Abstract

Liver biopsy is considered the gold-standard method for the assessment of liver fibrosis during follow-up of hepatitis C virus-infected patients, but this invasive procedure is not devoid of complications. The aim of the present study was to identify novel non-invasive markers of fibrosis progression. By microarray analysis, we compared transcript levels in two extreme stages of fibrosis from 16 patients. Informative transcripts were validated by real-time PCR and used for the assessment of fibrosis in 23 additional patients. Sixteen transcripts were found to be dysregulated during the fibrogenesis process. Among them, some were of great interest because their corresponding proteins could be serologically measured. Thus, the protein levels of inter-α inhibitor H1, serpin peptidase inhibitor clade F member 2, and transthyretin were all significantly different according to the four Metavir stages of fibrosis. In conclusion, we report here that dysregulation, at both the transcriptional and protein levels, exists during the fibrogenesis process. Our description of three novel serum markers and their potential use as serological tests for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis open new opportunities for better follow-up of hepatitis C virus-infected patients.

Liver fibrosis results from chronic injury of the liver with an excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as glycoproteins, collagens, and proteoglycans. In industrialized countries, the main causes of liver fibrosis include chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcohol abuse, and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. The accumulation of ECM proteins distorts the hepatic architecture by forming ECM complexes and a fibrous scar. In addition, the development of regenerating nodules results in progression to cirrhosis, which induces hepatocellular dysfunctions and can lead to clinical complications such as hepatic insufficiency, portal hypertension, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurrence.1,2

In the majority of HCV-infected patients, progression to cirrhosis occurs after an interval of 15 to 20 years,1 can be asymptomatic and then unobserved. In this context, it is very important to identify markers for the different stages of fibrosis. Hitherto liver biopsy is considered as the gold-standard method for the establishment of liver disease diagnosis and for the assessment of liver fibrosis during the follow-up of patients. Histological examination is useful for assessing the stage of fibrosis and the necroinflammatory grade,3,4 but liver biopsy is an invasive procedure, with possible pain and major complications. Furthermore, sampling variations can occur and not exactly predict fibrosis progression because the effectiveness of fibrosis determination varies according to the length of biopsy sample.5 Therefore, there is an urgent need for reliable and non-invasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis. Scores that include routine laboratory tests have been proposed to assess fibrosis in chronic HCV infection. Among these, we can quote some scores, which are correlated with the degree of fibrosis: aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index6,7; Fibrometer (BBL Fibro System) calculated with platelet count, prothrombine time, aspartate aminotransferase, serum concentration of α2-macroglobulin, hyaluronate, urea, and age of patient 8; Fibrotest (Biopredictive) combines serum concentrations of α2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, γ-glutamyltransferase, bilirubin, and apolipoprotein A1; MP3 score combines procollagen type III N-terminal peptide, a marker of fibrogenesis, and the matrix metalloproteinase 1.9 Diagnostic performance of various paired combination scores, has been evaluated but the best combinations could only select one-third of patients for whom either absence or presence of extensive fibrosis could be predicted with more than 90% of certainty.9 Another non-invasive method used for the diagnostic of cirrhosis is the Fibroscan (Echosens, Paris), which is related to assessment of the tissue stiffness and is a valuable method for the evaluation of mild fibrosis or cirrhosis in HCV-infected patients.10 In conclusion, most of these non-invasive methods are useful for detecting mild or advanced fibrosis, but are not effective for differentiating the intermediate stages of fibrosis.11

In HCC, numerous genome-wide analyses of abnormal gene expression have been performed and have shown transcript deregulations during its development and especially between early HCC and dysplastic nodules, with the description of specific markers for early HCC development.12,13,14,15 We have previously observed transcripts whose expression significantly differs between HCC-free and HCC-associated cirrhosis and among them, some have a prognostic interest.16 In contrast, the number of comparative studies devoted to only fibrosis progression was still scarce. In an HCV-related fibrosis context, studies have underlined transcript regulation differences between normal liver, mild and severe fibrosis.17,18,19 Likewise, studies have shown a dysregulation in the transcriptional network regulated by interferons in the first stage of HCV-induced liver fibrosis.18,20

So, the aim of the present study was to identify specific transcripts whose expression could be differentially regulated during the fibrogenesis process in an HCV context. We now report that such transcript dysregulations do exist according to the different stages of fibrosis and some of their related-proteins could be used as novel serum markers of fibrosis progression.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Needle liver biopsy specimens (n = 51) were obtained from HCV-infected patients and histology for fibrotic staging (F) and inflammatory process (A) was determined by the department of pathology according to the METAVIR score 3: A0, no activity; A1, mild; A2, moderate; A3, marked; F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis without septa; F2 portal fibrosis with few septa; F3, septal fibrosis without cirrhosis; and F4, cirrhosis. Resting samples not used by the pathologist were then used for RNA extraction. Patients with an HCC-associated cirrhosis or hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected were excluded from this study. HBV and HCV infections were serologically determined in every patient as previously described.21 A standard normal liver reference was pooled from eight samples of normal, uninfected human liver tissue obtained from patients operated on for a benign liver tumor or a metastasis of a non-hepatic cancer. Liver fragments were obtained under strict anonymity from Charles Nicolle Hospital (Rouen, France). According to the current French rules and ethical guidelines, neither an informed consent nor an advice from an ethical committee are requested before RNA analysis in these liver resting fragments which would otherwise be discarded.

