Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis is an opportunistic pathogen that causes numerous infectious diseases in humans and is a major agent of nosocomial infections. In this work, we showed that the recently identified transcriptional regulator Ers (PrfA like), known to be involved in the cellular metabolism and the virulence of E. faecalis, acts as a repressor of ace, which encodes a collagen-binding protein. We characterized the promoter region of ace, and transcriptional analysis by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and mobility shift protein-DNA binding assays revealed that Ers directly regulates the expression of ace. Transcription of ace appeared to be induced by the presence of bile salts, probably via the deregulation of ers. Moreover, with an ace deletion mutant and the complemented strain and by using an insect (Galleria mellonella) virulence model, as well as in vivo-in vitro murine macrophage models, we demonstrated for the first time that Ace can be considered a virulence factor for E. faecalis. Furthermore, animal experiments revealed that Ace is also involved in urinary tract infection by E. faecalis.

Enterococcus faecalis is a natural member of the intestinal microflora of warm-blooded animals and humans. However, E. faecalis remains an important opportunistic pathogen and represents one of the principal causes of nosocomial infections in the United States and Europe (33; for a review, see reference 20). Especially for immunocompromised patients, these infections include endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, peritonitis, visceral abscesses, urinary infections, and septicemia (13). About a dozen putative virulence factors have been identified in E. faecalis, but mechanisms of virulence remain not fully understood. These factors are involved in different steps of the infection process, such as attachment to host cells or extracellular matrix (ECM), macrophage resistance, tissue damage, and immune system evasion (20).

For extracellular pathogens such as E. faecalis or Staphylococcus aureus, components of ECM or serum (i.e., collagen, fibronectin, and fibrinogen) are preferred targets for adhesion. During important steps of the infectious process, they interact with bacterial surface-exposed molecules, which include microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs). Ace, an adhesin that binds collagen (types I and IV) and laminin and belongs to the MSCRAMM family, was identified in E. faecalis by sequence homology with the virulence factor Cna, a well-characterized MSCRAMM in S. aureus (16, 26). Synthesis of the A domain of Ace by S. aureus increased its arthritogenic potential to a level similar to that of S. aureus expressing Cna (34). Study of the sequence diversity of ace among several strains of E. faecalis has revealed an important variation in the number of repeated sequences (17). However, the role played by these regions has not yet been elucidated. The expression of Ace is significantly induced by high temperature (culture at 46°C) and in vivo by the presence of serum or ECM components (8, 14, 15, 28). These results highlight the existence of different in vivo mechanisms of regulation, according to the environmental conditions encountered by E. faecalis during infection. Moreover, antibodies directed against Ace have been almost always found in serum from patients with endocarditis due to E. faecalis, reinforcing the idea of significant expression of this protein in vivo (17). In one study, mice vaccinated with the collagen-binding part of Cna of S. aureus were partially protected from septic death (19). Moreover, mice immunized with recombinant protein Cna-FnBP (fibronectin-binding protein) survived longer following S. aureus infection than nonimmunized mice did (36). Very recently, the collagen adhesin Acm of E. faecium was shown to contribute to pathogenesis. Since anti-Acm antibodies reduced E. faecium collagen adherence, the authors propose that Acm may be a potential immunotarget (18). Despite the clear role of Ace in adhesion to ECM and to human epithelial and endothelial cells, to our knowledge, this protein has never been directly implicated in animal survival (8).

Recently, Ers (for enterococcal regulator of survival) was identified in E. faecalis by sequence homology with PrfA, the major regulator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes (6, 24). Ers plays an important role in the survival of oxidative stress and in the survival of the bacterium in mouse macrophages, as well as in the virulence of E. faecalis (6, 25). Investigation of members of the Ers regulon showed that this regulator directly interacts with the promoter regions of ers, ef0082, arcABC, and ef1459 (25). Sequence comparison of these regions allowed the characterization of a putative consensus sequence (AACATTTGTTG) that shows similarity to the PrfA box of Listeria (TTAACANNTGTTAA) (25).

In the present study, we identified the regulator of ace and demonstrated for the first time that Ace is a virulence factor for E. faecalis. In addition, we found that the presence of bile salts is another in vivo stress able to increase the level of ace mRNA, likely due to the deregulation of ers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis JH2-2 (9, 35) and its derivatives were grown at 37°C in M17 medium (30) supplemented with 0.5% glucose (GM17) or brain heart infusion, and when required, erythromycin (50 or 150 μg/ml) was added. Escherichia coli strains were cultured while shaking at 37°C in LB medium (27) with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), or erythromycin (150 μg/ml) when required. Bile salt stress was imposed by incubation of an exponential growth phase culture (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.3) with 0.08% (wt/vol) bile salts for 30 min.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | ||

| JH2-2 | Fusr Rifr; plasmid-free wild-type strain | 9, 35 |

| Δers | JH2-2 isogenic Δers mutant | 25 |

| Δace | JH2-2 isogenic Δace mutant | This study |

| Complemented Δace | ace insertion in the JH2-2 Δace mutant | This study |

| JH2-2/p3535ers | Strain JH2-2 harboring plasmid p3535ers | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15] Tn10 (Tetr) | Stratagene |

| M15/pQE30ersHTH | Strain harboring pQE30ersHTH | This study |

| L. lactis IL 1403 | 4 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMAD | oripE194ts Emr AmprbgaB | 1 |

| pMSP3535 | 3 | |

| pGEM-T easy | f1 ori lacZ Ampr | Promega |

| pMad-Δace | Construction for the ace deletion mutant | This study |

| pMad-ace | Construction for the complemented ace mutant strain | This study |

| pMSP3535ers | ers cloned into overexpression vector p3535 | This study |

| pGEM-T-Pace | Promoter of ace cloned into pGEM-T | This study |

General molecular methods.

