Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae is the predominant pathogen of primary liver abscess. However, our knowledge regarding the molecular basis of how K. pneumoniae causes primary infection in the liver is limited. We established an oral infection model that recapitulated the characteristics of liver abscess and conducted a genetic screen to identify the K. pneumoniae genes required for the development of liver abscess in mice. Twenty-eight mutants with attenuated growth in liver or spleen samples out of 2,880 signature-tagged mutants that produced the wild-type capsule were identified, and genetic loci which were disrupted in these mutants were identified to encode products with roles in cellular metabolism, adhesion, transportation, gene regulation, and unknown functions. We further evaluated the virulence attenuation of these mutants in independent infection experiments and categorized them accordingly into three classes. In particular, the class I and II mutant strains exhibited significantly reduced virulence in mice, and most of these strains were not detected in extraintestinal tissues at 48 h after oral inoculation. Interestingly, the mutated loci of about one-third of the class I and II mutant strains encode proteins with regulatory functions, and the transcript abundances of many other genes identified in the same screen were markedly changed in these regulatory mutant strains, suggesting a requirement for genetic regulatory networks for translocation of K. pneumoniae across the intestinal barrier. Furthermore, our finding that preimmunization with certain class I mutant strains protected mice against challenge with the wild-type strain implied a potential application for these strains in prophylaxis against K. pneumoniae infections.

As a common pathogen for community-acquired and nosocomial infections, Klebsiella pneumoniae is responsible for a wide spectrum of clinical syndromes, including purulent infections, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, bacteremia, septicemia, and meningitis (34). Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is primarily a complication of intra-abdominal or biliary tract infections resulting from mixed infections with aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (28). A single-pathogen-induced form of PLA which is predominantly mediated by primary infection with K. pneumoniae has emerged in recent years (5, 10, 20, 29, 31, 33, 42). Different from the polymicrobial form of PLA, K. pneumoniae-induced liver abscess (KLA) is generically cryptogenic, without underlying hepatobiliary disorders, and is frequently complicated with septic metastatic lesions (5, 18, 25, 32, 42, 45). By virtue of its primary and invasive nature, KLA is considered one of the most severe infections caused by K. pneumoniae (19, 42). Epidemiological investigations have demonstrated that the occurrence of KLA significantly correlates with the prevalence of particular K. pneumoniae strains which carry specific bacterial features, such as the K1 or K2 serotype and the hypermucoviscosity (HV) phenotype (6, 10, 13, 14, 46). Genetic loci that are involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharides and the production of siderophores, including a K1-specific gene for the HV phenotype (magA), a plasmid-borne gene for the HV phenotype (rmpA), a K1-specific gene for iron uptake (the kfu phosphotransferase gene), and three gene clusters encoding the TonB-dependent iron acquisition system (iucABCD-iutA, iroA-iroNDCB, and the Yersinia high-pathogenicity island), have been reported to contribute to the virulence of a K1 KLA-causing strain (13, 17, 26, 47). Despite the well-documented impact of KLA, our knowledge regarding the molecular basis of how K. pneumoniae causes an infection particularly in the liver is rather restricted.

Signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) is a technique that permits screening of comparatively large pools of transpositional mutants in a single animal and has been successfully applied to identify virulence factors of a variety of pathogens (16, 36). While there are three reports for which the STM technique was used to investigate K. pneumoniae genes required for intestinal colonization, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia (24, 27, 41), no in vivo approach has been applied to identify the K. pneumoniae genes necessary for bacterial growth in the liver. In an effort to understand the molecular pathogenesis of KLA, we established an oral infection model that recapitulated the major characteristics of liver abscess and conducted an STM screen to identify the K. pneumoniae mutants which were attenuated in their growth in the liver. Because the role of capsule in bacterial pathogenesis has been well documented, only mutants that produced the wild-type capsule were selected for the STM screen. In this study, we identified 28 KLA-attenuated mutants which had transposon insertions in different genetic loci encoding both novel and previously known bacterial factors. We further evaluated the degree of virulence attenuation for each of these mutants in independent infection experiments and also characterized their roles in the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae. Through this effort, we demonstrated the first use of an in vivo mutagenic screen approach to identify the genetic factors required for K. pneumoniae to cause liver abscess in an oral infection model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

K. pneumoniae CG43, a K2 serotype strain, was clinically isolated from a patient with PLA. This strain was highly virulent to BALB/c mice, with an intraperitoneal 50% lethal dose of 10 CFU (7). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing K. pneumoniae was generated by transformation of pGFPuv-Tc, a tetracycline-resistant derivative of pGFPuv (Clontech).

Oral infection in mice.

Male BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taiwan) at 6 weeks of age and allowed to acclimatize in the animal house of Chung Shan Medical University for 2 weeks before the experiments. Mice were starved of food for 16 h before inoculation. Twenty microliters of bacterial suspension containing 107 CFU of mid-log-phase K. pneumoniae (or GFP-expressing K. pneumoniae) was orally inoculated into mice by using a 21-gauge feeding needle. The mice were sacrificed at indicative time points, and intestine, cecum, colon, blood, liver, spleen, and kidney samples were retrieved. Serial dilutions of the tissue homogenates were cultured to enumerate bacterial counts. For histological examination, livers were fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution and processed for paraffin embedding, and 5-μm-thick sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For detection of K. pneumoniae, the deparaffinized liver sections were hybridized for overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal antibody against K. pneumoniae OmpA at 1:1,000, washed, incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat antibody against rabbit (Chemicon) for 60 min at room temperature, and then examined after being incubated with chromogen-conjugated 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole substrate. All animal experiments were performed according to guidance from the National Laboratory Animal Center, and the protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Construction of an STM library.

The mobilizable suicide vector pBSL180 (1) carrying an ATS Tn10 transposase gene fused to a Ptac promoter, which drastically reduced the hot spot specificity and fully allowed randomness of Tn10 transposon mutagenesis, was used as the backbone. Double-stranded 80-bp DNA signature tags, which were amplified with primers P2 (5′-TACCTACAACCTCAAGCT-3′) and P4 (5′-TACCCATTCTAACCAAGC-3′), with RT1 (a generous gift from D. W. Holden) (16) as the template, were introduced into the KpnI site of pBSL180. Based on the criteria that an efficient amplification and labeling of a unique tag and a lack of cross-hybridization to other tags, 48 uniquely tagged transposons were selected, sequence determined, and then transformed into Escherichia coli S17-1 λ-pir (39) via electroporation. Through 48 independent mating experiments, a total of 3,840 K. pneumoniae mutants were generated. Based on the colony morphology and tag uniqueness, these mutants were arrayed into 80 mutant pools (MPs), each containing 48 uniquely tagged mutants. Mutants that had no defects in producing the wild-type colony morphology were collected in MP01 to -60, while acapsulated mutants or mutants unable to display the HV phenotype (13) were collected in MP61 to -80. Randomness of mini-Tn10 mutagenesis was verified by Southern analysis of 24 randomly selected mutants, with nptII, the kanamycin-resistant gene of mini-Tn10, as a probe. For preparation of 48 unique probes for hybridization, the inner diverse region within the 48 signature tags was individually amplified with p094 (5′-TACCTACAACCTCAAGCT-3′) and p095 (5′-TACCCATTCTAACCAAGC-3′) (16), and the amplified DNA fragments were digested with HindIII, purified, and labeled with fluorescein-dUTP at the 3′ end by using a Gene Images 3′-oligonucleotide-labeling kit (Amersham Biosciences).

STM screen for mutants attenuated in the oral infection model.

Three 8-week-old male BALB/c mice were orally inoculated with 20 μl of bacterial mixtures containing 107 CFU of signature-tagged mutants obtained from a particular MP (approximately 2 × 105 CFU per tagged mutant). At 48 h after oral inoculation, livers and spleens were aseptically retrieved from the infected mice. To reduce bias between individual mice, the tissue homogenates obtained from mice infected with the single MP were combined and cultured with adequate dilutions on LB-kanamycin plates. For each of the recovered pools, at least 3,000 kanamycin-resistant colonies were scraped from the plates, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and normalized for optical density at 600 nm. Bacterial genomic DNA from each pool was extracted and used as a template for amplification of the DNA tags in accordance with PCR conditions described previously (16). The amplified tag mixtures from both the inoculum and the recovered pools were spotted onto 48 separate Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Biosciences), which were then subjected to 48 hybridizations, one with each of the 48 tag-specific, fluorescein-labeled probes. Hybridization and detection were carried out using a CDP-STAR nucleic acid chemiluminescence kit (PerkinElmer). Hybridization signals were visually compared based on the results obtained upon 20 min of exposure to X-film (X-OMat; Kodak). Mutants that showed an eliminated signal in the recovered pool but not in the inoculum were selected and reassembled in new pools for another round of selection. Through selections, the secondary pools yielded 108 mutants which were attenuated for growth in the spleen, 84 mutants which were attenuated for growth in the liver, and 39 mutants which were attenuated for growth in both tissues.

Mapping of transposon insertion sites and DNA sequence analysis.

