Abstract

Conducting research with Native American communities poses special challenges from misunderstandings that may arise from the interface of differing cultural worldviews held by the scientific and the Native communities. Although the community-based participatory research approach shows promise for conducting research that can maximize benefits and minimize the risks of harm to Native American people, there is little information related to the practical implementation of culturally appropriate research practices when working with Native American communities. Drawing on the authors' research with three Native American communities in the Northwest, this article describes culturally appropriate processes for engaging Native American communities. The first section identifies and describes the principles that provide the foundation for the authors' research activity as a spiritual covenant and guides the authors' research with the three communities. The second section describes the project phase matrix that was used to organize the approaches employed in this work.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, research methodology, action research, Native Americans, ethnogerontology

Spirituality pervades every aspect of Indian life in ways difficult to grasp by most non-Indian Americans. It affects worldview, family relations, health and illness, ways of healing, and ways of dealing with grief. (Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project, 2002, p. 236)

The community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach has been gaining the attention of health-focused scientists who are interested in working toward the goal of Healthy People 2010 to eliminate health disparities among people of ethnic minority groups. CBPR is an empowering research approach that involves the community in all stages of the research process from problem identification to research design and in data collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination. With the increased interest in the CBPR approach, the literature base continues to grow with regard to issues relevant to the approach. Some of these issues include coming to an understanding of who the community is, being sensitive to the dynamics of rapport and trust during community entry, learning what roles are appropriate for outside scientists to take during the progression of the project, and staying in touch with the amount of community involvement desired on the part of the community, particularly during unfunded stages when there is no money to support the efforts of already busy community participants (Fisher & Ball, 2002; Letiecq & Bailey, 2004; Macaulay et al., 1998; Manson, Garroutte, Goins, & Henderson, 2004; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Smith, Christopher, & McCormick, 2004; Stoecker, 2003). Even as the issues are debated, the use of a community-based approach to research holds the potential to ensure that research is anchored in the cultural context of the people.

Conducting research with Native American communities poses special challenges occurring, in part, from misunderstandings that may arise from the interface of differing cultural worldviews held by the scientific and the Native communities. Wax (1991) asserted:

Although both researchers and researched have standards for assessing conduct, in most cases these standards are incommensurable, for the parties do not share a common moral vocabulary nor do they share a common vision of the nature of human beings as actors within the universe. (p. 2)

The best intentions of research scientists may go awry when trying to operate within a cultural ethos that is vastly different from the world of academia.

A well-founded, historic distrust of research on the part of tribal communities also intensifies the challenges (Mihesuah, 1998; Norton & Manson, 1996; Red Horse, Johnson, & Weiner, 1989). Red Horse et al. (1989) asserted that disease-guided models from the dominant culture have shown little insight into health behaviors of Native American people. Biomedical research, with its focus on problems, deficits, and dysfunctions, has pathologized and caused economic harm to tribal life (Mihesuah, 1998; Norton & Manson, 1996; Red Horse et al., 1989). Only recently have the strengths of Native communities been emphasized (Mihesuah, 1998; Tripp-Reimer, 1999). Additional complaints about research related problems that have been visited on some Native American tribes include: (a) research projects identifying problems without benefit to the participating tribe, (b) the publication of sensitive cultural material, (c) the exploitation of Native American communities to further investigators' academic careers, and (d) the misrepresentation of findings derived from the cultural misinterpretation of data (American Indian Law Center, 1999; Carson & Hand, 1999; Maynard, 1974; Quandt, McDonald, Bell, & Arcury, 1999; Trimble, 1977).

Fisher and Ball (2002) note that researchers often lack a historical understanding of Native American communities. Centuries of shifting and destructive federal polices have resulted in intergenerational trauma that remains evident today in Native American families and communities (Duran & Duran, 1995; Stubben, 2001). Without this historical perspective, there is the possibility of underestimating the role historical trauma continues to play in Native American communities, further compounding the potential for misunderstanding and misinterpretation (Fisher & Ball, 2002; Hendrix & Winters, 2001; Stubben, 2001).1

Although the CBPR approach shows promise for conducting research that can maximize benefits and minimize the risks of harm to Native American people, there is little information related to the practical implementation of culturally appropriate research practices when working with Native American communities. Drawing on our research with three Native American communities in the Northwest, the purpose of this article is to describe culturally appropriate processes for engaging Native American communities as part of our research process. The article is divided into two sections: (a) the identification and description of principles that provide the foundation for our research activity as a spiritual covenant and that guide our research with the three communities and (b) a description of the project phase matrix that we have used to organize the approaches we employed in our work. As part of our research process, reflection on our interactions among the members of the team and the interactions between the research team and each of the communities has been ongoing and informs the remainder of the article.

