Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA genotyping is an essential test to establish efficacy in HPV vaccine clinical trials and HPV prevalence in natural history studies. A number of HPV DNA genotyping methods have been cited in the literature, but the comparability of the outcomes from the different methods has not been well characterized. Clinically, cytology is used to establish possible HPV infection. We evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of HPV multiplex PCR assays compared to those of the testing scheme of the Hybrid Capture II (HCII) assay followed by an HPV PCR/line hybridization assay (HCII-LiPA v2). SurePath residual samples were split into two aliquots. One aliquot was subjected to HCII testing followed by DNA extraction and LiPA v2 genotyping. The second aliquot was shipped to a second laboratory, where DNA was extracted and HPV multiplex PCR testing was performed. Comparisons were evaluated for 15 HPV types common in both assays. A slightly higher proportion of samples tested positive by the HPV multiplex PCR than by the HCII-LiPA v2 assay. The sensitivities of the multiplex PCR assay relative to those of the HCII-LiPA v2 assay for HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18, for example, were 0.806, 0.646, 0.920, and 0.860, respectively; the specificities were 0.986, 0.998, 0.960, and 0.986, respectively. The overall comparability of detection of the 15 HPV types was quite high. Analyses of DNA genotype testing compared to cytology results demonstrated a significant discordance between cytology-negative (normal) and HPV DNA-positive results. This demonstrates the challenges of cytological diagnosis and the possibility that a significant number of HPV-infected cells may appear cytologically normal.

Cervical cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death among women globally. An estimated 510,000 new cases will be diagnosed around the world this year, and 288,000 women will die from the disease (15). In developing countries, cervical cancer can be the most common cancer among women. There is a strong causal relationship between infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer, as the prevalence of the virus in cervical cancers has been estimated to be as high as 99.7% (14).

Reliable, sensitive, and accurate detection of specific HPV types is critical for the study of cervical cancer causation as well as the support of vaccine clinical trials. Several PCR-based methodologies have been developed to amplify and detect HPV DNA (1, 4, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13). Many of these methodologies exploit the high homology found within specific open reading frames (ORFs) across different HPV types through the use of consensus or degenerate primer pairs that are capable of PCR amplifying numerous HPV types present in a sample. The resultant amplicons are detected and genotyped by utilizing HPV type-specific probes and colorimetric precipitation. While a greater number of HPV types can be detected by these methodologies, additional experimentation beyond PCR cycling is required to identify specific HPV types. Concerns arise over the increased contamination risk with postamplification experimentation and equivalent optimization between HPV types using single-amplification and single-hybridization conditions.

For efficacy determinations of the recently FDA-approved quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) L1 VLP vaccine (Gardasil; Merck & Co., Inc.) (2, 3), highly sensitive and specific HPV multiplex PCR assays were developed (5, 10, 11) and used, which simultaneously detect the L1 and/or E6 and E7 ORFs of a specific HPV type using the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). In this system, DNA is purified from multiple anogenital swab samples per patient by utilizing spin column chemistry under very stringent conditions. All samples are then screened for HPV DNA using real-time HPV multiplex PCR assays. Studies of the direct comparability of HPV multiplex PCR assays and other HPV genotyping methods will begin to clarify the HPV prevalence inconsistencies reported in the literature, teasing out potential assay testing differences from true geographical prevalence differences. In addition, comparisons between HPV genotyping and the cytological diagnosis of a sample will begin to provide insight into the limitations of the various tests.

Herein we compare real-time HPV multiplex PCR assays to a method which involves a two-step process of initial screening with the Hybrid Capture II (HCII; Digene Corp., Gaithersburg, MD) assay followed by genotyping of HCII-positive samples using the INNO-LiPA v2 assay, an HPV PCR line hybridization assay (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium). Cross-tabulation analysis was performed between the HPV multiplex PCR assay high-risk HPV composite and the HCII-LiPA v2 high-risk HPV composite by SurePath cytology diagnosis. A post hoc analysis was also performed to evaluate the comparability of the HPV multiplex PCR assay to the INNO-LiPA v2 assay directly.

(Data presented herein were presented in part at the 23rd Annual International Papillomavirus Conference and Clinical Workshop, Prague, Czech Republic, 1 to 7 September 2006.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

In the context of a population-based study of the prevalence of HPV infection, cervical cytology specimens were obtained from approximately 11,000 females aged 15 to 64 years living in the greater Copenhagen region in Denmark (6). Samples gathered using the SurePath liquid-based cytology system (TriPath Imaging Inc., Burlington, NC) were stored at room temperature and shipped to the Department of Pathology at the Copenhagen University Hospital in Hvidovre within 1 to 2 days of sample collection. After slide preparation and diagnosis, the remaining material was sent to the Institute of Medical Virology at the University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

Specimen processing and HCII testing.

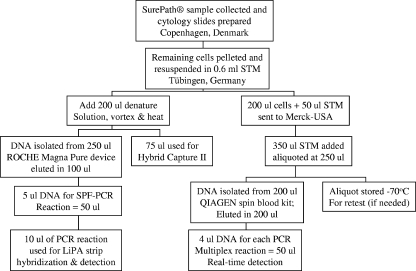

Cells in liquid-based cytology medium were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.6 ml sample transport medium (STM; Digene Corp., Gaithersburg, MD) (Fig. 1). Subsequently, 200 μl was transferred into a separate tube prefilled with 50 μl STM, and the cells were stored at −20°C for multiplex PCR testing. Denaturation reagent (0.5 volumes of the total volume remaining) was added to the remaining sample and heated for 45 min at 65°C. A 75-μl aliquot of the sample was used for HCII (Digene Corp., Gaithersburg, MD) testing using the HPV high-risk probe and the HPV low-risk probe cocktail with the help of the Rapid Capture system in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Additional controls run on each 96-well plate included 105 HPV-negative C33A cells and 105 HPV type 16 (HPV16)-positive SiHa cells (∼1 to 2 HPV16 copies/cell). The samples were sorted into the following groups based on the HCII result: group 1 consisted of HCII-positive samples with a relative light unit (RLU) value of ≥1.0, group 2 consisted of borderline positive samples with RLU values of >0.5 and <1.0, and group 3 consisted of ∼1,500 to 1,600 HCII-negative samples (randomly selected).

