SYNOPSIS

We evaluated a lay health promoter program providing occupational health and safety education to immigrant Latino poultry processing workers in western North Carolina. While such programs are advocated for addressing the health education deficits of immigrant and disadvantaged populations, their application in occupational health has been limited to farmworkers. A community-university partnership recruited and trained promoters to deliver lessons on musculoskeletal injuries, slips and falls, and workers' rights to workers individually or in small groups in the community. Evaluation showed 841 workers received education during a 28-month period. Using ethnographic data, an evaluation showed that promoters' work led to changes in behavior and attitudes in the community. Promoters also reported substantial changes in self-esteem and independence. Promoters' supervisors reported challenges and strategies experienced by the promoters. Promoter programs in occupational health and safety are feasible approaches to supplement training provided in the workplace.

This article describes and evaluates a lay health promoter program to reduce occupational injuries and illnesses among immigrant Latino poultry processing employees in western North Carolina. Based in a community-university partnership, this program was designed to overcome two problems. The first problem is that poultry processing companies provide only limited safety training to employees, so that many do not understand how the jobs they do relate to the injuries and illnesses they experience. The second problem is that immigrant workers often do not understand the rights of workers in the United States to a safe work environment, regardless of documentation status.

This article first describes the context of poultry processing work. It then describes the lay health promoter—in Spanish, promotora de salud—program designed to educate and empower workers. To evaluate the program, we drew on ongoing ethnography in the study communities to examine workers' changing attitudes toward health, safety, and workers' rights, and the effect of the program on the promoters themselves.

BACKGROUND

Poultry processing is dirty and violent work that applies high-speed assembly line technology to the hatching, growing, and butchering of birds in an industry with small profit margins.1,2 The birds are taken from their cages, stunned, and hung by their feet on hooks on an overhead moving belt. They are killed, plucked, eviscerated, often deboned, and packaged—all at a speed of more than one bird per worker per second. Workers accomplish this efficiency by working at high rates of speed for long periods with few breaks. Working in awkward positions in a wet and cold environment, repeating the same movements, and using sharp instruments, poultry workers are at risk for respiratory, dermatological, and musculoskeletal injuries. The stress of this work is often exacerbated by supervisors who push to keep the line moving at the desired speed.3,4

The poultry processing industry has some of the highest occupational injury rates of all U.S. industries.3 In 2004, almost 20,000 poultry workers nationwide reported occupational injuries or illnesses severe enough to miss work or seek medical care, for a rate of 7.8 per 100 full-time workers. The nonfatal injury rate was 5.5 per 100 workers,5 and the illness rate was 2.3 per 100 workers.6 Poultry processing had the sixth highest occupational illness rate of any private industry in the U.S. in 2004.7

The actual injury and illness rate is likely to be even higher than what is officially recorded due to a number of factors.8 Workers view hazards as part of the job, or they move on to other jobs as symptoms develop, especially if those symptoms limit work activity.2,9 Reports from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the only source of health statistics for the industry, do not count symptoms or illnesses that are considered by the worker or supervisor to be unrelated to work.10 Suspected undercounts of injury and illness are corroborated by published studies of Latino poultry processing workers indicating that 60% of workers reported symptoms indicative of work-related illness.11 Recent congressional hearings on occupational injury and illness undercounts concluded that as much as 69% of injuries and illnesses never find their way into the OSHA statistical summaries.12

During the past several decades, poultry processing and meatpacking facilities have become concentrated in rural communities, largely in the South.1,11,13 Although the industry has historically relied on minority workers, today fully 42% of poultry processing workers are Hispanic and 26% are foreign-born.3 This ethnically diverse workforce creates a variety of problems that likely undermine occupational health. Communication difficulties create barriers to conveying and enforcing safety standards. Also, reliance on immigrant, frequently foreign-born workers creates substantial potential for exploitation, as undocumented workers are unlikely to file a work-related complaint.9,11,13

Health, safety, and legal-rights information can be provided to workers in a number of different ways. The use of promotoras de salud to deliver health information and health services has been advocated as a way to extend existing health service delivery and provide culturally competent services for minority and immigrant populations.14,15 Promoters are considered an effective and economical way to assist individuals in marginalized populations,15 particularly where existing health service personnel are inadequate and where the population has specific needs that do not require highly trained professionals. Despite their popularity, the use of lay health promoters for improving occupational health and safety has been limited to farmworkers and their families. Programs have been shown to improve pesticide safety knowledge and behavior16,17 and promote eye safety.18,19 Their success suggests that promoters may also be appropriate for other industries.

