Abstract

Mutations within the protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHP2, which is encoded by PTPN11, cause a significant proportion of Noonan syndrome (NS) cases, typically presenting with both cardiac disease and craniofacial abnormalities. Neural crest cells (NCCs) participate in both heart and skull formation, but the role of SHP2 signaling in NCC has not yet been determined. To gain insight into the role of SHP2 in NCC function, we ablated PTPN11 specifically in premigratory NCCs. SHP2-deficient NCCs initially exhibited normal migratory and proliferative patterns, but in the developing heart failed to migrate into the developing outflow tract. The embryos displayed persistent truncus arteriosus and abnormalities of the great vessels. The craniofacial deficits were even more pronounced, with large portions of the face and cranium affected, including the mandible and frontal and nasal bones. The data show that SHP2 activity in the NCC is essential for normal migration and differentiation into the diverse lineages found in the heart and skull and demonstrate the importance of NCC-based normal SHP2 activity in both heart and skull development, providing insight into the syndromic presentation characteristic of NS.

Approximately 4% of human infants are born with a congenital malformation. Abnormal heart formation, the most common human birth defect, afflicts nearly 1% of newborns (1). Numerous clinical syndromes result from mutations that affect regulation of the ERK1/2 cascade (2), including Noonan (PTPN11, K-RAS, C-RAF, SOS1), LEOPARD (PTPN11, NF1, C-RAF), Costello (H-RAS), and cardio-facio-cutaneous (B-RAF, K-RAS, MEK1, MEK2) syndromes (3). Affected patients present with several overlapping phenotypes in the brain, heart, face, and skin; thus, these syndromes are termed neurocardiofacial cutaneous (NCFC) syndromes (4). Mutations associated with these syndromes often result in gain of function with respect to signaling through ERK1/2, with the exception of certain LEOPARD syndrome (LS) mutations in PTPN11 associated with loss of function (5, 6).

PTPN11, located on human chromosome 12q24.1, encodes the ubiquitously expressed protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP2. SHP2 is essential for early vertebrate development and can regulate cell migration, proliferation, survival, and differentiation through pathways, including the MAPK, ERK1/2 branch (7). Mice homozygous for a null mutation in PTPN11 die at implantation due to failure in the development of the extraembryonic trophoectodermal lineage, whereas induction of a dominant-negative SHP2 in Xenopus blocks mesoderm formation by impairing ERK signaling, leading to arrest of gastrulation (8, 9).

Neural crest cells (NCCs), often referred to as the fourth germ layer, are a multipotent cell population originating after gastrulation. NCCs are first localized in the neural folds at the dorsal aspect of the developing spinal cord and delaminate from the neural tube. They then migrate via different pathways toward the organ primordia, where they give rise to and influence the development of a diverse array of tissues, including numerous craniofacial structures, the cardiac outflow tract (OFT), the endocrine glands, and neurons (10). Therefore, some of the defects observed in NCFC syndromes may arise principally from perturbation of NCC determination, proliferation, migration, or differentiation. These NCC processes are regulated by various molecular signals and pathways, including those dependent on sonic hedgehog, the Wingless/INT-related families (Wnts), and bone morphogenic proteins and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) (11). To the best of our knowledge, however, the role of SHP2 in NCC function has not yet been elucidated. In the present work, we used Cre-mediated excision of PTPN11 in premigratory NCCs to explore the role of SHP2 in this cell population as it participates in the development of the heart and head fields. The data demonstrate that loss of SHP2 function in the premigratory neural crest can lead directly to heart and facial defects, and that this lost function can be largely rescued through the restoration of normal ERK1/2 signaling. These data provide a mechanistic basis for understanding the syndromic presentations that can occur in such diseases as Noonan syndrome and DiGeorge syndrome as a result of altered signaling in the neural crest.

Results

Generation of Mice Containing a Conditional Null Mutation of SHP2.

