Abstract

Lactococci are noninvasive bacteria frequently used as protein delivery vectors and, more recently, as in vitro and in vivo DNA delivery vehicles. We previously showed that a functional eukaryotic enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) expression plasmid vector was delivered in epithelial cells by Lactococcus lactis producing Listeria monocytogenes internalin A (L. lactis InlA+), but this strategy is limited in vivo to transgenic mice and guinea pigs. In this study, we compare the internalization ability of L. lactis InlA+ and L. lactis producing either the fibronectin-binding protein A of Staphylococcus aureus (L. lactis FnBPA+) or its fibronectin binding domains C and D (L. lactis CD+). L. lactis FnBPA+ and L. lactis InlA+ showed comparable internalization rates in Caco-2 cells, while the internalization rate observed with L. lactis CD+ was lower. As visualized by conventional and confocal fluorescence microscopy, large clusters of L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ were present in the cytoplasm of Caco-2 cells after internalization. Moreover, the internalization rates of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and of an NCFM mutant strain with the gene coding for the fibronectin-binding protein (fbpA) inactivated were also evaluated in Caco-2 cells. Similar low internalization rates were observed for both wild-type L. acidophilus NCFM and the fbpA mutant, suggesting that commensal fibronectin binding proteins have a role in adhesion but not in invasion. L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ were then used to deliver a eukaryotic eGFP expression plasmid in Caco-2 cells: flow cytometry analysis showed that the highest percentage of green fluorescent Caco-2 cells was observed after coculture with either L. lactis FnBPA+ or L. lactis InlA+. Analysis of the in vivo efficiency of these invasive recombinant strains is currently in progress to validate their potential as DNA vaccine delivery vehicles.

The mucosal administration of bacterial carriers to deliver antigens and plasmid DNA constitutes a promising vaccination strategy. Pathogenic bacteria that have the capacity to invade cells, such as Listeria, Salmonella, and Shigella strains, have been used to deliver DNA constructs into mammalian cells (23). Nevertheless, the risk associated with possible reversion to a virulent phenotype of these pathogens is a major concern (5). Lactococcus lactis, the food-grade, gram-positive, noninvasive model bacterium, has been intensively used to deliver antigens and cytokines at the mucosal level (30). We previously showed (i) that native L. lactis can deliver a eukaryotic expression cassette coding for the bovine β-lactoglobulin (BLG), one of the major cow's milk allergens, into mammalian epithelial Caco-2 cells, and (ii) that these cells were able to express and secrete BLG protein in its native conformation (10). Recently, we demonstrated the ability of native noninvasive L. lactis to deliver a fully functional plasmid to murine intestinal cells in vivo (2).

The internalization of the bacterial carrier is a fundamental step to achieve efficient DNA delivery in eukaryotic cells (7). In order to increase DNA delivery by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), invasin genes were expressed in L. lactis. Due to the safety profile of LAB, recombinant lactococci expressing invasin genes from intracellular bacteria are attractive as potential DNA delivery vectors compared to the attenuated pathogens presently used.

In this field, we previously demonstrated that L. lactis bacteria expressing the main Listeria monocytogenes invasin, internalin A (L. lactis InlA+), were able to invade eukaryotic cells and efficiently deliver a functional green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmid into epithelial/endothelial cells (9). Even though attractive, the experimental use of lactococci expressing InlA in a mouse model has a major bottleneck: InlA, which binds to human E-cadherin (15), does not interact with murine E-cadherin. Consequently, in vivo experimental studies using lactococci expressing InlA as DNA delivery vehicles are limited to transgenic mice expressing human E-cadherin or to guinea pigs (13).

Fibronectin binding protein A (FnBPA) of Staphylococcus aureus is another bacterial invasin that is involved in intracellular spreading of S. aureus in the host (27). It is a multifunctional adhesion protein having both fibrinogen and fibronectin binding capacities (24). Its N-terminal part, also called domain A, is responsible for fibrinogen (29) and elastin (20) binding, whereas its C-terminal part, including domains B, C, and D, binds to fibronectin (25). FnBPA is known to mediate adhesion to host tissue and bacterial uptake into nonphagocytic host cells (27). Its expression by L. lactis was previously shown to be sufficient to confer the ability to invade nonphagocytic cells in vitro and in vivo, while the expression of domains C and D confers invasivity only in vitro (19).

In this study, we show that L. lactis bacteria expressing full-length FnBPA of S. aureus (L. lactis FnBPA+) or a truncated form encompassing only its C and D domains (L. lactis CD+) are internalized as efficiently as L. lactis InlA+ in the human intestinal cell line Caco-2. We also provide, for the first time, direct microscopic evidence of the intracellular location of the internalized lactococci, showing that the bacteria are heterogeneously distributed in the cell monolayer and that their number per cell can reach a surprisingly high level. However, we demonstrate that FbpA, a fibronectin binding protein from the commensal Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, does not mediate bacterial internalization: no difference in invasivity was observed between the wild-type (wt) strain and the mutant with fbpA inactivated. This result indicates that, although widely distributed among bacteria, fibronectin binding proteins are not universal mediators of bacterial internalization, even at low levels. Finally, we also demonstrate that, similarly to L. lactis InlA+, L. lactis FnBPA+ and L. lactis CD+ can efficiently deliver a eukaryotic GFP expression plasmid in Caco-2 cells and trigger GFP expression in these cells. Consequently, L. lactis FnBPA+ can be used for further DNA delivery experiments in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis subsp. cremoris strains were grown in M17 medium containing 0.5% glucose (GM17) at 30°C. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium and incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking. L. acidophilus strain NCFM was grown in MRS broth at 37°C. Antibiotics were added at the indicated concentrations as necessary: erythromycin at 500 μg/ml for E. coli and 5 μg/ml for L. lactis and L. acidophilus NCFM and chloramphenicol at 10 μg/ml for E. coli and L. lactis.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. lactis InlA+ | L. lactis strain expressing the inlA gene of L. monocytogenes | 9 |