THE PROMOTER PROGRAM

The promoter program evaluated in this article was designed and implemented by Justice and Health for Poultry Workers (JUSTA), a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)-funded partnership between health scientists and health-care providers at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and community advocates and educators at two North Carolina community-based organizations (CBOs), the Western North Carolina Workers Center in Morganton and Centro Latino of Caldwell County in Lenoir, two areas with large poultry processing plants. The partnership operated in a six-county area of western North Carolina, including Alexander, Burke, Caldwell, Surry, Wilkes, and Yadkin counties. This region has a total of five poultry processing plants belonging to three different companies. With input from a community advisory board, the partnership undertook efforts to document the physical and psychosocial impacts of poultry employment on Latino workers in western North Carolina4,11,20 and to develop ways of assisting workers individually and collectively in protecting themselves from the demands of this work.

Based on the research findings,11 the partnership designed a curriculum that included two primary lessons to be presented to either individual workers or small groups. The first focused on musculoskeletal injuries resulting from repetitive motion and from working in ergonomically incorrect workstations. The second focused on slips and falls, and on workers supporting each other to avoid injuries. Both lessons informed workers that they had a right to safe workplaces and to workers' compensation in case of work-related injuries and illnesses. The lessons also informed workers of the importance of reporting work-related injuries and how to get assistance at the local and state level. A third lesson, about avoiding financial scams and not related to occupational health, was also designed and implemented in response to community requests.

Ten-page, 17-by-11-inch flip charts were designed to present each lesson in a novella format to facilitate a storytelling approach that could engage the listener. Color drawings of key ideas from the stories were printed on the side facing the audience, and a script in both Spanish and English was printed on the side facing the promoter. People receiving the lessons also received leave-behind brochures with some of the same graphics, as well as contact information for one of the partners, the Western North Carolina Workers Center. All materials were designed to convey information with minimal required reading, as the target population had generally low literacy.

The program was designed to hire four promoters fluent in Spanish and knowledgeable about different areas of the region and poultry processing work. Each was asked to work up to six hours a week, finding poultry workers and their families and presenting the lessons. Only one lesson was presented at each contact. Afterward, each promoter wrote notes describing the encounter, including any questions or issues that arose requiring additional education for the promoters. Each promoter met weekly with a JUSTA staff member to review these notes and plan work for the following week. For this work, promoters were paid an honorarium of $10 an hour (up to six hours a week) plus mileage expenses.

All promoters attended an initial half-day training. They received information about the JUSTA project, what a lay health promoter is, maintaining confidentiality, and the workers to recruit. Staff members from the partnership modeled the presentation of the flip-chart stories for them. After practicing for a week, promoters met with staff members again and demonstrated a mock lesson. Once they mastered the approach, they started recruiting workers and presenting the lessons. Instructions about writing notes and documenting who received the lessons were reinforced at weekly meetings. When possible, promoters held group meetings with partnership staff so they could share successes and problems. This allowed the promoters to teach each other, with less staff intervention.

Partnership staff used ethnographic methods to collect data for evaluating the program. Staff members interviewed promoters at intervals throughout the process to assess their interpretation of the program and their work. Staff members recorded notes documenting their efforts to recruit and train promoters, their observations of the promoters, and the attitudes and actions of poultry workers and promoters in the communities.

