Abstract

Context: Recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after cabergoline withdrawal ranges widely from 36 to 80%. The Pituitary Society recommends withdrawal of cabergoline in selected patients.

Objective: Our aim was to evaluate recurrence of hyperprolactinemia in patients meeting The Pituitary Society guidelines.

Design: Patients were followed from the date of discontinuation to either relapse of hyperprolactinemia or the day of last prolactin test.

Setting: We conducted the study at an academic medical center.

Patients: Forty-six patients meeting Pituitary Society criteria (normoprolactinemic and with tumor volume reduction after 2 or more years of treatment) participated in the study.

Interventions: After withdrawal, if prolactin returned above reference range, another measurement was obtained within 1 month, symptoms were assessed by questionnaire, and magnetic resonance imaging was performed.

Main Outcome Measures: We measured risk of and time to recurrence estimates as well as clinical predictors of recurrence.

Results: Mean age of patients was 50 ± 13 yr, and 70% were women. Thirty-one patients had microprolactinomas, 11 had macroprolactinomas, and four had nontumoral hyperprolactinemia. The overall recurrence was 54%, and the estimated risk of recurrence by 18 months was 63%. The median time to recurrence was 3 months (range, 1–18 months), with 91% of recurrences occurring within 1 yr after discontinuation. Size of tumor remnant prior to withdrawal predicted recurrence [18% increase in risk for each millimeter (95% confidence interval, 3–35; P = 0.017)]. None of the tumors enlarged in the patients experiencing recurrence, and 28% had symptoms of hypogonadism.

Conclusions: Cabergoline withdrawal is practical and safe in a subset of patients as defined by The Pituitary Society guidelines; however, the average risk of long-term recurrence in our study was over 60%. Close follow-up remains important, especially within the first year.

Patients with substantial tumor reduction following 2 or more years of cabergoline therapy had a 63% risk of recurrent hyperprolactinemia 18 months after the treatment was stopped.

Dopamine agonist therapy for hyperprolactinemia has become widely accepted as a primary therapy after several studies demonstrated inferior surgical cure rates (1). Cabergoline (CAB) is a well-tolerated dopamine agonist capable of rapidly normalizing prolactin as well as reducing tumor size in most cases (1,2). The need for long-term therapy, however, remains a clinical and economical downside of therapy. Additionally, concerns for valvulopathy have placed further emphasis on defining the optimal duration of therapy for all patients with hyperprolactinemia (3,4,5,6).

Some patients treated with CAB have been observed to achieve a long-term normalization of serum prolactin, suggesting a possibility of a CAB-induced remission or even a cure. Mechanisms responsible for CAB’s putative “anti-tumoral” effect are not currently known. Thus, it has been proposed to use clinical criteria to select patients for withdrawal (4). Such selection is guided by safety concerns related to effects of recurrent disease in a given patient and the hope of selecting patients with the highest chances of remission.

A recent study by Colao et al. (7) was an important landmark in testing the hypothesis that high remission rates can be achieved in a subset of patients with favorable clinical predictors. In that group of 200 patients with hyperprolactinemia carefully chosen for CAB withdrawal, 32% experienced recurrence in contrast to a 70–90% recurrence rate reported in several studies of unselected patients (8,9,10). These data suggested that a subgroup of hyperprolactinemic patients achieving remission can be identified on clinical grounds.

These observations served as the foundation for The Pituitary Society’s 2006 recommendations (2). In addition to specifying minimal length of dopamine agonist treatment of 1 to 3 yr, The Pituitary Society states that “dopamine agonists can be safely withdrawn in [normoprolactinemic] patients with no evidence of tumor on MRI” and recommends “a trial of tapering and discontinuation” if “the tumor volume is markedly reduced.” In contrast to the study of Colao et al. (7) where patients were selected for withdrawal on the basis of multiple parameters and were subjected to a step-wise withdrawal protocol, Pituitary Society Guidelines are more generally worded as to be practical in routine clinical care. However, treatment outcomes using these guidelines in a clinical setting have not been rigorously studied. Therefore, the present study was designed to define the rate of recurrence in our patient population employing The Pituitary Society’s recommendations for CAB withdrawal and to identify predictors of recurrence. To ensure further the safety of withdrawal in our study, we did not include patients with evidence of invasion of critical structures or proximity to the optic chiasm in patients with a visible tumor remnant.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Records of 194 consecutive patients followed for hyperprolactinemia were reviewed. We identified 46 patients who had no prior history of pituitary surgery or radiation and had their CAB discontinued between September 2002 and September 2007. Of the remaining patients screened, 46 were not available for follow-up; 26 patients had persistently elevated prolactin levels due to resistance to CAB or noncompliance; 16 had either an involvement of cavernous sinus or another critical structure or approximated optic chiasm; 15 were treated for less then 2 yr; 14 patients had a history of prior surgery or radiation; nine were followed without treatment; another nine were treated with bromocriptine; four refused discontinuation of CAB; three had an insufficient tumor size reduction as judged by the treating endocrinologist; two were planning pregnancy in the near future; two patients had medication-related hyperprolactinemia; and one had hyperprolactinemia due to stalk compression. Another patient with multiple endocrine neoplasm type 1 syndrome was expected to require lifelong therapy.