Description of the Project

The Caring for Native American Elders project is the name of a program of research that addresses elder maltreatment in a community context. The idea for the project was initiated by the Native member of the research team. Through her work as a social worker, she had opportunity to observe many Native American families and listen to their stories. As a result, she became concerned about the treatment of some elders who lived on reservations. She wondered if a family conference intervention that had been successful for child maltreatment might, with modification, be appropriate for families who were struggling with the care of an elder or who were concerned about elder mistreatment. This model is described elsewhere (Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois, & Weinert, 2004). The modified version of the family conference intervention is called the Family Care Conference (FCC).

The Caring for Native American Elders program of research has evolved since 2000. The project has taken form with three different Native American communities. In the first community, we gathered contextual data, interviewed elders and social or health care providers about forms and extent of elder maltreatment, asked about the desirability and feasibility of the FCC, piloted the intervention, and employed and trained three FCC facilitators. For the second and third communities, we obtained tribal approval and began community entry by meeting with key individuals, who then arranged for us to meet with elders and representatives from service-providing agencies to determine the desirability and feasibility of the FCC intervention in their communities.

Fundamental Principles

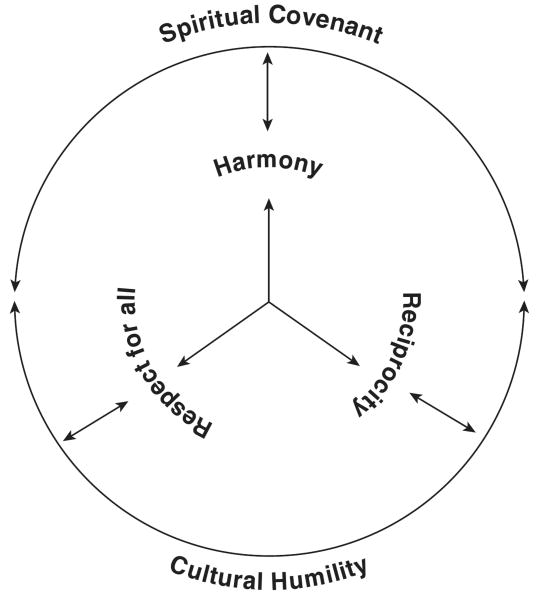

We identified five principles that have grounded our work with the three Native American communities; they comprise two encompassing constructs, research as a spiritual covenant (Wax, 1991) and cultural humility (Hunt, 2001; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998), and three elaborative concepts of harmony, reciprocity, and respect for all. As overarching constructs, research as spiritual covenant is discussed first; cultural humility is discussed last. Placing the two comprehensive concepts at the beginning and end of the discussion brings the principles into a circle and thus illustrates the interactive characteristics that each has with the others (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fundamental Principles in Community-Based Participatory Research With Native American Communities.

Research as Spiritual Covenant

When we began our work with the first community, we knew that spirituality plays a significant role in Native American communities. Although we planned to be respectful of the place that spirituality held, we were unaware of just how pervasive it would become in our project. Slowly we learned that respectful conduct of our research required an ever-present mindfulness of our interactions with the communities. This sort of interaction has incorporated a mutual sharing, with an understanding of how we influence and are influenced by the research project.

For many Native people, “words have been held as sacred things to be used carefully” (Cross, 1995, p. 143). Because of the Native people's respect for words, which represents a sharing from the heart, the turning of sacred words into publishable articles has been approached with sensitivity and respect. Considerable care has been put into expressing our ideas and choosing our words. Maintaining confidentiality of both persons and the communities has been paramount in this process. We also have guarded against stereotypical characteristics. Because there are more than 550 tribes in the United States (Stubben, 2001), each with a unique culture, it is difficult to generalize from one nation to another (Letiecq & Bailey, 2004). Finally, in our writings and presentations, we strive to ensure that we are neither representing nor speaking for the tribes; rather, we are reporting from our perspective of a particular aspect of the project.

When we met with community members as a group, a spiritual leader began and ended the meetings with a prayer; similarly, each day of training for the FCC facilitators began and ended with prayer. Those families, who currently use the FCC intervention, often request a spiritual leader to be in attendance during the meeting. As the relationships among the members of our research team have deepened with trust, we have incorporated a centering invocation to begin our face-to-face research team meetings to provide focus and remind us of the purpose of our work.

