Abstract

Theories of empathy suggest that an accurate understanding of another's emotions should depend on affective, motor, and/or higher cognitive brain regions, but until recently no experimental method has been available to directly test these possibilities. Here, we present a functional imaging paradigm that allowed us to address this issue. We found that empathically accurate, as compared with inaccurate, judgments depended on (i) structures within the human mirror neuron system thought to be involved in shared sensorimotor representations, and (ii) regions implicated in mental state attribution, the superior temporal sulcus and medial prefrontal cortex. These data demostrate that activity in these 2 sets of brain regions tracks with the accuracy of attributions made about another's internal emotional state. Taken together, these results provide both an experimental approach and theoretical insights for studying empathy and its dysfunction.

Keywords: empathy, fMRI, medial prefrontal cortex, mirror neuron system, social cognition

Understanding other people's minds is one of the key challenges human beings face. Failing to meet this challenge is extremely costly: individuals with autism spectrum disorders, for example, have difficulties understanding the intentions, thoughts, and feelings of others, and they suffer severe problems with social interactions as a result (1). Given the importance of understanding others, an increasing amount of research has explored the neural bases of social cognition. In general, these studies have followed 1 of 2 quite different paths.

The first has demonstrated that perceivers observing social targets experiencing pain or disgust (2–4), performing goal-directed actions (5–8), posing emotional facial expressions (9, 10), and experiencing nonpainful touch (11, 12) engage the same limbic, paralimbic, or sensorimotor systems that are active when perceivers themselves experience similar states or perform similar actions. These data have motivated the hypothesis that “shared representations” (SRs) of experienced and observed affective, sensory, and motor responses allow perceivers to vicariously experience what it is like to be the target of their perception. This common coding between self and other states, in turn, is thought to aid perceivers in understanding targets emotions or intentions (9, 13, 14).

The second line of research has examined the neural bases of perceivers' mental state attributions (MSAs), that is, expicit attributions about the intentions, beliefs, and feelings of targets. In contrast to the limbic and motor regions thought to support SRs, the network of brain regions recruited during MSA includes temporal and parietal regions thought to control shifts of attention to social cues and medial prefrontal regions thought to derive MSAs from integrated combinations of semantic, contextual, and sensory inputs (15–17), supporting the hypothesis that understanding others is served by explicit inferential processes (18). Interestingly, very few studies demonstrate concurrent activation of regions associated with MSAs and SRs, suggesting 2 relatively independent mechanisms could each support interpersonal understanding.

These 2 lines of research converge to suggest that both SRs and MSAs are involved in processing information about targets' internal states (14, 19, 20). However, whether these or other neural systems underlie accurate understanding of target states remains unknown, because extant methods are unable to address this question. To explore the neural bases of accurate interpersonal understanding, a method would need to indicate that activation of a neural system predicts a match between perceivers' beliefs about targets' internal states and the states targets report themselves to be experiencing (21).

Instead, extant studies have probed neural activity while perceivers passively view or experience actions and sensory states or make judgments about fictional targets whose internal states are implied in pictures or fictional vignettes. In either case, comparisons between perceiver judgments and what targets actually experienced cannot be made. As a consequence, neural activations from these prior studies could involve many cognitive processes engaged by attending to social targets, some, but not all, of which could be related to accurately understanding targets' internal states.

In a broad sense, the knowledge gap concerning the sources of interpersonal understanding is similar to the situation of memory research 10 years ago. At that time, theories had implicated the hippocampus and inferior frontal gyrus in memory formation, but available neuroimaging methods offered no direct evidence for this claim. As such, encoding-related activity in these and other regions could have been related to any number of processes, which may or may not have predicted successful memory formation. The development of the subsequent memory paradigm provided evidence about the functional role of encoding-related neural activity by using it to predict accurate memory retrieval, thereby allowing researchers to directly link brain activity and memory performance (22, 23). Social cognition research faces a similar challenge: theories suggest that activity in regions supporting SRs and/or MSA are involved in perceiving the internal states of others, but extant data do not make clear whether and how these systems support an accurate understanding of others. As was the case with memory research, the solution requires development of a methodology that allows direct links between brain activity and behavioral measures of accuracy.