Of 46 patients included in the study, CAB was stopped in 44 patients by a physician to check for remission (42 patients) or because of pregnancy (two patients). Thirteen patients who were withdrawn before publication of the guidelines in 2006 and an additional two patients who had self-discontinued therapy were identified from the record review because they met criteria for withdrawal. These patients were followed according to a study protocol starting in 2006, and any prior data were extracted from clinical charts. All patients had been treated with CAB for at least 23 months, were normoprolactinemic, and had no evidence of critical structure involvement (defined as tumor extension beyond internal carotid arteries into one or both cavernous sinuses, invasion of sella floor or any other surrounding structure) or proximity to the optic chiasm by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as stated by the reporting radiologist. Patients were stopped if there was a substantial size reduction as judged by the treating neuroendocrinologist. For macroprolactinomas, lesion had to have shrunk into the sella turcica and to become less than 1 cm in the maximal dimension. For microadenomas, any degree of size reduction was acceptable, including 1 mm or more reduction in any of the tumor dimensions. For all but two patients with microadenomas, size reduction had occurred in the largest tumor dimension. Size reduction was calculated as a difference in millimeters between size at presentation and size at the time of withdrawal in a tumor dimension where the decrease has occurred.

All patients were managed by the neuroendocrinologists practicing under the auspices of the Johns Hopkins Pituitary Center (J.K., R.S., and G.S.W.).

Data collection and definitions

All patients were followed from the date of discontinuation of CAB treatment to either recurrence of hyperprolactinemia or the day of last available prolactin test. Data were censored on July 15, 2008. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved chart review for data collection and analysis.

Clinical information pertaining to patients’ original presentation was extracted from clinical histories. As a part of routine clinical care at the Pituitary Center, patients withdrawn from CAB are asked to obtain monthly prolactin measurements for the first 6 months after discontinuation and then quarterly for the rest of the first year. Subsequently, patients are asked to obtain prolactin measurements every 6 months for the second year, and then annually. Patients with a prolactin value above the reference range were asked to obtain another measurement within 1 month, and if that was abnormal, an MRI was requested. Symptoms of hyperprolactinemia were assessed over the phone or in the first subsequent clinic appointment according to a short questionnaire. Patients with two prolactin measurements above the upper reference range after discontinuation of CAB were considered to have a recurrence. Time to recurrence was estimated from discontinuation of CAB to the first available abnormal prolactin level. Because patients were variably compliant, not all values were available for each patient. When data were missing, time to recurrence was estimated from discontinuation of CAB to the first available abnormal prolactin value.

Patients were considered to be in remission if the prolactin level was within the reference range at the laboratory used. Prolactin measurements were performed by the following laboratories: Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology, using enzyme immunoassay (0–19 ng/ml; Tosoh BioScience, Tessenderlo, Belgium); Quest Diagnostics, using immunochemiluminometric assay (ADVIA Centaur Immunoassay Analyzer; Siemens, Tarrytown, NY) (men 0–18, nonpregnant women 0–30, and postmenopausal women 0–20 ng/ml); and LabCorp, using immunochemiluminometric assay (0–29.2 ng/ml).

MRI reports and images, when available, were reviewed by the study investigators. Tumor size measurements were recorded as stated by the reporting radiologist at the time of presentation and before CAB withdrawal. MRI studies were obtained at different radiological facilities as a part of the patients’ clinical care. A substantial number of MRI scans were performed at the Johns Hopkins Department of Radiology, with the use of 0.1 mmol/kg of a gadolinium-based contrast agent including sagittal T1-weighted, axial T2-weighted, axial flair, as well as postcontrast axial, sagittal and coronal T1-weighted, and dynamic coronal T1-weighted sequences focused on the sella turcica. Precise size reduction could not be estimated for four patients with microprolactinomas due to missing initial scans. In those patients, size reduction was conservatively considered to be zero.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata SE, version 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Recurrence-free time by tumor type was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and was compared using log-rank tests. Associations between the hazard of recurrence and clinical predictors were assessed using semiparametric Cox proportional hazard models. To check for confounding, any predictors that had a significant association with recurrence in the univariate model were entered together with one additional cofactor into a multivariate model. Significance level was set at 5%.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

