AAZ80478), PhzR of Pseudomonas chlororaphis (GenBank accession no. ABR21211), the autonomous effector domain protein GerE of Bacillus subtilis (GenBank accession no. NP_390719), the phosphorylation-activated response regulator FixJ of Sinorhizobium meliloti (GenBank accession no. NP_435915), NarL of Escherichia coli (GenBank accession no. CAA33023), UhpA of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (GenBank accession no. NP_462689), and the ligand-binding MalT of E. coli (GenBank accession no. AAA83888). The numbers at the nodes indicate the level of bootstrap support, based on neighbor joining using 1,000 resampled data sets. The bar indicates the relative number of substitutions per site.

Functional analysis of LuxR-type regulatory genes in viscosin biosynthesis.

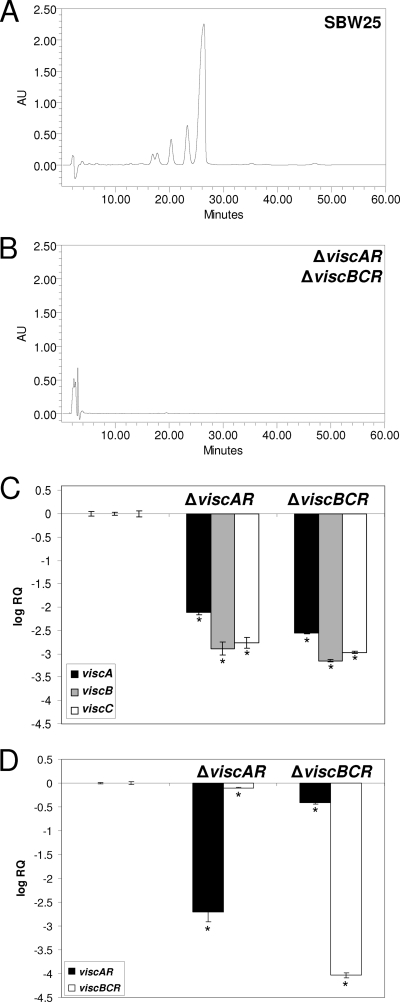

The CLP viscosin is produced by plant pathogenic and beneficial P. fluorescens strains (5, 10, 12). In the plant growth-promoting strain SBW25, viscosin biosynthesis is governed by the NRPS genes viscA, viscB, and viscC (Fig. 1) (12). In contrast to the organization of most other CLP gene clusters described to date, the visc genes are not genetically linked (Fig. 1) (12), with viscA located approximately 1.62 Mb from viscBC on a linear map of the SBW25 genome (12). In spite of this unusual organization, viscosin biosynthesis in strain SBW25 does obey the colinearity rule of nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis (12). Sequence analysis showed that the viscABC genes are also flanked by two LuxR-type regulator genes, one located upstream of viscA, designated viscAR, and one downstream of viscBC, designated viscBCR (Fig. 1). Genomic inactivation by site-directed mutagenesis of viscAR or viscBCR resulted in viscosin deficiency, as determined by drop collapse assays (data not shown) and RP-HPLC analyses (Fig. 3A and B). Transcriptional analysis by Q-PCR further showed that a mutation in either viscAR or viscBCR strongly reduced transcript levels of viscA, viscB, and viscC (Fig. 3C). These results confirm and extend the results obtained previously for P. syringae (2, 27, 30) and P. putida (15). In P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, however, only the LuxR-type regulator SyfR upstream of the syringafactin genes appeared to be essential, whereas a mutation of the LuxR-type regulator located downstream did not affect syringafactin biosynthesis (2). In P. putida PCL1445, only the LuxR-type regulator psoR, located upstream of the putisolvin genes, was investigated for its role in putisolvin production (15), but the function of the other LuxR-type regulator downstream of the putisolvin genes has, to our knowledge, not been resolved yet. Q-PCR analyses further showed that a mutation in either viscAR or viscBCR did not substantially (change of <2.5-fold) affect transcription of the other regulator (Fig. 3D), suggesting that they do not transcriptionally regulate each other. In P. syringae pv. syringae, the LuxR-type regulators SalA and SyrF were shown to be essential for syringomycin/syringopeptin biosynthesis (27, 30, 31). Subsequent gel shift analysis revealed that SalA binds to the promoter region of SyrF, whereas SyrF binds to the syr-syp box located around the −35 region of the syr-syp cluster (44, 45). These results elegantly showed that the control of expression of the syr-syp genes by SalA is mediated through SyrF. Wang et al. (44) further demonstrated that SalA and SyrF form homodimers in vitro (44), a process that has been shown to be critical for DNA binding by other various transcriptional regulators (17, 33, 46). Whether ViscAR and ViscBCR specifically bind to the promoter regions of the viscA and/or viscBC biosynthesis genes was not addressed in this study. Also, the role of dimerization of these LuxR-type regulators in the activation of the viscABC genes remains to be investigated.

