Abstract

We have studied by PCR and DNA sequencing the presence of the qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, qepA, intI1, and ISCR1 genes in 200 clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae (n = 153) and E. aerogenes (n = 47) consecutively collected between January 2004 and October 2005 in two hospitals located in Santander (northern Spain) and Seville (southern Spain). Mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region of gyrA and parC also were investigated in organisms containing plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes. The isolates had different resistant phenotypes, including AmpC hyperproduction, extended-spectrum β-lactamase production, resistance or decreased susceptibility to quinolones, and/or resistance to aminoglycosides. Among the 116 E. cloacae isolates from Santander, qnrS1, qnrB5, qnrB2, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were detected in 22 (19%), 1 (0.9%), 1 (0.9%), and 3 (2.6%) isolates, respectively. Twenty-one, 17, and 2 qnrS1-positive isolates also contained blaLAP-1, intI1, and ISCR1, respectively. A qnrB7-like gene was detected in one E. aerogenes isolate from Santander. No plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene was detected in the isolates from Seville. The qnrS1-containing isolates corresponded to four pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns and showed various levels of resistance to quinolones. Six isolates were susceptible to nalidixic acid and presented reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. The qnrS1 gene was contained in a conjugative plasmid of ca. 110 kb, and when the plasmid was transferred to recipient strains that did not have a specific mechanism of quinolone resistance, the ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 0.047 to 0.125 μg/ml.

Resistance to quinolones in enterobacteria is increasing worldwide (8, 24). Previous studies have demonstrated that in this group of organisms, multiple mechanisms are involved in this problem, including altered type II topoisomerases, decreased permeability, increased active efflux, target protection, and drug modification (8, 18, 33). Most of the genes coding for these mechanisms are of chromosomal origin, but since 1998, when qnrA1 was discovered in a clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae from the United States (18), several plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes (9) have been reported from clinical isolates, including new qnrA variants, multiple qnrB and qnrS alleles, qnrC, qnrD, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and two qepA alleles (4, 8, 17, 44).

Qnr proteins protect type II topoisomerases from quinolone attack (38, 39). Aac(6′)-Ib-cr modifies quinolones containing a piperazinyl group (31), and QepA proteins are involved in active efflux (25). Plasmid-borne genes involved in quinolone resistance cause low-level resistance to quinolones (18, 29) and have an additive effect on the level of resistance caused by other mechanisms (19, 28).

qnrA has been identified in complex sul1-type integrons of the In4 family (39). These integrons contain the ISCR1 sequence (37), which codes for a recombinase involved in the mobilization of antibiotic resistance genes in its proximity. The qnrB gene also is associated with ISCR1 as well as with another presumed recombinase, Orf1005 (11). qnrS is not part of an integron, but it often is bracketed by inverted repeats with insertion sequence-like structures (7).

PMQR genes have been found worldwide in multiple species of enterobacteria (18, 29), being particularly frequent in Enterobacter (more often E. cloacae) (10, 12, 16, 22, 23, 30, 32, 35, 42), Klebsiella pneumoniae (10, 16, 25, 30, 32, 35, 43), and Escherichia coli (16, 25, 30, 32). Interestingly, on some occasions more than one PMQR gene has been identified in the same organism (18, 29).

In a previous study by our group (unpublished data), we did not detect PMQR genes in K. pneumoniae or in E. coli, but we identified the qnrA1 gene in one isolate of E. cloacae and one of Citrobacter freundii from a single patient in Santander.

In the study reported here, we focused on the detection of qnrA, qnrS, qnrB, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, or qepA in E. cloacae and E. aerogenes, the two more clinically relevant species in the genus Enterobacter. The recently described qnrC (43) and qnrD (4) genes were not included in this study, as these descriptions were not known when the study was planned. The study also aimed to compare the incidence of these genes in two different geographical locations: Santander (northern Spain) and Seville (southern Spain).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

We evaluated 200 clinical isolates (1 per patient) of E. cloacae and E. aerogenes collected at the University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla in Santander (138 isolates: 116 E. cloacae and 22 E. aerogenes) and the University Hospital Virgen Macarena in Seville (62 isolates: 37 E. cloacae and 25 E. aerogenes) between January 2004 and October 2005. The organisms were selected as consecutive isolates presenting resistance to β-lactams (including AmpC hyperproduction or extended-spectrum β-lactamase production), resistance or decreased susceptibility to quinolones, and/or resistance to aminoglycosides. Identification and preliminary susceptibility testing were performed by the MicroScan WalkAway 96 system (Dade Behring, West Sacramento, CA) in Santander and by the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux, Hazelwood, MO) in Seville. E. coli ATCC 25922 and ATCC 35218 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were routinely used in the two centers for quality control purposes. Results obtained with Etest strips of ciprofloxacin were controlled using E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa 27853, those of nalidixic acid with E. coli ATCC 25922, and those of ticarcillin-clavulanate with E. coli ATCC 35218, by testing them in parallel to clinical isolates.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

