Abstract

Nitrogenase-like light-independent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR) is involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Bacteriochlorophyll formation additionally requires the structurally related chlorophyllide oxidoreductase (COR). During catalysis, homodimeric subunit BchL2 or ChlL2 of DPOR transfers electrons to the corresponding heterotetrameric catalytic subunit, (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2. Analogously, subunit BchX2 of the COR enzymes delivers electrons to subunit (BchYZ)2. Various chimeric DPOR enzymes formed between recombinant subunits (BchNB)2 and BchL2 from Chlorobaculum tepidum or (ChlNB)2 and ChlL2 from Prochlorococcus marinus and Thermosynechococcus elongatus were found to be enzymatically active, indicating a conserved docking surface for the interaction of both DPOR protein subunits. Biotin label transfer experiments revealed the interaction of P. marinus ChlL2 with both subunits, ChlN and ChlB, of the (ChlNB)2 tetramer. Based on these findings and on structural information from the homologous nitrogenase system, a site-directed mutagenesis approach yielded 10 DPOR mutants for the characterization of amino acid residues involved in protein-protein interaction. Surface-exposed residues Tyr127 of subunit ChlL, Leu70 and Val107 of subunit ChlN, and Gly66 of subunit ChlB were found essential for P. marinus DPOR activity. Next, the BchL2 or ChlL2 part of DPOR was exchanged with electron-transferring BchX2 subunits of COR and NifH2 of nitrogenase. Active chimeric DPOR was generated via a combination of BchX2 from C. tepidum or Roseobacter denitrificans with (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum. No DPOR activity was observed for the chimeric enzyme consisting of NifH2 from Azotobacter vinelandii in combination with (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum or (ChlNB)2 from P. marinus and T. elongatus, respectively.

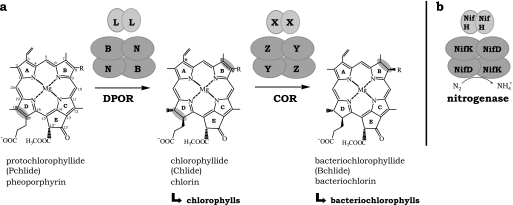

Chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis, as well as nitrogen fixation, are essential biochemical processes developed early in the evolution of life (1). During biological fixation of nitrogen, nitrogenase catalyzes the reduction of atmospheric dinitrogen to ammonia (2). Enzyme systems homologous to nitrogenase play a crucial role in the formation of the chlorin and bacteriochlorin ring system of chlorophylls (Chl)2 and bacteriochlorophylls (Bchl) (3, 4) (Fig. 1a). For the synthesis of both Chl and Bchl, the stereospecific reduction of the C-17-C-18 double bond of ring D of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) catalyzed by the nitrogenase-like enzyme light-independent (dark-operative) protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR) results in the formation of chlorophyllide (Chlide) (Fig. 1a, left) (5, 6). DPOR enzymes consist of three protein subunits which are designated BchN, BchB and BchL in Bchl-synthesizing organisms and ChlN, ChlB and ChlL in Chl-synthesizing organisms. A second reduction step at ring B (C-7-C-8) unique to the synthesis of Bchl converts the chlorin Chlide into a bacteriochlorin ring structure to form bacteriochlorophyllide (Bchlide) (Fig. 1a, right, Bchlide). This reaction is catalyzed by another nitrogenase-like enzyme, termed chlorophyllide oxidoreductase (COR) (7). COR enzymes are composed of subunits BchY, BchZ, and BchX.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of the three subunit enzymes DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase. a, during Chl and Bchl biosynthesis, ring D is stereospecifically reduced by the nitrogenase-like enzyme DPOR (subunit composition BchL2/(BchNB)2 or ChlL2/(ChlNB)2) leading to the chlorin Chlide. Subunits N, B, and L are named ChlN, ChlB, and ChlL in Chl-synthesizing organisms and BchN, BchB, and BchL in Bchl-synthesizing organisms. The synthesis of Bchl additionally requires the stereospecific B ring reduction by a second nitrogenase-like enzyme called COR, with the subunit composition BchX2/(BchYZ)2. COR catalyzes the formation of the bacteriochlorin Bchlide. Subunits Y, Z, and X of the COR enzyme are named BchY, BchZ, and BchX. b, the homologous nitrogenase complex has the subunit composition NifH2/(NifD/NifK)2. Rings A–E and the carbon atoms are designated according to IUPAC nomenclature (41). R is either a vinyl or an ethyl moiety. The position marked by an asterisk indicates either a vinyl or a hydroxyethyl moiety (42).

All subunits share significant amino acid sequence homology to the corresponding subunits of nitrogenase, which are designated NifD, NifK, and NifH, respectively (1) (compare Fig. 1, a and b). Whereas subunits BchL or ChlL, BchX and NifH exhibit a sequence identity at the amino acid level of ∼33%, subunits BchN or ChlN, BchY, NifD, and BchB or ChlB, BchZ, and NifK, respectively, show lower sequence identities of ∼15% (1). For all enzymes a common oligomeric protein architecture has been proposed consisting of the heterotetrameric complexes (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2, (BchYZ)2, and (NifD/NifK)2, which are completed by a homodimeric protein subunit BchL2 or ChlL2, BchX2, and NifH2, respectively (compare Fig. 1, a and b) (3, 7, 8).

Nitrogenase is a well characterized protein complex that catalyzes the reduction of nitrogen to ammonia in a reaction that requires at least 16 molecules of MgATP (2, 9, 10). During nitrogenase catalysis, subunit NifH2 (Fe protein) associates with and dissociates from the (NifD/NifK)2 complex (MoFe protein). Binding, hydrolysis of MgATP and structural rearrangements are coupled to sequential intersubunit electron transfer. For this purpose, NifH2 contains an ATP-binding motif and an intersubunit [4Fe-4S] cluster coordinated by two cysteine residues from each NifH monomer (1, 11). Electrons from this [4Fe-4S] cluster are transferred via a [8Fe-7S] cluster (P-cluster) onto the [1Mo-7Fe-9S-X-homocitrate] cluster (MoFe cofactor). Both of the latter clusters are located on (NifD/NifK)2, where dinitrogen is reduced to ammonia (10). Three-dimensional structures of NifH2 in complex with (NifD/NifK)2 revealed a detailed picture of the dynamic interaction of both subcomplexes (8, 12).

Based on biochemical and bioinformatic approaches, it has been proposed that the initial steps of DPOR reaction strongly resemble nitrogenase catalysis. Key amino acid residues essential for DPOR function have been identified by mutagenesis of the enzyme from Chlorobaculum tepidum (formerly denoted as Chlorobium tepidum) (3). The catalytic mechanism of DPOR includes the electron transfer from a “plant-type” [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin onto the dimeric DPOR subunit, BchL2, carrying an intersubunit [4Fe-4S] redox center coordinated by Cys97 and Cys131 in C. tepidum. Analogous to nitrogenase, Lys10 in the phosphate-binding loop (P-loop) and Leu126 in the switch II region of DPOR were found essential for DPOR catalysis. Moreover, it was shown that the BchL2 protein from C. tepidum does not form a stable complex with the catalytic (BchNB)2 subcomplex. Therefore, a transient interaction responsible for the electron transfer onto protein subunit (BchNB)2 has been proposed (3).

