Abstract

Glycoprotein B (gB), the most conserved protein in the family Herpesviridae, is essential for the fusion of viral and cellular membranes. Information about varicella-zoster virus (VZV) gB is limited, but homology modeling showed that the structure of VZV gB was similar to that of herpes simplex virus (HSV) gB, including the putative fusion loops. In contrast to HSV gB, VZV gB had a furin recognition motif ([R]-X-[KR]-R-|-X, where | indicates the position at which the polypeptide is cleaved) at residues 491 to 494, thought to be required for gB cleavage into two polypeptides. To investigate their contribution, the putative primary fusion loop or the furin recognition motif was mutated in expression constructs and in the context of the VZV genome. Substitutions in the primary loop, W180G and Y185G, plus the deletion mutation Δ491RSRR494 and point mutation 491GSGG494 in the furin recognition motif did not affect gB expression or cellular localization in transfected cells. Infectious VZV was recovered from parental Oka (pOka)-bacterial artificial chromosomes that had either the Δ491RSRR494 or 491GSGG494 mutation but not the point mutations W180G and Y185G, demonstrating that residues in the primary loop of gB were essential but gB cleavage was not required for VZV replication in vitro. Virion morphology, protein localization, plaque size, and replication were unaffected for the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus compared to pOka in vitro. However, deletion of the furin recognition motif caused attenuation of VZV replication in human skin xenografts in vivo. This is the first evidence that cleavage of a herpesvirus fusion protein contributes to viral pathogenesis in vivo, as seen for fusion proteins in other virus families.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV), an alphaherpesvirus, causes chicken pox (varicella) as a primary infection and shingles (zoster) upon reactivation from infected ganglia in humans (reviewed in reference 16). Although not yet investigated in VZV, herpesvirus entry requires fusion of the virus envelope with cell membranes governed by viral glycoprotein B (gB) and gH/gL, which are conserved across the family Herpesviridae (12, 27, 57). gB is the most conserved glycoprotein, with its function as a fusion protein well documented for several of the herpesviruses (10, 19, 38, 48, 51, 52).

Open reading frame 31 (ORF31) codes for the 931 amino acids of VZV gB (18, 37). The successive N- and O-linked glycosylation plus the sialation and sulfation of VZV gB yields a mature protein with a molecular mass of approximately 140 kDa (45). Upon maturation, gB is cleaved, presumably by cellular proteases, into two polypeptides of 66 and 68 kDa. Intracellular trafficking of gB was shown to be dependent upon amino acid motifs in the cytoplasmic domain (24-26). In transfection studies, gB was transported to the cellular surface where it was endocytosed and localized to the trans-Golgi, where envelopment of viral particles is thought to occur.

The structures of gB in the two human alphaherpesviruses, VZV and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), are likely to be very similar as they have 49% amino acid identity (reviewed in reference 16). The ectodomain of HSV-1 gB was shown to form a spike that consisted of trimers with the structural homology to gG of vesicular stomatitis virus (28). Heldwein et al. (28) proposed that HSV-1 gB is a class II fusion protein based on homology to VSV G. The herpesvirus gB monomer was divided into five domains, I to V. Domain I consisted of a continuous amino acid sequence that folded into a pleckstrin homology-like domain, while domain II was comprised of two discontinuous segments, which also had a pleckstrin homology-like domain. A loop region exposed to the exterior of gB connected domain II with domain III. Domain III was comprised of three discontinuous segments and connected to the external loop by a long α helix that ended in a central coiled coil. Domain IV crowned gB and was connected to domain V, which stretched from the top to the bottom of the gB monomer, forming the core of the trimer making contacts with the two other subunits. The structural homology and lack of furin cleavage suggest that the herpesvirus gB and VSV G proteins have undergone convergent evolution.

Although not proven experimentally, VZV gB is likely to be cleaved by the subtilisin-like proprotein convertase furin as the glycoprotein has a furin recognition motif [R]-X-[KR]-R-|-X (where | indicates the position at which the polypeptide is cleaved) (29). The [R]-X-[KR]-R-|-X motif is conserved in gBs for all of the herpesvirus families (5, 9, 21, 36, 40, 53, 63, 64). This site has been shown to be dispensable for the replication of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1), and pseudorabies virus (PRV) in vitro (32, 49, 58). Furin site mutants for BHV-1 and PRV show an altered phenotype in vitro, but effects were not examined in vivo. HSV-1 gB is not cleaved and lacks the [R]-X-[KR]-R-|-X motif at the canonical site, which is of interest because HSV-1 is genetically the most closely related human herpesvirus to VZV.

Domain I of HSV gB showed structural conservation of putative fusion loops similar to those found in domain IV of the VSV G protein (28). Despite the lack of conserved amino acids within these loops, the hydrophobicity of the residues appears to be conserved for the Herpesviridae (4). Substitution of hydrophobic residues in Epstein-Barr virus gB and linker insertion mutagenesis close to the putative fusion loops of HSV-1 gB abrogated fusion based on in vitro transfection studies (4, 22, 34). However, the effect of substitutions in these putative fusion loops on viral replication has not been characterized. Since the development of fusion assays for VZV has proven elusive, the effect of substitutions in the putative fusion loop using viral mutagenesis to make recombinant viruses provides an alternative approach for identifying functional residues in VZV gB.

In contrast to HSV-1, VZV is a human-restricted pathogen (reviewed in reference 16). To study the pathogenesis of VZV in vivo, well-established human xenograft models have been developed using SCID mice (6, 7, 13, 14, 41, 44, 54, 65). Lesions formed by VZV in the skin are similar to those seen in human subjects following primary infection (15, 43). The relevance of the model was demonstrated by studies with the varicella vaccine virus (vOka) that exhibited decreased growth in skin xenografts in vivo but does not cause disease in the healthy human host. In contrast, the vaccine virus and its parent strain, parental Oka (pOka), have indistinguishable replication kinetics in vitro (15, 43).

The present study was designed to investigate the effects of structure-based targeted mutations in VZV gB on viral replication in cultured cells and in human skin xenografts in the SCIDhu mouse model. This was performed in the context of infectious virus recovered using the self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the genome of a clinical isolate, Oka (62). The roles of the conserved residues W180 (gB-W180G) and Y185 (gB-Y185G) in the putative fusion loop were evaluated using glycine substitution, and the role of the furin recognition motif (491RSRR494) was assessed by a complete deletion of the furin motif (gBΔ491RSRR494) or a substitution of the arginine residues with glycine (gB491GSGG494) to conserve the carbon backbone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Melanoma cells were propagated in culture medium (modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [Gemini Bio-Products, Woodland, CA], nonessential amino acids [100 μM; Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA], penicillin G [100 U/ml; Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA], streptomycin [100 U/ml; Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA], and amphotericin [0.5 mg/ml; Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA]). Human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HELFs) were propagated in culture medium without nonessential amino acids. HEK 293 cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin G (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 U/ml). LoVo cells (ATCC number CCL-229) were propagated in F-12K medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin G (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 U/ml). LoVo cells have been characterized to show that the furin gene generates a truncated functionally defective form of the protein caused by an amino acid substitution preventing autocatalytic activation plus a frameshift leading to premature termination of the protein (60, 61).

Homology modeling.

The homology model of VZV gB was predicted by modeling against the known structure for HSV-1 gB (28) using Swiss-Model (3) via the ExPASy Web server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/).

Construction of pOka-BACs with mutations in ORF31[gB].