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of sample processing for PCR assays.

HPV genotyping by the INNO-LiPA v2 HPV prototype research assay.

DNA extraction processes and all pre- and post-PCR procedures were carried out in separate rooms and cabinets. Buffer and blank controls were always included for the extraction protocol to obtain sufficient numbers of negative controls in order to monitor contamination. The sample set was composed of HCII-defined groups 1, 2, and 3 as described above. DNA was purified from 250 μl of the denatured samples remaining after HCII testing by using the MagNA Pure compact nucleic acid purification system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) at the Institute of Medical Virology of the University Hospital of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. Purified DNA was eluted in 100 μl of buffer in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. The efficiency of DNA extraction was tested by the inclusion of 104 HPV16-positive SiHa cells followed by LiPA v2 testing.

The INNO-LiPA v2 HPV prototype research assay is a PCR-based line hybridization assay that utilizes a cocktail of biotinylated consensus primers (SPF10) to amplify a portion of the L1 ORF of HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 34, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 70, and 74 (7). Five microliters of DNA solution was used for the LiPA v2 SPF PCR assay in a final volume of 50 μl using AmpliTaq Gold and 40 cycles (30 s of denaturation at 95°C followed by 45 s of annealing at 52°C and a 45-s extension step at 72°C). The PCR product was then denatured, and a 10-μl aliquot was hybridized onto nitrocellulose strips onto which HPV type-specific oligonucleotides were already bound. After 60 min at 49°C, the PCR product bound to a specific probe was detected by an alkaline phosphatase-streptavidin conjugate and colorimetric detection. The reading of the hybridized strips was performed using a scanner and LiRAS prototype software (Innogenetics Inc., Ghent, Belgium). The software reports the band intensities in grey tone values of 0.1 to 1.0 and allows direct data transfer to Microsoft Excel spreadsheets.

HPV genotyping by HPV type-specific multiplex PCR assays.

The 250-μl samples stored at −20°C for HPV multiplex PCR testing assigned to groups 1 to 3 were sent to the Merck (West Point, PA) HPV PCR laboratory. In order to perform a head-to-head comparison of the two assay systems, efforts were made to standardize (on a cellular basis) the quantity of the starting material. Based on the HCII and Magna-Pure protocols, the University of Tübingen laboratory utilized less material than that used in the standard testing algorithm for HPV multiplex PCR testing in the quadrivalent HPV vaccine clinical trial program. In order to approximate the quantity of material used in the genotyping portion of HCII-LiPA v2 testing, samples sent to Merck Research Laboratories were diluted threefold in STM. After dilution, each sample was divided into two aliquots. The second aliquot provided a pristine aliquot with which to retest if necessary. Sample retests were always conducted using a fresh aliquot to eliminate the possibility that the sample was contaminated during initial DNA purification. DNA was purified from 200 μl of one aliquot using the DNA 96 blood kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) in a 96-well format in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. Each 96-well purification batch contained 14 buffer (STM) negative controls and eight human (MRC5 cells) and two HPV16 DNA purification positive controls (SiHa cells). Each purified DNA specimen was eluted in 200 μl.

For HPV type-specific multiplex PCR assays, primers and dual-labeled oligonucleotide probes were designed to specifically amplify and detect the L1, E6, and E7 ORFs of HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 45, 52, and 58 (5, 10) and the E6 and E7 ORFs of HPV types 33, 35, 39, 51, 56, 59, and 68 (11). The specificity and uniqueness of each primer and probe sequence were confirmed by BLAST searching of each sequence through the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and testing against type- and ORF-specific plasmids. The oligonucleotide fluorescent probes for the L1 loci were 5′ labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein, the oligonucleotide fluorescent probes for the E6 loci were 5′ labeled with 6-carboxy-4′,5′-dichloro-2′,7′-dimethoxyfluorescein, and the oligonucleotide fluorescent probes for the E7 loci were 5′ labeled with 5-tetrachloro-fluorescein. For those types tested in the two ORF multiplex assays, the E6 locus probes were 5-tetrachloro-fluorescein labeled, and the E7 locus probes were 6-carboxyfluorescein labeled. The primer-probe sets for each HPV type were optimized in a two-step process: first, each ORF primer-probe set was optimized individually and then modified and optimized, when necessary, in the multiplex reaction. Specimen sampling, HPV type variants, and viral integration can all potentially influence the amplification potential of a given ORF. Thus, as more than one ORF was amplified per HPV type, a stringent criterion was established to ensure consistent, accurate consensus HPV multiplex result recording. The driving rule is “twice positive,” demonstrating reproducible type-specific, ORF-specific detection. Twice positive was demonstrated by at least two ORF amplifications of a given HPV type in a single assay run.

The PCR mixture (50 μl) consisted of 4 μl sample DNA (regardless of DNA concentration), QuantiTect PCR master mix (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA), uracil-DNA-glycosylase (0.5 U/reaction; Invitrogen), each fluorescent oligonucleotide probe, and the HPV type- and ORF-specific primers. The development process for the selection of the primer-probe sequences, assay optimization conditions, and performance within a 10 to 106 dynamic range are detailed in the patent publications for the assays (5, 10, 11). After thermal cycling and data collection, preestablished thresholds were set, and the data were exported to a Microsoft Excel workbook for analysis.

Statistical analysis.