All 200 isolates were screened by PCR. The corresponding primers and expected amplicon sizes are presented in Table 1. Genomic DNA was extracted using the InstaGene matrix kit (Bio-Rad, Madrid, Spain) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and 1 μl was added to a reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM each primer, and 1 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Madrid, Spain). The amplification conditions were 94°C for 10 min, and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. A multiplex PCR was developed for detecting intI1, ISCR1, and qnrA, and independent PCRs were used for detecting qnrB, qnrS, qepA, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr. Positive controls for the presence of qnrA1 (20), qnrB1 (11), qnrS1 (7), aac(6′)-Ib-cr (17), and qepA1 (25) were included.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR and expected amplicon sizes

| Gene or assay | Primer | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| qnrA | 5′-GAT AAA GTT TTT CAG CAA GAG G-3′ | 543 | 10 |

| 5′-ATC CAG ATC GGC AAA GGT TA-3′ | |||

| qnrB | 5′-GGC ATT GAA ATT CGC CAC TG-3′ | 360 | This study |

| 5′-TTT GCT GCT CGC CAG TCG A-3′ | |||

| qnrS | 5′-TGG AAA CCT ACA ATC ATA CA-3′ | 599 | This study |

| 5′-TGC AAT TTT GAT ACC TGA TG-3′ | |||

| aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 5′-ATG ACT GAG CAT GAC CTT GC-3′ | 519 | 13 |

| 5′-TTA GGC ATC ACT GCG TGT TC-3′ | |||

| qepA | 5′-AAC TGC TTG AGC CCG TAG AT-3′ | 189 | This study |

| 5′-CGT GTT GCT GGA GTT CTT CC-3′ | |||

| intI1 | 5′-GCG AAG TCG AGG CAT TTC TGT C-3′ | 767 | This study |

| 5′-ATG CGT GTA AAT CAT CGT CGT AGA GA-3′ | |||

| ISCR1 | 5′-CGC CCA CTC AAA CAA ACG-3′ | 469 | 34 |

| 5′-GAG GCT TTG GTG TAA CCG-3′ | |||

| gyrA | 5′-AAA TCT GCC CGT GTC GTT GGT-3′ | 343 | 41 |

| 5′-GCC ATA CCT ACG GCG ATA CC-3′ | |||

| parC | 5′-ATG TAC GTG ATC ATG GAC CG-3′ | 300 | This study |

| 5′-ATT CGG TGT AAC GCA TCG CC-3′ | |||

| blaLAP-1 | 5′-CAA TAC AAA GCA CAG AAG ACC-3′ | 748 | 26 |

| 5′-CCG ATC CCT GCA ATA TGC TC-3′ | |||

| REP-PCR | 5′-III-GCG CCG ICA TCA GGC-3′ | Variable | 40 |

| 5′-ACG TCT TAT CAG GCC TAC-3′ |

The quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of gyrA and parC and the presence of blaLAP-1 also were screened by PCR in strains containing PMQR genes by following previously described conditions (26, 41) and using the primers shown in Table 1.

Amplicons were purified with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Izasa, Barcelona, Spain). The sequencing of both strands was performed at the Molecular Genetics Unit of the University Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla using a CEQ 2000 Dye Terminator for cycle sequencing with the Quick Start kit (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) or at the SCAI laboratory (Cordoba, Spain) using the Big Dye Terminator v3.0 sequencing kit and an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The BLAST program was used to compare the nucleotide and protein sequences to those available on the internet at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs of ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, ticarcillin, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid against isolates containing PMQR genes were determined with Etest strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For other antimicrobial agents, MICs were determined with the MicroScan WalkAway 96 system in Santander and by the Vitek 2 system in Seville.

Molecular fingerprinting.

Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (REP-PCR) typing was performed on E. cloacae isolates containing PMQR genes (Table 2). Amplicons were run in a 1.5% agarose gel for 100 min, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed. After visual inspection, two isolates were considered to be clonally unrelated when two or more different bands were observed.

TABLE 2.

