Abstract

Partial atlE sequencing (atlE nucleotides 2782 to 3114 [atlE2782-3114]) was performed in 41 Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates from prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) and 44 isolates from skin as controls. The atlE2782-3114 allele 1 (type strain sequence) was significantly more frequent in PJI strains (38/41 versus 29/44 in controls; P = 0.0023). Most PJI strains were positive for mecA, icaA/icaD, and IS256, and most belonged to the sequence type 27 subgroup, suggesting the involvement of few related clones.

Prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) are a major public health issue worldwide, resulting in high rates of morbidity and massive economic burdens. In France, approximately 100,000 hip replacements and 50,000 knee replacements are performed each year (http://stats.atih.sante.fr), and about 1 to 2% of hip prostheses and 0.5% of knee prostheses get infected (25). Staphylococcus epidermidis is a leading causative agent in most series described in Western countries, with an estimate of 15 to 40% of PJIs involving this species (13).

The role of S. epidermidis in PJIs, and more generally in device-related infections, may be a consequence of its unique capacity to adhere to and to form biofilms at the surface of implanted medical devices (32). A number of bacterial factors have been implicated in this multistep process, including the autolysin/adhesin AtlE (10, 27), fibronectin-binding proteins (9), and the ica locus-encoded polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (14, 22, 27). Work based upon multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis has shown that human S. epidermidis infections involve few clones, mostly sequence type 27 (ST27) and related STs (12, 35, 37). These clones are characterized by multidrug resistance to antibiotics, notably oxacillin and gentamicin, and the presence of the insertion sequence IS256 and the ica operon in their genome (12, 37).

AtlE, encoded by the atlE gene, is a bifunctional autolysin with an N-terminal alanine amidase domain, a central cell wall-anchoring (CWA) domain, and a C-terminal glucosaminidase domain. Like other CWA domains of gram-positive autolysins able to mediate bacterial adhesion (15), the CWA domain of AtlE has adhesive properties and is probably involved in the interaction between staphylococcal cells and biomaterial (4, 10). We recently studied allelic polymorphism of the CWA domain of AtlE in collection S. epidermidis strains and showed a clear relationship between AtlE CWA alleles and STs (30). Here, we report the partial sequencing of atlE in PJI strains prospectively collected in two orthopedic reference centers over a 4-year period. The sequence results were correlated with the findings of MLST analysis and the presence of relevant pathogenicity and resistance markers.

The strains studied were identified by gram staining, catalase tests, slide agglutination tests, tube coagulase tests, and partial sodA sequence analysis, as previously described (24, 29). DNA was prepared from bacteria grown on sheep blood agar at 37°C for 18 h under aerobic conditions. Colonies were scraped from the plates and resuspended in sterile distilled water (McFarland standard no. 5). DNA was extracted by boiling or with the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen SA, Courtabœuf, France), as recently described (29). Amplification of the atlE segment from nucleotides (nt) 2731 to 3195 (GenBank accession no. U71377, region 2620 to 6627 coding sequence) was performed with primers F23 (5′-CGTACTCAAGGTAATAACAC-3′) and R23 (5′-TTGCTTAATGACTGTGAAAGT-3′) (30). Sequencing of the atlE segment from nt 2782 to 3114 (atlE2782-3114) was performed with the same primers. The mecA, icaA, and icaD genes and IS256 were detected by PCR as described previously (2, 8, 18). MLST was performed by determining partial nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping genes: arcC (carbamate kinase), aroE (shikimate 5-dehydrogenase), glpK (glycerol kinase), gmk (guanylate kinase), pta (phosphate acetyltransferase), tpiA (triosephosphate isomerase), and yqi (acetyl coenzyme A acetyltransferase) (35). Sequences were compared with the sequences of known alleles for each locus in the MLST database (http://www.mlst.net)—to which new alleles and STs were added—and the resulting seven-digit profiles, defining STs, were used to interrogate the database for matches. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4 (31). The most likely patterns of evolutionary relationships between our S. epidermidis isolates were evaluated by BURST analysis with START2 software (11). To identify groups of related STs, we used a stringent definition: all members assigned to the same group share identical alleles with at least one other member of the group at six of the seven MLST loci. All STs in a BURST group could then be assigned to a single clonal complex; STs with at least two assigned descendant single-locus variants were defined as subgroup founders. Fisher's exact test (K. J. Preacher and N. E. Briggs, software for calculation for Fisher's exact test for 2-by-2 tables, 2001) was used to compare values, and P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