| L. lactis FnBPA+ | L. lactis strain expressing S. aureus FnBPA | 17 |

| L. lactis CD+ | L. lactis strain expressing the C and D domains of S. aureus FnBPA | 19 |

| wt L. lactis | L. lactis strain carrying plasmid pIL253 | 26 |

| L. lactis GFP | L. lactis strain carrying plasmids pIL253 and pValac:GFP | This study |

| L. lactis InlA+ GFP | L. lactis strain expressing inlA gene of L. monocytogenes and carrying plasmid pValac:GFP | This study |

| L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP | L. lactis strain expressing S. aureus FnBPA and carrying pValac:GFP | This study |

| L. lactis CD+ GFP | L. lactis strain expressing the C and D domains of S. aureus FnBPA and carrying pValac:GFP | This study |

| L. acidophilus NCFM fbpA | L. acidophilus NCFM mutant with fbpA gene inactivated | 1 |

| L. acidophilus NCFM | L. acidophilus human intestinal isolate | 22 |

| L. lactis MG1363 | wt L. lactis | 6 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIL253 | High-copy-no. lactococcal vector; Eryr | 26 |

| pGM10 | pUC19/pAT19 derivatives carrying inlA promoter and inlA gene of L. monocytogenes; Eryr | 9 |

| pOri23-FnBPA | L. lactis-E. coli shuttle vector carrying the FnBPA gene of S. aureus; Eryr | 17 |

| pOri23-CD | L. lactis-E. coli shuttle vector carrying sequence coding for the C and D domains of FnBPA of S. aureus; Eryr | 19 |

| pValac:GFP | L. lactis-E. coli shuttle vector carrying the gfp gene under the control of the eukaryotic immediate early promoter of the human cytomegalovirus; Cmr | 8 |

| pTRK833 | E. coli-L. acidophilus NCFM shuttle vector carrying 734-bp internal region of fbpA (LBA1148) cloned into BglII-XbaI sites of pORI28; Eryr | 1 |

Eryr, erythromycin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

DNA manipulations.

DNA manipulations were performed as described previously (21) with the following modifications: for plasmid DNA extraction from L. lactis, TES (25% sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8) containing lysozyme (10 mg/ml) was added for 30 min at 37°C to prepare protoplasts. Enzymes were used as recommended by suppliers. Electroporation of L. lactis was performed as described previously (11). Transformants were plated on GM17 agar plates containing the required antibiotic and were counted after 2 days of incubation at 30°C.

Assays of bacterial invasiveness in human epithelial cells.

Bacterial entry into human epithelial cells was assayed using the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 (ATCC number HTB37) as described previously (4). Eukaryotic cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (BioWhittaker, Cambrex Bio Science, Verviers, Belgium) and 20% fetal calf serum. Caco-2 cell lines maintained under these conditions without antibiotics were used between passages 9 and 12. The gentamicin survival assay was used to estimate bacterial survival as follows. L. lactis strains were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.9 to 1.0, washed, and diluted such that the multiplicity of infection (MOI) was about 103 bacteria per cell. The bacterial suspension was added to mammalian cells grown in P-24 plates (Corning Glass Works). Amounts of 2 × 105 cells per well were used. After 1 h of coincubation, 20 μg/ml of gentamicin was added to kill noninternalized bacteria. After 2 h of gentamicin treatment, cells were washed and lysed in 0.2% Triton X-100 and serial dilutions of the lysate were plated for bacterial counting. The results presented correspond to the averages of the results of three independent gentamicin assays done in triplicate.

Preparation of protein extracts and analysis by Western blotting.

L. lactis protein extracts were prepared as previously described (3) from 2 ml of stationary phase cultures (OD600, 0.9 to 1.0). Equivalent amounts of protein extracts were resolved in denaturing conditions (sodium dodecyl sulfate-8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane as described previously (16). The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% (vol/vol) nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20 and then for 1 h at room temperature with a 1/2,000 dilution of a rabbit antiserum directed against the D region of FnBPA. The membrane was rinsed and incubated in PBS containing nonfat dry milk (5% vol/vol), 0.1% Tween 20, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (P.A.R.I.S) for 1 h at room temperature. Signals were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminiscence kit (Amersham Bioscience).

Analysis of bacterial internalization by confocal microscopy.