MICs, REP-PCR patterns, resistance genes, and changes in topoisomerases in Enterobacter spp.a

| Isolate | Organism | Sample source | Ward | MIC (μg/ml)

|

REP-PCR pattern | PFGE pattern | PMQR | Presence of:

|

Changes in:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ | T-CL | CIP | NAL | AMK | TOB | blaLAP-1 | int1 | ISCR1 | DNA-gyrase | Topoisomerase IV | |||||||

| 1599 | E. cloacae | Abdominal drainage | Internal medicine | >16 | 96 | 0.38 | 8 | <8 | <4 | A | A1 | qnrS1 | + | − | − | WT | WT |

| 2531 | E. cloacae | Blood | Hematology | >16 | 96 | 0.38 | 8 | <8 | <4 | A | A1 | qnrS1 | + | − | − | WT | WT |

| 1480 | E. cloacae | Wound | Nephrology | >16 | 128 | 0.38 | 8 | <8 | <4 | A | A1 | qnrS1 | + | − | − | WT | WT |

| 3249 | E. cloacae | Wound | Domicil. hospital | >16 | 128 | 0.38 | 8 | <8 | <4 | A | A1 | qnrS1 | + | − | − | WT | WT |

| 3174 | E. cloacae | Wound | Domicil. hospital | >16 | >256 | 1.5 | 32 | <8 | <4 | B | B | qnrS1 | − | + | − | WT | WT |

| 3210 | E. cloacae | Urine | Urology | <1 | 48 | 2 | 8 | <8 | 8 | C | A2 | qnrS1 | + | + | + | WT | WT |

| 1640 | E. cloacae | Catheter tip | Internal medicine | >16 | 128 | 3 | >256 | <8 | <4 | D | C | qnrS1 | + | − | − | S83I | WT |

| 3049 | E. cloacae | Catheter tip | Urology | <1 | 16 | 4 | 16 | <8 | 8 | C | A2 | qnrS1 | + | + | + | WT | WT |

| 3138 | E. cloacae | Urine | Cardiovascular surgery | >16 | 12 | 32 | >256 | <8 | 8 | E | D1 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 248 | E. cloacae | Tracheal aspirate | ICU | <1 | 12 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D2 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 366 | E. cloacae | Tracheal aspirate | ICU | <1 | 6 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D2 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 437 | E. cloacae | Sputum | Internal medicine | <1 | 12 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D2 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 442 | E. cloacae | Tracheal aspirate | ICU | <1 | 12 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D2 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 533 | E. cloacae | Sputum | ICU | <1 | 16 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D2 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 812 | E. cloacae | Sputum | ICU | <1 | 16 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D3 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 930 | E. cloacae | Sputum | ICU | <1 | 16 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D3 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 1034 | E. cloacae | Urine | Internal medicine | <1 | 48 | >32 | >256 | <16 | <4 | E | D4 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 1137 | E. cloacae | Wound | Pneumology | <1 | 3 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D5 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 1619 | E. cloacae | Wound | Internal medicine | >16 | >256 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D6 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 2376 | E. cloacae | Abdominal drainage | Internal medicine | <1 | 8 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D7 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 3164 | E. cloacae | Urine | Gastroenterology | <1 | 12 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | E | D8 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I | S80I |

| 469 | E. cloacae | Urine | Outpatient | <1 | 1.5 | >32 | >256 | <16 | <4 | E | D9 | qnrS1 | + | + | − | S83I D87N | S80I |

| 258 | E. cloacae | Urine | Outpatient | <1 | 256 | 0.032 | 2 | <16 | >8 | F | ND | aac(6′) | ND | + | − | ND | ND |

| 3157 | E. cloacae | Blood | Gastroenterology | <1 | 64 | 1 | 16 | <8 | 8 | G | ND | aac(6′) | ND | + | − | ND | ND |

| 2903 | E. cloacae | Wound | Oncology | 16 | >256 | 6 | >256 | <8 | 8 | H | ND | aac(6′) | ND | + | − | ND | ND |

| 1895 | E. cloacae | Blood | Urology | <1 | 32 | 1 | 32 | <8 | >8 | I | ND | qnrB5 | ND | − | − | ND | ND |

| 3338 | E. cloacae | Urine | Cardiology | >16 | 48 | 1,5 | >256 | <8 | >8 | J | ND | qnrB2 | ND | + | + | ND | ND |

| 3383 | E. aerogenes | Urine | Outpatient | >16 | >256 | >32 | >256 | <8 | <4 | NA | NA | qnrB7-like | ND | − | − | ND | ND |

Domicil., domiciliary; ICU, intensive care unit; ND, not determined; NA, not applicable (one single isolate). Drug abbreviations: CAZ, ceftazidime; T-CL, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid; AMK, amikacin; and TOB, tobramycin.

