Abstract

The ammonia-oxidizing prokaryote (AOP) community in three groundwater treatment plants and connected distribution systems was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR and sequence analysis targeting the amoA gene of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and archaea (AOA). Results demonstrated that AOB and AOA numbers increased during biological filtration of ammonia-rich anoxic groundwater, and AOP were responsible for ammonium removal during treatment. In one of the treatment trains at plant C, ammonia removal correlated significantly with AOA numbers but not with AOB numbers. Thus, AOA were responsible for ammonia removal in water treatment at one of the studied plants. Furthermore, an observed negative correlation between the dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentration in the water and AOA numbers suggests that high DOC levels might reduce growth of AOA. AOP entered the distribution system in numbers ranging from 1.5 × 103 to 6.5 × 104 AOPs ml−1. These numbers did not change during transport in the distribution system despite the absence of a disinfectant residual. Thus, inactive AOP biomass does not seem to be degraded by heterotrophic microorganisms in the distribution system. We conclude from our results that AOA can be commonly present in distribution systems and groundwater treatment, where they can be responsible for the removal of ammonia.

Ammonia can be present in source water used for drinking water production or added to treated water with chlorine to form chloramines as a disinfectant. However, the presence of ammonia in drinking water is undesirable because nitrification might lead to toxic levels of nitrite (29) or adverse effects on water taste and odor (4) and might increase heterotrophic bacteria, including opportunistic pathogens (29). Two-thirds of the drinking water in The Netherlands is produced from groundwater. Most of the groundwater used for drinking water production is anoxic with relatively high concentrations of methane, iron, manganese, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and ammonia. Treatment of anoxic groundwater aims at achieving biologically stable water, because drinking water in The Netherlands is distributed without a disinfectant residual. As a result, a highly efficient nitrification process during rapid medium filtration is required.

Nitrification is the microbial oxidation of ammonia to nitrate and consists of two processes: the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite by ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes (AOP) and the oxidation of nitrite to nitrate by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB). Recently it was shown that in addition to bacteria, archaea also are capable of ammonia oxidation (13). Since then, ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) have been found in many different ecosystems, including wastewater treatment systems (10, 20, 24). However, it is currently unknown if AOA are present in drinking water treatment processes and distribution systems. Recent studies have focused on nitrification in drinking water treatment (16, 28). In those studies, AOB and NOB were enumerated by traditional most-probable-number (MPN) methods using selective liquid media. However, MPN methods are time-consuming and underestimate the numbers of AOP and NOB (3). Quantitative real-time PCR has been used to quantify AOB in drinking water (12) and might be a useful tool for quantifying AOB and AOA in drinking water.

In our study, a real-time PCR method targeting the amoA gene of AOB or AOA was developed to quantify numbers of AOP in drinking water. This real-time PCR method was used together with a phylogenetic analysis of the amoA gene of AOB and AOA to do the following: (i) determine the treatment steps where AOP dominates in the groundwater treatment train of three drinking water production plants in The Netherlands, (ii) quantify the AOP entering the distribution system and determine the fate of AOP during transport in the distribution system, and (iii) elucidate the role of AOA in nitrification during drinking water treatment and in distribution systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Water samples were taken from drinking water treatment and the distribution systems of water treatment plants A, B, and C. The oxic groundwater of plant A is treated with limestone filtration. The treatment train of the anoxic groundwater of plant B consists of plate aeration, first rapid sand filtration, tower aeration, water softening, and second rapid sand filtration. Treatment plant C uses anoxic groundwater from a deep and middle-deep aquifer. The treatment train of the middle-deep groundwater consists of tower aeration, first rapid sand filtration, KMnO4 dosing, second rapid sand filtration, granular activated carbon (GAC) filtration, and UV. The treatment train of the deep groundwater consists of tower aeration, water softening, HCl dosing, and rapid multimedium (sand/anthracite) filtration. In general, 100 ml of raw water, 100 ml of water after each treatment step, and 100 ml of finished water were taken at all three treatment plants. The distribution systems of plants A, B, and C were analyzed by sampling 100 ml water at the tap of three different house addresses at the proximal, central, and distal parts of the distribution system (resulting in a total of nine samples per distribution system). All water samples were stored at 4°C and processed within 24 h.

DNA isolation.

In general, 100 ml of a water sample was filtrated over a 25-mm polycarbonate filter (0.22-μm pore size, type GTTP; Millipore, The Netherlands). The filter and a DNA fragment of an internal control were added to phosphate and MT buffer of the FastDNA Spin kit for soil (Qbiogene) and stored at −20°C. The internal control was used to determine the PCR efficiency. DNA was isolated using the FastDNA Spin kit for soil according to the supplier's protocol.

Real-time PCR for amoA genes of AOB and AOA.