PCRs were done with a reaction volume of 25 μl and chromosomal DNA of E. faecalis JH2-2 by using PCR Master Mix (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The primers used for this work are listed in Table 2. PCR products and plasmids were purified with the NucleoSpin Plasmid kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Classical enzymes (restriction endonucleases, alkaline phosphatase, and T4 DNA ligase) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ), Promega (Madison, WI), and Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. Genomic DNA extraction and other standard techniques were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (27).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Locusa or primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a

|

Use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| ers | CGCGGATCCATAATAGATAATTGAGG | TTGCTGCATCTTTTTCATGG | RT-qPCR |

| ef0082 | TTGACGTCAGCACCTTCTTC | CGTAGCGTTCACCTTTGACA | RT-qPCR |

| ef0049 | CAGCTTTTCCGACACGTCTT | TTCCCCCACGTACTTTAGCA | RT-qPCR |

| ef0782 | TTAGAGCGCGCAGTGAATC | ATGGCCGATCTGCTTCTAAA | RT-qPCR |

| ace | ATGAAGGAAGCCCACAGTTG | GTTGTGCCTGTTTTGGGAAG | RT-qPCR |

| kat | GCTGTTTGGGATTTTTGGTC | CATGCATATGACGGAACGAC | RT-qPCR |

| ef1656 | TTTATTTGTCACCCAACCAACA | CAATTGAAACGGTTGATCAGAA | RT-qPCR |

| ef1664 | TGGCGACCTAATTACCTTGG | CGTTTGCATCGTACGTGAGT | RT-qPCR |

| ef1816 | CGTCAAGACGATACCCGATT | TTTCCATGTTGTGCAGGAAG | RT-qPCR |

| ef2185 | GCGATTGCTCCAACTGAATC | GCCGTCCGTAATAAAAAGCA | RT-qPCR |

| ef3146 | CCAGAATTCTCAATTCCTCGTT | CAAATTTTTGTACACCGACAGG | RT-qPCR |

| aceRace1 | ATTCCAACTAGTGCGTCTGG | 5′RACE PCR | |

| aceRace2 | TTGAGGTCATCTCTCCTTG | 5′RACE PCR | |

| aceRace3 | TCAATTCGGCGCCAAACGAA | 5′RACE PCR | |

| Prom-ace | TCATTCTTTTCCTCCTTATCT | CCGCAATTGGTAGAATCATTA | Cloning in pGEM-T |

| Prom-ers | TAAGTTTGGTTCTGTCATTA | CGACTCGAAAGGAATGTTCA | Cloning in pGEM-T |

| aceDC-Ub | CCGGAATTCAGCTCAACTATGCCTGTCGA | CGCGGATCCGTCATTCCAACTAGTGCGTC | Cloning in pMAD |

| aceDC-Db | CGCGGATCCCAGCCATCCACAGAAACAAC | GAAGATCTTTCCTCTGCCATTAACGCGT | Cloning in pMAD |

| p3535ers | CGCGGATCCATAATAGATAATTGAGGAGTTA | CGCGCGCTGCAGTTAAACAATAATGTTATCTCTAATC | Cloning in pMSP35535 |

| pQE30-ersHTH | GCGGATCCAAAAAGATGCAGCAAATGTTGAT | CGCGCGCTGCAGTTAAACAATAATGTTATCTCTAATC | Cloning in pQE30 |

| mad1F | TCTAGCTAATGTTACGTTACAC | Cloning verification | |

| mad2R | TCATAATGGGGAAGGCCATC | Cloning verification | |

| Pu | GTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | Cloning verification | |

| Pr | CACAGGAAACAGATATGACC | Cloning verification | |

From the annotated sequence available at http://www.tigr.org.

Primers used to clone upstream (U) and downstream (D) sequences of ace in order to construct a deletion mutant and complemented strain by a double-crossover (DC) event.

Construction of Δace mutant and complemented strains.

For the construction of ace deletion mutant (Δace) and complemented strains by double-crossover assays, we used the method previously described (11). Briefly, a DNA fragment (obtained with chromosomal DNA of E. faecalis JH2-2 as the template) containing ligated upstream (1,091-bp) and downstream (1,080-bp) sequences of the ace gene (for the mutant) or including the entire ace gene (3,636 bp) (for the complemented strain) was cloned into plasmid pMAD (1) (Table 1), and 1 μg of the recombinant plasmid was used to transform competent cells. Candidate clones resulting from a double-crossover event were isolated on GM17 agar with or without erythromycin. Antibiotic-susceptible clones were analyzed by PCR for the presence of a deletion-containing or intact ace gene. Seventy percent of the ace gene was deleted in the mutant strain, starting 257 bp after the ATG codon and stopping 279 bp before the TAA codon and creating frameshifts and stop codons in the remaining sequence. This has been verified by sequencing.

Construction of strain JH2-2/p3535ers overproducing Ers.