The subsequent [Fe-S] cluster-dependent catalysis and the specific substrate recognition at the active site located on subunit (BchNB)2 are unrelated to nitrogenase. The (BchNB)2 subcomplex was shown to carry a second [4Fe-4S] cluster, which was proposed to be ligated by Cys21, Cys46, and Cys103 of the BchN subunit and Cys94 of subunit BchB (C. tepidum numbering) (3). No evidence for any type of additional cofactor was obtained from biochemical and EPR spectroscopic analyses (5, 13). Thus, despite the same common oligomeric architecture, the catalytic subunits (BchNB)2 and (ChlNB)2 clearly differ from the corresponding nitrogenase complex, as no molybdenum-containing cofactor or P-cluster equivalent is employed (5, 14). From these results it was concluded that electrons from the [4Fe-4S] cluster of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 are transferred directly onto the Pchlide substrate at the active site of DPOR.

The second nitrogenase-like enzyme, COR, catalyzes the reduction of ring B of Chlide during the biosynthesis of Bchl (7). Therefore, an accurate discrimination of the ring systems of the individual substrates is required. COR subunits share an overall amino acid sequence identity of 15–22% for BchY and BchZ and 31–35% for subunit BchX when compared with the corresponding DPOR subunits (Table 1 and supplemental Figures S2–S4). In amino acid sequence alignments of BchX proteins with the closely related BchL or ChlL subunits of DPOR, both cysteinyl ligands responsible for [4Fe-4S] cluster formation and residues for ATP binding are conserved (1). Furthermore, all cysteinyl residues characterized as ligands for a catalytic [4Fe-4S] cluster in (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 are conserved in the sequences of subunits BchY and BchZ of COR (7). These findings correspond to a recent EPR study in which a characteristic signal for a [4Fe-4S] cluster was obtained for the COR subunit BchX2 as well as for subunit (BchYZ)2 (15). These results indicate that the catalytic mechanism of COR strongly resembles DPOR catalysis. In vitro assays for nitrogenase as well as for DPOR and COR make use of the artificial electron donor dithionite in the presence of high concentrations of ATP (7, 16, 17).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid sequence identities of the individual subunits of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase

Amino acid sequences of the individual subunits of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase employed in the present study (compareFig. 3A) were aligned by using the ClustalW method in MegAlign (DNASTAR), and sequence identities were calculated.

| DPOR |

COR |

Nitrogenase |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | B | L | Y | Z | X | NifD | NifK | NifH | |

| DPOR | |||||||||

| N | 37–58 | 15–18 | 12–20 | ||||||

| B | 34–62 | 15–22 | 14–18 | ||||||

| L | 51–69 | 31–35 | 31–38 | ||||||

| COR | |||||||||

| Y | 35–78 | 13–15 | |||||||

| Z | 39–81 | 11–16 | |||||||

| X | 42–83 | 29–36 | |||||||

| Nitrogenase | |||||||||

| NifD | 17–70 | ||||||||

| NifK | 37–58 | ||||||||

| NifH | 67–75 | ||||||||

In this study, we investigated the transient interaction of the dimeric subunit BchL2 or ChlL2 with the heterotetrameric (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 complex, which is essential for DPOR catalysis. We make use of the individually purified DPOR subunits BchL2 and (BchNB)2 from the green sulfur bacterium C. tepidum and ChlL2 and (ChlNB)2 from the prochlorophyte Prochlorococcus marinus and from the cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus. The individual combination of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 complexes and BchL2 or ChlL2 proteins from these organisms resulted in catalytically active chimeras of DPOR. These results enabled us to propose conserved regions of the postulated docking surface, which were subsequently verified in a mutagenesis study. To elucidate the potential evolution of the electron-transferring subunit of nitrogenase and nitrogenase-like enzymes, we also analyzed chimeric enzymes consisting of DPOR subunits (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 in combination with subunits BchX2 from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans of the COR enzyme and with subunit NifH2 of nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

Genes chlN and chlB from T. elongatus BP-1 were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using the primers TechlN_for and TechlN_rev for chlN and TechlB_for and TechlB_rev for chlB (primer sequences are given in supplemental Table S1). The Escherichia coli-specific ribosomal binding site was implemented upstream of chlB. PCR fragments for chlN were digested with BamHI/XhoI and for chlB with XhoI/NotI, respectively, and cloned into the BamHI-NotI site of pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare) to yield pGEX-TeNB. The chlL gene from T. elongatus was amplified using primers TechlL_for and TechlL_rev and cloned into the BamHI-XhoI sites of pGEX-6P-1 to generate pGEX-TeL. The construction of plasmids pGEX-PmNB carrying the genes chlN and chlB from P. marinus, pGEX-PmL with the gene chlL from P. marinus, pGEX-CtNBL encoding the genes bchN, bchB, and bchL from C. tepidum, and pGEX-CtL carrying the gene bchL from C. tepidum was described previously (3, 5). For the amplification of bchX encoding subunit BchX of COR from C. tepidum TLS primers CtbchX_for and CtbchX_rev were used. For bchX from R. denitrificans OCh 114 primers RdbchX_for and RdbchX_rev were employed. The resulting PCR fragments were digested with BamHI/SalI for bchX from C. tepidum and SacI/XhoI for bchX from R. denitrificans and cloned into the BamHI-SalI and SacI-XhoI sites of pET32a (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. The constructs thus obtained were designated pET-CtX and pET-RdX.

Mutagenesis of P. marinus DPOR

For the exchange of conserved amino acids in P. marinus DPOR subunits ChlN, ChlB, and ChlL, the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used. Amino acid substitutions in ChlN were introduced using primers E66A, L70R, L70D, V107D, and K109S. Oligonucleotides for the exchange of codons in ChlB were G66D, Q101G, and Q101D. For substitutions in ChlL the following primers were used: Y127S and Y127D.

Production and Purification of DPOR Subunits (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and BchL2 or ChlL2 in E. coli

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and BchL2 or ChlL2 were overproduced in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus® (DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene). The following plasmids encoding mentioned subunits were employed: pGEX-CtNB for C. tepidum (BchNB)2, pGEX-CtL for C. tepidum BchL2, pGEX-TeNB for T. elongatus (ChlNB)2, pGEX-TeL for T. elongatus ChlL2, pGEX-PmNB for P. marinus (ChlNB)2, and pGEX-PmL for P. marinus ChlL2. Cells were grown aerobically at 17 °C for the production of the C. tepidum and T. elongatus proteins or at 25 °C for the P. marinus proteins in LB medium containing 1 mm Fe(III) citrate. Protein production was induced with 50 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After cultivation for 16 h, cultures were supplemented with 1.7 mm dithionite and incubated for a further 2 h in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, MI) without agitation. All of the following procedures were performed under anaerobic conditions (95% N2, 5% H2, <1 ppm O2), and buffers were saturated with N2 prior to use. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in buffer A (100 mm HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm DTT), and disrupted by a single passage through a French Press® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 1000 p.s.i. into an anaerobic bottle. After ultracentrifugation for 1 h at 110,000 × g at 4 °C, the resulting supernatant was loaded onto glutathione-Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A. Recombinant fusion protein GST-BchN or GST-ChlN in complex with subunit BchB or ChlB or, alternatively, fusion protein GST-BchL or GST-ChlL alone, was eluted with buffer A containing 15 mm glutathione. GST was cleaved off the target proteins by incubation with 2 units of PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare) for 16 h.

