Abstract

Fibronectin (FN) is a large extracellular matrix glycoprotein important for development and wound healing in vertebrates. Recent work has focused on the ability of FN fragments and embryonic or tumorigenic splicing variants to stimulate fibroblast migration into collagen gels. This activity has been localized to specific sites and is not exhibited by full-length FN. Here we show that an N-terminal FN fragment, spanning the migration stimulation sites and including the first three type III FN domains, also lacks this activity. A screen for interdomain interactions by solution-state NMR spectroscopy revealed specific contacts between the Fn N terminus and two of the type III domains. A single amino acid substitution, R222A, disrupts the strongest interaction, between domains 4–5FnI and 3FnIII, and restores motogenic activity to the FN N-terminal fragment. Anastellin, which promotes fibril formation, destabilizes 3FnIII and disrupts the observed 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction. We discuss these findings in the context of the control of cellular activity through exposure of masked sites.

Fibronectin (FN),4 a large multidomain glycoprotein found in all vertebrates, plays a vital role in cell adhesion, tissue development, and wound healing (1). It exists in soluble form in plasma and tissue fluids but is also present in fibrillar networks as part of the extracellular matrix. The structures of many FN domains of all three types, FnI, FnII, and FnIII, are known, for example (2–4). Although interactions between domains that are close in primary sequence have been demonstrated (3, 5), studies of multidomain fragments generally assume a beads-on-string model (2). There is, however, much evidence for the presence of long range order in soluble FN as a number of functional sites, termed cryptic, are not active in the native molecule, until exposed through conformational change. These include self-association sites (5–8), sites of protein interactions (9), and sites that control cellular activity (10, 11). Low resolution studies of the FN dimer suggest a compact conformation under physiological conditions (12–14); however, attempts to define large scale structure in FN by small angle scattering or electric birefringence (15–17) have yielded contradictory results. Interpretation of domain stability changes in terms of interaction sites (18) has also not been straightforward (2), possibly because of domain stabilization through nearest-neighbor effects (19, 20).

A FN splicing variant produced in fetal and cancer patient fibroblasts, termed migration stimulation factor (MSF), stimulates migration of adult skin fibroblasts into type I collagen gels (10, 21) and breast carcinoma cells using the Boyden chamber (22). MSF comprises FN domains 1FnI to 9FnI, a truncated 1FnIII, and a small C-terminal extension; a recombinant FN fragment corresponding to 1FnI-9FnI (Fn70kDa) displays the same activity (10). An overview of FN domain structure and nomenclature is presented in Fig. 1a. Further experiments sub-localized full motogenic activity to the gelatin binding domain of FN (GBD, domains 6FnI-9FnI) (23) and partial activity to a shorter fragment spanning domains 7–9FnI (24). Two IGD tripeptides of domains 7FnI and 9FnI were shown to be essential through residue substitutions and reconstitution of partial motogenic activity in synthetic peptides (10, 24, 25); however, similar IGD tripeptides outside the GBD, on domains 3FnI and 5FnI, appear to have little effect (10, 23). Full-length adult FN does not affect cell migration in similar assays (10, 23); thus motogenic activity sites are presumed to be masked in the conformation adopted by soluble FN, although they could be exposed by molecular rearrangement.

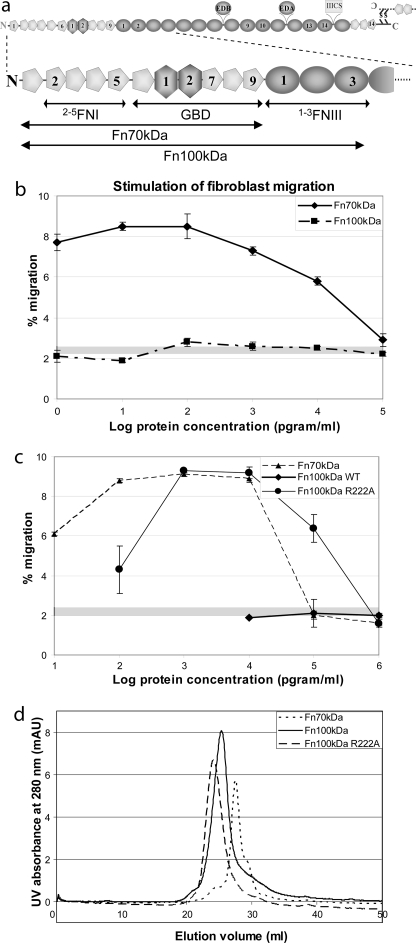

FIGURE 1.

Motogenic activity of FN fragments. a, schematic representation of the FN domain structure (top) and enlargement of the FN N terminus (bottom). Type I domains are shown as pentagons; type II domains as hexagons; and type III domains as ovals. b, comparison of motogenic activity versus protein concentration of wild-type Fn70kDa and Fn100kDa fragments. Error bars are derived from duplicate experiments, and a gray band denotes migration activity of media without additives. c, similar comparisons for mutant Fn100kDa fragments. d, analytical size exclusion chromatography of large FN fragments. The trace of UV absorbance at 280 nm versus elution volume shown here indicates a larger hydrodynamic radius for Fn100kDa R222A compared with the wild type, consistent with our model (Fig. 6a).