In order to overproduce the regulator Ers, we cloned the corresponding gene into plasmid pMSP3535 (3). The entire gene was amplified by PCR (Table 2) and then inserted just downstream of the nisin-inducible promoter present in the plasmid. The resulting construction was electroporated into E. faecalis JH2-2, creating strain JH2-2/p3535ers. By Western blotting with an anti-Ers antibody, we found that the addition of 0.5 μg nisin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) per ml of culture at an OD600 of 0.2 for 1 h corresponded to the optimal conditions that allowed the overproduction of Ers.

Protein extraction and Western blotting.

Cells were from E. faecalis strains cultivated as follows: exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.5) at 37°C, exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.5) at 46°C, and exponential growth phase (OD600 of 0.3) at 37°C, followed by 30 min in the presence of bile salts (0.08%, wt/vol). For strain JH2-2/p3535ers, overproduction of Ers was performed as described above. Ten milliliters of bacterial culture was harvested by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in 125 μl of 0.25 M Tris buffer (pH 7.5) and broken by the addition of glass beads (0.1 and 0.25 mm in diameter) and vortexing for 4 min. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to another tube, and the protein concentration was determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bradford method; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA). Sodium dodecyl sulfate Laemmli buffer was added before loading (40 μg). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane that was stained with Coomassie blue in order to verify that the same quantity of protein was present in all of the lanes. Blocking, incubation with antiserum against His-tagged Ers, and enhanced-chemiluminescence detection (ECL detection kit; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) were carried out as previously described (25).

Reverse transcription (RT)-quantitative PCR (qPCR) and mapping of the transcriptional start site.

For each condition (described above) and strain, three samples of total RNA were isolated with the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Specific primers designed to produce amplicons of equivalent length (100 bp) were designed with the V583 genome sequence and the Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi) and are listed in Table 2. Two micrograms of RNA was reverse transcribed with random hexamer primers and Omniscript enzyme (Qiagen).

Quantification of 23S rRNA gene or gyrA (encodes gyrase) levels was used as an internal control. Amplification (carried out with 5 μl of a 1/100 dilution of cDNA), detection (with automatic calculation of the threshold value), and real-time analysis were performed twice and in duplicate with three different cDNA samples by using the Bio-Rad iCycler iQ detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The value used for the comparison of gene expression levels was the number of PCR cycles required to reach the threshold cycle (CT). To relate the CT value back to the abundance of an mRNA species, the CT was converted to the n-fold difference by comparing the mRNA abundance in the JH2-2 wild-type strain to that obtained with the Δers mutant strain or under different culture conditions. The n-fold difference was calculated by the formula n = 2−x when CT mutant < CT JH2-2 and n = −2x when CT mutant > CT JH2-2 with x = CT mutant − CT JH2-2. Values greater than 1 reflect a relative increase in mRNA abundance compared to the wild type, and negative values reflect a relative decrease. Statistical comparison of means was performed with Student's t test with values of ΔCT (CT gene/CT 23S rRNA gene). A relative change of at least 2 and a P value of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

With RNA extracted from the wild-type strain, the transcriptional start point of ace was determined with the rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) 5′/3′ kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Overproduction and purification of ErsHTH.

The C-terminal part (the last 91 amino acid residues) of the Ers protein (comprising 217 residues), including the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif (DNA-binding domain), was overproduced and purified as a recombinant protein with a His6 tag (His6-ErsHTH) by using the pQE30 expression vector (QIAexpressionist kit, Qiagen).

Gel mobility shift assay.

A DNA fragment of about 400 bp including the promoter region of ace of E. faecalis JH2-2 was inserted into the pGEM-T vector (Promega) and cloned into E. coli XLI-Blue (nucleotide −340 to nucleotide +59 relative to the translational start point of ace). This was then amplified by PCR with D4-labeled primers Pu and Pr (from the plasmid sequence) (Table 2), generating a 450-bp DNA fragment. The labeled DNA (0.1 μg) was incubated with purified ErsHTH (1 μg) in interaction buffer (Tris HCl at 40 mM [pH 7.5], bovine serum albumin at 200 μg/ml, CaCl2 at 2 mM, dithiothreitol at 2 mM, poly(dI-dC) at 20 μg/ml) at room temperature for 30 min in the presence of 0.1 μg of crude extract from the Δers mutant. Samples (0.5 μg) of unlabeled competitor and noncompetitor DNAs (internal fragment of the ef1843 gene) were used for specificity experiments. After electrophoresis, gels were visualized with the ProXpress scanner (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Infection and survival experiments.

The in vivo-in vitro model of survival within murine macrophages was carried out as described elsewhere (5, 32).

Infection of Galleria mellonella larvae with E. faecalis was carried as previously described by Park et al. (21). Briefly, with a syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA), larvae (about 0.3 g and 3 cm in length) were infected subcutaneously with washed E. faecalis strains from an overnight culture in M17 (6 × 106 ± 0.6 × 106 CFU per larva) in 10 μl of sterile saline buffer with a sterilized microsyringe and incubated at 37°C. For one test, 20 insects were used and the experiments were repeated at least three times. Lactococcus lactis IL1403 was also tested under the same conditions as a nonvirulent control (4). Larval killing was then monitored at 16, 20, and 24 h postinfection.

For the mouse experiments, female BALB/c mice, 20 to 25 g (Harlan Italy S.r.l), were housed in filter-top cages with free access to food and water and maintained in the Catholic University Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine with the approval of an institutional animal use committee. In order to assess the virulence of the Δace mutant strain with respect to that of the JH2-2 wild-type strain, two different mouse models were used. In the peritonitis model, experiments were performed according to La Carbona et al. (11) without modifications.