The agreement rate, McNemar P value (a measure of the imbalance in the distribution of discordant pairs), and kappa (a quantitative measure of agreement between the two assay methods with respect to sample classification) were calculated. The sensitivity of the HPV multiplex PCR assay relative to that of the HCII-LiPA v2 method is the proportion of multiplex PCR-positive samples among those which are HCII-LiPA v2 positive, and the specificity of the HPV multiplex PCR relative to that of the HCII-LiPA v2 method is the proportion of multiplex PCR-negative samples, among which are HCII-LiPA v2-negative samples. The predictive value of a positive HPV multiplex PCR result is the proportion of HCII-LiPA v2-positive samples, among which are multiplex PCR-positive samples, and the predictive value of a negative HPV multiplex PCR result is the proportion of the HCII-LiPA v2-negative samples, among which are multiplex PCR-negative samples. Similar analyses were performed post hoc by grouping all the data regardless of HCII status group and comparing HPV multiplex PCR versus INNO-LiPA v2 assay.

RESULTS

Cross-tabulation between the HPV multiplex PCR assay and the HCII-LiPA v2 assay.

The common practice of HCII screening followed by type-specific genotyping of the HCII-positive samples utilizes an HCII RLU value of ≥1.0 as the criterion for an HCII-positive sample. Samples that have an RLU value of <1.0 are not typically genotyped and are considered to be HPV negative. In keeping with this practice, individual samples that had a low-risk HCII RLU value of <1.0 were assigned a negative LiPA v2 outcome for HPV types 6 and 11, and individual samples that had a high-risk HCII RLU value of <1.0 were assigned a negative LiPA v2 outcome for HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68. For HPV multiplex assays, a prescreening assay such as HCII was not used, and all samples were tested using HPV multiplex PCR assays. The resulting cross-tabulations based on these testing algorithms are provided in Table 1. The overall agreement between the two assay testing schemes was 95% or greater for each HPV type. For HPV types 6, 16, 18, 33, 35, 39 56, 58, and 59, a slightly higher proportion of samples tested positive by the multiplex PCR than by the HCII-LiPA v2 assay. For HPV types 6, 16, 33, 56, 58, and 59, there was evidence of an imbalance in the distribution of discordant pairs, as there were significantly more samples testing HPV multiplex PCR positive/HCII-LiPA v2 PCR negative than HPV multiplex PCR negative/HCII-LiPA v2 PCR positive. For HPV51 and HPV68, there was evidence of a statistical imbalance in the discordant pairs, with significantly more samples testing HPV multiplex PCR negative/HCII-LiPA v2 positive than the reverse. For those types in which the imbalance did not attain statistical significance, there is a suggestion of greater comparability between the assays (i.e., HPV types 18, 31, 35, 39, 45, and 52). For HPV11, there was no statistical evidence of an imbalance in the distribution of the discordant samples, although the sensitivity of the comparison was diminished due to the small percentage of samples testing positive within each method (0.7% by multiplex PCR and 0.9% by HCII-LiPA v2 assay).

TABLE 1.

Cross-tabulation of multiplex PCR versus the HCII assay followed by the INNO-LiPA v2 assay

| HPV type | No. of samples tested | No. of samples with multiplex PCR/HCII-LiPA v2 result of:

|

Agreement (%) | McNemar P valueg | Kappa (95% CI)a | Sensitivityb | Specificityc | Predictive value of positive resulte | Predictive value of negative resultf | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/− | −/+ | |||||||||

| 6 | 5,225 | 162 | 4,956 | 68 | 39 | 98.0 | 0.0065 | 0.74 (0.69, 0.79) | 0.806 | 0.986 | 0.704 | 0.992 |

| 11 | 5,226 | 31 | 5,170 | 8 | 17 | 99.5 | 0.1078 | 0.71 (0.60, 0.82) | 0.646d | 0.998 | 0.795 | 0.997 |

| 16 | 5,182 | 631 | 4,317 | 179 | 55 | 95.5 | <0.0001 | 0.82 (0.79, 0.84) | 0.920 | 0.960 | 0.779 | 0.987 |

| 18 | 4,679 | 259 | 4,317 | 61 | 42 | 97.8 | 0.0756 | 0.82 (0.79, 0.86) | 0.860 | 0.986 | 0.809 | 0.990 |

| 31 | 5,224 | 412 | 4,597 | 101 | 114 | 95.9 | 0.4132 | 0.77 (0.74, 0.80) | 0.783 | 0.979 | 0.803 | 0.976 |

| 33 | 5,220 | 220 | 4,919 | 52 | 29 | 98.4 | 0.014 | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87) | 0.884 | 0.99 | 0.809 | 0.994 |

| 35 | 5,224 | 90 | 5,090 | 24 | 20 | 99.2 | 0.6516 | 0.80 (0.74, 0.86) | 0.818 | 0.995 | 0.789 | 0.996 |

| 39 | 5,217 | 234 | 4,856 | 71 | 56 | 97.6 | 0.214 | 0.77 (0.74, 0.81) | 0.807 | 0.986 | 0.767 | 0.989 |

| 45 | 5,224 | 156 | 4,914 | 74 | 80 | 97.1 | 0.6871 | 0.65 (0.60, 0.71) | 0.661 | 0.985 | 0.678 | 0.984 |

| 51 | 5,214 | 363 | 4,671 | 68 | 112 | 96.5 | 0.0013 | 0.78 (0.75, 0.81) | 0.764 | 0.986 | 0.842 | 0.977 |

| 52 | 5,222 | 383 | 4,634 | 93 | 112 | 96.1 | 0.2086 | 0.77 (0.74, 0.80) | 0.774 | 0.98 | 0.805 | 0.976 |

| 56 | 5,169 | 202 | 4,836 | 101 | 30 | 97.5 | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.70, 0.78) | 0.871 | 0.98 | 0.667 | 0.994 |

| 58 | 5,224 | 139 | 4,966 | 112 | 7 | 97.7 | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.64, 0.74) | 0.952 | 0.978 | 0.554 | 0.999 |

| 59 | 5,224 | 117 | 4,977 | 117 | 13 | 97.5 | <0.0001 | 0.63 (0.57, 0.69) | 0.9 | 0.977 | 0.5 | 0.997 |

| 68 | 5,098 | 97 | 4,839 | 39 | 123 | 96.8 | <0.0001 | 0.53 (0.47, 0.59) | 0.441 | 0.992 | 0.713 | 0.975 |

CI, confidence interval.