For subsequent label transfer experiments, affinity-purified proteins (ChlNB)2 and ChlL2 from P. marinus were further purified by gel permeation chromatography under anaerobic conditions. Therefore, protein samples (∼1.5 ml) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml were subjected to a preparative gel permeation chromatography on a Superdex 200 26/60 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 100 mm HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2 (buffer B) at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. Elution fractions were pooled and concentrated by using a Microcon® centrifugal filter unit (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany; molecular weight cutoff 10,000).

Production and Purification of COR Subunit BchX2 in E. coli

His-tagged COR BchX2 subunits were produced in E. coli BL21 (DE3)-RIL (Stratagene) carrying plasmids pET-CtX encoding C. tepidum BchX2 and pET-RdX encoding R. denitrificans BchX2. Cells were grown aerobically at 17 °C in LB medium containing 1 mm Fe(III)-citrate. Recombinant protein production was induced by addition of 50 μm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After further cultivation for 16 h, cultures were incubated for 2 h in an anaerobic chamber. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in buffer B, and disrupted by a single passage through a French press (SLM-Aminco) at 1000 p.s.i. under anaerobic conditions. After ultracentrifugation for 1 h at 110,000 × g at 4 °C, the resulting supernatant was applied onto a nickel-loaded chelating Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer B. After extensive washing with buffer C (100 mm HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2), proteins were eluted with buffer C containing 200 mm imidazole. The His tag was removed from the target protein by incubation with 2 units of thrombin (Novagen) for 16 h.

Determination of Native Molecular Mass

Analytical gel permeation chromatography was performed using a Superdex 200 HR 26/60 column (GE Healthcare) under anaerobic conditions. After calibration of the column with marker proteins (molecular weight marker kit, Sigma-Aldrich) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, 250-μl samples (∼3–5 mg/ml) of T. elongatus (ChlNB)2 and C. tepidum BchX2 were run under identical conditions. Protein elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm.

Determination of Protein Concentration

The concentration of purified (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 proteins was determined using the Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions with bovine serum albumin as a standard. For the quantification of GST fusion proteins with subunits BchL2 or ChlL2 in cell-free extracts of E. coli, a GST detection module (GE Healthcare) was used. Alternatively, protein concentration was determined densitometrically using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

UV-visible Light Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-visible light spectra of recombinantly purified (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and BchX2 proteins were recorded under anaerobic conditions using a V-550 spectrophotometer (Jasco, Gross-Umstadt, Germany).

Determination of Iron Content

The iron content of purified (ChlNB)2 and BchX2 proteins was measured colorimetrically with bathophenantroline following acid denaturation as described previously (18).

Label Transfer Experiments

Purified ChlL2 protein from P. marinus after preparative gel permeation chromatography was labeled with the trifunctional label transfer reagent Mts-Atf-LC-biotin (Pierce). In addition to a biotin moiety, this reagent contains a sulfhydryl-specific methane thiosulfonate (Mts) group, which can form disulfide bonds with free sulfhydryl groups of the ChlL2 protein. After exposure to UV light, the photoreactive tetrafluorophenyl azide (Atf) moiety of the cross-linker inserts into carbon hydrogen bonds and unsaturated carbon chains of the protein within a distance of 21.8 Å. Upon the addition of reducing agents, the disulfide bond is cleaved and the biotin label is transferred to the interacting protein partner.

All procedures for the labeling experiments were performed with low levels of reductant (<1 mm DTT) and under subdued light to prevent premature loss of the label and activation of the Atf moiety. Purified ChlL2 from P. marinus was mixed with a 5-fold molar excess of Mts-Atf-LC-biotin in a total reaction volume of 500 μl in phosphate-buffered saline (100 mm sodium phosphate, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4). After incubation for 1 h at 21 °C, the unbound reagent was removed by dialysis using Slide-A-Lyzer® MINI dialysis units (Pierce). Label transfer experiments contained 25 μm (ChlNB)2 from P. marinus and the corresponding biotinylated ChlL2 protein (ChlL2-Mts-Atf-LC-biotin; 70 μm) in a volume of 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. Assays also contained 2 mm ATP, an ATP-regenerating system consisting of 20 mm creatine phosphate and 10 units of creatine phosphokinase, and the DPOR substrate Pchlide at a concentration of 13 μm. Complex formation was initiated for 5 min at 21 °C. Then the cross-linking reaction was induced by exposure to UV light using a CAMAG UV lamp (365 nm; 2 × 8 watts) for 30 min at a distance of 5 cm. 100 μl of SDS sample buffer (19) containing the reducing agent DTT at a concentration of 100 mm was added. Thereby, the ChlL2 protein was liberated from the cross-linked complex, resulting in the transfer of the biotin label onto the (ChlNB)2 protein. In control experiments the (ChlNB)2 complex or the ChlL2 protein was omitted. Furthermore, negative controls were performed by substituting (ChlNB)2 with bovine serum albumin. All samples were subsequently analyzed via 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a Trans-Blot apparatus semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer's instructions. Biotin-labeled proteins were detected by using a NeutrAvidin antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Pierce).

Determination of DPOR Activity

Functional DPOR enzymes from C. tepidum, P. marinus, and T. elongatus were reconstituted by supplementing 100 pmol of purified (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 with 200 pmol of purified BchL2 or ChlL2, respectively, in a total volume of 125 μl in 100 mm HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 10 mm MgCl2. The assays contained 2 mm ATP, an ATP-regenerating system consisting of 20 mm creatine phosphate and 10 units of creatine phosphokinase, 10 mm DTT, 10 mm sodium dithionite as an electron donor, and the substrate Pchlide at 13 μm. Pchlide was isolated from the bchL-deficient Rhodobacter capsulatus mutant strain ZY5 as described previously (3, 17). Samples were incubated under strict anaerobic conditions for 15 to 60 min in the dark at varying temperatures ranging from 20 to 50 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 500 μl of acetone. After centrifugation for 30 min at 12,000 × g, the supernatant was analyzed by UV-visible spectroscopy using a V-550 spectrophotometer (Jasco). The DPOR reaction product, Chlide, shows a characteristic peak at 665 nm, whereas the substrate possesses an absorption maximum at 626 nm. For the quantification of Pchlide and Chlide, extinction coefficients of ϵ626 = 30.4 mm−1 cm−1 for Pchlide and ϵ665 = 74.9 mm−1 cm−1 for Chlide were used (17, 20). The detection limit of the assay is at 15.75 nmol min−1 mg−1.

All subsequent assays for the various DPOR systems were standardized at 35 °C allowing for the determination of specific activities under identical conditions. For this standard DPOR assay, 100 pmol of purified (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 was combined with 1–80 μl of a cell-free E. coli extract containing 0.05–300 pmol of the overproduced BchL2 or ChlL2 protein, respectively. The specific activities obtained were set as 100%, and all other values (values of chimeric DPOR enzymes and mutant DPOR enzymes) were related to this. In all cases, assays were completed by control experiments in which the BchL2 or ChlL2 protein, the (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 complex, or alternatively the co-substrate ATP was omitted.

Determination of DPOR Activity for Chimeric Enzymes consisting of (BchNB) 2 or (ChlNB) 2 and BchX2

The DPOR subcomplex (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum or (ChlNB)2 from P. marinus and T. elongatus was combined with protein subunit BchX2 of the COR enzyme from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans. For this type of experiments the standard DPOR assay contained concentrations of 10–300 pmol of the BchX2 protein instead of BchL2 or ChlL2 protein. Control experiments were performed in the absence of the BchX2 subunit and in the absence of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2, respectively.