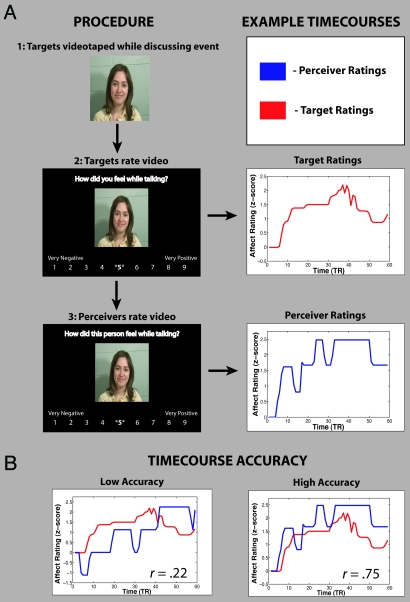

Here, we describe a functional imaging study designed to provide that link by directly probing the neural correlates of an accurate interpersonal understanding. We developed a variant of a naturalistic empathic accuracy (EA) paradigm validated in social psychological research (21, 24, 25) that allowed for exploration of how brain activity tracked with perceivers' accuracy about social targets' effect. Whole-brain fMRI data were collected from 16 perceivers while they watched 6 videos (mean length ≈2.25 min) of social targets discussing emotional autobiographical events. Critically, in a prior phase of the study, each target watched all of their own videos immediately after it was recorded and continuously rated how positive or negative they had felt at each moment while talking. Later, while perceivers watched these videos, they used the same scale targets had used to continuously rate how positive or negative they believed targets felt at each moment. Time-course correlations between targets' own affect ratings and perceivers' ratings of target affect served as our measure of EA (see Methods and Fig. 1). This design allowed for a direct examination of the neural sources of accurate interpersonal understanding, which we explored by using 2 analytic techniques. First, we used whole-brain data to search for brain activity during this task that tracked with perceivers' accuracy about targets' emotions in each video clip. Second, we used a region of interest approach to explore whether activity in brain areas previously implicated in SRs or MSA would predict perceivers' levels of accuracy about social targets.

Fig. 1.

Task design and sample behavioral data.. (A) Outline of procedure. (Top) Targets were videotaped while discussing emotional autobiographical events. (Middle) Immediately after discussing these events, targets watched their videos and continuously rated how positive or negative they had felt while discussing. (Bottom) Perceivers, while being scanned, watched target videos and continuously rated how good or bad they believed targets had felt at each moment while discussing each memory. (B) Time courses from target (red) and perceiver (blue) affect ratings were then correlated to provide a measure of EA.

Results

Behavioral EA.

Overall, perceivers were moderately accurate at inferring target affect, and their accuracy was well above chance (mean r = 0.46, t = 9.72, P < 0.001), replicating previous behavioral results using this task (25, 26).

Neural Correlates of EA.

Whole-brain analysis.

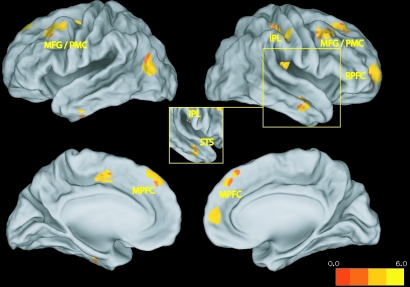

The whole-brain analysis afforded by this paradigm was conceptually similar to those used in subsequent memory research. Here, we used a time-course correlation measure of EA as a parametric modulator to identify brain regions whose average activity during a given video predicted their accuracy about target affect during that video (see Methods and ref. 25 for details). Results revealed that EA was predicted by activity in 3 regions implicated in MSA [dorsal and rostral subregions of medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and the superior temporal sulcus (STS; see Fig. 2 and Table S1; for inaccuracy-related activations, see SI text and Table S2) ] and activity in sensorimotor regions in the mirror neuron system thought to support SRs [right inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and bilateral dorsal premotor cortex (PMC) (5, 6)]. This finding is consistent with the idea that, while perceiving complex emotional displays, accuracy is predicted by a combination of sustained attention to targets' verbal and nonverbal affect cues (including posture and facial expressions that may be processed in the mirror neuron system), and inferences about targets' states based on integration of these cues (which could occur in the MPFC).

