Abstract

CorA is a constitutively expressed magnesium transporter in many bacteria. The crystal structures of Thermotoga maritima CorA provide an excellent structural framework for continuing studies. Here, the ligand binding properties of the conserved interhelical loop, the only portion of the protein exposed to the periplasmic space, are characterized by solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Through titration experiments performed on the isolated transmembrane domain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CorA, it was found that two CorA substrates (Mg2+ and Co2+) and the CorA-specific inhibitor (Co(III) hexamine chloride) bind in the loop at the same binding site. This site includes the glutamic acid residue from the conserved “MPEL” motif. The relatively large dissociation constants indicate that such interactions are weak but not atypical for channels. The present data support the hypothesis that the negatively charged loop could act as an electrostatic ring, increasing local substrate concentrations before transport across the membrane.

The heterogeneous membrane environment is very challenging to mimic for structural, dynamic, and functional studies of membrane proteins. It is not surprising, therefore, that different aspects of the structure can be brought to light under different conditions. Recently, an excellent set of crystal structures of the CorA Mg2+ transporter have been published (1–3), and whereas many CorA mysteries were solved, the highly conserved periplasmic interhelical loops in the pentameric structure were not well resolved. Here, solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of the transmembrane domain resolves these loops, and the secondary structure and ion binding in this domain are characterized.

The 2TM-GxN family of transporters is a large group of integral membrane proteins responsible for metal ion transport (especially for magnesium) across membranes (4, 5). CorA is a prototypical member in this family responsible for magnesium influx as well as efflux in some cases (5, 6). In the extensive phylogenetic analysis, it was shown that CorA is characterized by a universally conserved “GMN” motif in an interhelical loop connecting two conserved transmembrane helices at the C terminus of the full-length protein (4). As the only constitutively expressed magnesium transporter, CorA can play an important role in the viability of pathogens, such as Helicobacter pylori (7).

Pentameric CorA from Thermotoga maritima forms two distinguishable domains; that is, a large cytoplasmic domain and a small transmembrane domain (1–3). In this latter domain there are two transmembrane helices connected by an interhelical periplasmic loop. The first transmembrane helix (TM1)2 lines the pore, whereas the second transmembrane helix (TM2) forms an outer ring of helices, which appears to have only weak interactions with the TM1 helices.

Different mechanisms of substrate transport for CorA have been proposed (1–3, 6, 8), whereas the structure and function of the conserved loop is still an open issue. Based on phylogenetic analyses, it has been shown that there were two conserved sequences in the interhelical loop. One is the GMN motif that is universally conserved, and the other is the MPEL motif that is conserved throughout most bacterial genomes. The glutamic acid residue in the MPEL sequence is almost universally conserved in CorA and CorA homologs in eukaryotic cells, including yeast and humans (4). However, it is not conserved in Methanococcus jannaschii for which CorA has been functionally characterized (9). Although the Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein, studied here, has not been functionally characterized in detail, it has been shown to transport magnesium ions across the membrane.3 Because the interhelical loop is the only portion of the protein exposed to the periplasmic side and because there is a highly conserved negatively charged residue, it has been suggested that the loop could act as an initial magnesium binding site (1). This could result in enhancing Mg2+ concentration at the mouth of the pore, enhancing substrate selection and generating partial cation dehydration (1). Recent functional studies of CorA homologs from yeast have shown that this negatively charged residue in the loop plays an important role in function (10–12). Substitution of Glu by Lys results in a dramatic reduction in transport activity in yeast (10), and substitution of a positively charged residue (Arg in A1r2p, a CorA homolog in yeast) by a Glu increases channel activity (11). However, the CorA from M. jannaschii does not contain either this residue or a negatively charged loop. Based on these results, the negatively charged loop appears to be functionally important and may act as an initial substrate binding site for increasing the local substrate concentration to facilitate ion transport (10–12), whereas it may not be functionally essential at least for some CorA members. However, it has also been argued, based on limited crystallographic data, that the loop may not form a binding site for substrate selection and dehydration (3). Instead, it was speculated that the loop could mediate the relative movement of the two transmembrane helices (3). Accordingly, further investigation of this functionally important loop is warranted.

In the present work we characterize the interaction between the isolated transmembrane domain of CorA (CorA-TMD) and its substrates as well as an inhibitor. Such a “divide and conquer” strategy has been successfully applied to several membrane proteins, such as the M2 protein (a proton channel from influenza A) (13–15), Vpu (a membrane protein encoded by human immunodeficiency virus involved in the budding of new viral particles from the host cell) (16, 17), GlpG (a rhomboid intra-membrane protease) (18, 19), and S2P (a intra-membrane metalloprotease) (20). In addition, the electron density map from the crystal structure of the isolated CorA soluble domain was used to solve the structure of full-length CorA by molecular replacement (1). This suggests that the structural influence of the transmembrane domain on the soluble domain is limited, at least for the conformational state that was crystallized (1). Hence, a divide and conquer strategy for CorA appears to be justified and provides an opportunity to characterize this domain by solution NMR.

It has been shown that NMR has a unique ability of characterize weak interactions that are not readily characterized by other methods (21, 22). In the present work we characterize the binding of two substrates (Mg2+ and Co2+) to the loop as well as an inhibitor (Cobalt(III) hexamine chloride, HexCo3+) by NMR. Our data indicate that the ligands of CorA can weakly but specifically bind to the interhelical loop of CorA-TMD through their interaction with the conserved negatively charged glutamic acid residue in the MPEL motif, supporting the hypothesis that the loop acts as an initial binding site.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of CorA-TMD

CorA-TMD was expressed as a fusion with maltose-binding protein, and after purification of the fusion by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-agarose and tobacco etch virus protease (TEV) cleavage, the maltose-binding protein and TEV were removed by an additional Ni2+-NTA-agarose column. In this fashion CorA-TMD was purified to homogeneity, lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C. All the mutations in the present work were performed by using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene Inc.) and verified by DNA sequencing. Further details have been published (23).