In the urinary tract infection (UTI) model, we followed the protocol described by Singh et al. (29). Briefly, each bacterial strain was grown in 10 ml of brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 40% heat-inactivated horse serum for 10 h at 37°C with shaking. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 10 ml of sterile saline solution, and then adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 107/ml. First, groups of five isoflurane-anesthetized mice per bacterial inoculum (102 to 106 CFU) were infected via intraurethral catheterization (polyethylene catheter, ∼4 cm long; outside diameter, 0.61 mm; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) with 200 μl of each strain suspension. Additionally, groups of 10 mice were infected with a sole inoculum of 104 CFU. Mice were sacrificed 48 h after transurethral challenge, and bladders and kidney pairs were excised, weighed, and homogenized in 1 and 5 ml of saline, respectively, with a Stomacher 80 device (PBI International, Italy) for 120 s at high speed. Serial homogenate dilutions were plated onto Enterococcus selective agar (Fluka Analytical, Switzerland) for CFU determination. For each strain, the 50% infective dose was determined as previously described (23). The bacterial detection limits were 50 CFU/ml for kidneys and 10 CFU/ml for bladder homogenates. Differences between the total numbers of infected kidney pairs or bladders, obtained by combining all of the inoculum (102 to 106 CFU) groups, were analyzed by Fisher's exact test, whereas CFU counts, obtained from the 104-CFU inoculum groups, were analyzed by unpaired t test.

All experiments were performed at least three times, and for all comparisons, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Identification of promoters containing a putative Ers box.

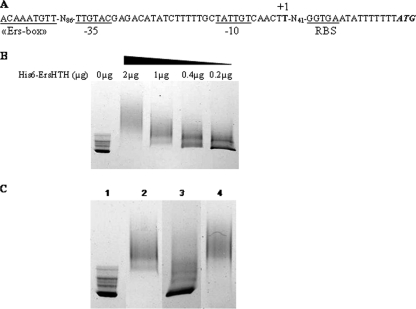

As described in our previous report, we characterized a putative Ers box consensus sequence (AACATTTGTTG) (25). We then screened the annotated sequence of E. faecalis V583 (22) for the presence of similar sequences by the following criteria: location in a putative promoter region and one, two, or three mismatches that did not affect the small inverted repeat sequence (AACAnnTGTT). Eight new loci were found and suspected to be under Ers regulation (Table 3). RT-qPCRs were performed in order to compare the expression of these genes in the Δers mutant and JH2-2 strains. As shown in Table 3, it appeared that ef1099, which encodes Ace, a well-characterized collagen-binding protein (26), was the sole gene from this list showing a significantly higher transcription level (+5.11 with the 23S rRNA gene as a reference, +7.4 with gyrA as a reference) in the Δers mutant strain than in JH2-2. To confirm the role of Ers in the expression of ace, we used strain JH2-2/p3535ers, which overexpresses Ers (see Fig. 2A, last lane). The ace mRNA transcript level was significantly reduced (−2.3-fold, P = 0.01) when a greater amount of Ers was present (see Fig. 2B). These results strongly suggested that Ers acts as a negative transcriptional regulator of ace. Microarray transcriptome analysis of the ers mutant and JH2-2p3535ers strains compared to the wild type confirmed that of the eight candidates, only the transcription of ace was modified in both backgrounds (upregulated in the ers mutant and less expressed when Ers was overproduced). In addition, no adjacent gene loci harboring a putative Ers box appeared to be under Ers regulation (data not shown). To characterize the ace promoter region more precisely, we identified the transcription start site (+1) by 5′RACE PCR experiments. +1 is located 56 bp upstream of the ATG translational start codon. From this finding, putative −10 (TATTGT) and −35 (TTGTAC) regions were identified 5 and 28 bp upstream of +1, respectively (Fig. 1A).

TABLE 3.

Identification and expression of genes harboring a putative Ers box in the promoter region

| ORFd | Gene name | Putative Ers box | Expressiona (P value) with reference to that of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23S rRNA gene | gyrA | |||

| ef0049 | AACAAATGTTC-N75-ATG | NDb | ND | |

| ef0782 | AACAAATGTTG-N272-ATG | +1.01 | +1.1 | |

| ef1099 | ace | AACAAATGTTA-N176-ATG | +5.11 (0.02) | +7.4 (0.016) |

| ef1656 | AACATATGTTA-N77-ATG | −1.17 | −1.72 | |

| ef1664 | AACAATTGTTA-N132-ATG | +1.12 | −1.01 | |

| ef1816 | AACAAATGTTT-N81-ATG | +1.36 | +1.27 | |

| ef2185 | AACATATGTTT-N129-ATG | —c | — | |

| ef3146 | AACAATTGTTT-N424-ATG | +1.99 | +2.4 (>0.05) | |

Shown is the level of activation or repression in the Δers mutant compared to the wild type determined by RT-qPCR. Significant values are in bold (value > 2 and P < 0.05).

ND, no detectable expression.

—, Absence of the locus in the JH2-2 genome.

ORF, open reading frame.

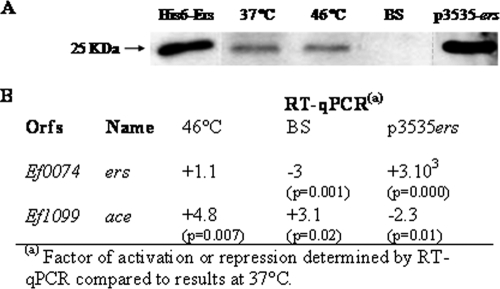

FIG. 2.

