Abstract

Centromeres are an essential and conserved feature of eukaryotic chromosomes, yet recent research indicates that we are just beginning to understand the numerous roles that centromeres play in chromosome segregation. During meiosis I, in particular, centromeres appear to function in many processes in addition to their canonical role in assembling kinetochores, the sites of microtubule attachment. Here we summarize recent advances that place centromeres at the centre of meiosis I, and discuss how these studies impact a variety of basic research fields and thus hold promise for increasing our understanding of human reproductive defects and disease states.

Introduction

A fundamental property of life is the ability to reproduce. Mitosis allows single-celled organisms to reproduce asexually and allows multi-cellular organisms to develop complex body plans. While mitosis is essential for the development and survival of multicellular organisms, it is not the only mechanism utilized by organisms to pass on their genetic information. Meiosis allows organisms to reproduce while simultaneously creating new genetic combinations that enable the creation of increasingly robust or specialized offspring. Meiosis is therefore not just an alternative mechanism by which organisms can reproduce; it is a process central to biological diversity.

The basic factors and mechanisms governing progression through mitosis and meiosis are the same (see reviews by 1-3). It is thus likely that meiosis evolved as a modified mitotic division. In order to halve the genome in meiosis, one DNA replication phase is followed by two DNA segregation phases, rather than the single segregation step seen in mitosis (Figure 1). The second meiotic division, meiosis II, resembles mitosis in that the duplicated genetic material, the sister chromatids, are segregated from each other. The first meiotic division, meiosis I, is unique in that homologous chromosomes segregate from each other. To achieve this, the mitotic division must be modified in three ways. These modifications are:

meiotic pairing, in which homologous chromosomes are aligned to facilitate (primarily) recombination-based linkages between homologs

step-wise loss of cohesion, in which cells remove separate populations of cohesins, the molecules that hold sister chromatids together, at meiosis I and meiosis II

sister kinetochore co-orientation, in which pairs of homologs linked through recombination (also known as bivalents) modulate their sister kinetochores so that they attach to microtubules emanating from the same spindle pole.

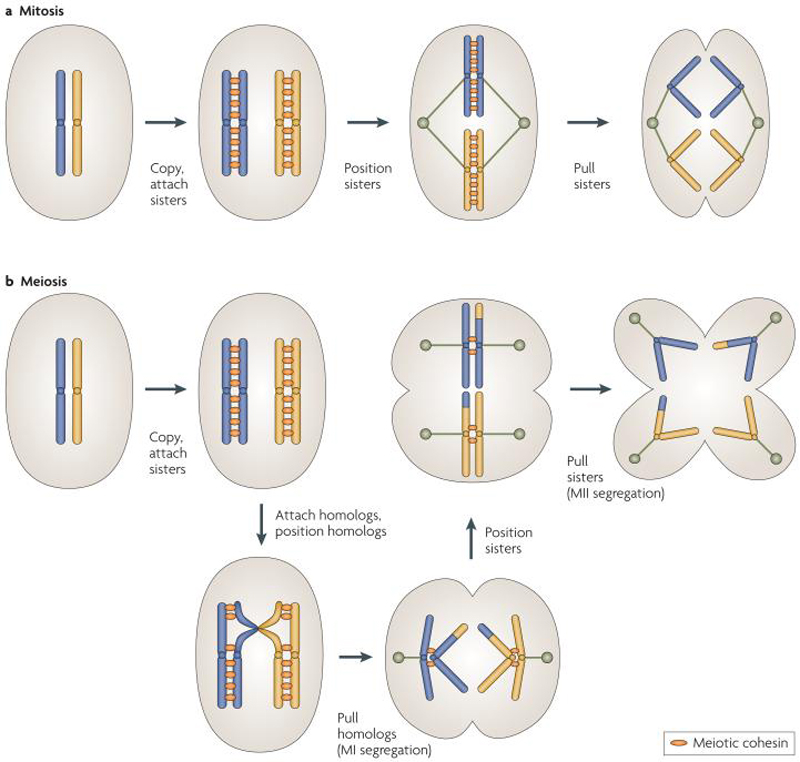

Figure 1. Comparison of mitosis and meiosis.

(A) Mitosis is essentially a cycle of duplication and sorting. Cells double their genetic content and then must ensure that this content is divided such that each resultant cell gets exactly one copy of each chromosome. This is achieved through attachment of newly formed sister chromatids, central positioning of attached sisters, and a spindle that pulls one sister of each homolog to a given pole. We thus can think of the mitotic cell cycle as a repeating series of: “copy, attachsisters, positionsisters, pullsisters”. Note that for simplicity, only one pair of homologs is pictured here, represented in yellow and blue.

(B) Meiosis, where the resultant cells need exactly one chromosome from a homolog pair, can then be similarly described as: “copy, attachsisters, attachhomologs, positionhomologs, pullhomologs, positionsisters, pullsisters”. With this notation, it is clear that meiosis has three basic steps that are unique and require unique mechanisms to achieve. The “attachhomologs” step is achieved through pairing and recombination, the “positionhomologs” step is through sister chromatid co-orientation, and the “pullhomologs” step occurs properly as a result of stepwise loss of cohesion.

Studies over the last few years have shown that all three meiosis I-specific modifications are influenced by the centromere. Here we will focus on the roles that centromeres play in pairing, step-wise loss of cohesion and kinetochore orientation. We will describe research from yeast, flies, nematodes, plants and mammals to highlight the essential and conserved nature of these centromere roles. We will end by discussing the potential significance of this research to understanding and battling human disease.

What defines a centromere?

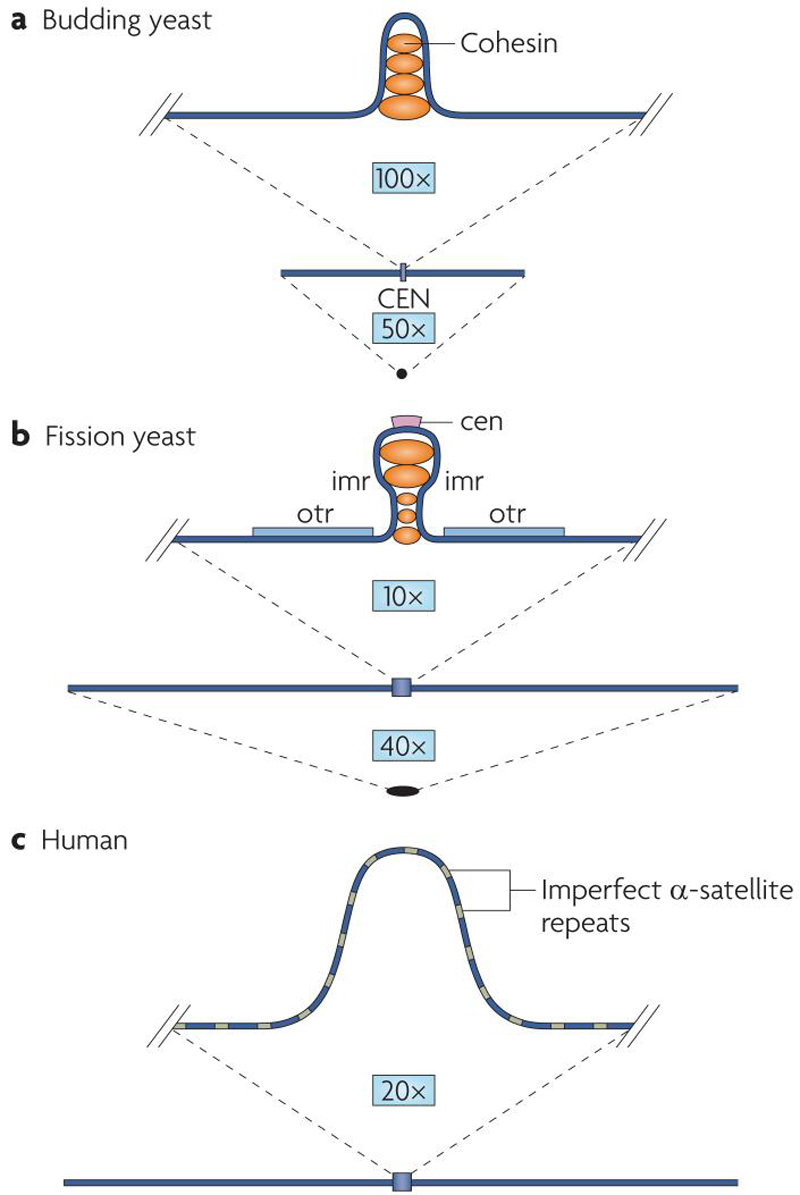

Centromeres are chromosomal regions that were originally defined cytologically by their ability to mediate attachment to microtubules through large protein structures known as kinetochores (see 4). Functionally, they were first characterized in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae as DNA sequences that conferred stable inheritance to origin of replication (ARS) carrying plasmids. The S. cerevisiae centromere is a well conserved sequences of only 120 base pairs with little, if any, repetitive sequence surrounding it (Figure 2A; 5, 6). This so-called “point centromere” is the simplest identified to date. Even other yeast species, such as the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, have a dramatically more complex centromere structure. S. pombe centromeres range from 35 to 110 kilobases in length with a central, non-repetitive region surrounded on either side by repeated elements termed inner repeats and outer repeats (Figure 2B; 7). Inner and outer repeats together represent a region that is termed “pericentric”, and is not well conserved between chromosomes. Animal and plant centromeres are in turn much more complex than S. pombe centromeres, spanning megabases of DNA and consisting almost entirely of repeated sequences, most notably so-called α-satellite DNA (Figure 2C; 7).