Through the process of interviewing, we realized the honor and responsibility of holding sacred people's stories, stories that touched our hearts. Because we had been given much, not only wisdom from the people but their trust as well, our own sense of integrity called for our research to provide something in return to the communities who had graciously opened themselves to us. We were aware that our work evoked in us feelings of fidelity, caring, and gratitude, virtues common to the fields of social work and nursing with their characteristic focus on relationships. These same qualities are described by Wax (1991) as the basis for a covenantal ethic that “acknowledges the indebtedness of one to another” (p. 15). He suggested that a covenantal ethic might be most appropriate for work with Native American communities. Wax (1991) argued Western bioethics are deficient because they don't adequately consider

the goals, values, or interests of those who become involved in research as subjects, nor does it see them as social beings, linked in a network of responsibilities and obligations to others. (p. 2)

With increasing awareness, as our work progressed, it became apparent to us that we were operating within a covenantal ethic.

Reciprocity

Based on factors of interdependence and survival, reciprocity is a ubiquitous norm in Native American communities. Deiter and Otway (2002) related the concept of reciprocity to spirituality in their statement that “if you take something from someone, you have to give something back: this keeps life in balance. In this way, all knowledge is spiritual knowledge” (p. 14). Reciprocity has been a vital part of our research project. Since its inception, the Caring for Native American Elders project has incorporated a service component rather than merely gathering descriptive data. This principle of reciprocity has motivated our work with the community to ensure the project's sustainability.

Harmony

Reciprocity nurtures harmony. The salience of nurturing harmony was apparent at many levels in the Caring for Native American Elders project. At the level of the team, we recognized that each team member brought a different perspective to our work. These differing perspectives represented advantages and challenges.

The primary advantages of working within such a team are the “differences in interpretive frames resulting from different experience histories and the marginal stance created by putting together these different frames” (Bartunek & Louis, 1996, p. 18). This marginal stance represents the “intersection of the contrasting perspectives” (Bartunek & Louis, 1996, p. 18). The marginal stance is the place from which new understanding of the phenomenon under study may emerge (Bartunek & Louis, 1996).

Our differing perspectives necessitated special considerations that had to be addressed for us to work smoothly. Being aware of how cultural differences influenced perceived meanings and consequences of actions, communications, and events was important. Trust, honesty, and respect were forged through the use of multiple teleconference conversations and, most importantly, through face-to-face meetings. We developed the Memorandum of Understanding to establish team norms that would nurture the valuing of differences and the important part these differences played in the research process. We determined that all decisions would be made by consensus, thus ensuring the equal distribution of power among team members. We have remained committed to the reflective process as an integral part of our work to allow discussion of each of our opinions about our parts in the Caring for Native American Elders project.

At the level of community, we continued to reflect on our interactions with each of the communities with whom we are working. We have not competed with the community for funding sources that are available to them. While waiting to hear funding status, we have kept in touch with the members of the communities each time we received word of the proposal's progress. In the first community, following the completion of one portion of the project and before beginning the next phase, we requested direction from an ad hoc advisory board. Harmony has been nurtured by our reliance on the guidance of the cultural insider for respectful entry into the community. The cultural insider also is involved with all data analysis and/or writing and reviewing all reports arising from the project as a safeguard against cultural misinterpretation.

Respect for All

For our team, the principle of respect for all carries more depth than either the standard bioethical or colloquial use of the term. Respect for all is not limited to the Kantian notion of personhood but extends to other living and nonliving things and the environment. Further, our use of the term also assumes an attitude that engenders an ever-present mindfulness in thought and speech and action. In our projects, the principle of respect led us to employ more than the standard institutional review board safeguards of confidentiality and individual risk; we felt compelled to consider the idea of community identifiability and risk. This realization occurred after the initial phases in the first community and after we learned our R21 grant would be funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research. As a result, we requested that the National Institutes of Health modify the grant title and abstract by using a pseudonym for the community and striking other identifying information.

Many Native people gain their identity from their tribes and extended families rather than from personal achievements. Strict attention was paid to the research process being conducted in a manner that would adhere to tribal values and norms. The cultural insider was vigilant of this process for several reasons. By assisting the research team in the “right way” of conducting research, she eased community acceptance of the project and assured respectful interaction between the research team and the community. Correspondingly, if the research were conducted in a disrespectful manner, it would have the potential to reflect poorly not only on the cultural insider as a professional, but personally on her intergenerational family as well.