NMR Experiments

NMR samples were prepared by solubilizing lyophilized CorA-TMD in 5% dodecyl-phosphatidylcholine (DPC), 100 mm MOPS, 10% D2O at pH 6.5. Usually the concentration of CorA-TMD was in the range of 0.3–0.5 mm except for the sample used for resonance assignments (1 mm). The concentration was estimated by adsorption at 280 nm (the extinction coefficient was estimated based on the amino acid composition (24)). All spectra were recorded at 50 °C on either a Varian 600 MHz or a Varian 720 MHz NMR spectrometer at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. At this temperature the protein structure was stable, and the spectral resolution was enhanced so that subtle shifts could be observed upon ligand binding. By a combination of the three-dimensional experiment amide proton-to-nitrogen-to-α-carbon correlation (HNCA) (25) and inter-residue 1HN, 15N, 13Cβ, and 13Cα correlation (CBCA(CO)NH) (26), 95% of the expected backbone resonances were assigned unambiguously and confirmed by amino acid-specific labeling.

For hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) exchange experiments a 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (1H,15N HSQC) spectrum of CorA-TMD in 10% D2O was recorded first, and then the sample was concentrated with an ultrafiltration tube (10-kDa cut off) to 50 μl. 450 μl of 100 mm MOPS, pH 6.5, in 100% D2O was added, and the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum was recorded immediately under the same experimental conditions as before.

For paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments, 7.5 μl of 100 mm Mn2+ solution was mixed with 500 μl of CorA-TMD in 5% DPC, 100 mm MOPS, pH 6.5 (final concentration of Mn2+ was 1.5 mm), before recording a 1H,15N HSQC spectrum using the same standard conditions as in the absence of Mn2+.

In NMR titration experiments, the stock solutions of CorA ligands (CoCl2, MgCl2, and HexCoCl3) were prepared in 100 mm MOPS, pH 6.5, and were added to the NMR tube in small aliquots (no more than 5 μl per data point). After 10 min for equilibration, the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum was recorded with the same standard experimental conditions. All data were processed with NMRpipe, and the data analysis was performed using Sparky software. Chemical shift perturbations were calculated for each residue as [(δ1H)2 + (δ15N/5)2]1/2, in which δ1H and δ15N are changes in chemical shift for 1H and 15N, respectively (27).

Circular Dichroism (CD) Experiment

CorA-TMD was solubilized in 5% DPC, 5 mm MOPS at pH 6.5. CorA-TMD concentration was ∼20 μm, determined by the absorption at 280 nm. CD experiments were performed using an AVIV 202 CD spectrometer with 0.1-cm quartz cuvettes. CD spectra were recorded from 260 to 200 nm in 0.5-nm increments and 1-s integration times at 25 °C. Each curve represents the average of at least four scans and a blank containing the same buffer and detergent, as the sample was subtracted from each of the spectra. The spectra were plotted as the molar circular dichroism (Δϵ M−1cm−1). The helical content of the peptides was estimated by fitting the experimental data using the CDPro software package.

Perfluoro-octanoic Acid (PFO)-PAGE

The PFO-PAGE was performed as in a previous report (28). CorA-TMD was solubilized in PFO sample buffer at a concentration of about 50 μm. The proteins in the low molecular weight kit (Amersham Biosciences) were used as standard proteins and loaded onto the gel in separated lanes. The gel was stained with silver nitrate.

Chemical Cross-linking

CorA-TMD was solubilized in 5% DPC (or 5% SDS or 4% PFO), 100 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. The concentration of CorA-TMD in DPC and SDS was the same as in NMR experiments (0.3–0.5 mm). Because of the low solubility, the final concentration in PFO was ∼50 μm. Glutaraldehyde was added, and the final concentration was 10 mm. Chemical cross-linking was performed at room temperature for 2 or 16 h before the addition of 100 mm Tris to stop the reaction. After mixing with 4× SDS loading buffer, the samples were applied to SDS-PAGE (additional details are provided in the supplemental material).

RESULTS

Folding and Oligomerization of CorA-TMD in Detergent Micelles

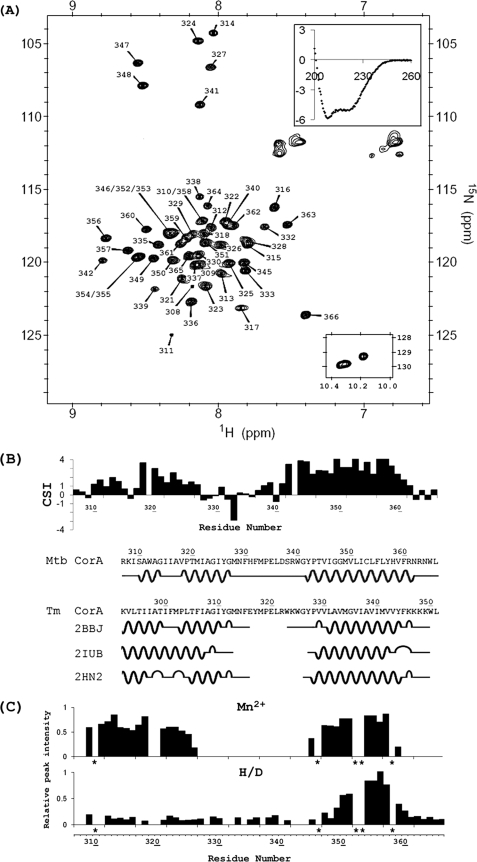

In a preliminary report, the expression and purification of CorA-TMD (sequence shown in Fig. 1B) as well as its basic biophysical properties in SDS micelles were reported (23). Here, further characterizations are achieved in the mild detergent DPC. As shown in Fig. 1A, the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of CorA-TMD is well resolved with a 1H amide chemical shift dispersion of ∼1.25 ppm, typical for transmembrane helical proteins in detergent micelles (29). The high helical content is also supported by the CD spectrum inserted in Fig. 1A, indicating ∼50% helix under similar conditions to those used for the NMR, except for lower protein concentration and lower temperature. The backbone resonances were assigned by standard three-dimensional experiments. It was shown that 54 of 57 non-proline residues could be unambiguously assigned, whereas three resonances were not resolved. The single set of resonances indicates that under these experimental conditions, CorA-TMD has a unique conformation and that the residues in the interhelical loop could be assigned unambiguously, whereas this region was not observed in the three crystal structures (1–3).