Mutagenesis was performed using the self-excisable pOka-BAC as described previously with modifications specific for ORF31[gB] (62). Briefly, mutagenesis primers for recombination (Δ491RSRR494, gB[31]-d491RSRR494_F and gB[31]-d491RSRR494_R; 491GSGG494, gB[31]-491GSGG494_F and gB[31]-491GSGG494_R; W180G, gB[31]-W180G_F and gB[31]-W180G_R; Y185G, gB[31]-Y185G_F and gB[31]-Y185G-R; repair of W180G, gB[31]-W180G-R_F and gB[31]-W180G-R_R; repair of Y185G, gB[31]-Y185G-R_F and gB[31]-Y185G-R_R) (Table 1) were used to amplify the Kanr gene from the pKANS vector using AccuPrime Pfx (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The PCR products were cloned into TOPO TA pCR4.0 after the addition of adenosine overhangs using recombinant Taq (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Clones were sequenced to determine that the VZV-specific sequences did not have any unexpected deletions or substitutions. The Kanr cassette flanked with the VZV sequences was amplified from the pCR4.0 vectors using short primers (Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494, gB[31]nt1431-1456F and gB[31]nt1495-1520R; W180G and the repair of W180G, gB[31]nt499-523F and gB[31]nt552-577R; Y185G and the repair of Y185G, gB[31]nt513-538F and gB[31]nt568-594R) to generate high yields of PCR product. PCR products were gel purified (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) and then used for recombination. After the Red recombination steps to insert the mutations and remove the Kanr cassette, BACs were purified using a large-construct kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). All purified BACs were digested with HindIII to ensure that the expected DNA fragments were present. In addition, BACs were sequenced directly across the sites of mutagenesis to ensure that unexpected deletions or substitutions were not present.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for the mutagenesis of ORF31 in the self-excisable pOka-BAC

| Primer use | Primer name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Furin site deletion | gB[31]-d491RSRR494-F | CACTAATCATTCACCACAAAAACACCCGACTCGAAATACCAGCGTGCCAGTTGAGTTGAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG |

| gB[31]-d491RSRR494-R | GTTATTGTTCTATTGGCACGCAACTCAACTGGCACGCTGGTATTTCGAGTCGGGTGTTCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG | |

| Furin site mutagenesis | gB[31]_491GSGG494_F | CACTAATCATTCACCACAAAAACACCCGACTCGAAATACCGGTTCCGGAGGAAGCGTGCAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG |

| gB[31]_491GSGG494_R | GTTATTGTTCTATTGGCACGCAACTCAACTGGCACGCTTCCTCCGGAACCGGTATTTCGCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG | |

| Amplification of | gB[31]nt1431-1456F | CACTAATCATTCACCACAAAAACACC |

| cloned product | gB[31]nt1495-1520R | GTTATTGTTCTATTGGCACGCAACTC |

| Fusion loop point mutations | gB[31]_W180G_F | GCGACGGTATATTACAAAGATGTTATCGTTAGCACGGCGGGGGCCGGAAGTTCTTATACGAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG |

| gB[31]_W180G_R | CATATCTATTAGTAATTTGCGTATAAGAACTTCCGGCCCCCGCCGTGCTAACGATAACATCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG | |

| gB[31]_Y185G_F | CAAAGATGTTATCGTTAGCACGGCGTGGGCCGGAAGTTCTGGTACGCAAATTACTAATAGATAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG | |

| gB[31]_Y185G_R | AATTGGTACCCTATCAGCATATCTATTAGTAATTTGCGTACCAGAACTTCCGGCCCACGCCGCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG | |

| Reversion of fusion loop point | gB[31]_W180G-R_F | GCGACGGTATATTACAAAGATGTTATCGTTAGCACGGCGTGGGCCGGAAGTTCTTATACGAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG |

| mutations | gB[31]_W180G-R_R | CATATCTATTAGTAATTTGCGTATAAGAACTTCCGGCCCACGCCGTGCTAACGATAACATCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG |

| gB[31]_Y185G-R_F | CAAAGATGTTATCGTTAGCACGGCGTGGGCCGGAAGTTCTTATACGCAAATTACTAATAGATAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG | |

| gB[31]_Y185G-R_R | AATTGGTACCCTATCAGCATATCTATTAGTAATTTGCGTATAAGAACTTCCGGCCCACGCCGCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG | |

| Amplification of | gB[31]nt499-523 | GCGACGGTATATTACAAAGATGTTAT |

| cloned product | gB[31]nt552-577 | CATATCTATTAGTAATTTGCGTATAA |

| gB[31]nt513-538 | CAAAGATGTTATCGTTAGCACGGCGT | |

| gB[31]nt568-594 | AATTGGTACCCTATCAGCATATCTATT |

Excision of the MiniF− vector from the pOka-BACs as determined by PCR and Southern blot analysis.

BAC-derived recombinant viruses were passed in HELFs until the MiniF− sequences Cat (P1/P2) and SopA (P3/P4) were not detectable by PCR as previously described (62). In addition, the primers gBseq005 and gBseq008 were used to detect ORF31 to determine the presence of virus. Southern blot analysis was performed as described previously (55). One microgram of control DNA; BACs pOka-Δ491RSRR494, pOka-491GSGG494, pOka-W180G, or pOka-Y185G; or 5 μg of genomic DNA was digested with 10 IU XmnI (New BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA). Probes to Cat, SopA, and ORF31 were generated by PCR using AccuPrime Pfx (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with oligonucleotides P1/P2 (Cat), P3/P4 (SopA probe), and gBseq005/gBseq008 (ORF31 probe) and labeled using the Gene Images AlkPhos direct labeling and detection system (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

gB expression vectors.

The pOka ORF31 plus Kozak sequence was cloned into the pCDNA3.1 mammalian expression vector. PCR was used to amplify ORF31 from the wild type and BACs containing the mutated ORF31 with primers 5′-ttaaagcttgccaccatgtccccttgtggctattat-3′ and 5′-ttactcgagtcattacacccccgttacattctcg-3′ using AccuPrime (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR products were TOPO TA cloned and sequenced to determine that unexpected deletions or substitutions were not present. Restriction endonucleases EcoRV/AgeI for Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 or HindIII/KpnI for W108G and Y195G were used to cut fragments from the mutated ORF31s that were TOPO TA cloned. The fragments were ligated into the pCDNA3.1-gB expression vector digested with either EcoRV/AgeI or HindIII/KpnI to generate pCDNA3.1-gB expression vectors carrying the Δ491RSRR494, 491GSGG494, W108G, or Y195G mutation.

Immunoprecipitation of gB from transfected or infected cells.

Cells were lysed with an extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris base [pH 8.8], 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40 plus an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche, CA) as described previously (20). Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to gB (MAb 158) (20) or gE (MAB8612; Millipore Biosciences, Temecula, CA) or no primary antibody was cross-linked to immobilized protein A (Pierce, Rockford, IL) as previously described (23). Precleared lysates were incubated overnight with bound antibodies, washed extensively, and then eluted into sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer by incubating the beads at 100°C for 3 min. Denatured samples were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and either the samples were silver stained (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) or Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (50). A rabbit polyclonal antiserum, 746-868, used to detect gB by Western blot analysis, was generated to the peptide sequence 833PEGMDPFAEKPNAT846 in the cytoplasmic region of pOka gB by GenScript Corp., Piscataway, NJ.

Protein identification by mass spectrometry.

Melanoma cells (105/cm2) were inoculated with pOka (3.0 log10 PFU/cm2), harvested 48 h postinfection, and gB immunoprecipitated as described earlier. Samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and proteins were visualized by silver staining. Bands were excised and digested with trypsin, and the proteins were identified using mass spectrometry performed by the Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University Mass Spectrometry (http://mass-spec.stanford.edu).

Confocal microscopy of transfected and infected cells.

Melanoma cells transfected with gB expression constructs were fixed 48 h posttransfection with 4% formaldehyde for 10 min. MAb SG2 (Meridian Life Sciences, Saco, ME) was used to stain for VZV gB, and primary antibodies to cellular proteins were used as markers for early endosomes (EEA-1; rabbit polyclonal antibody; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), multivesicular bodies (VPS4; goat polyclonal antibody; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), the trans-Golgi (TGN46; sheep polyclonal antibody; Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Confocal microscopy of melanoma cells infected with pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 was performed as described previously (6) using the primary antibodies to VZV proteins IE63 (rabbit polyclonal) and gB (MAb SG2) and nuclei (Hoechst 33342). In addition, confocal microscopy was performed with infected cells to show the localization of gB with the cellular markers EEA-1, VPS4, TGN46, and nuclei.

Replication kinetics and plaque sizes of the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 viruses in melanoma cells.

The kinetics of pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus replication were determined as described previously (50). Briefly, 106 melanoma cells were inoculated with log10 3.0 PFU of pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, or pOka-gB491GSGG494. Infected cells were harvested at 24-h intervals and titrated on melanoma cells. Titer plates fixed at 4 days postinoculation with 4% paraformaldehyde were stained by immunohistochemistry using a high-titer human VZV antiserum. Images of the plaques were captured, and then the outline of each stained plaque was traced and the area (millimeters squared) was calculated by using ImageJ (1).

Electron microscopy of HELFs infected with the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 viruses.

HELFs at 72 h postinoculation were fixed with 2% gluteraldehyde and negatively stained with 1% osmium tetraoxide and 0.25% uranyl acetate as described previously (56). Thin sections on copper grids were viewed using a Philips CM-12 transmission electron microscope.