Figure 2. Comparison of the centromeres of budding yeast, fission yeast and humans.

(A) Budding yeast chromosomes average 780 kilobases, with a core centromere region of only 120 basepairs. Recent work shows a looped-out structure at the centromere that is similar to that seen in more complex eukaryotes.

(B) Fission yeast chromosomes average 4.2 megabases with an average centromere size of 70 kilobases. The centromere consists of a central region (cen), surrounded by inner repeats (imr), which are in turn flanked by outer repeats (otr). Like budding yeast, the fission yeast centromere forms a loop-like structure that extends outward from chromosomes.

(C) Human chromosomes average 143 megabases, with an average centromere size of 2.5 megabases, consisting primarily of tandem, degenerate 171 basepair α-satellite repeats (shown as green and blue bands). Note that chromosomes and centromeres are drawn roughly to scale.

Although centromeres are not conserved at the sequence level, the overall structure of the centromeric DNA with kinetechores assembled on it is remarkably similar across species (Figure 2). In mammalian cells, centromeres have been observed microscopically as elongated structures that stretch toward the cell poles during mitosis 8. This observation led to the hypothesis that centromeric DNA sequences fold into a loop-based structure that mediates microtubule attachment. Biochemical and genetic data in S. pombe support the existence of such a structure 9. Recent studies in S. cerevisiae also point towards the existence of looped-out centromeres in this organism, despite the remarkably simple centromere sequence in budding yeast. Yeh et. al (2008) 10 investigated centromere structure in mitosis through use of GFP fusions of the cohesin complex component Smc3. Cohesin has been shown to be present along chromosomes, with increased density in the vicinity of centromeres 11, 12. Yeh and colleagues 10 found that cells formed a cylindrical shaped Smc3-GFP array stretching outward from the chromosomes during metaphase. Use of a DNA fragmentation and PCR-based assay demonstrated that centromeric regions form loops that extend from chromosome axes and that these loops are stabilized by intrachromosomal cohesin linkages 10.

Given the low level of sequence similarity yet high level of structural conservation between centromeres within organisms and across species, it is thought that centromere identity is primarily epigenetically determined, with a given chromatin state leading to the assembly of the microtubule-capturing kinetochore. All core centromeres analyzed to date recruit nucleosomes containing the histone H3 variant CENP-A. These specialized nucleosomes serve as a primary marker of centromere identity (reviewed in 13), onto which a large protein structure composed of dozens of subunits, assembles into a unit that is estimated to be at least 5 megadaltons in mass, larger than even the ribosome 14. The proteins that bind to the centromere sequence (inner kinetochore components) are not conserved across species, but proteins that facilitate microtubule capture and binding, as well as components of surveillance mechanisms that monitor microtubule capture are. Their description is beyond the scope of this review but we wish to direct the readers to several excellent recent reviews on the subject 15-18.

In addition to centromere-specific histones that may only be present at the core centromere region, other epigenetic marks cover large regions around the core centromeres in many organisms. In S. pombe the RNAi machinery is central to controlling the chromatin state of pericentromeres, at least partially through promotion of Clr4 activity, which results in dimethylation of Histone 3 on Lysine 9 (H3K9me2). H3K9me2 then serves as a binding site for the heterochromatin-associated factor Swi6 19-21. This modification is well conserved, with H3K9me2 also seen in the pericentric regions of Drosophila chromosomes, where Su(var)3-9 is responsible for laying down the modification and HP1 binds H3K9me2 22, 23. Such large heterochromatic domains are not observed in S. cerevisiae, but recent work that will be discussed below argues that even the point centromeres of budding yeast are capable of assembling epigenetic regions that span kilobases around themselves 12, 24-26.

Centromeres: coordinating it all

When considering the centrality of centromeres to meiosis I chromosome segregation, it is interesting to note that the average chromosome in budding yeast is roughly 800 kilobases in length, with a core centromere of only 120 basepairs. This means that chromosomal regions that make up less than one six-thousandth of the yeast genome are largely responsible for organizing a multitude of steps in the meiotic segregation program. This ratio is larger in organisms with more nebulous centromeric sequences such as humans, in which centromeres make up approximately 2% of the genome, but still supports a disproportionately important role for centromeres in programming meiotic segregation (Figure 2). The recent understanding of the central role of centromeres in all three major cellular specializations in meiotic segregation requires that we expand the definition of centromeres from the classic view in which they merely mediate microtubule attachment. Rather, it appears that centromeres are signaling hubs that can influence chromatin structure over large chromosome expanses.

A possible role for centromeres in meiotic homolog pairing

Irrespective of which type of division cells undergo, the genetic material destined to be segregated from each other must be physically linked for tension-based mechanisms to segregate them (see Box 1). During mitosis, the linkage between sister chromatids through sister chromatid cohesion is mechanistically linked to the creation of sisters by DNA replication. A protein complex known as the cohesin complex is laid down between sister chromatids during DNA replication (Figure 1A). During meiosis II, as during mitosis, sister chromatids are segregated from each other and cohesins, assembled onto chromosomes during meiotic DNA replication, also function as linkages between sister chromatids (Figure 1B). As homolog pairs are not created together, cells must complete a series of events in meiotic prophase I to achieve homolog linkage. Once a linkage is created, tension-based mechanisms, like those operative during mitosis and meiosis II are able to promote the correct attachment of homologs to the meiosis I spindles (see Box 1).

Box 1: Attachments and tension are the keys to chromosome segregation

Why is recombination needed for accurate meiosis I chromosome segregation? To answer this question, we borrow an analogy put forth by Kim Nasmyth1. Two blind men each purchase eight pairs of socks, each with a different pattern. Accidentally both sets of socks end up in the same bag. What do the two men have to do to each receive an identical set of socks? The key to this riddle lies with the fact that new pairs of socks are attached through a plastic staple. Each man simply grabs one sock of the pair and pulls until the staple breaks and then keeps one sock from each pair. If this exercise is completed properly each man will hold a bag with an identical complement of socks.

Cells employ a similar mechanism to segregate sister chromatids in mitosis and at meiosis II. If we think of the socks as sister chromatids, the plastic staples as cohesin complexes, and the blind men as spindles, with the point of contact between their hand and the sock behaving like a centromere, the situation is almost identical to that described above. Meiosis I, however, is more complex, as homologous chromosomes are not adjacent to each other early in meiosis and are not “stapled” together. Meiotic cells address this problem by bringing homologs together through pairing, and attaching the homologs through chiasmata resulting from recombination.

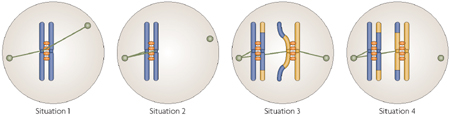

To segregate chromosomes accurately during mitosis and meiosis, cells must avoid these four possible situations, as shown in the figure below:

Attachment of a single sister chromatid to both poles in mitosis or meiosis II (shown for mitosis, with one homolog in blue, the spindles are shown in green).

Attachment of both sister chromatids of a homolog to the same pole in mitosis or meiosis II (shown for mitosis, with one homolog in blue).

Attachment of sister chromatids of a homolog to opposite poles in meiosis I (shown for meiosis I, with one pair of homologs in blue and yellow)

Attachment of both homologs of a bivalent to the same pole in meiosis I (shown for meiosis I, with one pair of homologs in blue and yellow)

Situation 3 is avoided by use of co-orientation factors. Situations 1, 2, and 4 manifest themselves in the lack of effective tension on the spindle. At least in budding yeast Aurora B kinase senses this lack of tension by an unknown mechanism and in response, promotes disruption of incorrect spindle attachments (reviewed for mitosis by 108). This leads to activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC). The SAC senses unattached kinetechores and, in their presence, does not allow activation of Separase and the corresponding cleavage of cohesins, resulting in inhibition of chromosome segregation (reviewed in mitosis in 63 and 64, 65). In a sense, Aurora B simply gives the cell another chance to get it right. If the cell attaches chromosomes inappropriately another time, Aurora B will again be needed to reset microtubule-kinetechore attachments.