The amoA genes of AOB and AOA were amplified with previously described primers (10, 22). Reaction mixtures of 50 μl contained 25 μl of 2× IQTM SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories BV, The Netherlands), 10 pmol of forward and reverse primer, and 20 μg bovine serum albumin. Amplification, detection, and data analysis were performed in an iCycler IQ real-time detection system (Bio-Rad laboratories BV, The Netherlands). The amplification program used was as follows: 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The PCR cycle after which the fluorescence signal of the amplified DNA is detected (threshold cycle [CT]) was used to quantify the concentration of AOB and AOA amoA gene copies. Quantification was based on comparison of the sample CT value with the CT values of a calibration curve based on known copy numbers of the amoA gene of AOB or AOA. The AOB numbers were calculated by assuming two amoA gene copy numbers per cell (5) and the AOA numbers by assuming one amoA gene copy number per cell (18).

Phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic analyses of the amoA genes of AOB and AOA were performed on water sampled at the treatment train and distribution system of groundwater treatment plants A, B, and C. DNA was isolated from the water samples, and the amoA genes of AOB and AOA were amplified as described above. PCR products were purified using the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, The Netherlands) according to the supplier's protocol. Subsequently, PCR products were cloned into Escherichia coli JM109 by using the pGEM-T Easy Vector system (Promega, The Netherlands). Inserts were amplified with pGEM T Easy Vector-specific primers T7 and SP6, using the following PCR conditions: 94°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 48°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and finally 72°C for 7 min. About 48 PCR products of the amoA gene of AOB and 48 PCR products of the amoA gene of AOA with the correct insert size from each sample were sequenced using pGEM-T Easy Vector primer T7 (Baseclear, The Netherlands).

The computer program DOTUR was used to determine amoA gene sequences with more than 98% sequence similarity (23), at which sequences were considered to belong to the same operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (10). Similarity between samples was determined by comparing OTU presence and abundance using the Morisita index for similarity (27, 30). The amoA nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acid sequences, aligned by ClustalX, and manually checked. Sequences were compared with the GenBank data library using protein-protein and nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST to obtain the nearest phylogenetic relatives. Subsequently, evolutionary distances of the AmoA protein sequences were calculated using the Kimura correction model. Neighbor-joining trees with 1,000 bootstrap replicates were constructed using the computer program TreeConW. Chimeras were detected by comparing AmoA protein trees based on the first 100 to 200 bp and the last 100 to 200 bp. These trees gave the same phylogenetic structure, except for one bacterial AmoA protein sequence, which was omitted from the results.

Chemical analyses.

The ATP concentration was determined in water samples by measuring the amount of light produced in the luciferin-luciferase assay. A nucleotide-releasing buffer (Celsis) was added to the water sample to release ATP from the cells. The intensity of the emitted light was measured in a Celsis Advance luminometer calibrated with solutions of free ATP (Celsis) in autoclaved tap water according to the supplier's protocol. Orthophosphate was determined colorimetrically using the ascorbic acid method (ISO 6878:2004), ammonium was determined colorimetrically using the Kjeldahl method (according to the Dutch standard method NEN 6576), and DOC was measured using an infrared gas analyzer according to ISO 8245:1999.

Statistical analyses.

The data for AOB and AOA numbers in three parts of the distribution system (proximal, central, and distal) were statistically analyzed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) using general linear models with Bonferonni post hoc testing was used to determine differences between locations in the distribution net. Differences were considered statistically significant at P values of <0.05. All statistical procedures were calculated using the SPSS 16.0 software program.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

amoA gene sequences from this study are deposited in the GenBank library under accession numbers EU852659 to EU852722.

RESULTS

Real-time PCR.

A calibration curve with 10-fold dilutions of known copy numbers of the amoA gene of AOB and AOA was constructed to quantify the numbers of AOB and AOA by real-time PCR. Calibration curves for the amoA genes of AOB and AOA resulted in log linear relationships (with an r2 value above 0.99) between copy numbers and the CT in the range of 10 to 106 amoA gene copy numbers. The real-time PCR for the amoA genes of AOB and AOA showed high PCR efficiencies: 95.5% for the amoA gene of AOB and 94.8% for the amoA gene of AOA. Consequently, the developed real-time PCR methods for the amoA genes of AOB and AOA can be used to quantify AOB and AOA in drinking water samples.

AOP in groundwater treatment plants.