Here we show that a recombinant fragment, closely matching a truncated form of FN identified in zebrafish (26), as well as amphibians, birds, and mammals (27), does not stimulate cell migration. This fragment is similar to MSF but includes the first three FnIII domains (1–3FnIII), suggesting that these domains are responsible for a conformational transition that masks the activity sites in this construct and probably in full-length FN. To identify the mechanism behind this transition, we performed structural studies by solution NMR spectroscopy and identified a specific long range interaction between domains 4–5FnI and 3FnIII as essential for this masking effect. Interestingly, this interaction does not involve direct contacts with the GBD but possibly represses motogenic activity through chain compaction, evident in analytical size exclusion assays. Intramolecular interactions thus provide a mechanism by which conformational rearrangement induced, for example, by tension or splicing variation can result in cellular activity differences.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

Expression and purification of type I domain pairs of FN (2–3FnI, FN residues 93–182; 4–5FnI, residues 183–275; and 8–9FnI, residues 516–608) were described previously (24, 28). 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI (residues 305–515) and GBD (residues 305–608) were produced as described (29). Expression and purification of 1FnIII and 2FnIII have been described previously (5). Domain 3FnIII (residues 810–900) and 2–3FnIII were produced in a similar manner. In all cases, protein purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE and NMR as being in excess of 95%.

2–5FnI was integrated in Pichia pastoris in a manner analogous to that described previously (30). Expression in media buffered at pH 3.5 at 25 °C produced small amounts of protein and a number of proteolytic degradation products. 2–5FnI was concentrated from the media by retention in a cation exchange column, and protein-containing fractions were pooled and purified by size exclusion chromatography. SDS-PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions produced the expected protein band essentially free of degradation by-products (supplemental Fig. 6). 1H-15N HSQC spectra of this protein showed substantial heterogeneity and significant presence of an unfolded population of molecules (supplemental Fig. 6). The different species were separated using a shallow NaCl gradient in a high resolution anion exchange column (MonoQ, GE Healthcare) at pH 10.6 (supplemental Fig. 6). Approximately 0.2 mg of correctly folded purified protein could be obtained from 0.5 liters of P. pastoris culture under high density fermentation conditions.

Recombinant MSF was produced in Escherichia coli, as described previously (10), from a transcript that included the complete N-terminal FN sequence to the middle of 1FnIII (residue 647) and a unique C-terminal amino acid tail. FN fragments consisting of residues 48–608 (Fn70kDa) or 48–900 (Fn100kDa, wild-type or with residue substitutions) were cloned into vector pHLsec resulting in final proteins with three vector-derived residues at the N terminus (ETG) and nine, including a His tag, at the C terminus (GTKHHHHHH). These proteins were produced in human cell line HEK293T by transient expression as described previously (31). Proteins were expressed for 4 days and then purified directly from the media by metal affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion in phosphate-buffered saline. A typical yield of purified Fn100kDa was 20 mg per liter of conditioned media. Protein purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE as 85–90%. The proteolytic Fn30kDa fragment was purchased from Sigma.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation Equilibrium

The molecular mass of Fn100kDa was determined by sedimentation equilibrium analysis using an Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman). Fn100kDa samples (5 and 11 μm) in phosphate-buffered saline were centrifuged in double sector 12-mm centerpieces at 10,000, 12,000, and 16,000 rpm at 20 °C. Protein sedimentation was monitored at 280 nm. Although expected to be glycosylated at three separate sites, Fn100kDa gave a molecular mass of ∼95 kDa suggesting little glycosylation of the final protein.

Analytical Size Exclusion Chromatography

Small (0.1 ml) samples of FN fragments were passed through an analytical Superdex 200 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline. An Äkta FPLC system with 0.5-cm path length (GE Healthcare) was used for data recording of UV absorption at 280 nm.

Collagen Gel Migration Assays

Type I collagen was extracted from rat tail tendons and used to make 2-ml collagen gels in 35-mm plastic tissue culture dishes as described previously (32). Collagen gels were overlaid with 1 ml of either serum-free minimum Eagle's medium or serum-free minimum Eagle's medium containing four times the final concentration of recombinant proteins. Confluent stock cultures of fibroblasts were trypsinized, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in growth medium containing 4% donor calf serum at 2 × 105 cells/ml, and 1-ml aliquots were added to the overlaid gels for a final concentration of 1% serum in both control and recombinant proteins containing cultures. The assay cultures were incubated for 4 days, and the percentage of fibroblasts found within the three-dimensional gel matrix was then ascertained by microscopic observation of 10 randomly selected fields in each of two duplicate cultures, as described previously (10, 24). Each experiment was repeated a minimum of two times.

NMR Spectroscopy and Data Analysis

All experiments were performed at 30 °C using home-built spectrometers with 11.7–22.3 tesla field strengths in a 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 6.0, 20 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentanesulfonic acid, 0.02% NaN3, and 5% v/v D2O sample buffer unless otherwise noted. Sequential chemical shift assignments were performed using standard triple-resonance experiments. Analysis of spectral perturbations upon protein interactions and determination of equilibrium parameters were performed as described (30).

