Abstract

Context: Both GH deficiency (GHD) and GH excess are associated with a decreased quality of life. However, it is unknown whether patients with GHD after treatment for acromegaly have a poorer quality of life than those with normal GH levels after cure of acromegaly.

Objective: The aim of the study was to determine whether patients with GHD and prior acromegaly have a poorer quality of life than those with GH sufficiency after cure of acromegaly.

Design and Setting: We conducted a cross-sectional study in a General Clinical Research Center.

Study Participants: Forty-five patients with prior acromegaly participated: 26 with GHD and 19 with GH sufficiency.

Intervention: There were no interventions.

Main Outcome Measures: We evaluated quality of life, as measured by 1) the Quality of Life Adult Growth Hormone Deficiency Assessment (QoL-AGHDA); 2) the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36); and 3) the Symptom Questionnaire.

Results: Mean scores on all subscales of all questionnaires, except for the anger/hostility and anxiety subscales of the Symptom Questionnaire, showed significantly impaired quality of life in the GH-deficient group compared with the GH-sufficient group. Peak GH levels after GHRH-arginine stimulation levels were inversely associated with QoL-AGHDA scale scores (R = −0.53; P = 0.0005) and the Symptom Questionnaire Depression subscale scores (R = −0.35; P = 0.031) and positively associated with most SF-36 subscale scores.

Conclusions: Our data are the first to demonstrate a reduced quality of life in patients who develop GHD after cure of acromegaly compared to those who are GH sufficient. Further studies are warranted to determine whether GH replacement would improve quality of life for patients with GHD after cure from acromegaly.

Reduced quality of life is present in patients who develop growth hormone deficiency after cure of acromegaly compared to those who are GH-sufficient.

GH deficiency (GHD) is associated with a decreased quality of life in patients with hypopituitarism due to organic hypothalamic/pituitary disease from causes other than acromegaly (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Quality of life is also diminished in patients with GH excess (acromegaly) (6,7,9,10,11,12). The goal of treatment for acromegaly is normalization of endogenous GH levels and/or IGF-I levels and reversal of the associated metabolic complications. Although quality of life has been shown to improve after cure of acromegaly (11,13,14), studies generally show that it does not return to normal (15,16,17,18). GHD is a common consequence of the treatment of pituitary tumors, including those secreting GH, particularly as a result of radiation therapy (19,20,21,22). Little is known about whether patients with GHD after treatment for acromegaly experience a poorer quality of life than those who have normal GH levels after cure.

Therefore, we studied 45 patients who had been cured from acromegaly to determine whether GHD conferred a poorer quality of life than GH sufficiency in this population.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

A total of 45 subjects with documented biochemical remission of acromegaly were recruited from the Massachusetts General Hospital Neuroendocrine Clinical Center, by referring endocrinologists, and through advertising. All subjects had been treated by surgery or radiation therapy at least 6 months before study entry and demonstrated biochemical cure, defined as GH suppression to less than 1 ng/ml during an oral glucose tolerance test and/or normal serum IGF-I for age. Subjects were excluded from participation if they were receiving somatostatin analogs, dopamine agonists, or GH receptor antagonists. Additional exclusion criteria included unstable cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes mellitus, cancer, and pregnancy, or breastfeeding within 1 yr before study enrollment. One subject had received GH therapy previously and for less than 1 yr, discontinuing it more than 3 yr before study enrollment. Subjects with hypopituitarism were required to have been receiving stable hormone replacement therapy doses for at least 3 months before enrollment. Subjects with adrenal insufficiency were all receiving 4–5 mg of prednisone or 15–30 mg of hydrocortisone daily. The range of doses of testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men was 5 to 7.5 g of a transdermal gel, except for one male subject who was receiving im testosterone esters at a dose of 200 mg every 2 wk. All but two (one of whom was receiving transdermal estradiol and the other oral conjugated equine estrogens) of the women receiving gonadal steroids were receiving oral contraceptives. Diagnosis of GHD was defined as a peak GH level of less than 5 ng/ml on GHRH-arginine stimulation testing, or an IGF-I level more than 2 sd values below the age-specific normal range in the presence of at least three anterior pituitary deficiencies (n = 5) (23). Subjects were categorized as GH-sufficient based on peak GH levels above 9 ng/ml on a GHRH-arginine stimulation test (24,25). Two additional subjects tested did not qualify as GH-deficient or GH-sufficient (peak GH levels ≥5 ng/ml or ≤9 ng/ml) and were included for analyses in which data were used as continuous variables. One was a 45-yr-old female, and the other was a 31-yr-old male. GHRH-arginine testing was performed using the standard protocol for diagnosis of GHD in adults with hypopituitarism (GHRH 1 μg/kg plus arginine 0.5 g/kg to a maximum of 30 g were administered iv, and GH levels were measured at baseline and every 30 min for 2 h) (26).