Serum samples (n = 100) collected from an independent group of other HCV-infected patients were obtained under strict anonymity from the virology unit of Charles Nicolle Hospital (Rouen, France) and were also resting samples, which had been previously analyzed for HCV antibodies and detectable serum HCV RNA levels. A pool of normal serum samples was obtained from 10 non-infected patients. Biological and clinical data from the 51 liver fragments and 100 serum samples are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biological and Clinical Data from Patients with Different Stages of Fibrosis

| A. Liver samples for mRNA quantification

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients* | n | Male/female | Age† | Inflammatory score‡ |

| F1–1 to F1–8 | 8 | 4/4 | 47.6 ± 11.6 | (2 A0/5 A1/1 A2/0 A3) |

| F1–9 to F1–20 | 12 | 5/7 | 49.6 ± 10 | (1 A0/6 A1/4 A2/1 A3) |

| F2–1 to F2–6 | 6 | 3/3 | 54.8 ± 14.8 | (0 A0/1 A1/3 A2/2 A3) |

| F3–1 to F3–6 | 6 | 5/1 | 49.5 ± 11.7 | (0 A0/4 A1/1 A2/1 A3) |

| F4–1 to F4–8 | 8 | 6/2 | 53.9 ± 16.3 | (0 A0/2 A1/5 A2/1 A3) |

| F4–9 to F4–19 | 11 | 7/4 | 58.1 ± 11.3 | (0 A0/5 A1/4 A2/2 A3) |

| B. Serum samples for proteins quantification

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients* | n | Male/female | Age† | Inflammatory score‡ |

| F1–21 to F1–46 | 26 | 12/14 | 46.0 ± 10.5 | (3 A0/9 A1/9 A2/5 A3) |

| F2–7 to F2–30 | 24 | 13/11 | 51.2 ± 11.9 | (1 A0/8 A1/12 A2/3 A3) |

| F3–7 to F3–29 | 23 | 18/5 | 52.5 ± 10.9 | (0 A0/8 A1/11 A2/4 A3) |

| F4–20 to F1–46 | 27 | 16/11 | 53.3 ± 10.6 | (0 A0/4 A1/13 A2/10 A3) |

A: Underlined samples were studied by microarray and qRT-PCR; no underlined samples were only studied by qRT-PCR. B: These samples correspond to sera obtained from HCV-infected patients.

F1, fibrosis METAVIR stage 1; F2, fibrosis METAVIR stage 2; F3, fibrosis METAVIR stage 3; F4, fibrosis METAVIR stage 4.

Mean ± SD.

In parenthesis, number of patients with their inflammatory score, from A0 to A3, in each subgroup.