Fig. 2.

Parametric analyses isolating regions related to perceivers' accuracy about target affect. (Inset) A rotated view of the right hemisphere displays a cluster in the STS hidden in the lateral view. MFG: middle frontal gyrus; STS: superior temporal sulcus; RPFC: rostrolateral prefrontal cortex.

Regions of interest analysis.

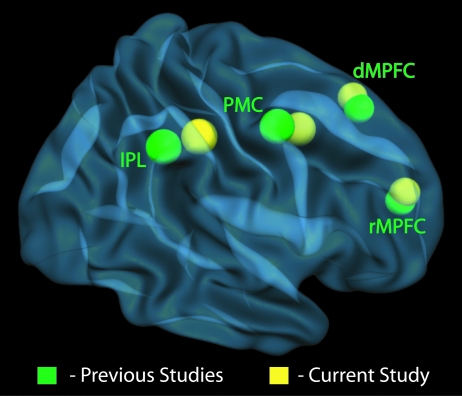

Our second analytic approach sought to confirm the findings of our parametric whole-brain analysis by comparing them to activity extracted from regions of interest defined by activations found in previous studies of SRs and MSA. For this analysis (see SI Text for details) we first calculated mean activation peaks in the bilateral dorsal PMC and IPL from a number of previous neuroimaging studies of motor imitation, dorsal MPFC activation peaks from previous studies of MSA, and an MSA-related rostral MPFC peak described in a recent meta-analysis of Brodman area 10 (27). We also extracted activation from 4 other peaks not identified in our whole-brain parametric analysis, but of a priori theoretical interest. These peaks included regions of the anterior insula (AI) and anterior cingulate (ACC) from studies of SRs of affective states such as pain and disgust, a subregion in somatosensory cortex (SII) known to exhibit shared activation for observing and experiencing nonpainful touch, and a region of the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) implicated in some studies of MSA (16).

Data extracted from these regions of interest (ROIs) were consistent with the results of the whole-brain analysis: Activity in MPFC, IPL, and PMC tracked with EA, but activity in the ACC, AI, SII, and TPJ did not (Table S3). This similarity makes sense given the spatial similarity (<9-mm mean Euclidean distance) of the peaks identified in our whole-brain analysis and those extracted from previous studies (for spatial comparison, see Fig. 3 and Table S3). These findings provide converging support for the conclusion that brain regions involved in monitoring actions and motor intentions, as well as regions involved in MSA, support accurate judgments about social targets' affective states.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of right hemisphere mirror neuron system and MSA-related activation peaks from previous studies (in green) and accuracy-related activity in the current study (in yellow; for details, see Table S3). Left hemisphere points are not shown. dMPFC: dorsal MPFC; rMPFC: rostral MPFC.

Discussion

Previous neuroscience research on social cognition has identified neural systems thought to support SRs and MSA, but it has left unclear whether and how these systems contribute to accurate inferences about social targets. The current study addressed this gap in knowledge by using a technique adapted from social psychological research (21, 24) that was conceptually similar to the subsequent memory paradigm. This technique allowed us to search for neural activity specifically related to a measure of interpersonal understanding: EA, that is, the match between a perceiver's judgment of what a target was feeling and the report that target provided of what he/she was actually feeling. We found that accurate, as opposed to inaccurate, judgments of target affect relied on regions in premotor and inferior parietal cortex spatially similar to those found in studies of motor imitation, and medial prefrontal structures similar to those found in previous studies of MSA. These results provide evidence that parallel activation of components of the mirror neuron and MSA systems corresponds with the accuracy of perceivers' understanding of targets' affective states.