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare, Inc. Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Protocol

All data were collected during two outpatient visits at the Massachusetts General Hospital General Clinical Research Center. The initial screening visit included a GHRH-arginine stimulation test. The subsequent baseline visit (for qualifying subjects) included a fasting IGF-I level and administration of the following questionnaires to assess quality of life.

Quality of life assessment of growth hormone deficiency in adults (QoL-AGHDA)

The QoL-AGHDA is a disease-generated questionnaire developed to measure quality of life in adults with GHD (27,28) based on 36 in-depth interviews with GH-deficient patients. It consists of 25 statements with “yes/no” responses. The statements assess energy, physical and mental drive, concentration/memory, personal relationships, social life, emotions, and cognition, and are based on the assumption that quality of life is determined by the degree to which human needs are met. Higher scores indicate a poorer quality of life.

Symptom questionnaire

The Symptom Questionnaire is a 92-item questionnaire assessing four scales: 1) anxiety, 2) depression, 3) somatic symptoms, and 4) anger/hostility (29). It has been validated and widely used in clinical studies since it was developed in 1976 (30,31,32,33,34). Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. Domain scores between 1 and 2 sd values above the mean for healthy controls indicate moderate distress, and scores greater than 2 sd values above the mean suggest severe distress or psychopathology (29).

Short-form health survey (SF-36)

The SF-36 is a well-validated self-administered questionnaire consisting of 36 items that address physical and psychological well-being during the preceding 4 wk (35,36). Questions and statements are answered with either “yes/no” responses or scaled responses ranging from three options (“yes, limited a lot”; “yes, limited a little”; “no, not limited at all”) to six options (“all of the time”; “most of the time”; “a good bit of the time”; “some of the time”; “a little of the time”; “none of the time”). The following quality of life modalities are assessed: 1) physical functioning, 2) role limitations due to physical functioning, 3) general health perception, 4) pain, 5) vitality, 6) emotional well-being, 7) role limitations due to emotional health, and 8) social functioning. Scores are represented on a 0–100 scale. Higher scores indicate a better quality of life.

Assays

Serum IGF-I levels were measured using the Immulite 2000 automated immunoanalyzer (Diagnostic Products Corp., Inc., Los Angeles, CA), with a solid-phase, enzyme-labeled, chemiluminescent immunometric assay, with an interassay coefficient of variation (cv) of 3.7% (at an IGF-I level of 75 ng/ml) to 4.2% (at an IGF-I level of 169 ng/ml). Serum GH levels were measured by a chemiluminescent immunometric assay (Nichols Institute Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, CA) with an intraassay cv of less than or equal to 5.4% and a sensitivity of 0.02 ng/ml until July 12, 2005. Subsequently, serum GH levels were measured using an immunoradiometric assay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX), with a minimum detection limit of 0.01 ng/ml, an intraassay cv of 3.1–5.4%, and an interassay cv of 5.9–11.5%. We performed univariate correlational and agreement analyses between the two GH assays, with n = 12 and a range of 0.97 to 27.9 ng/ml. The R2 was 0.98, the slope was 1.083 with an intercept of −0.4457, and the average bias was 8.4%.

Statistical analysis

JMP Statistical Discoveries (version 5.0.1.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and means were compared with ANOVA for normally distributed variables. All variables not normally distributed were compared using the Wilcoxon test. The Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences between categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate regression models were constructed to determine predictors of quality of life. The square root was taken of all variables that were not normally distributed before they were entered into regression models. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value <0.05. All results are expressed as mean ± sd.

Results

Clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Quality of life data are shown in Table 2 and Figs. 1 through 4. Subjects with GHD had a significantly poorer quality of life, as measured by all scales and subscales except the Anxiety and Anger/Hostility subscales of the Symptom Questionnaire, and these differences remained significant after controlling for potentially confounding factors that differed between the groups (as shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Demographics (mean ± sd) | GH deficient (n = 26) | GH sufficient (n = 19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 47.0 ± 11.9 | 45.5 ± 12.1 | NS |

| Sex (males/females) | 10/16 | 6/13 | NS |

| IGF-I (ng/ml) | 90.3 ± 44.7 | 141.3 ± 62.9 | 0.0019 |

| IGF-I sd score | −2.0 ± 0.6 | −1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.0018 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.9 ± 6.7 | 27.1 ± 4.2 | 0.0236 |

| History of TSS, n (%) | 24 (92) | 19 (100) | NS |

| Time since TSS (months) | 134.3 ± 77.1 | 64.6 ± 58.3 | 0.0013 |

| History of XRT, n (%) | 22 (85) | 4 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Time since XRT (months) | 163.8 ± 107.0 | 72.0 ± 38.0 | NS |