A component of conducting research in the right way involved modifying our standard communication patterns. This included using indirect rather than direct conversation, mindful silence, softer speech, gentle handshakes, and the importance of sharing food. We learned that salient perspectives and information are often shared through the use of stories and that being teased may indicate acceptance and the connectedness of persons' diverse cultures through mutual interests and concerns such as children and family relations.

Cultural Humility

Cultural humility (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998) is a comprehensive concept. It is linked to the mindfulness inherent in the idea of research as spiritual covenant. Working from a perspective of cultural humility refocuses the researcher toward the need for self-exploration and self-understanding to maintain mindfulness for the investigator part of the community-academic relationship.

In recent years, with an increasingly diverse and multicultural society, there has been growing emphasis on cultural competency in the health and human services sectors. Curricula aimed at teaching cultural competence place the focus of understanding on the population to be served with the intent to ease interactions across cultures (Hunt, 2001). Although knowledge of cultural differences is vital in cross-cultural interactions, the need to guard against stereotyping that may arise from a naïve understanding of differences is equally vital (Tripp-Reimer, 1984; Tripp-Reimer & Fox, 1990). Hunt (2001) argued that cultural competency is a poorly defined concept, with no criteria for measuring achievement. She further argued that knowledge of cultural traits does not translate into cultural competency.

Cultural humility transcends the concept of cultural competency by highlighting the mutuality of the cross-cultural partnership. Cultural humility, as posited by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia (1998), involves a commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, with the goal of dismantling power imbalances and developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic partnerships. A commitment to honest and ongoing self-evaluation will increase awareness of unintentional or intentional prejudices on the part of the researcher (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Throughout our interactions as a team, we have made an effort to be conscious of ways in which prejudices, whether unintentional or intentional, could be harmful to the other. For example, because we have recognized that each research team member has a contribution to make to the project, we do not presuppose the academic team members to be experts in all areas of the research project, particularly those related to cultural sensitivity. From past experiences, the cultural insider was attuned to the possibility of being treated as only token within the research team. Tokenism may occur when an individual from a minority group is invited to participate in an endeavor because of mandated policy or to make a research project attractive to scientific reviewers. Tokenism can be subtle but generally involves giving less weight to the contributions of the minority person than to the contributions of the other participants. This implies a prejudicial assumption of superior expertise by those people who are members of the majority group. The cultural insider was careful to let us know her feelings and to give her perspective when our actions could have been seen as disrespectful, or off putting, to tribal people. The formal reflections that were built into the project provided a place for the team to share and discuss the dynamics of our work.

Project Phase Matrix

The project phase matrix was developed to provide a framework to illustrate the phases of the project (the x-axis) in interaction with participants (the y-axis). We identified four phases. They include (a) project inception, (b) engaging the community, (c) implementing the project, and (d) sustaining the project. We also identified three levels of participation in the project, including (a) individual team members, (b) the team as a whole, and (c) the community. Longitudinally, we are in different phases of the research project with each of the three communities. The concepts identified in the matrix are iterative and cyclical in nature and active, to varying degrees, throughout the project. In the matrix, the salient, phase-specific concepts fill the lower half of Table 1, following a diagonal from the upper-left-hand corner to the bottom right (see Table 1).

Table 1. Project Developmental Phase Matrix.

| Project Inception | Engaging the Community | Implementing the Project | Sustaining the Project | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level |

|

|||

| Team level |

|

|

||

| Community level |

|

|

|

|

Inception of the Project

Inception of the project, individual level

The most salient concepts during the inception phase of the project included (a) affirming team members' diverse backgrounds and (b) attending to credibility stress. The research team is diverse in composition. There is one social worker; three nurses, representing anthropology, sociology, and gerontology; one Native person; and three non-Native people. Each member of the research team came with unique and varied skills, goals, and histories. The cultural insider came to the project with the intention of program development and implementation to meet a need that she recognized in several Native American communities in the Northwest. The cultural insider, drawing on personal and professional experiences, has intimate knowledge of tribal communities, their norms, and the potential influence of tribal politics. The academic members came from a research perspective with the intention of advancing scientific knowledge. Each team member brought vital skills and experience to the team. Two members of the team are established investigators with research expertise arising from many years of scholarly activity. The fourth team member, as a new investigator but resident of a town close to the research sites, provided project coordination and a geographical link between the cultural insider and the experienced investigators.