Mutants that were not recovered from the liver or spleen were selected for Southern hybridization (37) to determine the number of transposition events. Thirty-six mutants which had only one mini-Tn10 hit were identified as KLA attenuated. The DNA sequences flanking the mini-Tn10 insertion site in the 36 mutants were cloned by ligation of PstI- or HindIII-restricted genomic DNA into a correspondingly linearized pUC18 vector. Plasmid DNA that contained various amounts of chromosomal DNA conjunct with the nptII locus of mini-Tn10 was sequenced by Mission Technologies (Taipei, Taiwan) with primers M13-forward and M13-reverse and with primer p136 (5′-CTATCGCCTTCTTGACGAGT-3′), which is located outward relative to the nptII locus. Obtained sequences were used for querying the K. pneumoniae MGH78578 genome database (http://genome.wustl.edu/genome_index.cgi) and the contig database of K. pneumoniae CG43 (H.-L. Peng and S.-F. Tsai, unpublished results) to determine the identities of open reading frames (ORFs) containing mini-Tn10 insertions. Sequence homology was determined by querying the public protein database with the BLAST search program (3) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and the putative functional domains were analyzed with Pfam (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/).

Independent verification of virulence attenuation in KLA mutants.

The degree of virulence attenuation of a single KLA-attenuated mutant was evaluated in independent infection experiments. Each of the virulence-attenuated (VA) strains was grown to mid-log phase in LB, and 20 μl of bacterial suspension (107 CFU) was used to challenge eight of 8-week-old BALB/c mice via the oral route. Small intestine, colon, spleen, liver, and blood samples were aseptically retrieved from three of the infected mice at 48 hours postinfection (hpi). Bacterial concentrations in these mouse tissues were determined by measuring viable counts on LB-kanamycin plates and were represented as numbers of CFU g−1 tissue or CFU ml−1 blood. The survival rate of the remaining five mice, which were infected with a single VA strain, was monitored daily for 2 weeks. Mortality rate and mean number of days to death (MDD) were determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis using Prism4 for Windows (GraphPad); P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. To further examine the virulence attenuation of the class III mutants, a competitive assay was performed as described previously (16). Twenty microliters of bacterial suspension containing equal amounts of the wild type (5 × 106 CFU) and a mutant strain (5 × 106 CFU) was used to orally challenge three of 8-week-old BALB/c mice. At 48 h after inoculation, viable counts of the wild-type and mutant strains in a particular mouse tissue were determined using LB agar with and without kanamycin, respectively. Competitive index (CI) values were calculated as described previously (16).

Detection of kva transcripts with RT-PCR and Northern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated from bacterial cultures of wild-type K. pneumoniae and each of the regulatory kva mutant strains which were grown in regular LB medium for 1 h at 37°C with TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center). Contaminating DNA was eliminated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). Individual total RNA samples were separately subjected to detect the transcript abundance of a particular kva gene by using a SuperScript III one-step reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer, with gene-specific primers. The primer sequences which were used for detecting various kva transcripts were as follows: for galK, ATGAGCGTATTTAACCCC and CACTCCGGATTCACTAAA; for cbl, GTGAACTTCCAGCAGCTG and CTGATAGTCGATTGCGGC; for kva04, ATGGCAATTAAATTAGAAATC and GCCATGATTCACCCCCT; for mrkC, ATGAAGGGATTGCCGAAA and AACTAATTCCCACGTTGC; for kva07, ATGCCAAACCGCCGCGTC and CAGAAAAGTCGGGTTGTG; for kva08, GTGGCGACTATGTACAAA and GAAGTCGACGTTGACGCC; for kva09, ATGCACAAATTTACTAAA and CGCCAGCTCTTCTTTGAA; for kva10, ATGCGGATGTATTTACC and ACCAATCAATCCTTCAGT; for kva11, GTGAGTCAGGCACCCAGT and CTCGCGGGGGGAGGGCTC; for kvgA, ATGAACAGCAGTAACCAC and ACCGATATTGTTATTGTTTG; for kva13, ATGAGTTCTCTGTATCAG and GCTAACGGTTTCTGCTAC; for moaR, ATGTGTCATGTACCATCA and CAGATGCAGCGTACGCTG; for kva15, ATGTTAAAGGGACGATTT and TAATGAACGTTCGGTCTG; for kva17, ATGTCACAAGCAATTCAA and ATCGTGGTGGCCGAAGGT; for kvgS, CTTGAATTAATTAATCAG and TTCCCTTGAGGTAAGCCC; for kva19, ATGACTAATTTTTTGTTCAATATA and GCGTTTGGCGAGCAGTTG; for kva20, GTGGGAAATTCCCGCGGA and ATTGTTACTCTCGCAACT; for kva21, ATGGCAAACCATCGTGGC and ACTTTCACGACTACCATGAC; for kva22, ATGTCGAATACAAGCTGG and TGCGCGGTCGGCATCAGC; for fimC, ATGATGAAGAAAATAATT and CTGCTGGGCGAAATCGCT; for kva24, ATGAACAGCAATAAAGCA and TGCCTGTTTCGCCTCGCT; for kva25, GAGAATCATCCTATTCCC and GATGAGAAAGAGATTGATATG; for kva26, ATGGCAGGCCAGACAGGC and ACGCCACTGGTACAGCAG; for pagO, ATGCGCAGAGTGACGATA and GGAAGTCTCAGTATGCTC; for kva28, ATGACGCGCCGTGCCATC and AAACTCTTCGCTATCCGC; for kva29, GTGACCACCAGCTGCAGC and CAGCGAATTCATAATGTT; for galT, CCAGGAATCCACCCTTAC and GCCCGTTATTAATCACGC; and for kva33, ATGTCCTTAATTAACACC and GATCTTACCAACCAGATC. The reaction was carried out using a total volume of 50 μl at a final concentration of 10 ng/μl total RNA, with 0.2 μM sense and antisense primers. cDNA synthesis and predenaturation were performed using 1 cycle at 50°C for 40 min and 94°C for 2 min. PCR amplification was performed using 25 to 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 52 to 58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 2 min. RNA solution without reverse transcription was used as negative control, and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), which was amplified with primers (5′-GTGGAATATATGACTATC-3′ and 5′-TTTGGAGATGTGGGCAAT-3′), served as an internal control. The gene-specific RT-PCR products were visualized on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide, and the band intensities were quantified using AlphaEase FC software (version 3.2.1; Alpha Innotech). The final signal, obtained by averaging the results from two replicates for each RNA sample, was normalized to that of GAPDH. If the specific signal of a kva gene was not detected from the RNA samples isolated from mid-log-phase LB cultures, total RNA was prepared from stationary-phase LB cultures or mid-log-phase M9-glucose cultures and then subjected to another round of RT-PCR analysis. For Northern detection of the ymdF transcript, 20 μg of total RNA isolated from wild-type K. pneumoniae was glyoxal denatured, separated on a 2% agarose gel, and then transferred onto a BrightStar Plus nylon membrane (Ambion). After UV cross-linking, the membrane was blotted with ULTRAhyb hybridization buffer (Ambion) overnight at 42°C against a gene-specific biotin-labeled riboprobe, which was prepared using a BrightStar psoralen-biotin kit (Ambion). After a stringent wash, signals were detected with a BrightStar BioDetect kit (Ambion).

RESULTS

Oral infection model of KLA.

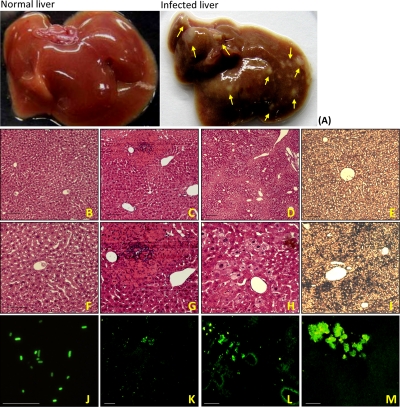

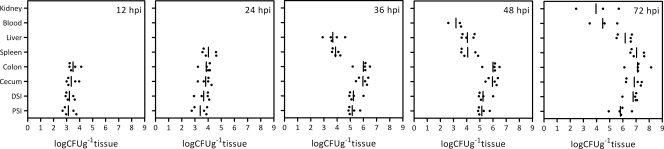

Because the majority of K. pneumoniae infections are preceded by colonization of the patient's intestinal tract (30), we utilized an oral inoculation method to establish a mouse model that could recapitulate the characteristics of liver abscess. A K2 isolate from a KLA patient, K. pneumoniae CG43, was used to orally challenge 8-week-old BALB/c mice with a dose of 1 × 107 CFU, which was close to four times the oral 50% lethal dose of this isolate (2.6 × 106 CFU) (data not shown). Compared to the control group, K. pneumoniae-infected mice developed hepatic microabscess foci (Fig. 1A) concurrent with splenomegaly. The infected liver was infiltrated with numerous inflammatory cells, compared to what was found for the PBS-inoculated control mice (Fig. 1B, C, F, and G). At 72 hpi, the majority of the liver parenchyma became necrotic (Fig. 1D and H), and the K. pneumoniae which was given via the oral route was present in aggregates throughout the liver tissues, as detected by immunostaining with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against K. pneumoniae OmpA (Fig. 1I). Consistently, GFP-expressing K. pneumoniae was also noted to be distributed extensively in the liver after 48 hpi (Fig. 1L and M). To further characterize the progression of liver abscess through the oral infection, bacterial concentrations in different mouse tissues were examined at different time points after inoculation. As shown in Fig. 2, wild-type K. pneumoniae established the intestinal colonization within 12 h after oral inoculation and maintained its persistence throughout the entire course of infection. The bacterial concentration in the cecum and colon remained at a high level of 107 CFU g−1 tissue for 72 h after infection. In the liver, viable K. pneumoniae first appeared at 36 hpi and the bacterial amplification reached 1,000-fold at 72 hpi. The spleen was the first extraintestinal site where large numbers of viable bacteria were located at 24 hpi, and the bacterial burden increased and reached a peak concentration of 107 CFU g−1 tissue at 72 hpi. As indicated by the presence of viable bacteria in the bloodstream and kidneys, approximately 60% of the K. pneumoniae-infected mice developed septic metastases at 48 h following oral administration (Fig. 2), and more than 80% of mice died of septic shock within 1 week after oral infection. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the infected mice exhibited characteristics of bacteremic liver abscess within 2 days following inoculation with K. pneumoniae CG43. In addition, four stages of infection were observed to progress sequentially in our mouse model: intestinal colonization (by 12 hpi), extraintestinal dissemination (between 12 and 24 hpi), hepatic replication (after 36 hpi), and septic metastasis (after 48 hpi).