Determination of DPOR Activity for Chimeric Enzymes consisting of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and NifH2

Nitrogenase Fe protein NifH2 from A. vinelandii was purified as described elsewhere (21, 22). For chimeric enzyme activities, the standard DPOR assay containing 100 pmol (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum or (ChlNB)2 from P. marinus or T. elongatus, respectively, was supplemented with purified NifH2 at concentrations ranging from 100 to 2000 pmol.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale of the Experimental Approach

The electron-transferring subunits of the nitrogenase-like enzymes DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase show significant amino acid sequence identity. To gain insight into the evolution of these three subunit enzymes, we investigated the functional interaction of the electron-transferring subunits BchL2 or ChlL2 from various DPOR enzymes, BchX2 from various COR enzymes, and NifH2 of nitrogenase from A. vinelandii with different DPOR (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 subunits. First, for this purpose these proteins were recombinantly produced and biochemically characterized. Then various combinations of chimeric enzymes were generated and functionally characterized.

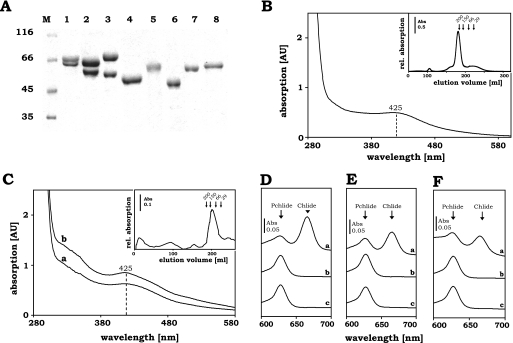

Production and Purification of DPOR Subunits (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and BchL2 or ChlL2 from C. tepidum, P. marinus, and T. elongatus

In our previous studies we have presented a detailed biochemical characterization of DPOR protein subunits (BchNB)2 and BchL2 from the green sulfur bacterium C. tepidum and (ChlNB)2 and ChlL2 from the prochlorophyte P. marinus (3, 5). In the present study we extended our repertoire to the heterologous production and subsequent purification of the individual DPOR subunits from the thermophilic cyanobacterium T. elongatus. The corresponding genes chlN, chlB, and chlL were cloned into standard E. coli expression vectors to yield plasmids pGEX-TeNB and pGEX-TeL. Both constructs allowed for the anaerobic purification of subunits ChlN and ChlL via their GST tags. Stoichiometric amounts of subunit ChlB were co-purified with GST-ChlN (Fig. 2A, lane 3). The identity of both proteins was confirmed by Edman degradation. A molar ratio of ∼1.1/1 was measured for GST-ChlN/ChlB. The subsequent gel permeation chromatography after protease cleavage revealed a relative molecular mass of 210,000 indicating a tetrameric (ChlNB)2 complex (ChlN = 51,508 Da, ChlB = 56,317 Da) (Fig. 2B, inset). Concentrated fractions of (ChlNB)2 from T. elongatus were brownish in color and revealed an absorption maximum at 425 nm characteristic for [4Fe-4S] clusters (Fig. 2B). The determination of the iron content revealed 7.6 mol of iron/mol of (ChlNB)2 tetramer, which is in good agreement with 2 [4Fe-4S] clusters located on the (ChlNB)2 tetramer. For the purification of the T. elongatus ChlL2 protein an analogous production and purification scheme was employed (Fig. 2A, lane 6). Results obtained for DPOR from T. elongatus did not show any differences with respect to oligomeric structure and [Fe-S] cluster composition when compared with the previously characterized enzymes from C. tepidum (3), P. marinus (5), and R. capsulatus (17), respectively. The purification of the DPOR subunits employed is summarized in Fig. 2A, which shows the apparently pure (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 proteins from C. tepidum (lane 1) (GST-BchN = 73.5 kDa, BchB = 58.9 kDa), from P. marinus (lane 2) (GST-ChlN = 73 kDa, ChlB = 58.7 kDa), and from T. elongatus (lane 3) (GST-ChlN = 78.4 kDa, ChlB = 56.3 kDa). Purified GST-BchL2 or GST-ChlL2 proteins from C. tepidum (GST-BchL = 56.3 kDa), P. marinus (GST-ChlL = 59.2 kDa), and T. elongatus (GST-ChlL = 58 kDa) are presented in Fig. 2A, lanes 4–6. The integrity of all proteins was verified by N-terminal sequencing and mass spectrometry (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Purification and characterization of recombinant DPOR and COR subunits from different bacteria and their catalytic activities in various combinations. A, SDS-PAGE analysis of purified (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2, BchL2 or ChlL2, and BchX2 proteins. Indicated proteins were produced recombinantly in E. coli, purified chromatographically, separated through 12% SDS-PAGE, and visualized via Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Lane M, molecular mass marker; relative molecular masses (×1000) are indicated. Lane 1, purified C. tepidum GST-BchN complexed with subunit BchB; lane 2, purified P. marinus GST-ChlN complexed with subunit ChlB; lane 3, purified T. elongatus GST-ChlN complexed with subunit ChlB; lane 4, purified C. tepidum GST-BchL protein; lane 5, purified P. marinus GST-ChlL protein; lane 6, purified T. elongatus GST-ChlL protein; lane 7, purified C. tepidum Trx/His/S-BchX protein; lane 8, purified R. denitrificans Trx/His/S-BchX protein. B, UV-visible absorption spectra of the purified T. elongatus (ChlNB)2 complex. The spectra were recorded under anaerobic conditions at a protein concentration of 20 μm. It exhibits a significant absorption maximum at 425 nm. Inset, analytical gel permeation chromatography analysis of T. elongatus (ChlNB)2. The purified (ChlNB)2 complex (23 μm), after protease cleavage, was analyzed on a Superdex 200 HR 26/60 gel permeation column under strict anaerobic conditions at a flow rate of 1 ml/min by monitoring the absorbance at 280 nm. C, UV-visible absorption spectra of recombinant purified BchX2 proteins from C. tepidum (trace a) and R. denitrificans (trace b). Spectra were recorded under anaerobic conditions with a protein concentration of 150 μm. A significant absorption maximum at 425 nm is observed. Inset, analytical gel permeation chromatography of C. tepidum BchX2. Purified BchX2 following thrombin cleavage (35 μm) was analyzed on a Superdex 200 HR 26/60 gel permeation column under anaerobic conditions at a flow rate of 1 ml/min by monitoring the absorbance at 280 nm. D–F, UV-visible absorption spectra for the standard DPOR assay. Assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After the assay was incubated for 1 h at 35 °C, pigments were extracted with acetone. Absorption maxima of the DPOR substrate Pchlide and the product Chlide are indicated by arrows. D, activity of a homologous DPOR system. Trace a, DPOR assay containing 100 pmol of purified P. marinus (ChlNB)2 and 150 pmol of P. marinus ChlL2 protein; traces b and c, negative control without (ChlNB)2 (b) and without ChlL2 protein (c). E, activity of a heterologous DPOR system. Trace a, DPOR assay containing purified T. elongatus (ChlNB)2 and 50 pmol of P. marinus ChlL2; traces b and c, negative control without (ChlNB)2 (b) and without ChlL2 (c) protein. F, chimeric activity of DPOR and COR. Trace a, DPOR assay containing 100 pmol of purified C. tepidum (BchNB)2 and 17 pmol of C. tepidum BchX2 protein; traces b and c, negative control without (BchNB)2 (b) and without BchX2 (c) protein.