FIGURE 1.

The structural fold of CorA-TMD. A, 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of 1 mm CorA-TMD in 5% DPC, 100 mm MOPS, 10% D2O, pH 6.5, at 50 °C. The backbone assignments are shown. The upper inset is the CD spectrum of CorA-TMD in 5% DPC, 5 mm MOPS, pH 6.5, at 25 °C presented as molar circular dichroism, Δϵ (m−1·cm−1) as a function of wavelength (nm). The lower inset is the spectral region of the tryptophan side chain in the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum. B, Cα chemical shift index and the predicted secondary structure for Mtb CorA-TMD as well as the secondary structures of T. maritima CorA from the crystal structures (1–3). The DSSP secondary structures (44) of T. maritima CorA are taken from the Protein Data Bank. C, paramagnetic relaxation enhancements from a 1.5 mm Mn2+ sample (upper) and H/D exchange results from a 90% D2O sample (lower) presented as a comparison of spectral intensities with and without Mn2+ and with and without 90% D2O. Note that five residues labeled with a star (310, 346, 352, 353, and 358) are not included due to resonance overlap.

Based on the Cα chemical shift index (CSI) (Fig. 1B) (30, 31), the secondary structure is predicted and compared with those from three crystal structures of T. maritima CorA (Fig. 1B). Qualitatively, the CSI predicted secondary structure is consistent with the crystal structure in that there are two transmembrane helices linked by an interhelical loop including the GMN signature sequence and the conserved MPEL sequence. There are a couple of differences suggested by the CSI analysis compared with the crystal structures. TM2 appears to be longer in the NMR preparations (22 versus 14–18 residues) and the segment that forms the interhelical loop appears to be shorter (14 versus 17–20 residues) than those suggested by the crystal structures. In addition, a kink observed in TM1 appears to be variable (0, 3, and 7 residues) in the crystal structures compared with 3 residues from the CSI data.

To further characterize the structural fold of CorA-TMD in DPC micelles, an H/D exchange experiment and PRE experiments were performed. As shown in Fig. 1C, TM2 was well shielded from H/D exchange and PRE effects by the DPC micelles. Paramagnetic transition metal ions, such as Mn2+ used here, broaden the resonances of residues exposed to the aqueous solvent. They also influence residues that are slightly buried in the hydrophobic region of detergent micelles (32), due to the relatively long range influence of the ions. Consequently, the PRE results suggest somewhat shorter helices than the CSI analysis. However, the data for TM1 show that it is fully accessible to D2O, resulting in a dramatic decrease of the peak intensities in 90% D2O. This is in sharp contrast with TM2, which displays many sites that do not exchange with D2O, and yet the TM1 resonances like those of TM2 are not relaxed by Mn2+. Such a contrast between TM1 and TM2 suggests that the structural fold of CorA-TMD in DPC micelles is similar to that in the crystal structures; that is, an oligomeric state forming a pore that does not permit the passage of Mn2+. Hence, it appears that TM1 forms a pore-like structure that is solvent-accessible but not Mn2+-accessible, and TM2 is organized as an outer ring of helices that is not exposed to the pore. Although it would be difficult to explain the H/D results for a monomer having two transmembrane helices, the presence of a pore and rotational excursions (33) about the helical TM1 axis is enough to fully explain these results.

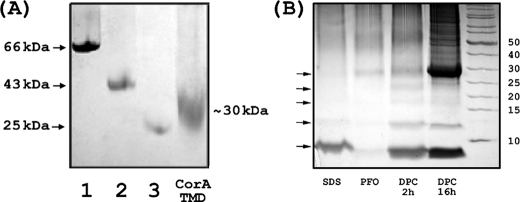

The pentameric state of CorA-TMD in our preparations is also supported by PFO-PAGE and chemical cross-linking results. The PFO gel in Fig. 2A shows no evidence for a monomeric CorA-TMD band (expected at ∼7 kDa), whereas a broad band at ∼30 kDa is observed, suggesting exchange broadening of an oligomeric state. This is despite the low concentration (50 μm) of protein in PFO preparations. The chemical cross-linking experiments provide strong evidence for pentameric formation in DPC micelles. Fig. 2B shows different band patterns on SDS-PAGE gels with cross-linking performed in various detergents for varying reaction times. In 5% SDS most of the protein is observed as a monomer. The PFO preparation shows mostly the pentameric state, although the bands are weak due to the low solubility of CorA-TMD in PFO. In 5% DPC after 2 h of reaction, 5 bands starting from the 7-kDa band demonstrate a ladder from monomer to pentamer. When the reaction in DPC is extended to 16 h, much more protein migrates on the gel as a 28-kDa protein, corresponding to the pentamer of CorA-TMD. This time dependence is not unusual for proteins that are mostly buried in the detergent environment, especially when a high concentration of detergent is used (see the supplemental information). There is no strong band with a higher molecular weight than 28 kDa, indicating that the cross-linking reaction was still specific even after a lengthy reaction time. The clear ladder pattern as well as the increased intensity of the pentamer band after prolonged reaction provides strong evidence that CorA-TMD forms a pentamer in DPC. These results in combination with the lack of exchange broadening in the NMR spectra as well as the H/D and PRE results all support the conclusion that a well folded and pentameric CorA-TMD conformational state is present in our solution NMR preparations.

FIGURE 2.

Oligomerization of CorA-TMD. A, PFO-PAGE of CorA-TMD. The standard proteins used were albumin (lane 1, 66 kDa), ovalbumin (lane 2, 45 kDa), and chymotrypsinogen A (lane 3, 25 kDa). The gel was stained with silver nitrate. B, chemical cross-linking of CorA-TMD in DPC micelles. The experimental details are described under “Experimental Procedures.” The arrows (from the bottom up) indicate the different oligo states (from monomer to pentamer).