FIG. 1.

Liver abscess developed in mice with K. pneumoniae infection. Livers were retrieved from BALB/c mice which were orally inoculated with PBS or 107 CFU of wild-type K. pneumoniae. As indicated with arrowheads in panel A, multiple microabscess foci developed in the infected liver by 72 hpi. Compared to what was found for the control liver retrieved from PBS-inoculated mice (B [magnification, ×200] and F [magnification, ×400]), histological examination of the livers of K. pneumoniae-infected mice showed infiltrates of inflammatory cells at 48 hpi (C [magnification, ×200] and G [magnification, ×400]) and necrosis of the liver parenchyma at 72 hpi (D [magnification, ×100 and H [magnification, ×400]). A high concentration of K. pneumoniae was detected in the infected liver at 72 hpi with anti-OmpA rabbit polyclonal sera (I) but not in the control liver (E). GFP-expressing K. pneumoniae (J [magnification, ×1,000]) was also used in the oral infection model for tracing its distribution. Liver cryosections from mice which were infected with 107 CFU of GFP-expressing K. pneumoniae were prepared at 24 (K), 48 (L), or 72 (M) hpi and were examined under a fluorescein isothiocyanate view. Scale bar, 50 μm.

FIG. 2.

Dynamics of wild-type K. pneumoniae growth in different mouse tissues after an oral inoculation. A single dose of 107 CFU of wild-type K. pneumoniae was used to infect BALB/c mice via the oral route. At 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 hpi, samples from various sites in the infected mice, including proximal small intestine (PSI), distal small intestine (DSI), cecum, colon, spleen, liver, blood, and kidney samples, were retrieved and homogenized for measurements of viable bacterial counts, which are expressed as numbers of CFU g−1 tissue or CFU ml−1 blood. Five mice were examined at each time point. The limit of detection was approximately 50 CFU. Samples which yielded no colonies were not plotted. The bars indicate geometric means.

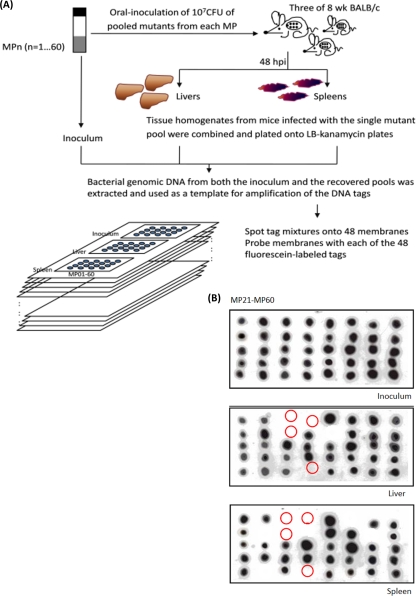

In vivo screening for KLA-attenuated mutants.

To understand the genetic basis of how K. pneumoniae acquired an invasive capacity to cause the liver infection, we conducted an in vivo mutagenic screen using the oral infection model. A total of 3,840 signature-tagged mini-Tn10 mutants of K. pneumoniae CG43 were generated with an STM technique (16). Since the capsule is a well-documented virulence factor, in this study, in order to identify putative virulence factors, we subjected only mutants that were phenotypically similar to the parental strain when grown on M9-glucose minimal medium for in vivo selections. As depicted in Fig. 3A, 2, 880 mutants that produced the wild-type capsule were administered into BALB/c mice in pools of 48 mutants each and were examined for their growth in the liver and spleen at 48 h after oral inoculation. As determined by the lack of any hybridization signal on the output blot (Fig. 3B), 36 mutants which were not recovered from either the liver or the spleen were identified. No multiple hits occurred in these mutants, as confirmed by Southern blotting (data not shown). The nucleotide sequences of the regions flanking the transposon in the 36 KLA-attenuated mutants were determined and used as query sequences to search against the contig database of K. pneumoniae CG43 (H.-L. Peng and S.-F. Tsai, unpublished results) to determine the identities of the disrupted genetic loci. After the sequence analysis, these 36 mutants were found to result from 33 independent transposition events that occurred at one intergenic region, 3 promoter regions, and 29 different ORFs which encoded proteins with diverse functions. Subsequent to removal of sibling strains, 33 independent mutants, each carrying a transposon insertion at a different genetic locus, were later verified individually for their virulence attenuation.

FIG. 3.

STM screen for KLA-attenuated mutants. (A) Schematic diagram showing the STM screen conducted in the oral infection model. A total of 2,880 mutants that produced the wild-type capsule were selected and arrayed in 60 MPs. Three 8-week-old BALB/c mice were orally administered 107 CFU of bacterial culture of a particular MP pool which contains 48 uniquely tagged mutants. Livers and spleens were harvested from these mice, adequate dilutions of tissue homogenates were plated onto kanamycin-LB agar, and at least 3,000 colonies for each output were pooled for the preparation of bacterial genomic DNA. The tag mixtures carried by the mutants in each of the inocula and the output pools were PCR amplified and spotted on 48 replica blots. Each unique fluorescein-labeled tag was subsequently used as a probe for hybridization to those blots, and the mutants whose associated tags were detected in the inocula but not in the pools recovered from either the liver or the spleen were identified as KLA attenuated, indicated by circles in panel B.

Independent verification of virulence attenuation of KLA mutants.

The bacterial virulence of each mutant strain was evaluated in independent infection experiments and competitive infection experiments. Individual bacterial cultures obtained from each of the 33 mutant strains were used separately or mixed with the wild-type strain to challenge BALB/c mice via the oral route with a dose of 107 CFU, and the bacterial concentrations in different mouse tissues at 48 hpi as well as the mortality rates of infected mice observed for 2 weeks after infection were measured. According to these measurements, 28 out of the 33 mutant strains exhibit significant virulence attenuation. These 28 mutant strains were thus designated VA strains, and the ORFs that were inactivated in these strains were named kva (klebsiella virulence-associated) genes (Table 1). The phenotypic characterization of these strains is presented in Table 2. No general growth defects resulted from mutations in these strains. Based on sequence analysis of the flanking region of the inserted transposon, the transposon insertion sites in 22 mutant strains were located either within monocistronic loci or in the last gene of polycistronic operons, whereas the transposon insertion sites in the remaining six mutants were located in front of more than one gene within polycistronic operons. The sequence analysis indicated that the disrupted polycistronic operons in these six mutant strains all contained groups of functionally related genes (Table 1). Therefore, although the mutations in these six mutant strains might cause polar effects, these insertions were nevertheless informative.

TABLE 1.

Genetic loci required for K. pneumoniae in the development of KLA

| Function and mutant straina | STM no. | Gene designationb | Similarityc

|

Function | Predicted polarity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | % Identity (% similarity) | Genus | |||||

| Cell metabolism | |||||||

| VA01 | E0505 | galK | Klebsiella | Galactokinase | None | ||

| VA04 | E1013 | kva04 | proV | 92 (96) | Salmonella | Glycine betain/l-proline ABC transporter | None |

| VA09 | G1201 | kva09 | araF | 91 (96) | Escherichia | l-Arabinose binding periplasmic protein | None |

| VA17 | E2605 | kva17 | rhaB | 41 (59) | Lactobacillus | α-l-Rhamnosidase, putative | None |

| VA24 | E2945 | kva24 | gabD | 91 (95) | Escherichia | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | gabT and gabP |

| VA29 | C5243 | kva29 | pgdH | 34 (54) | Serratia | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | None |

| VA32 | E5721 | galT | Klebsiella | Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | galK | ||

| VA33 | A5901 | ahpC | ahpC | 99 (100) | Salmonella | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | None |

| Cell surface components and transporters | |||||||

| VA05 | D1112 | mrkC | Klebsiella | Usher protein of type III fimbriae | mrkD and mrkF | ||

| VA08 | E1205 | kva08 | hgpA | 28 (46) | Haemophilus | Hemoglobulin binding protein | None |

| VA10 | G1706 | kva10 | pls | 29 (33) | Streptococcus | Surface large repetitive protein | None |

| VA13 | G1815 | kva13 | pteA | 39 (60) | Bacillus | Cellobiose-specific phosphotransferase IIA | None |

| VA22 | F2730 | kva22 | pteC | 55 (75) | Bacillus | Cellobiose-specific phosphotransferase IIC | None |

| VA23 | A2805 | fimC | Klebsiella | Chaperon protein of type I fimbriae | fimD | ||

| VA27 | E5021 | pagO | Klebsiella | PhoPQ-activated integral membrane protein | None | ||

| VA28 | E5145 | kva28 | uraA | 93 (97) | Escherichia | Uracil permease | None |

| Regulation | |||||||

| VA02 | F0514 | cbl | Klebsiella | HTH-type transcriptional regulator Cbld | None | ||

| VA12 | E1813 | kvgA | evgA | 50 (66) | Escherichia | Response regulator of two component system | kvgS |

| VA14 | F2014 | moaR | Klebsiella | Monoamine regulon positive regulator | None | ||

| VA18 | G2615 | kvgS | evgS | 52 (68) | Escherichia | Histidine kinase sensor | None |

| VA25 | E3045 | kva25 | csgD | 39 (62) | Salmonella | Response regulator for second curli | None |

| Hypothetical and others | |||||||

| VA07 | G1115 | kva7 | Hypothetical protein | None | |||

| VA11 | D1812 | kva11 | yfgG | 77 (91) | Escherichia | Hypothetical protein YfgG | None |

| VA15 | E2145 | kva15 | Putative LuxR family transcription regulator | None | |||

| VA19 | C2619 | kva19 | Putative UphA family transcription regulator | None | |||

| VA20 | D2620 | kva20 | int | 92 (96) | Escherichia | Putative integrase | None |

| VA21 | C2635 | kva21 | ymdF | 85 (94) | Escherichia | Conserved hypothetical protein YmdF | None |

| VA26 | H4601 | kva26 | lyxK | 31 (49) | Pasteurella | Putative l-xylulokinase | pgdH |

Twenty-eight KLA-attenuated mutant strains are shown and categorized by their putative functions. Class I mutant strains are indicated in bold.