Specific Activity of DPOR Enzymes under Standardized Conditions

The specific activity of homologous DPOR enzymes from C. tepidum, P. marinus, and T. elongatus was analyzed under identical assay conditions at pH 7.5 in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system, 2 mm ATP, 10 mm dithionite, and 150 mm NaCl at a temperature of 35 °C. An assay temperature of 35 °C was mandatory because the activity of the DPOR enzyme from T. elongatus decreased significantly when temperatures lower than 32 °C were used (data not shown). This DPOR standard assay ensures enzymatic activity despite the fact that optimal growth temperatures for C. tepidum (48 °C), P. marinus (24 °C), and T. elongatus (55 °C) diverge significantly (23–25). In Fig. 2D a typical DPOR standard assay for P. marinus is shown. Control experiments without (ChlNB)2 (Fig. 2D, trace b) or without ChlL2 protein (Fig. 2D, trace c) show only the substrate Pchlide with an absorption maximum at 626 nm. Similarly, without the addition of ATP, no product formation was detectable (data not shown). However, incubation of P. marinus (ChlNB)2 with ChlL2 resulted in the formation of high amounts of Chlide with an absorption maximum at 665 nm (Fig. 2D, trace a). Under the conditions employed, a specific DPOR activity of 163 pmol min−1 mg−1, 847 pmol min−1 mg−1, and 107 pmol min−1 mg−1 was obtained for the enzymes from C. tepidum, P. marinus, and T. elongatus, respectively.

Chimeric DPOR Enzymes Are Active

Six chimeric DPOR enzymes, consisting of individual subunits from C. tepidum, P. marinus, and T. elongatus, were reconstituted under the conditions of the DPOR standard assay. For this type of analysis the relative activities of the homologous enzymes were set as 100%, and all other values were related to that number. The ratio of BchL2 (or ChlL2) and (BchNB)2 (or (ChlNB)2) was optimized by altering the amount of BchL2 or ChlL2 from 0.05 to 200 pmol with a constant amount of 100 pmol of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2. In Fig. 2E an assay for a chimeric DPOR consisting of T. elongatus (ChlNB)2 in combination with P. marinus ChlL2 is shown. After incubation of both subunits, product formation was clearly detectable (Fig. 2E, trace a), whereas in assays without the addition of ChlL2 (Fig. 2E, trace b) or (ChlNB)2 (Fig. 2E, trace c) no Chlide formation was observed. The activities of the various chimeric DPOR enzymes are summarized in Table 2. Interestingly, for five of six possible combinations, DPOR activities were observed. The combination of P. marinus ChlL2 with (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum or (ChlNB)2 from T. elongatus even resulted in levels comparable to the wild-type DPOR from P. marinus. The DPOR system composed of C. tepidum BchL2 and P. marinus (ChlNB)2 showed a residual enzyme activity of 3% when compared with wild-type P. marinus DPOR. Only the enzymatic activity of T. elongatus ChlL2 in combination with P. marinus (ChlNB)2 was below the detection limit of the assay employed (<1%). The varying temperature optima of the employed DPOR subunits might be responsible for these low activities. Similar experiments have also been described for nitrogenase systems from different organisms. In in vitro assays significant activity for chimeric nitrogenase enzymes has been obtained (26–33). From the observed activities of the various chimeric DPOR enzymes, we concluded that the docking surface responsible for protein-protein interaction and the subsequent electron transfer have been conserved during the evolution of the various DPOR enzymes.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic activities of heterologous DPOR systems and chimeric activity of DPOR subunit (BchNB)2or (ChlNB)2with subunit NifH2of nitrogenase and subunit BchX2of COR

Standard DPOR assays were performed for 1 h at 35 °C as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The relative enzymatic activity of the corresponding wild-type DPOR was set as 100%, and all other values were related to this value.

| C. tepidumBchL2 | T. elongatusChlL2 | P. marinusChlL2 | C. tepidumBchX2 | R. denitrificansBchX2 | A. vinelandiiNifH2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| C. tepidumBchNB2 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 90 | 50 | <1 |

| T. elongatusChlNB2 | 50 | 100 | 100 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| P. marinusChlNB2 | 3 | <1 | 100 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

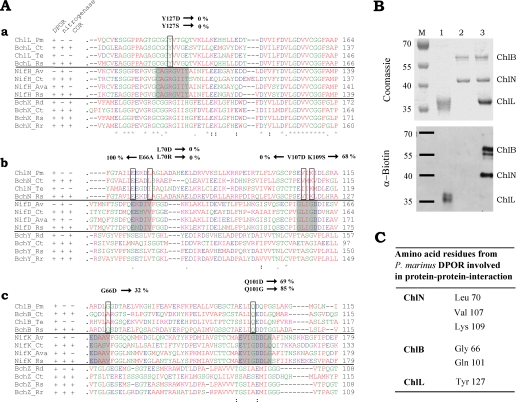

DPOR Subunits ChlN and ChlB Both Interact with Subunit ChlL

To elucidate the protein-protein interaction of ChlL2 with (ChlNB)2 from P. marinus in further detail, we performed label transfer experiments under anaerobic conditions. For this purpose, the trifunctional cross-linker Mts-Atf-LC-biotin was coupled chemically to purified ChlL2 protein from P. marinus (Fig. 3B, lane 1). This labeled ChlL2 protein was incubated with the corresponding (ChlNB)2 complex, and cross-linking of both protein subcomplexes was initiated by UV radiation. In a subsequent reduction step, the covalent cross-linking was opened, resulting in the transfer of the attached biotin label onto components of the (ChlNB)2 complex. The transfer of the biotin label was visualized by Western blot analysis using a horseradish peroxidase-NeutrAvidin conjugate. As seen in Fig. 3B, lane 3, efficient label transfer to the ChlN as well as to the ChlB subunit was obtained. From these results we concluded that upon ChlL2/(ChlNB)2 interaction, amino acid residues of both the ChlN and ChlB proteins are located in the operating range (21.8 Å) of the label transfer reagent localized on the ChlL subunit. Hence, both subunits, ChlN and ChlB, are involved in the protein-protein interaction with subunit ChlL2.

FIGURE 3.