Notes

The chemical shift assignments of 2–3FnI, 4–5FnI, and 3FnIII have been deposited in the BioMagResBank under accession numbers 15756, 15758, and 15759, respectively. The amino acid sequences and numbering schemes used here correspond to the human FN UniProt accession number P02751. The 2–5FnI model was constructed from the 2–3FnI and 4–5FnI crystal structures (4) assuming that the 3–4FnI interface is similar to that of other FnI domain pairs. The 2–3FnIII model was constructed by threading the amino acid sequence through the 9–10FnIII structure (Protein Data Bank code 2MFN) using the Phyre web service (33) and then substituting 2FnIII with the high resolution NMR structure of that domain excluding the flexible N terminus (5).

RESULTS

N-terminal FN Fragment Does Not Affect Fibroblast Migration

A previously identified alternatively spliced mRNA variant of FN (26, 27) encodes the FN N terminus up to the complete domain 3FnIII and a highly variable C-terminal amino acid tail. We produced a recombinant version of this fragment excluding the tail (Fig. 1a) using transient expression in HEK293T cell line; we refer to this fragment as Fn100kDa, based on its apparent mobility in denaturing gels. Fn100kDa is highly soluble, and analytical ultracentrifugation experiments showed that it is monomeric at ∼11 μm (1.0 mg/ml) concentration (supplemental Fig. 1). This construct includes domains 7FnI and 9FnI that harbor the two IGD tripeptides necessary for stimulation of cell migration; however, assays using adult skin fibroblasts showed no effect on cell motility (Fig. 1a), a result similar that obtained with full-length FN (10, 23). Inclusion of the C-terminal amino acid tail in this construct did not alter this result (data not shown). In contrast, a recombinant fragment that lacks the first three FnIII domains (Fn70kDa) displays full activity in the same assays, in agreement with previous results (10). Hence, we hypothesized that domains 1–3FnIII are responsible for a structural rearrangement in Fn100kDa that masks the sites of motogenic activity. A likely cause of this rearrangement would be long range interactions between the FnIII domains and the remainder of Fn100kDa. We therefore sought to identify any such interactions using NMR.

Specific Interactions between Domains in Fn100kDa

We performed assays for interdomain interactions using solution NMR spectroscopy by monitoring chemical shift perturbations in 1H-15N HSQC spectra during titrations of FN fragments. Domains 1FnIII, 2FnIII, and 3FnIII were tested against fragments 1–2FnI, 2–3FnI, 4–5FnI, 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI, and 8–9FnI in all pairwise combinations at 30 °C and 20 mm NaCl, 20 mm sodium phosphate pH 6.0 buffer; the choice of buffer pH reflects a compromise between solubility of FnI domains (high at lower pH), and solubility and stability of FnIII domains (high at physiological pH). Under these conditions FnIII domains remained folded and soluble to at least 1 mm concentration, whereas FnI domains are less soluble (∼0.2 mm for 4–5FnI).

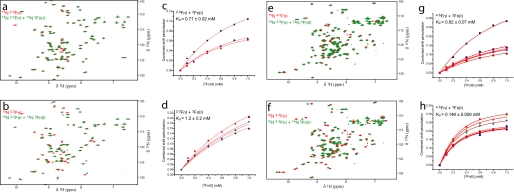

As shown in Table 1, a total of four specific interactions were detected between 2–3FnI or 4–5FnI and 2FnIII or 3FnIII (Fig. 2); the interaction between 4–5FnI and 3FnIII has an equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) of 146 ± 9 μm under these conditions, whereas others are weaker (Kd of 700–1200 μm). FN conformation is sensitive to ionic strength (11, 34), and thus we tested for the persistence of these four interactions under physiological conditions (150 mm NaCl). Chemical shift perturbations were still observed, although we were unable to estimate dissociation constants accurately in some cases because of low fractional saturation in the respective titrations. The 4–5FnI-3FnIII titration yielded a Kd of 800 ± 46 μm (data not shown); the 5-fold reduction in affinity is consistent with the increase in ionic strength, assuming a linear anticorrelation between these phenomena (35). Combined analysis of 1H and 15N perturbations shows good correlation between low and physiological NaCl concentrations (supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that the domains interact in a similar fashion over this range of ionic strength.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants from inter-domain interactions (Kd, mm)

| FN fragments | 1FnIII | 2FnIII | 3FnIII |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2FnI | No interaction detecteda | –b | –b |

| 2–3FnI | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | |

| 4–5FnI | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.146 ± 0.009 | |

| 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI | No interaction detecteda | ||

| 8–9FnI | |||

a Based on the extent of perturbations observed in other titrations, and the stoichiometric ratios used, we estimate a lower limit for these interactions as in excess of 7.5–10 mm.

b Small perturbations were detected on2FnI resonances but not on1FnI; hence we consider these interactions in the context of2–3FnI.

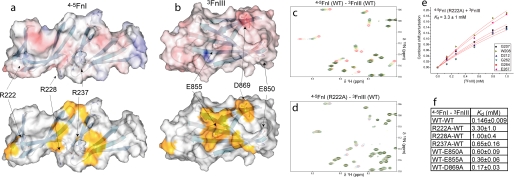

FIGURE 2.