The team is composed of women in their fifth and sixth decades of life, each with a history of life experiences and knowledge that has led to her maturity and being grounded in herself. Based on our previous life and professional experiences as women, we have grown accustomed to giving high consideration to relational and participatory interactions. In addition, as women, particularly in two helping professions, we know that other realities exist in addition to our own, and therefore we are aware of the need to enter relationships softly (Schaef, 1981). All team members came to the project with a generative desire to do work that has the potential to make a difference in people's lives.

Credibility stress was very prominent on the individual level during the project inception phase. Each of the team members experienced credibility stress as a gatekeeper to the tribal and scientific communities. The cultural insider provided a credibility bridge between the research team and the community. The novice research team member and friend of the cultural outsider provided a credibility bridge between her and the other team members. The senior researchers provided a credibility bridge and expert guidance between the project and the larger scientific community. Credibility stress occurred in the inception phase because the team members had little working experience with each other and there had been insufficient time to develop trust. Each of us was aware that the manner in which this project was conducted would reflect on each of us from a professional and personal perspective, and we were uncertain about how each would be perceived by our respective constituents.

Inception of the project, team level

At the team level, during the inception phase, attention was given to (a) developing trust among the team members and (b) integrating the diversity of the team. Given the context of credibility stress the team was experiencing, establishing trust among the team members was essential at this stage of the project. Our four team members lived in three different cities in two states separated at the most by 1,500 miles. Technology allowed us to function as a team through the use of e-mail and the telephone. Although these modes of communication allowed accessibility for our geographically separated team, two face-to-face encounters were necessary that 1st year to allow sharing at a deeper level.

In addition to our face-to-face meetings, we have focused on our similarities as women with similar family circumstances of aging and frail parents and as helping professionals. We have been supportive of one another as we have progressed through our work and these stages of our lives. Although our lives have intertwined throughout the course of this project, when we first began our work together it was important to delineate the multiple roles we each held to be sensitive to difficulties that might arise from the overlap in roles.

Inception of the project, community level

The concepts most active at the community level during the initial phase of the project included (a) making a quiet entry, (b) making connections, (c) gaining community support, and (d) attending to credibility stress. Sensitivity was required to secure community approval for the project to submit a proposal for funding. The cultural insider handled this first by approaching people in the community with whom she had either a professional or personal connection. Eventually she spoke with each community's tribal president, who is the person elected to serve in a position of leadership as head of the governing Tribal Council. Each president asked us to visit with the directors of the senior citizen's programs. These individuals wrote letters of approval and support for the project. A long waiting period between the submission of the proposal and learning whether it would be approved or rejected then ensued.

Credibility stress continued to be present at the community level. Because of the timing gap of waiting for proposal approval or rejection, the team worried about repeating past outsider injustices by raising hopes of program delivery only to be dashed when nothing was delivered. We were protective of the cultural insider's connection to the bureaucratic, research world because of the potential for her to be seen as co-opting her tribal values. On most reservations, rising above the group is not normative. The cultural insider felt concern with the possibility of disrupting this norm, which could have lessened her credibility and may have reflected negatively on the project. Therefore, we did not conduct a highly visible public campaign to present the possibility of the project to the community. The delicate nature of the subject matter (elder abuse) also precluded using a public campaign until the program had been introduced to the appropriate stakeholders in the community, after funding was available for our work to begin.

Engaging the Community

Engaging the community, team level

At the team level, in the engagement phase of the project, the most prominent concepts included (a) making respectful preparations, (b) balancing academic formality with Native American formality, and (c) maintaining a low profile. The cultural insider provided guidance from her perspective regarding the best way to begin working with the people living on the first reservation. In our first attempt to design a brochure describing the Caring for Native American Elders project, we used a war bonnet as a graphic. We later replaced this graphic with a photo of a distant mountain in the western landscape. The war bonnet had the potential of being interpreted by the Native community as pretentious behavior on the part of the cultural outsiders.

We refrained from including degrees and credentials of the team members in formal, written correspondence because that would have highlighted the cultural insider's association with the academic culture over her community ties. Although degrees and credentials are valued by the Native community, personal integrity and relationships provide more credibility. The formality that often is linked with titles and degrees has historically been associated with the oppression of Native American people. At this stage of the project development, we did not use formal letterhead for similar reasons.

The cultural insider helped us understand the type of formality that may be considered respectful by Native American people. Gracious hospitality required that in those instances when it was possible, we shared a meal with the interview or FCC participants. Following each formal encounter, we sent a thank you note expressing our gratitude for the thoughts and wisdom the participants had shared with us. We included sweet grass, a plant that is used in some tribes for purposes of cleansing and sending out prayers, with an honorarium for spiritual leaders.