SHP2 contains 2 src homology (SH2) domains and a protein tyrosine phosphatase domain (PTP), with the amino terminus-SH2 domain functioning as a molecular switch to regulate SHP2's catalytic activity (12). To conditionally inactivate the N-SH2 domain and the hinge region linking the 2 SH2 domains, a mutant allele was created by introducing 2 loxP sites into introns outside exon 3 and 4 [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A and B]. Genotyping of the homozygous SHP2 floxed mice (SHP2loxP/loxP) via PCR showed the expected fragment of 320 bases corresponding to the floxed allele (Fig. S1C). Before excision of the sequences flanked by the loxP sequence, these mice were viable, fertile, and generally indistinguishable from control littermates, demonstrating that the conditional gene-targeting strategy did not disrupt normal SHP2 expression. To determine the function of SHP2 in NCCs, SHP2 conditional mutants (SHP2loxP/wt) were interbred to transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the transcriptional control of the NCC-restricted Wnt1 promoter. The Wnt1 promoter is transcriptionally active only in the premigratory NCCs residing in the dorsal neural tube, and Wnt1 expression is extinguished as NCCs migrate away from the neural tube, with the promoter remaining silent thereafter (13). Heterozygous SHP2 knockout mice (Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3−4/wt) were completely normal and indistinguishable from control littermates. Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt offspring were then interbred with SHP2loxP/loxP mice to generate homozygous SHP2 knockout mice (Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4) and control littermates. To determine the efficiency of Cre-mediated excision of PTPN11 in NCCs, SHP2 expression was assessed using E9.5 pharyngeal arch samples with abundant NCCs. On immunostaining, SHP2 was ubiquitously expressed in the pharyngeal arches of the control embryos (Fig. S1D), as expected. These mice were subsequently bred into our CAG-CAT EGFP background, to fate map the NCCs (13); as expected, the EGFP-labeled NCCs showed reduced SHP2 expression in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt and Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. S1D). Quantitation by Western blot analysis revealed SHP2 reductions of 50% in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt embryos and 90% in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. S1E), with the residual 10% of SHP2 in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos due to its expression in pharyngeal ectoderm and endoderm (Fig. S1D).

Both the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt and Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos survived in the anticipated Mendelian ratios until mid-gestation; however, the survival rate for Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos dropped after E15.5, and no pups were born alive (Table S1). By E15.5, the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos invariably were significantly smaller and displayed a characteristic spectrum of cardiac and craniofacial defects, defined below.

NCC-SHP2 Null Embryos Exhibit Severe Craniofacial Anomalies and Heart Defects.

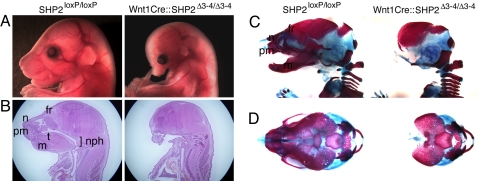

Patients suffering from NS often display visible craniofacial phenotypes, including positional anomalies of the eyes and ears; a short, webbed neck; smaller-than-normal jaw; altered canthal distances; down-slanting palpebral fissures; depressed nasal root; wide-based nose with a bulbous nasal tip; pointed chin; and a large cranium with a small face. Cranial NCCs contribute significantly to the formation of mesenchymal structures in the head and neck by differentiating into many cell types, including neurons, glia, cartilage, bone, and connective tissue (14). Compared with controls, the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos had a smaller head, nose, jaw, and ear, as well as eye placement anomalies (Fig. 1A). Histological examination of the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos revealed defects in the nasopharynx, tongue, mandible, and nasal capsule and bone (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Craniofacial phenotypes of Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos at E17.5. (A) Lateral view of the face from the control and Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos. (B) Sagittal section of the head and neck (H&E staining). (C and D) Alcian blue and alizarin red staining of the skull. (C) Lateral view. (D) Upper view. t, tongue; nph, nasopharynx; fr, frontal bone of the skull; n, nasal bone; pm, premaxillary bone; m, mandible.

The 3-dimensional architecture of the skeleton was examined using modified whole-mount alcian blue–alizarin red S staining (15). NCC-derived craniofacial bones and nasal cartilage and mandible (except for the interparietal bones) were dramatically ablated or completely absent in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. 1 C and D). The data demonstrate that NCC-autonomous SHP2 expression is necessary for normal craniofacial formation and underscore the importance of normal SHP2 activity in the migratory NCCs participating in craniofacial development.