Amounts of 2 ml of stationary phase cultures of L. lactis, L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ were washed twice in PBS and stained with the green fluorescent dye carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) at 50 μM for 20 min at 37°C under constant shaking in the dark (14). Bacteria were washed in PBS and used to perform invasiveness assays with Caco-2 cells grown as described above on glass coverslips pretreated with 10 μg/ml poly-d-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). After 1 h of infection and 2 h of incubation in the presence of gentamicin (20 μg/ml), cells were fixed for 20 min with paraformaldehyde (2.5% in PBS) and permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.1%) for 5 min at room temperature. The actin cytoskeleton was stained with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled phalloidin (Invitrogen) in PBS containing bovine serum albumin (1%) for 20 min at room temperature. Samples were mounted with Fluoromount G medium (Interchim), and the images were captured by using a Zeiss LSM 510 META inverted confocal laser-scanning microscope equipped with an argon and a helium-neon laser (for double fluorescence at 488 and 543 nm) and with a Zeiss 63× Plan-Apochromat lens. A composite picture of 39 to 44 sections (0.41 μm or 0.8 μm apart in the z axis) of each sample was collected and analyzed using Zeiss LSM Image Browser software (version 4.2).

Analysis of bacterial internalization by conventional immunofluorescence microscopy.

An antiserum directed against L. lactis was prepared by immunizing a rabbit with bacterial wall extracts. Specific response against the bacterium was checked by using an agglutination test and indirect immunofluorescence as described below. Caco-2 cells were grown on glass coverslips pretreated with poly-d-lysine. An invasiveness assay with CFSE-stained L. lactis was performed as described above. After 1 h of infection and 2 h of incubation in the presence of gentamicin (20 μg/ml), cells were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Noninternalized L. lactis were visualized by using rabbit anti-L. lactis serum (diluted 1/100) as primary antibody followed by Alexa Fluor 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Invitrogen) as secondary antibody. The nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidinophenylindole (DAPI). Samples were mounted as described above and analyzed with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a 20× Zeiss LD A-Plan phase-contrast lens and a CoolSNAP HQ camera (Roper Scientific). For each field observed, a phase-contrast image and fluorescence images in the blue, red, and green channels were acquired and processed using MetaVue (version 6.3; Molecular Devices) and ImageJ (version 1.38; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) software.

Analysis of GFP expression by Caco-2 cells using flow cytometry.

The gfp open reading frame under the control of the eukaryotic immediate early promoter of the human cytomegalovirus was used to demonstrate the potential of L. lactis to deliver a functional gene into the Caco-2 mammalian cell line. L. lactis InlA+ GFP, L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP, L. lactis CD+ GFP, and L. lactis GFP were grown to an OD600 of 0.9 to 1.0, and bacteria were added to cells at a MOI of 103. Internalization assays with these strains were performed as described above. After 1 h or 3 h of infection, cells were incubated in RPMI medium with gentamicin (20 μg/ml) for 2 h. Cells were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h; rinsed with PBS; and fixed (Cell fix; BD Biosciences). Quantification of fluorescent cells was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest Pro software (Becton Dickinson). For each interaction experiment, 500,000 cells were analyzed. Assays were performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

Production of FnBPA and its CD domains by recombinant L. lactis strains.

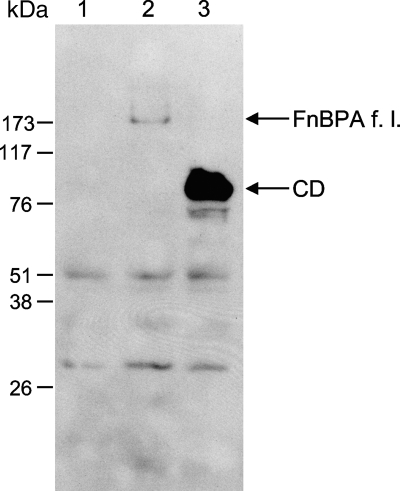

We first checked the production of full-length FnBPA and its CD domains by L. lactis FnBPA+ and L. lactis CD+, respectively. Western blot analysis was performed using a polyclonal antiserum specific for domain D of FnBPA. Neither FnBPA nor CD was detected in wt L. lactis (negative-control strain) (Fig. 1, lane 1). However, proteins with the expected size were clearly detected for L. lactis FnBPA+ (Fig. 1, lane 2) and L. lactis CD+ (Fig. 1, lane 3).

FIG. 1.

Detection of S. aureus fibronectin binding protein A or its C and D domains in L. lactis by Western blot analysis. Cell extracts from cultures of recombinant L. lactis producing either S. aureus FnBPA or its C and D domains were analyzed by Western blotting using a rabbit antiserum against domain D of FnBPA. Lane 1, wt L. lactis; lane 2, L. lactis FnBPA+; lane 3, L. lactis CD+. f. l., full-length.

The L. lactis strain producing FnBPA internalizes in Caco2 cells as efficiently as the same strain expressing InlA.