The design of our project has employed traditional ethnographic data collection methods. Initially, we considered including a period of orientation for the non-Native researchers that would have been expected in a more traditional ethnographic approach. Tension, however, surfaced around this prospect. The sources of tension came from three different understandings of what the initial stage would be and how it would be structured. The nurse anthropologist, who had conducted numerous field studies in which gathering contextual community data was the first step in initiating a project and who was mentoring the novice research team member, believed the novice researcher needed orientation to the community prior to conducting interviews. The novice researcher believed the orientation was unnecessary and even superfluous because of her close connection with the Native research team member, who knew the community intimately. The Native research team member had the understanding that she and the novice research team member would be conducting the interviews together, so she, also, did not understand the need for the novice research team member to orient to the community. The Native research team member also had concerns based on a prior experience of having scientists draw inappropriate depictions of the community. After discussing these varying perspectives, we decided to break with the customary ethnographic approach. We did not include an orientation period for the novice research team member. The novice researcher and the Native research team member became the primary field workers. Together they conducted the interview phase of the initial portion of the project.

Engaging the community, community level

At the community level in this phase of the project development, four concepts were active: (a) addressing historic distrust of research, (b) receiving direction from the community, (c) understanding indirect communication styles, and (d) making connections. The CBPR approach helps to mitigate the potential for conflicting outsider intentions because it begins with the development of a community-academic relationship. During the engagement phase of project development, we were aware of continued credibility stress as it was juxtaposed against people's distrust of research. We were cognizant of this dynamic in all phases of the project. We kept the communities apprised of the progress of the proposal through the lengthy scientific review process. Once the project was funded, we consulted with elders and those tribal representatives involved with elders for direction and insight into the feasibility of bringing the FCC intervention to the community. The Memorandum of Understanding also helped guard against pathologizing tribal life through the active participation of the cultural insider in all reports emanating from the project results. At later stages in the project, we were vigilant about placing identified problems into their historical context and balancing problems with the many strengths found in the community. Finally, we reported our findings back to the community to receive comments and suggestions for future directions for the project.

As we began making more contacts within the first community, we experienced communication styles that, without the cultural insider's interpretation, could have left us a little bewildered. During a focus group where we hoped to elicit direction related to community education regarding elder mistreatment, we noticed an indirect means of providing opinions. Each member of the focus group spoke primarily from the perspective of personal stories but with an indication of need for information regarding elder mistreatment. We, however, were not given overt suggestions as to how to go about providing the education. With a certain amount of reflection, we realized that we had received direction in an indirect rather than a direct, linear manner. We changed our initial plans to have a community-wide educational workshop on elder mistreatment. Instead, we made several small presentations at regularly scheduled events held in the community.

During the engagement phase with the other communities, a circular means of making connections also was employed. On the second reservation, initial contact was made through the Social Services Department because it was a logical place to start and because the cultural insider knew the people in this department from both personal and professional experiences. From this initial contact, the connecting effort began to branch. One of the social services people contacted a person in the judicial system. Because the cultural insider was aware of the heavy workload of the reservation Social Services Department, the cultural insider also contacted a prominent tribal elder, who, in turn, contacted the Tribal Council and the Tribal Health Department. On advice from the tribal elder, the cultural insider contacted the director of the Senior Citizen's Program and the director of the Tribal Health Department. At that point we received a letter from the president of the Tribal Council asking that the Senior Citizen's Program director coordinate tribal activities related to the project, but not before we spoke with the tribal elders. On the third reservation, connections for entry into the community followed a similar pathway.

Implementing the Project

At the community level in the implementation phase, four concepts were salient: (a) being flexible, (b) focusing on community strengths, (c) understanding the project's influence on the community, and (d) noticing increasing trust on the part of the community. Flexibility was vital to several aspects of our work. Comfort with flexibility was needed in terms of changing times and dates of scheduled research events. From a tribal point of view, the collective participation at spontaneous events or circumstances (e.g., a death in the community, ceremonies, a veteran's return home, school athletic events) is an expectation; thus, sometimes we needed to postpone research-related meetings that had been planned previously and to join in the tribal event if invited. In small communities, people have many roles with concomitant expectations of presence and time that may interfere with arranging research-related meetings. Outsiders might inappropriately interpret this as disinterest.