FIG. 3.

RP-HPLC analyses of extracts obtained from cell-free culture supernatants of wild-type Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 (A) and the ΔviscAR or ΔviscBCR mutant of strain SBW25 (B). Extracts of each of the mutants were obtained and analyzed separately; the RP-HPLC chromatogram shown here is representative for each of the mutants. The main peak, with a retention time of approximately 26 min, is viscosin; the other peaks, with retention times between 16 and 24 min, are structural derivatives of viscosin. (C) Transcript levels of viscA, viscB, and viscC in cells of P. fluorescens SBW25, and the ΔviscAR and ΔviscBCR mutants obtained from mid-exponential growth phase. (D) Transcript levels of viscAR and viscBCR in the ΔviscAR and ΔviscBCR mutants in mid-exponential growth phase. The transcript levels of each of the genes was corrected for the transcript level of the housekeeping gene rpoD [ΔCT = CT (gene x) − CT (rpoD)] and presented relative to the transcript levels in wild-type SBW25 (log RQ), with RQ equaling 2−[ΔCT (mutant) − ΔCT (wild type)]. Mean values of four biological replicates are given; error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Asterisks indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences relative to wild-type SBW25.

Heterologous expression of LuxR-type transcriptional regulator.

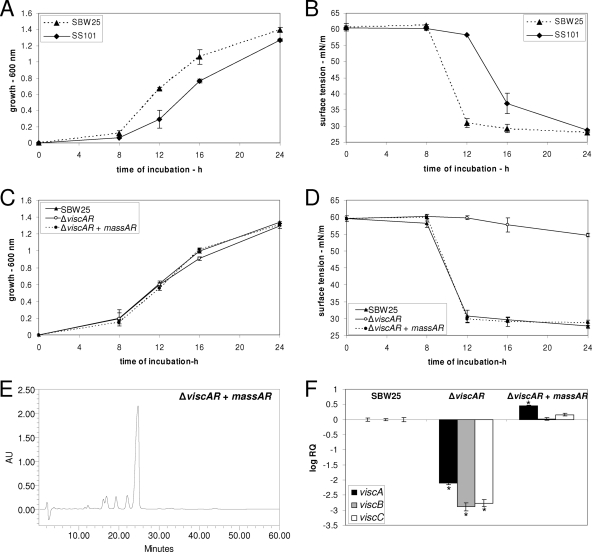

Like the physical organization of the viscABC genes in strain SBW25, the massetolide biosynthesis genes massABC are not genetically linked in P. fluorescens strain SS101 (Fig. 1) (11). Blastp and phylogenetic analyses showed that ViscAR and ViscBCR from strain SBW25 are most similar (82% and 81% amino acid identity, respectively) to MassAR and MassBCR, the two transcriptional regulators in strain SS101 located upstream of massA and downstream of massBC, respectively (Fig. 1 and 2; Table 2). In spite of these similarities, however, the growth characteristics of strains SBW25 and SS101 and, concomitantly, the dynamics of viscosin and massetolide production differ, with a significantly higher growth rate for strain SBW25 (Fig. 4A). Tensiometric analysis of the cell-free culture supernatants, which is indicative for viscosin and massetolide production (11, 12), further showed that viscosin is already produced by strain SBW25 after 8 h of growth, whereas massetolide production by strain SS101 is detectable after 12 h of growth (Fig. 4B). To determine if a LuxR-type regulator from strain SS101 can direct viscosin biosynthesis in strain SBW25, the massAR gene of strain SS101 was introduced into the ΔviscAR mutant of SBW25. The results showed that massAR did not affect growth of the ΔviscAR mutant of SBW25 (Fig. 4C) and restored the viscosin production level to the wild-type level, as confirmed by tensiometric and RP-HPLC analyses of the cell-free supernatants (Fig. 4D and E). Moreover, Q-PCR analysis also revealed that the transcript levels of viscA, viscB, and viscC were restored to wild-type levels in the massAR-transformed ΔviscAR mutant of strain SBW25 (Fig. 4F). No complementation of viscosin production was observed for the empty vector control (data not shown). These results indicate that