| History of GH-lowering medication | 5 (45) | 5 (26) | NS |

| Time since diagnosis of acromegaly | 163.7 ± 104.9 | 70.0 ± 60.0 | NS |

| Age at diagnosis of acromegaly (yr) | 33.4 ± 11.4 | 39.7 ± 13.1 | NS |

| Time since cure (months) | 92.1 ± 81.0 | 58.0 ± 53.3 | NS |

| No. of pituitary hormone deficiencies | |||

| 0 | 0 | 16 (84) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 1 (4) | 2 (11) | NS |

| 2 | 4 (15) | 0 | NS |

| 3 | 9 (35) | 0 | 0.0035 |

| 4 | 8 (31) | 1 (5) | 0.037 |

| 5 | 4 (15) | 0 | NS |

| Central ACTH insufficiency | 12 (46) | 1 (5) | 0.0027 |

| Central TSH deficiency | 20 (77) | 2 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Free T4 (ng/dl) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | NS |

| T3 (ng/dl) | 127 ± 38 | 124 ± 32 | NS |

| Male hypogonadism, n (%) | 8 (80) | 1 (17) | 0.0245 |

| Testosterone replacement | 7 (87.5) | 0 | NS |

| Menopause, n (%) | 3 (19) | 5 (38) | NS |

| Estrogen replacement | 1 (33) | 0 | NS |

| Female 2° hypogonadism, n (%) | 13 (81) | 2 (15) | 0.0006 |

| Estrogen replacement | 9 (69) | 2 (100) | NS |

| Current tobacco use, n (%) | 3 (12) | 4 (21) | NS |

| Antidepressant use | 8 (31) | 2 (11) | NS |

| Antihypertensive use | 6 (23) | 9 (47) | NS |

XRT, Radiation therapy; TSS, transsphenoidal surgery; 2°, secondary; NS, not significant.

Table 2.

Quality of life

| GH deficient (n = 26) | % scoring below 25% of normal | GH sufficient (n = 19) | % scoring below 25% of normal | P value | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests in which higher scores reflect poorer QOL | ||||||

| QoL-AGHDA | 8.6 ± 5.5 | 2.7 ± 3.4 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | ||

| Symptom questionnaire | ||||||

| Anxiety | 6.4 ± 5.4 | 3.3 ± 2.4 | NS | NS | ||

| Depression | 5.0 ± 4.8 | 1.6 ± 2.0 | 0.007 | 0.005 | ||

| Anger/hostility | 3.0 ± 4.3 | 2.7 ± 2.8 | NS | NS | ||

| Somatic | 7.8 ± 4.8 | 5.0 ± 3.7 | 0.049 | NS | ||

| Tests in which higher scores reflect better QOL | ||||||

| SF-36 | ||||||

| Physical functioning | 72.0 ± 22.1 | 32 | 94.4 ± 7.5 | 5 | 0.0006 | 0.003 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 68.0 ± 38.5 | 8 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 5 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Bodily pain | 64.9 ± 30.0 | 44 | 84.6 ± 13.1 | 5 | 0.028 | NS |

| General health | 55.2 ± 22.9 | 56 | 78.3 ± 16.6 | 11 | 0.0007 | 0.034 |

| Vitality | 38.4 ± 22.8 | 52 | 66.8 ± 16.3 | 32 | <0.0001 | 0.002 |

| Social functioning | 74.5 ± 20.6 | 44 | 95.8 ± 8.6 | 5 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 |

| Role limitations due to emotional health | 72.0 ± 36.9 | 16 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 5 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Mental health | 66.7 ± 19.8 | 40 | 78.2 ± 12.1 | 11 | 0.032 | 0.012 |

Values are reported as mean ± sem. NS, Not significant; QOL, quality of life.

P value after controlling for BMI, history of radiotherapy, time since surgery, and ACTH deficiency.

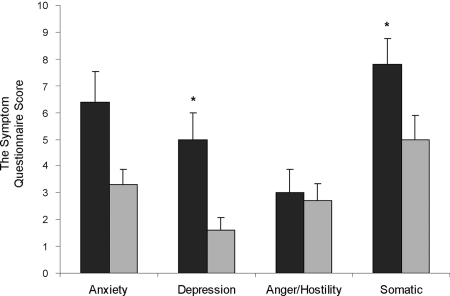

Figure 1.

Mean (±sem) AGHDA scores were higher in the GH-deficient than GH-sufficient subjects with prior acromegaly. Black bar, GH-deficient; gray bar, GH-sufficient. *, P = 0.0002. Higher scores on the AGHDA indicate poorer quality of life.

