Abstract

Muscle contraction and relaxation is regulated by transient elevations of myoplasmic Ca2+. Ca2+ is released from stores in the lumen of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum (SER) to initiate formation of the Ca2+ transient by activation of a class of Ca2+ release channels referred to as ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and is pumped back into the SER lumen by Ca2+-ATPases (SERCAs) to terminate the Ca2+ transient. Mutations in the type 1 ryanodine receptor gene, RYR1, are associated with 2 skeletal muscle disorders, malignant hyperthermia (MH), and central core disease (CCD). The evaluation of proposed mechanisms by which RyR1 mutations cause MH and CCD is hindered by the lack of high-resolution structural information. Here, we report the crystal structure of the N-terminal 210 residues of RyR1 (RyRNTD) at 2.5 Å. The RyRNTD structure is similar to that of the suppressor domain of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3Rsup), but lacks most of the long helix-turn-helix segment of the “arm” domain in IP3Rsup. The N-terminal β-trefoil fold, found in both RyR and IP3R, is likely to play a critical role in regulatory mechanisms in this channel family. A disease-associated mutation “hot spot” loop was identified between strands 8 and 9 in a highly basic region of RyR1. Biophysical studies showed that 3 MH-associated mutations (C36R, R164C, and R178C) do not adversely affect the global stability or fold of RyRNTD, supporting previously described mechanisms whereby mutations perturb protein–protein interactions.

Keywords: nuclear magnetic resonance, X-ray crystal structure, malignant hyperthermia, central core disease

In skeletal muscle cells, the release of Ca2+ into the cytosol from stores in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) couples surface membrane depolarization to sarcomere shortening, in a process known as excitation-contraction (E–C) coupling (1). Membrane depolarization is sensed by Cav1.1, the α1-subunit of the sarcolemmal Ca2+ channel, causing it to undergo voltage-induced conformational changes that activate the SR Ca2+ release channel, the ryanodine receptor (RyR1). Cardiomyocytes, in contrast, use a change in intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i as the primary trigger for RyR-mediated release of Ca2+ from the SR (2). This process is often referred to as calcium-induced calcium release (CICR).

Three isoforms of RyR have been characterized: RyR1, associated with skeletal muscle; RyR2, associated with cardiac muscle; and RyR3, which is expressed more ubiquitously (2). RyRs are the largest known ion channels, each composed of 4 identical subunits that contain ≈5,000 residues depending on the isoform (3). Each subunit consists of a cytoplasmic region that accounts for at least 4,300 of the 5,000 amino acids in the protein and a transmembrane (TM) domain that consists of at least 6 and possibly 8 TM helices (4). The cytoplasmic domain contains regions involved in protein–protein interactions involved in E–C coupling, binding of activating ligands and interdomain interactions that, together, decode these signals and relay them to the Ca2+ pore region located within the TM domain (5). Several human diseases arise from mutations in RyR1 and RyR2 (6, 7). Most RyR1 mutations are clustered in 3 distinct regions: cytosolic N-terminal (1–614); cytosolic central (2,117–2,458); and C-terminal membrane (4,136–4,973) (8), although these boundaries are becoming more diffuse as more causal mutations are reported. RyR mutants fall into 3 classes: leaky mutants with increased sensitivity to Ca2+ release channel activators (9); E–C uncoupled mutants with partial or complete loss of Ca2+ release activity in the presence of a normal SR Ca2+ store (10); and mutants that have a lowered threshold for store overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR) (11). Although much is known about the influence of these disease mutations on function, little is known about their effects on RyR structure.