Known K. pneumoniae genes or ORFs identified as kva (klebsiella virulence associated).

Genes encoding proteins or hypothetical proteins in the public database with the highest similarity to the sequences identified. Identities and similarities were determined at the amino acid level over the entire ORF.

HTH, helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characterization of KLA-attenuated mutantsa

| Function and mutant strain | Gene designation | In vitro CIb

|

Uronic acid contentc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | M9-glucose | |||

| Cell metabolism | ||||

| VA01 | galK | 1.037 ± 0.006 | 1.007 ± 0.038 | 18.9 ± 2.7 |

| VA04 | proV | 1 ± 0.017 | 0.993 ± 0.051 | 14.5 ± 1.8 |

| VA09 | araF | 1.017 ± 0.006 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 14.2 ± 0.9 |

| VA17 | rhaB | 1.063 ± 0.012 | 0.683 ± 0.081 | 13.1 ± 1.5 |

| VA24 | gabD | 1.027 ± 0.025 | 0.93 ± 0.017 | 12.2 ± 1.0 |

| VA29 | pgdH | 0.987 ± 0.006 | 0.967 ± 0.032 | 21.9 ± 2.1 |

| VA32 | galT | 1 ± 0.01 | 0.947 ± 0.015 | 19.6 ± 2.7 |

| VA33 | ahpC | 1.017 ± 0.025 | 0.937 ± 0.059 | 18.5 ± 3.8 |

| Cell surface components and transporters | ||||

| VA05 | mrkC | 1.007 ± 0.006 | 0.94 ± 0.064 | 12.5 ± 0.9 |

| VA08 | hgpA | 0.98 ± 0.015 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 14.5 ± 1.4 |

| VA10 | pls | 1.02 ± 0.026 | 1.013 ± 0.049 | 23.2 ± 3.8 |

| VA13 | pteA | 0.983 ± 0.021 | 0.963 ± 0.025 | 13.3 ± 2.3 |

| VA22 | pteC | 0.987 ± 0.025 | 0.963 ± 0.042 | 19.5 ± 1.2 |

| VA23 | fimC | 1 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.026 | 24.5 ± 2.1 |

| VA27 | pagO | 0.967 ± 0.012 | 0.917 ± 0.015 | 20.0 ± 1.5 |

| VA28 | uraA | 0.997 ± 0.032 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 12.5 ± 1.8 |

| Regulation | ||||

| VA02 | cbl | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 1.027 ± 0.047 | 15.3 ± 0.9 |

| VA12 | kvgA | 1.017 ± 0.012 | 0.983 ± 0.05 | 13.8 ± 1.5 |

| VA14 | moaR | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.046 | 13.4 ± 3.2 |

| VA18 | kvgS | 1.003 ± 0.012 | 0.933 ± 0.023 | 15.0 ± 2.0 |

| VA25 | csgD | 0.983 ± 0.021 | 0.957 ± 0.045 | 16.6 ± 2.0 |

| Hypothetical and others | ||||

| VA07 | Novel | 0.997 ± 0.011 | 0.98 ± 0.026 | 15.0 ± 1.2 |

| VA11 | yfgG | 1.02 ± 0.017 | 0.983 ± 0.059 | 19.0 ± 4.4 |

| VA15 | Novel | 0.99 ± 0.017 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 27.6 ± 7.3 |

| VA19 | Novel | 0.977 ± 0.021 | 0.967 ± 0.015 | 17.6 ± 2.1 |

| VA20 | int | 0.997 ± 0.035 | 0.937 ± 0.038 | 13.5 ± 1.0 |

| VA21 | ymdF | 0.963 ± 0.021 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 19.7 ± 2.9 |

The HV phenotypes of the colonies were determined using the string-forming test with blood agar, as described previously (13). All strains showed positive results, defined as the formation of a ≥10-mm length of string, like that formed by the wild-type strain. Bacterial resistance to serum killing was determined as described previously (13). If the bacteria examined showed a reduction of 2 log10 in CFU after 30 min of incubation with nonimmune human serum at 37°C, the strain was defined as serum sensitive. If the viability of a VA mutant was comparable to that of the parental strain, the VA mutant was considered serum resistant. All strains were serum resistant.

CI values were determined as described previously (16) and are shown as means ± standard deviations.

The uronic acid content levels of the capsular polysaccharides were determined as described previously (24) and are expressed as means ± standard deviations (μg/1010 CFU). The value for the parental strain was 17.0 ± 2.2.

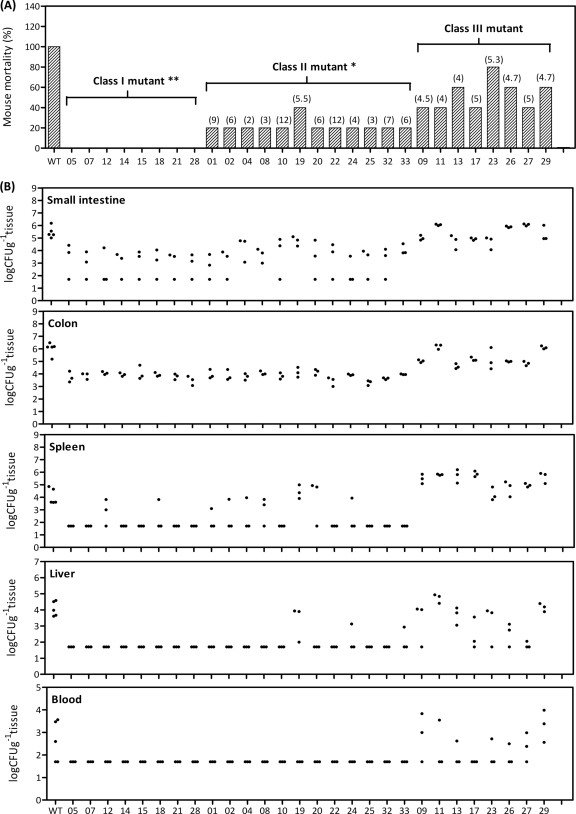

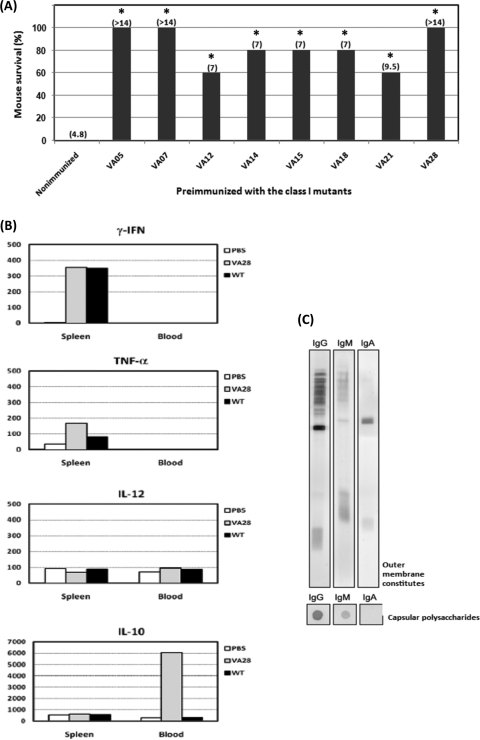

Based on the degree of their virulence attenuation, the 28 KLA-attenuated mutant strains were categorized into three classes. As shown in Fig. 4A, all mice infected with strains VA01, -05, -07, -12, -15, -18, -21, and -28 survived during the 1-month observation period. These strains were therefore regarded as class I mutants due to their loss of virulence in mice. Also different from wild-type K. pneumoniae, which killed mice in 8 days, with an MDD of 4, strains VA02, -04, -08, -10, -14, -19, -20, -22, -24, -25, -32, and -33 caused death in only 20 to 40% of the infected mice (P < 0.05; Kaplan-Meier analysis) and were therefore regarded as class II mutants. The class III mutants included the remaining seven VA strains, whose virulence to BALB/c mice did not significantly decrease in the independent infection experiments, but whose virulence attenuation was exhibited in the competitive infection experiments.

FIG. 4.