The mechanism by which Aurora B severs faulty microtubule - kinetochore attachments has recently been illuminated through biochemical, genetic and electron microscopic strategies. Improper microtubule-kinetochore geometry causes Aurora B to phosphorylate the kinetochore protein Dam1, which mediates centromere-microtubule attachment. Phosphorylated Dam1 can then no longer support proper assembly of microtubules, resulting in loss of microtubule-kinetochore attachments. 109-112. Aurora B and the factors involved in SAC are well conserved across species, highlighting the central importance of these factors to the basic chromosome segregation mechanism in mitosis and meiosis 15, 86, 108, 113-117.

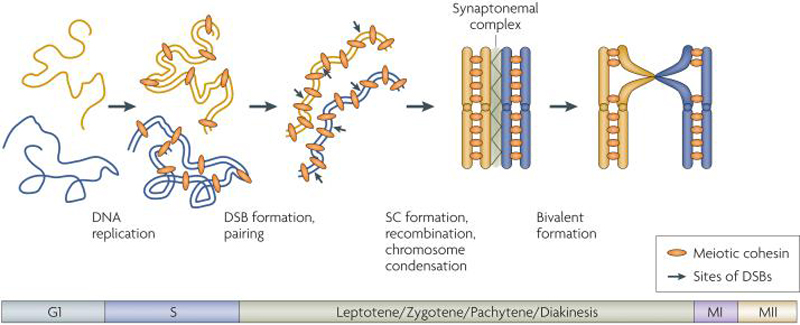

The linking of homologous chromosomes depends on a process known as “homolog pairing”. In pairing, homologs initially align at a distance of 300 nm 106. During prophase, this distance between homologs decreases, culminating in synapsis, the state of the tightest association, with homologs fully aligned and 100 nm apart 106. Pairing is often accompanied by and mechanistically intertwined with homologous recombination, which is necessary for creating physical linkages between homologous chromosomes (Figure 3; reviewed in 3, 27).

Figure 3. Chromosome morphogenesis in meiotic prophase.

Upon entry into meiosis, chromosomes are decondensed and homologs are not associated. Shortly after cells enter the meiotic program, chromosomes undergo DNA replication, during which sister chromatids are created and linked through cohesin complexes. Following DNA replication, during stages known as Leptotene and Zygotene, a number of events occur concomitantly: chromosomes begin to condense, double-strand breaks (DSBs) are formed throughout the genome, and homologous chromosomes associate through pairing. Paired homologs then undergo recombination and Synaptonemal Complex (SC) assembly, which is completed during pachytene stage as chromosomes reach a maximal level of condensation. In late prophase, in a stage known as diakinesis, homologs are attached through chiasmata to form bivalents, which will align at the center of the nucleus at metaphase I and serve as the basis for meiosis I reductional segregation. Note that for simplicity, only a single pair of homologs is pictured here. For reviews of early prophase processes, see 27, 30, 106

Pairing is one of the great accomplishments of evolution. Sometimes between the completion of DNA replication and linkage of homologs through recombination, in a process that occurs with reproducible timing in all meiotic organisms, paired homologs emerge from the relatively disorganized mass of DNA present in the early meiotic nucleus (Figure 3; 27). This is a particularly astounding task in complex organisms, such as humans, with enormous genomes and large tracts of repetitive regions. How do they do it? Unfortunately, little is known about pairing mechanism. A major reason for the lack of progress in meiotic pairing research is likely due to temporal and apparently mechanistic linkage between pairing and recombination. In many organisms, such as budding, fission yeast and mammals, the first step of recombination, double strand break (DSB) formation, is also necessary for pairing to occur 28-30. A further level of complexity of pairing research arises from variations in pairing mechanisms between organisms. In humans and budding yeast, pairing is almost entirely dependent on the early steps of recombination, while in other organisms, such as D. melanogaster, pairing is entirely independent of recombination (reviewed in 31). Despite these difficulties, recent research has aided in the elucidation of the earliest pairing step, with a mechanism that implicates centromere interactions in this process.

Distributive segregation and early steps in homologous pairing rely on the centromere

Recent insights into the early stages of homolog pairing and the role of centromeres in this process came from research on a type of segregation that is not necessarily associated with recombination. Distributive segregation is employed in many, if not all, organisms as a backup mechanism to facilitate segregation of chromosomes that were not linked through homologous recombination and hence lack chiasmata, the physical manifestations of recombination 32, 33. In yeast, the phenomenon was first documented by Guacci and Kaback, who observed that diploid budding yeast cells that carry only one copy of chromosome 1 and 3 (instead of two) segregate these two lone chromosomes from each other with approximately 90% efficiency despite a lack of homology between these two chromosomes that results in no recombination between them 33. Work from Dean Dawson's lab expanded these studies using homeologous chromosomes. This group constructed diploid S. cerevisiae strains with only a single copy of chromosome 5. In place of the missing homolog, this group substituted the homeologous chromosome from the closely related species S. carlsbergensis. These two yeast species are too highly divergent to undergo recombination, yet surprisingly, S. cerevisiae chromosome 5 segregated to the opposite pole from S. carlsbergensis chromosome 5 over 90% of the time 34.

It is likely that the mechanism of distributive segregation is based on non-homologous chromosome associations that appear to occur early during homologous pairing in wild-type cells. Shirleen Roeder and colleagues found that during early prophase Zip1, a protein required for full homolog pairing 35 localizes to 16 discrete foci (Figure 4). This is striking given that diploid budding yeast has 32 chromosomes. Each focus represents the associated centromeres of two chromosomes (which themselves consist of two sister chromatid pairs). These associations between centromeres are dynamic and initially largely non-homologous 36. Thus it appears that in early prophase, before homolog pairing is underway, cells are testing partners by coming together at centromeres, then reiteratively switching partners. It is likely that in Dawson's homeologous chromosome experiments 34, the divergent chromosomes ended up coupled to each other at their centromeres when the homologous chromosomes became linked through chiasmata, thus allowing the positioning of homeologous chromosomes opposite each other on the meiosis I spindle. Indeed, Dawson's group found that homeologs associate specifically at their centromeres prior to meiosis I segregation. Further, when a competing centromere was introduced on a plasmid, it was sufficient to disrupt centromere associations between homeologous chromosomes and their proper segregation 37. Centromere coupling does not impart the specificity of interaction that is essential for precise alignment of homologs. It is instead likely that centromere coupling brings possible homologs into rough alignment, where unknown mechanisms that depend on DSBs result in locking of a homologous pairing or dissociation of a non-homologous pairing.

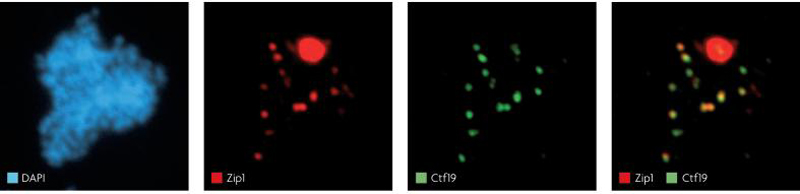

Figure 4. Centromere clustering in prophase in budding yeast.

This figure shows a S. cerevisiae cell with 16 centromeric foci, each consisting of two chromosomes (with two sister chromatids each) in early prophase. Centromeres are visualized through the kinetochore component Ctf19 (green) and SC component Zip1 (red). The large, irregular focus in the Zip1 channel is a polycomplex, a non-DNA associated complex of unassembled SC components. The cell shown is defective in recombination to prevent formation of recombination-dependent Zip1 foci that represent a separable function of Zip1. The images are generously supplied by Shirleen Roeder and are reprinted with permission from Science 36.

In Drosophila melanogaster females, a mechanism similar to S. cerevisiae centromere coupling appears to be solely responsible for pairing of chromosome IV. This chromosome, the smallest in the D. melanogaster genome, does not undergo meiotic recombination. Nevertheless, D. melanogaster properly segregates all of their chromosomes at meiosis I with an equivalent degree of accuracy seen in more conventional chiasmic meioses 31, 32, 38, 39. This type of achiasmic segregation appears to be the result of a tight association of Drosophila chromosomes at distinct heterochromatic regions 39-41. The heterochromatin surrounding the centromere is largely responsible for achiasmic segregation in Drosophila, as deletion of these regions on one of two mini-chromosomes results in a dramatic increase in meiosis I chromosome mis-segregation 42. S. cerevisiae does not have classical heterochromatin. Centromeres, however, show some similar characteristics to heterochromatin of other organisms, particularly in their altered histone composition in this region 18, 43, 44. Thus it is possible that early meiotic centromere coupling in budding yeast is mechanistically related to heterochromatin-mediated pairing in flies. It is also possible that the distributive segregation mechanism represents an ancestral meiotic segregation system that is an effective means of promoting chromosome segregation in organisms with few chromosomes, but was eventually replaced in most instances by the more efficient recombination-based homolog segregation mechanism seen widely today.