RyRs are responsible for the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores within excitable cells, whereas inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) assume this role in nonexcitable cells. RyR1 and IP3R1 are members of a superfamily of tetrameric Ca2+ release channels that share the same basic architecture and have a bell-shaped Ca2+ dependence with respect to CICR. In previous work, Bosanac et al. (10, 11) determined the crystal structures of 2 contiguous N-terminal domains of IP3R1: IP3Rsup (1–223) and IP3R-core (224–604), yet no high-resolution structure was available for any part of RyR. Nevertheless, bioinformatic analysis predicted 4 conserved repeats in the N terminus of both RyR1 and IP3R1 (residues 1–600), designated Mannosyltransferase, IP3R, and RyR (MIR) motifs (9). Here, we present the crystal structure of an N-terminal domain (1–210) of rabbit RyR1 (RyRNTD), which contains the first 2 MIR motifs (residues 112–166 and 152–203), as described. This sequence contains 11 disease-associated mutations. In our crystal structure, we show that these mutations form a cluster that we call the hot spot loop (HS-loop). Selected mutations within or near the HS-loop were investigated for their effects on structural stability and fold. The conservation that we have noted between RyR1 and IP3Rsup provides evidence for the importance of this N-terminal region in channel function. The present study not only reveals a high-resolution structure of RyR, but also sheds light on the structure-function relationship between RyRs and IP3Rs.

Results

Structure in Crystal and Solution.

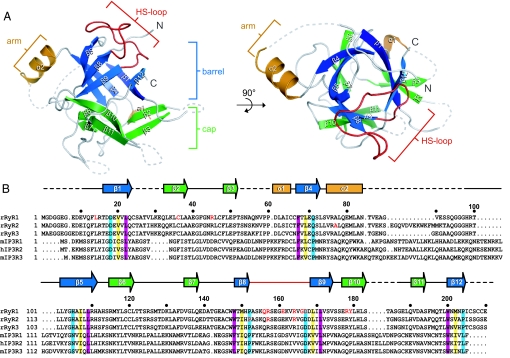

We crystallized RyRNTD and solved its structure by using IP3Rsup (1XZZ) as a search model for molecular replacement. Our structure (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1, and Table S1) reveals not only that RyRNTD contains MIR domains, but that it adopts a β-trefoil structure similar to that observed in IP3Rsup. This fold, which is found among proteins with distinctly different functions, consists of 3 trefoils coming together to form a barrel and cap (12). Each trefoil consists of 4 β-strands: 2 for the cap and 2 for the barrel (Fig. 1A). In addition, our structure contains a short protrusion between β4 and β5, which we call the arm domain, in keeping with the nomenclature for the corresponding structure of IP3Rsup. Several sequences were not built into our model because of poorly defined electron density, including a region (V86 to G97) predicted to form a second helix (α3) in the arm domain.

Fig. 1.

Features of the RyRNTD structure. (A) Ribbon diagram of rabbit RyRNTD. The β-trefoil structure is separated into barrel (blue strands) and cap (green strands). Dotted lines represent missing residues. A top-down view is shown on the right side. (B) Sequence alignment of the distal N-terminal residues of RyR and IP3R isoforms. Residues highlighted in teal, yellow, and magenta denote conservation in the different layers of the barrel in both RyRNTD and IP3Rsup. Residues in red text correspond to mutations sites in RyR1 that lead to MH or CCD, as well as to catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD2) for RyR2.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments were carried out to probe the structure of RyRNTD in solution. A construct consisting of RyR1 10–210 (RyR10–210) was used to assign the protein backbone of this region (Fig. S2 A and B). RyR10–210 was used because of its reduced spectral overlap compared with RyRNTD. A suite of transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)-based 3D experiments were used to achieve approximately 86% assignment of the protein backbone in the 1H-15N TROSY-heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (TROSY-HSQC) spectrum of RyR10–210. A chemical shift index (CSI) generated from the NMR chemical shift data are in excellent agreement with the location and number of secondary structure elements determined from the crystal structure (Fig. S2C). The presence of a second helix in the arm domain of RyRNTD was not supported by the NMR data. First, CSI values of residues residing in the proposed helix agree more with an unstructured region and, second, peak intensities from the HSQC spectrum of these residues are 2-fold larger than the average for the entire structure, suggesting that they reside in an unstructured region (Fig. S2D). However, because our structure is in isolation from the rest of the receptor, it is also possible that this unstructured region may be folded when present in the intact receptor.

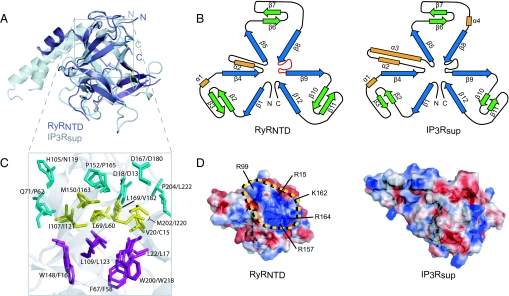

Structural Comparison of RyRNTD and IP3Rsup.