RECRUITING PROMOTERS

During the first year of the project, work focused on Burke County, the westernmost county. To find effective promoters, staff explored recommendations of the two CBOs, which each recommended one person. Both people were middle-aged women fluent in Spanish; one also spoke Quiché, an indigenous language of Guatemala spoken by many of the poultry workers. Both women completed training and worked in the community until one relocated to a city where her husband was offered a new job, and the other was hired into a full-time position at the Workers Center. By visiting local Mexican stores and conversing with the proprietors, partnership staff found one replacement for the western region. Two other promoters in the central area of the study region were also found through informal contacts made by project field staff members who lived in the study area. Only in the easternmost area, Surry and Yadkin counties, was it difficult to find a promoter. This area was the farthest distance from the CBOs, and no field staff lived there. After two promoters (one man and one woman) were trained and both failed to stick with the position, a third promoter was recruited who had previously worked as an interviewer on another project of the partnership. All of the promoters except one have been women. Several have been current or former poultry processing workers. Others have worked in other assembly line jobs.

Recruiting effective promoters took time and persistence. Having the trust of people in the community, such as store or tienda owners and ministers, as well as the support of CBOs was instrumental in finding individuals who understood the promoter position and were comfortable with the tasks to be accomplished. Difficulties encountered reflect the nature of the local Latino population. It is mobile, so individuals recruited as promoters move. In general, individuals in the population are underemployed, so when they find a job that pays more or appears to be more permanent, they take it. In some cases, women have held jobs and worked as promoters, but their ability to fulfill their promoter responsibilities depended on their job schedule and their family support.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

To evaluate the promoter program, we examined the number of contacts made by the promoters and analyzed notes kept by the promoters and field staff to find out (1) whether the promoters or staff had observed changes in behavior and attitudes among workers, (2) whether the promoters had experienced personal development, and (3) what the challenges were in trying to conduct occupational health and safety education using a promoter model. We analyzed the notes using techniques standard for qualitative data analysis.21 That is, the team searched for instances in the notes where the promoters spoke about the three topics (observed changes, personal development, and challenges). The text for each of these was abstracted, and segments related to one topic were reviewed together to produce a summary of the responses. This method allowed the analyst to see patterns and prevented the analyst from being swayed by a single notable event or statement. Representative quotations are provided in the text.

Delivering education to the community

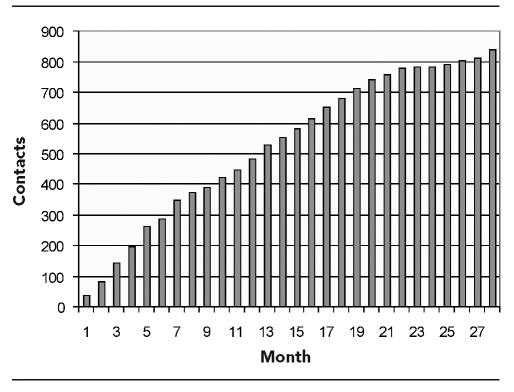

During the course of 28 months (from April 2006 through July 2008), the promoters made 841 different contacts (Figure). These represented a total of 731 workers. Slightly more than half of the people receiving lessons were male (53%). They represented the full range of jobs in the plant: hanger, cutter, puller (one who pulls skin, livers, or gizzards), trimmer, packer, labeler, stacker, and sanitation, with the largest proportion being cutters and trimmers. All 731 received the first lesson on repetitive motion injuries and, of these, 74 also received the lesson on slips and falls. Of these 74, a total of 36 then received the lesson on avoiding financial scams. These 841 contacts were accomplished with a mean of 3.2 promoters working at any time. Changes in the slope of the Figure indicate the varying number of promoters. For example, in September 2006, two new promoters started in the central region, resulting in a sharp increase in contacts in October. The rapid increase at the beginning of the project compared with later months reflected the number of workers available to receive the lessons. As promoters worked through their social networks and came to the point of needing to go beyond individuals they knew well, the number of contacts slowed. Personal issues also led to changes in the rate of contacts. One promoter, for example, had a child and did not work for several months.