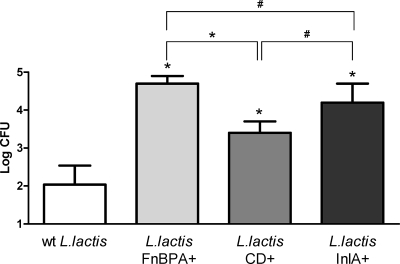

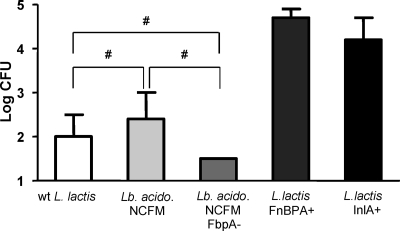

The ability of L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ to invade Caco-2 cells was evaluated using the classical gentamicin survival assay that allows global quantification of viable intracellular bacteria. The results presented in Fig. 2 clearly show that L. lactis FnBPA+ and L. lactis InlA+ displayed similar internalization rates in Caco-2 cells, whereas L. lactis CD+ internalized less efficiently than L. lactis FnBPA+.

FIG. 2.

Assays of invasiveness of L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ on Caco-2 cells. Amounts of 2 × 105 Caco-2 cells were used for each assay. wt L. lactis was used as negative control. Results are means ± standard deviations from triplicates. Error bars represent standard deviations. The results presented are from one experiment representative of three performed independently. *, survival rate was significantly different from that obtained for wt L. lactis; #, survival rates were statistically comparable (the Student t test, P < 0.05).

Microscopic visualization of internalized L. lactis producing InlA, FnBPA, and CD reveals cytoplasmic bacterial clusters unevenly distributed in Caco-2 cells.

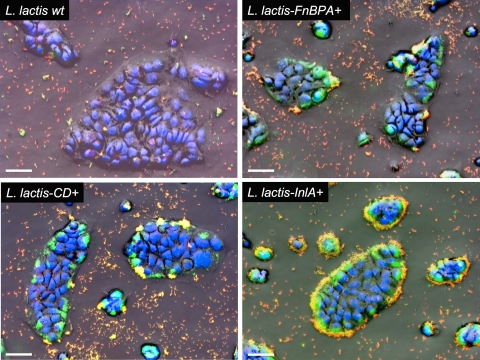

To confirm our previous result and to determine more precisely the fate and cellular location of the different Lactococcus strains after internalization in Caco-2 cells, we tried to localize bacteria inside the cells using fluorescence microscopy techniques. Bacteria were stained with the green vital fluorescent dye CFSE. After the staining, the four different strains (L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, L. lactis InlA+, and the control wt L. lactis) were incubated for 1 h with Caco-2 cells seeded at low density to obtain small isolated islets of cells. Noninternalized bacteria were then killed by treatment with gentamicin.

We first used conventional fluorescence microscopy to visualize internalized bacteria in situ (Fig. 3). Cell monolayers were thus fixed without permeabilization and noninternalized, extracellular bacteria were specifically stained for visualization by indirect immunofluorescence using an anti-L. lactis serum and a red fluorophore. Consequently, on three-color (green, red, and blue) overlay photographs, doubly stained noninternalized bacteria appeared orange to yellow and singly stained intracellular bacteria appeared green. After incubation with wt L. lactis, almost no intracellular bacteria could be detected. In contrast, intracellular bacteria were detected in the cytoplasm of Caco-2 cells after coculture with the three invasive lactococcal strains. They were not evenly distributed in the cell islets but were preferentially detected in cells located at the periphery of the islets, where they form intracytoplasmic clusters that seem to contain up to several tens of bacteria. This heterogeneous location suggests that InlA and FnBPA receptors are more accessible at the periphery of the islets. Moreover, the intracellular distribution appeared more homogeneous for L. lactis InlA+. Noninternalized bacteria could be observed almost exclusively outside the cellular islets or attached at the surface of the cells.

FIG. 3.

L. lactis internalization in Caco-2 cells analyzed by conventional fluorescence microscopy. The CFSE-stained (green) bacteria (wt L. lactis, L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+) were coincubated with Caco-2 cells for 1 h to perform internalization and fixed without permeabilization. Extracellular, noninternalized bacteria were stained with Alexa Fluor 594 (red) for visualization by indirect immunofluorescence using an anti-L. lactis serum. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The samples were analyzed by conventional fluorescence microscopy. Each panel represents the overlay of the inverted phase-contrast image of the field and the three fluorescence images acquired in the blue, red, and green channels. Intracellular bacteria appear in green, and extracellular bacteria in orange to yellow. Large clumps of intracellular bacteria are clearly visible in samples with internalizing strains. Bars, 50 μm.

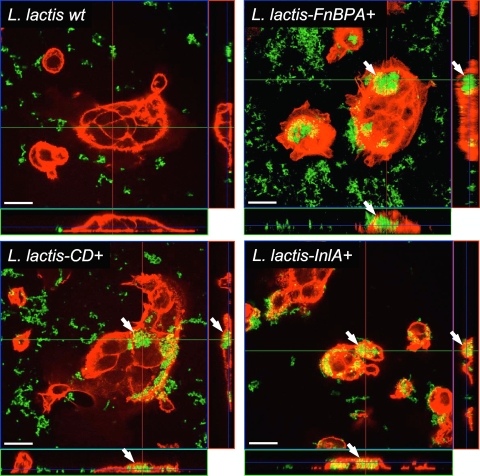

To eliminate the possibility of an artifact of the detection method, we confirmed these results with confocal microscopy. To clearly visualize intracellular CFSE-stained bacteria, Caco-2 cells were stained for cytoplasmic filamentous actin with phalloidin labeled with a red fluorophore. Virtual z sections generated by confocal analysis (Fig. 4) clearly showed that coculture of Caco-2 cells with the three internalizing lactococcus strains results in the formation of large clusters of internalized bacteria in Caco-2 cells. In contrast, neither intracellular nor cell-associated bacteria could be detected after coculture with wt L. lactis.