Identification of Ligand Binding Sites on CorA-TMD

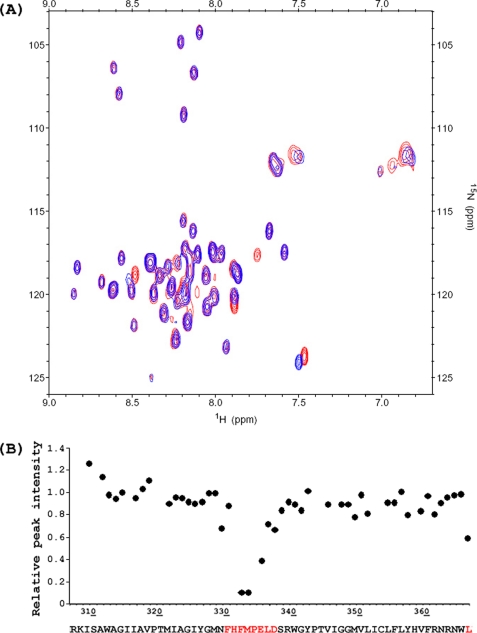

Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement is an effective way to identify protein-ligand interactions. To test whether there are substrate binding sites in CorA-TMD, cation titration experiments were monitored by 1H,15N HSQC spectra. Paramagnetic Co2+ is one of the substrates of CorA, and its paramagnetic effects are relatively weak so that resonance broadening only occurs when the nuclei are close to the bound Co2+. Fig. 3 A shows the comparison of 1H,15N HSQC spectra with and without 1 mm Co2+, illustrating that only a few cross-peaks display significant resonance broadening. Fig. 2B shows that the changes in relative peak intensities around the conserved MPEL motif are very sensitive to Co2+. The most sensitive residues are Phe-332 and Met-333, suggesting that the bound Co2+ was particularly close in space to the amide groups of these two residues. The peak intensity of Leu-366 at the C terminus of the protein also decreased upon the addition of Co2+, possibly due to a weak interaction of Co2+ with the terminal carboxyl group. In addition, it should be noticed that the chemical shifts are hardly affected throughout this structure, indicating that there is little conformational change upon cation binding.

FIGURE 3.

Co2+ binding to CorA-TMD. A, 1H,15N HSQC spectral overlay for samples with (blue) and without 1 mm Co2+ (red). NMR spectra were obtained from a 0.4 mm preparation of CorA-TMD with the addition of Co2+ and otherwise obtained as in Fig. 1. B, changes of the cross-peak intensities after the addition of 1 mm Co2+. The sequence of CorA-TMD is shown below the chart, and the residues in red are those that are sensitive to Co2+. Note that the residues that severely overlap (310, 346, 352, 353, and 358) and the residue with very weak intensity (308) are not included in the analysis.

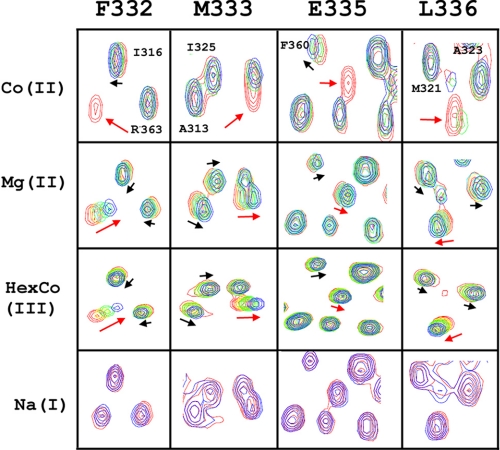

As shown in Fig. 4 by means of chemical shift perturbation in 1H,15N HSQC spectra, the MPEL resonances in the loop that are strongly broadened and/or shifted by Co2+ are also sensitive to Mg2+ and HexCo3+, the latter being a selective inhibitor of CorA (34). As in the case of Co2+, the residues most sensitive to Mg2+ and HexCo3+ are Phe-332 and Met-333, supporting the initial result that cations bind close to these residues. In addition, the patterns of the chemical shift changes in the loop induced by Mg2+ and HexCo3+ are similar, suggesting that both cations induce similar conformational and electronic perturbations. As a negative control, the addition of NaCl even at a concentration of 150 mm did not induce significant spectral changes, suggesting that such interactions are specific for multivalent cations.

FIGURE 4.

Titration of CorA ligands. Regions containing resonances from the MPEL sequence are selected from the 1H,15N HSQC spectra (Fig. 2A) and compared. The concentration of each titrated ligand used was: Co2+, 0, 4, and 10 mm, in red, green, and blue, respectively; Mg2+, 0, 5, 15, 25, 45, 65 mm, in red, pink, yellow, cyan, green, and blue, respectively; HexCo3+ (0, 5, 10, 20 mm, in red, yellow, green, and blue, respectively); Na+ (0, 150 mm). Only the residues that show significant perturbations are labeled. Arrows indicate the resonances that are particularly sensitive to ligand binding, and the orientation of the arrows indicates the direction of the chemical shift changes. The red arrows indicate residues in the loop (Phe-332, Met-333, Glu-335, and Leu-336), and the names of the residues are listed on the top of the panel. The black arrows indicate residues in other parts of CorA-TMD, and the names of the residues are shown in the panel.