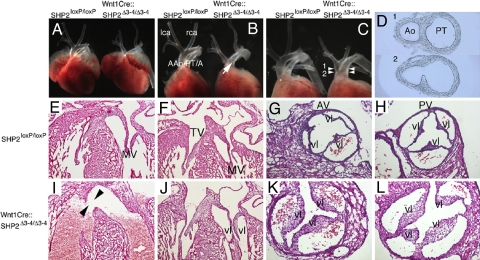

Cardiac NCCs, a subpopulation of the cranial NCCs, originate from the lower hindbrain between the otic placode and fourth somite. The cells contribute to the remodeling of arch arteries, septation of the OFT, closure of the ventricular septum, and innervation of the cardiac ganglia (16–18). Because cardiovascular and craniofacial defects often occur concomitantly in NS, the cardiovascular phenotypes in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt and Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos were analyzed (Fig. 2 and Table S2). In the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/wt embryos, craniofacial and cardiovascular phenotypes were completely normal, suggesting that a single allele of SHP2 is sufficient to allow NCCs to function in normal craniofacial and cardiovascular formation. In the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos, the gross anatomy of the atria and ventricles was normal (Fig. 2A); strikingly, however, all of the hearts exhibited persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA). Based on van Praagh's PTA classification (19), 84.2% of the hearts had type II PTA (Fig. 2B) and 15.8% had type I PTA (Fig. 2 C and D). Abnormal anatomy of the arch arteries was observed in 31.6% of the hearts. The Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos demonstrated normal architecture of the atrial and ventricular walls, but invariably exhibited ventricular septal defects (Fig. 2 E and I). Atrioventricular valves were intact in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. 2 F and J). Further detailed analyses of the PTA pathology in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos were performed. Normally, the aortic and pulmonary valves consist of 3 leaflets (Fig. 2 G and H); here, however, 90.0% of the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 truncal valves contained 3 leaflets, and 10% (n = 10) had 4 leaflets (Fig. 2 K and L). Longitudinal views showed significant elongation and thickening of the truncal valves of the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos compared with the aortic valves in control littermates. The data indicate that NCC mutations can result in a spectrum of defects associated with the diverse roles of this progenitor population in multiple organ and system development, and underscore the importance of NCC SHP2 expression in the normal development of both cardiovascular and craniofacial anatomy.

Fig. 2.

Cardiovascular pathology in PTPN11 knockout mice. (A and B) Type II PTA in Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 hearts. Frontal views of a control (SHP2loxP/loxP; Left) versus a Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 heart at E17.5. (Magnification: ×2.5.) Note that both atria were removed in (B). lca, left carotid artery; rca, right carotid artery; Aao, ascending aorta; PT/A, pulmonary trunk/artery. The arrow in (B) indicates the continued aorta/pulmonary artery present in the truncus arteriosus. (C and D) Type I PTA of Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 hearts at E17.5. (C) Frontal view, with both atria removed. (Magnification: ×2.5.) (D) Transverse sections of the OFT in a Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryo. The cutting levels are shown in (C); the section, in (D). Ao, aorta; PT, pulmonary trunk. (E–L) H&E staining of E17.5 hearts. (E and I) Longitudinal sections of the hearts. (Magnification: ×10.) The arrowheads in (I) indicate a ventricular septal defect. (F and J) Longitudinal section of the atrioventricular valves. (Magnification: ×10.) MV, mitral valve; TV, tricuspid valve. (G, H, K, and L) Transverse sections of the OFT valves. (Magnification: ×20.) (G) and (H) show the aortic and pulmonary valves (AV and PV), respectively. Vl, valve leaflet

SHP2-Deficient NCCs Exhibit Altered Migration and Differentiation.