NMR spectra of interdomain interactions. a and b, 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 2–3FnI alone (red) or with excess 2FnIII or 3FnIII (green), respectively. c and d, fits of chemical shift perturbations against protein concentration to derive Kd values for the 2–3FnI-2FnIII and 2–3FnI-3FnIII titrations, respectively. e–h, HSQC spectra and titration fits for the 4–5FnI-2FnIII and 4–5FnI-3FnIII titrations.

Previously, we reported an interaction Kd under physiological ionic strength conditions of ∼85 μm between wild-type 1–2FnIII and 1–5FnI (Fn30kDa), determined by surface plasmon resonance (5). This is substantially tighter than the interactions reported here between isolated FnIII domains and FnI pairs under similar conditions. However, the nature of the two techniques used, especially the difference of limited diffusion in surface plasmon resonance versus three-dimensional diffusion in NMR, makes comparisons across techniques difficult. The 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction did not prove amenable to surface plasmon resonance analysis (supplemental Fig. 3); thus, we tested the 1–2FnIII-Fn30kDa interaction by NMR (supplemental Fig. 4). As shown, only few and very small perturbations are detected in the NMR spectra under physiological conditions, compared with similar spectra of 4–5FnI-3FnIII. Similarly, a recent study of wild-type 1–2FnIII and Fn70kDa did not show substantial interactions between these components using fluorescence (36). Hence, we infer that 4–5FnI-3FnIII is the strongest among these interactions of wild-type proteins.

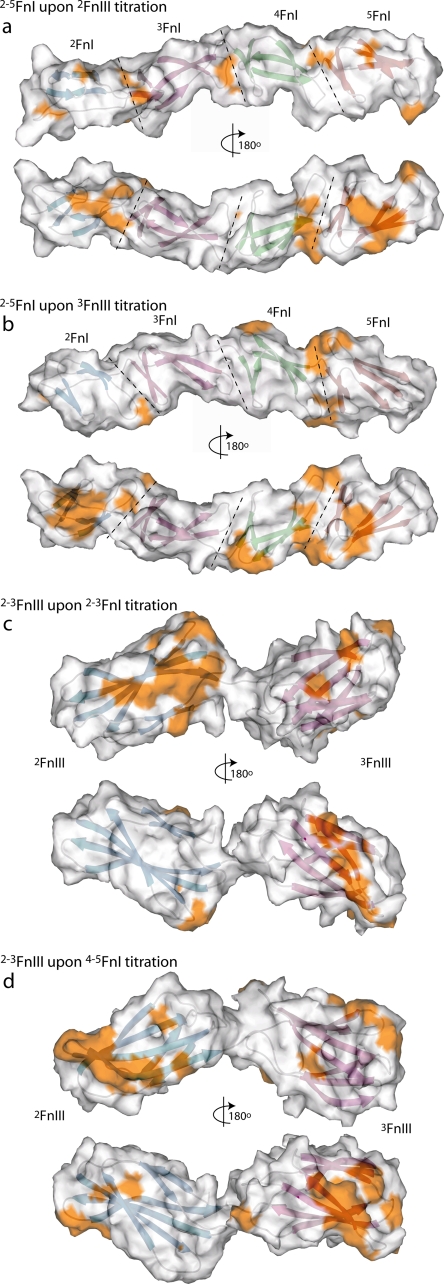

Mapping the chemical shift perturbations on the amino acid sequence (supplemental Fig. 5) and protein structure highlights the surfaces involved in the 2–5FnI and 2–3FnIII contacts (Fig. 3). 2FnIII perturbs both FnI fragments along the domain-domain (2FnI/3FnI, 4FnI/5FnI) interfaces, which probably reflects a small change in the preferred orientation within the domain pairs; similar changes in FnI pairs have been noted earlier as a result of changing local contacts (28). In addition, 5FnI is perturbed along the β-strand A/E interface and 2FnI along strand E. The pattern of perturbations by 3FnIII is similar to that of 2FnIII; however, the perturbation on 2FnI is more pronounced, and an additional interaction surface is present on 4FnI along the β-strand D/E loop. It is likely that this additional interaction surface accounts for the higher affinity of 3FnIII for 4–5FnI compared with 2FnIII (146 ± 9 μm versus 820 ± 70 μm Kd). Neither 2FnIII nor 3FnIII significantly affect domain 3FnI. Large scale mapping of the 2FnIII and 3FnIII interactions to a 2–5FnI model shows that the vast majority of perturbed areas localize on a single side of the model (Fig. 3, a and b).

FIGURE 3.

Interaction surfaces from chemical shift perturbations. a and b, molecular surface area representations of putative 2–5FnI models in two opposite orientations. The surfaces of residues with chemical shift perturbations in the 2FnIII (a) or 3FnIII (b) titrations greater than 1 S.D. from the average are colored in gold. The structures of domains 2FnI (blue), 3FnI (purple), 4FnI (green), and 5FnI (red) are shown, and the domain-domain interfaces are indicated by dashed lines. c and d, similar representations of a putative 2–3FnIII model upon 2–3FnI (c) or 4–5FnI (d) titration. 2FnIII is shown in blue and 3FnIII in purple.