The proportion of multiplex PCR-positive samples, among which are HCII-LiPA v2-positive samples.

The proportion of multiplex PCR-negative samples, among which are HCII-LiPA v2-negative samples.

The number of samples that were PCR positive for HPV11 was small (∼1%).

The proportion of HCII-LiPA v2-positive samples, among which are multiplex PCR-positive samples.

The proportion of HCII-LiPA v2-negative samples, among which are multiplex PCR-negative samples.

Values in boldface type indicate significance.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value (as defined above) were determined to compare the HPV multiplex PCR and HCII-LiPA v2 assay procedures (Table 1). Overall, the sample set was largely HPV PCR negative for specific HPV types, lending greater power to the negative predictive value calculations than could be achieved from the data set for the positive predictive value. The proportion of HCII-LiPA v2-negative samples, among which were multiplex PCR-negative samples, was ≥0.975 for all types. The proportion of HCII-LiPA v2-positive samples, among which were multiplex PCR-positive samples, ranged from 0.5 to 0.842, suggesting greater comparability between the two assay testing schemes in discerning negative samples than in discerning positive samples.

Cross-tabulation between the HPV multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the HCII-LiPA v2 high-risk composite by SurePath diagnosis.

In order to compare the assay systems with regard to overall performance, each sample was assigned a composite high-risk result. The composites were composed of results for HPV high-risk types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68. Cross-tabulations between the HPV multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the HCII-LiPA v2 high-risk composite are provided by SurePath diagnosis in Table 2. Overall, there was reasonably good agreement between the HCII-LiPA v2 and the multiplex PCR assays with each of the SurePath diagnosis categories (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASCUS], squamous intraepithelial lesions of low grade 1 [LSIL-1] or LSIL-2, or squamous intraepithelial lesions of high grade [HSIL]). Agreement rates were 87.1%, 85.4%, 91.5%, and 94.6% for diagnoses of normal, ASCUS/LSIL-1, ASCUS/LSIL-2, and HSIL, respectively. For cytology samples diagnosed as being normal, there was evidence of a statistical imbalance in the number of discordant samples, with more samples testing multiplex PCR positive/HCII-LiPA v2 PCR negative than multiplex PCR negative/HCII-LiPA v2 PCR positive. Additionally, 53.5% of samples that were diagnosed as being normal were HPV PCR positive by one or both assays. For diagnoses of ASCUS/LSIL-1, ASCUS/LSIL-2, and HSIL, there was no statistical evidence of an imbalance in the numbers of discordant samples between the HCII-LiPA v2 and the multiplex PCR assays, although the sensitivity of these comparisons was reduced, as there were far fewer samples receiving these diagnoses than having a diagnosis of normal.

TABLE 2.

Cross-tabulation between the multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the HCII-LiPA v2 high-risk composite by SurePath diagnosis

| SurePath diagnosis and HCII-LiPA v2 test result | Multiplex PCR result

|

Agreement (%) | McNemar P value | Kappa (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Normala | 87.1 | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.72-0.76) | ||

| Positive | 1,870 | 247 | |||

| Negative | 350 | 2,146 | |||

| ASCUS/LSIL-1b | 85.4 | 0.4531 | 0.45 (0.11-0.79) | ||

| Positive | 37 | 2 | |||

| Negative | 5 | 4 | |||

| LSIL-2c | 91.5 | 0.7283 | 0.64 (0.53-0.73) | ||

| Positive | 316 | 18 | |||

| Negative | 15 | 37 | |||

| HSIL | 94.6 | 0.5078 | 0.64 (0.42-0.68) | ||

| Positive | 158 | 6 | |||

| Negative | 3 | 9 | |||

CI, confidence interval.

Diagnoses included koilocytotic atypia, flat condyloma, and condyloma.

Diagnoses included atypical cells and mild dysplasia.

Post hoc analysis: cross-tabulation of HPV multiplex PCR versus INNO-LiPA v2 assays.

Specimens belonging to groups 1 to 3 (group 1, HCII-positive samples with an RLU value of ≥1.0; group 2, borderline positive samples with RLU values of >0.5 and <1.0; and group 3, ∼1,500 to 1,600 HCII-negative samples) were evaluated by the INNO-LiPA v2 PCR assay and by HPV multiplex PCR assays. Results were analyzed regardless of group and/or HCII screening results (Table 3). While there was generally good agreement between the two PCR-based assays, as reflected by a kappa coefficient of >0.5 for all types except HPV11 and HPV68, there was evidence of a statistical imbalance in the number of discordant samples, with more samples that were determined to be multiplex PCR negative/INNO-LiPA v2 PCR positive than multiplex PCR positive/INNO-LiPA v2 negative for HPV types 6, 11, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, and 68. Additionally, a similar statistically significant but reverse imbalance was observed for HPV types 58 and 59. For HPV16 and HPV56, the imbalance did not attain statistical significance, suggesting a greater comparability between the assays for those types.

TABLE 3.