Additionally, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed on all qnrS1-containing isolates with a CHEF-DR-II system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). DNA in agarose plugs was digested overnight with XbaI at 37°C. DNA was electrophoresed for 7 h (1- to 15-s pulse ramp) and 16 h (15- to 35-s pulse ramp) at 14°C in a 1% agarose gel at 6 V/cm. The interpretation of PFGE patterns was based on the criteria of Tenover et al. (36).

Conjugation experiments.

After results of PMQR genes detection were obtained (see below), one isolate of qnrS1-producing E. cloacae that was representative of each REP-PCR pattern was selected for conjugation experiments. Matings were performed on 0.22-μm nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) with E. coli J53, which is resistant to rifampin (rifampicin), as the recipient. After 2 h of incubation, mating mixtures were plated onto agar containing rifampin (100 mg/liter) and ciprofloxacin (0.03 mg/liter). The presence of qnrS1 was confirmed in the transconjugants by PCR, as described above.

Plasmid analysis.

Plasmids were detected in qnrS1-containing isolates and derived transconjugants using DNA S1 nuclease treatment followed by PFGE as described by Barton et al. (1). Lambda Ladder PFGE Marker from New England Biolabs (IZASA SA, Barcelona, Spain) was used as the size marker.

Plasmid DNA of qnrS1-positive isolates and transconjugants separated in PFGE gels was transferred onto a nylon membrane and probed for the presence of qnrS1. The probe specific for the qnrS1 gene consisted of a 599-bp PCR fragment amplified from whole-cell DNA of E. coli strain DH5α containing the plasmid pBC-H2.6. The labeling of the probe and signal detection were carried out using a DIG-High-Prime labeling and luminiscent detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

The qnrS1 gene was detected in 22 out of the 116 E. cloacae isolates from Santander (19%) and was not detected in any isolate from Seville. qnrB5 and qnrB2 were identified in two other E. cloacae isolates. Finally, the sequencing of one of the amplicons allowed us to identify a qnrB7-like gene (coding for an Asp197Gly change in the corresponding QnrB7 sequence) in E. aerogenes. The latter three isolates also were from Santander. aac(6′)-Ib-cr was detected in three E. cloacae isolates (lacking qnr genes) from Santander, and an additional isolate of E. cloacae also carried the aac(6′)-Ib gene (lacking the mutations involved in quinolone resistance). Neither qepA nor qnrA alleles were found in any of the tested isolates from Santander or from Seville.

The 22 organisms containing qnrS were cultured from tracheal aspirates (n = 3), sputa (n = 4), urine (n = 5), blood (n = 1), wound exudates (n = 5), catheter tips (n = 2), or abdominal drainages (n = 2). The patients from whom E. cloacae with qnrS1 were cultured had been admitted to 12 different wards in two different buildings of our institution. Three patients were not hospitalized when the qnrS1-containing E. cloacae strain was isolated, including two patients on a home health care program and one outpatient. The three isolates with aac(6′)-Ib-cr were cultured from urine (n = 2) and blood (n = 1), while the three qnrB-containing isolates were obtained from urine (n = 1), blood (n = 1), and wound exudates (n = 1).

Five REP-PCR patterns were observed among the 22 E. cloacae isolates containing qnrS1, including 4 type A, 1 type B, 2 type C, 1 type D, and 14 type E isolates (Table 2). Types A and C were considered possibly related by PFGE according to Tenover's criteria. The three E. cloacae isolates containing aac(6′)-Ib-cr were clonally unrelated, as were the two isolates with qnrB genes. The latter two groups of organisms also were unrelated to any of the qnrS1-containing isolates.

Data of susceptibility to quinolones of qnrS1-containing E. cloacae isolates are presented in Table 2. A strong correlation between the phenotype of resistance to quinolone and the PFGE type was detected. All 14 qnrS1-positive isolates of REP-PCR pattern E were highly resistant to both nalidixic acid (MIC > 256 μg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (MIC > 32 μg/ml) and contained mutations at the gyrA and parC genes that were responsible for the changes Ser83Ile (DNA-gyrase) and Ser80Ile (topoisomerase IV), respectively. In addition, one of these isolates also contained a gyrA mutation that was responsible for the change Asp87Asn.