LuxR-type transcriptional regulators can be exchanged among different Pseudomonas strains, thereby regulating the biosynthesis of structurally different CLPs. However, transformation of the ΔviscBCR mutant of strain SBW25 with the massAR gene from strain SS101 did not restore viscosin production (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that yet unknown characteristics (e.g., specific residues or domains) are essential for successful heterologous expression of these LuxR-type regulatory genes.

TABLE 2.

Percent amino acid identity of ViscAR and ViscBCR, the two LuxR-type transcriptional regulators of viscosin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25, with other LuxR-type regulators flanking the CLP biosynthesis genes in other Pseudomonas species and strains

| Species | Strain | CLP biosynthesis cluster(s) | LuxR-type transcriptional regulator | % Identity

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ViscAR | ViscBCR | ||||

| P. fluorescens | SBW25 | Viscosin | ViscAR | 100 | 42 |

| ViscBCR | 42 | 100 | |||

| P. fluorescens | SS101 | Massetolide | MassAR | 82 | 41 |

| MassBCR | 44 | 81 | |||

| P. fluorescens | Pf-5 | Orfamide | LuxR-PFL2143 | 63 | 41 |

| LuxR-PFL2150 | 36 | 63 | |||

| Pseudomonas sp. | MIS38 | Arthrofactin | ORF1-MIS38 | 62 | 32 |

| P. syringae pv. tomato | DC3000 | Syringafactins | SyfR | 56 | 37 |

| LuxR-pspto2833 | 41 | 44 | |||

| P. putida | PCL1445 | Putisolvin | PsoR | 54 | 29 |

| LuxR-PCL1445 | 40 | 52 | |||

| P. syringae pv. syringae | B301D | Syringomycin/syringopeptin | SyrG | 49 | 30 |

| SyrF | 48 | 30 | |||

| SyrA | 27 | 38 | |||

FIG. 4.

(A) Growth of Pseudomonas fluorescens strains SBW25 and SS101 in KB at 25°C; at each time point, cell density was measured spectrophotometrically (600 nm), and mean values from four replicates are given; error bars represent the standard deviations of the means. (B) Surface tension of cell-free culture supernatant of strains SBW25 and SS101 given in legend to panel A. (C) Growth of Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25, its ΔviscAR mutant, and the ΔviscAR mutant plus pME6031-massAR at 25°C; at each time point, cell density was measured spectrophotometrically (600 nm), and mean values from four replicates are given; error bars represent the standard deviations of the means. (D) Surface tension of cell-free culture supernatant of strain SBW25 and the different mutants given in legend to panel C. (E) RP-HPLC analysis of the ΔviscAR mutant plus pME6031-massAR. (F) Transcript levels of viscA, viscB, and viscC in cells of wild-type SBW25, the ΔviscAR mutant, and the ΔviscAR mutant plus pME6031-massAR obtained from mid-exponential growth phase. The transcript levels of each of the genes was corrected for the transcript level of the housekeeping gene rpoD [ΔCT = CT (gene x) − CT (rpoD)] and presented relative to the transcript levels in wild-type SBW25 (log RQ), with RQ equaling 2−[ΔCT (mutant) − ΔCT (wild type)]. For each time point, mean values from four biological replicates are given; error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Asterisks indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences relative to wild-type SBW25.