FIG. 4.

L. lactis internalization in Caco-2 cells analyzed by confocal microscopy. The CFSE-stained (green) bacteria (wt L. lactis, L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+) were coincubated with Caco-2 cells for 1 h to perform internalization, and the actin cytoskeleton was stained by phalloidin (red) after fixation and permeabilization. The fluorescent samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Each panel represents a section from the stack on the z axis appropriately chosen to visualize both extracellular and intracellular bacteria. For each field, two three-dimensional reconstruction sections perpendicular to the plane of the monolayer and parallel to the x or y axis are shown below (x-z section, green line) and to the right (y-z section, red line) of each panel. Clumps of several tens of bacteria per Caco-2 cell (white arrows) are clearly visible for internalizing strains. Bars, 20 μm.

Fibronectin binding protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM does not mediate internalization in Caco-2 cells.

Fibronectin binding proteins are widely distributed among bacteria, including LAB such as lactococci and lactobacilli, in which they have a clear role in adhesion to epithelial cells (1). In order to test whether fibronectin binding could represent a more general mode of bacterial entry into cells, we tested whether such protein from the commensal Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM could be involved, even at a very low level, in internalization. We thus compared the rates of invasiveness in Caco-2 cells of the wt strain and the mutant strain with the gene encoding the fibronectin-binding protein FbpA deleted. The wt L. lactis strain (which also carries one FbpA-encoding gene) and our recombinant invasive strains (L. lactis FnBPA+ and L. lactis InlA+) were also included in this comparison assay. As shown in Fig. 5, wt L. lactis, L. acidophilus NCFM, and L. acidophilus with fbpA inactivated showed very similar internalization rates, which were significantly lower than the rates obtained with L. lactis FnBPA+ or L. lactis InlA+. This showed that the L. acidophilus FbpA protein, despite its well-documented role in adhesion, does not confer invasive properties to this bacterium. Even if there is “natural” background internalization of L. acidophilus in Caco-2 cells, it is not mediated by the fbpA gene product.

FIG. 5.

Assays of invasiveness of L. acidophilus NCFM, L. acidophilus NCFM with fbpA inactivated, L. lactis FnBPA+, and L. lactis InlA+ with Caco-2 cells. Amounts of 2 × 105 Caco-2 cells were used in each assay. wt L. lactis was used as the negative control. Results are means ± standard deviations of triplicates. Error bars represent standard deviations. The results presented are from one experiment representative of three performed independently. #, survival rates were statistically comparable (the Student t test, P < 0.05); Lb. acido., L. acidophilus; fbpA-, deletion of fibronectin binding protein-encoding gene.

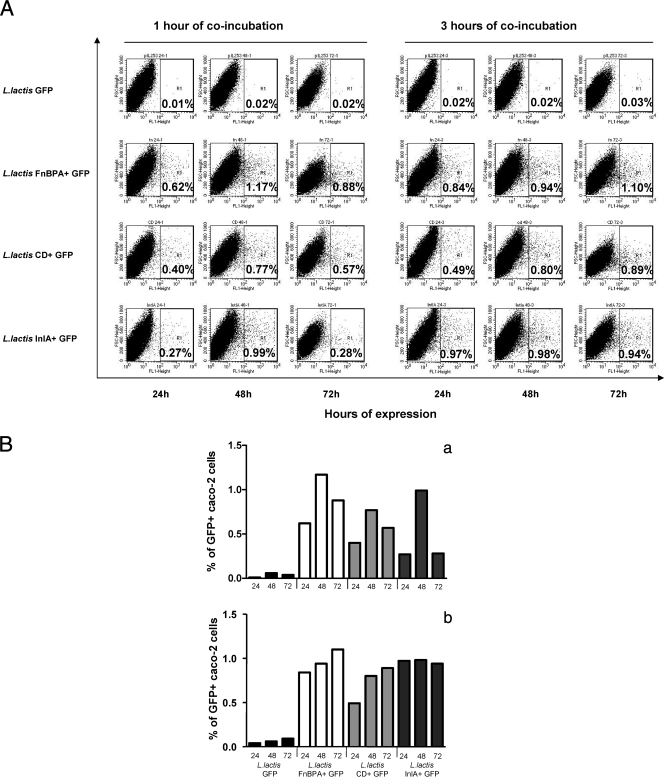

Efficient in vitro delivery of a eukaryotic expression vector by L. lactis strains expressing FnBPA.