The four isolates with REP-PCR pattern A were susceptible to nalidixic acid but presented decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. They did not contain any change at the QRDR of gyrA and parC in comparison to the reported wild-type sequence of E. cloacae. In the single isolate of REP-PCR pattern D, a mutation in gyrA (causing a Ser83Phe change) was observed that correlated with resistance to nalidixic acid. The remaining three isolates (patterns B and C) lacked any mutation in the QRDR of gyrA and parC and were either susceptible or resistant to nalidixic acid and intermediate or resistant to ciprofloxacin (Table 2).

Transconjugants were obtained from isolates of REP-PCR types A, C, and E. The MICs of nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin for the transconjugants ranged from 4 to 32 and 0.047 to 0.125 μg/ml, respectively.

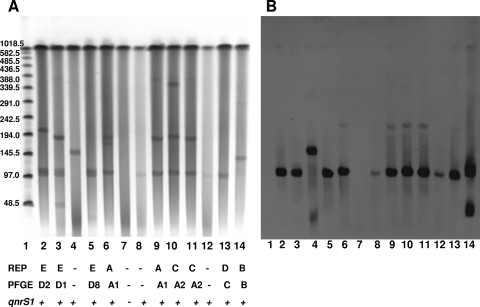

Plasmid analysis showed that the studied isolates possessed one to three large plasmids, with sizes ranging from ca. 110 to ca. 350 kb. The qnrS1 gene was associated to the 110-kb plasmid, although in one of three transconjugants studied, the gene was associated with a plasmid of larger size (ca. 150 kb). As shown in the Fig. 1, some of the transconjugants from E. cloacae 2531 (REP-PCR pattern A) lacked the plasmid observed in true transconjugants with qnrS1 and did not contain the qnrS1 gene. As these organisms were proven by PCR to contain qnrS1 when first isolated in the selection plate of the conjugation assay, they may represent transconjugants that have lost the plasmid upon subculture, but further studies were not done with these organisms.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of plasmid DNA from E. cloacae parental isolates and derived transconjugants by pulsed-field agarose gel electrophoresis (A) and Southern blotting (B). Lanes: 1, molecular marker; 2, E. cloacae 248; 3, E. cloacae 3138; 4, qnrS1-positive transconjugant from E. cloacae 3138; 5, E. cloacae 3164; 6, E. cloacae 2531; 7, transconjugant from E. cloacae 2531 lacking qnrS1; 8, qnrS1-positive transconjugant from E. cloacae 2531; 9, E. cloacae 3249; 10, E. cloacae 3049; 11, E. cloacae 3210; 12, transconjugant from E. cloacae 3210; 13, E. cloacae 1640; 14, E. cloacae 3714.

All qnrS1-positive isolates, except the one with REP-PCR pattern B (see below), contained the blaLAP-1 gene. However, none of the transconjugants obtained from them was resistant to ticarcillin (MIC, 1.5 to 3 μg/ml).

Seventeen of these isolates contained the intI1 gene, two of which also carried ISCR1. Among the 200 isolates tested, intI1 was detected in 61 isolates from Santander (58 E. cloacae and 3 E. aerogenes) and in 10 isolates from Seville (8 E. cloacae and 2 E. aerogenes). ISCR1 was detected only in E. cloacae (29 and 2 isolates in Santander and Seville, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Several previous reports indicate that PMQR genes are particularly common in E. cloacae and E. aerogenes (for a review, see reference 18). To expand our knowledge about the distribution of PMQR determinants, we screened a collection of Enterobacter spp. from two hospitals from northern and southern Spain.

There are no phenotypic markers that indicate the presence of PMQR genes in a concrete organism. Several of the primers we used (Table 1) were obtained from previous reports on PMQR genes in enterobacteria. Similarly, the other primers in that table will be helpful for a more complete study of genes directly or indirectly related to quinolone resistance in enterobacteria. As the number of qnr families is increasing, a multiplex PCR may be used in epidemiological surveys on PMQR genes. Previous studies indicate that strains containing PMQR genes usually express other mechanisms of resistance; for this reason, we included isolates that are resistant to any of the commonly used antimicrobial agents. On the other hand, as some qnr genes are located within a complex type 1 integron containing int1 and ISCR1, we additionally looked for these two genes.

Although qnrA1 was the first PMQR gene discovered, several studies have indicated that other genes [particularly qnrS1, some qnrB alleles, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr] are more common (reviewed in reference 18). This was the case in this study, where qnrS1 has been the more frequent PMQR gene, being present in 19% of the E. cloacae isolates from Santander. In this area, qnrB alleles and the aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene also were found, but less commonly. On the other hand, none of these genes was detected in the Enterobacter isolates from Seville, indicating that relevant differences in the prevalence of PMQR genes can occur within the same country. These results may represent differences in local resistance rates of Enterobacter (likely related to antibiotic use or infection control policies) in the two participating centers. Because the organisms included in this study were selected as being resistant to commonly used antimicrobial agents, we cannot yet make clear conclusions about the current prevalence of PMQR genes in the two regions considered in this study. We currently are studying enterobacteria isolated consecutively from clinical samples (without taking into consideration their resistance profile) to obtain information on this issue.