The primary sequence identity between RyRNTD and IP3Rsup is relatively low (30%). However, the backbone conformation of RyRNTD superimposes very well with IP3Rsup (Fig. 2A), with rmsd of 1.34 Å. The topology diagrams of RyRNTD and IP3Rsup (Fig. 2B) illustrate the structural similarity of their β-trefoil fold, as well as their 3-fold symmetry. Key residues residing in β-strands making up the barrel are conserved in RyRNTD (Fig. 1B). Remarkably, these residues stack into discernible layers in the barrel, with similar orientations to those seen in IP3Rsup (Fig. 2C), providing an extensive hydrophobic core for the structure. However, this high similarity ends abruptly at the beginning of the unconventional helical segment found in the arm domain. In RyRNTD, this domain measures ≈23 Å in length and consists of a short α-helix (α2) and a coil region, whereas in IP3Rsup it measures 45 Å in length and is made up of a short (α2) and a long (α3) helix. Another striking difference between RyRNTD and IP3Rsup is evident when comparing surface charge representations of the 2 structures (Fig. 2D). RyRNTD contains a large patch of positive charge at the top of the β-trefoil structure, which coincides with the location of many disease-associated mutations in RyR1.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of RyRNTD and IP3Rsup structures. (A) Structural alignment of RyRNTD (purple) and IP3Rsup (gray) structures. Topology diagram for both structures are shown in B. The 3-fold symmetry of the β-trefoil is evident, as well as differences in the arm domain. The layering of residues in the barrel is shown in C with the same color scheme as in Fig. 1B. Electrostatic surface representation is represented for IP3Rsup and RyRNTD in D. A positive patch where mutations cluster is outlined in yellow. Residues with basic side groups found within and around the HS-loop are labeled. The structure is oriented in the top-down view described in Fig. 1A.

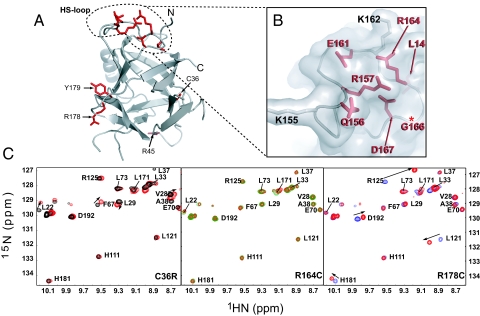

MH- and CCD-Associated Mutations.

In MH and CCD patients, 30 mutations have been identified thus far that lie within the first 614 amino acids of RyR1. Of these, 11 map onto the structure of RyRNTD (Fig. 3A) and 6 are located on the loop between β8 and β9 (Q156, R157, E161, R164, G166, D167), also known as the HS-loop (Figs. 1A and 3B).

Fig. 3.

Mapping and analysis of mutants on RyRNTD structure. (A) Mapping of residues known to be mutated in MH and CCD. (B) Close up view of HS-loop where mutations are concentrated. Residues with basic side groups in the HS-loop are shown in gray. (C) Overlay of mutant (red peaks) and wild-type (black, green, and blue) 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra in the downfield region. Peaks showing significant chemical shift perturbations are indicated by arrows.

To examine structural influences of RyRNTD mutations, we chose 3 MH-associated mutations: C35R, R163C, and R177C in human or C36R, R164C, and R178C in the rabbit sequence that we have used for structure determination. R164 is present in the HS-loop, whereas C36 and R178 are found within the β-strands that form part of the “cap” of the β-trefoil. Circular dichroism and chemical denaturation experiments showed no appreciable effect on structural stability and integrity due to the point mutations (Fig. S3). These data were consistent with NMR studies using 1H-15N HSQC, which showed conservation of the overall fold. Comparison of R164C mutant and wild-type spectra revealed negligible chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) (Fig. 3C Center). This is not surprising, because this mutation is present on a surface-exposed loop in isolation from most of the structure. However, the C36R and R178C mutations produced more notable CSPs. However, close inspection of the changes indicated that these shifts were localized to residues in close proximity to the mutation site, suggesting that little alteration occurred in the protein fold itself (Fig. 3C Right and Left). These results demonstrate that the point mutations (C36R, R164C, and R178C) do not perturb the global structural integrity of RyRNTD.