Replication of the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 viruses in human skin xenografts.

SCID mice (CB-17scid/scid) were implanted bilaterally with fetal human skin at least 5 weeks before inoculation of viruses as described previously (42). The Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care approved all animal protocols. Human tissues were provided by Advanced Bioscience Resources (Alameda, CA) and were obtained in accordance with state and federal regulations. Virus-infected HELFs were used to inoculate xenografts in the SCID mice. Inocula were titrated on melanoma cells as described previously to determine virus titer. At 10 and 21 days postinoculation, the implants were removed and homogenized for virus titration plus DNA and protein extraction. In addition, viruses were recovered from implants by passing them once on melanoma cells for further DNA extraction and sequence analysis.

RESULTS

Homology modeling of VZV gB.

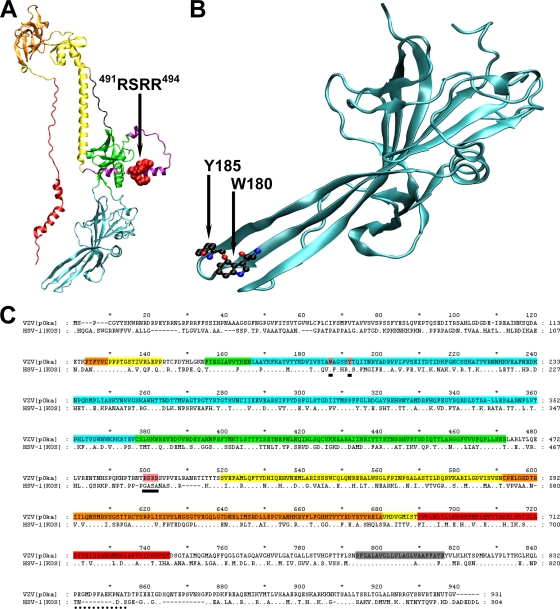

Amino acids that were of interest for mutagenesis studies of VZV gB were identified using a combination of homology modeling and amino acid sequence alignment. The modeled structure of VZV gB was similar to the experimentally derived crystal structure of HSV-1 gB (Fig. 1). The loop region of VZV gB between domains II and III, which was not resolved for HSV-1, was six amino acids longer than that of HSV-1 (Fig. 1A and C). This loop region contained the furin recognition motif 491RSRR494, making it accessible for cleavage by the subtilisin-like proprotein convertase. In the hydrophobic region of the first putative fusion loop in domain I, two residues, W180 and Y185, were conserved between VZV and HSV-1 (Fig. 1B). The conservation of these residues in the first fusion loop of domain I between the two herpesviruses implied that tryptophan and tyrosine were critical for the function of VZV and HSV-1 gB.

FIG. 1.

Location of the amino acids deleted or substituted in gB of VZV pOka. (A) Homology model of the ectodomain of VZV gB showing the location of the furin recognition motif (491RSRR494) (red space fill). Domains are indicated by colors used by Heldwein et al. (28) as follows: blue (domain I), green (domain II), yellow (domain III), orange (domain IV), and red (domain V). (B) Homology model of VZV gB domain I showing the location of residues W180 and Y185 in the putative primary fusion loop. (C) Amino acid alignment of the complete gBs from VZV[pOka] and HSV-1[KOS] showing the location of the amino acid substitutions (solid underline and pink shading) at W180 and Y185 plus the deletion/substitution of arginine at residues 491 to 494. Domains are indicated by the same colors used in panel A except for the transmembrane domain (gray). Dots in the alignment represent identical amino acids, and dashes represent gaps in the alignment. The dotted underline at residues 833 to 846 shows the location of the epitope in VZV gB used to generate the polyclonal rabbit serum 746-868.

The effect of mutagenesis in the furin recognition motif or primary fusion loop on gB expression.

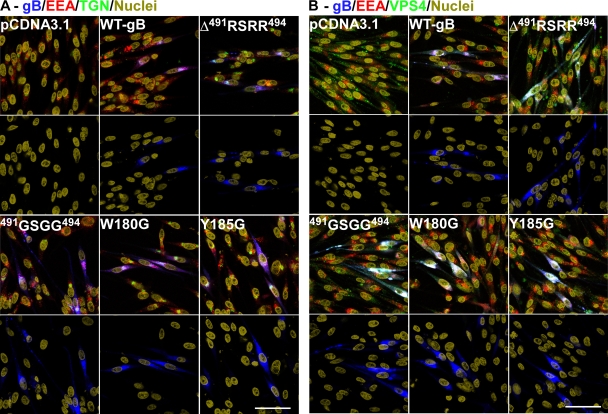

The localization and trafficking of transiently expressed gB were not different in melanoma cells transfected with wild-type pOka gB compared to the furin site mutations Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 or the putative fusion loop mutations W180G and Y185G (Fig. 2). Wild-type and mutant gBs were found throughout the cytoplasm and localized with early endosomes and also within the trans-Golgi as shown by confocal microscopy using the conformation-dependent anti-gB MAb SG2 (Fig. 2A). Previous studies have shown that wild-type gB trafficked to such cellular compartments (25). In addition, gB and the mutant gBs localized with the multivesicular body markers VPS4 and EEA-1 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Confocal microscopy showing the localization of VZV gB in melanoma cells transiently transfected with pCDNA3.1 constructs expressing wild-type or mutated gBs. (A) Cells were stained for gB (the conformation-dependent MAb SG2) (blue), early endosomes (rabbit polyclonal to EEA-1) (red), multivesicular bodies (goat anti-VPS4) (green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342) (yellow). (B) Cells were stained for gB (MAb SG2) (blue), early endosomes (rabbit polyclonal to EEA) (red), trans-Golgi (sheep anti-TGN46) (green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342) (yellow). Bar, 50 μm.