Heterologous expression of CLP biosynthesis genes.

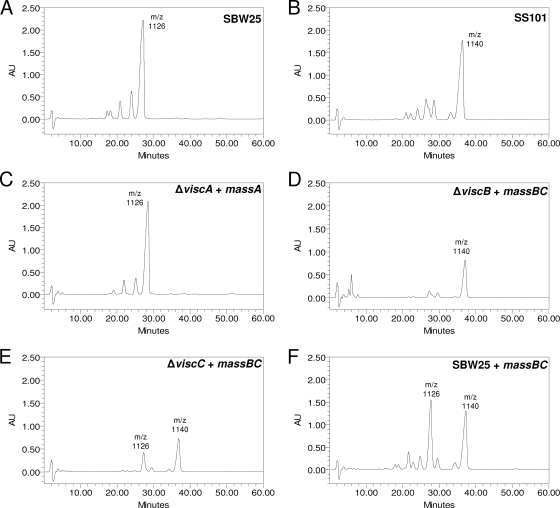

Since viscosin (m/z 1126) produced by strain SBW25 and massetolide (m/z 1140) produced by strain SS101 differ only in the fourth amino acid of the peptide ring (11, 12), experiments were conducted to determine (i) if the mass genes could complement viscosin deficiency of the Δvisc mutants of strain SBW25 and (ii) if a functional viscAR gene is required for successful expression of the mass genes. We expected that genetic complementation of the ΔviscA mutant of SBW25 with the massA gene from SS101 would restore viscosin production. In contrast, genetic complementation of the ΔviscB mutant with the massB gene, harboring the adenylation domain of the fourth amino acid with a signature sequence for isoleucine instead of valine (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), should result in massetolide production instead of that of viscosin. The results showed that introduction of the massA or massBC gene from strain SS101 did not affect growth of each of the Δvisc mutants of strain SBW25 (data not shown). Subsequent RP-HPLC analyses of cell-free culture supernatants showed that introduction of the massA gene in the ΔviscA mutant of SBW25 restored viscosin production to the wild-type level (Fig. 5A and C). Introduction of the massBC genes in the ΔviscB mutant did not restore viscosin production but resulted in massetolide production, as predicted and confirmed by LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 5B and D). Introduction of the massBC genes in the ΔviscC mutant or in wild-type strain SBW25 resulted in the production of both viscosin and massetolide (Fig. 5E and F). Transformation of the ΔviscAR mutant of SBW25 with massA or massBC did not restore viscosin production, nor did it lead to massetolide production, indicating that a functional viscAR gene is required for heterologous expression of the mass genes. These results also showed that large NRPS genes encoding CLPs can be exchanged among different Pseudomonas strains, leading to the production of nonnative compounds.

FIG. 5.

RP-HPLC chromatograms of cell-free culture extracts of wild-type SBW25, SS101, and the ΔviscA plus pME6031-massA, ΔviscB plus pME6031-massBC, ΔviscC plus pME6031-massBC, and SBW25 plus pME6031-massBC strains. Wild-type strain SBW25 produces viscosin (retention time of approximately 27 to 28 min; m/z 1126) and other derivatives of viscosin (peaks with retention times ranging from 16 to 24 min). Wild-type strain SS101 produces massetolide A (retention time of approximately 36 to 37 min; m/z 1140) and various other derivatives of massetolide A (peaks with retention times ranging from 21 to 33 min), differing in amino acid composition of the peptide moiety (11).