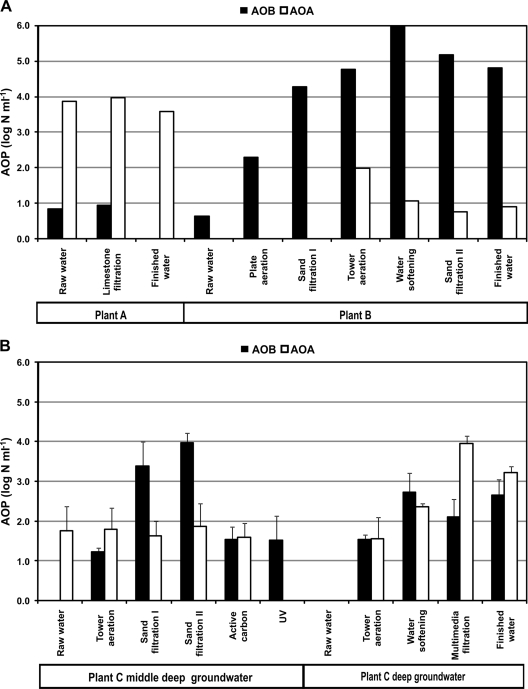

The chemical composition of the (an)oxic groundwater extracted by water treatment plants A, B, and C is shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Water treatment plant A extracts oxic groundwater with an ammonia concentration below the detection limit of 0.05 mg liter−1. The AOB numbers in the water sampled from the treatment train were low or not detectable (Fig. 1A). In contrast, AOA numbers were relatively high (1,000 times higher than those of AOB) and were not reduced by limestone treatment (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

The number of AOB and AOA in water sampled after different treatment stages at water treatment plants A and B (A) or at the middle-deep and deep extracted groundwater of water treatment plant C (B). Values for plants A and B were based on duplicate samples taken on a single day. Values for plant C were average numbers for duplicate samples taken on three different days during 2008.

Besides 3.4 mg liter−1 ammonia, the raw water of treatment plant B contains total organic carbon, Fe, Mn, and CH4 as well. During treatment, AOP reduce ammonia to concentrations below 0.05 mg liter−1. AOB were present in raw water at low numbers, and numbers increased in water sampled after plate aeration, the first rapid sand filter, tower aeration, and softening (Fig. 1A). In water sampled after the second rapid sand filter and in finished water, AOB numbers were lower, although numbers remained relatively high. AOA were not detected in water sampled after the first two treatment steps. In water sampled after tower aeration, low AOA numbers were present, and these numbers decreased in water sampled after softening and the second sand filter (Fig. 1A).

Groundwater treatment plant C extracts water from middle-deep and deep aquifer layers. Groundwater from these two depths differs in its geochemistry, with middle-deep groundwater having higher total organic carbon, Fe, and Mn concentrations. Both middle-deep and deep groundwater has an ammonia concentration of ∼1.0 mg liter−1, and this concentration is reduced to below 0.05 mg liter−1 in finished water. Raw water from the deep and middle-deep aquifer is anoxic, and consequently, AOB and AOA numbers were low or below the detection limit in raw water. In the treatment train of middle-deep extracted groundwater, the AOA numbers remained relatively stable until the UV treatment. Directly after UV treatment, AOA were no longer detected in the water (Fig. 1B). AOB numbers increased until the second sand filter but decreased during the last two treatment steps. For deep groundwater treatment, the number of AOB increased after tower aeration but remained relatively constant through the rest of the treatment train (Fig. 1B). In contrast, AOA increased until the multimedium filtration step. The finished water (a mix of treated middle-deep and deep groundwater) contained high AOB and AOA numbers.

The ammonia concentration removed at each treatment step in plant C was analyzed as well. The statistical characteristics of the correlations between ammonia removal at a specific treatment step and the number of AOP, AOB, or AOA in the water sampled directly after that treatment step are shown in Table 1. The ammonia concentration removed at each treatment step showed a significant and strong correlation with the log number of AOP in the water sampled after the treatment step. Thus, the AOP determined by the real-time PCR analysis were responsible for ammonia degradation in the treatment trains of plant C. For AOB, a strong, significant correlation was obtained with ammonia removal during treatment processes in the middle-deep extracted groundwater train (Table 1). No significant correlation was observed between AOB and ammonia removal in the treatment of deep extracted groundwater. In contrast, ammonia removal during treatment of the deep extracted groundwater correlated strongly with log numbers of AOA (Table 1). We conclude from these results that AOB are responsible for the removal of ammonia during treatment of the middle-deep groundwater, whereas AOA degrade ammonia in the treatment train of deep extracted groundwater.

TABLE 1.

Statistical characteristics of the correlations between the amount of ammonia removed at a treatment step and the log number of AOP, AOB, or AOA in water sampled directly after the treatment step at groundwater treatment plant C

| Sample type | Parameter 1 | Parameter 2 | Correlation between parameters

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | r2 value | |||

| Middle-deep and deep extracted groundwater | Ammonia removed (mg liter−1) | AOP (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.73 |

| AOB (log organisms ml−1) | 0.03 | 0.22 | ||

| AOA (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.45 | ||

| Middle-deep extracted groundwater | Ammonia removed (mg liter−1) | AOP (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.79 |

| AOB (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.78 | ||

| AOA (log organisms ml−1) | >0.1 | |||

| Deep extracted groundwater | Ammonia removed (mg liter−1) | AOP (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.77 |

| AOB (log organisms ml−1) | >0.1 | |||

| AOA (log organisms ml−1) | <0.01 | 0.86 | ||

To elucidate possible factors that determine whether AOB or AOA become dominant in the treatment trains of plant C, relationships between DOC, ATP, and orthophosphate and AOB, AOA, and AOP were studied. The DOC concentration in the water that feeds a treatment process where ammonia is removed had a significant positive correlation with AOB numbers in the water sampled directly behind the treatment process (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.57), whereas AOA numbers were significantly negatively correlated with the DOC concentration (P < 0.01; r2 = 0.56). ATP and orthophosphate concentrations in the water did not show any significant correlation with the number of AOB or AOA.