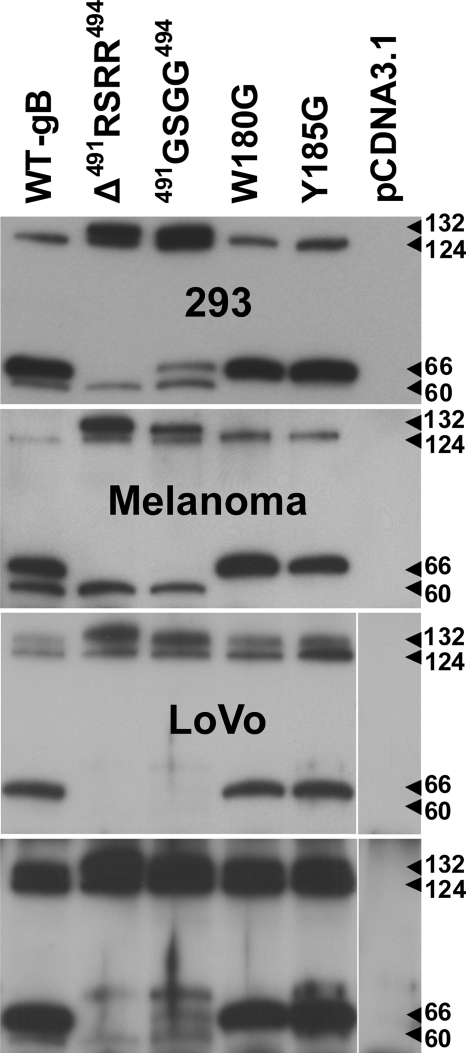

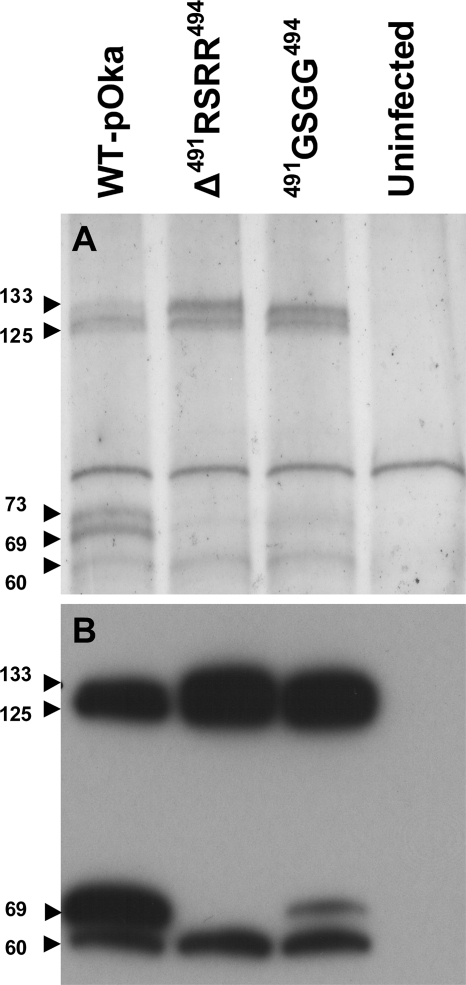

In contrast, clear differences were seen between the wild-type gB and the mutated proteins by immunoprecipitation of gB from transfected cell lines using MAb 158 (Fig. 3). The anti-gB MAb 158 reacts with gB in its native conformation (45). Thus, MAb 158 binding provided evidence about gross conformational changes resulting from the gB mutations. Three proteins with molecular masses of 124, 66, and 60 kDa were detected by immunoblot analysis of the precipitated wild-type gB with the peptide rabbit antiserum 746-868 that recognized an epitope (833PEGMDPFAEKPNAT846) in the cytoplasmic tail of gB (Fig. 1C and Fig. 3). The immature (124-kDa) and the COOH-terminal (66-kDa) cleavage products of wild-type pOka gB were expected to be detected by the 746-868 antiserum, but the additional protein at 60 kDa was not (Fig. 3, lane WT-gB). The proteolytic cleavage of gB was prevented by the Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 furin site mutations as predicted. This was shown by the presence of the immature (124-kDa) and mature (132-kDa) forms plus the lack of the COOH-terminal cleavage product (66 kDa), indicating that furin or another subtilisin-like proprotein convertase was responsible for the cleavage of VZV gB. As was observed with wild-type gB, an unexpected 60-kDa protein was detected for gBs with the Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 furin site mutations. A small quantity of gB 491GSGG494 was cleaved, but the protein was barely visible on the original blot (Fig. 3, Melanoma panel, lane 491GSGG494). In contrast to the furin site mutations, the amino acid substitutions W180G and Y185G in the putative fusion loop did not affect the proteolysis of gB as both the immature (124-kDa) and the COOH-terminal (66-kDa) cleavage products were detected. However, the 60-kDa protein was not present, suggesting that the putative fusion loop mutations had prevented additional processing of gB, which has not been reported previously. The observations in transfected melanoma cells were reproducible in transfection studies using HEK 293 cells including the small amount of cleaved gB with the furin site substitution 491GSGG494.

FIG. 3.

Western blot of VZV gB immunoprecipitated from HEK 293, melanoma, or LoVo cells transiently transfected with pCDNA3.1 constructs expressing wild-type or mutated gBs. gB was immunoprecipitated with the conformation-dependent MAb 158. The numbered arrowheads highlight the four polypeptides detected by the rabbit polyclonal antiserum 746-868 developed to the peptide 833PEGMDPFAEKPNAT846 located in the cytoplasmic domain of gB. The molecular masses (in kilodaltons) shown next to the arrowheads for each of the four polypeptides were calculated from protein standards. The bottom panel of LoVo cells was from a longer exposure to show the presence of the 60-kDa protein. The vector-only lane for the LoVo cells was from the same blot but was placed on the right side for consistency.

To determine whether proteases other than furin were implicated in the cleavage of gB cleavage, furin-deficient LoVo cells were transfected with gB and the gB mutants. This showed that the COOH-terminal peptides were generated by additional cellular proteases. In contrast to the melanoma and HEK 293 cells, the mature protein (132 kDa) accumulated to levels that were detectable by immunoblotting for each of the gB constructs, showing that furin was required for the cleavage of VZV gB (Fig. 3, top LoVo panel). The COOH-terminal 66-kDa polypeptide was detectable when wild-type gB and the putative fusion loop mutants W180G and Y185G were transfected into LoVo cells but appeared to be reduced in quantity compared to melanoma and HEK 293 cells. A longer exposure of the blot also showed the presence of the 60-kDa protein in cells transfected with wild-type gB and the furin site mutants Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 but not the putative fusion loop mutants W180G and Y185G, indicating that a portion of the polypeptide was generated by cellular proteases other than furin (Fig. 3, bottom LoVo panel). Thus, protein levels and the gross conformation of gB were not affected by the furin motif or putative fusion loop mutations in transfected cells.

Infectious virus was recovered from pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 but not pOka-gBW180G or pOka-gBY185G.

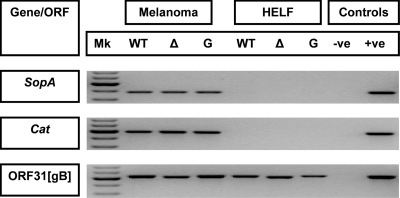

Transfection of melanoma cells with the self-excisable pOka-BAC carrying the furin site mutations Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 generated infectious virus. This demonstrated that furin was not required for VZV replication in vitro. The MiniF− sequences in the wild-type pOka and mutated BACs were removed by 10 passages in primary HELFs by a process of genomic recombination as reported previously (62). The successful recombination events were demonstrated by the loss of the SopA and Cat genes as determined by PCR analysis (Fig. 4). This was confirmed by Southern blotting, as DNA fragments of the expected sizes were produced for wild-type pOka plus the two furin mutant viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 following the 10 passages in HELFs (data not shown). The expected DNA sequences at the sites of mutagenesis were present for the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 viruses as determined by sequence analysis of DNA extracted from infected HELFs.

FIG. 4.

PCR analysis to confirm that the MiniF− plasmid was excised from the self-excisable pPOka-DX BAC upon passage in HELFs. SopA and Cat are genes in the MiniF plasmid. Mk, DNA ladder in 100-bp increments from 400 to 800 bp; WT, wild-type pOka; Δ, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494; G, pOka-gB491GSGG494; −ve, no-template PCR-negative control; +ve, pP-Oka-DX BAC DNA (10 ng/μl).

In contrast to the furin site mutagenesis, infectious virus could not be recovered from pOka-BACs carrying the substitutions W180G or Y185G in the putative fusion loops of gB. This was reproducible using two individual BAC clones for each mutant transfected into melanoma cells. To ensure that other essential sequences of the VZV genomes in the mutated BACs were intact, the W180G or Y185G substitutions in the mutant BAC clones were restored to their wild-type sequences. Infectious virus was recovered from melanoma cells transfected with the reverted W180G or Y185G BAC, demonstrating that each point mutation in the putative fusion loop was lethal for VZV replication.

Characterization of pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 in vitro.

The gB of pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 was not cleaved canonically in the context of virus replication as shown by immunoprecipitation of gB from infected melanoma cells (Fig. 5A and B). As expected for pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, only the immature (125-kDa) and mature (133-kDa) gB proteins were generated (Fig. 5A, lane Δ491RSRR494), whereas wild-type pOka generated the immature and mature proteins and the two cleavage products (69 and 73 kDa) of gB (Fig. 5A, lane WT-pOka). In addition, the accumulation of uncleaved, mature gB was more evident for pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 by the more intensely stained 133-kDa product than for wild-type pOka (Fig. 5A, lanes WT-pOka and Δ491RSRR494). In contrast to pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, there was a residual amount of gB cleavage for the pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus. This small amount of cleavage was apparent only by immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5B, lane 491GSGG494). Immunoprecipitations using beads alone or a MAb to VZV gE did not yield proteins of the same Mr as those seen with the anti-gB MAb 158 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunoprecipitation of gB from melanoma cells infected with pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494. gB was immunoprecipitated using MAb 158, and either the gels were silver stained (A) or Western blotting was performed using the rabbit anti-gB peptide serum 746-868 (B). The numbers next to the arrowheads are the molecular masses calculated for each of the proteins. Molecular masses were calculated from standard curves derived from the protein molecular mass markers.