Concluding remarks.

Over the past decade, the biosynthesis genes of at least eight CLPs produced by Pseudomonas species have been identified and sequenced (2, 11, 12, 15, 22, 34). In contrast, very little is known about the genetic network involved in regulation of CLP biosynthesis. For plant growth-promoting P. fluorescens strain SBW25, only the gacS gene has been identified to date as a regulator of viscosin biosynthesis (12). This study established that viscosin production in strain SBW25 is also regulated by two LuxR-type genes, designated viscAR and viscBCR. Phylogenetic and domain analyses showed that the LuxR-type regulators flanking CLP biosynthesis genes in Pseudomonas, including ViscAR and ViscBCR, belong to a separate LuxR subfamily of proteins: they contain the typical HTH domain in the C-terminal region but lack the N-AHL-binding or response regulator domains found in other LuxR-type regulators (3, 23, 38, 40). The results showed, for the first time, that these LuxR-type transcriptional regulators can be exchanged among different Pseudomonas strains, thereby regulating the biosynthesis of structurally different CLPs. Genetic engineering of NRPS and polyketide synthase biosynthesis genes has received considerable interest in natural product research, as it provides a means to generate novel derivatives with more specific or enhanced activities (4, 6, 29, 42). For example, modification of genes involved in the biosynthesis of daptomycin and carotenoids resulted in a library of novel derivatives and generated valuable information on structural features required for antibacterial activity (32, 37). Work by Eppelmann et al. (19) showed that expression of the complete bacitracin biosynthesis cluster of the slow-growing Bacillus licheniformis in a surfactin-deficient (srfA) mutant of B. subtilis resulted in elevated levels of bacitracin compared to those of the natural producer. In many cases, however, yields of nonnative or structurally novel NRPS/polyketide synthase products are relatively low (6, 29, 42). Whether this is related to inefficient transcriptional regulation, poor communication between the encoded NRPS, or limited efflux of the final products remains to be addressed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Teris van Beek and Frank Claassen for their assistance in RP-HPLC and LC-MS/MS. We thank Teresa Sweat (USDA, Corvallis, OR) and Dimitri Mavrodi (USDA, Pullman, WA) for providing the plasmids (pEX18Tc and pPS854-Gm), protocols, and advice for the site-directed mutagenesis.

This work was funded by the Dutch Technology Foundation (STW), the applied science division of NWO.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 May 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, J. B., B. Koch, T. H. Nielsen, D. Sorensen, M. Hansen, O. Nybroe, C. Christophersen, J. Sorensen, S. Molin, and M. Givskov. 2003. Surface motility in Pseudomonas sp. DSS73 is required for efficient biological containment of the root-pathogenic microfungi Rhizoctonia solani and Pythium ultimum. Microbiology 149:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berti, A. D., N. J. Greve, Q. H. Christensen, and M. G. Thomas. 2007. Identification of a biosynthetic gene cluster and the six associated lipopeptides involved in swarming motility of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. J. Bacteriol. 189:6312-6323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birck, C., M. Malfois, D. Svergun, and J. Samama. 2002. Insights into signal transduction revealed by the low resolution structure of the FixJ response regulator. J. Mol. Biol. 321:447-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bode, H. B., and R. Muller. 2005. The impact of bacterial genomics on natural product research. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44:6828-6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, P. G., P. D. Hildebrand, T. C. Ells, and D. Y. Kobayashi. 2001. Evidence and characterization of a gene cluster required for the production of viscosin, a lipopeptide biosurfactant, by a strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:294-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cha, M., N. Lee, M. Kim, M. Kim, and S. Lee. 2008. Heterologous production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa EMS1 biosurfactant in Pseudomonas putida. Bioresour. Technol. 99:2192-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reference deleted.