Post hoc analysis cross-tabulation of multiplex PCR assay detection and the INNO-LiPA v2 assay

| HPV type | No. of samples tested | No. of samples with multiplex PCR/LiPA v2 result of:

|

Agreement (%) | McNemar P valueg | Kappa (95% CI)a | Sensitivityb | Specificityc | Predictive value of positive resulte | Predictive value of negative resultf | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/− | −/+ | |||||||||

| 6 | 5,225 | 186 | 4,904 | 44 | 91 | 97.4 | <0.0001 | 0.72 (0.68, 0.77) | 0.671 | 0.991 | 0.809 | 0.982 |

| 11 | 5,226 | 35 | 5,122 | 4 | 65 | 98.7 | <0.0001 | 0.50 (0.40, 0.60) | 0.350d | 0.999 | 0.897 | 0.987 |

| 16 | 5,180 | 691 | 4,229 | 119 | 143 | 94.9 | 0.1552 | 0.81 (0.79, 0.83) | 0.829 | 0.973 | 0.853 | 0.967 |

| 18 | 5,223 | 274 | 4,810 | 46 | 93 | 97.3 | <0.0001 | 0.78 (0.75, 0.82) | 0.747 | 0.991 | 0.856 | 0.981 |

| 31 | 5,224 | 444 | 4,534 | 69 | 177 | 95.3 | <0.0001 | 0.76 (0.73, 0.79) | 0.715 | 0.985 | 0.865 | 0.962 |

| 33 | 5,220 | 238 | 4,891 | 34 | 57 | 98.3 | 0.0206 | 0.83 (0.80, 0.86) | 0.807 | 0.993 | 0.875 | 0.988 |

| 35 | 5,224 | 93 | 5,054 | 21 | 56 | 98.0 | <0.0001 | 0.70 (0.64, 0.76) | 0.624 | 0.996 | 0.816 | 0.989 |

| 39 | 5,217 | 260 | 4,803 | 45 | 109 | 97.0 | <0.0001 | 0.76 (0.72, 0.79) | 0.705 | 0.991 | 0.852 | 0.978 |

| 45 | 5,224 | 172 | 4,875 | 58 | 119 | 96.6 | <0.0001 | 0.64 (0.59, 0.69) | 0.591 | 0.988 | 0.748 | 0.976 |

| 51 | 5,214 | 391 | 4,579 | 40 | 204 | 95.3 | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.71, 0.77) | 0.657 | 0.991 | 0.907 | 0.957 |

| 52 | 5,222 | 424 | 4,517 | 52 | 229 | 94.6 | <0.0001 | 0.72 (0.69, 0.75) | 0.649 | 0.989 | 0.891 | 0.952 |

| 56 | 5,169 | 224 | 4,800 | 79 | 66 | 97.2 | 0.3190 | 0.74 (0.70, 0.78) | 0.772 | 0.984 | 0.739 | 0.986 |

| 58 | 5,224 | 148 | 4,941 | 103 | 32 | 97.4 | <0.0001 | 0.67 (0.62, 0.73) | 0.822 | 0.980 | 0.590 | 0.994 |

| 59 | 5,224 | 126 | 4,941 | 108 | 49 | 97.0 | <0.0001 | 0.60 (0.54, 0.66) | 0.720 | 0.979 | 0.538 | 0.990 |

| 68 | 5,098 | 106 | 4,751 | 30 | 211 | 95.3 | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.39, 0.50) | 0.334 | 0.994 | 0.779 | 0.957 |

CI, confidence interval.

The proportion of multiplex PCR-positive samples, among which are INNO-LiPA v2-positive samples.

The proportion of multiplex PCR-negative samples, among which are INNO-LiPA v2-negative samples.

The number of samples that were PCR positive for HPV11 was small (∼2%).

The proportion of INNO-LiPA v2-positive samples, among which are multiplex PCR-positive samples.

The proportion of INNO-LiPA v2-negative samples, among which are multiplex PCR-negative samples.

Values in boldface type indicate significance.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value (as defined above) were determined to compare the HPV multiplex PCR and INNO-LiPA v2 assay testing paradigms (Table 3). Overall, the sample set was largely HPV PCR negative for specific HPV types, lending greater power to the negative predictive value calculations than could be achieved from the data set for the positive predictive value. In contrast to that seen for the two test scheme, comparison of HCII followed by LiPA v2 with multiplex PCR assays (Table 1), in the post hoc direct comparison of INNO-LiPA v2 with the multiplex PCR assay (Table 3), the proportion of INNO-LiPA v2-negative samples among the multiplex PCR-negative samples was slightly reduced, and the proportion of INNO-LiPA v2-positive samples among the multiplex PCR-positive samples was slightly increased. The data set was also found to contain a very low percentage, ∼2%, of HPV11 PCR-positive samples, which decreased the power of the overall sensitivity calculation for HPV11.

Post hoc analysis: cross-tabulation between the HPV multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the INNO-LiPA v2 high-risk composite by SurePath diagnosis.

Cross-tabulations between the HPV multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the INNO-LiPAv2 high-risk composite are provided by SurePath diagnosis data shown in Table 4. Overall, there was reasonably good agreement between the INNO-PCR LiPA v2 and multiplex assays, with each of the SurePath diagnosis categories (agreement rates of 85.7%, 87.5%, 92.2%, and 94.9% for diagnoses of normal, ASCUS/LSIL-1, ASCUS/LSIL-2, and HSIL, respectively). For cytology samples diagnosed as being normal, there was evidence of a statistical imbalance in the number of discordant samples, with more samples testing multiplex PCR negative/INNO-LiPA v2 PCR positive than multiplex PCR positive/INNO-LiPA v2 PCR negative. Additionally, 59.8% of samples that were diagnosed as being normal were HPV PCR positive by one or both assays. For diagnoses of ASCUS/LSIL-1, ASCUS/LSIL-2, and HSIL, there was no statistical evidence of an imbalance in the number of discordant samples between the INNO-LiPA v2 and multiplex PCR assays, although the sensitivity of these comparisons was reduced relative to that for the normal-diagnosis set, as there were far fewer samples receiving these diagnoses than having a diagnosis of normal.

TABLE 4.