Measurement of Binding Constants

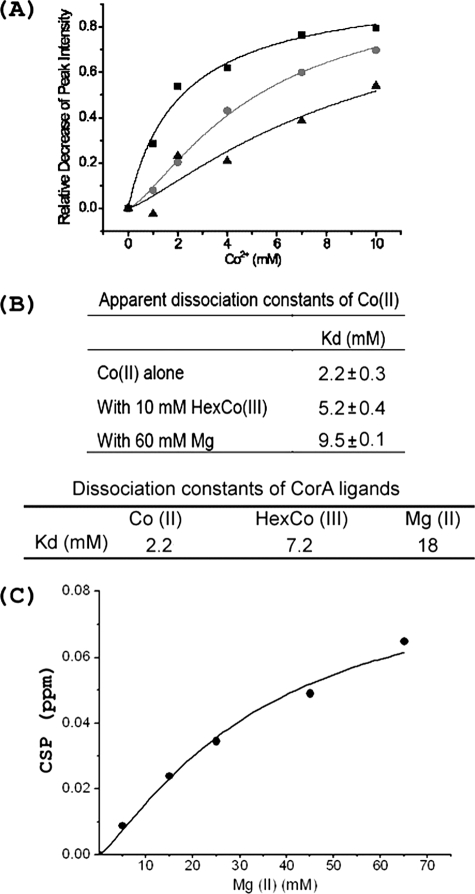

To characterize the affinity of Co2+ for the loop, the peak intensities of Leu-336 (in the MPEL motif) were plotted as a function of Co2+ concentration in an NMR titration (Fig. 5A). Selection of Leu-336 as the indicator lies in its sensitivity to Co2+ binding as well as its relatively strong resonance intensity and good spectral resolution, thereby permitting accurate resonance intensity measurements. Co2+ titration experiments were also performed on samples containing either Mg2+ or HexCo3+ to test whether these ligands compete for the same binding sites (Fig. 5A). It is clear that the addition of Co2+ gradually decreases the peak intensity of Leu-336 and that such intensity reductions also occur in the presence of Mg2+ or HexCo3+. In Fig. 5A, the binding curves are right-shifted in the presence of Mg2+ and HexCo3+, suggesting that Mg2+ and HexCo3+ compete with Co2+ for binding to the loop. By using the Hill equation (35), both the apparent dissociation constants for Co2+ and the dissociation constants for Mg2+ and HexCo3+ can be calculated (Fig. 5B). In observing the chemical shift perturbation of Phe-332 as a function of Mg2+ concentration, the dissociation constant of Mg2+ was measured to be 35 mm (Fig. 5C), which is close to the calculated value from the competition experiment.

FIGURE 5.

Measurement of ligand dissociation constants for CorA-TMD. A, the relative cross-peak intensities for Leu-336 are plotted as a function of Co2+ concentration. Co2+ binding curves to the loop in the absence of other ligands (■), in the presence of 10 mm HexCo (●), and in the presence of 60 mm Mg2+ (▴). B, apparent and calculated dissociation constants for CorA ligands. Data in A were fit to a Hill model by using an Origin® 7.0 software. The calculations were based on competitive binding among ligands. C, Mg2+ binding curve based on chemical shift perturbations to Phe-332 fit to the Hill model. The dissociation constant for Mg2+ was determined to be 35 ± 2 mm. Note that when cation binding to DPC was considered, the actual dissociation constant for Mg2+ was ∼23 mm (see the supplemental material).

Consideration of DPC Binding

DPC is known to have a low affinity for cations through its phosphatidylcholine head group; Kd for Mg2+ has been estimated to be 1000 mm (36). Because these samples are in 5% DPC (142 mm), even this low affinity will influence the available concentration of cations for binding to CorA (see the supplemental material). As a result, the actual dissociation constant of CorA-TMD for Mg2+ is calculated to be ∼23 mm (16 mm from competition experiment and 31 mm from chemical shift perturbation experiment).

Identification of Residues That Contribute to Ligand Binding

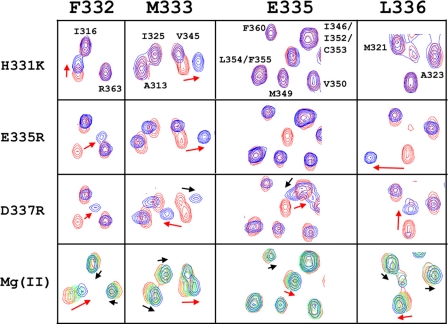

In the vicinity of the MPEL motif, there are three residues that may carry a charge and may be involved in ligand binding: His-331, Glu-335, and Asp-337. To pursue the involvement of these three residues, they were mutated to alanine, but the expression of the mutants was very low. However, when the three residues were mutated to positive charged residues, Lys or Arg, to mimic a bound ion, the expression level was adequate. The 1H,15N HSQC spectra of these mutants are compared with those of the wild type protein with bound Mg2+ in Fig. 6. The three mutants all resulted in chemical shift changes for nearby residues, reflecting changes in the electronic and potentially the conformational environment. The replacement of His-331 by Lys resulted in frequency shifts only for Phe-332 and Met-333 of the MPEL sequence. However, the other two mutants in which a negative charge was replaced by a positive charge induced more significant changes. Even for these mutations, the changes were restricted to the interhelical loop, the last turn of TM1, and the first turn of TM2. Therefore, no global change in structure was induced by these mutations. Importantly, the patterns of the chemical shift perturbations in the three mutants were quite different on the MPEL sequence. Only E335R induces a similar pattern of perturbations as that for Mg2+ binding to the wild type sample. Notably D337R changed the resonance frequency of Val-345 significantly, whereas Mg2+ did not induce such a change even at high concentration, and H331K did not influence the Glu-335 or Leu-336 resonances. Therefore, it seems most likely that of these charged residues in the loop, Glu-335 is directly involved in binding divalent cations and the inhibitor.

FIGURE 6.

Mutation of charged residues in the loop. Regions of the 1H,15N HSQC spectra for three mutants (H331K, E335R, and D337R), compared with those from the Mg2+ titration as in Fig. 3. Arrows indicate resonances particularly sensitive to mutations and the direction of the chemical shift changes. The red arrows indicate residues in the loop, and the black arrows indicate residues in other parts of CorA-TMD.