- 8.Choi, K. H., A. Kumar, and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J. Microbiol. Methods 64:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, K. H., and H. P. Schweizer. 2005. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol. 5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui, X., R. Harling, P. Mutch, and D. Darling. 2005. Identification of N-3-hydroxyoctanoyl-homoserine lactone production in Pseudomonas fluorescens 5064, pathogenic to broccoli, and controlling biosurfactant production by quorum sensing. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 111:297-308. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bruijn, I., M. J. de Kock, P. de Waard, T. A. van Beek, and J. M. Raaijmakers. 2008. Massetolide A biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Bacteriol. 190:2777-2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bruijn, I., M. J. D. de Kock, M. Yang, P. de Waard, T. A. van Beek, and J. M. Raaijmakers. 2007. Genome-based discovery, structure prediction and functional analysis of cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics in Pseudomonas species. Mol. Microbiol. 63:417-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Bruijn, I., and J. M. Raaijmakers. 2009. Regulation of cyclic lipopeptide biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens by the ClpP protease. J. Bacteriol. 191:1910-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubern, J.-F., E. L. Lagendijk, B. J. J. Lugtenberg, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2005. The heat shock genes dnaK, dnaJ, and grpE are involved in regulation of putisolvin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida PCL1445. J. Bacteriol. 187:5967-5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubern, J. F., E. R. Coppoolse, W. J. Stiekema, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2008. Genetic and functional characterization of the gene cluster directing the biosynthesis of putisolvin I and II in Pseudomonas putida strain PCL1445. Microbiology 154:2070-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubern, J. F., B. J. J. Lugtenberg, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2006. The ppuI-rsaL-ppuR quorum-sensing system regulates biofilm formation of Pseudomonas putida PCL1445 by controlling biosynthesis of the cyclic lipopeptides putisolvins I and II. J. Bacteriol. 188:2898-2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ducros, V. M., R. J. Lewis, C. S. Verma, E. J. Dodson, G. Leonard, J. P. Turkenburg, G. N. Murshudov, A. J. Wilkinson, and J. A. Brannigan. 2001. Crystal structure of GerE, the ultimate transcriptional regulator of spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 306:759-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumenyo, C. K., A. Mukherjee, W. Chun, and A. K. Chatterjee. 1998. Genetic and physiological evidence for the production of N-acyl homoserine lactones by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae and other fluorescent plant pathogenic Pseudomonas species. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104:569-582. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eppelmann, K., S. Doekel, and M. A. Marahiel. 2001. Engineered biosynthesis of the peptide antibiotic bacitracin in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34824-34831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finking, R., and M. A. Marahiel. 2004. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:453-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuqua, C., S. C. Winans, and E. P. Greenberg. 1996. Census and consensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:727-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross, H., V. O. Stockwell, M. D. Henkels, B. Nowak-Thompson, J. E. Loper, and W. H. Gerwick. 2007. The genomisotopic approach: a systematic method to isolate products of orphan biosynthetic gene clusters. Chem. Biol. 14:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanzelka, B. L., and E. P. Greenberg. 1995. Evidence that the N-terminal region of the Vibrio fischeri LuxR protein constitutes an autoinducer-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 177:815-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue, H., H. Nojima, and H. Okayama. 1990. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Gene 96:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinscherf, T. G., and D. K. Willis. 1999. Swarming by Pseudomonas syringae B728a requires gacS (lemA) and gacA but not the acyl-homoserine lactone biosynthetic gene ahlI. J. Bacteriol. 181:4133-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitten, T., T. G. Kinscherf, J. L. McEvoy, and D. K. Willis. 1998. A newly identified regulator is required for virulence and toxin production in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 28:917-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch, B., T. H. Nielsen, D. Sorensen, J. B. Andersen, C. Christophersen, S. Molin, M. Givskov, J. Sorensen, and O. Nybroe. 2002. Lipopeptide production in Pseudomonas sp. strain DSS73 is regulated by components of sugar beet seed exudate via the Gac two-component regulatory system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4509-4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, Y. K., B. D. Yoon, J. H. Yoon, S. G. Lee, J. J. Song, J. G. Kim, H. M. Oh, and H. S. Kim. 2007. Cloning of srfA operon from Bacillus subtilis C9 and its expression in E. coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75:567-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu, S. E., B. K. Scholz-Schroeder, and D. C. Gross. 2002. Characterization of the salA, syrF, and syrG regulatory genes located at the right border of the syringomycin gene cluster of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, S. E., N. Wang, J. Wang, Z. J. Chen, and D. C. Gross. 2005. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of the salA regulon controlling phytotoxin production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18:324-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen, K. T., D. Ritz, J. Q. Gu, D. Alexander, M. Chu, V. Miao, P. Brian, and R. H. Baltz. 2006. Combinatorial biosynthesis of novel antibiotics related to daptomycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:17462-17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pristovsek, P., K. Sengupta, F. Lohr, B. Schafer, M. W. von Trebra, H. Ruterjans, and F. Bernhard. 2003. Structural analysis of the DNA-binding domain of the Erwinia amylovora RcsB protein and its interaction with the RcsAB box. J. Biol. Chem. 278:17752-17759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raaijmakers, J. M., I. De Bruijn, and M. J. D. De Kock. 2006. Cyclic lipopeptide production by plant-associated Pseudomonas spp.: diversity, activity, biosynthesis, and regulation. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 19:699-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rainey, P. B., and K. Rainey. 2003. Evolution of cooperation and conflict in experimental bacterial populations. Nature 425:72-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlegel, A., A. Bohm, S. J. Lee, R. Peist, K. Decker, and W. Boos. 2002. Network regulation of the Escherichia coli maltose system. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4:301-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt-Dannert, C., D. Umeno, and F. H. Arnold. 2000. Molecular breeding of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:750-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shadel, G. S., R. Young, and T. O. Baldwin. 1990. Use of regulated cell lysis in a lethal genetic selection in Escherichia coli: identification of the autoinducer-binding region of the LuxR protein from Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744. J. Bacteriol. 172:3980-3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sieber, S. A., and M. A. Marahiel. 2005. Molecular mechanisms underlying nonribosomal peptide synthesis: approaches to new antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 105:715-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slock, J., D. VanRiet, D. Kolibachuk, and E. P. Greenberg. 1990. Critical regions of the Vibrio fischeri luxR protein defined by mutational analysis. J. Bacteriol. 172:3974-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reference deleted.