AOP in distribution systems.

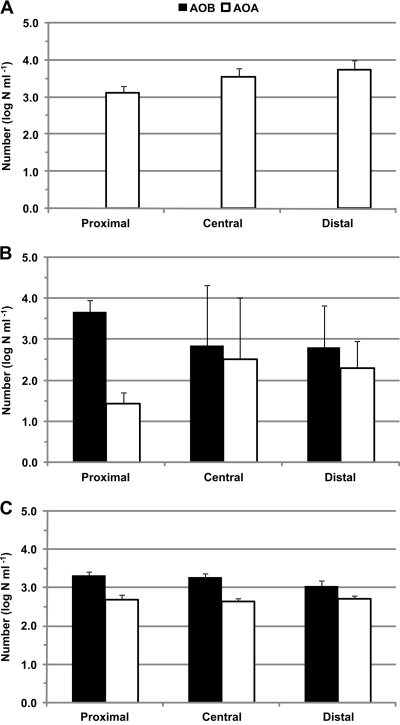

AOP were observed in all water samples from the distribution systems of the three water treatment plants (Fig. 2). The AOB numbers were relatively high in distribution water sampled from groundwater treatment plants B and C (Fig. 2B and C). AOB were not observed in water sampled from the distribution system of plant A. In contrast, the AOA numbers were relatively high in water sampled from the distribution system of plant A (Fig. 2A). AOA numbers in the distribution system of plants B and C were in general 10 to 100 times lower than those in the distribution system of plant A, but some sample locations in the distribution system of plant B had exceptions: water samples with low numbers of AOB (<1.2 or 1.6 log n ml−1) had relatively high numbers of AOA (4.2 or 3.0 log n ml−1). As a result, relatively high standard deviations were observed for AOB and AOA in water sampled from the distribution system of plant B.

FIG. 2.

The average numbers of AOB and AOA in the proximal, central, and distal parts of the distribution system of water treatment plants A, B, and C.

The AOB and AOA numbers were not significantly different between proximal, central, and distal parts of the distribution system of plants B and C (P > 0.05). In the distribution system of plant B, AOB numbers decreased with increasing distance from the treatment plant, whereas AOA numbers slightly increased (Fig. 2B), but these differences were not statistically significant. The AOA numbers increased from proximal to distal parts of the distribution system of plant A (Fig. 2A), and AOA numbers at the distal part of the distribution system were significantly higher than at the proximal part (P < 0.05).

Phylogenetic analyses.

The amoA gene sequences of AOB revealed a low number of OTUs in samples taken from the treatment train and the distribution system of treatment plants B and C (Table 2). Consequently, the Shannon diversity index was between 0 and 0.64 for most samples (Table 2). The OTU numbers based on the amoA gene sequences of AOA were generally higher than those for for AOB. Water sampled after limestone treatment and drinking water in the distribution system at plant A had a relatively high Shannon index, whereas the other samples had an index between 0 and 1.33 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

amoA gene sequences, OTU numbers, and Shannon index of diversitya

| Location | Analysis of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOB

|

AOA

|

|||||

| No. of seq | No. of OTUs | Shannon index | No. of seq | No. of OTUs | Shannon index | |

| Treatment plant A | ||||||

| Limestone | 0 | ND | ND | 48 | 10 | 1.93 |

| Distribution | 0 | ND | ND | 47 | 8 | 1.61 |

| Treatment plant B | ||||||

| Rapid sand filter I | 47 | 7 | 1.16 | ND | ND | ND |

| Tower aeration | 47 | 1 | 0 | 47 | 1 | 0 |

| Rapid sand filter II | 48 | 2 | 0.10 | 48 | 4 | 1.09 |

| Distribution system | 47 | 1 | 0 | 48 | 5 | 1.33 |

| Treatment plant C | ||||||

| Rapid sand filter I | ND | ND | ND | 48 | 5 | 1.13 |

| GAC filter | 12 | 2 | 0.64 | 34 | 4 | 1.08 |

| Rapid multimedia filter | 48 | 1 | 0 | 48 | 4 | 0.57 |

| Distribution system | 48 | 1 | 0 | 48 | 3 | 0.84 |

| Biofilm | 47 | 2 | 0.10 | 48 | 3 | 0.77 |

seq, sequences; ND, not detected.