Pairing centers in nematodes: a separation of centromere function?

Caenorhabditis elegans does not have traditional centromeres. Instead, microtubules may interact with chromosomes at any point throughout their entire length during mitosis. During meiosis I and meiosis II, however, chromosome - microtubule interactions are restricted to specific genomic regions, thus resembling more traditional centromeres (reviewed in 45). The sites of microtubule interaction, however, do not appear to be involved in homolog pairing, but each C. elegans chromosome contains a separate region, called the “pairing center” where homolog pairing and synapsis are initiated 46-48. There, sequence-specific DNA binding proteins mediate homolog interactions by mechanisms that remain to be elucidated 46, 49, 50. These findings raise the interesting possibility that in the roundworm, different centromeric functions might be delegated to distinct loci during meiosis, with one genomic region mediating the centromere's microtubule attachment function, whereas another region mediates its homolog pairing role.

Evidence for centromere-mediated pairing in multiploids

Studies of multiploid meiosis suggest that centromeres and heterochromatic regions are not only important for promoting homolog alignment, they also play a role in excluding the association of homeologous chromosomes. The Ph1 locus of wheat was the first genomic region implicated in chromosome pairing in any organism 51-53. The locus is necessary to favor meiotic pairing of homologs over homeologs by regulating chromatin structure through an unknown mechanism, drawing interesting parallels to Drosophila and C. elegans pairing and S. cerevisiae centromere coupling 54, 55. The Ph1 locus is estimated to be somewhere between 2.5 Mb and 450 Mb in size 54, 56. It is still unclear which genes within this region are important for Ph1 activity, though the size of the region has led to speculation that multiple genes contribute to the pairing effects promoted by this locus. Interestingly, Ph1 activity correlates with a distinct centromeric structure. Wheat varieties that exhibit a high level of homeologous pairing also lack Ph1, and their centromeres appear cytologically diffuse. In contrast, wheat varieties with an intact Ph1 locus and low homeologous pairing show cytologically dense, well-defined centromere structures 57, 58.

Hexaploid wheat, with 42 diploid chromosomes, additionally use a centromere coupling mechanism early in meiosis that appears to be very similar to that described in budding yeast. Here, however, centromeres begin meiosis associated in seven distinct groups upon meiotic entry, representing seven sets of homologous and homeologous chromosomes. As cells progress into meiosis, these groups are sorted into pairs of centromeres that represent homologous associations. The Ph1 locus affects the ability of cells to properly undergo the transition from centromere groups to homologous centromere pairs 59, 60.

Together, these cytological observations support a conserved link between chromatin structure, centromere function and pairing.

Centromeres facilitate the stepwise loss of cohesion

Replicated sister chromatids are held together by cohesin complexes, which are composed of four core subunits that associate in a ring-shaped structure. Cohesin is similar in mitosis and meiosis though some of the subunits are substituted for meiosis-specific variants (reviewed in 61, 62). Most prominent among them is the kleisin subunit. The substitution of the kleisin subunit by a meiosis specific form, called Rec8 in most organisms, allows a change in the manner in which cohesins are removed from chromosomes. In mitosis, cohesins are lost from chromosomes at the metaphase to anaphase transition, allowing chromosome segregation to occur (Figure 1A). In contrast, meiotic cells remove only the population of cohesin along chromosome arms in meiosis I, while retaining cohesion around centromeres until meiosis II (Figure 1B, Figure 5, reviewed in 61, 62).

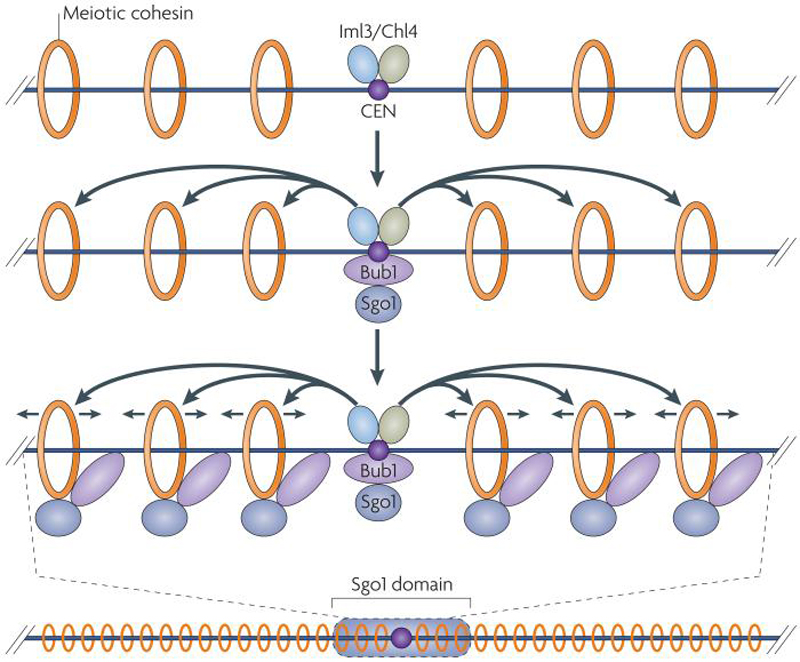

Figure 5. A model for the establishment of a protected domain of centromeric cohesion in budding yeast.

The Sgo1-Bub1 complex, the protector of centromeric cohesion, is recruited to the core centromere by unknown mechanisms. Once at the centromere, kinetochore components including Iml3, Chl4, and centromere- proximal cohesins promote spreading of Sgo1 to pericentric regions. Sgo1 eventually occupies a domain that spans 50 kilobases around budding yeast centromeres, fully coinciding with the region of cohesion that is protected from removal during meiosis I. Note that cohesins are not anchored but rather are able to move along chromosomes, as depicted by arrows on either side of cohesin rings 107.

A protease known as Separase removes cohesins from chromosomes. During mitosis, Separase cleaves the kleisin subunit along the entire length of the chromosomes to bring about anaphase chromosome movement (Figure 1A). A surveillance mechanism known as the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) prevents Separase from activation by stabilizing the Separase inhibitor Securin. The SAC does not allow cohesin cleavage and subsequent chromosome segregation until all chromosomes achieve bi-orientation on the mitotic spindle, that is kinetochores are attached to microtubules emanating from opposite poles and are under tension (see Box 1; reviewed in mitosis by 63-65).

During meiosis I, bivalents align on the meiosis I spindle. At this stage, it is the cohesins distal to the chiasmata that hold homologous chromosomes together and provide the resistance to the pulling force necessary for correct alignment of bivalents on the meiosis I spindle (Figure 1B; Box 1). Until this occurs, the SAC holds cells in metaphase I. Once all bivalents are correctly attached, the SAC is silenced and allows cleavage of cohesin complexes located along chromosome arms. The loss of this population of cohesins allows homologs to move to opposite ends of the anaphase I spindle. The simultaneous retention of cohesins around centromeres prevents sister chromatids from separating prematurely and, in a manner similar to mitosis, allows sister chromatids to attach to and be segregated by the meiosis II spindle with accuracy 65, 66. How does the cell differentially regulate cohesins on chromosome arms and around the centromeres? We now know that key components in this process associate with kinetochores, and that cells establish a large domain around the core centromere that mediates protection of centromere-proximal sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I.

Mechanisms of cohesin protection

Retention of centromere-proximal cohesion involves a number of kinetochore-localized factors. MEI-S332, a kinetechore-localized protein in D. melanogaster, was the first of these factors shown to be required for stepwise loss of cohesion. Recently, homologs have been identified in other organisms as well, where it is known as Sgo1 61-68. Sgo1 associates with pericentric regions and is essential for the maintenance of Rec8 at these locations beyond anaphase I 67. Sgo1 appears to protect Rec8 from meiosis I cleavage partially through recruitment of the phosphatase PP2A to centromere-proximal cohesins 68, 69. This finding is intriguing in light of evidence that Rec8 is highly phosphorylated and that such phosphorylation may promote its cleavage. Depletion of the polo kinase Cdc5 results in hypo-phosphorylated Rec8 and a delay in Rec8 cleavage 70. Furthermore, mutation of in vivo Rec8 phosphorylation sites leads to a defect in arm cohesin cleavage in meiosis I 71. These data support a model in which PP2A localization to centromeric regions results in dephosphorylation of centromere-proximal Rec8, thus inhibiting cleavage specifically in this region and resulting in stepwise cohesion loss.