As was observed for melanoma cells, HEK 293 cells, and LoVo cells transfected with ORF31 from the wild-type gB and Δ491RSRR494 and 491GSGG494 gB mutants, an additional 60-kDa protein was evident in cells infected with each of the viruses pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 (Fig. 5A and B, lanes WT-pOka, Δ491RSRR494, and 491GSGG494). The 60-kDa protein was determined to be a product of gB by using mass spectrometry. Of the 12 peptides identified, 9 (535ISSSWCQLQNR545, 574ILGDVISVSNCPE587, 593IILQNSMR600, 640DLLEPCVANHK650, 694EFMPLQVYTR704, 708DTGLLDYSEIQR720, 881YMTLVSAAER890, 901TSALLTSR908 and 923VRTENVTGV931) were from the COOH terminus and 3 (196VPIPVSEITDTID209, 271TGTSVNCIIEEVE284, and 441TGDIQTYLAR450) were from the NH2 terminus of gB. The greater abundance of peptides from the COOH terminus along with its reactivity with the 746-868 rabbit serum, which was developed to recognize the cytoplasmic epitope 833PEGMDPFAEKPNAT846, showed that the 60-kDa protein was derived from the COOH terminus of gB.

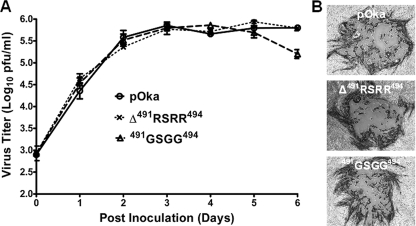

The lack of canonical gB cleavage did not affect the replication of pOka, protein localization, or the formation of virus particles. The replication kinetics of pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 were similar to those of wild-type pOka (Fig. 6A). A >2.5-log10 PFU/ml increase from the inoculum titer (∼3.0 log10 PFU/ml) was seen for all of the viruses within the first 3 days postinoculation of the melanoma cells. Viral titers reached a plateau at day 3 and continued until day 5 postinoculation for each of the viruses. In addition, viral plaque morphologies were similar between wild-type pOka and the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus in melanoma cells (Fig. 6B). The mean areas for the plaques generated were not significantly different between the wild-type pOka (1.847 mm2; standard error of the mean [SEM], 0.162) and pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 (1.635 mm2; SEM, 0.128) or pOka-gB491GSGG494 (1.730 mm2; SEM, 0.115).

FIG. 6.

Replication of wild-type pOka and the two gB mutant viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 in melanoma cells. (A) Replication kinetics of pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 over 6 days. (B) Plaque morphologies of pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 in melanoma cells at 4 days postinoculation.

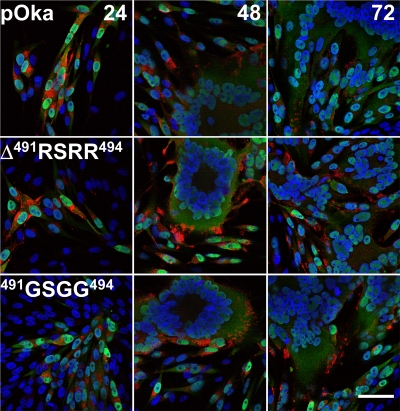

In addition, cellular localization of gB and syncytium formation were more similar to pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 than to wild-type pOka for 72 h (Fig. 7). The localization of gB was typically perinuclear at early time points during infection, becoming extensively cytoplasmic and then found with the most intense staining on cell membranes at the periphery of the syncytium. The typical rosettes of nuclei indicative of syncytia induced by VZV infection were seen for all of the viruses. In addition, the cellular distribution of IE63 was not altered.

FIG. 7.

Confocal microscopy showing the cellular localization of the viral proteins gB and IE63 in melanoma cells infected with wild-type pOka and the two gB mutant viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494. Images were captured at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Melanoma cells were stained with rabbit anti-IE63 (green), MAb to gB (SG2) (red), and Hoechst 33342 to stain the nuclei (blue). Bar, 50 μm.

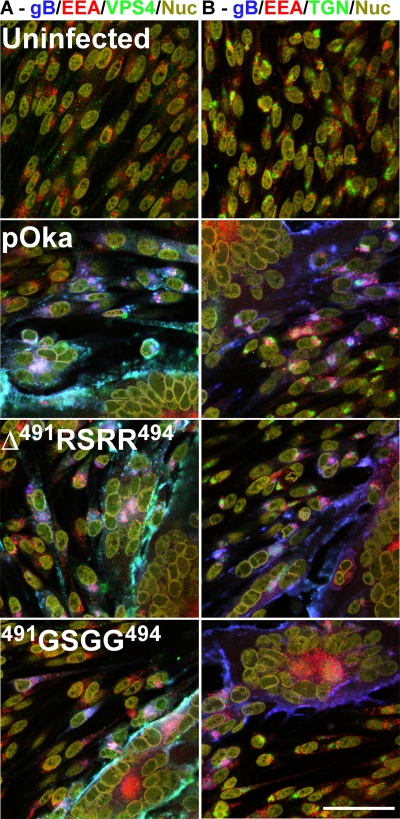

In agreement with the gB expression constructs in transfected melanoma cells, gB localized with the early endosome marker (EEA-1) in newly infected cells at the periphery of syncytia of wild-type pOka and the two mutants pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 at 48 h postinfection (Fig. 8). The gB of all three viruses was also shown to localize with the MVB marker (VPS4) with extensive colocalization at the membrane of infected cells and syncytia. Localization of gB within the trans-Golgi (TGN46) was seen for each of the mutant viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 and was similar to that of wild-type pOka, which showed a perinuclear pattern in newly infected cells. The localization of gB with EEA-1, TGN46, and VPS4 suggests a progressive trafficking of gB through the cell via endocytosis as previously reported (25). Thus, trafficking of the mutant gBs pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 was unaffected compared to that of wild-type pOka.

FIG. 8.

Confocal microscopy showing the localization of VZV gB in melanoma cells infected with wild-type pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, or pOka-gB491GSGG494 at 48 h postinfection. (A) Cells were stained for gB (MAb SG2) (blue), early endosomes (rabbit polyclonal to EEA-1) (red), multivesicular bodies (goat anti-VPS4) (green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342) (yellow). (B) Cells were stained for gB (MAb SG2) (blue), early endosomes (rabbit polyclonal to EEA-1) (red), trans-Golgi (sheep anti-TGN46) (green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342) (yellow). Bar, 50 μm.

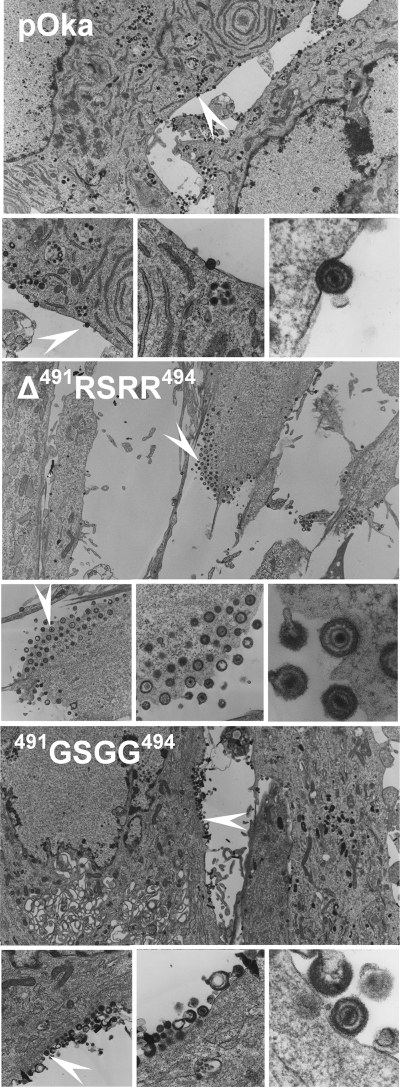

No differences in virus particle formation or morphology were detected between wild-type pOka and the two viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 (Fig. 9). Particles from each of the viruses contained genomic DNA surrounded by a nucleocapsid, followed by a biphasic tegument enveloped with a bilipid membrane that was covered in small projections. This showed that the lack of canonical gB cleavage did not affect virus particle assembly or transport to the cell surface. Viral nucleocapsids were also abundant in the nuclei of cells infected with wild-type pOka, pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494, and pOka-gB491GSGG494 (data not shown). Thus, proteolysis at the furin recognition motif in gB was not required and had no detrimental effect on viral replication in vitro.

FIG. 9.

Electron microscopy of virus particles in HELFs infected with the wild-type pOka or mutant gB viruses pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494. Images were captured using a Philips CM-12 transmission electron microscope at a magnification of ×3,000 (3K) (large image), ×10K (left), ×22K (middle), or ×75K (right). White arrows indicate the location of the virus particle shown in the images taken at a magnification of ×75K.

Pathogenesis of pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 and pOka-gB491GSGG494 in human skin xenografts.