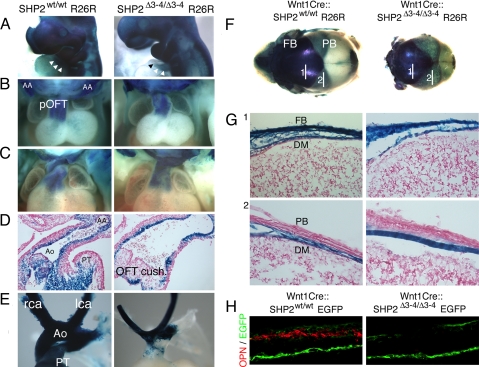

SHP2 can regulate cell migration, proliferation, survival, and differentiation (20). NCCs can differentiate into a broad range of cell types once they reach their final destination. Here NCC lineage was followed through breeding of our mice into either the ROSA26 or EGFP indicator background. In normal mouse development, NCCs begin to migrate after E8.5 and reach target organ primordia by E10. At E10, the SHP2-deficient NCCs appeared to be normally distributed in the craniofacial region, pharyngeal arches, and distal truncus compared with controls (Fig. 3A), indicating that their initial proliferation and migration patterns were unaffected. A subpopulation of cardiac NCCs continues to migrate and colonizes the proximal OFT and endocardial cushions, where aorticopulmonary septation occurs. At E11.5, NCCs of the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos still demonstrated normal migration to the proximal OFT (Fig. 3B); however, at E12.5, although the NCCs were still abundantly distributed (Fig. 3C), sectioned material revealed significantly reduced numbers of NCCs in the OFT cushions of the homozygous knockout hearts (Fig. 3D), culminating in the failure of proper OFT septation. In the later embryonic stages, cardiac NCCs populate the tunica media of the aortic arch arteries and, together with endothelial cells and endoderm, contribute to the remodeling that results in the adult left-sided aortic arch vascular pattern (21). In E17.5 Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 hearts, NCCs appeared to be normally distributed in the carotid and right brachiocephalic artery and distal OFT, but were substantially decreased in the proximal OFT (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

NCC fate-mapping analyses. Controls and homozygous nulls were crossed into the ROSA26 background to allow tracing of NCC lineages by β-galactosidase staining. (A) β-galactosidase–stained embryos at E10. (Magnification: ×4.) Arrowheads indicate the cells in the conotruncal regions. (B) Anterior view of E11.5 hearts. (Magnification: ×5.) AA, aortic arch; pOFT, proximal outflow tract. (C) Anterior view of E12.5 hearts. (Magnification: ×5.) (D) Longitudinal section of the OFT at E12.5. (Magnification: ×20.) Ao, aorta; PT, pulmonary trunk. (E) OFT and arch arteries. (Magnification: ×6.) Rca, right carotid artery; lca, left carotid artery; Ao, aorta; PT, pulmonary trunk. (F) β-galactosidase staining of an E17.5 skull showing the contribution of NCC-derived cell lineages. FB, frontal bone; PB, parietal bone. (G) Sagittal section of the frontal and parietal bones. The numbers refer to the section sites shown in (A). DM, dura mater, FB, frontal bone, PB; parietal bone. (H) Osteopontin (OPN) immunostaining of the frontal bone.

Cranial NCCs in Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos appeared to migrate normally to the developing face at E10 and were retained in the frontal bone and dura mater areas at E17.5 (Fig. 3 F and G). Because the frontal bone structures are defective in the Wnt1Cre ::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. 1 D and E), we explored whether cranial NCC differentiation into osteoblasts was altered. The osteoblast marker osteopontin was abundantly expressed in the control frontal bone, whereas no osteopontin expression was observed in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos (Fig. 3H), confirming the failure of normal differentiation of SHP2 null NCCs. Immunofluorescent staining was performed using Ki-67 for cell proliferation and active caspase 3 for analysis of apoptosis. In sections from E9.5 pharyngeal arches and E12.5 OFT, both Ki-67 and active caspase 3 staining were identical in Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos and controls, and this was maintained up to E12.5 (Fig. S2).

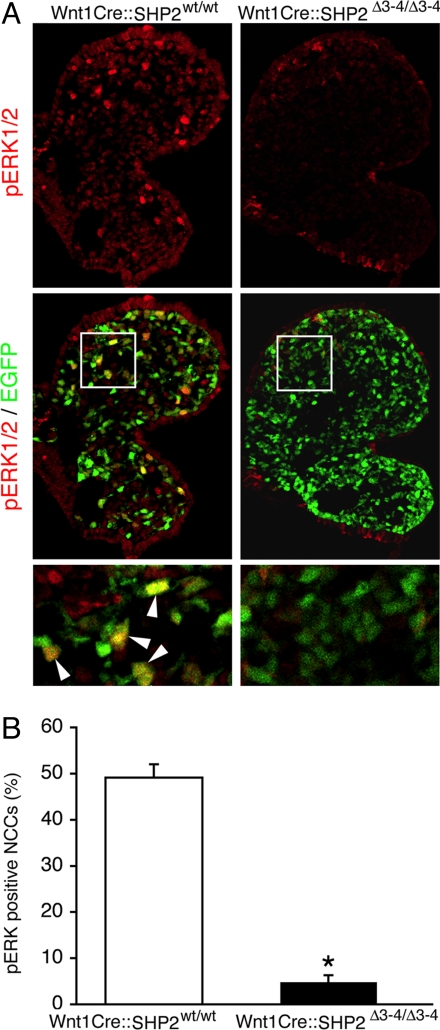

PTPN11 Ablation in NCCs Selectively Down-Regulates the ERK1/2 Pathway.