Post hoc analysis cross-tabulation between the multiplex PCR assay high-risk composite and the INNO-LiPA v2 high-risk composite by SurePath diagnosis

| SurePath diagnosis and LiPA v2 test result | Multiplex PCR result

|

Agreement (%) | McNemar P value | Kappa (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Normala | 85.7 | <0.0001 | 0.72 (0.70-0.74) | ||

| Positive | 2,100 | 538 | |||

| Negative | 120 | 1,855 | |||

| ASCUS/LSIL-1b | 87.5 | 0.6875 | 0.5 (0.16-0.84) | ||

| Positive | 38 | 2 | |||

| Negative | 4 | 4 | |||

| ASCUS/LSIL-2c | 92.2 | 0.2005 | 0.66 (0.55-0.77) | ||

| Positive | 320 | 19 | |||

| Negative | 11 | 36 | |||

| HSIL | 94.9 | 0.1797 | 0.61 (0.38-0.84) | ||

| Positive | 159 | 7 | |||

| Negative | 2 | 8 | |||

CI, confidence interval.

Diagnoses included kiolocytotic atypia, flat condyloma, and condyloma.

Diagnoses included atypical cells and mild dysplasia.

By contrasting the composite cross-tabulation results of the two tests, HCII followed by LiPA v2 in comparison with the multiplex PCR assays (Table 2), with the composite cross-tabulation results of the post hoc direct INNO-LiPA v2 analysis comparison with the multiplex PCR assays (Table 4), it appears that the most notable difference is in the agreement of normal samples determined by SurePath (87.1% [Table 2] versus 85.7% [Table 4]). For the other diagnoses, the agreement between the assays increased, which was a direct reflection of HCII-LiPA v2-negative/multiplex PCR-positive samples becoming INNO-LiPA v2 positive/multiplex PCR positive. The decrease in the agreement of the normal samples determined by SurePath was driven by a large number of double-negative samples (Table 2) becoming INNO-LiPA v2 positive/multiplex PCR negative (Table 4).

HPV genotype-positive clinical samples assigned based upon testing scheme and clinical assay.

The total numbers of HPV-positive samples determined by the two-test scheme of the HCII-LiPA v2 assay, the single L1 ORF PCR INNO-LiPA v2 assay, and the multiple-ORF HPV real-time PCR assay are presented in Table 5. As the multiplex PCR assay requires a twice-positive demonstration, the HPV multiplex PCR-positive samples have also been stratified by positive E6, E7, or L1 ORFs, and the percentages of the total positives are also presented for each ORF. Overall, the majority of samples were three-ORF positive. Less than 1% of the HPV multiplex PCR samples were single-ORF repeat positives (these samples were not included in the analyses). A few ORFs of specific HPV types had reduced positivity (HPV18 E6 [93%], HPV31 E7 [91%], HPV45 L1 [83%], and HPV58 L1 [91%]) compared with those of the other ORFs, illustrating the difficulty in the equal optimization of multiple, simultaneous PCR amplifications to detect all variants of a specific HPV type under conditions of potentially low copy numbers.

TABLE 5.

HPV genotype-positive clinical samples assigned based upon two tests (HCII-LiPA v2), the INNO-LiPA v2 assay (single L1 ORF amplification and hybridization), and HPV multiplex real-time PCR (L1 and/or E6 and E7 ORFs)

| HPV type | No. of positive samples (% ORF positive of total positive in multiplex PCR)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCII-LiPA v2 | INNO-LiPA v2 | Multiplex PCR

|

||||

| Multiple ORFs, twice positive | E6 | E7 | L1 | |||

| HPV6 | 201 | 277 | 230 | 219 (95) | 223 (97) | 225 (98) |

| HPV11 | 48 | 100 | 39 | 39 (100) | 38 (97) | 39 (100) |

| HPV16 | 686 | 834 | 810 | 777 (96) | 795 (98) | 790 (98) |

| HPV18 | 301 | 367 | 320 | 299 (93) | 317 (99) | 309 (97) |

| HPV31 | 526 | 621 | 513 | 512 (99) | 469 (91) | 506 (99) |

| HPV45 | 236 | 291 | 230 | 225 (98) | 226 (98) | 190 (83) |

| HPV52 | 495 | 653 | 476 | 466 (98) | 463 (97) | 465 (98) |

| HPV58 | 146 | 180 | 251 | 248 (99) | 243 (97) | 228 (91) |

| HPV33 | 249 | 295 | 272 | 272 (100) | 272 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV35 | 110 | 149 | 114 | 114 (100) | 114 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV39 | 290 | 369 | 305 | 305 (100) | 305 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV51 | 475 | 595 | 431 | 431 (100) | 431 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV56 | 232 | 290 | 303 | 303 (100) | 303 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV59 | 130 | 175 | 234 | 234 (100) | 234 (100) | Not tested |

| HPV68 | 220 | 317 | 136 | 136 (100) | 136 (100) | Not tested |

| Composite | 4,345 | 5,513 | 4,664 | 4,580 (98) | 4,569 (98) | —a (96) |

Percentage based on multiplex PCR total of the first eight rows.

DISCUSSION

The comparisons described herein examine the results of genotype testing by real-time HPV multiplex PCR assays and a method which involves a two-test process of initial screening by HCII followed by genotyping of the HCII-positive samples using an HPV PCR line hybridization assay, the INNO-LiPA v2 assay. Comparisons were drawn for HPV types common to both assays: types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68. Cross-tabulation analysis was performed by using a composite of the HPV high-risk type results for the two testing schemes stratified by SurePath cytology diagnosis. The evaluation utilized SurePath residual specimens from a cohort of Denmark women who were sampled to assess the prevalence of HPV infection. To this end, the comparisons were made based upon specimens with unknown outcomes; aside from the controls in the assays, there were no known positive samples or known negative samples analyzed; the results of the testing methods were therefore analyzed relative to each other.