Forty-six patients were withdrawn from CAB. Thirty-one patients (67%) had microprolactinomas, 11 (24%) had macroprolactinomas, and four (9%) had nontumoral hyperprolactinemia (NTHP) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at presentation (n = 46) by the type of hyperprolactinemic disorder

| Characteristic | Hyperprolactinemic disorder

|

Total sample (n = 46) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microprolactinoma (n = 31) | Macroprolactinoma (n = 11) | NTHP (n = 4) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Females | 26 (84) | 4 (36) | 2 (50) | 32 (70) |

| Males | 5 (16) | 7 (64) | 2 (50) | 14 (30) |

| Age (yr)a | ||||

| Median | 44 | 54 | 46.5 | 45 |

| Range | 18–68 | 36–75 | 18–62 | 18–75 |

| Prolactin at diagnosis (ng/ml) | ||||

| Median | 73.0 | 310 | 51.5 | 99.9 |

| Range | 27.2–182.3 | 103–1122 | 50.4–90.0 | 27–1122 |

| No. of missing values | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Prolactin nadir (ng/ml) | ||||

| Median | 3.6 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Range | 0.1–17 | 0.1–6.2 | 0.1–13 | 0.1–17 |

| Maximal tumor size at presentation (mm) | ||||

| Median | 8 | 15 | 8 | |

| Range | 5–10 | 11–29 | 1.5–29 | |

| No. of missing values | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Maximal tumor size at time of CAB withdrawal (mm)b | ||||

| Median | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Range | 0–9 | 0–7 | 0–9 | |

| Tumor size change, n (%) | ||||

| Resolved | 11 (36) | 6 (55) | 17 (40) | |

| Decreased size | 20 (64) | 5 (45) | 25 (60) | |

| Reduction in tumor size (%)b | ||||

| Median | 66 | 100 | 80 | |

| Range | 11–100 | 36–100 | 11–100 | |

| No. of missing values | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Symptoms at presentation | ||||

| Galactorrhea, n (%) | 15 (48) | 4 (36) | 1 (25) | 20 (44) |

| Irregular menses, n (% women), no. taking OCPs | 18 (69), 5 | 3 (75), 1 | 2 (100) | 23 (72) 6 |

| Decreased libido, n (% men) | 5 (100) | 7 (100) | 2 (100) | 14 (100) |

| Impaired sexual function, n (% men) | 5 (100) | 4 (57) | 2 (100) | 11 (79) |

| Headache, n (%) | 7 (23) | 3 (27) | 0 | 10 (22) |

| Vision changes, n (%), missing | 0 (0), 1 | 3 (27), 0 | 0 | 3 (7), 1 |

| Pituitary deficits at presentation | ||||

| Hypogonadism, n (% men) | 4 (80) | 7 (100) | 1 (50) | 12 (86) |

| Central hypothyroidism, n (%) | 2 (18) | 0 | 2 (4) | |

| Adrenal insufficiency, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GH deficiency, n (%) | 3 (10) | 5 (46) | 1 (25) | 9 (20) |

| Diabetes insipidus, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy and menopause | ||||

| Pregnancy prior to diagnosis, n (%) | 9 (35) | 2 (50) | 1 (50) | 12 (38) |

| Pregnancy since diagnosis, n (%) | 5 (19) | 0 | 0 | 5 (16) |

| Menopause, n (%) | 2 (8) | 1 (25) | 0 | 3 (9) |

| Use of OCPs and estrogens | ||||

| At the time of or since diagnosis, n (% women) | 8 (31) | 2 (50) | 1 (50) | 11 (24) |

| After CAB withdrawal, n (% women), unknown | 4 (15), 1 | 1 (25) | 0 | 5 (11) |

| Treatment details | ||||

| Duration of treatment (months) | ||||

| Median | 43 | 56 | 47 | 52 |

| Range | 23–119 | 26–205 | 23–75 | 23–205 |

| Maximum weekly dose, n (%) | ||||

| 0.25 | 3 (10) | 0 | 1 (20) | 4 (9) |

| 0.5 | 9 (29) | 2 (20) | 2 (40) | 13 (28) |

| 1.0 | 17 (55) | 7 (70) | 2 (40) | 25 (54) |

| 1.5 | 2 (7) | 2 (10) | 0 | 4 (9) |

| Weekly dose before stopping treatment, n (%) | ||||

| 0.25 | 13 (42) | 4 (36) | 3 (75) | 20 (44) |

| 0.5 | 7 (23) | 6 (55) | 1 (25) | 14 (30) |

| 1.0 | 9 (29) | 1 (9) | 0 | 10 (22) |

| 1.5 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| (continued) | ||||

Table 1A.

continued

| Characteristic | Hyperprolactinemic disorder

|

Total sample (n = 46) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microprolactinoma (n = 31) | Macroprolactinoma (n = 11) | NTHP (n = 4) | ||

| Patients treated with bromocriptine before CAB, n (%) | 8 (26) | 4 (36) | 0 | 12 (26) |

| Total duration of treatment including bromocriptine (months) | ||||

| Median | 55 | 56 | 47 | 55 |

| Range | 23–249 | 26–325 | 23–75 | 23–325 |

Age since last birthday at stopping the treatment.