Virulence attenuation in independent infection experiments. (A) Five BALB/c mice were orally administered 107 CFU of a single KLA-attenuated mutant strain. The survival rate of these mice was monitored daily for 2 weeks. MDD are shown in parentheses, and both mortality rate and MDD were determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Strains VA05, -07, -12, -14, -15, -18, -21, and -28, which were avirulent in mice during the observation period, were regarded as class I mutants. Strains VA01, -02, -04, -08, -10, -19, -20, -22, -24, -25, -32, and -33, which resulted in mortality rates of 20% to 40% in mice, had their virulence attenuated to a statistically significant level (P < 0.05) and were therefore categorized as class II mutants. The remaining VA strains, with no significantly attenuated virulence, were grouped as class III mutants. (B) Bacterial growth in different mouse tissues. Three BALB/c mice were orally administered 107 CFU of a single KLA-attenuated mutant strain. Small intestine, colon, spleen, liver, and blood samples were harvested at 48 hpi to enumerate bacterial concentrations, which were expressed as numbers of CFU g−1 tissue or CFU ml−1 blood. The limit of detection was approximately 50 CFU. Samples which yielded no colonies were plotted as having values of 50 CFU g−1 tissue or CFU ml−1 blood.

As mentioned above, four separate stages of K. pneumoniae oral infection (intestinal colonization, extraintestinal dissemination, hepatic replication, and septic metastasis) were observed to develop sequentially in our mouse model. Because the 28 mutant strains were identified on the basis of their failure to be recovered from the liver or the spleen at 48 hpi, it is of interest to determine whether these attenuations resulted from the incapability of these mutants to achieve any particular infectious stage. Therefore, bacterial concentrations of each mutant strain in different mouse tissues were measured at 48 hpi in order to follow their distributions in the infected mice. As shown in Fig. 4B, the class I and II mutants were present at significantly lower concentrations than the wild-type strain in the small intestines and colons of the infected mice. Apparently, most of the class I (VA05, -07, -14, -15, -21, and -28) and class II (VA10, -22, -25, and -32) mutant strains were not detected in samples from extraintestinal sites, including the spleen, liver, and bloodstream, whereas 60% of the mice which were infected with wild-type K. pneumoniae developed bacteremia at the same time point. On the other hand, when each of the class I mutant strains was inoculated into BALB/c mice via an intraperitoneal route with an inoculum of 102 or 105 CFU, as shown in Table 3, all of the strains exhibited virulence comparable with that of the wild-type strain. These results suggested that the attenuation of these mutant strains was restricted within the intestinal tract. Unlike the class I and II mutants, most of the class III mutant strains generally caused the infected mice to develop KLA symptoms and were capable of propagating themselves to reach concentrations comparable to those of the wild-type strain in all the mouse tissues examined in the independent infection experiments (Fig. 4B). Nevertheless, in the competitive infection experiments, class III mutants exhibited significant disadvantages in comparison with the wild-type strain with respect to the spleen, the liver, or both organs (Table 4), suggesting that the mutations affected hepatosplenic colonization of K. pneumoniae after extraintestinal dissemination. Interestingly, strain VA17 (rhaB::Tn10) showed no defects in the competition assay, even though this strain was undetectable in the bloodstream when inoculated independently, suggesting that bacterial propagation in the blood might be affected by this mutation.

TABLE 3.

Intraperitoneal virulence of class I mutant strainsa

| Strain | % Inoculum (MDD)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 × 103 CFU | 5 × 105 CFU | |

| Wild type | 0 (2) | 0 (1) |

| Nonencapsulated mutant | 100 (>14) | 100 (>14) |

| VA05 | 0 (2) | 0 (1) |

| VA07 | 0 (2.7) | 0 (1) |

| VA12 | 0 (2) | 0 (1) |

| VA14 | 0 (3.7) | 0 (1) |

| VA15 | 0 (2.3) | 0 (1) |

| VA18 | 0 (2.3) | 0 (1) |

| VA21 | 0 (3) | 0 (1) |

| VA28 | 0 (2.3) | 0 (1) |

Three 8-week-old male BALB/c mice were challenged with a particular K. pneumoniae strain via an intraperitoneal route. The survival rate of the mice was monitored daily for 2 weeks, and survival rate and MDD were determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis using Prism4 for Windows (GraphPad).

TABLE 4.

Competition assay for class III mutant strains

| Strain | CI (P)a

|

No. of mice with KLA symptomsb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | ||

| VA09 (araF::Tn10) | 0.15 ± 0.003 (<0.05) | 0.069 ± 0.004 (<0.05) | 2 |

| VA11 (yfgG::Tn10) | 0.086 ± 0.024 (<0.05) | 1.50 ± 0.16 (−) | 1 |

| VA13 (pteA::Tn10) | 0.018 ± 0.04 (<0.05) | 1.15 ± 0.14 (−) | 1 |

| VA17 (rhaB::Tn10) | 2.12 ± 0.66 (−) | 1.47 ± 0.09 (−) | 1 |

| VA23 (fimC::Tn10) | 0.017 ± 0.008 (<0.05) | 0.111 ± 0.043 (<0.05) | 1 |

| VA26 (lyxK::Tn10) | 0.0014 ± 0.0004 (<0.05) | 0.765 ± 0.053 (−) | 0 |

| VA27 (pagO::Tn10) | 0.14 ± 0.0003 (<0.05) | 0.0111 ± 0.067 (<0.05) | 2 |

| VA29 (pgdH::Tn10) | 0.73 ± 0.005 (−) | 0.005 ± 0.001 (<0.05) | 3 |

A mixture of equal amounts of the wild type (5 × 106 CFU) and a mutant strain (5 × 106 CFU) was orally inoculated into three 8-week-old BALB/c mice. CI values were calculated at 48 hpi as described previously (16) and are shown as means ± standard deviations. P values were determined using the Mann-Whitney test in the Prism4 software program (GraphPad). “−” indicates that the decrease in the CI value was not statistically significant.

Development of KLA symptoms was determined by the formation of liver abscess foci at 48 h after an oral inoculation with 107 CFU of a particular class III mutant strain.

Protective immunization of the class I mutants against challenge with the wild-type strain.

As revealed in the independent infection experiments, the class I mutants colonizing the intestine had only a limited ability to induce systemic spreading and were avirulent to BALB/c mice when given via the oral route. Because these strains still produced the wild-type capsule and retained their resistance to serum killing (Table 2), we were interested in knowing whether these avirulent yet immunogenic strains had the potential to serve as candidates for live vaccines. To test this possibility, groups of BALB/c mice were orally administered each of the type I mutant strains with a single dose of 107 CFU. Six weeks later, these preimmunized mice, together with age-matched naïve mice, were challenged with 107 CFU of wild-type K. pneumoniae. As shown in Fig. 5A, immunization with any of the class I mutants provided mice with significant protection against wild-type K. pneumoniae infection, compared with what was found for the control group, in which all of the naïve mice died within 2 weeks. In particular, none of the mice that were orally administered a single dose of bacterial cultures from VA05, VA07, or VA28 succumbed to the subsequent challenge with the wild-type strain (Fig. 5B), and at 7 days postinfection, bacteria were cleared from all examined tissues obtained from these mice (data not shown). In addition, preimmunization with VA28 evoked increases in proinflammatory cytokine release, including gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-10 (IL-10) (Fig. 5B) and stimulated the production of protective antibodies against the outer membrane constituents as well as the capsular polysaccharides of K. pneumoniae (Fig. 5C). Together, these results indicated that these class I mutants could be utilized as oral-administered live vaccine candidates.

FIG. 5.

Characterization of the avirulent yet immunogenic class I mutant strains. (A) Oral administration with the class I mutants allowed mice to survive challenge with wild-type K. pneumoniae infection. Five BALB/c mice were orally administered a single dose of 107 CFU of a particular class I mutant strain. The preimmunized mice, together with age-matched naïve mice, were challenged with 107 CFU of wild-type K. pneumonia 6 weeks later. The survival rate of the infected mice was monitored daily for 2 weeks. MDD are shown in parentheses, and both mortality rate and MDD were determined by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Sera from all mice were collected 1 day prior to challenge with the wild-type strain and were used to detect the production of K. pneumoniae-specific antibodies. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Statistical significance was determined by comparison of survival curves by use of the log rank test (Kaplan-Meier analysis; Prism4). (B) Cytokine production upon oral administration with the class I mutant VA28. Sera and spleens were collected at 24 hpi and were analyzed for cytokine production by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The mean production levels of cytokines (gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-12, and IL-10) in five mice per group are shown in pg per 100 μg of total proteins. (C) Specific antibodies against the outer membrane constituents and capsular polysaccharides of K. pneumoniae were detected in pooled antisera from the five mice that were preimmunized with VA28.

Molecular characterization of the class I mutants.

Genetic loci which were transposon mutated in the eight class I mutant strains (VA05, -07, -12, -14, -15, -18, -21, and -28) encoded products with predicted roles in metabolism, adhesion, transportation, gene regulation, and unknown functions. As shown in Table 1, strain VA05 had an insertion in mrkC, along with a polar effect on mrkD and mrkE, which abrogated the assembly and anchorage of the type III fimbriae (2, 15). Strain VA28 was mutated in gene uraA, which encodes uracil permease. Meanwhile, a two-component system encoding gene cluster kvgAS (8, 21) was disrupted in strains VA12 (kvgA::Tn10) and VA18 (kvgS::Tn10). Gene moaR, which encodes a positive regulator of the monoamine regulon in Klebsiella aerogenes, was inactivated in VA14. The gene product of kva15, which was disrupted in VA15, had a predicted function as a transcriptional regulator of the LuxR family. A homologue of the conserved hypothetical protein YmdF was inactivated in VA21.