Expression of ers and ace determined by Western blot or RT-qPCR analysis. (A) Western blot analysis (with antiserum against His-tagged Ers) of E. faecalis protein extracts (40 μg) from strain JH2-2 grown at 37°C (lane 2), at 46°C (lane 3), or in the presence of bile salts (lane 4) and from strain JH2-2/p3535ers (lane 5). A 0.1-μg sample of purified His6-Ers protein was loaded into lane 1. (B) RT-qPCRs experiments with the ers and ace genes and primers described in Table 2. RNAs were extracted from cells cultured under the same conditions used for protein extracts. Values that are significantly different are >2 (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

(A) Sequence of the ace promoter region. Potential −35 and −10 region and ribosome binding site (RBS) sequences are underlined. The transcriptional start site (+1) is in boldface, and the Ers box is boxed. (B) EMSA with the promoter region of the ace gene and different concentrations (2 to 0.2 μg) of His6-ErsHTH protein. (C) EMSA of His6-ErsHTH binding to the D4-labeled DNA fragment containing the ace regulatory region. Amplifications were performed with D4-Pu and D4-Pr (Table 2). Crude cell extracts prepared from an E. faecalis Δers mutant strain (0.1 μg protein) were added to all of the reaction mixtures. Shown are the labeled ace promoter without protein (lane 1), with His6-ErsHTH (1 μg protein) (lane 2), with His6-ErsHTH and an unlabeled competitor (lane 3), and with His6-ErsHTH and a nonspecific DNA fragment (internal fragment of the ef1843 gene) (lane 4).

ace is directly regulated by Ers.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were carried out in order to determine if the regulation of ace by Ers is direct or indirect. Our first experiments showed that Ers was able to bind to any fragments of DNA, even nonpromoter regions (data not shown). To improve specificity, we decided to test the interaction properties of the ErsHTH domain, which allows the DNA binding of the protein. His6-ErsHTH (containing the last 91 amino acid residues of Ers) was thus used for this experiment. As a control, EMSA conducted with the ers promoter (known to be regulated by Ers) revealed that this truncated peptide acts as a specific DNA-binding protein (data not shown). After several attempts, we did not obtain any interaction in the ace promoter region. We then tried to test the addition of crude extract from the Δers mutant strain in case any cofactor was necessary for this interaction. Under these conditions, we were able to observe a DNA shift in the presence of His6-ErsHTH (Fig. 1B and C). Decreasing the amount of His6-ErsHTH in the binding mixture progressively led to a reduction in the amount of protein-DNA complex and a concomitant increase in the amount of free unbound target DNA (Fig. 1B). Addition of the unlabeled ace promoter fragment suppressed the shift of the labeled promoter, revealing a competition for the binding of His6-ErsHTH (Fig. 1C, lane 3). Moreover, the specificity of this interaction was confirmed by the addition of a nonspecific DNA fragment (Fig. 1C, lane 4). This demonstrated that, in the presence of crude extract, His6-ErsHTH binds in a specific manner to the promoter region of ace.

ers and ace regulation under stress conditions.

Production of Ace has been shown to be modified by environmental conditions (15, 28), but no data were available concerning Ers. We performed Western blot analysis with anti-Ers polyclonal antibodies in order to determine the quantity of Ers under different growth conditions (37°C, 46°C, and 0.08% bile salts) (Fig. 2A). In parallel, we used RT-qPCR to show the relative changes in ers and ace at the transcriptional level (Fig. 2B). It appeared that, in contrast to ace expression (induced 4.8-fold), growth at 46°C did not affect that of ers (Fig. 2A and B). However, when cells were cultivated in the presence of 0.08% bile salts, Ers was undetectable and we measured a decrease in ers expression (threefold reduction) (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, in parallel to this ers repression, induction of ace transcription was observed (+3.1-fold) (Fig. 2B). These combined results were in strong agreement with the negative regulation of ace by Ers but also revealed that bile salts were environmental stimuli recognized by Ers and hence may also affect ace expression.

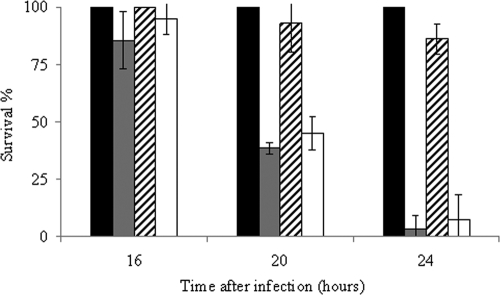

The ace deletion decreased the virulence of E. faecalis.

To determine whether the absence of Ace affects the virulence of E. faecalis, we compared the capabilities of the wild-type and Δace mutant strains to kill G. mellonella larvae in infection experiments. As shown in Fig. 3 the rate of killing was significantly lower in larvae infected with the Δace mutant strain than in those infected with wild-type JH2-2. After 24 h of infection, less than 10% of the wild-type-infected larvae were still alive, whereas 80% of the animals infected with the mutant strain had survived (P = 9 × 10−5) (Fig. 3). The nonpathogenic gram-positive bacterium L. lactis IL1403 was used as a control; all of the larvae infected with this organism survived. Experiments conducted with the complemented Δace mutant strain, in which virulence was restored to the wild-type level, confirmed that the observed phenotype was due to the unique deletion of ace (Fig. 3). Note that the generation time of E. faecalis JH2-2, the Δace mutant, and the complemented Δace mutant strain in GM17 at 37°C was the same (36 min).