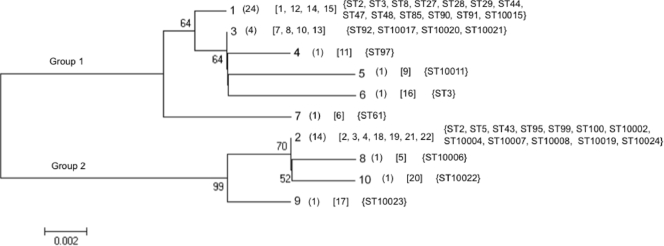

We recently determined the sequence of the entire CWA domain of the atlE gene (atlECWA; atlE1546-3045) in 27 clinical strains (PJIs; n = 5), 22 skin flora, and two reference strains (CIP 81.55T [ATCC 14990T] and CIP 105777 [ATCC 35984]). S. epidermidis strains, allowing the identification of 22 alleles (i.e., unique nucleotide sequences), were distributed into two main groups: group 1 and group 2 (30). In the present study, we chose to sequence, with only one pair of primers (instead of six primers for atlECWA), a shorter, polymorphic fragment, the atlE2782-3114 fragment, which encompasses the C-terminal half of the CWA R3 repeat and the N terminus of the glucosaminidase domain. With the same set of 49 strains described previously (30), atlE2782-3114 sequencing identified 10 alleles (GenBank accession no. FJ009419 to FJ009428), also distributed into two main groups: group 1 (alleles 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) and group 2 (alleles 2, 8, 9, and 10); as for atlECWA alleles (30), the atlE2782-3114 type strain sequence was arbitrarily designated allele 1. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the atlE2782-3114 alleles and the atlECWA alleles. Allele 1 of atlE2782-3114 was the most numerous allele in group 1 (24/32 [75%]), and allele 2 was the most numerous allele in group 2 (14/17 [82.4%]). As previously shown with atlECWA (30), there was a clear relationship between the atlE2782-3114 allele and ST: most notably, strains from ST27 (n = 5) and related clones (ST28 and ST10015) (n = 3) carried allele 1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Genetic relatedness between atlE2782-3114 alleles. The evolutionary relationships were inferred using the neighbor-joining method. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Nei-Gojobori method and are in units representing the number of synonymous differences per sequence. Tree branch lengths are drawn to scale. Numbers of strains are given in parentheses, atlECWA alleles are given in brackets (30), and STs are given in braces.

The atlE2782-3114 sequence was then determined in 41 PJI strains (39 subjects) and 44 skin controls (40 subjects). Five of the 41 PJI strains (28, 30) and 22 of the 44 skin controls (30) have been described in previous studies. PJI strains included all S. epidermidis strains recovered from cases of PJIs between January 1999 and December 2002 in two reference centers for the management of bone and joint infections: one in France (Orthopedic Department, Raymond Poincaré hospital, Garches) and one in Switzerland (Orthopedic Clinic, University Hospital of Geneva). Only cases involving S. epidermidis alone (monospecific PJIs) were included in the study. A PJI strain was defined as a strain recovered from ≥3 distinct preoperative samples, according to the recommendations of the OSIRIS (Oxford Skeletal Infection Research and Intervention Service) group (3). S. epidermidis isolates recovered from multiple samples in the same procedure were deemed the same strain if they had the same colonial morphology and an identical antibiotic susceptibility pattern (3). Skin controls comprised 22 strains from 20 healthy individuals, 11 strains isolated from 10 patients on hospital admission for aseptic orthopedic surgery, 6 strains from 6 hospitalized patients undergoing antimicrobial chemotherapy, and 5 strains from 4 surgeons.

A fragment of the expected size was amplified in all PJI and control strains studied by atlE primers F23 and R23, confirming the systematic presence of atlE in S. epidermidis (30). Of the 10 atlE2782-3114 alleles identified above (Fig. 1), only 6 were detected (alleles 1 to 6). Overall, allele 1 (group 1) and allele 2 (group 2) were by far the most prevalent (67/85 [79%] and 14/85 [16%], respectively). Allele 1 was significantly more prevalent among PJI strains than among controls (38/41 [92.7%] versus 29/44 [65.9%]; P = 0.0023) (Table 1). The markers mecA, ica, and IS256 were also significantly more prevalent among PJI strains than skin controls (respective P values of <10−6, <10−3, and <10−4) (Table 1). These results were consistent with MLST analysis (Tables 1 and 2): a majority of PJI strains belonged to an ST27-related subgroup of STs within the major clonal complex (22/41 [53.7%] versus 4/44 [9.1%] skin controls; P < 10−5). Overall, strains belonging to ST27 or related STs (n = 26) were more likely than other strains (n = 59) to express the following markers: atlE2782-3114 allele 1 (100 versus 69%; P = 0.00053), mecA (96 versus 42%; P < 10−6), ica (96 versus 22%; P < 10−8), and IS256 (88 versus 8%; P < 10−8).