Transcriptome Analysis and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

RNA extraction from tissues was done with MiniRNA isolation I kit (Zymo Research) then was amplified with MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). Our set of human cDNA probes dubbed Liverpool that is tailored to a complete coverage of the human liver transcriptome under healthy or pathological conditions (ca. 104 genes), the associated LiverTools database, as well as the procedures from array preparation to data handling have all been detailed.22 In brief, every antisense (a)RNA sample was subjected to three rounds of hybridization and the resulting signals were normalized from the average signal of every spot (mean gray) on the matching hybridization image. The mean signal per transcript was used for selections of significantly regulated transcripts. Probe re-sequencing was done with an ABI3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR of non-amplified transcripts was done with a Light Cycler (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany). Transcript normalization was done with the 18S RNA. The primers designed with the Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) were: acetyl-Coenzyme A acyltransferase 2 (ACAA2), forward 5′-CATAAAACCTTCCCTGAAGTGC-3′, reverse 5′-AATTTTCAGGCCCATTTGGA-3′ (100 bp product size); alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (class II), pi polypeptide (ADH4), forward 5′-GTCTGCTTGGATGTGGGTTT-3′, reverse 5′-TGATTCTGGAAGCTCCTGCT-3′ (150 bp product size); acireductone dioxygenase 1 (ADI1), forward 5′-GGAGAAGGGAGACATGGTGA-3′, reverse 5′-ACGAGGCACGTGTTAGTTCC-3′ (216 bp product size); aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 family (ALDH2), forward 5′-GTTGGGAGAGCCAACAATTC-3′, reverse 5′-ACTCCCCGACATCTTGTAGC-3′ (171 bp product size); brain and reproductive organ-expressed (TNFRSF1A modulator) (BRE), forward 5′-AAGTATGCCACCTGCTCACC-3′, reverse 5′-TCTTTCCACATCAGCAGCAG-3′ (160 bp product size); Cell division cycle associated 2 (CDCA2), forward 5′-GGCTCTCCTGAAACAAACCA-3′, reverse 5′-CGCTGAGACCTTCCTTTCTG-3′ (271 bp product size); eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B subunit 1 alpha (EIF2B1), forward 5′-GTGCCAAAGCACAGAACAAA-3′, reverse 5′-TGATTAAGGAAGGGGCAGTG-3′ (192 bp product size); hemopexin (HPX), forward 5′-TGTGGATGCGGCCTTTATCT-3′, reverse 5′-GGCCAAGGGACTTTTCCATA-3′ (167 bp product size); inter-alpha (globulin) inhibitor H1 (ITIH1), forward 5′-GTGAATGGACAGCTCATTGG-3′, reverse 5′-CCACCAGGTTCCTCTTCTTG-3′ (232 bp product size); KIAA1949, forward 5′-GGGACTCTCGGGATTTAAGC-3′, reverse 5′-TGTAAACCAGGCTGTGGTCA-3′ (141 bp product size); metallothionein 1H (MT1H), forward 5′-ACGTGTTCCACTGCCTCTTC-3′, reverse 5′-CTTCTTGCAGGAGGTGCATT-3′ (152 bp product size); REV1 homolog (S. cerevisiae), forward 5′-ACCGAAGAGGAGCACAAAGA-3′, reverse 5′-CCATTCCATTTCCCTGAAGA-3′ (152 bp product size); ribosomal protein S26 (RPS26), forward 5′-CAGCCTATTCGCTGCACTAAC-3′, reverse 5′-CATACAGCTTGGGAAGCACA-3′ (151 bp product size); serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade F (alpha-2 antiplasmin), member 2 (SERPINF2), forward 5′-CAAGTTTGACCCGAGCCTTA-3′, reverse 5′-TACCTGGGACACGTTCCATT-3′ (211 bp product size); signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 interacting protein 1 (STATIP1), forward 5′-AAGACTCTGCTTGCCTCAGC-3′, reverse 5′-TGCTTTTTCCACAATGACCA-3′ (197 bp product size); transthyretin (prealbumin, amyloidosis type I)(TTR), forward 5′-CAGAAAGGCTGCTGATGACA-3′, reverse 5′-ATGCCAAGTGCCTTCCAGTA-3′ (153 bp product size); and 18S, forward 5′-GTGGAGCGATTTGTCTGGTT-3′, reverse 5′-CGCTGAGCCAGTCAGTGTAG-3′ (200 bp product size).

Data Mining

Our raw data were deposited in the GEO repository under accession GSE 11536. The TIGR Multiexperiment viewer (Tmev version 2.2, http://www.tm4.org) was used for i) unsupervised hierarchical clustering using the Pearson correlation and complete linkage options, ii) supervised classifications such as Significance Analysis of Microarrays with parameters adjusted to an estimated false discovery rate (FDR) <1% or K-nearest neighbor classification, and iii) evaluation of sample re-assignment by a jacknife procedure (106 iterations). Another, supervised classification was done by Support Vector Machine (http://svm.sdsc.edu/). Detailed functions were retrieved with the SOURCE (http://genome-www5.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/source/sourceSearch) and/or OMIM (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez) tools. Statistics were performed with the GraphPad Instat software, version 3 (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA).

Quantification of Serum Proteins

Relative plasmatic concentration of ITIH1 protein was measured using Western blot. In brief, plasma aliquots were mixed with gel loading buffer and separated on NuPAGE Novex 4 to 12% Bis-Tris Mini Gels (Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred out of the gels onto nylon membranes (Hybond Amersham) blocked with 5% dry milk in PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, and then probed with goat polyclonal antibody raised against human ITIH1 (1 μg/ml, Tebu-Bio) in milk at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed with PBS Tween 0.5% and incubated with an appropriate Alexa Fluor 680-labeled secondary antibody (2 μg/ml, Invitrogen) for 1 hour. Finally, proteins on the membranes were detected using the LI-COR Odyssey and the use of a standard (pool of normal serum samples obtained from 10 non-infected patients) allowed to calculate the relative amount of ITIH1 present in all serum samples.

The concentration of SERPINF2 in plasma was measured with a sandwich-type immunoassay. A rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-SERPINF2 (1/500, Abcam) was first immobilized on a Nunc 96-well immunoplate (Fisher-bioblock) by incubating overnight in PBS. After washing four times with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20, wells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS. After 1 hour-incubation, plates were washed, and serum samples diluted 20-fold were incubated for 2 hours. In the same time, a recombinant human SERPINF2 (R&D Systems) was used at serial concentrations (31.25 ng/ml, 62.5 ng/ml, 125 ng/ml, 250 ng/ml, 500 ng/ml, 1 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml). Subsequently, 100 μl of goat polyclonal antibody anti-SERPINF2 (2 μg/ml, Euromedex) was added and incubated 2 hours. After washing, TMB single solution chromogen (Invitrogen) was added and incubated 10 minutes then the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μl of HCl (1 M/L). Finally, the intensity of the yellow color was read at OD 450 nm using Metertech ∑960 (Bioblock). A scale of increasing concentrations of recombinant the protein was used to determine the SERPINF2 concentration in the samples.