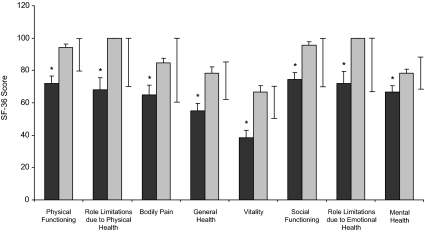

Figure 2.

Mean (±sem) Symptom Questionnaire scores were higher for all subscales, except for anxiety and anger/hostility, in the GH-deficient than GH-sufficient subjects with prior acromegaly. Black bars, GH-deficient; gray bars, GH-sufficient. *, P < 0.05. Higher scores on the Symptom Questionnaire indicate poorer quality of life.

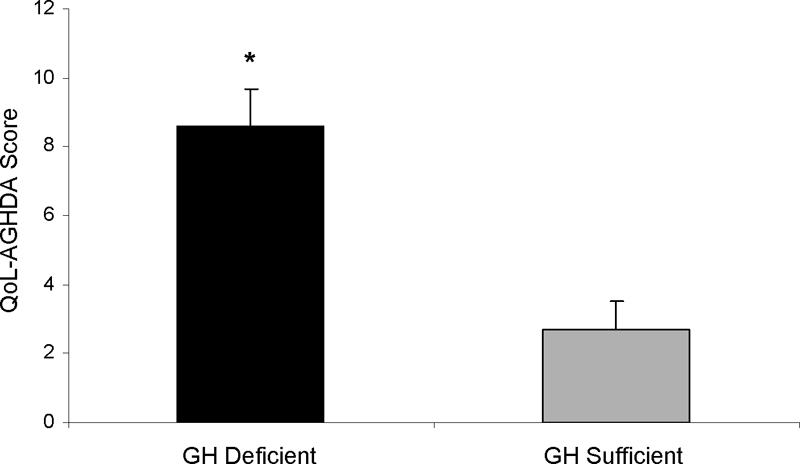

Figure 3.

Mean (±sem) SF-36 scores were lower for all subscales in the GH-deficient than GH-sufficient subjects with prior acromegaly. Black bars, GH-deficient; gray bars, GH-sufficient; whiskers, normal ranges. *, P < 0.03. Lower scores on the SF-36 questionnaire indicate poorer quality of life.

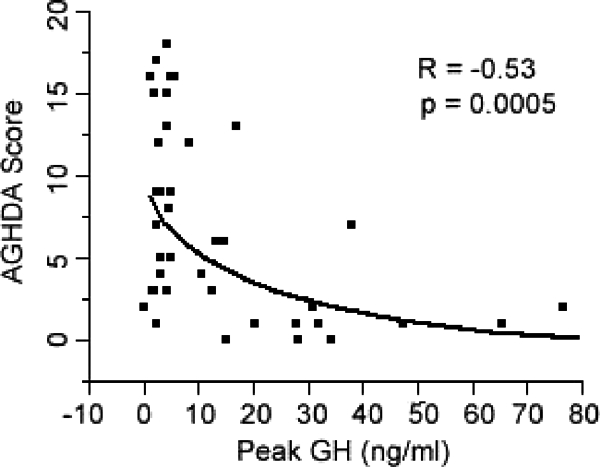

Figure 4.

Peak GH levels after GHRH-arginine stimulation levels were inversely associated with QoL-AGHDA scale scores. Higher scores on the AGHDA indicate poorer quality of life.

The percentage of GH-deficient subjects scoring more than 2 sd values above the mean on the Depression subscale was higher than that of the GH-sufficient group (25% GH-deficient vs. 0% GH-sufficient; P = 0.022), and there was a trend toward a higher percentage of GH-deficient subjects scoring more than 2 sd values above the mean on the anxiety subscale (17% GH-deficient vs. 0% GH-sufficient; P = 0.086). There was no significant difference between percentages of GH-deficient and GH-sufficient subjects who scored more than 2 sd values above the mean on the Anger/Hostility (8% GH-deficient vs. 0% GH-sufficient; P = 0.32) or Somatic symptom (29% GH-deficient vs. 11% GH-sufficient; P = 0.13) subscales.

There were no significant differences in mean quality of life scores between males and females for any scales or subscales within the GH-deficient group. There was an inverse association of the Anger/Hostility symptom subscale with age (R = −0.53; P = 0.0004), such that, in general, older subjects reported higher levels of anger and hostility. No other subscales correlated with age. Previous radiotherapy was a negative predictor of the vitality subscale of the SF-36 questionnaire (P = 0.02) but of no other questionnaire or questionnaire subscale. It was no longer a significant predictor of the SF-36 vitality subscale after controlling for the presence or absence of GHD (P = 0.69).