The current work has several implications for theories of social cognition. First, it provides evidence for the neural bases of accurate social judgments and, in the process, bridges 2 literatures that have heretofore proceeded independently. Until recently, lines of research related to the mirror neuron system and MSAs have had little connection and have sometimes engaged in a somewhat artificial debate about whether perceivers understand targets through the activation of SRs or through explicit attributions about mental states. It is likely, however, that both types of processing are involved in understanding target states, especially in naturalistic settings, where cues about a target's thoughts and feelings are multimodal, dynamic, and contextually embedded. Recent theories of social cognition recognize this likelihood and suggest that cortical areas related to MSA and mirror neuron system structures related to SRs should both be engaged when perceivers make inferences about target states (20, 28, 29). The current study adds to this emerging synthesis by demonstrating that brain activity related to both MSAs and SRs predicts the accuracy of social cognitive judgments.

It is possible that concurrent activity in these systems at the group level could obscure important individual differences in the neural bases of EA, wherein different perceivers may differ in the extent to which they rely on a particular system for making accurate inferences. For example, perceivers high in trait levels of emotional empathy may more heavily recruit shared sensorimotor representations (3) and may rely more on SRs during social cognitive tasks (30). To examine this possibility, we correlated mean activity in each type of system across participants and found that perceivers who engaged MSA-related regions to make accurate inferences also tended to engage SR-related regions (described in SI Text and Fig. S1). This finding suggests that, across individuals, concurrent activation of both systems supports accurate interpersonal judgment.

Second, the absence of accuracy-related activity in certain regions may suggest that accuracy for different kinds of internal states may depend on different neural systems. It was notable, for example, that neither the whole-brain parametric analyses nor the ROI-based analyses showed accuracy-related activity in the AI, ACC, or SII (see Table S3). Initially, this result may seem surprising, given that these regions have been implicated in the empathic sharing of affective and sensory states. The research supporting the role of these regions, however, has focused on the sharing of pain, disgust, touch, and posed emotional expressions (2, 3, 9, 11), all of which may depend on representations of somatovisceral states coded in these regions (31). The positive and negative affective states discussed by social targets in the current study were complex and naturalistic and, by and large, did not include direct or implied displays of pain or disgust. As such, inferences about such complex emotional cues may not depend on the AI, ACC, or SII. Future work should investigate the possibility that engagement of these regions predicts accuracy when perceivers judge target internal states with prominent somatovisceral components, such as pain and disgust (32), perhaps through communication between the ACC and AI and midline cortical regions related to MSA (33).

It was similarly notable that activity in the TPJ, which has been implicated in MSA, also was unrelated to accuracy when using both kinds of analyses in the current study. Again, the explanation may have to do with the specific kinds of mental states associated with activity in this region. The TPJ is engaged when assessing false beliefs (14), detecting deception (32), and more generally when shifting attention away from invalid cues (34). Judging the emotions experienced by targets in the current study likely did not involve such processes, although future work could use a variant of the present task to determine whether accurate detection of falsely conveyed emotions depends on TPJ activity. More generally, further investigation may be able to identify distinct regions whose activity predicts accuracy for different types of social cognitive judgments, which has been the case in subsequent memory research, for example, where the activity of different brain regions independently predicts successful encoding of social and nonsocial memories (35).

These possibilities highlight additional implications the present data may have for social cognition research. The neural bases of social cognition have until now been studied by using relatively simplified stimuli (i.e., pictures, vignettes, or cartoons) that rarely approximate the types of complex, dynamic, and contextually-embedded social cues encountered in the real world. These differences have practical implications for assessing the validity of social cognitive measures. For example, while theories suggest that social cognitive deficits underlie difficulties in social interaction experienced by people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), high-functioning individuals with ASD sometimes perform as well as control participants on simplified social cognitive tasks similar to those used in the extant imaging literature (36). Further, performance on simplified social cognitive tasks does not always track with the severity of social deficits in ASD (37, 38), and interventions teaching people with ASD to recognize emotions from simplified stimuli often improve performance on simplified tasks but not in real-world social interactions (39, 40). Using naturalistic social cognitive tasks and performance measures such as EA may help clarify the characteristics of social cognitive deficits in ASD and develop targeted interventions for improving social cognitive performance in that population (41).