The concentration of TTR protein in serum was determined by nephelometry using the BN Systems. The N antiserum to Human prealbumin kit (Dade Behring) was used according to the manufacturer instructions.

Results

Identification of a Gene Expression Signature Discriminating F1 vs F4 Samples

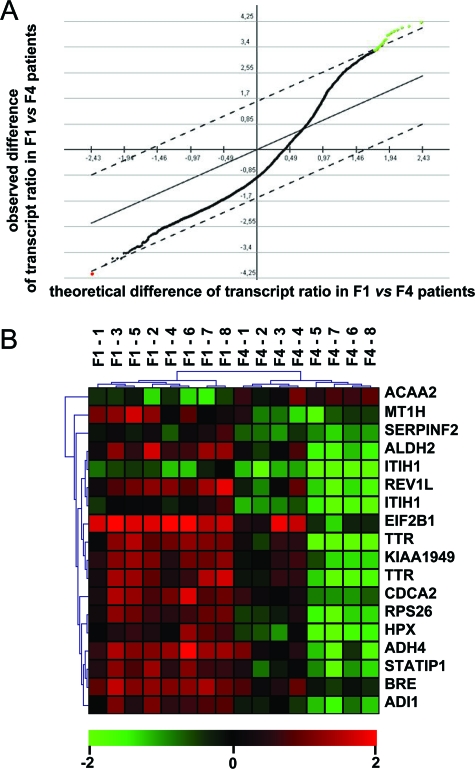

To define which genes were able to be discriminating between different stages of fibrosis, we have analyzed microarray data obtained from the 16 underlined amplified fibrosis samples (F1–1 to F1–8 and F4–1 to F4–8 see Table 1). We selected by Significance Analysis of Microarrays (FDR set to <1%) 16 transcripts whose levels significantly differed between F1 vs F4 fibrosis stage. As shown in Figure 1A, when comparing these 16 transcript levels between F1 vs F4, their mean levels in F4 fibrosis stage were mainly down-regulated (green dots) with only one transcript level up-regulated (red dot). Furthermore, levels of these 16 transcripts completely separated by unsupervised hierarchical clustering two major clusters comprised of i) the fibrosis METAVIR stage F1, and ii) the fibrosis METAVIR stage F4 (Figure 1B). This was supported by a jacknife procedure (100% success) and, in addition, no liver sample was misclassified.

Figure 1.

Clustering of patients according to fibrosis progression. A: Selection of transcripts with a significantly abnormal ratio of abundance in [fibrosis stage/standard normal liver]. Black + green + red dots: 9160 transcripts with an abnormal ratio in at least 1/16 patients. Green dots: 15 informative transcripts (17 probes) with a significantly deceased ratio in F4 vs F1 fibrotic patients as selected by Significance Analysis of Microarrays with a FDR <1%. Red dot: one informative transcript with a significantly increased ratio in F4 vs F1 fibrotic patients. Ordinate, observed difference of transcript ratio between F1 vs F4 patients (log2 scale); abcissa, theoretical difference. B: Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 16 fibrotic patients with the 16 (15 + 1) above defined transcripts. Horizontal clusters: F1 fibrosis stage (n = 8); F4 fibrosis stage (n = 8). Note that perfect classification of the samples was further evaluated by a jacknife procedure (106 iterations). Vertical clusters: transcripts. Note that two transcripts were each detected with two different cDNA probes. The cDNA probes used for the identification of these 16 transcripts were all re-verified by sequencing. Scale bar (log2 ratio): decreased (green), increased (red) or identical mRNA level (black) in fibrosis sample versus standard normal liver.

We next validated the above differences by real-time qRT-PCR in our entire population of 39 non-amplified fibrotic samples (20 F1 and 19 F4). The median levels of most transcripts (81%: ADH4, ADI1, ALDH2, BRE, EIF2B1, HPX, ITIH1, KIAA1949, MT1H, RPS26, SERPINF2, STATIP1, TTR) significantly varied according the fibrosis stage F1 vs the fibrosis stage F4. In addition, the median levels of these transcripts were significantly correlated with the fibrosis progression (Spearman rank correlation, P < 0.05) but not with the inflammation process (except MT1H). Furthermore, when used unsupervised (unsupervised hierarchical clustering) or supervised training/testing procedures (K-nearest neighbor classification and Support Vector Machine) for classifying fibrosis stage, the 16 above identified transcripts resulted in a proper classification of 87% to 91% test samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