Peak GH levels after GHRH-arginine stimulation levels were inversely associated with QoL-AGHDA scale scores (R = −0.53; P = 0.0005) (Fig. 4). All subscale scores of the SF-36 were associated with GHRH-arginine stimulation peak GH levels except for Bodily Pain and for Role Limitations due to Emotional Health (Physical Functioning, R = 0.43, P = 0.006; Role Limitations due to Physical Health, R = 0.37, P = 0.023; Bodily Pain, R = 0.26, P=0.11; General Health: R = 0.42, P = 0.008; Vitality, R = 0.46, P = 0.003; Social Functioning, R = 0.36, P = 0.023; Role Limitations due to Emotional Health, R = 0.31, P = 0.05; Mental Health, R = 0.32, P = 0.041). Depression Symptom Questionnaire subscale scores were inversely associated with peak GH after GHRH-arginine stimulation (R = −0.35; P = 0.031); other Symptom Questionnaire subscale scores were not associated with peak GH levels.

IGF-I sd scores were significantly associated with General Health (R = 0.46; P = 0.002), and Vitality SF-36 subscale scores (R = 0.40; P = 0.009), but not with any other SF-36 subscale scores, QoL-AGHDA, or Symptom Questionnaire subscale scores.

Discussion

To our knowledge, these are the first data to demonstrate a reduced quality of life in patients who develop GHD after cure of acromegaly compared with those who are GH-sufficient. We report diminished quality of life in such patients using a quality-of-life questionnaire developed specifically to detect symptoms associated with GHD and also using questionnaires that have been validated in patients with a wide range of illnesses. Our data suggest that avoiding GHD in patients after cure of acromegaly may be important and raise the question of whether GH replacement would benefit such patients despite increased prior exposure to GH.

A study using the KIMS database showed that patients with GHD after treatment for acromegaly had a similar (in males) or poorer (in females) quality of life than patients with GHD from other pituitary causes, as measured by the AGHDA (37). Our results are consistent with the notion that patients with GHD after cure of acromegaly may experience impaired quality of life, although we did not detect a gender-specific difference in magnitude. Our comparison with GH-sufficient patients who also had prior acromegaly demonstrates that impaired quality of life in patients with GHD and prior acromegaly is not due primarily to the residual effects of the acromegaly itself. This is an important point because acromegaly itself is associated with an impaired quality of life, and although cure has been shown to be accompanied by improvements in quality of life, most studies do not demonstrate recovery to normal (10,11,13,14,15,16,18,38). In another study, a U-shaped relationship between glucose-suppressed GH levels and quality of life scores was observed in a study cohort that included patients with active and cured acromegaly, such that patients with nadir values between 0.3 and 1.0 ng/ml had better quality of life scores than those with lower or higher values (18). Although the presence of GHD was not formally assessed in the study, the results support the concept that low GH levels may confer an impaired quality of life, consistent with our data.

An important question is whether the magnitude of difference in quality of life subscales between GH-deficient and GH-sufficient patients with prior acromegaly is clinically important. Comparisons with data from other GH-deficient populations and from other groups of patients with known impaired quality of life suggest that the differences observed in our study are clinically relevant in addition to being statistically significant. Data comparing quality of life measures between patients with GHD due to hypothalamic/pituitary lesions other than acromegaly and healthy controls reveal a similar magnitude of difference as in our study (4,29,38,39). SF-36 subscale scores for our population of GH-deficient subjects are similar to those of subjects with type II diabetes (n = 541) and recent acute myocardial infarction (n = 107) and are significantly worse than in subjects with hypertension (n = 2089) and other minor medical conditions (35,36). Moreover, studies of the effects of antidepressant therapy on quality of life measures have demonstrated changes that are of similar magnitude to those we have observed between GH-deficient and GH-sufficient patients with prior acromegaly (32,33,39). For example, an 8-wk study of the effects of fluoxetine on somatic symptoms in 384 subjects with major depressive disorder demonstrated a mean improvement in the Symptom Questionnaire Somatic symptom subscale from 9.6 ± 5.6 to 6.1 ± 5.3 (32), similar to the difference between groups in our study. Therefore, we conclude that the diminution in quality of life in GH-deficient patients with prior acromegaly detected by this study is likely to be clinically relevant.