Establishment of a cohesin protective domain

Genome wide location analyses have been used to identify the regions on chromosomes where Rec8 is protected from removal during meiosis I. In budding yeast, Kiburz et al. (2005)24 found that metaphase II arrested cells retained Rec8 in an approximately 50 kilobase domain around each centromere. Furthermore, they showed that Sgo1 localizes precisely in the same locations where cohesins are enriched within this 50 kilobase domain 12, 72. Most remarkably however, this study showed that the 120 bp point centromere was sufficient to establish an approximately 50 kb cohesin protective domain around itself during meiosis I. Integration of the 120 bp centromere at a new site on chromosome arms was sufficient to recruit Sgo1 to a 50 kb domain surrounding the new centromere. This result indicated that the centromere, and presumably the kinetochore that it recruits, are capable of creating an epigenetic domain around it that influences the pattern of chromosome segregation. How this is accomplished remains to be determined, but the finding that in cells lacking the kinetochore components Iml3 or Chl4 or the cohesin subunit Rec8, Sgo1 associates with the 120 bp centromere but not the 50 kb region surrounding the centromere, raises the possibility that the centromere functions as a loading site from which the cohesin protective domain spreads (Figure 5; 24, 70).

In S. pombe and higher eukaryotes, the region surrounding the centromere is heterochromatic in nature and in these systems it appears that factors important for the establishment of heterochromatin are involved in establishing the cohesin protective domain. In fission yeast, recruitment and maintenance of cohesin complexes to pericentromeric heterochromatin depends on the heterochromatin establishment factors Swi6 and Clr4 and is essential for the persistence of centromeric cohesion throughout meiosis I. Retention of cohesin complexes at the central core of the fission yeast centromere, however, is independent of Clr4 or Swi6, suggesting that cohesin complexes localize to centromeres and pericentromeric regions through different mechanisms 73.

Recent work in mammalian cells indicates that the Clr4 and Swi6 homologs, Suv39h and HP1, are not involved in either enrichment or retention of centromeric cohesion, leaving the factors responsible for establishment of the centromeric cohesin domain a mystery 74. In Drosophila, the kinetochore itself appears dispensable for maintaining cohesins around centromeres beyond meiosis I, but pericentric sites are important for this function. MEI-S332 localization depends on functional centromeric chromatin but is separable from kinetochore assembly 75. Fission yeast and mammalian cells additionally contain an Sgo1 paralog, Sgo2. In S. pombe, Sgo2 is only expressed in vegetative cells and is not involved in meiotic protection of centromeric cohesion, while in mammalian cells Sgo2 is expressed more highly than Sgo1 in oocytes and appears to play the major role in meiotic centromeric cohesion protection in these cells 67, 76. Maize, like budding yeast, has a single Sgo1 homolog, which is meiosis-specific and is responsible for cohesion protection at meiosis I 77. Despite variations among organisms in the details of Sgo expression and the establishment of the protected centromeric cohesive domain, the remarkable conservation of Sgo1-like molecules and Rec8 from yeast to plants to mammals indicates a well-conserved general mechanism of meiotic cohesin regulation that relies heavily on centromere function.

Centromeres in sister kinetochore co-orientation

Chiasmata and the cohesins distal to chiasmata are not sufficient to direct homolog segregation during anaphase I. For each chromosome to segregate apart from its homolog, its sister kinetochores must also be coordinated to move together to the same pole. If sister kinetochores were attached to microtubules emanating from opposite spindle poles in meiosis I, as they do in mitosis and meiosis II, kinetochores would be under tension and hence cohesin removal on chromosome arms would take place, but chromosomes would not be able to move apart. All four sisters would remain in the center of the nucleus, with centromeric cohesion opposing spindle forces. To ensure sister chromatids segregate to the same pole in meiosis I, mechanisms are in place to co-orient sister kinetochores (reviewed in 3). Once co-orientation is achieved and sister kinetochores operate as one, the traditional tension based mechanisms can be employed to bi-orient homologous chromosomes on the meiosis I spindle.

Electron microscopy indicates that in budding yeast only one microtubule mediates attachment of each homolog to the meiosis I spindle 78, but it is not clear whether two sister kinetochores are fused to create a single functional kinetochore or whether the kinetochore of one sister is blocked from association with microtubules. Cytological observations in several other species suggest that sister kinetochores are fused into a single unit during meiosis I at the time of microtubule attachment, but they resolve into two distinct structures prior to the onset of anaphase I chromosome segregation 79, 80. The molecular basis for sister kinetochore co-orientation is just beginning to be understood, with studies implicating kinetochore structures as docking sites for signaling components involved in this process.

The monopolin complex facilitates sister kinetochore co-orientaton in S. cerevisiae

A major breakthrough in the understanding of sister kinetochore co-orientation came with the identification of the three proteins Mam1, Lrs4 and Csm1 in budding yeast, which together form the “monopolin complex” 81, 82. In the absence of the monopolin complex, chromosomes attach to the meiosis I spindle as they do in mitosis and meiosis II, with sister kinetochores capturing microtubules emanating from opposite spindle poles. This leads to a peculiar phenotype. Sister kinetochores are bi-oriented on the meiosis I spindle, but cannot segregate because centromeric cohesion prevents sister chromatids from segregating during meiosis I. Other meiotic events, such as meiosis I spindle disassembly, meiosis II spindle pole body duplication and reformation of the meiosis II spindle, however, continue uninterrupted. During meiosis II then, bivalents reattach to the meiosis II spindle with chromosomes now interacting with microtubules emanating from all four spindle poles. The division that ensues leads to a meiotic catastrophe, with most of the spores that arise from this division being inviable 82.

Mam1 is a meiosis -specific protein that associates with kinetochores during prophase I, while Csm1 and Lrs4 are expressed during both mitosis and meiosis. During mitosis, the two proteins reside in the nucleolus until anaphase, when they are released and spread throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm 81-83. During the meiotic cell division, Csm1 and Lrs4 leave the nucleolus earlier, during prophase when they associate with kinetochores, together with Mam1. These results indicate that a monopolin complex forms at kinetochores specifically during meiosis I and suppresses the bi-orientation of sister kinetochores.

Monopolin complex localization is regulated by at least two protein kinases; the Polo kinase Cdc5 and the conserved protein kinase Cdc7 70, 84, 85. Cdc7 is required for Mam1 to associate with kinetochores 84; Cdc5 for Lrs4 and Csm1 to leave the nucleolus during G2 and for the monopolin complex to associate with kinetochores 70, 85. Recently, it has been shown that release of Lrs4/Csm1 and the presence of Mam1 are in fact sufficient for sister kinetochore co-orientation. 86 Monje-Casas and colleagues (2007)86 showed that overexpression of Cdc5 during mitosis is capable of promoting the release of Lrs4 and Csm1 from the nucleolus early in the cell cycle. When such cells also express MAM1, kinetochores co-segregate to the same pole in a manner that depends on Lrs4 and Csm1. The meiosis-specific factor Spo13 is dispensable for sister kinetochore co-orientation in this system. During meiosis however, Spo13 is necessary for maintenance of the monopolin complex at kinetochores. In its absence, monopolins initially associate with kinetochores but dissociate from the structure prematurely 87, 88.

How do monopolins bring about sister kinetochore co-orientation? The monopolin complex appears to physically hold sister chromatids together at their centromeres independently of cohesins, perhaps using this role to influence the relative position of the two kinetochores to each other and restricting movement of sister kinetochores with respect to each other 86. Monopolins also recruit the Casein Kinase Hrr25 to kinetochores, where the association of Hrr25 with Mam1, as well as its kinase activity, are necessary for sister kinetochore co-orientation to occur 89. One of the targets of Hrr25 is the cohesin subunit Rec8 in S. cerevisiae. In S. pombe, kinetochore geometry, the casein kinase and Hrr25 homolog CK1δ/ε, and Rec8 have also been shown to be essential for sister kineochore co-orientation 89. This raises the possibility that certain aspects of kinetochore orientation are conserved across species. Together, the budding yeast data support a model in which centromeres serve as signaling hubs in meiosis I, where integration of signals from a number of factors results in co-orientation.

Kinetochore geometry establishes sister kinetochore co-orientation in S. pombe

In S. pombe, sister kinetochore co-orientation is linked to cohesion regulation, as Rec8 plays an important role in both processes. Rec8 and the cohesin complex are however not sufficient for co-orientation, as haploid cells engineered to undergo meiosis do not establish co-orientation, even though Rec8 is assembled onto chromosomes 90. Co-orientation does, however, occur in these cells if they receive mating pheromone. This suggests that mating pheromone signaling, one of the events usually preceding meiosis, triggers expression of one or more genes required for sister kinetochore co-orientation in fission yeast. One such gene, moa1+, was identified as a factor that, when deleted, allowed haploid fission yeast cells carrying a mutation in cdc2 that produces largely inviable dyads, to form viable spores. This result and the localization of Moa1 at centromeres supports a model where Rec8 at the inner centromere together with the meiosis specific factor Moa1, generate a chromosomal geometry that restricts kinetochore movement and favors co-orientation of sister kinetochores. (Figure 6; 91).