CPVT and ARVD Mutations in Type 2 RyR (RyR2).

Sequence identity among the 3 isoforms of RyR is high: 67% overall between human RyR1 and RyR2 and 78% when the N-terminal domains are compared (RyR1 1–210 and RyR2 1–223). In light of this high sequence identity, we used a homology model to build a structural model of the RyR2 N-terminal domain (1–223) using MODELLER 6.2 (13). We excluded 12 residues located in the hypothetical arm domain of RyR2. Interestingly, these residues, which are missing in RyR1, may comprise the second helix (α3) in the helix-turn-helix motif seen in IP3Rsup. Studies have shown that a mutation in RyR2 (R176Q) causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD2) in humans and ventricular tachycardia and cardiomyopathy in a mouse model of ARVD2 (14) whereas another RyR2 mutation, R169Q, has been implicated in exercise-induced bidirectional ventricular tachycardia (15). These mutations correspond to the R163C and R156K MH-associated mutations, respectively, in human RyR1, illustrating a conservation of function in this region between RyR1 and RyR2. Mapping of these and other RyR2 mutations onto the homology model of RyR2 revealed a similar clustering to RyR1 mutations (Fig. S4), supporting the significance of HS-loop mutations in RyR human diseases. Furthermore, sequence analysis indicated that, within the distal N-terminal region, the HS-loop is most conserved among other eukaryotes (Fig. S5).

Discussion

The elucidation of the RyRNTD structure demonstrates the conserved structural characteristics of the 2 Ca2+ release channels, RyR and IP3R, and suggests a key regulatory role for RyRNTD. The structure of RyRNTD is the second example, after IP3Rsup, of an insertion of a long sequence into a β-trefoil structure (10). However, intriguing differences do exist between RyRNTD and IP3Rsup. In RyRNTD, the arm domain lacks the long α3 helix and is significantly shortened relative to IP3Rsup. The arm domain in IP3Rsup is the site for several protein–protein interactions of key IP3R regulators such as calmodulin (CaM) and CaBP-1 (10). In RyR1, the binding domain for CaM has been located to residues (3,614–3,643) (16). Apparently, these 2 Ca2+ release channels developed different modes of CaM interaction, which is not surprising as CaM can bind numerous targets in different ways (17).

The 3-dimensional clustering of disease-associated mutations within the highly localized distal N-terminal region of RyR1 (i.e., the HS-loop) implies a significant role for the β-trefoil domain structure in RyR function. Interestingly, the same structural architecture is found in IP3R1 where the function is better understood compared with RyRs. In IP3R1, this domain plays an essential role in both the regulation of IP3 binding affinity and coupling between the N-terminal suppressor and C-terminal channel domains, hence it is referred to as the suppressor/coupling domain (18, 19). An IP3R1 mutant lacking the suppressor domain (1–223) displayed high affinity for IP3 but was unable to exhibit any measurable Ca2+ release, suggesting a mechanism wherein the ligand binding signal is transmitted to the channel domain via the suppressor/coupling domain (20). Furthermore, evidence for a direct interaction between the N-terminal region (1–340) and the channel domain has been reported (21).

RyRs do not use IP3 for activation and, therefore, RyRNTD lacks this ligand binding and modulation function. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the coupling function of this domain may be retained. Using the domain peptide (DP) method established by Ikemoto and coworkers (22), it has been demonstrated that the N-terminal and central regions interact to modulate channel gating. Some of the peptides were capable of increasing the open probability (P0) of single RyR channels (22, 23) and even of inducing Ca2+ release from skinned fibers or rat muscle (24). Most importantly, a fluorescently labeled N-terminal RyR2 peptide (residues 163–195) was capable of disrupting interdomain interactions within the tetrameric channel and increasing Ca2+ leak and spark frequency in canine ventricular myocytes (25). This peptide also corresponds to the region that contains the putative HS-loop in the RyR2 homology model. It should be noted that this region, which is highly positively charged (Fig. 2D), may interact with an acidic stretch of RyR to couple channel activation. Together, these studies strongly argue for the functional importance of the N-terminal segment in RyR channel gating function, possibly through interdomain interactions.