E. cloacae isolates containing qnrS1 were susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to quinolones. Hata et al. reported (7) that a qnrS-containing Shigella flexneri strain has changes at the QRDR of both GyrA (Ser83Leu) and ParC (Ser80Ile). In our case, the 14 isolates of REP-PCR pattern A presented changes in both DNA-gyrase and topoisomerase IV, which are known to be associated by themselves with quinolone resistance. This is similar to what has been described for organisms containing other PMQR genes, in which mutations in topoisomerase-coding genes also are frequent.

On the other hand, several E. cloacae isolates (of three different REP-PCR patterns; Table 2) lacking mutations at the QRDR of gyrA and parC were susceptible to nalidixic acid and presented decreased susceptibility or showed intermediate or low-level resistance to ciprofloxacin. This pattern of resistance is unexpected, as multiple studies previously have indicated that enterobacteria with decreased susceptibility or intermediate resistance to fluoroquinolones are highly resistant to nalidixic acid. Hakanen et al. (6) described Salmonella enterica from southeast Asia that is susceptible to nalidixic acid but exhibits reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin; new studies of this organism indicate that it contains the qnrS1 gene (2, 21). We also have observed (3) that PMQR genes are found rather frequently in strains susceptible to nalidixic acid and with decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. The various levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin in the studied isolates anticipates that other mechanisms of resistance (such as mutations outside the QRDR of gyrA/parC, mutations in gyrB/parE, active efflux, or decreased permeability) or differences in gene expression may be involved in individual isolates.

In addition to qnrS1, two E. cloacae isolates contained qnrB alleles (qnrB5 and qnrB2), and three other isolates contained the gene coding for the fluoroquinolone-modifying acetyltransferase Aac(6′)-Ib-cr. One strain of E. aerogenes expressed a qnrB7-like gene that coded for a protein differing from QnrB7 by (at least) a single change (Asp197Gly). Studies for determining the complete sequence of this new variant are in progress.

As expected from our inclusion criteria, E. cloacae strains containing qnrS1 presented different phenotypes of susceptibility to antimicrobial agents other than quinolones. All intI1-containing strains were resistant to cotrimoxazole, and some strains were resistant to oxyminocephalosporins (10 isolates were presumably AmpC hyperproducers, and 2 isolates presented a phenotype compatible with extended-spectrum β-lactamase production). The LAP-1 enzyme was detected in all except one isolate (that with REP-PCR pattern B). The association of qnrS1 and blaLAP-1 already has been described (27). Twenty-one of the 22 E. cloacae isolates with qnrS1 were resistant to ticarcillin, of which 13 isolates were susceptible to ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, a phenotype compatible with the presence of this narrow-spectrum class A β-lactamase (26). Resistance to ticarcillin-clavulanate in the remaining nine isolates should be related to other unexplored mechanisms.

The fact that qnrS1 has been found in several clonally unrelated isolates of E. cloacae is epidemiologically relevant and indicates the potential for the spreading of this gene. Although preliminary information suggests that the plasmid containing qnrS1 in our isolates has disseminated to different E. cloacae strains, it also would be possible that the plasmid was acquired by the different strains from another organism. Two plasmids containing qnrS1, pTPqnrS-1a (10 kb) and pK245 (98 kb), have been completely sequenced (5, 15). The first one presents a region highly homologous to ColE plasmid pEC278 (from E. coli [accession no. AY589571]) and to the qnrS1-containing plasmid pINF5 (from Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis) (14). The region containing qnrS1 in plasmid pK245 is >99% identical to those of plasmids pAH0376 from S. flexneri (6) and pINF5; pK245 also contains genes coding for SHV-2, for resistance to aminoglycosides (aacC2, strA, and strB), chloramphenicol (catA2), sulfonamides (sul2), tetracycline (tetD), and trimethoprim (dfrA14, within a type I integron), as well as multiple insertion sequence elements that may facilitate the dissemination of these resistance determinants. Many of our E. cloacae isolates with qnrS1 contain type 1 integrons, but in the previously characterized S. flexneri strain containing qnrS1 (7), this gene was not contained in a type 1 integron but was in proximity to a Tn3-like structure downstream of complete or truncated ISEcl2 (26). Additional studies are planned to characterize the involved plasmid(s) and to define the genetic background of qnrS1 in our isolates.