In contrast to the in vitro studies, reduced cleavage of gB at the furin recognition motif diminished the replication of VZV in human skin xenografts in vivo. Viral titers recovered from skin xenografts were lower at both 10 and 21 days postinoculation with either pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 compared to that with wild-type pOka (Table 2). However, only the furin motif deletion mutant pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 had significantly decreased titers compared to those of pOka. The reductions in titer were 1.5 log10 PFU (32-fold; day 10) and 1.0 log10 PFU (10-fold; day 21). The observation that titers of pOka-gB491GSGG494 were somewhat higher than pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 was likely attributed to the residual amount of gB cleavage seen by immunoprecipitation of gB from pOka-gB491GSGG494-infected melanoma cells in vitro (Fig. 5B, lane 491GSGG494). Infectious virus was not detected in three of five xenografts infected with pOka-gB491GSGG494 compared to four of four infected with pOka at day 10, indicating a delayed growth. The expected DNA sequences in ORF31[gB] were present for pOka and the two mutant viruses recovered from the xenografts at day 10 and 21 postinfection after passage in melanoma cells. In addition, immunoblotting of cell lysates from infected skin xenografts showed that the mature form of gB had accumulated in those infected with the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus, but gB cleavage had occurred for wild-type pOka (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Titers and the number of skin xenografts infected with wild-type pOka and the two gB mutant viruses pOka-gBΔ428RSRR431 and pOka-gB428GSGG431

| Virus | Inoculum titer (log10 PFU/ml [SEM]) | No. of infected implants determined by PCR at day:

|

No. of infected implants determined by virus recovery at day:

|

Virus titer in implants at day (log10 PFU/ml [SEM]):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 21 | 10 | 21 | 10 | 21 | ||

| pOka | 5.0 (0.017) | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3.5 (0.305) | 4.3 (0.245) |

| Δ428RSRR431 | 5.2 (0.031) | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 5/5 | 2.0 (0.631)a | 3.3 (0.150)b |

| 428GSGG431 | 5.1 (0.061) | 4/5 | 5/5 | 3/5 | 5/5 | 2.9 (1.068) | 3.8 (0.199) |

Statistically significantly different from pOka (two-way analysis of variance; P < 0.01).

Statistically significantly different from pOka (two-way analysis of variance; P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

VZV gB, like its homologues in other herpesviruses, is presumed to be essential for VZV replication. Mutagenesis in the present study of ORF31, which encodes VZV gB, in the context of the viral genome demonstrated that residues in two sites within the putative fusion loop are required for VZV replication and that furin cleavage motif contributes to VZV pathogenesis.

Deletion of the gB furin recognition motif attenuated VZV replication in human skin xenografts in SCID mice, despite an unaltered phenotype in vitro. These observations are the first evidence that this gB motif, which is highly conserved in the Herpesviridae with the exception of HSV, has a function in viral infection in vivo. Failure to generate the 66-kDa cleavage product from gB and the associated reduction in VZV titer from the human skin xenografts were consistent with observations that disruption of cleavage in fusogenic glycoproteins from other virus families caused reduced pathogenicity or was required for successful viral replication (8, 35, 39, 47). Previous studies using the skin xenograft model identified reduced pathogenesis or lethality in the differentiated human skin of VZV mutants that had unaltered phenotypes in vitro (7, 14, 43, 65). The model also reproduced the clinical evidence of attenuation of the varicella vaccine. The vaccine strain (vOka) replicated poorly (∼1-log10 PFU reduction at days 14 and 21 postinfection) compared to pOka in differentiated human tissue in vivo despite similar levels of replication in vitro (43). The effect of deleting the furin cleavage motif in gBΔ491RSRR494 was similar to the attenuation of the vaccine Oka virus in the SCIDhu skin xenograft model.

Control of VZV replication in skin xenografts in SCIDhu mice is limited to innate immune responses (33). In the presence of an active adaptive immune response to VZV, lacking in the SCID mice, a greater difference in virulence of wild-type pOka and the gB cleavage mutant viruses would be predicted because of the slower spread of attenuated viruses carrying the furin site mutations in skin tissue. The reduced spread was apparent by the statistically significant differences in titer at both days 10 and 21 postinfection compared to wild-type virus. This resembled previous studies with the vaccine Oka virus, which typically does not cause disease in the immunocompetent host but produced lesions in skin xenografts and spread more slowly than the pOka virus (2, 43, 59). In the immunocompetent host, VZV and HSV typically have different pathologies during the primary infection because VZV is lymphotropic and disseminates to skin systemically (33). However, both VZV and HSV spread by cell-cell fusion at the sites of lesion formation in mucocutaneous tissues. Since HSV gB lacks a furin cleavage site but a block in gB cleavage reduced VZV pathogenesis, it appears that gB functions have evolved differently to mediate cell-cell fusion in these tissue microenvironments in vivo, or, although unlikely, HSV gB is not required for this process.

The small amount of cleaved gB from the pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus might have been sufficient to maintain viral titers approaching those of wild-type pOka in skin tissue. This observation reinforced the evidence obtained with the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 mutant showing that the furin cleavage motif had a functional role in the pathogenesis of VZV in vivo. In addition, residual cleavage of the gB491GSGG494 mutant suggested that, like fusion proteins from other virus families (30, 31, 46), furin was not the only endoproteinase that can cleave gB in the linker region between domains II and III. Two examples of predicted motifs in the linker region are the clara recognition site ([EQ]-X-[R]-|-X) and the subtilisin/kexin isozyme 1 recognition site ([RK]-X-[hydrophobic]-[LTKF]-|-X) located at amino acid residues 499 to 501 and 504 to 507, respectively. Cleavage of gB that was not solely dependent on the furin motif was confirmed by the accumulation of mature protein plus the reduction in quantity of the 66-kDa protein in furin-deficient LoVo cells. There was also an additional protein of approximately 70 kDa, suggesting that the LoVo cells express proteases able to cleave at different sites than proteases expressed by HEK 293 or melanoma cells. The additional cleavage products were unexpected as previous mutagenesis studies of the furin cleavage motif in gB of other herpesviruses in the context of viral genomes did not show evidence for cleavage outside of the furin site (32, 58). In common with the present study, the BHV-1 and HCMV furin mutations were performed by deletion (HCMV; the 15 amino acids FAAAAPKPGPRRARR) or amino acid substitution (BHV; RTRR to ATRA) of arginines in their furin recognition motifs. However, arginine-to-glycine substitutions were performed in the present study to retain the carbon backbone in order to reduce their effect on the structural conformation of the linker region between domains II and III. This might have prevented any alteration in the accessibility of an additional cleavage motif(s), allowing cell proteases to cleave at alternative sites in the VZV gB.

The preserved replication of the VZV furin cleavage site mutants in vitro was not surprising as this has been demonstrated previously for HCMV, BHV-1, and PRV (32, 49, 58). However, the reduction in replication kinetics and plaque size observed with the BHV-1 gBΔFur mutant and the altered syncytium formation in PRV experiments were not seen for either the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 virus (32, 49). The lack of reduction in syncytium formation for the VZV furin cleavage mutants might be because the present study performed gB mutagenesis in the context of the VZV genome, whereas the PRV study that demonstrated such an effect used furin inhibitors or LoVo cells that were deficient in furin (49). This approach could have more global effects on viral replication as sequence analyses indicated there were furin recognition motifs in many herpesvirus proteins (unpublished observation). In agreement with this hypothesis, attempts to propagate VZV in the furin-deficient LoVo cells were unsuccessful (data not shown). Therefore, the effects of VZV and PRV gB mutagenesis cannot be correlated because directed mutagenesis at the furin recognition motif in the PRV gB was not performed. In agreement with the present study, HCMV gBΔFur did not show an altered phenotype in vitro (58). Whether gB cleavage mutants of these other viruses were attenuated in differentiated host tissue was not reported.

In the family Herpesviridae, gBs are required for fusion of the enveloped virion with the target cell membrane during entry in conjunction with gH/gL and either viral or cellular accessory proteins (12, 27, 57). The interactions between gB, gH/gL, and the accessory proteins result in a complex that mediates entry. Since VZV replicates in a highly cell-associated manner, it is not possible to recover sufficient quantities of VZV virions to evaluate cell entry with the methods that have been used to demonstrate the functional requirements for each of these glycoproteins in other herpesviruses. In addition, a fusion assay for VZV has not been established. Therefore, the consequences of disrupting gB furin cleavage on VZV entry could not be defined. However, virion morphogenesis did not appear to be altered in cells infected with the pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 or pOka-gB491GSGG494 mutant by electron microscopy analysis. The possibility remains that the cleavage site of VZV gB might be the remnant of an active site not directly linked with virion envelope-cellular membrane fusion as a result of the complex mechanism that has evolved in members of the Herpesviridae.