Limitations of our study include the fact that a cross-sectional study cannot determine causality and that there were a number of possible confounders, including the potential effects of body mass index (BMI), radiation therapy, and hormone deficiency and replacement regimens. We addressed this latter issue by controlling for parameters that differed between the groups, but further studies are warranted. We found that, in general, the impairment in quality of life in the GH-deficient subjects could not be attributed to differences in BMI, radiation therapy, or hormone deficiencies. This is in contrast to published studies on quality of life in subjects after treatment for acromegaly, in which radiation therapy has been shown to be a significant independent predictor of diminished quality of life (9,15,18,40). However, most of these studies included patients with active, controlled, and cured disease, without differentiating GH status. Therefore, it is possible that at least some of the adverse effects reported may have in fact been attributable to GHD, not radiation therapy as surmised. Further studies are needed to clarify causality. In addition, the GHRH-arginine and IGF-I cutoffs used have not been validated specifically in patients who have a history of acromegaly. GH levels are also laboratory dependent, and GHD is BMI dependent (41,42,43). Fundamentally, GH status is a continuum, and cutoffs by their nature are not absolute but instead are arbitrary. To address these issues, we included analyses using peak GH as a continuous variable and also controlled our analyses for BMI. In addition, the relatively small sample size of the GH-sufficient and GH-insufficient groups and subgroups does not allow us to completely rule out confounders such as time since diagnosis of acromegaly, time since cure of acromegaly, or time since radiation therapy, the means of which appeared different but did not differ statistically and may also have limited our ability to detect other differences between the groups. For example, we cannot rule out a difference between the GH-deficient and GH-sufficient groups in anxiety symptom severity; the mean score in the GH-deficient group was nearly double that in the GH-sufficient group, but they did not differ statistically. Another potential confounder that we cannot entirely exclude as a cause of our findings is the influence of other pituitary hormone deficiencies and replacement therapy regimens for them. Finally, we were careful to limit the number of variables we entered into the models, i.e. the number of variables for which we controlled simultaneously. However, a higher ratio of study subjects to variables entered into the multivariate models would have been preferable, and a larger total “n” would have allowed us to control for a greater number of variables. It should also be noted that we cannot conclude from our data that GHD is the only cause of diminished quality of life in this group of patients, only that it may be an important contributing factor.

We have demonstrated that GHD in patients with prior acromegaly is associated with a diminished quality of life and that the magnitude of mean changes are likely clinically relevant. Before the development of pharmacological therapy for acromegaly over the last decade, enabling reduction of GH and/or IGF-I levels into the normal range in most patients with acromegaly, the focus of research and treatment for this disease was on diminishing exposure to supraphysiological GH and IGF-I levels. There are few data regarding the optimal level of posttreatment GH or IGF-I levels in patients with controlled or cured acromegaly. Radiation and pegvisomant therapy can result in GHD, and both surgery and somatostatin analog therapy can have similar effects. GHD due to organic hypothalamic or pituitary disease other than acromegaly has been shown to be associated with a diminished quality of life, and randomized, placebo-controlled studies (44,45,46,47), as well as numerous open-label trials and retrospective studies have demonstrated improvements in these measures with GH replacement therapy (1,2,7,37,48,49,50,51,52,53). The diagnosis of GHD is not often pursued in patients with acromegaly, and, when discovered, replacement is often not considered because of concerns about cumulative GH exposure. One retrospective study suggested that quality of life in patients with GHD after cure of acromegaly did not benefit from GH therapy; this was in contrast to patients with GHD due to other organic etiologies (37). Our data suggest that randomized, placebo-controlled studies are needed to investigate the effects of GH replacement therapy on quality of life in this particular population.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nurses of the Massachusetts General Hospital General Clinical Research Center and Clinical Translational Science Center, and the patients who participated in the study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MO1 RB01066 and UL1 RR025758, an investigator initiated grant from Pfizer Inc. and by Leo and Laurie Guthart.

Disclosure Summary: A.K. received funding for this investigator-initiated study from Pfizer Inc. B.B. consults for Pfizer Inc. No other authors have any conflicts to declare.

First Published Online April 14, 2009

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; cv, coefficient of variation; GHD, GH deficiency.