FIG. 3.

Effect of ace inactivation on virulence. Percent survival of G. mellonella larvae at 16, 20, and 24 h after infection with L. lactis IL1403 (black bar), E. faecalis JH2-2 (gray bar), the JH2-2 Δace mutant (hatched bar), and the complemented Δace mutant strain (white bar). We used 6 × 106 CFU counted on an agar plate per injection. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the results represent the mean ± standard deviation of live larvae.

The E. faecalis Δace mutant is less phagocytosed and is affected in its ability to survive within macrophages.

Phagocytic cells constitute an important part of the innate immunity against pathogens. To determine whether the Δace mutant strain was impaired at this stage of infection, wild-type JH2-2 and the Δace mutant strain were tested in an in vivo-in vitro macrophage infection model (5). At 8 h postinfection, the number of Δace mutant bacteria recovered was weakly but significantly reduced compared to that of the JH2-2 strain (>1 log10, P < 0.05), suggesting that this mutant was less phagocytosed (Fig. 4). The difference in survival between the Δace mutant and the wild type increased for 72 h after infection (>2.5 log10, P < 0.05), indicating a lower survival rate of the Δace mutant strain in mouse macrophages (Fig. 4). No phenotype has been observed upon exposure to lysozyme (at 15 or 20 mg/ml) or 2 mM H2O2 (data not shown). However, our results suggest that Ace may promote E. faecalis in vivo phagocytosis and that it may be, at least in part, involved in the resistance to deleterious effects encountered inside phagocytic cells.

FIG. 4.

Time course of intracellular survival of E. faecalis JH2-2 (squares) and the Δace mutant (triangles) within murine peritoneal macrophages. The results shown represent the mean number ± the standard deviation of viable intracellular bacteria per 105 macrophages of three independent experiments with three wells.

Ace is involved in UTI.

In the peritonitis model, the JH2-2 and Δace mutant strains of E. faecalis showed similar killing rates (data not shown). Thus, the same strains were also tested by using a recently established UTI model (29) to evaluate if the ace gene is involved in this type of infection. The resulting 50% infective doses showed that the Δace mutant strain requires ∼0.9 log10 more cells to infect 50% of the mice than did the JH2-2 wild-type strain (4.7 × 103 versus 6.9 × 102), thereby suggesting that ace is involved in UTI infection. The percentage of kidneys of mice infected for all of the bacterial inocula used was 84% for the JH2-2 wild-type strain and 60% for the Δace mutant strain (P = 0.02). Also, the cumulative difference between the percentages of bladders infected with the two strains was similar to that between the percentages of kidneys infected (71% for JH2-2 versus 46% for the Δace mutant, P = 0.037). Figure 5 shows the log10 CFU counts recovered from the kidney pairs (n = 15) of mice infected with 104 JH2-2 or Δace cells. The Δace mutant caused a statistically significantly lower (−1.89 log10, P = 0.0371) kidney tissue burden than did the JH2-2 wild-type strain.

FIG. 5.

Infection with 104 cells of wild-type E. faecalis JH2-2 (•) and its isogenic Δace mutant strain (▪). Kidney pair homogenates were obtained from groups of 15 mice that were sacrificed and necropsied 48 h after a transurethral challenge. Results are expressed as log10 CFU per gram of tissue. A value of 0 was assigned to uninfected kidneys. Horizontal bars represent the geometric means.

DISCUSSION

Ers is a transcriptional regulator with similarities to PrfA, the major positive regulator of virulence genes in L. monocytogenes (24). A recent study showed that Ers has a pleiotropic effect, especially on the cellular metabolism (arginine and citrate), as well as in the virulence, of E. faecalis (25). An alignment of the promoter regions recognized by Ers allowed the characterization of a putative consensus sequence (AACATTTGTTG) (25). However, this sequence is sometimes very divergent from the consensus and not systematically located in the DNA fragment that interacts with the regulator. We suspect that the Ers box could play a role in Ers binding, but it seems that its presence should not be a sine qua non condition. A genome survey permitted the identification of several regulatory regions potentially recognized by Ers. Of these, ace was the sole new gene the transcription of which was modified in the Δers mutant strain during the exponential growth phase. This pointed out that the Ers box consensus sequence needs to be more precisely defined, but we cannot exclude the possibility that Ers could regulate the expression of other genes in different growth phases or under stress conditions. Our gel shift assay revealed a direct interaction between ErsHTH and the promoter region of ace, allowing the first identification of a regulator of this gene. Surprisingly, no interaction has been observed between the DNA-binding domain of Ers and the promoter of ace without the addition of crude bacterial cell extract. This suggests that a cellular cofactor is required for the full activity of Ers. Because EMSA experiments have been performed with a truncated protein harboring the HTH DNA-binding motif, this unknown cofactor interacts with this C-terminal part of the regulator. However, in footprinting experiments, Ers has been shown to bind promoter regions of ers, ef0082, ef1459, and arcABC in the absence of cell extract (25). Similar results were obtained with ArcR of S. aureus (another Crp/Fnr regulator) where cyclic AMP is only required for binding to the lctE (encodes lactate dehydrogenase) regulatory region (12). Of the genes in the Ers regulon hitherto identified, ace is the only one negatively regulated by Ers. It may be speculated that additional cellular factors are necessary for repressor activity but not for activator activity. Further identification of Ers-regulated genes will perhaps confirm this hypothesis.