Two patients with microadenomas had reduction in a dimension other than the maximal.

All patients were treated for over 23 months before withdrawal of therapy for a median treatment time of 4.3 yr. At the time of CAB discontinuation, 74% of patients were receiving 0.5 mg or less of CAB a week.

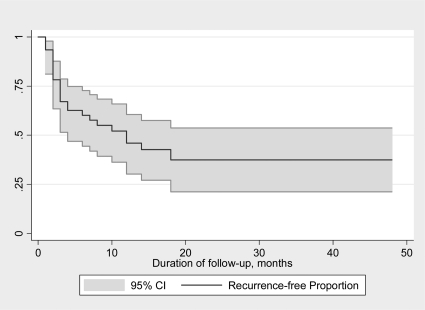

Overall recurrence

Fifty-four percent [95% confidence interval (CI), 40–69] of all patients recurred by the time of study completion (Table 2). The rate of recurrence did not change if the following groups of patients were excluded from the analysis: 1) those who had self-discontinued CAB or had CAB stopped due to pregnancy: estimated recurrence 52% (95% CI, 36–68); z score, 0.029; 2) those with less than 50% tumor size reduction: estimated recurrence 41% (95% CI, 24–59); z score, 0.827; 3) those with tumor reduction in the dimension other than the largest: estimated recurrence 55% (95% CI, 40–70), z score, 0.827; and 4) those treated with more than 0.5 mg of CAB per week prior to withdrawal: estimated recurrence 52% (95% CI, 36–65); z score, 0.049. The estimated risk of recurrence for all patients was 63% (95% CI, 46–79) by 18 months (Fig. 1). Among the patients who recurred, the median time to recurrence was 3 months, and 91% of recurrences occurred within 1 yr of CAB discontinuation.

Table 2.

Time to recurrence or time to last prolactin measurement (censoring) in the study population

| Characteristic | Type of tumor

|

Total sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microprolactinoma (n = 31) | Macroprolactinoma (n = 11) | NTHP (n = 4) | ||

| Recurrence, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 16 (52) | 6 (55) | 3 (75) | 25 (54) |

| Time to recurrence in patients who recurred (months) | ||||

| Median | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Range | 1–18 | 1–4 | 3–14 | 1–18 |

| Follow-up after withdrawal in patients without recurrence (months) | ||||

| Median | 15 | 16 | 7 | 15 |

| Range | 5–48 | 2–23 | 2–48 | |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of recurrence and 95% CI in 50 months after CAB withdrawal in the overall study population of 46 patients. Estimated risk of recurrence is 0.54 (95% CI, 0.34–0.64) at 12 months and 0.63 (95% CI, 0.46– 0.79) at 18 months.

Recurrence by hyperprolactinemic disorder

Patients with NTHP had the highest risk of recurrence, whereas risk was lowest for patients with microprolactinomas (Table 3). However, these differences were not statistically significant (log-rank χ2 test statistic, 0.71; P = 0.70). The median prolactin nadir before withdrawal and time to recurrence were similar among three groups (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 3.

Results of univariate Cox proportional hazard regression models

| Predictor | Results of Cox proportional hazard models

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated hazard ratio | 95% CI for hazard ratio | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.03 | 0.45, 2.36 | 0.94 |

| Female (ref.) | 1.0 | ||

| Age (yr) | |||

| Per 1 yr of age | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.02 | 0.46 |

| Duration of treatment (months) | |||

| Per month | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.66 |

| Type of tumor | |||

| Microprolactinoma | 0.62 | 0.18, 2.15 | 0.45 |

| Macroprolactinoma | 0.77 | 0.19, 3.09 | 0.71 |

| NTHP (ref.) | 1.0 | ||

| Prolactin at diagnosis | |||

| Per 1 ng/ml | 1.00 | 1.000, 1.002 | 0.77 |

| Prolactin nadir | |||

| Per 1 ng/ml | 1.08 | 1.00, 1.18 | 0.06 |

| Tumor changes on MRI | |||

| Resolved | 0.80 | 0.33, 1.92 | 0.62 |

| Not resolved (ref.) | 1.0 | ||

| Maximum tumor size | |||

| Per 1 mm | 1.01 | 0.93, 1.09 | 0.87 |

| Minimum tumor size | |||

| Per 1 mm | 1.18 | 1.03, 1.35 | 0.02 |

| Maximum dose of CAB (mg/wk) | 0.22 | ||

| 1.5 | 0.24 | 0.03, 2.33 | 0.34 |

| 1.0 | 0.54 | 0.15, 1.89 | 0.31 |

| 0.5 | 0.49 | 0.13, 1.92 | |

| 0.25 | 1.0 | ||

| Dose prior to discontinuation (mg/wk) | 0.39, 2.92 | 0.89 | |

| 1.0 and more | 1.07 | 0.32, 2.14 | 0.70 |

| 0.5 | 0.83 | ||

| 0.25 | 1.0 | ||

| Use of bromocriptine | 0.62, 3.31 | 0.41 | |

| Yes | 1.43 | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Total duration of treatment (including bromocriptine) | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.90 |