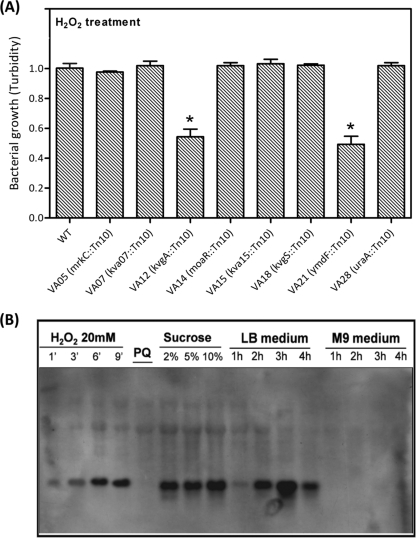

During the development of liver abscess, the orally inoculated K. pneumoniae must circumvent a wide variety of stresses. We reasoned that the virulence attenuation of the class I mutants might be a consequence of reduced tolerance to the stress that bacteria encountered inside the host, such as gastric acids, bile insults, nutrient limitation, or reactive oxidative species inside the macrophages. Therefore, the bacterial growth of each class I mutant strain under different stressful conditions was measured. As shown in Fig. 6A, the growth capacities of strains VA12 (kvgA::Tn10) and VA21 (ymdF::Tn10) were significantly reduced upon exposure to H2O2. Because YmdF was predicted to function as a general stress protein in E. coli, we were interested in knowing whether it played a role in the tolerance response to stress in K. pneumoniae. The transcript abundance of ymdF (kva21) under different stressful conditions was measured with Northern analyses. When wild-type K. pneumoniae grew in LB medium, the ymdF transcript level steadily increased and reached a peak at the stationary phase (Fig. 6B, lanes 9 to 12), while no ymdF transcripts were detected when the bacteria were incubated in M9-glucose medium (Fig. 6B, lanes 13 to 16). However, the amount of ymdF transcripts increased rapidly in K. pneumoniae at 6 min posttreatment with 20 mM H2O2 (Fig. 6B, lane 3), compared to that in K. pneumoniae which was cultured in LB medium for 1 h (Fig. 6B, lane 9). Similar significant increases in ymdF transcript levels could also be observed in K. pneumoniae after 15 min-treatments with different concentrations of sucrose (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 to 8). These results revealed an involvement of YmdF in the tolerance response to oxidative and osmotic stress of K. pneumoniae. Together with the results from independent infection experiments (Fig. 4B), it appeared that inactivation of ymdF attenuated the resistance of K. pneumoniae to stress and thus made K. pneumoniae incapable of translocation across the intestinal barrier.

FIG. 6.

Role for K. pneumoniae YmdF in resistance to oxidative stress. (A) Tolerance responses of class I mutants to various stresses. Bacterial cultures of the wild type and each of the class I mutants, which were grown in LB medium at 37°C, were adjusted to a turbidity value of 1 and were then subjected to treatment with 20 mM of H2O2 for 2 h at 37°C. The bacterial concentration upon oxidative stress was determined using a MicroScan turbidity meter (Dade Behring, CA). Results shown are means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. * indicates statistical significance as determined by Student's t test (P < 0.05). (B) Northern blot analysis of ymdF transcripts. Total RNAs were isolated from wild-type K. pneumoniae grown in LB, in M9-glucose, and under various stress conditions. Twenty micrograms of total RNA from each sample was subjected to Northern blotting, and a biotin-labeled ymdF RNA probe was used for the hybridization. The expression levels of ymdF upon exposure to H2O2 for 1, 3, 6, 9 min; treatment with 15 mM paraquat (PQ); or treatment with different concentrations of sucrose for 15 min are shown in lanes 1 to 8, and the abundances of ymdF transcripts in K. pneumoniae grown in LB or M9-glucose medium is shown in lanes 9 to 16.

Regulatory Kva in control of kva gene expression.

Seven of the 28 kva genes identified in this study (kva02, -12, -14, -15, -18, -19, and -25) were found to encode proteins with regulatory functions (Table 1). These regulatory kva genes played indispensable roles in the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae because all the mutant strains that carry transposon insertions in these genes exhibited significantly reduced virulence (Fig. 4). Bacterial virulence genes are generally controlled under a complicated regulatory network to ensure their expression at the right time and the right site during infection. Therefore, it was of interest to observe whether these seven regulatory kva genes modulated the expression of other kva genes to affect the virulence of K. pneumoniae. For this purpose, the transcript levels for all kva genes in wild-type K. pneumoniae and different regulatory kva mutant strains were determined by using semiquantitative RT-PCR with gene-specific primers. The transcripts of five kva genes (kva04, kva22, kva24, kva26, and kva29) were undetectable in wild-type K. pneumoniae grown under the in vitro conditions tested (LB for 1 h, LB for 4 h, M9-glucose for 1 h, and M9-glucose for 4 h), suggesting that these genes might be specifically expressed in vivo. After normalization to an internal control, the in vitro differences in the transcript levels of 23 kva genes were determined and are shown in Table 5. Remarkably, at least 10 of these kva genes exhibited >2-fold decreases in their transcript abundances in VA02 (cbl::Tn10), VA14 (moaR::Tn10), and VA15 (kva15::Tn10). The overlap of downregulated genes in the three mutant strains indicated that these downstream kva genes, together with cbl, moaR, and kva15, appeared to be part of the same regulatory network. In addition, there were several kva genes under the control of the KvgAS two-component system; a response regulator other than KvgA might be involved in transduction of the KvgS signal, since the kva13 transcript was absent only in VA18 (kvgS::Tn10). The transcript abundances of a relatively small number of kva genes were affected in VA25 (csgD::Tn10) and VA19 (kva19::Tn10), indicating that the regulatory networks exerted by these two regulators were different from those for other regulatory kva genes, in which a large number of downstream genes were not recovered, due to an unsaturated search in this STM screen. On the other hand, the expression of kva25 was upregulated in VA12 (kvgA::Tn10), and two- to fourfold increases in expression of kva09 were also observed in some regulatory kva mutants. Most strikingly, the transcript levels of mrkC and kva08 declined significantly in all of the regulatory mutants, suggesting that regulatory networks exerted by the Kva regulators might converge at these two effectors. These results indicated that the regulatory kva genes functioned coordinately to control the expression of a subset of genes, including downstream kva genes, which allowed K. pneumoniae to respond to the stress correctly and infect its hosts successfully.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of kva gene transcript levels in the wild-type and regulatory kva mutant strains

| Mutant class and gene | Fold differencea

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA02 (cbl::Tn10) | VA14 (moaR::Tn10) | VA15 (kva15::Tn10) | VA12 (kvgA::Tn10) | VA18 (kvgS::Tn10) | VA19 (kva19::Tn10) | VA25 (csgD::Tn10) | |

| I | |||||||

| mrkC | − | 0.320 | 0.280 | 0.353 | 0.429 | 0.418 | 0.305 |

| kva7 | 0.274 | 0.419 | 0.336 | 0.784 | 0.593 | 0.556 | 0.477 |

| kvgA | 0.553 | 1.112 | 0.537 | − | 0.612 | 1.005 | 0.537 |

| moaR | 0.912 | − | 0.812 | 0.717 | 0.898 | 0.888 | 0.832 |

| kva15 | 0.372 | 0.673 | − | 0.721 | 0.461 | 0.829 | 0.494 |

| kvgS | 0.776 | 0.595 | 0.759 | − | − | 0.862 | 0.922 |

| kva21 | 1.059 | 0.727 | 0.316 | 1.027 | 0.433 | 0.556 | 0.658 |

| kva28 | 0.758 | 1.099 | 0.269 | 0.313 | 0.346 | 1.330 | 0.582 |

| II | |||||||

| galK | 0.362 | − | − | 0.394 | 0.500 | 0.894 | 0.596 |

| cblb | − | − | 0.850 | − | 0.900 | 0.950 | 0.588 |

| kva8c | 0.092 | 0.330 | 0.151 | 0.281 | 0.265 | 0.254 | 0.178 |

| kva10 | 0.371 | 0.311 | 0.374 | 0.791 | 0.566 | 0.861 | 0.417 |

| kva19 | 0.579 | 0.913 | 0.552 | 1.120 | 0.749 | − | 0.710 |

| kva20 | 0.434 | 0.678 | 0.455 | 0.836 | 0.559 | 0.615 | 0.531 |

| kva25 | 0.951 | 1.410 | 1.069 | 2.347 | 1.326 | 1.292 | − |

| galT | 0.406 | − | 0.508 | 0.374 | 0.428 | 0.706 | 0.642 |

| III | |||||||

| kva9b | 1.789 | − | 2.596 | 1.982 | 2.579 | 4.561 | 2.667 |

| kva11 | 0.381 | 0.470 | 0.483 | 0.936 | 0.597 | 0.712 | 0.534 |

| kva13 | 0.522 | 0.119 | 0.493 | 0.903 | − | 1.194 | 0.731 |

| kva17 | − | − | 0.333 | 0.743 | 0.857 | 0.724 | 0.819 |

| fimC | 0.989 | 0.108 | 0.742 | 1.688 | 1.161 | 1.581 | 1.097 |

| pagO | 0.628 | 1.377 | 1.014 | 1.214 | 0.930 | 1.195 | 0.977 |

| ahpC | 0.910 | 1.181 | 0.777 | 1.108 | 0.861 | 0.976 | 0.964 |

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was used to determine the relative transcript abundance of every kva gene in wild-type K. pneumoniae and each of the regulatory kva mutant strains. The relative transcript abundance of a particular kva gene in a bacterial strain was measured by quantification of the band intensity of the specific RT-PCR product, which was normalized to that of GAPDH. The level of each kva transcript from the wild-type strain was normalized to a value of 1. The transcripts of kva04, kva22, kva24, kva26, and kva29, which were not detected in wild-type K. pneumoniae grown under the in vitro conditions tested, are not shown. The differences in kva transcript levels between each of the regulatory mutant strains [VA02 (cbl::Tn10), VA12 (evgA::Tn10), VA14 (moaR::Tn10), VA15 (kva15::Tn10), VA18 (evgS::Tn10), VA19 (kva19::Tn10), and VA25 (csgD::Tn10)] are indicated (means of results from two independent determinations). The expression levels of specific kva genes which were downregulated in a particular regulatory kva mutant more than twofold are indicated in bold. “−” indicates that the transcripts of a specific kva gene were not detected under the in vitro conditions tested by two independent experiments.