TABLE 1.

Comparative characteristics of PJI and control strains

| Characteristic | No. (%) of positive strains

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PJI strains (n = 41) | Skin flora (n = 44) | ||

| atlE2782-3114 allele 1 | 38 (92.7) | 29 (65.9) | 0.0023 |

| mecA | 36 (87.8) | 14 (31.8) | <10−6 |

| ica | 27 (65.9) | 11 (25) | <10−3 |

| IS256 | 22 (53.7) | 6 (13.6) | <10−4 |

| ST27 subgroupa | 22 (53.7) | 4 (9.1) | <10−5 |

ST27, ST28, ST38, ST96, and ST10015 (as shown by BURST analysis of all S. epidermidis strains, this study).

TABLE 2.

atlE2782-3114 alleles and STs among PJI strains and skin controls

| atlE2782-3114 allele no. (n) | ST (no. of strains)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PJI strains (n = 41) | Skin controls (n = 44) | |

| 1 (67) | ST27a (13), ST29 (5), ST28a (4), ST2 (3), ST43 (3), ST18 (2), ST38a (2), ST96a (2), ST3 (1), ST87 (1), ST94 (1), ST10015a (1) | ST2 (5), ST27a (4), ST44 (4), ST3 (2), ST8 (1), ST18 (1), ST29 (1), ST43 (1), ST47 (1), ST48 (1), ST84 (1), ST85 (1), ST86 (1), ST88 (1), ST89 (1), ST90 (1), ST91 (1), ST93 (1) |

| 2 (14) | ST99 (1), ST10002 (1), ST10003 (1) | ST43 (2), ST8 (1), ST95 (1), ST100 (1), ST10001 (1), ST10004 (1), ST10009 (1), ST10010 (1), ST10012 (1), ST10014 (1) |

| 3 (1) | ST92 | |

| 4 (1) | ST97 | |

| 5 (1) | ST10011 | |

| 6 (1) | ST3 | |

ST27 subgroup (see footnote a in Table 1).

Several recent studies illustrate the growing contribution of ST27 and related clones to human disease (12, 35). These clones display several factors essential for the pathogenic potential of S. epidermidis (e.g., ica): its genetic flexibility (e.g., IS256) and its resistance to antibiotics (e.g., mecA, gentamicin resistance) (12, 37). These factors seem to have been progressively selected over the last few decades. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the involvement of these clones in PJIs: over 50% of our strains isolated from PJIs belonged to ST27 or related clones. This value is similar to findings for other types of infection (12, 16, 35). Our findings are also consistent with previous studies reporting that many PJI strains are ica positive, IS256 positive, and oxacillin resistant (7, 17, 26, 36). The high prevalence of mecA among our S. epidermidis strains (more than 85%) is significant: it leads to glycopeptides being increasingly frequently used for treatment, and as multiresistant clones are already circulating, there is a risk of selection of strains with decreased susceptibility to glycopeptides, as has been described for other types of infection (1).