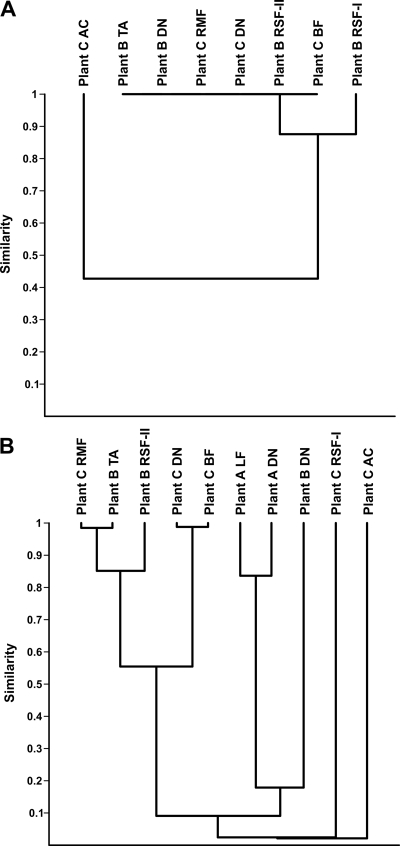

The Morisita similarity index between the AOB communities of most of the analyzed water and biofilm samples was around 1, indicating that these AOB communities had the same composition, irrespective of the water treatment plant (Fig. 3A). The Morisita index between the AOB community of the water sampled after the first rapid sand filter at plant B and the communities of the other samples was slightly lower, whereas the index between the AOB community in water sampled after GAC filtration at plant C and the AOB communities in the other samples was low (Fig. 3A). The Morisita index between the AOA community of water and biofilm sampled from the distribution system of plant C was high (Fig. 3B). Remarkably, the AOA community in water sampled after the rapid multimedium filter at plant C was highly similar to the AOA population in water sampled after tower aeration at plant B. The Morisita similarity index between the AOA communities of samples from plant A was high as well and clustered together in the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean analysis. In contrast, the index between AOA amoA gene sequences obtained from water sampled at the distribution system of plant B, water sampled after the first rapid sand filtration, and water sampled after GAC filtration of plant C were very low (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean cluster analysis based on the Morisita similarity index between the OTUs of the amoA gene sequences of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (A) or ammonia-oxidizing archaea (B). Abbreviations: AC, GAC filtration; BF, biofilm; DN, distribution system; LF, limestone filtration; RMF, rapid multimedia filter; RSF-I, first rapid sand filter; RSF-II, second rapid sand filter; TA, tower aeration.

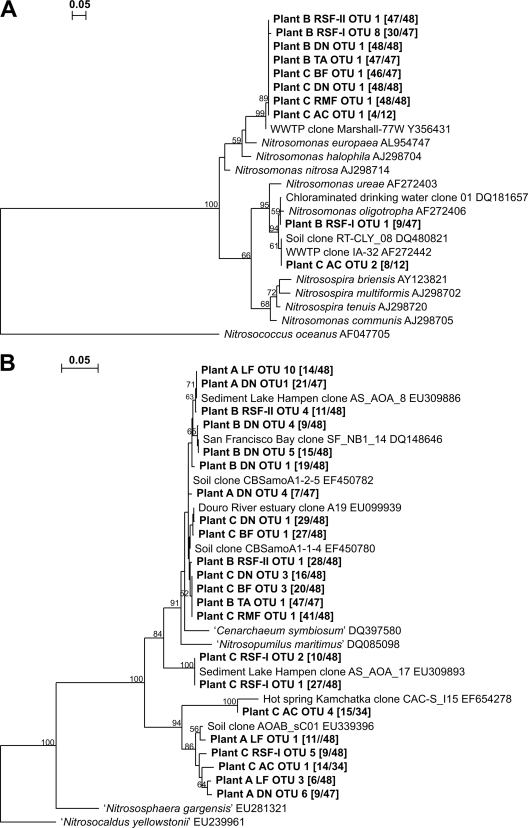

The dominant AOB amoA sequence in most water samples was related to a noncultured Nitrosomonas species (Fig. 4A). Apparently, this AOB species is capable of colonizing different water treatment systems and remains dominant in the distribution system (in both water and biofilm) as well. The dominant AOB amoA sequence in the water sampled after GAC filtration at plant C was related to sequences obtained from clone libraries constructed from wastewater, soil, and river sediment. Eight amoA sequences obtained from water sampled after the first rapid sand filter at plant B belonged to Nitrosomonas oligotropha (Fig. 4A). Most of the amoA sequences of AOA, obtained from water sampled in the treatment train of middle-deep groundwater at plant C and from water sampled after limestone treatment and in the distribution system of plant A, were related to sequences obtained from clone libraries constructed from soil and a hot spring (Fig. 4B). The remaining amoA sequences of AOA were related to sequences obtained from clone libraries constructed from soil, rhizosphere, and sediments from rivers, lakes, and estuaries (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on deduced amino acid sequences of the amoA gene sequences of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (A) or archaea (B). Only OTUs that had more than five sequences in a sample are shown. Trees were constructed with the neighbor-joining method using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Abbreviations are as in Fig. 3. Between brackets: sequence number belonging to that OTU/total sequence number. The bar represents a 5% evolutionary distance, and bootstrap values above 50% are shown. amoA gene sequences from this study are deposited in the GenBank library under accession numbers EU852706 to EU852722. “Nitrosopumilus maritimus,” “Nitrososphaera gargensis,” and “Nitrosocaldus yellowstonii” are “Candidatus” names.