The Long Range Effects of Ligand Binding

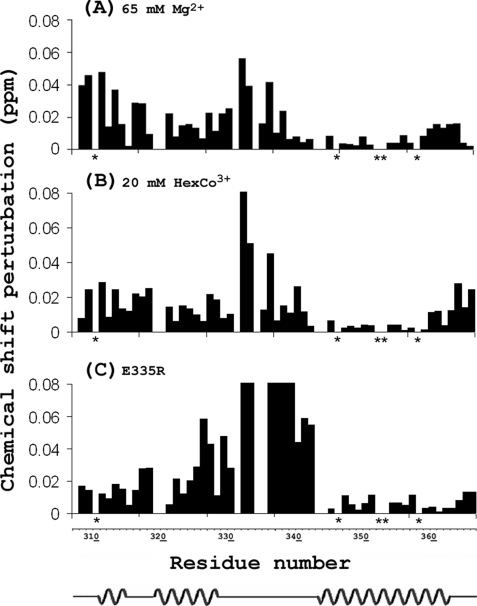

It was observed in the titrations of both Mg2+ and HexCo3+ that small but significant chemical shift perturbations (>0.01 ppm) (27, 37) occurred to resonances other than those representing loop residues (Fig. 7 and also as indicated by the black arrows in Fig. 4). The perturbations at the termini are not likely to be biologically significant, but although TM2 shows no significant perturbations, TM1 does in the presence of Mg2 and HexCo3+ and for the mutant E335R. It could be suggested that Mg2+ influences TM1 by penetrating into the pore; however, it is unlikely that HexCo3+ would do so, and obviously the covalently linked charge in the E335R mutant cannot penetrate into the pore. Therefore, we suggest that these perturbations are the result of conformational changes. Structural changes are likely to be small because the chemical shift perturbations are small, and they are likely to be local because there are no significant perturbations or conformational changes in TM2.

FIGURE 7.

Chemical shift perturbations induced by CorA ligands or mutations of CorA-TMD. A, perturbations induced by 65 mm Mg2+. B, perturbations induced by 20 mm HexCo3+. C, perturbations induced by the E335R mutation (the perturbations for residues from 331 to 338 are much larger than 0.08 ppm and are truncated for clarity). The secondary structure of CorA-TMD is illustrated below the residue numbers based on CSI analysis in Fig. 1. Note that the uncertainty in chemical shift perturbation is ∼0.01 ppm, and five residues labeled with a star (310, 346, 352, 353 and 358) are not included due to resonance overlap.

DISCUSSION

Conformation and Oligomerization of the Isolated CorA- TMD

Divide and conquer is an attractive strategy for studying the structure and function of large membrane proteins. The isolated domain is a simplified system compared with the full-length protein and at least for some membrane proteins, it has been shown that the transmembrane domain can be viewed predominantly as an independent structural and functional unit.

In a previous report, it was shown that CorA-TMD fused with the maltose-binding protein was primarily expressed in the membrane fraction (23), suggesting that the CorA-TMD fusion was inserted into the membrane during expression, potentially as a native-like structure by the cellular machinery. In the present study, CD, gel electrophoresis, and NMR data indicate that the purified CorA-TMD is well-folded in DPC micelles (Fig. 1A), and its predicted secondary structure based on the chemical shifts is largely consistent with the crystal structures (Fig. 1B), further suggesting that CorA-TMD is correctly folded in the membrane mimetic environment.

Both H/D exchange experiments and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement experiments are general methods for characterizing the structural fold of membrane proteins in detergent micelles (32). Our data have shown that although TM1 was well shielded from a soluble paramagnetic probe, Mn2+, it was highly accessible to D2O implying a selective pore-like structure (Fig. 1C). Under the same conditions, TM2 showed typical behavior for a transmembrane helix buried in detergent micelles, with little access to water. This supports the crystallographic and mutational studies that indicate that TM1 is pore-lining and that TM2 is not. In addition, the full accessibility of all TM1 residues to solvent suggests that the pore-forming helix (TM1) is undergoing rotational excursions about the helical axes, resulting in exposure of the entire TM1 backbone to the aqueous solvent. Such rotational excursions have been observed in the full-length tetrameric M2 protein from Influenza A virus in lipid bilayers (33). PFO-PAGE (Fig. 2A) gels display a broad band for CorA-TMD suggestive of oligomeric exchange with an apparent molecular mass of 30 kDa. The chemical cross-linking results (Fig. 2B) show that CorA-TMD forms a pentameric structure in DPC. In fact, the pentameric state of CorA-TMD was anticipated, as the soluble domain has been shown to be monomeric (1) or dimeric (3), whereas the full-length protein is pentameric (1–3).

Ligand Binding to the Loop of CorA-TMD

The NMR titration (Figs. 3–5) showed the following features for the interhelical loop that extends approximately from residues 328 to 340. 1). Co2+, Mg2+, and the selective inhibitor HexCo3+ broadened or shifted the resonances from the loop, especially those near the MPEL motif, whereas monovalent Na+ did not, suggesting a specific and divalent selective ligand binding site in the loop. 2) The single set of the resonances from the loop in the ligand titration experiment suggested that all five MPEL motifs in one pentamer took part in a fast exchange process upon ligand binding and that the bound cation may “jump” rapidly among the binding sites in one pentamer relative to the NMR timescale. 3) Competition experiments suggest that all of the multivalent ligands bind to the same site in the loop. The CorA inhibitor, HexCo3+, which is an analog of hydrated Mg2+, binds to the same site as Mg2+, suggesting that Mg2+ binds as a hydrated ion as hypothesized by Kucharski et al. (34). 4) The dissociation constants for the ligands are in the millimolar range, indicating a weak interaction.

Introducing a positively charged residue in the vicinity of the metal binding site to mimic the metal-bound state is an efficient tool for functional studies (3, 38). Lys and Arg were introduced at His-331, Glu-335, and Asp-337, and the 1H,15N HSQC spectra showed significant chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 6). Through the spectral comparison, Glu-335 was identified as the residue that interacts most directly with the ligand, presumed here to be hydrated Mg2+. Of these charged residues that were mutated, Glu-335 is the only highly conserved residue, and functional studies have previously shown the importance of this conserved glutamic acid residue in CorA homologs in yeast (10, 11). Interestingly, a nearby aspartic acid (Asp-337) does not appear to be essential for such interactions, indicating that substrate and inhibitor binding is a specific interaction in the loop. Although functional studies of CorA homologs in yeast have shown that substitution of the conserved glutamic acid by a positively charged residue abolished the channel activity (12), a recent J. Biol. Chem. paper (39) indicated that this residue was not necessary for function. However, they suggested that the glutamic acid negative charge may serve to increase the local substrate concentration, as described here. Therefore, it would not be surprising for Methanococcus CorA to still have magnesium transportation activity (9, 34).