It also seems relevant to us that three isolates containing qnrS1 came from nonhospitalized patients. At this moment it is not possible to determine if these organisms had originated in the hospital and disseminated into the community or whether they came from the community and were imported into the hospital. In any case, this finding reinforces the idea of the global relationship among different compartments of the health care system and clearly indicates a need for additional studies looking for potential niches of bacteria containing PMQR genes.

Acknowledgments

pBC-H2.6, which was deposited by M. Hata, was purchased from the DNA Bank, RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan), with the support of the National Bio-Resources Project of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (MEXT).

We thank George A. Jacoby, Patrice Nordmann, Luisa Peixe, and Marc Gallimand for providing control strains.

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (projects PI050690 to L.M.M. and PI060580 to A.P.), the Consejería de Innovación Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía, Spain (P07-CTS-02908), and the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases, Spain (REIPI RD06/0008).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barton, B. M., G. P. Harding, and A. J. Zuccarelli. 1995. A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 226235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caddick, J. M., M. Lindgren, M. A. Webber, P. Kotilainen, A. Siitonen, A. J. Hakanen, and L. J. V. Piddock. 2008. Mechanisms of resistance in non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica exhibiting a novel quinolone resistance phenotype, abstr. P-1536. Abstr. 18th Eur. Cong. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., Barcelona, Spain.

- 3.Cano, M. E., J. Calvo, J. Agüero, J. M. Rodríguez-Martínez, A. Pascual, and L. Martínez-Martínez. 2007. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance among enterobacteria with reduced susceptibility or resistant to ciprofloxacin but susceptible to nalidixic acid. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, Chicago, IL.

- 4.Cavaco, L. M., H. Hasman, S. Xia, and F. M. Aarestrup. 2009. qnrD, a novel gene conferring transferable quinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky and Bovismorbificans strains of human origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53603-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Y. T., H. Y. Shu, L. H. Li, T. L. Liao, K. M. Wu, Y. R. Shiau, J. J. Yan, I. J. Su, S. F. Tsai, and T. L. Lauderdale. 2006. Complete nucleotide sequence of pK245, a 98-kilobase plasmid conferring quinolone resistance and extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase activity in a clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 503861-3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakanen, A. J., M. Lindgren, P. Huovinen, J. Jalava, A. Siitonen, and P. Kotilainen. 2005. New quinolone resistance phenomenon in Salmonella enterica: nalidixic acid-susceptible isolates with reduced fluoroquinolone susceptibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435775-5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hata, M., M. Suzuki, Matsumoto, M. Takahashi, K. Sato, S. Ibe, and K. Sakae. 2005. Cloning of a novel gene for quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2b. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49801-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooper, D. C. 2001. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7337-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacoby, G., V. Cattoir, D. Hooper, L. Martínez-Martínez, P. Nordmann, A. Pascual, L. Poirel, and M. Wang. 2008. qnr gene nomenclature. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 522297-2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacoby, G. A., N. Chow, and K. B. Waites. 2003. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47559-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby, G. A., K. E. Walsh, D. M. Mills, V. J. Walker, H. Oh, A. Robicsek, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. qnrB, another plasmid-mediated gene for quinolone resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 501178-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jun, J., Y. Kwak, S. Kim J. Lee, S. Choi, J. Jeong, Y. Kim, and J. Woo. 2005. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae from Korea, abstr. C2-787. Abstr. 45th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Washington, DC.

- 13.Karisik, E., M. J. Ellington, R. Pike, R. E. Warren, D. M. Livermore, and N. Woodford. 2006. Wide occurrence of the fluoroquinolone-modifying acetyltransferase gene aac(6′)-Ib-cr in CTX-M-positive Escherichia coli from the United Kingdom. 2513. Abstr. 45th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Washington, DC.

- 14.Kehrenberg, C., S. Friederichs, A. de Jong, G. B. Michael, and S. Schwarz. 2006. Identification of the plasmid-borne quinolone resistance gene qnrS in Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 5818-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kehrenberg, C., K. L. Hopkins, E. J. Threlfall, and S. Schwarz. 2007. Complete nucleotide sequence of a small qnrS1-carrying plasmid from Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica Typhimurium DT193. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60903-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu, X., X. Ma, and R. Yu. 2007. Study of qnrB among Cephalosporin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae species in West China. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., Chicago, IL.