SHP2 can modulate the MAPK cascades (20), and we examined SHP2's several candidate downstream pathways in the modified NCCs. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was severely affected in the SHP2-deficient NCCs (Fig. 4 A and B), but the activity of other potentially affected signaling pathways, including the RhoA and JAK/STAT branches, remained unchanged (Fig. S3). Because inactivation of TGF-β signaling in NCCs can cause deficits similar to those noted earlier (22), we explored whether SHP2 knockdown had an effect on TGF-β signaling. TGF-β activity, as assessed by phospho-Smad2/3 immunostaining, also was unchanged in the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos compared with controls (Fig. S3). These results indicate that the ERK1/2 branch of the MAPK pathway is selectively affected in the SHP2-deficient NCCs.

Fig. 4.

ERK1/2 phosphorylation is decreased in Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 NCCs. (A) phospho-ERK1/2 immunostaining of the E9.5 pharyngeal arch. The bottom panel corresponds to a magnified portion of the bounded areas in the panels immediately above; arrowheads identify NCCs containing activated phosphorylated ERK1/2. (B) Quantification of phospho-ERK1/2–positive NCCs. At least 5,000 NCCs were analyzed from 5 embryos. *P < .0001.

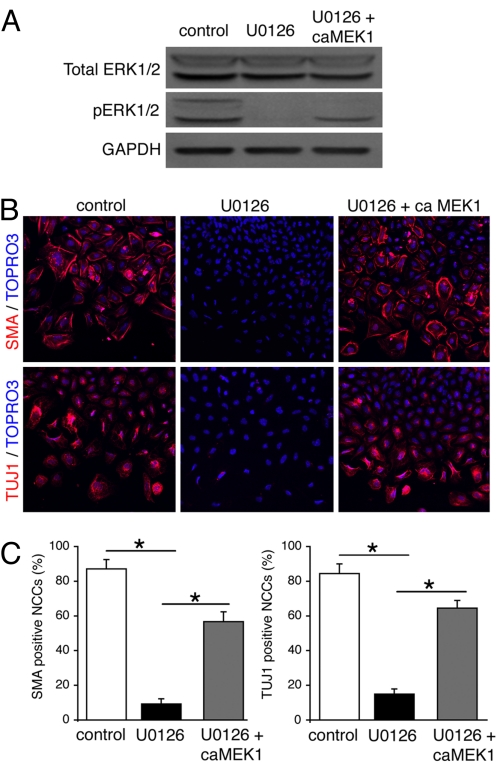

In normal mouse embryogenesis, ERK1/2 is transiently (until ≈E10.5) activated in some tissue primordium, including the neural crest, peripheral nervous system, blood vessels, and heart (23). The significance of ERK1/2 activation during early development remains obscure, however. Because ERK1/2 was selectively down-regulated in SHP2-deficient NCCs, and these cells failed to differentiate into osteoblasts, we tested the hypothesis that ERK1/2 activation is necessary for NCC differentiation using neural tube explant assays. Neural tubes from the cardiac neural crest region were isolated from E8.5 embryos and grown in culture. To inactivate ERK1/2, the MEK inhibitor U0126 was added for the first 48 h (Fig. 5A), after which the culture medium was changed and the NCCs were incubated for another 48 h. DMSO-treated control cardiac NCCs robustly differentiated into neurons and smooth muscle cells, as determined by immunofluorescent staining for TUJ1 and SMA, respectively (Fig. 5B). In contrast, U0126-treated NCCs showed a dramatic reduction in the number of TUJ1- and SMA-positive cells (Fig. 5 B and C), underscoring the importance of ERK1/2 activation in these differentiation processes.

Fig. 5.

Transient ERK1/2 activation of cardiac NCCs restores their ability to express neural and smooth muscle markers. (A) Activated ERK1/2 levels in neural tube cultures. (B) SMA (Top) and TUJ1 (Bottom) immunostaining of cardiac NCCs. (Magnification: ×20.) ca, constitutively active. (C) Quantification of SMA- and TUJ1-positive NCCs. At least 3,000 NCCs were analyzed in each group. *P < .0001.

We next determined whether ERK1/2 activation was sufficient to promote cell differentiation in the cultures. To reactivate ERK1/2, adenovirus carrying constitutive active (ca)MEK1 was used to infect the U0126-treated cultures for the first 48 h, after which the cells were switched to normal culture medium and incubated for an additional 48 h. Increased levels of phospho-ERK1/2 (Fig. 5A) were accompanied by increases in SMA- and TUJ1-positive NCCs (Fig. 5 B and C), suggesting that transient ERK1/2 activation in NCCs is necessary for the differentiation of NCCs into diverse cell lineages during embryogenesis.