Expression of ace depends on environmental factors such as temperature (46°C) and the presence of collagen, serum, and urine (15, 28). Recent work shows that serum components play an important role as host environmental stimuli to induce the production of ECM protein-binding adhesins (15). Moreover, anti-Ace antibodies have been found in almost every serum sample collected from patients with enterococcal systemic infections, indicating that the biological environment is an efficient inducer of ace (17). We showed that the ace mRNA transcription level was also increased by bile salts, and it is tempting to speculate that this regulation may depend on Ers. Ers acted as a repressor of ace, and downregulation of ers by bile salts could stimulate the transcription of ace. E. faecalis is naturally present in the gastrointestinal tract and has to cope with substances like bile, so we can hypothesize that the induction of ace by bile salts may have an impact on the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by E. faecalis. Other stimuli like 46°C and the presence of collagen or serum did not affect the Ers level (data not shown), so it is likely that, under these conditions, another regulator(s) is involved in the transcriptional regulation of ace.

Larvae of the greater wax moth G. mellonella are now frequently used to evaluate microbial pathogenicity since their innate immune response shows strong structural and functional homology with mammals system (10). This model has been recently used to show that the well-known virulence factor GelE (extracellular gelatinase) of E. faecalis degrades an antimicrobial peptide, destroying the defense system in insect hemolymph (21). As shown in our study, the Δace mutant strain displayed an obvious decrease in virulence. Although Cna (the staphylococcal adhesin, homologous to Ace) is well characterized as a virulence factor (34), this study is the first evidence that Ace is not only involved in the interaction with ECM but is also a virulence factor in E. faecalis. These observations may be correlated with the reduced ability of the Δace mutant to survive within macrophages in comparison to that of the wild type. Similar results have been observed with ElrA and aggregation substance, other surface proteins of E. faecalis involved in the virulence process and intramacrophage survival (2, 7). In addition, Δace mutant strain bacterial counts recovered from macrophages at 8 h postinfection were reduced compared to those of the wild type. This suggests that Ace may also have a role in phagocytosis in vivo and is in agreement with data from Tomita and Ike, who found that bacterial cells of E. faecalis that adhere to ECM proteins also show high adhesion to human cells (bladder carcinoma T24) (31). We showed recently that Ers is involved in the ability of E. faecalis to survive within macrophages and in full virulence in a mouse peritonitis model (6, 25). These results seemed to be in contrast to the deregulation of ace in the ers mutant, since Ers acts as a repressor. So, despite the overexpression of ace, other members of the Ers regulon need to be identified in order to explain why the ers mutant is less virulent.