Alignments of DPOR subunits BchL (or ChlL), BchN (or ChlN), and BchB (or ChlB) with the corresponding subunits of nitrogenase and COR. DPOR activity of various DPOR subunit mutants are shown. Label transfer experiments used P. marinus DPOR and amino acids involved in protein-protein interaction. A, amino acid sequence alignments of DPOR subunits from P. marinus (Pm), C. tepidum (Ct), T. elongatus (Te), and R. sphaeroides (Rs) with the corresponding nitrogenase subunits from A. vinelandii (Av), C. tepidum, Anabaena variabilis (Ava), and R. sphaeroides and with the corresponding COR subunits from R. denitrificans (Rd), C. tepidum, R. sphaeroides, and Rhodospirillum rubrum (Rr). Complete sequence alignments can be found in supplemental Figures S2–S4. For the individual species employed in the sequence alignment, the presence (+) or absence (−) of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase is indicated. Sequence motifs responsible for the dynamic protein-protein interaction of nitrogenase are highlighted in gray. Residues that are identical among the subunits of all three enzymes are indicated by an asterisk, conserved substitutions by a colon, and semiconserved substitutions by a period. The positions of DPOR amino acids mutagenized in the present study are indicated by boxes, and the activities of the respective mutant proteins are indicated. a, alignment of BchL or ChlL proteins of DPOR with NifH of nitrogenase and subunit BchX of COR; b, alignment of BchN or ChlN proteins of DPOR with NifD of nitrogenase and subunit BchY of COR; c, alignment of BchB or ChlB proteins of DPOR with NifK of nitrogenase and subunit BchZ of COR. B, label transfer from subunit ChlL2 from P. marinus to the corresponding (ChlNB)2 complex from P. marinus. ChlL2 was labeled as described under “Experimental Procedures” and incubated with 25 μm (ChlNB)2 followed by exposure to UV light to initiate cross-linking. Subsequent reduction enabled the transfer of the biotin label onto subunits ChlN and ChlB. Top panel, SDS-PAGE after cross-linking and label transfer stained with Coomassie Blue. Bottom panel, immunoblot of identical samples analyzed with a NeutrAvidin antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. Lane M, molecular mass marker; relative molecular masses (×1000) are indicated. Lane 1,ChlL2 after labeling; lane 2, (ChlNB)2 without the addition of labeled protein ChlL2; lane 3, label transfer onto (ChlNB)2 after incubation of (ChlNB)2 complex with labeled ChlL2 protein (observed bands correspond to protein ChlN and ChlB carrying the transferred biotin-label (bottom panel)). C, amino acids of subunits ChlN, ChlB, and ChlL of P. marinus DPOR involved in the docking surface of (ChlNB)2 and ChlL2 are summarized.

Next, we tried to identify highly conserved regions of the ChlN, ChlB, and ChlL subunits located on the protein surface. The amino acid residues responsible for the dynamic interaction of the nitrogenase subunits (Fig. 3A, highlighted in gray) have been studied in great detail based on the crystal structure of various ternary complexes of nitrogenase (8, 12, 34–39). In Fig. 3A conserved amino acid sequences of the individual DPOR subunits with the related subunits of nitrogenase were identified using a sequence alignment. Based on the outlined sequence alignments, 10 amino acid residues of the individual subunits of P. marinus DPOR were exchanged (Fig. 3A, indicated by boxes). A kinetic analysis of purified recombinant mutant DPOR proteins followed.

Mutant Proteins of DPOR Subunit ChlL

Only recently the structure of the BchL protein of DPOR from Rhodobacter sphaeroides was solved (14). In this study (14), amino acid sequence alignments in combination with structural comparisons revealed that only two residues involved in nitrogenase complex formation are also conserved on subunit BchL. However, residues Tyr129, Gln133, Gln168, and His169 of DPOR subunit BchL (R. sphaeroides numbering) have been found to substitute for residues Arg100, Thr104, Arg140, and Glu141 (A. vinelandii numbering) at the docking face of NifH2. Because of the differing chemical properties of these amino acid residues, it was concluded that the docking faces of DPOR and nitrogenase differ significantly, mainly due to an altered charge distribution (14).

To determine DPOR-specific amino acid residues involved in protein-protein interaction, the conserved docking face of DPOR subunit ChlL2 was analyzed for appropriate candidates. Based on the amino acid sequence alignment shown in Fig. 3A, panel a, and the structural analysis of the BchL protein from R. sphaeroides, residue Tyr127 (representing Tyr129 in R. sphaeroides) was altered into a smaller residue carrying a net negative charge (Y127D) or into a distinctively smaller polar residue (Y127S). Tyr127 is found conserved in all BchL and ChlL proteins, whereas the nitrogenase system as well as the COR system makes use of an arginine at the identical position. Neither of the mutant ChlL proteins, Y127D and Y127S, sustained detectable DPOR activity. From these data, in combination with the results of the previously described three-dimensional structure of the BchL protein, we concluded that Tyr127 is essential for DPOR catalysis. This surface-exposed residue might be directly involved in protein-protein interaction and/or may be responsible for the intersubunit electron transfer.

Mutant Proteins of DPOR Subunit ChlN

Highly conserved DPOR regions, presumably located on the protein surface of the ChlN and ChlB subunits, were predicted by amino acid sequence alignments and analysis of the surface probability in combination with secondary structure predictions (40). These analyses were hampered because the orthologous nitrogenase subunits NifD and NifK share an overall sequence identity of only ∼15%.

Nevertheless, the amino acid sequence alignment shown in Fig. 3A, panel b, places the conserved surface exposed amino acid sequence EEXD(L/I)(A/S)X of DPOR subunit BchN (or ChlN) (residues 66–72 in P. marinus) alongside the sequence motif EX(D/H)(I/V)VFG (residues 120–124 in A. vinelandii) of nitrogenase, which is known to be involved in NifH2/(NifD/NifK)2 interaction (highlighted in gray in Fig. 3A). From this consideration, we deduced that Glu66 as well as Leu70 might be involved in DPOR protein-protein interaction. However, full DPOR activity was obtained for the mutant DPOR ChlN protein E66A from P. marinus. In contrast, the DPOR subunit ChlN mutant L70D as well as mutant L70R failed to sustain detectable DPOR activity. These data indicate that the highly conserved residue Glu66 is not essential for DPOR activity. However, mutation of Leu70 into the negatively charged residue Asp, as well as into the positively charged residue Arg, completely abolished DPOR activity.

A second conserved surface-exposed loop region of NifD, composed of GLIGDD (residues 157–162), aligns with the conserved sequence motif E(V/I)(I/M)KXD of residues 106–111 in P. marinus DPOR subunit ChlN. DPOR mutant protein V107D did not show any detectable activity. Mutant K109S revealed a significantly decreased DPOR activity of 68% when compared with the wild-type P. marinus enzyme. The results of these conservative alterations indicate that both residues play an important role in DPOR catalysis. With respect to the postulated surface-exposed nature of the two identified loop regions, we propose that residues Leu70, Val107, and Lys109 might be located at the docking surface. This might also include a direct involvement in the catalyzed electron transfer process.

Mutant Proteins of DPOR Subunit ChlB

Amino acid sequence alignments of DPOR subunit ChlB with the corresponding NifK protein revealed that the conserved loop regions located at the nitrogenase docking surface do not have clearly defined counterparts in subunit BchB (or ChlB) of DPOR (compare Fig. 3A, panel c). Nevertheless, the amino acid sequence L(G/A)XX(T/S) of P. marinus DPOR ChlB (residues 65–70) might be involved in the dynamic interaction of DPOR. In our mutant enzyme study the DPOR subunit ChlB variant G66D revealed a residual activity of only 32% when compared with the wild-type enzyme. This result indicates that Gly66 is important for DPOR catalysis. As bioinformatic analysis indicated a high surface probability for Gly66, one might conclude that a steric effect, or alternatively an electrostatic repulsion of the interacting ChlL2 subunit, is responsible for the observed reduction of DPOR activity. The results obtained are in agreement with a model in which Gly66 is part of the docking surface of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2.