| Use of OCPs during treatment with CAB | 0.15, 1.48 | 0.198 | |

| Yes | 0.47 | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Use of OCPs after withdrawal of CAB | 0.13, 2.59 | 0.475 | |

| Yes | 0.58 | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Presence of pituitary deficits at presentationa | |||

| Yes | 0.94 | 0.42, 2.11 | 0.90 |

| No | 1.0 | ||

Includes presence of hypogonadism, central hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, GH deficiency, and diabetes insipidus.

In the group of 31 patients with microprolactinomas, 16 patients (52%) experienced recurrence after a median of 3 months (range, 1–18 months). At presentation, in this group of 26 women and five men, tumor sizes ranged from 5 to 10 mm. CAB was withdrawn after a median of 43 months. At the time of withdrawal, the tumors were no longer visible on an MRI in 11 patients (36%) and had decreased in size in the remaining 20 patients (64%). Median size of tumor remnant was 3 mm.

Fifteen patients with microprolactinomas (48%) remained free of recurrence at a median of 15 months (range, 5 to 48 months) of follow-up.

In the group of 11 patients with macroprolactinomas, hyperprolactinemia recurred in six patients (55%) after a median period of 3 months (range, 1–4). At presentation, in this group of seven men and four women, tumor sizes ranged from 11 to 29 mm (median, 15 mm). CAB therapy was discontinued after a median of 56 months. At the time of CAB withdrawal, the tumors were no longer visible on an MRI in six patients (55%) and had decreased in size in the remaining five patients (45%). Median size reduction was 100% (range, 36–100%).

Five patients with macroprolactinomas (45%) remained free of recurrence at a median of 16 months (range, 2–23) of follow-up.

Three of four patients with NTHP recurred at a median of 3 months. One patient was in remission at the 7-month follow-up (Tables 1 and 2).

Predictors of recurrence

The size of the tumor remnant at the time of CAB withdrawal predicted recurrence. Each additional millimeter of size reduction from the original tumor size was associated with an 18% decrease in the risk of recurrence (95% CI, 3–35; P = 0.17). This risk was 10% (95% CI, 0.96–1.28; P = 0.17) in a subgroup of 44 patients, none of whom were withdrawn because of pregnancy. After controlling for the type of hyperprolactinemic disorder, prolactin nadir, maximum dose of CAB, CAB dose before discontinuation, use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), and total duration of treatment (in separate models), the association between recurrence and minimal tumor size did not change significantly (absolute risk increase ranged from 16 to 19%, with P values from 0.016 to 0.018).

Frequency of recurrence was not statistically different between patients who had a visible tumor remnant on the MRI and those who did not (50 vs. 53.8%). Similarly, resolution of MRI findings was not associated with a decrease of the recurrence rate based on the results of log-rank test (P = 0.60).

There was a relationship between prolactin nadir (lowest prolactin value before therapeutic withdrawal) and risk of recurrence. Each 1 ng/ml of serum prolactin level was associated with an 8% increase in the risk of recurrence, and this relationship approached statistical significance (95% CI, 0–18; P = 0.062).

When controlling for tumor size at recurrence, the effect of prolactin nadir on recurrence was no longer significant. The relationship between prolactin nadir and recurrence was not affected when the type of hyperprolactinemic disorder, maximum dose of CAB, CAB dose before discontinuation, use of OCPs, and total duration of treatment were controlled for in separate models.

There were no statistically significant associations between risk of recurrence and sex, age, type of hyperprolactinemic disorder, duration of treatment, serum prolactin at diagnosis, tumor size at diagnosis, maximum CAB treatment dose, CAB dose before discontinuation, history of bromocriptine use or its duration, or the presence of pituitary deficits at diagnosis.

Clinical characteristics of patients with recurrences

Among patients who recurred (n = 25), none had evidence of tumor enlargement or regrowth on the MRI. Results on an MRI at the time of recurrence were not available in four (16%) patients.