Discussion

ERK1/2 is transiently activated during early embryogenesis (23), and ERK2 is critical for normal neural crest development (24). We and others have previously shown that mutations in SHP2 associated with NS affect ERK1/2 signaling (25), and thus we thought it logical to explore the NCC-autonomous consequences of SHP2 deficiency, particularly as it pertains to ERK1/2 activation and the resultant effects on NCC migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Our data show that SHP2 deficiency in NCCs leads to decreased ERK1/2 activation, resulting in a failure of cell differentiation at diverse sites in the developing embryo with anatomical and functional deficits so severe as to preclude viability of the developing fetus.

We chose to study NCCs because of their migratory patterns and ability to give rise to many different cell types, reasoning that altered SHP2 activity in a single precursor population, such as NCCs, might be responsible for some of the pathologies presenting at diverse sites in NS. Complete ablation of SHP2 expression did result in decreased ERK1/2 activation in the premigratory NCCs and, strikingly, influenced the development of both cardiac and cranial structures, 2 systems frequently affected in NS (26).

The phenotype resembles other syndromic presentations. The 22q11 deletion syndrome is the most common microdeletion syndrome in humans, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 4,000 live births. This syndrome comprises DiGeorge syndrome, velocraniofacial syndrome, and conotruncal anomaly face syndrome; ≈90% of the patients share hemizygous deletions of proximal chromosome 22q11.2, most often encompassing a 3-Mb region that includes ≈30 genes (27). The patients exhibit craniofacial anomalies, thymus and parathyroid gland aplasia/hypoplasia, and cardiac OFT defects, thought to arise principally from perturbed NCC development (28). In a mouse model, homozygous inactivation of Tbx1 results in a highly consistent 22q11 deletion syndrome, and deletion of a single copy of Tbx1 results in a partially penetrant 22q11 deletion syndrome phenotype (29). Inactivation of the V-crk sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog (avian)-like gene, (Crkl), whose protein product activates the RAS and JUN kinase-signaling pathways, also results in a 22q11 deletion syndrome–like phenotype (30). The Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 mice in the present study exhibited defects consistent with those found in many patients suffering from 22q11 deletion syndrome. Based on our data, we speculate that some facets of the syndrome may arise from deficits in the NCCs.

Many of these diverse syndromes are linked by the common theme of aberrant ERK signaling as a result of alterations in upstream effectors. For example, FGF8 encodes a polypeptide with many important functions during mammalian development. By binding to its cognate receptor, FGF stimulates the ERK1/2 cascade by promoting the association of the adaptor protein SHP2 with small G proteins that are activators of Ras (31). Ras activation can lead to increased ERK1/2 signaling. Although FGF8 is not located on 22q11, FGF8 interacts with multiple proteins with genes located in or proximal to 22q11. FGF signaling has been proposed to mediate TBX1's role in pharyngeal development (32). Similarly, CRKL and FGF8 interact such that CRKL can regulate the expression of certain FGF8 target genes in the pharyngeal arches. Intriguingly, CRKL deficiency disrupts ERK1/2 activation (33). As is the case for the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos, mice with reduced or eliminated FGF8 expression exhibit reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These animals have craniofacial and cardiovascular defects similar to those noted in TBX1- and CRKL-mutant mice, respectively (34, 35).

Recent genetic data directly implicate altered ERK activity with the clinical presentation of these syndromes. ERK2 is positioned distal to and outside the 3-Mb region of 22q11, and recent data obtained from patients with a small (≈1 Mb) distal 22q11.2 microdeletion showed an association between haploinsufficiency for MAPK1/ERK2 and neural crest deficits. These patients exhibited some of the classic defects of the 22q11 deletion syndrome spectrum, including craniofacial and conotruncal cardiac anomalies (24), and the authors went on to show that NCC-specific deletion of ERK2 or NCC-specific inactivation of upstream components of the pathway, MEK1/MEK2 and B-Raf/C-Raf, also led to similar cardiac and craniofacial defects. In the present study, the SHP2-null selectively inactivated the ERK1/2 pathway, and the phenotypes of the Wnt1Cre::SHP2Δ3–4/Δ3–4 embryos were mostly consistent with those of both RAF/MEK/ERK-inactivated mice and TBX1-, CRKL-, and FGF8-mutant mice. These findings suggest that many aspects of the pathogenesis of the 22q11 deletion syndrome may be related to perturbation of a common genetic pathway necessary for the activation or correct level of ERK1/2 signaling. Even with the limited data currently available, it is apparent that the RAS/MAPK syndromes can arise as a result of multiple mutations in different genes that encode both proximal and distal players, and that multiple syndromes (e.g., Noonan, Costello) can arise through different mutations in the same or different genes (3).