The transcripts of cbl and kva9 were detected only in the stationary-phase LB cultures.

The kva08 transcripts were detected under the cultivation with M9-glucose medium.

DISCUSSION

K. pneumoniae is a worldwide-spread pathogen responsible for a broad spectrum of clinical syndromes. Since the 1980s, a single-pathogen-induced form of PLA, which is clinically and etiologically distinct from polymicrobial PLA, has been noticed to be predominantly mediated by primary infection with K. pneumoniae (20, 42). Although the clinical significance of K. pneumoniae in association with primary liver abscess has been established, we have limited knowledge regarding the molecular basis of how this bacterium causes an infection in the liver. The intestine is one of the major reservoirs of K. pneumoniae, but how the intestine-colonizing K. pneumoniae bacteria can acquire an ability to translocate across the intestinal barrier, disseminate systematically, and finally gain growth advantages within specific niches in the liver still remains elusive. We reasoned that a cohort of genes whose expression was coordinately regulated were necessary for K. pneumoniae to complete the process from colonization of the intestine to infection of the liver. To gain insights into the pathogenesis of KLA, in this study, we established a mouse model and conducted a genetic screen for KLA-attenuated mutants. Although it had been shown that injecting 102 to 105 CFU of a K1-type K. pneumonia strain intraperitoneally or intravenously induced KLA symptoms in mice (13, 43), we decided to apply an oral inoculation method. This method comparatively provided a more relevant route in the pathogenesis of KLA, because epidemiological studies suggest that the majority of K. pneumoniae infections are preceded by colonization of the patient's gastrointestinal tract (30), and the corresponding immune responses are likely to be stimulated via gut-associated lymphoid tissues. By means of oral administration, infection of BALB/c mice with K. pneumoniae KLA isolates demonstrated significant similarities to the human KLA, including a dramatic rate of bacterial replication, infiltration of inflammatory cells, formation of microabscess foci in the liver, and lethality upon subsequent bacteremia and septicemia. The development of these KLA symptoms was consistently observed in mice challenged with 1 × 107 CFU of K. pneumoniae CG43 (K2-serotype) as well as in mice treated with two other K1 KLA isolates of K. pneumoniae (data not shown). Besides, this method also allowed us to monitor the progression of KLA in mice by sampling sites along the infectious route from the intestines to the liver. Interestingly, we observed that K. pneumoniae induced systemic infection in mice via the development of four sequential stages, including intestinal colonization, extraintestinal dissemination, hepatic replication, and septic metastasis. Different from the polymicrobial PLA, which was generically secondary to hepatobiliary infections, the propagation of K. pneumoniae from the intestine to the liver proceeded via the bloodstream, as indicated in our model in which the extraintestinal bacteria were first detected in the spleen at 24 h after oral inoculation. Taken together, the oral infection model established in this study could recapitulate the major characteristics of bacteremic liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae.

The genetic factor required for development of K. pneumoniae-induced bacteremic liver abscess was subsequently determined in this oral infection model. An STM technique was used as our in vivo screening approach to identify mutants which failed to replicate in either the spleen or the liver. A total of 33 independent strains were obtained from two rounds of in vivo selection, accounting for 1.1% of the total number of mutants. Because only mutants which were attenuated in both the liver and the spleen were identified, the recovery rate was lower than the 2 to 10% attenuation relative to that reported for other STM screens (38). In addition, the preselecting procedure in which only mutants producing the wild-type capsule were subjected to in vivo screening may also reduce the numbers of isolated mutants since capsule is a well-documented virulence determinant for K. pneumoniae. Capsule was reported to be indispensable for development of K. pneumoniae-induced systemic infection in a pneumonia model of C57B6 mice (24) and in a bacteremia model of BALB/c mice (7). Therefore, minimizing the number of mutants with insertions in the capsule polysaccharide synthesis locus would facilitate identifying putative virulence factors which had not been previously characterized. Through this effort, though our screening of 2,880 mutants was not a saturating search, we identified a variety of genetic loci which encode both novel and previously known bacterial factors other than the capsule. None of these genes have been identified in the previous STM screens conducted in different infection models (24, 27, 41).

To further confirm whether the attenuated mutants had genuine defects in bacterial pathogenesis, we utilized independent infection experiments as the secondary screen. This approach was chosen instead of the conventional competition assay because possible bias might result from the interference of extracellular substances produced by the wild-type strain during the in vivo competition. We categorized the 28 KLA-attenuated mutant strains into three classes according to the degrees of their virulence attenuation (Fig. 4A). When given via the oral route with an inoculum of 107 CFU, the class I and II mutant strains exhibited significantly reduced virulence to BALB/c mice (P < 0.05), and most of these strains were not detected in extraintestinal tissues at 48 hpi (Fig. 4B). Apparently, the virulence of these strains was attenuated, because they failed to reach the extraintestinal dissemination stage. This failure could reasonably be attributed to the inability of these mutants to translocate across the intestinal barrier or the loss of bacterial resistance to serum killing. Because all of the class I and II mutant strains were as resistant as the wild type to the killing of normal human sera (Table 2) and the class I mutant strains exhibited virulence comparable to that of the wild-type strain when they infected mice via an intraperitoneal route (Table 3), genetic loci which were mutated in these strains could reflect the genetic requirement for K. pneumoniae in dissemination beyond the intestine. While the class I and II mutant strains were restricted in the intestine, the retained ability of the class III mutants to translocate to distal sites allowed strains of this class to exhibit levels of virulence in mice comparable to those for the wild type. The findings led us to reason that in the oral infection model, the ability of K. pneumoniae to progress from intestinal colonization to extraintestinal replication may determine its host lethality. Although no significant decreases in the mortality rates of those class III mutant-infected mice were observed at the statistical level, six of the class III mutant strains were significantly outcompeted by the wild-type strain in the spleen, the liver, or both organs (Table 4). Identification of genes which were disrupted in these class III mutants might provide information about certain limited resources in vivo for which K. pneumoniae had to compete with other bacteria. Interestingly, one class III mutant, VA17 (rhaB::Tn10), exhibited increased competitive colonization in the spleen and liver but caused death in 40% of the infected mice. The decreased virulence of VA17 might be due to the affected capacity of this strain to propagate in the bloodstream, as no colonies were yielded in the blood samples obtained from the VA17-infected mice at 48 hpi (Fig. 4B).

Our findings that immunization of mice with a single dose of the class I mutants (VA05, VA07, or VA28) stimulated memory immune responses and provided complete protection against lethal K. pneumoniae challenge demonstrated a great potential for the use of these mutants in prophylaxis against KLA disease. Previously, several purified components of K. pneumoniae, including capsular polysaccharides, lipopolysaccharides, and type III fimbriae (9, 12, 22, 44), as well as an acapsular K. pneumoniae mutant (23), had been used as immunizing agents against K. pneumoniae infection. However, the subunit vaccines required multiple parenteral injections and the use of immunostimulatory adjuvants, which sometimes stimulated only systemic humoral immune responses. On the other hand, acapsular mutants could not induce effective protective immunity, due to their lack of complete immunogenicity. Therefore, for vaccine development, the class I mutants identified here have several advantages. First, the failure of these strains to translocate across the intestinal barrier led them to trigger self-limited infection only in the intestine, without causing any symptoms of KLA disease. Not only systemic humoral immune responses but also the mucosal immunity was induced upon oral immunization with these strains. Second, in contrast to acapsular mutants, these strains carried intact capsular polysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide antigen and retained their resistance to host serum killing, which allowed the production of antibodies against K. pneumoniae cell surface components and the elicitation of immediate responses of the host's innate immunity (Fig. 5). Finally, the finding that a single dose of challenge with these strains via an oral route was enough to stimulate protective immune responses made these strains attractive for use as an orally administered vaccine. However, further studies are still required to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the application of these strains in prophylaxis against K. pneumoniae infections.

A glance at the genetic loci identified here (Table 1) suggests a requirement for cell surface components in the progression of KLA. Of particular interest is the identification of type I and III fimbriae: a transposon insertion in fimC with a polar effect on fimD that abrogated the chaperone-usher pathway in the biosynthesis of type I fimbriae was identified in strain VA23 (11), and the type III fimbria-encoding gene cluster mrkABCDE (2, 15) was disrupted in strain VA05 by a transposon insertion in mrkC. The inactivation of type I and type III fimbriae in VA23 and VA05, respectively, was ascertained by hemagglutination assays (data not shown). Though genetic loci encoding these two types of fimbriae were identified in the same screen, the type I and III fimbriae appeared to play different roles in the pathogenesis of K. pneumoniae. As indicated in the independent infection experiments (Fig. 4), the type I fimbria mutant VA23 (fimC::Tn10) exhibited the wild-type level of virulence and colonized all the mouse tissues examined, with its growth capacity unaffected. Consistent with this finding, it has recently been reported that the ability of K. pneumoniae with an isogenic type I fimbria mutation is not affected in colonizing the mouse intestine (40). The dispensability of the type I fimbriae was also shown in an intranasal infection model (4) in which a Tn5 mutant of fimA still retained 75% mortality for mice. Nonetheless, the type I fimbria was not totally unnecessary for K. pneumoniae, as it was determined to be a virulence factor in a urinary tract infection model (40) and the growth of the type I fimbria mutant strain in the liver was significantly attenuated in the competition with the wild-type strain (Table 4). In contrast to type I fimbriae, type III fimbriae were crucial for K. pneumoniae virulence in our oral infection model. As demonstrated in independent infection experiments, strain VA05 (mrkC::Tn10), whose ability to colonize the intestine was attenuated due to the inactivation of type III fimbriae, was unable to disseminate from the intestinal lumen to extraintestinal tissues and was consequently avirulent in mice (Fig. 4). The different requirements for type I and III fimbriae of K. pneumoniae in the progression of KLA will be further studied in the future.