We were flexible when interviewing. When we arrived for the first interview, instead of speaking with only one individual as planned, the person with whom the cultural insider had arranged the interview had invited other members of the agency to participate in the interview as well. This also happened with other interviews. We realized that this custom increased the richness and depth of information presented to us. It also highlighted the need for flexibility in our approach to data collection and made the discrimination between individual interviews and focus groups rather artificial.

During all phases of the project, but particularly important during this phase, we focused on community strengths. In reports, we paid attention to maintaining the integrity of the community as whole and not separate from the research project. Highlighting only community difficulties is not foundational for action; ignoring community strengths may further traumatize individuals or the collective community (Manson et al., 2004). Strengths have been apparent throughout the project in each community, for example, the importance of elders and family, the value of interdependence, the presence of spirituality, the use of humor, the pride in tribal traditions, the loyalty to homeland, and the generous sharing. These strengths have sustained the people in the communities in which we worked, and they provide a foundation in which to embed the service component of the project.

We maintained an awareness of the ways in which the research project influenced the communities. We were aware of the possible imposition on time. As would be expected, we usually met with people for interviews when and where it was convenient for them. In some situations, however, such as attendance at the FCC, we were aware that participation could have imposed a financial burden on some family members, such as transportation to a meeting and securing child care. In these situations, we provided an honorarium to help defray these expenses.

When the project expanded, another influence on the community was our ability to employ three tribal members. These positions were advertised in the weekly newspaper, and employment opportunity fliers were posted in prominent places, such as the tribal offices, post offices, a grocery store, and the tribal community college. Once the FCC facilitators were hired, we informed the community that the implementation phase of the project had begun. This was accomplished by having two articles published in the local newspaper approximately 4 months apart. New fliers that included a description of the FCC and contact numbers for referrals were posted in private and public agencies throughout the reservation. The cultural insider visited with representatives from each agency that had relevance to senior citizens and their families. She discussed the project and left brochures that described the FCC intervention and that provided contact information. A multiagency luncheon was held, but because of frigid weather (−32° F), few people were able to attend. The cultural insider has continued to contact the agencies on a regular basis to maintain program visibility.

An unexpected outcome of this project has been an apparent growth, on the part of community members, of increasing trust in the academic-community partnership. As the FCCs have progressed, needs of the families, tangentially related to elder mistreatment, have emerged. The need for Alzheimer's disease education and caregiver support has become apparent. Similarly, people have spoken about the need for a diabetes support group. Representatives from the local community college have asked the cultural insider to assist in the development of a gerontological course that is anchored in their culture. There also is talk about developing a certification program in gerontology at the tribal college in one of the communities.

Sustaining the Project and Thoughts for the Future

The salient concepts in this phase of the project development are (a) planning for sustainability and (b) developing potential sustainability partnerships. One of the evaluation criteria for CBPR projects is developing and implementing a plan for the project's sustainability (Holkup et al., 2004). Although the project has not fully reached this phase, thoughts about its sustainability have been with us from the beginning. For example, when exploring early potential funding sources for this project, we did not apply for monies that were specifically directed toward tribal projects, so as not to be in competition with them for potential future applications. Renewable sources of funding, such as programs supported by the Older American's Act, could prove instrumental in the sustainability of this intervention. If it can be shown that the FCC intervention is an effective and established means of addressing elder mistreatment for Native American families, prospects of securing local, state, and/or national funds to maintain the intervention should increase.

Continued contact with elder-focused agencies in the first community has kept service providers appraised of the project's progress and perceived efficacy. Now that some trust has developed in the FCC intervention, we are in the process of inviting representatives from these service-providing agencies to form a project advisory committee. Working with this committee will help us tailor the FCC intervention more closely to community needs. Within this committee, we can begin to discuss various possibilities for the project's sustainability.

Conclusion

Carson and Hand (1999) claim that “Native Americans have been studied more than any other group … yet they remain among the most disadvantaged groups within the United States” (p. 161). This statement begs the question: Why hasn't research made a difference for Native American people? Challenges to conducting research with Native American communities include a long-standing, well-founded distrust of research that, at times, has represented yet another means of oppression by the predominant culture. Even the best intentions of scientists may go awry in the interface between the sometimes immensely diverse worldviews of the scientific and the Native American communities. Using a CBPR approach to form academic-community partnerships with Native American people may provide a means to rebuild trust in the research process. Based on our work with three tribal communities in the Northwest, we identified five foundational principles that have guided our research. Adhering to these principles has helped us to maintain mindfulness of thought and behavior in our relationships with the three communities. The use of the CBPR approach has contributed to deepening our understanding of conducting cross-cultural research from a covenantal perspective.