A second loop region, IQ(D/E)(Q/D) (residues 100–104), of subunit ChlB of P. marinus DPOR was aligned with a region of the corresponding nitrogenase NifK protein consisting of a highly conserved sequence signature, IGDDL (residues 160–164 in A. vinelandii). Because only Gln101 was found to be conserved in all of the DPOR BchB (or ChlB) proteins analyzed, we decided to alter this residue into a charged residue of a smaller size (Q101D). Moreover, Gln101 was changed into a glycine residue (Q101G). The DPOR ChlB mutant Q101D showed a reduced activity of 69% compared with wild-type DPOR. For this mutation toward a smaller aspartate residue, a steric effect was excluded; however, repulsion of the carboxylate group might result in the observed reduced activity. The second mutation was of special interest, because the Gln101 was found to align with the highly conserved Gly159 in the sequence of NifK from A. vinelandii. Interestingly, in mutant Q101G DPOR activity was partly restored as indicated by a relative activity of 85% when compared with mutant Q101D. Mutant protein Q101G now shares the specific sequence signature IGD, which is highly conserved among all nitrogenase sequences. This finding might reflect a common evolutionary origin of DPOR and nitrogenase enzymes because a glycine at position 101 is a good substitute for Gln101. Based on these findings, we concluded that residue Gln101 might be involved in DPOR protein-protein interaction analogous to the nitrogenase system.

Postulated Docking Surface of DPOR

Fig. 3C summarizes the amino acid residues that have been postulated to be involved in protein-protein interaction of ChlL2 with the (ChlNB)2 complex. The aforementioned residues have a significantly different chemical character when compared with the theoretically related residues of nitrogenase. Therefore, a docking face with a distinctively varying distribution of charge was postulated. These findings are in good agreement with the results of the recently published structure of the BchL2 protein from R. sphaeroides (14).

Chimeric Enzymes Consisting of the DPOR (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 Complex and the NifH2 Protein from A. vinelandii Are Inactive

In a recently published in vitro study, it was shown that the BchL2 protein from R. sphaeroides is not able to serve as an electron donor for the MoFe protein from A. vinelandii (14). In the present investigation we made use of an inverse cross experiment. Under the conditions of the standard DPOR assay, the BchL2 protein from C. tepidum and the ChlL2 protein from P. marinus and T. elongatus were substituted by varying concentrations of NifH2 from A. vinelandii, respectively. Under all of the conditions employed, no Chlide formation was detectable (data not shown). This experiment indicated that the docking surface of DPOR and nitrogenase have evolved significantly during evolution. These results are in good agreement with our sequence alignments (Fig. 3A) and the analysis of the three-dimensional structure of the BchL2 protein from R. sphaeroides (14).

Production and Purification of Subunit BchX2 of COR Enzymes from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans

For the replacement of the electron-transferring subunit BchL2 or ChlL2 of DPOR with subunit BchX2 of the COR enzyme, BchX2 proteins from different bacterial species were produced heterologously in E. coli. The corresponding bchX genes from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans were cloned into E. coli expression vectors encoding a fusion protein carrying an N-terminal thioredoxin/His/S tag. Both tagged proteins were purified anaerobically according to the manufacturer's instructions. Eluted BchX2 proteins (Fig. 2A, lanes 7 and 8) revealed an absorption peak at 425 nm characteristic of a [4Fe-4S] cluster (Fig. 2C, traces a and b). The determination of the iron content yielded 2.7 mol of iron/mol of BchX2 from C. tepidum and 3.4 mol of iron/mol of BchX2 from R. denitrificans. For the determination of the native molecular mass, BchX protein from C. tepidum was liberated from the nickel-chelating column by thrombin cleavage. The profile of the subsequent analytical gel permeation chromatography revealed a native molecular weight of 95,000 for BchX2 (BchX = 46,000 kDa) from C. tepidum (Fig. 2C, inset). This is the first experimental evidence for the dimeric nature of COR subunit BchX. From these results we concluded that BchX2 proteins from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans carry a [4Fe-4S] cluster. Because Cys124 and Cys158 (P. marinus numbering) are found conserved in all sequences of BchX and BchL (or ChlL) proteins (compare Fig. 3A), we concluded that the COR subunit BchX2 forms a redox-active intersubunit cluster analogous to that described for DPOR subunits BchL2 or ChlL2.

These results indicate that BchX2 is an appropriate candidate to study potential chimeric enzyme consisting of DPOR subunit (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and COR subunit BchX2.

Chimeric Enzymes Consisting of the DPOR (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 Complex and the BchX2 Protein of COR Are Active

In a standard DPOR assay with (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum and (ChlNB)2 from T. elongatus and P. marinus, subunit BchL2 (or ChlL2) was substituted with the BchX2 subunit of COR from C. tepidum and R. denitrificans. Pchlide was used as a substrate at a concentration of 13 μm in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system, 2 mm ATP, with 10 mm dithionite as the reducing agent. For those experiments 100 pmol of (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 was supplemented with varying amounts of BchX2 (10–300 pmol). In control experiments without BchX2, (BchNB)2, or (ChlNB)2, no product formation was observed, as can be seen in the absorption spectra shown in Fig. 2F, traces b and c. Furthermore, control experiments without the addition of ATP showed no Chlide formation (data not shown). However, in a standard assay containing 100 pmol of (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum and 17 pmol of BchX2 from C. tepidum, a chimeric DPOR activity of 90% was observed when compared with the activity of the wild-type system (Fig. 2F, trace a). When (BchNB)2 from C. tepidum was supplemented with 20 pmol of BchX2 from R. denitrificans, significant DPOR activity of 50% was also observed (Table 2).

The BchX subunits employed share an overall sequence identity of 31–35% when compared with the amino acid sequence of BchL or ChlL proteins. However, identical values were obtained when subunit BchX2 was compared with NifH2 protein (Table 1), which failed to sustain DPOR activity. Furthermore, visual inspection of sequence alignments of BchX, BchL (or ChlL), and NifH proteins (compare Fig. 3A) did not reveal any regions sharing a higher degree of sequence conservation for the BchX/BchL (or BchX/ChlL) couple compared with the BchX/NifH couple. This clearly becomes evident for the postulated docking region including Tyr127 in the sequence of subunit BchL or ChlL. At this position BchX and NifH proteins carry a highly conserved arginine residue, whereas a conserved tyrosine residue is found in all BchL or ChlL sequences. The observed chimeric activity of subunit BchX2 of COR with subunit (BchNB)2 of DPOR indicates that protein-protein interaction and intersubunit electron transfer is not dependent on highly conserved sequence motifs. Conservative mutations of amino acid residues located at the postulated docking face of BchX2 still allow for the obtained chimeric activity.