Immunoprecipitation of gB from transfected or infected cells showed that the membrane-anchored COOH terminal and the distal NH2 terminal remain associated since MAb 158 is known to precipitate gB in its native conformation (45). From an analysis of the homology model of VZV gB (Fig. 1), we speculate that the intermolecular interactions that hold the cleaved polypeptides together were likely to be disulfide bonds between cysteine residues at 116/579 and 139/540. The furin motif deletion, glycine substitutions, or the point mutations in the putative primary fusion loop did not disrupt this interaction in transfected cells. In addition, intracellular trafficking of gB in cells infected with the gB mutants was unaffected. VZV gB has been demonstrated to be transported to the cell surface, endocytosed, and then localized to the trans-Golgi (24-26). The localization of VZV gB with the EEA-1 and TGN46 in transfected and infected melanoma cells supported this gB trafficking pattern. HSV-1 required VPS4 for cytoplasmic envelopment and egress of virions (11, 17). Therefore, the localization of VZV gB with VPS4 suggests a similar requirement as the furin motif mutant viruses showed the same pattern. Taken together, these observations suggest that the attenuation of pOka-gBΔ491RSRR494 in skin tissue and the lack of recovery of virus from W180G or Y185G was not a consequence of gross structural alterations or altered cellular trafficking of gB.

The lack of virus recovery from BACs with the W180 or Y185 point mutation in the putative primary fusion loop demonstrated the importance of this region in VZV gB in the context of virus replication. In a previous study of HSV-1 gB, fusion was significantly reduced in vitro by linker insertions of five amino acids at residue I185 or E187 of HSV-1 gB (34). In addition, an HSV-1 ΔgB could not be complemented using transient expression of gB with these linker insertions. A study with the gammaherpesvirus Epstein-Barr virus showed that substitutions at residues 112YW113 of gB also significantly reduced or abrogated gB-mediated fusion as determined by an in vitro assay (4). Thus, evidence that the putative fusion loop is required for herpesvirus replication has been strengthened by the present study. The lack of virus recovery was not a consequence of spontaneous mutations arising elsewhere in the pOka-BAC-derived genome as the rescue of virus was possible when the mutations in the pOka-BAC were reverted back to the wild type. Currently, it has not been possible to perform in vitro fusion assays for VZV. It would be highly likely that VZV gB carrying the W180G and Y185G point mutations would abrogate gB-mediated fusion.

We conclude that specific residues in the putative fusion loop are essential for VZV replication and that gB cleavage at the furin motif, while dispensable for VZV replication in cultured cells, contributes to VZV pathogenesis in skin tissue. In addition, the presence of the gB cleavage motif in VZV constitutes a difference from HSV gB that may be related to some differences in the pathogenesis of infections caused by these two alphaherpesviruses in the human host.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI053846, AI20459, and CA049605.