Nonspecific Binding of Ligands to the Detergent Micelles

DPC is a zwitterionic detergent, and therefore, its potential interaction with the charged ligands should be considered. Given that the head group of DPC is phosphatidylcholine, the interaction between PC and metal ions can be garnered from the literature where it was reported that the Kd of Mg2+ to phosphatidylcholine lipids is 1000 mm (36). Therefore, the Kd of DPC for Mg2+ can be estimated to be 1000 mm. This estimation brings about two results. First, in our experiments the calculated Kd of Mg2+ in the loop (Fig. 5) was ∼20–30 mm, suggesting that the observed perturbations were caused by Mg2+ binding to the protein and not to the detergent micelles. The very limited number of resonances in the loop that were perturbed by metal binding further supports our conclusion of a protein-specific binding site. Second, because of the high concentration of DPC used in the experiments, the effective concentration of the substrate/inhibitor is lower than the total concentration, resulting in an underestimation of the affinity of the substrate/inhibitor to the protein. Even so, the Kd is still in the mm range, indicating a weak interaction (see supplemental material).

Long Range Effects of Ligand Binding in the Loop

Resonances from TM1 residues also underwent small chemical shift perturbations in Mg2+ and HexCo3+ titration experiments (Fig. 7). Additional data showed that 20 mm Co2+ could only shift the resonance frequencies from these residues and not broaden them, suggesting that the chemical shift perturbations were not due to a paramagnetic relaxation effect between the ligands and these residues in TM1 but rather through a conformational change. This is supported by the 1H,15N HSQC spectrum of E335R mutant, where the introduction of a positive charge in the loop resulted in significant perturbations to TM1, whereas it had little effect on TM2. TM1 forms the ion-conducting pore that is known to have open and closed states (1–3). This helix includes several glycines and a proline residue, each of which could represent “pro-kink” sites or sites where the helix could be distorted in transitions from one functional state to another. The observed perturbations throughout TM1 are quite small, suggesting the possibility of a small packing rearrangement of the helices.

Biological Implications

The functional transmembrane domain of CorA from Mtb has been characterized by solution NMR with respect to its structural fold and metal binding. As in the Lunin et al. (1) crystal structure, TM1 appears to be kinked, based on the CSI data presented in Fig. 1B. In addition, TM2 appears to be significantly longer in the NMR characterization. Indeed, the crystal structures (especially 2BBJ and 2IUB) appear to have helices that are not long enough to span a lipid bilayer. As a result, the periplasmic exposed loop between the helices is substantially shorter in the NMR characterization. The universally conserved GMN sequence is at the end of TM1, whereas the highly conserved MPEL sequence is in the very middle of the loop. Both the crystal structure and the present study use detergent environments for solubilizing the transmembrane domain, and as both of these environments represent a model membrane environment, the structural data may only be an approximation for the native fold. For this structure we have used a lysolipid, DPC, which has a reputation for forming an environment for membrane proteins that permits native functional activity. Clearly, the selectivity of the metal binding site bodes well for the topological characterization presented here.

In functional studies it has been shown that CorA affinity for ligands is in the micromolar range (34, 40). In addition, as the selective inhibitor HexCo3+ cannot pass through the channel, it is expected to have a high affinity binding site near the mouth of the pore. However, we did not detect such a site either for substrates or for the inhibitor. Our data showed that the loop can only form a weak binding site, and therefore, the negative charged loop is not the place where HexCo3+ blocks the channel. It is not surprising because in functional studies HexCo3+ has been shown to have similar affinity to both Salmonella typhimurium CorA (with a negative charged loop) and M. jannaschii CorA (without a negative charged loop) (34). It has also been previously shown that a weak inhibitor of CorA, calcium ion, can enter the pore in a cavity below the level of Asn-314 (the N in the GMN motif in T. maritima CorA) but above the proposed “hydrophobic belt,” consisting of Thr-305 and Met-302 in T. maritima CorA (3). In this cavity there may be a high affinity binding site for HexCo3+; however, our experiments did not show such a binding site, potentially because our preparations represent a closed state for the pore.

The low affinity of the MPEL site for Mg2+ (∼23 mm) is well below the native concentration of Mg2+ (1 mm). Although it is possible that such low affinity might be the result of a distorted structure, we would argue that these low affinity sites serve to increase the local concentration of Mg2+ at the mouth of the pore. As shown in the supplemental information in a crude calculation, even the 23 mm affinity of these binding sites can effectively increase the concentration at the mouth of the pore from 1 to 12 mm. Such a significant increase in substrate concentration at the entrance of the pore will significantly increase the probability for conductance across the membrane. Such an electrostatic ring has been discussed for other channels including KirBac1.1 (41) and nAchR (42) as well as its ability to increase the local concentration of ions (43). The observed affinity suggests that under physiological conditions there is no more than one ion bound in this electrostatic ring at a time.

The NMR results further suggest that the binding is highly dynamic, i.e. multiple resonances are not observed; rather an average resonance is observed. Consequently, the bound ion appears to jump between the MPEL binding sites in the pentamer on a timescale that is rapid compared with a few hundred Hz (the separation of resonances representing the bound and unbound states). This dynamic interaction also suggests weak binding interactions, that the ion is binding in a hydrated state, and that the energetically costly steps of dehydrating the ion of its primary hydration sphere have not been invested in this binding mode. The small number of chemical shift perturbations within the transmembrane domain and their small size also suggest that the cation binding is through the hydrated state of the cation. Chemical shift perturbation for a dehydrated cation would be expected to be much larger. Because HexCo3+ is a model for hydrated Mg2+ and because it binds in the same location as Mg2+, we conclude that Mg2+ binds to the loop as the hydrated cation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NMR experiments were conducted at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory supported by Cooperative Agreement DMR-0654118 with the National Science Foundation and the State of Florida.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM064676 and AI073891.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Materials and Methods,” “Results and Discussion,”Figs. 1 and 2, and additional references.