DISCUSSION

Quantitative PCR.

Recent studies of nitrification in drinking water treatment or distribution systems used culturing methods to determine AOP numbers (16, 28) or fixed nitrifying biomass (14). The AOP numbers were determined with an MPN method using liquid culture medium for nitrifying bacteria. The fixed nitrifying biomass was determined by measuring the appearance rate of nitrite and nitrate produced by prokaryotes in a nitrifier medium. These methods underestimate the AOP number and biomass, because many environmental AOB and AOA are unable to grow in artificial growth medium (3). In addition, the MPN method takes approximately 4 to 9 weeks before MPN tubes can be scored positive or negative for growth (17). Some of the studies recognized these shortcomings, but the lack of an alternative method resulted in the use of the MPN method (6, 16). Moreover, Cunliffe (6) noted the pressing need for a fast quantification method for AOP in chlorinated distribution systems, because rapid diagnosis of increased AOP populations in the distribution system enables process controllers to react quickly and avoid use of excessive free chlorine in the system.

Real-time PCR methods have been used to quantify AOB numbers in drinking water (12). In our study, we developed two real-time PCR methods that quantified amoA copies of AOB and AOA in drinking water. The high correlation between amoA copy numbers and CT values and the high PCR efficiencies observed show that the real-time PCR methods are reliable tools for quantifying AOB and AOA in drinking water. Real-time PCR methods are fast and can detect both culturable and nonculturable AOP, which makes the method advantageous compared to culturing methods. Still, PCR methods detect DNA from both live and dead microorganisms, which might constrain viability analyses.

AOP in drinking water treatment and distribution system.

In The Netherlands, drinking water is distributed without a disinfectant. Raw water used for drinking water might contain ammonia, which is removed during biological filtration in the treatment plant. This nitrification process occurs at the surface of sand/anthracite or GAC filters (28). Consequently, it is generally assumed that nitrification occurs mainly in those treatment processes that involve biologically active filters (8). In contrast to this assumption, we observed relatively high AOP numbers in water sampled after water softening at plant C and in water sampled after tower aeration and water softening at plant B. The pivotal function of tower aeration is not nitrification but physical removal of carbon dioxide and/or methane from water (8). The higher number of AOP in water sampled after tower aeration and pellet softening than in water from the first rapid sand filter at plant B implies that biological nitrification is limited in the first rapid sand filter. The raw water of plant B contains high concentrations of DOC, methane, iron, and manganese, which might limit nitrification during biological filtration (2, 9).

Most striking was the observation that AOB dominated the AOP fraction in the biological treatment processes in the treatment train of the middle-deep extracted groundwater at plant C, whereas AOA dominated these processes during treatment of the deep extracted groundwater. Correlation studies confirmed that each dominant AOP fraction was responsible for ammonia removal during the biological filtration processes in the respective treatment train. Moreover, the number of AOB was positively correlated with the DOC concentration in the water, whereas AOA numbers correlated negatively with DOC concentrations. These results indicate that a high DOC content in the water might limit the growth of AOA. Treatment plant B, which extracts groundwater with a high DOC concentration as well, also showed low AOA numbers in the treatment train, confirming the correlation results between DOC and AOA at plant C. However, it might be that the correlation between DOC and AOA or AOB numbers is spurious. For instance, not only is the DOC concentration higher in the middle-deep extracted groundwater at plant C and the groundwater extracted at plant B, but iron and manganese concentrations are considerably higher in these water types as well. Furthermore, AOA dominated AOB in soils with relatively low and high water-extractable carbon (15), which demonstrates that the correlation between AOB or AOA does not occur in all environments. Therefore, additional in vitro experiments have to be conducted to elucidate the role of DOC in the establishment of an AOP population in water treatment, but such a study goes beyond the scope of our paper.