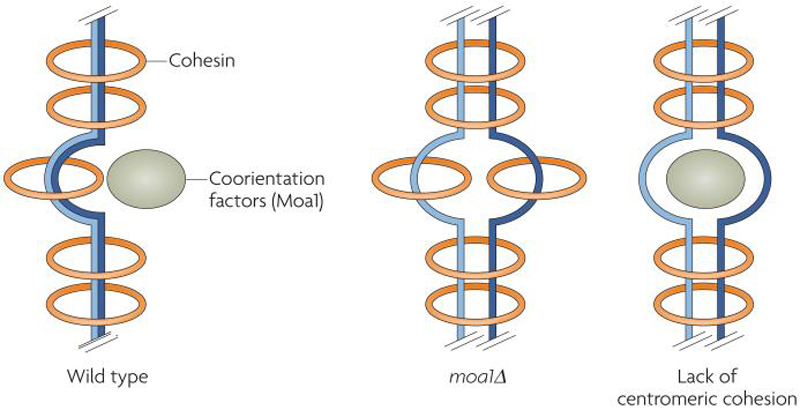

Figure 6. The role of kinetochore geometry in co-orientation in fission yeast.

In fission yeast, Moa1 and centromeric cohesion cooperate to co-orient sister chromatids at meiosis I. In the absence of Moa1 (moa1Δ), sister chromatids are not correctly aligned to allow cohesion between sister centromeres, resulting in bi-orientation and equational segregation at meiosis I. In the absence of centromeric cohesion (lack of centromeric cohesion), Moa1 cannot functionally co-orient sister kinetochores, indicating that centromeric cohesion is key to sister kinetochore co-orientation and that Moa1 acts primarily to promote proper placement of centromeric cohesins. This figure is based on figures and data from 91.

Factors such as the monopolins in budding yeast and Moa1 in fission yeast have not been identified in more complex eukaryotes. It is clear, however, that the role of centromeric cohesin complexes and chromosomal geometry are well-conserved, as rec8 mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana and Zea mays show sister chromatid bi-orientation in meiosis I 91, 92. It will be an important goal of future studies to identify additional factors in higher eukaryotes that are responsible for co-orienting sister chromatids during meiosis I.

Perspectives: Centromere defects in human disease

Errors in meiosis I chromosome segregation leading to aneuploidy are the primary cause of miscarriage and mental retardation (through Down's Syndrome) in humans 38, 93-95. Studies of the cause of aneuploidy in human gametes and embryos support a primary role for misplaced crossovers at meiosis I resulting in mis-segregation of homologs at this division (reviewed in 93). These misplaced crossovers include crossovers that are too close to chromosome ends (responsible for 80% of missegregation events), as well as those that result from recombination events in pericentric regions, areas which usually show repression of crossing over through mechanisms that are still poorly understood 96, 97. Centromere-proximal crossovers have been reported to be increased specifically in older mothers and are associated with trisomy 21, the cause of Down's Syndrome 96. The processes that normally repress crossing over near centromeres are just beginning to be elucidated, with recent work in budding yeast implicating centromeric Zip1 foci (which we have discussed earlier for their involvement in early pairing) in this phenomenon 98. Future research in this area will be essential to better understanding the causes of human trisomy.

The predominant segregation error resulting from centromere proximal crossing over is premature separation of sister chromatids (PSSC)99. Studies of human gametes rejected during in vitro fertilization procedures and the first polar bodies from isolated oocytes have suggested that PSSC is responsible for a large fraction of aneuploidies 100-102. PSSC has been suggested to occur as the result of a failure to maintain centromeric cohesion in meiosis I, indicating that the central role that centromeres are known to play in meiosis in model organisms is also important in mammalian meiosis 100, 103. Indeed, when mice are depleted for the meiosis-specific cohesin Smc1β, PSSC incidences are observed that increase dramatically with maternal age and largely phenocopy the etiology seen in humans, indicating a central role for cohesion regulation in human aneuploidy 104. Aneuploidy is seen in one-third of human miscarriages and 0.3% of live human births, with a marked increase in incidence as maternal age increases, highlighting the vital and timely nature of further research into the relationship between meiotic segregation machinery and human fertility and disease 94.

Future Directions

Meiotic chromosome segregation is not only a fundamentally fascinating and unique process, it is vital to fertility and human health. In this review we have discussed the surprising emergence of centromeres as central to several core mechanisms in meiosis. A number of questions have arisen as a result of some of the studies discussed here, which must be addressed to drive our understanding of meiosis forward. We will discuss just a sampling of these questions here.

First, we now know that centromeres can organize large chromatin domains with functional significance to meiotic segregation. The mechanisms by which these domains are established, however, remain mysterious. Greater temporal and spatial resolution of association of factors such as Sgo1 and Zip1 with chromosomes will informative in this goal. Recent work has resulted in unprecedented levels of synchrony of the meiotic divisions in budding yeast 105. Achievement of such levels of synchrony in earlier stages of meiosis could greatly facilitate these studies.

Whereas much work has begun to unravel the mechanisms of kinetechore co-orientation in meiosis I, this area is still rich with questions. Homologs of Mam1 and Moa1 have not yet been identified in more complex eukaryotes, suggesting that such factors remain to be discovered or that diverse mechanisms exist to achieve co-orientation. Moreover, though it seems that Mam1 and Moa1 act at least partially through direct geometric modification of kinetechore orientation, the basis for this is not understood. It will be important to supplement available genetic data with biochemical and microscopic strategies to further our understanding of co-orientation and kinetochore structure in meiosis I.

The most mysterious process in the study of basic meiotic mechanisms to date is pairing. We have discussed the potential role of centromere coupling in early pairing, but there is almost nothing known about the aspects of pairing that contribute to specificity of homolog interactions. The nature of the interactions between paired homolog is yet unknown, nor is the physical basis for the homology search that results in these paired homologs. It is likely that development and application of more advanced microscopic techniques, live cell imaging and more synchronous meiotic protocols will eventually unravel these mysteries.

Finally, it is vital for researchers to further address the impact of maternal age on meiotic chromosome segregation. For complex moral and ethical reasons, procurement of material for these studies has been difficult. As a result, most human fertility research thus far has focused on indirect read-outs of early meiotic mechanisms. Establishment of a model system in which to probe the effects of long-term meiotic arrests like those that occur in human females will be necessary to definitively address this increasingly important phenomenon to human fertility and public health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Andreas Hochwagen and members of the Amon lab for critical reading of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Shirleen Roeder for generously providing us with the pictures shown in Figure 4. Work in the Amon lab is supported by NIH grant to A.A. A.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. G.A.B. is a recipient of an NSF predoctoral fellowship.

Glossary

- The mitotic cell division

The process by which cells divide during development and regeneration. During the mitotic cell cycle, cells first replicate their DNA, then segregate this genetic material equally to create two cells with identical DNA content to each other and to the precursor cell.

- The meiotic cell division

The process by which cells divide to produce spores in yeast and gametes in multicellular organisms. During the meiotic cell division process, cells first replicate their DNA, then segregate this genetic material in two separate stages to create four products, which each have half the genetic content of the precursor cell and are not generally genetically identical to each another.

- Centromeres

are the sites of kinetochore assembly.

- Kinetochore

Large protein complexes that assemble at centromeres and mediate attachment of chromosomes to microtubules as the basis for chromosome segregation.

- Spindle

The structure that segregates chromosomes in mitosis and meiosis. Spindles consist of arrays of microtubules, some of which attach to chromosomes and some of which push cellular poles apart as cells progress through mitosis.

- Nucleosomes

Protein complexes that serve as DNA spools, contributing to the compaction of chromosomes. Several types of nucleosome exist, some of which mark specific chromosomal sites and serve as a basic unit of chromatin identity.

- Heterochromatin

Regions of highly compacted DNA. Heterochromatin frequently consists of repetitive DNA sequences.

- Sister chromatids

Chromosomes that are created through DNA replication. Two sister chromatids are, at least initially after DNA replication, identical in sequence.

- Homologous chromosomes (homologs)

Chromosomes from a given species that contain the same gene composition as each other, but are not usually identical. In a diploid organism, one homolog comes from “mom” and one from “dad” for each chromosome, with generally multiple polymorphisms present between the two.

- Homeologous chromosomes (homeologs)

Chromosomes with their origin in different species that usually contain the same basic gene composition as each other, but many sequence polymorphisms. Homeologs may be present in a species due to breeding, molecular engineering, or from natural hybridizations, as in some multiploid plant species.

- Pairing

The process by which homologous chromosomes find each other and align in meiotic prophase.