However, our findings do not exclude the possibility of another scenario recently suggested by Serysheva and coworkers (26). Their elegant cryo-EM and modeling studies have shown that the homology-modeled structures comprising Q12–S207 and G216–T565 can be docked onto the clamp region of RyR1. Interestingly, their docking studies place the HS-loop region on the protein surface where FK506 binding protein (FKBP12) is proposed to bind. The authors hypothesize that the interaction between RyR1 and FKBP12, which is proposed to stabilize RyR1 in the closed state, is perturbed by MH/CCD-associated mutations; thereby altering gating of the RyR1 channel. At the level of resolution provided by EM (≈9.5 Å), the present experimentally determined crystal structure of RyRNTD does not improve further the proposed location and orientation of the homology model of Q12-S207 in the EM density.

The present study provided structural insight into the conformational coupling mechanism of RyR1; (i) RyR1 possesses a β-trefoil fold at the N terminus, which is closely related to the suppressor/coupling domain of IP3R1, (ii) disease-associated mutations are clustered at the HS-loop between β8 and β9, and (iii) the highly basic region around the HS-loop may participate in interactions with the central region via electrostatic interactions. The present study provides the atomic-resolution 3-dimensional structure of the RyR1 N-terminal region; further studies are required to delineate a complete picture of the complex machinery of RyR Ca2+ channels.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Constructs for rRyR1 were subcloned into a pET32a expression vector (Novagen) and expressed with an N-terminal polyHis-tag in BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells at 15 °C for ≈12 h using 0.2 mM IPTG induction. Triple labeled NMR samples were expressed as described above and uniformly labeled with 13C, 15N and Deuterium (Spectra Stable Isotope Group). Protein samples were purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), followed by thrombin cleavage overnight at 4 °C in dialysis tubing. The cleaved protein was further purified by anion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. Amino acid mutations were introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutant constructs were expressed and purified as outlined above.

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Rabbit RyR1 1–210 (RyRNTD) was concentrated in 20 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, and 1 mM TCEP to a final concentration of 7.5 mg/mL. Initial crystals of RyRNTD were grown by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at 298K by combining 1.5 μL protein solution with 1.5 μL well solution (100 mM MES, 100 mM MgCl2, 24% wt/vol PEG 3350, and 5 mM DTT). Crystals grew as clusters of thin plates after 3–4 days. A series of microseedings were required to obtain single plate crystals with dimensions of 0.1 × 0.4 × 0.05 mm3. Crystals were transferred to a cryo-protectant solution containing 20% vol/vol glycerol before a native dataset was collected to 2.5 Å at the Advanced Photon Source Synchrotron facility (Argonne, IL). This was done at 100 K on the 19-BM beam line at X-ray wavelength 0.9793. Data processing and reduction were carried out with HKL2000 (27). Crystals belonged to the space group C2 with cell dimensions a = 140.6 Å, b = 35.3 Å, and c = 78.9 Å with the angle β = 99.4°. Two molecules were present in the asymmetric unit.

Structure Solution and Refinement.

A polyalanine model of the IP3Rsup structure, (Protein Data Bank ID code 1XZZ), was used for molecular replacement to obtain phase information using PHASER (28). Model building was performed with Coot (29) followed by iterative rounds of refinement using simulated annealing and positional refinement in CNS (30). The final model was validated using PROCHECK (31), with 88.2% in the most favored regions and 11.8% in allowed regions.

NMR Analysis of N-Terminal rRyR1 10–210 and RyRNTD Mutants.

Protein samples for NMR backbone analyses contained 0.6 mM uniformly 15N/13C/2H-labeled RyR1 10–210 in 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM TECP, and 10% (vol/vol) D2O. 15N-labeled RyRNTD mutants were concentrated as described above. Experiments were carried out at 288 K on an 800 MHz Bruker spectrometer equipped with a cryogenically cooled triple resonance probe. A 15N transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (TROSY-HSQC) experiment was performed on the triple labeled sample. Sequential backbone assignments were carried out next using the following suite of TROSY-based 3-dimensional experiments: HNCO, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(COCA)CB, and HNCACB. The 2- and 3-dimensional spectra were processed, and resonance assignments were made using NMRPipe (32) and XEASY (33), respectively.