Performance of Unsupervised or Supervised Classification Tools for Fibrotic Samples from Quantitative PCR Analysis of mRNA

| Samples† | n‡ | Tool*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHC | SVM | KNNC | ||

| F1 | 20 | 83%§ | 100% | 100% |

| F4 | 19 | 91% | 82% | 82% |

| all test samples | 39 | 87% | 91% | 91% |

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering (UHC) was done with the 39 fibrotic samples (20F1 and 19F4). Supervised training/testing procedures (KNNC; SVM) were each done by separating these 39 samples into 16 training (F1–1 to F1–8, F4–1 to F4–8) and 23 test samples (F1–9 to F1–20, F4–9 to F4–19).

mRNA expression of the 16 defined transcripts (ACAA2, ADH4, ADI1, ALDH2, BRE, CDCA2, EIF2B1, HPX, ITIH1, KIAA1949, MT1H, REV1L, RPS26, SERPINF2, STATIP1, and TTR) were measured from every sample by qRT-PCR.

Number of samples for each group.

Percentage of properly classified test samples.

mRNA Expression of the Dysregulated Genes in the Intermediate Stages of Fibrosis

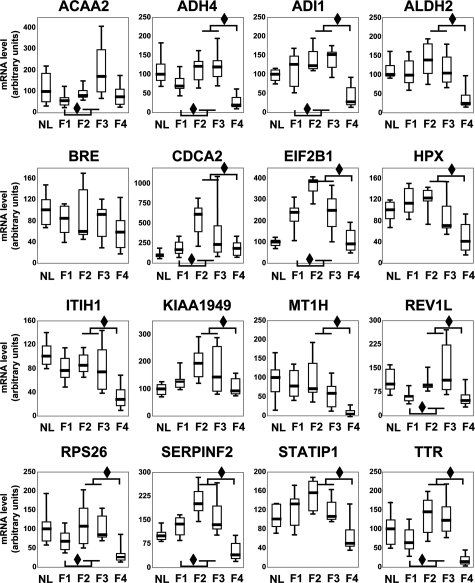

We have researched if these transcripts could also separate the four stages of fibrosis. All of the identified transcripts showed significant differences of expression levels in at least one comparison between two groups of fibrosis stages. To not overload the Figure 2, only two comparisons of transcript levels have been represented: mild (F1) vs moderate fibrosis (F2–F3) and moderate (F2–F3) vs advanced (F4) fibrosis. The two intermediate stages (F2 and F3) have been gathered because the number of samples in each group was too small. Thus, most of the transcripts showed an up-regulation during the F1 to F2-F3 progression (transcripts with a diamond in down left, 9/16, 56%), followed by a down-regulation during the F2-F3 to F4 progression (transcripts with a diamond in up right, 14/16, 88%). Furthermore, most of these transcripts showed expression levels significantly different between mild or moderate fibrosis and cirrhosis (F1 vs F4 : 81%, F2 vs F4 : 88% and F3 vs F4 : 81%). So, we can hypothesize that these transcripts could allow a better identification of the four stages of fibrosis.

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of the 16 transcripts in the four different stages of fibrosis. Levels of these transcripts were determined by real-time qRT-PCR (in 20 F1, 6 F2, 6 F3, and 19 F4 samples) and normalized with the 18S RNA level. Every transcript name is noted on top and its level per fibrosis stage is expressed on the ordinate as a percentage of the mean level in F1 stage of fibrosis (100%). Boxplots depict groups of numerical data through their five number summaries: the first decile (the extreme of the lower whisker), the lowest quartile (the lower hinge), the median (the horizontal thick line), the upper quartile (the upper hinge), and the ninth decile (the extreme of the upper whisker). Two comparisons were performed: F1 vs F2–F3 stage and F2–F3 vs F4 stage to highlight the variations of transcript levels during the evolution and progression of fibrosis. Difference between medians is shown as a diamond (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney’s test). The median levels of most transcripts (81%: ADH4, ADI1, ALDH2, BRE, EIF2B1, HPX, ITIH1, KIAA1949, MT1H, RPS26, SERPINF2, STATIP1, TTR) significantly varied according stage F1 vs stage F4.

Serum Proteins Quantification

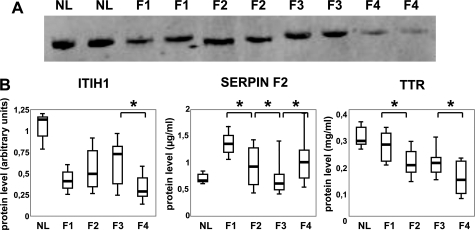

Among the 16 above-mentioned transcripts, only four coded for serum proteins, which could be thus serologically measured and become very interesting for a diagnosis purpose. Among these, ITIH1, SERPINF2, and TTR have been measured in the serum samples listed in Table 1 but we failed to quantify the HPX protein level (data not shown). These 100 serum samples were divided in four groups, which corresponded to the four stages of fibrosis.

The level of these three proteins was significantly different in the four groups of fibrosis (P < 0.01; Kruskall-Wallis test). Moreover, as shown in Figure 3A,B and Table 3, this level was significantly different according to the stage of fibrosis. Indeed, the ITIH1 protein level increased during the fibrogenic process and strongly decreased at stage F4 (P < 0.005, Mann-Whitney test between F3 and F4).