Similar interface mapping of the 2–3FnI and 4–5FnI titrations on FnIII domains (Fig. 3, c and d) shows strong perturbations along 3FnIII β-strand D and the C-terminal end of strand E for both interactions, although this effect is more highly pronounced in the 4–5FnI titration. In contrast, perturbations on 2FnIII differ for the two interactions as 2–3FnI primarily affects the C terminus of β-strand G and the strand C/D loop (the part of the molecule proximal to 3FnIII), whereas 4–5FnI affects the N terminus of strand G and the strand F/G loop (the distal part of the molecule compared with 3FnIII). Inspection of the modeled 2–3FnIII indicates that, in both cases, the perturbed interfaces of 2FnIII and 3FnIII orient in opposite directions (Fig. 3, c and d); however, chains of FnIII domains are known to be prone to domain reorientation in solution (37).

The flexibility inherent in these multiple module fragments suggested that the observed interactions between adjacent domains could act cooperatively to enhance the binding affinity. 2–3FnIII can be easily produced, but we were initially unable to express 2–5FnI. Optimization of expression and purification procedures yielded only small amounts of this fragment (supplemental Fig. 6); these were, however, sufficient to test the effects of increasing fragment size. 15N-enriched 2–3FnI at low concentrations (20 μm) was titrated with 50 μm unenriched 2–3FnIII (supplemental Fig. 7); titrations of substantially higher amounts of 2–3FnIII produced broadened spectra with little signal (data not shown). Chemical shift perturbations were detected for both 2–3FnI and 4–5FnI residues, and comparisons of the chemical shift changes to those observed for smaller fragments indicated a fractional saturation of ∼25%. At the protein concentrations used, this fraction corresponds to an estimated Kd of 125 μm, equivalent to that of the 4–5FnI-3FnIII titration. Indeed, titrations of 2–5FnI with 3FnIII alone produced similar spectra to those with 2–3FnIII (supplemental Fig. 7), consistent with no cooperative 2FnIII binding. We interpret the 2–3FnI perturbations in the latter titration as occurring from a secondary binding event. 3FnIII would preferentially interact with the 4–5FnI pair in 2–5FnI, leading to an increase in the effective local 3FnIII concentration and a higher probability of a subsequent 2–3FnI-3FnIII interaction.

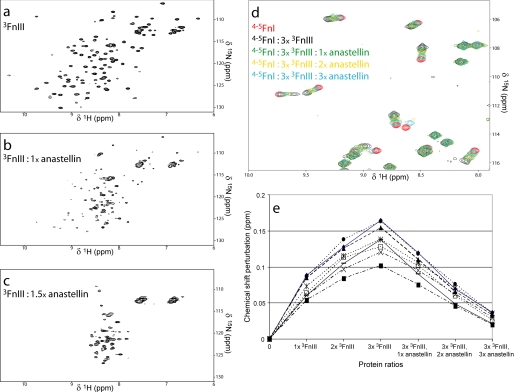

Anastellin Disrupts the 4–5FnI-3FnIII Interaction through 3FnIII Destabilization

Anastellin, a truncated form of 1FnIII, causes multimerization of plasma FN to a matrix-like form, superfibronectin (38). Structurally, anastellin resembles canonical type III folds (39) but displays properties different to those of 1FnIII, including direct binding to 3FnIII (5, 40). This interaction results in 3FnIII destabilization, which is important for superfibronectin formation (40). We monitored 3FnIII destabilization in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of this domain during titrations of unenriched anastellin at pH 7.0 (Fig. 4, a–c). Large spectral changes indicative of complete domain unfolding were observed at anastellin concentrations only slightly higher than equimolar, consistent with past reports (40). In contrast, similar titrations of anastellin with 2FnIII did not result in molecular interactions or 2FnIII destabilization (data not shown). To test the effect of anastellin on the 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction, we performed titrations of both components in 15N-enriched 4–5FnI (Fig. 4, d and e). The chemical shift perturbations caused by 3FnIII become smaller upon addition of anastellin, and resonance peaks tend to revert to those of uncomplexed 4–5FnI. Together, these data indicate that the 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction is disrupted in vitro by anastellin, probably because of 3FnIII destabilization; this disruption is potentially the initiation event for superfibronectin formation (38).

FIGURE 4.

Interaction of anastellin with 3FnIII. a–c, 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 3FnIII alone (a) or in the presence of equimolar (1×, b) or higher (1.5×, c) amounts of anastellin. d, detail from an overlay of HSQC spectra of 4–5FnI alone, in the presence of 3-fold excess 3FnIII or 3FnIII, and stoichiometric ratios of anastellin. e, extent of chemical shift perturbations on select 4–5FnI resonances upon 3FnIII or 3FnIII and anastellin titrations denoted as protein ratios with respect to 4–5FnI.