Experiments on RyRNTD mutants were carried out at 288 K on a 600 MHz Bruker spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic, triple resonance probe. TROSY-HSQC spectra were processed as above and visualized using NMRView (34).

Optical Spectroscopy.

Far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded on a J-815 CD Spectrometer (Jasco). Data were collected in 1-nm increments using a 0.1-cm-path length (l) cell, 10-s averaging time, and 1-nm bandwidth. Spectra were corrected for buffer contributions. Fluorescence measurements were made on a RF-5301PC fluorimeter (Shimadzu), and data were collected in 1 mL (l = 1 cm) cuvettes using excitation and emission slit widths of 3 and 10 nm, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the staff of 19-BM at APS for help in data collection, T.K. Mal for his NMR assistance, and P. Stathopulos for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada grant (to M.I.), Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MT-3399 (to D.H.M.), and Canadian Foundation for Innovation grant for 800 and 600 MHz NMR spectrometers (to M.I.) N.I. is a recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research postdoctoral fellowship. M.I. holds the Canada Research Chair in Cancer Structural Biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 3HSM).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905186106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Meissner G. Ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels and their regulation by endogenous effectors. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:485–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.002413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischer S. Personal recollections on the discovery of the ryanodine receptors of muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du GG, et al. Topology of the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (RyR1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16725–16730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012688999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George C, Yin C, Lai F. Toward a molecular understanding of the structure-function of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2005;42:197–222. doi: 10.1385/CBB:42:2:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George CH, et al. Ryanodine receptors and ventricular arrhythmias: Emerging trends in mutations, mechanisms and therapies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson R, et al. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:977–989. doi: 10.1002/humu.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yano M, et al. Mechanisms of disease: Ryanodine receptor defects in heart failure and fatal arrhythmia. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3:43–52. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponting CP. Novel repeats in ryanodine and IP3 receptors and protein O-mannosyltransferases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosanac I, et al. Crystal structure of the ligand binding suppressor domain of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Mol Cell. 2005;17:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosanac I, et al. Structure of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding core in complex with its ligand. Nature. 2002;420:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature01268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez LL, et al. Multiple routes lead to the native state in the energy landscape of the beta-trefoil family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10254–10258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510110103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kannankeril PJ, et al. Mice with the R176Q cardiac ryanodine receptor mutation exhibit catecholamine-induced ventricular tachycardia and cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12179–12184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600268103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsueh C-H, et al. A novel mutation (Arg169Gln) of the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene causing exercise-induced bidirectional ventricular tachycardia. Int J Cardiol. 2006;108:276–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi N, Xin C, Meissner G. Identification of apocalmodulin and Ca2+-calmodulin regulatory domain in skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel, ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22579–22585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeflich KP, Ikura M. Calmodulin in action: Diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell. 2002;108:739–742. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikoshiba K. IP3 receptor/Ca2+ channel: From discovery to new signaling concepts. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1426–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devogelaere B, et al. The complex regulatory function of the ligand-binding domain of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uchida K, et al. Critical regions for activation gating of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16551–16560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schug ZT, Joseph SK. The role of the S4–S5 linker and C-terminal tail in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24431–24440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikemoto N. In: Ryanodine Receptors: Structure, Function, and Dysfunction in Clinical Disease. Wehrens XHT, Marks AR, editors. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto T, El-Hayek R, Ikemoto N. Postulated role of interdomain interaction within the ryanodine receptor in Ca2+ channel regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11618–11625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb GD, et al. Effects of a domain peptide of the ryanodine receptor on Ca2+ release in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C207–C214. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tateishi H, et al. Defective domain-domain interactions within the ryanodine receptor as a critical cause of diastolic Ca2+ leak in failing hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:536–545. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serysheva, et al. Subnanometer-resolution electron cryomicroscopy-based domain models for the cytoplasmic region of skeletal muscle RyR channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9610–9615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803189105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. In: Macromolecular Crystallography Part A. Carter CW Jr, editor. New York: Academic; 1997. pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR System: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski RA, et al. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartels C, et al. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00417486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. NMR View: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.