Cumulative number of contacts with immigrant poultry processing workers made by lay health promoters in western North Carolina during a 28-month period

Changes in worker behavior and attitudes

Promoters reported that several ideas presented in the lesson on musculoskeletal injuries caused workers to adopt treatment methods. Workers wanted to know how to obtain wrist splints, and one promoter observed, “Before I gave the lessons, people didn't bandage their wrists or use splints. Now I've seen several of the people I've given the lessons to wearing them.” Others began to take ibuprofen to reduce pain or to replace other pain relievers with ibuprofen.

Greater care with preventing unintentional injuries was observed after the lesson on slips and falls. One promoter reported, “Some people said that when they see water on the floor close to the bathrooms, they go and tell their supervisors. Before the lesson, they didn't do that. Some people also told me that when they see a hose or anything on the floor, they try to pick [it] up. Before the lesson, they didn't do that.” Activities that might benefit all workers rather than just an individual were thought unrealistic by the promoters, as well as some workers, when the lesson was first introduced. Promoters argued that any altruism or collective concern based on this lesson was unlikely.

Changes in both attitudes and behavior were also noted as a result of the training on workers' rights. Promoters reported that before listening to the lesson, “the majority of the people were afraid of fighting for their rights. Now, they have the courage to do it.” The promoters reported that workers who had been fearful or timid about speaking up at work felt empowered after receiving the lesson and began speaking out in ways that were consistent with what was illustrated in the lessons. One of the promoters, for example, reported a conversation with a female worker that indicated immigrant workers were starting to recognize that they had the same rights as the American workers:

[This worker] said that before listening to the story, she had never heard anybody saying no when a supervisor asked them to do a task that nobody wanted to do. And now, she started hearing it. She gave me an example of something that happened last week. Her supervisor asked an American woman to move to another station [to hang chickens] and she told him that she wouldn't do it because she had pain in her arms. Several Americans usually say no when they don't want to be moved to other tasks, and the supervisors are okay with that.… [The supervisor] also asked [another Latina] and she responded no. That Latina said that she asked her supervisor why she should say yes if the other two women had told him no. He responded that the other women had doctors' notes saying that they had arm pain. And she told him that she could also get a note from the doctor because she also had pain. After that, the supervisor asked one of her [Latina] coworkers the same thing and she also responded no.

The promoter also reported on changes in her own behavior after learning through her work as a promoter about workers' rights:

In the department [where] I used to work, for example, the supervisor mistreated us and … we wouldn't do or say anything. Now, however, since we found out that we have rights, four of us got together and went to the office. We told the manager the way the supervisor was treating us. As soon as we did that, the supervisor started treating us better. From that moment, anytime a worker was mistreated or discriminated against, we went to [the] office to complain. They started calling us the “four bad girls.”

However, this newfound assertiveness was not without consequences. This promoter was subsequently “promoted” to a position in the plant that reduced her contact with other Latino workers.

Promoters' personal development

The promoters reported that they had changed as a result of the program. One change included being more aware of the situation faced by the Latino community. As one promoter noted, “Before becoming a promoter, I couldn't see what was going on around me in the plant. Now I try to see and understand everything that's happening in the plant and in the community.” Several promoters also reported that they had become more tolerant, understanding why workers might not want to talk with them or learning to talk with people they did not personally like. For some of the women, their work as promoters had forced them to become more tolerant of workers from religions different from their own.

Being a promoter improved the women's self-esteem, though it was not without worries. “People see me as a leader,” one promoter explained. “That makes me feel good, but sometimes it scares me because I think the company might retaliate against me.” Another promoter reported that “being able to go out and talk to people has helped me with my stress level. I feel that my self-esteem has improved.”

Being a promoter even changed family dynamics. “I've had the courage to grow as a person,” one promoter noted. “I've been able to make my husband realize that it's important to me. He's changed and is more supportive now.” For another promoter, the fact that JUSTA project staff had taught her to drive and helped her get a driver's license was something that she would never forget. “Thanks to being a promoter, I learned how to drive, which gives me more independence,” she said.