LS is an autosomal dominant disorder; the acronymic name “LEOPARD” refers to its major features of lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonic stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth, and sensorineural deafness. SHP2 mutations in LS are clustered in the PTP domain and lead to decreased SHP2 activity. LS alleles exhibit substantial ERK1/2 activation in vitro (5, 36), consistent with our observations in the SHP2-ablated NCCs. We first hypothesized that a SHP2 null in NCCs might mimic some aspects of LS; unexpectedly, however, the mice more closely phenocopied the 22q11 deletion syndrome. A potential explanation for this discrepancy is that the complete absence of SHP2 may have different consequences than the expression of a LS-causing dominant-negative mutant; for example, the mutant protein expressed may still interact with a set or subset of adaptor/scaffolding proteins, altering critical protein–protein interactions. A possible alternative explanation is that differences in the magnitude of ERK1/2 reduction might lead to distinct craniofacial and cardiovascular phenotypes. Acting synergistically, the ERK1 and ERK2 knockouts in NCCs exacerbate craniofacial defects (24). Resolution of these discrepancies will require creating a knockin LS mutant mouse and analyzing the resulting development of the craniofacial and cardiovascular systems.

Animal models developed to study the RAS/MAPK syndromes include mouse models with systemic knockouts of SHP2 (37), as well as knockin models carrying SHP2 mutations found in humans (38). Recently, both activating and inactivating SHP2 mutations have been studied in zebrafish (39). Morpholino-mediated SHP2 knockdown resulted in early defects in gastrulation, precluding detailed studies of organogenesis; nonetheless, it was apparent that loss of function led to defective cellular movement. Similarly, expression of either LS or NS mutants also resulted in defects in cell convergence and extension, and the embryos also displayed both craniofacial and cardiovascular defects (39). Our data confirm that SHP2 levels are functionally important in the NCCs, modulating ERK1/2 activity and affecting development of the OFT and frontal skull structures. NCC-autonomous SHP2 activity is critical for normal development in both the heart and skull, and there appears to be a relatively narrow window of activity that is conducive to normal development, with too little or too much SHP2 activity leading to aberrant development. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that alterations in the NCCs as a result of altered SHP2 activity play a major role in the pathogenic presentation of various syndromic diseases. A detailed exploration of the exact alterations in migration, proliferation, and differentiation underlying the pathogenesis in the various organ systems would be valuable.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mice.