Like the collagen adhesin Acm of E. faecium or Ebp (endocarditis- and biofilm-associated pilus) of E. faecalis, which is another member of the MSCRAMM family (29), Ace did not seem to be involved in mouse killing in a peritonitis model (data not shown). However, in the murine UTI model, Ebp and Ace are two adhesion-related proteins that allow attachment to and colonization of host renal tissue (29; this study). E. faecalis is a common agent of UTI, and our results confirm that an enterococcal MSCRAMM protein such as Ace may be a valuable drug target against human UTI.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance of Annick Blandin, Isabelle Rincé, Marie-Jeanne Pigny, and Patricia Marquet was greatly appreciated. We thank A. Benachour, S. Gente, J.-M. Laplace, V. Pichereau, A. Rincé, and N. Sauvageot for helpful discussions. We thank Mike Gilmore for providing DNA microarrays. We also thank Christina Nielsen-LeRoux's group for its help in experiments with G. mellonella.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnaud, M., A. Chastanet, and M. Débarbouillé. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 706887-6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinster, S., B. Posteraro, H. Bierne, A. Alberti, S. Makhzami, M. Sanguinetti, and P. Serror. 2007. Enterococcal leucine-rich repeat-containing protein involved in virulence and host inflammatory response. Infect. Immun. 754463-4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan, E. M., T. Bae, M. Kleerebezem, and G. M. Dunny. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gentry-Weeks, C. R., R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. Pikis, M. Estay, and J. M. Keith. 1999. Survival of Enterococcus faecalis in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect. Immun. 672160-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giard, J.-C., E. Riboulet, N. Verneuil, M. Sanguinetti, Y. Auffray, and A. Hartke. 2006. Characterization of Ers, a PrfA-like regulator of Enterococcus faecalis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 46410-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore, M. S., P. S. Coburn, S. R. Nallapareddy, and B. E. Murray. 2002. Enterococcal virulence, p. 301-354. In M. S. Gilmore (ed.), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 8.Hall, A. E., E. L. Gorovits, P. J. Syribeys, P. J. Domanski, B. R. Ames, C. Y. Chang, J. H. Vernachio, J. M. Patti, and J. T. Hutchins. 2007. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing the Enterococcus faecalis collagen-binding MSCRAMM Ace: conditional expression and binding analysis. Microb. Pathog. 4355-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob, A. E., and S. J. Hobbs. 1974. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J. Bacteriol. 117360-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavanagh, K., and E. P. Reeves. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Carbona, S., N. Sauvageot, J.-C. Giard, A. Benachour, B. Posteraro, Y. Auffray, M. Sanguinetti, and A. Hartke. 2007. Comparative study of the physiological roles of three peroxidases (NADH peroxidase, alkyl hydroperoxide reductase and thiol peroxidase) in oxidative stress response, survival inside macrophages and virulence of Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 661148-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makhlin, J., T. Kofman, I. Borovok, C. Kohler, S. Engelmann, G. Cohen, and Y. Aharonowitz. 2007. Staphylococcus aureus ArcR controls expression of the arginine deiminase operon. J. Bacteriol. 1895976-5986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray, B. E. 1990. The life and times of the enterococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 346-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nallapareddy, S. R., and B. E. Murray. 2006. Ligand-signaled upregulation of Enterococcus faecalis ace transcription, a mechanism for modulating host-E. faecalis interaction. Infect. Immun. 744982-4989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nallapareddy, S. R., and B. E. Murray. 2008. Role played by serum, a biological cue, in the adherence of Enterococcus faecalis to extracellular matrix proteins, collagen, fibrinogen, and fibronectin. J. Infect. Dis. 1971728-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nallapareddy, S. R., X. Qin, G. M. Weinstock, M. Hook, and B. E. Murray. 2000. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, Ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect. Immun. 685218-5224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nallapareddy, S. R., K. V. Singh, R. W. Duh, G. M. Weinstock, and B. E. Murray. 2000. Diversity of ace, a gene encoding a microbial surface component recognizing adhesive matrix molecules, from different strains of Enterococcus faecalis and evidence for production of Ace during human infections. Infect. Immun. 685210-5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nallapareddy, S. R., K. V. Singh, and B. E. Murray. 2008. Contribution of the collagen adhesion, Acm, to pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium in experimental endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 764120-4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson, I. M., J. M. Patti, T. Bremell, M. Hook, and A. Tarkowski. 1998. Vaccination with a recombinant fragment of collagen adhesin provides protection against Staphylococcus aureus-mediated septic death. J. Clin. Investig. 1012640-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogier, J. C., and P. Serror. 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: the Enterococcus genus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, S. Y., K. M. Kim, J. H. Lee, S. J. Seo, and I. H. Lee. 2007. Extracellular gelatinase of Enterococcus faecalis destroys a defense system in insect hemolymph and human serum. Infect. Immun. 751861-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulsen, I. T., L. Banerjei, G. S. A. Myers, K. E. Nelson, R. Seshadri, T. D. Read, D. E. Fouts, J. A. Eisen, S. R. Gill, J. F. Heidelberg, H. Tettelin, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, S. Daugherty, R. T. DeBoy, S. Durkin, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, J. Vamathevan, B. Tran, J. Upton, T. Hansen, J. Shetty, H. Khouri, T. Utterback, D. Radune, K. A. Ketchum, B. A. Dougherty, and C. M. Fraser. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 2992071-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent end points. Am. J. Hyg. 27493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riboulet-Bisson, E., A. Le Jeune, A. Benachour, Y. Auffray, A. Hartke, and J.-C. Giard. 2009. Ers a Crp/Fnr-like transcriptional regulator of Enterococcus faecalis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 13171-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riboulet-Bisson, E., M. Sanguinetti, A. Budin-Verneuil, Y. Auffray, A. Hartke, and J.-C. Giard. 2008. Characterization of the Ers regulon of Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Immun. 763064-3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rich, R. L., B. Kreikemeyer, R. T. Owens, S. LaBrenz, S. V. L. Narayana, G. M. Weinstock, B. E. Murray, and M. Höök. 1999. Ace is a collagen-binding MSCRAMM from Enterococcus faecalis. J. Biol. Chem. 27426939-26945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 28.Shepard, B. D., and M. S. Gilmore. 2002. Differential expression of virulence-related genes in Enterococcus faecalis in response to biological cues in serum and urine. Infect. Immun. 704344-4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh, K. V., S. R. Nallapareddy, and B. E. Murray. 2007. Importance of endocarditis and biofilm associated pilus (ebp) locus in the pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecalis ascending urinary tract infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1951671-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terzaghi, B. E., and W. E. Sandine. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl. Microbiol. 29807-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomita, H., and Y. Ike. 2004. Tissue-specific adherent Enterococcus faecalis strains that show highly efficient adhesion to human bladder carcinoma T24 cells also adhere to extracellular matrix proteins. Infect. Immun. 725877-5885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verneuil, N., M. Sanguinetti, Y. Le Breton, B. Posteraro, G. Fadda, Y. Auffray, A. Hartke, and J.-C. Giard. 2004. Effects of Enterococcus faecalis hypR gene encoding a new transcriptional regulator on oxidative stress response and intracellular survival within macrophages. Infect. Immun. 724424-4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wisplinghoff, H., T. Bischoff, S. M. Tallent, H. Seifert, R. P. Wenzel, and M. B. Edmond. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, Y., J. M. Rivas, E. L. Brown, X. Liang, and M. Hook. 2004. Virulence potential of the staphylococcal adhesin CNA in experimental arthritis is determined by its affinity for collagen. J. Infect. Dis. 1892323-2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yagi, Y., and D. B. Clewell. 1980. Recombination-deficient mutant of Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 143966-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, H., Z. Y. Xiong, H. P. Li, Y. L. Zheng, and Y. Q. Jiang. 2006. An immunogenicity study of a newly fusion protein Cna-FnBP vaccinated against Staphylococcus aureus infections in a mice model. Vaccine 244830-4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]