Project staff observations supported these self-reports. These women were proud of the economic contributions they were making to their families, and glad to have the independence to spend it in ways they chose. The skills they acquired opened new doors for them. One promoter was hired as an instructor for a local literacy project, and two others found jobs as office staff members at the Workers Center. All of the promoters were invited to attend and speak at a conference in Nashville, Tennessee, to help design promoter programs elsewhere. The trip, with JUSTA and CBO staff, offered the promoters additional opportunities for independence and for demonstrating their recently acquired skills and knowledge.

Challenges of conducting health and safety training using a promoter model

Promoters experienced a number of challenges. These started at home where husbands of female promoters at first resisted their promoter activities outside the home or were concerned about their interactions with other men. The promoters often scheduled times to meet with workers, only to be “stood up” or to find that the workers had other obligations. Some workers would not participate out of fear that their employer would find out and retaliate against them. In some cases where the workers spoke an indigenous language, the workers' Spanish skills were not adequate to really understand abstract information about workers' rights.

Partnership members who trained and supervised the promoters also encountered challenges. Because the promoters were largely nontraditional learners and learned at different speeds, supervisors had to learn to limit the amount of information given to them at any one time. Once promoters had mastered a task, they could move on to the next task. For example, the promoters needed to learn what information they should record about their activities, and then learn how to organize it into notes. Flexibility was also important, working around the promoters' schedules to meet with them, as well as understanding their personal problems and how these might affect their productivity. These meetings kept the promoters focused on their work and held them accountable for putting in the time they had promised.

Because being a promoter was a new venture for all of the women, supervisors learned that frequent praise for their accomplishments helped bolster the promoters' self-esteem. Supervisors had to help the promoters stay up-to-date with important local, state, and national events affecting immigrants, as participants frequently asked promoters questions about these events. Finally, supervisors had to realize that the promoters were not wholly driven by altruism. The honorarium that they received, while small, was critical for their participation in the program. The money represented independence from their husbands and gave them a sense of accomplishment. Because of the importance of the honorarium, it was usually not possible to ask them to commit extra hours in a week (e.g., for training) and also deliver the lessons.

DISCUSSION

Lay health promoter programs with immigrant and other disadvantaged populations have received substantial popular support. However, few have been implemented in the area of occupational health and safety beyond farmwork.16–19,22 Evaluations of lay health promoter programs are quite limited,14 perhaps because the nature of the program (casual, informal contacts among acquaintances to impart information) does not lend itself to intensive data collection.

The evaluation described in this article used ethnographic techniques of participant observation (by promoters and project staff) and extensive note-taking based on these observations. This evaluation suggests that promoter programs can be successful in several ways. They can provide information to workers concerning occupational injuries and illnesses that may not be attributed to events at the workplace. Because promoter programs focus on educating workers in ways that are culturally and educationally appropriate, they can address culture-specific issues. For example, many of the poultry workers in the North Carolina study area attribute their hand and wrist pain to arthritis caused by repeated exposure to cold water at work, which is consistent with humoral medicine beliefs in Mexico23,24 and which have been seen in other Mexican workers in the U.S.25 Respectfully acknowledging these beliefs while providing an alternative name for the condition, etiology, and treatment, as was done in the first lesson on musculoskeletal injuries, can create greater awareness in workers of the source of their conditions and encourage them to take advantage of resources such as workers' compensation.

The promoter program also provides a safe environment for workers to challenge safety information presented, based on conditions in the workplace, and seek additional information. By interacting with workers in their own language and providing materials in a culturally and educationally appropriate format, promoter programs are often better equipped than worksites to conduct effective health and safety training.