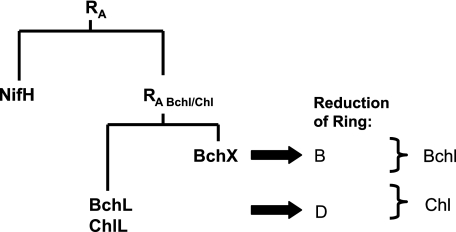

Evolution of subunits NifH2, BchL2 or ChlL2 and BchX2

Subunits NifH2, BchL2, or ChlL2 and BchX2 are responsible for the ATP-dependent transfer of electrons onto the corresponding subunits (NifD/NifK)2, (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 and (BchYZ)2. These heterotetrameric protein complexes are then responsible for accurate substrate recognition and reduction. The absence of activity of DPOR subunit (BchNB)2 or (ChlNB)2 with subunit NifH2 of nitrogenase suggests that subunits NifH2 and BchL2 (or ChlL2) have evolved significantly. In contrast, the chimeric activity of the DPOR subunit (BchNB)2 in combination with subunit BchX2 of COR suggests that the BchX2 protein has evolved only sparingly from a common ancestor. Although highly conservative sequence mutations were introduced, the mode of protein-protein interaction was preserved. In Fig. 4 a hypothetical model for the evolution of the electron-transferring subunits is shown. Gene duplication of an ancient reductase (RA) gave rise to a nitrogenase (NifH) and a Bchl/Chl branch. This ancient reductase (RA Chl/Bchl) of the Bchl/Chl path has thus evolved into the current BchX2 and BchL2 (or ChlL2) proteins. This evolutionary process came along with the appearance of subunits (BchNB)2 (or (ChlNB)2) and (BchYZ)2 responsible for the specific reduction of rings B and D, respectively. Taking into account these evolutionary considerations, it would be interesting to elucidate the specificity of the ancient enzymatic system involved in Bchl/Chl synthesis.

FIGURE 4.

Hypothetical model for the evolution of electron-transferring subunits of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase. An ancient reductase, RA, gave rise to the nitrogenase branch (NifH) and a Chl/Bchl biosynthetic branch (BchX and BchL or ChlL). Current BchX2 proteins of COR and BchL2 (or ChlL2) proteins of DPOR have evolved from the ancient reductase, RA Chl/Bchl.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Carl E. Bauer for providing R. capsulatus strain ZY5. We also thank Kalle Möbius, Stefanie Klein, and Rebekka Biedendieck for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forsch ungs ge mein schaft.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figures 2–4.

- Chl

- chlorophyll

- Atf

- tetrafluorophenyl azide

- Bchl

- bacteriochlorophyll

- Bchlide

- bacteriochlorophyllide

- Chlide

- chlorophyllide

- COR

- chlorophyllide oxidoreductase

- DPOR

- dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- Mts

- methanethiosulfonate

- Mts-Atf-LC-biotin

- 2-{N2-[N6-(4-azido-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzoyl-6-aminocaproyl)-N6-(6- biotinamidocaproyl)-l-lysin-ylamido]}ethyl methanethiosulfonate

- Pchlide

- protochlorophyllide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke D. H., Hearst J. E., Sidow A. ( 1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 7134– 7138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rees D. C., Tezcan F. A., Haynes C. A., Walton M. Y., Andrade S., Einsle O., Howard J. B. ( 2005) Philos. Transact. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 363, 971– 984,, 1035– 1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bröcker M. J., Virus S., Ganskow S., Heathcote P., Heinz D. W., Schubert W. D., Jahn D., Moser J. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10559– 10567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke D. H., Alberti M., Hearst J. E. ( 1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 2407– 2413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bröcker M. J., Wätzlich D., Uliczka F., Virus S., Saggu M., Lendzian F., Scheer H., Rüdiger W., Moser J., Jahn D. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29873– 29881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujita Y., Matsumoto H., Takahashi Y., Matsubara H. ( 1993) Plant Cell Physiol. 34, 305– 314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomata J., Mizoguchi T., Tamiaki H., Fujita Y. ( 2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15021– 15028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tezcan F. A., Kaiser J. T., Mustafi D., Walton M. Y., Howard J. B., Rees D. C. ( 2005) Science 309, 1377– 1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters J. W., Fisher K., Dean D. R. ( 1995) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49, 335– 366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean D. R., Bolin J. T., Zheng L. ( 1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 6737– 6744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki J. Y., Bollivar D. W., Bauer C. E. ( 1997) Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 61– 89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindelin H., Kisker C., Schlessman J. L., Howard J. B., Rees D. C. ( 1997) Nature 387, 370– 376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nomata J., Ogawa T., Kitashima M., Inoue K., Fujita Y. ( 2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 1346– 1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarma R., Barney B. M., Hamilton T. L., Jones A., Seefeldt L. C., Peters J. W. ( 2008) Biochemistry 47, 13004– 13015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim E. J., Kim J. S., Lee I. H., Rhee H. J., Lee J. K. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3718– 3730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wherland S., Burgess B. K., Stiefel E. I., Newton W. E. ( 1981) Biochemistry 20, 5132– 5140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita Y., Bauer C. E. ( 2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23583– 23588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lovenberg W., Buchanan B. B., Rabinowitz J. C. ( 1963) J. Biol. Chem. 238, 3899– 3913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J., Russell D. W. ( 2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFeeters R. F., Chichester C. O., Whitaker J. R. ( 1971) Plant Physiol. 47, 609– 618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y., Corbett M. C., Fay A. W., Webber J. A., Hodgson K. O., Hedman B., Ribbe M. W. ( 2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 17125– 17130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bursey E. H., Burgess B. K. ( 1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29678– 29685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahlund T. M., Madigan M. T. ( 1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 474– 478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., Sato S., Ikeuchi M., Katoh H., Sasamoto S., Watanabe A., Iriguchi M., Kawashima K., Kimura T., Kishida Y., Kiyokawa C., Kohara M., Matsumoto M., Matsuno A., Nakazaki N., Shimpo S., Sugimoto M., Takeuchi C., Yamada M., Tabata S. ( 2002) DNA Res. 9, 123– 130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore L. R., Goericke R., Chisholm S. W. ( 1995) Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 116, 259– 275 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerich D. W., Burris R. H. ( 1978) J. Bacteriol. 134, 936– 943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biggins D. R., Kelly M., Postgate J. R. ( 1971) Eur. J. Biochem. 20, 140– 143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith B. E., Thorneley R. N., Eady R. R., Mortenson L. E. ( 1976) Biochem. J. 157, 439– 447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly M. ( 1969) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 191, 527– 540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy P. M., Koch B. L. ( 1971) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 253, 295– 297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith R. V., Telfer A., Evans M. C. ( 1971) J. Bacteriol. 107, 574– 575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eady R. R., Postgate J. R. ( 1974) Nature 249, 805– 810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burris R. H. ( 1971) in Chemistry and Biochemistry of Nitrogen Fixation ( Postgate J. R. ed) pp. 105– 160, Plenum Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid B., Einsle O., Chiu H. J., Willing A., Yoshida M., Howard J. B., Rees D. C. ( 2002) Biochemistry 41, 15557– 15565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roe S. M., Gormal C., Smith B. E., Baker P., Rice D., Card G., Lindley P. ( 1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 227– 228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Georgiadis M. M., Komiya H., Chakrabarti P., Woo D., Kornuc J. J., Rees D. C. ( 1992) Science 257, 1653– 1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiu H., Peters J. W., Lanzilotta W. N., Ryle M. J., Seefeldt L. C., Howard J. B., Rees D. C. ( 2001) Biochemistry 40, 641– 650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jang S. B., Seefeldt L. C., Peters J. W. ( 2000) Biochemistry 39, 14745– 14752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.May H. D., Dean D. R., Newton W. E. ( 1991) Biochem. J. 277, 457– 464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rost B., Yachdav G., Liu J. ( 2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W321– 326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss G. P. ( 1988) Eur. J. Biochem. 178, 277– 328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bollivar D. W., Suzuki J. Y., Beatty J. T., Dobrowolski J. M., Bauer C. E. ( 1994) J. Mol. Biol. 237, 622– 640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.