Figure 3.

Serum quantification for three proteins. A: Expression level of ITIH1 as detected by a Western blot analysis in normal liver (NL) and in fibrotic liver (F1, F2, F3, and F4). Equal amounts of transferred proteins were estimated by Ponceau Red stained filters (load control). B: Expression level for ITIH1, SERPINF2, and TTR. This quantification was determined by Western blot for ITIH1, by sandwich-type immunoassay for SERPINF2 or by nephelometry for TTR. For every protein name is noted on top and its level per fibrosis stage is expressed on the ordinate. Boxplot graphic representation is the same as described in Figure 2 (see legend). To not overload this figure, among the three performed tests: F1 vs F2 or F2 vs F3 or F3 vs F4 only those with a significant difference are represented and shown as a star (P < 0,05, Mann-Whitney’s test). For more details about all other comparisons see Table 3.

Table 3.

Significant Differences of Proteins Quantification According to Fibrosis Stages

| Protein | F1 vs F2* | F1 vs F3* | F1 vs F4* | F2 vs F3* | F2 vs F4* | F3 vs F4* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITIH1 | NS† | 0.03 | 0.04 | NS | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| SERPINF2 | 0.0007 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.05 | NS | 0.006 |

| TTR | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.0001 | NS | 0.005 | 0.02 |

Different comparisons between two fibrosis stages.

P value calculated by Mann-Whitney test; NS, non significant.

In contrast, SERPINF2 and TTR protein levels did not increased during the fibrotic process. The SERPINF2 protein level significantly decreased during the F1, F2, and F3 stages (P < 0.0007, Mann-Whitney test between F1 and F2; P < 0.05 between F2 and F3) and slightly increased during F4 (P < 0.006, Mann-Whitney test between F3 and F4). As expected, this SERPINF2 level is significantly lower in F4 than in F1 stage.

Finally, the TTR protein level significantly and gradually decreased during the fibrotic process with the lowest level observed in F4. In fact, the TTR protein level was significantly lower in F2 than in F1 (P < 0.004, Mann-Whitney test) with no difference observed between F2 and F3 and again, a level significantly lower in F4 than in F3 (P < 0.02, Mann-Whitney test). Furthermore, TTR expression was correlated with albumin expression (Spearman rank correlation, r = 0.31, P = 0.02). But albumin expression was not able to differentiate the intermediate stages of fibrosis. Indeed, albumin level was significantly lower in F4 than in F1 (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test), but no difference was observed for the other comparisons.

Overall, the transcript dysregulations observed in our microarrays data were associated with protein dysregulations whose levels showed significant gradual differences according to the stage of the fibrosis process.

Discussion

Our search was first focused on the transcript dysregulations found in mild (F1 stage) vs severe (F4 stage) fibrosis. Using Significance Analysis of Microarrays with a tight FDR we identified a total of 16 transcripts with strong variations associated to the fibrosis progression, and which perfectly classified the two groups of patients. Among these 16 transcripts, a subgroup of dysregulated genes was involved in hepatic metabolism. Indeed, normal detoxification enzymes such as ADH4 and ALDH2 were down-regulated during fibrosis progression. Likewise, HPX, which is implicated in detoxification of the hemoglobin degradation pathways, was down-regulated. We also noticed the decrease of secreted proteins that were synthesized by liver such as SERPINF2 and TTR. Thus, liver specific functions decreased during fibrogenesis process.

This transcriptome-wide analysis was realized with amplified transcripts by MessageAmp II aRNA Amplification Kit. The fidelity of results for differential gene expression following amplification of small quantities of mRNA has been discussed and several studies conducted to determine whether a such amplification of mRNA was able to introduce bias, have reported that the latter was minimal.23,24,25 Furthermore, differences found in gene expression were next validated by real-time qRT-PCR.

In a second step, we aimed to search how these transcripts were regulated during the fibrogenesis progression. Transcripts significantly dysregulated between F1 and F4 fibrosis stages and mainly down-regulated in F4 usually showed an up-regulation during the F1 to F2-F3 progression followed by a strong down-regulation during the F3 to F4 evolution. However, if these 16 dysregulated transcripts with gradual variations could be used as novel markers of the fibrosis progression, the variations of their mRNA levels could be only assessed using biopsies. Nevertheless, as noticed previously, biopsy is an invasive procedure and sampling variations can result in a wrong fibrosis progression assessment.5 That is why the determination of their corresponding protein levels was very more interesting especially for those serologically detectable that could be quantified in blood samples using a simple laboratory test during the follow-up of HCV-infected patients. In the present study, we documented that the variation at the ITIH1 protein level in serum was in agreement with the results obtained at the transcriptional level. This is not the case for SERPINF2 and TTR. However, such discrepancies between transcript levels and protein levels were not unusual and have been previously noticed.26,27 Moreover, as it was very difficult to obtain samples (biopsy and serum) from the same patients, we have thus searched the variations of transcript expression and protein concentration on two independent groups of patients. Nevertheless, levels of SERPINF2 and TTR showed significant differences between the four fibrosis stages and we though that such proteins could be used as novel serum markers of the fibrotic process.