M. E. Maguire, personal communication.

- TM1

- the first transmembrane helix (of CorA), also known as helix 7 in the full-length protein

- TM2

- the second transmembrane helix (of CorA), also known as helix 8 in the full-length protein

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- CorA-TMD

- transmembrane domain of CorA

- CSI

- chemical shift index

- DPC

- dodecyl-phosphatidylcholine

- HexCo3+

- cobalt(III) hexamine chloride

- MOPS

- 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- PFO

- perfluoro-octanoic acid

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- H/D

- hydrogen/deuterium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lunin V. V., Dobrovetsky E., Khutoreskaya G., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Doyle D. A., Bochkarev A., Maguire M. E., Edwards A. M., Koth C. M. ( 2006) Nature 440, 833– 837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eshaghi S., Niegowski D., Kohl A., Martinez Molina D., Lesley S. A., Nordlund P. ( 2006) Science 313, 354– 357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payandeh J., Pai E. F. ( 2006) EMBO J 25, 3762– 3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoop V., Groth-Malonek M., Gebert M., Eifler K., Weyand K. ( 2005) Mol. Genet. Genomics 274, 205– 216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papp-Wallace K. M., Maguire M. E. ( 2007) Mol. Memb. Biol 24, 351– 356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niegowski D., Eshaghi S. ( 2007) Cell. Mol. Life Sci 64, 2564– 2574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfeiffer J., Guhl J., Waidner B., Kist M., Bereswill S. ( 2002) Infect. Immun 70, 3930– 3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguire M. E. ( 2006) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 16, 432– 438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R. L., Gottlieb E., Kucharski L. M., Maguire M. E. ( 1998) J. Bacteriol 180, 2788– 2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weghuber J., Dieterich F., Froschauer E. M., Svidova S., Schweyen R. J. ( 2006) FEBS J 273, 1198– 1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wachek M., Aichinger M. C., Stadler J. A., Schweyen R. J., Graschopf A. ( 2006) FEBS J 273, 4236– 4249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindl R., Weghuber J., Romanin C., Schweyen R. J. ( 2007) Biophys. J 93, 3872– 3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duff K. C., Ashley R. H. ( 1992) Virology 190, 485– 489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J., Kim S., Kovacs F., Cross T. A. ( 2001) Protein Sci 10, 2241– 2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu J., Fu R., Nishimura K., Zhang L., Zhou H. X., Busath D. D., Vijayvergiya V., Cross T. A. ( 2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 6865– 6870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marassi F. M., Ma C., Gratkowski H., Straus S. K., Strebel K., Oblatt-Montal M., Montal M., Opella S. J. ( 1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 96, 14336– 14341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma C., Marassi F. M., Jones D. H., Straus S. K., Bour S., Strebel K., Schubert U., Oblatt-Montal M., Montal M., Opella S. J. ( 2002) Protein Sci 11, 546– 557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Zhang Y., Ha Y. ( 2006) Nature 444, 179– 180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z., Yan N., Feng L., Oberstein A., Yan H., Baker R. P., Gu L., Jeffrey P. D., Urban S., Shi Y. ( 2006) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 13, 1084– 1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng L., Yan H., Wu Z., Yan N., Wang Z., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y. ( 2007) Science 318, 1608– 1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeuchi K., Wagner G. ( 2006) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 16, 109– 117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonvin A. M., Boelens R., Kaptein R. ( 2005) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 9, 501– 508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu J., Qin H., Li C., Mukesh S., Cross T., Gao F. ( 2007) Protein Sci 16, 2153– 2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pace C. N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T. ( 1995) Protein Sci 4, 2411– 2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruben D., Bodenhausen G. ( 1980) Chem. Phys. Lett 69, 185– 189 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clore G. M., Bax A., Driscoll P. C., Wingfield P. T., Gronenborn A. M. ( 1990) Biochemistry 29, 8172– 8184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chill J. H., Louis J. M., Miller C., Bax A. ( 2006) Protein Sci 15, 684– 698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramjeesingh M., Huan L. J., Garami E., Bear C. E. ( 1999) Biochem. J 342, 119– 123 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page R. C., Moore J. D., Nguyen H. B., Sharma M., Chase R., Gao F. P., Mobley C. K., Sanders C. R., Ma L., Sonnichsen F. D., Lee S., Howell S. C., Opella S. J., Cross T. A. ( 2006) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 7, 51– 64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D. ( 1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 171– 180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y., Jardetzky O. ( 2002) Protein Sci 11, 852– 861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franzin C. M., Gong X. M., Thai K., Yu J., Marassi F. M. ( 2007) Methods 41, 398– 408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian C., Gao P. F., Pinto L. H., Lamb R. A., Cross T. A. ( 2003) Protein Sci 12, 2597– 2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kucharski L. M., Lubbe W. J., Maguire M. E. ( 2000) J. Biol. Chem 275, 16767– 16773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill A. V. ( 1910) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 40, 190– 224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLaughlin A., Grathwohl C., McLaughlin S. ( 1978) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 513, 338– 357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelev V., Aktas H., Marintchev A., Ito T., Frueh D., Hemond M., Rovnyak D., Debus M., Hyberts S., Usheva A., Halperin J., Wagner G. ( 2006) J. Mol. Biol 364, 352– 363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forrest L. R., Tavoulari S., Zhang Y. W., Rudnick G., Honig B. ( 2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 12761– 12766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payandeh J., Li C., Ramjeesingh M., Poduch E., Bear C. E., Pai E. F. ( 2008) J. Biol. Chem 283, 11721– 11733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moncrief M. B., Maguire M. E. ( 1999) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 4, 523– 527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo A., Gulbis J. M., Antcliff J. F., Rahman T., Lowe E. D., Zimmer J., Cuthbertson J., Ashcroft F. M., Ezaki T., Doyle D. A. ( 2003) Science 300, 1922– 1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imoto K., Busch C., Sakmann B., Mishina M., Konno T., Nakai J., Bujo H., Mori Y., Fukuda K., Numa S. ( 1988) Nature 335, 645– 648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle D. A. ( 2004) Eur. Biophys. J 33, 175– 179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabsch W., Sander C. ( 1983) Biopolymers 22, 2577– 2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.