- Synapsis

The process by which the proteinaceous Synaptonemal Complex (SC) is assembled between chromosomes leading to the tight association between two chromosomes. Synapsis follows pairing, but is a distinct process and may be non-homologous under certain circumstances.

Biographies

Biographies

Angelika Amon is a Professor in the Department of Biology at MIT and an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. In her graduate work, Dr. Amon studied how the order of events of the cell cycle is established. In her own lab, she has characterized the mechanisms that govern accurate chromosome segregation during mitosis and meiosis, including notably identifying the importance and regulation of the conserved phosphatase Cdc14 to mitotic exit. Ongoing areas of interest in the Amon lab include the molecular regulation of mitotic and meiotic chromosome segregation, the consequences and significance of aneuploidy in yeast and mammals, and the relationship between aging and meiosis.

Gloria Brar completed her graduate work in the Amon lab, studying the regulation of meiotic cohesin removal, the role of cohesins in meiotic prophase, and the mechanism of meiotic pairing. Dr. Brar is now a postdoctoral scholar at UCSF in the lab of Jonathan Weissman, where she plans to apply computational and genome-wide analytical approaches to her continued studies of meiosis.

Footnotes

- Meiosis, the process by which haploid products are created from diploid precursors, is central to sexual reproduction.

- Meiosis can be thought of as a modified mitotic division, with notable modifications including pairing and attachment of homologs, co-orientation of sister kinetochores in meiosis I, and stepwise loss of cohesion.

- Centromeres, the sites of kinetochore assembly and microtubule attachment, vary widely in sequence and size among different organisms, but retain similar structural properties.

- Recent studies indicate that centromeres are central to meiotic chromosome segregation beyond their canonical role as the sites of spindle attachment.

- Centromeres act as chromosome organizers to promote pairing, in which non-homologous centromere coupling appears to serve as an early step.

- Centromeres organize a chromatin domain that is responsible for protection of centromeric cohesion in meiosis I.

- Centromeres serve as the basis for meiosis I sister kinetochore co-orientation.

- Errors in meiotic segregation in humans result in infertility and Down's syndrome. A portion of these errors results from centromere-proximal crossovers and premature loss of centromeric cohesion, pointing to defects in meiotic centromere function as a root cause of human disease and infertility.

References

- 1.Nasmyth K. Disseminating the genome: joining, resolving, and separating sister chromatids during mitosis and meiosis. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:673–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee B, Amon A. Meiosis: how to create a specialized cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:770–7. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marston AL, Amon A. Meiosis: cell-cycle controls shuffle and deal. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:983–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharp L. Introduction to Cytology. McGraw-Hill; New York and London: 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald-Hayes M, Clarke L, Carbon J. Nucleotide sequence comparisons and functional analysis of yeast centromere DNAs. Cell. 1982;29:235–44. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors determine a 25 bp sequence from budding yeast to be sufficient for plasmid segregation. This sequence is conserved between chromosomes. This study represents the first identification of a discrete centromere sequence.

- 6.Fitzgerald-Hayes M, Buhler JM, Cooper TG, Carbon J. Isolation and subcloning analysis of functional centromere DNA (CEN11) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome XI. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:82–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik HS, Henikoff S. Conflict begets complexity: the evolution of centromeres. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:711–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinkowski RP, Meyne J, Brinkley BR. The centromere-kinetochore complex: a repeat subunit model. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1091–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marschall LG, Clarke L. A novel cis-acting centromeric DNA element affects S. pombe centromeric chromatin structure at a distance. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:445–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh E, et al. Pericentric chromatin is organized into an intramolecular loop in mitosis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper utilizes an elegant microscopic strategy to reveal the looped structure of budding yeast centromeres, showing cohesins to be a major determinant of this structure.

- 11.Blat Y, Kleckner N. Cohesins bind to preferential sites along yeast chromosome III, with differential regulation along arms versus the centric region. Cell. 1999;98:249–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber SA, et al. The kinetochore is an enhancer of pericentric cohesin binding. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekwall K. Epigenetic control of centromere behavior. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:63–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wulf P, McAinsh AD, Sorger PK. Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2902–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.1144403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan GK, Liu ST, Yen TJ. Kinetochore structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:589–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheeseman IM, Desai A. Molecular architecture of the kinetochoremicrotubule interface. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:33–46. doi: 10.1038/nrm2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:379–93. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westermann S, Drubin DG, Barnes G. Structures and functions of yeast kinetochore complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:563–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.160607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volpe TA, et al. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 2002;297:1833–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1074973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall IM, et al. Establishment and maintenance of a heterochromatin domain. Science. 2002;297:2232–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1076466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleard F, Delattre M, Spierer P. SU(VAR)3-7, a Drosophila heterochromatin-associated protein and companion of HP1 in the genomic silencing of position-effect variegation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5280–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eskeland R, et al. The N-terminus of Drosophila SU(VAR)3-9 mediates dimerization and regulates its methyltransferase activity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3740–9. doi: 10.1021/bi035964s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiburz BM, et al. The core centromere and Sgo1 establish a 50-kb cohesin-protected domain around centromeres during meiosis I. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3017–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.1373005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors use genome-wide location analysis to show the precise location of protected cohesins in Meiosis I, which coincides with Sgo1 localization and covers 50 Kb around each centromere. The authors also determine core centromeric sequences to be necessary and sufficient for assembly of this protected domain.

- 25.Megee PC, Koshland D. A functional assay for centromere-associated sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 1999;285:254–7. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Megee PC, Mistrot C, Guacci V, Koshland D. The centromeric sister chromatid cohesion site directs Mcd1p binding to adjacent sequences. Mol Cell. 1999;4:445–50. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKee BD. Homologous pairing and chromosome dynamics in meiosis and mitosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:165–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keeney S, Neale MJ. Initiation of meiotic recombination by formation of DNA double-strand breaks: mechanism and regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:523–5. doi: 10.1042/BST0340523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitby MC. Making crossovers during meiosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1451–5. doi: 10.1042/BST0331451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zickler D, Kleckner N. The leptotene-zygotene transition of meiosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:619–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawley RS, Theurkauf WE. Requiem for distributive segregation: achiasmate segregation in Drosophila females. Trends Genet. 1993;9:310–7. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90249-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grell RF. Distributive Pairing: The Size-Dependent Mechanism for Regular Segregation of the Fourth Chromosomes in Drosophila Melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;52:226–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guacci V, Kaback DB. Distributive disjunction of authentic chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1991;127:475–88. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maxfield Boumil R, Kemp B, Angelichio M, Nilsson-Tillgren T, Dawson DS. Meiotic segregation of a homeologous chromosome pair. Mol Genet Genomics. 2003;268:750–60. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0796-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peoples-Holst TL, Burgess SM. Multiple branches of the meiotic recombination pathway contribute independently to homolog pairing and stable juxtaposition during meiosis in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 2005;19:863–74. doi: 10.1101/gad.1293605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsubouchi T, Roeder GS. A synaptonemal complex protein promotes homology-independent centromere coupling. Science. 2005;308:870–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1108283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemp B, Boumil RM, Stewart MN, Dawson DS. A role for centromere pairing in meiotic chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1946–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.1227304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study uses budding yeast strains that have been engineered to carry homeologous copies of chromosome 5 as a model to investigate distributive segregation. The authors find that centromere association of the homeologs precedes and is required for their proper segregation in meiosis I.

- 38.Koehler KE, Hawley RS, Sherman S, Hassold T. Recombination and nondisjunction in humans and flies. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5 Spec No:1495–504. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.supplement_1.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawley RS, et al. There are two mechanisms of achiasmate segregation in Drosophila females, one of which requires heterochromatic homology. Dev Genet. 1992;13:440–67. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020130608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fung JC, Marshall WF, Dernburg A, Agard DA, Sedat JW. Homologous chromosome pairing in Drosophila melanogaster proceeds through multiple independent initiations. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:5–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiraoka Y, et al. The onset of homologous chromosome pairing during Drosophila melanogaster embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:591–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karpen GH, Le MH, Le H. Centric heterochromatin and the efficiency of achiasmate disjunction in Drosophila female meiosis. Science. 1996;273:118–22. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalal Y, Furuyama T, Vermaak D, Henikoff S. Structure, dynamics, and evolution of centromeric nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15974–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707648104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kusch T, Workman JL. Histone variants and complexes involved in their exchange. Subcell Biochem. 2007;41:91–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maddox PS, Oegema K, Desai A, Cheeseman IM. "Holo"er than thou: chromosome segregation and kinetochore function in C. elegans. Chromosome Res. 2004;12:641–53. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036588.42225.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacQueen AJ, et al. Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;123:1037–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villeneuve AM. A cis-acting locus that promotes crossing over between X chromosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1994;136:887–902. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKim KS, Peters K, Rose AM. Two types of sites required for meiotic chromosome pairing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;134:749–68. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips CM, et al. HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell. 2005;123:1051–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Phillips CM, Dernburg AF. A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2006;11:817–29. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riley R, Chapman V. Genetic control of the cytologically diploid behaviour of hexaploid wheat. Nature. 1958;182:713–715. [Google Scholar]; The authors perform crosses of various wheat lines, identifying a general homeologous pairing restriction activity that correlates with monosomy for a particular chromosome, later identified as chromosome 5.