References

- Blum WF, Shavrikova EP, Edwards DJ, Rosilio M, Hartman ML, Marín F, Valle D, van der Lely AJ, Attanasio AF, Strasburger CJ, Henrich G, Herschbach P 2003 Decreased quality of life in adult patients with growth hormone deficiency compared with general populations using the new, validated, self-weighted questionnaire, questions on life satisfaction hypopituitarism module. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:4158–4167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist FJ, Murray RD, Shalet SM 2002 The effect of long-term untreated growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and 9 years of GH replacement on the quality of life (QoL) of GH-deficient adults. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 57:363–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Wiren L, Wilhelmsen L, Wiklund I, Bengtsson BA 1994 Decreased psychological well-being in adult patients with growth hormone deficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 40:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badia X, Lucas A, Sanmarti A, Roset M, Ulied A 1998 One-year follow-up of quality of life in adults with untreated growth hormone deficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 49:765–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork S, Jonsson B, Westphal O, Levin JE 1989 Quality of life of adults with growth hormone deficiency: a controlled study. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 356:55–59; discussion 60, 73–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SM, Badia X 2007 Quality of life in growth hormone deficiency and acromegaly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 36:221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse LJ, Mukherjee A, Shalet SM, Ezzat S 2006 The influence of growth hormone status on physical impairments, functional limitations, and health-related quality of life in adults. Endocr Rev 27:287–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGauley GA 1989 Quality of life assessment before and after growth hormone treatment in adults with growth hormone deficiency. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 356:70–72; discussion 73–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles SV, Prieto L, Badia X, Shalet SM, Webb SM, Trainer PJ 2005 Quality of life (QOL) in patients with acromegaly is severely impaired. Use of a novel measure of QOL: acromegaly quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3337–3341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SM 2006 Quality of life in acromegaly. Neuroendocrinology 83:224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepp R, Everts R, Stettler C, Fischli S, Allemann S, Webb SM, Christ ER 2005 Assessment of quality of life in patients with uncontrolled vs. controlled acromegaly using the Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) [Erratum (2005) 63:238] 63:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantanetti P, Sonino N, Arnaldi G, Boscaro M 2002 Self image and quality of life in acromegaly. Pituitary 5:17–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisley AN, Rowles SV, Roberts ME, Webb SM, Badia X, Prieto L, Shalet SM, Trainer PJ 2007 Treatment of acromegaly improves quality of life, measured by AcroQol. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 67:358–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L, Vezzosi D, Bennet A, Caron P 2008 Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: control of GH/IGF-I excess improves psychological subscale appearance. Eur J Endocrinol 158:305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biermasz NR, van Thiel SW, Pereira AM, Hoftijzer HC, van Hemert AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F 2004 Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5369–5376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F 2005 Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2731–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Klaauw AA, Kars M, Biermasz NR, Roelfsema F, Dekkers OM, Corssmit EP, van Aken MO, Havekes B, Pereira AM, Pijl H, Smit JW, Romijn JA 2008 Disease-specific impairments in quality of life during long-term follow-up of patients with different pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69:775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen-Mäkelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H, Markkanen H, Välimäki MJ, Löyttyniemi E, Niskanen L, Reunanen A, Stenman UH 2006 Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3891–3896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castinetti F, Morange I, Dufour H, Regis J, Brue T 2009 Radiotherapy and radiosurgery in acromegaly. Pituitary 12:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzy KH, Pezzoli SS, Thorner MO, Shalet SM 2007 Cranial irradiation and growth hormone neurosecretory dysfunction: a critical appraisal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1666–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzy KH, Shalet SM 2003 Radiation-induced growth hormone deficiency. Horm Res 59(Suppl 1):1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toogood AA 2004 Endocrine consequences of brain irradiation. Growth Horm IGF Res 14(Suppl A):S118–S124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman ML, Crowe BJ, Biller BM, Ho KK, Clemmons DR, Chipman JJ 2002 Which patients do not require a GH stimulation test for the diagnosis of adult GH deficiency? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimaretti G, Corneli G, Razzore P, Bellone S, Baffoni C, Arvat E, Camanni F, Ghigo E 1998 Comparison between insulin-induced hypoglycemia and growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone + arginine as provocative tests for the diagnosis of GH deficiency in adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:1615–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigo E, Aimaretti G, Gianotti L, Bellone J, Arvat E, Camanni F 1996 New approach to the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in adults. Eur J Endocrinol 134:352–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller BM, Samuels MH, Zagar A, Cook DM, Arafah BM, Bonert V, Stavrou S, Kleinberg DL, Chipman JJ, Hartman ML 2002 Sensitivity and specificity of six tests for the diagnosis of adult GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2067–2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna SP, Doward LC, Alonso J, Kohlmann T, Niero M, Prieto L, Wíren L 1999 The QoL-AGHDA: an instrument for the assessment of quality of life in adults with growth hormone deficiency. Qual Life Res 8:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SJ, McKenna SP, Doward LC, Hunt SM, Shalet SM 1995 Development of a questionnaire to assess the quality of life of adults with growth hormone deficiency. Endocrinol Metab 2:63–69 [Google Scholar]