- 17.Machado, E., T. M. Coque, R. Cantón, F. Baquero, J. C. Sousa, L. Peixe, et al. 2006. Dissemination in Portugal of CTX-M-15-, OXA-1-, and TEM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains containing the aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene, which encodes an aminoglycoside- and fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 503220-3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-Martínez, L., M. E. Cano, J. M. Rodríguez-Martínez, J. Calvo, and A. Pascual. 2008. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 6685-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, I. García, J. Tran, and G. A. Jacoby. 2003. Interaction of plasmid and host quinolone resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 511037-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Martínez, L. A. Pascual, and G. A. Jacoby. 1998. Quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid. Lancet 351797-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray, A., H. Mather, J. E. Coia, and D. J. Brown. 2008. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in nalidixic-acid-susceptible strains of Salmonella enterica isolated in Scotland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 621153-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paauw, A, A. C. Fluit, J. Verhoef, and M. A. Leverstein-van Hall. 2006. Enterobacter cloacae outbreak and emergence of quinolone resistance gene in Dutch hospital. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12807-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park, C. H., A. Robicsek, G. A. Jacoby, D. Sahm, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. Prevalence in the United States of aac(6′)-Ib-cr encoding a ciprofloxacin-modifying enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 503953-3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paterson, D. L. 2006. Resistance in gram-negative bacteria: enterobacteriaceae. Am. J. Med. 119(Suppl. 1)S20-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Périchon, B., P. Courvalin, and M. Galimand. 2007. Transferable resistance to aminoglycosides by methylation of G1405 in 16S rRNA and to hydrophilic fluoroquinolones by QepA-mediated efflux in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 512464-2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poirel, L., V. Cattoir, A. Soares, C. J. Soussy, and P. Nordmann. 2007. Novel Ambler class A beta-lactamase LAP-1 and its association with the plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant QnrS1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51631-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel, L., C. Leviandier, and P. Nordmann. 2006. Prevalence and genetic analysis of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants QnrA and QnrS in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from a French university hospital. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 503992-3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirel, L., J. D. Pitout, L. Calvo, J. M. Rodriguez-Martinez, D. Church, and P. Nordmann. 2006. In vivo selection of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli isolates expressing plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance and expanded-spectrum beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 501525-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robicsek, A., G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6629-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robicsek, A., D. F. Sahm, J. Strahilevitz, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2005. Broader distribution of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 493001-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robicsek, A., J. Strahilevitz, G. A. Jacoby, M. Macielag, D. Abbanat, C. H. Park, K. Bush, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat. Med. 1283-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robicsek, A., J. Strahilevitz, D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2006. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 502872-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz, J. 2003. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones: target alterations, decreased accumulation and DNA gyrase protection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 511109-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabaté, M., F. Navarro, E. Miró, S. Campoy, B. Mirelis, J. Barbé, and G. Prats. 2002. Novel complex sul1-type integron in Escherichia coli carrying blaCTX-M-9. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 462656-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strahilevitz, J., D. Engelstein, A. Adler, V. Temper, A. E. Moses, C. Block, and A. Robicsek. 2007. Changes in qnr prevalence and fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp. collected from 1990 to 2005. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 513001-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 332233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toleman, M. A., P. M. Bennett, and T. R. Walsh. 2006. ISCR elements: novel gene-capturing systems of the 21st century? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70296-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran, J. H., G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2005. Interaction of the plasmid-encoded quinolone resistance protein Qnr with Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49118-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tran, J. H., and G. A. Jacoby. 2002. Mechanism of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 995638-5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vila, J., M. A. Marcos, and M. T. Jiménez de Anta. 1996. A comparative study of different PCR-based DNA fingerprinting techniques for typing of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. J. Med. Microbiol. 44482-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, P. Goñi, M. A Marcos, and M. T. Jiménez de Anta. 1995. Mutation in the gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 391201-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, C. X., P. Q. Cai, Y. Guo, Z. M. Huang, and Z. H. Mi. 2006. Emerging plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance associated with the qnrA gene in Enterobacter cloacae clinical isolates in China. J. Hosp. Infect. 63349-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, M., D. F. Sahm, G. A. Jacoby, and D. C. Hooper. 2004. Emerging plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance associated with the qnr gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 481295-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, M. H., X. Xu, S. Wu, D. Zhu, and M. Wang. 2008. A new plasmid-mediated gene for quinolone resistance, qnrC, abstr. O207. Abstr. 18th Eur. Cong. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., Barcelona, Spain.