The program evaluated in this article documented changes in workers that demonstrate greater awareness of their rights to a safe workplace as well as changes in their attitudes to promote safety. Reports of notifying supervisors of hazards or of removing hazards themselves were largely unexpected by the promoters. They argued with program staff that altruism or collective concern as a result of the second lesson was unlikely. Perhaps because the promoter program in itself demonstrated concern for other workers by those of a similar background, some changes in attitude occurred, thereby building a feeling of community among immigrant workers. As Fink argued in his analysis of Guatemalan poultry processing workers in western North Carolina, attempts at collective action work if they are consistent with existing cultural patterns of community action.26

Our evaluation of this promoter program goes beyond other published reports on promoter programs to present the concrete hardships experienced by the promoters and the project staff (for an exception, see Sharp and colleagues27). In contrast to the uncritical manner in which promoter programs are typically recommended, this article demonstrates that promoters have difficulty mastering some skills and balancing their work as promoters with their family obligations. It also shows that ongoing supervision of the program is necessary to recruit and retain competent promoters and to troubleshoot the obstacles, both personal and community-related, that the promoters face. Other types of promoter programs have relied on retirees, some with pensions, to work in the community. The immigrant Latino community, which is fairly young, lacks such resources.

One of the results of the program was the increase in promoters' self-esteem and skills. Booker, in a study of camp health aides trained to deliver general health care in farmworker camps, also found that promoter self-esteem was enhanced by being a lay health promoter.22 The loss of promoters to regular jobs in the community, while a loss for the promoter program, represents a gain for the community of a more skilled worker.

Limitations

While the results of this ethnographic evaluation are suggestive, their limitations must be acknowledged. Many of the data were self-reported by the promoters, based on their interpretations of worker behavior after the worker received the intervention and their observations in the plants and communities. More objective data would have been preferable. Full details were not available on the recipients of the lessons, and this information would also have been helpful. However, collection of these data would have altered the interaction of the promoters and workers by changing the promoters' role. Because so many of the workers were afraid to provide much information about themselves, program staff made the decision to limit information obtained in the interest of gaining program acceptance in the community.

Despite these limitations, the evaluation had considerable strengths. A large number of workers were contacted across several counties and represented multiple poultry processing plants and companies. Promoters kept notes that provided insight into and details about the reception of the program that might not have been available from a quantitative evaluation based on worker reports.

CONCLUSION

A lay health promoter program does not substitute for the occupational health and safety training conducted in plants by employers or unions. However, our results suggest that promoter programs in the community can be an important adjunct to these efforts, particularly among immigrant workers. More research is needed regarding the implementation and evaluation of promoter programs in other industries, such as construction, that also employ large numbers of immigrant workers and have high rates of injury.

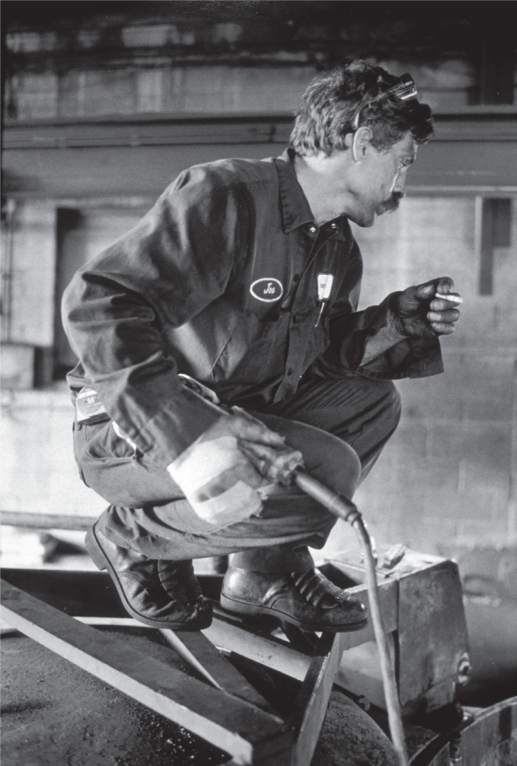

Photo: David L. Parker

REFERENCES

- 1.Striffler S. Chicken: the dangerous transformation of America's favorite food. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipscomb HJ, Argue R, McDonald MA, Dement JM, Epling CA, James T, et al. Exploration of work and health disparities among black women employed in poultry processing in the rural south. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1833–40. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Government Accountability Office (US) Report to the ranking minority member, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, U.S. Senate (report no. GAO-05-96) Washington: GAO; 2005. Workplace safety and health: safety in the meat and poultry industry, while improving, could be further strengthened. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Marín A, Carrillo L, Burke B, Coates ML, et al. Work-family conflict: experiences and health implications among immigrant Latinos [published erratum appears in J Appl Psychol 2008;93:922] J Appl Psychol. 2007;92:1119–30. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor (US) Table SNR05. Incidence rate and number of nonfatal occupational injuries by industry, 2004. [cited 2005 Dec 7];2005 Nov; Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ostb1479.pdf.