To demonstrate that FnBPA and its CD domains can mediate in vitro gene delivery when produced by L. lactis and to compare the DNA delivery abilities of the different invasive strains, we transformed L. lactis FnBPA+, L. lactis CD+, and L. lactis InlA+ and the noninvasive wt L. lactis strain with pValac:GFP, a plasmid carrying a eukaryotic GFP expression cassette (8), resulting in L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP, L. lactis CD+ GFP, L. lactis InlA+ GFP, and L. lactis GFP, respectively (Table 1). Caco-2 cells were cocultivated with these strains for 1 or 3 h, and the percentage of Caco-2 cells expressing GFP was monitored by flow cytometry after 24, 48, and 72 h of gentamicin treatment. Almost no GFP expression could be detected with the noninvasive strain (Fig. 6A). The 1-h incubation condition elicited transitory expression of GFP, with a maximum at 48 h after gentamicin treatment (Fig. 6B). After 3 h of cocultivation, the percentage of Caco-2 cells expressing GFP reached a maximum 24 h after gentamicin treatment and then remained constant when L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP and L. lactis InlA+ GFP were used. When L. lactis CD+ GFP was used, GFP expression reached its maximum only 48 h after gentamicin treatment. The percentages of Caco-2 cells expressing GFP were the same 3 days after gentamicin treatment for the three invasive strains used. These results clearly demonstrate that (i) the L. lactis strains expressing either full-length FnBPA or its CD domains can efficiently mediate in vitro intracellular delivery of a functional eukaryotic expression plasmid and (ii) the highest percentages of green fluorescent Caco-2 cells were obtained after coculture with L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP or L. lactis InlA+ GFP.

FIG. 6.

In vitro gene transfer assessment following invasion of Caco-2 cells by L. lactis strains carrying pValac:GFP plasmid. (A) The percentages of Caco-2 cells expressing GFP following coincubation for 1 h or 3 h with L. lactis GFP, L. lactis FnBPA+ GFP, L. lactis CD+ GFP, and L. lactis InlA+ GFP were determined by flow cytometry at 24, 48, and 72 h after coincubation using the positivity threshold indicated on the FL1/FSC dot-plots. (B) The values obtained were reported in graphs for a better comparison. (a) Values following 1 h of incubation. (b) Values following 3 h of incubation. The flow cytometry assays shown here are from one experiment representative of three performed independently. FL1, relative fluorescence intensity in the green channel; FSC, forward scatter.

DISCUSSION

LAB represent an attractive alternative to attenuated pathogenic bacteria as DNA delivery vehicles. We demonstrated previously for the first time that a fully functional plasmid can be transferred with low efficiency from a LAB transiting in the gut to intestinal cells: the oral administration of L. lactis strains carrying a plasmid containing a eukaryotic BLG expression cassette elicited transitory BLG production by the epithelial cells of the intestinal wall. Mice treated with this noninvasive strain developed a BLG-specific TH1 immune response and were protected from further sensitization (2).

To improve plasmid DNA delivery by lactococci, we developed invasive lactococcal strains, like L. lactis InlA+ (9), whose internalization is mediated through the binding of InlA to E-cadherin expressed on epithelial/endothelial cells (15). This interaction is species specific, since InlA interacts with human E-cadherin but not with its homolog in some rodents, including mice (12). This observation excludes mice as an experimental model to study InlA-mediated DNA delivery improvement in vivo, although it was recently reported that two single substitutions in InlA increased binding affinity to formerly incompatible murine E-cadherin by four orders of magnitude, extending its binding specificity (31). This recent finding opens the possibility of expressing this mutated InlA in lactococci and using the mutants in conventional mice. As this limitation does not exist with guinea pigs, we used this animal model in our previous study to demonstrate the ability of L. lactis InlA+ to invade intestinal cells in vivo (7).

In order to explore the potential use of other bacterial internalins allowing further animal experiments for mucosal DNA delivery, we analyze here the binding and internalizing properties of S. aureus FnBPA and its ability to confer DNA delivery properties to L. lactis. This invasin would be more suitable for further in vivo studies because it has many binding regions and could be used in a wider range of animal models. Here, we show that cell wall-anchored full-length FnBPA promotes the entry of L. lactis into Caco-2 cells as efficiently as InlA and confers to the bacteria very similar plasmid DNA delivery properties, as judged by its ability to transfer a pValac:GFP plasmid into Caco-2 cells to elicit GFP expression. Moreover, we provide microscopic evidence of FnBPA- and InlA-mediated L. lactis internalization that raises interesting questions about the process of internalization of these genetically modified bacteria.

Staphylococcus aureus FnBPA was the first surface protein of bacterial pathogens shown to be sufficient to confer invasivity on L. lactis for entry into human 293 embryonic kidney cells (27). In this study, we confirm with the human Caco-2 intestinal cell line that full-length FnBPA and its CD domain can mediate L. lactis internalization. Moreover, we compare the internalization and DNA delivery abilities of L. lactis expressing S. aureus FnBPA or CD and L. lactis expressing L. monocytogenes InlA. The rates of invasiveness of L. lactis InlA+ and L. lactis FnBPA+ determined after the gentamicin treatment were similar and about 1,000-fold higher than that obtained with the wt L. lactis strain. In contrast, L. lactis CD+ exhibited a significantly lower rate of invasiveness than L. lactis FnBPA+. In order to explore the possibility that bacterial fibronectin binding proteins, especially those from nonpathogenic bacteria, could be more widely involved in bacterial internalization, we analyzed whether the FbpA protein from the nonpathogenic commensal organism L. acidophilus NCFM could mediate a “natural” low level internalization as we previously showed for L. lactis (9, 10). It would have been possible subsequently to improve this internalization by constructing recombinant strains overexpressing this protein. However, our results with the mutant with fbpA inactivated indicate that if this background internalization exists, it is not mediated by FbpA but by other proteins. Thus, fibronectin binding proteins are not universal promoters of bacterial internalization and those from pathogenic bacteria probably trigger specific signals in host cells that are necessary for efficient entry. This suggests that two different classes of fibronectin binding proteins can be distinguished, those from pathogenic bacteria conferring both cell adhesion and internalization and those from either food-grade or commensal bacteria conferring only cell adhesion.