Interpersonal understanding is likely subserved by several distinct and interacting networks of brain regions. Whereas simplified social cognitive paradigms may isolate individual networks, and therefore shed light on only 1 piece of a larger processing puzzle, naturalistic tasks like the one used here have the potential to show how multiple networks work simultaneously in supporting accurate social inferences. That being said, to further clarify the processing steps involved in this complex ability, and other social cognitive judgments more generally, future work should use both naturalistic and constrained social tasks in the same participants.

Unpacking sources of variability in empathy accuracy is another important direction for future research. These sources could include a perceiver's tendency to share a target's emotion, the amount and kind of emotion expressed by a target (25, 26), and whether a target's introspectively rated emotion matches the cues they express. In some cases, such as for alexithymic targets(42), experience and expression of emotion could fail to match because these targets have limited ability to introspectively rate their emotions. A perceiver could then correctly assess the cues the target expresses but appear to be empathically inaccurate because their ratings of the target's experience will not match the target's own ratings. Although such cases may be rare, this example highlights the consensus nature of the calculation of EA used here as the match between 2 subjective ratings of emotion (43). It also highlights a difference between the present study and prior work on the subsequent memory paradigm. Unlike consensus measures of social cognitive accuracy, subsequent memory tasks calculate accuracy as the match between participants' recognition responses and objective records of the memoranda they encoded.

That said, EA and subsequent memory paradigms share a broad conceptual similarity: both provide meaningful performance measures that can help constrain theory. In behavioral research, consensus measures of EA like the one used here already have proven to be powerful measures of social function: they can predict social functioning in typically developing individuals (44) and distinguish them from perceivers with psychological disorders characterized by social impairments, such as ASD (41). In future imaging research, methods like those used here may help to refine and test theories about the neural architecture underlying abilities such as accurate empathic judgment, which are critical to navigating the social world.

Methods

This study was carried out in 2 main phases. In the first, target phase, we collected stimulus videos in which social targets discussed autobiographical emotional events. In the second, perceiver phase, perceivers' brain activity was observed by fMRI while they watched target videotapes and rated the affect they believed targets were feeling at each moment. Each phase will be described separately here.

Target Phase.

In the first phase, 14 targets (7 female, mean age = 26.5) participated in exchange for monetary compensation. Following the standards of the Columbia University Institutional Review Board, all participants provided informed consent.

Emotion elicitation was conducted by using a protocol adapted from Levenson et al. (45). Targets were asked to recall and list the 4 most positive and 4 most negative autobiographical events they were willing to discuss in a lab setting. Targets then wrote a paragraph about each event, gave it a title (with a maximum length of 5 words), and rated each event for emotional valence and intensity by using a 9-point Likert scale. Events were only included in the subsequent procedure if they were rated as having an emotional intensity at or above the scale's midpoint. An experimenter pseudorandomized the order of events to be discussed by the target, such that no more than 2 positive or 2 negative events were discussed at a time. Targets were given the list of events to discuss and were seated in front of a camera, such that the frame captured them from the shoulders up, facing the camera directly. Targets were videotaped throughout the subsequent procedure; targets knew that they would watch the videos after discussing events, but did not know that these videos would also be seen by other subjects.

Targets were instructed to read each of the events on the list and spend about a minute evoking the sensory and affective experiences they had during that event, an elicitation strategy used both with healthy participants (45) and in clinical populations (46, 47). After they felt that they had successfully reinstated the affect they felt at the time of the event, targets described the memory, discussing both the details of the event and the emotions they experienced during that event. Some example events were the death of a parent, proposing marriage to a fiancé, and losing a job. Targets discussed these events for an average of 2 min, 15 s (maximum = 5:10, minimum = 1:15). After discussing each event, targets made summary judgments of the valence and intensity of the emotion they had experienced. Careful instruction assured that targets rated the affect they experienced while discussing the event and not during the event itself.

After targets discussed all 8 events, the experimenter prepared the videos for playback. Targets were instructed in the use of a sliding 9-point Likert scale, anchored at “very negative” on the left and “very positive” on the right, through which they could continuously rate the affective valence they had felt while rewatching their videos. Again, it was emphasized that targets should concentrate on the affect they had felt while discussing events and not during the events themselves. After subjects had completed their ratings, they were debriefed about the purpose of the study and asked for their consent to use their videos in the subsequent phase of the study.