Disruption of the 4–5FnI-3FnIII Interaction Restores Motogenic Activity to Fn100kDa

The 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction is the strongest observed; thus, we attempted to disrupt it through amino acid substitutions to investigate its possible role in stabilizing long range order in Fn100kDa. Our results show that this interaction includes a large electrostatic component with substantially reduced affinity at higher ionic strength. The electrostatic and interaction surface maps of these proteins (Fig. 5, a and b) show a number of charged residues located at, or near, perturbed regions. Some of these were targeted for substitutions, including Arg-222, Arg-228, and Arg-237 in 4–5FnI, and Glu-850, Glu-855, and Asp-869 in 3FnIII. Titrations with proteins bearing these substitutions resulted in a range of affinities (Fig. 5f); the largest effect, of over 20-fold compared with the wild-type interaction, was observed for the R222A substitution (Fig. 5, c–e).

FIGURE 5.

Disruption of the 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction. Molecular surface area representation of 4–5FnI (a) and 3FnIII (b) colored by electrostatic potential (top) or showing residues strongly perturbed in the interaction in gold (bottom). The residues substituted are indicated. Details of overlays of the NMR spectra from the wild-type titration (c) and the 4–5FnI (R222A)-3FnIII titration (d) are shown. The fit of chemical shift change against protein concentration for this substitution is shown in e and all dissociation constants measured for substitutions in f.

Mutagenesis of Fn100kDa yielded no effect on stimulation of fibroblast migration for the R228A and R228A/E850A substitutions compared with the wild-type protein. In contrast, R222A and R222A/E850A in Fn100kDa produced motogenic activities with characteristic bell-shaped curves in migratory response versus protein concentration profiles (Fig. 1c and supplemental Fig. 8). Compared with Fn70kDa, these variants require ∼10 times more protein for maximal activity, which indicates that reversal of the conformational change responsible for occlusion of the stimulation activity is only partial.

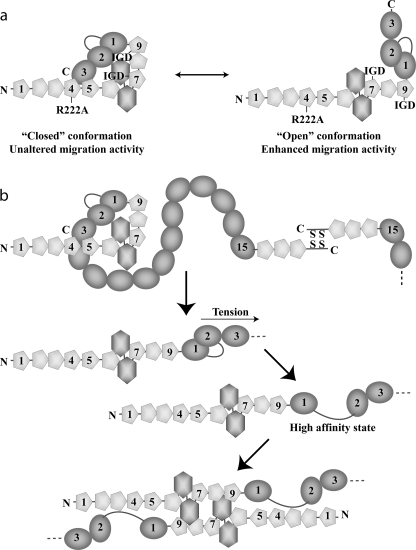

Exposure of motogenic activity sites in our Fn100kDa variants could be the result of change in structural state between a “closed” and “open” conformation (Fig. 6a), which may involve large differences in chain compaction. Such differences could be detectable in assays that report on the hydrodynamic properties of the macromolecule. Thus, we performed analytical size exclusion chromatography assays on Fn70kDa, Fn100kDa, and Fn100kDa R222A. As shown in Fig. 1d, wild-type Fn100kDa is retained longer in the size exclusion column compared with the R222A variant, indicating a more compact conformation, consistent with our hypothesis (Fig. 6a).

FIGURE 6.

Model of FN conformational transitions and fibrillogenesis. a, Fn100kDa possibly adopts a bent-back compact conformation (closed state, left) stabilized by intramolecular interactions, including 4–5FnI-3FnIII; a similar conformation is likely present in full-length FN. The motogenic activity sites on 7FnI and 9FnI are occluded while in this state, which is destabilized by the R222A substitution toward an alternative, open state (right). b, in FN, tension or fibril-promoting agents disrupt the 4–5FnI-3FnIII interaction, although further tension yields a high affinity state prone to oligomerization (5).

DISCUSSION

Long range FN structure and the nature of conformational transitions uncovering functionally cryptic sites have been the subject of much research and speculation. However, the large size of the molecule, its potential heterogeneity when purified from natural source, its sensitivity to changing environment, and difficulties with specific labeling have hindered description of the soluble plasma FN state. The system described here couples a sensitive biological assay that can detect functional changes, with FN variants that are relatively simple to produce and characterize. Furthermore, wild-type Fn100kDa displays activity properties similar to intact FN, which make it a good model system and an exciting new resource in the field of FN and matrix biology. Applications of fluorescent resonance energy transfer experiments (12, 13) in single molecule systems and coupled with computation are of particular interest.

Fn100kDa includes domains that can confer motogenic activity, but it does not stimulate fibroblast migration. We have shown here that the conformational transition responsible for this masking effect depends on the presence of a specific interaction between domains 3FnIII and 4–5FnI; this interaction is expected to occur within a single Fn100kDa molecule as this protein remains monomeric at concentrations much higher than those used in biological assays. It is likely that a similar intramolecular interaction is responsible for the lack of motogenic activity in full-length FN; however, interactions across the FN dimer cannot be excluded. Although we cannot construct a reliable structural model of Fn100kDa at this time, primarily because of flexible regions present in the molecule and the unknown conformation of intact GBD, our results suggest that the termini of Fn100kDa are in proximity creating an overall “bent-back” compact conformation we term the closed state (Fig. 6a). This state is likely to be stabilized by additional interactions acting in tandem; these interactions can be very weak, but if they are intramolecular the effective local concentration will be high enough to allow them to form readily. The importance of these interactions, particularly between 4–5FnI and 3FnIII, is illustrated by anastellin-mediated destabilization of 3FnIII and disruption of the interaction with 4–5FnI, the likely trigger for superfibronectin formation (38). The interactions of 2FnIII described here are less direct than those of 3FnIII in the FN fragments tested, but they could be important in the context of matrix formation where interaction heterogeneity and diversity may contribute to fibril growth.