Animal use was in accordance with institutional guidelines, and all experiments were reviewed and approved by the institutional Animal Care Committee. All lines of transgenic and gene-targeted mice were made in or backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background for at least 15 generations before being used in the crosses analyzed. The following sequences were used for genotyping: Wnt1Cre, sense 5′-ATTCTCCCACCGTCAGTACG-3′, antisense 5′-CGTTTTCTGAGCATACCTGGA-3′; SHP2 knockout, sense 5′-CTGGAAGAGCAGTCAGTCA GTGCT-3′, antisense 5′-CCACTCACCTTGTCATGTAGTAACTC-3′; ROSA26R, sense 5′-TGGGGAATGAATCAGGCCACGG-3′, antisense 5′-GCGTGGGCGTATTCGCCAAGGA-3′; EGFP, sense 5′-ACGTAAACGGCCACAAGT TCA-3′, antisense 5′-GCTGTT GTAGTTGTACTCCAGGT-3′. Additional methods are detailed in the SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01HL69799, P50HL07701, P01HL059408, and R01HL087862 (to J.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902230106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics, 2008 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schubbert S, Bollag G, Shannon K. Deregulated Ras signaling in developmental disorders: New tricks for an old dog. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki Y, et al. The RAS/MAPK syndromes: Novel roles of the RAS pathway in human genetic disorders. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:992–1006. doi: 10.1002/humu.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentires-Alj M, Kontaridis MI, Neel BG. Stops along the RAS pathway in human genetic disease. Nat Med. 2006;12:283–285. doi: 10.1038/nm0306-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontaridis MI, et al. PTPN11 (Shp2) mutations in LEOPARD syndrome have dominant negative, not activating, effects. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6785–6792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tartaglia M, et al. Gain-of-function SOS1 mutations cause a distinctive form of Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:75–79. doi: 10.1038/ng1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kontaridis MI, et al. Deletion of Ptpn11 (Shp2) in cardiomyocytes causes dilated cardiomyopathy via effects on the extracellular signal–regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase– and RhoA-signaling pathways. Circulation. 2008;117:1423–1435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang TL, et al. The SH2-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase SH-PTP2 is required upstream of MAP kinase for early Xenopus development. Cell. 1995;80:473–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang W, et al. An Shp2/SFK/Ras/Erk signaling pathway controls trophoblast stem cell survival. Dev Cell. 2006;10:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delfino-Machin M, Chipperfield TR, Rodrigues FS, Kelsh RN. The proliferating field of neural crest stem cells. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3242–3254. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trainor PA. Specification of neural crest cell formation and migration in mouse embryos. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hof P, et al. Crystal structure of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Cell. 1998;92:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura T, Colbert MC, Robbins J. Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res. 2006;98:1547–1554. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai Y, Maxson RE., Jr. Recent advances in craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2353–2375. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito Y, et al. Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects. Development. 2003;130:5269–5280. doi: 10.1242/dev.00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutson MR, Kirby ML. Neural crest and cardiovascular development: A 20-year perspective. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:2–13. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby ML, Stewart DE. Neural crest origin of cardiac ganglion cells in the chick embryo: Identification and extirpation. Dev Biol. 1983;97:433–443. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snider P, Olaopa M, Firulli AB, Conway SJ. Cardiovascular development and the colonizing cardiac neural crest lineage. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:1090–1113. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Praagh R, Van Praagh S. The anatomy of common aorticopulmonary trunk (truncus arteriosus communis) and its embryologic implications: A study of 57 necropsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1965;16:406–425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(65)90732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The “Shp”ing news: SH2 domain–containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeDourin NM, Kalcheim G. The Neural Crest. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wurdak H, et al. Inactivation of TGFbeta signaling in neural crest stem cells leads to multiple defects reminiscent of DiGeorge syndrome. Genes Dev. 2005;19:530–535. doi: 10.1101/gad.317405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newbern J, et al. Mouse and human phenotypes indicate a critical conserved role for ERK2 signaling in neural crest development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17115–17120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805239105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura T, et al. Mediating ERK 1/2 signaling rescues congenital heart defects in a mouse model of Noonan syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2123–2132. doi: 10.1172/JCI30756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allanson JE. Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C:274–279. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shprintzen RJ. Velo-cardio-facial syndrome: 30 years of study. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14:3–10. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schinke M, Izumo S. Getting to the heart of DiGeorge syndrome. Nat Med. 1999;5:1120–1121. doi: 10.1038/13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE. DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat Genet. 2001;27:286–291. doi: 10.1038/85845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guris DL, et al. Mice lacking the homologue of the human 22q11.2 gene CRKL phenocopy neurocristopathies of DiGeorge syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:293–298. doi: 10.1038/85855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottcher RT, Niehrs C. Fibroblast growth factor signaling during early vertebrate development. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:63–77. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitelli F, et al. A genetic link between Tbx1 and fibroblast growth factor signaling. Development. 2002;129:4605–4611. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon AM, et al. Crkl deficiency disrupts FGF8 signaling in a mouse model of 22q11 deletion syndromes. Dev Cell. 2006;10:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abu-Issa R, et al. FGF8 is required for pharyngeal arch and cardiovascular development in the mouse. Development. 2002;129:4613–4625. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park EJ, et al. Required, tissue-specific roles for FGF8 in outflow tract formation and remodeling. Development. 2006;133:2419–2433. doi: 10.1242/dev.02367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tartaglia M, et al. Diversity and functional consequences of germline and somatic PTPN11 mutations in human disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:279–290. doi: 10.1086/499925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen B, et al. Mice mutant for Egfr and Shp2 have defective cardiac semilunar valvulogenesis. Nat Genet. 2000;24:296–299. doi: 10.1038/73528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araki T, et al. Mouse model of Noonan syndrome reveals cell type– and gene dosage–dependent effects of Ptpn11 mutation. Nat Med. 2004;10:849–857. doi: 10.1038/nm1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jopling C, van Geemen D, den Hertog J. Shp2 knockdown and Noonan/LEOPARD mutant Shp2-induced gastrulation defects. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.