- 6.Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor (US) Table SNR08. Incidence rates of nonfatal occupational illness, by industry and category of illness, 2004. [cited 2005 Dec 7];2005 Nov; Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/ostb1482.pdf.

- 7.Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor (US) Table SNR12. Highest incidence rates of total nonfatal occupational illness cases, private industry, 2004. [cited 2005 Dec 7];2005 Nov; Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/ostb1486.pdf.

- 8.National Research Council. Safety is seguridad: a workshop summary. Washington: National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Human Rights Watch. Blood, sweat, and fear: workers' rights in U.S. meat and poultry plants. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azaroff LS, Levenstein C, Wegman DH. Occupational injury and illness surveillance: conceptual filters explain underreporting. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1421–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quandt SA, Grzywacz JG, Marín A, Carrillo L, Coates ML, Burke B, et al. Illnesses and injuries reported by Latino poultry workers in western North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49:343–51. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidden tragedy: underreporting of workplace injuries and illnesses. Washington: U.S. House of Representatives; 2008. Committee on Education and Labor, U.S. House of Representatives. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffith D. Consequences of immigration reform for low-wage workers in the southeastern U.S.: the case of the poultry industry. Urban Anthropol. 1990;19:155–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: a qualitative systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:418–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions. [cited 2008 Mar 16];Community health workers national workforce study, 2007. Available from: URL: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/chw.

- 16.Arcury TA, Marín A, Snively BM, Hernández-Pelletier M, Quandt SA. Reducing farmworker residential pesticide exposure: evaluation of a lay health advisor intervention. Health Promot Pract 2008 Feb 20. doi: 10.1177/1524839907301409. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liebman AK, Juarez PM, Leyva C, Corona A. A pilot program using promotoras de salud to educate farmworker families about the risk from pesticide exposure. J Agromedicine. 2007;12:33–43. doi: 10.1300/J096v12n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forst L, Lacey S, Chen HY, Jimenez R, Bauer S, Skinner S, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers for promoting use of safety eyewear by Latino farm workers. Am J Ind Med. 2004;46:607–13. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luque JS, Monaghan P, Contreras RB, August E, Baldwin JA, Bryant CA, et al. Implementation evaluation of a culturally competent eye injury prevention program for citrus workers in a Florida migrant community. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2007;1:359–69. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2007.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Marín A, Carrillo L, Coates ML, Burke B, et al. The organization of work: implications for injury and illness among immigrant Latino poultry-processing workers. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2007;62:19–26. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.62.1.19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Booker VK, Robinson JG, Kay BJ, Najera LG, Stewart G. Changes in empowerment: effects of participation in a lay health promotion program. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:452–64. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubel AJ. Concepts of disease in Mexican-American culture. Am Anthropol. 1960;62:795–814. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weller SC. New data on intracultural variability: the hot-cold concept of medicine and illness. Hum Org. 1983;42:249–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Austin CK, Saavedra R. Farmworker and farmer perceptions of farmworker agricultural chemical exposure in North Carolina. Hum Org. 1998;57:359–68. doi: 10.17730/humo.57.3.n26161776pgg7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink L. The Maya of Morganton: work and community in the Nuevo New South. Chapel Hill (NC): University of North Carolina Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp PC, Dignan MB, Blinson K, Konen JC, McQuellon R, Michielutte R, et al. Working with lay health educators in a rural cancer-prevention program. Am J Health Behav. 1998;22:18–27. [Google Scholar]