Partial sequencing of atlE confirm the existence of two major lineages among S. epidermidis strains (30), as previously found by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of isolates from Brazil (21), Italy (5), Sweden (23), and France (20). During preliminary comparisons of PJI and control strains, we felt that allele 1 (i.e., the type strain sequence) was a potential marker of infectious strains. However, although almost all our PJI strains carry allele 1, it is also present in almost two-thirds of the control strains. Consequently, allele 1 cannot be used as a marker of infectious strains as it is present in a large proportion of strains constituting the skin flora (and therefore has a low positive predictive value). Nevertheless, its absence may serve as a sign of noninfection (high negative predictive value). It is also possible that the level of expression of AtlE, rather than the allele, is important, and consequently, its expression could be used as a marker. Indeed, about one-third of PJI strains may have a nonfunctional agr system (34), which may result in increasing AtlE expression (33). A study to investigate this issue would therefore be useful. The most discriminating marker among those we tested was mecA. Like others (6, 19, 26), we did not detect ica in about one-third of PJI strains, precluding its use as a practical pathogenicity marker and suggesting that other factors (for example, Aap) may play an important role in biofilm production and pathogenesis (26). Further prospective investigations will be required to assess the value of these markers, alone or in combination.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Chaverot and V. Avettand for technical assistance and Jonathan Thomas (Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, St. Mary's Hospital Campus, Imperial College London, United Kingdom) for help with MLST.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., A. Widmer, and R. Frei. 2003. Emergence of a teicoplanin-resistant small colony variant of Staphylococcus epidermidis during vancomycin therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22746-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arciola, C. R., S. Collamati, E. Donati, and L. Montanaro. 2001. A rapid PCR method for the detection of slime-producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. aureus in periprosthesis infections. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 10130-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins, B. L., N. Athanasou, J. J. Deeks, D. W. M. Crook, H. Simpson, T. E. A. Peto, P. McLardy-Smith, A. R. Berendt, and the OSIRIS Collaborative Study Group. 1998. Prospective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic-joint infection at revision arthroplasty. J. Clin. Microbiol. 362932-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas, R., L. Voggu, U. K. Simon, P. Hentschel, G. Thumm, and F. Gotz. 2006. Activity of the major staphylococcal autolysin Atl. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 259260-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cafiso, V., T. Bertuccio, M. Santagati, F. Campanile, G. Amicosante, M. G. Perilli, L. Selan, M. Artini, G. Nicoletti, and S. Stefani. 2004. Presence of the ica operon in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis and its role in biofilm production. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 101081-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank, K. L., A. D. Hanssen, and R. Patel. 2004. icaA is not a useful diagnostic marker for prosthetic joint infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 424846-4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galdbart, J. O., J. Allignet, H. S. Tung, C. Ryden, and N. El Solh. 2000. Screening for Staphylococcus epidermidis markers discriminating between skin-flora strains and those responsible for infections of joint prostheses. J. Infect. Dis. 182351-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu, J., H. Li, M. Li, C. Vuong, M. Otto, Y. Wen, and Q. Gao. 2005. Bacterial insertion sequence IS256 as a potential molecular marker to discriminate invasive strains from commensal strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Hosp. Infect. 61342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo, B., X. Zhao, Y. Shi, D. Zhu, and Y. Zhang. 2007. Pathogenic implication of a fibrinogen-binding protein of Staphylococcus epidermidis in a rat model of intravascular-catheter-associated infection. Infect. Immun. 752991-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heilmann, C., M. Hussain, G. Peters, and F. Gotz. 1997. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 241013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jolley, K. A., E. J. Feil, M. S. Chan, and M. C. Maiden. 2001. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START). Bioinformatics 171230-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozitskaya, S., M. E. Olson, P. D. Fey, W. Witte, K. Ohlsen, and W. Ziebuhr. 2005. Clonal analysis of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates carrying or lacking biofilm-mediating genes by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 434751-4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentino, J. R. 2003. Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clin. Infect. Dis. 361157-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, H., L. Xu, J. Wang, Y. Wen, C. Vuong, M. Otto, and Q. Gao. 2005. Conversion of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from commensal to invasive by expression of the ica locus encoding production of biofilm exopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 733188-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milohanic, E., R. Jonquieres, P. Cossart, P. Berche, and J. L. Gaillard. 2001. The autolysin Ami contributes to the adhesion of Listeria monocytogenes to eukaryotic cells via its cell wall anchor. Mol. Microbiol. 391212-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miragaia, M., J. C. Thomas, I. Couto, M. C. Enright, and H. de Lencastre. 2007. Inferring a population structure for Staphylococcus epidermidis from multilocus sequence typing data. J. Bacteriol. 1892540-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montanaro, L., D. Campoccia, V. Pirini, S. Ravaioli, M. Otto, and C. R. Arciola. 2007. Antibiotic multiresistance strictly associated with IS256 and ica genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from implant orthopedic infections. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 83813-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami, K., W. Minamide, K. Wada, E. Nakamura, H. Teraoka, and S. Watanabe. 1991. Identification of methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 292240-2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsdotter-Augustinsson, A., A. Koskela, L. Ohman, and B. Soderquist. 2007. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from patients with infected hip prostheses: use of phenotypic and genotypic analyses, including tests for the presence of the ica operon. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 26255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ninin, E., N. Caroff, E. Espaze, J. Maraillac, D. Lepelletier, N. Milpied, and H. Richet. 2006. Assessment of ica operon carriage and biofilm production in Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates causing bacteraemia in bone marrow transplant recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12446-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunes, A. P., L. M. Teixeira, C. C. Bastos, M. G. Silva, R. B. Ferreira, L. S. Fonseca, and K. R. Santos. 2005. Genomic characterization of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolated from Brazilian medical centres. J. Hosp. Infect. 5919-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson, M. E., K. L. Garvin, P. D. Fey, and M. E. Rupp. 2006. Adherence of Staphylococcus epidermidis to biomaterials is augmented by PIA. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 45121-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persson, L., H. Strid, U. Tidefelt, and B. Soderquist. 2006. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated in blood cultures from patients with haematological malignancies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, C. Boumaila, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 2001. Rapid and accurate species-level identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci by using the sodA gene as a target. J. Clin. Microbiol. 394296-4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.RAISIN. 2007. Réseau d'alerte, d'investigation et de surveillance des infections nosocomiales (Raisin). Surveillance des infections du site opératoire en France de 1999 à 2005—Réseau ISO—Résultats. Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France.