One of the two main original interests of our paper was (i) to confirm internalization data by direct visualization of recombinant lactococci expressing InlA and FnBPA inside cells using conventional and confocal microscopy and (ii) to analyze precisely their cellular and subcellular locations after internalization in vitro, which was never done before. In previous papers (9, 10, 27), the internalization process was evaluated using only an antibiotic resistance assay similar to the one used in the present study. However, this assay suffers some bias: when a high MOI is used, bacteria can form a biofilm at the surface of the cells and remain protected from the antibiotic treatment although they are not internalized. The visualization experiments performed in our work clearly discard this artifact. Moreover, they provide interesting information about the localization and numbers of bacteria inside the Caco-2 cell islets. Our images clearly show that both invasins drive lactococci to a similar cytoplasmic location in Caco-2 cells. The preferential distribution of internalized bacteria at the periphery of the Caco-2 cell islets can be explained by the fact that E-cadherin and α5β1 integrins (15, 28), the respective InlA and FnBPA receptors, are accessible at the periphery but not at the center of the Caco-2 cell islets. However, the surprisingly high number of bacteria detected in the cells in which internalization occurred is a point that remains difficult to explain. Two nonexclusive mechanisms could be involved: (i) massive internalization of several tens of bacteria in a single cell through their binding to fibronectin or E-cadherin, leading to the formation of a complex subsequently internalized by the eukaryotic cells as a single unit, and (ii) intracellular multiplication of a few internalized bacteria. Although the latter possibility appears less probable, as the time left after the beginning of the gentamicin treatment is probably too short to allow lactococcal multiplication in the unfavorable intracytoplasmic environment, further work is required to clarify the mechanisms involved.

Another important point of our work was to demonstrate for the first time that L. lactis bacteria expressing FnBPA can efficiently deliver a eukaryotic expression plasmid, with subsequent protein expression, thus indicating that this bacterial invasin can be used for plasmid delivery. It is known that FnBPA increases both the adherence of L. lactis to immobilized fibronectin and its infectivity in experimental endocarditis to levels similar to those observed for S. aureus, thus identifying FnBPA as a critical virulence factor in endovascular infection (18). This raises the question of the safety of Lactococcus strains expressing this protein. A previous study showed that L. lactis expressing FnBPA or its CD domains can cause valvular lesions in rats. However, this occurs only when lactococci are injected by the parenteral route to animals that have preexisting valvular lesions. The conditions used in mucosal immunization, i.e., local administration at a mucosal surface of a healthy animal, cannot result in a massive release of recombinant bacteria in the bloodstream and can consequently be considered much safer. The results of flow cytometry analysis indicate that around 1% of Caco-2 cells expressed GFP after coincubation with the FnBPA-expressing invasive strains bearing the pValac:GFP plasmid, while no fluorescence was detectable with the noninvasive strain bearing this plasmid. These results prove the ability of these invasive strains to transfer functional plasmids in Caco-2 cells as efficiently as those expressing InlA. Consequently, these results indicate that L. lactis expressing FnBPA represents a promising tool for mucosal DNA delivery that will be tested in vivo in future experiments using the mouse model.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Philippe Moreillon (Department of Fundamental Microbiology, University of Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing us with the L. lactis strains expressing S. aureus FnBPA and its derivatives. We also thank Todd Klaenhammer (Department of Food, Bioprocessing, and Nutrition Sciences, North Carolina State University) for the Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM strain and its fbpA mutant and Martin McGavin (Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada) for the anti-FnBPA antiserum. We are very grateful to René L'Haridon (INRA Jouy-en-Josas) for the preparation and testing of the anti-L. lactis serum and to Céline Urien (INRA Jouy-en-Josas) for confocal microscopy analyses that were performed at the MIMA2 microscopy platform of the INRA Jouy-en-Josas research center.