The assays were performed under stringent conditions, which included separate laboratories for reagent preparation, sample DNA isolation, and thermal cycling. To ensure the accuracy and consensus from the multiple-ORF testing by HPV multiplex PCR, stringent criteria governing the acceptance of a PCR result were established. Provided that the controls were within specification, if at least two HPV ORFs were amplified (any combination of E6, E7, or L1), the sample result was positive for a given HPV type.

The multiplex PCR assays and the two-test process composed of the HCII-LiPA v2 assays have the advantage of providing confidence in the outcome, as both assays embrace a “twice-positive” approach. Reproducibility, whether it is demonstrated by amplification of multiple ORF targets or by HPV DNA by two hybridization methods, provides greater precision in the recorded outcome. The specificity and predictive values of a negative result were extremely high when these two genotype assay schemes were compared (≥0.96 for all HPV types evaluated) (Table 1), and thus, the expected false-negative rate would be predicted to be extremely low. The overall agreement was >95.5%. There was some discordance, with more samples testing positive by HPV multiplex PCR for HPV types 6, 16, 33, 56, 58, and 59 and more samples testing positive by the HCII-LiPA v2 assay for HPV types 51 and 68. The requirement that more than one HPV type-specific ORF needed to be amplified in order to designate a sample as being HPV type-specific multiplex PCR positive provided a high level of confidence that the sample was truly HPV positive for a specific HPV type. Additionally, amplification of the E6 and E7 ORFs increases the sensitivity of the detection in that viral integration can lead to a disruption in the L1 ORF. The type- and ORF-specific primers and probes ensure the accuracy of the type-specific result. Although the normal real-time HPV multiplex PCR assay algorithm for the quadrivalent HPV vaccine program utilizes more starting material, the protocol was adjusted for this study to approximate a similar quantity of input material used, based upon cell suspension input volume. As run, HPV types 11, 18, 31, 33, 39, 45, and 52 were statistically comparable between the assays.

The post hoc analysis comparing the HPV multiplex PCR assay directly with the INNO-LiPA v2 assay presented somewhat different results. The INNO-LiPA v2 assay is a consensus-primer PCR-based assay that gains specificity through postamplification hybridization. A portion of the single ORF L1 was amplified and assayed one time. Thus, in this testing approach, the HPV result stems from a single evaluation of a single HPV ORF. Relative to the comparison between HPV multiplex PCR and the HCII-LiPA v2 two-test process, the HPV multiplex PCR versus the INNO-LiPA v2 assay had reduced predictive values of negative results across all types (Table 3) and reduced overall agreement, and only HPV16 and HPV56 were shown to be statistically comparable between the assays.

Stratifying the composite high-risk results relative to the SurePath diagnosis (Tables 2 and 4) revealed notable differences between the HCII-LiPA v2 and INNO-LiPA v2 assay results relative to the HPV multiplex PCR assay results. In all cases of diagnoses with possible or probable HPV disease (ASCUS/LSIL-1, LSIL-2, and HSIL), the agreement with the HPV multiplex PCR assays increased slightly in the post hoc assays with the INNO-LiPA v2 assay compared to the HCII-LiPA v2 assay. There is an increase in the number of multiplex PCR-positive/INNO-LiPA v2-positive results for all three diagnoses and a corresponding decrease in the numbers of multiplex PCR-positive/INNO-LiPA v2-negative results. These data suggest that the INNO-LiPA v2 test is more sensitive than the HCII test, and thus, in the two-test process, the detection of positive results may be restricted by the sensitivity limitations of the HCII assay.

The agreement with the HPV multiplex PCR assays, however, decreased in the post hoc analysis with the INNO-LiPA v2 assay compared to the HCII-LiPA v2 assay in the cases of a normal diagnosis, with the discordance flipping to more multiplex PCR-negative/INNO-LiPA v2-positive than multiplex PCR-positive/HCII-LiPA v2-negative results. In other words, in the SurePath normal-diagnosis set, removing the HCII sensitivity limitation in the post hoc multiplex PCR versus INNO-LiPA v2 analysis showed an overall increase in the number of INNO-LiPA v2-positive samples. There was better agreement in the number of multiplex PCR-positive/INNO-LiPA v2 positive results than with the HCII-LiPA v2 test. The difficulty that appears to have arisen is that in gaining greater sensitivity by direct INNO-LiPA v2 testing, the specificity measurement was inversely affected. A substantial increase in numbers of multiplex PCR-negative/INNO-LiPA v2-positive samples was seen, which decreased the agreement in assigning a negative result.

Overall, there is good agreement (kappa of >0.5) and high sensitivity and specificity between the HPV multiplex PCR and either the HCII-LiPA v2 or INNO-LiPA v2 testing paradigms for the presence of HPV DNA in clinical specimens. The sensitivity of the INNO-LiPA v2 assay appears to be greater than that of the HCII assay, and thus, in the two-test process consisting of HCII-LiPA v2, the sensitivity in identifying positive samples is slightly reduced by the HCII sensitivity limitations. There is a greater range of variability in the sensitivity measures depending upon the HPV type examined. This increased range of variability was likely influenced by the overall prevalence of a given HPV type in the sample set. As the overall specimen volume for HPV multiplex PCR assay testing was modified based upon cell suspension to approximate the final input into the LiPA v2 strip hybridization assay, it is possible that if conducted with the optimal sample input, the HPV multiplex PCR assay may gain in sensitivity across all HPV types tested. The greatest discordance between the assays appears to be in the ability to distinguish negative samples. The “twice-positive” approaches in two-test (HCII-LiPA v2) and HPV multiplex PCR assays (two ORFs) had greater agreement than the INNO-LiPA v2 assay versus HPV multiplex PCR assays. Because of the confidence gained from demonstrating the presence of HPV DNA twice and likewise testing twice (two tests or two ORFs) versus one time (one ORF), demonstrating that HPV DNA was not found, the data presented in this study suggest that the INNO-LiPA v2 assay might have a slightly lower specificity than the multiplex PCR assays and the HCII-LiPA v2 two-test process.