Target Videos.

Two target participants refused to have their videos used in the subsequent EA paradigm, and a third showed insufficient variability in the ratings to allow meaningful ratings of EA; data from these 3 participants were excluded, leaving 11 targets in our sample (6 female, mean age = 25.4). From the remaining 88 stimulus videos (11 participants × 8 videos per participant), we selected 18 to match a series of criteria. Clips we selected for the subsequent EA paradigm had to be no longer than 3 min in length (mean = 2:05) and had been rated by targets to be affectively intense according to the summary judgments they made after discussing the event in that clip. Ratings for a given clip were required to have an absolute value >5, be above subjects' mean intensity rating (resulting mean intensity rating = 6.35 on a 9-point scale) to be included in the final stimulus set. Additionally, clips were selected such that they were divided equally between female and male targets and between positive and negative subject matter.

Perceiver Phase.

In the second phase of the study, 21 perceivers (11 female, mean age = 19.1) participated in exchange for monetary compensation and signed informed consent following the standards of the Columbia University Institutional Review Board. All perceivers were right-handed, were not taking any psychotropic medications, and did not report any Axis 1 psychiatric conditions.

During a prescan session, perceivers were trained in the EA task to be performed in the scanner. In each video trial, a cue word was presented for 5 s, followed by a fixation cross presented for 2 s, followed by the stimulus videos. Perceivers were instructed that if the cue “OTHER” appeared before a video, they would use 2 buttons to continuously rate how positive or negative they believed the target felt at each moment, using the same 9-point scale targets themselves had used (anchored at very negative on the left and very positive on the right). Similarly to targets, perceivers were carefully instructed to rate how they believed targets felt at each moment while talking about events, not how they had felt when the events they discussed on camera had occurred. Perceivers made such ratings of 6 videos. While watching the remaining 12 videos, perceivers performed 1 of 2 other tasks, in which they rated their own affect in response to target videos or rated the direction of targets' eye gaze; these conditions are not discussed here.

Videos were presented in the center of a black screen; a cue orienting perceivers toward their task (“how good or bad was this person feeling?”) was presented above the video, and a 9-point rating scale was presented below the video. At the beginning of each video, the number 5 was presented in bold. Whenever perceivers pressed the left arrow key, the bolded number shifted to the left (i.e., 5 became unbolded and 4 became bold). When perceivers pressed the right arrow key, the bolded number shifted to the right. In this way, perceivers could monitor their ratings in the scanner (see Fig. 1A).

Perceivers watched and rated 2 practice videos (not from the pool of videos presented in the scanner), and an experimenter interviewed them to verify that they understood each task. After this, perceivers were placed in the scanner and performed the main portion of the experiment. Videos were split across 3 functional runs, such that 2 other videos, along with videos viewed under the other conditions, were presented during each run.

Behavioral Analysis.

Data reduction and time-series correlations were performed by using Matlab 7.1 (Mathworks). Target and perceiver rating data were z-transformed across the entire session to correct for interindividual variation in use of the rating scale. Rating data were then separated by video and averaged for each 2-s period. Each 2-s mean served as 1 point in subsequent time-series analyses. Targets' affect ratings were then correlated with perceivers' affect ratings of targets; resulting coefficients are referred to as EA for that perceiver/clip combination (see Fig. 1B). All correlation coefficients were r- to Z-transformed in preparation for subsequent analyses.

To ensure that our correlational measure of accuracy was not confounded with the sheer number of ratings perceivers made, we correlated the number of affect ratings perceivers made per minute during a given video (mean = 9.83) with perceivers' accuracy for that video. This correlation was not significant (r = −0.10, P > 0.25). We also controlled for perceivers' number of ratings in our imaging analyses (see below).

Imaging Data Acquisition.