Previous studies have shown that MPN counts of AOP increase toward the distal part of the distribution system (16, 17) due to an increased amount of ammonia in chloraminated drinking water (6). Because drinking water is distributed without a disinfection residual in The Netherlands, ammonia concentrations are below the detection limit in the distribution system and growth of AOP will be absent or very low. Indeed, we observed that the numbers of AOB and AOA did not increase along the distribution system of treatment plants B and C. In contrast, the number of AOA in water samples taken from the distal part of the distribution system of plant A was significantly higher than that in water samples taken at the proximal part of the distribution system. Furthermore, the cluster analysis of the AOA OTUs showed that AOA populations in the distribution system were different from AOA populations in the last treatment stages. These observations imply that certain AOA species grew in the distribution system. This was especially unexpected for plant A, because ammonia was not detected in the extracted raw water and the concentration of organic carbon in the finished water was very low, resulting in a high level of biological stability (25). It has not been extensively tested if the cultivated AOAs described thus far are able to grow on substrates other than ammonia (7, 11, 13). The cultivated AOA “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus maritimus” is related to marine group I crenarchaea (13), and other authors have suggested that some crenarchaeal species belonging to marine group I grow heterotrophically (1, 19). Perhaps some of the AOA species present in drinking water can grow on both organic carbon and ammonia, but activity studies have to be performed to prove this hypothesis.

No Nitrosospira amoA-like sequences were obtained in our study, demonstrating that the conditions during water treatment favor growth of Nitrosomonas species. The same Nitrosomonas phylotype dominated most water samples at plants B and C. Apparently, the geographic distance between the two water treatment plants (135 km) and the difference in raw water quality between the two plants did not influence the population structure of AOB, and the conditions at each water treatment plant resulted in the same dominant phylotype. Studies of AOB phylogenetics in distribution systems in the United States and Finland have found a low diversity of AOB as well (16, 21). The obtained dominant AOB genotypes belonged to the Nitrosomonas oligotropha cluster (United States) or the Nitrosomonas marina cluster (Finland) but not to the Nitrosomonas europaea cluster that harbored the dominant phylotype obtained in our study. However, in contrast to our study, the other studies used chloraminated drinking water, which is likely to select for AOB populations that are more resistant to chloramine.

Inactive nitrifying biomass that enters the distribution system might be degraded by heterotrophic bacteria, which could result in biofilm formation and growth of undesired microorganisms (e.g., Aeromonas or Legionella) (26). Although we showed that AOP biomass enters the distribution system, AOA and AOB numbers were not significantly lower at the distal part of the distribution system. The nitrification in the treatment train of plant B and C seems to be sufficient to prevent growth of nitrifying prokaryotes on ammonia in the distribution system. Moreover, the inactive nitrifying biomass entering the distribution system is not instantly removed by settling or consumption by protozoa.

AOA in drinking water.

Only recently it was demonstrated that AOA can be responsible for the oxidation of ammonia (13). Moreover, in several soil samples, AOA were numerically dominant over AOB (15), stressing their importance in some environments. The results from our study demonstrate that AOA can also be present in (drinking) water sampled from the treatment train and distribution system of water treatment plants in The Netherlands. The highest number of AOA was observed at water treatment plant A, and AOA dominated the ammonia-oxidizing population. However, the raw water of plant A has an ammonia concentration below the detection limit (<0.05 mg NH4 liter−1), and numbers of AOA remain stable during water treatment because nitrification does not occur in the treatment train. As a result, the AOA population in raw and finished water at plant A probably reflects the composition of the ammonia-oxidizing populations in the saturated sandy soil surrounding the extraction well. This explanation is supported by the following: (i) our observation that some of the amoA gene sequences of AOA clustered with sequences obtained from clone libraries of soil DNA and (ii) observations that the number of AOA in sandy soils can exceed the number of AOB by a factor of 1,200 (15). Treatment plant C contained approximately equal amounts of AOA and AOB, and numbers increased simultaneously during water treatment, suggesting that these organisms contribute equally to the biological nitrification of ammonia in the treatment trains. Overall, we conclude that AOA can be significant contributors to nitrification in drinking water treatment and can be present in the distribution system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the water supply companies in The Netherlands as part of the joint research program (BTO).

We thank Geo Bakker of Vitens Water Technology and Stephan van de Wetering of Brabant Water for their assistance in selecting and organizing sampling strategies at the three drinking water treatment plants.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 May 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agogue, H., M. Brink, J. Dinasquet, and G. J. Herndl. 2008. Major gradients in putatively nitrifying and non-nitrifying Archaea in the deep North Atlantic. Nature 456:788-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedard, C., and R. Knowles. 1989. Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of CH4, NH4+, and CO oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53:68-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belser, L. W., and E. L. Mays. 1982. Use of nitrifier activity measurements to estimate the efficiency of viable nitrifier counts in soils and sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:945-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouwer, E. J., and P. B. Crowe. 1988. Biological processes in drinking water treatment. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 80:82-93. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chain, P., J. Lamerdin, F. Larimer, W. Regala, V. Lao, M. Land, L. Hauser, A. Hooper, M. Klotz, J. Norton, L. Sayavedra-Soto, D. Arciero, N. Hommes, M. Whittaker, and D. Arp. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 185:2759-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunliffe, D. A. 1991. Bacterial nitrification in chloraminated water supplies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:3399-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Torre, J. R., C. B. Walker, A. E. Ingalls, M. Konneke, and D. A. Stahl. 2008. Cultivation of a thermophilic ammonia oxidizing archaeon synthesizing crenarchaeol. Environ. Microbiol. 10:810-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Moel, P. J., J. Q. J. C. Verberk, and J. C. van Dijk. 2006. Drinking water. Principles and practice. World Scientific, Hackensack, NJ.