Prolactin levels at the time of recurrence did not differ significantly between the three groups (median, 32.6 ng/ml; Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with recurrence

| Type of tumor

|

Total sample (n = 25) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microprolactinoma (n = 16) | Macroprolactinoma (n = 6) | NTHP (n = 3) | ||

| Prolactin at recurrence | ||||

| Median | 35.7 | 27.0 | 32.0 | 32.6 |

| Range | 20.2–73.2 | 19.4–60.9 | 16.6–76 | 16.6–76 |

| Symptoms at recurrence | ||||

| Galactorrhea, n (%) | 5 (31) | 1 (17) | 1 (33) | 7 (28) |

| Irregular menses, n (% women) | 5 (39) | 0 | 0 | 5 (31) |

| Decreased libido, n (% men) | 0 | 1 (25) | 1 (50) | 2 (22) |

| Impaired sexual function, n (% men) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (11) |

| Headache, n (%) | 1 (6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Vision changes, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

At the time of recurrence, 28% of patients reported galactorrhea, and 31% of women and 22% of men reported symptoms of hypogonadism (Table 4). One patient reported headache, and none had visual changes. Seven patients (28%) reported symptoms of hypogonadism, and 11 (44%) had at least one symptom that could be related to hyperprolactinemia or local tumor effect.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the rates of hyperprolactinemia recurrence in 46 patients with normoprolactinemia and favorable MRI characteristics after at least 2 yr of CAB therapy. Patient selection was informed by recommendations of The Pituitary Society and targeted patients with low risk of mass effect due to possible tumor reexpansion and those with highest chance of remission.

Fifty percent of patients recurred by 12 months, and 54% recurred overall. The estimated 18-month risk of recurrence was 63%. Recurrence was not significantly different among patients with microprolactinomas, macroprolactinomas, and NTHP.

Three other studies in addition to this one have addressed recurrence rates in patients treated with CAB for 2 yr or longer. Studies by Cannavò et al. (8) and Biswas et al. (9) enrolled unselected patients, whereas Colao et al. (7) and the present study selected a subset of patients for CAB withdrawal who demonstrated favorable clinical outcomes after pharmacological treatment. All four studies enrolled patients without prior history of surgery or radiation and required normoprolactinemia before withdrawal.

Cannavò et al. (8) had observed 81.5% recurrence rate at 1 yr in 27 unselected patients with macro- and microadenomas. In their group of patients, mean adenoma sizes significantly decreased after treatment. Biswas et al. (9) observed a 68.7% recurrence rate in 67 patients with microprolactinomas who were followed for 12 or more months after withdrawal. MRI response to treatment was not used as a selection criterion in this group of patients. A prospective trial of 200 patients fitting strict clinical selection criteria (including greater then 50% tumor size reduction by MRI) by Colao et al. (7) reported only an 18% recurrence by 1 yr and 32% recurrence by 5-yr follow-up. A follow-up study of 221 patients documented 39.8% recurrence by 8 yr of follow-up (11). This lower observed recurrence rate suggested the importance of clinical selection criteria to maximize the chance of remission.

Based on the above findings and in accordance with The Pituitary Society’s recommendations, our study selected patients with favorable clinical criteria including MRI characteristics. The minimal length of treatment recommended by The Pituitary Society is 1–3 yr. In this study, we followed patients who were treated for 2 yr or more and for a median duration of 4.5 yr before withdrawal of therapy. All patients were normoprolactinemic before withdrawal. The Pituitary Society points out that withdrawal is safe in patients who no longer have an evidence of tumor on MRI and recommends attempting withdrawal in patients in whom tumor volume is “markedly reduced.” In our study, 35% of patients no longer had an evidence of tumor on MRI. In those with a visible tumor remnant, median percentage size reduction was 80% (100% in macroadenomas), and no tumor involved critical structures or approached the optic chiasm.

Despite the use of Pituitary Society criteria to guide withdrawal, we observed a substantial rate of recurrence that fits better with observations of Cannavò et al. (8) and Biswas et al. (9), who studied unselected patients (Table 5). Moreover, ours and the latter two studies have documented a shorter time to recurrence compared with the Colao study (7), with most relapses happening within the first year.

Table 5.

Studies examining recurrence in patients treated with CAB for 2 yr or more

| First author, year (Ref.) | Population size | Duration of follow-up (months) | Recurrence | Z score compared to present study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannavò et al., 1999 (8) | 27 | 12 | 81.5 | 2.465, SS |

| Colao et al., 2003 (7) | 200 | 12 (60) | 18 (32) | 4.392, SS |

| Biswas et al., 2005 (9) | 67 | 12 | 68.7 | 1.839, NS |

| Present study | 46 | 12 (48) | 50 (64) |

This table compares proportions of patients recurred. Censoring is not being taken into account. SS, Statistically significant; NS, not statistically significant in two-sided analysis.