Images were acquired using a 1.5-Tesla GE Twin Speed MRI scanner equipped to acquire gradient-echo, echoplanar T2*-weighted images with blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast. Each volume comprised 26 axial slices of 4.5-mm thickness and a 3.5 × 3.5-mm in-plane resolution, aligned along theaxis connecting the anterior and posterior commisures. Volumes were acquired continuously every 2 s. Three functional runs were acquired from each subject. Because the video subjects viewed differed in length and were randomized across runs, the length of each run varied. Each run began with 5 “dummy” volumes, which were discarded from further analyses. At the end of the scanning session, a T1-weighted structural image was acquired for each subject.

Imaging Analysis.

Images were preprocessed and analyzed by using SPM2 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London) and custom code in Matlab 7.1 (Mathworks). All functional volumes from each run were realigned to the first volume of that run, spatially normalized to the standard MNI-152 template, and smoothed by using a Gaussian kernel with a FWHM of 6 mm. Mean intensity of all volumes from each run were centered at a mean value of 100, trimmed to remove volumes with intensity levels >3 SDs from the run mean, and detrended by removing the line of best fit. After this processing, all 3 runs were concatenated into 1 consecutive time series for the regression analysis. Data from 2 subjects were removed because of image artifacts induced by intensity spikes and signal dropout. Additionally, because the blocks in our study were unusually long, our data were especially sensitive to motion artifacts, and data from 3 subjects were removed because of large motion artifacts, leaving a total of 16 subjects (9 female) in our analysis.

Whole Brain Analyses.