Interestingly, two of these three proteins were not previously associated with fibrosis progression in an HCV context but their down-regulation has already been described in liver diseases. Indeed, TTR, a negative acute-phase protein that was significantly down-regulated in various liver diseases such as chronic hepatitis was decreased in the serum of HBV-infected patients.28 This variation found in serum of HBV- and now in HCV-infected patients underlines the weight of the inflammatory process during the viral infection.

Besides, SERPINF2, also called α-2 anti-plasmin, is the major inhibitor of the proteolytic enzyme plasmin. A decreased level of SERPINF2 resulted in an increased level of activated plasmin, which could alter the integrity of the ECM. The decreased expression of SERPINF2 was already observed in HCC of HBV-infected patients,29 and, in this context, it seems that alteration of ECM components could lead to cancer development. Our data suggest that SERPINF2 could be early involved in a mechanism that would result in an alteration of the ECM during the fibrosis progression.

In contrast, ITIH1 was expressed in liver, but its dysregulation were not previously observed in liver diseases. In fact, the function of ITIH1 is not yet clearly defined. Indeed, ITIH1 is one of the high chains of the inter-α-trypsin inhibitor family that plays a major role in ECM stability and integrity,30 and in inflammation by hyaluronic acid-binding.31 The gene expressions of the ITIH family were commonly decreased in a remarkable number of human tumor tissues, but this observation was not found for ITIH1.32 In fact, the gene expression of ITIH1 has not been assessed in liver diseases. Our results could suggest that the decreased ITIH1 level was involved in a decreased ECM stability and in liver fibrosis progression.

As previously mentioned, several methods, such as Fibrotest (Biopredictive) and Fibroscan (Echosens, Paris), are nowadays used to assess fibrosis without biopsy. But most of these non-invasive methods are useful for detecting absence or advanced fibrosis but are not effective for differentiating the intermediate stages of fibrosis.10,11 Therefore, there is an urgent need for new reliable non-invasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis. In this context, we have identified three novel proteins, which now must be validated for additional studies on a larger number of patients and also in patients who develop fibrosis progression in a longitudinal manner. Unfortunately, we did not have such samples to realize this study. However, these three potential markers have shown significant differences of serum levels and despite variations within groups, they could be combined together or with other routine laboratory tests to increase their clinical utility as diagnostic markers.

In conclusion, our data point to transcript and protein dysregulations of ITIH1, SERPINF2, and TTR during the fibrogenesis process with a gradual decrease level of these proteins during the development of fibrosis to its end stage cirrhosis. These findings open new perspectives for a better follow-up of the HCV-infected patients since these proteins could be used as novel serological tests for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the technicians of the biochemistry unit of Charles Nicolle Hospital for their excellent technical assistance for TTR assessment by nephelometry.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Frédérique Caillot, Inserm Unité 905, Faculté de Médecine-Pharmacie, 22 Bvd Gambetta, 76183 Rouen cedex, France. E-mail: frederique.caillot@etu.univ-rouen.fr.

Supported in part by grants from Association de Recherche sur le Cancer, Ligue contre le Cancer, Institut de Recherche sur les boissons, and Conseil Régional de Haute-Normandie to J.-P.S. F.C. is recipient of a fellowship from the French Ministry for Research and ARC.

The author J.-P.S. is deceased.