Valeria Guimarães received grants from the Region of Ile-de-France and Animal Health Division of INRA (convention no. E1511). Silvia Innocentin is a recipient of a European Marie Curie Ph.D. grant from the LABHEALTH program (MEST-CT-2004-514428).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buck, B. L., E. Altermann, T. Svingerud, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Functional analysis of putative adhesion factors in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8344-8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatel, J. M., L. Pothelune, S. Ah-Leung, G. Corthier, J. M. Wal, and P. Langella. 2008. In vivo transfer of plasmid from food-grade transiting lactococci to murine epithelial cells. Gene Ther. 15:1184-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieye, Y., S. Usai, F. Clier, A. Gruss, and J. C. Piard. 2001. Design of a protein-targeting system for lactic acid bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:4157-4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dramsi, S., I. Biswas, E. Maguin, L. Braun, P. Mastroeni, and P. Cossart. 1995. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of inIB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol. Microbiol. 16:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunham, S. P. 2002. The application of nucleic acid vaccines in veterinary medicine. Res. Vet. Sci. 73:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasson, M. J. 1983. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J. Bacteriol. 154:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grillot-Courvalin, C., S. Goussard, F. Huetz, D. M. Ojcius, and P. Courvalin. 1998. Functional gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 16:862-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guimaraes, V., S. Innocentin, J. M. Chatel, F. Lefevre, P. Langella, V. Azevedo, and A. Miyoshi. 2009. A new plasmid vector for DNA delivery using lactococci. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guimaraes, V. D., J. E. Gabriel, F. Lefevre, D. Cabanes, A. Gruss, P. Cossart, V. Azevedo, and P. Langella. 2005. Internalin-expressing Lactococcus lactis is able to invade small intestine of guinea pigs and deliver DNA into mammalian epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 7:836-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guimaraes, V. D., S. Innocentin, F. Lefevre, V. Azevedo, J. M. Wal, P. Langella, and J. M. Chatel. 2006. Use of native lactococci as vehicles for delivery of DNA into mammalian epithelial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7091-7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langella, P., Y. Le Loir, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1993. Efficient plasmid mobilization by pIP501 in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. J. Bacteriol. 175:5806-5813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecuit, M., S. Dramsi, C. Gottardi, M. Fedor-Chaiken, B. Gumbiner, and P. Cossart. 1999. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity towards the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 18:3956-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292:1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, Y. K., P. S. Ho, C. S. Low, H. Arvilommi, and S. Salminen. 2004. Permanent colonization by Lactobacillus casei is hindered by the low rate of cell division in mouse gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:670-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R. M. Mege, and P. Cossart. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84:923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peacock, S. J., N. P. Day, M. G. Thomas, A. R. Berendt, and T. J. Foster. 2000. Clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus exhibit diversity in fnb genes and adhesion to human fibronectin. J. Infect. 41:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Que, Y. A., P. Francois, J. A. Haefliger, J. M. Entenza, P. Vaudaux, and P. Moreillon. 2001. Reassessing the role of Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor and fibronectin-binding protein by expression in Lactococcus lactis. Infect. Immun. 69:6296-6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Que, Y. A., J. A. Haefliger, P. Francioli, and P. Moreillon. 2000. Expression of Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor A in Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris using a new shuttle vector. Infect. Immun. 68:3516-3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Que, Y. A., J. A. Haefliger, L. Piroth, P. Francois, E. Widmer, J. M. Entenza, B. Sinha, M. Herrmann, P. Francioli, P. Vaudaux, and P. Moreillon. 2005. Fibrinogen and fibronectin binding cooperate for valve infection and invasion in Staphylococcus aureus experimental endocarditis. J. Exp. Med. 201:1627-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche, F. M., R. Downer, F. Keane, P. Speziale, P. W. Park, and T. J. Foster. 2004. The N-terminal A domain of fibronectin-binding proteins A and B promotes adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to elastin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:38433-38440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., F. E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 22.Sanders, M. E., and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2001. Invited review: the scientific basis of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM functionality as a probiotic. J. Dairy Sci. 84:319-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoen, C., J. Stritzker, W. Goebel, and S. Pilgrim. 2004. Bacteria as DNA vaccine carriers for genetic immunization. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 294:319-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz-Linek, U., M. Hook, and J. R. Potts. 2006. Fibronectin-binding proteins of gram-positive cocci. Microbes Infect. 8:2291-2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz-Linek, U., M. Hook, and J. R. Potts. 2004. The molecular basis of fibronectin-mediated bacterial adherence to host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 52:631-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon, D., and A. Chopin. 1988. Construction of a vector plasmid family and its use for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie 70:559-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinha, B., P. Francois, Y. A. Que, M. Hussain, C. Heilmann, P. Moreillon, D. Lew, K. H. Krause, G. Peters, and M. Herrmann. 2000. Heterologously expressed Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding proteins are sufficient for invasion of host cells. Infect. Immun. 68:6871-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha, B., P. P. Francois, O. Nusse, M. Foti, O. M. Hartford, P. Vaudaux, T. J. Foster, D. P. Lew, M. Herrmann, and K. H. Krause. 1999. Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin α5β1. Cell. Microbiol. 1:101-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wann, E. R., S. Gurusiddappa, and M. Hook. 2000. The fibronectin-binding MSCRAMM FnbpA of Staphylococcus aureus is a bifunctional protein that also binds to fibrinogen. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13863-13871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells, J. M., and A. Mercenier. 2008. Mucosal delivery of therapeutic and prophylactic molecules using lactic acid bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:349-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wollert, T., B. Pasche, M. Rochon, S. Deppenmeier, J. van den Heuvel, A. D. Gruber, D. W. Heinz, A. Lengeling, and W. D. Schubert. 2007. Extending the host range of Listeria monocytogenes by rational protein design. Cell 129:891-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]