Acknowledgments

Authors' Note: We would like to acknowledge the following funding sources that supported our research: Grant NINR P30 NR003979 from the Gerontological Nursing Intervention Research Center at the University of Iowa College of Nursing; Grant NINR P20 NR07790 from the Center for Research on Chronic Health Conditions in Rural Dwellers at Montana State University; Grant NINR R21 NR008528 from Caring for Native American Elders: Phase III; and a grant from John A. Hartford Foundation's Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholarship Program.

Footnotes

For a comprehensive review of the history of the relationship between Native Americans or Alaska Natives and the United States, please see Hendrix and Winters (2001).

Contributor Information

Emily Matt Salois, University of Iowa College of Nursing.

Patricia A. Holkup, Montana State University.

Toni Tripp-Reimer, University of Iowa College of Nursing.

Clarann Weinert, Montana State University.

References

- American Indian Law Center. Model tribal research code. 3rd. Albuquerque, NM: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek JM, Louis MR. Insider/outsider team research. Vol. 40. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carson DK, Hand C. Dilemmas surrounding elder abuse and neglect in Native American communities. In: Tatara T, editor. Understanding elder abuse in minority populations. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL. Understanding family resiliency from a relational world view. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, Fromer JE, editors. Resiliency in Native American and immigrant families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Deiter C, Otway L. Research as a spiritual contract: An aboriginal women's health project. Centres of Excellence for Women's Health Research Bulletin. 2002;2(3):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B. Native American postcolonial psychology. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. The Indian family wellness project: An application of the tribal participatory research model. Prevention Science. 2002;3:235–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1019950818048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix L, Winters C. Academic education. Evaluating healthcare information on the Internet: Guidelines for nurses. Critical Care Nurse. 2001;21(2):62, 64–65, 67–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with a Native American community. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(3):162–175. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM. Beyond cultural competence: Applying humility to clinical settings. The Park Ridge Center Bulletin. 2001;24:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq BL, Bailey SJ. Evaluating from the outside: Conducting cross-cultural evaluation research on an American Indian reservation. Evaluation Review. 2004;28:342–357. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04265185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay AC, Delormier T, McComber AM, Cross EJ, Potvin L, Paradis G, et al. Participatory research with native community of Kahnawake creates innovative code of research ethics. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1998;89(2):105–108. doi: 10.1007/BF03404399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Garroutte E, Goins RT, Henderson PN. Access, relevance, and control in the research process. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16(5):58S–77S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304268149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard E. The growing negative image of the anthropologist among American Indians. Human Organization. 1974;33:402–403. [Google Scholar]

- Mihesuah DV. Natives and academics: Researching and writing about American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Power, trust, and dialogue: Working with communities on multiple levels in community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossy-Bass; 2003. pp. 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:856–860. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, McDonald J, Bell RA, Arcury TA. Aging research in multi-ethnic rural communities: Gaining entree through community involvement. Journal of Cross-cultural Gerontology. 1999;14:113–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1006625029655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse J, Johnson T, Weiner D. Commentary: Cultural perspectives on research among American Indians. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 1989;13:267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Schaef AW. Women's reality: An emerging female system in the White male society. Minneapolis, MN: Winston; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Christopher S, McCormick AKHG. Development and implementation of a culturally sensitive cervical health survey: A community-based participatory approach. Women and Health. 2004;40(2):67–86. doi: 10.1300/J013v40n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker R. Are academics irrelevant: Approaches and roles for scholars in community based participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossy-Bass; 2003. pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Stubben JD. Working with and conducting research among American Indian families. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;44:1466–1481. [Google Scholar]

- Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project. A gathering of wisdoms: Tribal mental health: A cultural perspective. 2nd. LaConner, WA: Swinomish Tribal Community; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble JE. The sojourner in the American Indian community: Methodological issues and concerns. Journal of Social Issues. 1977;33(4):159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp-Reimer T. Research in cultural diversity. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1984;6:353–355. doi: 10.1177/019394598400600333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp-Reimer T. Cultural interventions for ethnic groups of color. In: Hinshaw AS, Shaver O, Feetham S, editors. Handbook of clinical nursing research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp-Reimer T, Fox S. Beyond the concept of culture, or how knowing the cultural formula does not predict clinical success. In: McCloskey JC, Grace HK, editors. Current issues in nursing. 3rd. St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby; 1990. pp. 542–546. [Google Scholar]

- Wax ML. The ethics of research in American Indian communities. American Indian Quarterly. 1991;15(4):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]