In previous studies we showed an interaction between domains 1FnIII and 2FnIII (5). Disruption of this interaction by amino acid substitutions (a construct we called KADA) led to a high affinity (nanomolar) interaction between 1–2FnIII KADA and the FN N terminus (Fn30kDa, 1–5FnI); a similar result was recently shown by fluorescence (36). Technical limitations prevent direct characterization of the high affinity complex by NMR, as Fn30kDa-1–2FnIII KADA complexes tend to aggregate and precipitate (data not shown) under physiological conditions. However, a strong interaction is clearly present in the KADA mutant, and we believe that it will likely be dominant in conditions that favor fibrillogenesis, such as cell-generated tension or in the presence of fibril-promoting agents (38). Combining these earlier results with our present study allows us to create a more complete model of the initial fibrillogenesis steps (Fig. 6b). Soluble adult FN is likely to be held in compact form by inter-domain interactions, including those between 4–5FnI and 3FnIII. Tension, or fibril-promoting agents such as anastellin, will disrupt this initial conformation. Further application of force, or thermal fluctuations, could disrupt the 1FnIII-2FnIII complex creating a strong interaction with the FN N terminus. FN will then create oligomers that, in concert with the FN dimeric state, produce protofibrils and eventually the FN matrix. Interestingly, “handles” in soluble FN used by cells to initiate FN matrix formation have been mapped on Fn70kDa and 1FnIII (41, 42). It is possible that these handles permit unraveling of the FN100kDa compact state by cells in vivo.

The Fn100kDa closed conformation occludes motogenic activity sites on GBD as shown in our functional assays (Fig. 1). It is possible that this state also interferes with other identified GBD-related activities, such as collagen binding (29, 43, 44), attachment of pathogenic bacteria (45, 46), or transglutaminase-mediated cross-linking (47, 48). In contrast, removal of 1–3FnIII in MSF or Fn70kDa alters the conformation to expose sites of biological activity (Fig. 1 and Fig. 6a). MSF has been proposed to be a by-product of matrix metalloprotease cleavage of FN (49), possibly increasing the effect of metalloprotease activity on cell migration (50). However, MSF (10) and the Fn100kDa construct characterized here (26, 27) are also found as splicing variants of the FN gene. Therefore, migration stimulation and possibly other FN-mediated activities can be regulated at the level of mRNA processing. We have shown here that sites for these activities are always present in FN, but specific association interactions regulate their display; this mechanism renders FN activities sensitive to splicing variation by addition or removal of protein domains. We postulate that alternative splicing as well as mechanosensing could be functionally conserved methods for regulation of FN properties, as well as control of other multipotent biomolecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Soffe and Dr. Jonathan Boyd for assistance with the NMR instrumentation, Dr. Michèle C. Erat for critical reading of the manuscript, and Dr. Radu Aricescu for help with the HEK293T transient expression system. Funding for the Oxford Instruments 22.3 tesla (950 MHz 1H frequency) superconducting magnet was provided by the Wellcome Trust.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–8.