- 42.Stachelhaus, T., A. Schneider, and M. A. Marahiel. 1995. Rational design of peptide antibiotics by targeted replacement of bacterial and fungal domains. Science 269:69-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timms-Wilson, T. M., R. J. Ellis, A. Renwick, D. J. Rhodes, D. V. Mavrodi, D. M. Weller, L. S. Thomashow, and M. J. Bailey. 2000. Chromosomal insertion of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid biosynthetic pathway enhances efficacy of damping-off disease control by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:1293-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, N., S. E. Lu, A. R. Records, and D. C. Gross. 2006. Characterization of the transcriptional activators SalA and SyrF, which are required for syringomycin and syringopeptin production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. J. Bacteriol. 188:3290-3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, N., S. E. Lu, Q. Yang, S. H. Sze, and D. C. Gross. 2006. Identification of the syr-syp box in the promoter regions of genes dedicated to syringomycin and syringopeptin production by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B301D. J. Bacteriol. 188:160-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, R. G., T. Pappas, J. L. Brace, P. C. Miller, T. Oulmassov, J. M. Molyneaux, J. C. Anderson, J. K. Bashkin, S. C. Winans, and A. Joachimiak. 2002. Structure of a bacterial quorum-sensing transcription factor complexed with pheromone and DNA. Nature 417:971-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.