Stratifying the data by SurePath cytology diagnosis provided a glimpse into the detection limitation of cytology diagnoses. The results of both PCR testing paradigms compared to the SurePath cytology diagnosis revealed that 53% and 59% of cytologically normal samples were found to be PCR positive. This suggests that many latent HPV infections with no apparent underlying disease, which would otherwise not be diagnosed, are detectable with highly sensitive PCR methods.

The twice-positive algorithm, when applied to either HPV multiplex PCR or the HCII-LiPA v2 testing paradigm, provided confidence in the results via the reproducibility of the HPV DNA detection result. The assays were more comparable when both assays utilized the twice-positive algorithm (HCII-LiPA v2 and HPV multiplex PCR) than when one of the assays used only a one-time, one-ORF algorithm (INNO-LiPA v2). The HPV multiplex PCR and the HCII-LiPA v2 HPV genotyping PCR assays are, by and large, comparable and provide highly sensitive and specific HPV DNA genotype detection. Future studies comparing the HPV genotyping assays under performance-optimized conditions and accessing known positive and known negative samples will enhance our understanding of the comparabilities and limitations of HPV multiplex PCR assays and the HCII and INNO-LiPA v2 assays in accurately identifying type-specific HPV DNA within a sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the investigators who took part in the studies contributing to the data presented herein. We also thank Scott Vuocolo for help in the preparation of the manuscript and Betti Schopp, Beate Gregg, Annette Rothe, and Barbara Holz for excellent technical assistance.

The HPV multiplex PCR assay testings included in this report were funded entirely by Merck Research Laboratories, a division of Merck & Co., Inc. L.G., R.S., J.A., J.T.B., and F.J.T. are employees of Merck & Co., Inc., and may potentially own stock and/or hold stock options in the company. S.K.K. has received consultancy fees and has received funding through her institution to conduct HPV vaccine studies for Sanofi Pasteur MSD, Merck & Co., Inc., and Digene.

As first and corresponding authors, T.I. and J.T.B. are responsible for the work described in this paper. All authors were involved in at least one of the following: conception, design, acquisition, analysis, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and/or revising of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brennan, M. M., H. A. Lambkin, C. D. Sheehan, D. D. Ryan, T. C. O'Connor, and W. F. Kealy. 2001. Detection of high-risk subtypes of human papillomavirus in cervical swabs: routine use of the Digene Hybrid Capture assay and polymerase chain reaction analysis. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 5824-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FUTURE II Study Group. 2007. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 3561915-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garland, S. M., M. Hernandez-Avila, C. M. Wheeler, G. Perez, D. M. Harper, S. Leodolter, G. W. K. Tang, D. G. Ferris, M. Steben, J. T. Bryan, F. J. Taddeo, R. Railkar, M. T. Esser, H. L. Sings, M. Nelson, J. Boslego, C. Sattler, E. Barr, and L. A. Koutsky. 2007. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 3561928-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gheit, T., S. Landi, F. Gemignani, P. J. Snijders, S. Vaccarella, S. Franceschi, F. Canzian, and M. Tommasino. 2006. Development of a sensitive and specific assay combining multiplex PCR and DNA microarray primer extension to detect high-risk mucosal human papillomavirus types. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442025-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen, K., F. J. Taddeo, L. Weili, and A. C. DiCello. March 2003. Fluorescent multiplex HPV PCR assays using multiple fluorophores. WO patent 2003/019143 A2.

- 6.Kjaer, S. K., G. Breugelmans, and C. Munk. 2008. Population-based prevalence, type- and age-specific distribution of HPV in women before introduction of HPV-vaccination program in Denmark. Int. J. Cancer 1231864-1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleter, B., L. J. van Doorn, L. Schrauwen, A. Molijn, S. Sastrowijoto, J. ter Schegget, J. Lindeman, B. ter Harmsel, M. Burger, and W. Quint. 1999. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 372508-2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safaeian, M., R. Herrero, A. Hildesheim, W. Quint, E. Freer, L. J. van Doorn, C. Porras, S. Silva, P. Gonzalez, M. C. Bratti, A. C. Rodriguez, and P. Castle. 2007. Comparison of the SPF10-LiPA system to the Hybrid Capture 2 assay for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus genotypes among 5,683 young women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451447-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sotlar, K., A. Stubner, D. Diemer, S. Menton, M. Menton, K. Dietz, D. Wallwiener, R. Kandolf, and B. Bultmann. 2004. Detection of high-risk human papillomavirus E6 and E7 oncogene transcripts in cervical scrapes by nested RT-polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Virol. 74107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taddeo, F. J., D. M. Skulsky, X. M. Wang, and K. U. Jansen. November 2006. Real-time HPV PCR assays. WO patent 2006/116276 A2.

- 11.Taddeo, F. J., D. M. Skulsky, X. M. Wang, and K. U. Jansen. November 2006. Fluorescent multiplex HPV PCR assay. WO patent 2006/116303 A2.

- 12.van Doorn, L. J., A. Molijn, B. Kleter, W. Quint, and B. Colau. 2006. Highly effective detection of human papillomavirus 16 and 18 DNA by a testing algorithm combining broad-spectrum and type-specific PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443292-3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Hamont, D., M. A. van Ham, J. M. Bakkers, L. F. Massuger, and W. J. Melchers. 2006. Evaluation of the SPF10-INNO LiPA human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping test and the Roche linear array HPV genotyping test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443122-3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walboomers, J. M. M., M. V. Jacobs, M. M. Manos, F. X. Bosch, A. Kummer, K. V. Shah, and P. J. F. Snijders. 1999. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 18912-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. 2004. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/hpv/en/.