We have considered several potential explanations for the reported differences in recurrence rates among studies. Most importantly, we questioned differences in the patient selection criteria. The prospective trial by Colao et al. (7) required 50% tumor size reduction before withdrawal. Sixty-seven percent of our subjects fulfilled the more stringent size reduction criterion of 50% or greater. This subgroup of patients most comparable to the Colao et al. (7) population had a 41% (95% CI, 24–59) recurrence rate, which was still higher and statistically different from the one observed by the Colao group [32% (95% CI, 26–39); z score, 2.082]. Additionally, in this study, we have accepted reduction in any tumor dimension as adequate evidence of decreasing tumor mass. Colao et al. (7) have stipulated reduction in the largest tumor dimension as the only acceptable inclusion criterion. Sensitivity analysis excluding two patients whose microprolactinomas had shrunk in the dimension other than largest did not affect recurrence in our study. Despite the differences in selection criteria, both studies found a strong liner association between the size of tumor remnant and risk of recurrence, underscoring an importance of size reduction criterion. The differences in recurrence may in fact lie in the degree of tumor size reduction, although this could not be conclusively shown. Moreover, further studies are needed to identify a reproducible measure of tumor size reduction that has the best ability to predict recurrence.

Bromocriptine use has been associated with a higher risk of recurrence, whereas pregnancy and menopause have been associated with a lower risk in prior studies (12,13); however, neither was the case in our patient group. We questioned whether differences in CAB tapering before its discontinuation could account for recurrence rate differences between our study and the prospective trial. In the Colao et al. study (7), the CAB dose was reduced to 0.5 mg/wk in all patients and was withdrawn only in patients whose prolactin remained normal on this small dose. Our study reflects realities of our clinical practice where 74% of patients were on 0.5 mg of CAB per week or less before discontinuation. We performed sensitivity analysis restricted to patients treated with 0.5 mg of CAB per week to determine whether this subpopulation had a lower recurrence rate similar to that of Colao et al. (7). However, the recurrence was not different in this subpopulation compared with the whole group. It appears that the differences in recurrence seen in the present study and the prospective trial (7) are not easily explained by obvious differences in populations or tapering protocol beyond the differences in the MRI selection criteria.

The findings of this study are strengthened by our requirement for a second abnormal prolactin to diagnose recurrence. Despite a short duration of hyperprolactinemia, 28% of those with recurrences reported symptoms of hypogonadism, supporting true clinical recurrence.

There are some limitations to our study. The duration of follow-up was relatively short, with half the patients in remission followed for less than 15 months. This may have resulted in an underestimation of recurrence. Some of the patients were identified through record review rather than having had their CAB discontinued prospectively. However, this should not affect outcome because inclusion criteria are objectively defined and are easy to ascertain from records. We chose to include two patients who satisfied all of the inclusion criteria but were withdrawn specifically because of pregnancy. However, the course of illness may be different in hyperprolactinemic patients who become pregnant because pregnancy has been associated with both tumor size increase (1) and improved chance of remission (14,15) in prior studies. Sensitivity analysis has demonstrated that inclusion of this small cohort has not affected outcomes in this study. However, our findings should not be generalized to all pregnant patients until larger groups of pregnant hyperprolactinemic women are studied in this context.

Our findings do confirm previous observations of a positive relationship between prolactin nadir, size of tumor remnant, and rate of recurrence. Interestingly, resolution of MRI findings per se was not associated with a lower rate of recurrence. Additionally, in our study, prolactin nadir was no longer a significant predictor of recurrence when tumor size at the time of CAB withdrawal was taken into account. This suggests that prolactin nadir may be reflecting a declining tumor mass, rather than acting as an independent predictor. It appears that a low-normal prolactin level before interruption of therapy and reduction in tumor size are necessary but not sufficient conditions to ensure remission. No other clinical predictors have emerged in this or other studies. Further insights into pharmacology of CAB-induced remission are needed to identify any other potential biochemical, immunological, or pharmacogenomic markers in susceptible patients.

The withdrawal and follow-up protocol adopted by our Pituitary Center aimed to minimize recurrence-associated risks. No patients with tumors involving critical structures or those approaching the optic chiasm had their CAB discontinued. MRI was requested in all patients with a biochemical recurrence. We observed that none of those with available MRI reports had tumor enlargement or regrowth at the time of biochemical recurrence. Frequent prolactin testing after therapeutic interruption ensured a relatively short duration of hyperprolactinemia in cases of recurrence. Despite that, a substantial proportion of patients (28%) reported overt symptoms of hypogonadism at the time of recurrence.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this study where patient selection for CAB withdrawal was informed by recommendations of The Pituitary Society, recurrence was similar to that previously reported in unselected normoprolactinemic patients (without tumor volume reduction by MRI requirement). The risk of recurrence at 18 months was over 60%, and the majority of patients recurred within the first year. Patients with small tumor remnants were least likely to experience recurrence. None of those recurring had experienced tumor regrowth in the timeframe of current follow-up protocol.