- Kellner R 1987 A symptom questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry 48:268–274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perahia DG, Gilaberte I, Wang F, Wiltse CG, Huckins SA, Clemens JW, Montgomery SA, Montejo AL, Detke MJ 2006 Duloxetine in the prevention of relapse of major depressive disorder: double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 188:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie CJ, Milani RV 2006 Adverse psychological and coronary risk profiles in young patients with coronary artery disease and benefits of formal cardiac rehabilitation. Arch Intern Med 166:1878–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denninger JW, Papakostas GI, Mahal Y, Merens W, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Yeung A, Fava M 2006 Somatic symptoms in outpatients with major depressive disorder treated with fluoxetine. Psychosomatics 47:348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Pava JA, McCarthy MK, Steingard RJ, Bouffides E 1993 Anger attacks in unipolar depression. Part 1: Clinical correlates and response to fluoxetine treatment. Am J Psychiatry 150:1158–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Kellner R, Perini GI, Fava M, Michelacci L, Munari F, Evangelisti LP, Grandi S, Bernardi M, Mastrogiacomo I 1983 Italian validation of the Symptom Rating Test (SRT) and Symptom Questionnaire (SQ). Can J Psychiatry 28:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B 1993 SF-36 Health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware Jr JE, Raczek AE 1993 The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 31:247–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldt-Rasmussen U, Abs R, Bengtsson BA, Bennmarker H, Bramnert M, Hernberg-Ståhl E, Monson JP, Westberg B, Wilton P, Wüster C 2002 Growth hormone deficiency and replacement in hypopituitary patients previously treated for acromegaly or Cushing’s disease. Eur J Endocrinol 146:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SM, Badia X, Surinach NL 2006 Validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AcroQoL: a 6-month prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 155:269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonawalla SB, Farabaugh A, Johnson MW, Morray M, Delgado ML, Pingol MG, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M 2002 Fluoxetine treatment of depressed patients with comorbid anxiety disorders. J Psychopharmacol 16:215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA 2008 Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during four years of follow-up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonert VS, Elashoff JD, Barnett P, Melmed S 2004 Body mass index determines evoked growth hormone (GH) responsiveness in normal healthy male subjects: diagnostic caveat for adult GH deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3397–3401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli G, Di Somma C, Baldelli R, Rovere S, Gasco V, Croce CG, Grottoli S, Maccario M, Colao A, Lombardi G, Ghigo E, Camanni F, Aimaretti G 2005 The cut-off limits of the GH response to GH-releasing hormone-arginine test related to body mass index. Eur J Endocrinol 153:257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu XD, Gaw Gonzalo IT, Al Sayed MY, Cohan P, Christenson PD, Swerdloff RS, Kelly DF, Wang C 2005 Influence of body mass index and gender on growth hormone (GH) responses to GH-releasing hormone plus arginine and insulin tolerance tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1563–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio AF, Shavrikova EP, Blum WF, Shalet SM 2005 Quality of life in childhood onset growth hormone-deficient patients in the transition phase from childhood to adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4525–4529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuneo RC, Judd S, Wallace JD, Perry-Keene D, Burger H, Lim-Tio S, Strauss B, Stockigt J, Topliss D, Alford F, Hew L, Bode H, Conway A, Handelsman D, Dunn S, Boyages S, Cheung NW, Hurley D 1998 The Australian Multicenter Trial of Growth Hormone (GH) Treatment in GH-Deficient Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SJ, Shalet SM 1995 Factors influencing the desire for long-term growth hormone replacement in adults. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 43:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGauley GA, Cuneo RC, Salomon F, Sonksen PH 1990 Psychological well-being before and after growth hormone treatment in adults with growth hormone deficiency. Horm Res 33(Suppl 4):52–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad AM, Hopkins MT, Thomas J, Ibrahim H, Fraser WD, Vora JP 2001 Body composition and quality of life in adults with growth hormone deficiency; effects of low-dose growth hormone replacement. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 54:709–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deijen JB, Arwert LI, Witlox J, Drent ML 2005 Differential effect sizes of growth hormone replacement on quality of life, well-being and health status in growth hormone deficient patients: a meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 3:63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kołtowska-Haggstrom M, Hennessy S, Mattsson AF, Monson JP, Kind P 2005 Quality of life assessment of growth hormone deficiency in adults (QoL-AGHDA): comparison of normative reference data for the general population of England and Wales with results for adult hypopituitary patients with growth hormone deficiency. Horm Res 64:46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiter D, Abs R, Johannsson G, Scanlon M, Jönsson PJ, Wilton P, Koltowska-Häggström M 2006 Baseline characteristics and response to GH replacement of hypopituitary patients previously irradiated for pituitary adenoma or craniopharyngioma: data from the Pfizer International Metabolic Database. Eur J Endocrinol 155:253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosilio M, Blum WF, Edwards DJ, Shavrikova EP, Valle D, Lamberts SW, Erfurth EM, Webb SM, Ross RJ, Chihara K, Henrich G, Herschbach P, Attanasio AF 2004 Long-term improvement of quality of life during growth hormone (GH) replacement therapy in adults with GH deficiency, as measured by questions on life satisfaction-hypopituitarism (QLS-H). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:1684–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiren L, Bengtsson BA, Johannsson G 1998 Beneficial effects of long-term GH replacement therapy on quality of life in adults with GH deficiency. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 48:613–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]