References

- Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockey DC, Bissell DM. Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S113–S120. doi: 10.1002/hep.21046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group Hepatology. 1996;24:289–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman ZD. Grading and staging systems for inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2007;47:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner C, Struber G, Liegl B, Leibl S, Ofner P, Bankuti C, Bauer B, Stauber RE. Comparison and validation of simple noninvasive tests for prediction of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1376–1382. doi: 10.1002/hep.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calès P, Oberti F, Michalak S, Hubert-Fouchard I, Rousselet MC, Konaté A, Gallois Y, Ternisien C, Chevaillier A, Lunel F. A novel panel of blood markers to assess the degree of liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2005;42:1373–1381. doi: 10.1002/hep.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy V, Hilleret MN, Sturm N, Trocme C, Renversez JC, Faure P, Morel F, Zarski JP. Prospective comparison of six non-invasive scores for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2007;46:775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettaneh A, Marcellin P, Douvin C, Poupon R, Ziol M, Beaugrand M, de Ledinghen V. Features associated with success rate and performance of FibroScan measurements for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in HCV patients: a prospective study of 935 patients. J Hepatol. 2007;46:628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen AA, Wan AF, Myers RP. FibroTest and FibroScan for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2589–2600. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuma M, Sakamoto M, Yamazaki K, Ohta T, Ohki M, Asaka M, Hirohashi S. Expression profiling in multistage hepatocarcinogenesis: identification of HSP70 as a molecular marker of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:198–207. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulouarn C, Derambure C, Lefebvre G, Daveau R, Hiron M, Scotte M, Francois A, Daveau M, Salier JP. Global gene repression in hepatocellular carcinoma and fetal liver, and suppression of dudulin-2 mRNA as a possible marker for the cirrhosis-to-tumor transition. J Hepatol. 2005;42:860–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka N, Oka M, Yamada-Okabe H, Mori N, Tamesa T, Okada T, Takemoto N, Sakamoto K, Hamada K, Ishitsuka H, Miyamoto T, Uchimura S, Hamamoto Y. Self-organizing-map-based molecular signature representing the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Chen Y, Wurmbach E, Roayaie S, Fiel MI, Schwartz M, Thung SN, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Villanueva A, Battiston C, Mazzaferro V, Bruix J, Waxman S, Friedman SL. A molecular signature to discriminate dysplastic nodules from early hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1758–1767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillot F, Derambure C, Bioulac-Sage P, Francois A, Scotte M, Goria O, Hiron M, Daveau M, Salier JP. Transient and etiology-related transcription regulation in cirrhosis prior to hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:300–309. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselah T, Bieche I, Laurendeau I, Paradis V, Vidaud D, Degott C, Martinot M, Bedossa P, Valla D, Vidaud M, Marcellin P. Liver gene expression signature of mild fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:2064–2075. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MW, Walters KA, Korth MJ, Fitzgibbon M, Proll S, Thompson JC, Yeh MM, Shuhart MC, Furlong JC, Cox PP, Thomas DL, Phillips JD, Kushner JP, Fausto N, Carithers RL, Jr, Katze MG. Gene expression patterns that correlate with hepatitis C and early progression to fibrosis in liver transplant recipients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:179–187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao RX, Hoshida Y, Otsuka M, Kato N, Tateishi R, Teratani T, Shiina S, Taniguchi H, Moriyama M, Kawabe T, Omata M. Hepatic gene expression profiles associated with fibrosis progression and hepatocarcinogenesis in hepatitis C patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1995–1999. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i13.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieche I, Asselah T, Laurendeau I, Vidaud D, Degot C, Paradis V, Bedossa P, Valla DC, Marcellin P, Vidaud M. Molecular profiling of early stage liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Virology. 2005;332:130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derambure C, Coulouarn C, Caillot F, Daveau R, Hiron M, Scotte M, Francois A, Duclos C, Goria O, Gueudin M, Cavard C, Terris B, Daveau M, Salier JP. Genome-wide differences in hepatitis C- vs alcoholism-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1749–1758. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulouarn C, Lefebvre G, Derambure C, Lequerre T, Scotte M, Francois A, Cellier D, Daveau M, Salier JP. Altered gene expression in acute systemic inflammation detected by complete coverage of the human liver transcriptome. Hepatology. 2004;39:353–364. doi: 10.1002/hep.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacek DC, Passerini AG, Shi C, Francesco NM, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Powell S, Bischof H, Winkler H, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Fidelity and enhanced sensitivity of differential transcription profiles following linear amplification of nanogram amounts of endothelial mRNA. Physiol Genomics. 2003;13:147–156. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00173.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li T, Liu S, Qiu M, Han Z, Jiang Z, Li R, Ying K, Xie Y, Mao Y. Systematic comparison of the fidelity of aRNA, mRNA and T-RNA on gene expression profiling using cDNA microarray. J Biotechnol. 2004;107:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AL, Costouros NG, Wang E, Qian M, Marincola FM, Alexander HR, Libutti SK. Advantages of mRNA amplification for microarray analysis. Biotechniques. 2002;33:906–912, 914. doi: 10.2144/02334mt04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum D, Colangelo C, Williams K, Gerstein M. Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol. 2003;4:117. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin RD, Whetton AD. Systematic proteome and transcriptome analysis of stem cell populations. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1587–1591. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He QY, Lau GK, Zhou Y, Yuen ST, Lin MC, Kung HF, Chiu JF. Serum biomarkers of hepatitis B virus infected liver inflammation: a proteomic study. Proteomics. 2003;3:666–674. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KY, Lai PB, Squire JA, Beheshti B, Wong NL, Sy SM, Wong N. Positional expression profiling indicates candidate genes in deletion hotspots of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1546–1554. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bost F, Diarra-Mehrpour M, Martin JP. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor proteoglycan family–a group of proteins binding and stabilizing the extracellular matrix. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:339–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salier JP, Rouet P, Raguenez G, Daveau M. The inter-alpha- inhibitor family : from structure to regulation. Biochem J. 1996;315:1–9. doi: 10.1042/bj3150001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm A, Veeck J, Bektas N, Wild PJ, Hartmann A, Heindrichs U, Kristiansen G, Werbowetski-Ogilvie T, Del Maestro R, Knuechel R, Dahl E. Frequent expression loss of Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain (ITIH) genes in multiple human solid tumors: a systematic expression analysis. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]