Our subjects represent a typical mix of patients who experience normalization of prolactin and reduction of tumor volume when treated with CAB, and their experience can be generalized to others treated in clinical practice. Based on these and earlier findings, it appears practical and safe to attempt withdrawal in patients treated with CAB for over 2 yr with normalization of prolactin and tumor volume reduction who have no invasion of critical structures or tumors that abut the optic chiasm. Close follow-up remains important, especially within the first year and in those patients whose CAB treatment was not reinstituted at the time of biochemical recurrence because the risk of tumor remnant enlargement over time likely exists. High rates of clinical hypogonadism at the time of recurrence make a trial of therapeutic interruption unattractive in some patients, particularly those desiring fertility in the near term. It remains important to validate prospectively The Pituitary Society Guidelines for CAB withdrawal in long-term studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Rachel Derr, Todd Brown, and David Cooper for the detailed critique of the manuscript. Ms. June Dameron is gratefully acknowledged for her help with data organization.

Footnotes

Address requests for reprints to: Gary S. Wand, M.D.; 720 Rutland Avenue, Ross Building, Room 863, Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant T32 DK062707 (to J.K.) and a gift from the Kenneth Lattman Foundation (to G.S.W.).

These data were presented in part at The Endocrine Society’s Annual Meeting in 2008 in San Francisco, CA.

Disclosure Summary: J.K., R.S., G.Y., and G.S.W. have nothing to declare.

First Published Online March 31, 2009

For editorial see page 2247

Abbreviations: CAB, Cabergoline; CI, confidence interval; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NTHP, nontumoral hyperprolactinemia; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

References

- Gillam MP, Molitch ME, Lombardi G, Colao A 2006 Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev 27:485–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanueva FF, Molitch ME, Schlechte JA, Abs R, Bonert V, Bronstein MD, Brue T, Cappabianca P, Colao A, Fahlbusch R, Fideleff H, Hadani M, Kelly P, Kleinberg D, Laws E, Marek J, Scanlon M, Sobrinho LG, Wass JA, Giustina A 2006 Guidelines of The Pituitary Society for the diagnosis and management of prolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 65:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Galderisi M, Di Sarno A, Pardo M, Gaccione M, D'Andrea M, Guerra E, Pivonello R, Lerro G, Lombardi G 2008 Increased prevalence of tricuspid regurgitation in patients with prolactinomas chronically treated with cabergoline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3777–3784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogazzi F, Buralli S, Manetti L, Raffaelli V, Cigni T, Lombardi M, Boresi F, Taddei S, Salvetti A, Martino E 2008 Treatment with low doses of cabergoline is not associated with increased prevalence of cardiac valve regurgitation in patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Int J Clin Pract 62:1864–1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kars M, Delgado V, Holman ER, Feelders RA, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Bax JJ, Pereira AM 2008 Aortic valve calcification and mild tricuspid regurgitation but no clinical heart disease after 8 years of dopamine agonist therapy for prolactinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3348–3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancellotti P, Livadariu E, Markov M, Daly AF, Burlacu MC, Betea D, Pierard L, Beckers A 2008 Cabergoline and the risk of valvular lesions in endocrine disease. Eur J Endocrinol 159:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Cappabianca P, Di Somma C, Pivonello R, Lombardi G 2003 Withdrawal of long-term cabergoline therapy for tumoral and nontumoral hyperprolactinemia. N Engl J Med 349:2023–2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavò S, Curtò L, Squadrito S, Almoto B, Vieni A, Trimarchi F 1999 Cabergoline: a first-choice treatment in patients with previously untreated prolactin-secreting pituitary adenoma. J Endocrinol Invest 22:354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas M, Smith J, Jadon D, McEwan P, Rees DA, Evans LM, Scanlon MF, Davies JS 2005 Long-term remission following withdrawal of dopamine agonist therapy in subjects with microprolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori M, Arosio M, Gambino G, Romano C, Biella O, Faglia G 1997 Use of cabergoline in the long-term treatment of hyperprolactinemic and acromegalic patients. J Endocrinol Invest 20:537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Guerra E, Pivonello R, Cappabianca P, Caranci F, Elefante A, Cavallo LM, Briganti F, Cirillo S, Lombardi G 2007 Predictors of remission of hyperprolactinaemia after long-term withdrawal of cabergoline therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 67:426–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colao A, Di Sarno A, Landi ML, Scavuzzo F, Cappabianca P, Pivonello R, Volpe R, Di Salle F, Cirillo S, Annunziato L, Lombardi G 2000 Macroprolactinoma shrinkage during cabergoline treatment is greater in naive patients than in patients pretreated with other dopamine agonists: a prospective study in 110 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:2247–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunakaran S, Page RC, Wass JA 2001 The effect of the menopause on prolactin levels in patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 54:295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani PG, Mattei AM, Severini V, Cavioni V, Maggioni P, Testa G 1992 Long-term effects of time, medical treatment and pregnancy in 176 women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 44:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Pound N, Sturrock NDC, Lambourne J 1996 Long-term follow-up of patients with hyperprolactinaemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 45:299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]