- 26.Rohde, H., E. C. Burandt, N. Siemssen, L. Frommelt, C. Burdelski, S. Wurster, S. Scherpe, A. P. Davies, L. G. Harris, M. A. Horstkotte, J. K. Knobloch, C. Ragunath, J. B. Kaplan, and D. Mack. 2007. Polysaccharide intercellular adhesin or protein factors in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from prosthetic hip and knee joint infections. Biomaterials 281711-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rupp, M. E., P. D. Fey, C. Heilmann, and F. Gotz. 2001. Characterization of the importance of Staphylococcus epidermidis autolysin and polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in the pathogenesis of intravascular catheter-associated infection in a rat model. J. Infect. Dis. 1831038-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sivadon, V., M. Rottman, S. Chaverot, J.-C. Quincampoix, V. Avettand, P. de Mazancourt, L. Bernard, P. Trieu-Cuot, J.-M. Feron, A. Lortat-Jacob, P. Piriou, T. Judet, and J.-L. Gaillard. 2005. Use of genotypic identification by sodA sequencing in a prospective study to examine the distribution of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species among strains recovered during septic orthopedic surgery and evaluate their significance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 432952-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sivadon, V., M. Rottman, J. C. Quincampoix, V. Avettand, S. Chaverot, P. de Mazancourt, P. Trieu-Cuot, and J. L. Gaillard. 2004. Use of sodA sequencing for the identification of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10939-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivadon, V., M. Rottman, J.-C. Quincampoix, E. Prunier, P. de Mazancourt, L. Bernard, A. Lortat-Jacob, P. Piriou, T. Judet, and J. L. Gaillard. 2006. Polymorphism of the cell wall-anchoring domain of the autolysin-adhesin AtlE and its relationship to sequence type, as revealed by multilocus sequence typing of invasive and commensal Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441839-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura, K., J. Dudley, M. Nei, and S. Kumar. 2007. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 241596-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Eiff, C., G. Peters, and C. Heilmann. 2002. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vuong, C., C. Gerke, G. A. Somerville, E. R. Fischer, and M. Otto. 2003. Quorum-sensing control of biofilm factors in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Infect. Dis. 188706-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vuong, C., S. Kocianova, Y. Yao, A. B. Carmody, and M. Otto. 2004. Increased colonization of indwelling medical devices by quorum-sensing mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 1901498-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wisplinghoff, H., A. E. Rosato, M. C. Enright, M. Noto, W. Craig, and G. L. Archer. 2003. Related clones containing SCCmec type IV predominate among clinically significant Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 473574-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao, Y., D. E. Sturdevant, A. Villaruz, L. Xu, Q. Gao, and M. Otto. 2005. Factors characterizing Staphylococcus epidermidis invasiveness determined by comparative genomics. Infect. Immun. 731856-1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziebuhr, W., S. Hennig, M. Eckart, H. Kranzler, C. Batzilla, and S. Kozitskaya. 2006. Nosocomial infections by Staphylococcus epidermidis: how a commensal bacterium turns into a pathogen. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 28(Suppl. 1)S14-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]