- 9.de Vet, W. W. J. M., L. C. Rietveld, and M. C. M. van Loosdrecht. 2007. Influence of iron on nitrification in full-scale drinking water filters, p. 1.8-8.8. In A. Degrémont (ed.), Proceedings of the 2007 IWA International Conference on Particle Separation, Toulouse, France. IWA Publishing, London, United Kingdom.

- 10.Francis, C. A., K. J. Roberts, J. M. Beman, A. E. Santoro, and B. B. Oakley. 2005. Ubiquity and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in water columns and sediments of the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:14683-14688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatzenpichler, R., E. V. Lebedeva, E. Spieck, K. Stoecker, A. Richter, H. Daims, and M. Wagner. 2008. A moderately thermophilic ammonia-oxidizing crenarchaeote from a hot spring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:2134-2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoefel, D., P. T. Monis, W. L. Grooby, S. Andrews, and C. P. Saint. 2005. Culture-independent techniques for rapid detection of bacteria associated with loss of chloramine residual in a drinking water system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6479-6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konneke, M., A. E. Bernhard, J. R. de la Torre, C. B. Walker, J. B. Waterbury, and D. A. Stahl. 2005. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437:543-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent, P., A. Kihn, A. Andersson, and P. Servais. 2003. Impact of backwashing on nitrification in the biological activated carbon filters used in drinking water treatment. Environ. Technol. 24:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leininger, S., T. Urich, M. Schloter, L. Schwark, J. Qi, G. W. Nicol, J. I. Prosser, S. C. Schuster, and C. Schleper. 2006. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 442:806-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipponen, M. T., P. J. Martikainen, R. E. Vasara, K. Servomaa, O. Zacheus, and M. H. Kontro. 2004. Occurrence of nitrifiers and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in developing drinking water biofilms. Water Res. 38:4424-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipponen, M. T., M. H. Suutari, and P. J. Martikainen. 2002. Occurrence of nitrifying bacteria and nitrification in Finnish drinking water distribution systems. Water Res. 36:4319-4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mincer, T. J., M. J. Church, L. T. Taylor, C. Preston, D. M. Karl, and E. F. DeLong. 2007. Quantitative distribution of presumptive archaeal and bacterial nitrifiers in Monterey Bay and the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1162-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouverney, C. C., and J. A. Fuhrman. 2000. Marine planktonic archaea take up amino acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4829-4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park, H.-D., G. F. Wells, H. Bae, C. S. Criddle, and C. A. Francis. 2006. Occurrence of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in wastewater treatment plant bioreactors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5643-5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regan, J. M., G. W. Harrington, and D. R. Noguera. 2002. Ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacterial communities in a pilot-scale chloraminated drinking water distribution system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:73-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotthauwe, J. H., K. P. Witzel, and W. Liesack. 1997. The ammonia monooxygenase structural gene amoA as a functional marker: molecular fine-scale analysis of natural ammonia-oxidizing populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4704-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schloss, P. D., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treusch, A. H., S. Leininger, A. Kletzin, S. C. Schuster, H.-P. Klenk, and C. Schleper. 2005. Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1985-1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Kooij, D. 1992. Assimilable organic carbon as an indicator of bacterial regrowth. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 84:57-65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Kooij, D. 2003. Managing regrowth in drinking-water distribution systems, p. 199-232. In J. Bartram, C. Cotruvo, M. Exner, C. Fricker, and A. Glasmacher (ed.), Heterotrophic plate counts and drinking-water safety. IWA Publishing, London, United Kingdom.

- 27.van der Wielen, P. W., H. Bolhuis, S. Borin, D. Daffonchio, C. Corselli, L. Giuliano, G. D'Auria, G. J. de Lange, A. Huebner, S. P. Varnavas, J. Thomson, C. Tamburini, D. Marty, T. J. McGenity, and K. N. Timmis. 2005. The enigma of prokaryotic life in deep hypersaline anoxic basins. Science 307:121-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wert, E. C., J. J. Neemann, D. J. Rexing, and R. E. Zegers. 2008. Biofiltration for removal of BOM and residual ammonia following control of bromate formation. Water Res. 42:372-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilczak, A., J. G. Jacangelo, J. P. Marcinko, L. H. Odell, G. J. Kirmeyer, and R. L. Wolfe. 1996. Occurrence of nitrification in chloraminated distribution systems. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 80:74-85. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolda, H. 1981. Similarity indices, sample size and diversity. Oecologia (Berlin) 50:296-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.