- FN

- fibronectin

- MSF

- migration stimulation factor

- FnI/II/III

- FN type I/II/III domains

- Fn30kDa

- fibronectin domains 1FnI-5FnI

- Fn70kDa

- fibronectin domains 1FnI-9FnI

- Fn100kDa

- fibronectin domains 1FnI-3FnIII

- GBD

- fibronectin gelatin binding domain

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vakonakis I., Campbell I. D. ( 2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 578– 583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leahy D. J., Aukhil I., Erickson H. P. ( 1996) Cell 84, 155– 164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickford A. R., Smith S. P., Staunton D., Boyd J., Campbell I. D. ( 2001) EMBO J. 20, 1519– 1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingham R. J., Rudiño-Piñera E., Meenan N. A., Schwarz-Linek U., Turkenburg J. P., Höök M., Garman E. F., Potts J. R. ( 2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 12254– 12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vakonakis I., Staunton D., Rooney L. M., Campbell I. D. ( 2007) EMBO J. 26, 2575– 2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morla A., Ruoslahti E. ( 1992) J. Cell Biol. 118, 421– 429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hocking D. C., Sottile J., McKeown-Longo P. J. ( 1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19183– 19187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Huff S., Litvinovich S. V. ( 1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 1718– 1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Erickson H. P. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28132– 28135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schor S. L., Ellis I. R., Jones S. J., Baillie R., Seneviratne K., Clausen J., Motegi K., Vojtesek B., Kankova K., Furrie E., Sales M. J., Schor A. M., Kay R. A. ( 2003) Cancer Res. 63, 8827– 8836 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ugarova T. P., Zamarron C., Veklich Y., Bowditch R. D., Ginsberg M. H., Weisel J. W., Plow E. F. ( 1995) Biochemistry 34, 4457– 4466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai C. S., Wolff C. E., Novello D., Griffone L., Cuniberti C., Molina F., Rocco M. ( 1993) J. Mol. Biol. 230, 625– 640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff C., Lai C. S. ( 1988) Biochemistry 27, 3483– 3487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelea V., Nakano Y., Kaartinen M. T. ( 2008) Protein J. 27, 223– 233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjöberg B., Pap S., Osterlund E., Osterlund K., Vuento M., Kjems J. ( 1987) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 255, 347– 353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuillard L., Roux B., Miller A. ( 1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 191, 333– 336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelta J., Berry H., Fadda G. C., Pauthe E., Lairez D. ( 2000) Biochemistry 39, 5146– 5154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvinovich S. V., Ingham K. C. ( 1995) J. Mol. Biol. 248, 611– 626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzfaden C., Grant R. P., Mardon H. J., Campbell I. D. ( 1997) J. Mol. Biol. 265, 565– 579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altroff H., Schlinkert R., van der Walle C. F., Bernini A., Campbell I. D., Werner J. M., Mardon H. J. ( 2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55995– 56003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schor S. L., Schor A. M., Grey A. M., Rushton G. ( 1988) J. Cell Sci. 90, 391– 399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houard X., Germain S., Gervais M., Michaud A., van den Brûle F., Foidart J. M., Noël A., Monnot C., Corvol P. ( 2005) Int. J. Cancer 116, 378– 384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schor S. L., Ellis I., Dolman C., Banyard J., Humphries M. J., Mosher D. F., Grey A. M., Mould A. P., Sottile J., Schor A. M. ( 1996) J. Cell Sci. 109, 2581– 2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millard C. J., Ellis I. R., Pickford A. R., Schor A. M., Schor S. L., Campbell I. D. ( 2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35530– 35535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schor S. L., Ellis I., Banyard J., Schor A. M. ( 1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 3879– 3888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Q., Liu X., Collodi P. ( 2001) Exp. Cell Res. 268, 211– 219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X., Zhao Q., Collodi P. ( 2003) Matrix Biol. 22, 393– 396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudiño-Piñera E., Ravelli R. B., Sheldrick G. M., Nanao M. H., Korostelev V. V., Werner J. M., Schwarz-Linek U., Potts J. R., Garman E. F. ( 2007) J. Mol. Biol. 368, 833– 844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erat M. C., Slatter D. A., Lowe E. D., Millard C. J., Farndale R. W., Campbell I. D., Vakonakis I. ( 2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 4195– 4200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vakonakis I., Langenhan T., Prömel S., Russ A., Campbell I. D. ( 2008) Structure 16, 944– 953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aricescu A. R., Lu W., Jones E. Y. ( 2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 1243– 1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schor S. L. ( 1980) J. Cell Sci. 41, 159– 175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett-Lovsey R. M., Herbert A. D., Sternberg M. J., Kelley L. A. ( 2008) Proteins 70, 611– 625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander S. S., Jr., Colonna G., Edelhoch H. ( 1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 1501– 1505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schreiber G. ( 2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 41– 47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karuri N. W., Lin Z., Rye H. S., Schwarzbauer J. E. ( 2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3445– 3452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Copié V., Tomita Y., Akiyama S. K., Aota S., Yamada K. M., Venable R. M., Pastor R. W., Krueger S., Torchia D. A. ( 1998) J. Mol. Biol. 277, 663– 682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morla A., Zhang Z., Ruoslahti E. ( 1994) Nature 367, 193– 196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briknarová K., Akerman M. E., Hoyt D. W., Ruoslahti E., Ely K. R. ( 2003) J. Mol. Biol. 332, 205– 215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohashi T., Erickson H. P. ( 2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39143– 39151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomasini-Johansson B. R., Annis D. S., Mosher D. F. ( 2006) Matrix Biol. 25, 282– 293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J., Bae E., Zhang Q., Annis D. S., Erickson H. P., Mosher D. F. ( 2009) PLoS ONE 4, e4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Isaacs B. S. ( 1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4624– 4628 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Migliorini M. ( 2002) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 407, 217– 223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozeri V., Tovi A., Burstein I., Natanson-Yaron S., Caparon M. G., Yamada K. M., Akiyama S. K., Vlodavsky I., Hanski E. ( 1996) EMBO J. 15, 989– 998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talay S. R., Zock A., Rohde M., Molinari G., Oggioni M., Pozzi G., Guzman C. A., Chhatwal G. S. ( 2000) Cell. Microbiol. 2, 521– 535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akimov S. S., Belkin A. M. ( 2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 2989– 3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radek J. T., Jeong J. M., Murthy S. N., Ingham K. C., Lorand L. ( 1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 3152– 3156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mott J. D., Werb Z. ( 2004) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 558– 564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaman M. H., Matsudaira P., Lauffenburger D. A. ( 2007) Ann. Biomed. Eng. 35, 91– 100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.