We thank Chris Adams for providing assistance with mass spectrometry at the Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Stanford University, and Nafisa Ghori for assistance with electron microscopy.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 May 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramoff, M. D., P. J. Magelhaes, and S. J. Ram. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 1136-42. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeter, A. M., S. E. Starr, R. E. Weibel, and S. A. Plotkin. 1982. Live attenuated varicella vaccine: immunization of healthy children with the OKA strain. J. Pediatr. 100886-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold, K., L. Bordoli, J. Kopp, and T. Schwede. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backovic, M., T. S. Jardetzky, and R. Longnecker. 2007. Hydrophobic residues that form putative fusion loops of Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein B are critical for fusion activity. J. Virol. 819596-9600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backovic, M., G. P. Leser, R. A. Lamb, R. Longnecker, and T. S. Jardetzky. 2007. Characterization of EBV gB indicates properties of both class I and class II viral fusion proteins. Virology 368102-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berarducci, B., M. Ikoma, S. Stamatis, M. Sommer, C. Grose, and A. M. Arvin. 2006. Essential functions of the unique N-terminal region of the varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E ectodomain in viral replication and in the pathogenesis of skin infection. J. Virol. 809481-9496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besser, J., M. H. Sommer, L. Zerboni, C. P. Bagowski, H. Ito, J. Moffat, C. C. Ku, and A. M. Arvin. 2003. Differentiation of varicella-zoster virus ORF47 protein kinase and IE62 protein binding domains and their contributions to replication in human skin xenografts in the SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 775964-5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch, F. X., M. Orlich, H. D. Klenk, and R. Rott. 1979. The structure of the hemagglutinin, a determinant for the pathogenicity of influenza viruses. Virology 95197-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britt, W. J., and L. G. Vugler. 1989. Processing of the gp55-116 envelope glycoprotein complex (gB) of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 63403-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai, W. H., B. Gu, and S. Person. 1988. Role of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus type 1 in viral entry and cell fusion. J. Virol. 622596-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calistri, A., P. Sette, C. Salata, E. Cancellotti, C. Forghieri, A. Comin, H. Gottlinger, G. Campadelli-Fiume, G. Palu, and C. Parolin. 2007. Intracellular trafficking and maturation of herpes simplex virus type 1 gB and virus egress require functional biogenesis of multivesicular bodies. J. Virol. 8111468-11478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campadelli-Fiume, G., M. Amasio, E. Avitabile, A. Cerretani, C. Forghieri, T. Gianni, and L. Menotti. 2007. The multipartite system that mediates entry of herpes simplex virus into the cell. Rev. Med. Virol. 17313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Che, X., M. Reichelt, M. H. Sommer, J. Rajamani, L. Zerboni, and A. M. Arvin. 2008. Functions of the ORF9-to-ORF12 gene cluster in varicella-zoster virus replication and in the pathogenesis of skin infection. J. Virol. 825825-5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Che, X., L. Zerboni, M. H. Sommer, and A. M. Arvin. 2006. Varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 10 is a virulence determinant in skin cells but not in T cells in vivo. J. Virol. 803238-3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheatham, W. J., T. F. Dolan, Jr., J. C. Dower, and T. H. Weller. 1956. Varicella: report of two fatal cases with necropsy, virus isolation, and serologic studies. Am. J. Pathol. 321015-1035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen, J. I., S. E. Straus, and A. Arvin. 2007. Varicella-zoster virus replication, pathogenesis and management, p. 2773-2818. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 17.Crump, C. M., C. Yates, and T. Minson. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 cytoplasmic envelopment requires functional Vps4. J. Virol. 817380-7387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davison, A. J., and J. E. Scott. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 671759-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzpatrick, D. R., T. J. Zamb, and L. A. Babiuk. 1990. Expression of bovine herpesvirus type 1 glycoprotein gI in transfected bovine cells induces spontaneous cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 71215-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grose, C., D. P. Edwards, K. A. Weigle, W. E. Friedrichs, and W. L. McGuire. 1984. Varicella-zoster virus-specific gp140: a highly immunogenic and disulfide-linked structural glycoprotein. Virology 132138-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampl, H., T. Ben-Porat, L. Ehrlicher, K. O. Habermehl, and A. S. Kaplan. 1984. Characterization of the envelope proteins of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 52583-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannah, B. P., E. E. Heldwein, F. C. Bender, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2007. Mutational evidence of internal fusion loops in herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 814858-4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1999. Using antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 24.Heineman, T. C., and S. L. Hall. 2002. Role of the varicella-zoster virus gB cytoplasmic domain in gB transport and viral egress. J. Virol. 76591-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heineman, T. C., and S. L. Hall. 2001. VZV gB endocytosis and Golgi localization are mediated by YXXφ motifs in its cytoplasmic domain. Virology 28542-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heineman, T. C., N. Krudwig, and S. L. Hall. 2000. Cytoplasmic domain signal sequences that mediate transport of varicella-zoster virus gB from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi. J. Virol. 749421-9430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heldwein, E. E., and C. Krummenacher. 2008. Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 651653-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heldwein, E. E., H. Lou, F. C. Bender, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and S. C. Harrison. 2006. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science 313217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosaka, M., M. Nagahama, W. S. Kim, T. Watanabe, K. Hatsuzawa, J. Ikemizu, K. Murakami, and K. Nakayama. 1991. Arg-X-Lys/Arg-Arg motif as a signal for precursor cleavage catalyzed by furin within the constitutive secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 26612127-12130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kido, H., Y. Niwa, Y. Beppu, and T. Towatari. 1996. Cellular proteases involved in the pathogenicity of enveloped animal viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, influenza virus A and Sendai virus. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 36325-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klenk, H. D., and W. Garten. 1994. Host cell proteases controlling virus pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 239-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopp, A., E. Blewett, V. Misra, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 1994. Proteolytic cleavage of bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) glycoprotein gB is not necessary for its function in BHV-1 or pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 681667-1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ku, C. C., J. Besser, A. Abendroth, C. Grose, and A. M. Arvin. 2005. Varicella-zoster virus pathogenesis and immunobiology: new concepts emerging from investigations with the SCIDhu mouse model. J. Virol. 792651-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin, E., and P. G. Spear. 2007. Random linker-insertion mutagenesis to identify functional domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10413140-13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobigs, M., and H. Garoff. 1990. Fusion function of the Semliki Forest virus spike is activated by proteolytic cleavage of the envelope glycoprotein precursor p62. J. Virol. 641233-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loh, L. C. 1991. Synthesis and processing of the major envelope glycoprotein of murine cytomegalovirus. Virology 180239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maresova, L., T. Pasieka, T. Wagenaar, W. Jackson, and C. Grose. 2003. Identification of the authentic varicella-zoster virus gB (gene 31) initiating methionine overlapping the 3′ end of gene 30. J. Med. Virol. 70(Suppl. 1)S64-S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maresova, L., T. J. Pasieka, and C. Grose. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus gB and gE coexpression, but not gB or gE alone, leads to abundant fusion and syncytium formation equivalent to those from gH and gL coexpression. J. Virol. 759483-9492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCune, J. M., L. B. Rabin, M. B. Feinberg, M. Lieberman, J. C. Kosek, G. R. Reyes, and I. L. Weissman. 1988. Endoproteolytic cleavage of gp160 is required for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 5355-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meredith, D. M., J. M. Stocks, G. R. Whittaker, I. W. Halliburton, B. W. Snowden, and R. A. Killington. 1989. Identification of the gB homologues of equine herpesvirus types 1 and 4 as disulphide-linked heterodimers and their characterization using monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 701161-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moffat, J., H. Ito, M. Sommer, S. Taylor, and A. M. Arvin. 2002. Glycoprotein I of varicella-zoster virus is required for viral replication in skin and T cells. J. Virol. 768468-8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moffat, J. F., M. D. Stein, H. Kaneshima, and A. M. Arvin. 1995. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and epidermal cells in SCID-hu mice. J. Virol. 695236-5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moffat, J. F., L. Zerboni, P. R. Kinchington, C. Grose, H. Kaneshima, and A. M. Arvin. 1998. Attenuation of the vaccine Oka strain of varicella-zoster virus and role of glycoprotein C in alphaherpesvirus virulence demonstrated in the SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 72965-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moffat, J. F., L. Zerboni, M. H. Sommer, T. C. Heineman, J. I. Cohen, H. Kaneshima, and A. M. Arvin. 1998. The ORF47 and ORF66 putative protein kinases of varicella-zoster virus determine tropism for human T cells and skin in the SCID-hu mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9511969-11974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montalvo, E. A., and C. Grose. 1987. Assembly and processing of the disulfide-linked varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein gpII(140). J. Virol. 612877-2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami, M., T. Towatari, M. Ohuchi, M. Shiota, M. Akao, Y. Okumura, M. A. Parry, and H. Kido. 2001. Mini-plasmin found in the epithelial cells of bronchioles triggers infection by broad-spectrum influenza A viruses and Sendai virus. Eur. J. Biochem. 2682847-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai, Y., H. D. Klenk, and R. Rott. 1976. Proteolytic cleavage of the viral glycoproteins and its significance for the virulence of Newcastle disease virus. Virology 72494-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Navarro, D., P. Paz, and L. Pereira. 1992. Domains of herpes simplex virus I glycoprotein B that function in virus penetration, cell-to-cell spread, and cell fusion. Virology 18699-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okazaki, K. 2007. Proteolytic cleavage of glycoprotein B is dispensable for in vitro replication, but required for syncytium formation of pseudorabies virus. J. Gen. Virol. 881859-1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliver, S. L., L. Zerboni, M. Sommer, J. Rajamani, and A. M. Arvin. 2008. Development of recombinant varicella-zoster viruses expressing luciferase fusion proteins for live in vivo imaging in human skin and dorsal root ganglia xenografts. J. Virol. Methods 154182-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peeters, B., N. de Wind, M. Hooisma, F. Wagenaar, A. Gielkens, and R. Moormann. 1992. Pseudorabies virus envelope glycoproteins gp50 and gII are essential for virus penetration, but only gII is involved in membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66894-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rauh, I., and T. C. Mettenleiter. 1991. Pseudorabies virus glycoproteins gII and gp50 are essential for virus penetration. J. Virol. 655348-5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ross, L. J., M. Sanderson, S. D. Scott, M. M. Binns, T. Doel, and B. Milne. 1989. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the Marek's disease virus homologue of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus. J. Gen. Virol. 701789-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santos, R. A., C. C. Hatfield, N. L. Cole, J. A. Padilla, J. F. Moffat, A. M. Arvin, W. T. Ruyechan, J. Hay, and C. Grose. 2000. Varicella-zoster virus gE escape mutant VZV-MSP exhibits an accelerated cell-to-cell spread phenotype in both infected cell cultures and SCID-hu mice. Virology 275306-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sato, B., H. Ito, S. Hinchliffe, M. H. Sommer, L. Zerboni, and A. M. Arvin. 2003. Mutational analysis of open reading frames 62 and 71, encoding the varicella-zoster virus immediate-early transactivating protein, IE62, and effects on replication in vitro and in skin xenografts in the SCID-hu mouse in vivo. J. Virol. 775607-5620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaap, A., J. F. Fortin, M. Sommer, L. Zerboni, S. Stamatis, C. C. Ku, G. P. Nolan, and A. M. Arvin. 2005. T-cell tropism and the role of ORF66 protein in pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection. J. Virol. 7912921-12933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spear, P. G., and R. Longnecker. 2003. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J. Virol. 7710179-10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strive, T., E. Borst, M. Messerle, and K. Radsak. 2002. Proteolytic processing of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B is dispensable for viral growth in culture. J. Virol. 761252-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi, M., Y. Okuno, T. Otsuka, J. Osame, and A. Takamizawa. 1975. Development of a live attenuated varicella vaccine. Biken J. 1825-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takahashi, S., K. Kasai, K. Hatsuzawa, N. Kitamura, Y. Misumi, Y. Ikehara, K. Murakami, and K. Nakayama. 1993. A mutation of furin causes the lack of precursor-processing activity in human colon carcinoma LoVo cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1951019-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi, S., T. Nakagawa, K. Kasai, T. Banno, S. J. Duguay, W. J. Van de Ven, K. Murakami, and K. Nakayama. 1995. A second mutant allele of furin in the processing-incompetent cell line, LoVo. Evidence for involvement of the homo B domain in autocatalytic activation. J. Biol. Chem. 27026565-26569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tischer, B. K., B. B. Kaufer, M. Sommer, F. Wussow, A. M. Arvin, and N. Osterrieder. 2007. A self-excisable infectious bacterial artificial chromosome clone of varicella-zoster virus allows analysis of the essential tegument protein encoded by ORF9. J. Virol. 8113200-13208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S., and L. A. Babiuk. 1986. Synthesis and processing of bovine herpesvirus 1 glycoproteins. J. Virol. 59401-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vey, M., W. Schafer, B. Reis, R. Ohuchi, W. Britt, W. Garten, H. D. Klenk, and K. Radsak. 1995. Proteolytic processing of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gpUL55) is mediated by the human endoprotease furin. Virology 206746-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zerboni, L., S. Hinchliffe, M. H. Sommer, H. Ito, J. Besser, S. Stamatis, J. Cheng, D. Distefano, N. Kraiouchkine, A. Shaw, and A. M. Arvin. 2005. Analysis of varicella zoster virus attenuation by evaluation of chimeric parent Oka/vaccine Oka recombinant viruses in skin xenografts in the SCIDhu mouse model. Virology 332337-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]