Little is known about the regulatory cascades utilized by K. pneumoniae in the control of virulence gene expression so far. Interestingly, out of 28 kva genes identified in this study, there were 7 genes with regulatory functions. All the mutant strains featured insertions in these regulatory kva genes that were highly attenuated in mice, indicating a close correlation between these Kva regulators and bacterial virulence. The transcript abundances of quite a few kva genes were markedly changed in these regulatory kva mutants compared to that in the wild type, as revealed by semiquantitative RT-PCR (Table 5). The impact of the Kva regulators on K. pneumoniae virulence likely came from their transcriptional control of a panel of genes, some of which were identified in the same STM screen. By further comparing the kva gene expression profiles among the seven regulatory kva mutants, we found different subsets of kva genes with distinct expression patterns, which indicated the involvement of a number of regulatory networks controlling the virulence of K. pneumoniae. The fact that strains VA02, VA14, and VA15 shared the same set of downregulated kva genes indicated that Cbl, MoaR, and Kva15 might serve in the same regulatory network, which was different from that controlled by the KvgAS-dependent signaling system. This was also reflected by the observation of outer membrane proteins in which the overlap of changes in the outer membrane protein profiles for VA02, VA14, and VA15 was distinct from that for VA12 and VA18 (data not shown). Because the screening in this study was not saturated, there may be other members in these regulatory networks that remain to be identified. It is of considerable interest that the expression levels of mrkC and kva08 were downregulated in all the regulatory kva mutants. The convergence of Kva regulatory networks on the type III fimbria-encoding genes is reminiscent of the regulatory circuits controlling the expression of the pilus locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae (35). These results suggest that bacterial pili may function in parallel with other virulence mediators and that the regulation of pili is not assigned to a particular regulatory circuit. Although this work discloses only a part of the regulatory system controlling the expression of virulence factors required for K. pneumoniae to progress from intestinal colonization to the liver infection, our findings provide insights into the regulatory mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of this bacterium, which is far more complicated than previously thought. In this respect, we should view KLA as the outcome of a series of events orchestrated by a panel of virulence genes, and the expression of these genes is coordinately controlled when the bacteria are adapting inside the host.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to David Holden (Imperial College, London, United Kingdom) for the gift of E. coli strains CC118 λpir and S17-1 λpir as well as a pool of tagged pUTmini-Tn5km2 plasmids and to Shih-Feng Tsai (National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan) for DNA sequencing of K. pneumoniae CG43. We also thank the Pathology Department of Chung-Shan Medical University for technical assistance with histological experiments.

This work was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan (grants NSC95-3112-B-040-001, NSC96-3112-B-040-001, and NSC97-3112-B-040-001 to Y.-C. Lai) and by Chung-Shan Medical University (grants CSMU93-OM-B-030 and CSMU97-OM-A-168 to Y.-C. Lai).

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexeyev, M. F., and I. N. Shokolenko. 1995. Mini-Tn10 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and gene delivery into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Gene 16059-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, B. L., G. F. Gerlach, and S. Clegg. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and functions of mrk determinants necessary for expression of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 173916-920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 253389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boddicker, J. D., R. A. Anderson, J. Jagnow, and S. Clegg. 2006. Signature-tagged mutagenesis of Klebsiella pneumoniae to identify genes that influence biofilm formation on extracellular matrix material. Infect. Immun. 744590-4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braiteh, F., and M. P. Golden. 2007. Cryptogenic invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess syndrome. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 1116-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, K. S., W. L. Yu, C. L. Tsai, K. C. Cheng, C. C. Hou, M. C. Lee, and C. K. Tan. 2007. Pyogenic liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae: analysis of the clinical characteristics and outcomes of 84 patients. Chin. Med. J. (England) 120136-139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, H. Y., J. H. Lee, W. L. Deng, T. F. Fu, and H. L. Peng. 1996. Virulence and outer membrane properties of a galU mutant of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Microb. Pathog. 20255-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Y. T., H. Y. Chang, Y. C. Lai, C. C. Pan, S. F. Tsai, and H. L. Peng. 2004. Sequencing and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pLVPK of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Gene 337189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chhibber, S., S. Wadhwa, and V. Yadav. 2004. Protective role of liposome incorporated lipopolysaccharide antigen of Klebsiella pneumoniae in a rat model of lobar pneumonia. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 57150-155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, D. R., S. S. Lee, H. R. Lee, H. B. Kim, H. J. Choi, J. S. Eom, J. S. Kim, Y. H. Choi, J. S. Lee, M. H. Chung, Y. S. Kim, H. Lee, M. S. Lee, and C. K. Park. 2007. Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J. Infect. 54578-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clegg, S., B. K. Purcell, and J. Pruckler. 1987. Characterization of genes encoding type 1 fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella typhimurium, and Serratia marcescens. Infect. Immun. 55281-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cryz, S. J., Jr., E. Furer, and R. Germanier. 1986. Immunization against fatal experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 54403-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, C. T., Y. P. Chuang, C. T. Shun, S. C. Chang, and J. T. Wang. 2004. A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J. Exp. Med. 199697-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung, C. P., F. Y. Chang, S. C. Lee, B. S. Hu, B. I. Kuo, C. Y. Liu, M. Ho, and L. K. Siu. 2002. A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis? Gut 50420-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerlach, G. F., B. L. Allen, and S. Clegg. 1988. Molecular characterization of the type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 1703547-3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, C. Gleeson, M. D. Jones, E. Dalton, and D. W. Holden. 1995. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science 269400-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh, P. F., T. L. Lin, C. Z. Lee, S. F. Tsai, and J. T. Wang. 2008. Serum-induced iron-acquisition systems and TonB contribute to virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary pyogenic liver abscess. J. Infect. Dis. 1971717-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu, B. S., Y. J. Lau, Z. Y. Shi, and Y. H. Lin. 1999. Necrotizing fasciitis associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Clin. Infect. Dis. 291360-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, J. K., D. R. Chung, S. H. Wie, J. H. Yoo, and S. W. Park. 2009. Risk factor analysis of invasive liver abscess caused by the K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28109-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko, W. C., D. L. Paterson, A. J. Sagnimeni, D. S. Hansen, A. Von Gottberg, S. Mohapatra, J. M. Casellas, H. Goossens, L. Mulazimoglu, G. Trenholme, K. P. Klugman, J. G. McCormack, and V. L. Yu. 2002. Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8160-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai, Y. C., S. L. Yang, H. L. Peng, and H. Y. Chang. 2000. Identification of genes present specifically in a virulent strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 687149-7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavender, H. F., J. R. Jagnow, and S. Clegg. 2004. Biofilm formation in vitro and virulence in vivo of mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 724888-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawlor, M. S., S. A. Handley, and V. L. Miller. 2006. Comparison of the host responses to wild-type and cpsB mutant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Infect. Immun. 745402-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawlor, M. S., J. Hsu, P. D. Rick, and V. L. Miller. 2005. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence determinants using an intranasal infection model. Mol. Microbiol. 581054-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindstrom, S. T., P. R. Healey, and S. C. Chen. 1997. Metastatic septic endophthalmitis complicating pyogenic liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 2777-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma, L. C., C. T. Fang, C. Z. Lee, C. T. Shun, and J. T. Wang. 2005. Genomic heterogeneity in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains is associated with primary pyogenic liver abscess and metastatic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 192117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maroncle, N., D. Balestrino, C. Rich, and C. Forestier. 2002. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae genes involved in intestinal colonization and adhesion using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 704729-4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald, M. I. 1984. Pyogenic liver abscess: diagnosis, bacteriology and treatment. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 3506-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mine, T. 2005. Virulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strains and liver abscess with metastatic lesions. Hepatol. Res. 315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomerie, J. Z. 1979. Epidemiology of Klebsiella and hospital-associated infections. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1736-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadasy, K. A., R. Domiati-Saad, and M. A. Tribble. 2007. Invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae syndrome in North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45e25-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohmori, S., K. Shiraki, K. Ito, H. Inoue, T. Ito, T. Sakai, K. Takase, and T. Nakano. 2002. Septic endophthalmitis and meningitis associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Hepatol. Res. 22307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastagia, M., and V. Arumugam. 2008. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscesses in a public hospital in Queens, New York. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 6228-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosch, J. W., B. Mann, J. Thornton, J. Sublett, and E. Tuomanen. 2008. Convergence of regulatory networks on the pilus locus of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 763187-3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saenz, H. L., and C. Dehio. 2005. Signature-tagged mutagenesis: technical advances in a negative selection method for virulence gene identification. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8612-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]