After preprocessing, analyses were performed by using the general linear model. To search for neural activity corresponding to EA, regressors were constructed by using time-course correlation EA scores as parametric modulators determining the weight of each block. As such, the resulting statistical parametric maps reflect brain activity differences corresponding to the varying accuracy across blocks, within subjects. We also included a regressor of no interest corresponding to the amount of affect ratings perceivers had made per minute during each video; this allowed us to control for the possibility that an increased number of ratings, and not accuracy per se, would be driving brain activity during accurate blocks. Resulting activation maps were thresholded at P < 0.005, uncorrected, with an extent threshold of 20 contiguous voxels, corresponding to a false-positive discovery rate of <5% across the whole brain as estimated by Monte Carlo simulation implemented using AlphaSim in AFNI (48). Images were displayed by using the Computerized Anatomical Reconstruction and Editing Toolkit (CARET) (49) with activations within 8 mm of the surface projected onto the surface.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by Autism Speaks Grant 4787 (to J.Z.) and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant 1R01DA022541-01 (to K.O.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902666106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wicker B, et al. Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron. 2003;40:655–664. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer T, et al. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303:1157–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1093535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison I, Lloyd D, di Pellegrino G, Roberts N. Vicarious responses to pain in anterior cingulate cortex: Is empathy a multisensory issue? Cognit Affect Behav Neurosci. 2004;4:270–278. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogassi L, et al. Parietal lobe: From action organization to intention understanding. Science. 2005;308:662–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1106138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacoboni M, et al. Cortical mechanisms of human imitation. Science. 1999;286:2526–2528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzolatti G, Fogassi L, Gallese V. Neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the understanding and imitation of action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:661–670. doi: 10.1038/35090060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tkach D, Reimer J, Hatsopoulos NG. Congruent activity during action and action observation in motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13241–13250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2895-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr L, Iacoboni M, Dubeau MC, Mazziotta JC, Lenzi GL. Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: A relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5497–5502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935845100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery KJ, Haxby JV. Mirror neuron system differentially activated by facial expressions and social hand gestures: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cognit Neurosci. 2008;20:1866–1877. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keysers C, et al. A touching sight: SII/PV activation during the observation and experience of touch. Neuron. 2004;42:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakemore SJ, Bristow D, Bird G, Frith C, Ward J. Somatosensory activations during the observation of touch and a case of vision-touch synaesthesia. Brain. 2005;128:1571–1583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallese V, Keysers C, Rizzolatti G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cognit Sci. 2004;8:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singer T. The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: Review of literature and implications for future research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JP, Heatherton TF, Macrae CN. Distinct neural systems subserve person and object knowledge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15238–15243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232395699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxe R, Kanwisher N. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shamay-Tsoory SG, et al. The neural correlates of understanding the other's distress: A positron emission tomography investigation of accurate empathy. NeuroImage. 2005;27:468–472. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxe R. Against simulation: The argument from error. Trends Cognit Sci. 2005;9:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behav Cognit Neurosci Rev. 2004;3:71–100. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsson A, Ochsner KN. The role of social cognition in emotion. Trends Cognit Sci. 2008;12:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ickes W, Stinson L, Bissonnette V, Garcia S. Naturalistic social cognition: Empathic accuracy in mixed-sex dyads. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1990;59:730–742. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD. Making memories: Brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science. 1998;281:1185–1187. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner AD, et al. Building memories: Remembering and forgetting of verbal experiences as predicted by brain activity. Science. 1998;281:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levenson RW, Ruef AM. Empathy: A physiological substrate. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1992;63:234–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner K. It takes two: The interpersonal nature of empathic accuracy. Psychol Sci. 2008;19:399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner K. Unpacking the informational bases of empathic accuracy. Emotion. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0016551. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert SJ, et al. Functional specialization within rostral prefrontal cortex (area 10): A meta-analysis. J Cognit Neurosci. 2006;18:932–948. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uddin LQ, Iacoboni M, Lange C, Keenan JP. The self and social cognition: The role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons. Trends Cognit Sci. 2007;11:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keysers C, Gazzola V. Towarda unifying neural theory of social cognition. Prog Brain Res. 2006;156:379–401. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gazzola V, Aziz-Zadeh L, Keysers C. Empathy and the somatotopic auditory mirror system in humans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1824–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saarela MV, et al. The compassionate brain: Humans detect intensity of pain from another's face. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:230–237. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaki J, Ochsner KN, Hanelin J, Wager T, Mackey SC. Different circuits for different pain: Patterns of functional connectivity reveal distinct networks for processing pain in self and others. Soc Neurosci. 2007;2:276–291. doi: 10.1080/17470910701401973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell JP. Activity in right temporo-parietal junction is not selective for theory of mind. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:262–271. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macrae CN, Moran JM, Heatherton TF, Banfield JF, Kelley WM. Medial prefrontal activity predicts memory for self. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:647–654. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castelli F. Understanding emotions from standardized facial expressions in autism and normal development. Autism. 2005;9:428–449. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fombonne E, Siddons F, Achard S, Frith U, Happe F. Adaptive behavior and theory of mind in autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;3:176–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02720324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tager-Flusberg H. Evaluating the theory-of-mind hypothesis in autism. Curr Directions Psychol Sci. 2007;16:311–315. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Golan O, Baron-Cohen S. Systemizing empathy: Teaching adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism to recognize complex emotions using interactive multimedia. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:591–617. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadwin J, Baron-Cohen S, Howlin P, Hill K. Does teaching theory of mind have an effect on the ability to develop conversation in children with autism? J Autism Dev Disord. 1997;27:519–537. doi: 10.1023/a:1025826009731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roeyers H, Buysse A, Ponnet K, Pichal B. Advancing advanced mind-reading tests: Empathic accuracy in adults with a pervasive developmental disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sifneos PE. Alexithymia: Past and present. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(Suppl):137–142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Funder DC. On the accuracy of personality judgment: A realistic approach. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:652–670. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gleason K, Jensen-Campbell L, Ickes W. The role of empathic accuracy in adolescents' peer relations and adjustment. Personality Soc Psychol Bull. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0146167209336605. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levenson RW, Carstensen LL, Friesen WV, Ekman P. Emotion, physiology, and expression in old age. Psychol Aging. 1991;6:28–35. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantani T, Okamoto Y, Shirao N, Okada G, Yamawaki S. Reduced activation of posterior cingulate cortex during imagery in subjects with high degrees of alexithymia: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pitman RK, Orr SP, Steketee GS. Psychophysiological investigations of posttraumatic stress disorder imagery. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1989;25:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox RW. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Essen DC, et al. An integrated software system for surface-based analysis of cerebral cortex. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8:443–459. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2001.0080443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.