- 52.Wall AM, Riley R, Gale MD. The position of a locus on chromosome 5B of Triticum aestivum affecting homeologous meiotic pairing. Genet. Res. 1971;18:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gill KS, Gill BS. A DNA fragment mapped within the submicroscopic deletion of Ph1, a chromosome pairing regulator gene in polyploid wheat. Genetics. 1991;129:257–9. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffiths S, et al. Molecular characterization of Ph1 as a major chromosome pairing locus in polyploid wheat. Nature. 2006;439:749–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prieto P, Moore G, Reader S. Control of conformation changes associated with homologue recognition during meiosis. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111:505–10. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-2040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidhu GK, Rustgi S, Shafqat MN, von Wettstein D, Gill KS. Fine structure mapping of a gene-rich region of wheat carrying Ph1, a suppressor of crossing over between homoeologous chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5815–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800931105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aragon-Alcaide L, et al. Association of homologous chromosomes during floral development. Curr Biol. 1997;7:905–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aragon-Alcaide L, Reader S, Miller T, Moore G. Centromeric behaviour in wheat with high and low homoeologous chromosomal pairing. Chromosoma. 1997;106:327–33. doi: 10.1007/s004120050254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martinez-Perez E, Shaw P, Aragon-Alcaide L, Moore G. Chromosomes form into seven groups in hexaploid and tetraploid wheat as a prelude to meiosis. Plant J. 2003;36:21–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez-Perez E, Shaw P, Moore G. The Ph1 locus is needed to ensure specific somatic and meiotic centromere association. Nature. 2001;411:204–7. doi: 10.1038/35075597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. The structure and function of SMC and kleisin complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:595–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uhlmann F. Chromosome cohesion and separation: from men and molecules. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R104–14. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu H. Regulation of APC-Cdc20 by the spindle checkpoint. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:706–14. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00382-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen RH. Dual inhibition of Cdc20 by the spindle checkpoint. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:475–9. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shonn MA, McCarroll R, Murray AW. Requirement of the spindle checkpoint for proper chromosome segregation in budding yeast meiosis. Science. 2000;289:300–3. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Craig JM, Choo KH. Kiss and break up--a safe passage to anaphase in mitosis and meiosis. Chromosoma. 2005;114:252–62. doi: 10.1007/s00412-005-0010-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kitajima TS, Kawashima SA, Watanabe Y. The conserved kinetochore protein shugoshin protects centromeric cohesion during meiosis. Nature. 2004;427:510–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identify Sgo1 in fission yeast as the protein responsible for protecting centromeric cohesion during meiosis I. The authors further determine Sgo1 to have homologs in many organisms, including the Drosophila protein MEIS-332, long known to be important for centromeric cohesion.

- 68.Riedel CG, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A protects centromeric sister chromatid cohesion during meiosis I. Nature. 2006;441:53–61. doi: 10.1038/nature04664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tang Z, et al. PP2A is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1 and proper chromosome segregation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee BH, Amon A. Role of Polo-like kinase CDC5 in programming meiosis I chromosome segregation. Science. 2003;300:482–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1081846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brar GA, et al. Rec8 phosphorylation and recombination promote the step-wise loss of cohesins in meiosis. Nature. 2006;441:532–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eckert CA, Gravdahl DJ, Megee PC. The enhancement of pericentromeric cohesin association by conserved kinetochore components promotes high-fidelity chromosome segregation and is sensitive to microtubule-based tension. Genes Dev. 2007;21:278–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.1498707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kitajima TS, Yokobayashi S, Yamamoto M, Watanabe Y. Distinct cohesin complexes organize meiotic chromosome domains. Science. 2003;300:1152–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1083634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koch B, Kueng S, Ruckenbauer C, Wendt KS, Peters JM. The Suv39h-HP1 histone methylation pathway is dispensable for enrichment and protection of cohesin at centromeres in mammalian cells. Chromosoma. 2008;117:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lopez JM, Karpen GH, Orr-Weaver TL. Sister-chromatid cohesion via MEI-S332 and kinetochore assembly are separable functions of the Drosophila centromere. Curr Biol. 2000;10:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00650-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee J, et al. Unified mode of centromeric protection by shugoshin in mammalian oocytes and somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:42–52. doi: 10.1038/ncb1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hamant O, et al. A REC8-dependent plant Shugoshin is required for maintenance of centromeric cohesion during meiosis and has no mitotic functions. Curr Biol. 2005;15:948–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winey M, Morgan GP, Straight PD, Giddings TH, Jr., Mastronarde DN. Three-dimensional ultrastructure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiotic spindles. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1178–88. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Suja JA, de la Torre J, Gimenez-Abian JF, Garcia de la Vega C, Rufas JS. Meiotic chromosome structure. Kinetochores and chromatid cores in standard and B chromosomes of Arcyptera fusca (Orthoptera) revealed by silver staining. Genome. 1991;34:19–27. doi: 10.1139/g91-004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goldstein LS. Kinetochore structure and its role in chromosome orientation during the first meiotic division in male D. melanogaster. Cell. 1981;25:591–602. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rabitsch KP, et al. Kinetochore recruitment of two nucleolar proteins is required for homolog segregation in meiosis I. Dev Cell. 2003;4:535–48. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Toth A, et al. Functional genomics identifies monopolin: a kinetochore protein required for segregation of homologs during meiosis i. Cell. 2000;103:1155–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors use a clever genetic strategy, combined with genome-wide transcription analyses, to identify Mam1, a protein central to co-orientation of sister kinetochores in budding yeast.

- 83.Huang J, et al. Inhibition of homologous recombination by a cohesin-associated clamp complex recruited to the rDNA recombination enhancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2887–901. doi: 10.1101/gad.1472706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lo HC, Wan L, Rosebrock A, Futcher B, Hollingsworth NM. Cdc7-Dbf4 Regulates NDT80 Transcription as well as Reductional Segregation during Budding Yeast Meiosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Clyne RK, et al. Polo-like kinase Cdc5 promotes chiasmata formation and cosegregation of sister centromeres at meiosis I. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:480–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Monje-Casas F, Prabhu VR, Lee BH, Boselli M, Amon A. Kinetochore orientation during meiosis is controlled by Aurora B and the monopolin complex. Cell. 2007;128:477–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee BH, Kiburz BM, Amon A. Spo13 maintains centromeric cohesion and kinetochore coorientation during meiosis I. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2168–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Katis VL, et al. Spo13 facilitates monopolin recruitment to kinetochores and regulates maintenance of centromeric cohesion during yeast meiosis. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petronczki M, et al. Monopolar attachment of sister kinetochores at meiosis I requires casein kinase 1. Cell. 2006;126:1049–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Watanabe Y. A one-sided view of kinetochore attachment in meiosis. Cell. 2006;126:1030–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yokobayashi S, Watanabe Y. The kinetochore protein Moa1 enables cohesion-mediated monopolar attachment at meiosis I. Cell. 2005;123:803–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identify the fission yeast sister kinetochore co-orientation factor, Moa1, which acts partially through collaboration with cohesins. The authors further establish the importance of centromeric cohesins in proper kinetochore orientation by forcing premature cleavage of centromeric Rec8 with a protease tethered to the core centromere region, resulting in cells that erroneously bi-orient sister kinetechores in meiosis I.

- 92.Chelysheva L, et al. AtREC8 and AtSCC3 are essential to the monopolar orientation of the kinetochores during meiosis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4621–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hassold T, Hunt P. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:280–91. doi: 10.1038/35066065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hunt PA, Hassold TJ. Sex matters in meiosis. Science. 2002;296:2181–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1071907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hunt PA, Hassold TJ. Human female meiosis: what makes a good egg go bad? Trends Genet. 2008;24:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sherman SL, Lamb NE, Feingold E. Relationship of recombination patterns and maternal age among non-disjoined chromosomes 21. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:578–80. doi: 10.1042/BST0340578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cherry JM, et al. Genetic and physical maps of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 1997;387:67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen SY, et al. Global Analysis of the Meiotic Crossover Landscape. Dev Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rockmill B, Voelkel-Meiman K, Roeder GS. Centromere-proximal crossovers are associated with precocious separation of sister chromatids during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;174:1745–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]